Abstract

Mechanisms regulating neurogenesis involve broad and complex processes that represent intriguing therapeutic targets in the field of regenerative medicine. One influential factor guiding neural stem cell proliferation and cellular differentiation during neurogenesis are epigenetic mechanisms. We present an overview of epigenetic mechanisms including chromatin structure and histone modifications; and discuss novel roles of two histone modifiers, Ezh2 and Suv4-20h1/Suv4-20h2 (collectively referred to as Suv4-20h), in neurodevelopment and neurogenesis. This review will focus on broadly reviewing epigenetic regulatory components, the roles of epigenetic components during neurogenesis, and potential applications in regenerative medicine.

Key Words: adult neurogenesis, epigenetic, Ezh2, histone co-regulation, histone modification, neurodevelopment, neurogenesis, regenerative medicine, Suv4-20h

Overview of Epigenetic Mechanisms in the Context of Neurogenesis

Neurogenesis, neural stem cell proliferation, and cellular differentiation are broad and complex processes. The process of determining which cell type a neural stem cell will become involves genetic factors, epigenetic components, extrinsic signaling cues, and the microenvironment of a cell (Flitsch et al., 2020; Nasu et al., 2021). Exactly how intrinsic and extrinsic factors integrate to specify cell fate has long been a central question in biology (Schuurmans and Guillemot, 2002; Guillemot, 2007; McKenzie et al., 2019). The development of the nervous system requires fidelity in the expression of specific genes determining different neural cell types and is regulated, in part, by a multitude of intracellular signals interacting with the extracellular microenvironment temporally and spatially. These signals induce the expression of genes involved in lineage commitment, differentiation, maturation, migration, and cell survival (Lim et al., 2018). The silencing of genes responsible for the maintenance of stem cells in a pluripotent state and for cell fate decisions are important hallmarks of neurodevelopment. Intracellular effectors of neurogenesis including cell-cycle inhibitors (p16/INK4A and p21) and transcription factors have been previously reported. More recently, how epigenetic status influences neural stem cell proliferation and cellular differentiation during neurogenesis has become better characterized (Podobinska et al., 2017).

Epigenetic regulation is one of the most influential players in broad aspects of biology including neurogenesis. It is loosely described as heritable changes in gene expression without alterations in DNA sequence. The term “epi” means “over or above” and generally refers to changes associated with DNA, but not directly altering the nucleotide sequence of DNA. An important concept is each cell type has a distinctive epigenetic signature giving rise to a unique gene expression profile (transcriptome) (Lacal and Ventura, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Epigenetic regulation includes four main mechanisms to regulate gene expression levels within a cell: (1) DNA methylation; (2) histone post-translational modifications and histone variants; (3) non-coding RNAs and (4) higher order chromatin architecture (Podobinska et al., 2017). DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs are the best investigated epigenetic mechanisms, have been reviewed extensively, and will not be covered here. Neither will higher order chromatin architecture nor dynamic chromatin topology be discussed here. Cataloging large-scale chromatin features is a nascent research area with fewer studies evaluating potential roles in neurogenesis. Consequently, regulation via chromatin structure (DNA plus associated histone proteins) and its potential for directing neurogenesis will be the focus of this review.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The search strategy and selection criteria were limited to articles published in peer-reviewed journals articles. A literature review of articles was conducted by searching PubMed and Web of Science databases, updated until April 2022, searching for the following topics: histone modifications and neurogenesis, histone modifications and neurodevelopment, adult neurogenesis, EZH2, and KMT5C. The selected articles focused on histone modifications in the context of neurogenesis and neurodevelopment and basic and translational therapeutic applications of histone enzyme modulators.

Regulation of Intrinsic Cellular Processes by Histone Modifications

Within the nucleus of each cell, genomic DNA interacts with structural proteins to form chromatin. The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome. A nucleosome is comprised of 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped approximately 1.7 times in left-handed super-helical turns around a “core” of 8 histone proteins. The core is comprised of 4 related core histone proteins denoted H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Each core contains 2 copies of each core histone protein to form a histone octamer containing 2 H2A, 2 H2B, 2 H3, and 2 H4 proteins. The core histone proteins are arranged into an (H3-H4)2 tetramer flanked by two H2A-H2B dimers to form the cylinder-like “core” around which DNA wraps. Core histones contain a globular C-terminal domain and an N-terminal tail that extends away from a histone core (Podobinska et al., 2017).

The N-terminal tail of each core histone protein is the site of numerous post-translational modifications (PTMs). Each histone PTM is highly associated with a specific effect on chromatin structure and consequently influences the expression of nearby genes. Additionally, multiple modifications are often added concurrently and interact with one another in agnostic or antagonistic ways. The shear breadth of histone PTMs and the outcomes of different PTM combinations has led to the “histone code” hypothesis. This model states that different combinations of histone PTMs confer different chromatin states. A histone code suggests that each type of PTM can be recognized by one or more effector molecules. Such a hypothesis conceptually echo’s the view of the “genetic code” which provides rules to interpret linear sequences of DNA into genotypic information. Thus epigenetic modifications convey information about a chromatin state to transcriptional machinery (Baker, 2011). Indeed, recent evidence indicates that transcription factors not only recognize DNA sequence motifs but also read the epigenetic state of chromatin when initiating gene expression (Hughes and Lambert, 2017).

