Abstract

Silicone breast implants (SBIs) have been subject to scientific scrutiny since the 1960’s because of their potential link with systemic disease symptoms. Breast implant illness (BII) is a cluster of over 56 (systemic) symptoms attributed by patients to their SBIs. BII remains an unofficial medical diagnosis, although its symptoms include but are not limited to the clinical manifestations of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA). The aim of this study was to prospectively analyse the effect of explantation on clinical manifestations of ASIA/BII symptoms, as well as to compare (breast-surgery specific) QoL in patients pre- and postoperatively while recording relevant perioperative/patient data. A prospective cohort study was conducted on 140 patients consulting a single surgeon for explantation of SBIs at a single clinic from 2019 to 2021 via their general practitioner, a medical specialist or self-referral. Of all patients, medical (implant) history, lifestyle factors and biometric data were obtained. Patients filled out a novel ASIA/BII symptom-survey termed the ASIA-scale, three domains of the SF-36 and the augmentation module of the BREAST-Q before and four months after the operation. A total of 109 patients completed both the pre- and postoperative survey with a mean follow-up duration of 205 days. There was a significant decrease in all individual symptom scores as well as ASIA-scale summary scores after explantation (p < .001). All SF-36 subdomains showed significant improvement postoperatively (p < .001). The BREAST-Q subdomain ‘satisfaction with breasts’ improved significantly after explantation (p = .036). No statistically significant association was found between any clinical parameters (such as age, capsulectomy, rupture etc.) and the recovery of symptom scores. This is the largest prospective cohort study on SBI explantation to date showing significant improvement of the most common systemic complaints in SBI patients as well as improvement of satisfaction with breasts and overall quality of life.

Subject terms: Outcomes research, Immunology

Introduction

Silicone breast implants (SBIs) have been subject to scientific scrutiny since the 1960’s because of their potential link with systemic disease symptoms1–4. Breast implant illness (BII) is a cluster of over 56 (systemic) symptoms attributed by patients to their SBIs5–7. BII remains an unofficial medical diagnosis, although its symptoms include but are not limited to the clinical manifestations of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA)8,9. The clinical manifestations of ASIA are: myalgia or myositis, arthralgia and/or arthritis, chronic fatigue, neurological manifestations, cognitive impairment and pyrexia10. Interestingly, the many symptoms of BII also have overlap with, or even fully meet, the diagnostic criteria of chronich fatigue syndrome (CFS)11, fibromyalgia12, sarcoid-like disease and undifferentiated connective tissue disease (CTD)13,14. This overlap with defined diseases, as well as the large amount of women ascribing systemic symptoms to their SBIs5–7, make BII an entity that should be studied.

Disease management and study aim

The cornerstone of therapy for systemic symptoms in SBI patients appears to be explantation of SBIs, showing amelioration of symptoms in numerous studies15–18. Yet prospective studies are needed to evaluate the effect of explantation9,19,20. Clearly, further investigation is warranted into pre- and postoperative quality of life21, especially with the growing popularity of autologous fat grafting simultaneous with explantation19,22. Additionally, there is a need to record detailed patient history, lifestyle factors and relevant perioperative/patient data in explantation studies.

The aim of this study, therefore, was to prospectively analyse the effect of explantation on clinical manifestations of ASIA/BII symptoms, as well as to compare health-related and breast surgery-specific QoL in patients pre- and postoperatively while recording relevant perioperative/patient data. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the value of substitute cosmetic procedures such as autologous fat grafting on QoL and the effect several other clinical parameters on recovery of symptom scores.

Method

A prospective cohort study was conducted on all patients (n = 140) who underwent explantation of SBIs by a single surgeon at a single clinic (MITTSU Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) from January 2019 until September 2021. MITTSU Institute is a plastic surgery clinic that specializes in explantation of breast implants.

Patients were referred either by their general practitioner or a medical specialist after analysis for local and/or systemic complaints in relation to SBIs. Some came to the clinic by self-referral. All patients ascribing their symptoms to BII were considered for this study. We opted not to exclude those who opted for explantation for different reasons, resulting in a small control group. Hence, all patients opting for explantation after first consultation were included in this study.

At the clinic, detailed patient history was taken and a general assessment including physical examination was performed. Patient history (including implantation history) and current medication were obtained by anamnesis and via the referral letter of the general practitioner. Patients were interviewed by the surgeon with special attention given to implant related complaints, duration/onset of complaints, lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol and drug abuse) and allergies. Physical examination consisted of inspection/palpation of the prostheses, registering the corresponding Baker score23 and calculating patients BMI. All patients signed an informed consent form before enrolling in the study.

