Abstract

Purpose:

Voiding dysfunction (VD) leading to urinary retention is a common neurogenic lower urinary tract symptom in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Currently, the only effective management for patients with MS with VD is catheterization. Transcranial Rotating Permanent Magnet Stimulator (TRPMS) is a noninvasive, portable, multifocal neuromodulator that simultaneously modulates multiple cortical regions and the strength of their functional connections. In this pilot trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03574610), we investigated the safety and therapeutic effects of TRPMS in modulating brain regions of interest (ROIs) engaged with voiding initiation to improve VD in MS women.

Materials and Methods:

Ten MS women with VD (having % post-void residual/bladder capacity [%PVR/BC] ≥40% or being in the lower 10th percentile of the Liverpool nomogram) underwent concurrent functional magnetic resonance imaging/urodynamic study (fMRI/UDS) with 3 cycles of bladder filling/emptying, at baseline and post-treatment. Predetermined ROIs and their activations at voiding initiation were identified on patients’ baseline fMRI/UDS scans, corresponding to microstimulator placement. Patients received 10 consecutive 40-minute treatment sessions. Brain activation group analysis, noninstrumented uroflow, and validated questionnaires were compared at baseline and post-treatment.

Results:

No treatment-related adverse effects were reported. Post-treatment, patients showed significantly increased activation in regions known to be involved at voiding initiation in healthy subjects. %PVR/BC significantly decreased. Significant improvement of bladder emptying symptoms were reported by patients via validated questionnaires.

Conclusions:

Both neuroimaging and clinical data suggested TRPMS effectively and safely modulated brain regions that are involved in the voiding phase of the micturition cycle, leading to clinical improvements in bladder emptying in patients with MS.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, magnetic resonance imaging

Graphical Abstract

Due to extensive involvement of the brain in bladder control, proper function of lower urinary tract is susceptible to neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic multifocal demyelinating disease that can affect any part of the central nervous system. Voiding dysfunction (VD) is one of the most common neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunctions in MS,1 characterized by difficulty in emptying the bladder, urinary hesitancy, slow or weak urinary stream and urinary retention.2 Neurogenic VD is often caused by either detrusor underactivity, functional outflow obstruction (urethral sphincter spasticity) or a combination of both (lack of coordination between these 2 actions seen in detrusor sphincter dyssenergia), leading to ineffective elimination of urine2 with long-term sequelae of incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections or permanent renal failure.3 Although medications and sacral neurostimulators have been attempted, the primary effective management for neurogenic VD includes indwelling bladder catheters or intermittent self-catheterizations.4 Catheterization is a burden especially in neuropathic patients, in whom lower extremity spasms, compromised hand dexterity or visual disturbances may be present.4 The burden, cost and morbid side effects associated with catheterizations prompted us to look into alternate therapeutic targets for VD management beyond the bladder, such as the brain where bladder control centers are located.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive neuromodulation in which an electromagnetic coil is held over the scalp to deliver a rapidly pulsed magnetic field to the cortex to modulate neurons within a limited area.5 A preliminary study using commercially available TMS in 10 MS patients demonstrated that repetitive TMS applied to the motor cortex was able to reduce urinary post-void residual (PVR), while increasing the detrusor pressure at the time of voiding.6 Despite TMS’s potentials, brain control of the bladder involves multiple regions and marketed TMS devices use large coils that can only modulate 1 cortical region at a time. Effectively modulating the voiding brain networks requires a neuromodulator that could safely modulate multiple cortical areas concurrently.

In this pilot clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.Gov identifier: NCT03574610), we explored the safety and therapeutic effects of an individualized, noninvasive, portable and multifocal neuromodulator, called Transcranial Rotating Permanent Magnet Stimulator (TRPMS),7 in mitigating VD symptoms in MS patients. Our primary outcomes were changes in brain activation in modulated brain regions of interest (ROIs), measured via blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals, and secondary outcomes were changes in clinical data, including noninstrumented uroflow (objectively) and validated questionnaires pertaining to bladder symptoms (subjectively), following TRPMS treatment. We hypothesized that TRPMS on voiding brain centers is safe and able to restore brain activation patterns seen in healthy individuals during the bladder micturition cycle, leading to VD symptom improvement in female MS patients.

METHODS

Subjects

Female adults ≥18 years of age with clinically stable MS (no flareups in the preceding 6 months) and symptomatic neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction for ≥3 months were screened at our tertiary neurourology clinic for this Institutional Review Board-approved study (IRB No. PRO00019329). Patients with VD (defined as having % post-void residual/bladder capacity (%PVR/BC) ≥40%, or having Liverpool Nomogram in women percentile (maximum uroflow rate over voided volume) of <10%8 or performing self-catheterization were invited to participate. Table 1 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

| |

| • Adult female (≥18 years old) | • Male |

| • Clinically stable MS (Expanded Disability Status Scale ≤6.5) | • Severe debilitating MS |

| • Bladder symptoms ≥3 months | • History of recent seizure (<1 year) |

| • VD diagnosis, defined as having at least 1 of following: | • History of anatomical bladder outlet obstruction (eg strictures, urethral slings), bladder/bladder neck suspension operations, previous bladder reconstruction procedures (eg augmentation cystoplasty) |

| ◦ %PVR/BC >40% | |

| ◦ Liverpool Nomogram percentile <10% | |

| ◦ Perform self-catheterization | • Pregnant or planning to become pregnant |

| • Contraindication to MRI | |

| • Recent intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA injection (<6 months) | |

| • Other neurological disorders beside MS | |

Intervention and Data Acquisition

Clinical Evaluations.

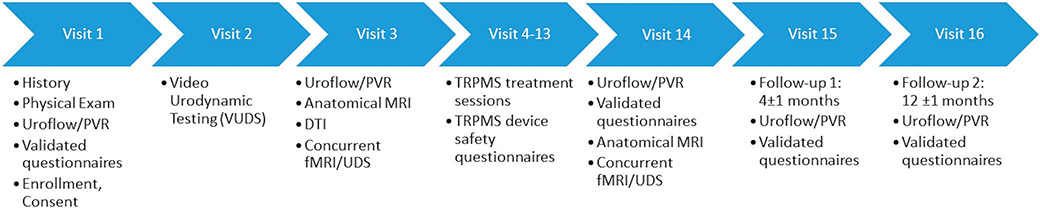

Figure 1 details data collected at each visit. Validated questionnaires, noninstrumented uroflow, and PVR volume were collected for inclusion criteria and as baseline values, and again at post-treatment, and 4-month and 12-month followups.9

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of clinic visits where clinical data are collected and patients receive treatment. Validated questionnaires include the American Urological Association Symptom Score (AUASS), NBSS, Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).

