Summary

Background

The stroke burden in China has increased during the past 40 years. The present study aimed to determine the recent trends in the prevalence of stroke from 2013 to 2019 stratified by sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, age, residence, ethnicity, and province within a population-based screening project in China.

Methods

We made use of data generated from 2013 to 2019 in the China Stroke High-risk Population Screening Program. All living subjects with confirmed stroke at interview were considered to have prevalent stroke. All analyses of prevalence of stroke were weighted and results were presented as percentage and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Findings

A total of 4229,616 Chinese adults aged ≥40 years from 227 cities in the 31 provinces were finally included. The enrollment rate ranged from 58.8% (2017) to 67.8% (2013). The weighted prevalence of stroke increased annually from 2013 to 2019, being 2.28% (95% CI: 2.28–2.28%) in 2013, 2.34% (2.34–2.35%) in 2014, 2.43% (2.43–2.43%) in 2015, 2.48% (2.48–2.48%) in 2016, 2.52% (2.52–2.52%) in 2017, 2.55% (2.55–2.55%) in 2018, and 2.58% (2.58–2.58%) in 2019 (p for trend <0.001). The weighted prevalence of stroke was higher for male sex, older age, and residence in rural and northeast areas.

Interpretation

The prevalence of stroke in China and most provinces has continued to increase in the past 7 years (2013–2019). These findings, especially in provinces with high stroke prevalence, can help public health officials to increase province capacity for stroke and related risk factors prevention.

Fundings

This study was supported by grants from the National Major Public Health Service Projects.

Keywords: Stroke, Prevalence, China, Sociodemographic

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed from inception to January 31, 2021, for studies that had investigated the prevalence of stroke in China, using the search terms ("stroke" or "Ischemic stroke" or "hemorrhagic stroke" or "Chinese" and “Prevalence”) in articles published in English. Previous studies on prevalence of stroke in China were mainly cross-sectional studies in a single year or a few provinces, and lacked both ongoing research and subgroup analyses such as ethnicity and province.

Added value of this study

This study performed the first comprehensive assessment of the trends in prevalence of stroke in China from 2013 to 2019 stratified by sociodemographic characteristics. The findings showed large disparities in the prevalence of stroke by sex, age, residence, ethnicity, and province. During the 7-year study period, the weighted prevalence of stroke increased significantly from 2.28% to 2.58%. The three provinces of Shaanxi, Shandong, and Xinjiang had the most obvious increasing trends (all >20%). Furthermore, a nearly 2.5-fold difference in estimated prevalence of stroke was observed between northeast areas and southeast coastal areas.

Implications of all the available evidence

We conclude that stroke is one of the major public health challenges in China. The prevalence of stroke in China has continued to increase in the past 10 years and warrants a broad-based nationwide strategy for improved prevention as well as greater efforts in screening and more effective and affordable interventions.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

The stroke burden in China has increased during the past 40 years. In 2017, stroke was the leading cause of death, years of life lost, and disability-adjusted life-years at the national level in China.1 In 2013, a nationally representative door-to-door survey that included 480,687 adults aged ≥20 years showed that the age-standardized prevalence and incidence rate of stroke were 1114.8/100,000 people and 246.8/100,000 person-years, respectively.2

Ferri et al.3 reported that the prevalence of stroke in urban Chinese areas was nearly as high as that in industrialized countries. Wang et al.4 evaluated 15,438 residents from a township in Tianjin, and demonstrated that the incidence of stroke in rural China was increasing rapidly. Previous studies on prevalence of stroke in China were mainly cross-sectional studies in a single year or a few provinces, and lacked both ongoing research and subgroup analyses such as ethnicity and province.2,3, 4, 5 The present study aimed to determine the recent trends in prevalence of stroke from 2013 to 2019 stratified by sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, age, residence, ethnicity, and province within the population-based CSHPSIP in China.

Methods

To meet the challenge of stroke, the China Stroke Prevention Project Committee (CSPPC) was established in April 2011 in the Ministry of Health of China.6 The CSPPC launched the China Stroke High-risk Population Screening and Intervention Program (CSHPSIP) as a critical national project in 2011.6 Since 2013, the program has covered all 31 provinces across mainland China. We made use of data generated from January 2013 to December 2019 in the CSHPSIP, an ongoing population-based screening project that enrolled around 0.8 million community-dwelling adults aged ≥40 years each year from all 31 provinces in mainland China. Around 0.8 million community-dwelling adults aged ≥40 years was enrollment separately at each year from 2013 to 2019 through CSHPSIP (covering 0.15% of the target population across the country each year). The participating hospitals and screening sites in each province were determined according to the economic development status, population size, and work foundation. The enrollment criteria of community-dwelling adults were: (1) community residents aged ≥40 years (residence for >6 months) and (2) provision of informed consent. The demographic information (age, gender, and residence [urban and rural]) of participants among every province and city should be consistent with the 2010 Population Census of China.

Data were obtained from the Bigdata Observatory platform for Stroke of China (BOSC, formerly known as the China Stroke Data Center data reporting platform), and the data collection process was reported previously.5, 6, 7 Briefly, a two-stage stratified cluster sampling method was adopted for screening. In the first stage of sampling, a county/district proportional to the population size of that area was selected in each of the survey sites. In the next stage, in each selected location, at least one communities/villages with a total population of at least 4000 residents were selected by using the random sampling method. Participants completed a face-to-face interviewer-administered questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, body weight, height, abdominal circumference, marital status, education level, social healthcare insurance status, living condition, number of siblings or children), lifestyle factors (history of alcohol drinking and smoking, diet, consumption of vegetables and fruits), personal and family medical history (overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, transient ischemic attack [TIA], family history of stroke, physical inactivity), and current medications at the screening point by trained technicians using calibrated instruments with standard protocols. Physical inactivity was defined according to WHO recommendations standard (at least 150 min of moderate-intensity, or 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or any equivalent combination of the two). The CSHPSIP performs stroke screening nationwide each year and follow-up interventions for screened populations every 2 years (Supplementary methods and Table S1-2). The staff involved in the survey were trained in the program and evaluated by theoretical and practical tests.7 The Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University Xuanwu Hospital approved the trial protocol according to the Declaration of Helsinki (No. 2012045). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before entering the study.

