Abstract

We describe an implantable sensor developed to measure synovial fluid pH for noninvasive early detection and monitoring of hip infections using standard-of-care plain radiography. The sensor was made of a pH responsive polyacrylic acid-based hydrogel, which expands at high pH and contracts at low pH. A radiodense tantalum bead and a tungsten wire were embedded in the two ends of the hydrogel in order to monitor the change in length of the hydrogel sensor in response to pH via plain radiography. The effective pKa of the hydrogel-based pH sensor was 5.6 with a sensitivity of 3 mm/pH unit between pH 4 and 8. The sensor showed a linear response and reversibility in the physiologically relevant pH range of pH 6.5 and 7.5 in both buffer and bovine synovial fluid solutions with a 30-minute time constant. The sensor was attached to an explanted prosthetic hip and the pH response determined from the X-ray images by measuring the length between the tantalum bead and the radiopaque wire. Therefore, the developed sensor would enable noninvasive detection and studying of implant hip infection using plain radiography.

Keywords: hip infections, synovial fluid, pH, plain radiography, hydrogel

Graphical Abstract

The sensor uses a pH responsive polyacrylic acid-based hydrogel with a tantalum bead embedded within the hydrogel to monitor the change in length of the hydrogel sensor in response to pH via plain radiography. Results showed excellent inter-observer precision and reversible response to pH cycling in bovine synovial fluid. This novel technique will enable detection of hip infections early using already available X-ray imaging.

