Abstract

Introduction

Shoulder arthroplasty is uncommon but increasing in number when compared to hip and knee arthroplasty. The average UK shoulder surgeon performs less than 10 a year and revision surgery is even more rare. The surgeon should be familiar with surgical approaches, implant designs and preferably be fellowship trained to produce good outcomes.

Methods

Narrative review was undertaken and senior author's personal practice was discussed.

Results

The need for a clear understanding of indications and contraindications for both anatomic shoulder arthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, good preoperative planning, protocol-based peri-operative management and good rehabilitation protocol in the post operative period cannot be overemphasized.

Conclusion

We are still learning best practice and prosthesis designs have changed over the past years with extensive choices especially in Reverse arthroplasty. Each of these designs has unique biomechanical properties and require a deep understanding of indications. Good surgical training and the use of multi-disciplinary team meetings for complex cases should improve the safety and quality of surgery for patients and ultimately long-term outcome of shoulder arthroplasty.

1. Best practice in shoulder arthroplasty-a reflective personal review

Shoulder arthroplasty is now well established as an effective procedure for end stage arthritis of the gleno-humeral joint. Traditional anatomic total shoulder replacement (aTSR) has been supplemented the past 10–15 years with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSR) which allows surgery where concern exists about the integrity and function of the rotator cuff tendons and muscles. rTSR has shown an upward trend in the last decade and this is confirmed in the various joint registries.1 By altering the mechanics of the prosthesis excellent function can be achieved in more challenging scenarios of soft tissue and bone loss sometimes with the addition of tendon transfer, bone grafting or the use of specialist ‘augmented” implants. For many surgeons it has become primary option in complex primary arthroplasty with glenoid bone loss.2

The basics of good arthroplasty practice apply to shoulders just as it has done for the more common hip and knee arthroplasty and the shoulder surgeons can certainly learn from their lower limb colleagues. However, the shoulder has unique and particular challenges that the surgeon should be aware of before embarking on arthroplasty. In this article we discuss these challenges and reflect on the experience of the senior author (CPK) over the past 30 years of practice. It is obvious that patients benefit greatly from well-trained surgeons who have completed Shoulder Fellowships in Units where the opportunity of seeing high volume is available.

-

1.

Choosing the right patient for surgery

It may seem obvious that patients with severe shoulder gleno-humeral arthritis should be offered arthroplasty. However, several factors determine success and failure with this surgery. Many patients who are elderly can tolerate an arthritic shoulder especially if they have good pain free function on the other side. The degree of symptoms does not always match the severity of change on the x-ray, and medical issues and comorbidity can influence decisions on surgery. Other priorities for the patient such as arthritis in other joints of the hip and knee may dominate the pain profile and often shoulder arthroplasty should take a back seat at times. Conservative treatment to maintain pain free movement with gentle exercises, analgesia, activity modification and the judicious use of steroid injections may be appropriate. Steroids should probably not be used if Arthroplasty is planned within a six-month period as there is conflicting evidence on its efficacy.3 Certainly, all precautions in using a sterile technique when injecting is critical in prevention of infection. In a small number of cases repeat injections may be indicated including other pain-relieving measures such as supra scapular nerve blocks. If a decision not to operate is made the surgeon should ensure proper referral to pain services. Other obvious contra-indications to arthroplasty would include active infection and inability to comply with relative immobilization and rehabilitation. Joint preservation surgery is preferable for patients younger than 55–60 years or those with early-stage degenerative joint disease of the shoulder. The operative procedure should match the patient's symptoms or functional limitations. Arthroscopic debridement, capsular release, corrective osteotomies, and interposition arthroplasty are surgical options that attempt to reduce symptoms while preserving the native joint.4

Major contraindications to shoulder replacement are: active or recent infection, neuropathic joint, complete paralysis of deltoid or rotator cuff muscles, debilitating medical status, or un-correctable shoulder instability.

Quality information and informed consent is mandatory. The use of videos and paper-based information has now been supplemented with various mobile phone and online applications that can monitor pain progression and also provide feedback to patients before and after surgery.5

-

2.

Investigating shoulder arthroplasty patients.

