Abstract

Spinal cord injury is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among young adults in many countries including the United States. Difficulty in the regeneration of neurons is one of the main obstacles that leave spinal cord injury patients with permanent paralysis in most instances. Recent research has found that preventing acute and subacute secondary cellular damages to the neurons and supporting glial cells can help slow the progression of spinal cord injury pathogenesis, in part by reactivating endogenous regenerative proteins including Noggin that are normally present during spinal cord development. Noggin is a complex protein and natural inhibitor of the multifunctional bone morphogenetic proteins, and its expression is high during spinal cord development and after induction of spinal cord injury. In this review article, we first discuss the change in expression of Noggin during pathogenesis in spinal cord injury. Second, we discuss the current research knowledge about the neuroprotective role of Noggin in preclinical models of spinal cord injury. Lastly, we explain the gap in the knowledge for the use of Noggin in the treatment of spinal cord injury. The results from extensive in vitro and in vivo research have revealed that the therapeutic efficacy of Noggin treatment remains debatable due to its neuroprotective effects observed only in early phases of spinal cord injury but little to no effect on altering pathogenesis and functional recovery observed in the chronic phase of spinal cord injury. Furthermore, clinical information regarding the role of Noggin in the alleviation of progression of pathogenesis, its therapeutic efficacy, bioavailability, and safety in human spinal cord injury is still lacking and therefore needs further investigation.

Key Words: apoptosis, astrocyte differentiation, axon myelination, axon regeneration, bone morphogenetic protein, glial scar, heterotrophic ossification, neurogenesis, neuropathic pain, Noggin, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs mostly due to motor vehicle accidents followed by other severely traumatic events including gun violence, sport-related injuries, accidental falls, and work-related injuries (Raghava et al., 2017; Merritt et al., 2019). The occurrence of SCI is associated with serious health and mental problems and an enormous economic burden on the patients, their families, and the society at large (Raghava et al., 2017; Merritt et al., 2019). SCI is more common in the United States than the other countries around the world, with an incidence of approximately 40 new cases per million per year (Farace and Alves, 2000; Devivo, 2012; Chan et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2018). SCI mostly affects young adults (teens to early twenties), and it is 3 to 4 times more common in males than in females (Farace and Alves, 2000; Devivo, 2012; Chan et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2018). SCI in the males mostly occurs in early life due to road traffic accidents or sports-related injuries, whereas SCI in the females mostly occurs in late life (Farace and Alves, 2000; Devivo, 2012; Chan et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2018). Penetrating SCI tends to be more severe with complete damage to the spinal cord resulting in poor functional recovery of motor function (Farace and Alves, 2000; Devivo, 2012; Chan et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2018). In contrast, patients with blunt SCI tend to have incomplete damage to the spinal cord with a relatively better outcome (Farace and Alves, 2000; Devivo, 2012; Chan et al., 2013; Roach et al., 2018).

SCI occurs most frequently in the cervical region followed by the thoracic region and then the lumbar region. Temporary or persistent impairment in the locomotor and sensory functions in the body portion innervated by the injured spinal segment may be experienced by the patients with SCI. Additionally, allodynia, heterotopic ossifications, skin ulcers, diabetes, and other long-term effects may occur in patients with SCI (Menon and Tan, 1992; Ditunno et al., 1994; McKinley et al., 2002; Wuermser et al., 2007).

SCI comprises three overlapping phases at the cellular level: acute, subacute, and chronic phases (Witiw and Fehlings, 2015; Anjum et al., 2020). Loss of neurons and glial cells, swelling, bleeding, edema, and infiltration of inflammatory cells characterize the acute phase, which occurs within the first 48 hours after the induction of injury (Witiw and Fehlings, 2015; Anjum et al., 2020). The subacute phase begins within 2 weeks after the damage and is marked by the formation of glial scar and axon sprouting (Witiw and Fehlings, 2015; Anjum et al., 2020). The chronic phase of SCI is characterized by more glial scar deposition, apoptosis, necrosis, demyelination, and Wallerian axon degeneration, and it can last for months or years (Witiw and Fehlings, 2015; Anjum et al., 2020). Even though these stages have been widely reported in the literature, there is no consensus, and these stages of damage are likely to differ by individual case and depending on the severity of the initial lesion.

Multiple spine traumas are prevalent in SCI patients, resulting in spinal cord compression, laceration, or transection damage (Warburton et al., 2007; Rabinstein, 2018; Wang et al., 2021). Even though the initial injury is irreversible, SCI treatment seeks to stabilize the spine, prevent further damage, and enhance functional recovery (Warburton et al., 2007; Rabinstein, 2018; Wang et al., 2021). The current management of patients with SCI includes surgical interventions for stabilization or decompression, medical treatment for respiratory, cardiovascular, and other organ complications, and rehabilitation to control metabolic changes, bowel problems, urinary tract complications, and prevent deep vein thrombosis (Warburton et al., 2007; Rabinstein, 2018; Wang et al., 2021).