Surgical methods

Patients were consulted on explantation and additional subsequent surgical options such as autologous fat grafting and mastopexy. Patients who opted for autologous fat grafting and/or mastopexy did so using shared decision making. Patients were treated using a general sterile surgical technique. Explantation was performed using an existing or newly formed inframammary incision or through concurrent mastopexy if performed. Total or partial capsulectomy was performed in case of calcification or thickening of the periprosthetic capsule. In the case of silicone leakage resulting in silicone granuloma, the granuloma was completely excised. In the case of rupture, the surgical site was cleaned and disinfected using Hibicet® disinfectant. Implant exchange was not performed in the study group. If patients opted for autologous fat grafting, liposuction at various sites was performed, followed by mammary reintroduction via a layered technique using a blunt tip infiltration needle.

Numerous perioperative variables were recorded including: implant brand/size, occurrence of rupture (per side), abnormalities of the implant (disfiguration, aspect, disinfection), and if total or partial capsulectomy (per side), mastopexy or autologous fat grafting was performed.

Questionnaires

Patients were asked to complete three questionnaires pre- and postoperatively. The preoperative questionnaires were sent after the patient first presented. The postoperative survey was sent four months after the operation. A general reminder was sent in September and December of 2021 to those who failed to respond at the first postoperative evaluation.

The first questionnaire, hereafter described as the ASIA-scale, was developed by the surgeon of MITTSU clinic. This novel questionnaire of 19 items consists of the clinical manifestations of ASIA8 as well as the most commonly reported BII symptoms, based on expert opinion (see Appendix). The symptom intensity was rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (I haven’t experienced this symptom at all) to 4 (I have severely experienced this symptom). The second questionnaire is a truncated version of the SF-36 focussing on the subdomains ‘general health’, ‘physical functioning’ and comparison of ‘change of symptoms one year ago’. The SF-36 (previously RAND-36) is a comprehensive short-form generic profile HRQoL measure. Its validity has been well established in numerous patient populations24. The third and final questionnaire, the BREAST-Q, is a validated breast surgery-specific patient-reported outcome measure25. Three sub-domains were selected for evaluation, using the augmentation module: ‘satisfaction with breasts’, ‘sexual well-being’ and ‘psychosocial well-being’. The electronically administered BREAST-Q yields highly reliable, clinically meaningful data for use in clinical outcomes research26. The questionnaires were administered online, using SurveyMonkey (Bain & Company, Inc., Fred Reichheld and Satmetrix Systems, Inc., 1999–2021) which was set to generate an anonymous respondent ID used for matching the pre- and postoperative response.

Definitions

Patients who consulted for explantation for reasons other than BII or professionally established ASIA were termed ‘asymptomatic’, whereas those suffering from BII or ASIA were termed ‘symptomatic’. ‘Duration of silicon exposure’ in years was defined as the number of years from the first implantation to the year of explantation. ‘Duration of BII symptoms’ was defined as the number of years from the moment the patients first experienced symptoms attributed to BII until the explantation. ‘Time to the onset of BII symptoms’ was calculated by subtracting the duration of symptoms from the duration of silicon exposure. ‘Recovery of ASIA symptoms’ was the difference between pre- and postoperative ASIA-scale summary score. The same calculation was made for improvement of SF-36 and BREAST-Q subdomains. Patients who experienced symptoms > 5 years were defined as a group with ‘long duration of symptoms’, the remaining patients formed ‘short duration of symptoms’ group.

Data analysis

The collected data were analysed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows 27.0, USA, 1994–2021). A power analysis (paired-t, two sided)27 was performed prior to the study (parameters: α = 0·05, β = 0·2, SD = 20, σd = 18, E = ·28)28. A sample size of 104 was calculated, concluding that the actual sample size (n = 140) gives a satisfactory probability of giving a correct rejection of the null hypothesis.

For the evaluation of perioperative data, implant data and other characteristics, descriptive statistics of the patient cohort are presented. Continuous variables such as age were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables such as rupture rate were reported as percentages. Questionnaire summary scores were converted into continuous variables (0–100 scores). In case of the BREAST-Q and SF-36, higher scores mean greater satisfaction or better QoL. Ordinal data such as individual survey questions were compared pre- and postoperatively using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Continuous variables were compared pre- and postoperatively using a paired-t analysis. When comparing continuous variables between groups using an independent samples t-test, Levene’s test was performed to assess homogeneity of variances. Uni- and multivariate associations (crude and adjusted) between various patient characteristics, (peri)operative and implant-related variables were estimated using Pearson’s (or Point-Biserial) correlation and linear regression coefficients for their impact on questionnaire outcomes. A significance level of p ≤ 0·05 was deemed statistically significant.