Traditionally, patient had standard x-rays (AP and axillary) and clinical assessment of muscle function. However, in recent years most surgeons request more scans to better define bone quality and bone loss and also rotator cuff integrity. MRI scan should be done to assess the integrity of rotator cuff in the patient who might be a candidate for anatomical TSR. Poor quality x-rays can cause errors in particular in relation to glenoid orientation. Many patients are stiff and sore and cannot tolerate standard axillary lateral views. Transthoracic or sagittal view are rarely useful and the author often requests Modified lateral views (eg. Nottingham or Stryker views). If in doubt a CT scan of the shoulder including the scapula should be requested.6

In order to import these scans into a software planning system it is useful to have a “shoulder arthroplasty protocol” for radiographers that complies with the various options. As well as planning for surgery the software can facilitate the production of custom guides and even custom implants in the rare cases of bone loss and mal-orientation of the glenoid. These patient specific instruments (PSI) are increasing in popularity and along with developments in real time navigation and virtual reality allows better surgery in complex cases.7 Even in standard cases software planning can be very useful in analysis of orientation of implants which should produce better functioning and durable arthroplasty.8,9

-

3.

Choosing the right operation

One of the most critical decisions for surgeons is to decide whether patients are suitable for anatomic or reverse arthroplasty. Anatomic arthroplasty allows reconstruction of the normal anatomy in the presence of intact and functioning rotator cuff muscles. It remains the preferred option in younger and fit patients whose bone and muscle are in good condition. This is generally those cases with primary osteoarthritis and some cases of inflammatory arthritis. Anatomic TSR should not be implanted when the soft tissues are no longer reparable or there is a severe glenoid deficiency, due to degenerative pathologies, trauma or previous surgery.10 Reverse arthroplasty in combination with glenoid bone grafting appears to be the recent option of choice for in severe glenoid deficiency rather than anatomic implants even in the presence of intact cuff muscles. The author (CPK)would encourage MDT discussion on these difficult cases.

However, rTSR has emerged as the preferred surgical option for cuff arthropathy and proximal humeral fractures.11

Additionally, there is an increasing variety of published indications for rTSA that now include but are not limited to: acute and delayed proximal humeral fractures12; rheumatoid arthritis; fracture malunion and non-union; tumour; fixed glenohumeral dislocation13; and severe glenoid bone loss.14

In complex primary cases and all revision cases, we encourage the use of shoulder Multidisciplinary meetings (MDT). These can take the form of virtual clinics and/or face to face “Complex Clinics”. The frequency of these resource heavy meeting varies however for arthroplasty we recommend at least a monthly meeting. In places where the volume of surgery is low then regional MDT and even supra regional may be appropriate. In the absence of MDT “second opinions” from local or regional colleagues in bigger centres should be sought especially for complex primary and revision cases. In the authors experience failure of implants is often associated with poor pre operative planning.

-

4.

Theatre set up

The surgery complex must have an appropriate range of implants for anatomic and reverse procedures. At times special custom implants and autograft or allograft bone may be needed after discussion at MDT and there may be delays of weeks and sometimes months before these implants are available. Proper planning and scheduling of these cases is important to avoid late cancellation and close liaison with the surgical team and the implant company is imperative. In most cases the Company representative will need to be in theatre at the case and in some circumstances scrubbed with the team depending on National regulations of this activity.

Training and education of all staff is a pre requisite to efficient and safe surgery and surgeons should work closely with managers and staff to help provide support and continual education. A unit approach to surgical preferences, prepping and draping, implant choice and rehabilitation helps to standardise practice and may reduce error and serious untoward events.

-

5.