Living subjects with confirmed stroke at interview were considered to have prevalent stroke. All patients with stroke (ischemic stroke [IS, I63{ICD-10}], intracerebral hemorrhage [ICH, I61], subarachnoid hemorrhage [SAH, I60], stroke of undetermined type) were recorded. Individuals with suspected stroke were reinterviewed by trained neurologists. The diagnosis of stroke required the investigator to provide a diagnosis certificate and/or an imaging certificate (CT/MRI) from a secondary or higher medical unit (Level II and above hospitals). TIA was defined as G45,8 and participants with TIA were excluded from the stroke group.

Physical activity was defined as regular physical exercise performed for >1 year, >2 times per week, and at least 30 minutes each time, or heavy physical labor. Obesity was defined as body mass index ≥28 kg/m2 in accordance with the guidelines established for Chinese adults.9 Hypertension was defined as: (1) systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg; (2) self-reported hypertension; (3) use of antihypertension medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as: (1) fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L; (2) self-reported diabetes mellitus; (3) use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin injections. Dyslipidemia was defined as: (1) abnormal fasting plasma markers (triglycerides ≥2.26 mmol/L, total cholesterol ≥6.22 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1.04 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥4.14 mmol/L); (2) self-reported dyslipidemia; (3) use of anti-dyslipidemia medications.10 Atrial fibrillation was defined as self-reported history of persistent atrial fibrillation or electrocardiogram (ECG) results (Supplementary methods).

Statistical analysis

We summarized continuous variables as mean with standard deviation and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. We assessed the characteristics of all participants according to participation year. Prevalence rate calculations were performed separately by sex (men/women), locality of residence (urban/rural), age (five groups), ethnic group (6 groups) and province region (31 groups). When results were not stratified by age, sex–and age–standardised rates were weighted to represent the overall national population. Sampling weights were multiplied by design (age, geographic location [central, east, west], and geographical area [urban, rural]), nonresponse, and post–stratification weights. Post–stratification weights were adjusted for residence (rural or urban), geographic location (northeast, north, northwest, southwest, south, central, or east), sex (male or female), and age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years) using the 2010 China census data. Weighted prevalence of stroke among different provinces in 2019 stratified by stroke type (IS, ICH and SAH), sex(men/women) and residence(rural/urban) was further assessed. All analyses accounted for complex sample design, including clustering, stratification, and sample weights (Supplementary methods) and results were presented as percentage and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Linear trends across study periods were assessed using orthogonal polynomial coefficients, and results with a p-value <0.05 were considered significant. For ordinal categorical variables, Rao–Scott χ2 tests were used to assess differences. The prevalence rates between the different groups were compared and results were expressed as absolute difference (95%CI) and odds ratio (OR, 95%CI). A p–value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done in SAS software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, version 9.4), and data was visualized in R version 4.0.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Role of funding source

The funders of the study had no role in the design or conduct of the study, including data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the results; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

A total of 4,229,616 Chinese adults aged ≥40 years from 223 cities in the 31 provinces were finally included (Tables S3–S4). The total number of enrolled people ranged from 513,147 (2016) to 723,571 (2013). The enrollment rate ranged from 58.8% (2017) to 67.8% (2013).

In provinces level, the enrollment rate ranged from 43.6% (Tianjin) to 85.7% (Jiangsu), Table S5. The sample size in the provinces ranged from 400 (Tibet, 2013) to 80,332 (Shandong, 2013). Characteristics of the study participants including from 2013 to 2019 are summarized in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Participants (≥40 Years), 2013–2019a.

| Characteristics | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 7,23,571 | 6,70,603 | 6,99,459 | 5,13,147 | 5,32,443 | 5,50,975 | 5,39,418 |

| Mean age (SD), years | 58±11.43 | 58±11.50 | 59±11.42 | 60±10.90 | 60±10.90 | 60±10.95 | 60±10.95 |

| Age groups | |||||||

| 40–49 | 2,14,596 (29.66) | 1,99,657 (29.77) | 1,73,388 (24.79) | 1,20,936 (23.57) | 1,06,639 (20.03) | 1,11,619 (20.26) | 1,02,680 (19.04) |

| 50–59 | 2,07,677 (28.7) | 1,94,421 (28.99) | 2,05,055 (29.32) | 1,50,304 (29.29) | 1,54,467 (29.01) | 1,63,645 (29.7) | 1,63,937 (30.39) |

| 60–69 | 1,80,945 (25.01) | 1,63,683 (24.41) | 1,87,078 (26.75) | 1,41,431 (27.56) | 1,63,125 (30.64) | 1,61,199 (29.26) | 1,55,229 (28.78) |

| 70–79 | 91,651 (12.67) | 84,000 (12.53) | 97,944 (14) | 73,561 (14.34) | 82,521 (15.5) | 88,394 (16.04) | 92,112 (17.08) |

| ≥80 | 28,702 (3.97) | 28,842 (4.3) | 35,994 (5.15) | 26,915 (5.25) | 25,691 (4.83) | 26,118 (4.74) | 25,460 (4.72) |

| Sex-Men | 3,30,053 (45.61) | 3,10,636 (46.32) | 3,19,706 (45.71) | 2,34,639 (45.73) | 2,28,987 (43.01) | 2,34,633 (42.59) | 2,25,551 (41.81) |

| Residence-urban | 3,72,814 (51.52) | 33,9970 (50.7) | 3,67,547 (52.55) | 2,59,307 (50.53) | 2,66,750 (50.1) | 2,80,487 (50.91) | 2,85,663 (52.96) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 24.0±3.32 | 24.2±4.02 | 24.0±3.40 | 24.3±3.51 | 24.3±3.51 | 24.5±3.51 | 24.5±3.48 |

| BMI group | |||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 17,468 (2.41) | 14,137 (2.11) | 16,692 (2.39) | 10,019 (1.95) | 12,044 (2.26) | 11,084 (2.01) | 11,374 (2.11) |