Despite advances in SCI therapy, patients have a high mortality rate, roughly three times that of the general population, with respiratory issues, cardiac problems, cancer, infection, septicemia, and unintentional accidents being the most prevalent reasons of death (DeVivo et al., 2022). As a result, recent research has focused on preclinical models of SCI with the goal of using novel therapeutics to target molecular pathways involved in the regulation of early pathogenic changes in SCI, particularly the acute and subacute phases, to improve neuronal survival, reduce astroglia scar formation, enhance axonal regeneration, and remyelination (Ray et al., 2011).

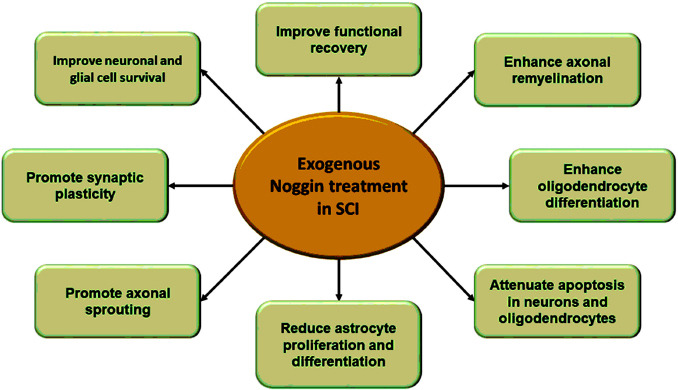

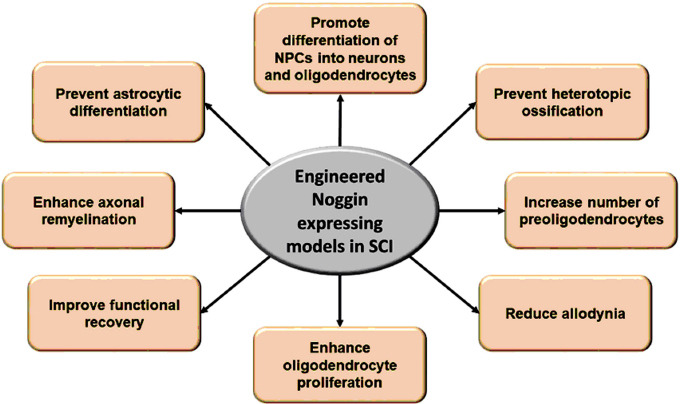

Noggin is an endogenous inhibitor of a collection of multifunctional bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), a subgroup of the transforming growth factor-beta family of proteins that are involved in the spinal cord development and homeostasis (Al-Sammarraie and Ray, 2021). In this review article, we focused on the neuroprotective role of Noggin in preclinical models of SCI, doses, route of administration, and duration of treatment. Further, we discussed the results for the neuroprotective effects of Noggin in promoting functional recovery in preclinical models of SCI following exogenous treatment with recombinant Noggin in cell culture models of SCI (Table 1) as well as in animal models of SCI (Table 2). Similarly, we discussed the results for the neuroprotective effects of Noggin after engrafting the engineered cells expressing Noggin protein to the injured site of the spinal cord (Table 3). The major finding from these studies is that the neuroprotective effect is noticeable in an early phase of SCI in both in vitro and in vivo models following exogenous Noggin treatment (Figure 1) as well as in SCI in vivo models following therapy with the engineered Noggin expressing cells or implants (Figure 2). It needs to be noted that the molecular mechanisms for the neuroprotective effect of Noggin in the early phase of SCI occur mostly via the p-Smad1/5/8 pathway and/or the p-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) pathway (Figure 3), but the long-term neuroprotective effect of Noggin in SCI remains debatable to date.

Table 1.

Noggin treatment in cell culture models of spinal cord injury

| Cell type | Noggin treatment | Dose | Duration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes derived from spinal cord of postnatal rat pups | Recombinant Noggin protein | 1.5 μg/mL | 6 d | Fuller et al., 2007 |

| Neural progenitor cells isolated from adult YFP+/– transgenic mouse spinal cords | Recombinant human Noggin protein | 50–150 ng/mL | 5 d | Hart et al., 2020 |

| Glial cells isolated from rat pup cortices | Recombinant human Noggin protein | 150 ng/mL | 3 d | Hart et al., 2020 |

| Oligodendrocyte precursor cells isolated from rat pup cortices | Recombinant human Noggin protein | 150 ng/mL | 24 h | Hart et al., 2020 |

| Primary cortical neurons isolated from rat embryo cortices | Recombinant human Noggin protein | 150 ng/mL | 3 d | Hart et al., 2020 |

| Neurospheres cultured from spinal cords of adult female mice | Recombinant mouse Noggin protein | 200 ng/mL | 3 d | Xiao et al., 2010 |

Table 2.

