Abstract

Background

Cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) appears to be an appropriate imaging technique for device surveillance after left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO). However, the available experience is limited.

Aims

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence, mechanisms and clinical impact of left atrial appendage (LAA) patency and device-related thrombosis (DRT) following LAAO utilising a novel CCTA-based classification.

Methods

Consecutively enrolled patients who underwent LAAO with an AMPLATZER device were followed up with CCTA. Mechanisms and frequency of residual patency were evaluated and correlated with clinical events. Atrial-side device thrombus, device positioning and presence of signs of device stability were also analysed.

Results

A total of 137 patients were included. LAA patency was observed in 56.9% (n=78). Mechanisms and frequency of patency were: malapposition of proximal segment of the device lobe (55.1%), peri-device leak (PDL, 34.6%) and fabric permeability (5.8%). Lobe-LAA axis misalignment was the only independent predictor of device patency after LAAO (HR 38.3, 95% CI: 13.6-107.0; p<0.001). After a median follow-up of 638 days, patency was not associated with an increased risk of death (all-cause or cardiovascular death) or cerebral/peripheral embolism regardless of its mechanism. Any degree of hypo-attenuated thickening (HAT) was found in 16.8% (n=23) of patients, of whom 16 (11.7%) had low-grade HAT and 7 (5.1%) had high-grade HAT or definite DRT. Complete sealing was associated with increased rates of low-grade HAT.

Conclusions

LAA patency on CCTA follow-up is a frequent phenomenon due to malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe, PDL or fabric permeability. Patency was not associated with adverse outcomes. Low-grade HAT may be related to a benign, uneventful, endothelialisation process favoured by complete LAAO.

Introduction

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) is an accepted strategy for cardioembolic event prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who are deemed unsuitable for long-term anticoagulation therapy1.

Presently, the two percutaneous LAAO devices most widely used are the WATCHMAN™️ device (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) and the AMPLATZER™️ Amulet™️ (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Both devices have proven their efficacy and safety in clinical trials and large registries2,3,4,5,6. An investigational device exemption trial comparing the efficacy and safety of the two devices is currently ongoing (Amulet IDE, NCT02879448).

To ensure the long-term efficacy of LAAO, device surveillance is recommended 6 to 12 weeks post-procedure with either transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) or cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA), primarily to assess for peri-device leak (PDL)/patency or device-related thrombosis (DRT)7. While most studies have employed TOE, CCTA has emerged as a promising imaging technique for the follow up, due to its non-invasive acquisition and high 3D resolution. Several studies have demonstrated its greater sensitivity for detecting left atrial appendage (LAA) patency. However, a standardised CCTA-based classification of the severity, location and mechanisms of patency is lacking8,9,10,11,12,13.

DRT has raised concern in LAAO procedures, due to its high incidence (2% to 18%) and its potentially negative impact on the risk of stroke and systemic embolism14,15,16,17,18. CCTA might be a useful tool for an early diagnosis of DRT since enhancement defects (ED) suggestive of high-grade hypo-attenuated thickening (HAT) are quite common. Although the poor prognosis of definite DRT/high-grade HAT seems proven, the prognosis of low-grade HAT remains uncertain17.

The objectives of this study focused on determining the prevalence, mechanisms and clinical impact of LAA patency and HAT following LAAO utilising a novel computed tomography (CT)-based classification.

Methods

PATIENT POPULATION

From March 2013 to December 2019, consecutive patients who underwent LAAO with an AMPLATZER device and were followed up with CCTA were included. According to the institution’s protocol, patients whose LAAO indication was a prior gastrointestinal bleeding received anticoagulation drugs (mainly subcutaneous heparin) after LAAO for three months, and patients with a history of intracranial bleeding were discharged with indefinite antiplatelet monotherapy, usually clopidogrel. The choice and duration of antithrombotic treatment, after LAAO in patients with other indications, were individualised depending on the patient’s history and operator preference19. The study adhered to the international standards of scientific studies and the Declaration of Helsinki principles, and was approved by the ethics committee of our institution.

PROCEDURE

Preprocedural work-up with either TOE or CCTA was performed in all patients. Procedural guidance was performed utilising TOE or intracardiac echocardiography (ICE). Most TOE cases required general anaesthesia, whereas ICE-guided procedures were conducted under local anaesthesia and conscious sedation.

Two LAAO devices were implanted during the study period, the AMPLATZER™️ Cardiac Plug (ACP) and, since 2014, the AMPLATZER Amulet (both Abbott Vascular). A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed the following day in all patients before discharge.

DATA COLLECTION AND FOLLOW-UP

Baseline characteristics, indication for LAAO, procedural details, periprocedural adverse events, clinical outcomes and follow-up cardiac CCTA were prospectively collected in a dedicated database. Clinical follow-up visits were scheduled 1 to 3 months after LAAO, and biannually thereafter. Control CCTA was performed before the first clinical visit and repeat exams were encouraged if patency or HAT was found. Endpoint and clinical definitions were described in our recently published series19.

IMAGING ACQUISITION

The CCTA follow-up was acquired 3 to 6 months after LAAO implantation. Prospective ECG-gated CCTA was performed with the 256-slice Brilliance iCT scanner (Philips, Best, the Netherlands). Cardiac CT images were acquired using a biphasic injection protocol: 40 cc of iodinated contrast (Iomeprol 350 mg/mL; Bracco, Milan, Italy) was administered intravenously via 18G cubital catheter at the rate of 5 mL/s, followed by a 40 ml flush of saline.

