Abstract

BACKGROUND

Invasive mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults involves adjusting the fraction of inspired oxygen to maintain arterial oxygen saturation. The oxygen-saturation target that will optimize clinical outcomes in this patient population remains unknown.

METHODS

In a pragmatic, cluster-randomized, cluster-crossover trial conducted in the emergency department and medical intensive care unit at an academic center, we assigned adults who were receiving mechanical ventilation to a lower target for oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry (Spo2) (90%; goal range, 88 to 92%), an intermediate target (94%; goal range, 92 to 96%), or a higher target (98%; goal range, 96 to 100%). The primary outcome was the number of days alive and free of mechanical ventilation (ventilator-free days) through day 28. The secondary outcome was death by day 28, with data censored at hospital discharge.

RESULTS

A total of 2541 patients were included in the primary analysis. The median number of ventilator-free days was 20 (interquartile range, 0 to 25) in the lower-target group, 21 (interquartile range, 0 to 25) in the intermediate-target group, and 21 (interquartile range, 0 to 26) in the higher-target group (P = 0.81). In-hospital death by day 28 occurred in 281 of the 808 patients (34.8%) in the lower-target group, 292 of the 859 patients (34.0%) in the intermediate-target group, and 290 of the 874 patients (33.2%) in the higher-target group. The incidences of cardiac arrest, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumothorax were similar in the three groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Among critically ill adults receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, the number of ventilator-free days did not differ among groups in which a lower, intermediate, or higher Spo2 target was used. (Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and others; PILOT ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03537937.)

Each year, 2 to 3 million critically ill adults in the United States receive invasive mechanical ventilation.1–3 In-hospital mortality among critically ill adults receiving mechanical ventilation remains approximately 35%.4–7

Mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults universally involves adjusting the fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) to maintain arterial oxygen saturation — as assessed by pulse oximetry (Spo2) or blood gas analysis (Sao2) — or arterial oxygen tension (i.e., partial pressure of arterial oxygen [Pao2]). The oxygenation target that optimizes clinical outcomes for critically ill adults remains unknown. Spo2 targets that are on the higher end of the range used in clinical care (96 to 100%) provide a margin of safety against hypoxemia but may increase exposure to excess Fio2, hyperoxemia, and tissue hyperoxia, causing oxidative damage,8–10 inflammation,11,12 and increased alveolar–capillary permeability.13 Spo2 targets on the lower end of the range used in clinical care (88 to 92%) minimize these risks14–16 but may increase exposure to hypoxemia and tissue hypoxia.17,18 An intermediate Spo2 target (92 to 96%) may avoid the risks of both hyperoxia and hypoxia or, conversely, may expose patients intermittently to both sets of risks.19,20

Randomized trials examining oxygenation targets among critically ill adults have had differing results, including no difference in outcomes between targets,21–23 better outcomes with a lower target,24,25 and better outcomes with a higher target.26 Observational studies have reported a U-shaped association between oxygenation and clinical outcomes,18,27 with intermediate Spo2 values of approximately 94 to 96% being associated with better outcomes than either higher or lower values. However, trials in which an intermediate target is compared with either higher or lower targets are lacking. Variation in current clinical practice28–30 and differences in the targets recommended in different international guidelines31–35 indicate the need for further clinical trials to determine the effect of Spo2 target on patient outcomes.14,36 To determine the effects of lower, intermediate, and higher Spo2 targets on clinical outcomes among critically ill adults receiving mechanical ventilation, we conducted the Pragmatic Investigation of Optimal Oxygen Targets (PILOT) trial.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

We conducted a pragmatic, unblinded, cluster-randomized, cluster-crossover trial to compare the use of a lower Spo2 target (90%; goal range, 88 to 92%), an intermediate Spo2 target (94%; goal range, 92 to 96%), and a higher Spo2 target (98%; goal range, 96 to 100%) during invasive mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults. The trial was initiated by the investigators and approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center with waiver of informed consent (see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). It was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov before initiation and overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. Enrollment began on July 1, 2018; was paused from April 1, 2020, until May 31, 2020, because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic; and concluded on August 31, 2021 (36 months of enrollment). The protocol (available at NEJM.org) and statistical analysis plan were published before enrollment concluded.37

The authors designed the trial, collected the data, and performed the analyses. The institutions that provided funding had no role in the design or conduct of the trial, collection of the data, or analysis, interpretation, and presentation of the results. The first author drafted the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript, vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol, and approved the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

TRIAL SITES AND PATIENT POPULATION

The trial was conducted in the emergency department (ED) and medical intensive care unit (ICU) at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville. All eligible adults (≥18 years of age) located in the medical ICU or located in the ED with planned admission to the medical ICU were enrolled at the time of the first receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or incarcerated.

