Abstract

Neurodegeneration affects a large number of cell types including neurons, astrocytes or oligodendrocytes, and neural stem cells. Neural stem cells can generate new neuronal populations through proliferation, migration, and differentiation. This neurogenic potential may be a relevant factor to fight neurodegeneration and aging. In the last years, we can find growing evidence suggesting that melatonin may be a potential modulator of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. The lack of therapeutic strategies targeting neurogenesis led researchers to explore new molecules. Numerous preclinical studies with melatonin observed how melatonin can modulate and enhance molecular and signaling pathways involved in neurogenesis. We made a special focus on the connection between these modulation mechanisms and their implication in neurodegeneration, to summarize the current knowledge and highlight the therapeutic potential of melatonin.

Key Words: adult hippocampal neurogenesis, aging, melatonin, neural stem cell, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, signaling pathway, therapeutic strategy

Introduction

Neurogenesis is described as the process by which new neurons are formed. During embryonic development and early postnatal weeks, once the nervous tissue has formed and the main neural networks have been developed and established, neurogenesis begins to decline. At this moment, neurogenesis is restricted to two specific areas of the adult brain: the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis describes the generation of new neurons throughout life from adult neural stem cells (NSCs) and the integration of these new neurons into existing neural circuits of the hippocampal formation. Accumulating evidence suggests that adult hippocampal neurogenesis has been implicated in cognitive processes under normal physiological conditions such as learning, memory, mood regulation, and cognitive flexibility. Therefore, adult hippocampal neurogenesis is believed to benefit cognitive functions that enhance survival; indeed, the incorporation of adult-born neurons into the hippocampal circuitry is a remarkable example of plasticity. Adult NSCs are normally in a reversible cell cycle arrest with a low metabolic rate (quiescent state) and high sensitivity to their local signaling environment, and they may be activated by different physiological stimuli such as extrinsic factors (morphogens, growth factors, cytokines, neurotransmitters, and hormones), intracellular factors (transcription factors and epigenetic modulators), and environmental factors like diet or exercise (Surget and Belzung, 2022).

Aging, neurodegenerative disorders, and/or stroke/ischemia have a deleterious effect on the generation of new neurons in brain. In Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (AD and PD), the number and maturation of neurons progressively decline as the disease advances. Indeed, a neurogenesis reduction may lead to disease progression, suggesting that therapies focused on enhancing this decline may delay AD/PD onset or reduce symptoms (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2019; Seki et al., 2019). Adult quiescent NSCs are not activated normally during the development of these pathologies to replace dying neurons. For this reason, a vast amount of research has been performed to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in neurogenesis and to try to stimulate the formation of new neurons in the adult brain. In this context, the endogenous environment is determining neuroregeneration fate and regeneration processes. The intrinsic neurogenic potential and its possible regulation through therapeutic measures present a promising therapeutic approach since many factors, such as neurotrophic support, or endogenous molecules like melatonin, can modulate this process. Given the increasing incidence of neurodegenerative diseases, the promotion of neurogenesis for neural repair is a demanding task. This possible therapeutic approach could result in getting the endogenous factors/molecules to stimulate the adult NSCs and guide the neural precursors to the location of injury to finally replace lost neurons. Due to the technical limitations of human studies, most of our understanding of the functional role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis relies on retrospective analyses using post-mortem tissues and in vitro animal models.

To better understand the physiological roles played by neurogenesis, which functions as a lifelong reservoir of plasticity in the brain, we must unravel the complex interrelationship between the elements that make up neurogenic niches and the dynamics of adult neurogenesis. Currently, some molecules with promising profiles are being studied as potential therapeutic agents to enhance neurogenesis.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The review was performed, including articles from Medline and Web of Science electronic databases updated until January 2022. The terms used for the database search were neurodegeneration AND/OR melatonin AND/OR neurogenesis.

Melatonin

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an indoleamine secreted mainly from the pineal gland, and it is also synthesized in other organs, such as the brain, immune system (bone marrow and lymphoid cells), lung (resident macrophages), enterochromaffin cells of gastrointestinal tract, retina (Photoreceptors), skin cells, and endothelial cells, among others (Acuna-Castroviejo et al., 2014). It has been suggested as a promising modulator of adult hippocampal neurogenesis, there is increasing evidence about the regulation of melatonin at several levels. Therefore, this perspective focuses on the evidence surrounding melatonin in adult hippocampal neurogenesis and its promising therapeutic profile when administered exogenously.