Ethics committee approval

All patients signed informed consent forms prior to enrolling in this study. Consent to publish was also obtained. Therefore, the study was approved by the METC VUMc (Ethics committee of VUMc, Amsterdam UMC). In our study we adhered to local guidelines and regulations regarding ethical care or research and consent from patients accordingly.

Results

A total of 140 patients underwent explantation surgery (without reimplantation) of SBIs between the beginning of 2019 and the end of 2021. Thirty-one patients (22%) did not respond to the postoperative questionnaires despite repeated requests. The postoperative survey was completed within a range of 88–670 days after explantation, with a mean value of 205 days.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study group, categorized by organ system or symptom group, are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study group (n = 140).

| Characteristic | Value | Percentage† |

|---|---|---|

| Age at time of surgery, mean ± SD in years (range) | 43.2 ± 10.6 (24–69) | NA |

| Medical history | ||

| Autoimmune, rheumatologic or connective tissue disease* | 11 | 7.9% |

| Other immune mediated diseases** | 4 | 2.9% |

| Functional somatic syndromes*** | 7 | 5.0% |

| Thyroid disease♣ | 11 | 7.9% |

| Cardiovascular disease♣♣ | 9 | 6.4% |

| Respiratory disease♣♣♣ | 11 | 7.9% |

| Gastrointestinal disease*♣ | 9 | 6.4% |

| Skin disease**♣ | 6 | 4.3% |

| Musculoskeletal disease*♣♣ | 7 | 5.0% |

| Malignancy♣♣* | 6 | 4.3% |

| Psychiatric/psychological disorders♦ | 14 | 10.0% |

| Headaches♦♦ | 8 | 5.7% |

| Other♦♦♦ | 11 | 7.9% |

| Medication | ||

| Corticosteroids | 3 | 2.1% |

| Antihistamines | 7 | 5.0% |

| Analgesics | 8 | 5.7% |

| Biologicals | 2 | 1.4% |

| Levothyroxine | 8 | 5.7% |

| Statins | 2 | 1.4% |

| Inhalers | 9 | 6.4% |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 8 | 5.7% |

| Tryptans | 5 | 3.6% |

| Antidepressants | 14 | 10.0% |

| Benzodiazepines | 8 | 5.7% |

| Others° | 15 | 11.7% |

| Allergies | 57 | 40.7% |

| Lifestyle factors / intoxications | ||

| Alcohol (mild; 0–1 unit/day) | 32 | 22.9% |

| Alcohol (severe; 1–2 or more /day) | 7 | 5% |

| Smoking | 12 | 8.6% |

| Drugs (at least monthly) | 3 | 2.1% |

*SLE, Sarcoidosis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Lichen planus, Lichen sclerosus, Ehlers-Danlos, Vitiligo. **IgA deficiency, ITP, Still's disease, polyclonal IgM Syndrome. ***CFS, FM. ♣Hypo/hyperthyroidism. ♣♣Hypertension, Hypercholesterolaemia, Palpitations. ♣♣♣Asthma, COPD, rhinitis, sinusitis. *♣IBS, Ulcerating colitis, GERD. **♣Eczema, psoriasis, Lichen planus, Lichen sclerosus. *♣♣Arthritis, Disc herniation. ♣♣* Of which 2 breastcancer♦Depression, Burnout, ADHD, anorexia/bulimia. ♦♦Migraine, Tension headaches.♦♦♦Insomnia, CVA, braincyst, Lyme's disease, adverse reaction to dermatologic filler, Poland syndrome, Osteoporosis, polyneuropathy. °Of which 5 hormone replacement therapy and 1 methotrexate. †Percentage over total SBI population (n = 140). NA = Not applicable. Missing values for medication = 3, allergies = 7, lifestyle factors = 9.

Seventeen patients (12·1%) had a previous medical record of immune mediated disease. Six patients (4·3%) had previously been diagnosed with fibromyalgia and one patient (0·7%) had pre-existing chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Five patients (3·6%) had Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). A total of six patients (4·3%) had a prescription for immune modulating medication (corticosteroids, biologicals or methotrexate). A total of twenty-two patients (15·7%) chronically used psychoactive medication (i.e. antidepressants and benzodiazepines). Fifty seven patients (40·7%) were allergic to one or more substances. The three most occurring allergies were antibiotics (17%), specific foods/nuts (17%) and various types of pollen (15%).