RANDOMIZATION AND TREATMENT ASSIGNMENTS

All eligible patients in the ED and ICU were assigned together as a single cluster to an Spo2 target (cluster-level randomization). Every 2 months, the ED and ICU switched together from the use of a lower, intermediate, or higher Spo2 target in a randomly generated sequence (cluster-level cross-over). During the 36 months of the trial, the single cluster (ED and ICU) had 18 trial periods that were 2 months in duration (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). The order of trial-group assignments for each 2-month period was generated by computerized randomization with the use of permuted blocks of three to minimize the effect of seasonal variation and temporal changes. The final 7 days of each 2-month period were considered to be an analytic washout period during which the ED and ICU continued to use the assigned Spo2 target but data from new patients were not included in the primary analysis. For patients who continued to receive mechanical ventilation in a trial location after the end of the washout period, the Spo2 target was selected by treating clinicians. Patients and clinicians were aware of the group assignments.

INTERVENTION

The Spo2 targets in the lower-, intermediate-, and higher-target groups were 90% (goal range, 88 to 92%), 94% (goal range, 92 to 96%), and 98% (goal range, 96 to 100%), respectively. The trial protocol instructed respiratory therapists to adjust the Fio2 to achieve the target Spo2 beginning within 15 minutes after initiation of mechanical ventilation and ending at discontinuation of mechanical ventilation, transfer out of a participating unit, or the end of the 2-month study period, whichever occurred first. The trial protocol did not determine the Spo2 target when the patient was not physically located in a study unit (e.g., during transport), when Fio2 was being administered for purposes other than achieving a target Spo2 (e.g., oxygen administration during a procedure), or during a spontaneous breathing trial.38 Spo2 was assessed by means of continuous pulse oximetry, with an alarm set for Spo2 values lower or higher than the goal range. When pulse oximetry monitoring was unavailable or inaccurate, oxygen therapy was adjusted with the use of Pao2 targets of 60 mm Hg in the lower-target group, 70 mm Hg in the intermediate-target group, and 110 mm Hg in the higher-target group (Fig. S2). If, at any time, a treating clinician, patient, or family member determined that an oxygenation target other than that assigned by the trial might be best for the treatment of the patient, the oxygenation target for that patient was modified and the reason for modifying the target was recorded. The trial protocol directed only the adjustment of Fio2 to the assigned Spo2 target. Other aspects of mechanical ventilation, including selection of tidal volume and positive end-expiratory pressure, frequency of arterial blood gas measurement, administration of analgesia and sedation, and timing of extubation, were determined by institutional protocols and treating clinicians (see the Supplemental Methods section).

DATA COLLECTION

Trial personnel collected data on baseline characteristics, treatment received during the trial, and in-hospital outcomes from the electronic health record with the use of a standardized case-report form. Data on Spo2, Fio2, and ventilator settings were automatically extracted from the bedside monitor at a frequency of every 1 minute with the use of a previously validated approach.39 Data on safety outcomes were obtained from the electronic health record with the use of a standardized case-report form by trial personnel who were unaware of the group assignments.

OUTCOME MEASURES

The primary outcome was the number of days alive and free of mechanical ventilation (ventilator-free days) through day 28, defined as the number of calendar days alive and free of invasive mechanical ventilation beginning the day after the final receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation through day 28.40,41 Outcome ascertainment ceased at the time of hospital discharge or day 28, whichever occurred first. Patients were assigned a value of 0 ventilator-free days if they died before day 28, continued to receive mechanical ventilation beyond day 28, or continued to receive mechanical ventilation at the time of hospital discharge. The sole prespecified secondary outcome was death from any cause by day 28, with data censored at hospital discharge. Exploratory outcomes are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Details of the sample-size calculation have been reported previously.37 Using data from a previous trial conducted in the same clinical context,42 we estimated that, during the 36 months of the trial, 2250 patients would be enrolled and included in the primary analysis, the median number of ventilator-free days would be 22 (interquartile range, 0 to 25), and the intracluster intraperiod correlation would be 0.01. We calculated that enrollment of 2250 patients would provide 92% power at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 to detect an absolute difference of 2 ventilator-free days between any two of the three trial groups. A difference of this magnitude has been considered to be clinically meaningful in the design of previous critical care trials.22,43,44

The primary analysis population included all enrolled patients except those admitted during one of the 7-day washout periods and those with a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of Covid-19. Patients with Covid-19 were not included in the primary analysis population because the majority of the trial occurred before the Covid-19 pandemic and patients with Covid-19 were primarily cared for in a separate ICU that did not participate in the trial.

