Abstract

Background

Patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery may require a blood transfusion. However, blood transfusions are associated with postoperative complications and long-term oncologic outcomes. Patient blood management (PBM) is an evidence-based multimodal approach for blood transfusion optimisation. We sought to investigate the effects of PBM implementation in blood transfusion practice and on short-term postoperative outcomes.

Materials and methods

This study retrospectively reviewed data from 2,080 patients who had undergone colorectal cancer surgery at a single centre from 2015 to 2020. PBM was implemented in 2018, and outcomes were compared between the pre-PBM (2015–2017) and the post-PBM (2018–2020) periods.

Results

A total of 951 patients in the pre-PBM group and 1,129 in the post-PBM group were included. The transfusion rate of the total number of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) used decreased after PBM implementation (16.3 vs 8.3%; p<0.001). The rate of appropriately transfused PRBCs increased from the pre-PBM period to the post-PBM period (42 vs 67%; p<0.001). There was no significant difference in rates of complications between the two groups (23.0 vs 21.5%; p=0.412); however, a reduction in both anastomosis leakage (5.8 vs 3.7%; p=0.026) and the length of stay after surgery (LOS) (10.3±11.2 vs 8.2±5.7 days; p<0.001) was reported after PBM implementation.

Discussion

The PBM programme optimised the transfusion rate in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Implementation of the PBM programme had a positive effect on postoperative length of stay and anastomosis leakage while no increase in the risk of other complications was reported.

Keywords: Patient Blood Management, transfusion, colorectal cancer surgery

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is a common procedure among hospitalised patients1. Surgical patients are more likely to receive a blood transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) due to a greater prevalence of pre-existing or acquired anaemia, which can lead to reduced oxygen delivery, a worsening of tissue hypoxia, and impaired wound healing2,3. Despite the benefit of ensuring appropriate oxygen delivery to body tissues, PRBC transfusion is not without risks. PRBC transfusion promotes a systemic inflammatory response in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery and is associated with increased postoperative complications, including anastomotic leakage4,5.

Packed red blood cell transfusion also negatively affects long-term outcomes (overall survival and cancer-specific survival) in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery4,6–8. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to balance the risks and benefits of blood transfusion.

A large proportion of blood transfusions are inappropriately administered1,9, with patients receiving PRBCs despite a pre-transfusion haemoglobin (Hb) concentration of ≥8 mg/dL (an inadequate Hb trigger)9,10, while some are “over-transfused” with a resulting Hb concentration of ≥9 mg/dL (an inadequate Hb target)11.

A Patient Blood Management (PBM) programme was introduced at our institute to reduce unnecessary blood transfusions and optimise these procedures. PBM for surgical patients is based on three factors: optimisation of the preoperative red cell mass, minimising blood loss, and the correct management of postoperative anaemia. These are the three pillars of Patient Blood Management according to the World Health Assembly12. PBM is an evidence-based multimodal approach that aims to improve patient outcomes and safety by encouraging the practice of evidence-based blood transfusion criteria through an institutional protocol. Several previous studies have reported that implementation of a PBM programme is a safe and effective method to reduce the transfusion rate1,13–18.

Improving patient outcomes is the primary goal of PBM. In addition, the current shortage in blood supply due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic further highlights the importance of optimising blood transfusion protocols19,20. Restrictions on movement to prevent the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, the fear of exposure to the virus in medical facilities, and the increase in infected patients have led to a decrease in blood donations, stretching the available blood supply even thinner. In the United States, Shander et al. reported 130,000 fewer blood donations in just a few weeks due to the COVID-19 pandemic21. In South Korea, according to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total number of blood donations in July 2020 decreased by about 5.1% compared to those recorded in July 2019. To minimise the negative consequences of blood shortages and transfusion-related side effects, a reduction in improper transfusions is required, and this increases the need for PBM.

