Abstract

Study objective:

We identify the incidence, nature, and consequences of medication errors among acutely ill and injured children receiving care in a sample of rural emergency departments (EDs).

Methods:

Two pediatric pharmacists applied a medication error data collection instrument to the medical records of all critically ill children (highest triage category) treated in 4 northern California rural EDs between January 2000 and June 2003. Physician-related medication errors were defined as those involving wrong dose, wrong or inappropriate medication for condition, wrong route, or wrong dosage form. Wrong dose was determined by preset criteria, with doses above or below 10% to 25% of correct dose considered errors, depending on class of medication. Medication errors were classified into categories A through I under 3 broader categories, including errors having the potential to cause harm (A), errors that cause no harm (B to D), and errors that cause harm to the patient (E to I).

Results:

Complete data were available from 177 (97.3%) of the 182 patients identified as having been triaged in the highest category during the study period. A total of 84 medication errors were identified among 69 patients, resulting in a medication error incidence of 39.0%. Twenty-four physician-related medication errors were identified among 21 patients, resulting in a physician-related medication error incidence of 11.9%. Among the 69 patients with medication errors, 11 had errors categorized as having the potential to cause harm (15.9%), and 58 had errors categorized as causing no harm (85.5%).

Conclusion:

We found a high incidence of medication errors and physician-related medication errors among the acutely ill and injured children presenting to rural EDs in northern California. None of the medication errors identified caused harm to the patients included in this study.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Medication error rates among hospitalized children occur up to 3 times the rates reported among hospitalized adult patients.1 The risk for medication errors among pediatric patients receiving care in the emergency department (ED), where critical situations are common and inpatient resources are often not available, is likely to be even higher than among inpatients.2,3 The difficulty in applying weight-based dosing for pediatric patients in a setting in which staff may be less familiar with pediatric dosing compounds this risk. Despite that approximately one quarter of the pediatric population receives care in EDs each year in the United States,4 little is known about medication errors among these children.5

There have been few reports investigating the incidence of medication errors among pediatric inpatients. Among these studies, the results have varied widely, with incidences ranging from 0.03 to 55 medication errors per 100 patients treated.1,6,7 Only 1 study has investigated the incidence of medication errors among children treated in the ED, and this study found medication errors in 10% of the treated population.2 Of note, no data exist on medication error rates among pediatric patients treated in rural or nonacademic EDs. Further, there is no single, standardized approach to retrospectively measure the incidence of medication errors among pediatric patients. For example, some reports of medication error rates use methods that do not explicitly define types of medication errors, such as what dose of a medication is considered “too high,” whereas other reports use methods that are inherently biased in identifying errors, such as the use of incident reporting systems.6

Importance

It is important to study the incidence and nature of pediatric medication errors in rural EDs for a number of reasons. First, many children receive care in rural EDs, with 41% of the nation’s community hospitals designated as rural, according to the 2006 American Hospital Guide.8 Second, children treated in rural EDs may be at a higher risk of medication errors because rural EDs treat children infrequently5 and often lack the resources, training, and expertise available at larger hospitals.9,10 Also, most rural hospitals cannot afford many of the interventions used to reduce the frequency of medication errors, such as full-time pharmacists, electronic medical record systems, or computerized physician order entry. Therefore, identifying factors associated with medication errors in rural EDs is critical to the derivation of more affordable and immediately available interventions.

Goals of This Investigation

In this study, we first developed an instrument for medication error data collection and a methodology to identify errors in the ED by using retrospective record review. Once this instrument was developed, our primary goal was to investigate the incidence, nature, and consequences of pediatric medication errors in acutely ill and injured children presenting to 4 rural northern California EDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was an observational study in which we analyzed the incidence of medication error with a customized medication error instrument in a cohort of acutely ill and injured pediatric patients at 4 rural EDs in northern California.

Setting

This study is part of a larger project designed to investigate interventions aimed at improving the quality of care and reducing medication errors among acutely ill and injured children presenting to rural, underserved EDs. Because of this, we selected 4 hospitals located in designated rural areas as defined by California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development11 and rural or small town by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Office of Rural Health Policy.12 The 4 hospitals are also located in “underserved” communities, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration’s definitions of health professional shortage areas, medically underserved areas, and medically underserved populations.12,13 The EDs at these hospitals treat between 700 and 2,000 children annually, with a total patient census between 2,200 and 7,500, and are staffed by physicians with varied training backgrounds, including emergency medicine, internal medicine, family practice and general surgery.

