Gastroparesis is a challenging gastrointestinal condition to manage in clinical practice. The recently published American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Guideline on Gastroparesis highlighted major features regarding risk factors, diagnosis, and management of this disorder.(1) However, given the complexities of patient care, guideline recommendations can seem impractical or difficult to enact. Therefore, we illustrate the recommendations provided in the guideline through discussion of three vignettes below that illustrate different diagnostic and treatment approaches for gastroparesis (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1.

How recommendations were used in each clinical report

| Guideline recommendations | VIGNETTE 1 | VIGNETTE 2 | VIGNETTE 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | |||

| Optimal glucose control in DG | Followed by endocrinologist Great glucose and HbA1c control. | Not DG | Not DG |

| Diagnosis | |||

| GE scintigraphy is the standard test (solid meal; duration of ≥3h test) | Delayed at 4h | Delayed at 4h | Delayed at 4h |

| Radiopaque testing not suggested | Not needed clinically | ||

| Wireless motility capsule testing and Stable isotope (13C-spirulina) breath test - alternative tests | |||

| Management | |||

| Small particle diet | First line treatment | ||

| Pharmacologic treatment to improve GE and symptoms – considering benefits and risks in DG and IG | Off label pyridostigmine | ||

| Metoclopramide over no treatment | Modest efficacy | Modest efficacy | Extrapyramidal side effects |

| Domperidone over no treatment | Not tried since not easily prescribed | ||

| 5-HT4 agonists over no treatment | Not possible since no such drug available for GP in USA | ||

| Antiemetic agents | Only for symptom relief as needed | ||

| Central neuromodulators not recommended | Not used in accordance with guideline recommendations | ||

| Ghrelin agonists not recommended | |||

| Haloperidol not recommended | |||

| Non-pharmacological management | |||

| Gastric electric stimulation | Not performed | Option not selected in post-fundoplication GP | Not performed |

| Acupuncture not recommended | Not performed in accordance with guideline | ||

| Herbal therapies not recommended | |||

| EndoFLIP evaluation | Not performed | During G-POEM procedure | |

| Intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin not recommended | Performed previously No clinical response | Not performed in accordance with guideline | Not performed as recommended |

| Refractory GP: pyloromyotomy over no treatment | Not needed | 1) Laparoscopic pyloroplasty performed elsewhere – no clinical response 2) Plan to undergo a Y-en-Roux gastric bypass |

Outcome still being assessed |

Abbreviations: DG, diabetic gastroparesis; GE, gastric emptying; GP, gastroparesis; G-POEM, gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; IG, idiopathic gastroparesis