The present study aims to investigate the effects of the implementation of a PBM programme on the appropriateness of PRBC transfusion and the short-term postoperative outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery patients. In addition, we sought to evaluate the association between blood transfusion and short-term surgical outcomes when a PBM was not adopted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This was a retrospective study which evaluated a consecutive series of patients who had undergone colorectal cancer surgery from January 2015 to December 2020 at a tertiary referral centre (Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, South Korea). The necessary data were extracted from a prospectively maintained colorectal cancer database. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) colorectal resection; 2) elective surgery; 3) histological evidence of adenocarcinoma; and 4) no previous history of colorectal cancer. Exclusion criteria were: 1) emergency surgery; 2) transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) or transanal excision (TAE), i.e., surgical interventions that consist of local mass excision with a transanal approach; 3) hereditary colorectal cancer; 4) history of inflammatory bowel disease; 5) combined resection of other major organs (i.e., lungs and liver); 6) history of bone marrow-related disease; and 7) history of chronic renal failure. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Korea University Anam Hospital (approval n. 2021AN034).

Korea University Anam Hospital launched the Minimal Blood Transfusion Task Force team in January 2018 together with the PBM system and opened the Bloodless Medicine and Surgery Center in October 2018. As part of the PBM, the transfusion management computer programme was updated according to the Blood Transfusion Guidelines (2016, version 4) of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency to prescribe blood transfusions according to specific indications. These indications are: 1) last Hb level within five days <7 g/dL; 2) Hb ≤10 g/dL in patients with cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, or SaO2 < 90%; 3) cases following a massive transfusion protocol or of postpartum haemorrhage. As part of the procedure of prescribing a blood transfusion, the computer programme notified the physician through a pop-up window as to whether the transfusion indication was or was not appropriate. Since January 2018, several in-hospital meetings with each clinical department were held, together with continuous medical staff group discussions, in order to minimise the number of unnecessary blood transfusions.

After the PBM system had been introduced in January 2018, patients who had undergone surgery from January 2015 to December 2017 were defined as the pre-PBM group and those who went on to undergo surgery from January 2018 to December 2020 were defined as the post-PBM group, respectively. Data related to patient demographics, past medical history, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, tumour location, pathological tumour stage (according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] staging system), surgical approach, operation time, estimated blood loss, Hb before transfusion, and the number of blood transfusions were all analysed.

The definition of perioperative blood transfusion was a transfusion of PRBCs that occurred between 30 days before and 30 days after surgery. The preoperative Hb level was determined from the results of the last blood analysis performed before surgery. Preoperative anaemia was confirmed through a blood test performed by a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon for routine evaluation before surgery and defined according to the World Health Organization guidelines as Hb <13 mg/dL for male patients or <12 mg/dL for female patients, respectively22. Preoperative iron supplementation was given by oral or intravenous routes within one month before surgery. The criteria of oral or intravenous iron administration were not clear, but intravenous iron was administered in many cases. In the case of severe anaemia, evaluation and correction were performed in co-operation with a haematologist.

To investigate the appropriate transfusion rate of PRBCs, Hb level and the number of PRBC units received were measured at the time of transfusion for each patient. Postoperative complications were analysed to compare the short-term postoperative outcomes between the two groups (pre- and post-PBM). Surgical site infection, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, postoperative bleeding, anastomosis leakage, reoperation or readmission within 30 days after surgery, and 30-day mortality were compared, respectively. The Clavien-Dindo classification23 was used to evaluate the severity of complications. The relationship between transfusions and short-term postoperative outcomes was also evaluated. This study was performed according to the guidelines on Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology24.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics were summarised using basic descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation values and compared using a t-test on individual samples. For categorical data, the χ2 test was used and results were expressed as percentages. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics for Windows version 24.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

