Abstract

As Lewis a (Lea) and Lewis b (Leb) blood group antigens are isoforms of Lewis x (Lex) and Lewis y (Ley) and are expressed in the gastric mucosa, we evaluated whether the patterns of expression of Lex and Ley on Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides reflected those of host expression of Lea and Leb. When 79 patients (secretors and nonsecretors) were examined for concordance between bacterial and host Le expression, no association was found (χ2 = 5.734, 3 df, P = 0.125), nor was there a significant difference between the amount of Lex or Ley expressed on isolates from ulcer and chronic gastritis patients (P > 0.05). Also, the effect of host and bacterial expression of Le antigens on bacterial colonization and the observed inflammatory response was assessed. In ulcer patients, Lex expression was significantly related to neutrophil infiltration (rs = 0.481, P = 0.024), whereas in chronic gastritis patients significant relationships were found between Lex expression and H. pylori colonization density (rs = 0.296, P = 0.03), neutrophil infiltrate (rs = 0.409, P = 0.001), and lymphocyte infiltrate (rs = 0.389, P = 0.002). Furthermore, bacterial Ley expression was related to neutrophil (rs = 0.271, P = 0.033) and lymphocyte (rs = 0.277, P = 0.029) infiltrates. Thus, although no evidence of concordance was found between bacterial and host expression of Le determinants, these antigens may be crucial for bacterial colonization, and the ensuing inflammatory response appears, at least in part, to be influenced by Le antigens.

Helicobacter pylori is a prevalent pathogen of humans, and chronic infection of the gastric mucosa by the bacterium results in gastritis, peptic ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma (4). Persistence of H. pylori infection appears critical for the development of disease and may be facilitated by the expression of host antigens on the bacterium (17). Like the cell envelopes of other gram-negative bacteria, that of H. pylori contains lipopolysaccharides (LPSs). The low immunological activities of H. pylori LPSs, compared with those of enterobacterial LPSs, have been documented and, by inducing a low response, may prolong H. pylori infection longer than would occur with a more aggressive pathogen (15). The O-specific chain of the LPS of H. pylori has been found to express blood group antigens, predominantly of the type 2 blood group determinants Lewis x (Lex) and Lewis y (Ley) (17, 21, 25). Since these blood group antigens are present in the gastric mucosa of normal individuals (20), bacterial expression of Lewis (Le) antigens may camouflage the bacterium or otherwise aid initial colonization (16, 17) and, in chronic H. pylori infection, could be implicated in the induction of autoreactive antibodies in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-associated atrophic gastritis (2, 17), although this has not been unequivocally established (1).

The Le blood group antigen system composed of type 1 antigens, Lea and Leb, and type 2 antigens, Lex and Ley, is biochemically related to the ABO blood groups, and Lewis blood typing can identify both the Le antigen phenotype and secretor status of most people (6). Leb is the predominant blood group antigen expressed on epithelial cell surfaces and red cells of secretors (6, 11), whereas Lea is expressed by nonsecretors, although some secretors have been found to express Lea in variable amounts on their epithelial cells (19). Persons homozygous recessive for the Le gene may be secretors or nonsecretors, and although elucidation of their phenotype requires salivary testing, in general, these individuals are 80% secretors and 20% nonsecretors (6, 11). Expression of both type 1 and type 2 Le antigens on the gastric mucosa has been described elsewhere (11, 14, 20). Surface and foveolar epithelia coexpress either Lea and Lex in Le(a+,b−) individuals or Leb and Ley in Le(a−,b+) individuals, whereas glandular epithelium lacks type 1 antigens (Lea and Leb) and expresses Lex and Ley irrespective of the secretor phenotype. Consequently, a correlation between Le expression by H. pylori and that of the host has been suggested (26), but this has been disputed (22). In the present study, as type 1 Le determinants (Lea and Leb) are isoforms of type 2 determinants (Lex and Ley), we evaluated the expression of type 2 antigenic determinants on LPSs of H. pylori isolates from an unselected patient cohort, examined the prevalence of other blood group determinants on LPSs of these isolates, and evaluated whether the patterns of expression of Lex and Ley antigens on LPSs were similar to those of host type 1 Le antigen expression when determined by red cell secretor phenotype. As previous studies have suggested that Lex and Ley antigen expression may be pivotal in counterbalancing some proinflammatory characteristics of H. pylori (25, 26) and bacterial colonization, and the ensuing inflammatory response may be influenced at least in part by host expression of ABO and Lea blood group antigens (8), the effect of host and bacterial expression of Le antigens on bacterial colonization and the observed inflammatory response within the gastric mucosa were assessed.