Findings during physical examination and implant specific history are separately reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Findings during physical examination (n = 140).

| Finding | Value | Percentage* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, mean ± SD (range) | 22.4 ± 2.9 (17.5–30.8) | NA | ||

| Underweight (BMI < 20) | 25 | 17.9% | ||

| Overweight (BMI > 25) | 25 | 17.9% | ||

| Obese (BMI > 30) | 4 | 2.7% | ||

| Capsule type | Left | Right | Left | Right |

| Baker score 1 | 99 | 91 | 70.7% | 65% |

| Baker score 2 | 14 | 23 | 10% | 16.4% |

| Baker score 3 | 3 | 6 | 2.1% | 4.3% |

| Baker score 4 | 21 | 17 | 15% | 12.1% |

*Percentage over total SBI population (n = 140). NA = Not applicable. Missing values for capsule type = 17L, 3R; BMI = 7.

Table 3.

Implant specific history (n = 140).

| Characteristic | Value | Percentage* |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of silicone exposure, mean ± SD in years (range) | 14.4 ± 7.4 (1–46) | NA |

| Duration of BII symptoms, mean ± SD in years (range) | 6.2 ± 5.5 (0–26) | NA |

| Time to onset of symptoms, mean ± SD in years (range) | 7.0 ± 7.4 (0–30) | NA |

| Reimplantation | 41 | 29.3% |

| Once | 32 | 22.9% |

| Multiple | 9 | 6.4% |

| Implant size, mean ± SD in cc’s (range)† | 300.6 ± 76.1 (150–570) | NA |

| Reason for implantation | ||

| Cosmetic | 137 | 97.9% |

| Reconstructive | 3 | 2.1% |

| Implant type | ||

| Silicone | 134 | 95.7% |

| Saline | 6 | 4.3% |

| Implant brand | Allergan (31.8%), Mentor (16.2%), Eurosilicone (14.9%) | |

*Percentage over total SBI population (n = 140). NA = Not applicable. † 12 missing values.

Thirty-eight patients (25·7%) had capsular contracture (i.e. Baker 3 or 4; firm, deformed breast) of at least one breast. Only two patients had SBIs implanted for reconstructive purposes after breast cancer and one patient because of Poland syndrome29. Thirteen patients (9·3%) reported having no BII symptoms when consulting for explantation, and were termed asymptomatic. Of those thirteen, nine explanted for cosmetic reasons and four because of local complaints (of which two had MRI confirmed rupture, without systemic symptoms).

In forty-three patients (30·7%), the surgeon deemed it necessary to perform a capsulectomy (see Table 4). The majority of patients had an additional cosmetic procedure performed (92·8%), either mastopexy or autologous fat reconstruction.

Table 4.

Operative details and findings (n = 140).

| Finding/procedure | Value | Percentage* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rupture rate a priori | 20 | 14.2% | ||

| Right | 10 | 7.1% | ||

| Left | 5 | 3.6% | ||

| Bilaterally | 5 | 3.6% | ||

| Implant abnormalities | ||||

| Discoloration† | 18 | 12.9% | ||

| Excess fluid surrounding implant | 6 | 4.3% | ||

| Excess scar tissue/calcification | 4 | 2.8% | ||

| Intraoperative rupture | 3 | 2.1% | ||

| Siliconoma | 2 | 1.4% | ||

| Decrease in volume > 50 cc’s | 2 | 1.4% | ||

| Implant malposition/rotation | 2 | 1.4% | ||

| Capsulectomy | Left | Right | Left | Right |

| Partial | 21 | 22 | 15% | 15.7% |

| Total | 10 | 11 | 7.1% | 7.9% |

| Autologous fat reconstruction | 119 | 85% | ||

| Mastopexy | 11 | 7.9% | ||

*Percentage over total SBI population (n = 140). †17 of yellow aspect, 1 brownish discoloration. Total number of missing values = 0.

Primary outcome: effect of explantation

As can be seen in Table 5, the ASIA-scale summary score decreased significantly (i.e. condition improved) after explantation. For the asymptomatic patients who completed both pre- and postoperative surveys (n = 11), the mean score decreased from 28·3 to 21·6 after explantation (p = ·121). In the group of symptomatic patients (n = 98) the mean score decreased from 52·0 to 32·7 (p < ·001). The difference in reduction of ASIA summary scores between the symptomatic and asymptomatic group was statistically significant (p = ·012, equal variances not assumed).

Table 5.

