Abstract

Introduction:

This study was undertaken to gain mechanistic information about bone repair using the bone repletion model in aged Balb/cBy mice.

Materials and Methods:

One-month-old (young) mice were fed a calcium-deficient diet for 2 weeks and 8-month-old (adult) and 21- to 25-month-old (aged) female mice for 4 weeks during depletion, which was followed by feeding a calcium-sufficient diet for 16 days during repletion. To determine if prolonged repletion would improve bone repair, an additional group of aged mice were repleted for 4 additional weeks. Control mice were fed calcium-sufficient diet throughout. In vivo bone repletion response was assessed by bone mineral density gain and histomorphometry. In vitro response was monitored by osteoblastic proliferation, differentiation, and senescence.

Results:

There was no significant bone repletion in aged mice even with an extended repletion period, indicating an impaired bone repletion. This was not due to an increase in bone cell senescence or reduction in osteoblast proliferation, but to dysfunctional osteoblastic differentiation in aged bone cells. Osteoblasts of aged mice had elevated levels of cytosolic and ER calcium, which were associated with increased Cav1.2 and CaSR (extracellular calcium channels) expression but reduced expression of Orai1 and Stim1, key components of Stored Operated Ca2+ Entry (SOCE). Activation of Cav1.2 and CaSR leads to increased osteoblastic proliferation, but activation of SOCE is associated with osteoblastic differentiation.

Conclusions:

The bone repletion mechanism in aged Balb/cBy mice is defective that is caused by an impaired osteoblast differentiation through reduced activation of SOCE.

Keywords: Bone repletion, aging, calcium channels, calcium receptor, stored operated calcium entry, osteoblast differentiation

Introduction

In humans and rodents there is bone loss with aging [1,2]. In a previous study in humans, we found strong evidence of severe secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly patients with hip fractures [3], which is an established cause of osteoporosis [4]. Cellular senescence has recently been strongly implicated to be important for the age-related bone loss [5,6]. The majority of bone formed in adults is preceded by bone resorption during bone remodeling [7]. It follows that age-related bone loss is largely due to an impaired coupled bone formation.

This study sought to apply a mouse model of bone repletion in young, middle-aged, and aged mice to gain more information on the cause of impaired coupled bone formation in the aging mouse. We chose Balb/cBy (Balb) inbred mice for this study, because we were able to obtain 21 to 25 months-old Balb mice from the National Institute of Aging. In normal bone remodeling, microscopic remodeling sites are asynchronous throughout the skeleton. In contrast, the calcium-deficient diet, which is the first phase of our bone repletion model, converts the majority of the bone surfaces on endosteum and on trabecular bone to osteoclastic resorption sites. During the second phase when the diet is replenished with sufficient calcium, the endosteal and trabecular bone surfaces are almost occupied by osteoblasts to form bone. Accordingly, bone formation still follows (or is coupled to) bone resorption as in normal bone remodeling [8]. The difference for normal remodeling and bone alterations in dietary calcium depletion is that elevated PTH is responsible for the increase in osteoclastic bone resorption in calcium depletion. In any case, this model provides a synchronous bone remodeling throughout the endosteal trabecular region, allowing separate bone measurements of each phase of the bone remodeling process.

The unique finding from our past studies of bone depletion/repletion in younger animals was that during the process of accelerated bone resorption, all of the cells involved in the subsequent phase of bone formation were formed during the phase of bone resorption that most likely reflects normal bone remodeling [9]. Accordingly, there is a large accumulation of osteogenic cells in the process of differentiation during the bone resorption process, whereas BrdU incorporation studies indicated that no osteoblast proliferation was occurring during the bone repletion phase [9].

In the present study, we compared the coupled bone formation response to an increase in bone resorption in aged Balb mice (21–25 months old) with that in young (1 month old) and adult mice using the calcium depletion/repletion model to gain mechanistic information about the cause of impaired coupled bone formation in aged Balb mice. Application of this model to aged Balb mice confirmed that there was increased resorption during the resorption phase of the calcium depletion but showed almost no bone repletion/repair (i.e., coupled bone formation) during the formation phase of the calcium repletion. The dysfunctional bone repletion in aged mice was associated with reduced osteoblastic differentiation despite increased osteoblastic proliferation and decreased osteoblastic cellular senescence in these old animals.

Methods

Animals and diets.

Female Balb mice at 1 (young), 8 (adult), and 21–25 (aged) months of age were used. Young and adult Balb mice (Balb/cByJ; Strain # 001026) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), whereas aged mice were obtained through the National Institute of Aging (NIA). The control calcium-sufficient diet contained 0.6% calcium and 0.4% phosphate (TD. 97191, Envigo, Livermore, CA). The bone depletion (calcium-deficient) diet (TD. 95027, Envigo) contained <0.01% calcium and 0.4% phosphate. The experimental design is shown in Fig. 1A. Briefly, 1 month-old young mice were fed the calcium-deficient diet (i.e., bone depletion phase) for 2 weeks as described before [9,10] and then changed to the control calcium-sufficient diet for 16 days for bone repair (i.e., bone repletion phase). Because bone resorption, determined by plasma CTx-I level, was unchanged in the 8 months-old adult or in aged mice (21 to 25 months old) in our pilot study, the duration of the calcium depletion phase in the aged mice was extended to 4 weeks. The age-matched control mice of each age group received the control diet for the same duration as the corresponding calcium depletion groups. In a separate experiment, the aged mice were allowed to replete with control diet for additional 4 weeks (for a total of 44 days) to determine whether a longer repletion would lead to complete bone repair. All mice had free access to food and water and were kept under a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. The animal work was performed in the animal facility of Loma Linda University. The animal component of research protocol (ACORP) of this study was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of Loma Linda University and also by the Animal Care and Use Review Office of the US Department of Army.

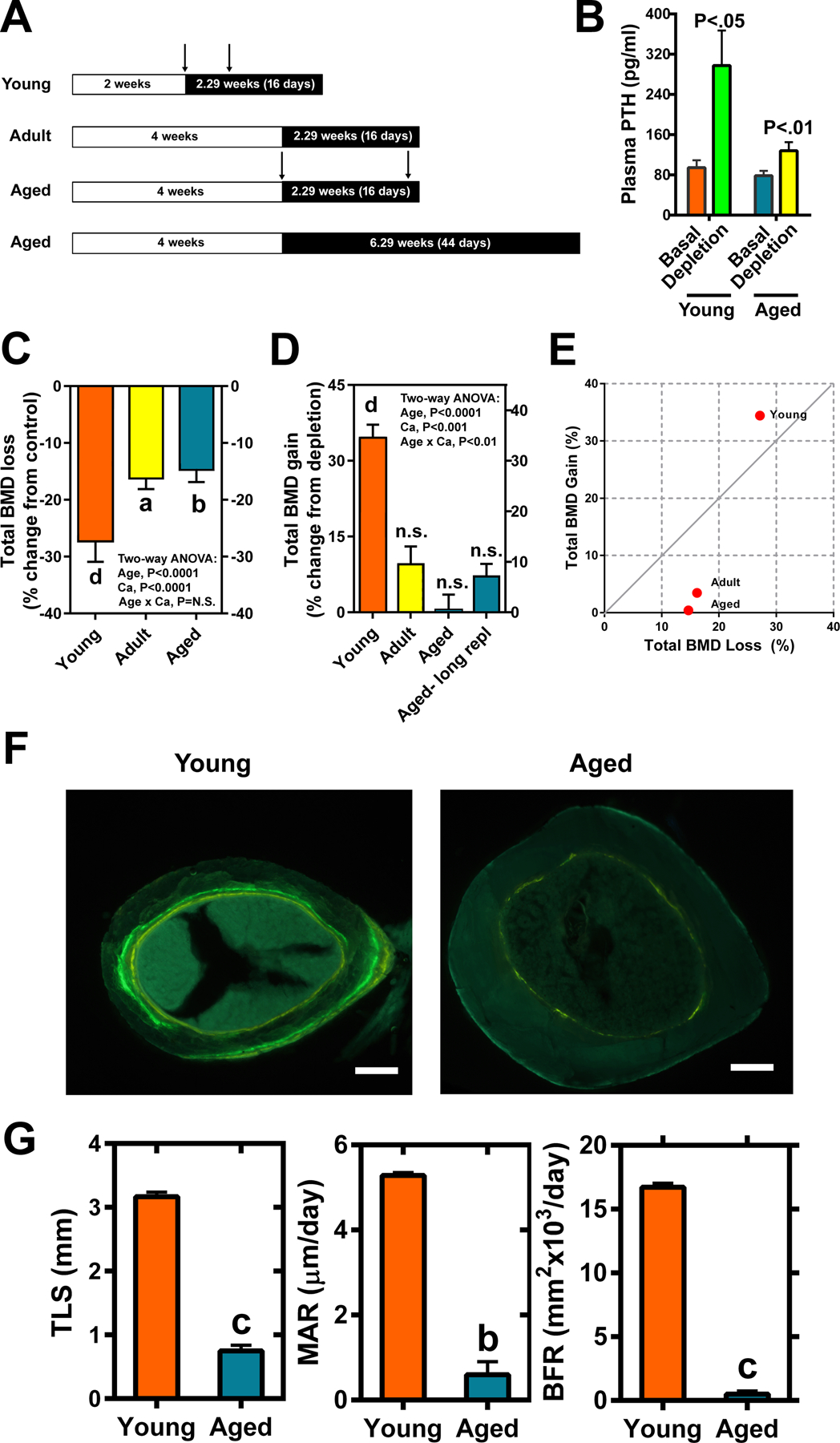

Figure 1. Comparison of bone loss and gain in young, adult, or aged Balb mice (n=6–8) after the dietary calcium depletion and repletion challenge, respectively.

