Abstract

Purpose

Chemoradiation therapy is the primary treatment for anal cancer. Radiation therapy (RT) can weaken the pelvic bone structure, but the risk of pelvic insufficiency fractures (PIFs) and derived pain in anal cancer is not yet established. We determined the frequency of symptomatic PIFs after RT for anal cancer and related this to radiation dose to specific pelvic bone substructures.

Methods and Materials

In a prospective setting, patients treated with RT for anal cancer had magnetic resonance imaging 1 year after RT. PIFs were mapped to 17 different bone sites, and we constructed a guideline for detailed delineation of pelvic bone substructures. Patients were interviewed regarding pain and scored according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects. Dose-volume relationships for specific pelvic bone substructures and PIFs were determined for V20 to V40 Gy mean and maximum doses.

Results

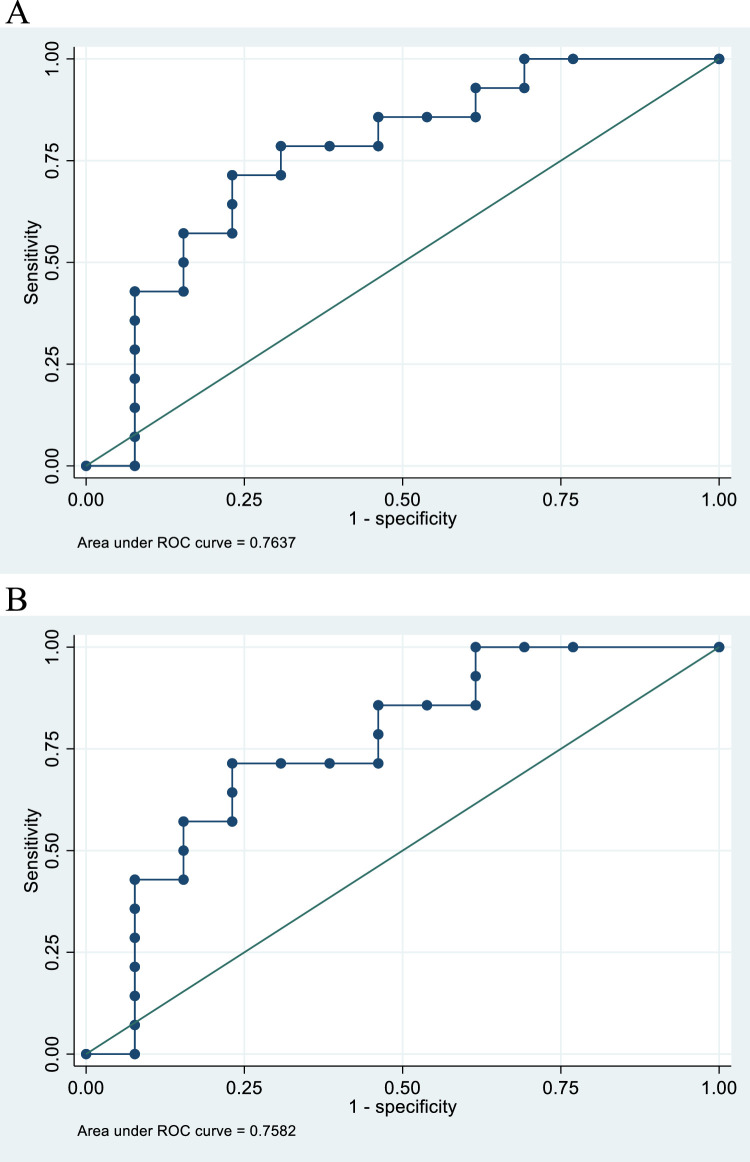

Twenty-seven patients were included, and 51.9% had PIFs primarily located in the alae of the sacral bone. Patients with PIFs had significantly more pelvic pain (86% vs 23%, P = .001) and 43% had grade 2 bone pain. Dose-volume parameters for sacral bone and sacral alae were significantly higher in patients with PIFs (P < .05). V30 Gy (%) for sacral bone and alae implied an area under the curve of 0.764 and 0.758, respectively, in receiver operating characteristic analyses.