Surgical approach

The choice is usually between a traditional deltopectoral (DP) approach or anterosuperior approach (trans deltoid, TD) that was first described by Mackenzie in 1993.15 Both have advantages and disadvantages and exposure and risk to local nerve and vessels are the critical factors. The DP approach has advantages. Inter-nervous plane minimizes risk of denervation, less bleeding as being in between the muscles, extensile and can be extended distally to anterolateral approach giving access to humeral shaft. Lastly, approaching the glenohumeral joint from the front allows for easier access to the inferior structures, including the inferior humeral osteophytes and the inferior capsule.16 Also, positioning of glenoid component is easier as inferior part of glenoid is more readily approachable. Disadvantages include a) Failure of subscapularis tendon healing leading to anterior instability in aTSR, b) difficulty in reaching posterior structures including capsule, posterior glenoid and cuff. Lynch et al. found that utilizing the deltopectoral approach was an independent risk factor for neurologic complications in total shoulder arthroplasty.17

The advantages of the TD approach are possible subscapularis sparing, better exposure of posterior glenoid and rotator cuff, better visualization and preparation of glenoid especially in obese patients and in cases with severe retroversion.18

Disadvantages include inadequate access to inferior part of glenoid, difficulty in achieving inferior tilt of gleno-sphere that might lead to scapular notching and also deltoid dysfunction may arise due to failure of healing. The presence of inferior osteophytes is a relative contraindication due to difficulty in accessing and removing these through a TD approach. The non-extensile nature of this approach also makes it less appealing to many surgeons.

The senior author (CPK) favours the DP approach as it is a natural inter-nervous plane allows better access for capsulectomy and secure repair of sub scapularis. Occasionally an extended approach involving clavicle osteotomy has been used, as described and popularized by the team at Nottingham UK.19

The very stiff shoulder can present a surgical challenge. Lack of external rotation or fixed internal rotation should alert the surgeon to possible posterior subluxation (B2 or B3 glenoid deformity) or large postero-inferior osteophytes. This can be seen on x-rays and CT scans at pre-op planning. Small patients can have tight shoulders where standard retractors seem too big. Larger male patients may have big muscles and along with any posterior subluxation, glenoid exposure can be difficult. This situation should be planned for in advance and the senior author sometimes performs lesser tuberosity osteotomy with early removal of blocking osteophytes to enable dislocation. Clavicular osteotomy as previously described19 may be necessary and the use of patient specific guides helps glenoid preparation. In a small number of cases despite best efforts adequate exposure of the glenoid is not possible to safely insert an anatomic glenoid component and the surgeon may need to consider hemi arthroplasty possibly with bony glenoid re-shaping (eccentric reaming).

-

6.

Choosing the right prosthesis.

There is an increasing range of implants available for shoulder arthroplasty. Many companies offer a wide range for primary anatomic, reverse and complex bone loss cases. Good training in each implant requires the surgeon to do workshops, cadaveric dissection and visits to skilled and knowledgeable surgeons before embarking on using a new implant. Specialist arthroplasty Fellowship training programmes can also help surgeons familiarise with the tips and tricks of each implant and the authors strongly recommend this approach. Surgeons in each unit should work together with managers to agree on protocols and implant choice taking into account published data and cost effectiveness. Rarely, there will be indications to use custom made implants.

-

7.

Preventing the Infection.

The biggest disaster in arthroplasty is infection which often commits the patients to multiple surgeries and poor outcome. Any identifiable infection example-teeth, urinary tract or chest must be controlled before surgery. Avoidance of invasive dental work close to surgery is to be avoided and there still remains controversy around the use of prophylactic antibiotics for dental work if a prosthesis is in situ. Standard decolonization protocols from our hip and knee colleagues have decreased the acute post-operative infection risk to less than 1%.20 By identifying at risk populations anti-MRSA precautions including intranasal antibiotics and anti-bacterial soaps for pre-surgical skin preparation have reduced the incidence of staphylococcus infections.20

Every effort should be made in the perioperative period to minimize this complication with meticulous protocols on prepping and draping, pre operative antibiotics, regular saline wash outs. After skin incision the surgeon should use a new blade for deep dissection. A troublesome bacterium in shoulder surgery that is associated with sub-acute infection is Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Proprionibacterium acnes). There is much publication about control of this infection and hydrogen peroxide wash outs during surgery may be beneficial.21 Recently, pre-operative skin cleansing with 5% benzoyl peroxide to reduce infection risk with c. acnes has emerged that can be amalgamated into shoulder arthroplasty surgeon's practice for reducing the risk of infection further.22

-

8.