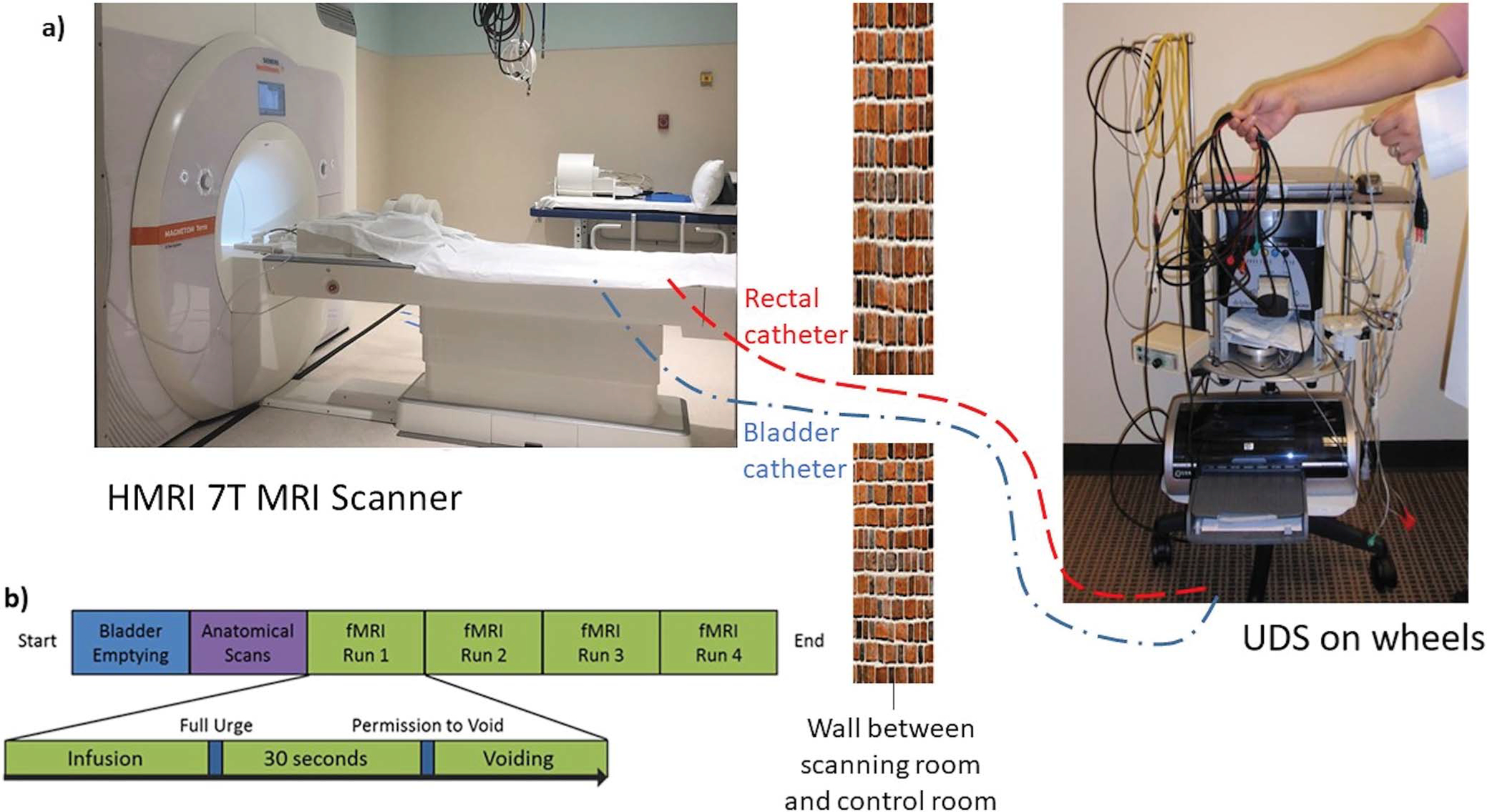

Prior to baseline scans, subjects received a treatment-cap fitting session, where their head measurement was recorded according to the 10–20 system.10 Subjects entered a 7-Tesla Siemens MAGNETOM Terra magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (3T Siemens MAGENTOM Vida MRI scanner if contraindicated for 7T). Double-lumen 7Fr MRI-compatible urodynamic study (UDS) vesical and intrabdominal catheters were placed in the subjects. Tubing was extended out to the control room to monitor the entire bladder cycle with relative abdominal and vesical pressures on a Laborie UDS machine (fig. 2, a).

Figure 2.

a, concurrent 7T fMRI/UDS setup where MRI-compatible bladder and rectal catheters are passed through small opening in wall between control and scanner room to connect to UDS machine (not to scale). b, concurrent fMRI/UDS testing protocol.

Structural and functional MRI images were collected per our previous protocol.9 During the concurrent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)/UDS, the bladder was filled with sterile saline at 75 ml/minute until subjects signaled a “strong desire to void.” Subjects were instructed to hold for 30 seconds, after which permission to void was given. UDS was performed concurrently during fMRI to monitor the entire filling and voiding cycles. After voiding/attempt to void was completed, the bladder was aspirated and the cycle was repeated 3 to 4 times (fig. 2, b). This procedure was performed again during post-treatment fMRI/UDS scans, without the treatment cap-fitting session.

TRPMS Device and ROI.

TRPMS,11 developed by the Neurophysiology and Neuromodulation laboratory at Houston Methodist Hospital, is a wearable and portable cortical neuromodulation device with multifocal stimulation.7 Compared to conventional TMS, TRPMS enables greater uniformity, consistency and focality in the stimulation of targeted cortical areas subject to significant anatomical variability.