RESULTS

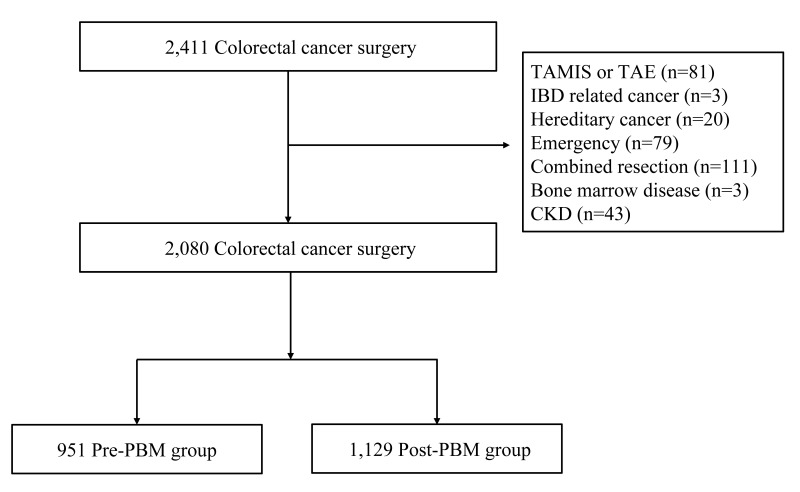

A total of 2,411 consecutive patients underwent colorectal cancer surgery from January 2015 to December 2020. A total of 2,080 patients satisfied the inclusion and exclusion requirements and were enrolled in this study: 951 patients in the pre-PBM group and 1,129 in the post-PBM group (Figure 1). Patients, tumour, and surgical baseline characteristics are reported in Table I. There was no difference between the two groups regarding age (p=0.489) or sex (p=0.376). The post-PBM group had a higher hypertension rate (p<0.001) and ASA scores (p<0.001). The rest of the demographic data were similar between the two groups. The surgical approach and volumes of intraoperative blood loss were also similar between the two groups, but surgery time was longer in the pre-PBM group than in the post-PBM group (197.0±77.4 vs 188.0±71.8 min; p=0.006). Tumour location, stage, and neoadjuvant treatment rate were similar between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Patient selection

TAMIS: transanal minimally invasive surgery; tae: transanal excision; CKD: chronic kidney disease; PBM: patient blood management.

Table I.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Variable | Pre-PBM (n=951) | Post-PBM (n=1,129) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.9±12.0 | 63.5±12.0 | 0.489 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.376 | ||

| Male | 585 (61.5) | 673 (59.6) | |

| Female | 366 (38.5) | 456 (40.4) | |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 23.8±3.5 | 23.6±3.7 | 0.420 |

| ASA score, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| <3 points | 887 (93.3) | 928 (82.2) | |

| ≥3 points | 64 (6.7) | 201 (17.8) | |

| HTN, n (%) | 348 (36.6) | 500 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| DM, n (%) | 179 (18.8) | 250 (22.1) | 0.062 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 59 (6.2) | 79 (7.0) | 0.469 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 21 (2.2) | 27 (2.4) | 0.782 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 59 (6.2) | 60 (5.3) | 0.384 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.194 |

| Approach, n (%) | 0.473 | ||

| Robotic | 219 (23.0) | 278 (24.6) | |

| Laparoscopic | 706 (74.2) | 824 (73.0) | |

| Open | 17 (1.8) | 13 (1.2) | |

| Conversion | 9 (0.9) | 14 (1.2) | |

| Operative time, min | 197.0±77.4 | 188.0±71.8 | 0.006 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 17.6±121.9 | 11.5±107.5 | 0.226 |

| Tumour location, n (%) | 0.747 | ||

| Right | 213 (22.4) | 274 (24.3) | |

| Left | 354 (37.2) | 420 (37.2) | |

| Rectum | 372 (39.1) | 421 (37.3) | |

| Multiple | 12 (1.3) | 14 (1.2) | |

| Pathologic stage, n (%) | 0.158 | ||

| 0 | 43 (4.5) | 76 (6.7) | |

| I | 194 (20.4) | 203 (18.0) | |

| II | 290 (30.5) | 358 (31.7) | |

| III | 282 (29.7) | 335 (29.7) | |

| IV | 141 (14.8) | 156 (13.8) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, n (%) | 163 (17.1) | 198 (17.5) | 0.811 |

ASA score: American Society of Anesthesiologists score; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; min: minutes; PBM: Patient Blood Management.

