1 Preamble

Guidelines summarize and evaluate available evidence with the aim of assisting health professionals in proposing the best management strategies for an individual patient with a given condition. Guidelines and their recommendations should facilitate decision making of health professionals in their daily practice. However, the final decisions concerning an individual patient must be made by the responsible health professional(s) in consultation with the patient and caregiver as appropriate.

A great number of guidelines have been issued in recent years by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and its partners such as the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), as well as by other societies and organizations. Because of their impact on clinical practice, quality criteria for the development of guidelines have been established in order to make all decisions transparent to the user. The recommendations for formulating and issuing ESC Guidelines can be found on the ESC website (https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines). The ESC Guidelines represent the official position of the ESC on a given topic and are regularly updated.

In addition to the publication of Clinical Practice Guidelines, the ESC carries out the EURObservational Research Programme of international registries of cardiovascular diseases and interventions which are essential to assess diagnostic/therapeutic processes, use of resources and adherence to guidelines. These registries aim at providing a better understanding of medical practice in Europe and around the world, based on high-quality data collected during routine clinical practice.

The Members of this Task Force were selected by the ESC and EACTS, including representation from relevant ESC and EACTS sub-specialty groups, in order to represent professionals involved with the medical care of patients with this pathology. Selected experts in the field undertook a comprehensive review of the published evidence for management of a given condition according to ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee (CPG). A critical evaluation of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures was performed, including assessment of the risk-benefit ratio. The level of evidence and the strength of the recommendation of particular management options were weighed and graded according to predefined scales, as outlined below.

The experts of the writing and reviewing panels provided declaration of interest forms for all relationships that might be perceived as real or potential sources of conflicts of interest. Their declarations of interest were reviewed according to the ESC declaration of interest rules and can be found on the ESC website (http://www.escardio.org/guidelines) and have been compiled in a report and published in a supplementary document simultaneously to the guidelines.

This process ensures transparency and prevents potential biases in the development and review processes. Any changes in declarations of interest that arise during the writing period were notified to the ESC and updated. The Task Force received its entire financial support from the ESC and EACTS without any involvement from the healthcare industry.

The ESC CPG supervises and coordinates the preparation of new guidelines. The Committee is also responsible for the endorsement process of these guidelines. The ESC Guidelines undergo extensive review by the CPG and external experts. After appropriate revisions the guidelines are signed-off by all the experts involved in the Task Force. The finalized document is signed-off by the CPG for publication in the European Heart Journal and the European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. The guidelines were developed after careful consideration of the scientific and medical knowledge and the evidence available at the time of their dating.

The task of developing ESC/EACTS Guidelines also includes the creation of educational tools and implementation programmes for the recommendations including condensed pocket guideline versions, summary slides, summary cards for non-specialists and an electronic version for digital applications (smartphones, etc.). These versions are abridged and thus, for more detailed information, the user should always access to the full text version of the guidelines, which is freely available via the ESC and EACTS website and hosted on the EHJ and EJCTS website. The National Cardiac Societies of the ESC are encouraged to endorse, adopt, translate and implement all ESC Guidelines. Implementation programmes are needed because it has been shown that the outcome of disease may be favourably influenced by the thorough application of clinical recommendations.

Health professionals are encouraged to take the ESC/EACTS Guidelines fully into account when exercising their clinical judgment, as well as in the determination and the implementation of preventive, diagnostic or therapeutic medical strategies. However, the ESC/EACTS Guidelines do not override in any way whatsoever the individual responsibility of health professionals to make appropriate and accurate decisions in consideration of each patient's health condition and in consultation with that patient or the patient's caregiver where appropriate and/or necessary. It is also the healthcare professional's responsibility to verify the rules and regulations applicable in each country to drugs and devices at the time of prescription.

2 Introduction

2.1 WHY DO WE NEED NEW GUIDELINES ON VALVULAR HEART DISEASE?

Since the publication of the previous version of the guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (VHD) in 2017, new evidence has accumulated, particularly on the following topics:

Epidemiology: the incidence of the degenerative aetiology has increased in industrialized countries while, unfortunately, rheumatic heart disease is still too frequently observed in many parts of the world.1,2,3

Current practices regarding interventions and medical management have been analysed in new surveys at the national and European level.

Non-invasive evaluation using three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography (CCT), cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), and biomarkers plays a more and more central role.

New definitions of severity of secondary mitral regurgitation (SMR) based on the outcomes of studies on intervention.

New evidence on anti-thrombotic therapies leading to new recommendations in patients with surgical or transcatheter bioprostheses for bridging during perioperative periods and over the long term. The recommendation for non- vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) was reinforced in patients with native valvular disease, except for significant mitral stenosis, and in those with bioprostheses.

Risk stratification for the timing of intervention. This applies mostly to (i) the evaluation of progression in asymptomatic patients based on recent longitudinal studies mostly in aortic stenosis, and (ii) interventions in high-risk patients in whom futility should be avoided. Regarding this last aspect, the role of frailty is outlined.

- Results and indication of intervention:

- The choice of the mode of intervention: current evidence reinforces the critical role of the Heart Team, which should integrate clinical, anatomical, and procedural characteristics beyond conventional scores, and informed patient’s treatment choice.

- Surgery: increasing experience and procedural safety led to expansion of indications toward earlier intervention in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation or mitral regurgitation and stress the preference for valve repair when it is expected to be durable. A particular emphasis is put on the need for more comprehensive evaluation and earlier surgery in tricuspid regurgitation.

- Transcatheter techniques: (i) Concerning transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), new information from randomized studies comparing TAVI vs. surgery in low-risk patients with a follow-up of 2 years has led to a need to clarify which types of patients should be considered for each mode of intervention. (ii) Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) is increasingly used in SMR and has been evaluated against optimal medical therapy resulting in an upgrade of the recommendation. (iii) The larger number of studies on transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation after failure of surgical bioprostheses served as a basis to upgrade its indication. (iv) Finally, the encouraging preliminary experience with transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions (TTVI) suggests a potential role of this treatment in inoperable patients, although this needs to be confirmed by further evaluation.

The new evidence described above made a revision of the recommendations necessary.

2.2 METHODOLOGY

In preparation of the 2021 VHD Guidelines, a methodology group has been created for the first time, to assist the Task Force for the collection and interpretation of the evidence supporting specific recommendations. The group was constituted of two European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and two European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) delegates who were also members of the Task Force. Although the principle activities of the group concerned the chapter on aortic stenosis and SMR, it was not limited to these two domains. The methodology group was at disposal, upon request of the Task Force members, to resolve specific methodological issues.

2.3 CONTENT OF THESE GUIDELINES

Decision making in VHD involves accurate diagnosis, timing of intervention, risk assessment and, based on these, selection of the most suitable type of intervention. These guidelines focus on acquired VHD, are oriented towards management, and do not deal with endocarditis,4 congenital valve disease5 (including pulmonary valve disease), or recommendations concerning sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease,6 as separate guidelines have been published by the ESC on these topics.

2.4 NEW FORMAT OF THE GUIDELINES

The new guidelines have been adapted to facilitate their use in clinical practice and to meet readers' demands by focusing on condensed, clearly represented recommendations. At the end of the document, key points summarize the essentials. Gaps in evidence are listed to propose topics for future research. The guideline document will be harmonized with the chapter on VHD included in the ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine (ISBN: 9780198784906). The guidelines and the textbook are complementary. Background information and detailed discussion of the data that have provided the basis for the recommendations will be found in the relevant book chapter.

2.5 HOW TO USE THESE GUIDELINES

The Committee emphasizes that many factors ultimately determine the most appropriate treatment in individual patients within a given community. These factors include the availability of diagnostic equipment, the expertise of cardiologists and surgeons, especially in the field of valve repair and percutaneous intervention, and, notably, the wishes of well-informed patients. Furthermore, owing to the lack of evidence-based data in the field of VHD, most recommendations are largely the result of expert consensus opinion. Therefore, deviations from these guidelines may be appropriate in certain clinical circumstances.

3 General comments

This section defines and discusses concepts common to all the types of VHD including the Heart Team and Heart Valve Centres, the main evaluation steps of patients presenting with VHD, as well as the most commonly associated cardiac diseases.