| 18.5–23.9 kg/m2 | 3,71,399 (51.33) | 3,44,638 (51.39) | 3,63,196 (51.93) | 2,60,116 (50.69) | 2,51,835 (47.3) | 2,54,260 (46.15) | 2,44,865 (45.39) |

| 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 | 2,64,144 (36.51) | 2,44,691 (36.49) | 2,55,108 (36.47) | 1,90,297 (37.08) | 2,04,848 (38.47) | 2,14,432 (38.92) | 2,13,569 (39.59) |

| >=28.0 kg/m2 | 70,560 (9.75) | 67,137 (10.01) | 64,463 (9.22) | 52,715 (10.27) | 63,716 (11.97) | 71,199 (12.92) | 69,610 (12.9) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Han | 7,02,930 (97.15) | 6,46,569 (96.42) | 6,73,765 (96.33) | 4,87,790 (95.06) | 5,08,396 (95.49) | 5,23,939 (95.09) | 5,19,747 (96.35) |

| Zhuang | 739 (0.10) | 666 (0.10) | 5578 (0.80) | 5259 (1.02) | 4463 (0.84) | 4054 (0.74) | 3353 (0.62) |

| Hui | 56,51 (0.78) | 5022 (0.75) | 3445 (0.49) | 4549 (0.89) | 3333 (0.63) | 4531 (0.82) | 2775 (0.51) |

| Manchu | 675 (0.09) | 879 (0.13) | 995 (0.14) | 1153 (0.22) | 1196 (0.22) | 1274 (0.23) | 970 (0.18) |

| Uygur | 1034 (0.14) | 2677 (0.4) | 1705 (0.24) | 1567 (0.31) | 758 (0.14) | 1776 (0.32) | 1328 (0.25) |

| Education | |||||||

| Compulsory education | 3,59,264 (76.00) | 3,22,719 (78.31) | 5,43,274 (77.94) | 4,02,892 (78.52) | 4,12,993 (77.57) | 4,29,446 (77.94) | 4,05,925 (75.26) |

| High School | 76,058 (16.09) | 62,103 (15.07) | 1,06,308 (15.25) | 81,138 (15.81) | 82,074 (15.42) | 85,797 (15.57) | 88,332 (16.38) |

| College and above | 37,411 (7.91) | 27,287 (6.62) | 47,442 (6.81) | 29,053 (5.66) | 37,360 (7.02) | 35,725 (6.48) | 45,108 (8.36) |

| Missing | 250838 | 258494 | 2435 | 64 | 16 | 7 | 53 |

| Annual income, CNY | |||||||

| <5000 | 982 (26.28) | 2791 (55.86) | 1,97,267 (28.3) | 1,48,046 (29.03) | 1,47,014 (27.61) | 1,50,167 (27.26) | 1,32,006 (24.47) |

| 5000–10,000 | 699 (18.71) | 510 (10.21) | 1,18,184 (16.96) | 88,560 (17.36) | 82,350 (15.47) | 86,481 (15.7) | 81,478 (15.1) |

| 10,000–20,000 | 537 (14.37) | 413 (8.27) | 1,25,005 (17.94) | 79,737 (15.63) | 86,961 (16.33) | 85,724 (15.56) | 83,953 (15.56) |

| >20,000 | 1518 (40.63) | 1282 (25.66) | 2,56,517 (36.8) | 1,93,701 (37.98) | 2,16,094 (40.59) | 2,28,581 (41.49) | 2,41,976 (44.86) |

| Missing | 7,19,835 | 6,65,607 | 2486 | 3103 | 24 | 22 | 5 |

| MI: own expense | 7529 (1.26) | 4509 (0.92) | 7509 (1.07) | 2965 (0.58) | 2088 (0.39) | 2586 (0.47) | 1634 (0.30) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 4,57,442 (95.19) | 3,97,006 (94.71) | 6,56,608 (94.1) | 4,86,044 (94.73) | 4,94,505 (92.88) | 5,13,864 (93.27) | 4,97,976 (92.74) |

| Single | 1046 (0.22) | 3350 (0.8) | 5844 (0.84) | 3601 (0.7) | 4983 (0.94) | 4898 (0.89) | 4045 (0.75) |

| Widowed | 18,436 (3.84) | 15,958 (3.81) | 30,826 (4.42) | 19,545 (3.81) | 27,889 (5.24) | 27,127 (4.92) | 29,802 (5.55) |

| Missing | 2,43,007 | 2,51,416 | 1661 | 69 | 10 | 37 | 2486 |

| Vascular risk factors | |||||||

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Nonsmokers | 6,05,493 (83.68) | 5,67,071 (84.56) | 5,83,880 (83.48) | 4,33,859 (84.55) | 4,50,197 (84.55) | 4,67,543 (84.86) | 4,58,539 (85.01) |

| Past smokers | 9644 (1.33) | 6499 (0.97) | 12,826 (1.83) | 9877 (1.92) | 8745 (1.64) | 7965 (1.45) | 8015 (1.49) |

| Current smokers | 1,08,434 (14.99) | 97,033 (14.47) | 1,02,753 (14.69) | 69,411 (13.53) | 73,501 (13.80) | 75,467 (13.70) | 72,864 (13.51) |

| Consumption of alcohol | 29,372 (13.19) | 24,481 (16.02) | 82,571 (11.8) | 56,683 (11.05) | 85,831 (16.21) | 90,555 (16.44) | 90,307 (16.74) |

| Family history of stroke | 55,459 (7.66) | 47,250 (7.05) | 81,494 (11.65) | 40,485 (7.89) | 51,294 (9.63) | 55,168 (10.01) | 53,850 (9.98) |

| Hypertensionb | 2,81,850 (38.95) | 2,67,116 (39.83) | 2,81,408 (40.23) | 2,08,965 (40.72) | 2,40,567 (45.18) | 2,50,459 (45.46) | 2,46,178 (45.64) |

| Diabetesb | 1,14,304 (15.8) | 1,07,861 (16.08) | 1,14,157 (16.32) | 83,862 (16.34) | 1,14,256 (21.46) | 1,19,902 (21.76) | 1,17,205 (21.73) |