Conclusions

We observed a high risk of PIFs in patients treated with RT for anal cancer 1 year after treatment. A significant proportion had pain in the sites where PIFs were most frequently found. Radiation dose to pelvic bone substructures revealed relation to risk of PIFs and can be used for plan optimization in future clinical trials.

Introduction

Pelvic radiation therapy (RT) is associated with adverse effects from adjacent healthy tissues, including pelvic pain, that can be caused by several mechanisms. Even though pelvic insufficiency fracture (PIF) is a well-known late complication to RT, the effect of RT on bone has been less in focus. Acknowledging PIF as a possible cause of pelvic pain is important as it can affect physical function and quality of life and necessitate specific imaging.1,2 Chemoradiation therapy (CRT) is the primary treatment for anal cancer, but PIFs are solely described in small retrospective or registry studies after RT for anal cancer in 1.4% to 14%.3, 4, 5 PIFs are more well described after RT for gynecologic malignancies but with varying frequency from 2% to 89%.6, 7, 8, 9

Studies on PIFs after RT are heterogeneous in definition of PIF, imaging method, and timing of imaging. Furthermore, studies are mainly retrospective, and many have no clinical information.7, 8, 9 Choice of imaging method is important, and for stress fractures in general, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is estimated to have a sensitivity of 99% to 100% and a specificity of 85%; also, MRI is found to be better than computed tomography (CT; sensitivity 69%) in the pelvic area.10, 11, 12

Across studies and cancer diagnoses, it has been documented that PIF are predominantly located in weight-bearing areas and have a relation to higher radiation doses with an increasing incidence with age and postmenopausal status.3,4,7,8,13,14 In gynecologic malignancies, 2 recent, large systematic reviews on PIF after RT found incidences of PIF of 9.4% and 14%, respectively, and detected a median of 8 to 39 months and 7.1 to 19 months, respectively, after RT. The most frequently found risk factors for PIF included increasing age, postmenopausal status, low body mass index, and osteoporosis. Further, the most frequent localizations were in the weight-bearing areas: sacral body/near sacroiliac joint (60%-73.6%) and pubic bones (12%-13%). There was an association of older RT treatment techniques and higher RT doses. The ratio of symptomatic patients differed but was generally around 50% to 60%.7,8 Due to different CRT, radiation dose, and technique, data from gynecologic malignancies are not directly comparable to anal cancer, but data corresponds to what has been found in anal cancer and other pelvic cancers.13,15

We have recently found a high incidence of PIF (around 30%) 3 years after RT for rectal cancer as well as relation to radiation dose to pelvic bone substructures, but we had limited information on symptoms16 The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of PIF on MRI with bone-specific sequences 1 year after CRT for anal cancer and to determine and grade symptomatic PIFs. Further, we aim to relate the radiation dose of pelvic bone substructures to the risk of PIF and provide guidelines for detailed delineation of pelvic bone substructures.

Methods and Materials

Patients

Patients with anal cancer undergoing CRT were included in a prospective trial registering acute and late toxicity. An amendment was made to the protocol to conduct this substudy, including a bone-specific pelvic MRI and blood samples 1 year after CRT. Approvals were done by the Regional Ethical Committee (1-10-72-79-16) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2012-58-0005). At the 1-year follow-up, patients were offered participation in this substudy. All patients gave written informed consent and were included in the substudy between 2018 and 2021. Clinical data were collected prospectively; however, pelvic bone substructure delineation was done retrospectively and not included in the planning process.

Treatment

Planning positron emission tomography CT and MRI were acquired in treatment (supine) position. Gross tumor volume was defined based on available imaging and clinical information. Clinical target volume (CTV) margins included a 5-mm margin to gross tumor volume and circumference of anal canal, a further 5-mm isotropic margin (10 mm for margin tumors), and a 5-mm (8 cranio-caudally) planning target volume margin (PTV). Patients were treated with different RT and CRT schedules: 54 to 64 Gy in 30 to 32 fractions (5 weekly) to tumor and pathologic lymph nodes, and 48 to 51.2 Gy in 30 to 32 fractions to elective nodal areas including presacral space, mesorectum, ischioanal space, bilateral internal, and external iliac and bilateral inguinal regions (modifications to elective areas were allowed on individual basis) as described by Ng et al,17 but the ischiorectal fossa was only included fully if tumor growth through the levator muscles was seen on diagnostic MRI and the inferior boarder of the inguinal spaces was below the minor trochanter. Cisplatin was given either weekly (40 mg/m2; n = 14) or on day 1 and 29 (70 mg/m2; n = 5) together with infusional fluorouracil (3200 mg/m2; n = 5) over 96 hours. Capecitabine (1700 mg/m2, twice a day) was given as monotherapy in case of intolerance to cisplatin (n = 3).