Subjects were recruited from a group of 207 persons attending the open-access endoscopy service at University College Hospital, Galway, Ireland, and included 120 men and 87 women (mean age, 54 years; range, 13 to 90 years). Persons who had received antibiotics, H2 receptor antagonists, or proton pump inhibitors during the prior 4 weeks were excluded. All patients were Irish, and all were Caucasian. During upper endoscopy, three gastric antral biopsy specimens were obtained from similar topographical sites from within 3 cm of the pylorus and processed as described previously (8). One of the antral biopsy specimens was cultured for H. pylori, and confirmatory biochemical and microscopic tests were performed (24). Stock cultures were maintained at −70°C in horse serum supplemented with 20% glycerol. The second biopsy specimen was smeared on a glass slide and examined for H. pylori by a Giemsa stain. Sections of the third biopsy specimen embedded in paraffin wax were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain for light microscopy as described previously (8) and assessed subjectively by one blinded histopathologist for H. pylori density. Sections were graded 0 to 3, corresponding respectively to absent, scant, moderate, and heavy bacterial colonization. Severity and activity of gastritis in the same specimens were also graded 0 to 3, according to the criteria described previously (8).

Blood (10 ml) was collected into tubes containing EDTA and clot activator at the time of endoscopy from a single venipuncture site immediately prior to the administration of sedation. Antibodies (immunoglobulin G [IgG]) against H. pylori were measured in patient sera by a qualitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a commercially available kit (HM-CAP; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. H. pylori infection was defined as being present if culture alone or any combination of two other tests was positive, whereas H. pylori infection was defined as absent if all specimens were negative or if serological analysis alone was positive (8).

Host Le antigen phenotypes were determined with a macroscopic tube agglutination technique on washed red cells, within 24 h of collection, by using commercially available murine anti-Lea and anti-Leb blood grouping reagents (Bioscot Laboratories, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For determination of H. pylori blood group antigen phenotype, isolates were grown on blood agar for 48 h, harvested, washed twice in 0.18% NaCl, and centrifuged (2,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min), and the pellet was suspended in 0.15 M NaCl containing 15% glycerol. Subsequently, an ELISA with whole bacterial cells (25) was used as described previously (12) to determine the reaction of anti-Lewis antigen (Signet Laboratories, Dedham, Mass.) and blood group monoclonal antibodies (MAbs; Bioscot Laboratories) with the whole cells. The specificities of the antibodies in the assay were validated by their ability to recognize synthetic Le antigens, Ley (Isosep AB, Tulinge, Sweden), and Lex, Lea, Leb, sialyl-Lex, and H type 1 antigen (Dextra Laboratories, Reading, United Kingdom) as well as the LPSs of other H. pylori strains of known structure (12). In addition to controls without primary or secondary antibody, wells coated with Escherichia coli J5 were included in each assay as negative controls. The optical density (OD) values, measured at 492 nm, were considered positive for the presence of blood group antigens if greater than 0.3 OD units, since nonspecific binding never exceeded this value. Assays were repeated in triplicate.

Proteinase K-treated whole-cell extracts of H. pylori strains were prepared (9), and samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a 15% polyacrylamide separating gel, a 5% stacking gel, and a constant current of 35 mA for 1 h (24). After sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, LPS was detected by silver staining, or separated components were electroblotted onto nylon membranes (0.22-μm pore size; Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) (23, 24). Blood group determinants were detected by incubation with MAbs against anti-Le antigen or blood group MAbs as first antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG or IgM coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) as second antibody (12).

Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test for 2 × 2 tables (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]), chi-square (χ2) testing, and the Mann-Whitney U test (significance at 5% level, two-tailed P) for comparing unpaired data, and correlations were performed using either Pearson's product moment correlation or Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (rs) where appropriate.

