Abstract

Background:

Social media is a central context in which teens interact with their peers, creating opportunities for them to view, post, and engage with alcohol content. Given that adolescent peer interactions largely occur on social media, perceptions of peer alcohol content posting may act as potent risk factors for adolescent alcohol use. Accordingly, the pre-registered aims of this study were to (1) compare perceived friend, typical person, and an adolescent’s own posting of alcohol content to social media, and (2) examine how these perceptions prospectively relate to alcohol willingness, expectancies, and use after accounting for offline perceived peer alcohol use.

Methods:

This longitudinal study included 435 adolescents (M age=16.91) in 11th (48%) and 12th grade (52%). Participants completed measures of alcohol content social media posts, perceived peer alcohol use, willingness to drink alcohol, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol use at two time points, three months apart.

Results:

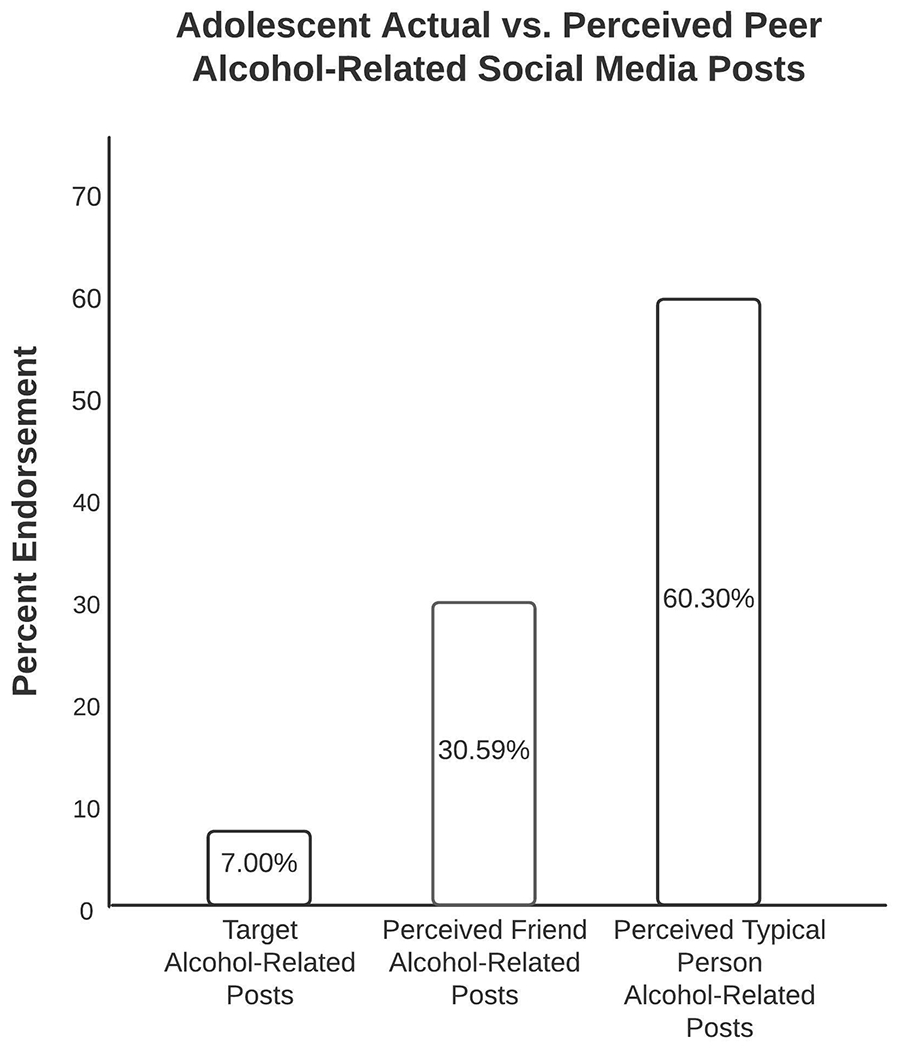

Consistent with pre-registered hypotheses, adolescents reported that 60.3% of the typical person their age and 30.6% of their friends post alcohol content to social media. In contrast, only 7% of participants reported that they themselves posted such content to social media. Neither perceived friend nor typical person alcohol content social media posts were prospectively associated with willingness to drink or positive or negative alcohol expectancies, after accounting for offline perceived peer drinking norms. Perceived friend alcohol content posts were prospectively positively associated with past 30-day alcohol consumption even after controlling for offline perceived peer drinking norms.

Conclusions:

Adolescents misperceived the frequency of alcohol related posting on social media among their peers, and perceptions of friend alcohol content posts prospectively predicted alcohol use. Given the results from the current study and the ubiquity of social media among adolescents, prevention efforts may benefit from addressing misperceptions of alcohol related posting on social media.

Keywords: adolescence, alcohol use, social media, alcohol content social media posts, alcohol expectancies

Introduction

Adolescents’ peer interactions are now taking place largely in the context of social media (Rideout and Robb, 2021). The transformation framework, a contemporary theoretical perspective on social media, argues that the features of social media transform these peer experiences and uniquely influence adolescent behavior (Nesi et al., 2018). Given the increased susceptibility to peer influence during adolescence (Shulman et al., 2016), social media-related social influences, such as perceptions of peer alcohol content posting, may act as potent risk factors for adolescent alcohol use (Curtis et al., 2018). Understanding prospective associations between perceptions of peer alcohol content posting to social media, while accounting for offline perceived peer alcohol use, on adolescent alcohol attitudes and alcohol use behaviors is needed to inform interventions meant to combat social influences on adolescent alcohol use. Accordingly, the current study sought to address several gaps in existing research on perceptions of peer alcohol content posts. First, we examine how often adolescents report posting alcohol content to social media in comparison to how often they report their friends and the typical person their age post alcohol content to social media. Second, we examine prospective associations between perceived friend and typical person alcohol content posting in relation to adolescent alcohol attitudes (willingness to drink and positive and negative alcohol expectancies) and alcohol use behaviors (consumption and binge drinking). Third, these prospective associations are examined controlling for offline perceptions of close friend and typical classmate alcohol use.

Perceptions of Peer Alcohol Content Posting to Social Media

The Focus Theory of Normative Conduct notes that social norms represent rules and standards that guide or constrain behavior (Cialdini et al., 1991). Descriptive norms, perceptions of peer alcohol use, are a social normative influence robustly associated with adolescent alcohol use (Meisel and Colder, 2020). According to the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct, individuals adjust their behaviors to align with their perceptions of peers’ behavior because norms dictate socially acceptable behavior (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). Adolescents may be particularly susceptible to social drinking norms due to the developmental salience of obtaining peer status and acceptance (Meisel and Colder, 2015), the gregariousness and popularity associated with adolescents who drink alcohol (Gerrard et al., 2008, Gerrard et al., 2002), and the extent to which adolescents overestimate their peers’ alcohol use (Cox et al., 2019). The finding that adolescents overestimate the extent to which their peers consume alcohol serves as the theoretical basis for many brief interventions which provide normative feedback, information on the actual alcohol use of peers their age, to reduce adolescent drinking (e.g., Dotson et al., 2015, Feldstein Ewing et al., 2021).

