Summary

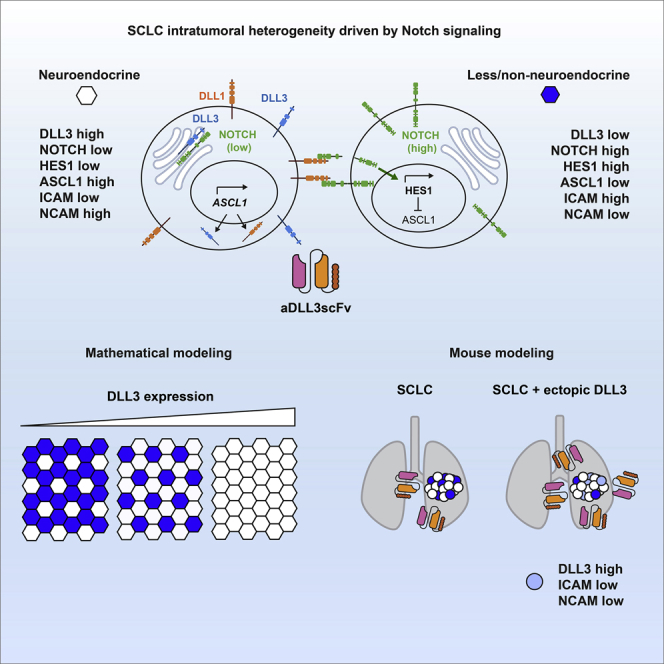

Tumor heterogeneity plays a critical role in tumor development and response to treatment. In small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), intratumoral heterogeneity is driven in part by the Notch signaling pathway, which reprograms neuroendocrine cancer cells to a less/non-neuroendocrine state. Here we investigated the atypical Notch ligand DLL3 as a biomarker of the neuroendocrine state and a regulator of cell-cell interactions in SCLC. We first built a mathematical model to predict the impact of DLL3 expression on SCLC cell populations. We next tested this model using a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) to track DLL3 expression in vivo and a new mouse model of SCLC with inducible expression of DLL3 in SCLC tumors. We found that high levels of DLL3 promote the expansion of a SCLC cell population with lower expression levels of both neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine markers. This work may influence how DLL3-targeting therapies are used in SCLC patients.

Subject areas: Molecular biology, Cancer, In silico biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ectopic expression of DLL3 suppresses Notch signaling in SCLC cells

-

•

Lateral inhibition model predicts expression level-dependent effects of DLL3

-

•

Anti-DLL3 scFv labels SCLC cells in vitro and in vivo

-

•

DLL3 expression prevents cell-fate bifurcation in mouse model of SCLC

Molecular biology; Cancer; In silico biology

Introduction

Tumors consist of a variety of cancer and non-cancer cells. Both cancer cells and non-cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment display various levels of heterogeneity. This heterogeneity may vary over time and environmental conditions, and it plays an important role in tumor development, including shaping the natural response of tumors to the immune system or treatment in the clinic (reviewed in1,2,3,4).

SCLC is an aggressive subtype of lung cancer with fast growth rates and a striking metastatic ability. The median overall survival of SCLC patients has remained close to 8–10 months in the past 3 decades, with a 5-year survival at ∼6% and over 200,000 estimated deaths worldwide every year. Most tumors respond well initially to standard-of-care chemoradiation treatment, but resistance emerges rapidly in nearly all cases (reviewed in5). The recent approval of T cell immune checkpoint inhibitors has been beneficial to only a small fraction of SCLC patients (reviewed in6). There is a critical need to develop biomarkers for SCLC development and more efficient therapeutic strategies.

SCLC tumors harbor few non-cancer cells7 but inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity is still a prominent feature of these tumors. At the epigenetic/transcriptional level, SCLC tumors have been classified into different subtypes based on transcriptional programs driven by specific transcription factors in cancer cell populations, with the SCLC-A (expressing the ASCL1 transcription factor) and SCLC-N (expressing the NEUROD1 transcription factor) neuroendocrine subtypes being the most frequent in patients.8,9,10 Importantly, mounting evidence indicates that individual SCLC tumors are comprising heterogeneous populations of cancer cells with different levels of neuroendocrine gene programs.11,12,13 As an example of this intratumoral heterogeneity, in SCLC-A tumors, activation of Notch signaling can reprogram neuroendocrine (NE) cancer cells toward less/non-neuroendocrine (non-NE) phenotypes.12 The non-NE cells are less tumorigenic and genetic and pharmacologic approaches to promote NE to non-NE differentiation have been shown to decrease SCLC tumor growth.14 But non-NE can support the survival of the NE cells, including when tumors are treated with chemotherapy.12,15 In this context, the mechanisms activating Notch signaling are not completely understood, but may depend on the YAP transcriptional regulator.16 As another example, in SCLC-N tumors, expression of c-MYC can activate Notch signaling, which also promotes the transition of these tumors to a less neuroendocrine phenotype.17 These data and data from human tumors indicate that both inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity are likely key contributors of the ability of SCLC tumors to become resistant to therapies.8,18,19

DLL3 (Delta-like ligand 3) is an atypical ligand for NOTCH receptors initially studied for its role in early pattern formation in mouse embryos.20,21,22 Early work showed that DLL3 does not activate Notch signaling but rather functions as an inhibitor of Notch signaling in a cell autonomous manner,23 possibly in a cis-inhibition mechanism in the Golgi.24,25 However, genetic studies of DLL3 O-fucosylation indicate that interactions with NOTCH may not fully account for the physiological function of DLL3, suggesting possible Notch-independent roles for DLL3 in vivo.26 The mouse Dll3 gene is a direct target of ASCL127 and DLL3 is expressed in a significant number of human SCLC tumors. Importantly, Saunders and colleagues showed that DLL3 is present at the surface of SCLC cells and that targeting DLL3-expressing SCLC cells using an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) can eradicate SCLC in pre-clinical models.28 Clinical trials using Rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T), an ADC targeting DLL3, have been unsuccessful largely because of toxic side effects of this molecule (e.g.,29,30,31). However, other strategies are being developed to target DLL3 expressing cells, (e.g.,32,33,34,35) and DLL3 remains a target of interest for detection and treatment of SCLC.

Here we developed tools and models to further investigate the role of DLL3 as a biomarker of SCLC and as a regulator of Notch signaling in SCLC. We used mathematical modeling based on published data to predict the potential role that DLL3 expression may have on tumor heterogeneity. We further developed a new single-chain fragment variable (scFv) that can bind DLL3 on cells in culture and in vivo. Finally, we used this scFv to test our mathematical models in a new genetically engineered mouse model of SCLC with inducible expression of DLL3. Our data show variable levels of DLL3 expression in SCLC and indicate that DLL3 expression contributes to intratumoral heterogeneity.