Noggin treatment in animal models of spinal cord injury

| Animal model | Mode of spinal cord injury | Noggin treatment | Dose and route of administration | Duration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprague-Dawley rats (female) | Contusion injury at T7 | Recombinant human Noggin protein | 1.2–2.4 μg/d intrathecal injections | 3 d to 10 wk | Hart et al., 2020 |

| Mice (female) | Contusion injury at T8 and T9 | Recombinant mouse Noggin protein | 15 ng/kg/d intrathecal injection with osmotic minipump | 1 wk | Xiao et al., 2010 |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Transection injury at T10 | Recombinant Noggin protein | 1 µg/kg noggin injection | 1 to 7 d | Cui et al., 2015 |

| Sprague-Dawley rats (female) | Contusion injury at T9–T10 | Recombinant mouse Noggin protein | 17.8 μg/kg/d intrathecal injection with osmotic minipump | 2 wk | Matsuura et al., 2008 |

| Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (male) | Ligation of spinal nerve ligation at L5 (an animal model of neuropathic pain) | Recombinant Noggin protein | 5 µg/mL intrathecal injection | 1 to 7 d | Yang et al., 2019 |

Table 3.

Noggin expressing cells or implants engrafted in animal models of spinal cord injury

| Animal model | Type of spinal cord injury | Noggin expressing cells or implant | Duration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult C57BL/6 mice (female) | Transection (hemisection) T9–T10 | Biomaterial bridge implants loaded with pLenti-CMV-Noggin | 8 wk | Smith et al., 2019 |

| Adult Fischer 344 rats (female) | Contusion injury at T9 | Noggin -expressing oligodendrocyte precursor cells derived from Fischer rat embryos | 5 wk | Enzmann et al., 2005 |

| Adult Fischer 344 rats (female) | Focal ischemic injury at C7 | Noggin-expressing neuronal restricted cells derived from Fischer rat embryos | 5 wk | Enzmann et al., 2005 |

| Adult Fischer 344 rats (female) | Focal ischemic injury at C7 | Noggin-expressing neural stem cells derived from Fischer rat embryos | 5 wk | Enzmann et al., 2005 |

| Adult C57BL/6 mice | Achilles tenotomy (heterotopic ossification animal model) | Noggin-expressing mouse muscle-derived stem cells | 10 wk | Hannallah et al., 2004 |

| Adult ICR mice (male) | Contusion injury at T8 and T9 | Noggin-expressing neural progenitor cells derived from ICR mice | 3 wk | Setoguchi et al., 2004 |

Figure 1.

Neuroprotective effect of exogenous Noggin treatment in SCI.

Both in vitro and in vivo models of SCI following Noggin treatments show enhancement of neuronal survival, axon remyelination, synaptic plasticity, and functional recovery. SCI: Spinal cord injury.

Figure 2.

Neuroprotective effects of engineered Noggin expressing cells or implants in SCI.

Noggin expressing cells or implants modulate the fate of differentiation of the precursor cells into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes, improve functional recovery following SCI, and attenuate secondary complications of allodynia and heterotopic ossification. SCI: Spinal cord injury.

Figure 3.

Molecular mechanisms of the neuroprotective effect of Noggin in SCI.

Noggin binds to BMP ligand (most likely BMP4) and prevents its binding with BMP receptor (BMPr) 1 and 2. Noggin treatment inhibits BMP-mediated phosphorylation of Smad 1/5/8 and/or STAT3, which can lead to inhibition of astrocyte differentiation, glial scar formation, and neuronal and glial cell apoptosis. BMP: Bone morphogenetic protein; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; p-STAT3: p-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

For this narrative review, we searched the PubMed database for the studies that used Noggin to treat in vitro and in vivo models of SCI with high BMP signatures. The search term “Noggin AND spinal cord injury” was used. The search results retained relevant publications that were published between March 2004 and March 2020. The results were then further filtered to contain the original research publications, which were then sorted according to the major findings.

Structure, Function, and Expression of Noggin during Development and Spinal Cord Injury

Noggin gene (NOG) encodes for Noggin protein and NOG is located on human chromosome 17q21 (Valenzuela et al., 1995; Gong et al., 1999; Dixon et al., 2001). Human Noggin following expression of NOG is secreted as a homodimer protein of 205 amino acids with two distinct ends: an amino terminal (acidic) and a carboxy terminal (cysteine-rich). In addition, Noggin has a heparin-binding region that holds the protein to the cell surface. Noggin is a specific endogenous antagonist of BMP, a multifunctional protein belonging to the transforming growth factor-beta family. Noggin binds to BMP receptor 1 and 2 binding sites on the surface of BMP ligands, with higher affinity to BMP4 compared to BMP7, and impedes their interactions with BMP receptors (Groppe et al., 2002).

Noggin is highly expressed in dorsal somite and notochord and prechordal mesoderm, which are important for the development of neural plate and neural tube during spinal cord development (Smith and Harland, 1992; Setoguchi et al., 2004). Mutation in the human homolog of the NOG has been associated with multiple synostosis syndrome and symphalangism deafness syndrome in humans (Edwards et al., 2000).