A bolus tracking method was applied for arterial phase images, the region of interest being positioned in the ascending aorta and a threshold of 100 Hounsfield units (HU). One volume focused on the LAA at 30-40% of the R-R intervals was acquired in the arterial and venous phase. Digital post-processing and reconstruction were performed with Philips IntelliSpace Portal software to assess LAAO device positioning, patency and presence/location of DRT.

DEFINITIONS AND CCTA ANALYSIS

LAA shape was categorised into chicken wing, windsock, cauliflower or cactus on a volume-rendering reconstruction20. Patency (incomplete device sealing) was defined as attenuation coefficient in the LAA distal to the device >100 HU in the arterial phase12 and LAA/LA attenuation coefficient ratio >0.2521. In order to describe the different mechanisms of patency, the device lobe perimeter was divided into terciles (proximal, mid and distal) and each region into quadrants (antero-superior, antero-inferior, postero-superior and postero-inferior). Three different mechanisms of patency were considered (Central illustration): 1) fabric permeability, defined as device permeability observed by passage of the contrast through the non-endothelialised polyethylene terephthalate membrane despite appropriate proximal device apposition9; 2) malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe, in which contrast was present in any of the proximal quadrants (not fulfilling PDL criteria) enabling communication between the LA and the distal LAA through the lobe; and 3) PDL, defined as a contrast enhancement trail all along the lobe perimeter allowing communication between the LA and the distal LAA22. All signs of stability for the Amulet were systematically evaluated on each CCTA scan: (1) tyre-shaped lobe, (2) separation of the lobe from the disc, (3) concavity of the disc, (4) axis of the lobe should be perpendicular to the neck axis at the landing zone, and (5) lobe depth: two thirds of the lobe positioned distal to the circumflex artery13. In addition, lobe compression percentage was calculated as: (manufacturer device diameter – largest measured diameter)/manufacturer device diameter x 100. An enhancement defect on the atrial surface of LAAO device in the CCTA arterial phase was defined as HAT. Following the recently proposed classification, HAT was divided into low-grade HAT (<3 mm of thickness and laminar shape) and high-grade HAT/definite DRT (>3 mm, irregular or pedunculated) (Figure 1)17.

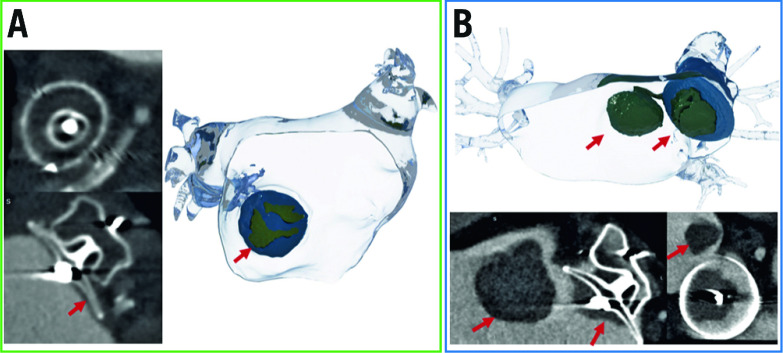

Central illustration.

The different mechanisms of device patency on CCTA. A) Complete sealing of the LAA. B) Fabric permeability through the non-endothelialised device membrane. C) Malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe, contrast passes into the LAA from the gap in the proximal part of the poorly positioned lobe and through the device body. D) Peri-device leak, the contrast passes through the gap between the device lobe and the LAA wall. Red arrows indicate the direction of the contrast flow. CCTA: cardiac computed tomography angiography; LAA: left atrial appendage