Results

Modeling the role of DLL3 in Notch-driven intratumoral heterogeneity in SCLC

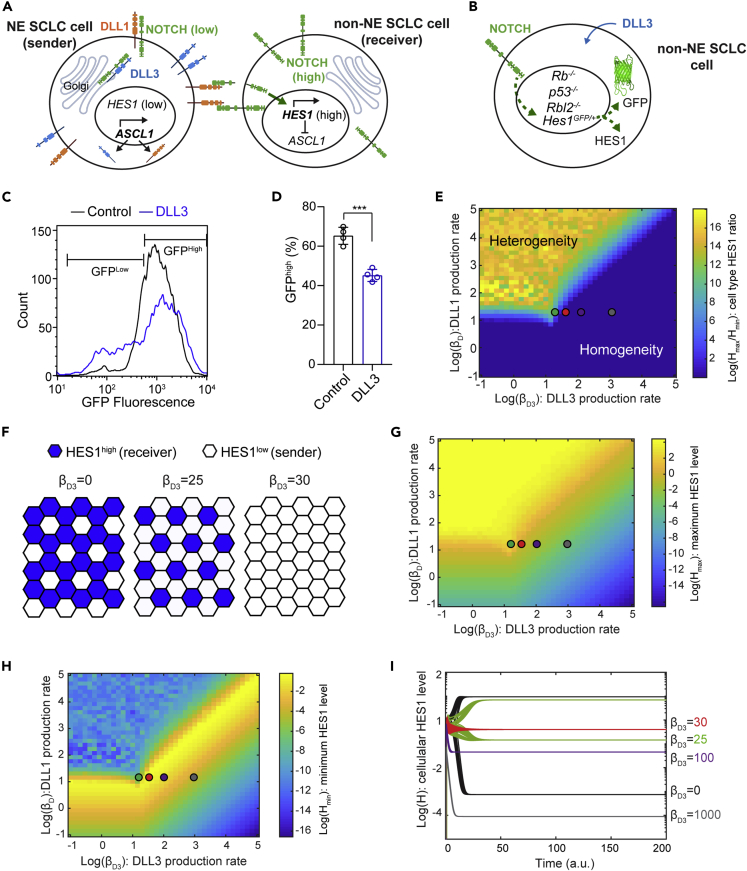

DLL3 is often viewed as a cis-inhibitor of Notch signaling during development because of its role in localizing NOTCH receptors in the Golgi (Figure 1A). To determine if DLL3 could suppress Notch activity in SCLC cells, we used cells derived from tumors in the Rbfl/fl;p53fl/fl;Rbl2fl/fl;Hes1GFP/+ mouse model of SCLC (RPR2;Hes1GFP model, also known as TKO;Hes1GFP, for triple knockout).12,16 In this model, SCLC cells express GFP when the Hes1 promoter is active. Because Hes1 is a target of Notch signaling, GFP expression can serve as a reporter of Notch activity, and HES1GFP-positive (HES1pos) cells are less/non-neuroendocrine.12,16 We isolated HES1pos cells from RPR2;Hes1GFPmutant tumors, and ectopic expression of FLAG-tagged DLL3 in these HES1pos cells led to fewer GFP-positive cells, providing further evidence that DLL3 can suppress Notch signaling in cis in this SCLC context (Figures 1B–1D and S1A).

Figure 1.

Mathematical model of mutual inactivation shows production rate-dependent role of DLL3

(A) Schematic of Notch, DLL1, and DLL3 interactions in lateral inhibition with mutual inactivation (LIMI).

(B) Schematic of HES1GFP-positive cells from an RPR2;Hes1GFP tumor serving as a reporter cell line, with GFP expression from the Hes1 locus to monitor the effect of ectopic DLL3 expression in regulating Notch activity.

(C) Flow cytometry of HES1GFP-positive cells with (blue) and without (black) ectopic expression of DLL3 (representative of n = 4 biological replicates).

(D) Percentage of GFPhigh HES1GFP-positive cells with and without ectopic expression of DLL3. Unpaired t-test, data represented as mean ± s.d. ∗∗∗p<0.001.

(E) Log(Hmax/Hmin) at steady state were calculated as a function of βD3 and βD. Regions with values greater than 0 (light blue to yellow regions) support patterning, whereas those with 0 (dark blue) do not.

(F) Hexagonal cell lattice with LIMI showing that DLL3 expression can lead to sparser patterns of HES1high cells (blue) or no pattern (homogeneous color).

(G) Hmax as a function of βD3 and βD.

(H) Hmin as a function of βD3 and βD.

(I) Simulations with the indicated parameters for βD3 showing H levels in cells with high and low final H levels.

Green, red, purple, and gray dots in (E), (G), and (H) correspond to the parameters used in (I). See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

In the Notch signaling pathway, activation of NOTCH receptors by their ligands, including Delta-like proteins (DLLs), leads to NOTCH cleavage, releasing the NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD). NICD induces transcription of the gene coding for HES1, which is an inhibitor of ASCL1, which is itself an activator of the expression of NOTCH ligands (DLLs, representing DLL1/3/4 and Jagged1/2 here).27,36 This negative feedback leads to lateral inhibition and distinct cell fates among neighboring cells: low NOTCH/high DLL (‘sender’) cells and high Notch/low DLL (‘receiver’) cells (Figure 1A).37 To gain a better understanding of the consequences of DLL3 expression on Notch signaling and intratumoral heterogeneity in SCLC, we built a simple mathematical model by incorporating DLL3 in the canonical mutual inhibition model of lateral inhibition38 using the following reactions: (1) NOTCH receptors, denoted N, bind to DLL1 (as a representative of all NOTCH ligands, denoted D) in trans, which leads to cleavage of NOTCH and release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), denoted S; (2) NICD increases expression of HES1, denoted H39; (3) HES1 inhibits expression of DLL127,36; (4) NOTCH receptors bind to DLL1 and DLL3, denoted D3, in cis, which inhibits NOTCH cleavage.23,25,40 As expected, setting the production rate of D3 at 0 replicated the results from previous studies on mutual inactivation38,41supporting patterning even without cooperative regulatory feedback in the lateral inhibition model (Figures S1B–S1G). We simulated this model using 1600 parameter sets across a two-dimensional parameter space spanning a wide range of production rates of D (βD) and D3 (βD3) (Figure 1E and Equations (1), (2), (3), (4) in STAR methods section, and Table S1 for parameter values). To represent multicellular interactions, a two-dimensional hexagonal cell lattice was used for each parameter set. We plotted log(Hmax/Hmin), where Hmax and Hmin are the maximal and minimal HES1 levels in the hexagonal lattice at the steady state, respectively, as a function of βD and βD3 to observe parameters leading to lateral inhibition, or heterogeneity in HES1 level.42

The cis-inhibition model shows that when βD3> βD, HES1 heterogeneity mostly does not occur, indicating effective inhibition of cell-type bifurcation (Figure 1E). Within the parameter regime leading to heterogeneity, βD3 also regulates the ratio of receiver (HES1high) cells and sender (HES1low) cells, with higher number of sender cells as βD3 increases (Figure 1F). We next examined Hmax and Hmin separately. Hmax consistently decreases as βD3 increases (Figure 1G). Of interest, a large region of parameter space shows higher Hmin with increasing DLL3 (Figures 1H and 1I). Hmin increases throughout the parameter regime that leads to heterogeneity, peaking near βD3 = βD, and gradually decreases as βD3further increases (Figure 1H).

In this system, our mathematical modeling suggests that the influence of DLL3 on the heterogeneity of HES1 level depends on the level of DLL3 expression. At high levels (βD3>> βD), DLL3 inhibits both heterogeneity and Notch activation. At lower levels, however, DLL3 allows trans-interaction between NOTCH and other DLLs while preventing lateral inhibition, which leads to homogeneous intermediate NOTCH activation throughout the cell population. In the parameter space leading to heterogeneity, DLL3 expression also affects sparsity of the receiver cells.

Generation and validation of a single-chain fragment variable (scFv) binding DLL3

Given that differences in DLL3 expression level may contribute to intratumoral heterogeneity via NOTCH-driven patterning, we sought to examine whether DLL3 levels in tumors were related to the amount of NOTCH signaling or intratumoral heterogeneity present in vivo. To do this, we first developed a new tool to detect DLL3 in tumors in vivo.

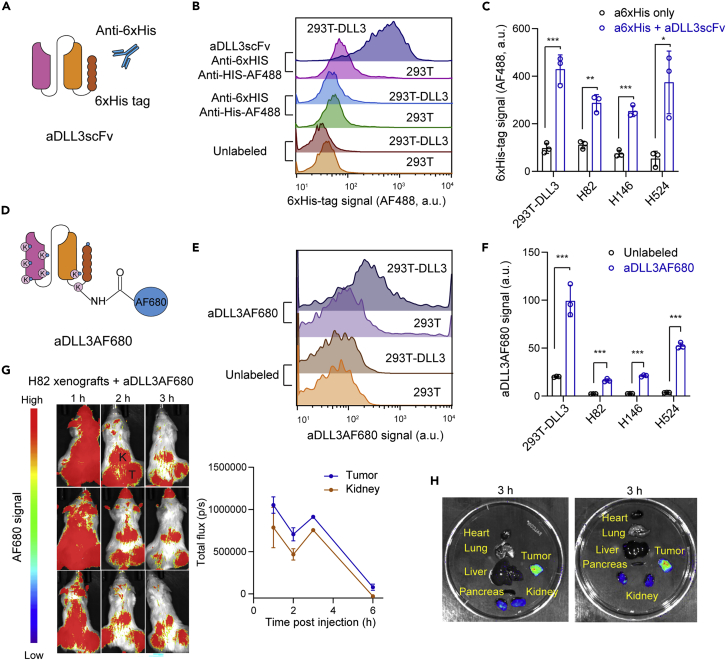

Single-chain fragment variables (scFvs) have several advantages over antibodies, including their small size and their ease of production in bacteria.43,44 We generated a His-tagged scFv based on the sequence of an antibody targeting DLL3 (Methods) (Figures 2A and S2A). We first tested the binding of this scFv targeting DLL3 in 293T cells expressing exogenous DLL3 compared to controls. Flow cytometry analysis using an anti-His antibody showed increased binding in cells expressing mouse DLL3 (Figures 2B and 2C). Using the same approach, we were also able to detect endogenous DLL3 expression in human SCLC cell lines (Figures 2C and S2B). Thus, this scFv targeting DLL3 is capable of binding to DLL3 expressed on the surface of SCLC cells in culture.