According to the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct, social norms exert a stronger influence on behavior when they are highly salient (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). The unique features of social media, particularly the public nature of alcohol content posts and the ability to receive “likes,” comments, and other reactions (e.g., emojis) for these posts, are thought to make these posts particularly salient (Nesi et al., 2018, Nesi et al., 2017, Hendriks et al., 2020). Further, posts displaying pictures of alcohol are overwhelmingly positive on social media (Hendriks et al., 2018, Cabrera-Nguyen et al., 2016, Moreno et al., 2015). Thus, perceptions of peer alcohol content posts may be particularly powerful predictors of adolescent alcohol use given the unique features of social media that may make these norms salient to adolescents.

Existing longitudinal research highlights the potentially salient influence of perceptions of peer alcohol content posting to social media on adolescent alcohol use. Research with first-year college students found perceptions of the frequency of peer alcohol content posts during the first six weeks of college to prospectively predict alcohol consumption six months later (Boyle et al., 2016). Similarly, Davis et al. (2021) found perceived peer alcohol content posts to prospectively predict alcohol frequency during the transition to college above and beyond one’s own positing of alcohol content. Findings amongst adolescent samples produce similar conclusions. Thirteen to 17 year-old adolescents who perceived that their peers more frequently posted alcohol content were more likely to consume alcohol four months later even after controlling for adolescents’ own positing of alcohol content (Geber et al., 2021). Huang et al. (2014) and colleagues found 10th graders’ perceptions of whether their peers had ever posted pictures of themselves drinking or partying online were prospectively associated with alcohol use six months later. Together, these findings provide strong initial support for prospective associations between perceptions of peer alcohol content posting frequency and adolescent alcohol use.

Of particular interest to the current study is recent work by Litt et al. (2021) which examined differences in perceptions of peer posting of alcohol content to social media relative to one’s own posting of alcohol content in a cross-sectional sample of youth ages 15-20. Youth in this study overestimated their peers’ frequency and acceptability of posting alcohol content to social media. Additionally, the discrepancy between perceived typical person their age and youth’s own posting alcohol content to social media was associated with greater willingness to drink and drinks per week. Considering these findings, the first aim of the current study was to replicate and extend the work of Litt et al. (2021) by comparing an adolescent’s alcohol content posting to social media to their perceptions of alcohol content posting by multiple reference groups (i.e., friend and typical student). If discrepancies exist in perceptions of the prevalence of this behavior across reference groups, a potential target for future normative feedback information may be providing corrective information regarding the frequency of alcohol content posts to social media.

Willingness to Drink and Alcohol Expectancies

Although rates of alcohol use increase from early through late adolescence, the majority of 8th (79.5%) and 10th (59.3%) graders and almost half of 12th graders (44.7%) report not using alcohol in the past year (Miech et al., 2021). Given the low prevalence of alcohol use, which may be a function of the limited availability of alcohol use during adolescence, one possible mechanism by which perceptions of peer-alcohol content influences alcohol use is by altering adolescent alcohol use attitudes. Indeed, experimental studies manipulating adolescent exposure to peer alcohol content posts on social media have found that exposure to alcohol content posts are associated with greater willingness to use alcohol, more positive alcohol attitudes, and greater perceptions of peer alcohol use (i.e., descriptive norms; Litt and Stock, 2011, Mesman et al., 2020). Non-experimental studies have also demonstrated that the association between perceived peer alcohol content posts and adolescent alcohol use are mediated through descriptive drinking norms ((Davis et al., 2019), perceived approval of peer alcohol use, injunctive drinking norms, (Nesi et al., 2017), and alcohol-related attitudes (Geusens and Beullens, 2016). Litt et al. (2021) found greater discrepancies between an adolescent’s own and their perceived peer alcohol content posts to social media were cross-sectionally associated with willingness to drink.

Building on this work, the second aim of the current study was to prospectively examine associations between perceived friend and typical person posting alcohol content to social media with an adolescent’s willingness to drink, as well as their positive and negative alcohol expectancies. The Prototype Willingness Model argues that willingness to drink is a key predictor of adolescent substance use (Gerrard et al., 2008). According to this theoretical perspective, adolescent alcohol use is not always purposeful and when adolescents find themselves in risky situations (e.g., at a party), willingness to drink, rather than more deliberative cognitive processes (e.g., alcohol intentions) drive drinking behaviors. Consistent with the Prototype Willingness Model, willingness to drink is a consistent predictor of adolescent alcohol use (Andrews et al., 2011, Lewis et al., 2020). Importantly, perceptions of peer alcohol use are conceptualized as a predictor of willingness to drink in the Prototype Willingness Model.

A second alcohol-related cognition discussed in the Prototype Willingness Model is alcohol expectancies. Positive alcohol expectancies refer to the perceived likelihood of positive outcomes from drinking (e.g., have fun, feel more friendly). Negative alcohol expectancies refer to the perceived likelihood of negative outcomes from alcohol (e.g., act stupid, feel sick to their stomach). During adolescence, expectations regarding the positive effects of alcohol increase, whereas expectations about negative effects decrease (Smit et al., 2018). Expectancies during adolescence have been prospectively associated with alcohol use across months, years, and decades (Patrick et al., 2010). Social Learning Theory argues that alcohol expectancies develop through indirect (e.g., alcohol use depicted on social media, peer alcohol use) and direct drinking experiences, and these expectations influence an individual’s decision to drink (Bandura and McClelland, 1977, Moreno and Whitehill, 2014). Thus, perceived peer alcohol content posts, an indirect learning experience, may alter adolescents’ alcohol expectancies. Prior work with college students has demonstrated cross-sectional associations between e-cigarette post exposure and positive, but not negative, e-cigarette expectancies (Pokhrel et al., 2018). To our knowledge, no prior work has examined whether perceived peer alcohol content posts are associated with adolescent alcohol expectancies.

Offline Normative Influences

When studying first-year college student perceptions of their peers’ posting of alcohol content to social media, Boyle et al. (2016) argued that it is important to control for offline (i.e., outside of social media) perceived peer alcohol use (i.e., descriptive drinking norms). To date, several studies have controlled for perceptions of peer or typical student alcohol use to demonstrate the unique effects of perceptions of alcohol content posts to social media on alcohol use outcomes (Boyle et al., 2018, Huang et al., 2014, Boyle et al., 2016). In line with this prior work, the current study controlled for perceived close friend and same-aged typical student alcohol use to demonstrate whether perceptions of peer alcohol content social media posts have unique predictive validity above and beyond offline normative perceptions.

Current Study

The current study forwards the following pre-registered hypotheses (https://osf.io/dcy97/?view_only=14b2d5f529324cc190d65740827b95e5): (1) Adolescents were hypothesized to be more likely to report that their friends and the typical person their age have posted alcohol content to social media relative to their own posting of alcohol content to social media. (2) Perceptions of friend and typical person alcohol content posts to social media were hypothesized to prospectively predict greater willingness to drink alcohol, positive alcohol expectancies, 30-day adolescent alcohol use, and adolescent binge drinking, and lower levels of negative alcohol expectancies. (3) Given the unique features of social media that may increase the salience of normative perceptions of alcohol content posts, the prospective effects in Hypothesis 2 were hypothesized to remain significant after controlling for perceived close friend and typical student alcohol use (offline descriptive norms).