One mechanism of histone PTMs is regulating the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors and RNA polymerase binding. Histone cores and genomic DNA are not covalently bound together; the spatial relationship of histones and DNA is not static. Consequently, the cumulative electrochemical effects of multiple PTMs often displace histones along with DNA. Depending on the PTMs present, nucleosomes reversibly alternate between a form of chromatin with a high packing density (heterochromatin) and a form with low packing density (euchromatin). By altering combinations of histone PTMs within a genomic region, histone-modifying enzymes alter the structure of chromatin. Because the highly dense form of chromatin is inaccessible to DNA binding proteins, all genes contained within the region are often repressed. In contrast, the low nucleosome density associated with chromatin activation marks promotes opened chromatin and transcriptional activity. In sum, histone PTMs regulate gene expression by altering the accessibility of transcription proteins to DNA via reversibly switching between heterochromatin and euchromatin states that allows changing and resetting cell fate capability within germline cells and multipotent lineage progenitors, such as neural stem progenitor cells. These PTMs consist of acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination of histones (Podobinska et al., 2017). While the addition of acetyl groups to the aforementioned histone tails renders opened chromatin for activation, the site-specific addition of methyl groups can signify the active, poised, or repressed status of gene expression. For instance, tri-methylation at histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is associated with poised or active gene expression, whereas tri-methylations at histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and lysine 27 (H3K27me3) as well as at histone 4 lysine 20 (H4K20me3) suppress gene expression.

Histone methylation is the reversible process of transferring methyl groups onto the N-terminal tail of core histones, often at lysine or arginine residues. Up to three methyl groups are transferred onto an arginine or a lysine, respectively. Consequently, the two main classes of histone methyltransferases (HMTs) transfer a methyl group to lysine or arginine positions. Lysine-specific HMTs are further subdivided into SET domain HMTs and non-SET domain containing HMTs. The vast majority of HMTs are lysine-specific and part of the SET domain superfamily proteins. The SET domain is a large family of enzymes named after the first three HMTs identified in D. melanogaster: Suppressor of variegation 3–9 (Su(var)3-9), enhancer of zeste (E(z)), and trithorax (Trx) (Dillon et al., 2005; Bennett et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2020; Stirpe et al., 2021; Michurina et al., 2022). The catalytic mechanism of SET domain enzymes involves transferring a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine to a lysine residue of a histone tail. Ultimately, histone methylations are actively removed by one of two groups of lysine-specific demethylases (LSD). Members of the first group, LSD1, are flavin adenine dinucleotide dependent amine oxidases. Members of the second group, the Jumonji domain containing enzymes (JmJC) act as Fe(II)/ α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases and are further divided into seven subgroups: JHDM1, JHDM2, JHDM3/JMJD2, JARID, JMJC domain only, PHF2/PHF8 and UTX/UTY (Khare et al., 2012).

The remaining sections will focus on three chromatin modifiers relevant to regulating neuronal stem cell proliferation and/or differentiation and may represent therapeutic targets. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) catalyzes tri-methylation on histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3). Suppressor of variegation 4-20 homologs (KMT5B (human)/Suv4-20h1 (mouse) and KMT5C (human)/Suv4-20h2 (mouse)) catalyze tri-methylation on histone 4 lysine 20 (Suv4-20h/H4K20me3). Nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein (NSD) family, such as NSD1, which methylate H3K36. These enzymes have been well characterized in other tissues but may have novel roles in the brain or have clinical relevance in neuro-regeneration.