Figure 2.

Detection of DLL3 expression at the surface of cells using an anti-DLL3 scFv

(A) Schematic representation of the His-tagged scFv targeting DLL3 (aDLL3scFv) and the detection of cells expressing DLL3 using this molecule.

(B) Representative flow cytometry analysis of DLL3 expression in 293T cells expressing exogenous mouse DLL3 using aDLL3scFv (from n = 3 biological replicates).

(C) Quantification of DLL3 detection in 293T-DLL3 cells from (B) and human SCLC cell lines.

(D) Schematic representation of AF680-labeled aDLL3scFv (aDLL3AF680).

(E) Representative flow cytometry showing binding activity of aDLL3AF680 (from n = 3 biological replicates).

(F) Quantification of (E) in human SCLC cell lines.

(G) Whole body fluorescent images of H82 tumor xenografts with 2 nmol of AF680-labeled scFv injected via the tail vein (left). Tumors (T) and kidneys (K) are indicated. Quantification of imaging signals (right), reported as the total flux (p/s) (n = 3).

(H) Representative ex vivo imaging of two H82-bearing mice in (G).

Unpaired t-test, data represented as mean ± s.d. ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01, ∗∗∗p<0.001. See also Figure S2.

To determine if this scFv molecule (aDLL3scFv) could be useful to detect SCLC tumors in vivo, we directly labeled the amino groups of lysine residues and the N-terminal group of the aDLL3scFv with Alexa Fluor 680 (AF680), a near-infrared fluorophore with strong tissue penetration that is suitable for in vivo imaging (Figure 2D). We first verified that the AF680-labeled aDLL3scFv (aDLL3AF680) still detected DLL3 on the surface of 293T cells expressing exogenous DLL3 as well as SCLC cells in culture (Figures 2E, 2F, and S2C). Noninvasive optical imaging was performed over a 6-h time period following tail-vein injections with 2 nmol of aDLL3AF680 in NSG mice bearing subcutaneous xenografts (H82 model). Whole-body fluorescent imaging showed prominent signal in the tumor area, as well as in the kidney (where the scFv molecules are excreted) 2–3 h post injection (Figures 2G and 2H). Maximum tumor-to-normal tissue contrast was observed 2 h post injection (Figure S2D). Signal from the fluorescent scFv was strong after 1 h and started to decrease after 3–4 h, as expected for a small molecule with a short half-life (Figure 2G).

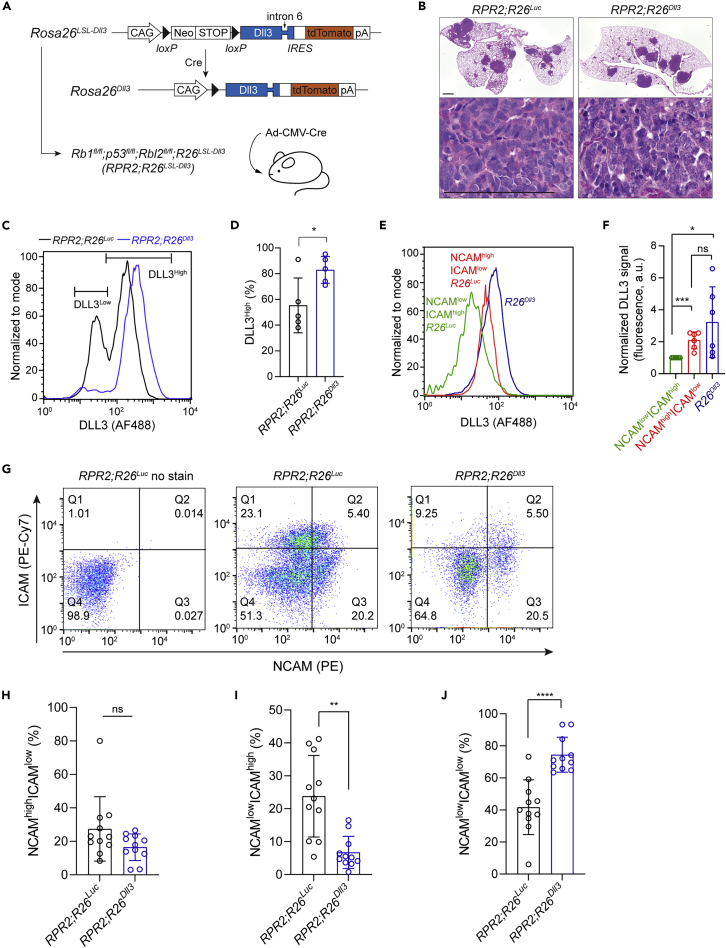

Exogenous expression of DLL3 in mouse SCLC tumors

Notch signaling is a driver of non-neuroendocrine cell fates and intratumoral heterogeneity in SCLC,12,17 and our mathematical modeling predicts that DLL3 may contribute to Notch signaling activity and may modulate heterogeneity. We next sought to test this idea experimentally in the RPR2 mouse model of SCLC where this heterogeneity has been described.12,16 In this model, intra-tracheal instillation of an adenoviral vector expressing the Cre recombinase initiates tumors modeling the SCLC-A subtype of human SCLC. SCLC cells in these tumors express DLL3 at their surface (Figure S3A).

To manipulate DLL3 levels in this model, we generated a new allele to conditionally induce DLL3 expression upon Cre-mediated recombination (Rosa26LSL-Dll3 allele) (Figure 3A). We crossed this allele to the RPR2 model (RPR2;Rosa26LSL-Dll3 mice) and initiated tumors by Ad-CMV-Cre instillation. As controls, we used RPR2;Rosa26LSL-Luc mice.45 Tumors developed in RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 mice, and their histology was indistinguishable from that of RPR2;Rosa26Luc mice; whereas we did not generate enough mice to rigorously quantify tumor number and tumor burden, we did not observe any striking difference in tumor development between the two models (Figure 3B). A cell line derived from a RPR2;Rosa26Dll3mutant lung tumor grew as spherical clusters in suspension typical of neuroendocrine SCLC cell lines12 and showed weak but detectable expression of the tdTomato reporter linked to DLL3 expression, as well as the expected recombination of the Lox-STOP-Lox cassette, validating the new allele (Figures 3A, S3B, and S3C).

Figure 3.

DLL3 expression perturbs the balance between neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine cells in a mouse model of SCLC

(A) Schematic representation of the Cre-inducible Dll3 allele and the genetically engineered mouse model of SCLC.

(B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of sections from RPR2;R26Luc and RPR2;R26Dll3mutant lungs (top, scale bar 1 mm) and lung tumors (bottom, scale bar 100 μm) 6 months after tumor initiation (n ≥ 6 mice).

(C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of DLL3 cell surface expression in SCLC cells from RPR2;R26Luc and RPR2;R26Dll3mutant mice 5.5 months after tumor initiation.

(D) Quantification of (C) (n = 5 independent experiments).

(E) As in (C) with RPR2;R26Luc SCLC cells differentiated by NCAM and ICAM expression.

(F) Quantification of (E) (n = 6 independent experiments).

(G) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of control cancer cells from RPR2;R26Luc tumors with no stain, stained cells from RPR2;R26Luc tumors, and stained cells from RPR2;R26Dll3 tumors (from left to right).

(H–J) Quantification of NCAMhigh ICAMlow, NCAMlow ICAMhigh, and NCAMlow ICAMlow populations in (G).

Unpaired t-test, data represented as mean ± s.d. ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01, ∗∗∗p<0.001. See also Figure S3.