3.1 CONCEPTS OF HEART TEAM AND HEART VALVE CENTRE

The main purpose of Heart Valve Centres as centres of excellence in the treatment of VHD is to deliver optimal quality of care with a patient-centred approach. The main requirements of a Heart Valve Centre are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Requirements for a Heart Valve Centre.

| Requirements |

|---|

| Centre performing heart valve procedures with institutional cardiology and cardiac surgery departments with 24 h/7-day services. |

| Heart Team: clinical cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, imaging specialist with expertise in interventional imaging, cardiovascular anaesthesiologist. |

|

Additional specialists if required: heart failure specialist, electrophysiologist, geriatrician and other specialists (intensive care, vascular surgery, infectious disease, neurology). Dedicated nursing personnel is an important asset to the Heart Team. The Heart Team must meet on a frequent basis and work with standard operating procedures and clinical governance arrangements defined locally. A hybrid catheterization laboratory is desirable. The entire spectrum of surgical and transcatheter valve procedures should be available. High volume for hospital and individual operators. |

| Multimodality imaging including echocardiography, CCT, CMR, and nuclear medicine, as well as expertise on guidance of surgical and interventional procedures. |

| Heart Valve Clinic for outpatient and follow-up management. |

| Data review: continuous evaluation of outcomes with quality review and/or local/external audit. Education programmes targeting patient primary care, operator, diagnostic and interventional imager training and referring cardiologist. |

| CCT: cardiac computed tomography; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance. |

This is achieved through high procedural volume in conjunction with specialized training, continuous education, and focused clinical interest. Heart Valve Centres should promote timely referral of patients with VHD for comprehensive evaluation before irreversible damage occurs.

Decisions concerning treatment and intervention should be made by an active and collaborative Heart Team with expertise in VHD, comprising clinical and interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, imaging specialists with expertise in interventional imaging,7,8 cardiovascular anaesthesiologists, and other specialists if necessary (e.g. heart failure specialists or electrophysiologists). Dedicated nursing personnel with expertise in the care of patients with VHD are also an important asset to the Heart Team. The Heart Team approach is particularly advisable for the management of high-risk and asymptomatic patients, as well as in case of uncertainty or lack of strong evidence.

Heart Valve Clinics are an important component of the Heart Valve Centres, aiming to provide standardized organization of care based on guidelines. Access to Heart Valve Clinics improves outcomes.9

Physicians experienced in the management of VHD and dedicated nurses organize outpatient visits, and referral to the Heart Team, if needed. Earlier referral should be encouraged if patient’s symptoms develop or worsen before the next planned visit.10,11

Beside the whole spectrum of valvular interventions, expertise in interventional and surgical management of coronary artery disease (CAD), vascular diseases, and complications must be available.

Techniques with a steep learning curve may be performed with better results at hospitals with high procedural volume and experience. The relationship between case volume and outcomes for surgery and transcatheter interventions is complex but should not be denied.12,13,14 However, the precise numbers of procedures per individual operator or hospital required to provide high-quality care remain controversial as inequalities exist between high- and middle-income countries.15 High-volume TAVI programmes are associated with lower mortality at 30 days, particularly at hospitals with a high surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) volume.16,17 The data available on transcatheter mitral valve repair14,18 and, even more so, transcatheter tricuspid procedures are more limited.

Since performance does not exclusively relate to intervention volume, internal quality assessment consisting of systematic recording of procedural data and patient outcomes at the level of a given Heart Valve Centre is essential, as well as participation in national or ESC/EACTS registries.

A Heart Valve Centre should have structured and possibly combined training programmes for interventionalists, cardiac surgeons, and imaging specialists13,19,20 (https://ebcts.org/syllabus/). New techniques should be taught by competent mentors to minimize the effects of the learning curve.

Finally, Heart Valve Centres should contribute to optimizing the management of patients with VHD, provide corresponding services at the community level, and promote networks that include other medical departments, referring cardiologists and primary care physicians.

3.2 PATIENT EVALUATION

The aims of the evaluation of patients with VHD are to diagnose, quantify, and assess the mechanism of VHD, as well as its consequences.

3.2.1 CLINICAL EVALUATION

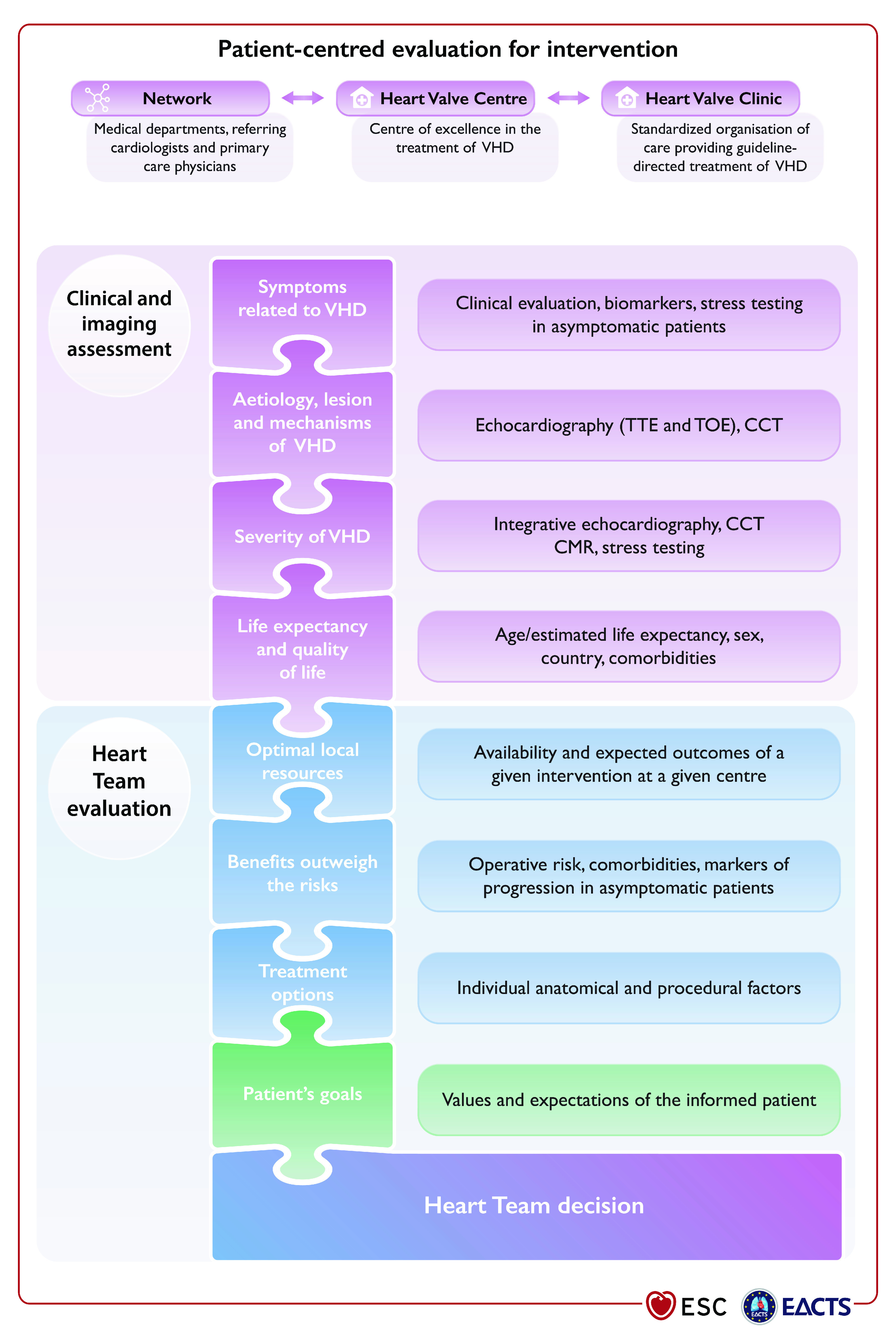

Precise evaluation of the patient's history and symptomatic status, and proper physical examination, in particular auscultation21 and search for heart failure signs, are crucial. In addition, assessment of their comorbidities and general condition require particular attention. The essential questions in the evaluation of a patient for valvular intervention are summarized in Figure 1 (Central illustration).

Figure 1 (Central illustration). Patient-centred evaluation for intervention.

VHD: valvular heart disease; CCT: cardiac computed tomography; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance; TOE: transoesophageal echocardiography; TTE: transthoracic echocardiography.

3.2.2 ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Following adequate clinical evaluation, echocardiography is the key technique used to confirm the diagnosis of VHD, as well as to assess its aetiology, mechanisms, function, severity, and prognosis. It should be performed and interpreted by properly trained imagers.22,23

Echocardiographic criteria for the definition of severe valve stenosis and regurgitation are addressed in specific documents24,25 and summarized in the specific sections of these guidelines. Echocardiography is also key to evaluating the feasibility of a specific intervention.