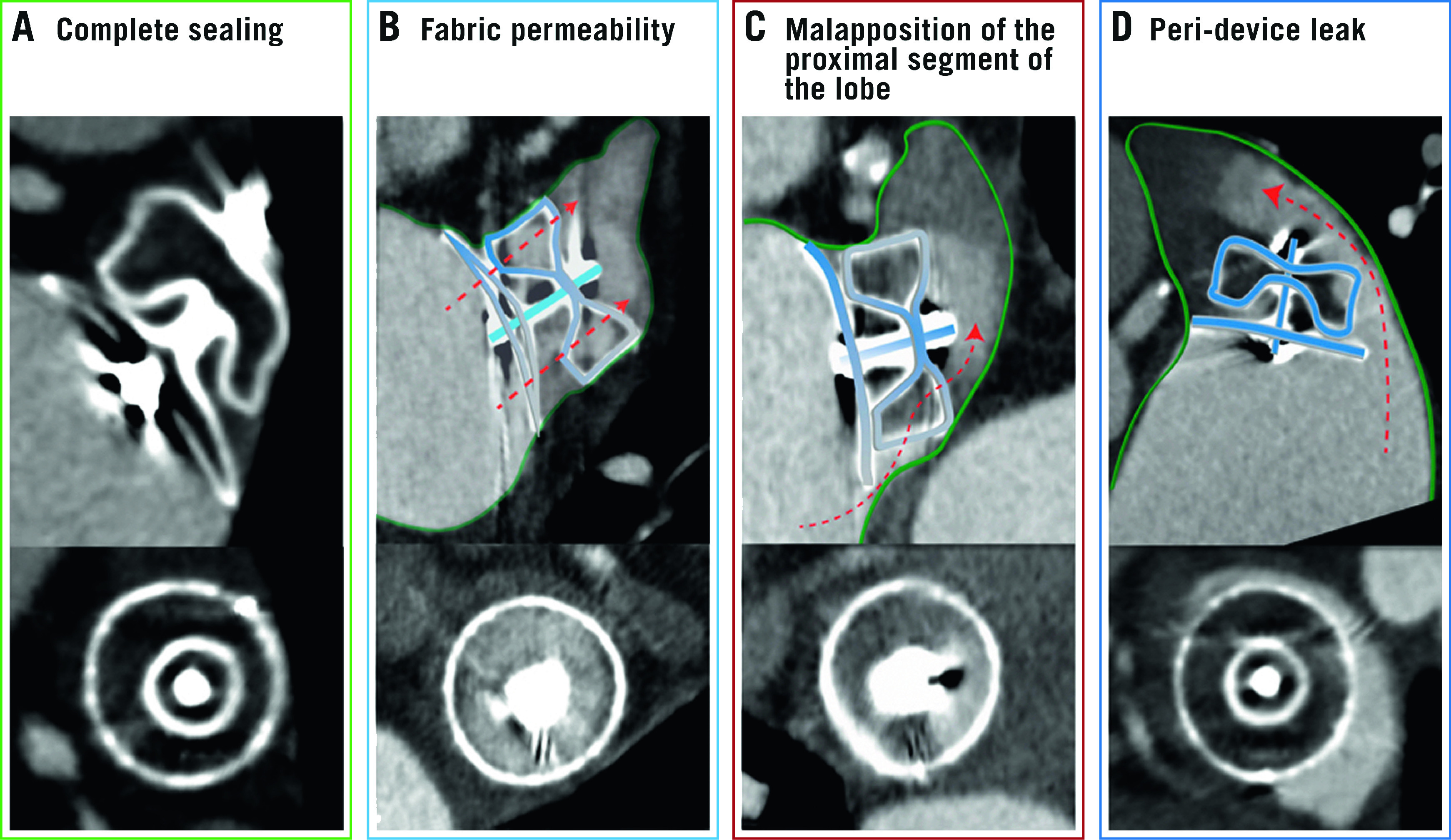

Figure 1.

Device-related thrombosis. 3D rendering and CCTA images showing device-related thrombosis (red arrow). A) Low-grade HAT (<3 mm of thickness). B) High-grade HAT (>3 mm of thickness) device and left atrium thrombus. CCTA: cardiac computed tomography angiography; HAT: hypo-attenuated thickening

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are described as mean±standard deviation (SD) or as median with interquartile range (IQR; 25th-75th percentile), depending on the distribution of the variables. Comparisons of quantitative variables between groups were performed with the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables are expressed as counts (percentage) and were compared with Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of patency after LAAO. Candidate predictors included patient and procedural characteristics of interest such as LAA morphology, device stability criteria or medical treatment. Variables that showed marginal associations with the outcome on univariate testing (p<0.20) were included in the multivariable analyses and a backward stepwise selection method was conducted. The significance of the Cox multivariable regression was determined with the Wald chi-square test. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

One hundred and thirty-seven consecutive patients who underwent LAAO with either Amulet (n=130) or ACP (n=7) devices and subsequent CCTA surveillance imaging were included. All patients had non-valvular AF and were deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation therapy or had presented cerebrovascular accidents despite anticoagulation. The mean age of the study population was 76.8±7.2 years, 64.2% male, mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.6±1.5, and HAS-BLED score 2.8±0.9. Clinical outcomes in our series have been published recently19.

DEVICE FINDINGS ON FOLLOW-UP CCTA

CCTA findings at follow-up are summarised in Table 1. Our sample had 1.5±0.8 scans per patient and the mean X-ray exposure per study was 2.9±0.5 mSv. The first available CCTA was performed at a median time of 106 days (IQR: 81 to 186 days) post-procedure.

Table 1. Follow-up CCTA findings.

| Device stability criteria | (n=137) | |

| Tyre-shaped lobe | 66 (48.2%) | |

| Separation lobe-disc | 119 (86.9%) | |

| Concavity of disc | 95 (69.3%) | |

| Lobe-LAA axis misalignment | 74 (54.0%) | |

| Lobe depth | 112 (81.8%) | |

| Lobe compression ≥10% | 67 (48.9%) | |

| LAA patency | First FU CCTA | Last FU CCTA |

| All-type patency | 78 (56.9%) | 75 (54.7%) |

| Peri-device leak | 27 (19.7%) | 27 (19.7%) |

| Proximal malapposition | 43 (31.4%) | 43 (31.4%) |

| Fabric permeability | 8 (5.8%) | 5 (3.6%) |

| HAT on atrial aspect of the device | ||

| All-degree HAT | 23 (16.8%) | |

| Low-grade HAT | 16 (11.7%) | |

| High-grade HAT (definite DRT) | 7 (5.1%) | |

| Results expressed as n (%). CTA: computed tomography angiography; DRT: device-related thrombosis; FU: follow-up; HAT: hypo-attenuated thickness | ||

LAA patency was observed in 56.9% (n=78) of patients. The most common mechanism was malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe (55.1%) followed by PDL (34.6%) and fabric permeability (5.8%). Mechanisms of patency are illustrated in the Central illustration. In patients with PDL, the mean gap size was 5.9±3.5 mm, with 55.6% (n=15) of leaks being larger than 5 mm. The most common location for both malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe and PDL was the postero-inferior LAA quadrant (71.1% and 81.5%, respectively).

