Abstract

Previous studies have reported that phagocytosed Bordetella pertussis survives in human neutrophils. This issue has been reexamined. Opsonized or unopsonized bacteria expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were incubated with adherent human neutrophils. Phagocytosis was quantified by fluorescence microscopy, and the viability of phagocytosed bacteria was determined by colony counts following treatment with polymyxin B to kill extracellular bacteria. Only 1 to 2% of the phagocytosed bacteria remained viable. Opsonization with heat-inactivated immune serum reduced the amount of attachment and phagocytosis of the bacteria but did not alter survival rates. In contrast to previous reports, these data suggest that phagocytosed B. pertussis bacteria are killed by human neutrophils.

A decade ago it was reported that members of the genus Bordetella are capable of surviving inside mammalian cells following phagocytosis (6, 7). These studies were among the first to examine the intracellular fate of bacterial species that were considered to be extracellular pathogens. As more bacteria were examined, it became clear that Bordetella is not particularly unique in this regard. Many other organisms not considered to be intracellular pathogens, for example, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus (13), were also found to be capable of transient survival inside mammalian cells. In addition, there is a clear distinction between the behavior of Bordetella pertussis and that of Bordetella bronchiseptica. While neither species appears to be capable of intracellular replication, B. bronchiseptica remains viable for days within mammalian cells while B. pertussis is capable only of short-term survival (3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17, 23). In one study, fewer than 100 of more than 100,000 B. pertussis cells internalized by macrophages survived for 24 h, a rate not too different from that of E. coli DH5α (3). Some studies have even suggested that the continued presence of viable B. pertussis organisms induces apoptosis and kills mammalian cells (12, 14), making it unlikely that the bacteria could persist as intracellular pathogens. Only a few reports have suggested that B. pertussis persists, and under some conditions replicates, in an intracellular compartment (11, 24, 25). The mammalian cells examined in these reports were professional phagocytes, macrophages, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (or neutrophils), the cells one would predict to be most proficient at bacterial killing.

A clinical study is commonly cited to support the role of intracellular survival in macrophages during human pertussis (4). B. pertussis was found to be associated with alveolar macrophages isolated from children with AIDS and pertussis, but the authors noted that their methods could not distinguish intracellular from extracellular bacteria. In addition, they failed to recover viable organisms from the patients and reported that several of the patients were being treated with antibiotics, which could account for the failure to culture the bacteria. This study contributes little insight into this problem.

In light of the conflicting reports regarding intracellular survival of B. pertussis in professional phagocytes, we have reexamined this issue. Previous studies have reported only the numbers of surviving bacteria; the percentages of internalized organisms that actually survive have never been reported. As a consequence, it has not been possible to ascertain whether intracellular survival is a high-probability or a low-probability event. A high survival rate might suggest that the bacteria have mechanisms to ensure viability following phagocytosis, while the significance of a low survival rate in the pathogenesis of B. pertussis is unclear.

We have developed a technique to distinguish extracellular bacteria from phagocytosed, intracellular bacteria (26). B. pertussis cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) appear green by fluorescence microscopy. When ethidium bromide is added, extracellular bacteria take up the stain and appear orange by fluorescence microscopy; however, intracellular bacteria resist staining with ethidium bromide and remain green (26). This technique allows one to directly determine the number of phagocytosed bacteria. Addition of polymyxin B (an antibiotic that cannot penetrate mammalian cells) kills extracellular bacteria, allowing one to quantify intracellular survival. In this study we combined these techniques. Few, if any, B. pertussis cells appeared to be capable of surviving in human neutrophils.

The virulent B. pertussis strain BP338 was transformed (26) with plasmid CW504, which directs high-level expression of GFP from a constitutive B. pertussis promoter. This plasmid was derived from pGB5P1 (26) by the addition of a 3-kb ClaI fragment from pUW2138 (8) containing the origin of transfer for P plasmids and a gentamicin resistance marker.