Comparison of pre- vs. postoperative mean questionnaire (subdomain) summary scores (n = 109).

| Questionnaire | Preoperative (± SD) | Postoperative (± SD) | Mean difference (SE) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASIA | 49.5 (± 17.9) | 31.6 (± 17.2) | 17.9 (1.6) | < .001 |

| Satisfaction with breasts* | 57.9 (± 16.4) | 62.8 (± 21.7) | 4.9 (2.5) | .036 |

| Sexual wellbeing* | 59.7 (± 21.5) | 59.5 (± 21.7) | 0.2 (2.3) | .771 |

| Psychosocial wellbeing* | 59.8 (± 15.4) | 62.3 (± 17.4) | 2.5 (1.6) | .121 |

| General health♣ | 36.2 (± 22.2) | 48.3 (± 24.1) | 12.1 (2.2) | < .001 |

| Change vs. 1 year ago♣ | 36.3 (± 24.4) | 71.6 (± 25.4) | 35.3 (3.4) | < .001 |

| Physical health♣ | 76.9 (± 23) | 85 (± 23.2) | 8.1 (2) | < .001 |

†Paired samples t-test. *BREAST-Q subdomains: higher score indicates better QoL. ♣SF-36 subdomains: higher score indicates better QoL.

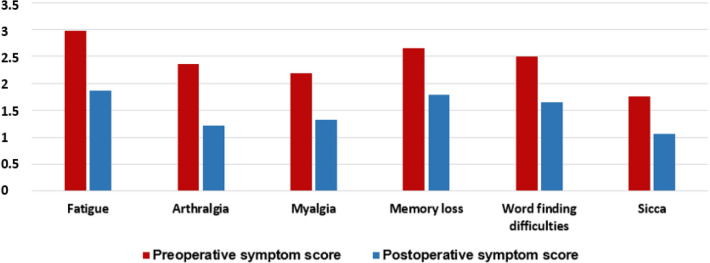

The ASIA questionnaire symptoms that were most frequently reported as a high score preoperatively (i.e. mean Likert score > 2 out of 4) were: fatigue (2·88), arthralgia (2·26), myalgia (2·06), memory loss (2·58), word finding difficulties (2·41), short tempered (2·21), back/neck pain (2·73), cold hands/fingers (2·33) and brain fog (2·31). No symptoms in the asymptomatic group scored a mean of > 2 before surgery. Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in all 19 individual ASIA questionnaire symptom scores when comparing pre- and postoperative data (p < ·001). Postoperative improvement of the ASIA-syndrome major criteria clinical manifestations for symptomatic patients, is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of preoperative vs. postoperative ASIA major criteria clinical manifestations mean symptom scores in the symptomatic group (n = 98) using Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test (p < .001).

Additionally, all SF-36 subdomain summary scores (‘general health’, ‘change from one year ago’ and ‘physical health’) increased significantly (i.e. QoL improved) from preoperative to postoperative. Of the BREAST-Q subdomains, only ‘satisfaction with breasts’ showed an increase after surgery (p = 0.0.36, Table 5). There were no differences in improvement after surgery in all SF-36 and BREAST-Q subdomains between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Secondary outcome: variables with effect on recovery

Several variables where evaluated for their effect on the recovery of symptoms, as is outlined in Table 6. There was no significant association between the performance of a capsulectomy (either partial or total) and recovery of ASIA-scale symptoms or improvement of general health (p = ·246) and physical health (p = ·972). There was also no difference between patients with an established autoimmune, rheumatologic or connective tissue disease or a functional somatic syndrome and patients without such illness, in recovery of symptoms (p = ·470). Yet, the postoperative ASIA-scale summary scores and SF-36 subdomain ‘general health’ scores were significantly higher (p = ·022) and lower (p = ·017) respectively in patients with these preexisting illnesses. Patients with a long duration of BII symptoms (i.e. > 5 years) had better recovery scores (p = ·017, equal variances assumed), while their preoperative ASIA-scale scores did not differ significantly compared with patients who experienced BII symptoms for less than 5 years (p = ·148).

Table 6.

Pearson’s or Point Biserial correlation and univariate linear regression coefficients of variables possibly affecting symptom recovery in relation to recovery of ASIA summary score*.