Chicken-wing shape was associated with a higher incidence of device patency compared with other LAA morphologies (68.0% vs 50.6%; p=0.047). All stability criteria were associated with greater rates of LAA sealing. Twenty-seven patients (19.7%) fulfilled all criteria, but most patients (72.3%) fulfilled at least three out of five. In a multivariate regression analysis, lobe-LAA axis misalignment was the only independent predictor of device patency after LAAO (HR 38.3, 95% CI: 13.6-107.0; p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Predictors of patency after LAAO.

| Variable | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Chicken-wing morphology | 2.077 (1.003-4.300) | 0.049 | 1.707 (0.599-4.861) | 0.317 |

| Tyre-shaped lobe | 0.399 (0.199-0.799) | 0.010 | 0.689 (0.239-1.988) | 0.490 |

| Separation lobe-disc | 0.623 (0.219-1.770) | 0.374 | NA | NA |

| Concavity of disc | 0.478 (0.222-1.029) | 0.059 | 0.568 (0.186-1.736) | 0.321 |

| Lobe-LAA axis misalignment | 35.06 (13.34-92.16) | <0.001 | 38.17 (13.62-106.98) | <0.001 |

| Lobe depth | 0.698 (0.284-1.711) | 0.432 | NA | NA |

| Lobe compression (increase by 1%) | 0.942 (0.901-0.985) | 0.009 | 1.014 (0.955-1.078) | 0.646 |

| Platelet count (increase by 1,000/mL) | 0.977 (0.993-1.000) | 0.081 | 0.998 (0.992-1.003) | 0.382 |

| Procedural ICE vs TOE | 1.292 (0.648-2.577) | 0.468 | NA | NA |

| Time first follow-up CCTA | 0.999 (0.996-1.001) | 0.192 | 0.999 (0.996-1.003) | 0.641 |

| Antiplatelet/anticoagulant treatment | 0.250 (0.854-5.931) | 0.101 | 3.635 (0.905-14.60) | 0.069 |

| CCTA: cardiac computed tomography angiography; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; ICE: intracardiac echocardiography; LAA: left atrial appendage; NA: not applicable; TOE: transoesophageal echocardiography | ||||

Among patients with residual LAA patency in the post-procedural CCTA, 34.6% (n=27) had at least one additional follow-up scan. Patency status and mechanism remained unchanged in patients with PDL or malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe, whereas complete LAA patency resolution was observed in three out of six patients with fabric permeability, probably due to late device endothelialisation.

After a median follow-up of 608 days (IQR: 372-875 days), patency was not associated with an increase in mortality, cerebrovascular accident or bleeding events. However, patients with sealed LAA (no patency) presented higher rates of HAT, driven mainly by low-grade HAT (4.4% vs 1.3%; p<0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3. Outcome rates during follow-up according to patency.

| Outcomes | Overall (n=137) | Patency group (n=78) | No patency group (n=59) | p-value | |||

| Events | Rate | Events | Rate | Events | Rate | ||

| All-cause death | 25 (18.2) | 10.5 | 17 (21.8) | 13.6 | 8 (13.6) | 7.0 | 0.118 |

| CV death | 8 (5.8) | 3.3 | 6 (7.7) | 4.8 | 2 (3.4) | 1.7 | 0.221 |

| Any ischaemic CVA | 6 (4.4) | 2.5 | 4 (5.1) | 3.2 | 2 (3.4) | 1.7 | 0.516 |

| Stroke | 4 (2.9) | 1.7 | 2 (2.6) | 1.6 | 2 (3.4) | 1.7 | 0.935 |

| TIA | 2 (1.5) | 8.4 | 2 (2.6) | 16.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.272 |

| Any bleeding | 23 (16.8) | 9.6 | 13 (16.7) | 10.4 | 10 (16.9) | 8.7 | 0.685 |

| Major bleeding | 14 (10.2) | 5.9 | 8 (10.3) | 6.4 | 6 (10.2) | 5.2 | 0.723 |

| Minor bleeding | 13 (9.5) | 5.4 | 7 (9.0) | 5.6 | 6 (10.2) | 5.2 | 0.911 |

| Any HAT | 23 (16.8) | 3.8 | 7 (9.0) | 2.3 | 16 (27.1) | 5.4 | 0.054 |

| Low-grade HAT | 16 (11.7) | 2.6 | 4 (5.1) | 1.3 | 12 (20.3) | 4.4 | 0.043 |

| Definite DRT | 7 (5.1) | 1.2 | 3 (3.8) | 1.0 | 4 (6.8) | 1.3 | 0.698 |

| Number of events is expressed as n (%). Rates are per 100 patient-years. CV: cardiovascular; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; DRT: device-related thrombosis; HAT: hypo-attenuated thickening; TIA: transient ischaemic attack | |||||||

An ED on the atrial side of the LAA device described as HAT was found in 16.8% (n=23) of patients, 16 (11.7%) of whom had low-grade HAT and 7 (5.1%) of whom had high-grade HAT or definite DRT. Table 4 shows clinical and CCTA characteristics according to the presence and grade of HAT. Patients with high-grade HAT were older and had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores compared with those without high-grade HAT (p<0.005). Patients with HAT had higher rates of renal dysfunction (78.3% vs 55.3%; p<0.005) and had received anticoagulation therapy less frequently post-procedure (21.7 vs 41.1%, p=0,063) than patients without HAT. HAT (whether low-grade or high-grade HAT) was not associated with a significant increase in mortality, cerebrovascular accidents or bleeding events (Table 5).

