Abstract

We describe the tissues and organs that show exceptional regenerative ability following injury in the spiny mouse, Acomys. The skin and ear regenerate: hair and its associated stem cell niches, sebaceous glands, dermis, adipocytes, cartilage, smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. Internal tissues such as the heart, kidney, muscle and spinal cord respond to damage by showing significantly reduced inflammation and improved regeneration responses. The reason for this improved ability may lie in the immune system which shows a blunted inflammatory response to injury compared to that of the typical mammal, but we also show that there are distinct biomechanical properties of Acomys tissues. Examining the regenerative behavior of closely related mammals may provide insights into the evolution of this remarkable property.

Keywords: mammalian regeneration, spiny mouse, Acomys, muscle regeneration, heart regeneration, skin regeneration, spinal cord regeneration, kidney regeneration, ear regeneration

Introduction

If you pose the question – can mammals regenerate? - the typical reply is likely to be no. Certainly not compared to the prodigious powers displayed by zebrafish and salamanders. This impression is probably prevalent because we all have scars on our skin, the heart fibroses after a myocardial infarction and ends up killing us, and paraplegia is the likely result of spinal cord injury. But if we delve a little more deeply then there are actually some tissues with surprising regenerative powers even in mammals. Skeletal muscle regenerates extremely well after certain types of damage [1], the liver can regenerate provided it is not chronically damaged [2], deer antlers regenerate each year covered by full thickness skin [3], postnatal mice and rats can regenerate the heart even after amputation of the apex of the ventricle [4,5], embryonic skin heals scarlessly [6], and childrens’ fingertips can regenerate after amputation as can the tips of adult mouse digits [7, 8]. Perhaps these are the remaining vestiges of a formerly widespread regenerative ability in mammals which has been lost in evolution. If so, perhaps not all mammals have lost regenerative ability and some have retained it. After all, we currently have surveyed very few of the 5400 species of mammals for regeneration so there may be some mammals that can regenerate very well but have yet to be discovered. We suggest that spiny mice of the genus Acomys are one such example of regenerative powers which have been evolutionarily conserved.

There are 18 species of Acomys in the genus which are characterized by spine-like hairs on the dorsum and they are in the subfamily called Deomyinae. The closest relatives to this subfamily are the gerbils and not the old world mice and rats on which most mammalian regenerative studies are conducted. A phylogenetic study of the distribution of regenerative powers among rodents would be fascinating because of the remarkable regeneration that Acomys species display as we now describe.

Skin

Following full-thickness dorsal skin excisional wounds of 4 mm to 1.5 cm, Acomys is capable of regenerating hairs, erector pili smooth muscle, sebaceous glands, panniculus carnosus (PC) skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and dermis [9]. The same wound in the lab mouse, Mus, forms a hairless scar with dense collagenous dermis and no PC muscle. After wounding Acomys re-epithelializes the wound faster than Mus an observation also seen in in vitro scratch assays using isolated keratinocytes [10]. The Mus wound ECM is dense and composed mostly of collagen I, whereas that of Acomys is porous and composed of collagen III [9]. Microarray and RTPCR data have revealed that at least 8 collagen types are highly upregulated in Mus, with collagen XII being upregulated up to 30-fold after wounding. Comparatively, there are fewer collagens upregulated in the Acomys wound [11] and they display profiles that are reminiscent of fetal wounds, which highly express collagens III and V [12]. Proteomic analysis corroborated this and also revealed that Acomys wounds exhibit increased levels of extracellular matrix remodeling proteases [13]. Between 3 and 4 weeks post-injury, hairs regenerated in the Acomys wound bed but none were found in Mus [9]. Compared to Mus, uninjured Acomys skin contains a larger hair bulge with a high expression of the stem cell markers CD34, K15 and Sox2 [14] and since hairs are regenerated in the Acomys skin it means that the new stem cell niches of the hair bulge, sebaceous gland and dermal papilla can be respecified, the former two presumably from the basal cells of the newly formed wound epidermis and the latter from the dermal fibroblasts (Figure 1).

