Abstract

Objectives:

In 2014, the number of Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC) programs in the U.S. greatly expanded. The proliferation of CSC programs was likely due in part to the availability of Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) set-aside funds for first-episode psychosis. The current study provides information about 215 CSC programs across 44 states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories that received funding through the MHBG set-aside program in 2018.

Methods:

Of the 244 MHBG-funded CSC programs identified through State Mental Health Authorities, leadership at 88% of the programs participated in an online survey.

Results:

Sixty-nine percent of the CSC programs were initiated after 2014. Over 90% of programs included services that are consistent with federal guidance. CSC programs evidenced greater variability in training received, program size, and enrollment criteria.

Conclusion:

The current study highlights that clear federal guidance can help shape national implementation efforts, although decisions at the state and local level can influence how implementation occurs. The administration of federal funds by the states for CSC may be a strategy adapted for the rollout of other behavioral health interventions. Future studies could investigate factors that may shape national dissemination efforts, such as leadership within the state, funding, availability of programs established prior to the influx of funding, and considerations around sustainability after the funding is no longer available.

Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC) programs have recently expanded across the U.S. In 2008, two states reported using federal funds to support 12 CSC programs (1, 2). Today, the Early Assessment and Support Alliance (EASA) National Early Psychosis Directory notes that 344 CSC programs exist across every state and four U.S. territories. The multi-billion dollar federal investment through the National Institute of Mental Health’s (NIMH) Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) studies and the Mental Health Block Grant set-aside for early psychosis likely prompted in part the proliferation of CSC programs across the U.S. (3).

CSC is a team-based program that includes a set of evidence-based outpatient services designed to address the needs of individuals experiencing early psychosis or first-episode psychosis (4–9). By intervening early, CSC seeks to reduce symptoms of psychosis and improve functioning and quality of life (6–7). Although models of CSC (e.g., OnTrack, EASA, NAVIGATE) vary in selected ways, NIMH identified common service components for CSC (10–11). The components include having a designated Team Lead, and the provision of the following services provided in an evidence-based manner: case management; individual or group psychotherapy; supported employment; supportive education; family psychoeducation; family support; and psychopharmacology.

The rapid growth of CSC is unique compared to other evidence-based interventions. A major difference between most behavioral health treatment programs and CSC is that in 2014, states received federal Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) set-aside funds for first-episode psychosis treatment (11). The MHBG program is a formula-based state grant program in which federal funds are distributed to states and territories, and the amount varies based on specified economic and demographic factors. In 2014, Congress included a five percent set-aside in the MHBG to support states in developing early intervention services for psychosis, including CSC (11). States could provide funding to existing CSC programs or fund new CSC programs. There were no requirements regarding the type of provider organization the funds could go to, or whether the organization had previously received any federal funding. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act increased the set-aside to 10% and included a supplement (12). The 2016 federal guidance noted, “States can implement models which have demonstrated efficacy, including the range of services and principles identified by NIMH via its Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) initiative” (12). Although Federal guidance encouraged states to implement the range of services and principles outlined in RAISE (11–14), they were not required to do so. States were also given freedom to select which CSC model to implement, what types of services and training activities to fund, and what program admission criteria to require. There were no “required” services and no penalty for failing to offer a minimum number of CSC services.

By 2018, there were 244 CSC programs in the U.S. funded by the MHBG set-aside (3). Although past reports have described these programs (3, 15), no studies to date have surveyed program leadership from the entire national sample of MHBG funded CSC programs. Additionally, existing information about CSC programs was gathered in part through interviews with State Mental Health Authorities (SMHA), which may not have had access to detailed information about CSC program characteristics. Therefore, we know little about the implementation of these programs. As more outcome data become available and states increase support for expansion of CSC, understanding program characteristics and their correlates will likely have implications for the ongoing expansion and quality of CSC programs. Examining aspects of CSC programming will be timely given the influx of 2021 funding to states through the COVID-19 Relief Supplement and increased MHBG set-aside funding that will once again double the funds to support the implementation of CSC. Questions that require consideration include whether programs are providing evidence-based services and whether federal support for CSC implementation is a viable approach for disseminating important mental health programs nationally. The current study reports the results of a 2018 survey of CSC programs funded by the MHBG set-aside for first-episode psychosis in that year.