In the primary analysis, the number of ventilator-free days was compared among patients assigned to the lower-, intermediate-, and higher-target groups with the use of a proportional-odds model with independent covariates of group assignment and time.45,46 To account for seasonality and secular trends, we included the time from the start of the trial (in days) as a continuous variable with values ranging from 1 (first day of enrollment) to 1097 (final day of enrollment); restricted cubic splines with five knots were used to allow for nonlinearity. In addition to assessing for an overall group effect within the model, we estimated the differences between each pair of Spo2 targets by extracting 95% confidence intervals from the model. For the primary outcome, the intraclass correlation calculated with the use of an analysis-of-variance method was 0.007.

In sensitivity analyses, we used alternative definitions of the trial population and alternative statistical methods for analyzing the primary outcome, including an analysis involving patients admitted during washout periods and patients with Covid-19 and an analysis with adjustment for age, sex, race and ethnic group, source of ICU admission, vasopressor receipt, acute diagnoses at enrollment, and severity of illness as assessed by the nonrespiratory Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (Table S1).47,48 Effect modification was assessed in a proportional-odds model by including an interaction term between trial-group assignment and a prespecified baseline variable. Prespecified potential effect modifiers included age, race and ethnic group, receipt of supplemental oxygen at the place of residence, preenrollment cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, sepsis as defined according to Sepsis-3 criteria,49 and acute respiratory distress syndrome as defined according to Berlin criteria (see the Supplementary Appendix).50

The data and safety monitoring board reviewed a single planned interim analysis of data from patients enrolled during the first 18 months of the trial, in which the primary outcome was compared among the groups with the use of a Haybittle–Peto stopping boundary for efficacy of a P value of less than 0.001. For the final analysis of the primary outcome, a two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes are reported with the use of a complete-case analysis with point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. The widths of the confidence intervals were not adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive differences in treatment effects among the groups. All analyses were performed with R software, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

TRIAL POPULATION

Of the 3024 patients who received invasive mechanical ventilation and underwent screening, 37 (1.2%) met exclusion criteria and 2987 (98.8%) were enrolled in the trial (Fig. S3). Of these 2987 patients, 446 (14.9%) were excluded from the primary analysis because they had been enrolled during an analytic washout period or had a diagnosis of Covid-19 and 2541 (85.1%) were included in the primary analysis. Among the 2541 patients in the primary analysis, 808 (31.8%) were assigned to the lower-target group, 859 (33.8%) to the intermediate-target group, and 874 (34.4%) to the higher-target group. The trial groups had similar characteristics at baseline (Table 1 and Tables S2 through S7).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Lower Spo2 Target (N = 808) | Intermediate Spo2 Target (N = 859) | Higher Spo2 Target (N = 874) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 57 (44–67) | 59 (47–68) | 59 (45–68) |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 361 (44.7) | 385 (44.8) | 409 (46.8) |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)† | |||

| White | 649 (80.3) | 666 (77.5) | 695 (79.5) |

| Black | 121 (15.0) | 140 (16.3) | 136 (15.6) |

| Other | 38 (4.7) | 53 (6.2) | 43 (4.9) |

| Median time from initiation of mechanical ventilation to enrollment (IQR) — hr‡ | 0.0 (0.0–4.9) | 0.0 (0.0–4.5) | 0.0 (0.0–5.5) |

| Location at enrollment — no. (%) | |||

| Emergency department | 280 (34.7) | 313 (36.4) | 282 (32.3) |

| Intensive care unit | 528 (65.3) | 546 (63.6) | 592 (67.7) |

| Coexisting conditions — no. (%) | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 148 (18.3) | 175 (20.4) | 169 (19.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 145 (17.9) | 152 (17.7) | 178 (20.4) |

| End-stage kidney disease, receiving RRT | 52 (6.4) | 46 (5.4) | 39 (4.5) |

| Acute illnesses§ | |||

| Cardiac arrest — no. (%) | 125 (15.5) | 100 (11.6) | 109 (12.5) |

| Acute myocardial infarction — no. (%) | 136 (16.8) | 138 (16.1) | 145 (16.6) |

| Sepsis or septic shock — no. (%) | 275 (34.0) | 247 (28.8) | 283 (32.4) |

| Stage ≥II acute kidney injury — no./total no. (%) | 231/756 (30.6) | 248/813 (30.5) | 243/835 (29.1) |

| Receipt of vasopressors — no. (%) | 160 (19.8) | 171 (19.9) | 153 (17.5) |

| Median nonrespiratory SOFA score (IQR)¶ | 5 (4–8) | 5 (4–8) | 5 (3–8) |

A total of 2541 patients were enrolled during 18 periods of 2 months each: 808 during 6 periods assigned to the lower Spo2 target (90%), 859 during 6 periods assigned to the intermediate Spo2 target (94%), and 874 during 6 periods assigned to the higher Spo2 target (98%). IQR denotes interquartile range, and RRT renal-replacement therapy.