| Independent | Crude | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | B | CI | P value | |

| Age | −.110 | −.169 | −.48 to .15 | .289 |

| BMI | .079 | .418 | −.67 to 1.50 | .447 |

| Intoxications | −.112 | −3.75 | −10.2 to 2.75 | .255 |

| Allergies | .176 | 5.79 | −.529 to 12.1 | .072 |

| IMD/FSS group† | .071 | 2.78 | −4.83 to 10.4 | .470 |

| Implant rupture (before or during operation) | .032 | 1.47 | −7.54 to 10.5 | .747 |

| Implant size | .046 | .009 | −.031 to .050 | .649 |

| Capsular contracture on either side | −.138 | −4.79 | −11.5 to 1.94 | .161 |

| Duration of silicon exposure | −.010 | −.020 | −.422 to .383 | .923 |

| Time to onset of BII symptoms | −.128 | −.248 | −650 to .153 | .223 |

| Capsulectomy (partial or total) | −.061 | −2.10 | −8.78 to 4.58 | .543 |

*For population having completed both questionnaires (n = 109). R = correlation. B = regression coefficient. CI = confidence interval. †i.e. SLE, Sarcoidosis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Lichen planus, Lichen sclerosus, Ehlers−Danlos, Vitiligo, IgA deficiency, ITP, Still's disease, polyclonal IgM Syndrome, fibromyalgia, CFS, IBS. Dependent variable = recovery of ASIA-scale scores. R = correlation. B = regression coefficient. CI = confidence interval.ftab.

The improvement of QoL questionnaires was also found to have no association with performance of a capsulectomy, preexisting IMD/FSS, implant rupture/size, capsular contracture, time to onset of BII symptoms and duration of silicon exposure.

The duration of the follow up period was not significantly associated with either recovery of symptoms (p = ·874) or improvement of any QoL.

Discussion

The aim of this prospective, cohort study was the evaluation of the effect of explantation on systemic complaints in SBI patients, as well as the comparison of health-related and breast-surgery-specific quality of life, before and after the operation. Various clinical and surgical parameters were also assessed for their effect on the recovery of symptoms or improvement of quality of life.

It was found that all common BII symptoms reduced significantly after explantation. Others have retrospectively reviewed the effect of explantation17,18,30, but the potential influence of comorbidities was not always considered16. One previous study by Lee et al. did prospectively evaluate the effect of explantation compared with controls, with slightly shorter follow up and elaborate capsule analysis9. Despite differences in design and limitations, these studies report similar findings to this paper, showing amelioration of all common systemic symptoms in SBI patients.

These results can be explained by the main theory of BII pathophysiology: the immunological hypothesis, where SBIs are the chronic stimulus that causes overreaction of the immune system8,14,31. A similar overactive and sustained response, in the form of the foreign body reaction, is seen in capsular contracture31. This could explain why explantation leads to relatively swift reduction of all systemic symptoms, in this study with a mean recovery period of 205 days.

Yet a residual level of symptoms remains after explantation (33/100), indicating an ongoing or fading disease process. Although there was a significant difference in recovery of symptom scores between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, it should be noted that asymptomatic patients also had a residual symptom score (22/100). This is comparable to the findings of Colaris and Cohen Tervaert, suggesting that a particular group of SBI patients develop more severe complaints than the remaining SBI population33, which could be indicative of a psychological component14. This is in line with the current study, where memory loss, brain fog and word finding difficulties are among the highest rated symptoms. Moreover, Misere et al., have even found no significant difference in ASIA symptoms in women with SBIs compared to the general population21.

Furthermore, health-related quality of life improved across all subdomains. Misere et al. have compared health-related quality of life in SBI patients and healthy controls, finding lower QoL in women with SBIs21. Yet to our knowledge, validated QoL questionnaires have not yet been used to evaluate the effect of explantation.

Additionally, satisfaction with breasts improved significantly after explantation. This could potentially be due to the performance of additional cosmetic procedures such as mastopexy and autologous fat grafting. Autologous fat grafting has been previously studied directly after explantation, finding satisfaction in over 80% of patients. However, outcomes were evaluated with non-validated questionnaires34.

Interestingly, the results of this study could not identify any clinical parameters with a significant influence on recovery of symptoms. Even adjusted for age, BMI and smoking no significant association could be identified. This is at variance with the paper by Wee et al. which reported a more significant improvement of symptoms in patients with capsular contracture and obesity16. Wee et al. argue that the pro-inflammatory state of obesity and capsular contracture can contribute to the hyperactive immune response, and thus lead to better improvement after surgery. Notably, in the present cohort, only 16·4% had contracture, compared with 55·4% in Wee’s study, and, only four patients qualified as obese, potentially explaining the difference in results. Other explanations might be the unreliability of the Baker score23 or the fact that no adjustment was made for potential confounders in the retrospective study.

Still, it was found that postoperative symptom scores were significantly higher in patients with a previous history of immune mediated disease or a functional somatic syndrome. It has previously been reported that patients with autoimmune diagnoses improve less after explantation9.

Moreover, the fact that performance of a capsulectomy did not significantly influence the recovery of symptoms could indicate that the immunological hypothesis is not yet fully understood. It is possible that the foreign body reaction and loco-regional silicone migration are just one aspect of the problem.