Histone Modifications Are Associated with Neurogenesis and Brain Tumors

In the embryonic and early postnatal brain, proliferative and multipotent neural stem cells generate neurons (neurogenesis) as well as glia including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (gliogenesis) (Semenov, 2019; Jurkowski et al., 2020; Kase et al., 2020; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2021). Gliogenesis starts during late embryogenesis and continues in postnatal stages throughout the adult brain (Gallo and Deneen, 2014). Neurogenesis begins from early embryonic development until early postnatal stages with only two neurogenic niches remaining active in the adult brain (Gotz and Huttner, 2005; Ming and Song, 2011; Paridaen and Huttner, 2014). Adult neurogenesis continues life-long in restricted brain regions including the subventricular zone (SVZ) adjacent to the lateral ventricles (Jessberger and Gage, 2014; Kempermann, 2014) and the subgranular zone (SGZ) within the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus (Paton and Nottebohm, 1984; Richards et al., 1992; Ming and Song, 2011). During cell fate transition in the SVZ, slowly dividing neural stem cells will give rise to active progenitors, and then neuroblasts. (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004; Ming and Song, 2011). The majority of neuroblasts in the rodent SVZ migrate through the rostral migratory stream and generate interneurons in the olfactory bulb (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004; Ihrie and Alvarez-Buylla, 2011; Ming and Song, 2011), whereas neuroblasts in the human SVZ form interneurons in the adjacent striatum (Ernst et al., 2014). The difference is most likely due to a limited reliance on olfaction for humans compared to rodents (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Collin et al., 2005; Ninomiya et al., 2006; Yamashita et al., 2006; Goritz and Frisen, 2012). In the SGZ within the DG, the radial glia-like cells and non-radial precursors give rise to intermediate progenitors, neuroblasts, and then mature neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Filippov et al., 2003; Kempermann et al., 2003; Kronenberg et al., 2003; Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004; Ming and Song, 2011).

The stepwise generation of functional neurons has highlighted that neural stem progenitor cells must maintain a gene expression pattern to promote their ability for self-renew and lineage commitment (Lim et al., 2009; Ming and Song, 2011). Several epigenetic mechanisms involving chromatin modifications have emerged as highly influential players on transcription that convey a global and heritable gene expression signature critical for neural stem progenitor cell function (Xie et al., 2013). For instance, in vivo mouse models have shown that epigenetic regulations by H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 are required for postnatal neurogenesis (Lim et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2014). Ezh2 deletion by crossing to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-Cre mouse line results in a deficit of postnatal neurogenesis in the mouse SVZ (Hwang et al., 2014). Using Nestin-CreERT2 and tamoxifen-inducible system to knockout Ezh2 in the SGZ/DG showed that Ezh2 is important for learning and memory capabilities in 6-week-old mice (Zhang et al., 2014).

The importance of histone regulation in the brain is perhaps most salient in pediatric and adult brain tumor cases. In pediatric patients, the lysine 20-to-methionine (K27M) mutation at one allele of H3F3A occurs in 60% of high-grade pediatric glioma cases, with median survival after diagnosis of approximately 1 year (Chan et al., 2013). In such cases, H3K27me3 and Ezh2 are dramatically increased in H3.3K27M patient cells, and targeting Ezh2 could be highly relevant to clinical applications. Similarly, a perturbed epigenome is often reported in glioblastomas in adult brain tumors, and increased EZH2/H3K27me3 have been reported as having the highest increase among histone modifications within MRI-classified SVZ-associated glioblastomas (Lin et al., 2017). However, the exact mechanisms and roles that various histone modifiers play in neurogenesis, neurodevelopment, and neurological diseases have yet to be fully characterized and are an active area of investigation.

Novel Roles of H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 in the Brain: Co-regulation by Ezh2/Suv4-20h in Hippocampal Development

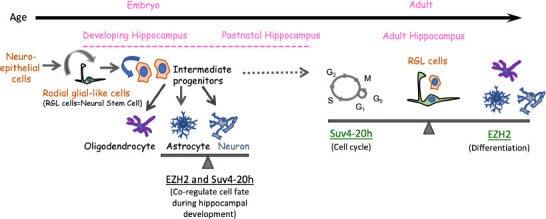

Histone modifiers likely act in a coordinated manner to regulate cellular processes and neuronal cell fate decisions. Recently, a report described the co-regulation of radial glial-like cells (RGLs; also known as neural stem cells) by two histone modifiers, which has shed more light on the role of histone modifications in cell fate transitions from RGLs to neurons or astrocytes. Chang et al. (2022) generated single knockouts of Ezh2 and Suv4-20h1/Suv4-20h2 (referred to here as Suv420h), as well as a double knockout of Ezh2/Suv4-20h in RGLs in the embryonic brain (Figure 1). The report found little to no effect on cell fate transitions in either Ezh2 knockout or Suv4-20h knockout. However, loss of both Ezh2 and Suv4-20h within Gfap-positive RGLs caused a dramatic defect in hippocampal development. This is the first demonstration of critical regulation by dual chromatin modifiers in neural stem cells that these two chromatin repressors collaboratively regulate genes involved in the cell cycle, differentiation, and the specification of neurons and astrocytes. As neuron-astrocyte interaction determines synaptic activity and functional neuronal circuit, teasing apart the complex relationship between neuron and astrocyte through epigenetic regulation will converge on key hubs with the potential to transform as stem cell technologies and subsequently translate into clinical therapies for the treatment of developmental or neurological diseases.

Figure 1.

Neural cell fate regulation by histone modifiers Ezh2 and Suv4-20h.