TRPMS consists of axially magnetized cylindrical magnets attached to, and rapidly rotated by, battery-operated direct-current motors. The magnet-motor assemblies, called microstimulators, generate an oscillating magnetic field that can penetrate a depth of ~2 cm into the cerebral cortex from the scalp,12 depolarizing the cell membrane of cortical neurons, resulting in net cortical excitation or inhibition depending on the stimulus parameters.7 For this study, the total duration of stimulation was 40 minutes (480 stimuli) for excitation and 10 minutes (120 stimuli) for inhibition. Each stimulus was 100 ms and delivered at the rate of 0.2 Hz. Experimental justification for these parameters was based on previous studies with TRPMS.7,12,13

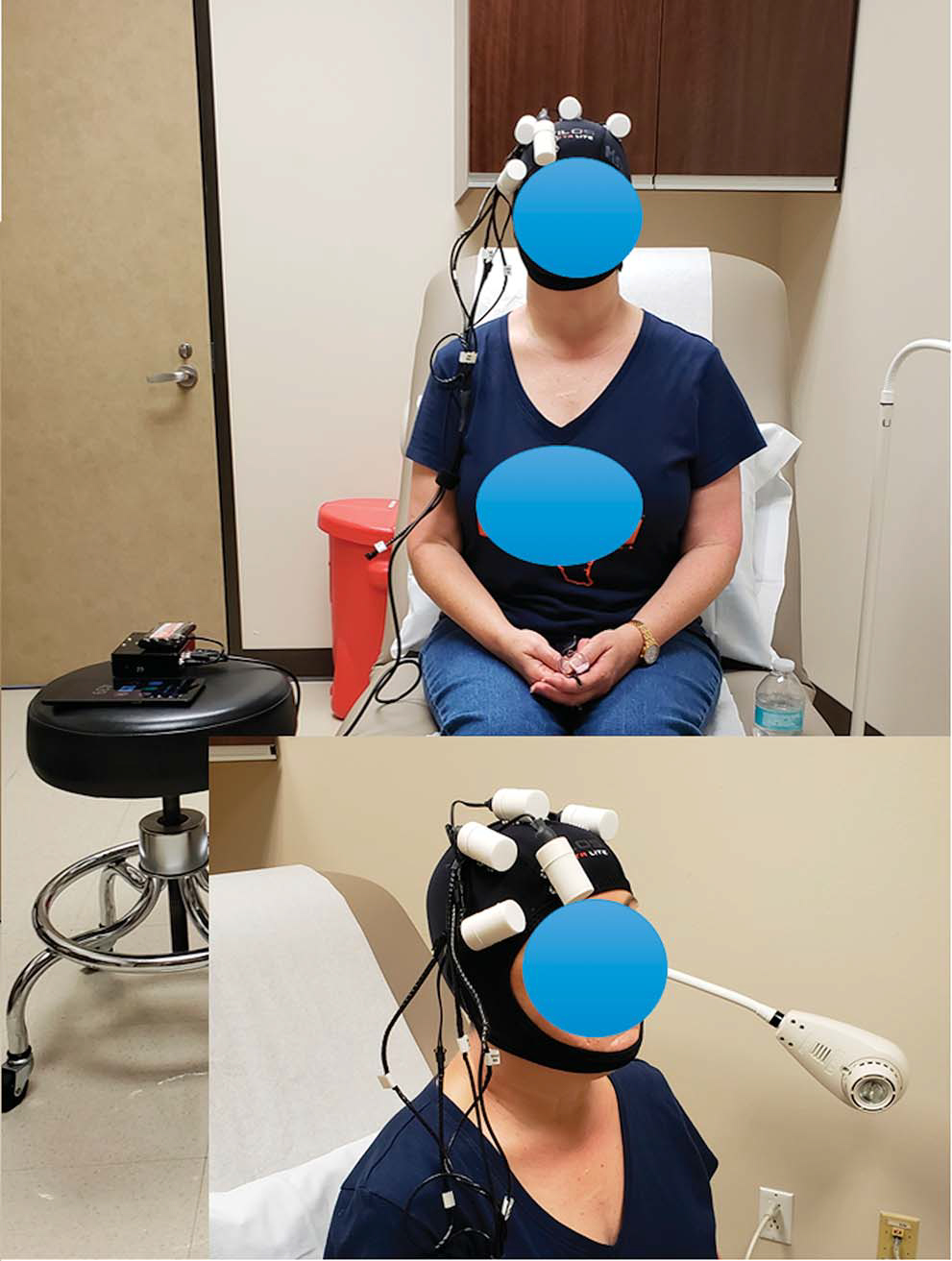

Up to 6 microstimulators can be attached onto a neoprene cap worn on the head to modulate desired cortical locations. The microstimulators are connected by a cable to, and activated by, a stimulator console, ie controlled by a tablet, and consists of an electronic circuit and a microprocessor. The prescribed modulating program uploaded in the portable stimulator console delivers the desired magnetic stimulation to the brain (fig. 3).

Figure 3.

MS patient receiving TRPMS treatment with individualized treatment cap. Five microstimulators were secured on treatment cap, corresponding to 5 ROIs identified from patient’s fMRI scan.

Because our cohort has difficulty voiding, we proposed to stimulate superficial brain regions that are activated at voiding initiation and inhibit regions involved in pelvic floor (PF) contraction to promote relaxation of the urethral sphincter (PF complex) to facilitate urine passage. We refined the list based on literature with the template listed in table 2, with 5 regions to modulate (stimulate/inhibit) for this pilot trial.

Table 2.

Cortical regions to modulate and their corresponding tasks

| Cortical regions | Task | Stimulate/Inhibit? |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Rt IFG | Voiding initiation16,17,24 | Stimulate (40 mins) |

| Lt dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Decision to void25 | Stimulate (40 mins) |

| Bilat SMA | PF contraction18,19 | Inhibit (10 mins) |

| Rt middle frontal gyrus | PF contraction24 | Inhibit (10 mins) |

| Rt dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Pain/ bladder pain syndrome30 | Inhibit (10 mins) |

Microstimulator Setup and Treatment

Following baseline scan, ROIs were identified for each patient based on their brain anatomy and activation at voiding initiation (table 2). The Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates of these regions based on their activation/deactivation were recorded, from which their corresponding 10–20 system positions were obtained. The target sites of modulation were marked on the cap using the identified 10–20 system positions derived from the patients’ head measurement.10 The microstimulators were securely attached at target sites onto the treatment cap that the patient wore during each treatment session. The treatment, therefore, was individualized for each patient and consistent throughout the treatment course (supplementary Appendix 1, https://www.jurology.com).

