Abstract

Preoperative sleep loss can amplify post-operative mechanical hyperalgesia. However, the underlying mechanisms are still largely unknown. In the current study, rats were randomly allocated to a control group and an acute sleep deprivation (ASD) group which experienced 6 h ASD before surgery. Then the variations in cerebral function and activity were investigated with multi-modal techniques, such as nuclear magnetic resonance, functional magnetic resonance imaging, c-Fos immunofluorescence, and electrophysiology. The results indicated that ASD induced hyperalgesia, and the metabolic kinetics were remarkably decreased in the striatum and midbrain. The functional connectivity (FC) between the nucleus accumbens (NAc, a subregion of the ventral striatum) and the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vLPAG) was significantly reduced, and the c-Fos expression in the NAc and the vLPAG was suppressed. Furthermore, the electrophysiological recordings demonstrated that both the neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG, and the coherence of the NAc-vLPAG were suppressed in both resting and task states. This study showed that neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG were weakened and the FC between the NAc and the vLPAG was also suppressed in rats with ASD-induced hyperalgesia. This study highlights the importance of preoperative sleep management for surgical patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-022-00955-1.

Keywords: Acute sleep deprivation, Incisional pain, Nucleus accumbens, Periaqueductal gray, Functional connectivity

Introduction

Sleep is necessary for human existence and daily activities, and sleep loss is becoming one of the most serious public health problems worldwide. Human studies have demonstrated that sleep deprivation (SD) and disorders are very common in patients [1, 2]. In clinical settings, surgical patients who suffer from chronic psychological stress, such as insomnia and physical illness often exhibit pain hypersensitivity or pathological pain before the surgery [3, 4]. Meanwhile, in those patients who are physically and mentally healthy with normal preoperative pain perception, preoperative sleep disturbances, which may be caused by the surgical stress, the disease itself, disruptive environments (such as light and noise), or medical treatments [3], can amplify the experience of pain [3, 5–7]. This kind of preoperative sleep disturbance is very common in clinical settings, and constitutes partial but not total acute SD (ASD), which can cause hyperalgesia [8, 9]. However, the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown.

To investigate the underlying mechanism, a target brain region should be selected for further investigation. For example, preoperative 24-h SD induces pain hypersensitivity and increases the level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein in the region of the rostral ventromedial medulla [10]. Sleep-deprived rats show delayed postsurgical pain recovery and reduced levels of mu and kappa opioid receptors in the dorsal root ganglia and ipsilateral L4/5 spinal cord [3]. The adenosine A2A receptors in the median preoptic nucleus play a vital role in regulating sleep-pain interactions [5]. However, these studies directly chose a classic brain region related to sleep and pain, and information on the whole brain is lacking. Thus, it is essential to establish a proper technology for screening the major brain regions related to ASD-induced hyperalgesia at the whole-brain level.

Previous studies have reported some methods available to screen the brain regions related to ASD-induced hyperalgesia. For example, the expression of c-Fos protein has been used to identify neuronal activation in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) following rapid eye movement (REM)-SD [11]. A neuroimaging study found that some brain regions, such as the somatosensory cortex, striatum, insular cortex, and thalamus, are associated with pain modulation in sleep-deprived volunteers [12]. However, since these technologies only provide partial information, it is better to use multi-modal techniques to screen the major related brain regions.

Here, multi-modal technologies (from macroscopic to microscopic) were applied to screen for abnormal neuronal activity and identify target brain regions. As a unique and noninvasive method, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can be used to explore the role of neuronal activity along with the imbalance of cerebral energy metabolism among different brain regions. Moreover, resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) is a non-invasive method for investigating changes in the brain functional network and reflects the functional connectivity (FC) between different brain regions, which indirectly reflects the neuronal activity between different areas. The unique advantage of the resting-state FC (rsFC) is the ability to assess the effects of a condition of interest (e.g., SD) on the whole functional brain network without designing detailed tasks [13]. In addition, c-Fos is an activity-dependent protein, which is regarded as a biomarker for neuronal activation under a stimulated state [14]. Furthermore, local field potential (LFP) signals from electrophysiological recordings represent the sum of spontaneous synaptic activity near the electrode which could reflect neuronal activity [15]. Exploring the coherence between neuronal activities is essential for better understanding information processing across areas of the brain and investigating the connectivity between different regions. Thus, the current multi-modal technologies can provide objective and accurate information about brain regions related to sleep-pain interaction for further study.

The aim of this study was to screen the abnormal brain regions related to various cerebral functions and activities for hyperalgesia induced by preoperative ASD using multi-modal technologies (Fig. 1). Behavioral, metabolic, neuroimaging, biochemical, and electrophysiological methods were combined to thoroughly screen the major brain region related to ASD-induced hyperalgesia. Our study emphasizes the importance of preoperative sleep management for surgical patients and sheds light on the treatments of perioperative sleep disorders.

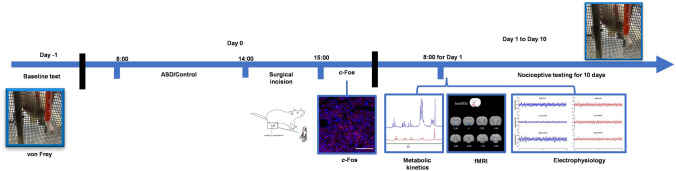

Fig. 1.

Timeline and design of the experiments. Schedule of the whole experimental procedure with multi-modal methods (nociceptive testing, NMR, fMRI, c-Fos expression, and electrophysiology). ASD, acute sleep deprivation; fMRI, functional; magnetic resonance imaging.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (WP2020–08087). Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–350 g were from the Hubei Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Wuhan, China) and kept in a specific pathogen-free animal facility. Rats were housed in plastic cages (three animals per cage) with free access to food and water in a climate-controlled room with a 12-h light-dark cycle (lights on from 08:00 to 20:00) at 25 ± 1 °C. Before experiments, rats were allowed a 7-day acclimation period, and all efforts were made to reduce animal suffering and decrease the number of animals used.

Preparation and Experimental Design

The animals were randomly divided into two groups: a control (Ctrl) group and an ASD group. The steps of the experimental procedures with multi-modal methods are illustrated in Fig. 1. First, nociceptive testing was applied to evaluate the mechanical nociceptive thresholds. Second, based on the results of nociceptive testing (P = 0.000017 at day 1, the most significantly different timepoint between the Ctrl and ASD groups), fMRI (n = 8/group) [16], NMR (n = 8/group) [17], and electrophysiology (n = 5/group) [18] were applied on the first day after surgery. Third, for c-Fos immunohistochemistry, rats were euthanized, and brains were extracted 2 h after the surgical incision.

ASD and the Incisional Pain Model

The wakefulness state for the ASD model was accomplished by gently tapping on the side of the cage or by tactile stimulation of the whiskers/tail with a pencil-sized paintbrush between 08:00 and 14:00 [5, 19–21]. Once a sleep attempt was observed, mild auditory and tactile stimulation were applied to keep the rats awake. Experimenters did not directly touch or stimulate the rats with their hands to reduce stress when they were awake.

The surgical procedure is performed according to previous studies [5, 22]. Briefly, all animals were anesthetized with 1.5%–2.0% isoflurane (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) in oxygen with an oxygenator (RWD Life Science) via a nose cone. Penicillin (Flocillin®, 30,000 IU) was injected into the triceps muscle. The plantar surface of either hind paw was sterilized with a 10% povidone-iodine solution, and the foot was placed through a hole in a sterile gauze. After gently pressing to stop bleeding, the skin was stitched with two sutures of 6–0 nylon and wiped with an antibiotic ointment containing polymyxin B, neomycin, and bacitracin. The wound was placed on the right paw, and the muscle origin and insertion were left intact to reduce suffering. After surgery, the rats were returned to their home cages. Recovery from postsurgical pain was defined as the postoperative day on which the group mechanical threshold was not significantly different from the baseline value.