1. Introduction

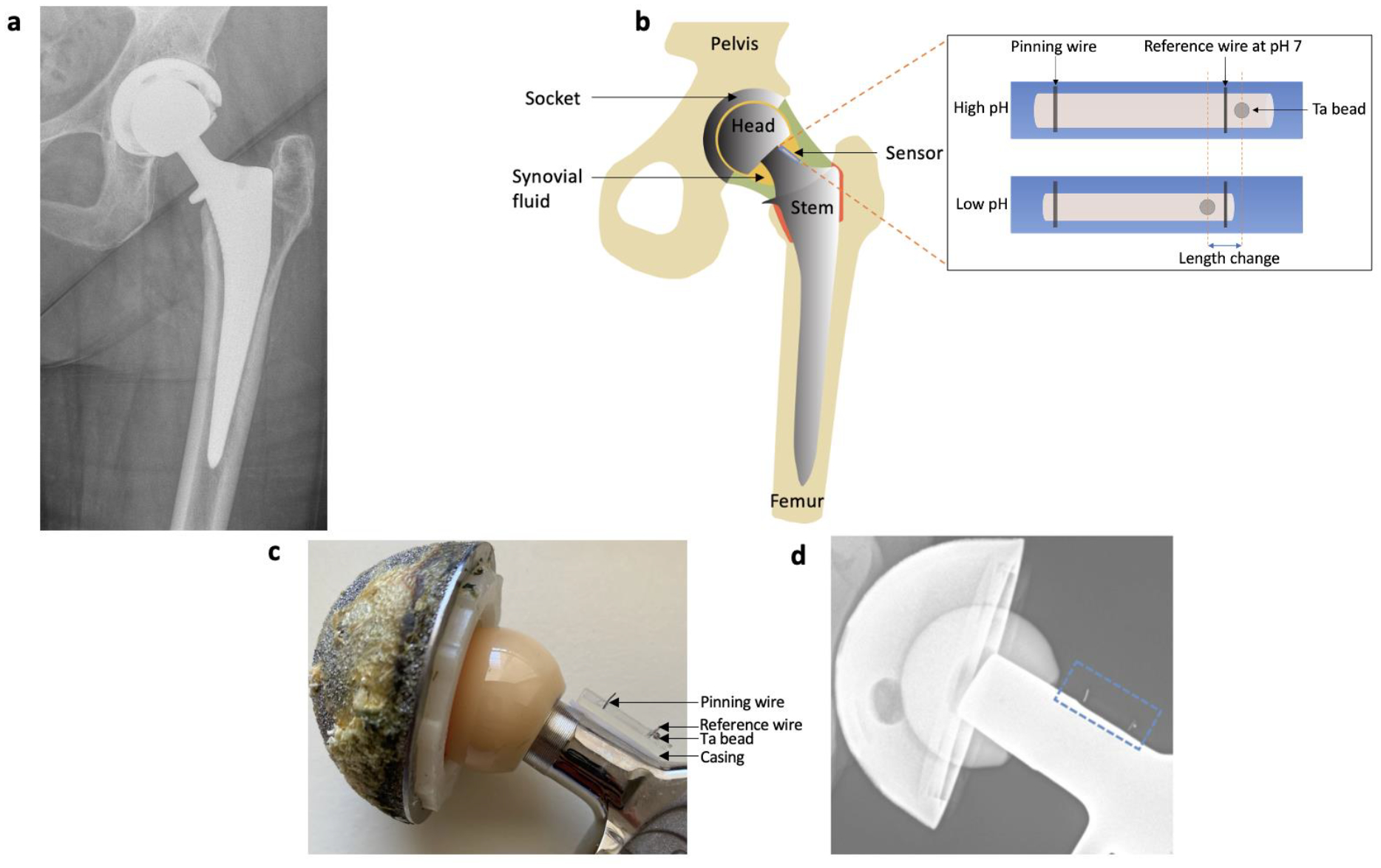

Hip replacement surgeries are performed on millions of people worldwide each year. During these surgeries, the hip is surgically removed and replaced with a prosthetic component (Figure 1a).[1] Successful joint replacement surgeries provide a safe and effective procedure that relieves pain, restores function and independence, thereby improving the quality of life of the patient.[2,3] Most of these joint arthroplasties are complication-free; however, one of the leading causes of failure following joint replacement surgery are post-surgery infections with an incidence of about ~0.5–2% of total hip replacement surgeries.[4,5] If detected early, these infections can potentially be treated with antibiotics and surgical debridement.[6] However, after 3 to 4 weeks, bacteria can produce biofilms that resist antibiotic treatment, which necessitates removal of prosthetic implants and then reimplantation.[2,7,8] As a result, these infections have high morbidity, mortality and financial costs. Revisions typically cost around $50,000 per patient with an estimated total hospital cost of $250 million per year to the healthcare system in USA.[9] Therefore, early detection of infections is very important for patients and the healthcare system in general.

Figure 1:

a) Radiograph of a patient with a prosthetic hip. b) Schematic diagram of prosthetic hip with attached synovial pH sensor. Inset shows the mechanism of pH sensing. c) Photograph of hip prosthesis with attached pH sensor. d) Radiograph of hip prosthesis with attached pH sensor.

Current diagnosis of post-surgery infections is based on a combination of clinical findings based on nonspecific symptoms, laboratory results from peripheral blood, microbiological data, histological evaluation of periprosthetic tissue, intraoperative inspection, and imaging techniques (such as X-ray, MRI, CT).[6,10] These procedures include systemic markers of inflammation which do not localize the inflammation source and have poor sensitivity/specificity for implant-associated infection. Infection markers can be more sensitive and specific in synovial fluid (fluid around synovial joint) than in serum because they are localized to the site of infection.[11] The current standard of care involves arthrocentesis when an infection is suspected, where the joint is aspirated using a syringe to collect synovial fluid from the joint capsule and analyzed for white blood cell count and differential, crystals, Gram stain, and culture.[12,13] In addition, the synovial fluid is composed of infection biomarkers such as glucose,[14] low pH/high lactate concentrations,[15] C-reactive protein,[16,17] interleukins,[18] interferon‐γ,[10] α defensin,[16] and cathelicidin[19] which can be useful for the diagnosis of infection.