Phagocytosis and opsonization were performed as previously described (26). Briefly, BP338(pCW504) was grown overnight on Bordet-Gengou agar (BGA) and harvested to contain approximately 3 × 106 bacteria in 30 μl of HBSA (Hanks' buffer supplemented with 0.25% bovine serum albumin and 20 mM HEPES buffer). To opsonize the bacteria, 30 μl of suspended bacteria was incubated with 30 μl of heat-inactivated human immune serum for 15 min at 37°C in 5% CO2, while unopsonized controls were incubated with 30 μl of HBSA. The volume was increased to 400 μl with HBSA, and the bacteria were added to the neutrophils. The neutrophils were isolated from human blood and quantified using a hemocytometer, and 5 × 105 neutrophils were added to 24-well microtiter plates as previously described (26). Phagocytosis was allowed to occur for 1 h, the supernatant was aspirated, and 1 ml of ethidium bromide at 50 μg/ml was added. Extracellular bacteria take up the ethidium bromide and stain orange, while intracellular bacteria resist staining with ethidium bromide and appear green by fluorescence microscopy (26).

In a previous study (26), using a multiplicity of infection of 6, about 15% of the bacteria attached to the neutrophils but only about 2% of the bacteria were phagocytosed. These numbers seemed quite low, and we reasoned that the organisms in suspension were not making contact with the immobilized neutrophils. B. pertussis cells are smaller than E. coli cells and settle out of suspension very slowly. In one experiment, B. pertussis cells were suspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.825, and 1 h later the optical density was nearly unchanged (0.815), confirming that very little settling had occurred. To facilitate contact, the B. pertussis cultures were centrifuged onto the neutrophils for 5 min at 640 × g and the phagocytosis assay was allowed to occur. One hundred neutrophils were counted for each duplicate sample, and the experiment was repeated five times.

To calculate the total number of intracellular bacteria, the number of intracellular (green) bacteria per neutrophil determined by microscopy was multiplied by the total number of neutrophils plated, or 5 × 105. The average for all five experiments was 1.49 intracellular bacteria per neutrophil, for a total of 7.4 × 105 bacteria phagocytosed (Fig. 1). This value is about 40% of the 1.8 × 106 bacteria in the initial inoculum. Since centrifugation improved the efficiency of phagocytosis, it was used throughout this study.

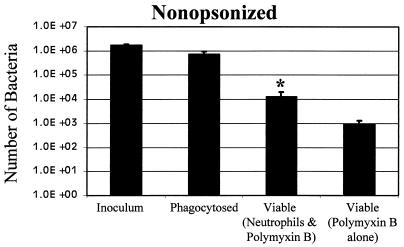

FIG. 1.

Phagocytosis and survival of B. pertussis. Bacterial suspensions were added to adherent human neutrophils or to empty wells in a 24-well microtiter plate and incubated for 1 h. Polymyxin B was added for 1 h where indicated. Bacterial CFU were determined by plating serial dilutions. The number of bacteria phagocytosed was determined by fluorescence microscopy. Definitions: Inoculum, the number of CFU after 2 h without neutrophils; Phagocytosed, the number of green bacteria associated with human neutrophils; Viable (Neutrophils & Polymyxin B), CFU recovered after incubation with neutrophils followed by polymyxin B; Viable (Polymyxin B alone), CFU after incubation without neutrophils followed by polymyxin B. Data were analyzed by the Student t test. Each bar depicts the mean ± standard error of the mean. ∗, significant difference from the number of phagocytosed bacteria.

In previous studies, polymyxin B has been shown to kill extracellular bacteria but not intracellular bacteria (10, 15). To determine the optimal incubation times for killing, 4 μl of polymyxin B sulfate (Sigma) at 10 mg/ml was added to 3 × 106 bacteria in 400 μl of HBSA in 24-well microtiter plates for a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Control wells received no antibiotics. The bacteria were incubated for 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0 h, transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 34,540 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed with 1 ml of HBSA, centrifuged, and suspended in 1 ml of water. Tenfold serial dilutions were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7.4, and 0.1 ml was plated on BGA plates. The plates were incubated for 4 days and colonies were counted. More bacterial survival was observed at 0.5 h, but similar values were observed at 1 and 3 h. A standard 1-h incubation was adopted, and of the 1.8 × 106 bacteria added to the wells less than 1,000, or 0.05%, survived treatment with polymyxin B (Fig. 1).

To ensure that polymyxin B was not toxic to the neutrophils, the viability of the neutrophils was determined by trypan blue exclusion. A total of 100 neutrophils were counted and >95% remained viable.