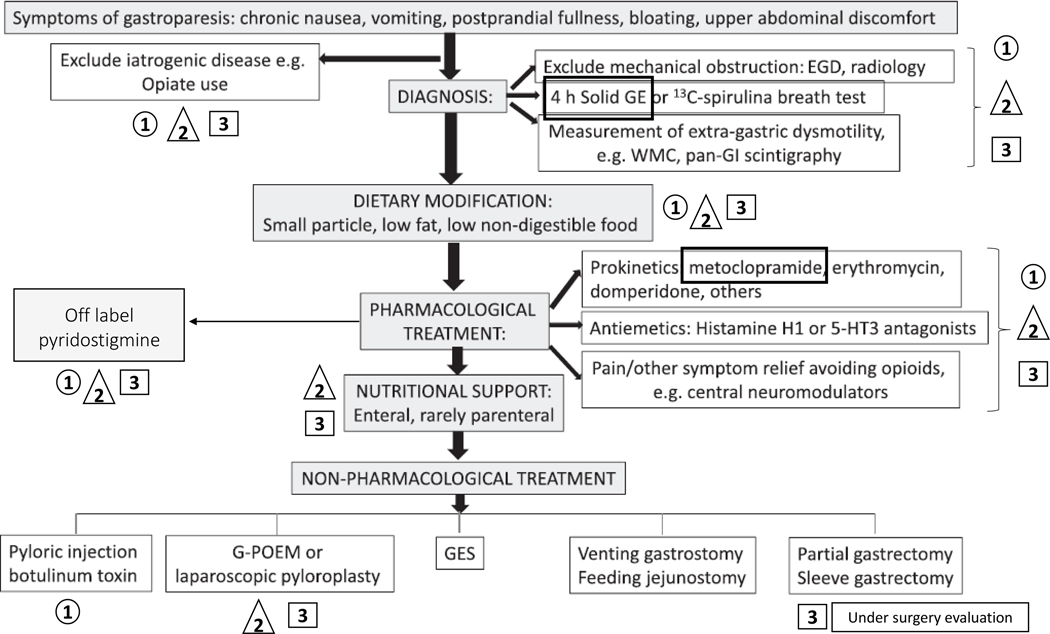

Figure 1. Algorithm from ACG Guideline on Gastroparesis (ref. 1) adapted with permission to illustrate the diagnose and management of all three vignettes.

Symbols: 1 – Vignette 1; 2 – Vignette 2; 3 – Vignette 3.

Abbreviations: ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; ECG, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GE, gastric emptying; GI, gastrointestinal; G-POEM, gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy; WC, wireless motility capsule.

VIGNETTE 1: Diabetic Gastroparesis

A 76-year-old man previously underwent vagotomy and pyloroplasty for peptic ulcer disease 30 years ago. He had no post-surgical gastrointestinal symptoms. Subsequently, he had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus for 12 years and, for 2 years, he experienced recurrent nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, and abdominal distension. There was no evidence of structural abnormalities or obstruction on abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan and upper endoscopy (EGD), except for the presence of a gastric bezoar. Prior to being seen at our center, he had failed trials of metoclopramide, domperidone, and botulinum toxin injection to the pylorus.

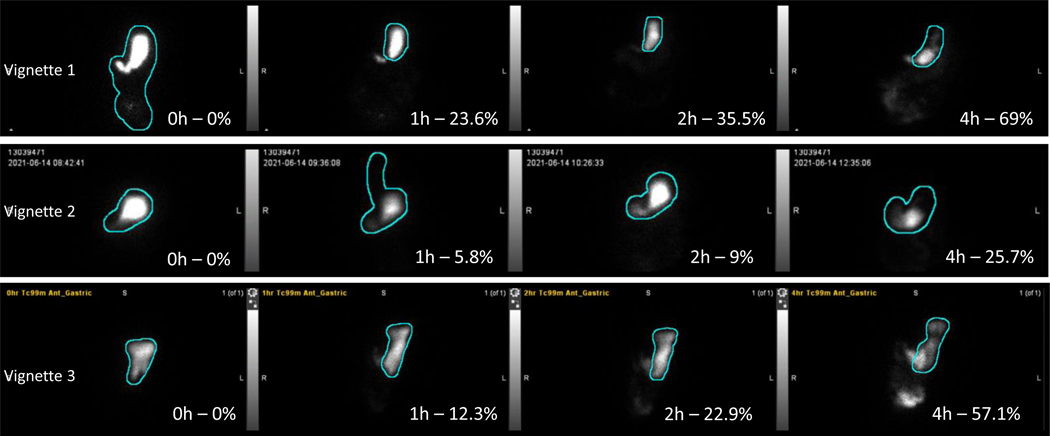

Scintigraphic 4-hour gastric emptying (GE) study of a solid 300kcal, 30% fat meal showed that 36% of the meal emptied at 2 hours and 69% at 4 hours (Figure 2). Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed absence of sinus arrhythmia (Figure 3), suggestive of cardiovagal denervation. These data are consistent with moderately severe diabetic gastroparesis (DG). We reinforced dietary instructions to use low residue meals, and cooking and homogenizing vegetables and fruits. An endocrinologist enhanced optimization of glycemia. The patient experienced an excellent clinical response with pyridostigmine 60 mg before each meal and remains well during 15 months’ follow-up.

Figure 2.

Anterior images of gastric emptying scintigraphy studies from all three cases reported, showing the percentage (%) emptied from the stomach at 0h,1h,2h and 4 hours after ingestion of the 300kcal, 30% fat solid meal containing Technetium-99 (99Tc).

Figure 3.