Nociceptive Testing

Similar to humans, rats show a time-related hypersensitivity to wounds and the surrounding skin can be activated by movement or mechanical stimulation. As in other studies, mechanical hyperalgesia was examined using the von Frey test, measured as the threshold for paw withdrawal in grams [5, 19, 23, 24]. The mechanical thresholds of rats in the Ctrl and ASD groups were measured using this test. Rats were housed in individual Plexiglas testing chambers with a wire net floor on a von Frey mesh stand, and they were habituated to the chamber for 20–30 min before testing. A range of von Frey filaments (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 15 g bending force; Stoelting Wood Dale, IL, USA) was applied in ascending order to determine the mechanical paw withdraw threshold (PWT). In the incised (right) paw, the skin area medial to the caudal end of the wound was stimulated. This procedure was then repeated at the contralateral claw around the same area. The duration of each stimulus was ~5 s, or the paw was withdrawn. The interstimulus interval was a 60 s, and each filament was applied 5 times. The stimuli were repeated on the contralateral paw. Quick withdrawal or persistent flinching behavior was considered a positive response. The mechanical PWT was defined as the lowest force in g that responded to 3 of 5 responses.

Metabolic Kinetics Measurement

[1-13C Glucose] Infusion Techniques

To reduce the influence of endogenous unlabeled glucose, the rats were fasted overnight (15–18 h) but had free access to water before the experimental day [25, 26]. On the experimental day, the experiment started at 10:00., and every rat was initially anesthetized under ~ 4.0% isoflurane with oxygen, and anesthesia was maintained with ~ 1.5% isoflurane. An adequate anesthetized state was confirmed by a lack of response to a foot pinch. To test the level of blood glucose before infusion, two drops of blood (from the end of the tail with a needle pinch) were collected and tested with a glucose test paper (Yuyue, China). Next, one lateral tail vein was catheterized for infusion with [1–13C] glucose (Qingdao Tenglong Weibo Technology Co., Ltd, Qingdao, P.R. China) through PE50 tubing (Instech, PA, USA). The rats were returned to their home cages to recover for ~ 15 min, until they performed normal movements. Then, one side of a swivel (Instech, PA, USA) was connected to the tail vein infusion tube, and the other side was connected to an injection pump (Fusion100, Chemyx, TX, USA) through another PE50 tube. The whole infusion process was completed in 2 min at 400–600 µL/min (calculated from the animal weight) [27] through the tail vein, according to a previous infusion protocol [28, 29]. After another 20 min, all rats were sacrificed using the head-focused microwave irradiation method (1 KW, Tangshan Nanosource Microwave Thermal Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Hebei, PR China) to reduce the influence of post-mortem changes in brain metabolites [30]. About 2.0 mL of blood was collected from the inferior thoracic vena cava to measure the glucose level after infusion. Finally, the microwaved brains were collected and divided into 11 regions according to previous studies [28, 31, 32]: the frontal cortex (FRC), parietal cortex (PC), occipital cortex (OC), temporal cortex (TC), striatum (STR), hippocampus (HP), thalamus (THA), hypothalamus (HYP), midbrain (MID), medulla-pons (MED), and cerebellum (CE). The tissues were weighed and frozen at – 80 °C for further processing.

Metabolite Extracts

The metabolites in the brain sample were extracted following the methanol-ethanol extraction method [26, 33]. Briefly, HCl/methanol (80 µL, 0.1 mol/L) was added to the sample and homogenized with a Tissuelyser (Tissuelyser II, Qiagen, Germany) for 90 s at 20 Hz. Next, 400 µL ethanol (60%, vol/vol) was added, and the mixture was homogenized again under the first homogenization condition. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. Then, 1200 µL of 60% ethanol was used to repeat all the extraction steps, and this procedure was repeated twice. All the supernatants were collected together and gradually desiccated using a centrifugal drying apparatus (Thermo Scientific 2010, Germany) and a freezing vacuum dryer (Thermo Scientific). The dried products were re-dissolved in 600 µL of D2O buffered with 0.2 M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2). The solution was thoroughly mixed in a high-speed vortex and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15 min. Finally, the supernatant (530 μL) was collected and transferred to a 5-mm NMR tube for analysis.

NMR Study

The NMR spectra were randomly recorded at 298 K with a BrukerAvance III 500 MHz NMR vertical bore spectrometer (BrukerBiospin, Germany). The metabolite extract samples were measured using a POCE (proton observed carbon editing, 1H–13C-NMR) pulse sequence [34]. This method includes two spin-echo measurements, one representing the total metabolite concentrations (12C+13C) and the other representing the difference in the proton signals connected with 12C and 13C of the metabolites (12C−13C). This subtraction represented the concentrations of the 13C-label-related metabolites. The following parameters were set for the acquisition: number of scans, 64; repetition time, 20 s; sweep width, 10 kHz; acquisition data, 64 K; echo time, 8 ms.

fMRI Experiments

The procedures for the animal pre-experimental preparation are described in our previous study [35]. Briefly, the imaging experiments were carried out on a 7.0 T scanner with a 20 cm horizontal bore BioSpec 70/20 USR system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). The rat was first anesthetized with isoflurane (4%–5%) and placed in the imaging system under isoflurane (1%–1.5%) to maintain anesthesia. A heating pad was used to maintain body temperature. Finally, the position of the rat was adjusted to an optimal location with fixation under the stereotaxic ear bar and bite bar. Functional MRI data were collected with a multi-segment gradient echo planar sequence (TR, 1000 ms; TE, 14 ms; flip angle, ~ 45°; FOV, 20 × 20 mm2, spatial resolution, 0.31 × 0.31 × 1 mm3, 20 slices). In addition, a T2-weighted anatomical scan was collected using the same geometry as that of the fMRI scan 164 (TR, 5000 ms; TE, 12 ms; RARE factor, 8; matrix, 256 × 256; spatial resolution, 0.08 × 0.08 mm2).

Immunohistochemistry of c-Fos Expression

c-Fos, an activity-dependent protein, is regarded as a biomarker for neuronal activation. Neuronal activity can reach sufficient expression 2 h after surgical incision [36]. Thus, every rat was deeply anesthetized 2 h after surgical incision with an overdose of isoflurane and was perfused with sodium phosphate buffer (PBS) and then 4% paraformaldehyde. After that, the entire brain was removed from the skull and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the brain was placed in a fixation bath with 30% sucrose for three days. Coronal sections (40 µm) were cut on a cryostat microtome (NX50, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The sections were washed with PBS (three times, 7 min each). Then, the slides were blocked in PBS with 10% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at 37°C. Later, the slices were incubated with anti-c-Fos rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:1000; Cell Signaling, cat. no. 2250, RRID: AB_2247211) for 48 h at 4 °C. After three washes in PBS for 7 min each, the sections were incubated for 2 h in goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200) at room temperature. Afterward, the sections were stained with DAPI for 10 min and washed in PBS. Finally, the sections were scanned with a virtual microscopy slide scanning system (Olympus, VS 120, Tokyo, Japan), the regions of interest (ROIs) were selected, and c-Fos positive cells were counted using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

In vivo Electrophysiology

Electrode Implantation

Local field potentials (LFPs) were recorded following the protocols in the previous study [18]. Briefly, the rats (n = 5/group) were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p) and fixed to a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD, 68030, 68025). The skull was exposed, and a dental drill was used to perforate the targeted regions (left and right NAc: (in mm) 1.55 anterior to bregma, 1.55 lateral to midline, and 7.5 ventral from dura; left and right vLPAG: 7.8 posterior to bregma, 0.5 lateral to midline, and 5.8 ventral from dura). The reference electrode was a stainless steel screw fixed in the occipital crest. Electrodes made from tungsten wires were then implanted into the targeted areas to record LFPs. The rats were allowed to recover from the surgery for 7 days.