No differences were detected in preoperative Hb level or anaemia rate between the two groups (p=0.096 and p=0.059, respectively) (Table II). However, the transfusion rate has been halved since the introduction of PBM (16.3 vs 8.3%; p<0.001), and the rates of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative blood transfusions were also similarly distributed in both groups. Meanwhile, the rate of patients who received oral or intravenous iron supplements for anaemia has doubled since the introduction of PBM (3.3 vs 6.6%; p<0.001).

Table II.

Preoperative anaemia, iron replacement, and perioperative transfusion rate

| Variables | Pre-PBM (n=951) | Post-PBM (n=1,129) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Hb, g/dL | 12.7±1.8 | 12.5±1.7 | 0.096 |

| Anaemia, n (%) a | 400 (42.1) | 522 (46.2) | 0.059 |

| Transfusion, n (%) | 155 (16.3) | 94 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative, n (%)b | 99 (63.9) | 65 (69.1) | |

| Intraoperative, n (%)c | 18 (11.6) | 10 (10.6) | |

| Postoperative, n (%)d | 68 (43.9) | 34 (36.2) | |

| Preoperative iron, n (%) | 31 (3.3) | 75 (6.6) | <0.001 |

Anaemia was defined according to World Health Organization guidelines: men, haemoglobin (Hb) <13 g/dL; women, Hb <12 g/dL.

Patients received blood transfusion in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods.

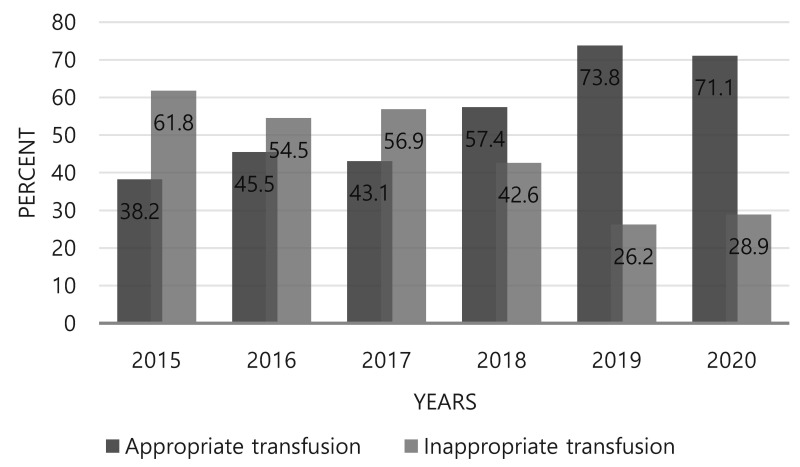

There was a significant difference in mean Hb threshold before transfusion between the pre- and post-PBM groups (8.5±1.3 vs 7.6±1.4 g/dL; p <0.001) ( Table III). The total number of transfused PRBC units decreased from 466 U before PBM to 306 U after PBM, but there was no difference in the number of PRBC units per patient between the two groups, with an average of 3 U given per patient (p=0.509). Among the total PRBC units transfused in the two groups, appropriately transfused PRBCs, according to the institutional transfusion criteria, totaled 195 out of 466 U (42%) in the pre-PBM group and 206 out of 306 U (67%) in the post-PBM group (p<0.001). The appropriate transfusion rate increased during the six years of the study period, from 38.2% in 2015 to 71.1% in 2020 (Figure 2).

Table III.

Appropriateness of packed red blood cell transfusion

| Variables | Pre-PBM (n=155)a | Post-PBM (*n=94)b | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean trigger Hb, g/dL | 8.5±1.3 | 7.6±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Total PRBC units | 466 | 306 | |

| PRBC units per patient | 3.0±2.2 | 3.2±2.7 | 0.509 |

| Appropriate transfusion, units (%) | 195/466 (42) | 206/306 (67) | <0.001 |

Patients transfused for each period. PRBC: packed red blood cell; PBM: Patient Blood Management.