A: Study design. B: Plasma PTH levels in young and aged mice after 2 and 4 weeks of calcium depletion, respectively. In C&D: total BMD was determined by pQCT in the secondary spongiosa of the femurs. C: The relative bone loss after the dietary calcium depletion period was calculated as relative percent change in total BMD from the control group. D: The relative bone gain after the bone repletion period was calculated as relative percent change in total BMD from the depletion group. For the long repletion group (long repl), the aged mice were subjected to calcium sufficient diet for 6.29 weeks (44 days), and calculation of relative percent change in total BMD was calculated in the same manner as for the regular repletion group. E: The plot of bone gain against bone loss in the three age groups of Balb mice using the corresponding mean value. The line is indicative of normal perfect remodeling (e.g., gain/loss =1). F: A representative microphotograph of cross section at the mid-point of the femurs with two tetracycline labels after 2.29 weeks (16 days) of bone repletion. The inter-labeling time was 6 and 13 days for young and aged mice, respectively. G: The calculated histomorphometry parameters of bone formation in the aged mice (Azure bars) versus young mice (Orange bars). TLS=total labeled surface; MAR=mineral apposition rate; BFR=bone formation rate. Scale bars = 50 μm. Significance is determined two-tailed Student’s t-test. aP<.05; bP<.01; cP<.001; dP<.0001 vs. corresponding controls, baselines, or the young group; n.s. = not significant (P>.05).

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) bone mass analysis.

Femurs after dissection were fixed in 10% formalin for two days and were stored in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C until analyses. The length of each femur was measured with a digital caliper. pQCT measurements of total and cortical bone densities were performed with the STRATEC XCT 960M (Norland Medical Systems, Ft. Akinson, WI) and analyzed with the version 6.00 software program provided by the manufacturer as described previously [9,10]. The secondary spongiosa of the metaphysis at the distance of 25% of bone length from distal end of the femur was scanned and analyzed. A density threshold setting of 630 mg/cm2 with the voxel size of 70 μm was used to determine cortical bone compartment.

Bone histology and histomorphometry.

Static and dynamic bone histomorphometry of femurs and histologic features were determined as previously described [11]. Briefly, femoral length was determined using a digital caliper. The midpoint was marked, and bone was then embedded in methyl methacrylate (MMA). The cross-section of the mid-point was dissected using a low-speed diamond saw (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL), and the longitudinal sections were collected using a Leica microtome. Two tetracyclines (i.e., calcein and demeclocycline) were injected at the first and seventh days of repletion, respectively, for young mice, whereas at the first and fourteen days of repletion, respectively, for aged mice due to their well-known low basal bone formation rate. Bone samples were collected after 16 days of repletion. Dynamic histomorphometric parameters were obtained by measuring the length of labels and distance of double labels [11]. TLS (total labeled surface), MAR (mineral apposition rate) and BFR (bone formation rate) were calculated as previously described (11). Trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) parameter was measured at the primary spongiosa of the metaphysis, because there was no trabecular bone in the secondary spongiosa of aged bone. All histomorphometry measurements were performed with the OsteoMeasure system.

Osteoblastic cell cultures.

Both femurs and tibiae were used for osteoblast isolation. After removal of muscle, connective tissues, and marrow cells, bone shells were rinsed thoroughly, digested with 2 mg/ml of crude type I collagenase for 75 minutes at 37°C on a rotating platform at 200 rpm. The released cells were collected and expanded in α-MEM (which has basal calcium level of 1.8 mM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For measurement of expression levels of genes associated with osteoblastic differentiation and senescence, osteoblasts were plated in 12-well plate at a density of 5 ×104 per well in α-MEM containing 2%FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 50 μg/ml of ascorbic acid (differentiation medium) for 6 days with medium change in day 4. For measurement of expression level of genes responsible for calcium entry and cMyc, osteoblasts were cultured in basal α-MEM medium containing 1% FBS for 24 hours.

In vitro osteoblastic cell proliferation assay.

Cell proliferation was determined as follows. A total of 5,000 cells per well was seeded into a 96-well plate overnight. Cells were cultured in α-MEM containing 1% FBS with or without 2 mM of additional calcium (i.e., a total of 3.8 mM medium calcium). Cells were then exposed to 10 μM of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) during the final 12–16 hrs of cultures. The relative level of BrdU incorporation was determined with a commercial ELISA kit (Abcam, Boston, MA) according to instruction provided by the vendor.

ALP specific activity assay.

Primary osteoblasts were plated into a 24 well plate with a density of 2×104 per well and cultured in the same differentiation medium for 6 days. Cell layers were rinsed once with PBS and extracted with 0.1% Triton X-100 (in water). Protein was determined by the BCA protein assay by measuring the absorbance at 562 nm. ALP activity was detected with a spectrophotometric assay. Briefly, aliquots of cell lysate of osteoblasts were incubated with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.3) and MgCl2 up to several hrs at room temperature. The absorbance of the product (p-nitrophenol) was measured at 405 nm, and the ALP specific activity was calculated by dividing the change in absorbance at 405 nm from the baseline with the cellular protein content (in μg).

Senescence-associated (SA) β-gal enzymatic activity staining.

Briefly, the femur, after fixation with Zamboni’s fixative for 12 hours at 4°C, was embedded in an embedding medium (SECTION-LAB, Co., Ltd., Hiroshima, Japan). Frozen thin sections (3-mm thick) were prepared with a Leica cryostat and mounted onto a plastic film (Cryofilm type IIC, SECTION-LAB). The frozen sections were stored in 100% ethanol at −20°C until SA-β-gal activity staining. To visualize SA-β-gal activity positive cells, the bone sections were incubated in the staining solution (5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mg/ml X-gal Substrate in 40 mM citrate/sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6) overnight at 37°C [12]. After rinsing, the sections were counterstained with 0.1% nuclear fast red for 1 min.

Immunostaining for p21Cip1/Waf1 (P21) and Ki67.

Paraffin-embedded bone sections were baked for 1 hour to enhance attachment, and paraffin wax was removed through 3 changes of xylene. After rehydration, bone specimen was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 20 min at room temperature and heated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 7 min. After 30 min of normal serum blocking, specimens were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse P21 antibody (Abcam) or rabbit anti-mouse Ki67 antibody (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA) at 4°C overnight. The HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Bio-Rad) and DAB/H2O2 (Abcam) were applied to visualize positive cells. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The cell count was performed under a bright-field Olympus BX53 microscope along with the OsteoMeasure™ system (SciMeasure).

Dual immunofluorescent staining for co-localization of stim1 and orai1.

Isolated osteoblasts were plated in a 24 well plate at a density of 1×104/cm2 and incubated with 10%FBS/αMEM for 24 hours. Upon assay, cells were treated with 150 nM of thapsigargin (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.) for 5 minutes at RT to deplete ER calcium stores, and immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. After several rinses with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes and blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 minutes. Cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-stim1 antibody (MyBioSource; 1:100 dilution) for overnight at 4°C followed with the secondary antibody DyLight 488 anti-rabbit IgG conjugate (Vector Labs, 1:300 dilution) for 1 hour at RT. After several rinses with 1X PBST containing 0.05% Tween 20, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-orai1 antibody (Alomone Labs, 1:66 dilution) at 4°C overnight followed with the secondary antibody Cy3-anti-rabbit IgG conjugate (Millipore, 1:100 dilution). Fluorescence was visualized under a ZEISS fluorescence microscope (Axio Observer) equipped with the ZEN 3.0 (blue edition) software. Auto-exposure was selected for all selected images. Cell number was counted with the Image J software program.

RT-qPCR for gene expression analysis.

For bone samples, tibiae (including bone marrow) were pulverized using pre-chilled mortars/pestles with liquid nitrogen. Qiazol Lysis Reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX) and chloroform were used to isolate total RNA, which was further purified with a RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). For cell samples, total RNA was isolated from cultured osteoblasts. cDNA derived from RNA of tibia or osteoblast cultures was generated by reverse transcription using the GenScript M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). The relative level of each gene-of-interest (normalized against the house-keeping gene, β-actin) was determined by the Cycle threshold (ΔCt) method using a SyBr Green-based PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) or Promega SyBr Green Master mix in an ABI 7500 Fast cycler (Applied Biosystems) or a CFX96 Real-Time System (Biorad). The primer sets of the test genes are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Intracellular calcium level measurement.

To determine intracellular calcium levels, 1.76 ×105 osteoblasts (approximately 90% confluence) from young and aged mice were carefully loaded onto a coverslip (22 mm × 22 mm) one day before assay. Upon assay, cells were first loaded with 2 μM of fluo-4 AM (ThermoFisher, Los Angeles, CA), a calcium indicator, for 15 min at room temperature. After rinsing off extra dye with physiological saline solution (PSS), the coverslip with cells was placed onto a chamber slide which was connected to three test solutions (e.g., PSS, calcium-free PSS and Ionomycin-containing calcium-free PSS), via tubing. Zeiss 710 NLO laser scanning confocal imaging workstation and an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer) were used to collect fluorescent spikes. The pinhole was adjusted to provide an imaging depth of 5.4 μm. Recordings were collected using an immersion 63X W-Plan Apochromat, 1.2 numerical aperture objective. Regions of interest was automatically generated using the LC Pro plug-in for the Image J software. Upon fluo-4 AM binding to cytosolic calcium, the emitted light was collected using a photomultiplier tube with a band-limited spectral grating of range 493 to 622 nm at a frequency of 1.28 Hz. The peak height from each spike was automatically generated and analyzed.

Statistical analysis.