METHODS

Design, sampling, and procedure

As part of a multi-method study examining CSC programs receiving MHBG set-aside funds, we collected data using a 28-item online survey assessing CSC program characteristics, such as program size, client capacity, duration of care, referral sources, services offered, and outcomes measurement. As the MHBG set-aside funds are administered by states, CSC programs were identified by SMHAs as part of their federal reporting (3). SMHAs identified programs that received set-aside funds and used at least 1% of the MHBG set-aside funding to cover CSC program costs. Additional funding sources used by CSC programs could include Medicaid, private insurance, other state funds, local funding, endowments, and grants. In rare instances, study staff spoke directly with SMHA staff members to clarify CSC program eligibility for the study and to confirm that program costs were supported by MHBG funds.

We collected data between February 2018 and June 2018. Respondents were program leadership at 244 MHBG-funded CSC clinics identified by SMHAs (3). Of the 244 CSC programs recruited for the survey, 215 completed the survey (88%). Programs in this sample were located across 44 states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories. The online survey included informed consent that was completed before the initiation of the survey. To minimize reporting bias, the informed consent and letter of invitation to CSC program leadership emphasized that data would be reported at the aggregate level, and SMHAs would not see the individual survey responses by CSC program staff. Summary statistics and descriptive analyses using SAS 9.4 were used to describe characteristics and patterns of CSC programming. Responses to survey items addressed the timeframe for the start of the CSC program, services offered, training, program capacity, current client enrollment, and enrollment criteria. All aspects of this study were reviewed and approved by the [name omitted] research ethics board.

RESULTS

Initiation of CSC programs.