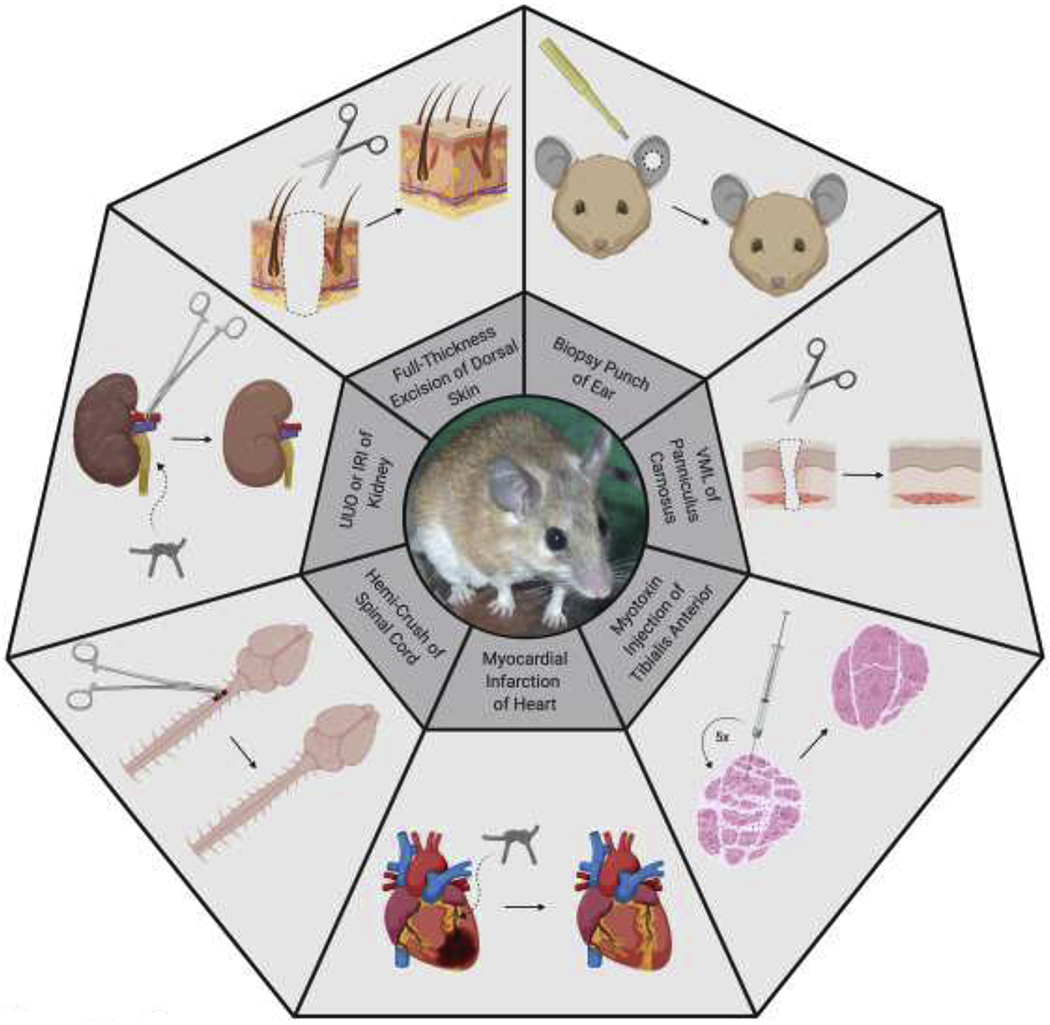

Figure 1.