None of the study hospitals have computerized medication orders, software to verify dosing or administration technique, or a verification system for checking allergies or contraindications to medications. All 4 of the participating EDs dispense medications without any pharmacist participation.

Selection of Participants

We included any child older than 1 day but younger than 17 years who was triaged in the highest of 3 acuity triage levels and who presented to one of the participating EDs between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2003. All 4 of the participating EDs use a 3-level triage system, with almost identical definitions for the highest acuity level. We selected the sickest patients because we wanted to focus our measurement of medication errors on patients who were at highest risk of medication errors14 and those who would benefit most from interventions aimed at reducing medication errors in the ED. We identified patients by reviewing paper (3 EDs) or computer (1 ED) logbooks, which included information on each patient’s age and triage level.

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee.

Methods of Measurement

We developed an instrument to identify and categorize medication errors by using retrospective medical record review. We reviewed the literature on medication errors and modified 2 previously published, similar, and standardized instruments: the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention and the Medication Errors Reporting Program from the United States Pharmacopeia.1,15 The slight modifications were made to make the instrument more applicable to chart review of ED records.

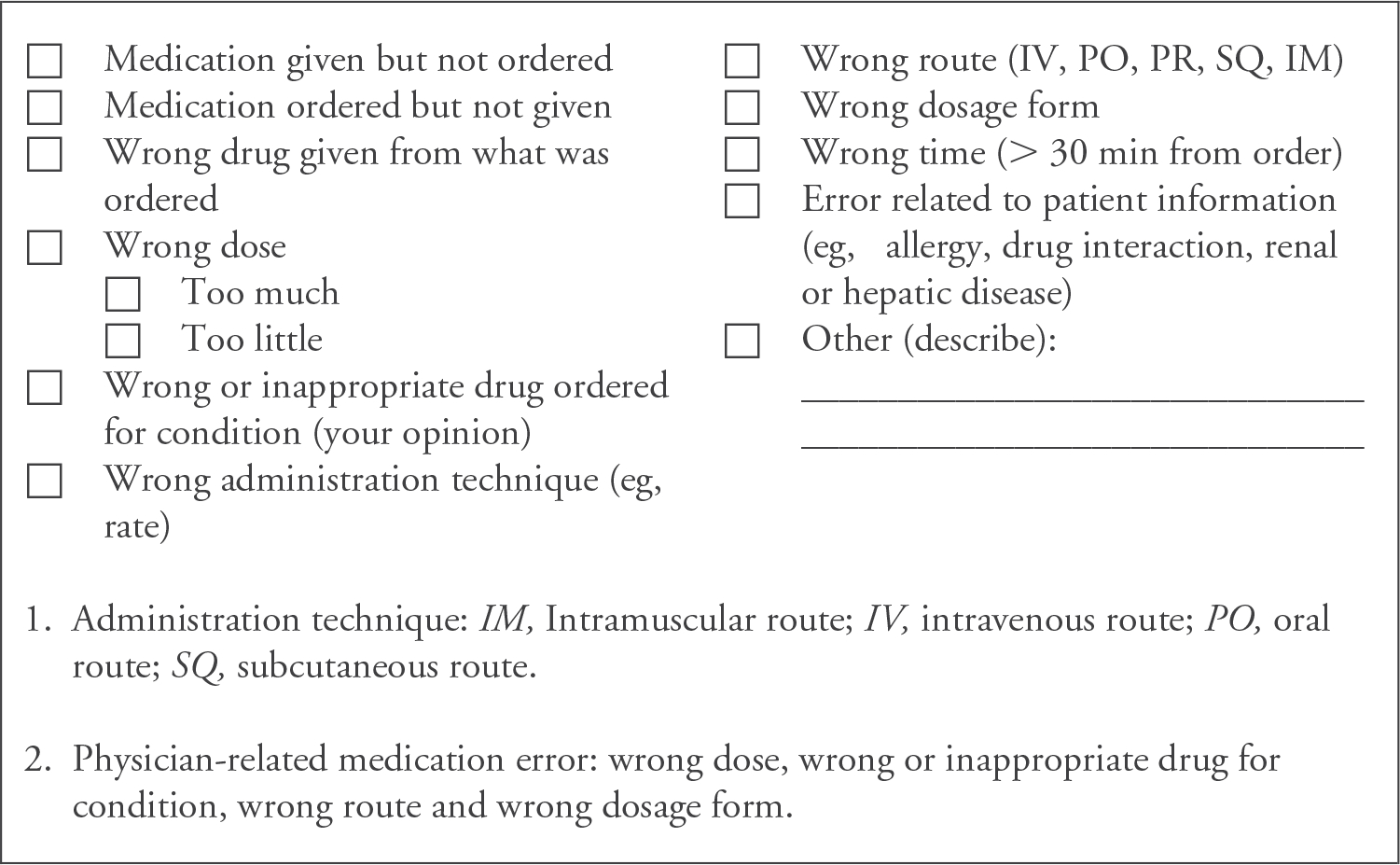

All medications ordered or administered in the ED were evaluated. The “error types”1,15 were categorized as shown in the Figure and included medication given but not ordered; medication ordered but not given; wrong drug given from what was ordered; wrong dose; wrong or inappropriate drug for condition; wrong administration technique, wrong route; wrong dosage form; wrong time; and error related to patient information. Although “medication given but not ordered” likely includes verbal orders, these are still considered medication errors by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, United States Pharmacopeia, and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.1,15,16 The other types of errors identified by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention and previous authors (ie, wrong frequency, transcription, wrong patient, illegible order, or wrong date) were considered either not applicable to the ED setting or not ascertainable by retrospective medical record review.1,17

Figure.

Medication error data collection instrument.