Indices of left ventricular (LV) enlargement and function are strong prognostic factors. Recent studies suggest that global longitudinal strain has greater prognostic value than LV ejection fraction (LVEF), although cut-off values are not uniform.26,27 Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) should be considered when transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is of suboptimal quality or when thrombosis, prosthetic valve dysfunction, or endocarditis is suspected. TOE is useful when detailed functional valve anatomy is required to assess repairability. Intraprocedural TOE, preferably 3D, is used to guide transcatheter mitral and tricuspid valve procedures and to assess the immediate result of surgical valve operations. Multimodality imaging may be required in specific conditions for evaluation and/or procedural guidance in TAVI and transcatheter mitral interventions.28,29

3.2.3 OTHER NON-INVASIVE INVESTIGATIONS

3.2.3.1 Stress testing

The primary purpose of exercise testing is to unmask the objective occurrence of symptoms in patients who claim to be asymptomatic. It is especially useful for risk stratification in aortic stenosis.30 Exercise testing will also determine the level of recommended physical activity, including participation in sports. It should be emphasized that stress testing is safe and useful in asymptomatic patients with VHD. Unfortunately, the VHD II survey indicates that it is rarely performed in asymptomatic patients.1

Exercise echocardiography may identify the cardiac origin of dyspnoea. Prognostic impact has been shown mainly for aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation.31,32

The use of stress tests to detect CAD associated with severe valvular disease is discouraged because of their low diagnostic value and potential risks in symptomatic patients with aortic stenosis.

3.2.3.2 Cardiac magnetic resonance

In patients with inadequate echocardiographic quality or discrepant results, CMR should be used to assess the severity of valvular lesions, particularly regurgitant lesions, and to assess ventricular volumes, systolic function, abnormalities of the ascending aorta, and myocardial fibrosis.33 CMR is the reference method for the evaluation of right ventricular (RV) volumes and function and is therefore particularly useful to evaluate the consequences of tricuspid regurgitation.34 It also has an incremental value for assessing the severity of aortic and mitral regurgitation.

3.2.3.3 Computed tomography

CCT may contribute to the evaluation of valve disease severity, particularly in aortic stenosis35,36 and possibly associated disease of the thoracic aorta (dilatation, calcification), as well as to evaluate the extent of MAC. CCT should be performed whenever the echocardiographic data indicate an aortic enlargement >40 mm, to clarify aortic diameter and to assess aortic morphology and configuration. CCT is essential in the pre-procedural planning of TAVI and can also be useful to assess patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM).37 It is also a prerequisite for pre-procedural planning of mitral and tricuspid valve interventions.38 Positron emission tomography (PET)/CCT is useful in patients with a suspicion of endocarditis of a prosthetic valve.39,40

3.2.3.4 Cinefluoroscopy

Cinefluoroscopy is particularly useful for assessing the kinetics of the leaflet occluders of a mechanical prosthesis.

3.2.3.5 Biomarkers

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) serum levels, corrected for age and sex, are useful in asymptomatic patients and may assist selection of the appropriate time point for a given intervention,41 particularly if the level rises during follow-up. Other biomarkers have been tested, with evidence for fibrosis, inflammation, and adverse ventricular remodelling, which could improve decision making.42

3.2.3.6 Multimarkers and staging

In patients with at least moderate aortic stenosis and LVEF >50%, staging according to damage associated with aortic stenosis on LV/RV, left atrium (LA), mitral /tricuspid valve, and pulmonary circulation was predictive of excess mortality after TAVI and SAVR, and may help to identify patients who will benefit from an intervention.43,44

3.2.4 INVASIVE INVESTIGATIONS

3.2.4.1 Coronary angiography

Coronary angiography is recommended for the assessment of CAD when surgery or an intervention is planned, to determine if concomitant coronary revascularization is recommended (see recommendations for management of CAD in patients with VHD, Recommendations A).45,46 Alternatively, owing to its high negative predictive value, CCT may be used to rule out CAD in patients who are at low risk of atherosclerosis. The usefulness of fractional flow reserve or instantaneous wave-free ratio in patients with VHD is not well established, and caution is warranted in the interpretation of these measurements when VHD, and in particular aortic stenosis, is present.47,48

Recommendations A. Recommendations for management of CAD in patients with VHD.

| Recommendations | Classa | Levelb |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis of CAD | ||

| Coronary angiography is recommended before valve surgery in patients with severe VHD and any of the following: • History of cardiovascular disease. • Suspected myocardial ischaemia.c • LV systolic dysfunction. • In men >40 years of age and postmenopausal women. • One or more cardiovascular risk factors. |

I | C |

| Coronary angiography is recommended in the evaluation of severe SMR. | I | C |

| Coronary CT angiography should be considered as an alternative to coronary angiography before valve surgery in patients with severe VHD and low probability of CAD.d | IIa | C |

| Indications for myocardial revascularization | ||

| CABG is recommended in patients with a primary indication for aortic/mitral/tricuspid valve surgery and coronary artery diameter stenosis ≥70%.e,f | I | C |

| CABG should be considered in patients with a primary indication for aortic/mitral/tricuspid valve surgery and coronary artery diameter stenosis ≥50-70%. | IIa | C |

| PCI should be considered in patients with a primary indication to undergo TAVI and coronary artery diameter stenosis >70% in proximal segments. | IIa | C |

| PCI should be considered in patients with a primary indication to undergo transcatheter mitral valve intervention and coronary artery diameter stenosis >70% in proximal segments. | IIa | C |

| CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CT: computed tomography; LV: left ventricle/left ventricular; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SMR: secondary mitral regurgitation; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; VHD: valvular heart disease. aClass of recommendation. bLevel of evidence. cChest pain, abnormal non-invasive testing. dCoronary CT angiography may also be used in patients requiring emergency surgery with acute infective endocarditis with large vegetations protruding in front of a coronary ostium. eStenosis ≥50% can be considered for left main stenosis. fFFR ≤0.8 is a useful cut-off indicating the need for an intervention in patients with mitral or tricuspid diseases, but has not been validated in patients with aortic stenosis. Adapted from 45,72 | ||

3.2.4.2 Cardiac catheterization

The measurement of pressures and cardiac output or the assessment of ventricular performance and valvular regurgitation by ventricular angiography or aortography is restricted to situations where non-invasive evaluation by multimodality imaging is inconclusive or discordant with clinical findings. When elevated, pulmonary pressure is the only criterion to support the indication for surgery, and confirmation of echo data by invasive measurement is recommended. Right heart catheterization is also indicated in patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation as Doppler gradient may be impossible or underestimate the severity of pulmonary hypertension.

3.2.5 ASSESSMENT OF COMORBIDITY

The choice of specific examinations to assess comorbidity is guided by the clinical evaluation.

3.3 RISK STRATIFICATION

Risk stratification applies to any sort of intervention and is required for weighing the risk of intervention against the expected natural history of VHD and for choosing the type of intervention. Most experience relates to surgery and TAVI.

3.3.1 RISK SCORES

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) predicted risk of mortality (PROM) score (http://riskcalc.sts.org/stswebriskcalc/calculate) and the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II; http://www.euroscore.org/calc.html) accurately discriminate high- and low-risk surgical patients and show good calibration to predict postoperative outcome after valvular surgery in the majority of the patients,49,50 while risk estimation may be less accurate in high-risk patients.51 The STS-PROM score is dynamic and changes over time. Of note, the risk scores have not been validated for isolated tricuspid surgical interventions.

In isolation, surgical scores have major limitations for practical use in patients undergoing transcatheter intervention because they do not include major risk factors such as frailty, as well as anatomical factors with impact on the procedure, either surgical or transcatheter [porcelain aorta, previous chest radiation, mitral annular calcification (MAC)].

New scores have been developed to estimate the risk in patients undergoing TAVI, with better accuracy and discrimination than the surgical risk scores, despite numerous limitations52,53,54 (Supplementary Table 1).

Experience with risk stratification is currently limited for other interventional procedures, such as mitral or tricuspid interventions.

3.3.2 OTHER FACTORS

Other factors should be taken into account:

• Frailty, defined as a decrease of physiologic reserve and ability to maintain homeostasis leading to an increased vulnerability to stresses and conferring an increased risk of morbidity and mortality after both surgery and TAVI.55 The assessment of frailty should not rely on a subjective approach, such as the ‘eyeball test’, but rather on a combination of different objective estimates.55,56,57,58,59 Several tools are available for assessing frailty (Supplementary Table 2,59 and Supplementary Table 3).60

• Malnutrition61 and cognitive dysfunction62 both predict poor prognosis.