We analyzed tumors from RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 and RPR2;Rosa26Lucmutant mice ∼5–6 months after tumor initiation for DLL3 expression using aDLL3scFv. In control RPR2;Rosa26Luc tumors, we observed two populations of cancer cells, as would be expected for tumors with neuroendocrine (high DLL3) and less/non-neuroendocrine (low DLL3) cells (Figures 3C and 3D). We validated this using NCAM and ICAM staining, with NCAMhigh ICAMlow cells representing neuroendocrine cells and NCAMlow ICAMhigh cells representing less/non-neuroendocrine, as validated previously by RNA-sequencing of these two populations from RPR2 tumors16 (Figures 3E and 3F). In RPR2;Rosa26Dll3mutant tumors, we observed fewer cells with low levels of DLL3 and a more homogeneous population of cells expressing intermediate/high levels of DLL3 (Figures 3C and 3D), indicating that the Rosa26Dll3 allele can elevate DLL3 expression on the surface of DLL3low cells but does not result in further overexpression on the surface of DLL3high cells (Figures 3C and 3D). Similarly, although NCAMhigh ICAMlow cells express higher level of DLL3 compared to NCAMlow ICAMhigh, no significant difference was detected between those of NCAMhigh ICAMlow cells and cells from RPR2;Rosa26Dll3mutant tumors (Figures 3E and3F).

We next quantified HES1 expression as a marker of intratumoral heterogeneity in RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 and RPR2;Rosa26Lucmutant tumors, with HES1high cells being Notch-active and less/non-neuroendocrine. As expected, we found regions with variable numbers of HES1-positive cells12,16 (Figure S3D). However, we did not detect any significant change in heterogeneity based on this marker between the two groups (Figure S3E). Although these experiments indicate that higher levels of DLL3 in tumors do not block the ability of SCLC cells to undergo a transition to a NOTCH-driven HES1-positive state, we reasoned that immunostaining may not be quantitative enough to identify more subtle changes.

We used flow cytometry to compare the expression of NCAM and ICAM in primary lung tumors from RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 and RPR2;Rosa26Luc mice (Figure 3G). Compared to RPR2;Rosa26Luc tumors, we found that RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 tumors exhibited a significant decrease in the NCAMlow ICAMhigh non-neuroendocrine population with no significant change in the NCAMhigh ICAMlow neuroendocrine population (Figures 3G–3I). The change in the NCAMlow ICAMhigh population was reflected by an increase in NCAMlow ICAMlow cells in RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 tumors (Figures 3G and 3J).

The relatively homogeneous population in RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 tumors suggests that higher expression of DLL3 in SCLC cells can inhibit the cell-fate bifurcation process mediated by the Notch signaling pathway. These observations support a model in which DLL3 contributes to Notch signaling activity in SCLC in vivo.

Discussion

Here we investigated the role of the atypical NOTCH ligand DLL3 in a mouse model of SCLC. In our three-pronged approach, we combined mathematical modeling, a new scFv molecule that binds DLL3, and a new allele to induce DLL3 expression in mouse cells. We found that DLL3 expression contributes to the generation of specific subpopulations of SCLC cells, supporting a role for DLL3 in Notch signaling and in the control of intratumoral heterogeneity in SCLC.

The Notch pathway is a highly conserved signaling mechanism implicated in both normal development and the progression of various cancer types. In different tissues, Notch signaling provides a binary fate switch through a biochemical feedback mechanism known as lateral inhibition, which regulates differentiation into different cell types from an initially homogeneous field of cells (reviewed in46,47). Thus, the Notch signaling pathway promotes cell fate “bifurcation” rather than a specific cell fate. This contribution of Notch-mediated lateral inhibition to intratumoral heterogeneity has been investigated extensively in multiple settings, including breast cancer,48 glioblastoma,49 and bladder cancer.50 To examine a potential role of the atypical NOTCH ligand DLL3 in SCLC in the classical Notch signaling circuit, we incorporated DLL3 in the lateral inhibition model with a mutual inactivation model. Our mathematical modeling predicts that DLL3 expression can affect Notch signaling in several ways. As expected, when the production rate of DLL3 exceeds that of DLL1 (βD3> βD) heterogeneity sharply decreases, indicating that DLL3 effectively reduces lateral inhibition. Within the parameter regime of heterogeneity, DLL3 expression modulates the relative number of HES1pos cells, making them sparser with increased DLL3 expression. Of interest, although very high production rates of DLL3 (βD3≫ βD) lead to inhibition of Notch activation in the entire population, over a wide range of parameters DLL3 expression maintains an intermediate level of Notch activation, which peaks near βD3 = βD. This observation reflects two seemingly opposing effects on Notch signaling. Low levels of DLL3 are sufficient to inhibit lateral inhibition, reducing or preventing the rise of HES1low cells. At very high levels, DLL3 inhibits Notch activation entirely through complete cis-inhibition. In between these two states, the trans-activation of Notch by DLL1 reinforces intermediate Notch activity, even within the parameter regime that leads to the homogeneous state. Thus, in the context of SCLC, our theoretical framework predicts that although high levels of DLL3 promote the HES1low phenotype (neuroendocrine), at lower levels they can lead to a hybrid phenotype that is neither HES1low nor HES1high. When we examined the role of DLL3 experimentally in these processes, we found that ectopic expression of DLL3 in HES1pos cells results in decreased HES1 expression, supportive of a cis-inhibitory function for DLL3. It is worth noting however, that the presence of DLL3 at the cell surface of SCLC cells could also in theory result in effects in trans on Notch signaling. This has not been described yet but should be the focus of future work, as it may affect our model and the interpretation of our experiments, as well as our general understanding of the Notch pathway.

Intriguingly, induction of DLL3 in a mouse model of SCLC revealed that this ectopic expression decreases the relative number of cells in the non-neuroendocrine (NCAMlow ICAMhigh) population and increases that of a NCAMlow ICAMlow population, without significantly altering the neuroendocrine (NCAMhigh ICAMlow) population of cancer cells. This result suggests that DLL3 inhibits the bifurcation of SCLC cell fates. In future studies, it will be interesting to examine the exact nature of the NCAMlow ICAMlow population in RPR2;Rosa26Dll3 tumors, such as whether these cells represent a precursor cell similar to lung epithelial cells during early lung development before Notch signaling is activated or another population of non-NE cells that do not require Notch.51 Our new mouse allele for DLL3 expression may also be useful in the future to investigate how DLL3 plays Notch-dependent and Notch-independent roles both in developmental processes and in cancer.

The “fit-for-purpose” approach for biomarker assays is a useful way to think how such biomarkers assays should be tailored to the intended use of the data generated by these assays.52,53 In the case of DLL3, because several therapeutic approaches currently in clinical development rely on the expression of DLL3 on SCLC cells, validating DLL3 expression at the surface of cancer cells before and during treatment could benefit patients with SCLC. Precise monitoring of DLL3 levels in SCLC cells could be used to track overall progression of SCLC and, as our data suggest, heterogeneity between SCLC cell subpopulations. PET imaging of DLL3 has been evaluated clinically using DLL3 targeting antibodies with promising results.54 However, slow normal tissue clearance and requirement of radioisotopes with long half-lives hamper clinical application of antibodies as noninvasive imaging agents.55 Here, we generated an anti-DLL3 scFv (∼1/8th the size of an antibody) labeled with a fluorophore (aDLL3AF680) with tissue penetration, allowing noninvasive optical imaging. aDLL3AF680 successfully labeled SCLC tumors in vivo with good tumor-to-normal tissue contrast in a short time frame (2 h post injection). Fast clearance may lead to a superior imaging agent for clinical application. Small size may allow better tissue penetration. Thus, scFv DLL3 binder may be a great alternative to full-length antibodies for in vivo detection and targeting of DLL3 in SCLC and other tumor types expressing this molecule on their surface.

In conclusion, our modeling and experimental data point to a role for DLL3 in the regulation of Notch signaling in SCLC. One implication of our work relates to the outcome of patients treated with therapies targeting DLL3. It is very likely that SCLC tumors may evolve to stop expressing DLL3 as a mechanism of resistance to these therapies. Although we have not performed loss-of-function experiments in mice, loss of DLL3 may, similarly to its overexpression, alter the identity of populations of SCLC cells in tumors. This may in turn lead to a specific new round of therapy, with neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine cells responding differently to different therapies, including immunotherapies activating T cells.56,57 DLL3 remains a promising target in SCLC and other small cell neuroendocrine tumors,28,58,59,60,61,62 which warrants further studies of the biology of this molecule in normal and cancer cells.

