Abstract

Gastric cancer has one of the highest incidence rates and is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Sequential steps within the carcinogenic process are observed in gastric cancer as well as in pancreatic cancer and colorectal cancer. Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is the most well-known oncogene and can be constitutively activated by somatic mutations in the gene locus. For over 2 decades, the functions of Kras activation in gastrointestinal (GI) cancers have been studied to elucidate its oncogenic roles during the carcinogenic process. Different approaches have been utilized to generate distinct in vivo models of GI cancer, and a number of mouse models have been established using Kras-inducible systems. In this review, we summarize the genetically engineered mouse models in which Kras is activated with cell-type and/or tissue-type specificity that are utilized for studying carcinogenic processes in gastric cancer as well as pancreatic cancer and colorectal cancer. We also provide a brief description of histological phenotypes and characteristics of those mouse models and the current limitations in the gastric cancer field to be investigated further.

Subject terms: Cancer models, Cancer models

Gastrointestinal cancer: Progress in mouse models

Improvements to genetically engineered mouse models for studying a specific oncogene, a gene with the potential to cause cancer, in gastrointestinal (GI) cancers could help identify the precise cellular origins of these diseases. Mutations affecting the Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (Kras) are among the most common drivers of cancer. Kras activation varies in terms of incidence rates and roles across GI cancers. Eunyoung Choi and Yoonkyung Won at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, USA, reviewed the current scope of genetically engineered mouse models for studying Kras in gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers. Such models have contributed extensively to knowledge of alternate functions of Kras activation during carcinogenic process in different types of cell lineages or organs, and identification of molecular signatures underlying Kras activation.

Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract, as a part of the digestive system, includes the esophagus, stomach, pancreas, small intestine and colon; the GI tract is where foods and liquids enter into the body and are digested and nutrients are absorbed1. GI cancers represent a substantial proportion of cancer incidence and mortality worldwide2. GI cancers develop in a sequential carcinogenic process through a series of preneoplastic lesions. In the stomach, intestinal-type gastric cancer is the most common cancer type and is associated with environmental factors, such as acute mucosal injury by toxic drugs and chronic inflammation caused by Helicobacter pylori infection3,4. Intestinal-type gastric cancer develops within these preneoplastic metaplastic lesions from normal mucosal changes through chronic gastritis with mucosal atrophy and a multistep process, which involves the progression of preneoplastic pyloric metaplasia and intestinal metaplasia (IM) to neoplastic dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. These sequential changes were first described as the Correa pathway by Pelayo Correa5. Pyloric metaplasia can initially arise following acid-secreting parietal cell atrophy through the transdifferentiation of zymogen granule-secreting chief cells into metaplastic cells, called spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) cells, in response to mucosal injury6–9. While this initial process is potentially reversible, cell plasticity also permits the entry of metaplastic cells into carcinogenic transition, leading to the progression of reversible pyloric metaplasia to irreversible IM and neoplastic dysplasia10,11. This carcinogenic cascade is also observed in other GI tract cancers, such as esophageal, pancreatic and colorectal cancers12–14. In pancreatic carcinogenesis, several types of preneoplastic lesions have been identified, including pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasia (MCN)15. PanINs are characterized by a stepwise acquisition of mutations in Kras and Trp53 genes from low-grade dysplasia (PanIN 1-2) to carcinoma in situ (PanIN 3)16. Colorectal cancer also develops from the progression of acquired or hereditary premalignant lesions17,18. Colorectal carcinogenesis progresses from hyperproliferative regions in the normal colonic mucosa designated as polyps into early and late adenoma and finally carcinoma14,19.

Mutations influencing members of the rat sarcoma viral oncogene family (RAS) genes (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) are the most frequent genetic alterations in human cancers, accounting for approximately 30% of all tumors20. Ras proteins function as a simple binary ON–OFF molecular switch through the function of guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase), which controls cycles between an active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound and inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound state21. Kras is predominantly inactive and GDP-bound in quiescent cells, while it is active and GTP-bound in active cells where extracellular stimuli activate receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and other cell surface receptors. In cancers, the Ras genes harbor missense mutations that encode single amino acid substitutions primarily at one of three mutational spots: glycine-12 (G12), glycine-13 (G13), or glutamine-61 (Q61). These mutations block GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) from accessing GTP, and hydrolysis is prevented, resulting in persistent activation of the GTP-bound state22. In 1982, the Kras gene was the first oncogene identified in human cancer23 and one of the proto-oncogenes predominantly mutated in many GI cancers, including pancreatic, gastric, and colorectal cancer24–27. Because of various incidence rates and roles of Kras activation in different GI cancers, numerous studies have been performed to elucidate the oncogenic mechanisms of Kras in GI carcinogenesis11,28–36.