| Hyperlipidemiab | 2,47,329 (34.18) | 2,34,903 (35.03) | 2,46,239 (35.2) | 1,80,821 (35.24) | 2,14,915 (40.36) | 2,23,692 (40.6) | 2,21,574 (41.08) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7769 (1.07) | 7228 (1.08) | 6701 (0.96) | 5376 (1.05) | 5732 (1.08) | 5986 (1.09) | 6399 (1.19) |

| Obesityc | 70,181 (9.7) | 66,882 (9.97) | 64,183 (9.18) | 52,499 (10.23) | 63,254 (11.88) | 70,879 (12.86) | 69,247 (12.84) |

| Lack of exercise | 1,89,339 (26.17) | 1,40,942 (21.02) | 2,17,003 (31.02) | 1,54,214 (30.05) | 1,51,030 (28.37) | 1,49,891 (27.2) | 1,47,580 (27.36) |

| TIA | 11,949 (1.65) | 11,992 (1.79) | 12,480 (1.78) | 9748 (1.9) | 9731 (1.83) | 9912 (1.8) | 9842 (1.82) |

| Stroke | 19,402 (2.68) | 19,291 (2.88) | 20,894 (2.99) | 16,574 (3.23) | 18,277 (3.43) | 18,791 (3.41) | 19,466 (3.61) |

The results were presented as n (percentages) for categorical variables and as mean (Standard deviation, SD) for continuous variables. The 2010 China Census data: male ratio: 51.27%; age stratification (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, ≥80years): 38.2%, 28.2%, 18.9%, 10.7%, 4.0%; urban population ratio: 49.68%.

Diagnostic criteria were a self-reported diagnosis from 2013 to 2016.

Obesity was defined as BMI≥28.0 kg/m2.

BMI, Body Mass Index; CNY, Chinese Yuan Renminbi; TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack; MI, Medical insurance; SD, Standard Deviation.

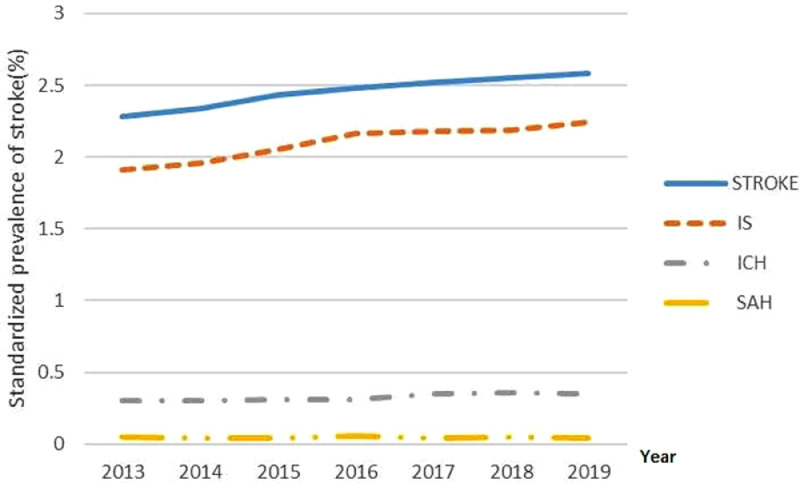

The weighted prevalence of stroke increasing annually from 2013 to 2019, being 2.28% (95% CI: 2.28–2.28%) in 2013, 2.34% (2.34–2.35%) in 2014, 2.43% (2.43–2.43%) in 2015, 2.48% (2.48–2.48%) in 2016, 2.52% (2.52–2.52%) in 2017, 2.55% (2.55–2.55%) in 2018, and 2.58% (2.58–2.58%) in 2019 (p for trend <0.001). From 2013 to 2019, the prevalence of stroke increased by 13.2%, and the annual increase rate was 2.2%. During this time, the prevalence of stroke in male participants and urban areas increased significantly (male vs. female: 18.1% vs. 7.3%, P<0.001; urban vs. rural: 18.6% vs. 9.9%, P<0.001) (Table 2). The weighted prevalence of IS, ICH, and SAH in 2019 were 2.24% (95%CI, 2.24–2.24%), 0.35% (0.35–0.35%), and 0.04% (0.04–0.04%), respectively. The results of other years are also presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years, a by Sex, residence, age, ethnic and provinces—China Stroke High-risk Population Screening and intervention program, 2013–2019.

| Characteristic | 2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | |

| Total | 7,25,332 | 19,402 | 2.28 (2.28,2.28) | 6,70,603 | 19291 | 2.34 (2.34,2.35) | 6,99,459 | 20,894 | 2.43 (2.43,2.43) |

| IS | 16,876 | 1.91 (1.91–1.91) | 16,785 | 1.96 (1.95–1.96) | 18,180 | 2.05 (2.05–2.05) | |||

| ICH | 2325 | 0.30 (0.29–0.30) | 2301 | 0.30 (0.30–0.30) | 2495 | 0.31 (0.31,0.31) | |||

| SAH | 286 | 0.05 (0.05–0.05) | 282 | 0.04 (0.04–0.04) | 306 | 0.04 (0.045,0.04) | |||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 3,29,858 | 9797 | 2.49 (2.49,2.50) | 3,10,636 | 9756 | 2.53 (2.53,2.54) | 3,19,706 | 10,507 | 2.62 (2.62,2.62) |

| Female | 3,95,474 | 9605 | 2.07 (2.06,2.07) | 3,59,967 | 9535 | 2.15 (2.15,2.15) | 3,9,753 | 10,387 | 2.23 (2.23,2.23) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 3,52,181 | 9119 | 2.32 (2.32,2.32) | 3,30,633 | 9876 | 2.48 (2.48,2.48) | 3,31,912 | 9757 | 2.56 (2.55,2.56) |

| Urban | 3,73,151 | 10,283 | 2.21 (2.21,2.22) | 3,39,970 | 9415 | 2.15 (2.15,2.15) | 3,67,547 | 11,137 | 2.26 (2.26,2.26) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Age, years | |||||||||

| 40–49 | 2,14,375 | 1332 | 0.62 (0.62,0.62) | 1,99,657 | 1168 | 0.58 (0.57,0.58) | 1,73,388 | 1096 | 0.60 (0.60,0.60) |