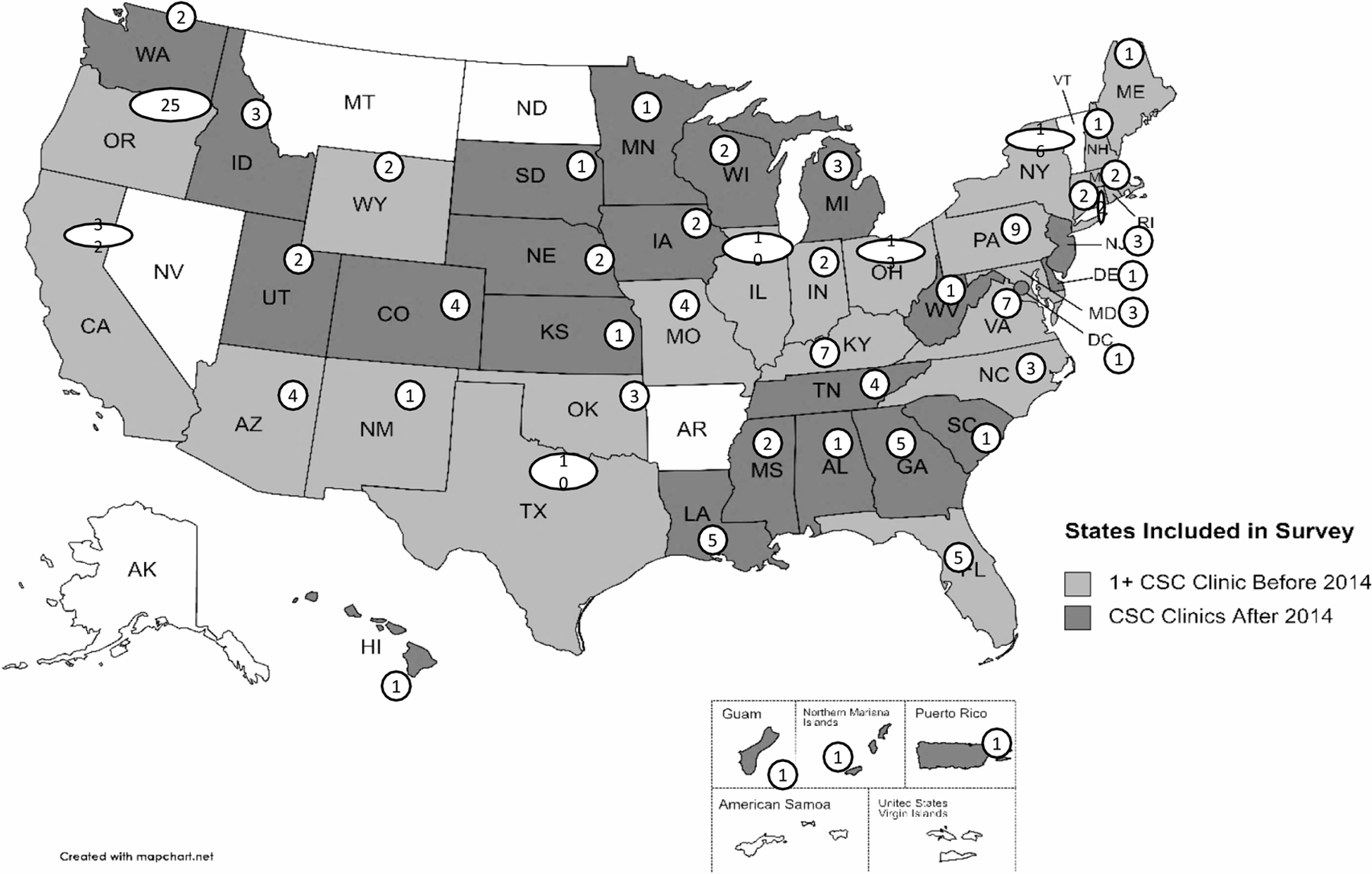

As shown in Figure 1, the survey includes 215 CSC programs across 44 states, and three U.S. territories. One-third of CSC programs in the study (31%; 67/215) reported providing services for first-episode psychosis before 2014 when the MHBG set-aside was initiated. Most CSC programs were initiated in 2014 or later (69%; 148/215). Among the group of 148 programs that began after 2014, over half were initiated in 2016 or later (56%; 83/148), corresponding with the doubling of MHBG set-aside funding in 2016.

Figure 1. Number of CSC programs from each state represented in the survey.

The map shows the 215 CSC programs across 44 states and three U.S. territories that responded to the survey. Almost 70% of CSC programs surveyed were initiated in 2014 or later (69%; 148/215).

Services Provided by CSC Programs.

The majority of programs reportedly offered core components of CSC as defined by NIMH guidance (see Table 1), including having a team lead, case management, family education/support, low dose anti-psychotic medication treatment, supported employment and supported education (11). The majority also reported offering additional services, including crisis intervention services, peer support services, primary care coordination, and co-occurring substance use services.

Table 1.

Percent of 209 CSC Programs Offering Specific Service Components

| Service Components | % of CSC Programs (N=209) |

|---|---|

| Team Lead | 94 |

| Case Management | 98 |

| Family Education/Support | 98 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 96 |

| Cognitive behavior-oriented psychotherapy | 93 |

| Supported employment services | 93 |

| Supported education services | 86 |

| Crisis intervention services | 83 |

| Peer support services | 72 |

| Primary care coordination | 71 |

| Co-occurring substance use services | 71 |

Training on CSC Service Delivery.

CSC program leadership reported receiving technical assistance and training on various CSC models, including OnTrackNY (32%; 67/211), NAVIGATE (23%; 49/211), EASA (18%; 37/211), FIRST (10%; 21/211), PIER (5%; 10/211), other programs (18%; 37/211), or a combination of two or more (11%, 23/211). Six percent received no technical assistance or training.

Client Enrollment.

Across all programs, the total capacity for client enrollment was 8255. CSC programs most commonly noted that their maximum client capacity was between 21 – 30 clients (27%; 57/214) or 41–100 clients (26%; 56/214). Respondents reported that their client count at the time of the survey was lower than capacity, with 29 percent of the programs reporting current enrollment as being less than 10 clients (29%; 63/214). Only 14% of programs were at full capacity (14%; 29/214); nearly a third were at 50% capacity or less (31%; 66/ 214); and a tenth were at 25% capacity or less (11%; 24/214).

Enrollment Criteria.