To determine the number of viable bacteria following phagocytosis by neutrophils, the wells containing bacteria and neutrophils were treated with polymyxin B as described above. The wells were aspirated and washed twice with HBSA to remove the polymyxin B. One milliliter of water was added to lyse the neutrophils, and the wells were scraped with a rubber policeman. In control experiments, lysis of the neutrophils was confirmed by trypan blue exclusion; few intact neutrophils were observed, and greater than 95% of those stained with trypan blue. Serial dilutions were performed and plated. Only 1.3 × 104 bacteria were recovered (Fig. 1), that is, 1.7% of the 7.4 × 105 bacteria that were phagocytosed remained viable after phagocytosis, and this difference was statistically significant as determined by the Student t test (P < 0.007). There was no statistically significant difference P = 0.10) between the number of viable bacteria incubated with neutrophils and polymyxin B and the number of viable bacteria incubated with polymyxin B alone (Fig. 1); therefore, it was not possible to determine whether any bacteria survived.

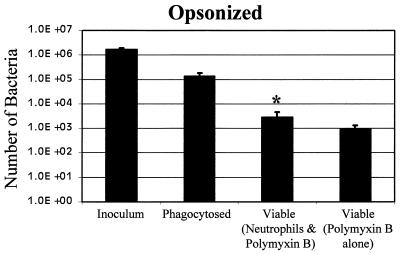

The role of opsonization with antibodies was also examined. A heat-inactivated human immune serum (#13) from an occupationally exposed laboratory worker was shown previously to lack complement activity but to possess functional antibodies (26, 27). Opsonization with this serum decreased the amount of bacterial attachment to neutrophils and also reduced the amount of phagocytosis (26), which could be a consequence of the reduction in attachment.

In this study, we observed 0.28 opsonized intracellular bacteria per neutrophil (Fig. 2); that is, only 8% were phagocytosed as opposed to 42% of the unopsonized bacteria (Fig. 1). This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.02). In spite of the reduced amount of phagocytosis, the fate of the opsonized bacteria was similar to the fate of the unopsonized bacteria. Only 2% of the opsonized bacteria that were phagocytosed remained viable (P < 0.03). The number of phagocytosed bacteria still viable after polymyxin B treatment was not significantly different from the number of bacteria treated with polymyxin B alone (P = 0.28).

FIG. 2.

Phagocytosis and survival of opsonized B. pertussis. Bacteria (30 μl) were incubated with 30 μl of human immune serum that had been heat inactivated to destroy complement activity but retained functional antibodies and were added to 24-well microtiter wells, as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

Early reports suggested that B. pertussis was capable of long-term survival and perhaps replication in professional phagocytes (11, 24, 25), but more recent reports have suggested B. pertussis is capable only of transient intracellular survival (3, 5, 13, 23). In the latter studies, antibiotics that cannot penetrate mammalian cells, such as gentamicin and polymyxin B, have been used to kill extracellular bacteria, while reports demonstrating long-term survival of B. pertussis did not use this methodology. In one study examining phagocytosis by macrophages, endogenous complement was used to kill extracellular B. pertussis (11). B. pertussis cells expressing the BrkA protein resist killing by complement (8). Human serum samples are highly variable, and only serum from an immune donor promotes efficient killing by complement (8, 9, 27). It was not reported whether serum from a single source was used throughout that study.

A few studies have examined survival of B. pertussis in neutrophils. In one study, association of B. pertussis with neutrophils was examined microscopically following Giemsa staining (24). Since this stain cannot distinguish intracellular bacteria from extracellular bacteria, the authors performed control experiments to determine whether the bacteria had been internalized. Bacteria were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), which stains the bacteria fluorescent green. Phagocytosis was allowed to occur, and ethidium bromide was added to differentiate extracellular bacteria from intracellular bacteria. The authors found that the majority of FITC-labeled bacteria stained green, suggesting that they were phagocytosed. However, we have shown that FITC labeling destroys the activity of the adenylate cyclase toxin (a potent inhibitor of phagocytosis), and in our study FITC-labeled, but not wild-type, bacteria were efficiently phagocytosed by neutrophils (26). It is likely that the results of the former authors are consistent with ours. The nonviable FITC-labeled bacteria were more efficiently phagocytosed than the unlabeled wild-type bacteria. Since antibiotics were not used to kill the extracellular bacteria, viable extracellular bacteria could have been recovered following incubation with neutrophils. An independent study reported nearly 100% survival of B. pertussis in neutrophils (25). Acridine orange was used to differentiate between viable and dead bacteria, and the authors cited a study stating that living organisms stain light orange to green while dead organisms stain bright orange; however, they did not present their own data to validate this assumption.