| 50–59 | 2,07,600 | 4259 | 2.14 (2.13,2.14) | 1,94,421 | 4189 | 2.14 (2.14,2.14) | 2,05,055 | 3961 | 2.19 (2.19,2.19) |

| 60–69 | 1,81,663 | 7683 | 4.24 (4.23,4.24) | 1,63,683 | 7923 | 4.62 (4.61,4.62) | 1,87,078 | 8099 | 4.47 (4.47,4.48) |

| 70–79 | 91,474 | 4894 | 5.30 (5.30,5.31) | 84,000 | 4809 | 5.51 (5.50,5.51) | 97,944 | 5905 | 6.03 (6.03,6.04) |

| ≥80 | 28,656 | 1234 | 4.06 (4.05,4.07) | 28,842 | 1202 | 3.87 (3.86,3.88) | 35,994 | 1833 | 4.69 (4.68,4.70) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| Han | 7,04,629 | 18,787 | 2.27 (2.27,2.27) | 6,46,569 | 18644 | 2.36 (2.36,2.37) | 6,73,765 | 20,352 | 2.47 (2.46,2.47) |

| Zhuang | 739 | 9 | 0.99 (0.97,1.02) | 666 | 11 | 1.04 (1.03,1.07) | 5578 | 72 | 1.07 (1.06,1.07) |

| Hui | 5657 | 146 | 2.38 (2.36,2.39) | 5022 | 141 | 2.29 (2.28,2.31) | 3445 | 92 | 2.34 (2.32,2.35) |

| Manchu | 2991 | 134 | 3.18 (3.15,3.20) | 6110 | 262 | 3.50 (3.48,3.52) | 2985 | 139 | 4.50 (4.48,4.53) |

| Uyghur | 1034 | 25 | 1.14 (1.14,1.16) | 2677 | 41 | 1.05 (1.03,1.06) | 1705 | 26 | 1.14 (1.13,1.15) |

| Mongolian | 4337 | 132 | 3.31 (3.29,3.33) | 3852 | 161 | 3.48 (3.45,3.50) | 2784 | 106 | 3.35 (3.33,3.37) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Provinces | |||||||||

| Beijing | 38,626 | 1105 | 2.47 (2.46,2.48) | 25,170 | 765 | 2.56 (2.54,2.57) | 15,648 | 460 | 2.60 (2.59,2.61) |

| Tianjin | 19,448 | 555 | 2.51 (2.49,2.52) | 16,281 | 494 | 2.58 (2.57,2.60) | 10,848 | 323 | 2.62 (2.61,2.64) |

| Hebei | 46,326 | 1180 | 2.82 (2.81,2.83) | 49,172 | 1516 | 2.93 (2.93,2.94) | 32,970 | 1259 | 3.04 (3.04,3.05) |

| Shanxi | 28,805 | 800 | 2.54 (2.53,2.55) | 41,021 | 957 | 2.61 (2.61,2.62) | 27,322 | 784 | 2.69 (2.68,2.70) |

| IM | 20,355 | 689 | 3.38 (3.37,3.39) | 14,599 | 546 | 3.51 (3.50,3.52) | 15,166 | 613 | 3.57 (3.56,3.58) |

| Liaoning | 27,962 | 1213 | 3.39 (3.38,3.39) | 32,920 | 1430 | 3.50 (3.49,3.51) | 28,048 | 1194 | 3.57 (3.56,3.58) |

| Jilin | 23,869 | 926 | 3.46 (3.45,3.47) | 30,320 | 1379 | 3.56 (3.55,3.57) | 23,660 | 518 | 3.63 (3.62,3.64) |

| Heilongjiang | 25,565 | 952 | 3.53 (3.53,3.54) | 28,511 | 1234 | 3.65 (3.64,3.66) | 33,946 | 1151 | 3.74 (3.73,3.75) |

| Shanghai | 5860 | 140 | 1.91 (1.89,1.93) | 5892 | 128 | 1.97 (1.95,1.98) | 4148 | 130 | 1.98 (1.97,2.00) |

| Jiangsu | 49,281 | 998 | 1.78 (1.77,1.78) | 48,101 | 1031 | 1.84 (1.83,1.84) | 51,787 | 1297 | 1.88 (1.88,1.89) |

| Zhejiang | 18,707 | 445 | 2.01 (2.00,2.02) | 17,911 | 407 | 2.09 (2.09,2.10) | 26,891 | 694 | 2.13 (2.12,2.14) |

| Anhui | 26,207 | 904 | 2.28 (2.28,2.29) | 30,385 | 1012 | 2.37 (2.37,2.38) | 24,746 | 1088 | 2.47 (2.46,2.48) |

| Fujian | 3744 | 79 | 1.84 (1.82,1.86) | 5912 | 120 | 1.89 (1.88,1.91) | 4871 | 153 | 1.94 (1.92,1.95) |

| Jiangxi | 20,893 | 686 | 1.97 (1.96,1.98) | 11,306 | 280 | 1.99 (1.99,2.00) | 30,850 | 1095 | 2.06 (2.05,2.06) |

| Shandong | 80,332 | 2075 | 2.21 (2.20,2.21) | 68,342 | 1945 | 2.30 (2.30,2.30) | 70,882 | 2083 | 2.39 (2.39,2.40) |

| Henan | 66,523 | 2273 | 2.75 (2.75,2.76) | 43,514 | 1344 | 2.87 (2.87,2.88) | 71,513 | 2854 | 2.96 (2.95,2.96) |

| Hubei | 39,151 | 754 | 1.98 (1.98,1.99) | 20,345 | 552 | 2.06 (2.05,2.06) | 32,473 | 843 | 2.11 (2.11,2.12) |

| Hunan | 23,537 | 637 | 1.97 (1.96,1.97) | 26,971 | 863 | 2.00 (2.00,2.01) | 32,239 | 980 | 2.04 (2.03,2.05) |

| Guangdong | 27,973 | 345 | 1.47 (1.46,1.47) | 15,761 | 337 | 1.52 (1.51,1.53) | 13,187 | 283 | 1.54 (1.54,1.55) |