Ezh2 and Suv4-20h co-regulate neural cell fate decisions within Gfap positive Radial glial-like cells. Loss of both Ezh2 and Suv4-20h results in disruption of neural cell fate and a dramatic defect in hippocampal development (Chang et al., 2022). Such a change in cell fate was not observed in single knockouts of Ezh2 or Suv4-20h within the developing hippocampus. In the adult hippocampus, Ezh2 and Suv4-20h perform distinct roles within neural stem progenitor cells (Rhodes et al., 2018). In such a scenario, Ezh2 inhibits lineage commitment and differentiation, while Suv4-20h regulates the cell cycle in mitotic neural progenitors, ultimately regulating the rate of neurogenesis and neural cell fate. RGL: Radial glial-like. Unpublished data.

As the neural stem cell niche is highly heterogenous, proper characterization of the molecular signatures of critical cell types necessitates the use of single-cell sequencing methods. Single assay sequencing modalities, such as single-cell RNA-Seq, have proven invaluable for deconvolving molecular processes within cell types (Wester et al., 2019; Ekins et al., 2020; Alkaslasi et al., 2021; Mahadevan et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022). However, the complexity of stem cell niches and heterogeneity of cell types are well suited for the application of recently developed single-cell multiomics sequencing methods (Golomb et al., 2020; Allaway et al., 2021). Indeed, to characterize the Ezh2/Suv4-20h double knockout described by Chang et al. (2022), a novel single-cell sequencing method based on printed droplet microfluidics-based cell sorting, Drop-Sort, was used (Cole et al., 2017; Habib et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020b). Drop-Sort can quantify various cellular features while cells are sorted by microfluidics. The ability to characterize additional features while sorting single cells has enormous potential in expanding the types of cellular components that can be characterized by single-cell sequencing, furthering the high throughput capability to glean cell type signals from heterogeneous stem cell niches and complex tissue microarchitectures. Using this cutting-edge technology, the authors found that Ezh2/H3K27me3 and Suv4-20h/H4K20me3 c0-regulate developmentally critical genes required for the maintenance of undifferentiated mitotic neural stem progenitor cells possessing high cell fate capacity. Assessing potential modulators of Ezh2 and/or Suv4-20h may prove a useful method of reprogramming neural cell lineages or increasing neurogenic activity in the hippocampus.

Distinct Roles of Ezh2/Suv4-20h during Adult Neurogenesis

The individual roles of the histone modifiers Ezh2 and Suv4-20h had been characterized less in the adult brain, particularly in the adult SVZ and the DG of the hippocampus. A recent report utilized stereotaxic injection to administer peptide tagged-Cre protein into targeted brain regions, the SVZ and the DG, to assess the long-term in vivo effect of region-specific knockout of Ezh2 or Suv4-20h (Rhodes et al., 2018). The finding demonstrated distinct roles of two chromatin repressors; Ezh2 plays an important role in the maintenance of the neural stem progenitor cell population while Suv4-20h regulates the cell cycle in these adult neurogenic niches (Figure 1). This Cre protein-based approach presents a technical breakthrough that offers myriad tightly controlled knockouts in multiple cell types simultaneously for studying many other regulatory mechanisms and is optimal for region-specific manipulation within complex, heterogeneous tissue architectures.

Taken together, the roles of histone modifications in regulating hippocampal development and adult neurogenesis make these epigenetic mechanisms attractive therapeutic targets for neuronal regeneration, especially in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders (Pereira et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2016; Pursani et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2017).

Cross-regulation between EZH2/PRC2 and the Nuclear Receptor Binding SET Domain Protein Family of Histone H3K36 Methyltransferases Underlies the Mechanism of Oncohistone Mutations in Pediatric Gliomas

Histone H3.3 mutation (H3F3A) occurs in 50% of cortical pediatric high-grade gliomas, impairing H3K36me3, altered H3K27me3 enrichment, contributing to genomic instability and driving a distinct gene expression signature associated with tumorigenesis (Suzuki et al., 2017). Further, nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein 1 (NSD1) which catalyzes H3K36 methylation is frequently mutated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the sixth most common cancer by incidence, and a leading cause of cancer-related death (Brennan et al., 2017). NSD1 is also genetically or epigenetically deregulated (either inactivated or overexpressed) in several other cancer types. NSD1 is therefore among several epigenetic modifying enzymes (such as NSD2, DNMT3a, SETD2, and EZH2) that represent causative genes for developmental growth disorders that are also frequently mutated in cancer (Brennan et al., 2017).

NSD1 is a SET-domain containing histone methyltransferase, which catalyzes methylation of histone 3 at lysine 36 (H3K36). Intriguingly, H3K36 methylation is bound by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) which contains EZH2. This is done through accessory components PHF1 and PHF19 engaging H3K36 methylated regions with their Tudor motifs (Cai et al., 2013). In addition, the Hoxb5/Hoxb6 gene locus and differentiation-associated genes (Otx2, Hoxa5, Fgf15, and Meis1) are selectively H3K27me3 enriched by PRC2 via the Tudor domain of PHF1 and PHF15 (Suzuki et al., 2017). This suggests that indirect interactions between EZH2/PRC2 and the NSD family members co-regulate developmentally critical genes. Such interactions may also take place in adult forms of brain tumors, where increased enrichment of H3K27me3 and H3K36me3 co-occur in MRI-classified SVZ-associated glioblastomas (Lin et al., 2017).