To date, several preclinical studies point melatonin as a potential tool to modulate neurogenesis (Table 1). The in vivo evidence describes the ability of exogenously administrated melatonin to increase neuronal progenitor cells’ survival in the dentate gyrus, and subgranular zone likely through melatonin receptors type-1 and type-2 -dependent mechanisms (Ramirez-Rodriguez et al., 2009; Sotthibundhu et al., 2010). In this sense, it has been demonstrated that melatonin affords neurogenesis and cell proliferation through a melatonin receptor type-2 receptor-dependent mechanism after ischemic stroke (Chern et al., 2012). This would be a key factor in aged brains to avoid neuronal impairment, pinealectomized mice exhibited neurogenesis disruption alleviated by exogenous administration of melatonin (Motta-Teixeira et al., 2018). Notwithstanding, this activity seems to be effective in short treatments, while a 12-month treatment did not afford neurogenesis (Ramirez-Rodriguez et al., 2012). As it is known, melatonin membrane receptors expression decrease during aging (Sanchez-Hidalgo et al., 2009) which may have a direct impact on the neurogenic regulation of this indoleamine (Mihardja et al., 2020). Therefore, old or senescent rodents show changes in the brain that seem to be involved in this lack of effect after melatonin treatment (Hardeland, 2018)

Table 1.

Melatonin activity modulating several pathways and molecular mechanisms related to AHN in animal models

| Pathways/molecular mechanisms | Melatonin activity | AHN relation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEK/ERK1/2(PI3K)/Akt | Activation | Related to cell survival, proliferation and differentiation | Tocharus et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016 |

| Ca2+/CaMKII | Activation | Stimulates dendrite formation | Dominguez-Alonso et al., 2015 |

| ERK | Activation | Proliferation of neural stem cells | Liu et al., 2015 |

| BDNF/TrkB | Restore activity | Promote neuronal survival and normal migration | Chen et al., 2018a |

| BDNF-ERK-CREB | Activation | Microglia related cognitive impairments | Madhu et al., 2021 |

| mTOR | Activation | Decrease autophagy | Li et al., 2019 |

| Dlx2, Shha, Ngn1, Elavl3, and Gfap | Counteraction of induced suppression | Neurogenesis-related genes | Han et al., 2017 |

AHN: Adult hippocampal neurogenesis; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TrKB: tropomycin-receptor kinase B; Ca2+/CaMKII: calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; CREB: cyclic AMP response element-binding protein; ERK: extracellular regulated; MEK/ERK1/2: mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; PI3K/Akt: phosphatidyl inositide 3 kinase/protein kinase B.

One valuable feature of melatonin is its amphiphilic nature, this allows the molecule to cross morphophysiological barriers reaching neurogenesis restricted areas in the hippocampus. This would be the required first step of a molecule to reach these specific brain regions promoting neurogenesis or survival of neurons. The observed relation in vivo between melatonin and neurogenesis promotion encourages deeper research to discover underlying molecular mechanisms.

Neurogenesis-Related Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways Modulated by Melatonin