Patients received 10 TRPMS treatment sessions in the clinic on weekdays for 2 weeks. Total duration of each treatment session was 40 minutes with continuous supervision by a study team member. All patients filled out a device safety questionnaire before and after each session.

Outcome Measures and Data Analysis

Neuroimaging Outcomes.

BOLD signal (which represents brain activation and/or deactivation compared to resting state) at “strong desire to void” and “(attempt of) voiding initiation” was obtained at baseline and post-treatment scans, using AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages; https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/). Functional and anatomical data were co-registered and motion-corrected. Significantly activated voxels were identified at the 2 aforementioned time points using a generalized linear model.14 Group level analysis was performed and significantly activated voxels (p <0.05) were identified by Student’s t-test. Comparisons were drawn between baseline and post-treatment group results.

Clinical Outcomes.

Clinical outcomes were measured objectively through noninstrumented uroflow and PVR, and subjectively through validated questionnaires. Paired t-tests (α=0.05) were performed (using RStudio) to compare these values at post-treatment and followups to baseline.

Safety Outcomes.

Safety was measured by the incidence of patient or investigator-reported adverse events, monitored by the study team and via questionnaires (regarding mood, pain, dizziness, and other sensations) collected at each treatment session.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

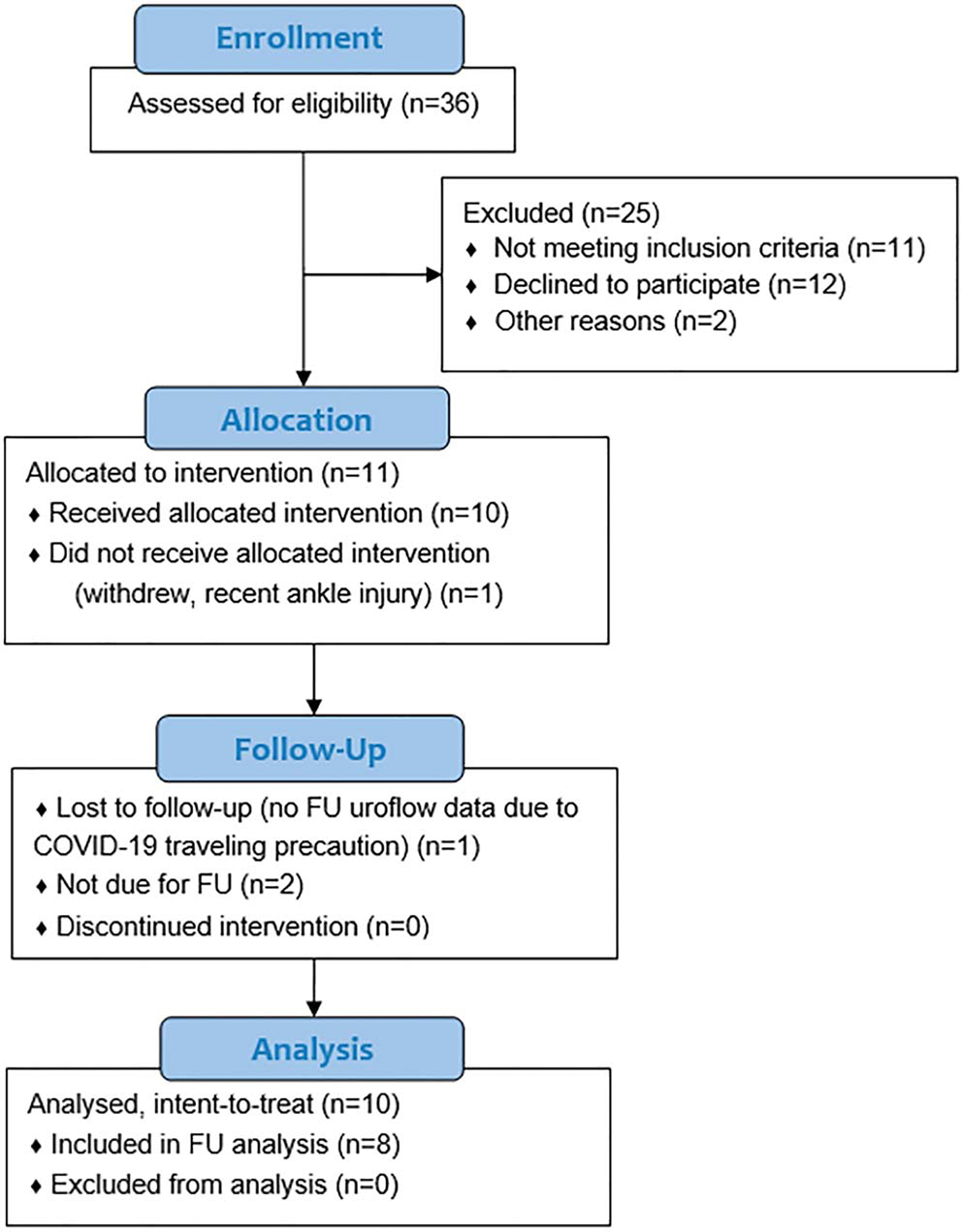

Eleven patients were eligible and consented to participate. One withdrew before baseline scan, and 10 received the treatment and completed all their scans and assessments (July 2019–December 2020) and were included in the analysis. Among 8 patients who completed their 4-month followups, 1 could not return for an in-person visit and only her validated questionnaires were collected. Analysis proceeded on an intent-to-treat basis (fig. 4). Table 3 details the patient demographics.

Figure 4.

CONSORT diagram. FU, followup.

Table 3.