Absence of sinus arrythmia shown by the consistent R-R intervals that vary by less than 0.12 seconds (three small squares in the EKG) - indicative of cardiovagal neuropathy

Comment

There is a complex relationship between glycemic control and GE. Experimentally, acute hyperglycemia (>250mg/dL) retards GE. In long-term follow up of patients with type 1 diabetes, baseline HbA1c and overall glycemic control shown by HbA1c trends over years were the most accurate predictors of delay in GE (2). Satisfactory glucose control is recommended to better regulate gastric transit and symptoms.(3) Ideally in DG, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists should be avoided due to their effect on delaying GE.(4) The goal of the initial gastroparesis evaluation is to rule out mechanical obstruction. Although suggestive, the presence of retained gastric food on EGD is not confirmatory of gastroparesis as demonstrated in 2,991 patients without structural abnormalities who underwent EGD and GE by scintigraphy. The positive predictive value of retained food relative to delayed GE in the absence of an underlying risk factor was only 32%.(5) It is essential to exclude confounding medications and to perform a validated assessment of GE.

First-line pharmacological approaches to gastroparesis are metoclopramide and domperidone, where available. Both agents have predominantly dopaminergic antiemetic effects that may not provide sufficient prokinetic action on the stomach. Prokinetic efficacy may vary among patients, possibly related to the underlying physiopathology of DG (e.g., extrinsic versus enteric neuropathy). Evidence of cardiovagal denervation can be used in this case as a surrogate for abdominal vagal dysfunction as previously reported.(6) Pyridostigmine is an orally active acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that enhances the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, in the enteric neurons to stimulate gastrointestinal smooth muscle (7) and GI transit in patients with diabetes.(8)

Although botulinum toxin injection to the pylorus is not recommended in the guideline, a recent multicenter study from France showed that evidence of decreased pyloric distensibility may impact outcomes in response to pyloric botulinum toxin injection.(9) If prokinetic and antiemetic medications fail, non-pharmacological approaches to gastroparesis to consider are gastric electric stimulation and pyloromyotomy.

VIGNETTE 2: Post-surgical Gastroparesis

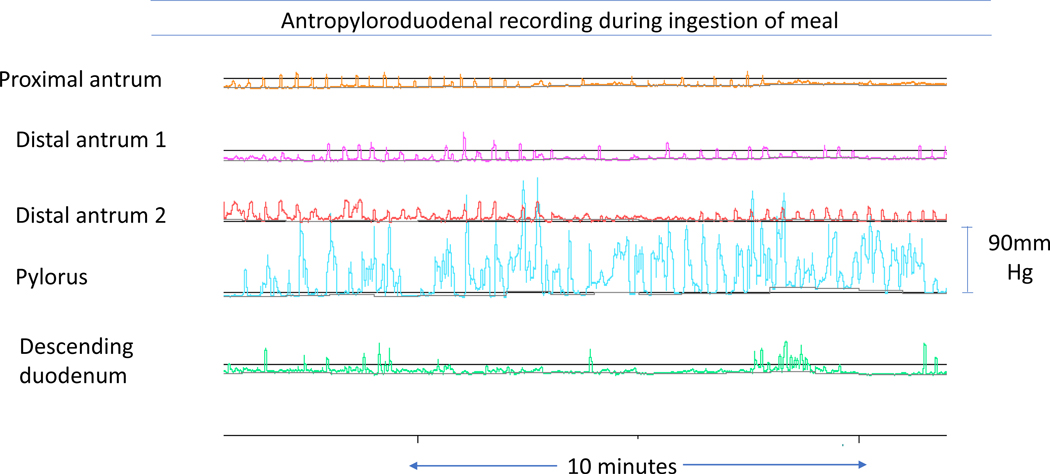

A 61-year-old woman had undergone Nissen fundoplication and Collis gastroplasty for gastroesophageal reflux disease 20 and 15 years, respectively, prior to presentation to our clinic. More recently, she underwent laparoscopic pyloroplasty elsewhere for treatment of gastroparesis and chronic abdominal pain, without clinical response. Abdominal CT and EGD were unremarkable. Dietary management and prokinetic therapy failed to ensure adequate nutritional intake; thus, she required enteral nutrition via jejunal feeding tube. After six months, she presented to our clinic with malnutrition and severe epigastric pain. GE scintigraphy confirmed severe gastroparesis with only 26% emptied after 4 hours (Figure 2). On gastroduodenal manometry, antral hypomotility with transient pyloric contraction was observed during meal ingestion (Figure 4), but there was no consistent pylorospasm identified postprandially.