Methods

Participants

Adolescents were recruited from a longitudinal study examining risk and protective factors for the initiation and escalation of adolescent substance use (see Jackson et al., 2016). The present study focuses on a subset of participants from the full sample (N=1,023), which included 435 adolescents between the ages of 16 and 20 (M=16.91). At the first assessment, 207 adolescents were in 11th grade (48%) and 228 were in 12th grade (52%). The biological sex of 60% of the sample was female (N=262) and 40% was male (N=173). The sample was majority White (76%) and 2% was American Indian/Alaskan Native, 4% was Asian, 4% was Black, 0.5% was Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 5% was multi-racial. Thirteen percent of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Chi-square and analysis of variance tests were conducted to assess potential differential attrition at follow-up. Significant differences emerged with respect to age such that older adolescents were more likely to discontinue participation (χ2(4)=11.50, p=.02, φ=.16). Youth who spent less time on social media were also more likely to discontinue participation (F(1)=5.71, p=.01, η2=.01). There were no significant differences amongst adolescents who did and did not complete time 2 (T2) on time 1 (T1) own or perceived friend or typical person alcohol content posts, time on social media, frequency of social media posts, gender, perceived close friend and typical student alcohol use, positive and negative alcohol expectancies, willingness to drink, past 30-day alcohol consumption, and past 30-day binge drinking.

Procedures.

Participants were recruited from six regional middle schools (one urban, two rural, three suburban) in the Northeast U.S. and enrolled into the study on a semi-annual basis. Students were identified through school rosters and study information and consent forms were mailed to each student’s home. Materials were also distributed in homeroom classes by faculty. Classroom-level incentives were provided for return of a signed consent form (regardless of whether the form indicated consent). Consent forms were returned from 38% of students (65% were consents allowing for participation); 88% of these were enrolled into the study. As compared to state-wide Department of Education school data, the resulting sample was largely representative of the schools from which they were drawn, with samples obtained at five of six schools accurately representing the school gender and grade distribution. There was also accurate representation of the proportion of White youth for four of six schools and Hispanic youth in three schools, with a greater proportion of Hispanic students in the sample for the other three schools. Students receiving subsidized lunch were underrepresented in the samples obtained from three schools, suggesting that the sample is more racially diverse than the school populations but also less economically disadvantaged.

Participants attended an in-person group orientation session which included a project overview and the definition of a standard drink as well as administration of a 45-minute computerized baseline survey. Staff also collected contact information and emphasized finding a private location to complete surveys. Follow-up assessments included a series of semi-annual surveys as well as shorter monthly surveys for a two-year period, followed by a series of quarterly assessments through high school end. Number of total assessments varied as a function of school cohort and grade at enrollment; see (Jackson et al., 2016) for detail on the full study design including timing of assessments. All follow-up assessments were conducted using web-based surveys which could be completed from any location with Internet access. Multiple reminders (mailed card, email, text, phone calls) alerted participants that the survey was open. The social media items used in the present study were added to the larger project in 2015, which corresponded to quarterly surveys during high school. At this point, 588 participants were no longer in the study because they had aged out of the study upon high school graduation or they failed to complete that quarterly assessment. The remaining 435 participants first received the social media assessment during 10th, 11th, or 12th grade. For 10th graders we used the second social media assessment to ensure greater homogeneity in age across the sample, yielding 435 students who completed the social media survey as an 11th or 12th grader. Present study data were taken from two study waves. Of note, alcohol expectancies and perceived peer drinking norms were not assessed during the timepoint when social media questions were administered. Accordingly, T1 measures for alcohol expectancies and perceived peer drinking norms were taken from the prior assessment period, three months earlier, in order to be able to examine change in these outcomes relative to the prior time point. T1 occurred when participants were in either 11th or 12th grade and T2 occurred three months later. Retention was excellent across the two time points (92%; N=400). Procedures were approved by the university institutional review board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from NIAAA.

Measures

Willingness to Drink (T1 and T2).

Willingness to drink alcohol was assessed using three items developed for the current study which were preceded by the statement “Suppose you were with a group of friends and there was some alcohol there that you could have if you wanted.”: “How willing would you be to have a sip?” “How willing would you be to drink one drink?” and “How willing would you be to have more than one drink?” The responses to these three questions were on a 4-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (definitely willing) to 4 (definitely not willing). Items were reverse scored so higher values indicated a greater willingness to use alcohol. Willingness to drink had good internal consistency at T1 (α=.82) and T2 (α=.82).

Alcohol Expectancies (T1 and T2).

Alcohol expectancies were assessed using a developmentally adapted scale from Schell et al. (2005). This measure assesses positive (e.g., “feel more friendly,” “have fun,” “feel relaxed”) and negative expectancies (e.g., “have trouble thinking,” “get into fights,” “say things they wish they hadn’t said”) regarding the affective, cognitive, and behavioral effects of alcohol. Items were preceded with the following prompt: “How likely is it that the following things would happen to people your age if they had one or more drinks of alcohol?” Response options for this measure ranged from very unlikely (1) to very likely (4). Nine items assessed positive expectancies at T1 (α=.97) and T2 (α=.96) and 13 items assessed negative expectancies at T1 (α=.94) and T2 (α=.94).

Alcohol Use (T1 and T2).

Frequency of alcohol use was assessed using the item “During the past 30 days, how often did you drink alcohol?” Response options for this measure were: (1) didn’t drink in past 30 days, (2) once during the past 30 days, (3) 2-3 times during the past 30 days, (4) 1 to 2 times a week, (5) 3 to 4 times a week, (6) 5 to 6 times a week, and (7) every day. Quantity of alcohol use was assessed using the item “During the past 30 days, when you were drinking alcohol, how many drinks did you usually have on any one occasion?” Responses for this question ranged from less than one drink (1) to more than 12 drinks (11). These items were combined to compute a quantity x frequency index capturing total number of drinks consumed in the past 30 days. To reduce the influence of outliers, past 30 day drinks consumed values greater than three standard deviations above the mean were recoded to three standard deviations above the mean (Tabachnick et al., 2007). This resulted in 2 (0.005%) and 4 (0.01%) observations being recoded at T1 and T2, respectively.

Past 30-day binge drinking was assessed by asking participants how often they had 5 (males)/4 (females) drinks in a single occasion during the past 30 days. Due to low endorsement of this item, responses were dichotomized (0=no past 30-day binge drinking, 1=past 30-day binge drinking).

Perceptions of Peer and Typical Person Alcohol-Content Social Media Posts (T1).

Adolescents were asked questions regarding their friends, “Do your social media friends/followers post general references to alcohol (logos, links to videos, alcohol images)?” and “Do your social media friends/followers post pictures or videos of people drinking alcohol?” (1=yes, 0=no), and typical person their age, “The typical person my age posts references to alcohol” and “The typical person my age posts photos of alcohol use” (0=not at all true to 2=very true), alcohol-related social media posts. To align the response options for these two reference groups, responses for questions assessing perceptions of typical person alcohol-related social media posts were dichotomized (1=yes, 0=no). Responses to these two questions for “friends” and “typical person” were recoded such that a score of 1 reflected any endorsement of perceived posting of alcohol content and scores of 0 reflected no perceived alcohol content posts. The internal consistency of the two questions for friends (α=.82) and typical person (α=.89) were good.