The potential for crosstalk between EZH2/PRC2 and the NSD family of histone H3K36 methyltransferases is a very intriguing topic. Both histone modification families, the SET domain superfamily containing EZH2 and the NSD family, are very pertinent to neuronal development as well as neuronal stem cell proliferation, differentiation, and plasticity and likely represent pharmacological targets for drug discovery, either individually or in combination.

Current State of Pharmacotherapies for Altering Epigenetic Enzymes

Given the roles of histone modifications in regulating cell state, epigenetic drug targets are starting to reach their potential in translational and clinical applications. The potential use of drugs targeting histone deacetylases, histone acetyltransferase, and bromodomains have been proposed over the past decade to treat vascular diseases and more recently cancer therapies (Natarajan, 2011; Wu et al., 2020). Altering DNA methyltransferases activity has been reported to ameliorate neuroinflammation in mice (Matt et al., 2018) while several pharmaceutical companies have independently developed selective inhibitors of lysine methyltransferases (i.e. EZH2), lysine demethylases (i.e. LSD1), and bromodomains (i.e. BET (bromo and extra terminal) family) (Ganesan et al., 2019). Indeed, EPZ-6438 (Tazemetostat), an enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitor has been approved for clinical trials, blocks medulloblastoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo, prolongs survival in orthotopic xenograft models and leads to potent antitumor activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Knutson et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020a). In another study, the role of 2 novel EZH2 inhibitors was designed, prepared, and tested to determine their effects on primary glioblastoma cell cultures (Stazi et al., 2019). The EZH2 inhibitors impacted the primary glioblastoma cell viability, showing even stronger effects in combination with the chemotherapy temozolomide. These findings are promising and strongly motivate the further development of pharmacotherapies to alter epigenetic targets in regenerative medicine applications.