Before examining the data, we established guidelines that would allow for classification of what constituted a “wrong dose,” with a categorization of the most common medications prescribed in the pediatric ED, as shown in Table 1. A similar approach was taken by Kozer et al,2 who defined a medication error as the dose differing from the recommended dose by 20% or more. We refined this method by generating different acceptable ranges outside the upper and lower limits of the ranges published by Lexi-Comp’s Pediatric Dosage Handbook18 because different categories of medications have different dosing ranges and are associated with variable toxicities outside of these ranges. The categories and acceptable ranges were determined by 2 pediatric critical care physicians, 1 pediatric emergency physician, and 2 pediatric pharmacists.

Table 1.

Drug categories and acceptable ranges for dosing errors.*

| Drug category | Dosing range |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1. Antipyretics | ±20% |

| 2. Antibiotics | ±25% |

| 3. Steroids (eg, methyl prednisone, prednisone, prednisolone) | ±25% |

| 4. Narcotics (eg, fentanyl, morphine, codeine) | ±25% |

| 5. Anxiolytics (eg, lorazepam, midazolam, diazepam) | ± 20% |

| 6. Code medications (eg, boluses of atropine, epinephrine, lidocaine, adenosine, HCO3) | ± 10% |

| 7. Anesthetics (eg, ketamine, etomidate, thiopental, pentobarbital) | ± 10% |

| 8. Paralytics (eg, succinyl choline, vecuronium, rocuronium) | ± 20% |

| 9. Inotropics, vasoactives, cardiac medications (eg, epinephrine, lidocaine, dopamine) | ± 10% |

| 10. Insulin drip | ± 10% |

| 11. Dextrose and electrolytes (eg, potassium, calcium) | ± 20% |

| 12. Anticonvulsants (eg, phenytoin, lorazepam) | ± 20% |

To explicitly define “wrong dose,” 2 pediatric critical care physicians, 1 pediatric emergency physician, and 2 pediatric pharmacists established “acceptable ranges” above and below the upper and lower limits of the ranges published by Lexi-Comp’s Pediatric Dosage Handbook.18

The “sources of error” were categorized into physician-related errors and other errors. We were most interested in investigating physician-related errors because other errors are more likely related to incomplete recording or lack of documentation in the ED. Physician-related medication errors were defined a priori as those involving wrong dose, wrong or inappropriate medication for condition, wrong route, or wrong dosage form.

We classified medication error outcomes into categories from A through I according to categories developed by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention.17 The pharmacists independently determined the medication error outcome from reviewing the ED record. Category A was defined as a medication error that had the potential to cause harm. Categories B to D were defined as medication errors that cause no harm to the patient. Categories E to I were defined as medication errors that cause harm to the patient.