Rotational intensity modulated arc therapy was used for all patients, using 2 to 4 arcs. Dose coverage criteria were V95 = 100% and V95 >99% for CTV and PTV, respectively. Priority was as follows: CTV > PTV > bowel > bladder > other organs at risk.

MRI

The bone-specific MRIs were performed on 1.5T platforms with a standardized scanning protocol including a 4-mm sagittal short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) sequence and a 7-mm coronal T1 FSE of the bony pelvis and femoral heads.

High signal intensity changes in the bone marrow at the STIR sequence, indicating bone marrow edema, with accompanying subtle linear, low signal intensity changes at T1-weighted images were defined as presence PIF. STIR is the most sensitive sequence for the detection of bone marrow edema while the T1 images ensured precise anatomic mapping and confirmation of subtle fracture lines. As most patients had multiple fractures, fractures were divided into following 17 sites: femoral heads (left/right [L/R]), femoral neck (L/R), superior pubic ramus (L/R), inferior pubic ramus (L/R), pubic corpus (L/R), acetabulum (L/R), iliac bone near joint (L/R), alae of the sacrum (L/R), and midline of sacral bone.

All MRI examinations were evaluated by a consultant radiologist with subspecialization in pelvic MRI who was blinded to all clinical and para-clinical data with the exception of the pretherapeutic MRI.

Blood tests

At the time of bone-specific MRI, a blood sample was drawn and analyzed for factors potentially related to bone metabolism and risk of insufficiency fractures, including: plasma (p)-thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), p-parathyroid hormone (PTH), p-glucose, p-calcium, p-phosphate, p-albumin, blood (b)-hemoglobin, p-vitamin-D, b-leukocytes, b-thrombocytes, p-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), p-bilirubin, p-alanine aminotransferase (ALAT), p-alkaline phosphatase, p-creatinine, p-c reactive protein (CRP), p-follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), p-testosterone.

Assessment of pain

In the outpatient clinic or during telephone consultation patients were first asked if they had pain in the pelvic area. If patients answered yes, pain was scored according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects (version 5.0), bone pain grade 0 to 3. Further, the patients were asked to characterize pelvic pain as pain while resting, pain with physical activity (ie, walking), or pain with provocation (ie, applying pressure to the affected area) and to localize pain into sacral, symphysis, or hip areas.

Delineation

The following pelvic bone structures were delineated: pelvic bones (total: including ileum, ischium, pubic and sacral bone, outer contour was delineated), femoral heads L/R (from caput cranially including lesser trochanter caudally), and sacral bone (from s1 cranially to s5 caudally) outer contour including foramina when located in bone. Sacroiliac joints (L/R) delineated 1 cm to each side of the joint, where the sacrum and ilium bones forms the joint; the sacral alae (L/R) were delineated as the winged formation lateral to sacral body. The acetabulum (L/R) was delineated 15 mm cranially to the most cranial slice with femoral head and caudally to the fovea of the femoral head. Pubic bones (L/R) were contoured with the most cranial slice meeting the acetabulum and caudally to a horizontal line through the obturator foramen (in Appendix E1 we provide a more detailed description and depict bone substructure delineation). Delineations were done blinded to the clinical outcome.

Dose-volume parameters

We compared V20 Gy, V30 Gy, and V40 Gy mean and maximum doses from the pelvic bone substructures between patients with and without PIFs. V10 Gy was omitted as the rotational arc therapy gave all patients a similar low-dose bath. V50 Gy was also not used as it was very close to the reported maximum doses.

Statistics

Differences between patient groups with or without PIFs were evaluated by the Wilcoxon rank sum test, Fisher exact test (dose-volume parameters), or χ² test. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Nonparametric receiver operating characteristic analyses were used to evaluate the dosimetric parameters for prediction of the risk of PIF. Area under curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the best fit.