Preventing dislocation

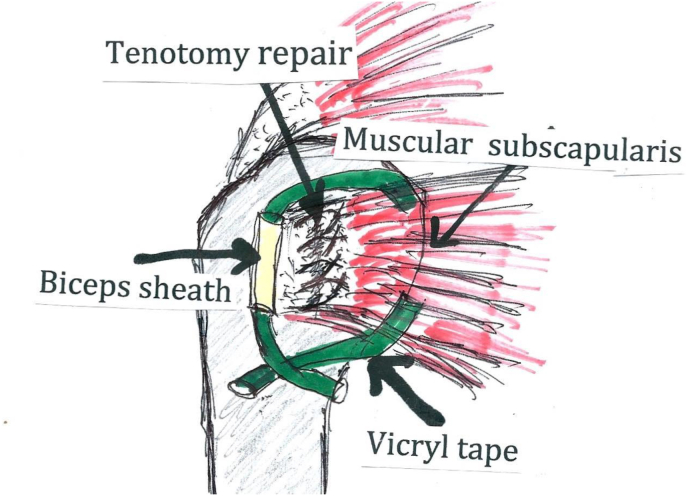

Early dislocation of a prosthesis is usually associated with surgical error such as poor orientation of implants or inadequate soft tissue releases and reconstruction. In aTSR secure repair of the sub scapularis tendon is critical. There are various options for detachment and repair (tenotomy, lesser tuberosity osteotomy, subscapularis “peel”) and the surgeon must see a secure fixation at the end of the procedure that is tolerant of early mobilization. The senior author uses tenotomy with interrupted non absorbable suture repair and augmented with a “core” suture of Vicryl tape. The tape can be passed through the medial muscular part of sub scapularis and then across to the preserved biceps sheath (see Fig. 1). The repair should be tested at its completion by putting the shoulder through a passive range of movement that would reflect the post-operative regime. It is best to then record this “safe range of motion” in the notes for the information of the therapists. In rTSR sizing of implants, deltoid tension and orientation of the components are critical. Inadequate soft tissue, inadequate deltoid tension, malpositioned implants could lead to early instability whose outcomes could be unsatisfactory.23 Also, impingement on soft tissues can “lever’ on the implant causing instability and once again the surgeon must ensure stability before closing the wound. The benefit of sub scapularis repair in Reverse arthroplasty is disputed and in some more lateralized designs it may be impossible to repair the tendon. However, a recent meta-analysis published in 2019 indicated that repair of the subscapularis at the time of RTSA leads to lower dislocation rates for both medialized and lateralized designs.24 In addition, when subscapularis repair is not performed, lateralized centre of rotation (COR), regardless of humeral socket design, may reduce the dislocation rates.24 The author recommends repair when feasible on the basis of possible early prevention of instability which is a big problem with reverse designs and often difficult to analyse and treat with second surgery.

-

9.

Preventing other complications

Fig. 1.

The author's (CPK) technique of subscapularis repair and reinforcement.

Nerve and vascular injury although rare are devastating for patients. Five rules as described by Flatow et al. can mitigate risk of Nerve and Vascular (NV) injuries.25 These include; careful preoperative assessment and documentation of neurovascular function, identification of the coracoid process and staying lateral to the conjoint tendon, routine use of the “tug test” to locate axillary nerve.

Some surgeons have recommended neuromonitoring but the authors have no experience of this practice. In difficult cases, use of a modern nerve stimulator can be helpful and applicable in complex primary and revision cases.

The anterior humeral circumflex artery (AHCA) and its venae comitans, collectively called the "three sisters", should be identified and ligated during a standard deltopectoral approach to the shoulder. Otherwise, brisk bleeding can occur if they are inadvertently transacted. These vessels can usually be identified overlying the inferior aspect of the subscapularis tendon when the humerus is externally rotated.

-

10.

What is good rehabilitation?

Protocols for rehabilitation involved protecting the repairs while working on early range of motion in a safe arc. Some units have different protocols for rehab of anatomic versus Reverse arthroplasty. The Shoulder therapy unit in our hospital has a common programme that can be altered according to the surgeon's preference. This is shared with the patient pre operatively and an online video is available for viewing.26 It is important to have a physiotherapy arthroplasty lead who can assist in cases where rehab is predominantly community based and often shoulder replacement is unusual practice.