Figure 4.

Gastroduodenal manometry from vignette 2 showing intraprandial antral hypomotility (normal three per minute low amplitude contraction) with transient pylorospasm

Comment

This patient has post-surgical gastroparesis and is now presenting with pain as her main symptom. Despite evidence of partial improvement in upper abdominal pain using central neuromodulators for functional dyspepsia, the improvement is usually restricted to those with normal gastric emptying, not to those with delayed GE.(10) One large, placebo-controlled trial of nortriptyline in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis showed no benefit, but the trial did not include post-surgical gastroparesis.(11) It is important to emphasize that opioids should be avoided for multiple reasons, including delaying GE. The only efficacious prokinetic for post-surgical gastroparesis is erythromycin.(12) Unfortunately, the response may be short lived as a result of down-regulation of the motilin receptor leading to tachyphylaxis.(13) Although overall management of gastroparesis relies predominantly on dietary modifications and pharmacotherapy, a recent systematic review showed that up to 20–30% of gastroparesis patients present with refractory disease despite these interventions.(14)

The patient illustrated represents the typical failure of medications and non-pharmacological intervention to the pylorus, requiring enteral nutrition to maintain her nutritional status. Gastroduodenal manometry confirmed antral dysmotility and, targeting only the pylorus may be insufficient to achieve satisfactory long-term outcomes. Thus, surgical treatment including gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is often required. Our patient was referred for RYGB as the next step in her treatment. Significant improvements in vomiting and abdominal pain have been documented one year after the procedure.(15)

VIGNETTE 3: Idiopathic Gastroparesis

A 24-year-old man without underlying comorbidities presented with food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss over the last two years. After extensive investigation elsewhere, the only abnormal finding was delayed GE on scintigraphy, suggestive of severe idiopathic gastroparesis. He was unable to tolerate metoclopramide and antiemetics due to side effects and became dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) over the past 18 months. Repeat scintigraphic GE with the 300kcal meal showed less than 60% emptied after 4 hours (Figure 2). An autonomic reflex screen showed no signs of vagal, sympathetic adrenergic, or sympathetic cholinergic neuropathy. An unsatisfactory clinical response with prokinetic therapy, including pyridostigmine, led to gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM). The patient continues rehabilitation with the nutrition team and continues using the prokinetic agent to support oral intake.

Comment

Two major concerns in patients with gastroparesis are nutritional status and weight loss. The first step to manage gastroparesis is dietary modification including use of small-particle, low-fat, and low-fiber diet along with adequate hydration.(16) Gastroparesis patients with severe malnutrition (weight loss greater than 10% within 6 months of diagnosis), nutrient deficiencies, or frequent hospitalizations may require enteral or, rarely, parenteral nutrition to maintain their nutritional status.(14, 17, 18) This young patient with severe idiopathic gastroparesis failed pharmacological therapy and required TPN. Management of refractory gastroparesis includes surgical options such as G-POEM. Based on open-label studies, G-POEM decreases the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index, both in short- and long-term follow-up. The first sham-controlled study showed improved gastric symptoms after 6 months of follow-up, particularly in patients with diabetic gastroparesis.(19) Adding measurements of pyloric diameter and distensibility (with EndoFLIP) prior to the pyloric intervention may predict response to treatment.(20) Long-term follow-up of this patient should include a multidisciplinary team - gastroenterology, endoscopy, and nutrition.

CONCLUSION

Table 1 summarizes the points of agreement or discrepancy between the guideline recommendations and the clinical management of all patients. The key messages with the above vignettes are highlighted in Table 2. Despite challenges, following the evidence-based recommendations provided by the guideline should aid in the management of gastroparesis by improving symptoms and quality of life for this population. Nevertheless, as acknowledged in the new guideline (1), it is necessary to recognize the limitations of guideline recommendations on pharmacotherapies in view of the dearth of FDA-approved therapies for gastroparesis in the United States and the FDA-recommended prescription for only 3 months for the only currently approved medication, metoclopramide.