Several studies show that in a well-mixed synovial joint fluid and during infection, synovial fluid pH decreases from 7.5 in aseptic conditions to 6.7–7.0.[14,20] In addition, pH correlates strongly with white blood cell count,[20,21] as well as lactic acid,[22,23] both of which are used to detect prosthetic joint infection: typical infection thresholds for synovial white blood cell count is >3000 cells/μL (sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 93%)[24] and for lactic acid is >8.3 mmol/L (sensitivity of 71.4% and specificity of 88%).[18] Acidosis results from production of acidic products as a result of metabolic activity of bacterial cells (e.g. short chain fatty acid by-products) and immune cells (e.g. lactic acid and carbon dioxide from anaerobic glycolysis activity).[25] However, arthrocentesis is not practical for routine screening or serial monitoring during treatment, since the procedure is painful and needs to be performed by a radiologist under fluoroscopic or ultrasonic image guidance.[26,27] In addition, improper/inadequate fluid aspiration or delayed measurement can confound analysis and reported complications include allergic reactions to the local anesthetic or the contrast agent used. Numerous detection methods have been studied to measure pH in tissue during infection using imaging methods such as positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[28,29] However, the currently available diagnostics have not been used to detect pH in synovial fluid and they lack sufficient sensitivity, specificity, and simplicity for early and effective noninvasive detection of infections.

We report the development of a X-ray based sensor inserted during surgery that could be used as a potential X-ray imaging functional chemical sensor for noninvasive detection and studying of implant infection (Figure 1b).[30,31] Physicians routinely use X-rays following prosthetic joint surgeries to image anatomy and associated pathologies because they penetrate through deep tissue and show contrast between air, soft tissue, bone, and metal hardware.[32,33] However, X-rays are usually blind to local biochemical information such as pH and insensitive to small biomechanical changes. Our sensor is the first sensor that is being developed to measure synovial fluid, radiographically. The sensor uses a polyacrylic-acid based hydrogel with pH-dependent swelling to report pH in a plain radiograph via measuring the position of a radio-dense tantalum bead in the hydrogel relative to a radiodense scale next to the hydrogel (see Figure 1). The sensor is attached to or integrated into the prosthesis prior to surgical implantation and would provide a painless, rapid, non-invasive, inexpensive, measurement using plain radiographs already acquired as part of the current standard of care.

2. Results and Discussion

Our goal was to develop an implantable sensor for noninvasive detection and monitoring of hip infections based on synovial fluid pH in order to study the environment and detect bacterial colonization early and monitor treatment until the infection is eradicated or for recurrence. Our sensor design employed a pH responsive hydrogel which swells at high pH and shrinks at low pH (Figure 1c), thereby moving a radiodense tantalum bead (0.5 mm in diameter) embedded in the hydrogel. Plain radiographs of the sensor will show the tantalum bead position relative to a tungsten wire marking the position at pH 7 (Figure 1d). Tantalum and tungsten were chosen as the preferred metals in the development of the sensor due to their biocompatibility, corrosion resistance and radio-opacity (high atomic number and density).[34–36] In order for the sensor to detect hip infections in vivo, it needs to measure physiologically relevant pH changes indicating infection with a precision of around 0.1 pH units in the range of pH 6.7–7.5, with an appropriate response rate (less than 12 hours to facilitate physiological measurements and preferably less than 1 hour to facilitate experimentation). For in vivo use, the sensor needs to be resistant to changes in temperature and ionic strength and maintain its performance in synovial fluid with minimal effect from biofouling. The sensor was designed in such a way it can be fitted on a prosthetic hip and be placed in the synovial fluid in a non-intrusive manner to measure its pH changes.

2.1. Sensor calibration and reversibility

Hydrogels are a group of water-swollen polymeric materials that exhibit reversible volume changes in response to environmental changes such as changes in pH, temperature, electric field and light.[31] These stimuli-responsive hydrogels are commonly used as smart soft materials in the fabrication of sensors and drug delivery systems. Since we are interested in measuring pH, we selected a hydrogel based on polyacrylic acid due to its high biocompatibility (e.g. used in diapers, cosmetics, and medical implants).[37,38] Polyacrylic acid is a commercially available pH sensitive synthetic polymer with pendant anionic acidic (–COOH) groups on the polymer chains. The hydrogel was prepared by free-radical copolymerization of monomers. acrylic acid and n-octyl acrylate (which shifts the effective pKa and calibration curve closer to neutral pH).[39,40] The resulting polymer chains were crosslinked using poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate as crosslinker and 2-oxoglutaric acid as photoinitiator. Photopolymerization in an inert atmosphere under UV light (365 nm) produced the hydrogel films used for the sensor fabrication.