| Guangxi | 15,667 | 117 | 1.52 (1.51,1.53) | 13,034 | 171 | 1.56 (1.56,1.57) | 29,664 | 358 | 1.60 (1.60,1.61) |

| Hainan | 3437 | 53 | 1.58 (1.57,1.60) | 5263 | 118 | 1.65 (1.64,1.66) | 2026 | 44 | 1.67 (1.65,1.68) |

| Chongqing | 14,192 | 260 | 1.64 (1.64,1.65) | 5927 | 117 | 1.71 (1.69,1.72) | 12,810 | 246 | 1.75 (1.74,1.76) |

| Sichuan | 36,544 | 666 | 1.63 (1.63,1.64) | 33,307 | 681 | 1.70 (1.69,1.70) | 27,884 | 609 | 1.73 (1.72,1.73) |

| Guizhou | 762 | 37 | 1.67 (1.66,1.69) | 7127 | 122 | 1.76 (1.75,1.76) | 9226 | 162 | 1.79 (1.78,1.79) |

| Yunnan | 4697 | 147 | 1.59 (1.58,1.60) | 11,913 | 219 | 1.64 (1.64,1.64) | 20,780 | 340 | 1.66 (1.65,1.66) |

| Tibet | 400 | 9 | 2.01 (1.97,2.05) | 578 | 14 | 2.11 (2.09,2.13) | 833 | 20 | 2.18 (2.16,2.20) |

| Shaanxi | 17,118 | 494 | 2.20 (2.19,2.21) | 28,005 | 591 | 2.30 (2.30,2.31) | 24,675 | 700 | 2.33 (2.33,2.34) |

| Gansu | 15,423 | 396 | 1.98 (1.97,1.98) | 13,922 | 442 | 2.05 (2.03,2.06) | 5702 | 177 | 2.05 (2.03,2.06) |

| Qinghai | 4249 | 112 | 1.94 (1.92,1.95) | 6332 | 146 | 2.01 (2.00,2.02) | 3531 | 88 | 2.05 (2.03,2.08) |

| Ningxia | 9650 | 145 | 1.94 (1.93,1.96) | 3680 | 95 | 2.02 (2.01,2.04) | 2457 | 73 | 2.07 (2.05,2.09) |

| Xinjiang | 8278 | 210 | 1.95 (1.94,1.96) | 9081 | 235 | 2.03 (2.01,2.04) | 8676 | 275 | 2.06 (2.05,2.07) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Characteristic | 2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | |

| Total | 5,13,147 | 16,574 | 2.48 (2.48,2.48) | 5,32,243 | 18277 | 2.52 (2.52,2.52) | 5,50,975 | 18,791 | 2.55 (2.55,2.55) |

| IS | 14,697 | 2.16 (2.16,2.17) | 16,090 | 2.18 (2.18,2.18) | 16,414 | 2.19 (2.19,2.19) | |||

| ICH | 1815 | 0.31 (0.31,0.31) | 2272 | 0.35 (0.35,0.35) | 2366 | 0.36 (0.36,0.36) | |||

| SAH | 384 | 0.06 (0.06,0.06) | 300 | 0.04 (0.045,0.04) | 351 | 0.05 (0.05,0.05) | |||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 2,34,644 | 8315 | 2.70 (2.70,2.70) | 2,29,322 | 8991 | 2.76 (2.76,2.76) | 2,34,488 | 9279 | 2.85 (2.85,2.85) |

| Female | 2,78,503 | 8266 | 2.26 (2.26,2.26) | 3,02,921 | 9286 | 2.27 (2.27,2.27) | 3,16,487 | 9522 | 2.25 (2.25,2.26) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 2,53,843 | 8678 | 2.62 (2.62,2.63) | 2,65,983 | 8680 | 2.58 (2.57,2.58) | 2,70,332 | 8995 | 2.60 (2.60,2.60) |

| Urban | 25,9304 | 7903 | 2.29 (2.29,2.29) | 2,66,260 | 9597 | 2.43 (2.43,2.43) | 2,80,643 | 9806 | 2.49 (2.48,2.49) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.0005 | ||||||

| Age, years | |||||||||

| 40–49 | 1,20,936 | 667 | 0.53 (0.53,0.53) | 1,06,832 | 619 | 0.57 (0.57,0.57) | 1,11,647 | 599 | 0.57 (0.57,0.57) |

| 50–59 | 1,50,300 | 2825 | 2.11 (2.10,2.11) | 1,54,720 | 2974 | 2.12 (2.12,2.12) | 1,63,473 | 3154 | 2.09 (2.09,2.09) |

| 60–69 | 1,41,432 | 6725 | 4.64 (4.64,4.65) | 1,62,329 | 7488 | 4.52 (4.52,4.53) | 1,61,276 | 7563 | 4.70 (4.70,4.71) |

| 70–79 | 73,565 | 4863 | 6.62 (6.61,6.63) | 82,637 | 5551 | 6.71 (6.71,6.72) | 88,451 | 5826 | 6.81 (6.81,6.82) |

| ≥80 | 26,917 | 1501 | 5.18 (5.18,5.19) | 25,725 | 1645 | 5.95 (5.94,5.96) | 26,128 | 1659 | 6.01 (6.00,6.02) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| Han | 4,87,797 | 15,982 | 2.54 (2.54,2.54) | 5,09,130 | 17462 | 2.51 (2.51,2.51) | 5,24,182 | 17,892 | 2.56 (2.56,2.56) |

| Zhuang | 5259 | 86 | 1.15 (1.14,1.15) | 4463 | 96 | 1.24 (1.23,1.25) | 4054 | 79 | 1.30 (1.29,1.31) |

| Hui | 4549 | 137 | 2.66 (2.64,2.67) | 3340 | 142 | 2.72 (2.71,2.73) | 4531 | 212 | 2.84 (2.82,2.85) |

| Manchu | 5429 | 212 | 2.91 (2.89,2.92) | 2285 | 129 | 4.07 (4.05,4.10) | 5300 | 222 | 3.15 (3.13,3.16) |

| Uyghur | 1567 | 33 | 1.32 (1.30,1.35) | 798 | 18 | 1.75 (1.73,1.76) | 1776 | 39 | 1.55 (1.54,1.57) |