Summary of the organs and tissues in Acomys that have been investigated for regenerative ability and the results of those experiments. In the centre is an Acomys cahirinus. The experiments described in the text are shown here. From the top going clockwise are: a biopsy punch through the ear shows a 4mm circle through the left ear regenerating perfectly; a VML of the skeletal muscle in the skin (the panniculus carnosus) is induced when full thickness skin is removed and the diagram shows that it can regenerate; when a myotoxin such as cardiotoxin is injected into the skeletal muscle and this is repeated five time the muscle still regenerates perfectly; when a myocardial infarction is induced by tying off the left descending coronary artery then the damage can be partially repaired; when a hemi-crush of the spinal cord is performed there is far less fibrosis at the site of injury than normal and a different set of genes are induced; when the kidney is damaged by obstructing the ureter or by inducing temporary ischemia then there is far less fibrosis; when full thickenss skin is removed then all of the component including hairs and sebaceous glands can regenerate without a scar. VML = volumetric muscle loss, UUO = unilateral ureteral obstruction, IRI = ischemia reperfusion injury.

In another type of injury to the skin, that of a full thickness burn injury Acomys was also found to regenerate perfectly in contrast to the hairless scar produced by Mus [15].

Ear Punches

Following ear biopsy punches of 2 mm to 8 mm, Acomys is capable of wound closure and regeneration of the missing tissue. In addition to the accessory organs that regenerated in the dorsal skin (above), Acomys also regenerated cartilage in its ears [9; 16]. Although ear cells re-enter the cell cycle in both Acomys and Mus, only Acomys cells progress through the cell cycle and ultimately proliferate. The regenerating Acomys ear demonstrated all the characteristics of a mammalian blastema including being able to form a wound epidermis, maintaining a pro-regenerative ECM, accumulating dividing mesenchymal cells, and becoming innervated. Thus, Acomys ear regeneration is epimorphic, similar to the blastema-mediated regeneration observed in salamander limb and zebrafish fin regeneration. Importantly, wound size does not impact regenerative ability, and all healthy Acomys adults are capable of regeneration [17] (Figure 1).

Skeletal Muscle

Myotoxins which cause breakdown of the sarcolemma are typically injected into skeletal muscle to examine its regenerative ability. In response to this acute damage, Acomys tibialis anterior muscle regenerated in 8 days, 2-3 days faster than Mus. qPCR data showed that Acomys exhibited lower levels of NF-kB, indicative of inflammation, and TGFβ-1 and collagens, indicative of fibrosis, as well as higher levels Cxcl12, an anti-inflammatory cytokine. In response to chronic damage in the form of multiple rounds of repeated myotoxin injections (5 of them), Acomys was able to regenerate perfectly; however, Mus was unable to do so, instead producing adipocytes throughout the muscle generating a histological picture reminiscent of Duchenne muscular dystrophy [18] (Figure 1).

Acomys also demonstrated the first known case of de novo regeneration of skeletal muscle in the absence of an existing, instructive extracellular matrix. This phenomenon is termed volumetric muscle loss (VML). Following dermal skin excision wounding, Acomys regenerates the panniculus carnosus (PC) of the skin which re-expresses adult muscle myosins and displays neuromuscular junctions. Immediately after injury, myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) are downregulated in both Acomys and Mus. After 2 weeks, Acomys MRF levels increase to normal, indicating muscle regeneration. Histological analysis shows newly formed myofibers positive for embryonic myosin differentiating in the Acomys wound bed. Embryonic myosin is up-regulated 450-fold whereas in Mus it is barely detectable at the wound margins [19] (Figure 1). Similar PC muscle regeneration was observed in Acomys following burn injury as described above [15].

Heart

Myocardial infarction (MI) was induced via ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Following this injury, Acomys exhibited an infarct area that was 4-fold smaller and displayed increased coronary microvasculature compared to Mus. In the left ventricle of Acomys, over twice as many BrdU-positive, proliferating cardiomyocytes were observed compared to Mus. Four weeks postinjury, MRI showed that Acomys left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) had returned to baseline levels observed in sham animals, whereas Mus levels remained significantly lower than their sham counterparts. Furthermore, wall ventricular thickness was significantly lower in Mus treated with MI compared to sham animals, but no such difference was observed between sham and treated groups in Acomys. Increased expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and certain microRNAs, which could have cardioprotective effects, were observed in Acomys [20, 21, 22] (Figure 1).