• Other major organ failures (Supplementary Table 4), in particular the combination of severe lung disease,63,64 postoperative pain from sternotomy or thoracotomy and prolonged time under anaesthesia in patients undergoing SAVR via full sternotomy, may contribute to pulmonary complications. There is a positive association between the impairment of renal function and increased mortality after valvular surgery and transcatheter procedures,65 especially when the glomerular filtration rate is <30 mL/min. Liver disease, is also an important prognostic factor.66

• Anatomical aspects affecting procedural performance such as porcelain aorta or severe MAC67 (see Table 6 in section 5.1.3, and Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 6. Clinical, anatomical and procedural factors that influence the choice of treatment modality for an individual patient.

| Favours TAVI | Favours SAVR | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Lower surgical risk | − | + |

| Higher surgical risk | + | − |

| Younger agea | − | + |

| Older agea | + | − |

| Previous cardiac surgery (particularly intact coronary artery bypass grafts at risk of injury during repeat sternotomy) | + | − |

| Severe frailtyb | + | − |

| Active or suspected endocarditis | − | + |

| Anatomical and procedural factors | ||

| TAVI feasible via transfemoral approach | + | − |

| Transfemoral access challenging or impossible and SAVR feasible | − | + |

| Transfemoral access challenging or impossible and SAVR inadvisable | +c | − |

| Sequelae of chest radiation | + | − |

| Porcelain aorta | + | − |

| High likelihood of severe patient-prosthesis mismatch (AVA <0.65 cm2/m2 BSA) | + | − |

| Severe chest deformation or scoliosis | + | − |

| Aortic annular dimensions unsuitable for available TAVI devices | − | + |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | − | + |

| Valve morphology unfavourable for TAVI (e.g. high risk of coronary obstruction due to low coronary ostia or heavy leaflet/LVOT calcification) | − | + |

| Thrombus in aorta or LV | − | + |

| Concomitant cardiac conditions requiring intervention | ||

| Significant multi-vessel CAD requiring surgical revascularizationd | − | + |

| Severe primary mitral valve disease | − | + |

| Severe tricuspid valve disease | − | + |

| Significant dilatation/aneurysm of the aortic root and/or ascending aorta | − | + |

| Septal hypertrophy requiring myectomy | − | + |

| AVA: aortic valve area, BSA: body surface area, CAD: coronary artery disease; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; LV: left ventricle/left ventricular; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Integration of these factors provides guidance for the Heart Team decision (indications for intervention are provided in the table of recommendations on indications for intervention in symptomatic and asymptomatic aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention). aLife expectancy is highly dependent on absolute age and frailty, differs between men and women, and may be a better guide than age alone. There is wide variation across Europe and elsewhere in the world (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2017-life-tables-1950-2017). bSevere frailty: >2 factors according to Katz index59 (see section 3.3 for further discussion). cVia non-transfemoral approach. d According to the 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. | ||

At the extreme of the risk spectrum, futility should be avoided. Therapeutic futility has been defined as a lack of medical efficacy, particularly when the physician judges that the therapy is unlikely to produce its intended clinical results, or lack of meaningful survival according to the personal values of the patient. Assessment of futility goes beyond survival and includes functional recovery. The futility of interventions has to be taken into consideration, particularly for transcatheter interventions.63

The high prevalence of comorbidity in the elderly makes assessment of the risk/benefit ratios of interventions more difficult, therefore the role of the Heart Team is essential in this specific population of patients (Supplementary Table 5).

3.4 PATIENT-RELATED ASPECTS

Patient-related life expectancy and expected quality of life should be considered. The patient and their family should be thoroughly informed and assisted in their decision on the best treatment option.13 A patient-centred approach would take patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures into consideration and make these parameters part of the informed choice offered to patients.68,69

When benefit in symptom relief aligns with a patient’s goals, care is not futile. However, care is futile when no life prolongation or symptom relief is anticipated.70

3.5 LOCAL RESOURCES

Even if it is desirable that Heart Valve Centres are able to perform a large spectrum of procedures, either surgical or catheter-based, specialization and thereby expertise in specific domains will vary and should be taken into account when deciding on the orientation of the patient in specific cases, such as complex surgical valve repair or transcatheter intervention.

In addition, penetration of transcatheter interventions is heterogeneous worldwide and highly dependent on socioeconomic inequalities.15,71 Appropriate stewardship of economic resources is a fundamental responsibility of the Heart Team.

3.6 MANAGEMENT OF ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

3.6.1 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Recommendations for the management of CAD associated with VHD are provided below and are detailed in specific sections (section 5 and section 6.2) of this guideline document, as well as in other dedicated guideline documents.45,46,72,73

3.6.2 ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

Detailed recommendations on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) including management of anticoagulation are provided in specific guidelines.74 NOACs are recommended in patients with aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation or mitral regurgitation presenting with AF75,76,77,78 as subgroup analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the use of apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban. The use of NOACs is not recommended in patients who have AF associated with clinically significant mitral stenosis or those with mechanical prostheses.

Surgical ablation of AF combined with mitral valve surgery effectively reduces the incidence of AF but has no impact on adjusted short-term survival. An increased rate of pacemaker implantation has been observed after surgical ablation (9.5%, vs. 7.6% in the group with AF and no surgical ablation).79 Concomitant AF ablation should be considered in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, balancing the benefits of freedom from atrial arrhythmias with the risk factors for recurrence, such as age, LA dilatation, years in AF, renal dysfunction, and other cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion should be considered in combination with valve surgery in patients with AF and a CHA2DS2VASc score ≥2 to reduce the thromboembolic risk.80,81,82 The selected surgical technique should ensure complete occlusion of the LAA. For patients with AF and risk factors for stroke, long-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) is currently recommended, irrespective of the use of surgical ablation of AF and/or surgical LAA occlusion.

Recommendations for the management of AF in native VHD are summarized in the following table (Recommendations B). The recommendations concerning patients with valve prostheses, and the combination of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents in patients undergoing PCI, are described in section 11 (section 11.3.2.2 and related table of recommendations for perioperative and postoperative antithrombotic management of valve replacement or repair).

Recommendations B. Recommendations on management of atrial fibrillation in patients with native VHD.

| Recommendations | Classa | Levelb |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulation | ||

| For stroke prevention in AF patients who are eligible for OAC, NOACs are recommended in preference to VKAs in patients with aortic stenosis, aortic and mitral regurgitation. 75,76,77,78,83,84 | I | A |

| The use of NOACs is not recommended in patients with AF and moderate to severe mitral stenosis. | III | C |

| Surgical interventions | ||

| Concomitant AF ablation should be considered in patients undergoing valve surgery, balancing the benefits of freedom from atrial arrhythmias and the risk factors for recurrence (LA dilatation, years in AF, age, renal dysfunction, and other cardiovascular risk factors). 79,85,86,87,88,89,90 | IIa | A |

| LAA occlusion should be considered to reduce the thromboembolic risk in patients, with AF and a CHA2DS2VASc score ≥2 undergoing valve surgery. 82 | IIa | B |

| AF: atrial fibrillation; LA: left atrium/left atrial; LAA: left atrial appendage; NOAC: non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; OAC: oral anticoagulation; VKA: vitamin K antagonist. aClass of recommendation. bLevel of evidence. | ||

3.7 ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for high-risk procedures in patients with prosthetic valves, including transcatheter valves, or with repairs using prosthetic material, and in patients with previous episode(s) of infective endocarditis.4 Particular attention to dental and cutaneous hygiene and strict aseptic measures during any invasive procedure are advised in this population. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered in dental procedures involving manipulation of the gingival or periapical region of the teeth or manipulation of the oral mucosa.4

3.8 PROPHYLAXIS FOR RHEUMATIC FEVER

Prevention of rheumatic heart disease should preferably target the first attack of acute rheumatic fever. Antibiotic treatment of group A Streptococcus infection throat is key in primary prevention. Echocardiographic screening in combination with secondary antibiotic prophylaxis in children with evidence of latent rheumatic heart disease is currently investigated to reduce its prevalence in endemic regions.91 In patients with established rheumatic heart disease, secondary long-term prophylaxis against rheumatic fever is recommended: benzathine benzyl penicillin 1.2 MUI every 3 to 4 weeks over 10 years. Lifelong prophylaxis should be considered in high-risk patients according to the severity of VHD and exposure to group A Streptococcus.92,93,94,95

4 Aortic regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation can be caused by primary disease of the aortic valve cusps and/or abnormalities of the aortic root and ascending aortic geometry. Degenerative tricuspid and bicuspid aortic regurgitation are the most common aetiologies in high-income countries, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the underlying aetiology of aortic regurgitation in the EURObservational Registry Programme Valvular Heart Disease II registry.1 Other causes include infective and rheumatic endocarditis. Acute severe aortic regurgitation is mostly caused by infective endocarditis, and less frequently by aortic dissection.