Patient demographics

| Pt Characteristics (10 pts) | Mean (range) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (yrs) | 53.40 | (35–77) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.83 | (19.9–41.8) |

| MS duration (yrs) | 16.30 | (1 –44) |

| Expanded Disability Status Scale | 3.80 | (1.5–6.5) |

| Baseline %PVR/BC | 54.04 (32. | 05–81.59) |

| Baseline Liverpool nomogram percentile | 34.00 | (5–96) |

| No. voided during baseline fMRI/ total No. (%) | 4/10 | (40) |

| No. neurogenic detrusor overactivity during | 4/10 | (40) |

| baseline fMRI/total No. (%) | ||

| Post-treatment %PVR/BC | 29.46 (0. | 76–64.54) |

| Post-treatment Liverpool nomogram percentile | 62.8 | (3–99) |

| No. voided during post-treatment fMRI/total No. (%) | 6/10 | (60) |

| No. neurogenic detrusor overactivity during | 4/10 | (40) |

| post-treatment fMRI/total No. (%) | ||

Neuroimaging Outcomes

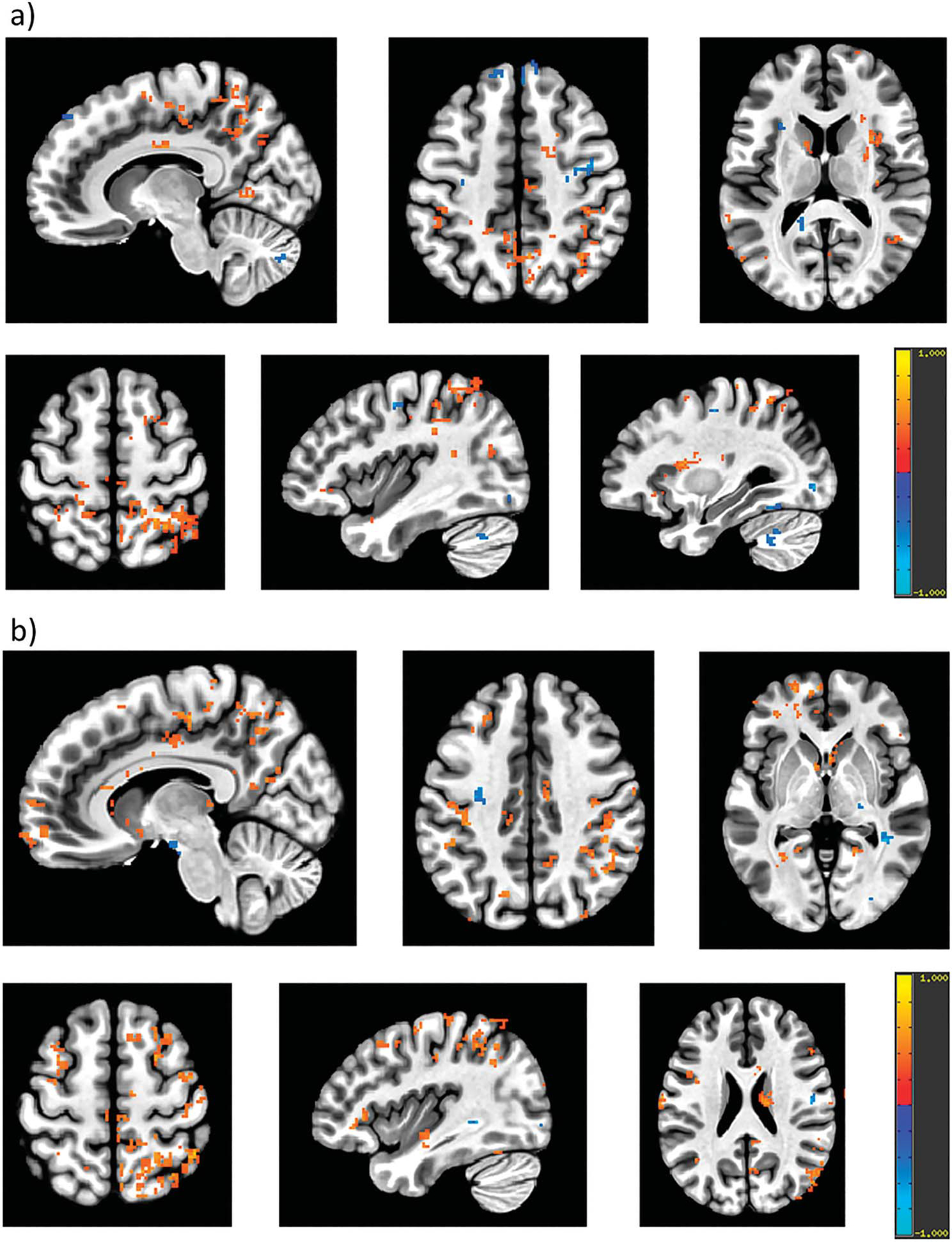

Figure 5 and supplementary Appendix 2 (https://www.jurology.com) show regions with significant increase and decrease in activation post-treatment compared to baseline (p <0.05) at strong desire to void (fig. 5, a) and (attempt of) voiding initiation (fig. 5, b).

Figure 5.

Group analysis for change in BOLD signals, which correspond to activation/deactivation compared to resting state, following treatment (post-treatment minus baseline, p <0.05) at strong desire to void (a) and voiding initiation (b). Red indicates significant increase in BOLD signals and blue indicates significant decrease in BOLD signals at post-treatment compared to baseline. Following treatment: a, at strong desire to void, there was significant increase in activation in bilateral postcentral gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, middle cingulate cortex, thalamus, precuneus, left IFG, left superior, middle and inferior temporal gyrus, caudate nucleus, hippocampus, putamen and right posterior cingulate cortex. Significant decrease in activation was observed in bilateral precentral gyrus, left middle and superior frontal gyri, left insula and right cerebellum cortex. b, at voiding initiation, there was significant increase in bilateral inferior, superior and middle frontal gyri, superior and middle temporal gyri, supramarginal gyrus, rectal gyrus, SMA, precentral and postcentral gyri, precuneus, thalamus, middle cingulate cortex, left anterior cingulate, left cerebellum, right insula and right parietal lobe. Decreased activation was observed in bilateral hippocampus and right fusiform gyrus.