Experimental studies that induce mutations in animals can typically drive initiation processes in the development and promotion of the following stages. Many efforts have been made to investigate the detailed mechanisms of the carcinogenic process using genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs). Therefore, GEMMs have led to enormous advancements in understanding the fundamentals of tumor initiation, development, and metastatic spread. In the cancer field, many groups have put research efforts into the generation of preclinical mouse models for GI cancer studies37–41. In particular, the generation of the LoxP-STOP-LoxP (LSL)-KrasG12D mouse in 200142 allowed the expression of the mutant Kras allele in specific cell types under Cre recombinase activity controlled by the endogenous transcriptional activity of the driver gene locus. Here, we summarize GEMMs that develop active Kras-induced GI carcinogenesis and have been commonly used as in vivo mouse models in the GI cancer field. We also discuss the distinct functional roles and different histological phenotypes of GEMMs in gastric, pancreatic cancer, and colorectal cancers.

Kras activation in GI cancers

Several studies on the molecular profiling of gastric cancer have been performed to examine distinct molecular subtypes with clinical characteristics43–48. In particular, molecular characterization of gastric cancer cases by the TCGA project classified these cases into four distinct groups: Epstein‒Barr virus (EBV), microsatellite instability (MSI), genomically stable (GS), and chromosomal instability (CIN) subtypes. Among them, the CIN subtype is the most common subtype associated with intestinal-type histology and is characterized by genetic amplification/activation of the RTK/RAS signaling pathway and frequent Trp53 mutation43. Even though mutations of Kras are detected in approximately 10–15% of all gastric cancer cases, signatures for the activation and amplification of Kras are noted in at least 40% of human intestinal-type gastric cancers.

On the other hand, KRAS mutations are observed in approximately 90% of pancreatic cancer patients, and mutations in tumor suppressors such as CDKN2A/p16INK4A, Trp53, and SMAD4 are also common in pancreatic cancer. Of note, Kras mutations are an early oncogenic event in pancreatic carcinogenesis49–53. Colorectal cancer also develops through a series of germline or somatic mutations, which affect the homeostasis of oncogenes or tumor suppressors. A large proportion of somatic mutations have been identified in colorectal cancer, including mutations in Trp53, APC, KRAS, PIK3CA, SMAD4, FBXW7, and RNF43, which drive the progression of preneoplastic lesions to malignant colorectal cancer54.

GEMMs of Kras activation in the pancreas and colon

Mouse models of pancreatic cancer have been extensively well developed and utilized for several decades (Table 1). The GEMMs of pancreatic cancer display phenotypes of all recognized features observed in human pancreatic cancer development and progression, from the preneoplastic PanIN to invasive adenocarcinoma, representing the major example of Kras activation in the gastrointestinal cancer field. The GEMMs for studying pancreatic cancer were mostly generated using the Pdx1-Cre/CreERT or Ptf1a(P48)-Cre driver mouse allele32–34,55–60. Pdx1 is not a pancreas tissue-specific gene and is observed in the pancreas and the distal part of the stomach and duodenum. However, the Pdx1-Cre/CreERT mouse allele is often used as a ductal cell driver model in the pancreas32,34,55–58. The Ptf1a(P48)-Cre mouse allele is a pancreas tissue-specific and acinar cell-specific driver model32,34,59,60. Although Kras activation is induced in either ductal cells or acinar cells, both mouse models develop the full range of PanIN lesions and rare invasive adenocarcinomas that are histologically similar to those present in human patients32,33. Additionally, Kras activation in acinar cells using the Mist1-CreERT2, proCPA1-CreERT2, or Ela-CreERT2 mouse alleles also shows PanIN development with focal cystic neoplasia33,61. On the other hand, concurrent Kras activation and Trp53 deletion or coactivation of KrasG12D and Trp53R172H in the pancreas displayed malignant progression of preneoplastic PanIN to neoplastic stages33,34,62. Therefore, Trp53 mutations might be required for neoplastic transition from preneoplastic PanIN induced by Kras activation during pancreatic cancer development.

Table 1.

Genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic cancer.

| GEMM | References |

|---|---|

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Hingorani et al., 2003 |

| Ptf1a(P48)-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | |

| Ela-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Habbe et al., 2008 |

| Mist1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | |

| Pdx1-CreERT; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Gidekel Friedlander et al., 2009 |

| Pdx1-CreERT; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53fl/fl | |

| Pdx1-CreERT; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Ink4a/Arffl/fl ProCPA1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | |

| ProCPA1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53fl/fl | |

| ProCPA1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Ink4a/Arffl/fl | |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Ink4a/Arffl/fl | Aguirre et al., 2003 |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;LSL-Tp53R172H/+ | Hingorani et al., 2005 |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53fl/fl | Bardeesy et al., 2006 |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Ink4a/Arffl/+ or fl/fl | |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Ptenfl/+ or fl/fl | Ying et al., 2011 |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Lkb1fl/+ | Morton et al., 2010 |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;p21Cip1+/- | |

| Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Brca2fl/fl | Skoulidis et al., 2010 |

| Ptf1a(P48)-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;TGFbRIIfl/fl | Ijichi et al., 2006 |

| Ptf1a(P48)-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Smad4fl/+ or fl/fl;LSL-Tp53R172H/+ | Whittle et al., 2015 |

In the colon, the initial step in carcinogenesis is proposed to be the loss of the tumor suppressor gene Apc. The inactivation of Apc induces the β-catenin stabilization and translocation to the nucleus. Kras activation is an event during tumor progression, and the mutation is observed in approximately 40–50% of human colorectal cancer patients. However, the role of Apc loss of heterozygosity, rather than Kras activation, as a key mutation initiating the carcinogenic process in the colon is highlighted in several mouse models63–67. Among the inducible driver mouse alleles for studying colorectal cancer (Table 2), the Villin-Cre driver system, either constitutive expression of Cre (Villin-Cre) or tamoxifen-inducible expression of Cre (Villin-CreERT2), is the most common tool to restrict Cre recombinase activity to intestinal epithelial cells in both small intestine and colon68. Kras activation using the Villin-Cre/CreERT alleles was found to be insufficient to lead to the full process of colorectal carcinogenesis. However, carcinogenesis was promoted, and tumors developed with additional oncogenic gene mutations or treatment with chemicals, such as azoxymethane (AOM), in the colon35,69–72. Another driver of site-specific Cre expression is the fatty acid binding protein liver Cre transgene (Fabpl-Cre)67,73. While Villin-Cre is activated in the intestinal epithelial cells of the entire region of both the small intestine and the colon, Fabpl-Cre expression is detected in the distal small intestine, cecum, and colon64,73,74. The Ah-Cre driver under the control of the Cyp1A promotor is also used for colon cancer models, but the Cyp1A gene is also expressed in the liver, pancreas, and esophageal epithelium66,75. Moreover, several studies have focused on the function of intestinal stem cells using Lgr5- or Lrig1-CreERT2 mice76–78. Lgr5-CreERT2 mice with Apc deletion were found to exhibit adenoma formation76, but mice with Lrig1-CreERT2 with Apc deletion developed duodenal adenoma and superficially invasive adenocarcinoma77,78. However, few investigations have examined the oncogenic roles of Kras activation alone in depth using intestinal epithelial cell driver alleles, suggesting that Kras activation might be the second event in colorectal carcinogenesis. Therefore, it is not yet clear whether a single oncogenic activation of Kras is sufficient to develop adenocarcinoma in GI organs, and orchestrated induction of several oncogenes may be required for the full completion of carcinogenesis.

Table 2.

Genetically engineered mouse models of colorectal cancer.

| GEMM | References |

|---|---|

| Villin-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+; +AOM | Calcagno et al., 2008 |

| Villin-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Tgfbr2E2fl/E2fl | Trobridge et al., 2009 |

| Villin-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Bennecke et al., 2010 |

| Villin-Cre; KrasG12Dint | |

| Villin-Cre; KrasG12Dint;Ink4a/Arf−/− | |

| Villin-CreERT; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Apcfl/+;Ptenfl/fl | Davies et al., 2014 |

| AhCre; LSL-KrasV12/+ | Sansom et al., 2006 |

| AhCre; LSL-KrasV12/+, Apcfl/+ or fl/fl | |

| Fapbl-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Apc2lox14/+ | Haigis et al., 2008 |

| Fabpl-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Tuveson et al., 2004 |