One could further argue that social media influences5–7, next to psychological predisposition20,33 as already mentioned above, play a significant role in the eruption and severity of systemic symptoms in SBI patients. Interestingly, the duration of follow-up did not affect the recovery of symptoms, whereas a greater improvement would be expected after a longer follow-up period. Others even report no improvement of recovery from 30 days onward postoperatively16, raising the question as to whether homeostasis could have occurred so soon. Could psychological factors be of influence here? This could be the reason why only certain individuals report complete remission of symptoms.

A combination of the immunological and psychological hypotheses might lead to the development of additional treatment after surgery, leading to improved remission of symptoms in patients. Indeed a multifaceted approach to BII research, based on a clinical, external and psychological aspects, could fill the gaps in current knowledge of BII aetiology. Future efforts could focus on the interplay between psychological and immunological factors.

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study is the possibility of sampling bias, impacting the validity of the study. The majority of patients consulting MITTSU clinic for explantation were referred with ASIA or BII complaints. This raises the question whether the associated data are an accurate representation of the SBI population as a whole, as has been reported before21. Although, it is needless to say that sampling bias does not affect the results of this study for those actually reporting to have BII. Interestingly, the possibility of sampling bias supports the notion that a selected group of SBI patients experience more severe systemic symptoms, as already mentioned above.

Conclusion

This is the largest prospective cohort study on SBI explantation to date showing significant improvement of the most common systemic complaints in SBI patients as well as improvement of overall quality of life and satisfaction with breasts. Clinical parameters influencing the recovery of symptoms or improvement of quality of life could not be identified. Future research should focus on the immunological basis of breast implant illness possibly combined with a psychological assessment in order to provide additional treatment after explantation, to improve the level of residual symptoms with a prospect of complete remission.

Appendix

Instruction for the use and scoring of the novel ASIA-scale symptom survey

- Scoring of 5 point Likert-scale:

- 0 = I haven’t experienced this symptom at all

- 1 = I have rarely experienced this symptom

- 2 = I sometimes experience this symptom

- 3 = I have regularly experienced this symptom

- 4 = I have severely/constantly experienced this symptom

- Conversion to summary (continuous) scores:

- Convert Likert-scale scores to continuous scores per individual question (1 to 0, 2 to 25, 3 to 50 etc.)

- Average scores of symptoms most accurately resembling ASIA syndrome symptoms and multiply by 0.5

- Average scores of remaining symptoms and multiply by 0.5

- Add scores of steps 2 and 3 together to calculate ASIA-scale summary score

See Table 7.

Table 7.

Novel ASIA-scale symptom survey and respective weight for summary score.

| ASIA major criteria symptoms (50% of total score) | Additional BII symptoms (50% of total score) |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | Night sweats |

| Feelings of depression | |

| Myalgia | Chest pain/discomfort |

| Intolerance to specific food items | |

| Arthralgia | Newly developed allergies |

| Being short-tempered | |

| Memory loss | Alopecia |

| Skin abnormalities | |

| Word finding difficulties | Back/neck pain |

| Fungal infections | |

| Sicca/Pyrexia | Cold hands/fingers |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Brain fog |

Author contributions

G.R. B. (MD): data analysis, data management, literature research, writing original draft, editing and review of writing, interpretation of data, tables and figures, conceptualisation; F.B. N. (MD, PhD): data collection, study design, literature research, data analysis and interpretation, writing review and editing of original draft.

Funding

Both authors hereby declare not having had any financial incentive to publishing this work. No funding was received for conducting this study. G.R. Bird and F.B. Niessen.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. However, the dataset is still under review for analysis for current and soon to be published work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miyoshi K, Miyaoka T, Itakura T, et al. Hypergammaglobulinemia by prolonged adjucancity in man. Disorders developed after mammaplasty. Jap. Med. J. 1964;2122:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumagai Y, Abe C, Shiokawa Y. Scleroderma after cosmetic surgery: four cases of human adjuvant disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:532–537. doi: 10.1002/art.1780220514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisman MH, Vecchione TR, Albert D, Moore LT, Mueller MR. Connective-tissue disease following breast augmentation: A preliminary test of the human adjuvant disease hypothesis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1988;82:626–630. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198810000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahn EE, Garen PD, Silver RM, Maize JC. Scleroderma following augmentation mammoplasty: Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch. Dermatol. 1990;126:1198–1202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1990.01670330078011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healing Breast Implant Illness Facebook Group. ;([Accessed on 12/2/2021]; Available from: https://nl-nl.facebook.com/groups/Healingbreastimplantillness/about/).