Information on race and ethnic group was obtained from the electronic health record. “Other” includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and unspecified.

Calculation of this measure included 2468 patients (784 in the lower-target group, 832 in the intermediate-target group, and 852 in the higher-target group) who had not been receiving long-term mechanical ventilation at their place of residence before enrollment.

Sepsis or septic shock was defined according to the Sepsis-3 criteria.49 Acute kidney injury of stage II or greater was defined according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes creatinine criteria. The category of acute kidney injury includes 2404 patients who had not received RRT before enrollment.

The nonrespiratory Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score47 is composed of scores from five organ systems (excluding the respiratory system), graded from 0 to 4 according to the degree of dysfunction or failure. Scores range from 0 (no evidence of nonrespiratory organ dysfunction or failure) to 20 (evidence of severe nonrespiratory organ dysfunction or failure) (Table S1).

OXYGENATION AND ICU INTERVENTIONS

A total of 7,818,831 Spo2 values were measured between enrollment and cessation of invasive mechanical ventilation among the 2541 patients; the median number of Spo2 measurements per patient was 1517 (interquartile range, 562 to 3806), and the median interval between Spo2 measurements was 1 minute (interquartile range, 1 to 1). Spo2 and Pao2 values were lower in the lower-target group than in the intermediate- or higher-target groups (Fig. 1, Figs. S4 and S5, and Tables S8, S9, and S10). A single mean Spo2 value was calculated for each patient in the lower-, intermediate-, and higher-target groups; in an analysis of these mean values, the medians were 94%, 95%, and 97%, respectively. The percentage of all Spo2 measurements with a value of 99% or 100% was 12.3% in the lower-target group, 14.7% in the intermediate-target group, and 32.7% in the higher-target group; the percentage of measurements with a value of less than 85% was 0.8%, 0.6%, and 0.9%, respectively. The incidence and duration of hypoxemia characterized by Spo2 values of less than 85%, less than 80%, or less than 70% were similar in the three groups (Table S11). Instances in which the SpO2 target was modified are described in Table S12.

Figure 1.

Spo2 and Fio2 Values in Each Group. Shown are the mean values (colored lines) and 95% confidence intervals (gray shading) for the hourly mean oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry (Spo2) (Panel A) and the fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) (Panel B) from enrollment to day 7; data were censored at the time that invasive mechanical ventilation was discontinued. Spo2 and Fio2 values were obtained approximately every 1 minute, and hourly means were calculated by averaging all measurements obtained during the hour. The number of patients who were alive and receiving invasive mechanical ventilation in each group on each day is shown.

A total of 7,641,557 Fio2 values were measured (Fig. 1 and Fig. S6). In an analysis of the mean Fio2 value in each patient in the lower-, intermediate-, and higher-target groups, the medians were 0.31, 0.37, and 0.45, respectively (Table S9). The percentages of Fio2 values that were 0.21 (i.e., equivalent to ambient air) in the lower-, intermediate-, and higher-target groups were 33.8%, 21.9%, and 4.0%, respectively. The percentages of Fio2 values that were 0.40 or higher were 32.6%, 44.9%, and 69.1%, respectively (Table S8).

Information on modes of mechanical ventilation, tidal volume, coma, delirium, sedative receipt, organ function, laboratory values, and positive end-expiratory pressure is provided in Tables S13 through S17. The median positive end-expiratory pressure was 5 cm of water in each trial group on days 1 through 7.