| Ah-Cre;Apcfl/fl | Barker et al., 2009 |

| Lgr5-CreERT2;Apcfl/fl | Powell et al., 2012 |

| Lrig1-CreERT2;Apcfl/+ | Powell et al., 2014 |

GEMMs of Kras activation in the stomach

Gastric glands consist of multiple types of gastric cell lineages, such as mucin-secreting surface/foveolar cells or mucus neck cells, acid-secreting parietal cells, zymogen granule-secreting chief cells, and proliferating isthmal progenitor cells as well as endocrine cells and tuft cells79. In recent decades, a number of driver mouse models that induce Cre recombinase in gastric cell lineages have been generated, and many studies have been conducted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of Kras activation in gastric carcinogenesis by generating Cre recombinase-inducible Kras transgenic mouse alleles (Table 3). The first experimental insight into the role of oncogenic Kras in the gastric epithelium was from a study using the keratin 19 (K19) promoter to induce KrasV12 directly in the gastric epithelium by the Rustgi group80. K19 transcription was observed in the isthmal progenitor cell zone, and KrasV12 induction by K19 promoter activity resulted in mucous neck cell hyperplasia and parietal cell loss. A further study from the Wang group showed that K19-KrasV12 transgenic mice with Helicobacter felis bacterial infection showed parietal cell loss, metaplasia, and dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma was found in 38% of the mice by 16 months of age, concomitant with an early upregulation of CXCL1 and the recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells and fibroblasts81. In addition, a conditional LSL-KrasG12D mouse allele was introduced to induce Kras activation by the generation of a new inducible Cre driver mouse allele using the K19 gene locus82. The phenotype of this mouse allele included prominent foveolar hyperplasia, metaplasia, and adenomas in the stomach as well as in the oral cavity, colon, and lungs. Notably, only small numbers of mucinous metaplasias with characteristics of early-stage PanINs developed in the pancreas.

Table 3.

Genetically engineered mouse models of gastric cancer.

| GEMM | References |

|---|---|

| K19-Kras-V12 TG | Brembeck et al., 2003 |

| K19-Kras-V12 TG | Okumura et al., 2010 |

| K19-CreERT; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Ray et al., 2011 |

| Ubc9 Cre-ERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Matkar et al., 2011 |

| Mist1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Choi et al., 2016 |

| eR1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Matsuo et al., 2017 |

| Atp4b-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Cdh1fl/fl; Trp53fl/fl | Till et al., 2017 |

| Tff1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Kinoshita et al., 2019 |

| Tff1-Cre; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Ptenfl/fl | |

| Anxa10-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;LSL-Tp53R172H/+;Smad4fl/fl | Seidlitz et al., 2019 |

| Anxa10-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Cdh1fl/fl;Smad4fl/fl | |

| Anxa10-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Cdh1fl/fl;Apcfl/fl | |

| Lrig1-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Choi et al., 2019 |

| Iqgap3-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Matsuo et al., 2021 |

| Pgc-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Douchi et al., 2021 |

| Pgc-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Apcfl/fl | |

| Pgc-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+; Apcfl/fl;Trp53fl/+ or fl/fl | |

| Cldn18-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+ | Fatehullah et al., 2021 |

| Cldn18-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Apcfl/fl | |

| Cldn18-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Trp53fl/fl | |

| Cldn18-CreERT2; LSL-KrasG12D/+;Apc fl/+ or fl/fl;Trp53fl/fl |

The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 9 (Ubc9) gene is a small ubiquitin-like protein modifier (SUMO)-conjugating protein, and various cell types across tissues express this protein83. The Hua group crossed the Ubc9-CreERT driver mouse allele with LSL-KrasG12D mice to examine the effect of Kras activation in many organs, including GI tract organs84. The Ubc9-CreERT;LSL-KrasG12D mice started dying approximately 2 weeks after Kras induction but did not show any obvious tumor formation in the GI organs, such as pancreas, liver, small intestine, and colon, nor in the lungs and kidneys, except for one mouse showing oral papilloma. In the stomach tissue, the mice showed rapid changes and dramatic effects in both the forestomach and glandular stomach, severe inflammation, hyperplasia, and metaplasia were observed in the stomach without neoplasia. These results suggest that, among all the tissues in which Kras is activated, the stomach appears to be particularly susceptible to Kras activation at early time points; therefore, Kras activation may have crucial roles in the initiation of the carcinogenic process in the stomach. However, although KrasG12D GEMMs using these driver mouse alleles described above do display critical features of gastric carcinogenesis, they do not display all of the critical features seen in human patients with intestinal-type gastric cancer, and chronic inflammation by Helicobacter bacterial infection might be required to promote preneoplastic lesions to neoplastic stages.