Figure 2.

Appropriate transfusion rate in the Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery of Korea University Anam Hospital by year

No difference was detected in the rates of complications between the pre- and post-PBM groups (23.0 vs 21.5%; p=0.412) (Table IV). However, significant reductions in anastomotic leakage (5.8 vs 3.7%; p=0.026) and length of hospital stay after surgery (LOS) (10.3±11.2 vs 8.2±5.7 days; p<0.001) were detected. There was no significant difference in any of the other complications or their grading according to the Clavien-Dindo system between the two groups. Moreover, there was no difference in rates of repeated surgery, readmission, and mortality, all at 30 days, between the two groups.

Table IV.

Outcomes according to the Patient Blood Management (PBM) period

| Variables | Pre PBM (n=951) | Post PBM (n=1,129) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| All complications, n (%) | 219 (23.0) | 243 (21.5) | 0.412 |

| Anastomotic leakage, n (%) | 55 (5.8) | 42 (3.7) | 0.026 |

| Postoperative bleeding, n (%) | 12 (1.3) | 14 (1.2) | 0.964 |

| Surgical site infection, n (%) | 29 (3.0) | 37 (3.3) | 0.768 |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 7 (0.7) | 10 (0.9) | 0.706 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 8 (0.8) | 9 (0.8) | 0.911 |

| Clavien-Dindo grade | 0.359 | ||

| I | 51 (23.3) | 60 (24.7) | |

| II | 107 (48.9) | 124 (51.0) | |

| IIIa | 26 (11.9) | 27 (11.1) | |

| IIIb | 25 (11.4) | 29 (11.9) | |

| IV | 4 (1.8) | 3 (1.2) | |

| V | 6 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Length of stay after surgery, days | 10.3±11.2 | 8.2±5.7 | <0.001 |

| Reoperated within 30 days, n (%) | 27 (2.8) | 28 (2.5) | 0.611 |

| Readmission within 30 days, n (%) | 23 (2.4) | 36 (3.2) | 0.292 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.059 |

To evaluate any relationship between transfusions and short-term postoperative outcomes, the study dataset was divided into two groups according to whether patients had or had not received a transfusion, regardless of PBM. A total of 1,827 patients did not receive a transfusion (no-transfusion group), while 253 did receive a transfusion (transfusion group) (Online Supplementary Content, Table SI). The postoperative bleeding rate was higher in the transfusion group (p<0.001). Surgery-related complications were 2-fold higher in the transfusion group (39.5 vs 19.8%; p<0.001). Surgical site infection (p=0.002), urinary tract infection (p=0.029), pneumonia (p=0.003), anastomotic leakage (p<0.001), Clavien-Dindo complication grade (p<0.001), LOS (p<0.001), 30-day repeated surgery rate (p<0.001), and 30-day readmission rate (p=0.019) were higher in the transfusion group. There was no significant difference in 30-day mortality between the two groups (p=0.262).

DISCUSSION

This study confirms the positive impact of the PBM programme in optimising perioperative transfusion rates in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. The implementation of PBM was associated with a significant decrease in the perioperative transfusion rate and an increase in the rate of appropriate transfusions. PBM was significantly associated with anastomotic leakage and postoperative LOS. Moreover, transfusion was associated with postoperative morbidity, regardless of PBM.

The primary result of PBM implementation in this study was the significant reduction in the perioperative transfusion rate by reducing the rate of unnecessary transfusion and increasing the rate of preoperative iron supplementation. Optimising transfusion rates can prevent critical delays in caring for patients requiring essential transfusion and reduce medical costs25. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its consequent blood shortage, has reinforced the need for a PBM. The imbalance between blood supply and demand may push health care providers toward implementing a multimodal approach through PBM in order to ensure patient safety.