In order to determine the pH response and effective pKa of the hydrogel films, a pH calibration was carried out by placing the hydrogel in a series of pH buffer standards (VWR Analytical, USA) and measuring its length. The results showed that the swelling behavior of the polyacrylic acid-based hydrogel is highly dependent on the pH of the surrounding medium due to the presence of carboxylic acid side groups (Figure 2a). At low pH, the carboxylic acid (–COOH) groups in the polyacrylic acid hydrogel chains of the network are neutral. At high pH, the carboxylic acid groups get deprotonated and become negatively charged carboxylate ions (–COO−).[41] The increased ionization in more alkaline environments causes the hydrogel to swell due to a combination of increased electrostatic repulsions between bound charges on the polymer chains and increased osmotic pressure.[39] A radiodense tantalum bead and a metal wire were embedded in the two ends of the hydrogel to monitor the change in length of the hydrogel sensor in response to pH via plain radiography.

Figure 2:

a) pH response of the polyacrylic acid hydrogel pH 2 to 11. b) Reversibility of polyacrylic acid hydrogel in bovine synovial fluid cyclically varied between pH 6.5 and 7.5. Lines show fit to an exponential.

The calibration curve was fitted to a modified Henderson–Hasselbach equation with the degree of swelling assumed to be proportional to the fraction of negatively charged (deprotonated) carboxyl groups (α) (equation 1 and 2). In the equations, pKa is the acid dissociation constant of polyacrylic acid, prefactor n is added to account for the distribution of dissociation constants, and α is the fraction of negatively charged (deprotonated) carboxyl groups, de is the equilibrium diameter of hydrogel, dmax and dmin are the maximum and minimum diameters of the hydrogel, respectively. From the calibration graph in Figure 2a, the sensitivity of the hydrogel sensor was determined to be 3 mm/pH unit in the pH range of 4–8. The pKa of the synthesized hydrogel was 5.56 and n value of 2.50. Similar results were observed when the experiment was repeated in bovine synovial fluid in the physiologically relevant pH.

| (1) |

| (2) |

The sensor response time and reversibility were studied in bovine synovial fluid by adjusting the synovial fluid to pH 6.5 and 7.5, the pH range relevant to infection. As seen in Figure 2b, the sensor showed a high reversibility in bovine synovial fluid under repeated cycles and no significant drift. The lack of drift (here and also after incubation in synovial fluid for days) is expected because it is an equilibrium-based sensor and is in contrast to most pH electrodes, which are highly sensitive to surface biofouling because they measure non-equilibrium current through the surface. The results in bovine synovial fluid were also similar to that observed in buffers. We also previously showed that the same hydrogel swelling was minimally affected by physiological variation in buffer and tryptic soy broth bacterial culture ionic strength, temperature (25–40 °C), or long term incubation in a highly oxidative environment with hydrogen peroxide and copper ions.[42]

The swelling and deswelling cycles were fit to an exponential decay, and had a time constant of around 30 minutes. Compared to buffer solutions, synovial fluid rates were slower likely due to increase in viscosity; however, since the lateral diffusion rate scales with the diameter squared, we reduced the diameter by half and found 30-minute response time. Although many physiological responses will be slow, on the order of hours or days, a faster rate is important for facilitating in vitro experiments; 30-minute rates would be appropriate for studying acute changes (e.g. after a glucose spike especially in diabetic patients), while slower response rates find average response.

2.2. Imaging sensor attached to prosthetic hip implant and inter-observer reliability

The sensor consists of a hydrogel in a polymer casing, pinned at one end with a tungsten wire and a radiodense tantalum bead embedded in the other end. Another tungsten wire marks the position at pH 7, and the tantalum bead position relative to the pH 7 mark can be used to determine the pH of the synovial fluid. The sensor was attached to the neck of the hip prosthetic implant so that the sensor would be in contact with synovial fluid but away from pressure bearing surfaces. The radiographs clearly showed the implant and the sensor position (Figure 3a). The change in length in response to pH can be determined from the X-ray images by measuring the length between the tantalum bead and the radiopaque wire. At pH 7.5, the bead could clearly be seen passing the pH 7 marker wire, while at pH 6.5, the bead was clearly before the marker.