PRIMARY OUTCOME

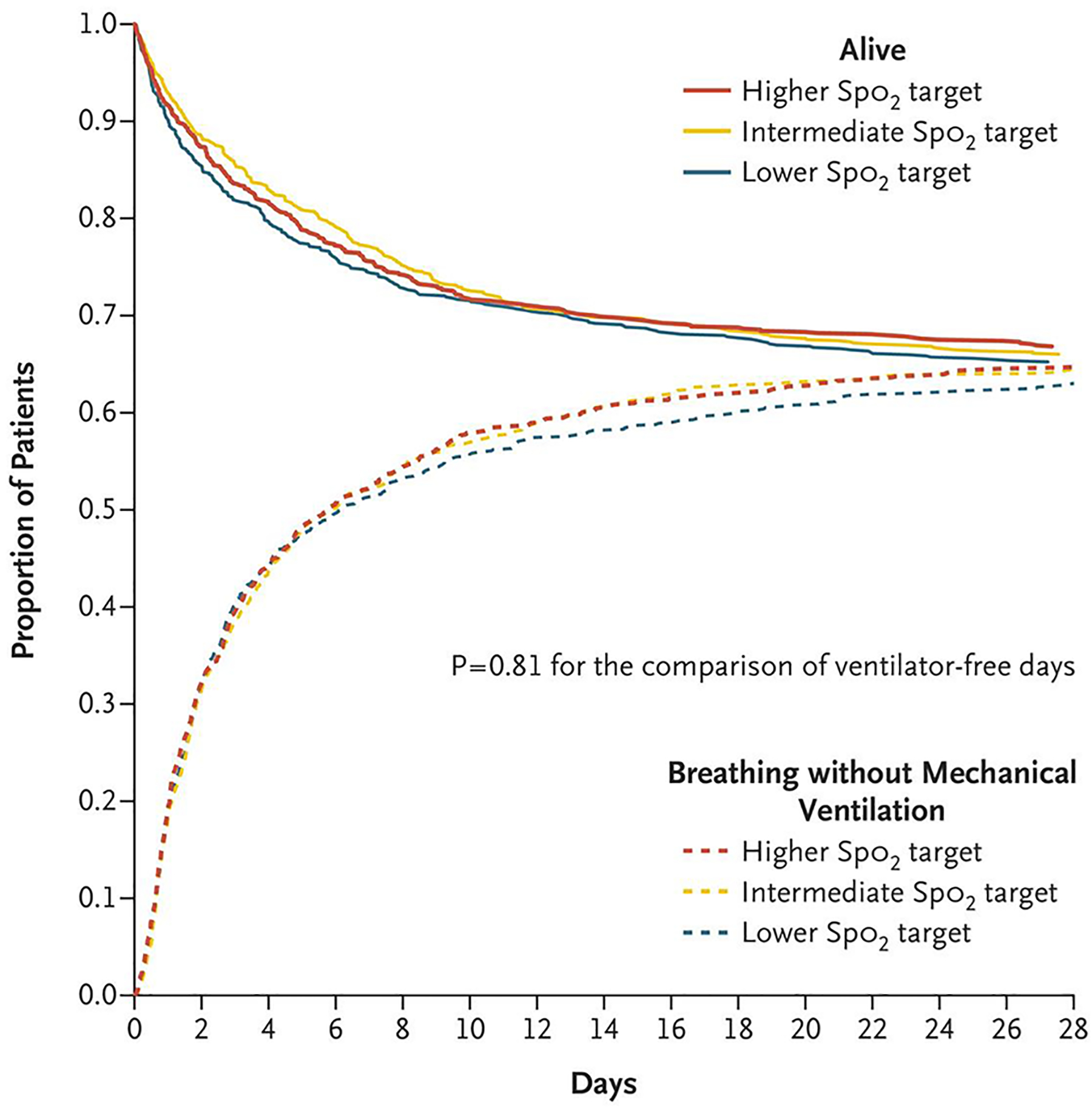

The number of ventilator-free days through day 28 did not differ significantly among the trial groups, with a median of 20 days (interquartile range, 0 to 25) in the lower-target group, 21 days (interquartile range, 0 to 25) in the intermediate-target group, and 21 days (interquartile range, 0 to 26) in the higher-target group (P = 0.81) (Fig. 2, Tables S18 and S19, and Fig. S7). Results were similar in analyses that included adjustment for baseline covariates, analyses that included patients who had been enrolled during analytic washout periods and patients with Covid-19, and analyses in which alternative approaches to modeling ventilator-free days were used (Table S20 and Fig. S8). The results for the primary outcome did not appear to differ among the trial groups in any of the prespecified subgroups (Fig. 3, Figs. S9 and S10, and Table S21).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Patients Alive and Not Receiving Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. The proportion of patients who were alive and breathing without invasive mechanical ventilation during the 28 days after enrollment in each Spo2-target group is shown. In a proportional-odds model, the number of days that patients were alive and free of invasive mechanical ventilation through day 28 did not differ significantly among the groups (P = 0.81).

Figure 3.

Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome. The median number of ventilator-free days is compared among the three Spo2-target groups in subgroups of patients defined according to prespecified baseline characteristics. Odds ratios greater than 1.0 indicate a greater number of ventilator-free days (i.e., a better outcome). IQR denotes interquartile range.