In vivo Electrophysiological Recordings

After the rats fully recovered from surgery, they were placed in a recording chamber and allowed to acclimate to the environment for 30 min. The recording apparatus was then connected to the implanted electrodes to record the LFPs of awake rats (resting-state LFP) without disturbance. The LFPs were amplified (2000×, Dagan, MN, USA) and sampled at 2 kHz using a 1401 acquisition interface and Spike2 software (CED, Cambridge, UK). As rats were used as experimental animals, to reduce noise during the LFP recording, they were lightly anesthetized under 1.0%–1.5% isoflurane and subjected to noxious stimulation (a 10 g von Frey filament) to record task-state LFP. The stimulation area was according to the protocol of nociceptive testing.

Data Analysis

To analyze the NMR spectrum, the commercial software Topspin 2.1 (Bruker Biospin, GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) was used to preliminarily convert the free induction decay (FID) signals of the spectra and adjust the phase and baseline. Then, the spectra were uploaded and analyzed using MatLab code in a home-made software NMRSpec [26, 33, 37], which provided the peak areas related to the metabolites and the 13C enrichment of various neurochemicals (freely available from the author on request: jie.wang@wipm.ac.cn).

The fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM 12, RRID: SCR_007037) in MatLab (R2018b, MathWorks Inc. 2018), including time division and rearrangement, head movement correction, smoothing, and spatial standardization. Subsequently, the extracranial part was removed, and the intracranial tissue was left using MRIcron (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricron). To analyze the rsfMRI, the preprocessed data were de-trended, filtered (0.01–0.1 Hz), and regressed with signals from the white matter and cerebrospinal fluid in the DPABI software in MatLab. According to the Sigma rat brain atlas [38], 59 ROIs were automatically recognized and the selected ROIs were illustrated in suppelemental materials (Table S2) [38]. Afterward, the time courses of the mean values of ROIs were extracted. To reveal the brain network, rsFC in the whole brain was obtained using Pearson correlation analysis among the 59 ROIs. To analyze the ROI-based whole brain network in different groups, an ROI mask of the left/right NAc region was manually obtained via MRIcron software, and the voxel-wise level Pearson correlation map in the whole brain was generated from average time series of the selected ROI via the 3dNetCorr function of AFNI. A voxel-wise t-test was applied to compare the difference of correlation maps between the ASD and Ctrl groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 (uncorrected) was applied, and only clusters with size >40 were taken into account. Given the fMRI method was just used to roughly screen the sub-regions related to ASD-induced hyperalgesia, we used the uncorrected P value (P < 0.05) to roughly screen the sub-region in this work and next used c-Fos expression and electrophysiology to verify the fMRI results.

The coherences of different LFPs between different brain regions were preprocessed using Spike2 software, as in a previous study [18]. For the resting-state LFP, 100 s of continuous raw data (with little artificial noise), when the rats were almost quiet, were selected for further analysis. For the task-state LFP, a 10 g von Frey filament was applied to a skin area in the incised paw medial to the caudal end of the wound for 10 s, and 5 s of raw data (with little artificial noise) during the stimulus were extracted to assess the influence of mechanical stimulation. The Fourier transform was used to acquire the power spectral density in different frequency bands. Then, the LFP signals were divided into delta (0–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–15 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz), low-gamma (30–60 Hz), and high-gamma (60–100 Hz) bands for quantitative analysis. The coherence between different brain areas was calculated using a homemade script in Spike2 software, which is provided in the supplemental materials.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS 24.0 (IBM, New York, USA), GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, New York, USA), and MatLab (R2018b, MathWorks Inc. 2018) and were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The OPLS-DA method was applied in MetaboAnalyst 3.5, and the microphotographs were processed using ImageJ 4.7. The data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A two-way analysis of variance was then used to assess the interaction of treatment with time to test the hypothesis that ASD increases the effects of the surgery on mechanical thresholds of mice. To compare the differences between the two groups, an independent-samples t-test was applied. The data from the fMRI were analyzed with voxel-wise one-sample t-test within groups and two-sample t-test between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Incisional Pain

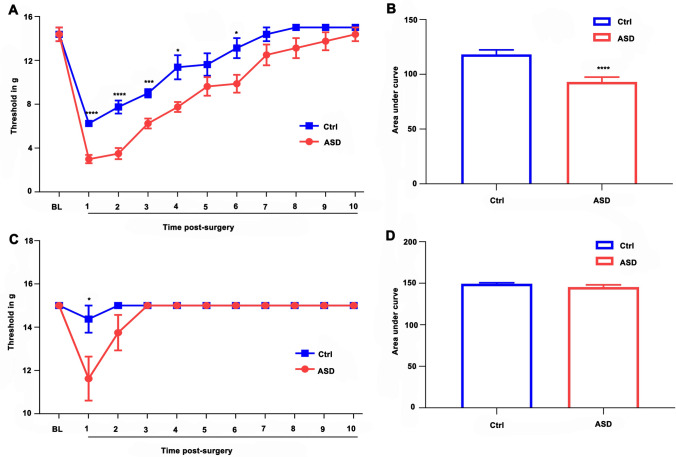

The mechanical thresholds of both hind paws of the animals in the ASD and Ctrl groups (Ctrl, n = 8) are illustrated in Fig. 2. Trends of the mechanical sensitivity of the right paw (ipsilateral) in the two groups on day 10 after surgery are shown in Fig. 2A, B. The two-way analysis of variance indicated significant effects of time (F = 81.810; df = 2.975; P < 0.0001) and treatment (F = 20.304; df = 1; P = 0.0005). There was no significant interaction between time and treatment. The post hoc test revealed significant reductions in the mechanical threshold of rats in the ASD group compared to the Ctrl group (on days 1–4 and 6). The area under the curve of the postoperative mechanical thresholds of the two groups over 10 days is shown in Fig. 2B (P < 0.0001). The thresholds of mechanical stimulation of the left paw (contralateral) in the two groups, 10 days post-operation, were also recorded (Fig. 2C, D). The two-way analysis of variance indicated significant effects of time (F = 8.269; df = 1.578; P = 0.004), treatment (F = 5.278; df = 1.578; P = 0.036), and a time–treatment interaction (F = 5.278; df = 1; P = 0.038). The post hoc test revealed that the mechanical thresholds of animals in the ASD group were significantly reduced one day after surgery relative to the Ctrl group (Fig. 2C, P = 0.041). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the area under the curve between the ASD and Ctrl groups after 10 days (Fig. 2D, P = 0.170).

Fig. 2.

Postoperative hyperalgesia induced by preoperative acute sleep deprivation (ASD). A The threshold was measured in the ipsilateral paw using von Frey hairs for 10 days after the surgical incision. B The area under the curve from the ipsilateral paw across these 10 days shows that preoperative ASD increases postoperative mechanical pain sensitivity. C The mechanical threshold of the contralateral paw measured for 10 days after the surgical incision, and D the area under the curve of the contralateral paw across these 10 days..*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 between the Ctrl and ASD groups.