Clinical Outcomes

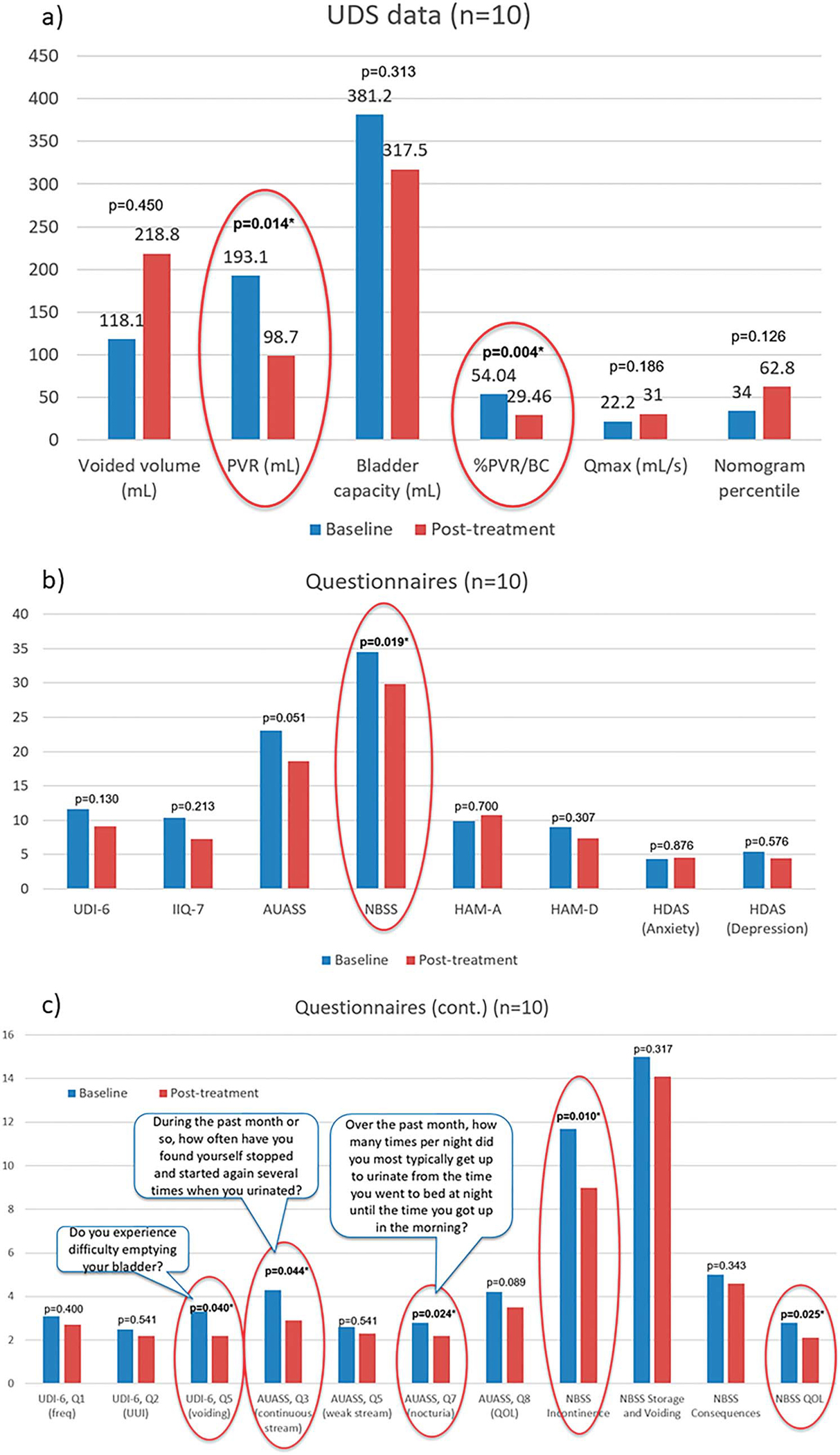

Post-treatment, mean %PVR/BC and PVR significantly decreased (p=0.004 and p=0.014, respectively). Voided volume, maximum urine flow velocity and nomogram percentile increased (p >0.05; fig. 6, a). Almost all questionnaires showed improvement (fig. 6, b), with significance in Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score (NBSS; p=0.019). Questions pertaining to voiding symptoms and sub-scores showed trends of improvement, some with significant difference (fig. 6, c).

Figure 6.

Clinical outcomes following treatment. Noninstrumented uroflow (a), validated questionnaire (b), specific questions from validated questionnaires pertaining to voiding symptoms (c) and NBSS sub-scores. Lower score indicates improvement in symptoms. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared to baseline (p <0.05, also circled in red).

Safety Outcomes

No treatment-related adverse effects were reported by patients or investigator.