STATA statistical software (version 17.0; StataCorp) was used for analyses.

Results

We included 27 patients with a median age of 64 years (range, 43-74), 81.5% of whom were female. Baseline body mass index was 26 (range, 18.1-32.1), and all patients were in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0 or 1. Patient T stages were T1: 25.9%, T2: 51.9%, T3: 3.7%, and T4: 18.5%, and 18.5% of patients had lymph node N-positive disease. There were no significant differences in performance status, T stage, or N stage between patients with or without PIF. Most patients (81.5%) received radiation doses between 60 and 64 Gy, and 5 patients (18.5%) did not receive CRT. All of the patients were treated with 2, 3, or 4 arc rotational arc therapy technique, and there were no differences between groups in CRT, radiation dose, or treatment technique. There were significantly more women in the PIF group compared with the no PIF group (P = .01); otherwise, baseline characteristics were equally distributed between the 2 groups. Baseline characteristics and differences between patients with and without PIF are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline and treatment characteristics

| Variable | All patients (n = 27) | Patients with PIF (n = 14) | Patients without PIF (n = 13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 64 (43-74) | 62 (43-72) | 66 (45-74) | .63 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 22 (81.5) | 14 (100) | 8 (61.5) | .01 |

| Baseline BMI, median (range) | 26 (18.1-32.1) | 26.2 (19-29.5) | 25.3 (18.1-32.1) | .51 |

| Baseline PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 24 (96) | 14 (100) | 10 (91) | .25 |

| 1 | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (9) | |

| Clinical T stage, n (%) | .73 | |||

| T1 | 7 (25.9) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (23.1) | |

| T2 | 14 (51.9) | 7 (50.0) | 7 (53.9) | |

| T3 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | |

| T4 | 5 (18.5) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Tumor size (cm), median (range) | 2.9 (1-7) | 2.55 (1-6) | 3.0 (2-7) | .34 |

| Clinical N stage, n (%) | .37 | |||

| N0 | 22 (81.5) | 11 (78.6) | 11 (84.6) | |

| N1 | 4 (14.8) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.7) | |

| N2 | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | |

| N3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Radiation therapy, n (%) | .64 | |||

| 64 Gy | 17 (63) | 10 (71.4) | 7 (53.8) | |

| 60 Gy | 5 (18.5) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 54 Gy | 5 (18.5) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | .11 | |||

| Cisplatin and/or fluorouracil | 22 (81.5) | 13 (93) | 9 (69) | |

| None | 5 (18.5) | 1 (7) | 4 (31) | |

| Radiation therapy technique, n (%) | .11 | |||

| VMAT 2 arc | 7 (26) | 6 (43) | 1 (8) | |

| VMAT 3 arc | 17 (63) | 7 (50) | 10 (77) | |

| VMAT 4 arc | 3 (11) | 1 (7) | 2 (15) | |

| Pelvic pain (Y/N), Y, n (%) | 15 (55.5) | 12 (86) | 3 (23) | .001 |

| CTCAE bone pain, n (%) | .015 | |||

| Grade 0 | 13 (48) | 3 (21) | 10 (77) | |

| Grade 1 | 6 (22) | 5 (36) | 1 (8) | |

| Grade 2 | 8 (30) | 6 (43) | 2 (15) | |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects; PIF = pelvic insufficiency fracture; PS = performance status; VMAT = volumetric modulated arc therapy; Y/N = yes/no.

Fourteen patients (51.9%) had PIFs identified on the MRI. The MRIs were acquired a median of 482 days after initiation of RT (range, 363-756 days). A total number of 44 fracture sites (on average 3.14 sites per patient) were identified with the alae of the sacral bone (L/R) being the most frequent site (n = 20), followed by the acetabulum (L/R) (n = 11), iliac bone, near joint (L/R) (n = 4), pubic bones, all (n = 4), femoral neck/heads (L/R) (n = 4), and the body of the sacral bone (n = 1). All but 1 patient had fractures in the sacral alae, uni- or bilaterally.