Adolescent’s Own Alcohol-Content Social Media Posts (T1).

Adolescents were asked whether they had “Posted general references to alcohol (logos, links to videos, alcohol images),” “Posted pictures or videos of yourself drinking alcohol,” or “Posted pictures or videos of friends drinking alcohol” (1=yes, 0=no). Consistent with the scoring procedure for perceived friend and typical person alcohol content posts, responses to these three questions were summed and then dichotomized (1= posted alcohol-related content, 0= did not post alcohol-related content). The internal consistency for these three items was adequate (α=.72).

Social Media Posting Frequency (T1).

To control for individual differences in how often adolescents post content to social media in general, adolescents were asked a single question “I post to social media.” Responses to this question were on a 10-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (10+ time/day) to 10 (less than once per year). This item was reverse coded such that higher values equaled greater social media posting frequency.

Time on Social Media (T1).

Some studies have found associations between time spent on social media and adolescent alcohol use (Curtis et al., 2018, Ng Fat et al., 2021). Accordingly, participants were asked “On average, approximately how much time per day do you spend on social media?” on a 7-point Likert-scale (1=less than 10 minutes to 7=4 hours or more).

Perceptions of Peer and Typical Person Alcohol Use (T1).

Two items, adapted from a measure of peer delinquency by Arthur et al. (1997), were used to assess perceptions of friend alcohol use. Adolescents were asked to “Think of your three best friends (the friends you feel closest to). In the past 6 months, have any of your friends”: “Tried beer, wine, or hard liquor (for example: vodka, whiskey, or gin) when their parents didn’t know about it” and “been drunk” (1=yes, 0=no). Responses to these two items were summed and then dichotomized (0=no perceived peer alcohol use, 1=perceived peer alcohol use). Typical person descriptive drinking norms were assessed using a measure adapted from Wood et al. (2004). Adolescents were asked “during the school year, how often do you think that the typical classmate in your grade drinks alcohol” (0=typical classmate does not drink during the school year to 9=typical classmate drinks twice a day or more) and “during the school year, how many drinks do you think the typical classmate in your grade usually has on any one occasion” (open ended response). Perceptions of friend (α=.84) and typical person (α=.68) alcohol use were good and near-acceptable, respectively.

Data Analytic Plan

Hypothesis 1.

McNemar’s chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in endorsement rates of adolescent’s posting alcohol content to social media, perceived friend posting of alcohol content, and perceived typical person posting of alcohol content (see supplemental materials for deviations from pre-registered analyses). McNemar’s test was selected given these data were categorical (0=has not posted alcohol content, 1=posted alcohol content) as well as the paired nature of the data (Hoffman, 1976).

Hypotheses 2 and 3.

A two-step process was used to model the relationship between perceptions of friend and typical person alcohol content posts and willingness to drink, positive and negative alcohol expectancies, and past 30-day alcohol consumption and binge drinking. First, measurement models were estimated for outcome measures with three or more indicators (willingness to drink and alcohol expectancies). Second, hybrid models were estimated where structural paths were added to the model such that perceptions of friend and typical person alcohol content posts predicted willingness to drink (Figure 2), positive and negative alcohol expectancies (Figure 3), and past 30-day alcohol consumption and binge drinking (Figure 4) controlling for an adolescent’s posting alcohol content to social media, frequency of social media posting, time spent on social media, age, and biological sex as well as the corresponding T1 outcome measures (Hypothesis 2). To assess whether perceptions of peer and typical person posting alcohol content to social media predicts alcohol attitude and use outcomes above and beyond perceptions of close friend and classmate alcohol use (Hypothesis 3), descriptive drinking norms were added to these models (see Figure 2–4).

Figure 2.

Hybrid Model Results Predicting Willingness to Drink.

Note. W= indicator of willingness to drink, T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2. Nonsignificant parameters are represented by gray dotted lines. ß and SE(B) are presented for all significant associations. Biological sex and age, control variables in the above models, are not presented to reduce figure complexity. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Figure 3.

Hybrid Model Results Predicting Positive and Negative Alcohol Expectancies.

Note. P=parceled indicator of positive expectancies, N=parceled indicator of negative expectancies, T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2. Non-significant parameters are represented by gray dotted lines. ß and SE(B) are presented for all significant associations. Biological sex and age, control variables in the above models, are not presented to reduce figure complexity. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Figure 4.

Path Analysis Results Predicting Past 30-Day Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking.

Note. Non-significant parameters are represented by gray dotted lines. B and SE(B) are presented for all significant associations. Past 3-day binge drinking is a dichotomous outcome, thus coefficients predicting this outcome are logit estimates. Biological sex and age, control variables in the above models, are not presented to reduce figure complexity. *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Measurement and hybrid models for willingness to drink and alcohol expectancies were estimated with maximum likelihood estimation. A negative binomial path model estimated with robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) was used to test the path model for alcohol consumption and binge drinking since binge drinking was a dichotomous outcome and alcohol consumption was non-normally distributed (see Table 1). Overall, relative fit criteria, Akaike, Bayesian, and sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (AIC, BIC, aBIC) suggested that a negative binomial model provided a better fit to the alcohol consumption data compared to a zero-inflated negative binomial model. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) were used to assess model fit. Since specific cut-offs for assessing “good” fit cannot be generalized across all models (Marsh et al., 2004), ranges were used to determine model fit acceptability (for CFI and TLI, <.90 is poor, .90 to .94 is acceptable, and >.95 is excellent; for RMSEA, .08 is poor, .05 to .07 is acceptable, and <.05 is excellent; and for SRMR, .09 is poor, .06 to .09 is acceptable, and <.06 is excellent). Only relative fit indices were available for past 30-day alcohol consumption and binge drinking models (see supplemental materials for detailed information regarding specification of these models).

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol Use T1 | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Alcohol Use T2 | 0.43 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Binge Drinking T1 | 0.74 | 0.36 | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Binge Drinking T2 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.49 | - | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Willingness to Drink T1 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.25 | - | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Willingness to Drink T2 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.79 | - | |||||||||||||

| 7. Negative Exp. T1 | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.12 | −0.14 | −0.21 | - | ||||||||||||

| 8. Negative Exp. T2 | −0.14 | −0.18 | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.24 | −0.28 | 0.58 | - | |||||||||||

| 9. Positive Exp. T1 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.15 | - | ||||||||||

| 10. Positive Exp. T2 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.54 | - | |||||||||

| 11. Perceived Friend Alcohol Posts | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | - | ||||||||

| 12. Perceived Typical Person Alcohol Posts | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | - | |||||||

| 13. Target Alcohol Posts | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.14 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.07 | - | ||||||

| 14. Posting Frequency | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.20 | - | |||||

| 15. Friend DN | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.41 | −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | - | ||||

| 16. Classmate DN | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.26 | - | |||

| 17. Social Media Time | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.07 | - | ||

| 18. Age | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.12 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.08 | - | |

| 19. Sex | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.20 | −0.15 | −0.21 | −0.02 | −0.24 | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.30 | −0.02 | - |

| Mean | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.96 | 2.07 | 3.11 | 3.12 | 2.87 | 2.96 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 5.99 | 0.26 | 2.18 | 4.21 | 16.91 | 0.40 |

| SD | 2.27 | 1.59 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 2.63 | 0.44 | 1.83 | 1.78 | 0.67 | 0.49 |

| Skewness | 5.18 | 4.76 | 4.23 | 5.29 | 0.64 | 0.46 | −1.21 | −0.85 | −0.89 | −0.73 | 0.85 | −0.42 | 3.33 | −0.27 | 1.11 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Kurtosis | 28.88 | 24.37 | 15.96 | 26.14 | −0.92 | −1.04 | 1.44 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 0.73 | −1.29 | −1.83 | 9.10 | −0.89 | −0.76 | 2.08 | −1.00 | 0.76 | −1.83 |