Of 207 patients who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, 92 were infected with H. pylori, and of these, 8 were excluded, as their H. pylori isolate could not be regenerated from stock cultures. The remaining 84 patients included 49 men and 35 women (mean age, 51.2 years; range, 17 to 90 years), of whom 58 (69%) were secretors [Le(a−,b+)], 21 (25%) were nonsecretors [Le(a+,b−)], and 5 (6%) had the recessive [Le(a−,b−)] phenotype. Of these 84 patients, 78 (93%) had endoscopically visible disease, 12 patients (14%) showed duodenal ulceration, 10 (12%) had gastric ulceration in conjunction with antral gastritis, and 56 (67%) had endoscopic evidence of gastritis, whereas 6 (7%) had normal endoscopic findings but had histological evidence of gastritis. No patient showed endoscopic or histological evidence of atrophic gastritis, whereas intestinal metaplasia was identified histologically in two patients.

Eighty-eight percent (74 of 84) of H. pylori isolates had type 2 Le determinants, Lex, Ley, or a combination of Lex and Ley detectable on their LPS, as ascertained by ELISA. This included 4 strains (5%) with the Lex+,Ley− phenotype, 23 strains (27%) with the Lex−,Ley+ phenotype, and 47 strains (56%) that expressed both Lex and Ley. Ten isolates (12%) had no evidence of either Lex or Ley expression on their LPS, and of these isolates, one expressed Lea and a second expressed Leb. Three isolates coexpressed Lea with Lex and Ley, whereas five isolates coexpressed Leb with both Lex and Ley. The H type 1 precursor saccharide was identified on two isolates with Lex and Ley, and one isolate was identified by ELISA as having four blood group determinants (Lea, Leb, Lex, and Ley). Sialyl-Lex was not identified on any isolate by either ELISA or immunoblotting. Because of the finding of blood group A determinant on the LPS of Helicobacter mustelae (18), we also examined all 84 isolates for the presence of blood groups A and B using ELISA. One isolate was identified as having blood group A-like antigen coexpressed with both Lex and Ley, but blood group B antigenic determinant was not identified on any isolate. The presence of blood group antigenic determinants on LPS was confirmed, with a concordance between results of 97%, when proteinase K-treated whole-cell extracts of H. pylori isolates were immunoblotted and high-molecular-weight immunoreactive bands were observed identical to those described previously (15, 24). Furthermore, since isolates lacking an O chain would fail to be typeable (15, 21), isolates which were nontypeable by both ELISA and immunoblotting were confirmed as possessing an O chain by silver staining of LPS electrophoretic gels (data not shown).

There was no statistically significant difference between the mean OD values of Lex and Ley expression (0.518 ± 0.095 versus 0.707 ± 0.105, respectively) on the LPS of H. pylori isolates from Le(a+,b−) hosts (P = 0.161), nor was there a significant difference (P > 0.05) between expression of Lex on H. pylori strains from Le(a+,b−) and Le(a−,b+) hosts or Ley expression on strains from Le(a+,b−) and Le(a−,b+) hosts. The mean OD value of Ley expression was significantly greater (P < 0.001) than that of Lex on H. pylori strains isolated from patients of the secretor phenotype (0.906 ± 0.061 versus 0.464 ± 0.060, respectively). Although the mean OD value of bacterial Ley expression was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than that of Lex in isolates from five patients with the recessive Le phenotype (0.72 ± 0.3 versus 0.08 ± 0.08, respectively), this group was excluded from further analysis in keeping with the literature (3, 8, 10, 13), because they may be secretors or nonsecretors, which is indeterminable without salivary testing. Furthermore, OD values of Ley expression obtained from all 84 isolates which were tested were consistently higher than those observed for Lex expression (mean, 0.845 ± 0.053 and 0.455 ± 0.048, respectively). When 79 patients (secretors and nonsecretors) were examined for concordance between distribution of Le determinants on LPS and host Le phenotype, i.e., whether strains expressing Lex infected patients of Le(a+,b−) phenotype (nonsecretors) and strains expressing Ley infected patients of Le(a−,b+) phenotype (secretors), no association was found (χ2 = 5.734, 3 df, P = 0.125).