Noggin expression is further reactivated during SCI, and it is particularly expressed in glial cells near the injury site. Studies in mice show that dorsal rhizotomy of the spinal cord results in high expression of Noggin as well as of BMP ligands, particularly in the outer layer of the spinal white matter and the posterior aspect of the spinal neuropil. The expression of Noggin was also cell-type specific where it was mainly localized in the astrocytes and other glial cells in the injured site (Hampton et al., 2007a). Similarly, transection trauma to rat spinal cord results in overexpression of Noggin and BMP ligands. Noggin was also overexpressed by the reactive astrocytes surrounding the lesion. Besides, cell culture studies show that Noggin is produced by astrocytes isolated from the injured rat spinal cord (Hampton et al., 2007b). Furthermore, Noggin, Sonic hedgehog, and other neural tube formation factors are reactivated in the injured spinal cord obtained from the motoneuron depleted mice (Gulino and Gulisano, 2013). These expression data implied that reactivating endogenous Noggin in the acute and subacute phases of SCI could be beneficial in reducing glial scar formation and counteracting the detrimental effects of BMP signaling in an attempt to restore the structure and function of the injured spinal cord.

Noggin Reduces Astrocyte Differentiation and Glial Scar Formation in the Early Phases of Spinal Cord Injury

One of the most noticeable pathologies following SCI is astrocyte cell proliferation (astrocytosis). Glial scar formation and its maturation in part occur because of astrocytosis, obstructing neuronal function and conductivity. Hence, inhibiting astrocytosis to limit astrocyte scar development is crucial for maintaining neuron function.

Recent studies have shown that Noggin therapy is able to inhibit astrocyte differentiation, proliferation, and function in cell culture. In astrocytes cultured from the rat’s spinal cord and subjected to exposure to high concentrations of BMP4, Noggin treatment reduced the production of the main components of glial scar including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and secreted chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans (Fuller et al., 2007). Similarly, the addition of a high dosage of Noggin to the mouse spinal cord-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) reduced BMP4-induced astrocyte differentiation via inhibiting canonical BMP signaling (involving Smad1/5/8) (Hart et al., 2020). Likewise, Noggin treatment inhibited BMP4-mediated differentiation of neural stem cells into astrocytes with an increase in the number of neurons in the cell culture of the neurospheres derived from the mice model of SCI (Xiao et al., 2010). In addition, an in vitro study found that cultivating Noggin-producing oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) in high concentrations of BMP7 for one week resulted in a significant decrease in GFAP and reduced development into astrocytes (Enzmann et al., 2005).

In contrast to the in vitro findings, studies from an in vivo SCI model demonstrate an argumentative impact of Noggin on glial scar development. In a rat model of contusion SCI with a high signature of BMP4, short-term Noggin therapy results in a substantial reduction in chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans expression at the injury site, implying a reduction in glial scar formation compared to the untreated control (Hart et al., 2020). Similarly, in a rat model of transection SCI with augmented BMP2 and 4, histological analysis 7 days after Noggin administration showed better structural organization of neurons and glial cells at the injury site and a decrease in glial scar formation (Cui et al., 2015). Contrary to previous reports, histological analysis of mouse spinal cords obtained following contusion injury showed that intrathecal Noggin therapy was inefficient in lowering GFAP expression and astrocyte activation, with no significant effect on glial scar reduction, while being effective in suppressing the BMP-Smad1/5/8 canonical pathway (Xiao et al., 2010). Likewise, in a rat model of contusion SCI with increased BMP2 and 4 signaling, Noggin therapy decreased Smad1/5/8 but did not reduce glial scar formation (Matsuura et al., 2008). These findings imply that Noggin therapy was beneficial in lowering scar formation in the acute and subacute phases of SCI, but ineffective in inhibiting chronic astrocyte activation and subsequent glial scar accumulation. Moreover, it was postulated that other pathways might play a role in glial scar development as the pathogenesis of SCI progressed.

Noggin Enhances Neuronal Plasticity following Spinal Cord Injury

Neuronal plasticity of the spinal cord is an important adaptive mechanism to improve locomotor function following injury. It includes sprouting of axons, reorganization of synapses, and rarely neurogenesis (Darian-Smith, 2009; Liu et al., 2012). Axon sprouting is the major adaptive mechanism following SCI and involves the lateral extension of the undamaged axons near the injury site and away from the impeding glial scar (Darian-Smith, 2009; Liu et al., 2012). Reorganization of synapses involves a change in the morphology of dendrites and an increase in dendritic spines (Darian-Smith, 2009; Liu et al., 2012). Neurogenesis, or the formation of new neurons, rarely occurs after SCI and is only observed in a few animal models with a specific type of SCI that does not involve glial scar formation (Darian-Smith, 2009; Liu et al., 2012). Regulation of neuronal plasticity at the molecular level involves reactivation of the signaling molecules and growth factors that are normally expressed during spinal cord morphogenesis. Morphogenetic factors, including Noggin and other proteins, are critical for neural induction and neural tube formation, and it has recently been discovered that they are reactivated during SCI (Gulino and Gulisano, 2013).