In the group of patients with no PIF, 3 patients had pain in the pelvic area (23%), whereas 12 of the patients (86%) with PIF had pain in the pelvic area (P = .001). When grading according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects bone pain, we found that significantly more patients had grade 1 and 2 pain (P = .015). Patients with PIF characterized pain as pain while resting (n = 5), pain with exercise (n = 8), and pain with provocation (n = 6). Localizing pain, 9 had pain in the sacral area, 7 in the hip area, and 1 in the symphyseal area.

None of the blood tests (p-TSH, p-PTH, p-glucose, p-calcium, p-phosphate, p-albumin, b-hemoglobin, p-vitamin-D, b-leukocytes, b-thrombocytes, p-LDH, p-bilirubin, p-ALAT, p-alkaline phosphatase, p-creatinine, p-CRP, p-FSH, p-testosterone) differed between patients with or without PIF.

Dose-volume parameters for the delineated bone substructures were compared between patients with without PIF. The full data set of dose-volume parameters can be seen in Table E1. The largest differences were seen between the sacral bone/sacral alae, and as these were the primary sites for PIF (and all but 1 patient had PIFs in sacral alae), these subvolumes were used for further analyses (Table 2). For sacral bone and sacral alae (mean dose L/R) all the evaluated dose-volume parameters (maximum dose [Gy], mean dose [Gy], V20 Gy [%], V30 Gy [%], and V40 Gy [%]) were significantly higher in patients who subsequently developed PIFs. In Fig. 1, this is exemplified by box plots for sacral bone V30 Gy (%), sacral alae V30 Gy (%), sacral bone V20 Gy (%), and sacral alae V20 Gy (%). P values were .019, .022, .038, and .030, respectively. Looking at the receiver operating characteristic curves for sacral bone V30 Gy (%) and sacral alae (mean of L/R) V30 Gy (%), the AUC were similar, 0.764 and 0.758 respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Dose-volume relationships for sacral bone and substructures

| Variable | All patients (n = 27),median (IQR) | Patients with PIF (n = 14), median (IQR) | Patients without PIF (n = 13), median (IQR) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sacral bone | ||||

| Max dose (Gy) | 52.8 (51.1-54.9) | 54.2 (52.8-55.1) | 51.8 (50.1-52.8) | .014 |

| Mean dose (Gy) | 36.8 (34.5-40.9) | 39.4 (36.1-41.7) | 35.1 (31.6-37.4) | .044 |

| V20 Gy (%) | 87.9 (77.7-91) | 90 (84.1-96.3) | 79.1 (74.6-88.6) | .038 |

| V30 Gy (%) | 73.6 (68-82.7) | 81.8 (73.5-84.1) | 69.6 (60.9-73.6) | .019 |

| V40 Gy (%) | 52.3 (46.5-61.4) | 59.4 (49.9-64.4) | 49.8 (35.9-58.5) | .048 |

| Sacral alae (mean left/right) | ||||

| Max dose (Gy) | 51.9 (50.3-53.1) | 52.9 (50.9-53.8) | 51.1 (49.8-51.9) | .016 |

| Mean dose (Gy) | 36.3 (34-40) | 38.4 (35.1-42.2) | 34.5 (26.2-36.3) | .026 |

| V20 Gy (%) | 87.9 (77-91.7) | 90.6 (85.9-96.8) | 78.7 (61-88.4) | .030 |

| V30 Gy (%) | 75.5 (67-84.5) | 81.2 (75-89.2) | 68.6 (43.8-75.5) | .022 |

| V40 Gy (%) | 50.3 (40.1-63.5) | 52.2 (49.2-64.5) | 44.2 (22.1-51.6) | .030 |

| Sacroiliac joints (mean left/right) | ||||

| Max dose (Gy) | 52.3 (49.9-53.5) | 52.5 (50.1-53.6) | 51.7 (49.8-52.4) | .10 |

| Mean dose (Gy) | 32.1 (29.3-36) | 32.5 (31-37.7) | 29.9 (19.8-33.4) | .08 |

| V20 Gy (%) | 78.6 (68.8-88.6) | 82.7 (74.5-95.3) | 73.2 (42.9-87.9) | .09 |

| V30 Gy (%) | 60.8 (55-72.8) | 61.0 (58.5-76.8) | 60.4 (28.1-68.3) | .17 |

| V40 Gy (%) | 32.3 (23.3-42.7) | 35.4 (30.9-43.7) | 29.9 (10.9-34.1) | .09 |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; PIF = pelvic insufficiency fracture.