Results were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance of differences between only two test groups was determined with Student’s two-tailed t test. For more than two test groups, one-way (for one independent factor) or two-way (for two independent factors) Analysis of Variances (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post-hoc test was used to determine statistical significance using GraphPad Prism6 software (San Diego, CA). Two-tailed, paired t-test was used to determine statistical significance of differences in intracellular calcium levels over time.

Results

Bone density, bone formation, and bone repletion in Balb mice as a function of age.

In agreement with the literature [13], basal total bone mineral density (BMD) of aged Balb mice was greater than that of young mice but not that of adult mice (Suppl Fig. S1A), apparently due to thicker cortical bone (Suppl Fig. S1B). Conversely, basal trabecular bone volume was much less in aged mice than in younger mice (Suppl Fig. S1C). We next tested the ability of aged mice to replete bone mass after four weeks of calcium-deficient diet. The study design of dietary calcium depletion/repletion is shown schematically in Fig. 1A. The 4 weeks of dietary calcium depletion substantially increased serum PTH (Fig. 1B) in both young and aged mice, indicating that aged mice also responded to dietary calcium deprivation with development of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Substantial amounts of total (Fig. 1C) and cortical (Suppl Fig. S2A) bone mineral densities (BMD) and trabecular bone volume (Suppl Fig. S2C) were lost in all three test age groups of mice during the calcium depletion phase. Intriguingly, bone repletion, reflected by increases in total BMD (Fig. 1D), cortical BMD (Suppl Fig. S2B) and trabecular bone volume (Tb.BV/TV) (Suppl Fig. S2D), is impaired in adult and aged Balb mice after 16 days of dietary calcium repletion. To test the possibility that a longer repletion time may be required for full bone repletion to occur in the older mice, the aged animals were fed the calcium-sufficient diet for an additional 4 weeks (i.e., a total of 44 days). Upon the extended calcium repletion period, aged animals increased total BMD (Fig. 2D), cortical BMD (Suppl Fig. S2B) and Tb.BV/TV (Suppl Fig. S2D) by 7%, 4%, and ~50%, respectively, but none of these increases reached a statistically significant level due to large variations. To properly assess the efficiency of bone repletion, we normalized the amount of bone gained against the amount of bone loss to calcium depletion. The normal bone remodeling with perfect bone repletion is defined as bone gain/bone loss ratio as 1 (indicated by the line in Fig. 1E). Accordingly, this ratio in young mice was above 1, which exceeds normal remodeling with “overfill”, while that in adult mice was <1 (i.e., below normal remodeling with “underfill”). Conversely, the bone gain/bone loss ratio in aged mice was approaching 0, indicating that there was virtually no gain in the ratio (i.e., no bone repletion) in aged mice. Bone histomorphometry analysis of cortical bone also indicated an impaired bone forming ability on endosteal cortex in aged mice (Fig. 1F & G).

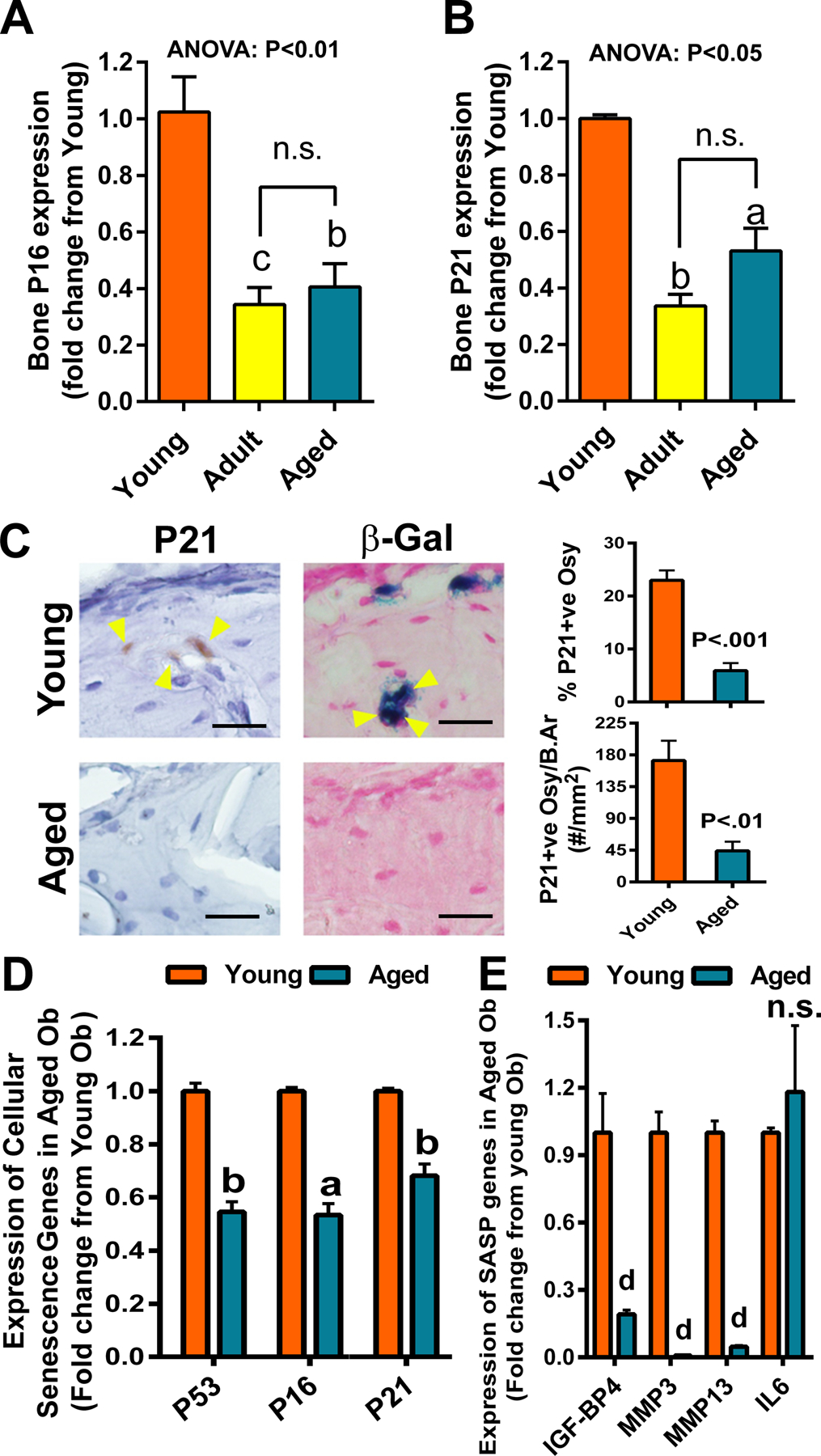

Figure 2. Comparison of basal expression of cellular senescence marker genes among the three test age groups.

Gene expression was determined by RT-qPCR with the Sybr-green method. Expression level of P16 (A) and P21 (B) mRNA in bone was each normalized against β-actin mRNA and compared among the three test age groups (n=4). aP<.05; bP<.01; cP<.001 vs. Young by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. n.s.=not significant (P>.05) between the adult and the aged group of mice. (C) Immuno- and histochemical staining of P21 and SA-β-gal activity in osteocytes (indicated by yellow arrowheads) of Young (top panels) and Aged (bottom panels) mice. Scale bars = 50 μm. P21 positive osteocytes (Osy) in the cortex were identified by specific anti-P21 antibody immunostaining and counted with the OsteoMeasure™ system. The relative % of P21 positive osteocytes and the number of P21 positive osteocytes per bone area were reported. SA-β-gal activity in osteocytes on a frozen bone section was shown in bluish color after overnight incubation with substrate solution at 37°C followed by nuclear fast red counterstaining. Expression of cellular senescence marker genes (D) and selective senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors (E) in osteoblasts (n=4), after culturing for 6 days in α-MEM supplemented with 2%FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 50 μg/ml of ascorbic acid, was each determined by RT-qPCR. aP<.05; bP<.01; dP<.0001 vs. young osteoblasts by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Osteoblastic cellular senescence.

In both humans and mice, bone loss attending the aging process appears to be caused by senescence of bone cells and can be partially reversed by senolytic drugs [14]. Typically, the presence of cellular senescence is reflected by increases in gene expression of p16INK4a (P16) and p21Cip1/Waf1 (P21) [15]. Therefore, we compared the relative expression level of P16 and P21 in long bones of each of the 3 test age groups of mice. Surprisingly, the expression level of P16 and P21 genes in aged animals (21 to 25 months of age) each was not different from 8-month-old adult mice but significantly less than that of P16 and P21 in bones of one-month-old young mice (Fig. 2A and B). Because whole bone that was used in this analysis contained contaminating marrow cells, which could have influenced the results, we examined bone sections for immunohistochemical staining of P21 in osteocytes (which are the predominant cell type exhibiting senescence on bone) [5,16]. There was substantially less P21-immunostained osteocytes (in terms of relative percentage or per bone area) in bones of older mice compared to that of young bones (Fig. 2C). The senescence-associated β-gal (SA-β-gal) activity (at pH 6.0) preferentially marks cells undergoing senescence [17]. Our histochemical staining for SA-β-gal activity at pH 6.0 showed similar results to those of immunohistochemical staining of P21 (Fig. 2C). We next compared the relative expression levels of P16, P21, as well as P53 [which is an upstream regulatory gene of senescence and of P16 and P21 [18]] (Fig. 2D) and SASP genes (Fig. 2E) in primary osteoblasts isolated from the young with those in primary osteoblasts isolated from aged mice. We confirmed that the relative expression levels of P16, P21, and P53 as well as the test SASP genes (with exception of IL6) in aged osteoblasts were indeed substantially lowered than those in young osteoblasts. Taken together, these findings indicate the lack of an increase in cellular senescence in bones of aged Balb mice.