Previous studies have also confirmed that the introduction of PBM can reduce the number of unnecessary blood transfusions while maintaining patient safety. Gani et al. retrospectively evaluated the results of PBM implementation at a tertiary care hospital involving a large number of surgical patients (n=17,114)1 and confirmed an increase in the rate of “restrictive” transfusions (Hb trigger: <7 g/dL; p<0.001) and a decrease in the rate of “liberal” haemoglobin transfusions (Hb trigger: ≥8.0 g/dL; p<0.001). The authors also reported a decrease in the rate of “over-transfused” patients (target ≥9 or 10; p<0.001). After adjusting for relevant patient and disease characteristics, the implementation of the PBM programme was associated with 23% lower odds of receiving a blood transfusion (Odds Ratio: 0.77; 95% Confidence Interval: 0.657–0.896; p=0.001)1.

Similarly, in our study, PBM implementation also improved the quality of blood management. The rate of appropriate transfusions increased during the study period, from 38.2% in 2015 to 71.1% in 2020. Moreover, after PBM implementation, the optimal transfusion rate improved in all patients in the Korea University Anam Hospital, regardless of whether they underwent surgery or not26. These findings clearly demonstrate the positive role of evidence-based PBM in optimising blood transfusion procedures.

Optimising blood transfusion practices may have a significant impact on short-term postoperative outcomes. In a retrospective propensity score-matched study of colorectal cancer surgery patients, McSorley et al. reported that perioperative blood transfusion was associated with postoperative systemic inflammatory response (measured using C-reactive protein level), postoperative complications (p=0.017), anastomotic leakage (p=0.021), Clavien-Dindo grades III–V complications (p<0.001), and longer LOS (p=0.011), with no difference in rates of long-term survival (either overall survival or cancer-specific survival) in the matched groups4. In the current study, PBM implementation was associated with a significant reduction in anastomotic leakage (p=0.026) and LOS (p<0.001), with no improvement in other complications or 30-day mortality (p=0.059). However, when evaluating the relationship between blood transfusion and short-term surgical outcomes, blood transfusion was significantly associated with all complications, LOS, and repeated surgery and readmission within 30 days, but not with mortality. These results confirm the need to reduce the number of blood transfusions and optimise the related procedures to improve short-term outcomes in postoperative patients.

Several studies have confirmed the association between blood transfusion and postoperative infective complications27, anastomotic leakage8,28, and disease recurrence8,29 or survival29–32. Pang et al. also reported that poor overall survival was associated with blood transfusion volume8. However, Hanna et al. found that blood transfusion was not associated with a decrease in disease-free survival but was associated with worse overall survival and increased hospital LOS in patients undergoing curative rectal cancer resection33. Moreover, other authors did not find any independent impact of blood transfusion on recurrence of colorectal cancer when data were corrected for preoperative anaemia34–36. The relationship between blood transfusion and infective-oncologic outcomes has not yet been clearly established. It has been hypothesised that allogeneic blood transfusion might impair the host adaptive immune response, affecting the patient’s response to pathogens and circulating or micrometastatic tumour cells37. Another hypothesis is that the clinical condition in which blood transfusion is required may affect survival outcomes38. A long-term follow-up study is underway using the present study’s patient population to elucidate any relationship between blood transfusion and long-term oncologic outcomes.

When evaluating the current study, it must be reported that, even before the establishment of the PBM programme, the colorectal surgery department had attempted to minimise unnecessary blood transfusions. As a result of such active improvement efforts, since 2018, the Hb trigger has been reduced, with no impact on patients’ safety consequent to the reduction in the rate of blood transfusions. In addition, the threshold Hb (trigger Hb) in the pre-PBM phase was 8.5±1.3 g/dL, which is similar to or even better than that reported by other studies, highlighting the positive outcomes of any improvement in blood transfusion management8.