Figure 1.

Box plots showing median, interquartile range, range, and outliers for patients without and with pelvic insufficiency fractures (PIF). Sacral bone V20 Gy (%) (green), os sacrum V30 Gy (%) (blue), sacral alae V20 Gy (%) (orange), and sacral alae V30 Gy (%) (red) are shown. All are significantly higher in patients who developed PIF.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of all patients. (A) V30 Gy (%) to the sacral bone as a predictor of pelvic insufficiency fractures (area under curve = 0.7637). (B) V30 Gy (%) to the alae of the sacral bone (mean of left and right) as a predictor of pelvic insufficiency fractures (area under curve = 0.7582).

Discussion

In this prospective study we found a high frequency of MRI identified PIFs at a median of 14 months after RT for anal cancer. We found that a large fraction of patients had pain in the pelvic bones that could be related to the sites where PIFs were most frequently found.

We are the first to provide a detailed suggestion for pelvic bone substructure delineation and relate RT dose-volume parameters to these substructures and the risk of PIF.

Only a few studies have investigated PIF after RT for anal cancer either separately or combined with other pelvic tumors in larger registry studies. The frequency of PIF in anal cancer has been found in up to 14% in these studies. All are retrospective studies, with varying imaging modality or based on registries and with no coinciding information on symptoms.3, 4, 5,13,14,18, 19, 20, 21, 22

Pelvic pain is a well-known late effect after pelvic RT,23 and PIF might be overlooked if the correct imaging protocol is not applied.

We used MRI in a prospective setup, with sequences and extent that were intended to detect PIF, and a dedicated magnetic resonance radiologist reviewed all scans. This could explain, in part, why we found such a high frequency compared with previously published studies on anal cancer referenced previously. It is, however, in the range of what has been seen after RT for cervical cancer.7,8 MRI compared with CT and bone scans has both higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting insufficiency fractures in general10,11,24 and specifically related to detection (higher incidence) of PIF RT for cervical cancer.9 MRI should thus be the preferred imaging modality if insufficiency fractures are suspected.12 The natural course for development and resolution of PIFs after RT for anal cancer is not known. A recent report on PIFs after RT for gynecologic malignancies showed that 93% of PIFs were detected within 1 year and that only 16.3% resolved at varying time points within the follow-up period (median, 12 months; range, 2-47 months).25 Two large reviews also in gynecologic cancer showed median time to detection from 8 to 39 months and 7.1 to 19 months, respectively.7,8 Thus we assume that the timeframe (1-2 years) used in our study reveals the majority of fractures.

More than 80% of patients with PIF had pelvic pain, and most were classified as grade 1 or 2 bone pain. Pelvic pain could be caused by other mechanisms; therefore, a definitive relation between pain and PIFs cannot be ensured. However, no patients had pelvic recurrence as a cause of pain, and PIFs were located in the areas where PIF were most frequently seen. Across studies, around 50% to 60% of patients with PIF had pain located in areas with high frequency of PIFs (lower back, hips, groin, or pelvis).7,8 In this study, the frequency was higher, which could be caused by bias of the patients having knowledge of PIFs in the recent scan or because patients with pain could be more prone to accept participation in the study. On the other hand, and even though not quantified, the primary response of some patients to “Do you have pain in the pelvic area?” was “No, but I cannot sleep on my left side due to pain,” or “No, but I cannot sit on a normal chair.” These patients were classified as having pain, and only caught by the study specific interview, which indicate that the frequency of pain might be underestimated in other studies.