Spinal Cord

A C3/4 lateral dorsal hemi-crush injury was induced using forceps to damage the spinal cord. Acomys exhibited lower levels of inflammation and scarring compared to Mus. Acomys resumed bladder voiding ability 2 days after injury, while it took over 2 weeks for Mus to regain the same ability. RT2 Profiler PCR arrays (Qiagen) for wound healing and neurogenesis were used to assay both species. Generally, Mus upregulated more genes associated with wound healing, whereas Acomys upregulated more genes associated with neurogenesis. Mus upregulated pro-inflammatory, extracellular matrix remodeling, and fibrosis genes, while Acomys upregulated WNT-signaling, neural stem cell, and axonal guidance genes. Growth factor and Tgfbl genes were upregulated in both species. Compared to Mus, Acomys injuries exhibited decreased levels of collagen IV and GFAP immunostaining, two major components of the spinal cord scar [23] (Figure 1).

Kidney

Unilateral uretal obstruction (UUO) was conducted by ligating the left ureter with 4–0 silk. After 2 weeks of obstruction Acomys maintained normal anatomic structure and kidney weights, while Mus kidney weights rapidly declined due to fibrosis. Extensive interstitial matrix fibrosis was observed in Mus, but none was evident in Acomys. Even after 3 weeks of obstruction, there was no difference in total collagen levels between obstructed and contralateral kidneys in Acomys. Cdh1 protein levels were used to measure tubular integrity, a surrogate for kidney function. Acomys Cdh1 was maintained in the injured kidney, whereas Mus Cdh1 levels progressively declined. Unilateral ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) was also conducted by placing a vascular clamp on the left renal pedicle for 40 minutes. Histologically and functionally, Acomys and Mus were equivalently injured when analyzed at 24 hours and 72 hours postsurgery Again, fibrosis was observed in Mus, while Acomys was able to recover both kidney structure and function. After 16 days, Acomys exhibited normal blood urea nitrogen levels, while Mus exhibited extremely elevated levels indicative of kidney failure [24] (Figure 1).

What is the cellular and molecular basis of this regenerative behavior?

There are two clear physiological differences between Acomys and Mus that are systemic, and therefore relevant to all the tissues described above. These distinctions may begin to explain the basis of regenerative behavior versus fibrosis. The first is the immune system and its components since a strong inflammatory response prevents infection by killing pathogens but can also damage tissue, induce fibrosis and inhibit regeneration. A blunted immune system is characteristic of the mammalian fetus and lower vertebrates capable of regeneration and the inverse relationship between advanced immune systems and the ability to regenerate is well recorded [25].

In line with this concept Acomys has a relatively dampened response following injury, characterized by low or absent expression of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. In contrast, Mus strongly expresses several inflammatory pathway genes and proteins after wounding [11, 12, 13]. Acomys blood also has a lower proportion of neutrophils and a higher proportion of lymphocytes compared to Mus [11]. The differential blood compositions necessitate that each species defends against pathogens differently. In Mus, neutrophils play an important role in killing bacteria. To compensate for its deficiency of neutrophils, the serum of Acomys blood predominantly kills bacteria; which decreases inflammation from neutrophils while still protecting against infection [26]. Moreover, different T cell populations were found to infiltrate regenerating and non-regenerating wounds. In Mus, inactivated T helper cells accumulate. However, there is an early influx of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells in Acomys, which could potentially be modulating inflammation and encouraging regeneration rather than fibrosis [27].