Limitations of the study

Our mathematical modeling of the role of DLL3 in SCLC heterogeneity is limited to two dimensions, and it will be important in the future to model and investigate DLL3 in three-dimensional models, where cell-cell interactions are more similar to a tumor context. Our analyses of mice with ectopic expression of DLL3 have been limited to one time point during the tumorigenic process, and it is possible that the role of DLL3 may be different at other time points or during/after therapy. Recent studies have identified multiple subtypes of SCLC driven by transcriptional regulators such as ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3, and others. For a comprehensive examination of how the Notch signaling pathway regulates SCLC heterogeneity, further classification and characterization involving more subtypes will be required.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-CD45-Pacific Blue | BioLegend | Cat#103126; RRID:AB_493535 |

| Anti-CD31-Pacific Blue | BioLegend | Cat#102422; RRID:AB_10612926 |

| Anti-TER-119-Pacific Blue | BioLegend | Cat#116232; RRID:AB_2251160 |

| Anti-CD24-APC | eBioscience | Cat#17-0242-82; RRID:AB_10870773 |

| Anti-ICAM1-PE-CY7 | BioLegend | Cat#116122; RRID:AB_2715950 |

| Anti-NCAM-PE | R&D Systems | Cat#FAB7820P; AB_2924964 |

| Anti-DLL3 | Invitrogen | Cat#PA5-23448; RRID:AB_2540948 |

| Anti-HES1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#11988; RRID:AB_2728766 |

| Anti-hexahistidine | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12698S; RRID:AB_2744546 |

| Anti-Rabbit-AF488 | Invitrogen | Cat#A11008; RRID:AB_143165 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| BL21 (DE3) electrocompetent cells | SigmaAldrich | CMC0016 |

| Endura competent cells | Lucigen | 60240-2 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| RPMI-1640 | Millipore Sigma | R0883 |

| DMEM High-Glucose medium | Hyclone | SH30243.01 |

| Bovine Growth Serum | Hyclone | SH3054103HI |

| Penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine | Gibco | 10378016 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | SigmaAldrich | A0166 |

| IPTG | Gold Biotechnology | I2481C5 |

| B-PER | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 90084 |

| Lysozyme | SigmaAldrich | L4919 |

| DNase I | Roche | 10104159001 |

| Ni-NTA agarose | Qiagen | 30210 |

| Centrifugal filters | Millipore | UFC801024 |

| AF680 succinimidyl ester | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A20008 |

| Albumin from bovine serum | SigmaAldrich | A9647-100G |

| Polyethylenimine | Polysciences | 23966-1 |

| Histo-Clear | National Diagnostics | HS-200 |

| Antigen unmasking solution | Vector Laboratories | H-3300 |

| Hematoxylin | SigmaAldrich | HHS32-1L |

| L-15 medium | Sigma | L1518 |

| Collagenase I | Sigma | C0130 |

| Collagenase II | Sigma | 6885 |

| Collagenase IV | Sigma | 5138 |

| Elastase | Worthington | LS002292 |

| RBC lysis buffer | eBioscience | 00-4333-57 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| mmPRESS®HRP Horse Anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer Detection Kit | Vector Laboratories | MP-7401 |

| ImmPRESS® Excel Amplified Polymer Staining Anti-Rabbit IgG Peroxidase Kit | Vector Laboratories | MP-7601 |

| DAB substrate kit | Vector Laboratories | SK-4100 |

| Mouse Direct PCR kit | Bimake | B40013 |

| Deposited data | ||

| MATLAB code for modeling | GitHub | https://github.com/junwkim1/DLL3_lateral_inhibition_2022 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| NCI-H82 | ATCC | NCI-H82 |

| NCI-H146 | ATCC | NCI-H146 |

| NCI-H524 | ATCC | NCI-H524 |

| HEK-293T | ATCC | 293T |

| KP11B6 | Julien Sage Laboratory | Park et al., 201163 |

| HES1pos, HES1neg cells | Julien Sage Laboratory | Lim et al., 201712 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat#005557 |

| RPR2 model | Julien Sage Laboratory | Park et al., 201163 |

| Rosa26LSL-Dll3 | GenOway | genOway/MNO/ABB55-Rosa26_Dll3 |

| Rosa26LSL-Luc | Julien Sage Laboratory | Jahchan et al., 201645 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S2 | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-puro | System Biosciences | CD510B-1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| FlowJo | FlowJo | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| MATLAB | MathWorks | https://www.mathworks.com/ |

| BZ-X Viewer 1.3.1.1 | Keyence | https://www.keyence.com/products/microscope/fluorescence-microscope/bz-x700/ |

| BZ-X Analyzer 1.4.0.1 | Keyence | https://www.keyence.com/products/microscope/fluorescence-microscope/bz-x700/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Julien Sage (julsage@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids and other reagents generated in this study will be available upon request.

Data and code availability

No datasets that are composed of standardized datatypes were generated for this study.

All MATLAB codes have been deposited at GitHub and is publicly available. The DOI is listed in the key resources table.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Mouse models

The Rb1flox/flox;Trp53flox/flox;Rbl2flox/flox(RPR2, or TKO) mouse model and the Rosa26lox-stop-lox-luciferase(R26Luc) allele have been previously described.37,45 Mice were maintained in a mixed C57BL/6;129SVJ background.

Cre-inducible DLL3-overexpressing mice (R26Dll3) were generated by knocking in a Lox-Stop-Lox-Dll3-IRES-tdTomato cassette into the Rosa26 allele. The mice were generated by GenOway via homologous recombination into the Rosa26 allele in mouse embryonic stem cells, and clones were then injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice with germline transmission. The Dll3 sequence in this allele is a cDNA/gDNA combo that retains intron 6 within the cDNA sequence to allow for expression of potential splice variants.

R26LSL-Dll3 mice were crossed to RPR2;R26LSL-Luc mice to generate RPR2;R26LSL-Dll3/LSL-Luc mice, which were then crossed to each other to generate RPR2;R26LSL-Dll3/LSL-Dll3 mice and RPR2;R26LSL-Luc/LSL-Luc littermate controls. Tumors were initiated at 8–12 weeks of age with intra-tracheal instillation of 4 × 107 plaque-forming units of Adeno-CMV-Cre (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). Animals were euthanized and tumors were collected at ∼6.5 months post-initiation, or earlier if they showed signs of respiratory distress. Mice were housed at 22°C ambient temperature with 40% humidity and a light/dark cycle of 12 h (7am – 7 pm). Mice of both sexes were used in the experiments in approximately equal numbers.

Mice were maintained according to practices prescribed by the National Institute of Health at Stanford’s Research Animal Facility (APLAC protocol #13565) and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Stanford. Additional accreditation of Stanford Research Animal Facility was provided by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Cell culture

Cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Millipore Sigma R0883) except for 293T cells and cell lines derived from RPR2;R26Luc and RPR2;R26Dll3, which were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone SH30243.01). RPMI and DMEM were supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (Hyclone SH3054103HI) and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Gibco 10378016). Cells were grown at 37°C in standard cell culture incubators. All cells were routinely tested (MycoAlert Detection Kit, Lonza) and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination.

NCI-H524, NCI-H82, and NCI-H1694 cells were purchased from ATCC. Murine KP11B6 (a negative control for tdTomato expression in Figure S3B) and HES1GFP/+ SCLC cell lines were generated in the lab and have been described.63

Method details

Plasmids/sequences

For mammalian expression of DLL3, mouse DLL3 with a C-terminal FLAG tag was cloned into the pCDH lentiviral expression vector using Endura competent cells (Lucigen 60240-2).