4.1 EVALUATION

4.1.1 ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Echocardiography is the key examination used to describe valve anatomy, quantify aortic regurgitation, evaluate its mechanisms, define the morphology of the aorta, and determine the feasibility of valve-sparing aortic surgery or valve repair.96,97 Identification of the mechanism follows the same principle such as for mitral regurgitation: normal cusps but insufficient coaptation due to dilatation of the aortic root with central jet (type 1), cusp prolapse with eccentric jet (type 2), or retraction with poor cusp tissue quality and large central or eccentric jet (type 3).96 Quantification of aortic regurgitation follows an integrated approach considering qualitative, semi-quantitative, and quantitative parameters24,98 (Table 5). New parameters obtained by 3D echocardiography and two-dimensional (2D) strain imaging as LV global longitudinal strain may be useful, particularly in patients with borderline LVEF where they may help in the decision for surgery.99 Measurement of the aortic root and ascending aorta in 2D is performed at four levels: annulus, sinuses of Valsalva, sinotubular junction, and tubular ascending aorta.100,101 Measurements are performed in the parasternal long-axis view from leading edge to leading edge at end diastole, except for the aortic annulus, which is measured in mid systole. As it will have surgical consequences, it is important to differentiate three phenotypes of the ascending aorta: aortic root aneurysms (sinuses of Valsalva >45 mm), tubular ascending aneurysm (sinuses of Valsalva <40-45 mm), and isolated aortic regurgitation (all aortic diameters <40 mm). The calculation of indexed values to account for body size has been suggested,102 in particular in patients with small stature. Anatomy of the aortic valve cusps and its suitability for valve repair should be provided by preoperative TOE if aortic valve repair or a valve-sparing surgery of the aortic root is considered. Intraoperative evaluation of the surgical result by TOE is mandatory in patients undergoing aortic valve preservation or repair.

Table 5. Echocardiographic criteria for the definition of severe aortic valve regurgitation.

| Qualitative | |

|---|---|

| Valve morphology | Abnormal/flail/large coaptation defect |

| Colour flow regurgitant jet areaa | Large in central jets, variable in eccentric jets |

| CW signal of regurgitant jet | Dense |

| Other | Holodiastolic flow reversal in descending aorta (EDV >20 cm/s) |

| Semiquantitative | |

| Vena contracta width (mm) | >6 |

| Pressure half-timeb (ms) | <200 |

| Quantitative | |

| EROA (mm2) | ≥30 |

| Regurgitant volume (mL/beat) | ≥60 |

| Enlargement of cardiac chambers | LV dilatation |

| CW: continuous wave; EDV: end-diastolic velocity; EROA: effective regurgitant orifice area; LV: left ventricle/left ventricular. aAt a Nyquist limit of 50-60 cm/s. bPressure half-time is shortened with increasing LV diastolic pressure, vasodilator therapy, and in patients with a dilated compliant aorta, or lengthened in chronic aortic regurgitation. Adapted from Lancellotti P et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14:611-644. Copyright (2013) by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. | |

4.1.2 COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY AND CARDIAC MAGNETIC RESONANCE

CMR should be used to quantify the regurgitant fraction when echocardiographic measurements are equivocal or discordant with clinical findings. In patients with aortic dilatation, CCT is recommended to assess the maximum diameter at four levels, as in echocardiography. CMR can be used for follow-up, but indication for surgery should preferably be based on CCT measurements. Different methods of aortic measurements have been reported. To improve reproducibility, it is recommended to measure diameters using the inner-inner-edge technique at end diastole on the strictly transverse plane by double oblique reconstruction perpendicular to the axis of blood flow of the corresponding segment. Maximum root diameter should be taken from sinus-to-sinus diameter rather than sinus-to-commissure diameter, as it correlates more closely to long-axis leading-edge-to-leading-edge echo maximum diameters.103,104

4.2 INDICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

Acute aortic regurgitation may require urgent surgery. It is mainly caused by infective endocarditis and aortic dissection but may also occur after blunt chest trauma and iatrogenic complications during catheter-based cardiac interventions. Specific guidelines deal with these entities.4,101 The recommendations on indications for surgery in severe aortic regurgitation and aortic root disease may be related to symptoms, status of the LV, or dilatation of the aorta [see table of recommendations on indications for surgery in severe aortic regurgitation and aortic root or tubular ascending aortic aneurysm (irrespective of the severity of aortic regurgitation), and Figure 2].

Figure 2. Management of patients with aortic regurgitation.

BSA: body surface area; LV: left ventricle/left ventricular; LVESD: left ventricle end-systolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. aSee recommendations on indications for surgery in severe aortic regurgitation and aortic root disease for definition. bSurgery should also be considered if significant changes in LV or aortic size occur during follow-up.

In symptomatic patients, surgery is recommended irrespective of the LVEF as long as aortic regurgitation is severe and the operative risk is not prohibitive.105,106,107,108,109 Surgery is recommended in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or surgery of the ascending aorta or another valve.110,111 In asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation, impairment of LV function [LVEF ≤50% or left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) >50 mm] are associated with worse outcomes and surgery should therefore be pursued when these cut-offs are reached.107,108,112,113,114 LVESD should be related to body surface area (BSA) and a cut-off of 25 mm/m2 BSA appeared to be more appropriate, especially in patients with small body size (BSA <1.68 m2) or with large BSA who are not overweight.108,115 Some recent retrospective, non-randomized studies emphasized the role of indexed LVESD and proposed a lower cut-off value of 20 or 22 mm/m² BSA for the indexed LVESD.116,117,118 One of these studies also suggests a higher cut-off value of 55% for LVEF.118 Based on these data, low-risk surgery may be discussed in some selected asymptomatic patients with LVESD >20 mm/m2 or resting LVEF between 50% and 55%. In patients not reaching the thresholds for surgery, close follow-up is needed, and exercise testing should be liberally performed to identify borderline symptomatic patients. Progressive enlargement of the LV, or a progressive decrease in its function in asymptomatic patients not reaching the thresholds for surgery but with significant LV dilatation [left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) >65 mm], may also be an appropriate indicator for timing operations in asymptomatic patients.

TAVI may be considered in experienced centres for selected patients with aortic regurgitation and ineligible for SAVR.119,120

In patients with a dilated aorta, the rationale for surgery has been best defined in patients with Marfan syndrome and root dilation.121,122 Root aneurysms require root replacement, with or without preservation of the native aortic valve. In contrast, tubular ascending aortic aneurysms in the presence of normal aortic valves require only a supracommissural tube graft replacement. In patients with aortic diameters borderline indicated for aortic surgery, the family history, age, and anticipated risk of the procedure should be taken into consideration. Irrespective of the degree of aortic regurgitation and type of valve pathology, in patients with an aortic diameter ≥55 mm with tricuspid or bicuspid aortic valves, ascending aortic surgery is recommended (see recommendations on indications for surgery in severe aortic regurgitation and aortic root disease, Recommendations C) when the operative risk is not prohibitive.123,124,125 In individuals with bicuspid aortic valve, when additional risk factors or coarctation126 are present, surgery should be considered when aortic diameter is ≥50 mm.127,128,129 In all patients with Marfan syndrome, aortic surgery is recommended for a maximal aortic diameter ≥50 mm.5,121,122 When additional risk factors are present in patients with Marfan syndrome and in patients with a TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 mutation (including Loeys-Dietz syndrome), surgery should be considered at a maximal aortic diameter ≥45 mm121,130 and even earlier (aortic diameter of 40 mm or more) in women with low BSA, patients with a TGFBR2 mutation, or patients with severe extra-aortic features that appear to be at particularly high risk.130 For patients who have an indication for aortic valve surgery, an aortic diameter ≥45 mm is considered to indicate concomitant surgery of the aortic root or tubular ascending aorta. The patient's stature, the aetiology of the valvular disease (bicuspid valve), and the intraoperative shape and wall thickness of the ascending aorta should be considered for individual decisions.

Recommendations C. Recommendations on indications for surgery in (A) severe aortic regurgitation and (B) aortic root or tubular ascending aortic aneurysm (irrespective of the severity of aortic regurgitation).

| Indications for surgery | Classa | Levelb |

|---|---|---|

| A) Severe aortic regurgitation | ||

| Surgery is recommended in symptomatic patients regardless of LV function. 105,106,107,108,109 | I | B |

| Surgery is recommended in asymptomatic patients with LVESD >50mm or LVESD >25 mm/m2 BSA (in patients with small body size) or resting LVEF ≤50%. 107,108,112,114,115 | I | B |

| Surgery may be considered in asymptomatic patients with LVESD >20 mm/m2 BSA (especially in patients with small body size) or resting LVEF ≤55%, if surgery is at low risk. | IIb | C |

| Surgery is recommended in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation undergoing CABG or surgery of the ascending aorta or of another valve. | I | C |

| Aortic valve repair may be considered in selected patients at experienced centres when durable results are expected. | IIb | C |

| B) Aortic root or tubular ascending aortic aneurysmc (irrespective of the severity of aortic regurgitation) | ||

| Valve-sparing aortic root replacement is recommended in young patients with aortic root dilation, if performed in experienced centres and durable results are expected. 133,134,135,136,140 | I | B |

| Ascending aortic surgery is recommended in patients with Marfan syndrome who have aortic root disease with a maximal ascending aortic diameter ≥50 mm. | I | C |

| Ascending aortic surgery should be considered in patients who have aortic root disease with maximal ascending aortic diameter: • ≥55 mm in all patients. • ≥45 mm in the presence of Marfan syndrome and additional risk factorsd or patients with a TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 mutation (including Loeys-Dietz syndrome).e • ≥50 mm in the presence of a bicuspid valve with additional risk factorsd or coarctation. |

IIa | C |

| When surgery is primarily indicated for the aortic valve, replacement of the aortic root or tubular ascending aorta should be considered when ≥45 mm.f | IIa | C |

The choice of the surgical procedure should be adapted according to the experience of the team, the presence of an aortic root aneurysm, characteristics of the cusps, life expectancy, and desired anticoagulation status.