Data Collection and Processing

First, the complete ED records of children meeting entrance criteria were photocopied. The ED records included all triage, nursing, and physician documentation. Next, patient records had all hospital and protected health information blacked out. A research assistant abstracted factors that might be related to medication errors and physician-related information (blacked out after abstraction) from the medical records.1,2,19 Factors that might be related to medication errors included age and sex; diagnostic and “triage” factors, including whether the ED visit was for an injury; mode of arrival to the ED (ambulance or other); day of week (as individual days); time of presentation (nighttime, defined as 7 PM to 7 AM, and daytime); and variables required to calculate the Pediatric Risk of Admission score.16,20 We also collected information on the physician training (categorized as “emergency medicine” or “other,” which included family practice, internal medicine, and general surgery) from the medical staff secretary from each hospital. The research assistant was trained with regard to the data form, data abstraction, and data entry during 3 1-hour training sessions. All abstracted data were entered by the research assistant into a Microsoft Access 2000 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Finally, the instrument was applied to blinded medical records independently by 2 pediatric pharmacists according to previously published guidelines.1,15 We only slightly refined our medication error definitions after some initial testing on 20 records by both pharmacists. The pharmacists reviewing the records were not involved in the care of study participants. Each record was reviewed and assessed independently by the pharmacists, and then assessments were reviewed to determine interrater reliability. The method for adjudicating differences was to have unblinded review and discussion of the chart with the 2 pharmacists in the presence of a pediatric critical care physician to resolve discrepancies.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome variable was total medication errors, and secondary outcome variables were physician-related medication errors, nature of the medication error, and consequences of medication errors.

Primary Data Analysis

All data were entered in a Microsoft Access database, and analyses were conducted using Stata version 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive analysis was used for the demographics information, type of medication errors, and the medication error outcomes. The proportion of medication errors for the type of error was calculated for the total number of medication errors in the sample, for all the patients in the sample, and also for patients for whom medications were ordered or administered. Last, the physician-related medication errors were stratified according to the physician training.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

A total of 182 patients were identified from logbooks as having been triaged in the highest triage category during the study period at the 4 rural EDs. Of these, 177 (97.3%) medical records could be located for review of medication errors. Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample studied. Eighty-eight (49.7%) patients were male, with mean and median age of 7.6 years (SD 5.8) and 7.4 years, respectively. The patients in the study had a mean Pediatric Risk of Admission score of 13 (SD 12.0). A total of 135 (76.3%) patients had a medication ordered or received a medication while in the ED.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study sample (n = 177).

| Demographics | Total (N=177) |

Medication Error (N=69) |

No Medication Error (N=108)* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, y (median) | 7.6 (7.4) | 7.9 (8.0) | 7.4 (7.7) |

| Sex, male, No. (%) | 88 (49.7) | 41 (52.4) | 47 (43.5) |

| Injury-related reason for ED visit, No. (%) | 60 (33.9) | 23 (33.3) | 37 (34.3) |

| Patients arriving by ambulance, No. (%) | 63 (35.6) | 23 (33.3) | 40 (37.0) |

| Pediatric Risk of Admission Score, mean (SD) | 13 (12.0) | 13.9 (13.7) | 12.1 (10.8) |

Sixty-six (61%) of patients with no medication error had a medication ordered or administered.

Forty-seven physicians treated the 177 patients in the 4 rural EDs, with a median of 2 cases per physician and a range of 1 to 21. Seventy-four (41.8%) patients were treated by physicians trained in family medicine, 43 (24.3%) patients were treated by physicians trained in emergency medicine, 43 (24.3%) patients were treated by physicians trained in internal medicine, and 17 (9.6%) patients were treated by physicians trained in general surgery. One hundred forty-one (79.7%) patients were treated by board-certified physicians. During the review process, 33 of 177 (18.6%) medical records required adjudication because of interreviewer disagreements on whether medications were ordered, and 30 of 177 (17%) records required adjudication because of disagreements on whether there was a medication error. The κ statistics before adjudication were 0.55 and 0.66, respectively. A table summarizing all patients with prediction errors can be found in Appendix E1 (available online at http://www.annemergmed.com).