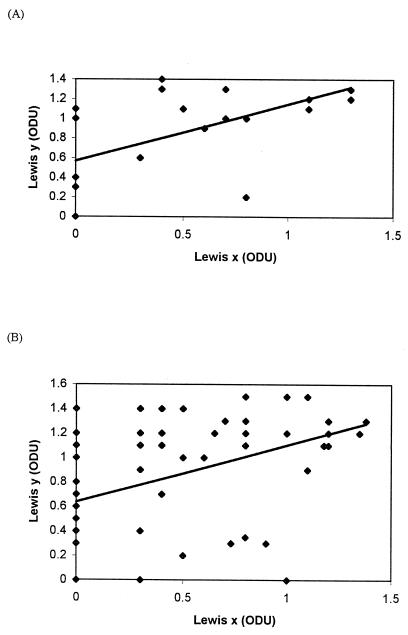

Of 84 patients, 22 (26%) had evidence of either gastric or duodenal ulceration. Isolates cultured from ulcer patients were no more likely to express Lex than those from chronic gastritis patients, 14 of 22 (64%) and 32 of 62 (52%), respectively (χ2 = 0.524, P = 0.469). A similar pattern was evident in Ley expression with 18 of 22 (82%) isolates from ulcer patients expressing Ley compared with 48 of 62 (77%) isolates from chronic gastritis patients (χ2 = 0.016, P = 0.896). There was no difference in the distribution of type 2 Le phenotypes between ulcer and nonulcer strains (χ2 = 1.305, 3 df, P = 0.727). Quantitatively, there was no significant difference between the OD values of Lex expression or Ley expression on isolates from ulcer and chronic gastritis patients, 0.486 ± 0.097 versus 0.444 ± 0.056 (P = 0.705) and 0.85 ± 0.101 versus 0.839 ± 0.063 (P = 0.898), respectively. Using Pearson's product moment correlation, a positive correlation was found between expression of Lex and Ley (r = 0.549, P = 0.008, 95% CI = 0.166 to 0.788 and r = 0.438, P = 0.0003, 95% CI = 0.214 to 0.619) for both ulcer and chronic gastritis strains, respectively (Fig. 1), and when this was calculated from all 84 isolates from ulcer and chronic gastritis patients (r = 0.456, 95% CI = 0.267 to 0.610, P < 0.0001).

FIG. 1.

Correlation between expression of Lex and Ley blood group antigens on the LPSs of H. pylori isolated from patients with ulcers (A) and those with chronic gastritis (B). ODU, OD units.

Although median Lex and Ley expression levels were similar in strains isolated from ulcer and gastritis patients, as expected and consistent with our previous observations (8), significant differences between grades of lymphocyte (P = 0.016) and neutrophil (P = 0.026) infiltrate in ulcer and chronic gastritis patients were observed (1.772 ± 0.112 versus 1.451 ± 0.071 and 1.272 ± 0.149 versus 0.935 ± 0.079, respectively). H. pylori colonization density was not significantly higher (P = 0.106) among patients with ulcer disease than among patients with gastritis alone (1.863 ± 0.165 versus 1.564 ± 0.081, respectively). In addition, we examined the relationships between Lex and Ley expression on H. pylori LPS and bacterial colonization density and neutrophil and lymphocyte inflammatory responses using Spearman's correlation coefficient (Table 1). In patients with ulcers, Lex expression was related to neutrophil infiltration (P = 0.024), but there was no association of expression of Lex or Ley with bacterial colonization density or lymphocyte infiltration. In patients with chronic gastritis, however, significant relationships were found between Lex expression and H. pylori colonization density (P = 0.03), lymphocyte infiltrate (P = 0.002), and neutrophil infiltrate (P = 0.0001). In addition, significant relationships between bacterial Ley expression and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrates were observed, but these associations were not as strong as those observed for Lex.

TABLE 1.