SECONDARY AND EXPLORATORY OUTCOMES

At 28 days, 281 patients (34.8%) in the lower-target group, 292 patients (34.0%) in the intermediate-target group, and 290 patients (33.2%) in the higher-target group had died before hospital discharge (Table 2 and Fig. S11). The prespecified exploratory clinical outcomes were similar in the three groups (Table 2 and Tables S22 and S23).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes.*

| Outcome† | Lower Spo2 Target (N = 808) | Intermediate Spo2 Target (N = 859) | Higher Spo2 Target (N=874) | Odds Ratio (95% CI)‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower vs. Intermediate | Intermediate vs. Higher | Lower vs. Higher | ||||

| Primary outcome: ventilator-free days | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 20 (0–25) | 21 (0–25) | 21 (0–26) | 0.95 (0.79–1.13) | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 0.95 (0.78–1.14) |

| Mean | 14±12 | 14±12 | 14±12 | |||

| Secondary outcome: in-hospital death before 28 days | ||||||

| No. of patients (%) | 281 (34.8) | 292 (34.0) | 290 (33.2) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) | 1.04 (0.84–1.28) | 1.16 (0.93–1.45) |

| Exploratory outcomes | ||||||

| In-ICU death before 28 days — no. (%) | 244 (30.2) | 259 (30.2) | 249 (28.5) | 1.09 (0.88–1.35) | 1.08 (0.87–1.35) | 1.18 (0.94–1.49) |

| Hospital-free days | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (0–20) | 11 (0–21) | 10 (0–20) | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 0.98 (0.81–1.19) |

| Mean | 10±10 | 11±10 | 10±10 | |||

| ICU-free days | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 20 (0–24) | 19 (0–24) | 20 (0–24) | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) |

| Mean | 14±11 | 14±11 | 14±11 | |||

| Vasopressor-free days | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 25 (0–28) | 25 (0–28) | 25 (0–28) | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 0.97 (0.81–1.16) | 0.87 (0.72–1.05) |

| Mean | 17±13 | 17±13 | 17±13 | |||

| RRT-free days | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 28 (0–28) | 28 (0–28) | 28 (0–28) | 0.93 (0.77–1.14) | 0.94 (0.77–1.14) | 0.88 (0.71–1.08) |

| Mean | 17±13 | 17±13 | 18±13 | |||

| Stage ≥II acute kidney injury — no./total no. (%)§ | 230/756 (30.4) | 253/813 (31.1) | 251/835 (30.1) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) |

| Receipt of RRT — no./total no. (%)§ | 112/756 (14.8) | 118/813 (14.5) | 97/835 (11.6) | 0.99 (0.74–1.33) | 1.29 (0.96–1.75) | 1.28 (0.93–1.77) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. Data on outcomes were available for all 2541 patients enrolled during the 18 periods of 2 months each; 808 during 6 periods assigned to the lower Spo2 target, 859 during 6 periods assigned to the intermediate Spo2 target, and 874 during 6 periods assigned to the higher Spo2 target.

Ventilator-free, hospital-free, intensive care unit (ICU)–free, vasopressor-free, and RRT-free days refer to the number of days on which a patient was alive and free from the specified therapy in the first 28 days after enrollment.

Odds ratios of greater than 1.0 indicate a better outcome (e.g., more days alive and free from the supportive therapy) with the comparator than with the referent. The primary outcome of ventilator-free days did not differ significantly among the three groups (P = 0.81). For in-hospital death before 28 days and in-ICU death before 28 days, odds ratios lower than 1.0 indicate a better outcome (e.g., lower odds of death).

Acute kidney injury of stage II or greater is defined according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes creatinine criteria. Data on acute kidney injury and receipt of RRT are shown for 2404 patients who had not received RRT before enrollment.

SAFETY OUTCOMES

The incidences of cardiac arrest, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum were similar in the three groups (Table S24). One adverse event (bradycardia) was reported in a patient in the lower-target group (Table S25).

DISCUSSION

Among the critically ill adults receiving mechanical ventilation in this clinical trial, the number of ventilator-free days and the incidence of death did not differ among groups of patients in which a lower, intermediate, or higher Spo2 target was used. We found no apparent differences in subgroup analyses of the primary outcome or in analyses of any secondary or exploratory outcome. The clinical implication of these findings is that, among patients in the ICU receiving mechanical ventilation, limiting exposure to supplemental oxygen by targeting Spo2 values as low as 90% does not prevent death or expedite liberation from mechanical ventilation.

Our findings are consistent with those of three recent randomized trials in which no differences between lower and higher oxygenation targets were observed.21–23 Our results add to the understanding of the effects of oxygenation targets on clinical outcomes in two ways. First, observational research has proposed a U-shaped association between oxygenation and clinical outcomes,27,51 with better outcomes at intermediate oxygen levels than at either lower or higher oxygen levels. Whereas previous trials primarily compared lower and higher oxygenation targets, our trial directly compared lower and higher targets with an intermediate target; we found no evidence to support a U-shaped relationship between oxygenation and outcomes. Second, previous trials obtained Spo2 and Fio2 values every 6 to 12 hours, whereas in our trial we obtained Spo2 and Fio2 values approximately every 1 minute, which allowed for more granular assessments of adherence to oxygen targets, supplemental oxygen exposure, and incidence and duration of hypoxemia.

