Abstract

Although microvascular decompression (MVD) is a reliable treatment for hemifacial spasm (HFS), postoperative delayed relief of persistent HFS is one of the main issues. In patients with hemifacial spasm, stimulation of a branch of the affected facial nerve elicits an abnormal response in the muscles innervated by another branch. Several specific types of waves were found in the abnormal muscle response (AMR). This study aimed to confirm the relationship between the initial morphology of the AMR wave and delayed relief of persistent HFS after MVD. We retrospectively analyzed and compared the data from 47 of 155 consecutive patients who underwent MVD for HFS at our hospital between January 2015 and March 2020. Based on the pattern of the initial AMR morphology on orbicularis oculi and mentalis muscle stimulation, patients were divided into two groups, namely, the monophasic and polyphasic groups. The results of MVD surgery for HFS were evaluated 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year postoperatively, by evaluating whether or not the symptoms of HFS persisted at the time of each follow-up. There were significantly higher rates of persistent postoperative HFS in patients with the polyphasic type of initial AMR at 1 week and 1 month after the surgery (p < 0.05, respectively), as assessed using Yates chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. A significant correlation was observed between delayed relief after MVD and polyphasic morphology of the AMR in electromyographic analysis in patients with hemifacial spasm.

Keywords: abnormal muscle response, demyelination, ephaptic transmission, hemifacial spasm, microvascular decompression

Introduction

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is a motor disorder characterized by involuntary tonic-clonic activity of the muscles innervated by the facial nerve on the ipsilateral side of the face.1,2) Since vascular compression of the facial nerve at the root exit zone (REZ) is widely accepted as the main cause of HFS,3-6) microvascular decompression (MVD) of the facial nerve is a well-established surgical treatment for HFS, producing relatively good results with minimal complications.7-12) Although the majority of patients immediately become spasm-free, about 10-40% still experience residual spasm after MVD surgery.13-20) In a multivariate analysis, Terasaka et al. revealed a significant correlation between preoperative anticonvulsant therapy and delayed cure after MVD,19) but the other causes of delayed symptom relief in HFS remained unclear.

Abnormal muscle responses (AMRs), elicited by electrically stimulating one branch of the facial nerve while recording electromyographic responses from a muscle innervated by another branch of the facial nerve, are useful for the electrophysiological diagnosis of HFS, because they represent an abnormal electromyographic response characteristic in HFS patients.21,22) So far, AMR waves have only been assessed as “residual” or “diminished” during MVD and have not been evaluated qualitatively. Two characteristic types of AMR waves were identified, and it was hypothesized that the presence of polyphasic AMRs on preoperative electromyography is likely to have a correlation with demyelination of the facial nerve in HFS patients and that this demyelination is one of the causes of delayed cure after MVD. This study aimed to compare the rate of persistent HFS after MVD between patients with an initial polyphasic AMR and those whose preoperative AMR showed a monophasic pattern. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the correlation between the initial AMR morphology and delayed cure after MVD in patients with HFS.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nakamura Memorial Hospital and was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants in this observational, non-randomized study were identified via a retrospective electronic chart review of HFS patients treated between January 2015 and March 2020 at the Nakamura Memorial Hospital. All surgical procedures were performed by a senior doctor (S.N.), a skilled neurosurgeon with 22 years of experience.

Patients

To allow evaluation of the unaffected facial nerve, we excluded patients who met the following criteria: (1) past medical history of botulinum neurotoxin injection, (2) previous MVD surgery, and (3) a history of Bell's palsy, trauma, or other surgical treatment around their facial nerve area. We also excluded patients with (4) an unmeasurable initial AMR or in whom all the waveform amplitudes were less than 10 μV and (5) early loss to follow-up.

Intraoperative AMR monitoring

Intraoperative AMR monitoring was performed using a Neuromaster MEE-1232 or a Neuromaster G1 MEE-2000 monitoring system (Nihon Kohden, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After induction of general anesthesia, paired stainless steel needle electrodes were inserted subdermally into the orbicularis oculi and mentalis muscles. AMRs were recorded from the mentalis muscle after electrical stimulation of the temporal branch of the facial nerve and from the orbicularis oculi muscle after stimulation of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. AMRs were recorded using amplifiers with a frequency band of 20 Hz to 3 kHz. The initial AMR was recorded by supramaximal stimulation before opening the dura mater, after confirming the depth of general anesthesia with bispectral index monitoring. The initial AMR was measured several times to confirm its repeatability. Subsequently, AMR was continuously recorded at 1-min intervals during surgery. Cases in which the AMR disappeared with stimulation of both the temporal branch and the marginal mandibular branch were defined as showing AMR disappearance.