Valve replacement is the standard procedure in the majority of patients with aortic regurgitation. Aortic valve-sparing root replacement and valve repair yield good long-term results in selected patients, with low rates of valve-related events as well as good quality of life131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140 when performed in experienced centres. Aortic valve-sparing root replacement is recommended in younger patients who have an enlargement of the aortic root with normal cusp motion, when performed by experienced surgeons.133,134,135,136,140 In selected patients, aortic valve repair132,137 or the Ross procedure138,139 may be an alternative to valve replacement, when performed by experienced surgeons.

4.3 MEDICAL THERAPY

Medical therapy, especially angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or dihydropiridines, may provide symptomatic improvement in individuals with chronic severe aortic regurgitation in whom surgery is not feasible. The value of ACEI or dihydropiridine in delaying surgery in the presence of moderate or severe aortic regurgitation in asymptomatic patients has not been established and their use is not recommended for this indication.

In patients who undergo surgery but continue to suffer from heart failure or hypertension, ACEI, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta-blockers are useful.141,142

In patients with Marfan syndrome, beta-blockers remain the mainstay for medical treatment and reducing shear stress and aortic growth rate and should be considered before and after surgery.143,144,145 While ARBs did not prove to have a superior effect when compared to beta-blockers, they may be considered as an alternative in patients intolerant to beta-blockers.146,147,148 By analogy, while there are no studies that provide supporting evidence, it is common clinical practice to advise beta-blocker or ARBs in patients with bicuspid aortic valve if the aortic root and/or ascending aorta is dilated. Management of aortic regurgitation during pregnancy is discussed in section 13.

4.4 SERIAL TESTING

All asymptomatic patients with severe aortic regurgitation and normal LV function should be followed up at least every year. In patients with either a first diagnosis or with LV diameter and/or ejection fraction showing significant changes or approaching thresholds for surgery, follow-up should be continued at 3-6-month intervals. Surgery may be considered in asymptomatic patients with significant LV dilatation (LVEDD >65 mm), and with progressive enlargement in the size of LV or progressive decrease of LVEF during follow-up. Patient’s BNP levels could be of potential interest as a predictor of outcomes (particularly symptom onset and deterioration of LV function) and may be helpful in the follow-up of asymptomatic patients.149 Patients with mild-to-moderate aortic regurgitation can be seen on a yearly basis and echocardiography performed every 2 years.

If the ascending aorta is dilated (>40 mm), it is recommended to systematically perform CCT or CMR. Follow-up assessment of the aortic dimension should be performed using echocardiography and/or CMR. Any increase >3 mm should be validated by CCT angiography/CMR and compared with baseline data. After repair of the ascending aorta, Marfan patients remain at risk for dissection of the residual aorta and lifelong regular multidisciplinary follow-up at an expert centre is required.

4.5 SPECIAL PATIENT POPULATIONS

If aortic regurgitation requiring surgery is associated with severe primary and secondary mitral regurgitation, both should be treated during the same operation.

In patients with moderate aortic regurgitation who undergo CABG or mitral valve surgery, the decision to treat the aortic valve is controversial, as data show that progression of moderate aortic regurgitation is very slow in patients without aortic dilation.150 The Heart Team should decide based on the aetiology of aortic regurgitation, other clinical factors, the life expectancy of the patient, and the patient's operative risk.

The level of physical and sports activity in the presence of a dilated aorta remains a matter of clinical judgment in the absence of evidence. Current guidelines are very restrictive, particularly regarding isometric exercise, to avoid a catastrophic event.151 This approach is justified in the presence of connective tissue disease, but a more liberal approach is likely to be appropriate in other patients.

Given the familial risk of thoracic aortic aneurysms, screening and referral for genetic testing of the patient's first-degree relatives with appropriate imaging studies is indicated in patients with connective tissue disease. For patients with bicuspid valves, it is appropriate to have an echocardiographic screening of first-degree relatives.

5 Aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis is the most common primary valve lesion requiring surgery or transcatheter intervention in Europe1 and North America. Its prevalence is rising rapidly as a consequence of the ageing population.2,152

5.1 EVALUATION

5.1.1 ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Echocardiography is key to confirming the diagnosis and severity of aortic stenosis, assessing valve calcification, LV function and wall thickness, detecting other valve disease or aortic pathology, and providing prognostic information.43,153,154 Assessment should be undertaken when blood pressure (BP) is well controlled to avoid the confounding flow effects of increased afterload. New echocardiographic parameters, stress imaging and CCT provide important adjunctive information when severity is uncertain (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Integrated imaging assessment of aortic stenosis.

AS: aortic stenosis; AV: aortic valve; AVA: aortic valve area; CT: computed tomography; ΔPm: mean pressure gradient; DSE: dobutamine stress echocardiography; LV: left ventricle/left ventricular; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SVi: stroke volume index; Vmax: peak transvalvular velocity. aHigh flow may be reversible in patients with anaemia, hyperthyroidism or arterio-venous fistulae, and may also be present in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Upper limit of normal flow using pulsed Doppler echocardiography: cardiac index 4.1 L/min/m2 in men and women, SVi 54 mL/m2 in men, 51 mL/m2 in women).155 bConsider also: typical symptoms (with no other explanation), LV hypertrophy (in the absence of coexistent hypertension) or reduced LV longitudinal function (with no other cause). cDSE flow reserve: >20% increase in stroke volume in response to low-dose dobutamine. dPseudo-severe aortic stenosis: AVA >1.0 cm2 with increased flow. eThresholds for severe aortic stenosis assessed by means of CT measurement of aortic valve calcification (Agatston units): men >3000, women >1600: highly likely; men >2000, women >1200: likely; men <1600, women <800: unlikely.

Current international recommendations for the echocardiographic evaluation of patients with aortic stenosis25 depend upon measurement of mean pressure gradient (the most robust parameter), peak transvalvular velocity (Vmax), and valve area. Although valve area is the theoretically ideal measurement for assessing severity, there are numerous technical limitations. Clinical decision making in discordant cases should therefore take account of additional parameters: functional status, stroke volume, Doppler velocity index,156 degree of valve calcification, LV function, the presence or absence of LV hypertrophy, flow conditions, and the adequacy of BP control.25 Low flow is arbitrarily defined by a stroke volume index (SVi) ≤35 mL/m² –a threshold that is under current debate.155,157,158 The use of sex -specific thresholds has been recently proposed.159 Four broad categories can be defined:

High-gradient aortic stenosis [mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak velocity ≥4.0 m/s, valve area ≤1 cm2 (or ≤0.6 cm²/m²)]. Severe aortic stenosis can be assumed irrespective of LV function and flow conditions.

Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis with reduced ejection fraction (mean gradient <40 mmHg, valve area ≤1 cm2, LVEF <50%, SVi ≤35 mL/m2). Low-dose dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) is recommended to distinguish between true severe and pseudo-severe aortic stenosis (increase in valve area to >1.0 cm2 with increased flow) and identify patients with no flow (or contractile) reserve.160 However, utility in elderly patients has only been evaluated in small registries.161

Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction (mean gradient <40 mmHg, valve area ≤1 cm2, LVEF ≥50%, SVi ≤35 mL/m2). Typically encountered in hypertensive elderly subjects with small LV size and marked hypertrophy.157,162 This scenario may also result from conditions associated with low stroke volume (e.g. moderate/severe mitral regurgitation, severe tricuspid regurgitation, severe mitral stenosis, and large ventricular septal defect and severe RV dysfunction). Diagnosis of severe aortic stenosis is challenging and requires careful exclusion of measurement errors and other explanations for the echocardiographic findings,25 as well as the presence or absence of typical symptoms (with no other explanation), LV hypertrophy (in the absence of coexistent hypertension) or reduced LV longitudinal strain (with no other cause). CCT assessment of the degree of valve calcification provides important additional information [thresholds (Agatston units) for severe aortic stenosis: men >3000, women >1600 = highly likely; men >2000, women >1200 = likely; men <1600, women <800 = unlikely].35,36,163,164

Normal-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction (mean gradient <40 mmHg, valve area ≤1 cm2, LVEF≥50%, SVi >35 mL/m2). These patients usually have only moderate aortic stenosis.36,165,166,167

5.1.2 ADDITIONAL DIAGNOSTIC AND PROGNOSTIC PARAMETERS

The resting Doppler velocity index (DVI, also termed ‘dimensionless index’) –the ratio of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) time-velocity integral (TVI) to that of the aortic valve jet– does not require calculation of LVOT area and may assist evaluation when other parameters are equivocal (a value <0.25 suggests that severe aortic stenosis is highly likely).156 Assessment of global longitudinal strain provides additional information concerning LV function and a threshold of 15% may help to identify patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis who are at higher risk of clinical deterioration or premature mortality.26,168 TOE allows evaluation of concomitant mitral valve disease and may be of value for periprocedural imaging during TAVI and SAVR.169

Natriuretic peptides predict symptom-free survival and outcome in normal and low-flow severe aortic stenosis.170,171 They can be used to arbitrate the source of symptoms in patients with multiple potential causes and identify those with high-risk asymptomatic aortic stenosis who may benefit from early intervention (section 5.2.2, Table 6 and Figure 3).