| Mongolian | 2700 | 102 | 3.24 (3.22,3.25) | 2630 | 79 | 3.11 (3.09,3.13) | 1933 | 47 | 2.92 (2.89,2.95) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Provinces | |||||||||

| Beijing | 13,021 | 436 | 2.67 (2.66,2.69) | 9411 | 307 | 2.72 (2.70,2.73) | 9863 | 330 | 2.78 (2.76,2.79) |

| Tianjin | 13,518 | 462 | 2.68 (2.67,2.70) | 6666 | 227 | 2.72 (2.71,2.74) | 6735 | 218 | 2.72 (2.70,2.74) |

| Hebei | 36,568 | 1365 | 3.16 (3.16,3.17) | 26,553 | 1331 | 3.23 (3.22,3.23) | 36,809 | 1636 | 3.29 (3.28,3.29) |

| Shanxi | 28,908 | 823 | 2.79 (2.79,2.80) | 16,883 | 609 | 2.81 (2.80,2.81) | 16,729 | 577 | 2.84 (2.84,2.85) |

| IM | 9050 | 361 | 3.70 (3.69,3.71) | 12,610 | 504 | 3.70 (3.69,3.71) | 12,884 | 484 | 3.78 (3.77,3.79) |

| Liaoning | 22,449 | 1132 | 3.68 (3.67,3.68) | 26,426 | 1173 | 3.70 (3.69,3.70) | 20,843 | 1053 | 3.79 (3.78,3.80) |

| Jilin | 21,807 | 878 | 3.77 (3.76,3.78) | 15,368 | 800 | 3.81 (3.80,3.82) | 10,344 | 548 | 3.94 (3.93,3.95) |

| Heilongjiang | 14,737 | 737 | 3.89 (3.87,3.90) | 21,228 | 675 | 3.93 (3.92,3.94) | 14,436 | 985 | 3.99 (3.98,4.00) |

| Shanghai | 4015 | 90 | 2.03 (2.02,2.05) | 4524 | 204 | 2.00 (1.99,2.02) | 12,695 | 466 | 2.06 (2.05,2.06) |

| Jiangsu | 38,990 | 994 | 1.95 (1.94,1.95) | 39,431 | 1257 | 1.97 (1.97,1.98) | 36,877 | 1100 | 2.01 (2.00,2.01) |

| Zhejiang | 17,206 | 442 | 2.19 (2.19,2.20) | 27,041 | 699 | 2.19 (2.18,2.20) | 21,858 | 589 | 2.26 (2.25,2.26) |

| Anhui | 17,092 | 572 | 2.58 (2.57,2.58) | 23,456 | 1165 | 2.58 (2.57,2.58) | 31,134 | 954 | 2.68 (2.67,2.68) |

| Fujian | 10,019 | 294 | 2.00 (1.99,2.01) | 6813 | 217 | 1.98 (1.97,1.99) | 12,778 | 307 | 2.03 (2.02,2.03) |

| Jiangxi | 11,560 | 318 | 2.15 (2.14,2.15) | 17,307 | 647 | 2.15 (2.15,2.16) | 15,066 | 592 | 2.15 (2.14,2.16) |

| Shandong | 56,958 | 1867 | 2.50 (2.49,2.50) | 50,833 | 1577 | 2.51 (2.50,2.51) | 52,420 | 1714 | 2.59 (2.59,2.60) |

| Henan | 40,419 | 1520 | 3.07 (3.07,3.08) | 43,007 | 1594 | 3.11 (3.11,3.12) | 44,255 | 1925 | 3.20 (3.19,3.20) |

| Hubei | 18,046 | 652 | 2.19 (2.18,2.20) | 20,814 | 778 | 2.21 (2.21,2.22) | 21,470 | 651 | 2.26 (2.25,2.27) |

| Hunan | 24,409 | 831 | 2.13 (2.13,2.14) | 28,961 | 875 | 2.10 (2.10,2.11) | 23,433 | 802 | 2.12 (2.11,2.12) |

| Guangdong | 4894 | 105 | 1.58 (1.57,1.59) | 11,053 | 264 | 1.58 (1.58,1.59) | 13,672 | 287 | 1.62 (1.62,1.63) |

| Guangxi | 23,799 | 405 | 1.65 (1.64,1.65) | 20,959 | 495 | 1.64 (1.63,1.64) | 21,278 | 456 | 1.64 (1.63,1.64) |

| Hainan | 2973 | 79 | 1.73 (1.72,1.74) | 3513 | 80 | 1.69 (1.68,1.70) | 3706 | 120 | 1.75 (1.74,1.77) |

| Chongqing | 5072 | 124 | 1.82 (1.81,1.84) | 8574 | 214 | 1.83 (1.82,1.84) | 8374 | 193 | 1.85 (1.83,1.86) |

| Sichuan | 14,626 | 350 | 1.79 (1.79,1.80) | 29,869 | 764 | 1.81 (1.81,1.82) | 35,746 | 881 | 1.86 (1.86,1.87) |

| Guizhou | 7347 | 123 | 1.85 (1.84,1.85) | 6326 | 162 | 1.84 (1.83,1.84) | 9160 | 154 | 1.87 (1.86,1.87) |

| Yunnan | 8398 | 224 | 1.73 (1.72,1.73) | 17,740 | 340 | 1.73 (1.72,1.73) | 16,334 | 413 | 1.75 (1.74,1.75) |

| Tibet | 873 | 21 | 2.28 (2.26,2.29) | 1113 | 24 | 2.26 (2.25,2.27) | 1177 | 26 | 2.30 (2.28,2.31) |

| Shaanxi | 19,492 | 500 | 2.43 (2.42,2.43) | 18,067 | 706 | 2.45 (2.44,2.46) | 18,418 | 645 | 2.55 (2.55,2.56) |

| Gansu | 8959 | 356 | 2.14 (2.13,2.15) | 4425 | 157 | 2.15 (2.14,2.16) | 7525 | 240 | 2.21 (2.19,2.22) |

| Qinghai | 5156 | 141 | 2.14 (2.13,2.15) | 3549 | 97 | 2.19 (2.17,2.20) | 3417 | 115 | 2.21 (2.20,2.22) |

| Ningxia | 6342 | 169 | 2.18 (2.17,2.19) | 5533 | 189 | 2.22 (2.21,2.23) | 4502 | 128 | 2.30 (2.28,2.31) |

| Xinjiang | 6444 | 210 | 2.14 (2.13,2.16) | 4190 | 146 | 2.17 (2.16,2.19) | 7037 | 212 | 2.27 (2.26,2.28) |

| P | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Characteristic | 2019 |