Localization of PIFs in weight-bearing areas is in accordance with what has been found in other studies.2 We found several radiation dose levels to be associated with increased risk of PIF for both sacral bone, alae of the sacral bone, and sacroiliac joints, with the most pronounced difference for V30 Gy. This corresponds well to what we have previously found in rectal cancer, where we reported that V30 Gy to the sacroiliac joint differed between patients with and without PIF.16 In a study by Mir et al25 on patients with gynecologic cancer, the authors found all PIFs in the alae of the sacral bone (median 2 per patient). They investigated sacral bone dose (V15-V60 Gy) and found especially V40 Gy correlated to risk of PIFs. Also in gynecologic patients, a dose effect curve for PIFs showed that a reduction of radiation dose (D50% from 40 GyEquivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions to 35 GyEquivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions) decreased risk of PIF from 45% to 22%.26 Others have found higher doses (50.4 Gy) related to risk of PIF in gynecologic cancers.2 Pathophysiological studies also indicate changes in osteoblast function with doses around 30 Gy and cell death around 50 Gy.2 A high radiation dose (up to 64 Gy to the primary tumor) has previously been standard at our institution27 and applied to a proportion of patients in this trial. However, the maximal dose given to the sacral bone was <55 Gy, corresponding to the elective dose range, which is within the range of a standard radiation dose.28 The extent of the elective irradiated volumes is also within the standard for anal cancer.29 Studies on recurrences have suggested that the superior boarder of the elective volume can be lowered in low-risk patients, which would decrease radiation dose to sacral bone and sacral alae and probably the risk of PIF.30 Treatment technique could also affect the risk of PIF. Studies have shown decreased risk of PIF with IMRT compared with older techniques.8 Even though highly speculative rotational arc therapy, as used in this study, results in a low-dose bath to the pelvic bones that could affect bone structure more widespread and thereby impact risk of PIF negatively. Due to the limited number of patients included, and the fact that all but 1 patient had insufficiency fractures in the alae of the sacral bone, we chose to focus on the dose-volume relationships in these subvolumes, and we found that the AUC for the alae of the sacral bone was similar to that of the full sacral bone, implying that focus could be confined to these substructures in the treatment plan process and optimization. A limitation to this study is the low number of included patients; therefore, statistical significance should be interpreted with caution. However, based on the high frequency of PIF and relation to specific dose-volume parameters, we decided to initiate a prospective trial to explore the potential of bone-sparing, optimized RT for reducing the frequency of PIF in anal cancer patients. This phase 2 trial has incorporated constraints and priority to pelvic bone substructures in a 2-step planning process, with 1-year frequency of PIF as the primary end-point. We and others have already described that bone-sparing RT is possible when incorporated into the dose planning process in retrospective planning studies,16,31 but until now it has not been implemented in prospective clinical studies. Here we provide a delineation guideline for pelvic bone substructures used in this study and illustrations to support this.

Conclusion

A high proportion of patients treated with RT for anal cancer had radiologically confirmed PIFs approximately 1 year after treatment detected by MRI. A significant proportion of the patients had pelvic pain in the sites were PIFs were most frequently found.

Detailed delineation of pelvic bone substructures revealed relation of specific dose-volume parameters to the risk of PIF and can be used for plan optimization in future clinical trials.

Footnotes

Sources of support: The study was founded by Radiumstationens forskningsfond and A. P. Møller fonden.