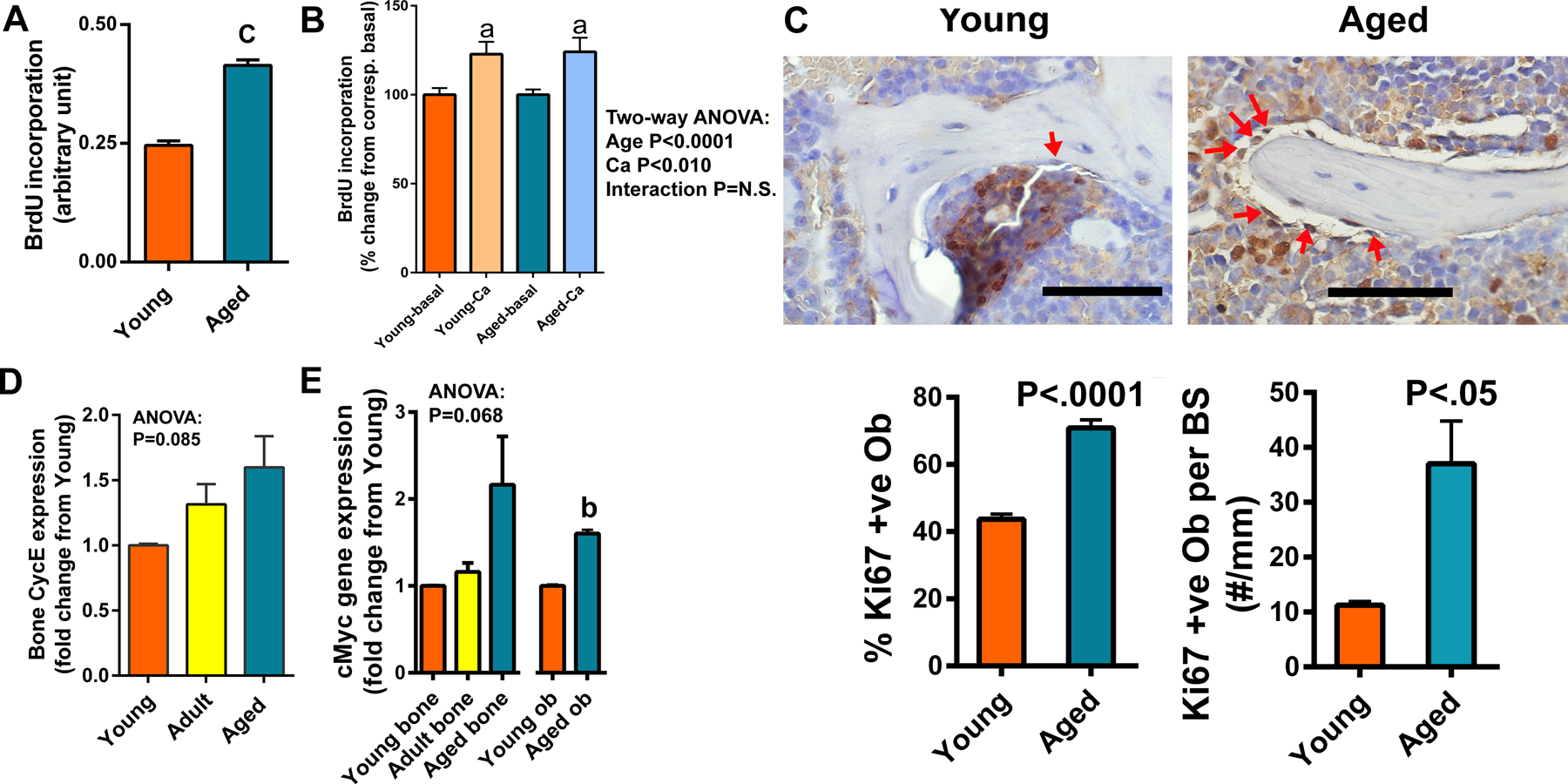

Osteogenic cell proliferation.

We also compared osteoblastic proliferation by measuring BrdU incorporation in osteoblastic cells isolated from bone of young mice with that in osteoblastic cells isolated from bones of aged mice, since reduced P16 and P21 expression are often associated with high proliferation rate. Consistent with the reduced P16 and P21 expression levels in aged bone cells, there was a marked increase in basal BrdU incorporation in bone cells of aged mice compared to that in young bone cells (Fig. 3A). As an in vitro surrogate of calcium repletion, we also compared the proliferative response of aged osteoblasts to an increased medium calcium concentration by adding 2 mM calcium (a total of 3.8 mM) with that of young osteoblasts. Aged osteoblasts responded similarly to the added medium calcium as young osteoblasts (Fig. 3B). The higher basal proliferation rate of aged bone cells was further implicated by an increased Ki67 immunostaining in bone surface osteoblasts of aged mice (Fig. 3C) and supported by an aging-associated elevated CycE expression in bone of aged mice, albeit it did not reach statistically significant level based on one-way ANOVA (Fig. 3D). One of the major determinants of increased cell proliferation in conjunction with low expression of P16 and P21 is cMyc [19]. cMyc overexpression is associated with an increase in proliferation [20]. Measurements of cMyc gene expression level indicated that the cMyc gene expression level in the whole bone and in primary osteoblasts of aged Balb mice was each higher than that in bone and primary osteoblasts of younger mice (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. Comparison of basal and calcium-stimulated BrdU incorporation, Ki67 immuno-positive osteoblasts, CycE expression, and cMyc gene expression among the three age groups.

A: The relative basal proliferating activity of osteoblasts derived from bones of young versus aged mice, determined by measuring BrdU incorporation into cultured cells using a commercial ELISA kit (Abcam). Each assay had 6 replicates and there were 2 repeats of the assay. B: Comparison of the stimulatory effects of added 2 mM calcium (Ca) in culture medium on BrdU incorporation of primary osteoblasts isolated from young and aged Balb mice (n=6). C: The proliferative cells, are determined by Ki67 immunostaining in a representative young and an aged bone. Yellow arrows indicate Ki67 positive osteoblasts, which is stained in brownish color. Negative cells are counter-stained in bluish color by hematoxylin. Scale bars = 100 μm. The Ki67 positive osteoblasts on the bone forming surface of the trabeculae in the metaphysis were counted with the Osteo-Measure System. D&E: Cyclin E (CycE) (D) mRNA level in tibial bone extract (n=4) and cMyc (E) mRNA level in tibial bone extract (n=4) and in isolated osteoblastic cell extract (Ob) (n=3), after normalization against β-actin mRNA expression by RT-qPCR. Statistical significance was determined by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test or two-tailed Student’s t test. aP<.05; bP<.01; cP<.001 vs. Young or Basal.

Osteoblastic cell differentiation.