Surgical procedure

The surgery was performed using a lateral suboccipital retrosigmoid approach with continuous intraoperative monitoring of brain auditory evoked potentials and the lateral spread response (LSR). A C-shaped skin incision was made behind the ear within the hairline. A 4-cm bone flap was made in the inferolateral portion of the suboccipital region to expose the inferior part of the sigmoid sinus. After dural opening, a small amount of cerebrospinal fluid was drained from the lateral cerebellomedullary cistern. Arachnoid membrane dissection was initiated from the lower cranial nerves with gentle cerebellar retraction. Following exposure of the REZ of the facial nerve and the facial and vestibulocochlear nerve complex, transposition of the offending vessels was performed using Teflon felt and fibrin glue. The dura mater was closed after ruling out compression of the REZ and the proximal facial nerve by other vessels.23)

Analysis of the initial AMR morphology

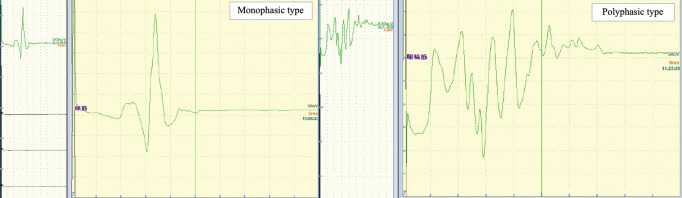

The patterns of the AMR were classified as monophasic and polyphasic types (Fig. 1). Briefly, waveforms with up to two spikes of over 30% of the maximum amplitude were defined as the monophasic type, and those with three or more spikes were defined as the polyphasic type. The number of spikes, their duration and the maximum amplitude of the initial AMR were measured and compared between the two types of waveforms. AMR morphology was analyzed by three experienced neurosurgeons blinded to the clinical data. In cases where there were discrepancies in the results of waveform evaluations, the majority decision was given priority.

Fig. 1.

Classification of the abnormal muscle response.

The patterns of the abnormal muscle response (AMR) were classified as monophasic and polyphasic types. Briefly, waveforms with up to two spikes over 30% of the maximum amplitude were defined as monophasic type, and those with three or more spikes were defined as polyphasic type.

Evaluation of surgical results

The surgical results for HFS were evaluated 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year after the surgery. Based on the classification proposed by the Japan Society for Microvascular Decompression Surgery, the symptoms of HFS were evaluated as either being cured or not at the time of each follow-up. In this study, all follow-ups in the patients were conducted only by the senior doctor (S.N.).

Clinical and statistical analysis

Based on the results of the initial AMR morphology with orbicularis oculi and mentalis muscle stimulation, the patients were divided into two groups. Patients with a monophasic spike pattern in the initial AMR for both muscles were categorized as the monophasic group, while those with a polyphasic AMR pattern in even one of the muscles evaluated were classified as the polyphasic group. The primary outcome was the healing rate at 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year after the surgery. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed using the unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

To identify the predictive factors for delayed relief after MVD, logistic regression analyses were applied using candidate clinical factors, including polyphasic wave, patient age, sex, spasm side, symptom duration, risk factors, offending vessel, and intraoperative AMR disappearance. The odds ratio with confidence interval (CI) was calculated for each factor, and multivariate analysis was performed using the factors for which the p value was below 0.30. Statistical significance was defined as a p value less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Evaluation of monophasic and polyphasic waves