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Research data are not available at this time.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2022.101110.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Higham CE, health Faithfull S.Bone, radiotherapy pelvic. Clin Oncol. 2015;27:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh D, Huh SJ, Nam H, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fracture after pelvic radiotherapy for cervical cancer: Analysis of risk factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomaszewski JM, Link E, Leong T, et al. Twenty-five-year experience with radical chemoradiation for anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Tepper JE, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Risk of pelvic fractures in older women following pelvic irradiation. JAMA. 2005;294:2587–2593. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.20.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitzthum LK, Park H, Zakeri K, et al. Risk of pelvic fracture with radiation therapy in older patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon JW, Huh SJ, Yoon YC, et al. Pelvic bone complications after radiation therapy of uterine cervical cancer: Evaluation with MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:987–994. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razavian N, Laucis A, Sun Y, et al. Radiation-induced insufficiency fractures after pelvic irradiation for gynecologic malignancies: A systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:620–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapienza LG, Salcedo MP, Ning MS, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fractures after external beam radiation therapy for gynecologic cancers: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of 3929 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung YK, Lee YK, Yoon BH, Suh DH, Koo KH. Pelvic insufficiency fractures in cervical cancer after radiation therapy: A meta-analysis and review. In Vivo. 2021;35:1109–1115. doi: 10.21873/invivo.12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabarrus MC, Ambekar A, Lu Y, Link TM. MRI and CT of insufficiency fractures of the pelvis and the proximal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:995–1001. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matcuk GR, Jr, Mahanty SR, Skalski MR, Patel DB, White EA, Gottsegen CJ. Stress fractures: Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2016;23:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s10140-016-1390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas S, Mikkelsen AH, Kronborg C, et al. Management of late adverse effects after chemoradiation for anal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2021;60:1688–1701. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2021.1983208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazire L, Xu H, Foy JP, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fracture (PIF) incidence in patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for gynaecological or anal cancer: Single-institution experience and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 2017;90 doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Francesco I, Thomas K, Wedlake L, Tait D. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy and anal cancer: Clinical outcome and late toxicity assessment. Clin Oncol. 2016;28:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen JB, Bondeven P, Iversen LH, Laurberg S, Pedersen BG. Pelvic insufficiency fractures frequently occur following preoperative chemo-radiotherapy for rectal cancer - A nationwide MRI study. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:873–880. doi: 10.1111/codi.14224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronborg Camilla, Jorgensen, J.B.B. Petersen, L. Nyvang Jensen, L.H. Iversen, B.G. Pedersen, K.G. Spindler Pelvic insufficiency fractures, dose volume parameters and plan optimization after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2019:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng Michael, Trevor Leong, Sarat Chander, Julie Chu, Andrew Kneebone, Susan Carroll, Kirsty Wiltshire, Samuel Ngan, Lisa Kachnic Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group (AGITG) contouring atlas and planning guidelines for intensity-modulated radiotherapy in anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myerson RJ, Outlaw ED, Chang A, et al. Radiotherapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus: Thirty years' experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okoukoni C, Randolph DM, McTyre ER, et al. Early dose-dependent cortical thinning of the femoral neck in anal cancer patients treated with pelvic radiation therapy. Bone. 2017;94:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan S, Rowbottom L, McDonald R, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fractures in women following radiation treatment: A case series. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5:233–237. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.05.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epps HR, Brinker MR, O'Connor DP. Bilateral femoral neck fractures after pelvic irradiation. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:457–460. discussion 460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serkies K, Bednaruk-Mlynski E, Dziadziuszko R, Jassem J. Conservative treatment for carcinoma of the anus—A report of 35 patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50:152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderas EH, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: Late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:736–744. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong X, Li J, Zhang L, et al. Characterization of insufficiency fracture and bone metastasis after radiotherapy in patients with cervical cancer detected by bone scan: Role of magnetic resonance imaging. Front Oncol. 2019;9:183. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mir R, Dragan AD, Mistry HB, Tsang YM, Padhani AR, Hoskin P. Sacral insufficiency fracture following pelvic radiotherapy in gynaecological malignancies: Development of a predictive model. Clin Oncol. 2021;33:e101–e109. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramlov A, Pedersen EM, Rohl L, et al. Risk factors for pelvic insufficiency fractures in locally advanced cervical cancer following intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leon O, M. Guren, O. Hagberg, B. Glimelius, O. Dahl, H. Havsteen, G. Naucler, C. Svensson, K.M. Tveit, A. Jakobsen, P. Pfeiffer, E. Wanderas, T. Ekman, B. Lindh, L. Balteskard, G. Frykholm, A. Johnsson Anal carcinoma - Survival and recurrence in a large cohort of patients treated according to Nordic guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2014:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao S, Guren MG, Khan K, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1087–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myerson RJ, Garofalo MC, El Naqa I, et al. Elective clinical target volumes for conformal therapy in anorectal cancer: A radiation therapy oncology group consensus panel contouring atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:824–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson SR, Lee ISY, Carroll S, et al. Radiotherapy for anal squamous cell carcinoma: Must the upper pelvic nodes and the inguinal nodes be treated? ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:870–875. doi: 10.1111/ans.14398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Q, Cai S, Qian J, Tian Y. Dose optimization strategy of sacrum limitation in cervical cancer intensity modulation radiation therapy planning. Med. 2019;98:e15938. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.