Table 4. Clinical and CCTA characteristics according to device-related thrombosis.

| Variables | No HAT (n=114) | HAT | p-value | p-value | |||

| All-degree HAT (n=23) | Low-grade HAT (n=16) | Definite DRT (n=7) | All-degree HAT vs no HAT | Definite DRT vs no definite DRT | |||

| Age, years | 76.1±7.0 | 80.1±7.7 | 78.7±8.3 | 83.3±5.5 | 0.016 | 0.014 | |

| Renal insufficiency | 63 (55.3%) | 18 (78.3%) | 13 (81.3%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0.041 | 0.700 | |

| LVEF, % | 57.6±12.7 | 57.6±9.4 | 59.8±6.8 | 53.6±12.7 | 0.987 | 0.373 | |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 203.6±84.5 | 218.7±135.2 | 233.7±152.6 | 184.3±82.5 | 0.487 | 0.532 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 4.5±1.5 | 4.9±1.8 | 4.6±1.9 | 5.7±1.5 | 0.260 | 0.045 | |

| Discharge treatment | Single APT | 45 (40.2%) | 12 (52.2%) | 8 (50.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0.268 | 0.443 |

| Dual APT | 6 (5.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Anticoagulation | 39 (34.8%) | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (14.3%) | |||

| APT + anticoagulation | 7 (6.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| No treatment | 15 (13.4%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (28.6%) | |||

| LAA patency | 71 (62.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 4 (25.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0.005 | 0.464 | |

| Uncovered PVR | 53 (48.6%) | 16 (69.6%) | 11 (68.8%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0.068 | 0.444 | |

| Length to uncovered PVR, mm | 6.3±7.5 | 9.6±7.9 | 9.8±8.3 | 9.1±7.5 | 0.061 | 0.431 | |

| Results expressed as n (%) for categorical variables and mean±SD for quantitative variables. APT: antiplatelet therapy; DRT: device-related thrombosis; HAT: hypo-attenuated thickness; LAA: left atrial appendage; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PVR: pulmonary vein ridge | |||||||

Table 5. Outcome rates during follow-up according to HAT.

| Outcomes | No HAT (n=114) | HAT | p-value | p-value | ||||||

| All-degree HAT (n=23) | Low-grade HAT (n=16) | High-grade HAT (n=7) | ||||||||

| Events | Rate | Events | Rate | Events | Rate | Events | Rate | All-degree HAT vs no HAT | Definite DRT vs no definite DRT | |

| All-cause death | 21 (18.4) | 10.3 | 4 (17.4) | 11.6 | 2 (12.5) | 6.9 | 2 (28.6) | 22.0 | 0.787 | 0.315 |

| CV death | 7 (6.1) | 3.4 | 1 (4.3) | 2.9 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (14.3) | 11.0 | 0.962 | 0.302 |

| Ischaemic CVA | 5 (4.4) | 2.4 | 1 (4.3) | 2.9 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (14.3) | 11.0 | 0.816 | 0.228 |

| Stroke | 3 (2.6) | 1.5 | 1 (4.3) | 2.9 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (14.3) | 11.0 | 0.567 | 0.152 |

| TIA | 2 (1.8) | 1.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.732 | 0.925 |

| Any bleeding | 20 (17.5) | 9.8 | 3 (13.0) | 8.7 | 3 (18.8) | 10.3 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.904 | 0.409 |

| Major | 13 (11.4) | 6.4 | 1 (4.3) | 2.9 | 1 (6.3) | 3.4 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.491 | 0.581 |

| Minor | 10 (8.8) | 4.9 | 3 (13.0) | 8.7 | 3 (18.8) | 10.3 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.393 | 0.604 |

| Number of events is expressed as n (%). Rates are per 100 patient-years. CV: cardiovascular; CVA: cerebrovascular; DRT: device-related thrombosis; HAT: hypo-attenuated thickness; TIA: transient ischaemic attack | ||||||||||

After definite DRT diagnosis, all patients received anticoagulation therapy (low-molecular-weight heparin) and underwent subsequent CCTA. Thrombus resolution was observed in all patients but one, with persistent DRT extending to the left atrium, without clinical events. One patient with DRT resolution presented a non-fatal ischaemic stroke on antiplatelet monotherapy, although no cardiac imaging was performed to rule out a re-DRT.

Among patients with low-grade HAT, medical treatment at the time of diagnosis included no antithrombotic therapy (n=5, unchanged), single antiplatelet therapy (n=10, unchanged in all but one downgraded to no antithrombotic therapy 24 months post-procedure), and anticoagulation plus single antiplatelet therapy (n=2) in whom anticoagulation was interrupted 3 and 12 months post-procedure, respectively. No patients with low-grade HAT experienced cardioembolic events during follow-up. Eight patients (47.1%) were followed-up with CCTA and the HAT image persisted unchanged in all of them, 6 under single antiplatelet therapy and 2 without any antithrombotic treatment.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are the following. 1) Up to half of patients undergoing LAAO had residual LAA patency as assessed by CCTA, most commonly due to malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe. 2) Fulfilment of device release criteria by CCTA was associated with increased sealing rates after LAAO. 3) Device-lobe misalignment was the strongest predictor for residual patency. 4) Residual patency and low-grade HAT were not associated with increased risk of cerebrovascular events.