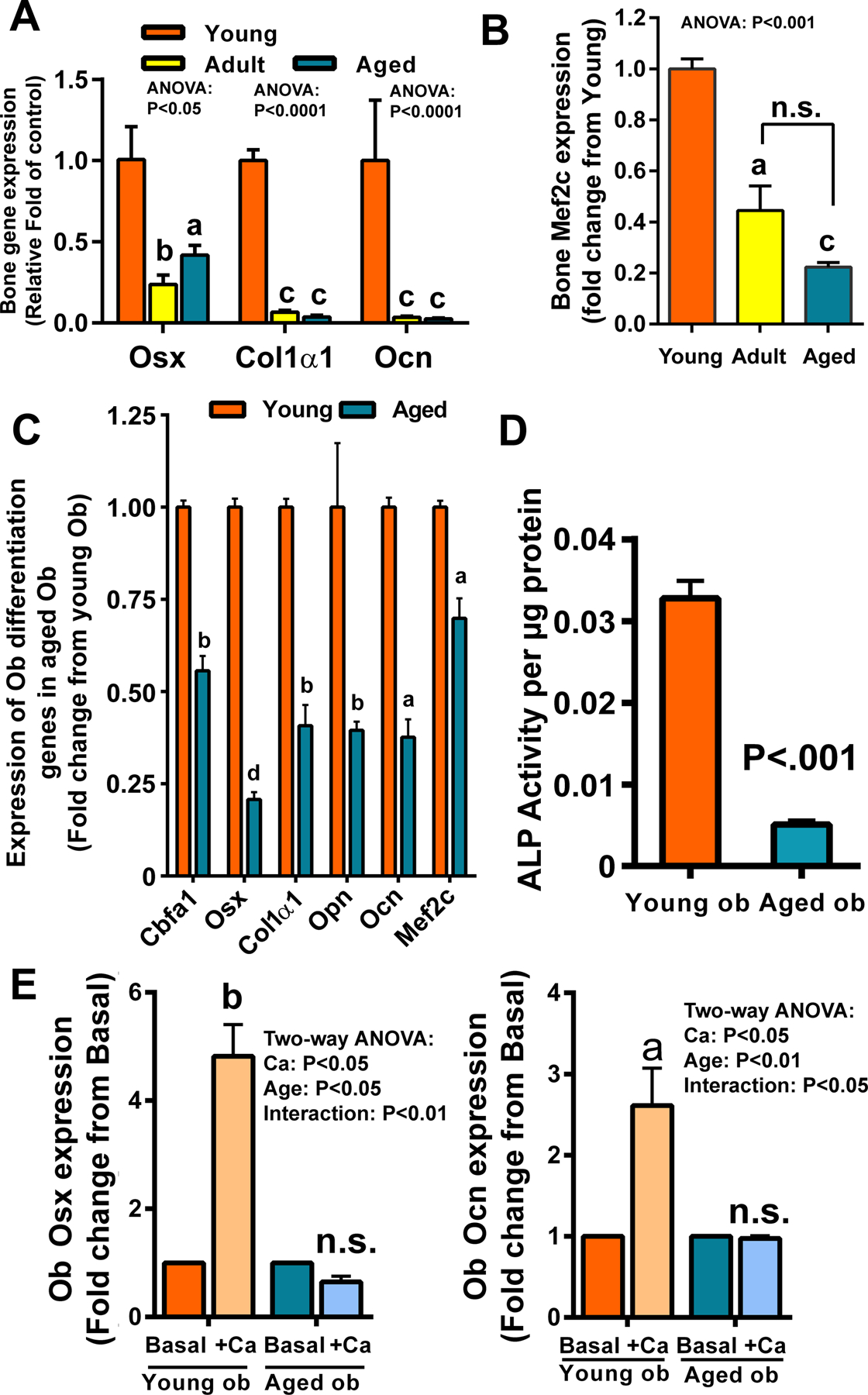

We next compared expression of bone cell differentiation markers in aged bone and osteoblasts with that in young bone and osteoblasts. The basal mRNA levels of three test osteoblastic markers (i.e., Osx, Col1α1, and Ocn) (Fig. 4A) and MEF2c, a transcription factor regulating osteoblastic differentiation [21] (Fig. 4B), were all decreased in the whole bone of older animals compared to those in young animals. The basal expression levels of the various osteoblastic differentiation marker genes (i.e., Cbfa1, Osx, Col1α1, Opn, Ocn, and Mef2c) in primary osteoblasts of aged Balb mice were also decreased compared to those of young osteoblasts (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the premise that aged osteoblasts are less differentiated, basal cellular ALP specific activity in aged osteoblasts were substantially lower than that of young osteoblasts (Fig. 4D). Not only basal osteoblastic differentiation was defective, aged Balb osteoblasts either did not respond or its response was drastically reduced to increased medium calcium on the expression of osteoblastic marker genes, such as Osx and Ocn, when compared to young Balb osteoblasts (Fig. 4E). Therefore, the in vivo basal and the in vitro calcium-stimulated osteoblastic differentiation are impaired in aged Balb osteoprogenitor cells compared to young osteoprogenitors.

Figure 4. Comparison of the expression of genes associated with osteoblastic differentiation (A) and Mef2c (B) among bones of the three test age groups under basal conditions and between osteoblasts isolated from bone of young and aged mice (C, D), and the extracellular calcium-stimulated expression of osteoblastic genes in primary osteoblastic cells isolated from bones of young and aged mice (E).

In A&B, total RNA was extracted from the tibia (n=4). Gene expression was determined by RT-qPCR. The mRNA expression levels (normalized against corresponding β-actin mRNA level) of osterix (Osx), collagen type 1α1 (Col1α1), osteocalcin (Ocn) in (A) and Mef2C in (B) in bones of the three test age groups were compared and reported as relative fold change from the corresponding Young group. In C, osteoblastic cells (Ob) isolated from one-month-old young mice or 25-month-old aged mice. Isolated cells (n=4) were then cultured in the differentiation medium containing 2% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 50 μg/ml of ascorbic acid for 6 days. The expression of genes of interest after normalized against β-actin was determined by RT-qPCR. In D, osteoblasts were cultured in the differentiation medium and change in ALP activity per cellular protein was determined with a spectrophotometric assay at 405 nm. In E, isolated osteoblasts (Ob) were cultured in the α-MEM medium supplemented with (+Ca) or without (basal) 3 mM extra calcium for 24 hrs. The expression of Osx or Ocn, normalized against β-actin mRNA, were determined by RT-qPCR (n=3 per group), and reported as relative fold of each corresponding basal control. Statistical significance was determined by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test (A, B, E) or by two-tailed Student’s t-test (C, D). aP<.05; bP<.01; cP<.001; dP<.0001 vs. Young or Basal. In B, comparison is also made between the adult and aged groups by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Cellular calcium signaling.