-

11.

Complex and Revision surgery, who should do it?

Complex primary and revision surgery should be discussed at MDT. Getting the patient the best care might involve transfer to another surgeon, joint operating with colleagues and at time transfer to another hospital.

-

12.

Long term follow-up.

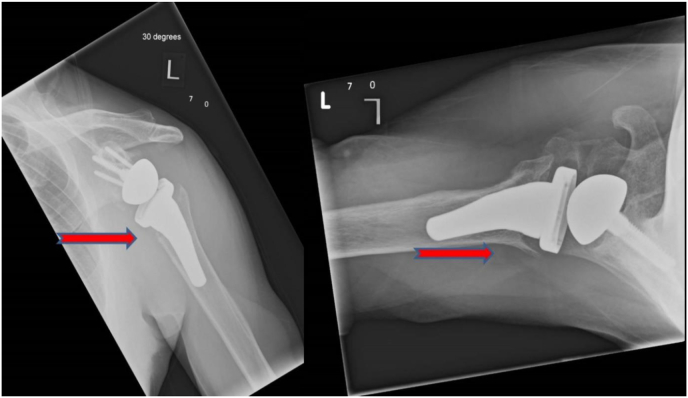

The senior author has a system of long term follow up and regular x-rays of patients. Patients are x-rayed postoperatively on first day post op prior to discharge. This x-ray can be difficult and must be done with the patient's arm held in a neutral orientation and not internally rotated in a sling. Subsequent follow up with outcome scores and x-rays at 1 year, then two yearly as long as the prosthesis is in situ. Deteriorating outcome scores should alert the surgeon to possible problems. Subtle signs on follow up x-ray may indicate impending failure or even sub-acute infection (see Fig. 2). These clinics may be difficult to finance in secondary care but Arthroplasty follow up clinics can be run by well-trained specialist nurses or extended role therapists with minimal intervention by surgeons. Our practice is to conduct these clinics in parallel to normal shoulder clinics which allows immediate surgical reporting of x-rays. The Oxford and Constant shoulder scores are documented on the electronic patient record which allows excellent progress reports and clinical audit.

-

13.

The National Joint Registry (UK).

Fig. 2.

Humeral bone changes at routine follow up (see red arrows). initially thought to be stress shielding, subsequent aspiration confirmed chronic infection with C. Acnes.

All the cases of TSR are collected and analysed by NJR in the UK.27 The National Joint Registry records, monitors, analyses and reports on performance outcomes in joint replacement surgery in a continuous drive to improve service quality and enable research analysis, to ultimately improve patient outcomes. The authors believe that all surgeons should contribute to joint registries and keep good audit data for scrutiny.

2. Summary and conclusions

Shoulder arthroplasty is uncommon but increasing in number when compared to hip and knee arthroplasty. The average UK shoulder surgeon performs less than 10 a year and revision surgery is even more rare.28 We are still learning best practice and prosthesis design has changed over the past years with extensive choices especially in Reverse designs. Each of these designs has unique biomechanical properties and require a deep understanding of indications. Good surgical training and the use of Multidisciplinary meetings for complex cases should improve the safety and quality of surgery for patients and ultimately long-term outcome of shoulder arthroplasty.

Funding/sponsorship

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contribution

First draft prepared by Cormac P Kelly. Every second draft preparation and addition of appropriate references was done by Sachin Kumar.

Declaration of competing interest

Cormac P Kelly is an advisor to Enovis (formerly Mathys UK) and Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Hospital receives financial support for their Shoulder Fellowship training programme.