Figure 3:

a) Sensor on implant at pH 7.5 and 6.5 in bovine synovial fluid. b) Five-observer study of randomized series of 15 radiographs in bovine synovial fluid between pH 6 and 8.5.

To assess inter-observer variability, five observers were given a randomized series of 15 radiographs in bovine synovial fluid between pH 6 and 8.5. Each observer measured bead position and distance between pin markers as a calibrant; the relative length and a prior-data calibration curve was used to determine “measured pH”. Figure 3b plots measured pH versus actual pH. The observers largely agreed with each other and with the values used in the initial calibration fit except at pH 6, where there was a 0.22 pH unit systematic error. Specifically, the average inter-observer precision was 0.03 pH units and inter-observer accuracy (root mean square difference from calibration fit) was 0.08 pH units (including the pH 6.0 data).

2.3. Limitations

The above study has several limitations especially with respect to ultimate clinical application. First, it was performed only in ex vivo bovine synovial fluid with added HCl and NaOH to adjust the pH (and previously in buffers and bacterial cultures with varying temperature, sodium chloride concentration, and oxidative environment).[42] The in vivo response may be different, especially after long term implantation.

Second, the experiment was performed without tissue and clothing, and with a device at a single orientation, the presence of tissue and orientation mismatch may affect the resolution. That said, the bead position is measured relative to a scale on the device which normalizes for changes in angle. We have consistently observed ~50–100 μm resolution on several portable X-ray systems (C-arm and portable X-rays) and with several different devices (pH sensor on orthopedic plate in cadaveric tibia,[42] orthopedic tibial plate bending indicator,[43] orthopedic screw bending sensor,[44] and a fluidic plate bending sensor).[45] This resolution appears to be mostly limited by the X-ray pixel resolution rather than device or sample. Most clinical standing X-rays are taken using equipment that includes anti-scatter grids which give better images than the equipment we are using. Additionally, the sensor resolution could be increased in future by making the sensor longer, adding mechanical gain,[46] using computer vision algorithms to estimate bead position in place of manual measurements, or changing composition.[47,48]

Third, although there have been many infection studies measuring white blood cell counts and synovial lactate concentration, which correlate with pH, there have only been a few studies which directly measured pH in synovial fluid after arthrocentesis,[15,20] in part because of pH drift if fluid is improperly stored.[20,49] Consequently, the sensitivity and specificity of pH would need to be evaluated clinically, especially compared to inflammation from aseptic loosening (which is also interesting but would be treated differently).[50,51] Moreover, the threshold and required resolution would depend upon the application, for example in early screening versus confirmation or monitoring.

The developed implantable sensor is expected to remain inside the body indefinitely. Two potential concerns regarding long term implantation involve potential health risks from any toxic degradation products and effect on long-term performance of the sensor. For the development of the sensor, we have selected materials that are designed for long-term implantation. Tantalum, which is used as a bead in the sensor to determine the length changes of the hydrogel, can be toxic if large volumes in the form of microparticles are inhaled or when injected as an intraperitoneal injection as a chloride salt in rats (LD50 of 38 mg/kg body weight).[52] However, the bead used in the sensor is smooth, does not dissolve and has excellent anticorrosion properties due to the presence of the stable tantalum oxide protective film formed on the surface of the metal.[34,53] Tantalum-based materials have been widely used in clinical applications as radiographic markers, in joint implants, reconstructive surgery, and in dental applications.[34,54] Most of these implants would remain inside the body, without being removed in the lifetime of the patient and the passivity of the metal towards biological tissues from medical implants left in the body over long periods have been reported with no adverse health effects.[55] The polyacrylic acid based hydrogel which responds to pH, is expected to have very low degradation as well, thus minimizing the release of any toxic products. Acrylic acid polymers are widely used in drug delivery, biosensors, membrane and separation devices due to their biocompatibility and extended life-span.[31,56] Even though shorter chain length acrylates can degrade and be excreted easily,[57,58] the hydrogels with their crosslinked polymer networks such as this, is expected to be highly resistant to degradation within the lifetime of the patient.[59,60]