Variations in Metabolic Kinetics of Different Brain Regions After ASD

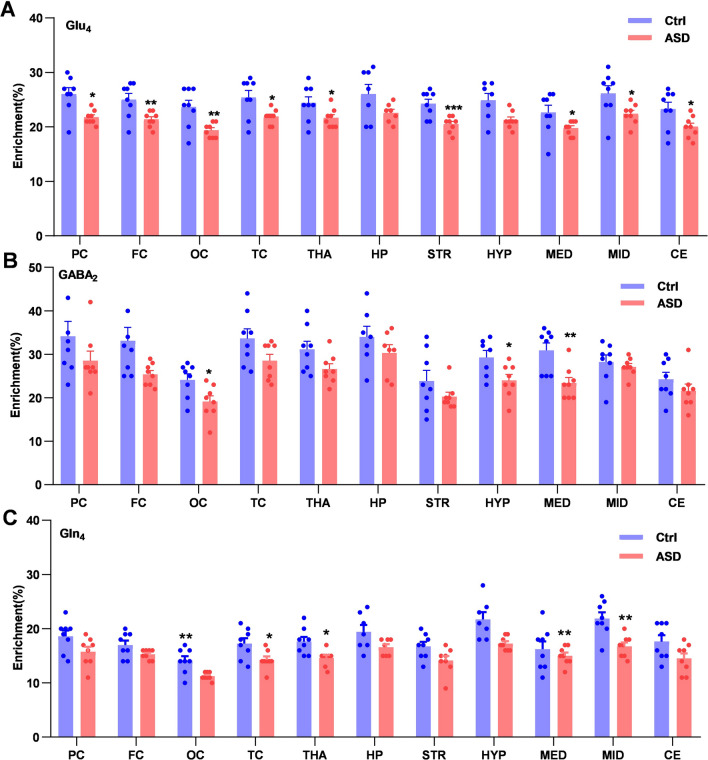

As a unique and noninvasive method, the NMR technique can help to explore the imbalance of cerebral energy metabolism in neuronal activity of different brain regions, so we used it to assess the metabolic kinetics and neurotransmission in different brain regions of the Ctrl and ASD groups. With the metabolism of [1–13C] glucose, the locations of metabolites were gradually labeled with 13C through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle among glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons, and astroglia [28]. Briefly, in the first TCA cycle, glutamate (Glu4) was labeled in the glutamatergic neurons, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA2) in the GABAergic neurons, and glutamine (Gln4) in the astroglia. Then, in the following TCA cycles, the other carbon positions of metabolites were subsequently labeled.

After infusing the labeled glucose, the enrichment of blood [1–13C] glucose was assessed using the 1H-NMR method in these two groups (Ctrl vs ASD: 67.84% ± 1.02% vs 54.65% ± 3.52%, P = 0.003). To reflect the changes in metabolites in the whole brain, the 13C enrichment of some important metabolites (Glu4, GABA2, and Gln4) was calculated and compared between the two groups among 11 different brain regions (Fig. 3). Compared to the Ctrl group, Glu4 (Fig. 3A) was significantly decreased in PC (P = 0.016), FC (P = 0.005), OC (P = 0.008), TC (P = 0.017), THA (P = 0.035), STR (P = 0.0007), MED (P = 0.019), MID (P = 0.037), and CE (P = 0.043), GABA2 was significantly decreased in FC (P = 0.029), OC (P = 0.021), HYP (P = 0.024), and MED (P = 0.005) (Fig. 3B), and the enrichment of Gln4 (Fig. 3C) was significantly decreased in OC (P = 0.006), TC (P = 0.027), THA (P = 0.013), MED (P = 0.006), and MID (P = 0.002).

Fig. 3.

The 13C enrichment of different metabolites in 11 brain regions from the Ctrl and ASD groups. A Glu4. B GABA2. C Gln4. ASD, acute sleep deprivation; Glu, glutamate; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; Gln, glutamine; subscript number, 13C labelled positions in the related metabolite; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Changes in Metabolic Kinetics and Discriminant Analysis of Specific Brain Regions

With the OPLS-DA method, we analyzed the enrichment of metabolites in 11 brain regions (FC, PC, OC, TC, STR, HP, THA, HYP, MID, MED, and CE). However, we only found that the metabolic changes in the striatum and midbrain illustrated a clear separation for all samples, which meant the metabolic kinetics of some important metabolites in the striatum and midbrain were most significantly reduced after SD. Thus, the striatum and midbrain were focused on for the next analysis. The 13C enrichment of various metabolites in the striatum is presented in Fig. 4A. There were significant differences between the two groups in some metabolites associated with glutamate in the striatum, such as Glu3 (P = 0.002), Glu4 (P = 0.0007), Glx2 (P = 0.012) (Glx: a mixture of glutamate and glutamine), and Glx3 (P = 0.005). To explore the dominant metabolite changes induced by ASD, the OPLS-DA method was applied to discriminate the samples in the two different groups. The score plot of the striatum (Fig. 4B) showed a clear separation between the Ctrl and ASD groups. In the OPLS-DA method, the variable importance in projection (VIP) was considered in order to assess the influence of different metabolites on the classification of samples in each group. VIP ≥ 1 was the criterion for screening major differential metabolites between these groups. The major differential metabolites were Glx3, Glu3, Glx2, Glu4, and Gln4 for the striatum (Fig. 4C). The midbrain region showed significantly decreased 13C enrichment in several metabolites in the ASD group (Fig. 4D), such as Glu4 (P = 0.037), Glx2 (P = 0.032), Glx3 (p = 0.048), Gln4 (P = 0.002), GABA3 (P = 0.006), GABA4 (P = 0.034), alanine (Ala3, P = 0.0005), and aspartate (Asp3, P=0.006). The scores plot of the midbrain (Fig. 4E) also demonstrated a clear separation between the Ctrl and ASD groups, and major differential metabolites for the midbrain were found in the two groups, such as Ala3, GABA3, Gln4, Asp3, and GABA4 (Fig. 4F, VIP ≥1).

Fig. 4.

Variations in the metabolic kinetics and the metabolomics analysis (OPLS-DA) for the striatum and midbrain regions. A–C 13C enrichment of various metabolites (A), OPLS-DA scores (B), and predictive VIP values (C) in the striatum of the two groups. D–F 13C enrichment of various metabolites (D), OPLS-DA scores (E), and predictive VIP values (F) in the midbrain of the two groups. ASD, acute sleep deprivation; Asp, aspartate. Ala, alanine. GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; Gln, glutamine. Glu, glutamate; Glx, glutamine+glutamate; subscript number, 13C labelled positions in metabolites; T score [1], first predictive component score; orthogonal T [1], orthogonal principal component score; VIP, variable importance in projection; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

fMRI Analysis of Functional Connectivity in the Whole Brain

The rsfMRI method was applied to analyze the FC in the brains of the animals of the two groups. The FC values (59 brain regions) [38] were calculated and collected using the rsfMRI method, and the correlation coefficients between the different regions were analyzed in the different groups (Fig. 5A, B). The inter-regional FC values of the two groups were both reduced due to the aseptic incision surgery. Compared to the Ctrl group, 21 pairs of FC in different brain regions were suppressed in the ASD group and five pairs were increased (P < 0.05). Compared to the Ctrl group, four pairs of suppressed FC were related to the PAG. The FC between the intermedial entorhinal and other regions contributed to 6 pairs of suppressed FC. In addition, four pairs of suppressed FC were associated with the retrosplenial granular cortex.

Fig. 5.

Results of fMRI analysis. A and B The functional connectivity matrices in 59 brain regions for the Ctrl (A) and ASD (B) groups. C The differences between these two groups in functional connectivity between an ROI (left NAc or right NAc) and other regions in the whole brain. White *, significantly decreased vs Ctrl (P < 0.05); black *, significantly increased vs Ctrl (P < 0.05); color bar in (A, B), Pearson correlation coefficients; color bar in (C), voxel-wise t-test for screening significant changes of functional connectivity between ROIs and other regions (P < 0.05); axis values, distances to Bregma (mm) from the Paxinons & Watson atlas; ROI, region of interest; M1, primary motor cortex; M2, secondary motor cortex; CA2, CA2 field of the hippocampus; mRt, medial pretectal nucleus; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; LPO, lateral preoptic area; MPA, medial preoptic area; Pn, pontine nuclei; MPtA, medial parietal association cortex; BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus.

With the help of the metabolic kinetic method, the striatum and midbrain were found to be the major ASD-induced hyperalgesia-related regions. Among these two regions, the NAc has been shown to play a crucial role in controlling sleep and wakefulness [39]. Meanwhile, the NAc is also known to be implicated in pain modulation [40]. Therefore, it was selected as a seed ROI, and the FC was analyzed between the NAc and other regions (Fig. 5C). The results indicated that the FCs between the left NAc and other regions, such as M1, M2, left CA2, mRt, and PAG, were suppressed in the ASD group, and the FCs between the left NAc and S1, LPO, MPA, and Pn were increased. In addition, the FCs between the right NAc and M1, M2, and mRt were suppressed following ASD but the FCs between the right NAc and LPO, BLA, S1, and PtA were increased. According to the results of metabolic kinetics and functional network analysis, the NAc (a subregion of the striatum) and the vLPAG (a subregion of the midbrain) were selected for further study.