Correlation of quantitative expression of Lex and Ley on H. pylori isolates with bacterial colonization density and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrates in ulcer and nonulcer patients

| Characteristics for comparison | Ulcer patients

|

Chronic gastritis patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | P | 95% CI | rs | P | 95% CI | |

| Lex expression vs: | ||||||

| H. pylori colonization density | 0.321 | 0.143 | −0.11–0.65 | 0.296 | 0.03 | 0.021–0.486 |

| Lymphocyte infiltrate | 0.095 | 0.668 | −0.34–0.49 | 0.389 | 0.002 | 0.157–0.582 |

| Neutrophil infiltrate | 0.481 | 0.024 | 0.075–0.75 | 0.409 | 0.001 | 0.177–0.597 |

| Ley expression vs: | ||||||

| H. pylori colonization density | −0.148 | 0.507 | −0.563–0.291 | 0.234 | 0.06 | −0.016–0.475 |

| Lymphocyte infiltrate | 0.076 | 0.731 | −0.356–0.482 | 0.277 | 0.029 | 0.029–0.492 |

| Neutrophil infiltrate | 0.108 | 0.628 | −0.328–0.506 | 0.271 | 0.033 | 0.023–0.487 |

As shown in Table 2, nonsecretors with ulcer disease had higher mean grades of lymphocyte infiltration (P = 0.011) and neutrophil infiltration (P = 0.012) than did secretors. No significant difference between expression of Lex or Ley among secretors and nonsecretors with ulcer disease or chronic gastritis was observed. Mean grades of both neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrates were significantly greater in nonsecretors than in secretors with chronic gastritis (P = 0.038 and 0.028, respectively). No significant difference was found in bacterial colonization density between secretors and nonsecretors.

TABLE 2.

Relationship of disease pathology and host Le phenotype with the quantitative expression of type 2 Le antigens on H. pylori isolates, colonization density, and inflammatory response in 79 patientsa

| Infection characteristic | Value for ulcer disease patients

|

Value for chronic gastritis patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsecretors | Secretors | P | Nonsecretors | Secretors | P | |

| Lex (OD) | 0.56 ± 0.148 | 0.46 ± 0.137 | 0.585 | 0.48 ± 0.127 | 0.465 ± 0.067 | 0.839 |

| Ley (OD) | 0.74 ± 0.16 | 1.02 ± 0.108 | 0.116 | 0.681 ± 0.145 | 0.878 ± 0.071 | 0.240 |

| H. pylori colonization density | 2.1 ± 0.233 | 1.54 ± 0.207 | 0.132 | 1.636 ± 0.152 | 1.574 ± 0.099 | 0.638 |

| Lymphocyte grade | 2.1 ± 0.10 | 1.45 ± 0.157 | 0.011 | 1.818 ± 0.181 | 1.361 ± 0.071 | 0.028 |

| Neutrophil grade | 1.6 ± 0.221 | 0.909 ± 0.162 | 0.012 | 1.363 ± 0.243 | 0.851 ± 0.091 | 0.038 |

Values for nonsecretors and secretors are shown as means ± standard errors of the means.

Similar to previous studies which have detected Le antigens in H. pylori at a consistent rate of between 80 and 90% (17, 21, 25), 88% of clinical isolates expressed type 1 or type 2 Le antigens in this study. Also, using ELISA we identified blood group A-like antigen on a single H. pylori isolate in ELISA, which, until now, has been defined only on H. mustelae LPS, where it has been implicated in the pathogenesis of gastritis in ferrets (18). Nevertheless, chemical studies are required to confirm the presence of the blood group A structure on H. pylori LPS. Moreover, the finding of thus-far-nontypeable isolates with intact O-specific chains suggests that it is imperative to establish the structural nature of the O chains of these isolates. Some of the previous studies of Le expression have not clarified the exact proportions of strains from ulcer and nonulcer disease (21), whereas others have favored using strains from predominantly ulcer-related disease (25, 26). For this reason, we chose a study group of unselected patients who sequentially attended an open-access endoscopy service, as this potentially would provide a more representative patient sample, reflecting the spectrum of H. pylori-mediated gastroduodenal disease in clinical practice. Hence, a high prevalence of chronic gastritis was observed in this study. In addition, given the homogeneity of the population from which this study sample was drawn, confounding variables such as race could be excluded, as other studies have included patients from up to 19 different countries (25, 26).