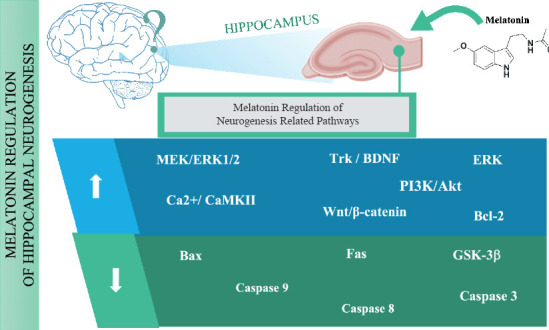

In this regard, several studies reveal that these molecular mechanisms are deeply complex and involve multiple signaling pathways that make melatonin able to achieve newly generated NSCs survival promotion and counteract hippocampal memory impairment. NSCs differentiation and proliferation processes seem to be promoted by melatonin through receptor-dependent mechanisms by mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and phosphatidyl inositide 3 kinase/Akt signaling up-regulation (Figure 1; Tocharus et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). In the last decade, several studies with melatonin reveal its unique ability to enhance hippocampal NSCs differentiation and dendritogenesis along its three stages; dendrite formation, enlargement, and complexity. These activities are developed by both receptor and non-receptor mediated mechanisms. The reports also suggest melatonin’s neurogenic activity as a mitochondria-targeted agent (Dominguez-Alonso et al., 2015; Ghareghani et al., 2017). The mechanism by which melatonin stimulates dendrite formation seems to involve the activation of Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent kinase II and the translocation of calmodulin to stimulate dendrite formation (Figure 1; Dominguez-Alonso et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Neurogenic related pathways modulation after melatonin administration.

The figure represents the possible neurogenic pathways that may be upregulated (blue: MEK/ERK1/2: mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; TrK: tropomycin-receptor kinase; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ERK: extracellular regulated; Ca2+/CaMKII: calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; PI3K/Akt: phosphatidyl inositide 3 kinase/protein kinase B; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2) or down regulated (green: Bax: bcl-2-like protein 4; GSK-3β: glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; Fas; capase 9, 8, 3) in human after the administration of melatonin, data is depicted according to the preclinical evidence reviewed in the manuscript.

The extracellular regulated protein kinases pathway regulation has also been proposed as one of the molecular mechanisms by which melatonin exerts its neurogenic properties stimulating NSCs proliferation in mice (Liu et al., 2015). There are other molecular mechanisms involved in neurogenesis that are also regulated by melatonin, i.e. specific tropomycin-receptor kinase receptors, that activate intracellular signaling of brain-derived neurotrophic factors and promote neuronal survival and normal migration, melatonin administration restores this way induced cognitive impairment (Figure 1; Chen et al., 2018a). In addition, melatonin has been recently shown to enhance neurogenesis in a model of chronic Gulf War Illness through the brain-derived neurotrophic factor-extracellular regulated protein kinases-cyclic AMP response element-binding protein signaling pathway mitigating cognitive and mood impairments (Madhu et al., 2021).

Nonetheless, there is another neuroprotective activity of melatonin in fetal neuropathy recently discovered, it can be also related to NSCs differentiation. These findings suggested that melatonin enhanced NSCs proliferation and self-renewal in embryos of treated mice decreasing autophagy and activating the mechanistic target of the rapamycin signaling pathway (Li et al., 2019). This report is especially relevant in the context of fetal neurodevelopment, in which there are not many therapeutic resources available.

The well-known antioxidant properties of melatonin may additionally assist neurogenesis. In a neurotoxic model of zebrafish exposed to fenvalerate, melatonin reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis diminishing the activity of glutathione peroxidase, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, catalase, and malondialdehyde levels. Melatonin attenuated the induced pro-apoptotic gene up-regulation (Bax, Fas, caspase 8, caspase 9, and caspase 3) and up-regulates the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2. These activities together with the counteraction in the suppression of neurogenesis-related genes (Dlx2, Shha, Ngn1, Elavl3, and Gfap) induced by fenvalerate, restored the abnormalities in zebrafish after fenvalerate exposure (Han et al., 2017).

Neuroprotective Role of Melatonin in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Aging