Main Results

Of the 177 medical records, 39.0% (69 of 177) were identified as having at least 1 medication error, representing 51.1% (69 of 135) of the ED visits in which a medication was ordered or administered. There were a total of 84 medication errors identified among the 69 patients. Among these 69 patients, 30.4% (21 of 69) were identified as having a physician-related medication error. Physician-related errors occurred in 11.9% (21 of 177) of the entire sample and 15.6% (21 of 135) of the patients for whom a medication was ordered or administered.

Table 3 shows the types of medication errors as determined by the reviewers. A total of 84 medication errors were identified in the medical records, of which 28.6% (24 of 84) were physician related. The most common medication error identified was “medication given but not ordered” (n = 40; 47.6%) followed by “medication ordered but not given” (n = 18; 21.4%). The most common physician-related medication error was wrong dose (n = 15; 62.5%). Among the 24 physician-related medication errors, 12 (50%) were found in patients treated by physicians trained in family medicine, 6 (25%) in patients treated by physicians trained in emergency medicine, 5 (21%) in patients treated by physicians trained in internal medicine, and 1 (4%) in patients treated by general surgeons.

Table 3.

Incidence and type of errors.

| Medication Error Type | No. | Medication Errors of All Medication Errors, % (n=84) | Medication Errors Among Patients With Medications Ordered or Administered, % (n=135) | Medication Errors Among All Patients in Cohort, % (n=177) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Medication given but not ordered | 40 | 47.6 | 29.6 | 22.6 |

| Medication ordered but not given | 18 | 21.4 | 13.3 | 10.2 |

| Wrong drug given from what was ordered | 1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Wrong dosage † | ||||

| Too much | 8 | 9.5 | 5.9 | 4.5 |

| Too little | 7 | 8.3 | 5.2 | 4.0 |

| Wrong or inappropriate drug for condition† | 4 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| Wrong administration technique | 1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Wrong route† | 4 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| Wrong dosage form† | 1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Total * | 84 | 100.0 | 62.2 | 47.5 |

A total of 84 medication errors were identified in 69 patients.

Physician-related medication error.

Table 4 shows error outcomes as identified by the reviewers. The most common error outcome was category C, indicating that the medication reached the patient but did not have the potential for harm, which occurred in 50 medication errors and 16 physician-related errors. The reviewers did not identify any error outcomes in the error outcome categories E to I (ie, a medication error that resulted in harm to the patient).

Table 4.

Medication error outcomes.

| Error Outcomes | All Errors (N) | Physician-Related Errors (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| A | Circumstances or events that have the capacity to cause harm | 11 | 2 |

| B | An error occurred but the treatment was not administered | 3 | 0 |

| C | Medication or procedure reached the patient but did not have the potential for harm | 48 | 14 |

| D | An error occurred that reached the patient, resulting in the need for increased patient monitoring but no patient harm | 7 | 5 |

| E | The need for treatment or intervention and caused temporary patient harm | 0 | 0 |

| F | Initial or prolonged hospitalization and caused temporary patient harm | 0 | 0 |

| G | Permanent patient harm | 0 | 0 |

| H | A near-death event (anaphylaxis, cardiac arrest) | 0 | 0 |

| I | A patient death | 0 | 0 |

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to our study. As with any retrospective medical record review, we were limited to the information that was available in the medical record. Therefore, we could have underestimated the frequency of some errors (eg, dosing errors may not have been documented) or overestimated the frequency of other errors (eg, medications ordered but not given may simply not have been recorded). The original reliability of the instrument was less than ideal but improved with modification of the error definitions and the adjudication in the presence of a physician. Further, the small number of outcomes precludes an accurate examination of reasons or associations with the medication errors. We also preselected our study sample to include only the sickest or highest triage patients, which likely resulted in our relatively high medication error rate compared to that of other studies that included all pediatric patients receiving care in the ED. Also, our sample of EDs was limited to 4 rural EDs treating between 2,200 and 7,500 patients per year and staffed by physicians with varied training; thus, our results may not be representative of other EDs. Last, we may have missed some medication error outcomes if complications occurred after discharge from the ED.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed an instrument that can be used retrospectively on patient records to evaluate the incidence and nature of medication errors that children experience while receiving care in the ED. With this instrument, we found that among the most acutely ill children treated in a sample of 4 rural EDs in northern California, the incidence of medication errors is high: 39% of all patients or 51.1% of patients who had medications ordered or who received medications. Most of these errors, however, could be the result of inadequate or missing documentation. We found physician-related errors in 11.9% of patients (15.6% error among patients who had medications ordered or who received medications), which represents 28.6% of all the medication errors.