Exercise testing may unmask symptoms and is recommended for risk stratification of asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis.172 Exercise echocardiography provides additional prognostic information by assessing the increase in mean pressure gradient and change in LV function.173

CCT provides information concerning the anatomy of the aortic root and ascending aorta, and the extent and distribution of valve and vascular calcification, and feasibility of vascular access.174 Quantification of valve calcification predicts disease progression and clinical events164 and may be useful when combined with geometric assessment of valve area in assessing the severity of aortic stenosis in patients with low valve gradient.35,36,163,164

Myocardial fibrosis is a major driver of LV decompensation in aortic stenosis (regardless of the presence or absence of CAD), which can be detected and quantified using CMR. Amyloidosis is also frequently associated with aortic stenosis in elderly patients (incidence 9-15%).175 When cardiac amyloidosis is clinically suspected, based on symptoms (neuropathy and hematologic data), diphosphonate scintigraphy and/or CMR should be considered. Both entities persist following valve intervention and are associated with poor long-term prognosis.176,177,178,179

Coronary angiography is essential prior to TAVI and SAVR to determine the potential need for concomitant revascularization (see section 3.2.4.1 and section 5.5). Retrograde LV catheterization is not recommended unless there are symptoms and signs of severe aortic stenosis and non-invasive investigations are inconclusive.

5.1.3 TAVI DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

Prior to TAVI, CCT is the preferred imaging tool to assess: (i) aortic valve anatomy, (ii) annular size and shape, (iii) extent and distribution of valve and vascular calcification, (iv) risk of coronary ostial obstruction, (v) aortic root dimensions, (vi) optimal fluoroscopic projections for valve deployment, and (vii) feasibility of vascular access (femoral, subclavian, axillary, carotid, transcaval or transapical). Adverse anatomical findings may suggest that SAVR is a better treatment option (Table 6). TOE is more operator-dependent but may be considered when CCT is difficult to interpret or relatively contraindicated (e.g. chronic renal failure).

5.2 INDICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION (SAVR OR TAVI)

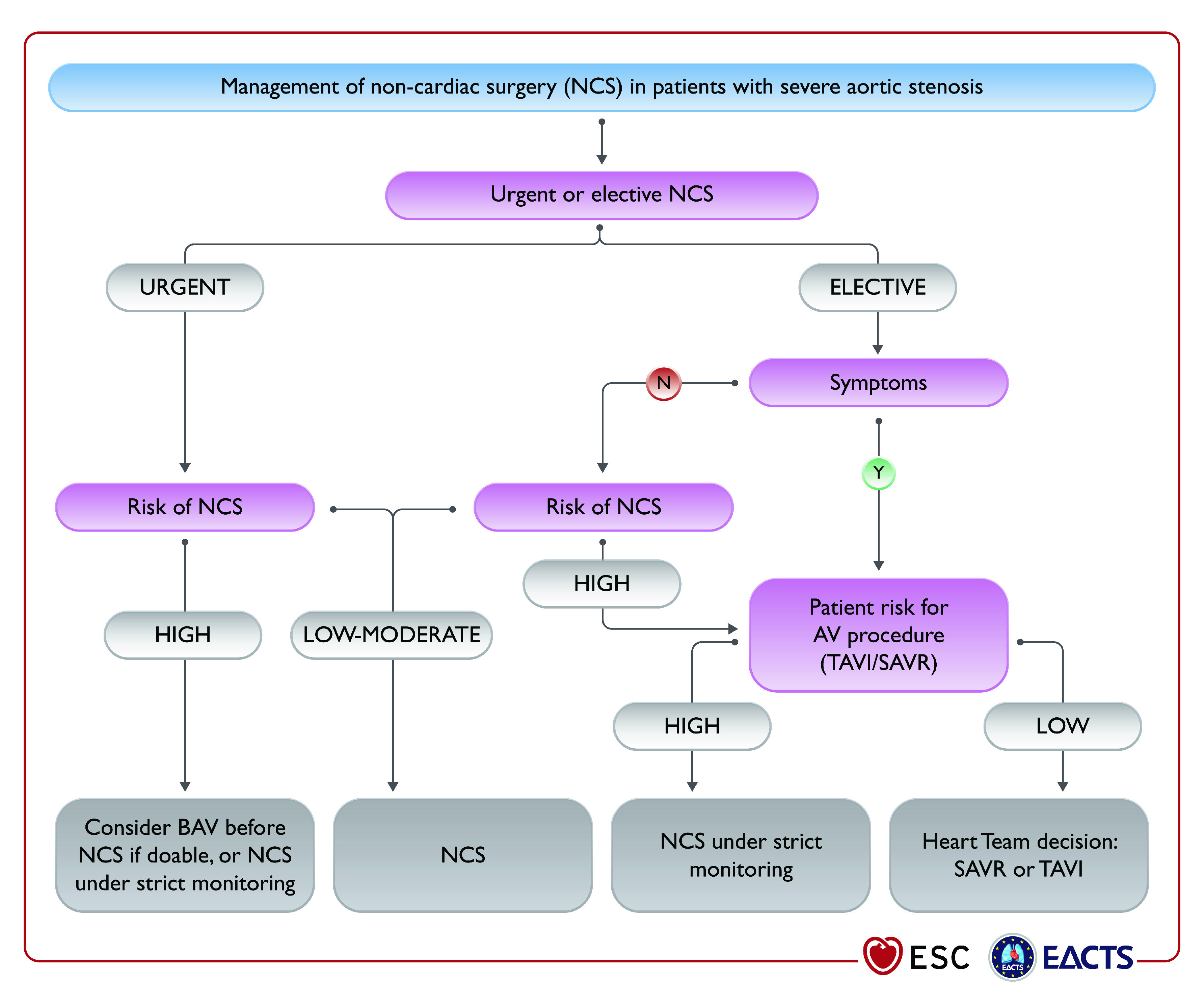

Indications for aortic valve intervention are summarized in the table of recommendations on indications for intervention in symptomatic and asymptomatic aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention and in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Management of patients with severe aortic stenosis.

BP: blood pressure; EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; STS-PROM: Society of Thoracic Surgeons – predicted risk of mortality; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TF: transfemoral. aSee Figure 3: Integrated imaging assessment of aortic stenosis. bProhibitive risk is defined in Supplementary Table 5. cHeart Team assessment based upon careful evaluation of clinical, anatomical, and procedural factors (see Table 6 and table on Recommendations on indications for intervention in symptomatic and asymptomatic aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention). The Heart Team recommendation should be discussed with the patient who can then make an informed treatment choice. dAdverse features according to clinical, imaging (echocardiography/CT), and/or biomarker assessment. eSTS-PROM: http://riskcalc.sts.org/stswebriskcalc/#/calculate, EuroSCORE II: http://www.euroscore.org/calc.html. fIf suitable for procedure according to clinical, anatomical, and procedural factors (Table 6).

5.2.1 SYMPTOMATIC AORTIC STENOSIS

Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis has dismal prognosis and early intervention is strongly recommended in all patients. The only exceptions are for those in whom intervention is unlikely to improve quality of life or survival (due to severe comorbidities) or for those with concomitant conditions associated with survival <1 year (e.g. malignancy) (section 3).

Intervention is recommended in symptomatic patients with high-gradient aortic stenosis, regardless of LVEF. However, management of patients with low-gradient aortic stenosis is more challenging:

LV function usually improves after intervention in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis, when reduced ejection fraction is predominantly caused by excessive afterload.32,180 Conversely, improvement is uncertain if the primary cause of reduced ejection fraction is scarring due to myocardial infarction or cardiomyopathy. Intervention is recommended when severe aortic stenosis is confirmed by stress echocardiography (true severe aortic stenosis; Figure 3),32 while patients with pseudo-severe aortic stenosis should receive conventional heart failure treatment.142,181 The presence or absence of flow reserve (increase in stroke volume ≥20%) d [oe]s not appear to influence prognosis in contemporary series of patients undergoing TAVI or SAVR,182,183,184 and although those with no flow reserve show increased procedural mortality, both modes of intervention improve ejection fraction and clinical outcomes.32,180,182 Decision making for such patients should take account of comorbidities, degree of valve calcification, extent of CAD, and feasibility of revascularization.