Macrophage profiles following injury differ between Acomys and Mus. In vitro experimentation has shown that F4/80, a pan macrophage marker in Mus, only marks M1 macrophages in Acomys [28]. Following skin excision, burn, ear punch, and myotoxin injection injuries, no F4/80-positive M1 macrophages are found in the Acomys wound, whereas F4/80 staining is abundant in Mus throughout the wound healing process [11, 15, 18, 28]. Following kidney injury, F4/80 levels are significantly lower in Acomys than in Mus [24]. While CD86-positive M1 macrophages were present in Acomys burn wounds and ear punches [15, 28], none were found in Acomys myotoxin wounds [18]. However, Acomys and Mus wounds have similar numbers of CD206-positive M2 macrophages [18, 19, 28]. This lack of M1 but abundance of M2 macrophages during regeneration may be explained in part by the fact that Acomys upregulates Il10, which facilitates macrophage transition from M1 to M2 [19]. When macrophages are depleted via clodronate liposomes, Acomys ear punch closure is inhibited, signifying that macrophages are necessary for regeneration. Macrophages are a source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production after injury, which may serve as a pro-regenerative signal in Acomys. ROS production is higher and prolonged in Acomys [28], and Acomys fibroblasts are resistant to the ROS-induced cellular senescence and decreased proliferation observed in Mus [29].

The second systemic difference between Acomys and Mus tissues is a mechanical one. Acomys demonstrates the first known instance of mammalian skin autotomy, allowing its skin to be sloughed off in order to escape predation [9]. Accordingly, Acomys skin is 20 times weaker than Mus skin, requiring 77 times less energy to break. Acomys has a thicker layer of adipose than Mus, and it is postulated that this could contribute to its observed weakness [14]. But this softness is not only a property of the skin but also of skeletal [18] and cardiac muscle and biomechanical differences are also apparent in cultured cells [10]. In response to a wound, fibroblasts are activated to become myofibroblasts expressing increased levels of aSMA. In vitro, Mus fibroblasts can be led down this path by increasing substrate stiffness; however, Acomys fibroblasts do not become activated when cultured on stiffer substrates. Furthermore, Acomys fibroblasts generate lower contractile forces than Mus fibroblasts. Finally, compared to Mus fibroblasts, Acomys fibroblasts produce much less collagen in vitro. In three-dimensional culture, Mus fibroblasts remodeled their surroundings, whereas Acomys fibroblasts did not. Thus, the resulting matrices were stiffer for Mus fibroblasts than Acomys [10].

Conclusion

Each tissue in Acomys that has been examined, as described above, shows a non-fibrotic, regenerative response to damage suggesting that this genus has evolved a property which affects all the tissues of the body. It will be important, therefore, to continue the survey of regenerative abilities across further tissues and organs of the body such as the brain, retina and long bone cartilage which are subject to traumatic damage and of medical relevance to determine whether the regenerative response is a body-wide property. This will give us important clues for deciphering the underlying mechanisms. It will also be important from an evolutionary point of view to examine the regenerative ability of closely related genera such as Lophuromys (the brush-furred mouse), Deomys (the Congo forest mouse) or Uranomys (Rudd’s mouse) to determine whether regenerative ability is more widely distributed than Acomys and to make genomic comparisons to identify mechanisms. Hopefully, these future investigations will provide some mechanistic answers to how Acomys regenerates so that we can translate these findings to stimulate human tissue regeneration.

Highlights.

Acomys (spiny mouse) is a newly discovered mammal which can regenerate several tissues

The skin regenerates after removal or burn injury and so do ear punches

Internal organs respond to ischemia by greatly reduced fibrosis

A blunted immune system may play a role the regenerative behavior

A survey of regeneration in closely related genera may provide evolutionary insights into mammalian regeneration