Although the frequency and significance of medication errors and adverse drug events among adult patients are relatively well documented, few realize that pediatric patients typically experience even higher rates of medication errors.1,15 Further, previous investigations of medication errors among children receiving care in the ED have focused on suburban and urban hospitals.3,21,22 Our finding of an 11.9% physician-related medication error rate among acutely ill and injured children receiving care in EDs is consistent with previously reported medication error rates.2,23 However, our finding that only 17.9% of medication errors are errors in dosing is lower than that of previously reported medication error studies2,24 and that of a recent review article of 16 studies that found dosing errors as the most common type of medication error.6 The relatively lower rate of dosing errors in our study could be explained by the fact that we established explicit ranges for the dosing of medications, giving more flexibility to dosing (eg, allowing for up to 25% more than the maximum and minimum doses of antibiotics). This relatively low rate of dosing errors could also be explained by our relatively higher rates of errors that are related to documentation (medication order but not given and medication given but not ordered), which may be more likely in an ED setting, particularly in rural EDs where computerized physician order entry is not available.

We also found that patients with medication errors had higher mean Pediatric Risk of Admission scores (not significant) compared with patients with no medication error, which was similar to results of Kozer et al,2 who found that the most seriously ill patients were more likely to be subjected to prescribing errors. However, we reviewed the records of only patients in the highest triage category. It is possible that if we included the less sick patients, we would find that children with more severe injuries would experience a medication error.

There were several strengths to our study. First, we assimilated previously published medication error data collection tools and attempted to optimize our instrument by including questions particularly related to retrospective medical record review for children receiving care in the ED. We also developed explicit ranges of acceptable dosing to better define what constituted wrong doses. Although these ranges may not be agreed on by other investigators, having explicit ranges increases reliability in the identification of errors. Last, by having 2 pediatric pharmacists independently review the records, we believe that we improved the accuracy of the study’s results by increasing the reliability and validity.25

With regard to reducing the incidence of medication errors in the ED, several current interventions or system changes are possible. Some medication errors might be prevented by the presence of a general or pediatric pharmacist who would review medication orders from the ED, which is problematic because rural hospitals often cannot afford to staff the ED with dedicated pharmacists. Others have used computerized physician order entry and automated alert algorithms as a means of reducing errors.23,26 Unfortunately, the majority of rural hospitals do not have computerized medication order systems and, because of the financial costs, are unlikely to obtain or develop such systems in the near future.27 Other possible solutions include the use of the Broselow tape,28 using preprinted medication order sheets,29 and telemedicine or telepharmacy.

In conclusion, we developed a pediatric medication error collection tool and methodology that can be used to estimate the incidence, nature, and consequences of pediatric medication errors using retrospective medical record review in EDs. Using this instrument, we found a high rate of medication errors (39%) among the acutely ill and injured children presenting to rural EDs.

Editor’s Capsule Summary.

What is already known on this topic

Medications errors are not uncommon in the emergency department (ED). Because of the large variation in children’s weight, there is reason to believe that such errors may occur more frequently in children.

What question this study addressed

The frequency and kinds of medication errors in 177 urgently ill children in 4 rural EDs in northern California.

What this study adds to our knowledge

Errors occurred in half of the 135 patients who received medications. Fifteen percent of these errors were due to erroneous physician orders. No error was deemed to cause significant harm.

How this might change clinical practice

These data suggest that systems of care be redesigned to decrease the likelihood of medication errors in pediatric ED patients.

Funding and support:

By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article, that may create any potential conflict of interest. See the Manuscript Submission Agreement in this issue for examples of specific conflicts covered by this statement. This work has been supported, in part, by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 1 K08 HS 13179-01), Emergency Medical Services for Children (HRSA H34MC04367-01-00), and the California Healthcare Foundation (CHCF #02-2210).