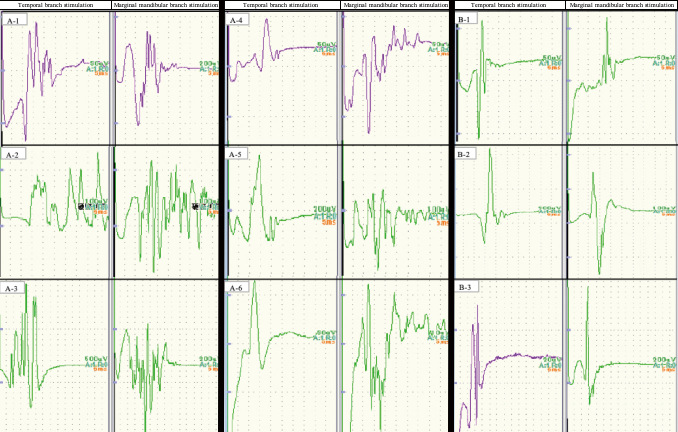

Table 1 presents the results of evaluation of the waveforms in terms of the type of AMR. The polyphasic wave consisted of waves with a long duration that appeared with both temporal and marginal mandibular branch stimulation. Fig. 2 shows example waveforms of AMRs in each group. In this study, the initial AMR morphology of the polyphasic type was not mixed with the monophasic morphology in several stimulations during decision-making for each patient's initial wave. Fig. 2A-1-A-3 shows polyphasic-type AMRs with both temporal and marginal mandibular branch stimulation in the polyphasic group. Fig. 2A-4-A-6 shows polyphasic-type waveforms on one side and monophasic-type waveforms on the other side in the polyphasic group. Fig. 2B-1-B-3 shows monophasic-type waveforms on both sides in the monophasic group.

Table 1.

Results of evaluation of the abnormal muscle responses

| Evaluation of each waveform | Polyphasic wave | Monophasic wave | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal branch stimulation, n | 7 | 40 | |

| number of spikes (mean ± SD), n | 4.86 ± 2.79 | 1.35 ± 0.48 | p < 0.05 |

| duration (mean ± SD), ms | 27.14 ± 9.20 | 20.25 ± 5.80 | p < 0.05 |

| maximum amplitude (mean ± SD), μV | 100.86 ± 66.03 | 114.53 ± 95.00 | 0.36 |

| Marginal mandibular branch stimulation, n | 21 | 26 | |

| number of spikes (mean ± SD), n | 4.14 ± 2.51 | 1.62 ± 0.49 | p < 0.05 |

| duration (mean ± SD), ms | 28.81 ± 7.38 | 21.73 ±5.71 | p < 0.05 |

| maximum amplitude (mean ± SD), μV | 61.88 ± 37.91 | 83.88 ± 86.86 | 0.15 |

Polyphasic waves, consisting of waves with a long duration, appeared with both temporal and marginal mandibular branch stimulation. SD standard deviation

Fig. 2.

Examples of the different types of waveforms classified as abnormal muscle responses in each group.

Fig. 2A-1-A-3 shows the polyphasic type of abnormal muscle response with both temporal and marginal mandibular branch stimulation. Fig. 2A-4-A-6 shows polyphasic waveforms on one side and monophasic waveforms on the other side. Fig. 2B1-B-3 shows monophasic waveforms on both sides.

Clinical information

We analyzed the data of 47 of 155 consecutive patients who underwent MVD for HFS at our hospital during the study period, after excluding 66 patients with a past history of botulinum neurotoxin injection, 2 patients with prior MVD surgery, 25 patients with an unmeasurable initial AMR or in whom all the waveform amplitudes were less than 10 μV, and 15 patients who were lost to follow-up. None of the patients had a history of Bell's palsy, trauma, or other surgical treatment around their facial nerve area. Table 2 presents the general characteristics of the subjects stratified according to the pattern of the initial AMR. Baseline data did not differ between the two groups, except for the percentage of cases in which the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) was the offending vessel. None of the patients had the complication of facial palsy at the time of follow-up.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study groups

| Baseline characteristics | Polyphasic group

(n = 23) |

Monophasic group

(n = 24) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 53.3 ± 11.9 | 53.3 ± 14.8 | 1 |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (30.4) | 13 (54.2) | 0.18 |

| Side (left), n (%) | 14 (61.0) | 15 (62.5) | 0.85 |

| Symptomatic duration | 51.9 ± 46.2 | 59.8 ± 70.5 | 0.65 |

| (mean ± SD), months | |||

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 7 (30.4) | 3 (12.5) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.23 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (13.0) | 3 (12.5) | 1 |

| Offending vessels, n (%) | |||

| AICA | 20 (87.0) | 14 (58.3) | p < 0.05 |

| PICA | 8 (34.8) | 10 (41.7) | 0.85 |

| VA | 4 (17.4) | 9 (37.5) | 0.22 |

| Complex | 9 (39.1) | 7 (29.2) | 0.68 |

Baseline data did not differ between the two groups, except for the percentage of cases in which the AICA was the offending vessel. SD standard deviation, AICA anterior inferior cerebellar artery, PICA posterior inferior cerebellar artery, VA vertebral artery