Acknowledgements

Work from the authors’ lab has been funded by W.M. Keck Foundation, National Science Foundation (1636007) and National Institutes of Health (1R21 0D023210, 1R21 0D028209).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Musarò A: The Basis of Muscle Regeneration. Kuang S, ed. Adv Biol 2014, 612471. doi: 10.1155/2014/612471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalopoulos GK: Hepatostat: Liver regeneration and normal liver tissue maintenance. Hepatology 2017, 65:1384–1392. doi: 10.1002/hep.28988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss R: Deer Antlers: Regeneration, Function and Evolution. 1st Edition. Academic Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA: Transient Regenerative Potential of the Neonatal Mouse Heart. Science 2011, 331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.*.Wang H, Paulsen JM, Hironaka EC, Shin HS, Farry JM, Thakore AD, Jung J, Lucian HJ, Eskandari A, Anilkumar S, et al. Natural Heart Regeneration in a Neonatal Rat Myocardial Infarction Model. Cells 2020, 9:229. doi: 10.3390/cells9010229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A demonstration that the neonatal rat heart can regenerate after a myocardial infarction. Increased levels of cardiomyocyte proliferation are observed and by 3 weeks the ejection fraction was the same as controls.

- 6.Yates CC, Hebda P, Wells A: Skin Wound Healing and Scarring: Fetal Wounds and Regenerative Restitution. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today Rev 2012, 96:325–333. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illingworth CM: Trapped fingers and amputated finger tips in children. J Pediatr Surg 1974, 9:853–858. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(74)80220-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simkin J, Han M, Yu L, Yan M, Muneoka K: The Mouse Digit Tip: From Wound Healing to Regeneration. In: Wound Regeneration and Repair: Methods and Protocols. Edited by Gourdie RG, Myers TA. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013:419–435. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.**.Seifert AW, Kiama SG, Seifert MG, Goheen JR, Palmer TM, Maden M: Skin shedding and tissue regeneration in African spiny mice (Acomys). Nature 2012, 489:561–565. 10.1038/nature11499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first report in this genus of mammals of regeneration of skin, relating this to its weakness and readiness to tear and of ear punches relating this to the presence of a blastema.

- 10.Stewart DC, Serrano PN, Rubiano A, Yokosawa R, Sandler J, Mukhtar M, Brant JO, Maden M, Simmons CS: Unique behavior of dermal cells from regenerative mammal, the African Spiny Mouse, in response to substrate stiffness. J Biomech 2018, 81:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brant JO, Yoon JH, Polvadore T, Barbazuk WB, Maden M: Cellular events during scar-free skin regeneration in the spiny mouse, Acomys. Wound Repair Regen 2016, 24:75–88. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brant JO, Lopez M-C, Baker HV, Barbazuk WB, Maden M: A Comparative Analysis of Gene Expression Profiles during Skin Regeneration in Mus and Acomys. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142931. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon JH, Cho K, Garrett TJ, Finch P, Maden M: Comparative Proteomic Analysis in Scar-Free Skin Regeneration in Acomys cahirinus and Scarring Mus musculus. Sci Rep. 2020, 10:166. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56823-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang T-X, Harn HI-C, Ou K-L, Lei M, Chuong C-M: Comparative regenerative biology of spiny (Acomys cahirinus) and laboratory (Mus musculus) mouse skin. Exp Dermatol 2019, 28:442–449. doi: 10.1111/exd.13899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maden M: Optimal skin regeneration after full thickness thermal burn injury in the spiny mouse, Acomys cahirinus. Burns 2018, 44:1509–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matias Santos D, Rita AM, Casanellas I, Ova AB, Araujo IM, Power D, Tiscornia G: Ear wound regeneration in the African spiny mouse Acomys cahirinus. Regeneration 2016, 3:52–61. doi: 10.1002/reg2.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gawriluk TR, Simkin J, Thompson KL, Biswas SK, Clare-Salzler Z, Kimani SG, Smith JS, Ezenwa VO, Seifert AW: Comparative analysis of ear-hole closure identifies epimorphic regeneration as a discrete trait in mammals. Nat Commun. 2016, 7:11164. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maden M, Brant JO, Rubiano A, Sandoval AGW, Simmons C, Mitchell R, Collin-Hooper H, Jacobson J, Omairi S, Patel K: Perfect chronic skeletal muscle regeneration in adult spiny mice, Acomys cahirinus. Sci Rep. 2018, 8:8920. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27178-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.*.Brant JO, Boatwright JL, Davenport R, Sandoval AGW, Maden M, Barbazuk WB: Comparative transcriptomic analysis of dermal wound healing reveals de novo skeletal muscle regeneration in Acomys cahirinus. PLoS One 2019, 14:e0216228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Transcriptome analysis of skin regeneration in Acomys versus Mus showing enriched pathways associated with regeneration or fibrosis. Genes related to muscle development were highly up-regulated in Acomys confirming that the skeletal muscle can regenerate without any connective tissue scaffold.