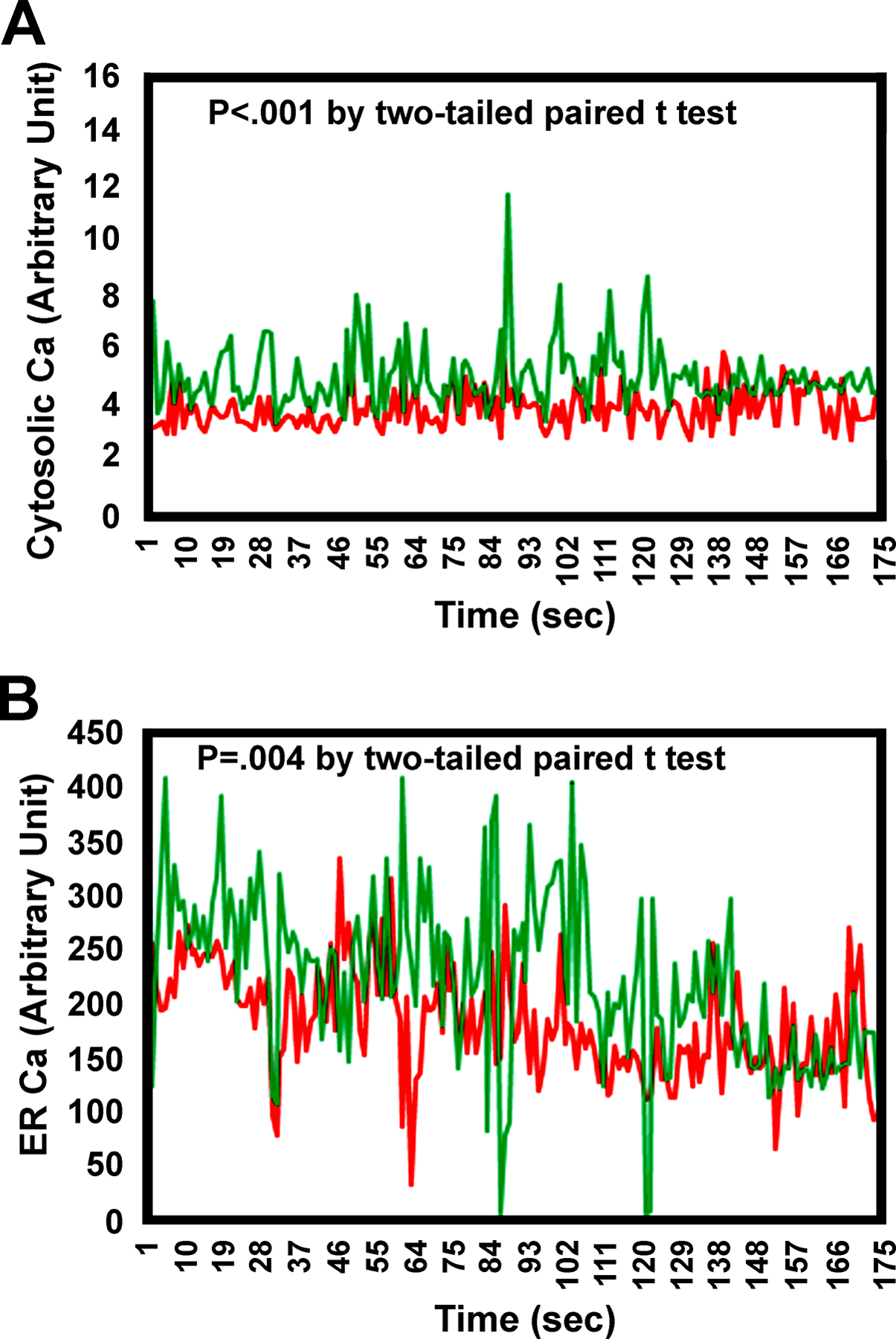

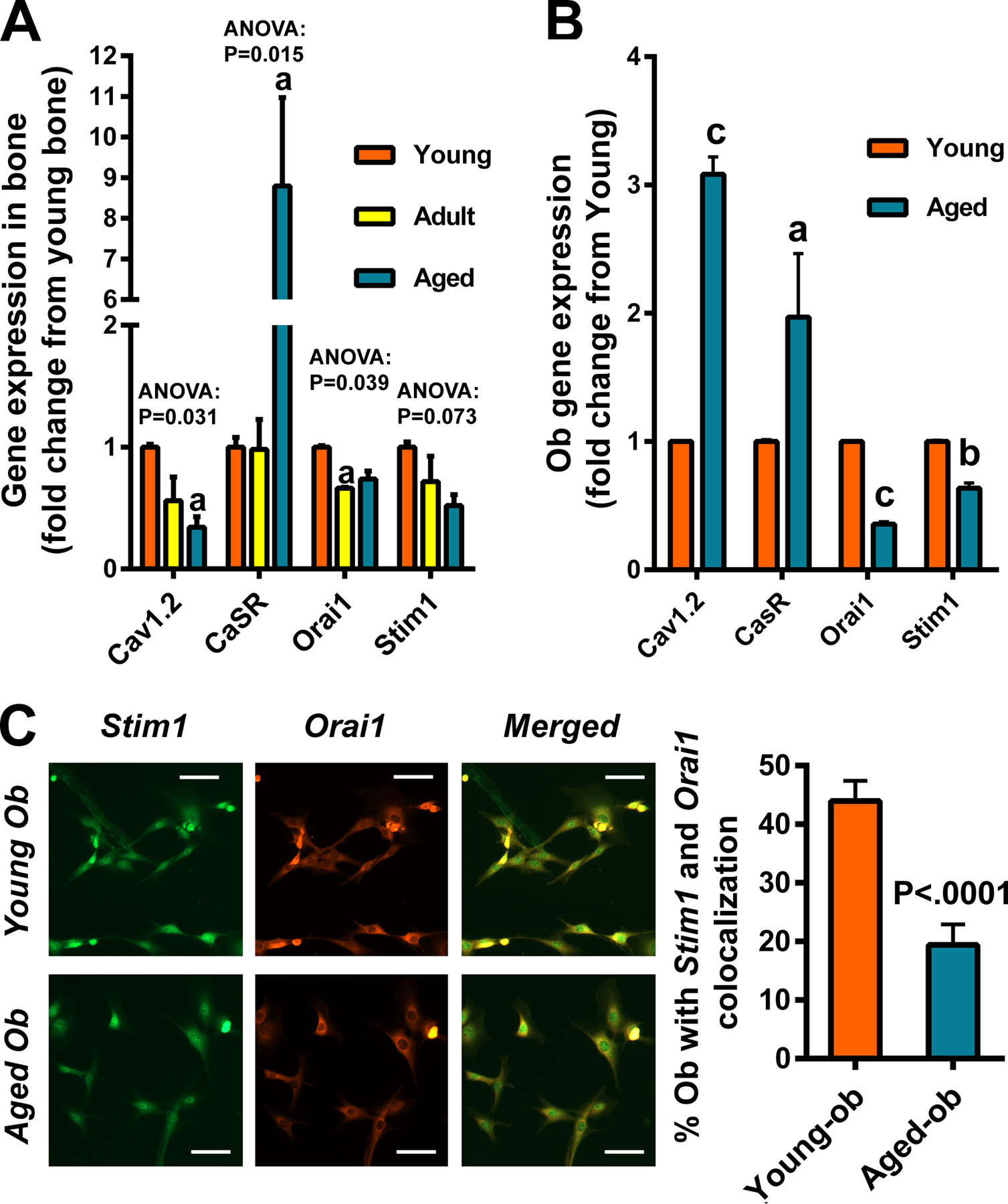

One of the major cellular changes in association with increased expression of cMyc is an increase in cytosolic calcium [22], and the actions of cMyc frequently represent the combined effects of cMyc and the increased cytosolic calcium, which are sometimes acting synergistically [22,23]. Thus, we next measured cytosolic calcium in untreated cells and also cells after treatment with ionomyosin, which depletes ER calcium stores [24], and found that cytosolic calcium (Fig. 5A) and the ER stores of calcium (Fig. 5B) were increased in aged Balb mice. To better understand the increase in cytosolic calcium, we compared expression levels of the calcium sensing receptor (CaSR), Cav1.2 (a L-type calcium channel), Orai1 (a critical component of Stored Operated Ca2+ Entry (SOCE)], and Stim1 (a calcium sensor that conveys the calcium load of ER to SOCE at the plasma membrane) in the whole bone (Fig. 6A) and in the primary osteoblastic cells (Fig. 6B) isolated from young and aged mice. There were significant increases in the expression of CaSR, but significant decreases in the expression of Orai1 and Stim1 in both aged bone and aged osteoblasts. However, the expression level of Cav1.2 in the whole bone was reduced in aged mice but it was significantly elevated in aged osteoblasts. It has been known that Stim1 aggregation is required for the clustering of Orai1 and for co-localization, which is needed for SOCE activation. Thus, we also compared the relative percentage of osteoblasts with colocalization (surrogate measurement of aggregation) of Stim1 and Orai1 in primary aged osteoblasts with that in primary young osteoblasts in culture upon thapsigargin treatment to deplete ER calcium store. We found that there was >50% reduction in the percentage of osteoblasts with Stim1 and Orai1 colocalization (aggregation) in aged cells compared to that in young cells (Fig. 6C), suggesting a reduction in SOCE activation in aged osteoblasts.

Figure 5. Comparison of time-dependent cytosolic and ER calcium levels in young versus aged osteoblasts.

Osteoblasts were isolated from long bones of young and aged mice. Cytosolic and ER calcium levels were determined using a calcium indicator, fluo-4 AM; and fluorescence signal upon binding to calcium was captured by a Zeiss confocal microscopy system. (A) Comparison of cytosolic calcium levels between young and aged osteoblasts over the indicated time point. (B) Comparison of ER calcium levels at the presence of ionomycin to induce the release of calcium from the ER into cytoplasm over the indicated period. Red = Young osteoblasts; Green = Aged osteoblasts. Each data point at the peak height from each age group over this time course was analyzed by two-tailed paired Student’s t-test.

Figure 6. Comparison of basal mRNA expression levels of genes responsible for calcium cellular entry in bone (A) or in isolated primary osteoblasts (B, C).

In A, total RNA was extracted from long bones of three age groups and reversely transcribed into cDNA. In B, osteoblasts (Ob) were isolated from long bones of young and aged mice (n=3). In both A&B, the mRNA expression of each test calcium entry gene, i.e., L-type calcium channel Cav1.2, calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), Stim1, and Orai1 (each normalized against β-actin mRNA) was determined by RT-qPCR. Statistical significance is determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test or Student’s two-tailed t-test. aP<.05; bP<.01; cP<.001 compared to the young group. In C, osteoblasts were treated with 150 nM of thapsigargin for 5 minutes to induce the depletion of ER calcium stores. Sequential dual immunostaining was performed. Stim1 was first detected using anti-stim1 antibody and DyLight488-anti-rabbit IgG conjugate, which was followed by detection of orai 1 using anti-orai1 antibody and Cy3-anti-rabbit IgG conjugate. Fluorescence signals were detected with a ZEISS fluorescence microscope equipped with the ZEN3.0 (blue edition) software. Stim1 positive cells are shown in greenish fluorescence. Orai1 positive cells are shown in orange-red fluorescence. Cells with co-localization of Stim1 and orai1 are shown as yellow fluorescence. Scale bar = 100 μm. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Discussion

The present study was undertaken to gain mechanistic information about the bone repair mechanism in aged Balb mouse. We chose the bone repletion system as a bone repair model for investigation, because bone repletion is a physiological form of bone repair mechanism to repair/regenerate the loss in trabecular bone mass and architecture during the previous period of calcium deficiency. In this study, we found that the bone repletion process in younger Balb mice was highly effective as expected, but the bone repletion process in aged mice is impaired. Accordingly, there was virtually no regain of BMD in aged mice after 16 days of calcium repletion, and it showed only ~7% (but statistically not significant) improvement in total BMD even after the repletion period was extended by an additional 4 weeks in aged mice. Therefore, there appears to be an aging-related decline in the bone repletion response in Balb inbred strain of mice and the bone repletion process in aged mice is defective. However, it is not surprising that the bone repletion response in aged mice is defective, given the fact that age-related bone loss has been established to be associated with an impaired coupled bone formation in aged animals.

The mechanistic cause for the defective bone repletion in aged mice is multifaceted and appears to involve multiple extrinsic and intrinsic factors and pathways [25]. However, three salient discoveries of this study may offer important hints. First, although cellular senescence of bone cells has been implicated to be a key factor of age-related bone loss and cellular senescence could impair bone formation [5,6], there is the surprising lack of evidence for an increase in bone cell senescence in aged Balb bone, as reflected by the reduced expression of marker genes of cell senescence, i.e., p16INK4a (P16) and p21Cip/Waf1 (P21) in bone and osteoblasts. These two cellular senescence markers were decreased not only in aged animals but also in 8-month-old adult mice. Moreover, the cytochemical staining study, which showed substantial staining for SA-βgal activity and for P21 in osteocytes of young bones but not in osteocytes of bones of aged animals, along with the drastic reduction in expression levels of SASP genes in aged osteoblasts further supports the premise that aged Balb mice had a reduced rather than an increased bone cell senescence. While the mechanism for this lack of an increased bone cell senescence in aged Balb mice is undetermined, our findings clearly indicate that the poor bone repletion response in aged Balb mice was not due to an increase in bone cell senescence as proposed by others [5,6,14].

Second, it is intriguing that basal osteoblastic proliferation (measured by BrdU incorporation) of the osteoblast-rich fraction of isolated bone cells from aged Balb mice was significantly higher than that of osteoblastic cells of young Balb mice. Moreover, in situ immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 also showed large numbers of Ki67-expressing cells in the marrow space and in osteoblastic cells lining the trabecular bone surfaces in aged mice in vivo compared to those in bones of 1-month-old young mice. Ki67 accumulation occurs only during S, G2, and M phases, and is degraded continuously in G1 and G0 phases. Accordingly, unlike BrdU incorporation, the expression level of Ki67 during G0 and G1 in individual cells is highly heterogeneous, which can lead to poor analytical reproducibility with Ki67 staining (a proliferation marker protein) [26]. Nevertheless, like BrdU incorporation, Ki67 expression has generally been considered as a reliable proliferation marker protein. Accordingly, the greater BrdU incorporation along with larger Ki67 expression in aged osteoblastic cells indicate that aged Balb mice had higher basal osteoblast proliferation, which was not an in vitro artifact. The greater basal proliferation of bone cells in aged mice was unexpected, because histomorphometric bone formation parameters of aged Balb were drastically lower than those of young mice, and because the 1-month-old young mice were still growing and basal osteogenic cell proliferation rate in young animals is expected to be substantially higher than that of aged animals. We should note that our findings of a greater basal proliferation in aged Balb osteoblastic cells are in agreement with those of a previous report showing that osteoblast cultures from aged Balb mice had a 3-fold higher basal proliferation rate than osteoblasts of younger mice [27]. However, there is also a significant difference between our study and this previous study [27], which showed that while young osteoblasts responded robustly to mitogens in serum, the osteoblasts of aged Balb mice did not respond to mitogens in serum with an increase in cell proliferation. In contrast, we found that aged Balb osteoblasts responded equally well to the proliferative stimuli of an increased medium calcium as did osteoblasts isolated from young Balb mice. The reason for the apparent discrepancy in the proliferative response to mitogens between the two studies is unclear, but our findings suggest strongly that the impaired bone repletion in aged Balb mice is not due to an impaired bone cell proliferation or to an inability of aged osteoprogenitors to respond to an increase in extracellular calcium-level. The latter conclusion is relevant and important since both the increased bone resorption in calcium deficiency and calcium repletion itself could (at least transiently) increase local calcium concentration in the bone moiety.