Synthesis of anti-DLL3 scFv

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed with anti-DLL3 scFv46 with C-terminal hexahistidine tag in pET vector by VectorBuilder. The transformed cells were grown overnight in LB agar plates with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. A single colony from each plate was inoculated in LB broth containing ampicillin and grown overnight. The primary culture was diluted 1:100 and grown at 37°C. When OD600 reached 0.5, the cells were induced with IPTG 0.5mM at 37°C for 6 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 3,500 g, and the cell pellet was resuspended with B-PER reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific 90,084) with lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL) and DNase I (50 μg/mL) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were purified using a nickel-NTA affinity column (Qiagen 30,210). Centrifugal filters with molecular 10 kDa molecular weight cutoffs (Millipore UFC801024) were used for further purification and buffer exchange into PBS. Protein purity was further analyzed using sodium dodecyl sulfatepolyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and quantified using a plate reader.

AF680 dye conjugation

Purified scFv was buffer-exchanged to 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.3) and concentrated to 3 mg/mL. AF680 succinimidyl ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific A20008) was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mg/mL and added to the protein solution to give a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. The reaction was incubated for 1hat room temperature. Unreacted dye removal and buffer exchange to PBS was done using a 10 kDa centrifugal filter.

Cell binding assays

5 × 105 human and mouse cells were incubated with 50 μL of 30 μg/mL aDLL3AF680 for 1 h in PBS with 0.1% BSA (PBSB) at 4°C. The cells were then washed twice with PBSB and analyzed by flow cytometry. For testing unlabeled aDll3scFv, cells were incubated with 50 μL of 30 μg/mL aDll3scFv for 1 h in PBSB at 4°C. The cells were washed once with PBSB, and secondary binding was performed on ice for 30 min using rabbit anti-hexahistidine antibody (Cell Signaling Technology 12698S) diluted 1:100 in PBSB. The cells were washed once with PBSB and incubated with goat anti-rabbit antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen A11008) diluted 1:100 in PBSB for 30 min on ice. The cells were then washed twice with PBSB before being analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vivo tumor imaging

1 × 106 NCI-H82 SCLC cells in 100 μL 50% Matrigel/50% RPMI media supplemented with 2% bovine growth serum were implanted into the left flank of 7- to 8-week-old NSG mice. For imaging, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and injected with 2 nmol of aDLL3AF680 in 100 μL of PBS via the tail vein. Imaging was performed at 1, 2, 3, and 6 h after protein injection, using a Lago-X system (Spectral Instruments). The near-infrared fluorescence of AF680 was detected using 615–665 nm for excitation and 695–770 nm for emission. For each imaging, a mouse treated with vehicle only was included to measure the background autofluorescence. For ex vivo imaging, mice were euthanized and organs were excised and imaged using the same excitation and emission as for the in vivo imaging.

Lentiviral transduction

5 × 105 293T cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate and left to adhere overnight in antibiotics-free DMEM High-Glucose medium supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum. Lentiviral vectors were co-transfected with delta8.2 and VSV-G lentiviral packaging vectors using PEI. The supernatant was collected after 48 h and added to the target cells. Cells were treated on day 5 with the selection agent according to the lentiviral vector used.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed using a 100 μm nozzle on BD FACSAria II (Stanford Stem Cell Institute FACS Core) and analyzed with the FACSDiva software. For single cell analysis of lung tumors, a sequential gating strategy was used to analyze cancer cells by staining with the following FACS antibodies (Figure S3F): CD45-Pacific Blue (BioLegend 103,126, 1:100), CD31-Pacific Blue (BioLegend 102,422, 1:100), TER-119-Pacific Blue (BioLegend 116232, 1:100), CD24-APC (eBioscience 17-0242-82, 1:200), ICAM1-PE-CY7 (BioLegend 116122, 1:100), and NCAM-PE (R&D Systems FAB7820P, 1:100).13 Data were analyzed using Flowjo software.

Lateral inhibition with mutual inactivation (LIMI) model with DLL3

Notch receptor (Ni) in cell i interacts with DLL1 (Dj) on the surface of a neighboring cell j. This trans-activation leads to cleavage of the Notch receptor, which frees the intracellular domain, NICD (Si) to induce expression of downstream genes such as Hes1 (Hi), described by the class lateral inhibition model.34 Notch receptor (Ni) also interact with DLL1 (Di) on the same cell surface, which leads to cis-inhibition, described by the LIMI model.38 In order to see the effect of cis-inhibition by DLL3 (D3i), Notch receptor (Ni), and DLL1 (Di) on the same cell surface, we modified LIMI by considering the following system in two-dimensional array:

Ni + Dj⇌ [NiDj] → Sitrans-activation.

Si → Hi Induction of Hes1 expression by Notch cleavage.

Hi Di Repression of DLL1

Ni + Di⇌ [NiDi] → ∅cis-inhibition between Notch and DLL1.

Ni + D3i⇌ [NiD3i] → ∅cis-inhibition between DLL3 and Notch.

The first four reactions that do not describe DLL3 are directly from LIMI.38 This model can be described by the following set of equations applied to a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of cells:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Equations (1), (2), (3) are from LIMI.41 Ni and Dj interact at a rate kt−1. Ni and Di interact at a rate kc−1. Ni, Di, and Hi are produced at a rate of βN, βD, and βH, respectively. Ni, Di, and Hi are degraded at a rate of γN, γD, and γH, respectively. Repression of Di by Hi is represented with a decreasing Hill function as a function of kDH and m. Expression of Hi by Si is represented with an increasing Hill function as a function of kHS and p. Equation 4 describes D3i, where D3i is produced, degraded, and interact with Ni at a rate βD3, γD3, and ke, respectively. These equations are used in Figures 1 and S1. For Figures S1B, S1D, and S1F, the mutual inactivation represented by was omitted.

Numerical computations were performed using MATLAB’s ode15s solver (R2017b, MathWorks) using the scripts provided by Formosa-Jordan and Sprinzak.42

Genotyping

Mice were genotyped by using the Mouse Direct PCR kit (Bimake) on DNA isolated from tails following the manufacturer’s protocol. See Table S2 for the primer sequences.

Immunostaining

Lung lobes were fixed overnight in 10% formalin in PBS before paraffin embedding. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized with Histo-Clear (National Diagnostics HS-200) and gradually rehydrated from ethanol to water. Antigen retrieval was carried out in citrate-based unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories H-3300) by microwaving at full power until boiling, then 30% power for 25 min (DLL3) or 15 min (HES1), then left to cool at room temperature for 10 min before washing with water. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubating slides in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 1 h. Sections were washed in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Tween20), blocked in 5% horse serum for 1 h, and incubated with anti-DLL3 (1:200 Invitrogen PA5-23448) or anti-HES1 (1:200 Cell Signaling Technology 11988) diluted in PBST overnight at 4°C. DLL3 was developed using ImmPRESS®HRP Horse Anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer Detection Kit (Vector Laboratories MP-7401) following the manufacturer’s protocol. HES1 was developed using ImmPRESS® Excel Amplified Polymer Staining Anti-Rabbit IgG Peroxidase Kit (Vector Laboratories MP-7601) following the manufacturer’s protocol. All sections used DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories SK-4100) for color development. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich HHS32-1L), gradually dehydrated from water to ethanol to xylene, and mounted with Refrax mounting medium (Anatech Ltd711). Sections were imaged using Keyence BZ-X700 all-in-one fluorescence microscope with BZ-X Viewer program version 1.3.1.1 and BZ-X Analyzer 1.4.0.1.