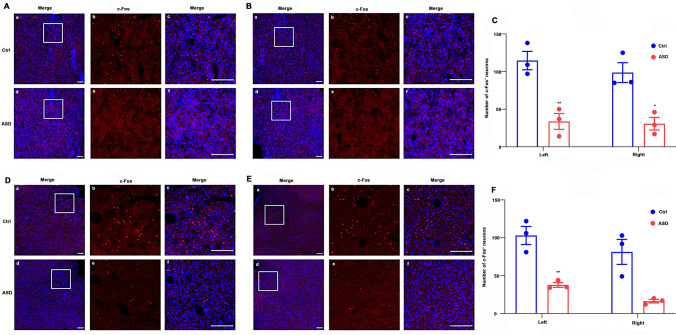

c-Fos Expression

c-Fos was regarded as a marker for reflecting the difference in neuronal activity between the two groups [41]. The c-Fos expression in the bilateral NAc was significantly decreased in the ASD group (Fig. 6A–C). The number of c-Fos+ neurons in the ASD group largely decreased in the left NAc (Ctrl vs ASD: 114 ± 12 vs 34 ± 11, P = 0.007) and the right NAc (Ctrl vs ASD: 99 ± 13 vs 31 ± 8, P = 0.012), as depicted in Fig. 6C. The c-Fos expression in the bilateral vLPAG in the two groups is shown in Fig. 6D–F. Compared to the Ctr group, the c-Fos expression was only significantly reduced in the left vLPAG (Ctrl vs ASD: 103 ± 12 vs 38 ± 3, P = 0.006). Moreover, there was no significant difference in the c-Fos expression in the right vLPAG between the two groups (Ctrl vs ASD: 81 ± 16 vs 16 ± 2, P = 0.056, Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

c-Fos expression in the NAc and the vLPAG (left and right) in the ASD and Ctrl groups. A Left NAc. B Right NAc. C Statistical analysis of c-Fos expression in the NAc (mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group). D Left vLPAG. E Right vLPAG. F Statistical analysis of c-Fos expression in the vLPAG (mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group). The immunofluorescence staining of c-Fos (red) and DAPI (blue) in the NAc and the vLPAG (A, B and D, E) shown as A–F, in which B, C and E, F mean enlarged images of insets in A, B and D, E respectively; Scale bars, 200 μm; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

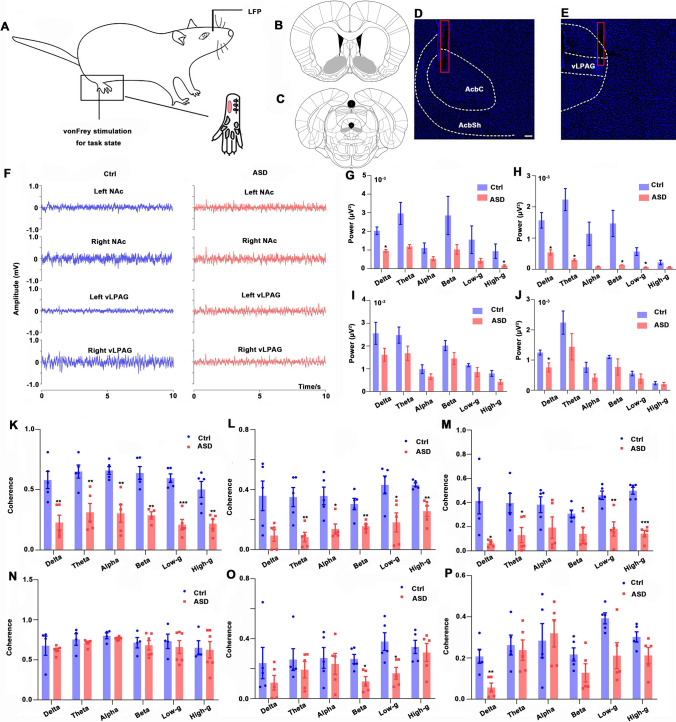

Coherences of the NAc and the vLPAG Using in vivo Electrophysiological Recording

To explore the neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG in the Ctrl and ASD groups, electrophysiological recordings (LFP signals) were simultaneously recorded and analyzed in four different regions in the resting state and task state (10 g von Frey mechanical stimulation): left-NAc, right-NAc, left-vLPAG, and right-vLPAG (Fig. 7A–E). The recorded LFPs of four different channels in the two groups during the resting state of awake rats are provided in Fig. 7F.

Fig. 7.

LFP in the NAc and the vLPAG and coherence between the local field potentials (LFPs) of the NAc and the vLPAG in the two groups using electrophysiology in the resting state. A 10 g von Frey stimulation is applied to the pink area of the incised paw. The LFP of the NAc and the vLPAG (left and right) were recorded in the resting state and task state (under 1.5% isoflurane). B and C Locations of NAc and vLPAG in the rat brain (gray area). D and E Locations of the recording electrodes in the NAc and vLPAG (red box). F Representative electrophysiology recordings (10 s) from the two groups in the resting state from awake rats in regions of the NAc and vLPAG (left and right). G–J Power of LFPs in the right NAc (G), right vLPAG (H), left NAc (I), and left vLPAG (J) in different bands. K–P Coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and right NAc (K), the left NAc and right vLPAG (L), the left NAc and left vLPAG (M), the right vLPAG and left vLPAG (N), the right NAc and right vLPAG (O), the right NAc and left vLPAG (P) in different bands of the two groups. LFP, local field potential; AcbC, core of the NAc; AcbSh, shell of the NAc; ASD, acute sleep deprivation; scale bar, 200 μm; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The low-frequency LFP signals were calculated to reflect the large-scale neuronal network (delta, theta, alpha, beta, low-gamma, and high-gamma bands). Fig. 7G–J shows the power of LFPs (right NAc, right vLPAG, left NAc and left vLPAG) in the resting state (awake rats). Compared to the Ctrl group, the power of LFPs in the right NAc was significantly decreased in the delta (P = 0.014) and high-γ (P = 0.015) bands (Fig. 7G), and the power of LFPs in the right vLPAG was significantly reduced in the delta (P = 0.017), theta (P = 0.022), beta (P = 0.026), and low-gamma (P = 0.015) bands in the ASD group (Fig. 7H). Although there was no significant decline, there was, nonetheless, a tendency of decreasing the power of LFPs in the left NAc in the ASD group (Fig. 7I). In addition, Fig. 7J illustrates that the power of LFPs in the left vLPAG in the ASD group was remarkably reduced in the delta band (P = 0.031).

The coherence of spontaneous LFPs between the four brain regions was compared between the two groups (Fig. 7K–P). The decreased coherence of LFPs in 6 bands between the left NAc and the right NAc is shown in Fig. 7K (all P < 0.01). Compared to the Ctrl group, the coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the right vLPAG lower in the theta, alpha, beta, low-gamma, and high-gamma bands (all P < 0.05, Fig. 7L). The coherence of LFPs between the left vLPAG and the left NAc was lower in the delta, theta, beta, low-gamma, and high-gamma bands (all P < 0.05, Fig. 7M). The coherence of LFPs between the right vLPAG and the left vLPAG showed no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 7N). The coherence of LFPs between the right NAc and the right vLPAG in the beta (P = 0.01) and low-gamma (P = 0.018) was depressed (Fig. 7O), and the coherence of LFPs between the right NAc and the left vLPAG was reduced in the delta band (P = 0.006, Fig. 7P).