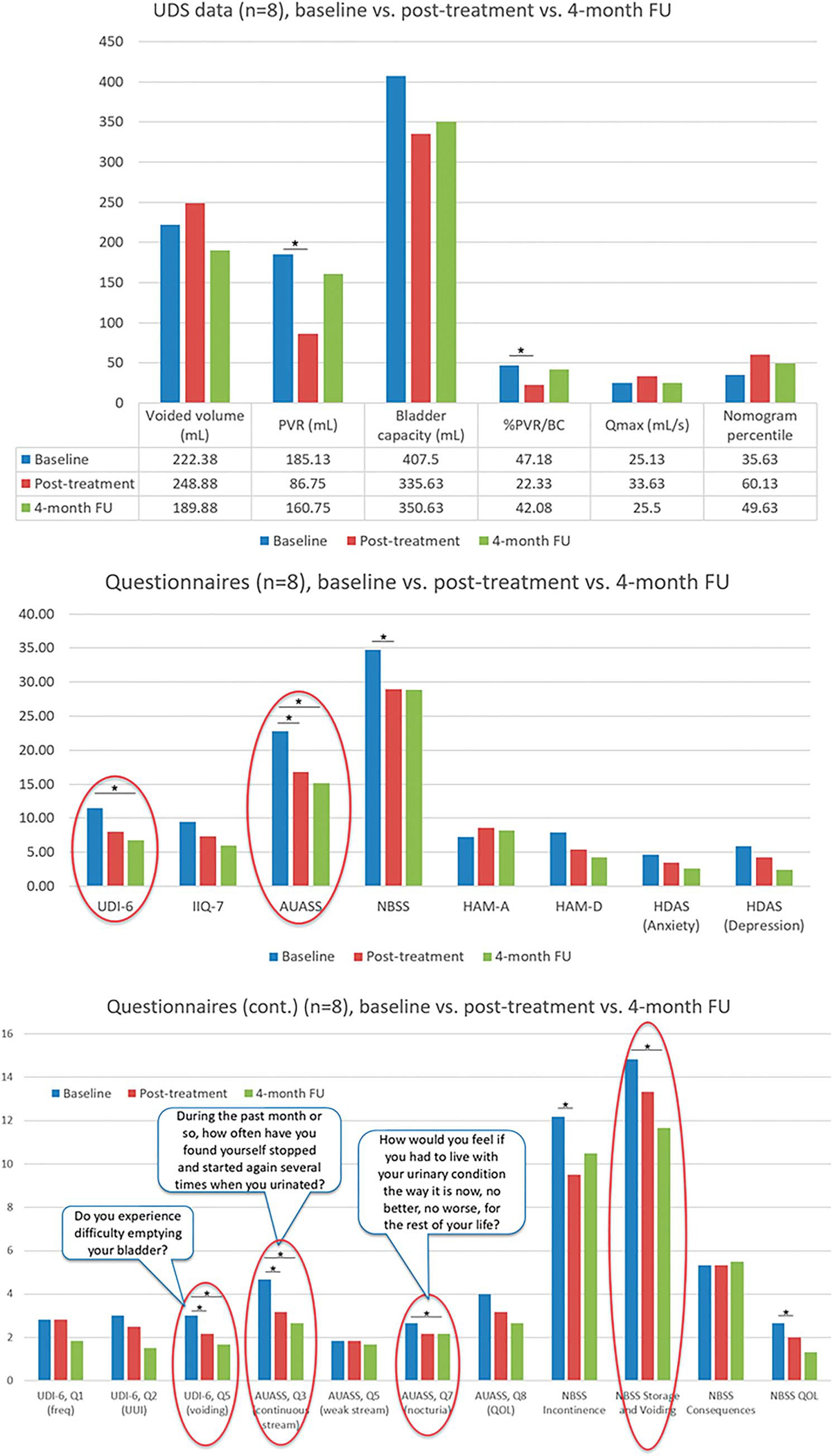

Four-Month Followup

Four months post-treatment, all clinical data on the first 8 patients moved closer to baseline values, still with trends of improvement and some with significant difference (fig. 7, a and b). Questions regarding voiding showed continual trends of improvement, with some showing significant difference (fig. 7, c).

Figure 7.

Clinical outcomes at 4-month followup. Noninstrumented uroflow (a), validated questionnaire (b), specific questions from validated questionnaires pertaining to voiding symptoms (c) and NBSS sub-scores. Lower score indicates improvement in symptoms. Asterisks indicate significant difference compared to baseline (p <0.05); significant differences at 4-month followup compared to baseline are circled in red.

DISCUSSION

Although the periaqueductal grey (PAG) and pontine micturition center (PMC) have more extensive roles in the initiation of voiding and could serve as potential targets for intervention,15 they are located deeper in the brain and inaccessible with current transcranial stimulation modalities. Modulation of these regions might also not be safe, as they are responsible for other core vital functions such as regulating circulation and breathing. Therefore, we explored a noninvasive treatment for MS patients by modulating only cortical areas known to be directly involved in initiating or continuing voiding (supplementary motor areas [SMAs], dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus [IFG])16–18 or PF contraction (medial prefrontal cortex and SMA).18,19 Surprisingly, following treatment we observed significant changes in other and deeper brain regions (in addition to modulated regions) that have been known to be involved in bladder control.

Specifically, during strong desire to void, there was an increase in activation in the postcentral gyrus (sensory cortex), SMA (motor and specifically PF contraction) and thalamus (sensory relay station), whose co-activation has been observed with increasing bladder sensation,19,20 along with the IFG (modulated region), superior and middle temporal gyri, parietal lobe and caudate nucleus,16,18,21,22 which have been reported to be activated during bladder filling and urine with-holding. Decreased activation was observed in the precentral gyri and right cerebellum, whose activation during the filling phase inhibits the micturition reflex.23 In cases of MS patients who have difficulty initiating voiding, relaxation of the PF and preparation for voiding are desired. Therefore, this change could indicate a more readily lifted inhibition of the micturition reflex, suggesting that patients were more prepared to void.

During attempts to initiate voiding we observed an increase in activation in the right IFG, one of the targeted regions for stimulation, and the left anterior cingulate and bilateral middle cingulate (emotional response), SMA (motor), thalamus (sensory), cerebellum, middle frontal and temporal gyri, all of which have been known to be activated at successful voiding initiation.16,17,23–25 However, other prominent regions involved in voiding initiation such as PAG and PMC did not show significant change. This could indicate an alternative route of activation during voiding initiation to compensate for the damage in white matter seen in MS patients. There was a decrease in activation in the hippocampus, which was known to be deactivated when attention is required. Triggering the voiding reflex, especially in VD patients, can require attention and a decrease in activation in this region during voiding initiation following treatment may suggest that patients made a more conscious effort to initiate voiding.

Changes in brain activation were reflected in symptom improvement via uroflow and validated questionnaires. Specifically, after treatment patients’ %PVR/BC (an inclusion criterion for our study) and PVR significantly decreased to almost half the baseline values, with improving trends observed in other parameters. Supplementary Appendix 3 (https://www.jurology.com) provides an example of uroflow and PVR in a subject, showing subject’s improved ability to void following treatment. Subjectively, the trends of improvement in questionnaires and especially significant difference observed in the NBSS,26 and specific questions regarding voiding indicated patients’ perception in bladder symptom improvement. Both neuroimaging and clinical results suggest that our primary and secondary outcomes (changes in activation of modulated and other brain regions and changes in clinical data) have been accomplished.

At followup, although all uroflow and validated questionnaire results moved closer to their baseline values, significance observed in some questionnaires suggested that improvement in symptoms was still perceived 4 months after treatment. Although TRPMS modulation might have strengthened the voiding network and functional connection of the brain regions in each network immediately following treatment, these functional connections alter quicker than structural connections,27 possibly leading to bladder performance similar to baseline after 4 months. Therefore, future studies with longer treatment periods or multiple treatment periods should be considered to examine the lasting effects of TRPMS.