GEMMs of Kras activation using gastric cell type-specific drivers

The study of Kras in the gastric cancer field was continued by multiple groups utilizing gastric cell type-specific driver mouse alleles, especially the genes specifically expressed in zymogen granule-secreting chief cells or proliferating-isthmal progenitor cells. The first study was performed using the Mist1-CreERT2 mouse allele to induce Kras activation in chief cells11. Constitutive Kras activation in chief cells led to pyloric metaplasia development only 1 month after active Kras expression. The pyloric metaplasia glands then progressed to intestinal metaplasia (IM) by 3 months and progressed to invasive glands at 4 months. Additionally, various metaplastic cell lineages in the glands were observed, including spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) lineages produced by chief cell transdifferentiation and TFF3-expressing intestinal-type metaplastic cells. Gastric chief cells also secrete pepsinogen C (Pgc), a member of the aspartic protease family85. The Ito group generated a Pgc-mCherry-IRES-CreERT2 knock-in mouse allele (Pgc-CreERT2) using the Pgc gene locus30. The Pgc transcriptional activity was predominantly observed in chief cells but also in some of the mucus neck cells and isthmal progenitor cells. While Pgc-CreERT2;LSL-KrasG12D mice showed pyloric metaplasia development only in the stomach corpus, mice with Apc and Trp53 deletion in addition to Kras activation developed invasive and metastatic carcinoma.

Several driver mouse alleles have also been generated to induce Kras activation in proliferating-isthmal progenitor cells using the eR1, Iqgap3, or Lrig1 gene locus28,36,86. These GEMMs developed a pyloric gland phenotype with a predominant expansion of the foveolar compartment rather than pyloric metaplasia with chief cell transdifferentiation, which is required for SPEM cell production.

GEMMs of Kras induction using other gastric cell-type driver mouse alleles

Other investigators have developed GEMM models of gastric cancer that allow Kras activation in other gastric cell types. Kras activation in pit cells and progenitor cells predominantly through Tff1-Cre drivers led to the development of gastric atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia87. Interestingly, KrasG12D expression combined with Cdh1 and Trp53 deletion in cells expressing the Atp4b gene gave rise to both intestinal- and diffuse-type tumors88. Additional driver mouse alleles, not specific for either stomach tissue or gastric cell types, have also been utilized to study gastric carcinogenesis. A gastric epithelium-specific CreERT2 mouse allele using the Anxa10 gene promoter (Anxa10-CreERT2)29, which is transcriptionally active throughout the stomach, showed tamoxifen-induced Cre recombination in all gastric cell types to model molecular subtypes of human gastric cancer, such as the CIN and GS subtypes43. In the CIN subtype, mutations in the Trp53, Kras, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathways are frequently observed43. Anxa10-CreERT2 mice with Kras activation, a mutant form of Trp53 (Trp53R172H), and Smad4 deletion developed invasive intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinomas that metastasized to the liver and lung. CDH1 mutations are frequently observed in the diffuse GS subtype43,89. Notably, the Anxa10-CreERT2 mice with Cdh1 and Smad4 deletion, simultaneously with Kras activation, developed poorly differentiated tumors with diffuse-type gastric cancer morphology, which was histologically characterized by signet ring cells. In contrast, the Anxa10-CreERT2 mice with Cdh1 and Apc deletion along with Kras activation developed only serrated adenomatous gastric cancer. In addition, the Barker group recently generated a mouse model for gastric cancer using the Claudin18-CreERT2 driver mouse allele to achieve conditional mutations selective to both pyloric and corpus region of gastric epithelia31. Claudin18-CreERT2 mice with Apc and Trp53 deletion as well as Kras activation developed tumors that displayed histology similar to human advanced gastric cancers with distant metastases31.