If we focus on the mechanisms of action described for melatonin related to neurogenesis, we can find that there is a complex regulation of signaling cascades able to regulate self-renewal and differentiation of NSCs, together with an efficient regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. Relative to this, deregulation in Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is associated with neurodegenerative diseases (Inestrosa and Varela-Nallar, 2014; Singh et al., 2018). It has been shown both in vivo and in vitro that melatonin is capable of increasing the expression of β-catenin in neuronal cells (Jeong et al., 2014), and furthermore activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway down-regulating Caspase-3 and Bax, and activating Bcl-2, preventing this way induced apoptotic neuronal cell death (Shen et al., 2017). Interestingly, this ability of melatonin in modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway would aid to maintain cellular homeostasis and counteract impaired adult neurogenesis related to neurodegenerative diseases (Figure 1). Additionally, glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β) inhibition has been recently related to a Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation, in a PD rat model, improving in this way neurogenesis and gliogenesis enhancing NSCs proliferation, self-renewal, and cell survival (Singh et al., 2018). Melatonin may modulate GSK-3β protecting neuronal cells against neurodegeneration processes as observed in an AD mice model expressing an amyloid precursor protein human variant (tg2576 mice). These mice develop amyloid plaques and dystrophic neurites, and after treatment with melatonin, the researchers observed a reversion of memory deficits targeting GSK-3β (Peng et al., 2013). This capacity of melatonin in controlling GSK-3 dysregulation takes on special relevance as it is a crucial enzyme that regulates numerous upstream effectors in neurodegenerative diseases and targets amyloid precursor protein contributing to amyloid plaques formation through PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway leading to a learning and memory impairment (Duda et al., 2018).

In addition to aging, other factors that may cause neurogenesis impairment, such as the adverse effects of certain drugs. In this context, melatonin has demonstrated in rats its ability to counteract induced neurotoxic effects of valproic acid restoring memory hippocampal neurogenesis impairment, the underlying molecular mechanisms appear to be due to its antioxidant activity (Aranarochana et al., 2021). Other drugs such as methotrexate, used as a chemotherapeutic agent, and scopolamine, an inhibitor of muscarinic cholinergic receptors, are also known to display effects in memory impairment and reduction. In some other studies in vivo, melatonin was also able to protect against the reduction of memory or neurogenesis induced by drugs (Chen et al., 2018b; Aranarochana et al., 2019; Sirichoat et al., 2019). Indeed, long-term consumption of psychostimulant drugs such as methamphetamine develops brain function impairment inhibiting cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Administration of melatonin in mice counteracted neurogenesis and learning and memory-induced dysfunctions in the hippocampus (Singhakumar et al., 2015).

In the neuronal cellular environment, the phosphoprotein phosphatases alter phosphorylation/dephosphorylation rate early in neurodegeneration, if this can be counteracted and the homeostasis can be preserved (Arribas et al., 2018). In the cortex and hippocampus of AD patients, there is a substantial drop (about 50%) in Tau dephosphorylation (Gong and Iqbal, 2008). Specifically, phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A is the most susceptible enzyme to decrease, which is a serious problem because it is involved in the cell cycle and regulates numerous signaling pathways. After β-amyloid peptide (1–42)-induction in the mouse model, melatonin administration improves the neuronal survival and cognitive function increasing phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A expression and attenuating the GSK3β levels (Gong et al., 2018). Recently, it has been hypothesized that there is a direct binding between melatonin and phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A, explaining the observed effects of melatonin modulating phosphorylation/dephosphorylation processes (Arribas et al., 2018).

Conclusions

Given these protective activities, the therapeutic use of melatonin as an adjuvant with conventional drugs can counteract the undesirable effects of these drugs, and enhance the efficacy of the treatments.

The non-toxic nature of melatonin and its wide safety profile are essential when considering this molecule as a promising therapeutic agent. Administration of high-dose melatonin did not increase the number of serious adverse events, nonetheless, other adverse events such as dizziness or drowsiness appear to be increased after melatonin treatment (Menczel Schrire et al., 2021). This safety profile brings up the possibility of safely extrapolating the effective doses in vivo to future clinical trials, always considering the therapeutic risk/benefit ratio of melatonin.

Therefore, melatonin deserves deeper research and efforts, due to its safety and above described promising ability (Figure 1) as a potential therapeutic agent promoting neurogenesis and neuron survival in neurodegenerative diseases and aged brain.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