CSC program leadership reported enrolling clients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (99%; 207/210), schizoaffective disorder (95%; 200/210), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (92%; 194/210), schizophreniform disorder (80%; 167/210), affective disorders with psychotic features (57%; 120/210), delusional disorder (50%; 104/210), and post-traumatic stress disorder (25%; 53/210). Nineteen percent (19%; 41/214) of programs had an enrollment criterion about whether clients had been prescribed antipsychotic medication prior to enrollment. Most programs had client enrollment criteria that included a measure of duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) (84%; 179/214), and nearly half indicated that their inclusion criterion for DUP was 13 to 24 months (48%; 85/179). Client age for inclusion in CSC clinics ranged from 10 to 65 years old (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent of programs with eligibility criteria for minimum and maximum client age

| Minimum Age for Program Eligibility | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| 10–13 years | 29 | 14 |

| 14–15 years | 111 | 54 |

| 16–18 years | 66 | 32 |

| Maximum Age for Program Eligibility | ||

| N | % | |

| 15–29 years | 72 | 36 |

| 30–39 years | 103 | 51 |

| 40+ years | 27 | 13 |

DISCUSSION

Today there are over 340 CSC programs located in every state in the U.S. Before the MHBG set-aside funding in 2014, treatment programs for first-episode psychosis were slow to develop, as public policy prioritized services for individuals who were already disabled by mental illness. CSC emerged as a federal priority based on growing scientific evidence accumulated from other countries (e.g., Australia, Canada, United Kingdom) suggesting the importance of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis and treating the first-episode of psychosis with evidence-based services using a team-based approach (6).

Information regarding the growth in the number of U.S. CSC programs over time remains limited. In 2008, two states supported CSC programs (1–2). By 2014, 25 states had CSC or early psychosis programs, and among those 25 states, 20 were involved in the NIMH RAISE studies (11). Subsequent reports come from the SAMHSA funded State Snapshots that collect information from the State Mental Health Authorities within each state and U.S. territory (3, 15). The current survey is the first to reach out to and collect information directly from the MHBG set-aside funded programs and document program-level data.

The development of CSC programs in U.S. academic settings, positive results from RAISE, and increasing Congressional concern about psychotic disorders among young people led to legislation expanding the MHBG and creating the set-aside. As was the case with earlier efforts in federal mental health policy, such as the community mental health legislation of the 1960s or the community support reforms of the 1980s, the expansion of CSC programs in the U.S. reflects how federal leadership can balance state and local innovation with federal incentives to shape service delivery (16).

The current study examined the characteristics of 215 CSC federally funded programs. The CSC programs surveyed were identified by SMHAs as receiving MHBG set-aside funds in 2018, and they represent a unique group of service organizations that are defined within this study by the funding mechanism that supports them. The current study strongly suggests that the MHBG set-aside funding played an important role in stimulating the emergence of CSC programs in the U.S. A third of the CSC programs across 23 states predate the 2014 MHBG set-aside, suggesting that although they received MHBG set-aside funds at the time of the survey, they were not created as a result of the MHBG set-aside funds. This finding is consistent with NIMH State data that show CSC programming available in approximately 25 states before the availability of the MHBG set-aside funding. In the current study, nearly 70% of CSC programs were initiated in 2014 or later, after the initial MHBG set-aside allocation. Of the programs that began in 2014 or later, more than 50% started after 2016 when the MHBG set-aside funds were increased.

Although this study does not directly test whether the MHBG set-aside funding led to the diffusion of CSC programs within the U.S., the results suggest that set-aside funds were influential in the startup of these programs. Further, the literature shows that the lack of cohesive funding mechanisms that cover CSC’s intensive, comprehensive, individualized, team-based, multi-service approach poses a challenge to initiating programs in the U.S. (17–19). For example, Medicaid and private insurance do not fund many components of CSC programs, such as team meetings, supported education, and family education. The MHBG set-aside funds enable provider organizations to conduct start-up activities such as training of staff, conducting outreach activities in the community to identify potential clients and providing the full array of CSC services. This funding, along with the federal mandate, likely influenced the proliferation of these programs.

Ways in which programs conformed to federal guidance.

The programs confirmed that they were CSC programs when they completed the survey, but no CSC fidelity assessment was completed to confirm the designation. Despite these limitation and the risk of social response bias, the MHBG set-aside funded CSC programs show great similarities. In all likelihood, federal guidance was effective in shaping the CSC programs despite not being a requirement for states to follow. For example, states received access to materials developed through the NIMH-funded RAISE initiative, which included listings of CSC Core Services. Over 90% of CSC programs reported providing each of these core CSC components. Also consistent with federal guidance, most of the CSC programs had client enrollment criteria that included a measure of untreated psychosis (DUP) before entering the program (10). The majority of programs also reported offering crisis intervention services, peer support services, primary care coordination, and co-occurring substance use services. The reason for this is unclear. Certainly, the components of CSC such as supported employment, family education, and peer support services are available in most states, independent of CSC programs. It may be that the majority of states were already placing high priority on these services, and thus it was easier to incorporate these services as part of CSC. Alternatively, the survey question may have been misinterpreted such that respondents included the availability of services offered by the outpatient clinic associated with the CSC program, rather than the CSC program itself. Future studies should further investigate the role of the state for influencing the availability of these service components.