- 6.Atiyeh, B., Emsieh, S. Breast Implant Illness (BII): Real Syndrome or a Social Media Phenomenon? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Aesth Plast Surg. 2021 Jul 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tang SYQ, Israel JS, Afifi AM. Breast implant ilness: symptoms, patient concerns and the power of social media. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017;140:765e–766e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoenfeld Y, Agmon-Levin N. 'ASIA' - Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. J. Autoimmun. 2011;36:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M, Ponraja G, McLeod K, Chong S. Breast implant illness: A biofilm hypothesis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2020;8(4):e2755. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watad A, Sharif K, Shoenfeld Y. The ASIA syndrome: Basic concepts. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2017;28(2):64–9. doi: 10.31138/mjr.28.2.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright CE. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An IOM report on redefining illness. JAMA. 2015;313(11):1101–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. 2016 Revisions of the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(3):319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreoli L, Angela T. Undifferentiated connective tissue disease, fibromyalgia and the environmental factors. Curr. Opin. Rheumtol. 2017;29(4):355–360. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S, Klietz M, Harren AK, Wei Q, Hirsch T, Aitzetmuller MM. Understanding breast implant illness: Etiology is the key. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021;197:1–8. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Boer M, Colaris M, van der Hulst RRWJ, Cohen Tervaert JW. Is explantation of silicone breast implants useful in patietns with complaints? Immunol. Res. 2017;65:25–36. doi: 10.1007/s12026-016-8813-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wee CE, Younis J, Isbester K, et al. Understanding breast implant illness, before and after explantation. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020;85(1):S82–S86. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maijers MC, de Blok CJM, Niessen FB, et al. Women with silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms: A descriptive cohort study. Neth. J. Med. 2013;71:534–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsnelson JY, Spaniol JR, Buinewicz JC, Ramsey FV, Buinewicz BR. Outcomes of implant removal and capsulectomy for breast implant illness in 248 patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2021;9(9):e3813. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnusson, M.R., Cooter, R.D., Rakhorst, H., McGuire, P.A., Adams, Jr. W.P., Deva, A.K. Breast Implant Illness: A Way Forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Mar; 143(3S A Review of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):74S-81S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Newby JM, Tang S, Faasse K, Sharrock MJ, Adams WP. Understanding breast implant illness. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021;41(2):1367–1379. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misere RML, Colaris MJL, Cohen Tervaert JW, van der Hulst RRJW. The prevalence of self-reported health complaints and health-related quality of life in women with breast implants. Aesthetic. Surg. J. 2021;41(6):661–668. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan J, Rohrich R. Breast implant illness: A topic in review. Gland Surg. 2021;10(1):430–443. doi: 10.21037/gs-20-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bakker E, Rots M, Buncamper ME, et al. The baker classification for capsular contracture in breast implant surgery is unreliable as a diagnostic tool. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020;146(5):956–962. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann. Int. Med. 2001;33(5):350–357. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen WA, Mundy LR, Ballard TNS, et al. The BREAST-Q in surgical research: A review of the literature 2009–2015. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2016;69:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuzesi S, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, Atisha D, Pusic AL. Validation of the electronic version of the BREAST-Q in the army of women study. Breast. 2017;33:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Winter JF, Dodou D. Five-point likert items: t test versus Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon (Addendum added October 2012) Practic. Assess., Res. Eval. 2010;15(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters SJ. Sample size and power estimation for studies with health-related quality of life oucomes: A comparison of four methods using the SF-36. Health and QoL Outc. 2004;2:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urschel HC. Poland's syndrome. Chest Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2000;10(2):292–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen Tervaert JW, Colaris MJ, van der Hulst RR. Silicone breast implants and autoimmune rheumatic diseases: Myth or reality. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017;29:348–354. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen Tervaert JW, Kappel RM. Silicone implant incompatibility syndrome (SIIS): A frequent cause of ASIA (Shoenfeld's syndrome) Immunol. Res. 2013;56:293–298. doi: 10.1007/s12026-013-8401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachour Y, Verweij SP, Gibbs S, et al. The aetiopathogenesis of capsular contracture: A systematic review of the literature. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2018;71(3):307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colaris, M.J.L., Cohen Tervaert, J.W., Ponds, R.W.H.M., Wilmink, J., van der Hulst, R.R.W.J. Subjective cognitive functioning in silicone breast implant patients: A cohort study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 9e3394 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Abboud MH, Dibo SA. Immediate large-volume grafting of autologous fat to the breast following implant removal. Aesthet. Surg. Jour. 2015;35(7):819–829. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. However, the dataset is still under review for analysis for current and soon to be published work.