Conclusion and future perspectives

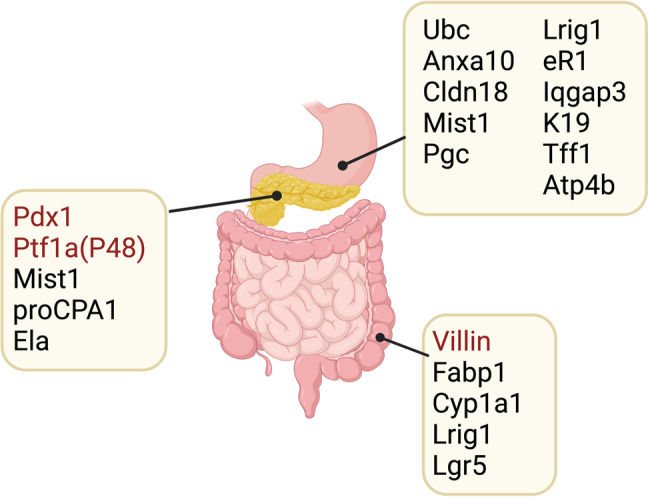

Numerous GEMMs have been generated for GI tract cancer research, especially for gastric cancer research, and used to study GI epithelial cell carcinogenesis (Fig. 1). Many of these GEMMs have also been utilized as in vivo preclinical models for identifying therapeutic targets and examining drug effects. While there are several major driver mouse alleles for studying carcinogenesis in the pancreatic and colorectal cancer fields, there are still no mouse models of gastric cancer that faithfully recapitulate the full spectrum of the Correa pathway, undergoing mucosal changes from a normal mucosa to gastritis, metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. This might be due to a lack of knowledge of a true cell of origin of gastric adenocarcinoma. Moreover, it is not clear whether Kras activation alone can lead to the full spectrum of gastric carcinogenesis, and other oncogenic gene activations are necessary for the full process or at least for the critical transition steps, preneoplastic metaplasia progression to neoplastic dysplasia or dysplasia evolution to adenocarcinoma. Notably, precancerous metaplasia, present not only in the stomach but also in the pancreas and colon, contains a common metaplastic cell population with features similar to SPEM cells90,91. This suggests that the metaplasia development induced by Kras activation is a generalized process that can at minimum lead to the initial step of carcinogenesis in GI organs. Therefore, defining the origin cell population of gastric cancer and establishing a novel driver mouse allele using gene loci specifically expressed in the origin cells would be critical for future gastric cancer research and for a better understanding of the roles of Kras activation during carcinogenesis.

Fig. 1. Driver genes used to express Kras.

Numerous driver mouse alleles have been used to induce Kras activation in gastrointestinal organs, including the stomach, pancreas, and colon. While several key driver genes, such as Pdx1 and Ptf1a (P48) in the pancreas and Villin in the colon, have been commonly utilized, no driver mouse models that can faithfully recapitulate the carcinogenic process are available in the gastric cancer field yet. The image was created with BioRender.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIH (R37CA244970, R01CA272687 and R01DK101332), the DOD (CA160479), and the AGA Research Foundation (AGA2022-32-01) to E.C.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McCance, K. L. & Huether, S. E. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults & Children 5th edn (Elsevier, 2006).