DEVICE PATENCY AND MECHANISMS

Follow-up imaging with either TOE or CCTA is recommended after LAAO, primarily to assess for PDL or DRT. Given its higher resolution and non-invasiveness, CCTA has emerged as an increasingly used tool for device surveillance in elderly and frail patients undergoing LAAO. The reported rate of LAA patency by CCTA with AMPLATZER devices has ranged from 29% to 71%8,9,10,11,12,13, being substantially higher than that reported by TOE (2% to 47%)6,23. Recent studies have suggested new CCTA classifications of PDL severity based on sealing at the device disc, device lobe and distal LAA patency24. However, data regarding evaluation of the mechanisms leading to residual patency on CCTA remain scarce25. We therefore followed a CCTA-based classification system to simplify the assessment of the underlying mechanisms of LAA patency: PDL (contrast diffusion all along the uncovered lobe), malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe (contrast partially present in any of the proximal quadrants, allowing communication between the LA and the distal LAA through the lobe), and fabric permeability (through the device cover). In the present study, malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe was the most common cause of residual patency (55%), followed by PDL (35%) and fabric permeability (10%). It is worthy of note that, whereas significant PDL may be easily identified by TOE, malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe and fabric permeability are generally undetectable by TOE. Additionally, these findings may be visualised solely on CCTA, underscoring a potential advantage of CCTA over TOE in the surveillance imaging process. Patency was most commonly located at the postero-inferior quadrant (70-80%). Our findings are in line with those reported by Korsholm et al24 in the largest study evaluating PDL post LAAO by CCTA to date, which identified residual patency in 59% of the patients, most commonly being infero-posterior (86%), without a visible leak at the disc or lobe (eventually corresponding to fabric permeability) in 9% of the patients24.

OCCLUDER STABILITY CRITERIA AND PATENCY

Confirmation of the five signs of device stability is advised prior to release of an ACP or Amulet device. However, our findings suggest, for the first time, that achieving most of those stability criteria may be important not only to prevent device embolisation, but also to achieve complete sealing of the LAA. Indeed, fulfilment of any stability criteria plus lobe compression over 10% was associated with increased LAA sealing following LAAO. Hence, confirmation of such signs should not be limited to the procedure, but rather reassessed during post-surveillance CCTA to detect complete LAA occlusion. Among all five device release criteria, suboptimal coaxial alignment emerged as the strongest predictor for residual patency following LAAO (HR=38.3), as demonstrated by previous studies evaluating CCTA post LAAO, since off-axis implantation of a circular plug (such as ACP/Amulet) on a non-circular LAA orifice may result in a gap between the edge of the device and the atrial wall. In a landmark study on CCTA post LAAO (n=45), Saw et al12 identified the presence of an off-axis device lobe at the landing zone in the majority of patients with residual patency, compared with those with sealed LAA. More recently, Korsholm et al24 identified the lack of coaxial alignment, along with larger LAA diameters and lower device compression, as independent predictors of PDL. Conversely, neither patient characteristics nor antithrombotic treatment or its initiation delay after the procedure were associated with patency in our study. Importantly, both proximal malapposition and PDL remained mostly unchanged throughout subsequent CCTA exams, and only three patients exhibited fabric leak resolution that might be attributable to device endothelialisation12,13,24.

PATENCY AND CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The Munich consensus established a threshold of 5 mm for relevant leaks based on surgical LAA closure data26. Contrary to their surgical counterparts, an analysis from the PROTECT-AF study using the WATCHMAN device and other published studies on transcatheter LAAO have failed to find any association between PDL and clinical events10,23,27,28. In our study, LAA patency was not related to an increased risk of death (all-cause or cardiovascular death) or cerebral/peripheral embolism regardless of its mechanism or PDL gap width. It has been suggested that patients with residual large PDL may be continued on long-term OAC or treated with additional occluders, with uncertain clinical benefit2. In our series, the decision to extend OAC was left to the treating physician’s criteria and no residual PDLs were treated percutaneously. Notably, despite higher rates of OAC in patients with patent LAA (42% vs 32%), no increase in bleeding rates was observed.

LOW-GRADE HAT VERSUS HIGH-GRADE HAT AND CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The incidence of DRT following LAAO with the ACP/Amulet has ranged from 2% to 18%, with wide variations depending on device type, post-procedural antithrombotic therapies, and timing and frequency of control TOE14,18. By CCTA, HAT has been defined as any ED on the device surface and is subclassified as low-grade or high-grade (or definite DRT). Importantly, this terminology has only been evaluated for AMPLATZER type devices. DRT has been associated with a threefold to fivefold increased risk of stroke and systemic embolism. In our series, the incidence of ischaemic events during follow-up was low (4.3%); no association was found between HAT and stroke, probably due to a longer anticoagulation therapy in patients with HAT (median time of 283 days compared to 138 days in patients without HAT; p=0.029) and a higher incidence of low-grade HAT. It must be emphasised that rates of stroke were higher among patients with high-grade HAT, compared with those with low-grade HAT (11.0% vs 0%, p=0.152). As previously reported, patients with DRT were older, had higher thromboembolic risk scores and worse renal function. In the Amulet observational study, most DRTs developed near the superior edge of the Amulet disc close to the pulmonary vein ridge, suggesting a large LAA orifice with an uncovered ridge as being a potential contributing factor14. In our series, higher rates of uncovered pulmonary vein ridges were also found in patients with HAT (69.6% vs 48.6%), although no statistical significance was achieved. Contrary to the findings of Korsholm et al, who observed spontaneous resolution of most low-grade HAT (suggesting an early, transient stage of thrombus formation), the low-grade HAT observed in the present study remained constant regardless of the antithrombotic therapy. These patients remained uneventful during follow-up, suggesting low-grade HAT to be a benign phenomenon of endothelialisation17. This seems to be supported by an autopsy study on 10 canine hearts explanted 90 days after LAAO with ACP devices, which revealed that the atrial face of the device was covered by a neointima composed of mature fibrous connective tissue29.