The foregoing results present an apparent conflicting situation in which there was a high bone cell proliferation rate in vivo and in vitro but a decreased bone formation rate in vivo along with poor bone repletion response in the aged mice. One possible explanation is a defective osteoblastic differentiation capability in the aged osteoblasts. Thus, the third salient discovery is the finding of gene expression evidence for an impaired osteoblastic differentiation in aged Balb mice in vivo and in vitro. Accordingly, whole bone and isolated primary osteoblasts of aged Balb mice showed substantially reduced expression of osteoblastic genes, including osterix, type 1 collagen, osteocalcin, Cbfa1, osteopontin, and MEF2c than bone and osteoblasts of young mice. Moreover, elevated calcium concentration in culture medium greatly increased the expression level of osteoblastic genes (such as osterix and osteocalcin) in young Balb osteoblasts, but the increased medium calcium had little to no stimulatory effects on the expression of these osteoblastic genes in aged Balb osteoblasts. These gene expression data, together, would indicate that basal osteoblastic differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells in bones of aged Balb mice is defective and that the stimulatory response to an increase in extracellular calcium on osteoblastic differentiation was also impaired in aged Balb bone cells. This finding is noteworthy, since we have previous shown that all of the osteoprogenitor cells involved in the subsequent phase of bone formation during repletion were formed during the depletion phase [9]. Accordingly, aged osteoblastic cells had enhanced proliferative activity compared to cells of young mice and showed similar proliferative response to increased calcium as young cells in vitro. It is likely that substantial numbers of osteoprogenitor cells were already formed during the depletion period in both aged and younger mice, but these osteoprogenitor cells in only younger mice but not in aged mice would be able to be differentiated into functional active osteoblasts to carry out the bone repletion process. Our findings of the decreased tetracycline labeling in aged mice compared to young mice in vivo, despite the increased proliferation of osteoblastic cells in bones of aged mice are consistent with this interesting concept. Consequently, based on the foregoing findings, we conclude that an impaired osteoblastic differentiation, and not an increased cellular senescence or an impaired proliferation of osteoprogenitors, is responsible for the poor bone repletion in aged Balb mice.

One transcription factor that has the capacity to increase cell proliferation but impairs cell differentiation is cMyc [20,28]. Accordingly, cMyc is known to increase cyclin E-dependent cell proliferation [29]. Transgenic overexpression of cMyc in mesenchymal stem cells promoted high proliferation rates but attenuated their differentiation capacity [28], suggesting a suppressive role of cMyc in cell differentiation. Our study found increases in gene expression of both cMyc and cyclin E in aged Balb bones in vivo and in aged bone cells in vitro; consistent with the possible involvement of cMyc and cyclin E in the aberrant elevated proliferation of aged Balb bone cells. Upregulation of cMyc is known to downregulate P21 and P16 and prevent cell senescence [19,30], our findings of decreased P16, P21, and SA-βgal in bone cells and bones of aged Balb mice are also consistent with our contention that the lack of increased cellular senescence in aged Balb mouse bones could in part be due to the upregulation of cMyc in aged bone cells. Accordingly, it is conceivable that the unexpected upregulation of cMyc expression in aged bone cells might play a key role in the observed upregulation of osteoblast proliferation, downregulation of osteoblast differentiation, as well as the suppression of cellular senescence in aged Balb mice. However, we should emphasize that a direct regulatory relationship among cMyc upregulation and alterations in osteoblastic differentiation and proliferation in aged Balb bone cells has not been demonstrated and the causal relationship among them is needed to be established with much more direct evidence. In addition, the aging-associated expression profile of cMyc in Balb mice was different from that seen in C57BL/6 mice in that cMyc expression is the highest in newborn C57BL/6 mice and reaches the lowest level at 6 months of age, which then increases with aging [31]. Thus, the possibility that aging-associated cMyc expression profile is mouse strain-dependent cannot be ruled out at this time.

In B lymphocytes, cMyc does not act alone and increases cytosolic calcium concentration are also involved in that cMyc increases the proliferation and differentiation of B lymphocytes through sustained increases in cytosolic calcium [22,23]. In bone cells of aged Balb mice, we observed an increased expression in cMyc that was accompanied by an elevated and appeared to be sustained level of cytosolic calcium along with an increased cell proliferation compared to young bone cells. This finding of elevated levels of cytosolic calcium in bone cells is significant, as both calcium depletion (through an increase in bone resorption) and repletion (through increased calcium concentration in the circulation) could result in substantial increase, at least transiently, local extracellular calcium levels in the bone moiety. Elevated extracellular calcium is a potent stimulator of the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [32]. Accordingly, elevated extracellular calcium increases calcium influx, leading to an increase in cytosolic calcium level, primarily mediated through the various type of voltage-dependent calcium channels (such as L-type calcium channels) to stimulate cell proliferation [33]. It also acts directly to activate the cell surface CaSR and downstream signaling to stimulate cell proliferation [34]. Consistent with this premise, our study found that along with an increase in cell proliferation, there was an increase in aged osteoblasts in the basal expression of L-type calcium channels, such as Cav1.2, and the CaSR. However, it is intriguing that unlike in aged osteoblastic cells, the basal expression of Cav1.2 in whole bone of aged mice was reduced. The reason for the apparent discrepancy in the expression of Cav1.2 in aged bone vs. that in aged osteoblasts is not clear. We should note that the expression level of Cav1.2 in the whole bone represented that in all cell types in the bone, including osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts, marrow stromal cells, and chondrocytes, whereas that in isolated primary osteoblasts represented that Cav1.2 gene expression in osteoblasts, which we believe may be more relevant to the regulation of osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. In any event, the molecular mechanism responsible for the elevated expression of Cav1.2 and CaSR in osteoblasts of aged Balb mice is unclear. Assuming calcium depletion/repletion would result in similar increases in extracellular calcium in bone moiety of young mice as well as aged mice, it follows that there may be an overactive calcium influx due to the increased expression of voltage-dependent calcium channel, such as Cav1.2, which is responsible for the observed elevated cytosolic calcium levels and the higher basal cell proliferation in aged Balb bone cells. We cannot completely rule out the possibility that the calcium influx in aged cells may have been defective such that the increased expression levels of Cav1.2 and/or CaSR are consequence of feedback regulation responses. Because we did not measure calcium efflux in this study, we also cannot rule out the possibility that there may also be an impaired calcium efflux in aged bone cells. Moreover, it is also important to emphasize that an alternative explanation for the increase in cytosolic calcium is aging itself [35,36]. Accordingly, our study does not distinguish between aging or cMyc as the potential cause for the increase in cytosolic calcium.

Excess cytosolic calcium is rapidly transported to and stored in the ER. When the ER store of calcium is depleted, the SOCE is activated, which is a complex sequence of events involving Orai’s on the plasma membrane and Stim’s on the ER membrane [37]. SOCE plays a homeostatic role in providing Ca to refill the ER after calcium has been released and pumped out across the plasma membrane. Accordingly, the ER plays a key regulatory function in controlling intracellular calcium level. We found that aged osteoblasts also had elevated and sustained levels of calcium in the ER. It follows that the elevated ER calcium level is expected to reduce SOCE. Our observations of decreased expression in both Orai1 and Stim1 as well as decreased colocalization of Orai1 and Stim1 in aged osteoblasts are consistent with our concept of reduced SOCE in aged bone cells. Nevertheless, the observations of reduced expression of key component genes, i.e., Orai1 and Stim1, of SOCE, and reduced colocalization of Orai1 and Stim1, despite an elevated ER calcium level in aged osteoblasts is surprising, since generally speaking a higher SOCE would lead to an increase in ER calcium level or vice versa. Consequently, we conclude that the SOCE mechanism in bone cells of aged Balb mice is defective, presumably due to the feedback suppressive action of the sustained elevated levels of calcium in ER. The SOCE mechanism serves a much wider set of signaling functions. In particular, the SOCE mechanism has been shown to upregulate osteoblastic differentiation [38]. Therefore, it is likely that the impaired osteoblastic differentiation seen in aged Balb osteoblastic cells could be the consequence of the defective SOCE mechanism due to the suppressed expression of Orai1 and Stim1. Consistent with this intriguing possibility, it has previously been shown that mice with Orai1 deletion showed bone loss aggravated with aging and impairment in function of their osteoblast lineage cells [39].