In a motoneuron-depleted mouse model of SCI, Noggin and other proteins particularly Sonic hedgehog reduce astrocyte differentiation and glial scar formation to promote tissue regeneration at the damaged site (Gulino and Gulisano, 2013). Furthermore, multivariate regression analysis has clearly shown that Noggin regulates the transactive-response DNA-binding protein 43, which is a nuclear RNA/DNA binding protein important for neuronal plasticity and repair (Gulino et al., 2015). In a mouse model of contusion SCI, engrafting Noggin-expressing NPCs promoted neurogenesis and resulted in their differentiation into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes and neurons and limited their differentiation into astrocytes (Setoguchi et al., 2004).

In contrast, engrafting Noggin-producing neural stem cells in the rat model of contusion SCI resulted in their differentiation toward glial cells and not neuronal cell type. Engrafting Noggin-produced OPCs into rats with injured spinal cord did not enhance differentiation to myelin-producing oligodendrocytes. In addition, engrafting Noggin-producing NPCs, OPCs, and neural stem cells into the injured spinal cord in rats exacerbated gray matter damage, as assessed one week after the injury (Enzmann et al., 2005). Similarly, intrathecal administration of a Noggin function-blocking antibody in rhizotomy-induced SCI mouse model led to overexpression of several proteins indicative of sprouting of axons in the spinal cord (Hampton et al., 2007a).

These results suggest a controversial role of BMP inhibition early versus late during the pathogenesis of SCI and although Noggin treatment seems to enhance neuroplasticity, it is ineffective in the treatment of the later phase of injury.

Noggin Enhances Axonal Sprouting and Regeneration following Spinal Cord Injury

Damage to neurons during SCI is irreversible and permanent in most cases. This is the main cause of long-term disability following injury. Although axon regeneration following SCI is not observed in humans, a study in an animal model of SCI has shown evidence of regeneration due to Noggin treatment. Intrathecal administration of Noggin in a rat model of contusion SCI enhanced sprouting of axon in the corticospinal tract with an elevation of BMP2/4 signature. It also showed that motor function was improved in response to new axon sprouting following injury (Matsuura et al., 2008).

Noggin Improves the Survival of Glial Cells, Oligodendrocyte Differentiation, and Remyelination of Axons following Spinal Cord Injury

Glial cells are the most common type of cells in the spinal cord with a ratio of 11:1 or 13:1 glia to neurons, particularly in the inner gray matter region. Different types of glial cells are present in the spinal cord with more astrocytes and oligodendrocytes than microglial cells in a ratio of 40:40:20 (Ruiz-Sauri et al., 2019). Activation of glial cells is one of the hallmarks of SCI pathogenesis (Yuan and He, 2013; Orr and Gensel, 2018). Immediate loss and secondary damages involve not only neurons but also oligodendrocytes through the course of pathogenesis in SCI. These damages include changes in amounts of autophagy, apoptosis, and necrosis that lead to demyelination of axons ultimately impairing neuronal conductivity (Wang et al., 2017). Remyelination of neurons is an important function of the glial cells during spinal cord development and regeneration. Damage to the glial cells, particularly oligodendrocytes, is an important factor that impairs the axonal remyelination in neurons (Monje, 2021).

Oligodendrocytes are one of the most important glial cells responsible for the myelination of axons. Damage to the spinal cord causes severe damage in the oligodendrocyte populations due to significant amounts of apoptosis and necrosis. Reactivation of differentiation in OPCs in course of SCI helps replenish some of the lost cells and promote remyelination of axons following injury (Almad et al., 2011). Overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor-AA and Noggin treatment increased number of oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte-derived myelin, which improved remyelination of neurons following SCI in mice (Smith et al., 2019). This combination therapy, which acts to enroll and differentiate endogenous progenitors to aid remyelination following injury, represents a promising translatable treatment for SCI.

In addition, a study showed that low doses of intrathecal Noggin treatment in a rat model of contusion SCI with high BMP4 expression were able to increase oligodendrogenesis and oligodendrocyte differentiation, and high doses were able to sustain the number of mature oligodendrocytes following injury (Hart et al., 2020). In contrast, Noggin treatment and histological analysis of spinal cord tissue obtained from the rats with contusion SCI had no significant effect on axonal density and thickness of myelin sheet compared to untreated control, suggesting no effect of Noggin treatment on remyelination of axon on a long-term (Hart et al., 2020).

These results implied that long-term Noggin treatment would be effective in increasing the number of myelin-producing oligodendroglia cells that would help promote the remyelination of axons following injury.

Noggin Reduces Caspase-Mediated Apoptosis in Spinal Cord Injury

Apoptotic, necrotic, and autophagic cell deaths are found throughout the progressive pathogenesis of SCI. The cell death processes involve both neurons and glial cells, particularly the myelin-producing oligodendrocytes. In vitro treatment of Noggin was able to inhibit caspase-3-induced apoptotic cell death in both neurons and oligodendrocytes exposed to a high concentration of BMP4 (Hart et al., 2020). Similarly, in vivo study showed that Noggin treatment reduced active caspase-3-mediated apoptotic cell death in a rat model of contusion SCI. However, BMP inhibition was cell-type specific and was effective only in attenuating apoptotic cell death in neurons but not in oligodendrocytes (Hart et al., 2020). These results from both in vitro and in vivo studies strongly suggest the neuroprotective effect of Noggin in preventing early neuronal loss following injury.