Primary outcome measures

There were significantly higher rates of residual postoperative hemifacial spasm in the polyphasic group at 1 week and 1 month after the surgery (p < 0.05, respectively), as assessed using Yates chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test (Table 3). On the other hand, the rate of residual postoperative HFS at 1 year after surgery did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.11).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes of the study groups

| Clinical outcomes | Polyphasic group

(n = 23) |

Monophasic group

(n = 24) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up period (mean ± SD), months | 40.5 ± 18.5 | 50.3 ± 21.2 | 0.1 |

| Remaining spasm, n (%) | |||

| Postoperation | 13 (56.5) | 4 (16.7) | p < 0.05 |

| Within 1 month | 10 (43.5) | 2 (8.3) | p < 0.05 |

| Within 1 year | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.11 |

| Recurrence | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 |

| Intraoperative AMR disappearance, n (%) | 19 (82.6) | 15 (62.5) | 0.19 |

| Complications | |||

| Subdural hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) | 1 |

| Hoarseness | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 |

| Dysphagia | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 |

There were significantly higher rates of remaining postoperative hemifacial spasm in the polyphasic group at both 1 week and 1 month after the surgery (p < 0.05, respectively), as assessed using Yates chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test.

Other parameters

There were no differences in the intraoperative AMR disappearance rate and permanent complications rate between the two groups (Table 3).

Predictive factor for delayed cure

According to multivariate analysis (Table 4), presence of polyphasic waves was found to be the sole significant predictive factor for delayed cure (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Predictors of delayed relief after microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm

| Parameters | Univariate-logistic regression analysis | Multivariate-logistic regression analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Polyphasic wave | < 0.05 | 10.5 (1.96-56.00) | < 0.05 |

| Age | 0.13 | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | 0.12 |

| Male | 0.89 | - | - |

| Side | 0.35 | - | - |

| Symptomatic duration | 0.82 | - | - |

| Risk factors | - | - | |

| Hypertension | 0.31 | - | - |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.87 | - | - |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.87 | - | - |

| Offending vessel | - | - | |

| AICA | 0.25 | 1.3 (0.19-9.08) | 0.79 |

| PICA | 0.75 | - | - |

| VA | 0.18 | 1.82 (0.18-18.60) | 0.62 |

| Complex | 0.16 | 0.20 (0.02-1.86) | 0.16 |

| Intraoperative AMR dissapearance | 0.84 | - | - |

Polyphasic waves were statistically significantly related to delayed relief after microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm on multivariate logistic regression analysis. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

Although MVD is a reliable treatment for HFS, the exact reasons for surgical failure remain unclear. In particular, delayed postoperative cure of persistent HFS is one of the most challenging issues. In previous reports, factors such as intraoperative LSR, the pattern of neurovascular compression, good clinical outcome at 3 months after MVD, and intraoperative evidence of the severity of the REZ indentation were proposed as prognostic factors for better outcomes.17,24,25) In their multivariate analysis, Terasaka et al. demonstrated a significant correlation between preoperative anticonvulsant therapy and delayed cure after MVD.19) The percentage of delayed cures in the polyphasic group in the present study (56.5% at 1 week after surgery and 43.5% at 1 month after the surgery) was higher than those reported in previous reports by both Shin et al. (37.4%) and Terasaka et al. (39.2%).18,19) Our results suggest that the initial morphology of the AMR might be an important factor for estimating a delayed cure after MVD. To the best of our knowledge, only one previous paper has evaluated the correlation between intraoperative morphology of the AMR and cure rates of HFS after MVD, although they did not examine the correlation between the morphology of the AMR and delayed cure.26)

Mechanism of polyphasic wave formation in AMRs

In peripheral nerves, the morphology of F-waves, which result from the backfiring of antidromically activated anterior horn cells, has been studied using electromyography. Ishikawa, M. et al. revealed that F-wave duration, F/M amplitude ratio, and the frequency of appearance of the F-wave on the patients' facial spasm side were significantly higher compared with those on the normal side and in healthy controls.27-29) In this study, the polyphasic wave consisted of waves with a long duration that appeared with both temporal and marginal mandibular branch stimulation.