In conclusion, we presented evidence for an impaired coupled bone formation in aged Balb mice based on the reduced ability of their bone cells to replace the lost bone mass due to dietary calcium deficiency upon dietary calcium repletion. Additionally, Balb mice showed impaired bone repletion that was attributable to decreased basal and calcium-dependent stimulated osteoblastic differentiation despite an increased basal and calcium-mediated stimulated osteoprogenitor cell proliferation in our model of bone depletion/repletion. These findings may not necessarily reflect the typical effects of aging in other mouse strains. This conclusion is based on our finding of increased cMyc expression in osteogenic cells, perhaps beginning in adulthood. The increase in cMyc was associated with an increase in cytosolic calcium, a change which has been previously reported in other cell types. Increases in cytosolic calcium and cell proliferation are likely associated with an increase in Cav1.2 and CaSR expression in aged osteoblastic cells. In contrast, the defective osteoblastic differentiation is probably associated with an upregulation of cMyc expression and/or the reduction of SOCE activation and Orai1 and Stim1 expression that may be the consequence of the abnormally high ER calcium levels. However, the cause for increased expression of Cav1,2 and CaSR and that for the aberrantly high basal ER calcium level in osteogenic cells from the aged Balb mice remain undetermined. The answers to these key questions would require much additional work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms. Monica Romero for her excellent technical assistance. The work is supported in part by a grant from the Department of Defense, the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) under grant no. W81XWH-12-1-0023 (DJ Baylink and KHW Lau). Imaging was performed in the LLUSM Advanced Imaging and Microscopy Core supported by NSF Grant No. MRI-DBI 0923559 and the Loma Linda University School of Medicine. The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official position, policy or decision of the US Army or the United States government, unless so designated by other documentation. KHW Lau was supported by a Merit Review (IO1 BX002964) and a Research Career Scientist Award (IK6 BX003782) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Loma Linda University and the Animal Care and Use Review Office (ACURO) of US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command of the Department of Defense. In conducting research using animals, the investigators adhered to the Animal Welfare Act Regulations and other Federal statutes relating to animals and experiments involving animals and the principles set forth in the current version of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant DNA Molecules.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement

All authors (Matilda H.-C. Sheng, Kin-Hing William Lau, Charles H. Rundle, Anar Alsunna, Sean M. Wilson, and David J. Baylink) have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Gudmundsdottir SL, Indridason OS, Franzson L, Sigurdsson G (2005) Age-related decline in bone mass measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and quantitative ultrasound in a population-based sample of both sexes: identification of useful ultrasound thresholds for osteoporosis screening. J Clin Densitom 8:80–6 doi: 10.1385/jcd:8:1:080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson VL, Ayers RA, Bateman TA, Simske SJ (2003) Bone development and age-related bone loss in male C57BL/6J mice. Bone 33:387–98 doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00199-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ (1992) Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 327:1637–42 doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkley N, Blank RD, Leslie WD, Lewiecki EM, Eisman JA, Bilezikian JP (2017) Osteoporosis in Crisis: It’s Time to Focus on Fracture. J Bone Miner Res 32:1391–94 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farr JN, Fraser DG, Wang H, Jaehn K, Ogrodnik MB, Weivoda MM, Drake MT, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Kirkland JL, Bonewald LF, Pignolo RJ, Monroe DG, Khosla S (2016) Identification of Senescent Cells in the Bone Microenvironment. J Bone Miner Res 31:1920–29 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr JN, Xu M, Weivoda MM, Monroe DG, Fraser DG, Onken JL, Negley BA, Sfeir JG, Ogrodnik MB, Hachfeld CM, LeBrasseur NK, Drake MT, Pignolo RJ, Pirtskhalava T, Tchkonia T, Oursler MJ, Kirkland JL, Khosla S (2017) Targeting cellular senescence prevents age-related bone loss in mice. Nat Med 23:1072–79 doi: 10.1038/nm.4385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parfitt AM (1994) Osteonal and hemi-osteonal remodeling: the spatial and temporal framework for signal traffic in adult human bone. J Cell Biochem 55:273–86 doi: 10.1002/jcb.240550303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drivdahl RH, Liu CC, Baylink DJ (1984) Regulation of bone repletion in rats subjected to varying low-calcium stress. Am J Physiol 246:R190–6 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.2.R190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheng MH, Lau KW, Lakhan R, Ahmed ASI, Rundle CH, Biswanath P, Baylink DJ (2017) Unique Regenerative Mechanism to Replace Bone Lost During Dietary Bone Depletion in Weanling Mice. Endocrinology 158:714–29 doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau KH, Baylink DJ, Sheng MH (2015) Osteocyte-derived insulin-like growth factor I is not essential for the bone repletion response in mice. PLoS One 10:e0115897 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheng MH, Baylink DJ, Beamer WG, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Lau KH, Wergedal JE (1999) Histomorphometric studies show that bone formation and bone mineral apposition rates are greater in C3H/HeJ (high-density) than C57BL/6J (low-density) mice during growth. Bone 25:421–9 doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00184-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debacq-Chainiaux F, Erusalimsky JD, Campisi J, Toussaint O (2009) Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc 4:1798–806 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willinghamm MD, Brodt MD, Lee KL, Stephens AL, Ye J, Silva MJ (2010) Age-related changes in bone structure and strength in female and male BALB/c mice. Calcif Tissue Int 86:470–83 doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9359-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK et al. (2018) Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med 24:1246–56 doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herranz N, Gil J (2018) Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest 128:1238–46 doi: 10.1172/JCI95148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sims NA (2016) Senescent Osteocytes: Do They Cause Damage and Can They Be Targeted to Preserve the Skeleton? J Bone Miner Res 31:1917–19 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. (1995) A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:9363–7 doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itahana K, Dimri G, Campisi J (2001) Regulation of cellular senescence by p53. Eur J Biochem 268:2784–91 doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CH, van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Fan AC, Bachireddy P, Felsher DW (2007) Cellular senescence is an important mechanism of tumor regression upon c-Myc inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:13028–33 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701953104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuhmacher M, Eick D (2013) Dose-dependent regulation of target gene expression and cell proliferation by c-Myc levels. Transcription 4:192–7 doi: 10.4161/trns.25907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephens AS, Stephens SR, Hobbs C, Hutmacher DW, Bacic-Welsh D, Woodruff MA, Morrison NA (2011) Myocyte enhancer factor 2c, an osteoblast transcription factor identified by dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-enhanced mineralization. J Biol Chem 286:30071–86 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.253518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habib T, Park H, Tsang M, de Alboran IM, Nicks A, Wilson L, Knoepfler PS, Andrews S, Rawlings DJ, Eisenman RN, Iritani BM (2007) Myc stimulates B lymphocyte differentiation and amplifies calcium signaling. J Cell Biol 179:717–31 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raffeiner P, Schraffl A, Schwarz T, Rock R, Ledolter K, Hartl M, Konrat R, Stefan E, Bister K (2017) Calcium-dependent binding of Myc to calmodulin. Oncotarget 8:3327–43 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan AJ, Jacob R (1994) Ionomycin enhances Ca2+ influx by stimulating store-regulated cation entry and not by a direct action at the plasma membrane. Biochem J 300 (Pt 3):665–72 doi: 10.1042/bj3000665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marie PJ, Kassem M (2011) Extrinsic mechanisms involved in age-related defective bone formation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:600–9 doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller I, Min M, Yang C, Tian C, Gookin S, Carter D, Spencer SL (2018) Ki67 is a Graded Rather than a Binary Marker of Proliferation versus Quiescence. Cell Rep 24:1105–12 e5 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergman RJ, Gazit D, Kahn AJ, Gruber H, McDougall S, Hahn TJ (1996) Age-related changes in osteogenic stem cells in mice. J Bone Miner Res 11:568–77 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melnik S, Werth N, Boeuf S, Hahn EM, Gotterbarm T, Anton M, Richter W (2019) Impact of c-MYC expression on proliferation, differentiation, and risk of neoplastic transformation of human mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 10:73 doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1187-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanson KD, Shichiri M, Follansbee MR, Sedivy JM (1994) Effects of c-myc expression on cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 14:5748–55 doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5748-5755.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhuang D, Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Tang WH, Patil S, Wawrzyniak JA, Berman AE, Giordano TJ, Prochownik EV, Soengas MS, Nikiforov MA (2008) C-MYC overexpression is required for continuous suppression of oncogene-induced senescence in melanoma cells. Oncogene 27:6623–34 doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semsei I, Ma SY, Cutler RG (1989) Tissue and age specific expression of the myc proto-oncogene family throughout the life span of the C57BL/6J mouse strain. Oncogene 4:465–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanai R, Tetsuo F, Ito S, Itsumi M, Yoshizumi J, Maki T, Mori Y, Kubota Y, Kajioka S (2019) Extracellular calcium stimulates osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells by enhancing bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression. Cell Calcium 83:102058 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2019.102058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capiod T (2011) Cell proliferation, calcium influx and calcium channels. Biochimie 93:2075–9 doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takaoka S, Yamaguchi T, Yano S, Yamauchi M, Sugimoto T (2010) The Calcium-sensing Receptor (CaR) is involved in strontium ranelate-induced osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. Horm Metab Res 42:627–31 doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raza M, Deshpande LS, Blair RE, Carter DS, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ (2007) Aging is associated with elevated intracellular calcium levels and altered calcium homeostatic mechanisms in hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett 418:77–81 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez A, Vitorica J, Satrustegui J (1988) Cytosolic free calcium levels increase with age in rat brain synaptosomes. Neurosci Lett 88:336–42 doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90234-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao Y, Erxleben C, Abramowitz J, Flockerzi V, Zhu MX, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L (2008) Functional interactions among Orai1, TRPCs, and STIM1 suggest a STIM-regulated heteromeric Orai/TRPC model for SOCE/Icrac channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:2895–900 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712288105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Ramachandran A, Zhang Y, Koshy R, George A (2018) The ER Ca(2+) sensor STIM1 can activate osteoblast and odontoblast differentiation in mineralized tissues. Connect Tissue Res 59:6–12 doi: 10.1080/03008207.2017.1408601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi H, Srikanth S, Atti E, Pirih FQ, Nervina JM, Gwack Y, Tetradis S (2018) Deletion of Orai1 leads to bone loss aggravated with aging and impairs function of osteoblast lineage cells. Bone Rep 8:147–55 doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.