Single-cell suspension

Tumors were dissected from lungs between 5 to 6.5 months after tumor induction, finely chopped with a razor blade, and digested for 15 min at 37°C in 10 mL of L-15 medium (Sigma L1518) containing 4.25 mg/mL Collagenase I (Sigma C0130), 1.4 mg/mL Collagenase II (Sigma 6885), 4.25 mg/mL Collagenase IV (Sigma 5138), 0.625 mg/mL Elastase (Worthington LS002292), and 0.625 mg/mL DNase I (Roche 10104159). The digested mixture was filtered through a 40 μm filter and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at room temp, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 1 mL RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience 00-4333-57) for 30 s, diluted in 30 mL PBS, and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at room temp. The pelleted cells were then resuspended in 0.1% BSA/PBS for flow cytometry or in cell culture media to generate cell lines.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assayed with GraphPad Prism software. Data are represented as mean ± sd. ∗p<0.05; ∗∗p<0.01; ∗∗∗p<0.001; ∗∗∗∗p<0.0001; ns, not significant. The tests used are indicated in the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Laura Saunders and Dr. Chen-Hua Chuang at Abbvie/StemCentrx for their help during the course of this study, including with the generation of the R26LSL-Dll3 mice. We would like to also thank David S. Glass for discussions and advice, as well as Myung Chang Lee for his comments on the manuscript and Debadrita Bhattacharya for her help with single-cell isolation by flow cytometry. We also thank Pauline Chu from the Stanford Histology Service Center and all the members of the Sage lab for their help throughout this study. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (J.S.), the NIH (grants CA217450, CA213273, and CA231997 to J.S., CA257169 to J.H.K.), and the A.P. Giannini Foundation (J.W.K.). The Stanford Stem Cell Institute FACS Core was supported by an NIH S10 Shared Instrumentation Grant (1S10RR02933801).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.K., J.H.K., and J.S.; Methodology, J.W.K. (including scFv molecules) and J.H.K. (including mouse crosses and tumor studies); Formal analysis: J.W.K. (including mathematical modeling) and J.H.K.; Investigation, J.W.K. and J.H.K.; Writing – Original Draft, J.W.K., J.H.K., and J.S.; Writing – Review and Editing, J.W.K., J.H.K, and J.S.; Funding Acquisition, J.W.K., J.H.K, and J.S.; Visualization: J.W.K. and J.H.K; Supervision: J.S.