Noggin Improves Functional Recovery following Spinal Cord Injury

Functional recovery is impaired temporarily or permanently following SCI due to primary and secondary loss of neurons, glial cells, demyelination of neurons, and glial scar formation. The effect of Noggin on functional recovery from SCI remains controversial. Intrathecal administration of Noggin in a rat model of transection SCI showed 8 folds improvement in the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan score (locomotor function), as assessed 7 days post-injury (Cui et al., 2015). Similarly, intrathecal administration of Noggin in a rat model of contusion SCI and high BMP2/4 signaling showed improvement of locomotor recovery, as the Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan score assessed at 10 weeks following injury (Matsuura et al., 2008). In addition, engrafting Noggin expressing NPCs in a mouse model of contusion SCI resulted in significant partial improvement in locomotor function (Setoguchi et al., 2004). In contrast, histological analysis and locomotor assessment 10 weeks following contusion injury in a rat model with augmented BMP4 signaling showed no significant protective effect of Noggin on functional recovery, reduction in glial scar formation, or tissue preservation following injury (Hart et al., 2020).

These results also suggested that Noggin treatment could have a transient neuroprotective effect in improving functional recovery in acute and subacute phases, but this effect was diminished in the chronic phase of SCI. It also implies that Noggin inhibition of BMP signaling has a minor effect on long-term tissue healing post-injury and it is inefficient for preventing chronic damage and glial scar formation in the late phase of SCI, suggesting the involvement of other factors and pathways that play the major roles in the pathogenesis during the late phase of SCI, requiring further investigation.

Noggin Treatment Reduces Allodynia following Spinal Cord Injury

Allodynia is a painful sensation caused by a typically non-painful trigger and is one of the long-term sequelae of SCI with unknown etiology (Burke et al., 2017). A study in a rat model of SCI with ligation of L5 spinal nerves showed elevation in BMP4 signaling, and intrathecal administration of Noggin reduced allodynia, as evidenced by alleviation of the decrease in paw-withdrawal threshold in response to stimuli. It also inhibited BMP4 mediated GFAP expression and astrocyte activation as well. Also, it inhibits phosphorylation of the STAT3, a downstream target of BMP4 and important glial activation marker, over the course of 7 days (Yang et al., 2019).

Noggin Reduces Heterotopic Ossification following Spinal Cord Injury

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is another long-term complication following SCI (Franz et al., 2022). It also occurs in patients with mutations in BMP receptors without injury (Agarwal et al., 2017). HO is characterized by the development of painful bone growth in muscle, tendon, and tissues below the injury site (Xu et al., 2022). Although the causes of HO are largely unknown, evidence from animal studies suggests the involvement of BMP-Noggin signaling in its pathogenesis. BMP4 was correlated with induction of HO in mice, while engrafting Noggin expressing mouse muscle-derived stem cells in mice model of HO was able to inhibit HO and enhanced demineralization of the formed bone matrix (Hannallah et al., 2004).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Noggin, which is a secreted endogenous inhibitor of BMP signaling, is differentially expressed during acute and subacute phases of SCI. Noggin is mainly expressed by the glial cells, particularly astrocytes. Many in vitro studies show neuroprotective effects of Noggin by enhancing oligodendrocyte differentiation, which is important for axonal remyelination in neurons. Similarly, many in vivo studies have shown that exogenous administration of Noggin or engrafting Noggin secreting glial cells were able to reduce glial scar formation, improve axonal remyelination, and enhance neuronal plasticity in the preclinical animal models of SCI. However, still little is known about numerous effects of Noggin on SCI and several gaps in the knowledge do exist. First, many studies have focused mainly on the effect of Noggin at the cellular level and mostly on glial cells; however, the cause-effect link is not well studied, and the molecular regulation and downstream targets of Noggin in SCI remain unknown. Second, Noggin is under tight physiological control, and it is administrated in high doses in animals without data about its effect on other organs. Besides, the doses in the preclinical models of SCI vary widely and most studies have used only one high dose of Noggin with little knowledge about the lowest effective dose versus the toxic dose. So, further studies to assess the safety of Noggin, particularly in animal models of SCI are required. Third, the neuroprotective effects of Noggin were demonstrated during the early phases of SCI, and little is known about the long-term effects of Noggin treatment. Fourth, in most of the SCI models, the injury is introduced in lower thoracic vertebrae without exploring the effect at other locations particularly the most common site of injury, the cervical region, which has differences in the cellular response to injury. Fifth, the difference in pathology and molecular changes in response to contusion versus transection injury to the spinal cord should be considered when assessing the expression and effect of Noggin following injury. Sixth, most in vivo studies use female rats or female mice for induction of SCI without taking the gender difference into consideration in the outcome of SCI in humans, and whether this experimental design strategy also affects the response to Noggin treatment. Seventh, the complex nature of the Noggin-BMP signaling and its interactions with other pathways during acute, subacute, and chronic phases of SCI are not yet understood and require further preclinical and clinical studies to investigate the change-response in Noggin-BMP signaling throughout SCI. Overall, there is clear evidence that Noggin treatment has neuroprotective effects in vitro as well as in vivo during the early stages of SCI, which can be further augmented or combined with another treatment to provide long-term effects. So, the neuroprotective role of Noggin in SCI warrants further preclinical investigations to make it translational to the clinics and to determine whether it is a potential therapy to improve patient outcomes following SCI.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by SCIRF-2020 PD-01 from the South Carolina Spinal Cord Injury Research Fund (Columbia, SC, USA) (to SKR).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open peer reviewer: Iris Leister, Paracelsus Medical University, Austria.