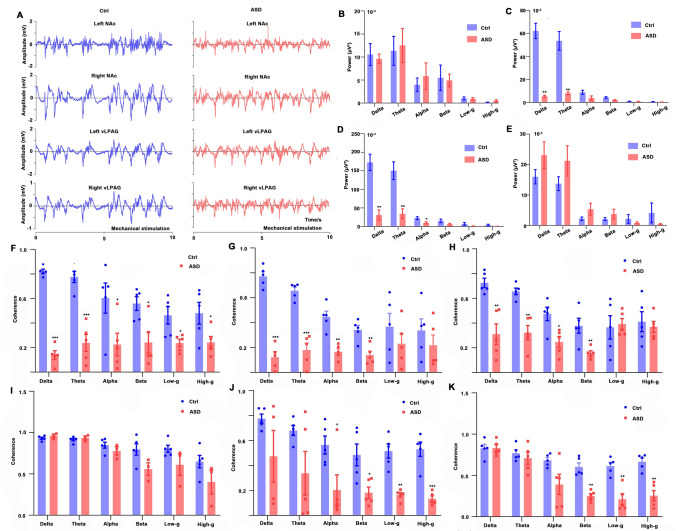

In anesthetized rats, the representative raw data of the signals of the task state (mechanical stimulation) are illustrated in Figs. 8A, and 8B–E shows the power of all bands of LFPs in the right NAc, right vLPAG, left NAc, and left vLPAG. There was no significant difference in the power of LFPs in all bands in the right NAc (Fig. 8B). The power of LFPs in the right vLPAG in the delta (P = 0.001) and theta (P = 0.006) bands were suppressed (Fig. 8C). The power of LFPs in the left-NAc of the ASD group was significantly decreased in the delta (P = 0.001), theta (P = 0.003), and alpha (P = 0.030) bands (Fig. 8D). There was no significant difference in the power of LFPs in the left vLPAG between the Ctrl and ASD rats (Fig. 8E). When the coherence of LFPs in the task state was compared between these two groups (Fig. 8F–K), the coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the right NAc was significantly reduced in all bands (all P < 0.05) compared to the Ctrl group (Fig. 8F). There were some significant differences in the coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the right vLPAG between the two groups (P < 0.01 in the delta, theta, alpha, and beta bands, Fig. 8G). The coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the left vLPAG was suppressed in the delta, theta, alpha, and beta bands (P < 0.05) compared to the Ctrl group (Fig. 8H), and the coherence of LFPs between the right vLPAG and the left vLPAG showed no significant difference in the two groups (Fig. 8I). Decreased coherence of LFPs between the right NAc and the right vLPAG was found in the alpha, beta, low-gamma, and high-gamma bands (P < 0.05, Fig. 8J). The coherence of LPFs between the right NAc and the left vLPAG was significantly reduced in the beta, low-gamma, and high-gamma bands (P < 0.01, Fig. 8K).

Fig. 8.

LFP in the NAc and the vLPAG and the coherence between their local field potentials (LFPs) in the two groups using electrophysiology in the task state. A Representative electrophysiology recordings from the two groups (5 s for the resting state + 5 s for mechanical stimulation from anesthetized rats) in the NAc and vLPAG (left and right); B–E TPower of LFPs in the regions of the right NAc (B), right vLPAG (C), left NAc (D) and left vLPAG (E) in different bands. F–K Coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and right NAc (F), the left NAc and right vLPAG (G), the left NAc and left vLPAG (H), the right vLPAG and left vLPAG (I), the right NAc and right vLPAG (J), the right NAc and left vLPAG (K) in different bands of the two groups. LFP, local field potentia;. ASD, acute sleep deprivation; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01,***P < 0.001

Discussion

In the current study, we screened the abnormal brain regions with variations in cerebral function and activities of hyperalgesia induced by preoperative ASD using multi-modal techniques. The results revealed that the neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG was suppressed and the FC between the NAc and the vLPAG was decreased in the rats with ASD-induced hyperalgesia, which offers a potential direction for future research. In addition, the current work provides a combinational method for screening the major brain subregions related to ASD-induced hyperalgesia, which can be used in other kinds of brain disease.

Influence of Acute Preoperative Sleep Loss on Postoperative Incisional Pain

The preoperative sleep state is one of the most important factors associated with postoperative pain management [3, 5, 6, 42]. Therefore, in this study we paid attention to the influences of acute preoperative sleep loss on post-operative mechanical hyperalgesia. We adopted a model in which the rats experienced incisional pain after 6 h of ASD. There are three reasons for the selection of this model. First, considering the characteristics of preoperative ASD in clinical settings, it is partial ASD, not total ASD (all night). Accordingly, 6 h of sleep deprivation better mimics the clinical setting. Second, some studies have shown that partial ASD is enough to cause hyperalgesia [8, 9]. Third, previous studies have suggested that ASD by a gentle handling procedure does not significantly alter stress hormone levels [5, 43]. Thus, a gentle handling procedure was applied to induce ASD without altering the stress response. Recent findings have indicated that 6 h of SD induces significant post-operative mechanical hyperalgesia and prolongs the recovery time. Consistent with our results, it has been reported that ASD before pain onset increases the duration of pain in models of inflammatory [19] and musculoskeletal pain [44]. These results provide valuable support for the notion that ASD can increase pain sensitivity and contribute to the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Metabolic Cross-talk in the Whole Brain After ASD

The NMR technique is regarded as a unique and noninvasive method to investigate the metabolic kinetics and evaluate the dynamic information of neurotransmitter transmission [27]. In this study, the NMR method was applied to reflect the real-time metabolic changes in different brain regions. Notably, we assessed the enrichment of blood [1–13C] glucose and found that the levels of glucose metabolism, which reflect neuronal activity [45], showed significant decreases following ASD. The metabolic kinetics in every brain region was also decreased in the ASD group. This means that the hyperalgesia induced by ASD suppresses the TCA cycle, which generates ATP for neuronal activity.

The cerebral glutamate-glutamine (Glu-Gln) cycle accounts for ~ 80% of glucose consumption in neurons and glia [27]. Thus, it is valuable to disclose the metabolic kinetics of the metabolites involved in the Glu-Gln cycle. With the OPLS-DA method, the metabolic changes in the striatum and midbrain depicted a clear separation between the two groups and the metabolites related to the Gln-Glu cycle were significantly decreased in the striatum and midbrain following ASD. This phenomenon indicates that the cerebral energy metabolism related to neuronal activity is downregulated in the striatum and midbrain after acute sleep loss. In line with our results, the study by Briggs et al. also demonstrated that 6 h of SD weakens the activity of wake-promoting neurons [46].

Mapping Pain-related Functional Networks Following ASD

The non-invasive rsfMRI technique is used for investigating changes in the functional networks of the brain, reflecting the FC between different regions and exploring the FC in humans or animals under different physiological and pathological conditions. A previous study found that FC can serve as an essential biomarker which contributes to evaluating the functionality of potential neural circuits between different brain regions [47]. Thus, it is important to map the pain-related functional networks following ASD.

It is also well established that the NAc is a necessary component of the neural circuit related to pain processing and modulation [48–50]. For example, fMRI has shown that the NAc is activated at pain onset [40], but weakens during non-painful punishment [51]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the NAc is of great importance in sleep-wake regulation [39, 52]. Thus, based on the important role in sleep-waking and pain modulation, the NAc, in the ventral striatum, was selected as the region of interest for seed-based network analysis. The results indicated that the FC between the left NAc and the vLPAG was suppressed following ASD. Some studies have demonstrated a role of the NAc in the sleep–pain interaction [53]. For example, fMRI results from healthy volunteers showed that ASD weakens the NAc activation during pain onset [40]. Furthermore, with rsfMRI, results from healthy volunteers revealed that ASD (one night) decreases the pain-related neuronal activity in the NAc core [12].