Note. Exp=expectancies. Significant correlations (p<.01?) are bolded. T2 was three months following T1.

Note. W= indicator of willingness to drink, T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2. Nonsignificant parameters are represented by gray dotted lines. ß and SE(B) are presented for all significant associations. Biological sex and age, control variables in the above models, are not presented to reduce figure complexity.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Note. P=parceled indicator of positive expectancies, N=parceled indicator of negative expectancies, T1=Time 1, T2=Time 2. Non-significant parameters are represented by gray dotted lines. ß and SE(B) are presented for all significant associations. Biological sex and age, control variables in the above models, are not presented to reduce figure complexity.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Results

Descriptive Statistics.

Rates of past 30-day alcohol use at T1 were 9.47% and 13.83% at T2. These rates of use are lower compared to nationally representative samples. Monitoring the Future (MTF; Miech et al., 2016) found rates of past 30-day alcohol use to be 35.3% among 12th graders and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS; Kann et al., 2018) found 40.8% of 12th graders consumed alcohol in the past 30 days. Similarly, whereas rates of past 30-day binge drinking were 4.83% and 3.25% at T1 and T2 respectively, YRBSS found rates 14.7% of 12th graders binge drank in the past 30-days. Given these discrepant rates, this sample is likely biased towards low-risk adolescents, however, the discrepancy between this sample and national samples is not as great as might first appear. For example, YRBSS data at the time during which our middle school data were collected indicate that 23% of RI middle school students report drinking “more than just a few sips,” compared to 37% of our sample having “ever had a sip of alcohol” and 8% having had “a full drink of alcohol.” Similar rates are observed with MTF data: 33% of MTF 8th graders consume “more than just a few sips,” compared to 55% of our sample sipping and 15% consuming a full drink.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for the variables included in the current study. Perceptions of friend alcohol content posts were positively associated with T1 past 30-day alcohol consumption and binge drinking, T1 and T2 willingness to drink, and T2 positive alcohol expectancies (r range=.11-.29). Perceptions of typical person alcohol content posts were positively associated with T1 and T2 past 30-day alcohol consumption and T1 past 30-day binge drinking, T1 and T2 willingness to drink, and T1 and T2 positive and negative alcohol expectancies (r range=.11-.23). An adolescent’s own alcohol content posts were positively associated with T1 and T2 past 30-day alcohol consumption and binge drinking, willingness to drink, and negatively associated with T1 negative alcohol expectancies (r range=|.14-.24|). Perceived friend alcohol content posts were positively associated with perceived typical person and an adolescent’s own alcohol content posts (r range=.27-.31). An adolescent’s perceptions of the typical person’s alcohol-related posts and their own alcohol-related posts were unrelated.

Hypothesis 1: Differences in Own and Perceived Peer Alcohol Content Posts

Figure 1 presents the percent of adolescents who posted alcohol content to social media, as well adolescents’ perceptions of whether their friends and the typical person their age had posted alcohol content to social media. Adolescents were significantly more likely to perceive that their friends (χ2=81.81(1), p<.0001; 30.59% endorsement) and typical person their age (χ2=198.12(1), p<.0001; 60.30% endorsement) had posted alcohol content to social media compared to their own endorsement (7%) of posting alcohol content to social media. Adolescents were also more likely to perceive that the typical person their age had posted alcohol content to social media compared to their perceptions of whether their friends have posted alcohol content to social media (χ2=87.96(1), p<.0001).

Figure 1.

Differences in actual vs. friend and typical person alcohol content posts to social media

Hypotheses 2 and 3: Perceived Peer Alcohol Content Posts and Alcohol Attitudes and Behaviors

Willingness to Drink

Detailed information regarding the measurement model for willingness to drink alcohol as well as tables of the hybrid model results can be found in the supplemental materials. The final measurement model for willingness to drink alcohol at T1 and T2 provided a good fit to the data (χ2(8)=25.137, p=.002; CFI=1.00, TLI=.99; RMSEA=.07, SRMR=.02). Next, prospective paths from T1 to T2 were added to the model. The hybrid model provided a good fit to the data (χ2(38)=60.55, p=.01; CFI=.99, TLI=.99; RMSEA=.04, SRMR=.02). Perceived friend and typical student alcohol content posting were unrelated to T2 willingness to drink (see Figure 2). The only significant predictors of T2 willingness to drink were willingness to drink at T1 and T1 past 30-day alcohol consumption. This model accounted for 71% of the variance in T2 latent willingness to drink.

Next, perceived close friend and classmate alcohol use were added to the model (χ2(46)=64.65, p=.03; CFI=1.00, TLI=.99; RMSEA=.03, SRMR=.02). Descriptive norms for close friends and classmates were unrelated to T2 willingness to drink (see Figure 2). Again, the only significant predictors in this model were T1 willingness to drink and past 30-day alcohol consumption (R2=.71).

Positive and Negative Alcohol Expectancies

The final measurement model for positive and negative alcohol expectancies provided a good fit to the data for all fit statistics other than SRMR (χ2(184)=677.01, p<.0001; CFI=.95, TLI=.95; RMSEA=.08, SRMR=.13). Next, prospective paths from T1 to T2 were added to the model (see Figure 3). The hybrid model provided an acceptable fit to the data (χ2(310)=864.94, p<.0001; CFI=.94, TLI=.93; RMSEA=.06, SRMR=.04). Adolescent perceptions of whether the typical student their age posted alcohol content to social media were positively associated with negative alcohol expectancies. Alcohol consumption was prospectively associated with lower positive and negative alcohol expectancies. Males had lower levels of positive and negative alcohol expectancies and alcohol use. This model accounted for 40% of the variance in positive alcohol expectancies and 36% of the variance in negative alcohol expectancies.

When perceived close friend and classmate descriptive norms were added to the model (χ2(342)=914.09, p<.0001; CFI=.94, TLI=.93; RMSEA=.06, SRMR=.04) perceived typical student alcohol content posting was no longer associated with negative alcohol expectancies (see Figure 3). Perceived close friend alcohol use was unrelated to positive alcohol expectancies and negatively associated with negative alcohol expectancies. Greater perceived classmate alcohol use were prospectively associated with greater positive alcohol expectancies. This model including descriptive norms accounted for an additional 1% of the variance in positive and negative alcohol expectancies.