The results of our trial differ from those of a previous trial24 in which mortality among 434 patients in a single ICU who were treated with an Spo2 target of 94 to 98% was lower than mortality among patients treated with a target of 97 to 100%. Our results also differ from those of a previous trial26 involving 201 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome who were receiving mechanical ventilation, in which mortality was found to be higher among the patients treated with a Pao2 target of 55 to 70 mm Hg than among those treated with a target of 90 to 105 mm Hg. In contrast to these initial findings, the results of our trial and three other recent trials21–23 suggest that, within the range of Spo2 values from 90 to 98%, the choice of oxygenation target does not affect clinical outcomes for a broad population of critically ill adults.

Our trial has several additional strengths. The sample of 2541 patients, which was a greater number of patients receiving mechanical ventilation than in previous trials,21–24,26 permitted more precise estimates of treatment effect. Key subgroups were represented, including patients with sepsis25,52 and patients with cardiac arrest53; findings in these subgroups, paired with results from previous trials,26,53,54 may help to identify areas for future investigation. Generalizability was enhanced by the pragmatic trial design and the exclusion of only 1% of patients, as compared with 30%,21 48%,26 54%,24 70%,22 and 94%23 of patients in previous trials. Enrollment occurred immediately on first receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation, including mechanical ventilation in the ED before ICU admission, thereby capturing the period of highest risk for hyperoxemia and hypoxemia and minimizing contamination among the groups with respect to oxygen exposure before enrollment. Our finding of no difference among the targets was consistent across all outcomes, subgroups, and numerous sensitivity analyses.

Our trial also has several limitations. Although conducting the trial at a single center increased internal validity by facilitating fidelity to the intervention and the collection of granular data on separation among the groups, it limits generalizability. Starting the trial intervention immediately on first receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation precluded baseline assessments of severity of lung injury, such as the ratio of Pao2 to Fio2. As in previous trials in this field,21,23,53 patients and clinicians were aware of the oxygenation target assignments. The primary and secondary outcomes of the trial were assessed at 28 days; collection of data on outcomes at 12 months is ongoing. The trial protocol did not control additional interventions such as positive end-expiratory pressure, choice of sedation, and approach to ventilator weaning. However, these interventions were standardized according to institutional protocols and showed no apparent differences among the groups. Spo2 and Pao2 each have advantages and disadvantages as targets during critical illness, including the fact that the accuracy of pulse oximetry may be affected by skin pigmentation.55 The results of our trial in which Spo2 targets were used were similar to those of previous trials in which Pao2 targets were used.21,23

Among critically ill adults receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, the number of ventilator-free days did not differ among groups in which a lower Spo2 target (90%), an intermediate Spo2 target (94%), or a higher Spo2 target (98%) was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL143053, to Dr. Semler). The Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool used for data collection was developed and is maintained with a grant (UL1TR000445, to the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The following authors’ work was also supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health: Dr. Casey (K23HL153584); Dr. Qian (T32HL087738); Drs. Lind-sell, Bernard, and Rice (UL1TR002243, to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center); Dr. Freundlich (1KL2TR002245 and 1K23HL148640); and Dr. Han (R21AG06312).