ASD increases pain sensitivity by suppressing neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG

c-Fos expression reflects the activation of neurons [54]. In this study, the number of c-Fos+ neurons in the NAc was significantly decreased after ASD. In line with the alteration of c-Fos expression, the power of LFPs in the NAc was reduced in the ASD group. This indicated that ASD-induced hyperalgesia suppresses neuronal activity in the NAc. In previous findings, increased neuronal activity in the NAc has been found in rats chronically restricted from sleep during pain onset [55]. Conversely, REM sleep deprivation does not disturb neuronal activity in the NAc [53]. The discrepancy in these results is interesting and explainable. It is possible that different types of SD lead to differences in neuronal activity in the NAc.

To our knowledge, the PAG, a subregion of the midbrain, is the center of descending pain modulation [56]. In addition, the PAG is involved in the modulation of the sleep-wake cycle [57]. A previous study indicated that reduced dopaminergic neurons in the PAG increase the thermal pain sensitivity of sleep-deprived rats [58]. In the current study, we found that the rats with ASD-induced hyperalgesia showed decreased neuronal activity in the vLPAG. In line with our results, Tomim and colleague demonstrated decreased neuronal activity in the vPAG after 24 h of SD [42].

The variations in LFP power of the bilateral NAc under resting and task conditions were different in the current study. In the resting state, the LFP power in the right NAc was significantly decreased in some bands, but not in the left NAc. However, there was a decreasing tendency in the left NAc in the ASD rats. In the task-state analysis, the variations in LFP power changed from the right NAc to the left NAc, which is consistent with a former study [40], in which, compared to uninterrupted volunteers, the left NAc showed greater NAc activation for tonic pain than the right in SD volunteers. Thus, the left NAc might play a more essential role in modulating pain perception during the task state.

The coherence of LFPs was applied to represent the degree of phase consistency between two brain areas [59]. The results showed that the coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the right NAc in the ASD group was significantly decreased in every band whether in the resting state or the task state, which suggests that ASD-induced hyperalgesia remarkably weakens the correlation between the bilateral NAc. Furthermore, the coherence of LFPs between the left NAc and the vLPAG was significantly reduced, which is consistent with the suppressed FC between the left NAc and the vLPAG. These results demonstrate that ASD-induced hyperalgesia suppresses the FC between the NAc and the vLPAG.

Novelty Statement and Limitations

To screen the brain regions related to the hyperalgesia induced by preoperative ASD, a multi-modal technique was applied in the current study. Compared with the simple combination of previous studies, which only used a single or a few techniques, the results from the current study were based on the same control of the animal model. Differences in establishing the animal model exist in different studies even under the same protocol, which could affect the final results. For example, 6 h of SD significantly increased the postoperative pain sensitivity in comparison to the ad libitum sleep group [5]. However, another study found that 6 h of SD does not induce mechanical hyperalgesia [60]. In addition, multi-modal techniques avoid the limitations of individual methods and acquire more reliable information [61]. Thus, we believe that the results using a multi-modal technique based on the same control of the animal model provide more reliable and valuable information and the multi-modal strategy provides a fresh perspective on exploring neuroscience.

However, there are also some limitations in the present study. First, the number of animals in fMRI analysis was small and the uncorrected P value (P < 0.05) was applied to roughly screen the sub-region in this work. The fMRI results provided a guideline for sub-region selection, and c-Fos expression and electrophysiology were used to verify the results. Second, the FC between the NAc and the vLPAG was measured using fMRI and electrophysiological techniques. However, the type of neuron should be further identified and the upstream and downstream relations between the NAc and the vLPAG clarified using optogenetic manipulation or pharmacological intervention. Third, the potential mechanism of ASD-induced hyperalgesia may be different from that caused by chronic sleep restriction, which requires further investigation.

Conclusions

The current study, using multi-modal techniques, indicates that neuronal activity in the NAc and the vLPAG and the FC between the NAc and the vLPAG are both weakened in rats with ASD-induced hyperalgesia. Hence, this study provides a potential direction to study the mechanism of ASD-induced hyperalgesia and highlights the importance of preoperative sleep management for surgical patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071208, 81870851, 31771193, and 81971775), the Outstanding Talented Young Doctor Program of Hubei Province (HB20200407), the Translational Medicine, and interdisciplinary Research Joint Fund of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (ZNJC202012), the Medical Sci-Tech Innovation Platform of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB32030200).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Meimei Guo and Yuxiang Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jie Wang, Email: jie.wang@wipm.ac.cn.

Mian Peng, Email: mianpeng@whu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Stewart NH, Arora VM. Sleep in hospitalized older adults. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesselius HM, van den Ende ES, Alsma J, Ter Maaten JC, Schuit SCE, Stassen PM, et al. Quality and quantity of sleep and factors associated with sleep disturbance in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1201–1208. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang PK, Cao J, Wang HZ, Liang LL, Zhang J, Lutz BM, et al. Short-term sleep disturbance-induced stress does not affect basal pain perception, but does delay postsurgical pain recovery. J Pain. 2015;16:1186–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30:213–218. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambrecht-Wiedbusch VS, Gabel M, Liu LJ, Imperial JP, Colmenero AV, Vanini G. Preemptive caffeine administration blocks the increase in postoperative pain caused by previous sleep loss in the rat: A potential role for preoptic adenosine A2A receptors in sleep-pain interactions. Sleep. 2017 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue JJ, Li HL, Xu ZQ, Ma DX, Guo RJ, Yang KH, et al. Paradoxical sleep deprivation aggravates and prolongs incision-induced pain hypersensitivity via BDNF signaling-mediated descending facilitation in rats. Neurochem Res. 2018;43:2353–2361. doi: 10.1007/s11064-018-2660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Zhu ZY, Lu J, Chao YC, Zhou XX, Huang Y, et al. Sleep deprivation of rats increases postsurgical expression and activity of L-type calcium channel in the dorsal root ganglion and slows recovery from postsurgical pain. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:217. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0868-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haack M, Mullington JM. Sustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-being. Pain. 2005;119:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roehrs T, Hyde M, Blaisdell B, Greenwald M, Roth T. Sleep loss and REM sleep loss are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006;29:145–151. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Short sleep duration among workers—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012, 61: 281–285. [PubMed]