Data concerning the natural history of low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction, and outcomes after SAVR and TAVI remain controversial.162,165,167 Intervention should only be considered in those with symptoms and significant valve obstruction (see table of recommendations on indications for intervention in symptomatic and asymptomatic aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention and Figure 4).

The prognosis of patients with normal-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction is similar to that of moderate aortic stenosis –regular clinical and echocardiographic surveillance is recommended.165,166,185

5.2.2 ASYMPTOMATIC AORTIC STENOSIS

Intervention is recommended in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and impaired LV function of no other cause,9 and those who are asymptomatic during normal activities but develop symptoms during exercise testing.172,186 Management of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis is otherwise controversial and the decision to intervene requires careful assessment of the benefits and risks in an individual patient.

In the absence of adverse prognostic features, watchful waiting has generally been recommended with prompt intervention at symptom onset.187 Data from a single RCT have shown significant reduction in the primary endpoint (death during or within 30 days of surgery or cardiovascular death during the entire follow-up period) following early SAVR compared with conservative management [1% vs. 15%; hazard ratio 0.09; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.01-0.67; P = 0.003].188 However, subjects were selected per inclusion criteria (median age 64 years, minimal comorbidities, low operative risk) and follow-up in the conservative group was limited. Further randomized trials [EARLY TAVR (NCT03042104), AVATAR (NCT02436655), EASY-AS (NCT04204915), EVOLVED (NCT03094143)] will help determine future recommendations.

Predictors of symptom development and adverse outcomes in asymptomatic patients include clinical characteristics (older age, atherosclerotic risk factors), echocardiographic parameters (valve calcification, peak jet velocity189,190), LVEF, rate of haemodynamic progression,189 increase in mean gradient >20 mmHg with exercise,172 severe LV hypertrophy,191 indexed stroke volume,158 LA volume,192 LV global longitudinal strain,26,168,193 and abnormal biomarker levels (natriuretic peptides, troponin, and fetuin-A).170,171,194,195 Early intervention may be considered in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and one or more of these predictors if procedural risk is low (although application of TAVI in this setting has yet to be formally evaluated) (Table 6 and Figure 4). Otherwise, watchful waiting is a safer and more appropriate strategy.

5.2.3 THE MODE OF INTERVENTION

Use of SAVR and TAVI as complementary treatment options has allowed a substantial increase in the overall number of patients with aortic stenosis undergoing surgical or transcatheter intervention in the past decade.196 RCTs have assessed the two modes of intervention across the spectrum of surgical risk in predominantly elderly patients and a detailed appraisal of the evidence base is provided in Supplementary Section 5. In brief, these trials used surgical risk scores to govern patient selection and demonstrate that TAVI is superior to medical therapy in extreme-risk patients,197 and non-inferior to SAVR in high-198,199,200,201 and intermediate-risk patients at follow-up extending to 5 years.202,203,204,205,206,207,208 The more recent PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk trials demonstrate that TAVI is non-inferior to SAVR in low-risk patients at 2-year follow-up.209,210,211,212 Importantly, patients in the low-risk trials were predominantly male and relatively elderly (e.g. PARTNER 3: mean age 73.4 years, <70 years 24%, 70-75 years 36%, >75 years 40%, >80 years 13%) whilst those with low-flow aortic stenosis or adverse anatomical characteristics for either procedure (including bicuspid aortic valves or complex coronary disease) were excluded.

Rates of vascular complications, pacemaker implantation, and paravalvular regurgitation are consistently higher after TAVI, whereas severe bleeding, acute kidney injury, and new-onset AF are more frequent after SAVR. Although the likelihood of paravalvular regurgitation has been reduced with newer transcatheter heart valve designs, pacemaker implantation (and new-onset left bundle branch block) may have long-term consequences213,214,215 and further refinements are required. Most patients undergoing TAVI have a swift recovery, short hospital stay, and rapidly return to normal activities.216,217 Despite these benefits, there is wide variation in worldwide access to the procedure as a result of high device costs and differing levels of healthcare resources.71,218,219

The Task Force has attempted to address the gaps in evidence and provide recommendations concerning the indications for intervention and mode of treatment (Recommendations on indications for intervention in symptomatic and asymptomatic aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention, Recommendations D, Figure 4) that are guided by the RCT findings and compatible with real-world Heart Team decision making for individual patients (many of whom fall outside the RCT inclusion criteria). Aortic stenosis is a heterogeneous condition and selection of the most appropriate mode of intervention should be carefully considered by the Heart Team for all patients, accounting for individual age and estimated life expectancy, comorbidities (including frailty and overall quality of life, section 3), anatomical and procedural characteristics (Table 6), the relative risks of SAVR and TAVI and their long-term outcomes, prosthetic heart valve durability, feasibility of transfemoral TAVI, and local experience and outcome data. These factors should be discussed with the patient and their family to allow informed treatment choice.

Recommendations D. Recommendations on indications for intervention<sup>a</sup> in symptomatic (A) and asymptomatic (B) aortic stenosis and recommended mode of intervention (C).

| A) Symptomatic aortic stenosis | Classb | Levelc |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention is recommended in symptomatic patients with severe, high-gradient aortic stenosis [mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak velocity ≥4.0 m/s, and valve area ≤1.0 cm2 (or ≤0.6 cm2/m2)] . 235,236 | I | B |

| Intervention is recommended in symptomatic patients with severe low-flow (SVi ≤35 mL/m2), low-gradient (<40 mmHg) aortic stenosis with reduced ejection fraction (<50%), and evidence of flow (contractile) reserve. 32,237 | I | B |

| Intervention should be considered in symptomatic patients with low-flow, low-gradient (<40 mmHg) aortic stenosis with normal ejection fraction after careful confirmation that the aortic stenosis is severed (Figure 3). | IIa | C |

| Intervention should be considered in symptomatic patients with low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and reduced ejection fraction without flow (contractile) reserve, particularly when CCT calcium scoring confirms severe aortic stenosis. | IIa | C |

| Intervention is not recommended in patients with severe comorbidities when the intervention is unlikely to improve quality of life or prolong survival >1 year. | III | C |

| B) Asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis | ||

| Intervention is recommended in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and systolic LV dysfunction (LVEF <50%) without another cause. 9,238,239 | I | B |

| Intervention is recommended in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and demonstrable symptoms on exercise testing. | I | C |

| Intervention should be considered in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and systolic LV dysfunction (LVEF <55%) without another cause. 9,240,241 | IIa | B |

| Intervention should be considered in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis and a sustained fall in BP (>20 mmHg) during exercise testing. | IIa | C |

| Intervention should be considered in asymptomatic patients with LVEF >55% and a normal exercise test if the procedural risk is low and one of the following parameters is present: • Very severe aortic stenosis (mean gradient ≥60 mmHg or Vmax >5 m/s). 9,242 • Severe valve calcification (ideally assessed by CCT) and Vmax progression ≥0.3 m/s/year. 164,189,243 • Markedly elevated BNP levels (>3- age- and sex-corrected normal range) confirmed by repeated measurements and without other explanation. 163,171 |

IIa | B |

| C) Mode of intervention | ||

| Aortic valve interventions must be performed in Heart Valve Centres that declare their local expertise and outcomes data, have active interventional cardiology and cardiac surgical programmes on site, and a structured collaborative Heart Team approach. | I | C |

| The choice between surgical and transcatheter intervention must be based upon careful evaluation of clinical, anatomical, and procedural factors by the Heart Team, weighing the risks and benefits of each approach for an individual patient. The Heart Team recommendation should be discussed with the patient who can then make an informed treatment choice. | I | C |

| SAVR is recommended in younger patients who are low risk for surgery (<75 yearse and STSPROM/ EuroSCORE II <4%)e,f, or in patients who are operable and unsuitable for transfemoral TAVI. 244 | I | B |

| TAVI is recommended in older patients (≥75 years), or in those who are high risk (STSPROM/ EuroSCORE IIf >8%) or unsuitable for surgery. 197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,245 | I | A |

| SAVR or TAVI are recommended for remaining patients according to individual clinical, anatomical, and procedural characteristics. 202,203,204,205,207,209,210,212 f,g | I | B |

| Non-transfemoral TAVI may be considered in patients who are inoperable and unsuitable for transfemoral TAVI. | IIb | C |

| Balloon aortic valvotomy may be considered as a bridge to SAVR or TAVI in haemodynamically unstable patients and (if feasible) in those with severe aortic stenosis who require urgent highrisk NCS (Figure 11). | IIb | C |

| D) Concomitant aortic valve surgery at the time of other cardiac/ascending aorta surgery | ||

| SAVR is recommended in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing CABG or surgical intervention on the ascending aorta or another valve. | I | C |

| SAVR should be considered in patients with moderate aortic stenosish undergoing CABG or surgical intervention on the ascending aorta or another valve after Heart Team discussion. | IIa | C |