Footnotes

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Hartman ME, Milbrandt EB, Kahn JM. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1947–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Rowan KM. Comparison of medical admissions to intensive care units in the United States and United Kingdom. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 1666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adhikari NKJ, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010; 376: 1339–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Muriel A, et al. Evolution of mortality over time in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempker JA, Abril MK, Chen Y, Kramer MR, Waller LA, Martin GS. The epidemiology of respiratory failure in the United States 2002–2017: a serial cross-sectional study. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2(6): e0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shehabi Y, Howe BD, Bellomo R, et al. Early sedation with dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2506–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 319: 2179–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fridovich I Oxygen toxicity: a radical explanation. J Exp Biol 1998; 201: 1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heffner JE, Repine JE. Pulmonary strategies of antioxidant defense. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 140: 531–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman BA, Crapo JD. Hyperoxia increases oxygen radical production in rat lungs and lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem 1981; 256: 10986–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waxman AB, Einarsson O, Seres T, et al. Targeted lung expression of interleukin-11 enhances murine tolerance of 100% oxygen and diminishes hyperoxia-induced DNA fragmentation. J Clin Invest 1998; 101: 1970–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith DE, Garcia JG, James HL, Callahan KS, Iriana S, Holiday D. Hyperoxic exposure in humans: effects of 50 percent oxygen on alveolar macrophage leukotriene B4 synthesis. Chest 1992; 101: 392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis WB, Rennard SI, Bitterman PB, Crystal RG. Pulmonary oxygen toxicity: early reversible changes in human alveolar structures induced by hyperoxia. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 878–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal NR, Brower RG. Targeting normoxemia in acute respiratory distress syndrome may cause worse short-term outcomes because of oxygen toxicity. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 1449–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meade MO, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, et al. Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 299: 637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastwood G, Bellomo R, Bailey M, et al. Arterial oxygen tension and mortality in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Jonge E, Peelen L, Keijzers PJ, et al. Association between administered oxygen, arterial partial oxygen pressure and mortality in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care 2008; 12: R156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen BS, Ilbawi MN. Hypoxia, reoxygenation and the role of systemic leukodepletion in pediatric heart surgery. Perfusion 2001; 16: Suppl: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen BS. The reoxygenation injury: is it clinically important? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 124: 16–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schjørring OL, Klitgaard TL, Perner A, et al. Lower or higher oxygenation targets for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The ICU-ROX Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Conservative oxygen therapy during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 989–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelissen H, de Grooth H-J, Smulders Y, et al. Effect of low-normal vs high-normal oxygenation targets on organ dysfunction in critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 326: 940–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit: the Oxygen-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 316: 1583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asfar P, Schortgen F, Boisramé-Helms J, et al. Hyperoxia and hypertonic saline in patients with septic shock (HYPERS2S): a two-by-two factorial, multicentre, randomised, clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrot L, Asfar P, Mauny F, et al. Liberal or conservative oxygen therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Boom W, Hoy M, Sankaran J, et al. The search for optimal oxygen saturation targets in critically ill patients: observational data from large ICU databases. Chest 2020; 157: 566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panwar R, Capellier G, Schmutz N, et al. Current oxygenation practice in ventilated patients — an observational cohort study. Anaesth Intensive Care 2013; 41: 505–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki S, Eastwood GM, Peck L, Glassford NJ, Bellomo R. Current oxygen management in mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective observational cohort study. J Crit Care 2013; 28: 647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helmerhorst HJ, Schultz MJ, van der Voort PH, et al. Self-reported attitudes versus actual practice of oxygen therapy by ICU physicians and nurses. Ann Intensive Care 2014; 4: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Earis J, Mak V. BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Thorax 2017; 72: Suppl 1: ii1–ii90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siemieniuk RAC, Chu DK, Kim LH-Y, et al. Oxygen therapy for acutely ill medical patients: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2018; 363: k4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307: 795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, deBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA 2011; 306: 1574–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beasley R, Chien J, Douglas J, et al. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen guidelines for acute oxygen use in adults: ‘swimming between the flags’. Respirology 2015; 20: 1182–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Self WH, Semler MW, Rice TW. Oxygen targets for patients who are critically ill: emerging data and state of equipoise. Chest 2020; 157: 487–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semler MW, Casey JD, Lloyd BD, et al. Protocol and statistical analysis plan for the Pragmatic Investigation of optimaL Oxygen Targets (PILOT) clinical trial. BMJ Open 2021; 11(10): e052013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buell KG, Casey JD, Wang L, et al. Big data for clinical trials: automated collection of SpO2 for a trial of oxygen targets during mechanical ventilation. J Med Syst 2020; 44: 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2002; 30: 1772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harhay MO, Wagner J, Ratcliffe SJ, et al. Outcomes and statistical power in adult critical care randomized trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 1469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 829–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2564–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McAuley DF, Laffey JG, O’Kane CM, et al. Simvastatin in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner RM, White IR, Croudace T. Analysis of cluster randomized cross-over trial data: a comparison of methods. Stat Med 2007; 26: 274–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parienti J-J, Kuss O Cluster-crossover design: a method for limiting clusters level effect in community-intervention studies. Contemp Clin Trials 2007; 28: 316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med 1996; 22: 707–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huerta LE, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, Freundlich RE, Rice TW, Semler MW. Validation of a sequential organ failure assessment score using electronic health record data. J Med Syst 2018; 42: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307: 2526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Helmerhorst HJF, Roos-Blom M-J, van Westerloo DJ, Abu-Hanna A, de Keizer NF, de Jonge E. Associations of arterial carbon dioxide and arterial oxygen concentrations with hospital mortality after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care 2015; 19: 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young P, Mackle D, Bellomo R, et al. Conservative oxygen therapy for mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis: a post hoc analysis of data from the intensive care unit randomized trial comparing two approaches to oxygen therapy (ICU-ROX). Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young P, Mackle D, Bellomo R, et al. Conservative oxygen therapy for mechanically ventilated adults with suspected hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 2411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt H, Kjaergaard J, Hassager C, et al. Oxygen targets in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 1467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2477–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.