We excluded male patients to ensure a more uniform study population and to eliminate anatomical confoundings such as bladder outlet obstruction as a result of benign prostatic hyperplasia. fMRI studies suggest that approximately 12–20 subjects are required to achieve 80% power at the single-voxel level for typical activations.28–30 However, most published fMRI studies evaluating bladder function have included 8–12 subjects. We included 10 subjects for analysis in this pilot trial (which met our enrollment goal despite the COVID-19 pandemic); however, sham-controlled studies with larger sample size are needed. The unnatural environment of voiding while supine in the MRI with a passively infused bladder might cause difficulty with voiding. However, most MS patients are familiar with UDS, catheterization and MRI. Additionally, MS is a heterogeneous disease that can lead to multiple lesion locations, including the spinal cord. We are aware that these are factors that could affect treatment outcomes; therefore, identifying baseline factors that could predict response to therapy is our next step. Although following TRPMS treatment we were able to observe patterns of activation similar to those of healthy individuals during the bladder cycle, the mechanisms through which these networks were strengthened need to be further explored with other analyses such as functional connectivity.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of noninvasive, individualized multifocal cortical modulation in MS patients with VD. Modulating cortical regions controlling the initiation of voiding might lead to strengthening of the voiding network by inducing significant changes in activation/deactivation and connectivity of both cortical and subcortical brain regions comprising the micturition circuits, resulting in clinical improvement in VD in women with MS. Although future randomized control trials are needed, results of this study could lay the groundwork for designing individualized noninvasive, at-home neuromodulation trials that could transform management of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction in MS and other neuropathic patient populations.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This is an investigator-initiated trial by Dr. Rose Khavari. Dr. Rose Khavari is partially supported by K23DK118209, by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, NIH) and Houston Methodist Clinician Scientist Program. Sponsored by the Methodist Hospital System. Funder and sponsor have no ultimate authority over the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- %PVR/BC

% post-void residual/bladder capacity

- BOLD

blood oxygen level-dependent

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- IFG

inferior frontal gyrus

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NBSS

Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score

- PF

pelvic floor

- PVR

post-void residual

- ROI

region of interest

- SMA

supplementary motor area

- TMS

transcranial magnetic stimulation

- TRPMS

Transcranial Rotating Permanent Magnet Stimulator

- UDS

urodynamic study

- VD

voiding dysfunction

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest: SAH is listed as an inventor on issued U.S. patent numbers 9456784, 10398907, 10500408 and 10874870 covering the device used in this study. The patent is licensed to Seraya Medical, LLC. Other authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aharony SM, Lam O and Corcos J: Evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms in multiple sclerosis patients: review of the literature and current guidelines. Can Urol Assoc J 2017; 11: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panicker JN and Fowler CJ: Lower urinary tract dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol 2015; 130: 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nazari F, Shaygannejad V, Mohammadi Sichani M et al. : Quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis and voiding dysfunction: a cross-sectional study. BMC Urol 2020; 20: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoffel JT: Contemporary management of the neurogenic bladder for multiple sclerosis patients. Urol Clin North Am 2010; 37: 547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fregni F and Pascual-Leone A: Technology insight: noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology-perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2007; 3: 383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centonze D, Petta F, Versace V et al. : Effects of motor cortex rTMS on lower urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007; 13: 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helekar SA and Voss HU: Transcranial brain stimulation with rapidly spinning high-field permanent magnets. IEEEAccess 2016; 4: 2520. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haylen BT, Ashby D, Sutherst JR et al. : Maximum and average urine flow rates in normal male and female populations—the Liverpool nomograms. Br J Urol 1989; 64: 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran K, Shi Z, Karmonik C et al. : Therapeutic effects of non-invasive, individualized, transcranial neuromodulation treatment for voiding dysfunction in multiple sclerosis patients: study protocol for a pilot clinical trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2021; 7: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klem GH, Lüders HO, Jasper HH et al. : The ten-twenty electrode system of the international federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl 1999; 52: 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helekar S, Voss HU, inventors; Patent number 10398907: Method and apparatus for providing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to an individual. US: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helekar SA, Convento S, Nguyen L et al. : The strength and spread of the electric field induced by transcranial rotating permanent magnet stimulation in comparison with conventional transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci Methods 2018; 309: 153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu D, McCane CD, Lee J et al. : Multifocal transcranial stimulation in chronic ischemic stroke: a phase 1/2a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020; 29: 104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Z, Tran K, Karmonik C et al. : High spatial correlation in brain connectivity between micturition and resting states within bladder-related networks using 7 T MRI in multiple sclerosis women with voiding dysfunction. World J Urol 2021; 39: 3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler CJ and Griffiths DJ: A decade of functional brain imaging applied to bladder control. Neurourol Urodyn 2010; 29: 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blok BF, Sturms LM and Holstege G: Brain activation during micturition in women. Brain 1998; 12: 2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shy M, Fung S, Boone TB et al. : Functional magnetic resonance imaging during urodynamic testing identifies brain structures initiating micturition. J Urol 2014; 192: 1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blok BF, Sturms LM and Holstege G: A PET study on cortical and subcortical control of pelvic floor musculature in women. J Comp Neurol 1997; 389: 535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrum A, Wolff S, van der Horst C et al. : Motor cortical representation of the pelvic floor muscles. J Urol 2011; 186: 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffiths D: Neural control of micturition in humans: a working model. Nat Rev Urol 2015; 12: 695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tadic SD, Griffiths D, Murrin A et al. : Brain activity during bladder filling is related to white matter structural changes in older women with urinary incontinence. Neuroimage 2010; 51: 1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Athwal BS, Berkley KJ, Hussain I et al. : Brain responses to changes in bladder volume and urge to void in healthy men. Brain 2001; 124: 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastide L and Herbaut AG: Cerebellum and micturition: what do we know? A systematic review. Cerebellum Ataxias 2020; 7: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khavari R, Karmonik C, Shy M et al. : Functional magnetic resonance imaging with concurrent urodynamic testing identifies brain structures involved in micturition cycle in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Urol 2017; 197: 438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ketai LH, Komesu YM, Dodd AB et al. : Urgency urinary incontinence and the interoceptive network: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 215: 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welk B, Lenherr S, Elliott S et al. : The Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score (NBSS): a secondary assessment of its validity, reliability among people with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2018; 56: 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L et al. : Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desmond JE and Glover GH: Estimating sample size in functional MRI (fMRI) neuroimaging studies: statistical power analyses. J Neurosci Methods 2002; 118: 115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mumford JA and Nichols TE: Power calculation for group fMRI studies accounting for arbitrary design and temporal autocorrelation. Neuroimage 2008; 39: 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nizard J, Esnault J, Bouche B et al. : Long-term relief of painful bladder syndrome by high-intensity, low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. Front Neurosci 2018; 12: 925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.