Appendix E1.

| Patient Identification | Age in Months | Sex | Injured | Ambulance Arrival | Day of Week | Night Admission | Physician Training | Medication Given but Not Ordered | Medication Ordered but Not Given | Wrong Drug Given From What Was Ordered | Wrong Dosage* | Too Much | Too Little | Wrong or Inappropriate Drug for Condition* | Wrong Administration Technique | Wrong Route* | Wrong Dosage Form* | Physician-Related Medication Error | Error Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 7 | Male | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Emergency medicine | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 2 | 135 | Male | No | No | Sunday | No | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | D |

| 3 | 102 | Female | No | Yes | Thursday | Yes | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | A |

| 4 | 104 | Male | Yes | No | Tuesday | No | Surgery | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 5 | 38 | Male | No | No | Wednesday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 6 | 16 | Female | No | Yes | Tuesday | No | Surgery | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 7 | 21 | Male | Yes | No | Friday | No | Emergency medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 8 | 3 | Male | No | No | Wednesday | Yes | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 9 | 5 | Male | No | No | Sunday | No | Emergency medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 10 | 16 | Female | No | No | Friday | Yes | Surgery | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 11 | 175 | Male | No | No | Tuesday | No | Emergency medicine | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 12 | 166 | Female | Yes | No | Monday | Yes | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 13 | 150 | Male | No | No | Wednesday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 14 | 200 | Female | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 15 | 82 | Female | No | No | Monday | No | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 16 | 72 | Male | No | No | Friday | No | Internal medicine | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 17 | 194 | Female | Yes | Yes | Tuesday | No | Internal medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 18 | 80 | Male | No | No | Tuesday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 19 | 202 | Female | Yes | Yes | Tuesday | No | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 20 | 177 | Male | Yes | Yes | Wednesday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 21 | 2 | Female | No | No | Wednesday | Yes | Family medicine | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 22 | 45 | Male | No | No | Wednesday | No | Family medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 23 | 165 | Female | Yes | Yes | Friday | Yes | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 24 | 122 | Female | No | No | Tuesday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 25 | 126 | Female | Yes | No | Thursday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 26 | 137 | Female | No | No | Saturday | No | Family medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 27 | 25 | Male | Yes | Yes | Monday | No | Family medicine | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | D |

| 28 | 7 | Male | No | No | Monday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 29 | 22 | Female | No | No | Wednesday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 30 | 5 | Female | No | No | Sunday | No | Family medicine | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 31 | 179 | Female | Yes | Yes | Tuesday | No | Family medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 32 | 36 | Female | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 33 | 120 | Male | Yes | No | Saturday | No | Internal medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | B |

| 34 | 36 | Female | Yes | Yes | Wednesday | Yes | Family medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 35 | 27 | Female | No | Yes | Thursday | No | Family medicine | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 36 | 15 | Female | No | No | Wednesday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 37 | 15 | Female | No | Yes | Thursday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | C |

| 38 | 9 | Female | No | Yes | Friday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 39 | 149 | Male | No | No | Friday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | B |

| 40 | 159 | Female | No | No | Sunday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | D |

| 41 | 14 | Female | No | No | Friday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 42 | 85 | Male | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Family medicine | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | A |

| 43 | 199 | Male | Yes | Yes | Wednesday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 44 | 1 | Male | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Family medicine | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | D |

| 45 | 142 | Male | Yes | No | Saturday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | D |

| 46 | 134 | Female | Yes | No | Wednesday | No | Family medicine | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | A |

| 47 | 188 | Female | Yes | Yes | Wednesday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 48 | 95 | Female | No | No | Monday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 49 | 123 | Female | Yes | Yes | Monday | No | Surgery | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 50 | 78 | Male | No | Yes | Thursday | Yes | Emergency medicine | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | D |

| 51 | 176 | Male | No | Yes | Sunday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 52 | 174 | Male | No | No | Tuesday | Yes | Internal medicine | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 53 | 165 | Female | Yes | Yes | Saturday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 54 | 41 | Female | No | No | Sunday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 55 | 146 | Female | Yes | No | Tuesday | Yes | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 56 | 89 | Female | No | No | Sunday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 57 | 100 | Female | No | No | Thursday | Yes | Internal medicine | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | D |

| 58 | 96 | Female | Yes | No | Saturday | No | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 59 | 5 | Female | No | No | Sunday | No | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 60 | 195 | Female | No | No | Saturday | No | Emergency medicine | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | C |

| 61 | 193 | Male | No | No | Saturday | Yes | Surgery | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | C |

| 62 | 32 | Female | No | Yes | Saturday | Yes | Emergency medicine | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | C |

| 63 | 174 | Female | Yes | Yes | Tuesday | No | Internal medicine | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | C |

| 64 | 179 | Female | No | Yes | Saturday | Yes | Surgery | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 65 | 16 | Female | No | No | Sunday | Yes | Family medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | A |

| 66 | 33 | Female | Yes | No | Friday | No | Internal medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 67 | 24 | Male | No | No | Sunday | No | Family medicine | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | B |

| 68 | 158 | Male | Yes | Yes | Friday | No | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

| 69 | 137 | Female | No | Yes | Monday | No | Emergency medicine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | C |

Physician-related medication error.