Discussion

Neurogenesis is prominent within SVZ during neurodevelopment and persists in the adult mammalian brain. In the other major neurogenic niche, the SGZ, recent controversy has cast doubt on whether adult neurogenesis occurs in the adult brain of humans. Evidence supporting a lack of neurogenesis includes histological data (Sorrells et al., 2018). However, a recent multi-species single-cell transcriptomic study has proposed that in the human hippocampus, DCX is not a specific marker of neuroblasts or immature granule neurons, and therefore may be inadequate to define adult neurogenesis in humans (Franjic et al., 2022). Whether adult neurogenesis in either the SVZ or SGZ is reduced or abundant in adult humans, both niches likely retain their regenerative and neurogenic potential. Consequently, reactivation of proneuronal genes within the SVZ or SGZ represents intriguing targets for treatments. Notably, the role of two histone modifiers, Ezh2 and Suv4-20h regulates proneuronal genes during stem cell fate decisions and represents an avenue for preprogramming neural stem cells. Importantly, the additive effect of loss of multiple histone modification enzymes represents an intriguing set of targets for developing epigenetic therapies. Indeed, a group recently reported a synthetic hybrid pharmacological agent that acts as a dual inhibitor of histone deacetylase 1/2 and LSD1, members of the REST corepressor complex (Kalin et al., 2018) known to coregulate neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and maturation (Maksour et al., 2020). These reports suggest that selective alteration in the activity of multiple epigenetic enzymes represents a potentially powerful tool for influencing cell fate transitions for regenerative medicine applications. Further, virtually all neuronal regeneration declines during aging and significantly reduces after radiation treatment for brain tumors. Given the reversible nature of epigenetics, the possibility to reprogram deleterious epigenetic modifications that occur with aging or after injury will have far-reaching impacts on the regenerative intervention.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Alkaslasi MR, Piccus ZE, Hareendran S, Silberberg H, Chen L, Zhang Y, Petros TJ, Le Pichon CE. Single nucleus RNA-sequencing defines unexpected diversity of cholinergic neuron types in the adult mouse spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2471. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22691-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaway KC, Gabitto MI, Wapinski O, Saldi G, Wang CY, Bandler RC, Wu SJ, Bonneau R, Fishell G. Genetic and epigenetic coordination of cortical interneuron development. Nature. 2021;597:693–697. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03933-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run:maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med. 2002;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nm747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker M. Making sense of chromatin states. Nat Methods. 2011;8:717–722. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett RL, Swaroop A, Troche C, Licht JD. The role of nuclear receptor-binding SET domain family histone lysine methyltransferases in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:a026708. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan K, Shin JH, Tay JK, Prunello M, Gentles AJ, Sunwoo JB, Gevaert O. NSD1 inactivation defines an immune cold, DNA hypomethylated subtype in squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17064. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai L, Rothbart SB, Lu R, Xu B, Chen WY, Tripathy A, Rockowitz S, Zheng D, Patel DJ, Allis CD, Strahl BD, Song J, Wang GG. An H3K36 methylation-engaging Tudor motif of polycomb-like proteins mediates PRC2 complex targeting. Mol Cell. 2013;49:571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan KM, Fang D, Gan H, Hashizume R, Yu C, Schroeder M, Gupta N, Mueller S, James CD, Jenkins R, Sarkaria J, Zhang Z. The histone H3.3K27M mutation in pediatric glioma reprograms H3K27 methylation and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2013;27:985–990. doi: 10.1101/gad.217778.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang KC, Rhodes CT, Zhang JQ, Moseley MC, Cardona SM, Huang SA, Rawls A, Lemmon VP, Berger MS, Abate AR, Lin CA. The chromatin repressors EZH2 and Suv4-20h coregulate cell fate specification during hippocampal development. FEBS Lett. 2022;596:294–308. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole RH, Tang SY, Siltanen CA, Shahi P, Zhang JQ, Poust S, Gartner ZJ, Abate AR. Printed droplet microfluidics for on demand dispensing of picoliter droplets and cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:8728–8733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collin T, Arvidsson A, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Quantitative analysis of the generation of different striatal neuronal subtypes in the adult brain following excitotoxic injury. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng X. The SET-domain protein superfamily:protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2005;6:227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekins TG, Mahadevan V, Zhang Y, D'Amour JA, Akgul G, Petros TJ, McBain CJ. Emergence of non-canonical parvalbumin-containing interneurons in hippocampus of a murine model of type I lissencephaly. Elife. 2020;9:e62373. doi: 10.7554/eLife.62373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst A, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Perl S, Tisdale J, Possnert G, Druid H, Frisen J. Neurogenesis in the striatum of the adult human brain. Cell. 2014;156:1072–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng X, Juan AH, Wang HA, Ko KD, Zare H, Sartorelli V. Polycomb Ezh2 controls the fate of GABAergic neurons in the embryonic cerebellum. Development. 2016;143:1971–1980. doi: 10.1242/dev.132902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filippov V, Kronenberg G, Pivneva T, Reuter K, Steiner B, Wang LP, Yamaguchi M, Kettenmann H, Kempermann G. Subpopulation of nestin-expressing progenitor cells in the adult murine hippocampus shows electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of astrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;23:373–382. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flitsch LJ, Laupman KE, Brustle O. Transcription factor-based fate specification and forward programming for neural regeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:121. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franjic D, Skarica M, Ma S, Arellano JI, Tebbenkamp ATN, Choi J, Xu C, Li Q, Morozov YM, Andrijevic D, Vrselja Z, Spajic A, Santpere G, Li M, Zhang S, Liu Y, Spurrier J, Zhang L, Gudelj I, Rapan L, et al. Transcriptomic taxonomy and neurogenic trajectories of adult human, macaque, and pig hippocampal and entorhinal cells. Neuron. 2022;110:452–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallo V, Deneen B. Glial development:the crossroads of regeneration and repair in the CNS. Neuron. 2014;83:283–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganesan A, Arimondo PB, Rots MG, Jeronimo C, Berdasco M. The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery:from reality to dreams. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:174. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0776-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golomb SM, Guldner IH, Zhao A, Wang Q, Palakurthi B, Aleksandrovic EA, Lopez JA, Lee SW, Yang K, Zhang S. Multi-modal single-cell analysis reveals brain immune landscape plasticity during aging and gut microbiota dysbiosis. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108438. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goritz C, Frisen J. Neural stem cells and neurogenesis in the adult. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:657–659. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillemot F. Cell fate specification in the mammalian telencephalon. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habib N, Avraham-Davidi I, Basu A, Burks T, Shekhar K, Hofree M, Choudhury SR, Aguet F, Gelfand E, Ardlie K, Weitz DA, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Zhang F, Regev A. Massively parallel single-nucleus RNA-seq with DroNc-seq. Nat Methods. 2017;14:955–958. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes TR, Lambert SA. Transcription factors read epigenetics. Science. 2017;356:489–490. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang WW, Salinas RD, Siu JJ, Kelley KW, Delgado RN, Paredes MF, Alvarez-Buylla A, Oldham MC, Lim DA. Distinct and separable roles for EZH2 in neurogenic astroglia. Elife. 2014;3:e02439. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ihrie RA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Lake-front property:a unique germinal niche by the lateral ventricles of the adult brain. Neuron. 2011;70:674–686. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jessberger S, Gage FH. Adult neurogenesis:bridging the gap between mice and humans. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jurkowski MP, Bettio L, E KW, Patten A, Yau SY, Gil-Mohapel J. Beyond the Hippocampus and the SVZ:adult neurogenesis throughout the brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:576444. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.576444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalin JH, Wu M, Gomez AV, Song Y, Das J, Hayward D, Adejola N, Wu M, Panova I, Chung HJ, Kim E, Roberts HJ, Roberts JM, Prusevich P, Jeliazkov JR, Roy Burman SS, Fairall L, Milano C, Eroglu A, Proby CM, et al. Targeting the CoREST complex with dual histone deacetylase and demethylase inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2018;9:53. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02242-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kase Y, Shimazaki T, Okano H. Current understanding of adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain:how does adult neurogenesis decrease with age? Inflamm Regen. 2020;40:10. doi: 10.1186/s41232-020-00122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempermann G, Gast D, Kronenberg G, Yamaguchi M, Gage FH. Early determination and long-term persistence of adult-generated new neurons in the hippocampus of mice. Development. 2003;130:391–399. doi: 10.1242/dev.00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempermann G. Off the beaten track:new neurons in the adult human striatum. Cell. 2014;156:870–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khare SP, Habib F, Sharma R, Gadewal N, Gupta S, Galande S. HIstome--a relational knowledgebase of human histone proteins and histone modifying enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D337–342. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knutson SK, Kawano S, Minoshima Y, Warholic NM, Huang KC, Xiao Y, Kadowaki T, Uesugi M, Kuznetsov G, Kumar N, Wigle TJ, Klaus CR, Allain CJ, Raimondi A, Waters NJ, Smith JJ, Porter-Scott M, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Copeland RA, et al. Selective inhibition of EZH2 by EPZ-6438 leads to potent antitumor activity in EZH2-mutant non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:842–854. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kronenberg G, Reuter K, Steiner B, Brandt MD, Jessberger S, Yamaguchi M, Kempermann G. Subpopulations of proliferating cells of the adult hippocampus respond differently to physiologic neurogenic stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:455–463. doi: 10.1002/cne.10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lacal I, Ventura R. Epigenetic inheritance:concepts, mechanisms and perspectives. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:292. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee DR, Rhodes C, Mitra A, Zhang Y, Maric D, Dale RK, Petros TJ. Transcriptional heterogeneity of ventricular zone cells in the ganglionic eminences of the mouse forebrain. Elife. 2022;11:e71864. doi: 10.7554/eLife.71864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim DA, Huang YC, Swigut T, Mirick AL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Wysocka J, Ernst P, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chromatin remodelling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim L, Mi D, Llorca A, Marin O. Development and functional diversification of cortical interneurons. Neuron. 2018;100:294–313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CA, Rhodes CT, Lin C, Phillips JJ, Berger MS. Comparative analyses identify molecular signature of MRI-classified SVZ-associated glioblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:765–775. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1295186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahadevan V, Mitra A, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Peltekian A, Chittajallu R, Esnault C, Maric D, Rhodes C, Pelkey KA, Dale R, Petros TJ, McBain CJ. NMDARs drive the expression of neuropsychiatric disorder risk genes within GABAergic interneuron subtypes in the juvenile brain. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:712609. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.712609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maksour S, Ooi L, Dottori M. More than a corepressor:the role of CoREST proteins in neurodevelopment. eNeuro. 2020;7:ENEURO.0337–19.2020. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0337-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matt SM, Zimmerman JD, Lawson MA, Bustamante AC, Uddin M, Johnson RW. Inhibition of DNA methylation with zebularine alters lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behavior and neuroinflammation in mice. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:636. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKenzie MG, Cobbs LV, Dummer PD, Petros TJ, Halford MM, Stacker SA, Zou Y, Fishell GJ, Au E. Non-canonical Wnt signaling through Ryk regulates the generation of somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing cortical interneurons. Neuron. 2019;103:853–864. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michurina A, Sakib MS, Kerimoglu C, Kruger DM, Kaurani L, Islam MR, Joshi PD, Schroder S, Centeno TP, Zhou J, Pradhan R, Cha J, Xu X, Eichele G, Zeisberg EM, Kranz A, Stewart AF, Fischer A. Postnatal expression of the lysine methyltransferase SETD1B is essential for learning and the regulation of neuron-enriched genes. EMBO J. 2022;41:e106459. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020106459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain:significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moreno-Jimenez EP, Terreros-Roncal J, Flor-Garcia M, Rabano A, Llorens-Martin M. Evidences for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in humans. J Neurosci. 