Sachin Kumar: None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Palsis J.A., Simpson K.N., Matthews J.H., Traven S., Eichinger J.K., Friedman R.J. Current trends in the use of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. Orthopedics. 2018 May 1;41(3):e416–e423. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20180409-05. Epub 2018 Apr 16. PMID: 29658976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt A.M., Throckmorton T.W. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for B2 glenoid deformity. J Shoulder Elb Arthroplast. 2019 Dec 30;3 doi: 10.1177/2471549219897661. PMID: 34497958; PMCID: PMC8282141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadecker M., Gu A., Ramamurti P., et al. Risk of revision based on timing of corticosteroid injection prior to shoulder arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2022 May;104-B(5):620–626. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.104B5.BJJ-2021-0024.R3. PMID: 35491573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein D.M., Bucchieri J.S., Pollock R.G., Flatow E.L., Lu Bigliani. Arthroscopic debridement of the shoulder for osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(5):471–476. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.medicaldesignandoutsourcing.com/educational-videos-improve-patient-consent-process-and-save-time/

- 6.Gates S., Sager B., Khazzam M. Preoperative glenoid considerations for shoulder arthroplasty: a review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020 Mar 2;5(3):126–137. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.190011. PMID: 32296546; PMCID: PMC7144890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes N.S. Patient-specific instrumentation for total shoulder arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev. 2017 Mar 13;1(5):177–182. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000033. PMID: 28461945; PMCID: PMC5367539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.https://www.vumedi.com/video/planning-a-tmr-shoulder-case-in-signaturetm-one-software/

- 9.https://www.healio.com/news/orthopedics/20210809/templating-software-is-advantageous-when-preoperative-planning-for-shoulder-arthroplasty

- 10.Mattei L., Mortera S., Arrigoni C., Castoldi F. Anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: an update on indications, technique, results and complication rates. Joints. 2015 Nov 3;3(2):72–77. doi: 10.11138/jts/2015.3.2.072. PMID: 26605254; PMCID: PMC4634807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flatow E.L., Harrison A.K. A history of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 Sep;469(9):2432–2439. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1733-6. PMID: 21213090; PMCID: PMC3148354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuff D.J., Pupello D.R. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:2050–2055. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01637. ([PubMed] [Google Scholar]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake G.N., O'Connor D.P., Edwards T.B. Indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1526–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1188-9. ([PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno N., Denard P.J., Raiss P., et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; Jul;95:1297–1304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackenzie D. The antero-superior exposure for total shoulder replacement. J Orthop Traumatol. 1993;2(2):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillespie R.J., Garrigues G.E., Chang E.S., Namdari S., Williams G.R., Jr. Surgical exposure for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: differences in approaches and outcomes. Orthop Clin N Am. 2015;46(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch Nancy M., et al. Neurologic complications after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;1:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb M.F., Funk L. An anterosuperior approach for proximal humerus fractures. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7(2):77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redfern T.R., Wallace W.A., Beddow F.H. Clavicular osteotomy in shoulder arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 1989;13(1):61–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00266725.PMID:2722317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiser M.C., Moucha C.S. The current state of screening and decolonization for the prevention of Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015 Sep 2;97(17):1449–1458. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01114. PMID: 26333741; PMCID: PMC7535098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalmers P.N., Beck L., Stertz I., Tashjian R.Z. Hydrogen peroxide skin preparation reduces Cutibacterium acnes in shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, blinded, controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 Aug;28(8):1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.03.038. Epub 2019 Jun 20. PMID: 31229329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheer V.M., Jungeström M.B., Serrander L., Kalén A., Scheer J.H. Benzoyl peroxide treatment decreases Cutibacterium acnes in shoulder surgery, from skin incision until wound closure. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 Jun;30(6):1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.12.019. Epub 2021 Feb 3. PMID: 33545336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo R.A., Gamradt S.C., Mattern C.J., et al. Sports medicine and shoulder service at the hospital for special surgery, New York, NY. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Jun;20(4):584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.08.028. Epub 2010 Dec 16. PMID: 21167744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthewson G., Kooner S., Kwapisz A., Leiter J., Old J., MacDonald P. The effect of subscapularis repair on dislocation rates in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 May;28(5):989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.11.069. Epub 2019 Mar 1. PMID: 30827833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flatow Evan, Olujimi Victor. Top five rules to avoid neurovascular injury during total shoulder arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 2017;28(No. 1) WB Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- 26.https://vimeo.com/98937844

- 27.https://www.njrcentre.org.uk

- 28.Kelly C.P., Fitzgerald C., Dixon S. Frequency of shoulder arthroplasty among surgeons in England and Wales. Orthopaedic Proceedings. 2005;87-B SUPP_II, 163-163. [Google Scholar]