Past 30-Day Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking

Perceived friends alcohol content posts to social media were prospectively associated with greater past 30-day alcohol consumption at T2 (see Figure 4). Perceived typical student alcohol content posts and an adolescent’s own posting of alcohol content were unrelated to T2 alcohol consumption. Adolescents who endorsed binge drinking at T1, were older, and females engaged in higher levels of alcohol consumption at T2. An adolescent’s own posting of alcohol content to social media was prospectively positively associated with binge drinking at T2 (OR=11.11, 95% CI [1.16, 106.07]). Binge drinking at T1 prospectively predicted binge drinking at T2 (OR=50.86, 95% CI [8.93, 289.77]).

Perceived friend alcohol posts to social media remained a significant predictor of alcohol consumption after controlling for perceived close friend and classmate descriptive drinking norms (see Figure 4). An adolescent’s own posting of alcohol content to social media was no longer significantly associated with binge drinking after controlling for perceived close friend and classmate descriptive drinking norms. Perceived close friend alcohol use was positively associated with T2 alcohol consumption but not binge drinking. Perceptions of classmate alcohol use was unrelated to alcohol consumption or binge drinking.

Discussion

Social media now represents a central context through which teens interact with peers, creating new opportunities to view, post, and engage with alcohol-related content. However, few studies have rigorously examined adolescents’ perceptions of peer alcohol content posting, and how such perceptions influence teens’ own alcohol attitudes and use behaviors. Thus, the current study offers a novel investigation of adolescents’ alcohol-related social media engagement, within a large sample using a prospective longitudinal framework. Results highlight meaningful discrepancies between adolescents’ perceptions of peers’ alcohol posting and their own alcohol posting, as well as a nuanced portrait of associations among these perceptions and alcohol-related outcomes, including willingness to drink, alcohol expectancies, consumption, and binge drinking.

(Mis)perceptions of peers’ alcohol posting

Findings suggest significant discrepancies in participants’ perceptions of their peers’ alcohol content posts on social media, versus their own alcohol-related posting behavior. In particular, 60.3% of participants reported that a typical person their age posts alcohol-related content and 30.6% that their friends post alcohol-related content. In comparison, only 7% of participants reported that they themselves had posted such content. These findings replicate and extend prior work (Litt et al., 2021) by providing additional evidence for adolescents’ overestimation of peer’s alcohol posting activities, and by highlighting differences in perceptions across reference groups (i.e., friends and typical person their age). Considering prior work has found associations between overestimation of peer’s alcohol posting and alcohol use (Litt et al., 2021), these misperceptions may serve as an etiological risk factor linking social media to alcohol use behaviors during adolescence.

Adolescence is a key development period for susceptibility to peer influence (Shulman et al., 2016), and it is well-known that descriptive norms inform adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors surrounding a variety of both risky and prosocial behaviors (Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011). The role of social media in adolescents’ development of alcohol use norms is understudied. Social media represents a unique social context, in which information can be publicly posted for and consumed by a large audience, content often remains permanently accessible and replicable (i.e., by “resharing”), and interpersonal cues are often absent (Nesi et al., 2018). This uniqueness of social media is reflected by the high rates of exposure to peer alcohol-related posts observed in the current low-risk sample of adolescents. These findings suggest that adolescents who do not post alcohol-related content to social media still report high exposure to this content. As a result, social media presents a prime environment where adolescents may develop inaccurate perceptions of the frequency and outcomes of alcohol-related behavior. The high rates of exposure to alcohol-related content on social media among low-risk youth suggests that low-risk adolescents (i.e., minimal or no alcohol use and minimal or no posting alcohol-related content to social media) may benefit from prevention interventions to combat high levels of exposure to alcohol-related content on social media.

These features of social media may create situations in which a small number of alcohol-related posts may be shared and consumed widely, creating the illusion that such posts are common among teens. Misperceptions of the frequency of alcohol-related posts may have important consequences for adolescents, both online and offline. Longstanding prior research suggests that teens overestimate their peers’ actual drinking behavior (Cox et al., 2019). Exposure to peers’ alcohol posts on social media may exacerbate this effect, with online alcohol references serving as “proof” that peers are engaging in drinking behavior. Furthermore, descriptive norms around peers’ alcohol posting may influence adolescents’ injunctive norms (i.e., approval of peers’ alcohol posting behavior), which may, in turn, increase the likelihood that youth themselves post such content. Indeed, prior work suggests links between perceptions of peer alcohol posting and descriptive and injunctive drinking norms (Nesi et al., 2017, Davis et al., 2019, Litt and Stock, 2011).

Effects of perceived peer alcohol posting on adolescents’ alcohol attitudes and behaviors

Results provided limited support for hypotheses around the prospective associations between perceptions of peer alcohol content posting and adolescents’ attitudes (willingness to drink and alcohol expectancies) and behavior (alcohol consumption and binge drinking; Hypotheses 2 and 3). In rigorous longitudinal models controlling for adolescents’ own alcohol content posting, general social media posting frequency, time on social media, past 30-day alcohol consumption, demographics (age and sex), and descriptive norms of peers’ alcohol use, findings paint a complex portrait of associations among online and offline alcohol attitudes and behaviors.

Contrary to Hypotheses 2 and 3, no associations were revealed between adolescents’ perceptions of peer alcohol content posting and willingness to drink nor positive alcohol expectancies. These findings may partially be a function of the high stabilities (ß range=.69-.79) of these outcomes from T1 to T2. Prior work supporting associations between perceptions of peer alcohol and substance use content posting, willingness to use substances, and positive substance use expectancies used cross-sectional designs. These designs do not allow for stabilities in these substance use attitudes to be accounted for (Litt and Stock, 2011, Mesman et al., 2020, Litt et al., 2021, Pokhrel et al., 2018). Students who perceived that the typical student their age posts alcohol related content reported more negative alcohol expectancies. Associations between perceptions of peer alcohol posting and greater negative expectancies were in contrast to Hypothesis 2. Prior work has shown that youth who perceive greater alcohol-related behaviors among their peers report more positive expectancies and lower negative expectancies (Colder et al., 2017). The current sample endorsed low rates of actual alcohol use (9.47% at T1 and 13.87% at T2%). It is possible that among the majority of these youth who have no direct experience with alcohol use, viewing alcohol related posts on social media simply reinforces prior negative expectancies. Alcohol related posting may represent a somewhat risky or delinquent behavior among teens of this age; thus, perhaps those who are perceived to post such content are also viewed as engaging in behaviors which are dangerous or problematic. Notably, in contrast to Hypothesis 3, the effect of perceived peer alcohol posts was no longer present after controlling for descriptive norms around peers’ actual alcohol use. This indicates that actual, “real world” behavior may represent a stronger influence on adolescents’ expectancies than online experiences.