Contributor Information

James P. Marcin, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA; Center for Health Service Research in Primary Care, University of California–Davis, CA.

Madan Dharmar, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA; Center for Health Service Research in Primary Care, University of California–Davis, CA.

Meyng Cho, Department of Pharmacy, University of California–Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA.

Lynn L. Seifert, Department of Pharmacy, University of California–Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA.

Jenifer L. Cook, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA.

Stacey L. Cole, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA; Center for Health and Technology, University of California–Davis, CA.

Farid Nasrollahzadeh, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA.

Patrick S. Romano, Department of Pediatrics, University of California–Davis, CA; Department of General Internal Medicine, University of California–Davis, CA; Center for Health Service Research in Primary Care, University of California–Davis, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285:2114–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozer E, Scolnik D, Macpherson A, et al. Variables associated with medication errors in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatrics. 2002;110:737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croskerry P, Shapiro M, Campbell S, et al. Profiles in patient safety: medication errors in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaig LF, Ly N. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2001;326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaushal R, Jaggi T, Walsh K, et al. Pediatric medication errors: what do we know? what gaps remain? Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong IC, Ghaleb MA, Franklin BD, et al. Incidence and nature of dosing errors in paediatric medications: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2004;27:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE, et al. Medication error prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 1987;79:718–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Hospital Association. AHA Guide 2006 Edition. Chicago, IL: Health Forum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Athey J, Dean JM, Ball J, et al. Ability of hospitals to care for pediatric emergency patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17:170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGillivray D, Nijssen-Jordan C, Kramer MS, et al. Critical pediatric equipment availability in Canadian hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.California Rural Health Policy Council. Resources for rural facilities and underserved area designations. Available at: http://www.ruralhealth.oshpd.state.ca.us/faq.htm. Accessed June 6, 2005.

- 12.Office of Rural Health Policy. Geographic eligibility for rural health grant programs. Available at: http://ruralhealth.hrsa.gov/funding/GrantPrograms.htm. Accessed May 8, 2006.

- 13.HRSA Bureau of Health Professions. Shortage designation. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage. Accessed February 7, 2005.

- 14.Holdsworth MT, Fichtl RE, Behta M, et al. Incidence and impact of adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates DW, Boyle DL, Vander Vliet MB, et al. Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE, et al. Pediatric Risk of Admission (PRISA): a measure of severity of illness for assessing the risk of hospitalization from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention. NC MERP index for categorizing medication errors. Available at: http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html. Accessed April 4, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lexi-Comp Inc, American Pharmaceutical Association. Pediatric Dosage Handbook. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, American Pharmaceutical Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesar TS, Briceland LL, Delcoure K, et al. Medication prescribing errors in a teaching hospital. JAMA. 1990;263:2329–2334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamberlain JM, Patel KM, Pollack MM. The Pediatric Risk of Hospital Admission score: a second-generation severity-of-illness score for pediatric emergency patients. Pediatrics. 2005;115:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor BL, Selbst SM, Shah AEC. Prescription writing errors in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selbst SM, Levine S, Mull C, et al. Preventing medical errors in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:702–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez CV, Gillis-Ring J. Strategies for the prevention of medical error in pediatrics. J Pediatr. 2003;143:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selbst SM, Fein JA, Osterhoudt K, et al. Medication errors in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith MA, Atherly AJ, Kane RL, et al. Peer review of the quality of care. Reliability and sources of variability for outcome and process assessments. JAMA. 1997;278:1573–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stucky ER. Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics. 2003;112:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz A, Hales J, Massi FC, et al. Business-office challenges of small and rural hospitals. Healthc Financ Manage. 2004;58:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frush K, Hohenhaus S, Luo XM, et al. Evaluation of a web-based education program on reducing medication dosing error: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozer E, Scolnik D, MacPherson A, et al. Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1299–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]