2021;41:2541–2553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0675-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nasu M, Esumi S, Hatakeyama J, Tamamaki N, Shimamura K. Two-phase lineage specification of telencephalon progenitors generated from mouse embryonic stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:632381. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.632381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Natarajan R. Drugs targeting epigenetic histone acetylation in vascular smooth muscle cells for restenosis and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:725–727. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.222976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ninomiya M, Yamashita T, Araki N, Okano H, Sawamoto K. Enhanced neurogenesis in the ischemic striatum following EGF-induced expansion of transit-amplifying cells in the subventricular zone. Neurosci Lett. 2006;403:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paridaen JT, Huttner WB. Neurogenesis during development of the vertebrate central nervous system. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:351–364. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paton JA, Nottebohm FN. Neurons generated in the adult brain are recruited into functional circuits. Science. 1984;225:1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.6474166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pereira JD, Sansom SN, Smith J, Dobenecker MW, Tarakhovsky A, Livesey FJ. Ezh2, the histone methyltransferase of PRC2, regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15957–15962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002530107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Podobinska M, Szablowska-Gadomska I, Augustyniak J, Sandvig I, Sandvig A, Buzanska L. Epigenetic modulation of stem cells in neurodevelopment:the role of methylation and acetylation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:23. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pursani V, Pethe P, Bashir M, Sampath P, Tanavde V, Bhartiya D. Genetic and epigenetic profiling reveals EZH2-mediated down regulation of OCT-4 involves NR2F2 during cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:13051. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13442-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rhodes CT, Zunino G, Huang SA, Cardona SM, Cardona AE, Berger MS, Lemmon VP, Lin CA. Region specific knock-out reveals distinct roles of chromatin modifiers in adult neurogenic niches. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:377–389. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1426417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richards LJ, Kilpatrick TJ, Bartlett PF. De novo generation of neuronal cells from the adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8591–8595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schuurmans C, Guillemot F. Molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate specification in the developing telencephalon. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Semenov MV. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is a developmental process involved in cognitive development. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:159. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Cebrian-Silla A, Sandoval K, Qi D, Kelley KW, James D, Mayer S, Chang J, Auguste KI, Chang EF, Gutierrez AJ, Kriegstein AR, Mathern GW, Oldham MC, Huang EJ, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yang Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature. 2018;555:377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature25975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stazi G, Taglieri L, Nicolai A, Romanelli A, Fioravanti R, Morrone S, Sabatino M, Ragno R, Taurone S, Nebbioso M, Carletti R, Artico M, Valente S, Scarpa S, Mai A. Dissecting the role of novel EZH2 inhibitors in primary glioblastoma cell cultures:effects on proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and on the pro-inflammatory phenotype. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:173. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Stirpe A, Guidotti N, Northall SJ, Kilic S, Hainard A, Vadas O, Fierz B, Schalch T. SUV39 SET domains mediate crosstalk of heterochromatic histone marks. Elife. 2021;10:e62682. doi: 10.7554/eLife.62682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suzuki S, Murakami Y, Takahata S. H3K36 methylation state and associated silencing mechanisms. Transcription. 2017;8:26–31. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2016.1246076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wester JC, Mahadevan V, Rhodes CT, Calvigioni D, Venkatesh S, Maric D, Hunt S, Yuan X, Zhang Y, Petros TJ, McBain CJ. Neocortical projection neurons instruct inhibitory interneuron circuit development in a lineage-dependent manner. Neuron. 2019;102:960–975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu D, Qiu Y, Jiao Y, Qiu Z, Liu D. Small molecules targeting HATs, HDACs, and BRDs in cancer therapy. Frontiers in oncology. 2020;10:560487. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.560487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie W, Schultz MD, Lister R, Hou Z, Rajagopal N, Ray P, Whitaker JW, Tian S, Hawkins RD, Leung D, Yang H, Wang T, Lee AY, Swanson SA, Zhang J, Zhu Y, Kim A, Nery JR, Urich MA, Kuan S, et al. Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1134–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamashita T, Ninomiya M, Hernandez Acosta P, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Sunabori T, Sakaguchi M, Adachi K, Kojima T, Hirota Y, Kawase T, Araki N, Abe K, Okano H, Sawamoto K. Subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts migrate and differentiate into mature neurons in the post-stroke adult striatum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6627–6636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0149-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu Y, Deng P, Yu B, Szymanski JM, Aghaloo T, Hong C, Wang CY. Inhibition of EZH2 promotes human embryonic stem cell differentiation into mesoderm by reducing H3K27me3. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang C, Macchi F, Magnani E, Sadler KC. Chromatin states shaped by an epigenetic code confer regenerative potential to the mouse liver. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4110. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang H, Zhu D, Zhang Z, Kaluz S, Yu B, Devi NS, Olson JJ, Van Meir EG. EZH2 targeting reduces medulloblastoma growth through epigenetic reactivation of the BAI1/p53 tumor suppressor pathway. Oncogene. 2020a;39:1041–1048. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang J, Ji F, Liu Y, Lei X, Li H, Ji G, Yuan Z, Jiao J. Ezh2 regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis and memory. J Neurosci. 2014;34:5184–5199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4129-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang JQ, Siltanen CA, Liu L, Chang KC, Gartner ZJ, Abate AR. Linked optical and gene expression profiling of single cells at high-throughput. Genome Biol. 2020b;21:49. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-01958-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu Y, Sun D, Jakovcevski M, Jiang Y. Epigenetic mechanism of SETDB1 in brain:implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:115. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0797-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]