Finally, in terms of alcohol behavior, participants who perceived that their friends posted alcohol content also indicated higher past 30-day alcohol consumption, controlling for demographic factors, social media use, and descriptive norms around peers’ alcohol use. These findings are in line with Hypotheses 2 and 3 as well as the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct (Cialdini et al., 1991) in demonstrating the possibility that certain adolescents adjust their drinking behavior to align with highly salient social norms, such as those showcased on social media. Findings also corroborate prior evidence that exposure to peers’ alcohol related social media content may influence teens’ own drinking behavior (Geber et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2014), and speak to the particularly salient influence of friends versus more distant peers (Mesman et al., 2020). Furthermore, given that results remained significant after accounting for teens’ perceptions of their close friends’ drinking behavior, it is likely that social media plays a unique role in conferring additional risk. Notably, participants who themselves reported posting alcohol content indicated higher rates of binge drinking, but this association no longer remained after controlling for descriptive norms around peers’ alcohol use.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study provides a rigorous, longitudinal assessment of adolescents’ offline and online alcohol-related behaviors and attitudes. However, future research will benefit from building on this study’s limitations. First, rates of adolescent endorsement of posting alcohol content to social media were low. One possibility is that youth may have been less forthcoming about their posting alcohol content to social media, given that this study was completed several years ago. Endorsement rates may be higher in more recent studies, as social media use and acceptability have increased among teens in recent years (Rideout et al., 2022). Further, recent work suggests that posting alcohol content to social media is multifactorial (Ward et al., 2022). More comprehensive assessments of an adolescent’s posting alcohol content to social media that consider platform, degree of privacy, and level of engagement (e.g., original posting versus sharing versus commenting) may alter rates in which youth endorse engaging in this behavior. Unlike the measure recently developed by Ward et al. (2022), the current assessment of alcohol content posting did not assess the content of such posts. A range of alcohol-related posts are possible on social media, with some likely portraying alcohol use in a positive and some in a negative manner. Future studies might examine the content of youths’ alcohol posts using more comprehensive measurement strategies or directly, via direct observation or extraction of teens’ social media data. It should also be noted that measures assessing peers’ alcohol posts did not specifically ask whether those posts depicted the user themselves drinking, whereas measures of adolescents’ own posts did so.

Second, the reference groups for perceived peer alcohol content posting (friend, typical student) and perceived peer alcohol use (close friend, classmate) were not identical. Associations between perceptions of peer alcohol use and alcohol use have been shown to vary by reference group (Larimer et al., 2009). Future work may wish to use identical reference groups when assessing perceptions of peer alcohol content posting and alcohol use. Third, because we had low rates of return of the parental consent forms, the enrollment rate was lower than anticipated; we expect this is likely due to the intensive study design, the de-personalized contact through mailed/distributed flyers, and the focus on the sensitive topic of underage drinking. While studies with implicit/passive parental consent tend to yield higher rates of participation, when active parental consent is required in youth substance use research, participation tends to be lower with rates from 31-55% reported (Pokorny et al., 2001, Rojas et al., 2008, Doumas et al., 2015). As concluded by Frissell et al. (2004) parental nonresponse to traditional active consent procedures may reflect failure of parents to attend to the request (e.g., because of inconvenience) as opposed to explicit refusal. Because active consent requires more effort on the part of parents (Liu et al., 2017), it is possible that this impacted the characteristics of those who enrolled, such as lower rates of alcohol use compared to national samples. Additionally, the sample consisted of predominantly White older adolescents. Accordingly, the results should not be generalized to early or middle adolescence and should be replicated in more ethnically and racially diverse nationally representative samples. Results also may not generalize to adolescents with higher rates of alcohol use, or to clinical samples experiencing substance use disorders. Lastly, the two timepoints in the current study were spaced three months apart. This short time window led to high stabilities between our outcomes at T1 and T2. Studies with larger time gaps between assessments may find different results due to greater variability in their alcohol-related outcomes of interest.

Clinical Implications

Findings around discrepancies in perceptions of peer versus adolescents’ own alcohol posting behavior point to the potential utility of interventions that provide normative feedback regarding peers’ alcohol posting behavior. Prior studies suggest that brief interventions, which provide adolescents with accurate information on the frequency and quantity of their peers’ actual alcohol use, are effective in reducing adolescent drinking (Dotson et al., 2015, Feldstein Ewing et al., 2021). Furthermore, media literacy interventions have sought to inform adolescents of inaccurate alcohol portrayals within mass media (Kupersmidt et al., 2012), and more recently, to educate them on potentially harmful features of social media sites (Galla et al., 2021). Integrating components of these existing interventions may offer an opportunity to reduce adolescent alcohol-related posting behavior, as well as to reduce actual alcohol use.

Conclusion

Social media represents a central context for adolescent development, and a novel means of social influence around alcohol use. The current study suggests that adolescents misperceive the frequency of alcohol related posting on social media among their peers, and that such misperceptions may have implications for teens’ own alcohol attitudes and behaviors. Given the ubiquity of social media among adolescents, understanding its role in the development of alcohol use norms and subsequent use is essential to prevention efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant awarded to Kristina M. Jackson (R01AA016838). Additional author support was provided by NIAAA to Samuel N. Meisel (F32AA028414) and Tim Janssen (K01AA026335) and Jacqueline Nesi was partially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH122669).