P-Reviewer: Leister I; C-Editors: Zhao M, Zhao LJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Agarwal S, Sorkin M, Levi B. Heterotopic ossification and hypertrophic scars. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Sammarraie N, Ray SK. Bone morphogenic protein signaling in spinal cord injury. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8:53–63. doi: 10.20517/2347-8659.2020.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almad A, Sahinkaya FR, McTigue DM. Oligodendrocyte fate after spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:262–273. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0033-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anjum A, Yazid MD, Fauzi Daud M, Idris J, Ng AMH, Selvi Naicker A, Ismail OHR, Athi Kumar RK, Lokanathan Y. Spinal cord injury:pathophysiology, multimolecular interactions, and underlying recovery mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7533. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke D, Fullen BM, Stokes D, Lennon O. Neuropathic pain prevalence following spinal cord injury:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2017;21:29–44. doi: 10.1002/ejp.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan WM, Mohammed Y, Lee I, Pearse DD. Effect of gender on recovery after spinal cord injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:447–461. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui ZS, Zhao P, Jia CX, Liu HJ, Qi R, Cui JW, Cui JH, Peng Q, Lin B, Rao YJ. Local expression and role of BMP-2/4 in injured spinal cord. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:9109–9117. doi: 10.4238/2015.August.7.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darian-Smith C. Synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:149–165. doi: 10.1177/1073858408331372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devivo MJ. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury:trends and future implications. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:365–372. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVivo MJ, Chen Y, Wen H. Cause of death trends among persons with spinal cord injury in the United States:1960-2017. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditunno JF, Young W, Donovan WH, Creasey G. The international standards booklet for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Paraplegia. 1994;32:70–80. doi: 10.1038/sc.1994.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon ME, Armstrong P, Stevens DB, Bamshad M. Identical mutations in NOG can cause either tarsal/carpal coalition syndrome or proximal symphalangism. Genet Med. 2001;3:349–353. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards MJ, Rowe L, Petroff V. Herrmann multiple synostosis syndrome with neurological complications caused by spinal canal stenosis. Am J Med Genet. 2000;95:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enzmann GU, Benton RL, Woock JP, Howard RM, Tsoulfas P, Whittemore SR. Consequences of noggin expression by neural stem, glial, and neuronal precursor cells engrafted into the injured spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farace E, Alves WM. Do women fare worse:a metaanalysis of gender differences in traumatic brain injury outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:539–545. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.4.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franz S, Rust L, Heutehaus L, Rupp R, Schuld C, Weidner N. Impact of heterotopic ossification on functional recovery in acute spinal cord injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:842090. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.842090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller ML, DeChant AK, Rothstein B, Caprariello A, Wang R, Hall AK, Miller RH. Bone morphogenetic proteins promote gliosis in demyelinating spinal cord lesions. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:288–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong Y, Krakow D, Marcelino J, Wilkin D, Chitayat D, Babul-Hirji R, Hudgins L, Cremers CW, Cremers FP, Brunner HG, Reinker K, Rimoin DL, Cohn DH, Goodman FR, Reardon W, Patton M, Francomano CA, Warman ML. Heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding noggin affect human joint morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 1999;21:302–304. doi: 10.1038/6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groppe J, Greenwald J, Wiater E, Rodriguez-Leon J, Economides AN, Kwiatkowski W, Affolter M, Vale WW, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Choe S. Structural basis of BMP signalling inhibition by the cystine knot protein Noggin. Nature. 2002;420:636–642. doi: 10.1038/nature01245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulino R, Gulisano M. Noggin and Sonic hedgehog are involved in compensatory changes within the motoneuron-depleted mouse spinal cord. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulino R, Parenti R, Gulisano M. Novel mechanisms of spinal cord plasticity in a mouse model of motoneuron disease. Biomed Res Int. 20152015:654637. doi: 10.1155/2015/654637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampton DW, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Ramer MS. Spinally upregulated noggin suppresses axonal and dendritic plasticity following dorsal rhizotomy. Exp Neurol. 2007a;204:366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampton DW, Asher RA, Kondo T, Steeves JD, Ramer MS, Fawcett JW. A potential role for bone morphogenetic protein signalling in glial cell fate determination following adult central nervous system injury in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2007b;26:3024–3035. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannallah D, Peng H, Young B, Usas A, Gearhart B, Huard J. Retroviral delivery of Noggin inhibits the formation of heterotopic ossification induced by BMP-4, demineralized bone matrix, and trauma in an animal model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:80–91. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart CG, Dyck SM, Kataria H, Alizadeh A, Nagakannan P, Thliveris JA, Eftekharpour E, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Acute upregulation of bone morphogenetic protein-4 regulates endogenous cell response and promotes cell death in spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2020;325:113163. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Yang X, Jiang L, Wang C, Yang M. Neural plasticity after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:386–391. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuura I, Taniguchi J, Hata K, Saeki N, Yamashita T. BMP inhibition enhances axonal growth and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1471–1479. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKinley WO, Tewksbury MA, Godbout CJ. Comparison of medical complications following nontraumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:88–93. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menon EB, Tan ES. Urinary tract infection in acute spinal cord injury. Singapore Med J. 1992;33:359–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merritt CH, Taylor MA, Yelton CJ, Ray SK. Economic impact of traumatic spinal cord injuries in the United States. Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;6:9. doi: 10.20517/2347-8659.2019.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monje M. Spinal cord injury - healing from within. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:182–184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr2030836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orr MB, Gensel JC. Spinal cord injury scarring and inflammation:therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0631-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabinstein AA. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2018;24:551–566. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghava N, Das BC, Ray SK. Neuroprotective effects of estrogen in CNS injuries:insights from animal models. Neurosci Neuroecon. 2017;6:15–29. doi: 10.2147/NAN.S105134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray SK, Samantaray S, Smith JA, Matzelle DD, Das A, Banik NL. Inhibition of cysteine proteases in acute and chronic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:180–186. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach MJ, Chen Y, Kelly ML. Comparing blunt and penetrating trauma in spinal cord injury:analysis of long-term functional and neurological outcomes. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2018;24:121–132. doi: 10.1310/sci2402-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Sauri A, Orduña-Valls JM, Blasco-Serra A, Tornero-Tornero C, Cedeño DL, Bejarano-Quisoboni D, Valverde-Navarro AA, Benyamin R, Vallejo R. Glia to neuron ratio in the posterior aspect of the human spinal cord at thoracic segments relevant to spinal cord stimulation. J Anat. 2019;235:997–1006. doi: 10.1111/joa.13061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Setoguchi T, Nakashima K, Takizawa T, Yanagisawa M, Ochiai W, Okabe M, Yone K, Komiya S, Taga T. Treatment of spinal cord injury by transplantation of fetal neural precursor cells engineered to express BMP inhibitor. Exp Neurol. 2004;189:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith DR, Margul DJ, Dumont CM, Carlson MA, Munsell MK, Johnson M, Cummings BJ, Anderson AJ, Shea LD. Combinatorial lentiviral gene delivery of pro-oligodendrogenic factors for improving myelination of regenerating axons after spinal cord injury. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2019;116:155–167. doi: 10.1002/bit.26838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith WC, Harland RM. Expression cloning of noggin, a new dorsalizing factor localized to the Spemann organizer in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1992;70:829–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valenzuela DM, Economides AN, Rojas E, Lamb TM, Nuñez L, Jones P, Lp NY, Espinosa R, Brannan CI, Gilbert DJ. Identification of mammalian noggin and its expression in the adult nervous system. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6077–6084. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06077.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang HF, Liu XK, Li R, Zhang P, Chu Z, Wang CL, Liu HR, Qi J, Lv GY, Wang GY, Liu B, Li Y, Wang YY. Effect of glial cells on remyelination after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:1724–1732. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.217354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang TY, Park C, Zhang H, Rahimpour S, Murphy KR, Goodwin CR, Karikari IO, Than KD, Shaffrey CI, Foster N, Abd-El-Barr MM. Management of acute traumatic spinal cord injury:a review of the literature. Front Surg. 2021;8:698736. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.698736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warburton DE, Eng JJ, Krassioukov A, Sproule S, Team tSR. Cardiovascular health and exercise rehabilitation in spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2007;13:98–122. doi: 10.1310/sci1301-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witiw CD, Fehlings MG. Acute spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28:202–210. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wuermser LA, Ho CH, Chiodo AE, Priebe MM, Kirshblum SC, Scelza WM. Spinal cord injury medicine. 2. Acute care management of traumatic and nontraumatic injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:S55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao Q, Du Y, Wu W, Yip HK. Bone morphogenetic proteins mediate cellular response and, together with Noggin, regulate astrocyte differentiation after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2010;221:353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y, Huang M, He W, He C, Chen K, Hou J, Jiao Y, Liu R, Zou N, Liu L, Li C. Heterotopic ossification:clinical features, basic researches, and mechanical stimulations. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:770931. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.770931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang L, Liu S, Wang Y. Role of bone morphogenetic protein-2/4 in astrocyte activation in neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2019;15:1744806919892100. doi: 10.1177/1744806919892100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan YM, He C. The glial scar in spinal cord injury and repair. Neurosci Bull. 2013;29:421–435. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]