Interestingly, occluded LAA (absence of patency) was associated with increased rates of low-grade HAT, indicating that complete LAA occlusion may favour device endothelialisation.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. 1) Its retrospective nature and the lack of data on TOE during follow-up to compare rates of patency/PDL and DRT with the different diagnostic tools are limitations. 2) Despite being one of the series with longest follow-up reported, the limited sample size of this single-centre study and the relatively low rates of HAT prevented us from analysing potential predictors. In addition, the finding of HAT was not correlated with histology/autopsy; the benign behaviour of low-grade HAT should be addressed in future research. 3) This work has specifically studied patients treated with the AMPLATZER devices, mainly Amulet. Therefore, it is not possible to draw any conclusions on CCTA findings on WATCHMAN or other LAAO devices.

Conclusions

Up to half of patients undergoing LAAO with ACP/Amulet had residual LAA patency on CCTA follow-up, mostly due to malapposition of the proximal segment of the device lobe. Fulfilment of device stability criteria by CCTA was associated with increased rates of LAA sealing, whereas device misalignment carried the highest risk of residual patency. While patients with high-grade HAT exhibited higher rates of mortality and stroke, neither patency nor HAT was associated with adverse outcomes. Low-grade HAT may be related to a benign, uneventful, endothelialisation process favoured by complete LAA occlusion.

The definition, prevalence and clinical significance of device patency and thrombosis after left atrial appendage occlusion assessed by computed tomography are not yet clearly established. This study provides a clear illustration of the different mechanisms of patency and describes its association with device release criteria and cerebrovascular events during follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Arzamendi, X. Millán and C.H. Li report being consultants and proctors for Abbott. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- ACP

AMPLATZER Cardiac Plug

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- CCTA

cardiac computed tomography angiography

- DRT

device-related thrombosis

- ED

enhancement defect

- HAT

hypo-attenuated thickening

- ICE

intracardiac echocardiography

- LAA

left atrial appendage

- LAAO

left atrial appendage occlusion

- MAE

major adverse events

- OAC

oral anticoagulation

- PDL

peri-device leak

- TIA

transient ischaemic attack

- TOE

transoesophageal echocardiography

Contributor Information

Victor Agudelo, Interventional Cardiology Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Xavier Millán, Interventional Cardiology Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Chi-Hion Li, Cardiac Imaging Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Abdel-Hakim Moustafa, Cardiac Imaging Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Lluis Asmarats, Interventional Cardiology Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Antonio Serra, Interventional Cardiology Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Dabit Arzamendi, Interventional Cardiology Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