Several papers have shown that demyelination of the facial nerve is one of the mechanisms of HFS30,31) and that the morphology of the wave in polyphasic-type AMRs is very similar to the demyelinating wave in the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) in patients with demyelinating polyneuropathy, such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy or Guillain-Barré syndrome.32-36) According to a previous report, ephaptic transmission at the vascular compression site is the origin of the AMR seen in HFS, by providing a shorter AMR latency than R1 of the blink reflex.37) When depolarization reaches a critical level due to contralateral stimulation, the voltage-gated Na channel opens, leading to generation of an action potential. The action potential is constant regardless of the type and size of the stimulus during the generation process, thus obeying the all-or-none law.38-41) Therefore, the AMR waveform is considered to be a change that strongly reflects the effect of demyelination after ephaptic transmission. Our results suggest that presence of the polyphasic AMR is associated with the degree of demyelination of the temporal and mandibular branches of the facial nerve at the vascular compression site. In cases that showed both monophasic and polyphasic waveforms, the degree of demyelination differed between the temporal and mandibular branches, and multilayered waveforms were only seen when the signal was transmitted to the side with the stronger demyelination.

Causative vessel and AMR waveform

In this study, the AICA was found to be the offending vessel significantly more often in the polyphasic group than in the monophasic group. Previous studies have also described that the AICA was the vessel most frequently responsible for compression at the site of the facial nerve REZ.42,43)

The facial nerve REZ is commonly defined as the proximal segment from the facial root exit point to the transition zone.44-46) With oligodendrocyte-derived myelin, the REZ is structurally weaker and more vulnerable to the influence of vascular compression.47,48) Additionally, the REZ of the healthy facial nerve is ensheathed by only the arachnoid membrane and lacks interfascicular connective tissue that usually separates the fibers and epineurium.47,49) These anatomical characteristics might make the REZ slightly more vulnerable to injury by vascular compression.50) This supports the observation of the greater frequency of the AICA as the offending vessel causing compression of the anatomically fragile REZ in the polyphasic group, in which demyelination was observed to be more strongly involved.

Correlation between demyelination of the facial nerve and delayed cure from HFS after MVD

Based on the current understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying HFS, vascular compression of the facial nerve seems to play a crucial role in HFS.3) Previous studies have suggested that irritation of the facial nerve due to its close contact with a blood vessel promotes hyperactivity and hyperexcitability of the facial nerve nucleus.51) As in previous reports,20) no correlation was found between the intraoperative AMR disappearance rate and outcomes at 1 year in this study, suggesting that hyperexcitability of the facial nucleus might normalize progressively over several months or even years after MVD. This process of normalizing the hyperexcitability of the nucleus is thought to manifest as delayed cure of HFS.52,53) In addition to these theories, we suggest that demyelination of the facial nerve at the vascular compression site might enhance the excitability of the facial muscles, leading to impulse propagation from the facial nucleus to lower threshold motor neurons of the facial nerve.

There are some limitations to this study. First, since this was a retrospective study with a small sample size, further studies with a larger sample size are required to confirm our results. Second, we evaluated residual postoperative HFS 1 week, 1 month, and 1 year after the surgery. We need to accumulate more detailed follow-up data to determine the appropriate timing for evaluation of delayed cure after MVD.

Conclusion

There is a significant correlation between delayed relief after MVD and polyphasic morphology of the initial AMR in patients with hemifacial spasm.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

No company had influence on or knowledge of the results of this study.