C-Editors: Zhao M, Zhao LJ, Wang Lu; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Acuna-Castroviejo D, Escames G, Venegas C, Diaz-Casado ME, Lima-Cabello E, Lopez LC, Rosales-Corral S, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Extrapineal melatonin:sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2997–3025. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranarochana A, Chaisawang P, Sirichoat A, Pannangrong W, Wigmore P, Welbat JU. Protective effects of melatonin against valproic acid-induced memory impairments and reductions in adult rat hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuroscience. 2019;406:580–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranarochana A, Sirichoat A, Pannangrong W, Wigmore P, Welbat JU. Melatonin ameliorates valproic acid-induced neurogenesis impairment:the role of oxidative stress in adult rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 20212021:9997582. doi: 10.1155/2021/9997582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arribas RL, Romero A, Egea J, de Los Rios C. Modulation of serine/threonine phosphatases by melatonin:therapeutic approaches in neurodegenerative diseases. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:3220–3229. doi: 10.1111/bph.14365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen BH, Park JH, Lee TK, Song M, Kim H, Lee JC, Kim YM, Lee CH, Hwang IK, Kang IJ, Yan BC, Won MH, Ahn JH. Melatonin attenuates scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment via protecting against demyelination through BDNF-TrkB signaling in the mouse dentate gyrus. Chem Biol Interact. 2018a;285:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen BH, Ahn JH, Park JH, Choi SY, Lee YL, Kang IJ, Hwang IK, Lee TK, Shin BN, Lee JC, Hong S, Jeon YH, Shin MC, Cho JH, Won MH, Lee YJ. Effects of scopolamine and melatonin cotreatment on cognition, neuronal damage, and neurogenesis in the mouse dentate gyrus. Neurochem Res. 2018b;43:600–608. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chern CM, Liao JF, Wang YH, Shen YC. Melatonin ameliorates neural function by promoting endogenous neurogenesis through the MT2 melatonin receptor in ischemic-stroke mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1634–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez-Alonso A, Valdes-Tovar M, Solis-Chagoyan H, Benitez-King G. Melatonin stimulates dendrite formation and complexity in the hilar zone of the rat hippocampus:participation of the Ca++/Calmodulin complex. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:1907–1927. doi: 10.3390/ijms16011907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duda P, Wisniewski J, Wojtowicz T, Wojcicka O, Jaskiewicz M, Drulis-Fajdasz D, Rakus D, McCubrey JA, Gizak A. Targeting GSK3 signaling as a potential therapy of neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22:833–848. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1526925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghareghani M, Sadeghi H, Zibara K, Danaei N, Azari H, Ghanbari A. Melatonin increases oligodendrocyte differentiation in cultured neural stem cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37:1319–1324. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0450-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong CX, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau:a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer disease. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:2321–2328. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong YH, Hua N, Zang X, Huang T, He L. Melatonin ameliorates Abeta1-42 -induced Alzheimer's cognitive deficits in mouse model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;70:70–80. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han J, Ji C, Guo Y, Yan R, Hong T, Dou Y, An Y, Tao S, Qin F, Nie J, Ji C, Wang H, Tong J, Xiao W, Zhang J. Mechanisms underlying melatonin-mediated prevention of fenvalerate-induced behavioral and oxidative toxicity in zebrafish. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2017;80:1331–1341. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2017.1384167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardeland R. Recent findings in melatonin research and their relevance to the CNS. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2018;18:102–114. doi: 10.2174/1871524918666180531083944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inestrosa NC, Varela-Nallar L. Wnt signaling in the nervous system and in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6:64–74. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong JK, Lee JH, Moon JH, Lee YJ, Park SY. Melatonin-mediated beta-catenin activation protects neuron cells against prion protein-induced neurotoxicity. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:427–434. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Zhang Y, Liu S, Li F, Wang B, Wang J, Cao L, Xia T, Yao Q, Chen H, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Li Y, Li G, Wang J, Li X, Ni S. Melatonin enhances proliferation and modulates differentiation of neural stem cells via autophagy in hyperglycemia. Stem Cells. 2019;37:504–515. doi: 10.1002/stem.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Guo Y, Yuan Q, Pan Y, Wang L, Liu Q, Wang F, Wang J, Hao A. Melatonin prevents neural tube defects in the offspring of diabetic pregnancy. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:508–517. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Zhang Z, Lv Q, Chen X, Deng W, Shi K, Pan L. Effects and mechanisms of melatonin on the proliferation and neural differentiation of PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madhu LN, Kodali M, Attaluri S, Shuai B, Melissari L, Rao X, Shetty AK. Melatonin improves brain function in a model of chronic Gulf War Illness with modulation of oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasomes, and BDNF-ERK-CREB pathway in the hippocampus. Redox Biol. 2021;43:101973. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menczel Schrire Z, Phillips CL, Chapman JL, Duffy SL, Wong G, D'Rozario AL, Comas M, Raisin I, Saini B, Gordon CJ, McKinnon AC, Naismith SL, Marshall NS, Grunstein RR, Hoyos CM. Safety of higher doses of melatonin in adults:A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pineal Res. 2021;72:e12782. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mihardja M, Roy J, Wong KY, Aquili L, Heng BC, Chan YS, Fung ML, Lim LW. Therapeutic potential of neurogenesis and melatonin regulation in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1478:43–62. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno-Jimenez EP, Flor-Garcia M, Terreros-Roncal J, Rabano A, Cafini F, Pallas-Bazarra N, Avila J, Llorens-Martin M. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2019;25:554–560. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motta-Teixeira LC, Machado-Nils AV, Battagello DS, Diniz GB, Andrade-Silva J, Silva S, Jr, Matos RA, do Amaral FG, Xavier GF, Bittencourt JC, Reiter RJ, Lucassen PJ, Korosi A, Cipolla-Neto J. The absence of maternal pineal melatonin rhythm during pregnancy and lactation impairs offspring physical growth, neurodevelopment, and behavior. Horm Behav. 2018;105:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng CX, Hu J, Liu D, Hong XP, Wu YY, Zhu LQ, Wang JZ. Disease-modified glycogen synthase kinase-3beta intervention by melatonin arrests the pathology and memory deficits in an Alzheimer's animal model. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez-Rodriguez G, Klempin F, Babu H, Benitez-King G, Kempermann G. Melatonin modulates cell survival of new neurons in the hippocampus of adult mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2180–2191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez-Rodriguez G, Vega-Rivera NM, Benitez-King G, Castro-Garcia M, Ortiz-Lopez L. Melatonin supplementation delays the decline of adult hippocampal neurogenesis during normal aging of mice. Neurosci Lett. 2012;530:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Guerrero Montavez JM, Carrascosa-Salmoral Mdel P, Naranjo Gutierrez Mdel C, Lardone PJ, de la Lastra Romero CA. Decreased MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptor expression in extrapineal tissues of the rat during physiological aging. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seki T, Hori T, Miyata H, Maehara M, Namba T. Analysis of proliferating neuronal progenitors and immature neurons in the human hippocampus surgically removed from control and epileptic patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18194. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Z, Zhou Z, Gao S, Guo Y, Gao K, Wang H, Dang X. Melatonin inhibits neural cell apoptosis and promotes locomotor recovery via activation of the Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling pathway after spinal cord injury. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:2336–2343. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S, Mishra A, Bharti S, Tiwari V, Singh J, Parul, Shukla S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates equilibrium between neurogenesis and gliogenesis in rat model of Parkinson's disease:a crosstalk with Wnt and notch signaling. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:6500–6517. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singhakumar R, Boontem P, Ekthuwapranee K, Sotthibundhu A, Mukda S, Chetsawang B, Govitrapong P. Melatonin attenuates methamphetamine-induced inhibition of neurogenesis in the adult mouse hippocampus:An in vivo study. Neurosci Lett. 2015;606:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sirichoat A, Krutsri S, Suwannakot K, Aranarochana A, Chaisawang P, Pannangrong W, Wigmore P, Welbat JU. Melatonin protects against methotrexate-induced memory deficit and hippocampal neurogenesis impairment in a rat model. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;163:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sotthibundhu A, Phansuwan-Pujito P, Govitrapong P. Melatonin increases proliferation of cultured neural stem cells obtained from adult mouse subventricular zone. J Pineal Res. 2010;49:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Surget A, Belzung C. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis shapes adaptation and improves stress response:a mechanistic and integrative perspective. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:403–421. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01136-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tocharus C, Puriboriboon Y, Junmanee T, Tocharus J, Ekthuwapranee K, Govitrapong P. Melatonin enhances adult rat hippocampal progenitor cell proliferation via ERK signaling pathway through melatonin receptor. Neuroscience. 2014;275:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]