To the Editor:

In CHEST (October 2022), Moskowitz et al1 describe a new outcome measure for clinical trials focusing on patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, the oxygen-free days,1 which are related to hospital discharge, an important patient outcome, and hospital length of stay, an important financial outcome. The authors acknowledged several limitations to this end point but may have missed several important confounders. These include the oxygenation target, skin pigmentation, and the type of oximeter used (Fig 1 ).

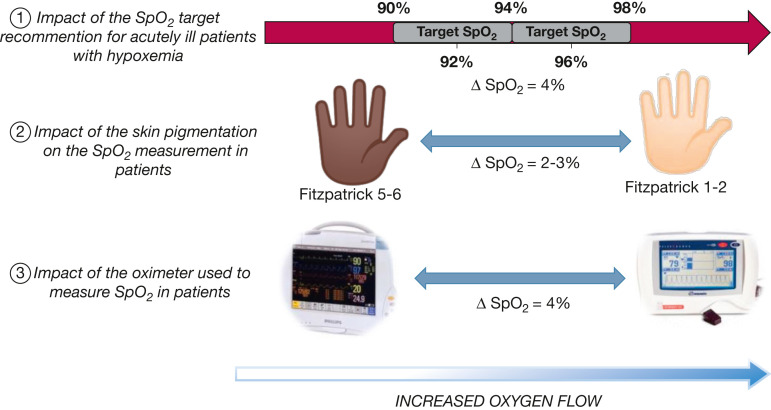

Figure 1.

Impact of several parameters on oxygen needs: Spo2 target, skin pigmentation, and type of oximeter used have an impact on the oxygen flow required, and potentially on oxygen therapy duration and associated factors, such as oxygen-free days and hospital length of stay. Extreme situations are presented: ① Spo2 target recommended by the British Thoracic Society (96% ± 2%)1 or the one in the rapid BMJ recommendations (92% ± 2%)2; ② Skin pigmentation for most pigmented (Fitzpatrick scale 5-6) and less pigmented subjects (Fitzpatrick scale 1-2); ③ Type of oximeter used, with those that overestimated Sao2 the most and those that underestimated Sao2 the most (https://openoximetry.org/oximeters). Sao2 = arterial oxygen saturation; Spo2 = oxygen saturation.

Knowledge regarding oxygen therapy has advanced markedly over the last 20 years, with risks associated with hyperoxemia in addition to those more intuitive risks associated with hypoxemia identified. Current recommendations in acutely ill patients, except COPD, suggest targeting an oxygenation range with a low and a high oxygen saturation (Spo 2) limit. In different guidelines, the recommended Spo 2 targets range from 96% ± 2% proposed by the British Thoracic Society2 to 92% ± 2% proposed by a Canadian group.3

In 36 hospitalized patients receiving oxygen therapy, targeting 96% rather than 92% Spo 2 resulted in a twofold increase in oxygen flow.4 Consequently, clearly for the same patient managed in London, England (recommended Spo 2 between 94% and 98%) or in London, Ontario (recommended Spo 2 between 90% and 94%, if Canadian suggestions are followed), the duration of oxygen therapy and likely hospital length of stay will increase, whereas oxygen-free days will be reduced in London, England.

Similarly, if the recommendation for the Spo 2 target is not adjusted for skin pigmentation, the same issue will present. In a patient with dark skin pigmentation, oxygen will be weaned more quickly, as pulse oximetry (Spo 2) overestimates arterial oxygen saturation (Sao2) by 2% to 3% compared with light pigmented subjects (Fig 1).5

Finally, recent data show that the type of oximeter used may even have a higher influence than skin pigmentation (Fig 1).

It is time to harmonize practices for oxygen management worldwide, and more complex guidelines should be used that take into account the skin pigmentation as well as the type of oximeter used. This is also true if oxygen-free days are used as a marker in clinical trials evaluating new treatments. Ignoring these parameters would have an important impact on this new proposed outcome.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: F. L. is co-founder, shareholder and director of Oxynov. This company has designed and marketed the automated oxygen adjustment system (FreeO2), but this device is not evoked in the letter. None declared (M. A. B., R. B.).

Footnotes

Editor's Note: Authors are invited to respond to Correspondence that cites their previously published work. Those responses appear after the related letter. In cases where there is no response, the author of the original article declined to respond or did not reply to our invitation.

References

- 1.Moskowitz A., Shotwell M.S., Gibbs K.W., et al. Oxygen-free days as an outcome measure in clinical trials of therapies for COVID-19 and other causes of new-onset hypoxemia. Chest. 2022;162(4):804–814. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.04.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Driscoll B.R., Howard L.S., Earis J., Mak V., British Thoracic Society Emergency Oxygen Guideline G, Group BTSEOGD BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Thorax. 2017;72(Suppl 1):ii1–ii90. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siemieniuk R.A.C., Chu D.K., Kim L.H., et al. Oxygen therapy for acutely ill medical patients: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;363:k4169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourassa S., Bouchard P.A., Dauphin M., Lellouche F. Oxygen conservation methods with automated titration. Respir Care. 2020;65(10):1433–1442. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjoding M.W., Dickson R.P., Iwashyna T.J., Gay S.E., Valley T.S. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2477–2478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2029240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]