- 2.Arnold M, et al. Global burden of 5 major types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335–349.e315. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amieva M, Peek RM., Jr Pathobiology of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:64–78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu B, et al. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012;3:251–261. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554–3560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt PH, et al. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab. Invest. 1999;79:639–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer AR, Goldenring JR. Injury, repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J. Physiol. 2018;596:3861–3867. doi: 10.1113/JP275512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nam KT, et al. Mature chief cells are cryptic progenitors for metaplasia in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2028–2037.e2029. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldwell B, Meyer AR, Weis JA, Engevik AC, Choi E. Chief cell plasticity is the origin of metaplasia following acute injury in the stomach mucosa. Gut. 2022;71:1068–1077. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenring JR, Mills JC. Cellular plasticity, reprogramming, and regeneration: metaplasia in the stomach and beyond. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:415–430. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi E, Hendley AM, Bailey JM, Leach SD, Goldenring JR. Expression of activated ras in gastric chief cells of mice leads to the full spectrum of metaplastic lineage transitions. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:918–930.e913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wild CP, Hardie LJ. Reflux, Barrett’s oesophagus and adenocarcinoma: burning questions. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:676–684. doi: 10.1038/nrc1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh M, Maitra A. Precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer: molecular pathology and clinical implications. Pancreatology. 2007;7:9–19. doi: 10.1159/000101873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singhi AD, Wood LD. Early detection of pancreatic cancer using DNA-based molecular approaches. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:457–468. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maitra A, et al. Multicomponent analysis of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression model using a pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia tissue microarray. Mod. Pathol. 2003;16:902–912. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086072.56290.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janne PA, Mayer RJ. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:1960–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada Y, Mori H. Multistep carcinogenesis of the colon in Apc(Min/+) mouse. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2457–2467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigil D, Cherfils J, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Ras superfamily GEFs and GAPs: validated and tractable targets for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:842–857. doi: 10.1038/nrc2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox AD, Der CJ. Ras history: the saga continues. Small GTPases. 2010;1:2–27. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.1.1.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuchida N, Ryder T, Ohtsubo E. Nucleotide sequence of the oncogene encoding the p21 transforming protein of Kirsten murine sarcoma virus. Science. 1982;217:937–939. doi: 10.1126/science.6287573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eser S, Schnieke A, Schneider G, Saur D. Oncogenic KRAS signalling in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;111:817–822. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SH, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in stomach cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:6942–6945. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi E, Means AL, Coffey RJ, Goldenring JR. Active Kras expression in gastric isthmal progenitor cells induces foveolar hyperplasia but not metaplasia. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;7:251–253.e251. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidlitz T, et al. Mouse models of human gastric cancer subtypes with stomach-specific CreERT2-mediated pathway alterations. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1599–1614.e1592. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douchi D, et al. Induction of gastric cancer by successive oncogenic activation in the corpus. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1907–1923.e1926. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fatehullah A, et al. A tumour-resident Lgr5(+) stem-cell-like pool drives the establishment and progression of advanced gastric cancers. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2021;23:1299–1313. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gidekel Friedlander SY, et al. Context-dependent transformation of adult pancreatic cells by oncogenic K-Ras. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardeesy N, et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5947–5952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601273103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calcagno SR, et al. Oncogenic K-ras promotes early carcinogenesis in the mouse proximal colon. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:2462–2470. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuo J, et al. Identification of stem cells in the epithelium of the stomach corpus and antrum of mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:218–231.e214. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kersten K, de Visser KE, van Miltenburg MH, Jonkers J. Genetically engineered mouse models in oncology research and cancer medicine. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017;9:137–153. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gopinathan A, Morton JP, Jodrell DI, Sansom OJ. GEMMs as preclinical models for testing pancreatic cancer therapies. Dis. Model. Mech. 2015;8:1185–1200. doi: 10.1242/dmm.021055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drosten M, Guerra C, Barbacid M. Genetically engineered mouse models of K-Ras-driven lung and pancreatic tumors: validation of therapeutic targets. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018;8:a031542. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burtin F, Mullins CS, Linnebacher M. Mouse models of colorectal cancer: past, present and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1394–1426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i13.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liabeuf D, Oshima M, Stange DE, Sigal M. Stem cells, Helicobacter pylori, and mutational landscape: utility of preclinical models to understand carcinogenesis and to direct management of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1067–1087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and comprehensive molecular profiling identify new driver mutations in gastric cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:573–582. doi: 10.1038/ng.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei Z, et al. Identification of molecular subtypes of gastric cancer with different responses to PI3-kinase inhibitors and 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:554–565. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cristescu R, et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat. Med. 2015;21:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Setia N, et al. A protein and mRNA expression-based classification of gastric cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2016;29:772–784. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng N, et al. A comprehensive survey of genomic alterations in gastric cancer reveals systematic patterns of molecular exclusivity and co-occurrence among distinct therapeutic targets. Gut. 2012;61:673–684. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caldas C, et al. Frequent somatic mutations and homozygous deletions of the p16 (MTS1) gene in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:27–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redston MS, et al. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3025–3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurice D, et al. Loss of Smad4 function in pancreatic tumors: C-terminal truncation leads to decreased stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43175–43181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smit VT, et al. KRAS codon 12 mutations occur very frequently in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:7773–7782. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collisson EA, Bailey P, Chang DK, Biankin AV. Molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;16:207–220. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mouradov D, et al. Colorectal cancer cell lines are representative models of the main molecular subtypes of primary cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3238–3247. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aguirre AJ, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3112–3126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skoulidis F, et al. Germline Brca2 heterozygosity promotes Kras(G12D)-driven carcinogenesis in a murine model of familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morton JP, et al. LKB1 haploinsufficiency cooperates with Kras to promote pancreatic cancer through suppression of p21-dependent growth arrest. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:586–597. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ying H, et al. PTEN is a major tumor suppressor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and regulates an NF-kappaB-cytokine network. Cancer Disco. 2011;1:158–169. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whittle MC, et al. RUNX3 controls a metastatic switch in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell. 2015;161:1345–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ijichi H, et al. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3147–3160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1475506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Habbe N, et al. Spontaneous induction of murine pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPanIN) by acinar cell targeting of oncogenic Kras in adult mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:18913–18918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810097105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hingorani SR, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheung AF, et al. Complete deletion of Apc results in severe polyposis in mice. Oncogene. 2010;29:1857–1864. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robanus-Maandag EC, et al. A new conditional Apc-mutant mouse model for colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:946–952. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feng Y, et al. Sox9 induction, ectopic Paneth cells, and mitotic spindle axis defects in mouse colon adenomatous epithelium arising from conditional biallelic Apc inactivation. Am. J. Pathol. 2013;183:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sansom OJ, et al. Loss of Apc allows phenotypic manifestation of the transforming properties of an endogenous K-ras oncogene in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14122–14127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haigis KM, et al. Differential effects of oncogenic K-Ras and N-Ras on proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression in the colon. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ngXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.el Marjou F, et al. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis. 2004;39:186–193. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trobridge P, et al. TGF-beta receptor inactivation and mutant Kras induce intestinal neoplasms in mice via a beta-catenin-independent pathway. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1680–1688.e1687. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bennecke M, et al. Ink4a/Arf and oncogene-induced senescence prevent tumor progression during alternative colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davies EJ, Marsh Durban V, Meniel V, Williams GT, Clarke AR. PTEN loss and KRAS activation leads to the formation of serrated adenomas and metastatic carcinoma in the mouse intestine. J. Pathol. 2014;233:27–38. doi: 10.1002/path.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakai E, et al. Combined mutation of Apc, Kras, and Tgfbr2 effectively drives metastasis of intestinal cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78:1334–1346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saam JR, Gordon JI. Inducible gene knockouts in the small intestinal and colonic epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:38071–38082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tuveson DA, et al. Endogenous oncogenic K-ras(G12D) stimulates proliferation and widespread neoplastic and developmental defects. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:375–387. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ireland H, et al. Inducible Cre-mediated control of gene expression in the murine gastrointestinal tract: effect of loss of beta-catenin. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1236–1246. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barker N, et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powell AE, et al. The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell. 2012;149:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Powell AE, et al. Inducible loss of one Apc allele in Lrig1-expressing progenitor cells results in multiple distal colonic tumors with features of familial adenomatous polyposis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G16–G23. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00358.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choi E, et al. Cell lineage distribution atlas of the human stomach reveals heterogeneous gland populations in the gastric antrum. Gut. 2014;63:1711–1720. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brembeck FH, et al. The mutant K-ras oncogene causes pancreatic periductal lymphocytic infiltration and gastric mucous neck cell hyperplasia in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okumura T, et al. K-ras mutation targeted to gastric tissue progenitor cells results in chronic inflammation, an altered microenvironment, and progression to intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8435–8445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ray KC, et al. Epithelial tissues have varying degrees of susceptibility to Kras(G12D)-initiated tumorigenesis in a mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Matkar SS, et al. Systemic activation of K-ras rapidly induces gastric hyperplasia and metaplasia in mice. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2011;1:432–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shen S, Jiang J, Yuan Y. Pepsinogen C expression, regulation and its relationship with cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:57. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matsuo J, et al. Iqgap3-Ras axis drives stem cell proliferation in the stomach corpus during homoeostasis and repair. Gut. 2021;70:1833–1846. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kinoshita H, et al. Three types of metaplasia model through Kras activation, Pten deletion, or Cdh1 deletion in the gastric epithelium. J. Pathol. 2019;247:35–47. doi: 10.1002/path.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Till JE, et al. Oncogenic KRAS and p53 loss drive gastric tumorigenesis in mice that can be attenuated by E-cadherin expression. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5349–5359. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garcia-Pelaez J, Barbosa-Matos R, Gullo I, Carneiro F, Oliveira C. Histological and mutational profile of diffuse gastric cancer: current knowledge and future challenges. Mol. Oncol. 2021;15:2841–2867. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen B, et al. Differential pre-malignant programs and microenvironment chart distinct paths to malignancy in human colorectal polyps. Cell. 2021;184:6262–6280 e6226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ma Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals a conserved metaplasia program in pancreatic injury. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:604–620.e620. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]