References

- 1).Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, Shields PT, Larkins MV, Jho HD: Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 82: 201-210, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Auger RG: Hemifacial spasm: clinical and electrophysiologic observations. Neurology 29: 1261-1272, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Jannetta PJ, Abbasy M, Maroon JC, Ramos FM, Albin MS: Etiology and definitive microsurgical treatment of hemifacial spasm: operative techniques and results in 47 patients. J Neurosurg 47: 321-328, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Jannetta PJ: Hemifacial spasm: treatment by posterior fossa surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 41: 465-466, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Møller AR: Interaction between the blink reflex and the abnormal muscle response in patients with hemifacial spasm: results of intraoperative recordings. J Neurol Sci 101: 114-123, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Møller AR: The cranial nerve vascular compression syndrome: I. A review of treatment. Acta Neurochir 113: 18-23, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Huang CI, Chen IH, Lee LS: Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: analyses of operative findings and results in 310 patients. Neurosurgery 65: 53-56, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Illingworth RD, Porter DG, Jakubowski J: Hemifacial spasm: a prospective long-term follow up of 83 cases treated by microvascular decompression at two neurosurgical centres in the United Kingdom. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 60: 72-77, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Samii M, Günther T, Iaconetta G, Muehling M, Vorkapic P, Samii A: Microvascular decompression to treat hemifacial spasm: long-term results for a consecutive series of 143 patients. Neurosurgery 50: 712-718, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Huh R, Han IB, Moon JY, Chang JW, Chung SS: Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: analyses of operative complications in 1582 consecutive patients. Surg Neurol 69: 153-157, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Shibahashi K, Morita A, Kimura T: Surgical results of microvascular decompression procedures and patient's postoperative quality of life: review of 139 cases. Neurol Med Chir 53: 360-364, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Mizobuchi Y, Muramatsu K, Ohtani M, et al. : The current status of microvascular decompression for the treatment of hemifacial spasm in Japan: an analysis of 2907 patients using the Japanese diagnosis procedure combination database. Neurol Med Chir 57: 184-190, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Hatayama T, Kono T, Harada Y, et al. : Indications and timings of re-operation for residual or recurrent hemifacial spasm after microvascular decompression: personal experience and literature review. Neurol Med Chir 55: 663-668, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Hatem J, Sindou M, Vial C: Intraoperative monitoring of facial EMG responses during microvascular decom pression for hemifacial spasm. Prognostic value for long-term outcome: a study in a 33-patient series. British J Neurosurg 15: 496-499, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Ishikawa M, Nakanishi T, Takamiya Y, Namiki J: Delayed resolution of residual hemifacial spasm after microvascular decompression operations. Neurosurgery 49: 847-854, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Kim CH, Kong DS, Lee JA, Park K: The potential value of the disappearance of the lateral spread response during microvascular decompression for predicting the clinical outcome of hemifacial spasms: a prospective study. Neurosurgery 67: 1581-1587, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Kong DS, Park K, Shin BG, Lee JA, Eum DO: Prognostic value of the lateral spread response for intraoperative electromyography monitoring of the facial musculature during microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 106: 384-387, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Shin JC, Chung UH, Kim YC, Park CI: Prospective study of microvascular decompression in hemifacial spasm. Neurosurgery 40: 730-734, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Terasaka S, Asaoka K, Yamaguchi S, Kobayashi H, Motegi H, Houkin K: A significant correlation between delayed cure after microvascular decompression and positive response to preoperative anticonvulsant therapy in patients with hemifacial spasm. Neurosurg Rev 39: 607-613, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Tobishima H, Hatayama T, Ohkuma H: Relation between the persistence of an abnormal muscle response and the long-term clinical course after microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm. Neurol Med Chir 54: 474-482, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Møller AR: Hemifacial spasm: ephaptic transmission or hyperexcitability of the facial motor nucleus? Exp Neurol 98: 110-119, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Møller AR: The cranial nerve vascular compression syndrome: II. A review of pathophysiology. Acta Neurochir 113: 24-30, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Asayama B, Noro S, Abe T, Seo Y, Honjo K, Nakamura H: Sequential change of facial nerve motor function after microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: an electrophysiological study. Neurol Med Chir 61: 461-467, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Kim HR, Rhee DJ, Kong DS, Park K: Prognostic factors of hemifacial spasm after microvascular decompression. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 45: 336-340, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Sekula RF, Bhatia S, Frederickson AM, et al. : Utility of intraoperative electromyography in microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: a meta-analysis. Neurosurg Focus 27: E10, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Hirono S, Yamakami I, Sato M, et al. : Continuous intraoperative monitoring of abnormal muscle response in microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm; a real-time navigator for complete relief. Neurosurg Rev 37: 311-319, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Ishikawa M, Ohira T, Namiki J, Ajimi Y, Takase M, Toya S: Abnormal muscle response (lateral spread) and F-wave in patients with hemifacial spasm. J Neurol Sci 137: 109-116, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Ishikawa M, Ohira T, Namiki J, Gotoh K, Takase M, Toya S: Electrophysiological investigation of hemifacial spasm: F-waves of the facial muscles. Acta Neurochir 138: 24-32, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Ishikawa M, Ohira T, Namiki J, Ishihara M, Takase M, Toya S: F-wave in patients with hemifacial spasm: observations during microvascular decompression operations. Neurol Res 18: 2-8, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Kuroki A, Møller AR: Facial nerve demyelination and vascular compression are both needed to induce facial hyperactivity: a study in rats. Acta Neurochir 126: 149-157, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Micheli F, Scorticati MC, Gatto E, Cersosimo G, Adi J: Familial hemifacial spasm. Mov Disord 9: 330-332, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Griffin JW, Li CY, Ho TW, et al. : Guillain-Barré syndrome in northern China: the spectrum of neuropathological changes in clinically defined cases. Brain 118: 577-595, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Bouchard C, Lacroix C, Planté V, et al. : Clinicopathologic findings and prognosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neurology 52: 498-503, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Kuwabara S, Ogawara K, Misawa S, Mori M, Hattori T: Distribution patterns of demyelination correlate with clinical profiles in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 72: 37-42, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Kuwabara S, Yuki N: Axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome: concepts and controversies. Lancet Neurol 12: 1180-1188, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Uncini A, Kuwabara S: The electrodiagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome subtypes: where do we stand? Clin Neurophysiol 129: 2586-2593, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Kameyama S, Masuda H, Shirozu H, Ito Y, Sonoda M, Kimura J: Ephaptic transmission is the origin of the abnormal muscle response seen in hemifacial spasm. Clin Neurophysiol 127: 2240-2245, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Bostock H, Sears TA: The internodal axon membrane: electrical excitability and continuous conduction in segmental demyelination. J Physiol 280: 273-301, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Bostock H, Sherratt RM, Sears TA: Overcoming conduction failure in demyelinated nerve fibres by prolonging action potentials. Nature 274: 385-387, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Burke D, Kiernan MC, Bostock H: Excitability of human axons. Clin Neurophysiol 112: 1575-1585, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Kocsis JD, Waxman SG: Absence of potassium conductance in central myelinated axons. Nature 287: 348-349, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Jiang C, Liang W, Wang J, et al. : Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm associated with distinct offending vessels: a retrospective clinical study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 194: 105876, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Naraghi R, Tanrikulu L, Troescher-Weber R, et al. : Classification of neurovascular compression in typical hemifacial spasm: three-dimensional visualization of the facial and the vestibulocochlear nerves. J Neurosurg 107: 1154-1163, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Campos-Benitez M, Kaufmann AM: Neurovascular compression findings in hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg 109: 416-420, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Eidelman BH, Nielsen VK, Møller M, Jannetta PJ: Vascular compression, hemifacial spasm, and multiple cranial neuropathy. Neurology 35: 712-716, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Guclu B, Sindou M, Meyronet D, Streichenberger N, Simon E, Mertens P: Cranial nerve vascular compression syndromes of the trigeminal, facial and vago-glossopharyngeal nerves: comparative anatomical study of the central myelin portion and transitional zone; correlations with incidences of corresponding hyperactive dysfunctional syndromes. Acta Neurochir 153: 2365-2375, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).De Ridder D, Møller A, Verlooy J, Cornelissen M, De Ridder LD: Is the root entry/exit zone important in microvascular compression syndromes? Neurosurgery 51: 427-433, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48).Yee GT, Yoo CJ, Han SR, Choi CY: Microanatomy and histological features of central myelin in the root exit zone of facial nerve. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 55: 244-247, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Lu AY, Yeung JT, Gerrard JL, Michaelides EM, Sekula RF Jr, Bulsara KR: Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. ScientificWorldJournal 2014: 349319, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Ziyal IM, Özgen T: Microanatomy of the central myelin-peripheral myelin transition zone of the trigeminal nerve. Neurosurgery 60: E582, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Nielson VK: Electrophysiology of the facial nerve in hemifacial spasm: ectopic/ephaptic excitation. Muscle Nerve 8: 545-555, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Esteban A, Molina-Negro P: Primary hemifacial spasm: a neurophysiological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 49: 58-63, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Valls-Sole J, Tolosa ES: Blink reflex excitability cycle in hemifacial spasm. Neurology 39: 1061-1066, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]