Table 2.

Key points of guideline recommendations highlighted in these clinical vignettes

| Exclude mechanical obstruction prior to diagnosis |

| Retained gastric food in esophagogastroduodenoscopy should not be diagnostic of gastroparesis. - When clinically suspected an appropriate diagnostic test must be performed |

| Small particle, low-fiber and low-fat diet is recommended to all patients; fibers ideally cooked and blenderized. |

| Nutritional status and weight should be always evaluated. |

| If oral intake is not available, enteral or rarely parenteral nutrition should be considered. |

| Pharmacological approach is limited – metoclopramide as first-line prokinetic therapy |

| Non-pharmacological therapeutic options must be taken into consideration when available - Gastric electric stimulation and interventions targeting the pylorus |

| Management of gastroparesis is suggested to be with a multidisciplinary team, especially in refractory patients. -- Gastroenterology, Endoscopy and Nutrition team |

| Gastric surgery can be considered a treatment option when all other approved therapies failed. |

Acknowledgment:

The authors thank Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for secretarial assistance.

Funding:

Michael Camilleri receives funding for research on gastroparesis from National Institutes of Health (R01-DK122280 and R01-DK125680)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Michael Camilleri has consulted for AEON Pharma, Zealand Biopharma, Aditum Bio, Takeda, and Aclipse Therapeutics regarding the topic of gastroparesis.

The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Gabriela Piovezani Ramos, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Ryan J. Law, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Michael Camilleri, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Camilleri M, Kuo B, Nguyen L, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117:1197–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharucha AE, Batey-Schaefer B, Cleary PA, et al. Delayed Gastric Emptying Is Associated With Early and Long-term Hyperglycemia in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Gastroenterology 2015;149:330–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Kudva YC, Prichard DO. Diabetic Gastroparesis. Endocr Rev 2019;40:1318–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maselli DB, Camilleri M. Effects of GLP-1 and Its Analogs on Gastric Physiology in Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021;1307:171–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi D, Choi C, League J, et al. Food Residue During Esophagogastroduodenoscopy Is Commonly Encountered and Is Not Pathognomonic of Delayed Gastric Emptying. Dig Dis Sci 2021;66:3951–3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buysschaert M, Donckier J, Dive A, et al. Gastric acid and pancreatic polypeptide responses to sham feeding are impaired in diabetic subjects with autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes 1985;34:1181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehndiratta MM, Pandey S, Kuntzer T. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD006986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharucha AE, Low P, Camilleri M, et al. A randomised controlled study of the effect of cholinesterase inhibition on colon function in patients with diabetes mellitus and constipation. Gut 2013;62:708–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desprez C, Melchior C, Wuestenberghs F, et al. Pyloric distensibility measurement predicts symptomatic response to intrapyloric botulinum toxin injection. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:754–760 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Saito YA, et al. Effect of Amitriptyline and Escitalopram on Functional Dyspepsia: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Study. Gastroenterology 2015;149:340–9 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:2640–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burt M, Scott A, Williard WC, et al. Erythromycin stimulates gastric emptying after esophagectomy with gastric replacement: a randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;111:649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thielemans L, Depoortere I, Perret J, et al. Desensitization of the human motilin receptor by motilides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005;313:1397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonseca Mora MC, Milla Matute CA, Aleman R, et al. Medical and surgical management of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2021;17:799–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moszkowicz D, Mariano G, Soliman H, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as a salvage solution for severe and refractory gastroparesis in malnourished patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;18:577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olausson EA, Storsrud S, Grundin H, et al. A small particle size diet reduces upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:375–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:18–37; quiz 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Z, Rodriguez J, McMichael J, et al. Surgical treatment of medically refractory gastroparesis in the morbidly obese. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinek J, Hustak R, Mares J, et al. Endoscopic pyloromyotomy for the treatment of severe and refractory gastroparesis: a pilot, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Gut 2022. Apr 25;gutjnl-2022–326904. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-326904. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vosoughi K, Ichkhanian Y, Jacques J, et al. Role of endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe in predicting the outcome of gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91:1289–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]