Ways in which programs were more likely to vary.

Where federal guidance was less prescriptive, CSC programs differed. For example, federal guidance did not specify which CSC program model to adopt (e.g., NAVIGATE, EASA, OnTrackNY). As such, states and programs had flexibility to select the type of technical assistance and training clinics received. No more than a third of the CSC programs selected any of the models, with OnTrackNY model being used by the most CSC programs. Eleven percent of the CSC programs had training in multiple models. Similarly, client age for inclusion in CSC programs ranged from 10 – 65 years old. Approximately half of the CSC programs had a minimum age for clients as 14 – 15 years old. The majority of the clinics reported that their maximum enrollment age was between 30 – 39 years. It should be noted that the older age range falls out of the norm reported as effective in CSC clinical trials and systematic reviews (4, 11, 20).

Broader applicability of set-aside funding.

Regardless of the heterogeneity among the CSC programs, it appears that the use of MHBG set-aside funds that are administered by states is an effective approach to promulgate specific mental health interventions nationally. Admittedly, use of federal funding to increase the availability of mental health treatment is not new: Federal funds have been in place since the 1960’s when the federal Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) program was launched and grant funding was provided directly to Centers willing to deliver essential services defined by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (17, 21). Since the 1980’s, states have taken a larger role in shaping mental health services, guiding availability of services through State Medicaid plans determining benefit design and reimbursements, and administration of the Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG). Recent examples of federal policy influence include the government’s role in defining the essential services within the Affordable Care Act, the roll out of the Certified Community Behavioral Health Center programs, and most recently the COVID-19 Relief supplemental funds which can be used to develop and support evidence-based crisis services for those adults and youth with mental illnesses (22–24). In 2020 and 2021, states received additional federal funds for their CSC programming: $82.5 million through the MHBG COVID-19 Supplement and $150 million through the American Rescue Plan (ARP). States have two years to expend the COVID-19 supplement and until September 2025 to expend the ARP funds. How states choose to direct federal funding for CSC will continue to shape implementation. The current survey suggests that research-based federal guidance can play a vital role in shaping how these dollars are used.

Future studies can investigate how the CSC programs funded by the MHBG set-aside funds compare with those that do not receive these funds. It would be useful to assess whether the amount of MHBG set-aside funding, or the percentage of overall CSC program costs covered by MHBG set-aside funding, influences the services offered or other program characteristics. Further, it would be valuable to investigate how decision-making at the state level occurs, regarding which clinics are funded and which CSC models are selected for implementation. These levers of decision-making may be important in how CSC programs function. Finally, the current study did not investigate the quality of these programs and whether CSC is being offered with fidelity to a certain model. This gap represents an important avenue of further research

Conclusion

The current study of CSC programs funded through the MHBG set-aside program in 2018 highlights that federal funding and guidance may help shape national implementation efforts. This approach to the administration of federal funds by the states for CSC may inform the rollout of other behavioral health interventions, although more research is needed to determine factors that may shape national dissemination efforts and program characteristics. Additional studies could focus on the influence of various factors, including state leadership, age of the program, the relative amount and ways that the MHBG set-aside funds are used, and how the core components of CSC are offered.

Highlights:

The spread of Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC) throughout the U.S. can likely be attributed in part to federal funding and guidance, specifically the Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) set-aside program that requires every state and U.S. territory to provide first-episode psychosis treatment.

The current study explores characteristics of 215 CSC programs funded through the MHBG program in 2018.

More than two-thirds of CSC programs in this study were initiated after 2014, corresponding with the initial MHBG set-aside funding.

CSC programs show commonality in services offered, which were defined by federal guidance, but differ on dimensions such as size of program, enrollment criteria, and training.