Blood transfusion procedures can be further improved in our department. In particular, this study showed that patients with transfusions received an average of 3 U of PRBCs (Table III). To improve this, it is feasible to update the current PBM guidelines, such as those regarding single-unit transfusions for patients without ongoing bleeding. It is expected that the current transfusion rate will be further improved by continuously improving the quality of the PBM programme in various ways. We believe that improving the transfusion rate will further improve clinical outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database; therefore, there could have been a degree of selection bias. Second, in determining whether a blood transfusion was appropriate, a patient’s Hb level and comorbidities could be verified through data analysis from the institutional database, but, in the case of transfusion due to ongoing bleeding, it was difficult to determine retrospectively whether the clinical condition at the time was an indication for transfusion. This could have led to an overestimation of the unnecessary blood transfusion rate. Third, as the study considered two different consecutive periods, surgical techniques and management between the two groups may have differed over time. Since this study compared before and after the introduction of PBM, inevitably it covered a long timeframe.

However, this study also has several strengths. First, the study series is relatively large. Second, the data of all patients included in this study were prospectively collected, and, in the case of blood transfusion due to ongoing bleeding, patients’ vital signs, estimated blood loss, and amount of drainage were examined to objectively judge the appropriateness of transfusion. Third, since 2012, postoperative morbidity and mortality data have been prospectively collected through weekly quality improvement meetings of our division and recorded in the colorectal database, ensuring high-quality data. Fourth, the majority of patients (97.2% in the pre-PBM and 97.6% in the post-PBM groups) underwent minimally invasive colorectal resections. Minimally invasive surgery is known to be associated with less perioperative blood loss and a reduced inflammatory response39–41. This could have affected the results of the current study, underestimating the possible effect of blood transfusion on short-term postoperative outcomes; this should be considered in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery, implementation of a PBM programme was associated with a decrease in the total transfusion rate, a decrease in the Hb threshold before transfusion (Hb trigger), and an increase in the optimal transfusion rate. Implementation of a PBM programme was also associated with a reduction in postoperative LOS and anastomosis leakage. Blood transfusion was associated with worse short-term postoperative outcomes, regardless of whether the PBM was operative or not.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J-MK had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gani F, Cerullo M, Ejaz A, et al. Implementation of a Blood Management Program at a tertiary care hospital: effect on transfusion practices and clinical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;269:1073–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu WC, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, et al. Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2007;297:2481–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.22.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1996;348:1055–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McSorley ST, Tham A, Dolan RD, et al. Perioperative Blood transfusion is associated with postoperative systemic inflammatory response and poorer outcomes following surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:833–43. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07984-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamini N, Deghi G, Gianotti L, et al. Colon Cancer surgery: does preoperative blood transfusion influence short-term postoperative outcomes? J Invest Surg. 2021;34:974–8. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2020.1731634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon HY, Kim BR, Kim YW. Association of preoperative anemia and perioperative allogenic red blood cell transfusion with oncologic outcomes in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:e357–66. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miki C, Hiro J, Ojima E, et al. Perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion, the related cytokine response and long-term survival after potentially curative resection of colorectal cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006;18:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang QY, An R, Liu HL. Perioperative transfusion and the prognosis of colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:7. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1551-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Kim Y, et al. Identifying variations in blood use based on hemoglobin transfusion trigger and target among hepatopancreaticobiliary surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y, Spolverato G, Lucas DJ, et al. Red Cell Transfusion Triggers and Postoperative Outcomes After Major Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:2062–73. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2926-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas DJ, Ejaz A, Spolverato G, et al. Packed red blood cell transfusion after surgery: are we “overtranfusing” our patients? Am J Surg. 2016;212:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Assembly, 63 ( 2010) Availability, safety and quality of blood products. World Health Organization; [Accessed on 10/08/2021]. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/3086. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver JC, Griffin RL, Hannon T, Marques MB. The success of our patient blood management program depended on an institution-wide change in transfusion practices. Transfusion. 2014;54:2617–24. doi: 10.1111/trf.