- 20.Qi Y, Vohra R, Zhang J, Wang L, Krause E, Guzzo DS, Walter GA, Katovich MJ, Maden M, Raizada MK, Pepine CJ: Abstract 14166: Cardiac Function is Protected From Ischemic Injury in African Spiny Mice. Circulation. 2015, 132(suppl_3):A14166–A14166. doi: 10.1161/circ.132.suppl_3.14166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Kumar A, Vohra R, Walter GA, Maden M, Katovich MJ, Raizada M, Pepine CJ: Intrinsic increased ACE2 expression protects spiny mouse Acomys cahirinus against ischemic-induced cardiac dysfunction. FASEB J. 2016, 30(supplement):lb561–lb561. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.30.1_supplement.lb561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi Y, Goel R, Mandloi AS, Vohra R, Wlater G, Joshua YF, Gu T, Katovich MJ, Aranda JM, Maden M, Raizada MK, Pepine CJ: Spiny mouse is protected from ischemia induced cardiac injury: leading role of microRNAs. FASEB J. 2017, 31(supplement):721.4–721.4. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.721.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streeter KA, Sunshine MD, Brant JO, Sandoval AGW, Maden M, Fuller DD: Molecular and histologic outcomes following spinal cord injury in spiny mice, Acomys cahirinus. J Comp Neurol 2019, 528:1535–1547. doi: 10.1002/cne.24836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.*.Okamura DM, Brewer CM, Wakenight P, Bahrami N, Bernardi K, Tran A, Olson J, Shi X, Piliponsky AM, Nelson BR, Beier DR, Millen KM, Majewski MW: Scarless repair of acute and chronic kidney injury in African Spiny mice. bioRxiv. May 2018, 315069. doi: 10.1101/315069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Demonstration that Acomys kidney can recover from both ischemia and ureteric obstruction with little inflammatory response and with greatly reduced fibrosis compared to Mus.

- 25.Mescher AL, Neff AW: Regenerative Capacity and the Developing Immune System. In Regenerative Medicine I: Theories, Models and Methods. Edited by Yannas IV. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg; 2005:39–66. doi: 10.1007/b99966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cyr JL, Gawriluk TR, Kimani JM, Rada B, Watford WT, Kiama SG, Seifert AW, Ezenwa VO: Regeneration-Competent and -Incompetent Murids Differ in Neutrophil Quantity and Function. Integr Comp Biol 2019, 59:1138–1149. doi: 10.1093/icb/icz023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gawriluk TR, Simkin J, Hacker CK, Kimani JM, Kiama SG, Ezenwa VO, Seifert AW: Mammalian musculoskeletal regeneration is associated with reduced inflammatory cytokines and an influx of T cells. bioRxiv. August 2019,723783. doi: 10.1101/723783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simkin J, Gawriluk TR, Gensel JC, Seifert AW: Macrophages are necessary for epimorphic regeneration in African spiny mice. Elife 2017, 6:e24623. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*.Saxena S, Vekaria H, Sullivan PG, Seifert AW: Connective tissue fibroblasts from highly regenerative mammals are refractory to ROS-induced cellular senescence. Nat Commun 2019, 10:4400. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12398-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comparisons between the fibroblasts from the ears of regenerative (Acomys and rabbit) and non-regenerative (Mus and rat) species reveal that regenerative fibroblasts are resistant to cell senescence induced by H2O2 because it is reduced efficiently without inducing mitochondrial dysfunction, unlike cells from non-regenerative species.