Previous Presentations:

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Mental Health Services Research Conference, Bethesda, MD. August 1–2, 2018. Oral Presentation

American Public Health Association (APHA) San Diego, CA. November 10–14, 2018. Poster presentation.

Acknowledgements:

The MHBG 10% Study was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Task Order No. HHSS283201200011I/HHSS28342008T, Reference No. 283–12-1108.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. George, Ghose, Goldman, O’Brien, Daley, Dixon & Rosenblatt have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.FY2008 State Mental Health Block Grant State Plans Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinssen R. Early psychosis care: National Landscape and Scientific Opportunities Presentation to McClean Hospital Grand Rounds Lecture Series, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, October 29, 2020. https://www.mcleanhospital.org/video/lecture-early-psychosis-care-national-landscape-and-scientific-opportunities [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutterman T, Kazandjian M, Urff J: Snapshot of State Plans for Using the Community Mental Health Block Grant 10 Percent Set-Aside to Address First Episode Psychosis National State Mental Health Program Directors National Research Institute, Falls Church, VA, 2018. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Snapshot_of_State_Plans.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correll C, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. : Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 2018; 75:555–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon L, Goldman H, Bennet M, et al. : Implementing Coordinated Specialty Care for early psychosis: The RAISE Connection Program. Psychiatr Serv 2015; 66:691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon L, Goldman H, Srihari V, et al. : Transforming the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States: The RAISE initiative. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2018; 14:6.1–6.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. : Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173:362–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penn D, Waldheter E, Perkins D, et al. : Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: A research update. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:2220–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randall J, Vokey S, Loewen H, et al. : A systematic review of the effect of early interventions for psychosis on the usage of inpatient services. Schizophr Bull 2015; 41:1379–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azrin ST, Goldstein AB, Heinssen RK. Early intervention for psychosis: The recovery after an initial schizophrenia episode project. Psychiatr Ann 2015; 45:548–553 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinssen RK, Goldstein AB, Azrin ST. Evidence-based treatments for first episode psychosis: Components of coordinated specialty care National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, 2015. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/nimh-white-paper-csc-for-fep_147096.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidance for Revision of the FY2016–2017 Block Grant Application for the New 10 Percent Set-Aside Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD, 2016. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/mhbg-5-percent-set-aside-guidance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNamara K, Mendon S, Piscitelli S, et al. : Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis, Manual I: Outreach and Recruitment National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, 2009. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/csc-for-fep-manual-i-outreach-and-referral.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennet M, Piscitelli S, Goldman H, et al. : Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis, Manual II: Implementation National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, 2009.https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/csc-for-fep-manual-ii-implementation-manual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutterman T, Kazandjian M, Shea P: Snapshot of State Plans for Using the Community Mental Health Block Grant (MHBG) Ten Percent Set-Aside for Early Intervention Programs National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors National Research Institute, Falls Church, VA, 2016. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Information_Guide-Snapshot_of_State_Plans_Revision.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grob GN, Goldman HH: The Dilemma of Federal Mental Health Policy: Radical Reform of Incremental Change? New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman H, Karakus M, Frey W, et al. : Financing first episode psychosis services in the United States. Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64:506–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao Y, Papp M, Lee R, et al. : Financing early psychosis intervention programs: Provider organization perspectives. Psychiatr Serv 2021; 72:1134–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shern D, Neylon K, Kazandjian M, et al. : Information Brief: Use of Medicaid to Finance Coordinated Specialty Care Services for First-Episode Psychosis National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors National Research Institute, Falls Church, VA, 2017. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Medicaid_brief.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitborde NJK, Moe AM, Ered A, et al. : Optimizing psychosocial interventions in first-episode psychosis: Current perspectives and future directions. Psychol Res Behav Manag, 2017; 10:119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley HA, Sharfstein SS: Madness and the Government: Who Cares for the Mentally Ill? Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Press, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds 31 Cfr Part 35, Rin 1505–Ac77 U.S. Department of the Treasury Fed Regist; May 2021; 86:93 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-05-17/pdf/2021-10283.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mechanic D, Olfson M: The Relevance of the Affordable Care Act for Improving Mental Health Care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016; 12:515–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Stanhope V, Matthew E, et al. : A Brief Report on Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics Demonstration Program, Soc Work Ment Health 2021; 6:534–541 [Google Scholar]