For all implanted chemical sensors, sensor fouling would affect the performance of the sensor, in vivo.[61,62] Fouling is considered less of a concern for an equilibrium sensor as described here, although build-up could slow diffusion and affect the response rate. No fouling effect on the sensor calibration curve, response rate or sensor degradation was observed in solutions of tryptic soy broth bacterial cell culture, bovine synovial fluid, bovine serum, highly oxidative hydrogen peroxide and copper ion medium, or storage in pH 7 buffer. Several studies using polyacrylic acid-based hydrogels also demonstrated the stability of these materials in vivo. However, modifications can be made to the sensor to improve the life time by encasing the sensor and fluid in a carbon dioxide permeable membrane such as polydimethylsiloxane, which is impermeable to aqueous molecules.[63,64]

To better address these issues, we are planning future studies ex vivo in patient samples and in vivo in total hip arthroplasty sheep studies. We also plan to alter the hydrogel composition (e.g., using enzymes, antibodies,[66] and selectively permeable membranes[63]) to detect other biomarkers of infection, such as glucose,[67] carbon dioxide,[22] alpha-defensin[16] levels.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we describe the first implantable sensor that measures synovial fluid pH using plain radiography. The sensor has a linear response and repeatable response within 30 minutes in the range of pH 6.5 and 7.5 in bovine synovial fluid solutions and a pH accuracy of 0.08 pH units. The approach is rapid, non-invasive, and uses X-rays that are already taken as part of the postoperative standard of care. Thus, the developed sensor could be used as a potential X-ray imaging functional chemical sensor to detect post-surgery hip infections.

4. Experimental Section/Methods

Materials:

Acrylic acid 99% (Sigma, USA), anhydrous, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate with average Mn 700 (Sigma, USA), N,N-dimethyl formamide (Sigma, USA), phosphate buffer saline (Sigma, USA), n-octyl acrylate containing 400 ppm 4-methoxyphenol as inhibitor (Scientific Polymer Products, USA), 2-oxoglutaric acid (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, USA), reference standard pH buffers ranging from 2 to 11 (VWR Analytical, USA) were used as received. Bovine synovial fluid was obtained from Lampire Biological Labs, Pipersville, PA.

Synthesis of pH sensing hydrogel:

The hydrogel was prepared by free-radical co-polymerization of acrylic acid and n-octyl acrylate as the monomers, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (Mn 700) as the crosslinker and 2-oxoglutaric acid as the photoinitiator, with N,N-dimethyl formamide as the solvent. The photo-polymerization reaction was performed under an inert nitrogen atmosphere using UV irradiation (365 nm) from both sides of the reaction cell. The resulting polyacrylic acid-based hydrogel films were washed with 70% ethanol to remove any residual monomers, N,N-dimethyl formamide and hydrate the hydrogel. The hydrogel was washed daily for at least 5 days to ensure removal of unreacted monomers and initiators in the hydrogel film. Hydrogel samples of length ~10 mm was transferred to pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

Sensor calibration:

Hydrogel samples (length ~10 mm in pH 7 reference standard buffer) was fully immersed in a series of standard pH buffers ranging from 2 to 11 at room temperature (25 °C) and its size was measured photographically using the NIH ImageJ software package. Bovine synovial fluid was adjusted from pH 5–9 and the response of the sensor to pH changes in synovial fluid was studied.

Sensor reversibility:

The hydrogel sensor was alternately placed in bovine synovial fluid adjusted to pH 6.5 to pH 7.5. The size of the hydrogel sensor can be determined with NIH ImageJ software.

Imaging sensor attached to prosthetic hip implant:

The sensor was prepared by pinning one end of the hydrogel in a polymer casing with a tungsten wire, and a radiodense tantalum bead (0.5 mm diameter) was embedded in the other end. Another tungsten wire was placed to mark the position of the hydrogel at pH 7. The sensor was placed on the neck of the prosthetic hip implant and X-ray images were taken at pH 6.5 and 7.5 in bovine synovial fluid.