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Osdol AD, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of an integrated transfusion reduction initiative in patients undergoing resection for colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2015;210:990–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.06.026. discussion 995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross I, Seifert B, Hofmann A, Spahn DR. Patient blood management in cardiac surgery results in fewer transfusions and better outcome. Transfusion. 2015;55:1075–81. doi: 10.1111/trf.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehra T, Seifert B, Bravo-Reiter S, et al. Implementation of a patient blood management monitoring and feedback program significantly reduces transfusions and costs. Transfusion. 2015;55:2807–15. doi: 10.1111/trf.13260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rineau E, Chaudet A, Chassier C, et al. Implementing a blood management protocol during the entire perioperative period allows a reduction in transfusion rate in major orthopedic surgery: a before-after study. Transfusion. 2016;56:673–81. doi: 10.1111/trf.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meybohm P, Herrmann E, Steinbicker AU, et al. Patient Blood Management is associated with a substantial reduction of red blood cell utilization and safe for patient’s outcome: a prospective, multicenter cohort study with a noninferiority design. Ann Surg. 2016;264:203–11. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gehrie EA, Frank SM, Goobie SM. Balancing Supply and Demand for Blood during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:16–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron DM, Franchini M, Goobie SM, et al. Patient blood management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1105–13. doi: 10.1111/anae.15095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shander A, Goobie SM, Warner MA, et al. Essential role of Patient Blood Management in a pandemic: a call for action. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:74–85. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Accessed on 23/08/2021]. (WHO/NMH/NHD/ MNM/11.1) Available at: http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ejaz A, Frank SM, Spolverato G, et al. Potential economic impact of using a restrictive transfusion trigger among patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:625–30. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin HJ, Kim JH, Park Y, et al. Effect of patient blood management system and feedback programme on appropriateness of transfusion: An experience of Asia’s first Bloodless Medicine Center on a hospital basis. Transfus Med. 2021;31:55–62. doi: 10.1111/tme.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohde JM, Dimcheff DE, Blumberg N, et al. Health care-associated infection after red blood cell transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1317–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, et al. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg. 2015;102:462–79. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amato A, Pescatori M. Perioperative blood transfusions for the recurrence of colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2006:CD005033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005033.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amri R, Dinaux AM, Leijssen LGJ, et al. Do packed red blood cell transfusions really worsen oncologic outcomes in colon cancer? Surgery. 2017;162:586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dent OF, Ripley JE, Chan C, et al. Competing risks analysis of the association between perioperative blood transfusion and long-term outcomes after resection of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:871–84. doi: 10.1111/codi.14970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akita K, Niga S, Yamato Y, et al. Anatomic basis of chronic groin pain with special reference to sports hernia. Surg Radiol Anat. 1999;21:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01635044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanna DN, Gamboa AC, Balch GC, et al. Perioperative blood transfusions are associated with worse overall survival but not disease-free survival after curative rectal cancer resection: a propensity score-matched analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:946–54. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, Warschkow R, et al. Blood transfusion does not adversely affect survival after elective colon cancer resection: a propensity score analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:841–9. doi: 10.1007/s00423-013-1098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warschkow R, Guller U, Koberle D, et al. Perioperative blood transfusions do not impact overall and disease-free survival after curative rectal cancer resection: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:131–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318287ab4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morner ME, Edgren G, Martling A, et al. Preoperative anaemia and perioperative red blood cell transfusion as prognostic factors for recurrence and mortality in colorectal cancer-a Swedish cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:223–32. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumberg N, Heal JM. Effects of transfusion on immune function. Cancer recurrence and infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Busch OR, Hop WC, Marquet RL, Jeekel J. Blood transfusions and local tumor recurrence in colorectal cancer. Evidence of a noncausal relationship. Ann Surg. 1994;220:791–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janez J, Korac T, Kodre AR, et al. Laparoscopically assisted colorectal surgery provides better short-term clinical and inflammatory outcomes compared to open colorectal surgery. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1217–26. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.56348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuk P, Simonsen RM, Komljen M, et al. Improved perioperative outcomes and reduced inflammatory stress response in malignant robot-assisted colorectal resections: a retrospective cohort study of 298 patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:155. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02263-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song XJ, Liu ZL, Zeng R, et al. A meta-analysis of laparoscopic surgery versus conventional open surgery in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15347. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.