- 11.Vanini G. Nucleus accumbens: A novel forebrain mechanism underlying the increase in pain sensitivity caused by rapid eye movement sleep deprivation. Pain. 2018;159:5–6. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause AJ, Prather AA, Wager TD, Lindquist MA, Walker MP. The pain of sleep loss: A brain characterization in humans. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2291–2300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2408-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chee MWL, Zhou J. Functional connectivity and the sleep-deprived brain. Prog Brain Res. 2019;246:159–176. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques-Carneiro JE, Nehlig A, Cassel JC, Castro-Neto EF, Litzahn JJ, Pereira de Vasconcelos A, et al. Neurochemical changes and c-fos mapping in the brain after carisbamate treatment of rats subjected to lithium-pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2017;10:85. doi: 10.3390/ph10040085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monosov IE, Trageser JC, Thompson KG. Measurements of simultaneously recorded spiking activity and local field potentials suggest that spatial selection emerges in the frontal eye field. Neuron. 2008;57:614–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li B, Gong L, Wu RQ, Li AN, Xu FQ. Complex relationship between BOLD-fMRI and electrophysiological signals in different olfactory bulb layers. NeuroImage. 2014;95:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Hamrani D, Gin H, Gallis JL, Bouzier-Sore AK, Beauvieux MC. Consumption of alcopops during brain maturation period: Higher impact of fructose than ethanol on brain metabolism. Front Nutr. 2018;5:33. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Li AN, Gong L, Zhang L, Wu N, Xu FQ. Decreased coherence between the two olfactory bulbs in Alzheimer's disease model mice. Neurosci Lett. 2013;545:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanini G. Sleep deprivation and recovery sleep prior to a noxious inflammatory insult influence characteristics and duration of pain. Sleep. 2016;39:133–142. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanini G, koNemanis K, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R. GABAergic transmission in rat pontine reticular formation regulates the induction phase of anesthesia and modulates hyperalgesia caused by sleep deprivation. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:2264–2273. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung S, Weber F, Zhong P, Tan CL, Nguyen TN, Beier KT, et al. Identification of preoptic sleep neurons using retrograde labelling and gene profiling. Nature. 2017;545:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature22350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64:493–502. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song ZP, Xiong BR, Zheng H, Manyande A, Guan XH, Cao F, et al. STAT1 as a downstream mediator of ERK signaling contributes to bone cancer pain by regulating MHC II expression in spinal microglia. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang N, Zhao LC, Zheng YQ, Dong MJ, Su YC, Chen WJ, et al. Alteration of interaction between astrocytes and neurons in different stages of diabetes: A nuclear magnetic resonance study using[1-(13)C]glucose and[2-(13)C]acetate. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:843–852. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, Niu ZF, Hu XL, Liu HL, Li S, Chen L, et al. Regional cerebral metabolic levels and turnover in awake rats after acute or chronic spinal cord injury. FASEB J. 2020;34:10547–10559. doi: 10.1096/fj.202000447R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo MM, Fang YY, Zhu JP, Chen C, Zhang ZZ, Tian XB, et al. Investigation of metabolic kinetics in different brain regions of awake rats using the[1H-13C]-NMR technique. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;204:114240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Jiang L, Jiang Y, Ma X, Chowdhury GM, Mason GF. Regional metabolite levels and turnover in the awake rat brain under the influence of nicotine. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1447–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sibson NR, Mason GF, Shen J, Cline GW, Herskovits AZ, Wall JE, et al. In vivo (13)C NMR measurement of neurotransmitter glutamate cycling, anaplerosis and TCA cycle flux in rat brain during. J Neurochem. 2001;76:975–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu TT, Li ZQ, He JD, Yang N, Han DY, Li Y, et al. Regional metabolic patterns of abnormal postoperative behavioral performance in aged mice assessed by 1 H-NMR dynamic mapping method. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:25–38. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00414-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Zeng HL, Du HY, Liu ZY, Cheng J, Liu TT, et al. Evaluation of metabolites extraction strategies for identifying different brain regions and their relationship with alcohol preference and gender difference using NMR metabolomics. Talanta. 2018;179:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng DH, Li Z, Li S, Li XH, Kamal GM, Liu CY, et al. Identification of metabolic kinetic patterns in different brain regions using metabolomics methods coupled with various discriminant approaches. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;198:114027. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu TT, He ZG, Tian XB, Kamal GM, Li ZX, Liu ZY, et al. Specific patterns of spinal metabolites underlying α-Me-5-HT-evoked pruritus compared with histamine and capsaicin assessed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1222–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Patel AB, Behar KL, Rothman DL. In vivo 1H-[13C]-NMR spectroscopy of cerebral metabolism. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:339–357. doi: 10.1002/nbm.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Li S, Zhou Y, Liu TT, Cai AL, Zhang ZZ, et al. Neuronal mechanisms of adenosine A2A receptors in the loss of consciousness induced by propofol general anesthesia with functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurochem. 2021;156:1020–1032. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwok CHT, Learoyd AE, Canet-Pons J, Trang T, Fitzgerald M. Spinal interleukin-6 contributes to central sensitisation and persistent pain hypersensitivity in a model of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;90:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Cheng J, Liu HL, Deng YH, Wang J, Xu FQ. NMRSpec: An integrated software package for processing and analyzing one dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectra. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2017;162:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrière DA, Magalhães R, Novais A, Marques P, Selingue E, Geffroy F, et al. The SIGMA rat brain templates and atlases for multimodal MRI data analysis and visualization. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5699. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo YJ, Li YD, Wang L, Yang SR, Yuan XS, Wang J, et al. Nucleus accumbens controls wakefulness by a subpopulation of neurons expressing dopamine D 1 receptors. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1576. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03889-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seminowicz DA, Remeniuk B, Krimmel SR, Smith MT, Barrett FS, Wulff AB, et al. Pain-related nucleus accumbens function: Modulation by reward and sleep disruption. Pain. 2019;160:1196–1207. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang F, Sun WJ, Chang L, Sun KF, Hou LY, Qian LN, et al. cFos-ANAB: A cFos-based web tool for exploring activated neurons and associated behaviors. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:1441–1453. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00744-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomim DH, Pontarolla FM, Bertolini JF, Arase M, Tobaldini G, Lima MMS, et al. The pronociceptive effect of paradoxical sleep deprivation in rats: Evidence for a role of descending pain modulation mechanisms. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1706–1717. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rechtschaffen A, Bergmann BM, Gilliland MA, Bauer K. Effects of method, duration, and sleep stage on rebounds from sleep deprivation in the rat. Sleep. 1999;22:11–31. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutton BC, Opp MR. Sleep fragmentation exacerbates mechanical hypersensitivity and alters subsequent sleep-wake behavior in a mouse model of musculoskeletal sensitization. Sleep. 2014;37:515–524. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiede W, Magerl W, Baumgärtner U, Durrer B, Ehlert U, Treede RD. Sleep restriction attenuates amplitudes and attentional modulation of pain-related evoked potentials, but augments pain ratings in healthy volunteers. Pain. 2010;148:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briggs C, Hirasawa M, Semba K. Sleep deprivation distinctly alters glutamate transporter 1 apposition and excitatory transmission to orexin and MCH neurons. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2505–2518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2179-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang ZF, King J, Zhang NY. Anticorrelated resting-state functional connectivity in awake rat brain. NeuroImage. 2012;59:1190–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benarroch EE. Involvement of the nucleus accumbens and dopamine system in chronic pain. Neurology. 2016;87:1720–1726. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitsi V, Zachariou V. Modulation of pain, nociception, and analgesia by the brain reward center. Neuroscience. 2016;338:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu XB, Zhu Q, Gao YJ. CCL2/CCR2 contributes to the altered excitatory-inhibitory synaptic balance in the nucleus accumbens shell following peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:921–933. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delgado MR, Nystrom LE, Fissell C, Noll DC, Fiez JA. Tracking the hemodynamic responses to reward and punishment in the striatum. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:3072–3077. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oishi Y, Xu Q, Wang L, Zhang BJ, Takahashi K, Takata Y, et al. Slow-wave sleep is controlled by a subset of nucleus accumbens core neurons in mice. Nat Commun. 2017;8:734. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00781-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sardi NF, Tobaldini G, Morais RN, Fischer L. Nucleus accumbens mediates the pronociceptive effect of sleep deprivation: The role of adenosine A2A and dopamine D2 receptors. Pain. 2018;159:75–84. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin XX, Itoga CA, Taha S, Li MH, Chen R, Sami K, et al. c-Fos mapping of brain regions activated by multi-modal and electric foot shock stress. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;8:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sardi NF, Lazzarim MK, Guilhen VA, Marcílio RS, Natume PS, Watanabe TC, et al. Chronic sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity over time in a periaqueductal gray and nucleus accumbens dependent manner. Neuropharmacology. 2018;139:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagley EE, Ingram SL. Endogenous opioid peptides in the descending pain modulatory circuit. Neuropharmacology. 2020;173:108131. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu J, Jhou TC, Saper CB. Identification of wake-active dopaminergic neurons in the ventral periaqueductal gray matter. J Neurosci. 2006;26:193–202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2244-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skinner GO, Damasceno F, Gomes A, de Almeida OMMS. Increased pain perception and attenuated opioid antinociception in paradoxical sleep-deprived rats are associated with reduced tyrosine hydroxylase staining in the periaqueductal gray matter and are reversed by L-dopa. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Srinath R, Ray S. Effect of amplitude correlations on coherence in the local field potential. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112:741–751. doi: 10.1152/jn.00851.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexandre C, Latremoliere A, Ferreira A, Miracca G, Yamamoto M, Scammell TE, et al. Decreased alertness due to sleep loss increases pain sensitivity in mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nm.4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao C, Guo L, Dong JY, Cai ZW. Mass spectrometry imaging-based multi-modal technique: Next-generation of biochemical analysis strategy. Innovation (Camb) 2021;2:100151. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.