The belief that B. pertussis is capable of intracellular survival has led to suggestions for changes in pertussis vaccine strategies. Evidence from both animal and human studies suggests that a Th1 immune response may be more protective than a Th2 response (2, 18–20, 22), and it has even been suggested that a humoral immune response may not be needed for immunity to pertussis. While Th1 responses often prevail in infections by intracellular pathogens, the presence of a Th1 response cannot be used as proof that an intracellular infection has occurred, and a Th1 response is often the initial response to all infections (1, 21). Our studies suggest that phagocytosis of B. pertussis is accompanied by death of the bacteria, and one benefit of a Th1 immune response could come from activation of phagocytic defenses. It appears unlikely that other activities associated with the cell-mediated immune response, for example, the generation of CD8-positive cytotoxic T cells, would be needed, since phagocytes can kill B. pertussis on their own.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant RO1 AI38415 to A.A.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausiello C M, Urbani F, La Sala A, Lande R, Cassone A. Vaccine- and antigen-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine induction after primary vaccination of infants with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2168-2174.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banemann A, Gross R. Phase variation affects long-term survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in professional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3469–3473. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3469-3473.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberg K, Tannis G, Steiner P. Detection of Bordetella pertussis associated with the alveolar macrophages of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4715–4719. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4715-4719.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhatwal G S, Walker M J, Yan H, Timmis K N, Guzman C A. Temperature dependent expression of an acid phosphatase by Bordetella bronchiseptica: role in intracellular survival. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:257–264. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewanowich C A, Melton A R, Weiss A A, Sherburne R K, Peppler M S. Invasion of HeLa cells by virulent Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2698–2704. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2698-2704.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ewanowich C A, Sherburne R K, Man S F P, Peppler M S. Bordetella parapertussis invasion of HeLa 229 cells and human respiratory epithelial cells in primary culture. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1240–1247. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1240-1247.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez R C, Weiss A A. Cloning and sequencing of a Bordetella pertussis serum resistance locus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4727–4738. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4727-4738.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez R C, Weiss A A. Serum resistance in bvg-regulated mutants of Bordetella pertussis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forde C B, Parton R, Coote J G. Bioluminescence as a reporter for intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in murine phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3198–3207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3198-3207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman R L, Nordensson K, Wilson L, Akporiaye E T, Yocum D E. Uptake and intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4578–4585. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4578-4585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gueirard P, Druilhe A, Pretolani M, Guiso N. Role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin in alveolar macrophage apoptosis during Bordetella pertussis infection in vivo. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1718–1725. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1718-1725.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Bock M, Timmis K N. Invasion and intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5528–5537. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5528-5537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4064–4071. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4064-4071.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C K, Roberts A L, Finn T M, Knapp S, Mekalanos J J. A new assay for invasion of HeLa 299 cells by Bordetella pertussis: effects of inhibitors, phenotypic modulation, and genetic alterations. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2516–2522. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2516-2522.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masure H R. Modulation of adenylate cyclase toxin production as Bordetella pertussis enters human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6521–6525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masure H R. The adenylate cyclase toxin contributes to the survival of Bordetella pertussis within human macrophages. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:253–260. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills K H G, Barnard A, Watkins J, Redhead K. Cell-mediated immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of Th1 cells in bacterial clearance in a murine respiratory infection model. Infect Immun. 1993;61:399–410. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.399-410.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills K H G, Ryan M, Ryan E, Mahon B P. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:594–602. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.594-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redhead K, Watkins J, Barnard A, Mills K H G. Effective immunization against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in mice is dependent on induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3190–3198. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3190-3198.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romagnani S. Th1 and Th2 in human disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;80:225–235. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan M, Murphy G, Gothefors L, Nilsson L, Storsaeter J, Mills K H G. Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in children is associated with preferential activation of type 1 T helper cells. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1246–1250. doi: 10.1086/593682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schipper H, Krohne G F, Gross R. Epithelial cell invasion and survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3008–3011. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3008-3011.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steed L L, Setareh M, Friedman R L. Intracellular survival of virulent Bordetella pertussis in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:321–330. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torre D, Ferrario G, Bonetta G, Perversi L, Tambini R, Speranza F. Effects of recombinant human gamma interferon on intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human phagocytic cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;9:183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weingart C L, Broitman-Maduro G, Dean G, Newman S, Peppler M, Weiss A A. Fluorescent labels influence phagocytosis of Bordetella pertussis by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4264–4267. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4264-4267.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss A A, Mobberley P S, Fernandez R C, Mink C M. Characterization of human bactericidal antibodies to Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1424–1431. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1424-1431.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]