Declaration of interests

J.S. received research funding from StemCentrx/AbbVie for the development of the new Dll3 allele. J.S. has equity in, and is an advisor for, DISCO Pharmaceuticals. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: December 22, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105603.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Black J.R.M., McGranahan N. Genetic and non-genetic clonal diversity in cancer evolution. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21:379–392. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagogo-Jack I., Shaw A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamal-Hanjani M., Quezada S.A., Larkin J., Swanton C. Translational implications of tumor heterogeneity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tammela T., Sage J. Investigating tumor heterogeneity in mouse models. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2020;4:99–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudin C.M., Brambilla E., Faivre-Finn C., Sage J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021;7:3. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrows E.D., Blackburn M.J., Liu S.V. Evolving role of immunotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;86:868–874. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George J., Lim J.S., Jang S.J., Cun Y., Ozretić L., Kong G., Leenders F., Lu X., Fernández-Cuesta L., Bosco G., et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524:47–53. doi: 10.1038/nature14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gay C.M., Stewart C.A., Park E.M., Diao L., Groves S.M., Heeke S., Nabet B.Y., Fujimoto J., Solis L.M., Lu W., et al. Patterns of transcription factor programs and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:346–360.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baine M.K., Hsieh M.S., Lai W.V., Egger J.V., Jungbluth A.A., Daneshbod Y., Beras A., Spencer R., Lopardo J., Bodd F., et al. SCLC subtypes defined by ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3, and YAP1: acomprehensive immunohistochemical and histopathologic characterization. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020;15:1823–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudin C.M., Poirier J.T., Byers L.A., Dive C., Dowlati A., George J., Heymach J.V., Johnson J.E., Lehman J.M., MacPherson D., et al. Molecular subtypes of small cell lung cancer: a synthesis of human and mouse model data. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:289–297. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson S.C., Metcalf R.L., Trapani F., Mohan S., Antonello J., Abbott B., Leong H.S., Chester C.P.E., Simms N., Polanski R., et al. Vasculogenic mimicry in small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13322. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim J.S., Ibaseta A., Fischer M.M., Cancilla B., O'Young G., Cristea S., Luca V.C., Yang D., Jahchan N.S., Hamard C., et al. Intratumoural heterogeneity generated by Notch signalling promotes small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2017;545:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature22323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calbo J., van Montfort E., Proost N., van Drunen E., Beverloo H.B., Meuwissen R., Berns A. A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Augert A., Eastwood E., Ibrahim A.H., Wu N., Grunblatt E., Basom R., Liggitt D., Eaton K.D., Martins R., Poirier J.T., et al. Targeting NOTCH activation in small cell lung cancer through LSD1 inhibition. Sci. Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau2922. eaau2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon M.C., Proost N., Song J.Y., Sutherland K.D., Zevenhoven J., Berns A. Paracrine signaling between tumor subclones of mouse SCLC: a critical role of ETS transcription factor Pea3 in facilitating metastasis. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1587–1592. doi: 10.1101/gad.262998.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shue Y.T., Drainas A.P., Li N.Y., Pearsall S.M., Morgan D., Sinnott-Armstrong N., Hipkins S.Q., Coles G.L., Lim J.S., Oro A.E., et al. A conserved YAP/Notch/REST network controls the neuroendocrine cell fate in the lungs. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2690. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30416-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ireland A.S., Micinski A.M., Kastner D.W., Guo B., Wait S.J., Spainhower K.B., Conley C.C., Chen O.S., Guthrie M.R., Soltero D., et al. MYC drives temporal evolution of small cell lung cancer subtypes by reprogramming neuroendocrine fate. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:60–78.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutherland K.D., Ireland A.S., Oliver T.G. Killing SCLC: insights into how to target a shapeshifting tumor. Genes Dev. 2022;36:241–258. doi: 10.1101/gad.349359.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart C.A., Gay C.M., Xi Y., Sivajothi S., Sivakamasundari V., Fujimoto J., Bolisetty M., Hartsfield P.M., Balasubramaniyan V., Chalishazar M.D., et al. Single-cell analyses reveal increased intratumoral heterogeneity after the onset of therapy resistance in small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer. 2020;1:423–436. doi: 10.1038/s43018-019-0020-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulman M.P., Kusumi K., Frayling T.M., McKeown C., Garrett C., Lander E.S., Krumlauf R., Hattersley A.T., Ellard S., Turnpenny P.D. Mutations in the human delta homologue, DLL3, cause axial skeletal defects in spondylocostal dysostosis. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:438–441. doi: 10.1038/74307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusumi K., Sun E.S., Kerrebrock A.W., Bronson R.T., Chi D.C., Bulotsky M.S., Spencer J.B., Birren B.W., Frankel W.N., Lander E.S. The mouse pudgy mutation disrupts Delta homologue Dll3 and initiation of early somite boundaries. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:274–278. doi: 10.1038/961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunwoodie S.L., Henrique D., Harrison S.M., Beddington R.S. Mouse Dll3: a novel divergent Delta gene which may complement the function of other Delta homologues during early pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development. 1997;124:3065–3076. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladi E., Nichols J.T., Ge W., Miyamoto A., Yao C., Yang L.T., Boulter J., Sun Y.E., Kintner C., Weinmaster G. The divergent DSL ligand Dll3 does not activate Notch signaling but cell autonomously attenuates signaling induced by other DSL ligands. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:983–992. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geffers I., Serth K., Chapman G., Jaekel R., Schuster-Gossler K., Cordes R., Sparrow D.B., Kremmer E., Dunwoodie S.L., Klein T., Gossler A. Divergent functions and distinct localization of the Notch ligands DLL1 and DLL3 in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman G., Sparrow D.B., Kremmer E., Dunwoodie S.L. Notch inhibition by the ligand DELTA-LIKE 3 defines the mechanism of abnormal vertebral segmentation in spondylocostal dysostosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:905–916. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serth K., Schuster-Gossler K., Kremmer E., Hansen B., Marohn-Köhn B., Gossler A. O-fucosylation of DLL3 is required for its function during somitogenesis. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123776. e0123776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson B.R., Hartman B.H., Ray C.A., Hayashi T., Bermingham-McDonogh O., Reh T.A. Acheate-scute like 1 (Ascl1) is required for normal delta-like (Dll) gene expression and notch signaling during retinal development. Dev. Dyn. 2009;238:2163–2178. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunders L.R., Bankovich A.J., Anderson W.C., Aujay M.A., Bheddah S., Black K., Desai R., Escarpe P.A., Hampl J., Laysang A., et al. A DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor-initiating cells in vivo. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac9459. 302ra136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson M.L., Zvirbule Z., Laktionov K., Helland A., Cho B.C., Gutierrez V., Colinet B., Lena H., Wolf M., Gottfried M., et al. Rovalpituzumab tesirine as a maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with extensive-stage-SCLC: results from the phase 3 MERU study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:1570–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malhotra J., Nikolinakos P., Leal T., Lehman J., Morgensztern D., Patel J.D., Wrangle J.M., Curigliano G., Greillier L., Johnson M.L., et al. A phase 1-2 study of rovalpituzumab tesirine in combination with nivolumab plus or minus ipilimumab in patients with previously treated extensive-stage SCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:1559–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackhall F., Jao K., Greillier L., Cho B.C., Penkov K., Reguart N., Majem M., Nackaerts K., Syrigos K., Hansen K., et al. Efficacy and safety of rovalpituzumab tesirine compared with topotecan as second-line therapy in DLL3-high SCLC: results from the phase 3 TAHOE study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021;16:1547–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hipp S., Voynov V., Drobits-Handl B., Giragossian C., Trapani F., Nixon A.E., Scheer J.M., Adam P.J. A bispecific DLL3/CD3 IgG-like T-cell engaging antibody induces antitumor responses in small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:5258–5268. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakes A.L., An D.D., Gauny S.S., Ansoborlo C., Liang B.H., Rees J.A., McKnight K.D., Karsunky H., Abergel R.J. Evaluating (225)Ac and (177)Lu radioimmunoconjugates against antibody-drug conjugates for small-cell lung cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2020;17:4270–4279. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giffin M.J., Cooke K., Lobenhofer E.K., Estrada J., Zhan J., Deegen P., Thomas M., Murawsky C.M., Werner J., Liu S., et al. AMG 757, a half-life extended, DLL3-targeted bispecific T-cell engager, shows high potency and sensitivity in preclinical models of small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27:1526–1537. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tully K.M., Tendler S., Carter L.M., Sharma S.K., Samuels Z.V., Mandleywala K., Korsen J.A., Delos Reyes A.M., Piersigilli A., Travis W.D., et al. Radioimmunotherapy targeting delta-like ligand 3 in small cell lung cancer exhibits antitumor efficacy with low toxicity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;28:1391–1401. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohsawa R., Kageyama R. Regulation of retinal cell fate specification by multiple transcription factors. Brain Res. 2008;1192:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collier J.R., Monk N.A., Maini P.K., Lewis J.H. Pattern formation by lateral inhibition with feedback: a mathematical model of delta-notch intercellular signalling. J. Theor. Biol. 1996;183:429–446. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sprinzak D., Lakhanpal A., Lebon L., Santat L.A., Fontes M.E., Anderson G.A., Garcia-Ojalvo J., Elowitz M.B. Cis-interactions between Notch and Delta generate mutually exclusive signalling states. Nature. 2010;465:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bray S.J. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller A.C., Lyons E.L., Herman T.G. cis-Inhibition of Notch by endogenous Delta biases the outcome of lateral inhibition. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1378–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sprinzak D., Lakhanpal A., LeBon L., Garcia-Ojalvo J., Elowitz M.B. Mutual inactivation of Notch receptors and ligands facilitates developmental patterning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002069. e1002069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Formosa-Jordan P., Sprinzak D. Modeling Notch signaling: a practical tutorial. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1187:285–310. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1139-4_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weisser N.E., Hall J.C. Applications of single-chain variable fragment antibodies in therapeutics and diagnostics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009;27:502–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peltomaa R., Barderas R., Benito-Peña E., Moreno-Bondi M.C. Recombinant antibodies and their use for food immunoanalysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022;414:193–217. doi: 10.1007/s00216-021-03619-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jahchan N.S., Lim J.S., Bola B., Morris K., Seitz G., Tran K.Q., Xu L., Trapani F., Morrow C.J., Cristea S., et al. Identification and targeting of long-term tumor-propagating cells in small cell lung cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;16:644–656. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sjöqvist M., Andersson E.R. Do as I say, Not(ch) as I do: lateral control of cell fate. Dev. Biol. 2019;447:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chitnis A.B. The role of Notch in lateral inhibition and cell fate specification. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1995;6:311–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bocci F., Gearhart-Serna L., Boareto M., Ribeiro M., Ben-Jacob E., Devi G.R., Levine H., Onuchic J.N., Jolly M.K. Toward understanding cancer stem cell heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:148–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815345116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lim K.J., Brandt W.D., Heth J.A., Muraszko K.M., Fan X., Bar E.E., Eberhart C.G. Lateral inhibition of Notch signaling in neoplastic cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1666–1677. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torab P., Yan Y., Ahmed M., Yamashita H., Warrick J.I., Raman J.D., DeGraff D.J., Wong P.K. Intratumoral heterogeneity promotes collective cancer invasion through NOTCH1 variation. Cells. 2021;10:3084. doi: 10.3390/cells10113084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong D., Knelson E.H., Li Y., Durmaz Y.T., Gao W., Walton E., Vajdi A., Thai T., Sticco-Ivins M., Sabet A.H., et al. Plasticity in the absence of NOTCH uncovers a RUNX2-dependent pathway in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82:248–263. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee J.W., Weiner R.S., Sailstad J.M., Bowsher R.R., Knuth D.W., O'Brien P.J., Fourcroy J.L., Dixit R., Pandite L., Pietrusko R.G., et al. Method validation and measurement of biomarkers in nonclinical and clinical samples in drug development: a conference report. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:499–511. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathews J., Amaravadi L., Eck S., Stevenson L., Wang Y.-M.C., Devanarayan V., Allinson J., Lundsten K., Gunsior M., Ni Y.G. Springer; 2022. Best Practices for the Development and Fit-For-Purpose Validation of Biomarker Methods: AConference Report. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma S.K., Pourat J., Abdel-Atti D., Carlin S.D., Piersigilli A., Bankovich A.J., Gardner E.E., Hamdy O., Isse K., Bheddah S., et al. Noninvasive interrogation of DLL3 expression in metastatic small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3931–3941. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei W., Rosenkrans Z.T., Liu J., Huang G., Luo Q.Y., Cai W. ImmunoPET: concept, design, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:3787–3851. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hiatt J.B., Sandborg H., Garrison S.M., Arnold H.U., Liao S.Y., Norton J.P., Friesen T.J., Wu F., Sutherland K.D., Rienhoff H.Y., et al. Inhibition of LSD1 with bomedemstat sensitizes small cell lung cancer to immune checkpoint blockade and T cell killing. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;28:4551. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen E.M., Taniguchi H., Chan J.M., Zhan Y.A., Chen X., Qiu J., de Stanchina E., Allaj V., Shah N.S., Uddin F., et al. Targeting lysine-specific demethylase 1 rescues major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation and overcomes programmed death-ligand 1 blockade resistance in SCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022;17:1014–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puca L., Gavyert K., Sailer V., Conteduca V., Dardenne E., Sigouros M., Isse K., Kearney M., Vosoughi A., Fernandez L., et al. Delta-like protein 3 expression and therapeutic targeting in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav0891. eaav0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hermans B.C.M., Derks J.L., Thunnissen E., van Suylen R.J., den Bakker M.A., Groen H.J.M., Smit E.F., Damhuis R.A., van den Broek E.C., et al. PALGA-Group DLL3 expression in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and association with molecular subtypes and neuroendocrine profile. Lung Cancer. 2019;138:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liverani C., Bongiovanni A., Mercatali L., Pieri F., Spadazzi C., Miserocchi G., Di Menna G., Foca F., Ravaioli S., De Vita A., et al. Diagnostic and predictive role of DLL3 expression in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2021;32:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie H., Kaye F.J., Isse K., Sun Y., Ramoth J., French D.M., Flotte T.J., Luo Y., Saunders L.R., Mansfield A.S. Delta-like protein 3 expression and targeting in merkel cell carcinoma. Oncologist. 2020;25:810–817. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sano R., Krytska K., Tsang M., Erickson S.W., Teicher B.A., Saunders L., Jones R.T., Smith M.A., Maris J.M., Mosse Y.P. Abstract LB-136: pediatric Preclinical Testing Consortium evaluation of a DLL3-targeted antibody drug conjugate rovalpituzumab tesirine, in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78 doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-lb-136. LB-136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park K.S., Martelotto L.G., Peifer M., Sos M.L., Karnezis A.N., Mahjoub M.R., Bernard K., Conklin J.F., Szczepny A., Yuan J., et al. A crucial requirement for Hedgehog signaling in small cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1504–1508. doi: 10.1038/nm.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets that are composed of standardized datatypes were generated for this study.

All MATLAB codes have been deposited at GitHub and is publicly available. The DOI is listed in the key resources table.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.