References

- Andrews JA, Hampson S, Peterson M (2011) Early adolescent cognitions as predictors of heavy alcohol use in high school. Addictive Behaviors 36:448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur M, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Pollard JA (1997) Student survey of risk and protective factors and prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. Questionnaire. (copia cedida por los autores). [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, McClelland DC (1977) Social learning theory, Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle SC, Labrie JW, Froidevaux NM, Witkovic YD (2016) Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors 57:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle SC, Smith DJ, Earle AM, Labrie JW (2018) What “likes” have got to do with it: Exposure to peers’ alcohol-related posts and perceptions of injunctive drinking norms. Journal of American College Health 66:252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ (2011) Beyond Homophily: A Decade of Advances in Understanding Peer Influence Processes. J Res Adolesc 21:166–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Nguyen EP, Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss M, Bierut LJ, Moreno MA (2016) Young Adults’ Exposure to Alcohol- and Marijuana-Related Content on Twitter. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 77:349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ (2004) Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annu Rev Psychol 55:591–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, Reno RR (1991) A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior, in Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 24, Advances in experimental social psychology, pp 201–234, Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Read JP, Wieczorek WF, Eiden RD, Lengua LJ, Hawk LW Jr., Trucco EM, Lopez-Vergara HI (2017) Cognitive appraisals of alcohol use in early adolescence: Psychosocial predictors and reciprocal associations with alcohol use. J Early Adolesc 37:525–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, DiBello AM, Meisel MK, Ott MQ, Kenney SR, Clark MA, Barnett NP (2019) Do misperceptions of peer drinking influence personal drinking behavior? Results from a complete social network of first-year college students. Psychology of addictive behaviors 33:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis BL, Lookatch SJ, Ramo DE, McKay JR, Feinn RS, Kranzler HR (2018) Meta-Analysis of the Association of Alcohol-Related Social Media Use with Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42:978–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JP, Christie NC, Lee D, Saba S, Ring C, Boyle S, Pedersen ER, LaBrie J (2021) Temporal, Sex-Specific, Social Media-Based Alcohol Influences during the Transition to College. Subst Use Misuse 56:1208–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JP, Pedersen ER, Tucker JS, Dunbar MS, Seelam R, Shih R, D’Amico EJ (2019) Long-term Associations Between Substance Use-Related Media Exposure, Descriptive Norms, and Alcohol Use from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 48:1311–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA (2015) Stand-Alone Personalized Normative Feedback for College Student Drinkers: A Meta-Analytic Review, 2004 to 2014. PLoS One 10:e0139518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Esp S, Hausheer R (2015) Parental consent procedures: Impact on response rates and nonresponse bias. Journal of Substance Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing S, Bryan AD, Dash GF, Lovejoy TI, Borsari B, Schmiege SJ (2021) Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing for alcohol and cannabis use within a predominantly Hispanic adolescent sample. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frissell KC, McCarthy DM, D’Amico EJ, Metrik J, Ellingstad TP, Brown SA (2004) Impact of consent procedures on reported levels of adolescent alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 18:307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galla BM, Choukas-Bradley S, Fiore HM, Esposito MV (2021) Values-Alignment Messaging Boosts Adolescents’ Motivation to Control Social Media Use. Child development 92:1717–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geber S, Frey T, Friemel TN (2021) Social Media Use in the Context of Drinking Onset: The Mutual Influences of Social Media Effects and Selectivity. J Health Commun 26:566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Stock ML, Pomery EA (2008) A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Developmental Review 28:29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Trudeau L, Vande Lune LS, Buunk B (2002) Inhibitory effects of drinker and nondrinker prototypes on adolescent alcohol consumption. Health Psychology 21:601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geusens F, Beullens K (2016) The association between social networking sites and alcohol abuse among belgian adolescents. Journal of media psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks H, Van Den Putte B, Gebhardt WA, Moreno MA (2018) Social Drinking on Social Media: Content Analysis of the Social Aspects of Alcohol-Related Posts on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Medical Internet Research 20:e226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks H, Wilmsen D, van Dalen W, Gebhardt WA (2020) Picture Me Drinking: Alcohol-Related Posts by Instagram Influencers Popular Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Frontiers in Psychology 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman J (1976) The incorrect use of Chi-square analysis for paired data. Clinical and experimental immunology 24:227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, Fujimoto K, Pentz MA, Jordan-Marsh M, Valente TW (2014) Peer Influences: The Impact of Online and Offline Friendship Networks on Adolescent Smoking and Alcohol Use. Journal of Adolescent Health 54:508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Marceau K, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Rogers ML, Hayes KL (2021) Trajectories of early alcohol use milestones: Interrelations among initiation and progression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 45:2294–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Throrton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier K (2018) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, Benson JW (2012) Improving media message interpretation processing skills to promote healthy decision making about substance use: the effects of the middle school media ready curriculum. Journal of health communication 17:546–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Kaysen DL, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Lewis MA, Dillworth T, Montoya HD, Neighbors C (2009) Evaluating level of specificity of normative referents in relation to personal drinking behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement:115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Litt DM, King KM, Fairlie AM, Waldron KA, Garcia TA, LoParco C, Lee CM (2020) Examining the ecological validity of the prototype willingness model for adolescent and young adult alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 34:293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt DM, Astorga A, Tate K, Thompson EL, Lewis MA (2021) Disentangling Associations Between Frequency of Specific Social Networking Site Platform Use, Normative Discrepancies, and Alcohol Use Among Adolescents and Underage Young Adults. Health Behavior Research 4. [Google Scholar]

- Litt DM, Stock ML (2011) Adolescent alcohol-related risk cognitions: the roles of social norms and social networking sites. Psychol Addict Behav 25:708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Cox RB Jr, Washburn IJ, Croff JM, Crethar HC (2017) The effects of requiring parental consent for research on adolescents’ risk behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health 61:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Wen Z (2004) In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural equation modeling 11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel SN, Colder CR (2015) Social goals and grade as moderators of social normative influences on adolescent alcohol use. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research 39:2455–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel SN, Colder CR (2020) Adolescent Social Norms and Alcohol Use: Separating Between- and Within-Person Associations to Test Reciprocal Determinism. J Res Adolesc 30 Suppl 2:499–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman M, Hendriks H, van den Putte B (2020) How Viewing Alcohol Posts of Friends on Social Networking Sites Influences Predictors of Alcohol Use. J Health Commun 25:522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J (2016) Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The Univesity of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME (2021) Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2020: Volume I, Secondary school students, in Series Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2020: Volume I, Secondary school students, pp 571, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Cox ED, Young HN, Haaland W (2015) Underage College Students’ Alcohol Displays on Facebook and Real-Time Alcohol Behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health 56:646–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Whitehill JM (2014) Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol research: current reviews 36:91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MJ (2018) Transformation of Adolescent Peer Relations in the Social Media Context: Part 1-A Theoretical Framework and Application to Dyadic Peer Relationships. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 21:267–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, Rothenberg WA, Hussong AM, Jackson KM (2017) Friends’ Alcohol-Related Social Networking Site Activity Predicts Escalations in Adolescent Drinking: Mediation by Peer Norms. J Adolesc Health 60:641–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Fat L, Cable N, Kelly Y (2021) Associations between social media usage and alcohol use among youths and young adults: findings from Understanding Society. Addiction 116:2995–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wray-Lake L, Finlay AK, Maggs JL (2010) The Long Arm of Expectancies: Adolescent Alcohol Expectancies Predict Adult Alcohol Use. Alcohol and Alcoholism 45:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Herzog TA, Laestadius L, Buente W, Kawamoto CT, Lee H-R, Unger JB (2018) Social media e-cigarette exposure and e-cigarette expectancies and use among young adults. Addictive Behaviors 78:51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny SB, Jason LA, Schoeny ME, Townsend SM, Curie CJ (2001) Do participation rates change when active consent procedures replace passive consent. Evaluation review 25:567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, Peebles A, Mann S, Robb MB (2022) Common Sense census: Media use by teens and teens, 2021., in Series Common Sense census: Media use by teens and teens, 2021., Common Sense., San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, Robb MB (2021) The role of media during the pandemic: Connection, creativity, and learning for tweens and teens., in Series The role of media during the pandemic: Connection, creativity, and learning for tweens and teens., San Francisco, CA: Common Sense. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas NL, Sherrit L, Harris S, Knight JR (2008) The role of parental consent in adolescent substance use research. Journal of Adolescent Health 42:192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Martino SC, Ellickson PL, Collins RL, McCaffrey D (2005) Measuring Developmental Changes in Alcohol Expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 19:217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman EP, Smith AR, Silva K, Icenogle G, Duell N, Chein J, Steinberg L (2016) The dual systems model: Review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Dev Cogn Neurosci 17:103–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit K, Voogt C, Hiemstra M, Kleinjan M, Otten R, Kuntsche E (2018) Development of alcohol expectancies and early alcohol use in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 60:136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB (2007) Using multivariate statistics, Pearson Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Ward RM, Dumas TM, Lewis MA, Litt DM (2022) Likelihood of Posting Alcohol-Related Content on Social Networking Sites–Measurement Development and Initial Validation. Substance Use & Misuse:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH (2004) Do Parents Still Matter? Parent and Peer Influences on Alcohol Involvement Among Recent High School Graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 18:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.