Inter-observer reliability of sensor:

Fifteen radiographs of sensor attached to the prosthetic implant in bovine synovial fluid between pH 6 and 8.5 were given to five observers. The order was randomized. Each observer measured length of the sensor for each radiograph using NIH ImageJ software.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported through NIH R01 AR070305-01, NIH P30 GM131959, and Wallace R. Roy Professorship.

Footnotes

Disclosure: JNA and CJB are inventors on a patent which describes the pH sensing device (US 10,667,745 B2) and are co-founders of Aravis BioTech LLC which has licensed the patent from the Clemson University Research Foundation (CURF).

Contributor Information

John D. Adams, Prisma Health-Upstate, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Second Floor Support Tower, 701 Grove Road, Greenville, SC 29605, USA

Caleb J. Behrend, OrthoArizona, 1675 E. Melrose St., Gilbert, AZ 85297, USA

Jeffrey N. Anker, Departments of Chemistry and BioEngineering, and Center for Optical Materials Science and Engineering Technology (COMSET), Clemson University, 102 BRC, 105 Collings St., Clemson, SC 29634, USA.

References

- [1].Tande AJ, Patel R, Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2014, 27, 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Felson DT, Ann. Intern. Med 2000, 133, 726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jones CA, Beaupre LA, Johnston DWC, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am 2007, 33, 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Del Pozo JL, Patel R, N. Engl. J. Med 2009, 361, 787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J, Clin. Orthop 2008, 466, 1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, Rao N, Hanssen A, Wilson WR, Clin. Infect. Dis 2013, 56, e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ, Ferraz MP, Biomatter 2012, 2, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Betsch BY, Eggli S, Siebenrock KA, Täuber MG, Mühlemann K, Clin. Infect. Dis 2008, 46, 1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Esposito S, Leone S, Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 32, 287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Deirmengian C, Hallab N, Tarabishy A, Della Valle C, Jacobs JJ, Lonner J, Booth RE, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2010, 468, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fink B, Makowiak C, Fuerst M, Berger I, Schäfer P, Frommelt L, J. Bone Joint Surg. Br 2008, 90-B, 874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Trampuz A, Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR, Cockerill FR, Hanssen AD, Patel R, Rev. Med. Microbiol 2003, 14, 1. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Birlutiu V, Biomed Res 2017, 28, 11. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lenski M, Scherer MA, Infect. Dis 2015, 47, 399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Treuhaft PS, McCarty DJ, Arthritis Rheum 1971, 14, 475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].De Vecchi E, Romanò CL, De Grandi R, Cappelletti L, Villa F, Drago L, Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol 2018, 32, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Parvizi J, Jacovides C, Adeli B, Jung KA, Hozack WJ, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2012, 470, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lenski M, Scherer MA, J. Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shahi A, Parvizi J, EFORT Open Rev 2016, 1, 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Acidosis of synovial fluid correlates with synovial fluid leukocytosis, Am. J. Med 1978, 64, 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Park S-Y, Kim I-S, Inflamm. Res 2013, 62, 399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Treuhaft PS, McCarty DJ, Arthritis Rheum 1971, 14, 475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brook I, Reza MJ, Bricknell KS, Bluestone R, Finegold SM, Arthritis Rheum 1978, 21, 774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schinsky MF, Della Valle CJ, Sporer SM, Paprosky WG, J. Bone Jt. Surg.-Am. Vol 2008, 90, 1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang F, Raval Y, Chen H, Tzeng T-RJ, DesJardins JD, Anker JN, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2014, 3, 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yee DK, Chiu K, Yan C, Ng F, J. Orthop. Surg 2013, 21, 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brannan SR, Jerrard DA, J. Emerg. Med 2006, 30, 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cyteval C, Bourdon A, Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2012, 93, 547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Potapova I, Diagnostics 2013, 3, 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ahmed EM, J. Adv. Res 2015, 6, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Caló E, Khutoryanskiy VV, Eur. Polym. J 2015, 65, 252. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen H, Rogalski MM, Anker JN, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2012, 14, 13469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Uzair U, Benza D, Behrend CJ, Anker JN, ACS Sens 2019, 4, 2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cristea D, Ghiuță I, Munteanu D, 2015, 8, 8. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shah Idil A, Donaldson N, J. Neural Eng 2018, 15, 021006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Prasad K, Bazaka O, Chua M, Rochford M, Fedrick L, Spoor J, Symes R, Tieppo M, Collins C, Cao A, Markwell D, (Ken) Ostrikov K, Bazaka K, Materials 2017, 10, 884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Elliott JE, Macdonald M, Nie J, Bowman CN, Polymer 2004, 45, 1503. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Salomé Veiga A, Schneider JP, Biopolymers 2013, 100, 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Philippova OE, Hourdet D, Audebert R, Khokhlov AR, Macromolecules 1997, 30, 8278. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Philippova OE, Hourdet D, Audebert R, Khokhlov AR, Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2822. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Drozdov AD, deClaville Christiansen J, J. Chem. Phys 2015, 142, 114904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arifuzzaman Md., Millhouse PW, Raval Y, Pace TB, Behrend CJ, Beladi Behbahani S, DesJardins JD, Tzeng T-RJ, Anker JN, The Analyst 2019, 144, 2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pelham H, Benza D, Millhouse PW, Carrington N, Arifuzzaman Md., Behrend CJ, Anker JN, DesJardins JD, Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Carrington NT, Milhouse PW, Behrend CJ, Pace TB, Anker JN, DesJardins JD, (Preprint) medRxiv: 10.1101/2020.09.04.20183251, submitted: Sept 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rajamanthrilage AC, Arifuzzaman Md., Millhouse PW, Pace TB, Behrend CJ, DesJardins JD, Anker JN, (Preprint) bioRxiv: 10.1101/2020.08.27.268169, submitted: Aug 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Anker J, Behrend CJ, DesJardins JD (Clemson University Research Foundation; ), US 10,667,745 B2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kuo C-Y, Don T-M, Lin Y-T, Hsu S-C, Chiu W-Y, J. Polym. Res 2019, 26, 18. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Guo J, Li L, Ti Y, Yhu J, Express Polym. Lett 2007, 1, 166. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kerolus G, Clayburne G, Schumacher HR, Arthritis Rheum 1989, 32, 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Birlutiu V, Biomed Res 2017, 28, 11. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Song Z, Borgwardt L, Høiby N, Wu H, Sørensen TS, Borgwardt A, Orthop. Rev 2013, 5, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cochran D, KW J, Mazur D, KP M, Arch Indusl Hyg. & Occupational Med 1950, 1, 637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Namur RS, Reyes KM, Marino CEB, Mater. Res 2015, 18, 91. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Eliaz N, Materials 2019, 12, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Burke GL, Can Med Assoc J 1940, 43, 125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hoffman AS, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2012, 64, 18. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gaytán I, Burelo M, Loza-Tavera H, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2021, 105, 991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Larson RJ, Bookland EA, Williams RT, Yocom KM, Saucy DA, Freeman MB, Swift G, J. Environ. Polym. Degrad 1997, 5, 41. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lyu S, Untereker D, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2009, 10, 4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sennakesavan G, Mostakhdemin M, Dkhar LK, Seyfoddin A, Fatihhi SJ, Polym. Degrad. Stab 2020, 180, 109308. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Xu J, Lee H, Chemosensors 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gray M, Meehan J, Ward C, Langdon SP, Kunkler IH, Murray A, Argyle D, Vet. J 2018, 239, 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Herber S, Bomer J, Olthuis W, Bergveld P, van den Berg A, Biomed. Microdevices 2005, 7, 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Burke CS, Markey A, Nooney RI, Byrne P, McDonagh C, Sens. Actuators B Chem 2006, 119, 288. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sharifzadeh G, Hosseinkhani H, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2017, 6, 1700801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Miyata T, Asami N, Uragami T, Macromolecules 1999, 32, 2082. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Brannan SR, Jerrard DA, J. Emerg. Med 2006, 30, 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]