References

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DR, Reddy VY, Turi ZG, Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, Mullin C, Sick P PROTECT AF Investigators. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized non-inferiortiy trial. Lancet. 2009;374:534–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61343-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DR, Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SK, Huber K, Reddy VY. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma LV, Ince H, Kische S, Pokushalov E, Schmitz T, Schmidt B, Gori T, Meincke F, Protopopov AV, Betts T, Foley D, Sievert H, Mazzone P, De Potter T, Vireca E, Stein K, Bergmann MW EWOLUTION Investigators. Efficacy and safety of left atrial appendage closure with WATCHMAN in patients with or without contraindication to oral anticoagulation: 1-Year follow-up outcome data of the EWOLUTION trial. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:1302–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzikas A, Shakir S, Gafoor S, Omran H, Berti S, Santoro G, Kefer J, Landmesser U, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sievert H, Tichelbäcker T, Kanagaratnam P, Nietlispach F, Aminian A, Kasch F, Freixa X, Danna P, Rezzaghi M, Vermeersch P, Stock F, Stolcova M, Costa M, Ibrahim R, Schillinger W, Meier B, Park JW. Left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: multicentre experience with the AMPLATZER Cardiac Plug. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:1170–9. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser U, Schmidt B, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Lam SCC, Park JW, Tarantini G, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Geist V, Della Bella P, Colombo A, Zeus T, Omran H, Piorkowski C, Lund J, Tondo C, Hildick-Smith D. Left atrial appendage occlusion with the AMPLATZER Amulet device: periprocedural and early clinical/echocardiographic data from a global prospective observational study. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:867–76. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glikson M, Wolff R, Hindricks G, Mandrola J, Camm AJ, Lip GYH, Fauchier L, Betts TR, Lewalter T, Saw J, Tzikas A, Sternik L, Nietlispach F, Berti S, Sievert H, Bertog S, Meier B. EHRA/EAPCI expert consensus statement on catheter-based left atrial appendage occlusion: an update. EuroIntervention. 2020;15:1133–80. doi: 10.4244/EIJY19M08_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaguszewski M, Manes C, Puippe G, Salzberg S, Müller M, Falk V, Lüscher T, Luft A, Alkadhi H, Landmesser U. Cardiac CT and echocardiographic evaluation of peri-device flow after percutaneous left atrial appendage closure using the AMPLATZER cardiac plug device. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:306–12. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qamar SR, Jala S, Nicolaou S, Tsang M, Gilhofer T, Saw J. Comparison of cardiac computed tomography angiography and transoesophageal echocardiography for device surveillance after left atrial appendage closure. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:663–70. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A, Gallet R, Riant E, Deux JF, Boukantar M, Mouillet G, Dubois-Randé JL, Lellouche N, Teiger E, Lim P, Ternacle J. Peridevice Leak After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Impact. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:405–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YM, Kim JS, Kim TH, Uhm JS, Shim CY, Joung B, Hong GR, Lee MH, Jang YS, Pak HN. Delayed left atrial appendage contrast filling in computed tomograms after percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion. J Cardiol. 2017;70:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw J, Fahmy P, DeJong P, Lempereur M, Spencer R, Tsang M, Gin K, Jue J, Mayo J, McLaughlin P, Nicolaou S. Cardiac CT angiography for device surveillance after endovascular left atrial appendage closure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:1198–206. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochet H, Iriart X, Sridi S, Camaioni C, Corneloup O, Montaudon M, Laurent F, Selmi W, Renou P, Jalal Z, Thambo JB. Left atrial appendage patency and device-related thrombus after percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion: a computed tomography study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1351–61. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminian A, Schmidt B, Mazzone P, Berti S, Fischer S, Montorfano M, Lam SCC, Lund J, Asch FM, Gage R, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Omran H, Tarantini G, Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Incidence, Characterization, and Clinical Impact of Device-Related Thrombus Following Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion in the Prospective Global AMPLATZER Amulet Observational Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1003–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmarats L, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Nombela-Franco L, Arzamendi D, Peral V, Nietlispach F, Latib A, Maffeo D, Gonzalez-Ferreiro R, Rodriguez-Gabella T, Agudelo V, Alamar M, Ghenzi RA, Mangieri A, Bernier M, Rodés-Cabau J. Recurrence of Device-Related Thrombus After Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure. Circulation. 2019;140:1441–3. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukkipati SR, Kar S, Holmes DR, Doshi SK, Swarup V, Gibson DN, Maini B, Gordon NT, Main ML, Reddy VY. Device-Related Thrombus After Left Atrial Appendage Closure: Incidence, Predictors, and Outcomes. Circulation. 2018;138:874–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsholm K, Jensen JM, Norgaard BL, Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Detection of Device-Related Thrombosis Following Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion: A Comparison Between Cardiac Computed Tomography and Transesophageal Echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e008112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plicht B, Konorza TF, Kahlert P, Al-Rashid F, Kaelsch H, Jánosi RA, Buck T, Bachmann HS, Siffert W, Heusch G, Erbel R. Risk factors for thrombus formation on the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug after left atrial appendage occlusion. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:606–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo V, Millan X, Li CH, Asmarats L, Fernandez-Peregrina E, Santalo M, Jimenez-Kockar M, Gheorghe L, Serra A, Arzamendi D. Impact of the CHA2DS2-VASc score on late clinical outcomes in patients undergoing left atrial appendage occlusion. Int J Cardiol. 2020;319:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Anselmino M, Mohanty P, Salvetti I, Gili S, Horton R, Sanchez JE, Bai R, Mohanty S, Pump A, Cereceda Brantes M, Gallinghouse GJ, Burkhardt JD, Cesarani F, Scaglione M, Natale A, Gaita F. Does the left atrial appendage morphology correlate with the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation? Results from a multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:531–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsi R, Nath B, Luetkens JA, Schwab JO, Schild HH, Naehle CP. Can Contrast-Enhanced Multi-Detector Computed Tomography Replace Transesophageal Echocardiography for the Detection of Thrombogenic Milieu and Thrombi in the Left Atrial Appendage: A Prospective Study with 124 Patients. Rofo. 2016;188:45–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner S, Behnes M, Wenke A, Sartorius B, Ansari U, Akin M, Mashayekhi K, Vogler N, Haubenreisser H, Schoenberg SO, Borggrefe M, Akin I. Assessment of peri-device leaks after interventional left atrial appendage closure using standardized imaging by cardiac computed tomography angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;35:725–31. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1493-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freixa X, Tzikas A, Sobrino A, Chan J, Basmadjian AJ, Ibrahim R. Left atrial appendage closure with the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug: impact of shape and device sizing on follow-up leaks. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1023–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsholm K, Jensen JM, Norgaard BL, Samaras A, Saw J, Berti S, Tzikas A, Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Peridevice Leak Following Amplatzer Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion: Cardiac Computed Tomography Classification and Clinical Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw J, Tzikas A, Shakir S, Gafoor S, Omran H, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Kefer J, Aminian A, Berti S, Santoro G, Nietlispach F, Moschovitis A, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Stammen F, Tichelbäcker T, Freixa X, Ibrahim R, Schillinger W, Meier B, Sievert H, Gloekler S. Incidence and Clinical Impact of Device-Associated Thrombus and Peri-Device Leak Following Left Atrial Appendage Closure With the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzikas A, Holmes DR, Jr, Gafoor S, Ruiz CE, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Diener HC, Cappato R, Kar S, Lee RJ, Byrne RA, Ibrahim R, Lakkireddy D, Soliman OI, Nabauer M, Schneider S, Brachmann J, Saver JL, Tiemann K, Sievert H, Camm AJ, Lewalter T. Percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion: the Munich consensus document on definitions, endpoints, and data collection requirements for clinical studies. Europace. 2017;19:4–15. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viles-Gonzalez JF, Kar S, Douglas P, Dukkipati S, Feldman T, Horton R, Holmes D, Reddy VY. The clinical impact of incomplete left atrial appendage closure with the Watchman Device in patients with atrial fibrillation: a PROTECT AF (Percutaneous Closure of the Left Atrial Appendage Versus Warfarin Therapy for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:923–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, Neuzil P, Huber K, Halperin JL, Holmes D PROTECT AF Investigators. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure for stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: 2.3-Year Follow-up of the PROTECT AF (Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) Trial. Circulation. 2013;127:720–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass JL. Transcatheter occlusion of the left atrial appendage--experimental testing of a new Amplatzer device. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76:181–5. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]