A previous study suggested that, in mimicking host gastric epithelium, not only do H. pylori isolates express Lex and Ley, but their relative proportion of expression corresponds to the host Le(a+,b−) and Le(a−,b+) blood group phenotypes (26). Using the same techniques, we did not find data to support this hypothesis with our test population. A problem which exists when attempting to correlate bacterial expression of Lex and Ley with host expression of Lea and Leb concerns the ELISA utilized (25, 26), in which bacterial Le expression is related to protein content rather than to carbohydrate content. In contrast, typing of host Le phenotype as determined by red cell hemagglutination is based on the detection of carbohydrate determinants in an all-or-none phenomenon. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with those of an immunohistological study which did not establish a correlation between Le antigen expression on H. pylori and gastric epithelial cells (22). However, only 24 patients were examined in the latter study, and the authors urged that further investigations were required before a specific cause-and-effect relationship between H. pylori and host expression of Le antigens was accepted.

In the present study population, 6% of individuals had the recessive Le phenotype [Le(a−,b−)], which is consistent with the prevalence of this phenotype among other homogeneous European populations (3). Because patients of this phenotype may be secretors or nonsecretors, these patients were excluded from further analysis (3, 8, 10, 13). Subsequently, we analyzed host and bacterial Le expression of the remaining 79 patients but found no evidence for concordance between the bacterium and its host, in contrast to a previous study (26). However, the latter study found an inordinately high prevalence of patients (17 of 66 [26%]) with the Le(a−,b−) phenotype, failed to exclude them as a group, and did not consider their effect on the deduced correlations had they been distributed to their true secretor phenotype by salivary testing.

Ulcer risk has been associated with strain characteristics such as cagA (4, 16). It was previously suggested that isolates from patients with ulcer disease were more likely to express Le antigens than those from persons without ulcers (25) and that expression of Lex and Ley antigens exists to counterbalance the enhanced proinflammatory activity of cagA+ isolates (25, 26). However, in this study, patients with ulcer-related disease were found to be no more likely to express Lex or Ley on their bacterial isolates than were patients with antral gastritis, nor were they more likely to have significantly increased levels of Lex or Ley when examined quantitatively by ELISA. Moreover, expression of Lex was found to correlate with Ley antigen expression, independent of whether strains were isolated from ulcer or nonulcer patients. For this same study population, no statistically significant relationship (P > 0.05) was found between the occurrence and level of Lex or Ley and cagA status (A. P. Moran and M. A. Heneghan, unpublished data). Consistent with this, a similar study of another distinct group of Irish H. pylori isolates found no association (12), and a study of Canadian H. pylori isolates found no direct relation between bacterial Le expression, cagA, and Le antigen expression on gastric cells (22).

Histological assessment of the distribution and density of H. pylori in the stomach has suggested a greater colonization of the gastric antrum in duodenal ulcer patients than in nonulcer patients and an increased severity and activity of antral gastritis in ulcer patients related to H. pylori infection density (5). Consistent with the hypothesis that blood group phenotype and colonization density may influence the inflammatory response, and in keeping with our previous results (8), both acute and chronic inflammatory cells were present in greater quantity in the antral mucosa of nonsecretors. Furthermore, Lex was associated with enhanced colonization density and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrates in the gastric antrum in patients with chronic gastritis, whereas an association was detected with lymphocyte infiltrates in patients with ulcer disease but not with grade of neutrophil infiltration. Whether increased numbers of patients with ulcer-related disease would have resulted in different results remains uncertain. Thus, in contrast but in addition to a role of Le antigens in aiding initial infection by H. pylori, expression of these antigens in chronic H. pylori infection may contribute to the development of pathology. Guruge et al. (7) described a transgenic mouse model expressing Leb in the murine gastric mucosa which showed that epithelial attachment by H. pylori altered the outcome of infection and that H. pylori infection induced autoreactive ani-Lex antibodies and gastritis. Whether the association between Lex expression by H. pylori and the inflammatory response is a reflection of the role of Lex in adhesion (16, 22) and the subsequent infiltration by neutrophils and lymphocytes, or a consequence of anti-Lex antibodies activating neutrophils (2), is the subject of further investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelmelk B J, Faller G, Claeys D, Kirchner T, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E. Bugs on trial: the case of Helicobacter pylori and autoimmunity. Immunol Today. 1998;19:296–299. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelmelk B J, Simoons-Smit I, Negrini R, Moran A P, Aspinall G O, Forte J G, de Vries T, Quan H, Verboom T, Maaskant J G, Ghiara P, Kuipers E J, Bloemena E, Tadema T M, Townsend R R, Tyagarajan K, Crothers J M, Jr, Montiero M A, Savio A, de Graaff J. Potential role of molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide and host Lewis blood group antigens in autoimmunity. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2031–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2031-2040.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickey W, Collins J S A, Watson R G P, Sloan J M, Porter K G. Secretor status and Helicobacter pylori infection are independent risk factors for gastroduodenal disease. Gut. 1993;34:351–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn B E, Cohen H, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eidt S, Stolte M. Differences between Helicobacter associated gastritis in patients with duodenal ulcer, pyloric ulcers, gastric ulcers and gastritis without ulcer. In: Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit H, editors. Helicobacter pylori gastritis and peptic ulcer. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 228–236. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green C. The ABO, Lewis and related blood group antigens: a review of structure and biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1989;47:321–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guruge J L, Falk P G, Lorenz R G, Dans M, Wirth H-P, Blaser M J, Berg D E, Gordon J I. Epithelial attachment alters the outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3925–3930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heneghan M A, Moran A P, Feeley K M, Goulding J, Egan E L, Connolly C E, McCarthy C F. Effect of host Lewis and ABO blood group antigen phenotype on Helicobacter pylori colonisation density and the consequent inflammatory response. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;20:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klaamas K, Kurtenov O, Ellamaa M, Wadström T. The Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in blood donors is related to Lewis (a,b) histo-blood group phenotype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:367–370. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd K O. Blood group antigens as markers for normal differentiation and malignant change in human tissues. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:129–139. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/87.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall D G, Hynes S O, Coleman D C, O'Morain C A, Smyth C J, Moran A P. Lack of a relationship between Lewis antigen expression and cagA, CagA, vacA and VacA status of Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;24:79–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mentis A, Blackwell C C, Weir D M, Spiladis C, Dialianas A, Skandalis N. ABO blood group, secretor status and detection of Helicobacter pylori among patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;106:221–229. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800048366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mollicone R, Bara J, LePendu J, Oriol R. Immunohistologic pattern of type 1 (Lea, Leb) and type 2 (X, Y, H) blood group-related antigens in the human pyloric and duodenal mucosa. Lab Investig. 1985;53:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran A P. Cell surface characteristics of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;10:271–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran A P. Pathogenic properties of Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(Suppl. 215):22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran A P, Appelmelk B J, Aspinall G O. Molecular mimicry of host structures by lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter and Helicobacter spp.: implications in pathogenesis. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Cróinín T, Clyne M, Drumm B. Molecular mimicry of ferret epithelial blood group antigen A by Helicobacter mustelae. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:690–696. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saadi A T, Blackwell C C, Raza M W, James V S, Stewart J, Elton R A, Weir D M. Factors enhancing adherence of toxigenic Staphylococcus aureus to epithelial cells and their possible role in sudden infant death syndrome. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:507–517. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakamoto J, Wantanabe T, Tokumara T, Takagi H, Nakazato H, Lloyd K O. Expression of Lewisa, Lewisb, Lewisx, Lewisy, sialyl-Lewisa and sialyl-Lewisx blood group antigens in human gastric carcinoma and in normal gastric tissue. Cancer Res. 1989;49:745–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simoons-Smit I M, Appelmelk B J, Verboom T, Negrini R, Penner J L, Aspinall G O, Moran A P, She F F, Shi B, Rudnica W, Savio A, Graaff J. Typing of Helicobacter pylori with monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens in lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2196–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2196-2200.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor D E, Rasko D A, Sherburne R, Clinton H, Jewell L D. Lack of correlation between Lewis antigen expression by Helicobacter pylori and gastric epithelial cells in infected patients. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh E J, Moran A P. Influence of medium composition on the growth and antigen expression of Helicobacter pylori. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:67–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirth H P, Yang M, Karita M, Blaser M J. Expression of the human cell surface glycoconjugates Lewis x and Lewis y by Helicobacter pylori isolates is related to cagA status. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4598–4605. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4598-4605.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirth H P, Yang M, Peek R J, Jr, Tham K T, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori Lewis expression is related to the host Lewis phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1091–1098. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]