A relative change from 2013 to 2019, % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Stroke | % (95%CI) | |||||||

| Total | 5,39,418 | 19,466 | 2.58 (2.58,2.58) | 13.16% | |||||

| IS | 17,304 | 2.24 (2.24,2.24) | 17.28% | ||||||

| ICH | 2232 | 0.35 (0.35,0.35) | 16.27% | ||||||

| SAH | 278 | 0.04 (0.04,0.04) | −5.05% | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 2,25,551 | 9597 | 2.94 (2.93,2.94) | 18.07% | |||||

| Female | 3,13,867 | 9869 | 2.22 (2.22,2.22) | 7.25% | |||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 2,53,755 | 8576 | 2.55 (2.55,2.55) | 9.91% | |||||

| Urban | 2,85,663 | 10,890 | 2.62 (2.61,2.62) | 18.55% | |||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Age, years | |||||||||

| 40–49 | 1,02,680 | 562 | 0.53 (0.52,0.53) | −14.52% | |||||

| 50–59 | 1,63,937 | 3150 | 2.14 (2.14,2.15) | 0.00% | |||||

| 60–69 | 1,55,229 | 7602 | 4.70 (4.70,4.71) | 10.85% | |||||

| 70–79 | 92,112 | 6413 | 7.00 (6.99,7.00) | 32.08% | |||||

| ≥80 | 25,460 | 1739 | 6.30 (6.29,6.31) | 55.17% | |||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Ethnic group | |||||||||

| Han | 5,19,747 | 18,855 | 2.62 (2.62,2.62) | 15.42% | |||||

| Zhuang | 3353 | 78 | 1.43 (1.41,1.44) | 44.44% | |||||

| Hui | 2775 | 106 | 3.02 (3.00,3.04) | 26.89% | |||||

| Manchu | 3717 | 174 | 3.25 (3.23,3.27) | 2.20% | |||||

| Uyghur | 1328 | 27 | 1.68 (1.66,1.70) | 47.37% | |||||

| Mongolian | 1538 | 54 | 3.19 (3.17,3.21) | -3.63% | |||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Provinces | |||||||||

| Beijing | 4290 | 133 | 2.83 (2.81,2.85) | 14.57% | |||||

| Tianjin | 6842 | 230 | 2.76 (2.74,2.77) | 9.96% | |||||

| Hebei | 23,871 | 1154 | 3.35 (3.35,3.36) | 18.79% | |||||

| Shanxi | 16,899 | 644 | 2.87 (2.86,2.88) | 12.99% | |||||

| IM | 10,562 | 385 | 3.82 (3.81,3.83) | 13.02% | |||||

| Liaoning | 26,068 | 1375 | 3.82 (3.82,3.83) | 12.68% | |||||

| Jilin | 15,761 | 989 | 4.02 (4.01,4.03) | 16.18% | |||||

| Heilongjiang | 21,703 | 1207 | 4.07 (4.06,4.08) | 15.30% | |||||

| Shanghai | 5387 | 197 | 2.08 (2.06,2.09) | 8.90% | |||||

| Jiangsu | 43,819 | 1364 | 2.02 (2.02,2.03) | 13.48% | |||||

| Zhejiang | 21,311 | 693 | 2.30 (2.29,2.31) | 14.43% | |||||

| Anhui | 18,214 | 712 | 2.71 (2.71,2.72) | 18.86% | |||||

| Fujian | 10,142 | 283 | 2.04 (2.03,2.05) | 10.87% | |||||

| Jiangxi | 18,789 | 634 | 2.16 (2.16,2.17) | 9.64% | |||||

| Shandong | 52,966 | 1791 | 2.66 (2.66,2.67) | 20.36% | |||||

| Henan | 44,790 | 1774 | 3.27 (3.27,3.28) | 18.91% | |||||

| Hubei | 17,563 | 532 | 2.30 (2.29,2.31) | 16.16% | |||||

| Hunan | 29,115 | 934 | 2.13 (2.12,2.13) | 8.12% | |||||

| Guangdong | 18,141 | 438 | 1.66 (1.66,1.67) | 12.93% | |||||

| Guangxi | 17,517 | 415 | 1.66 (1.65,1.66) | 9.21% | |||||

| Hainan | 3793 | 73 | 1.80 (1.79,1.81) | 13.92% | |||||

| Chongqing | 13,255 | 335 | 1.87 (1.86,1.88) | 14.02% | |||||

| Sichuan | 35,967 | 962 | 1.87 (1.87,1.88) | 14.72% | |||||

| Guizhou | 12,426 | 296 | 1.86 (1.86,1.87) | 11.38% | |||||

| Yunnan | 10,625 | 315 | 1.75 (1.74,1.76) | 10.06% | |||||

| Tibet | 940 | 35 | 2.31 (2.30,2.32) | 14.93% | |||||

| Shaanxi | 17,504 | 911 | 2.64 (2.64,2.65) | 20.00% | |||||

| Gansu | 8437 | 294 | 2.25 (2.24,2.26) | 13.64% | |||||

| Qinghai | 2818 | 68 | 2.24 (2.22,2.26) | 15.46% | |||||

| Ningxia | 4513 | 139 | 2.32 (2.31,2.33) | 19.59% | |||||

| Xinjiang | 5390 | 154 | 2.35 (2.34,2.36) | 20.51% | |||||

| P | <.0001 | ||||||||

Standardized prevalence of stroke adjusted to the 2010 China standard population, gender, age, regions, urban and rural; weighted estimates.

IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; IM, Inner Mongolia.

Figure 1.

Weighted prevalence of stroke stratified by subtypes among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years from 2103 to 2019. IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

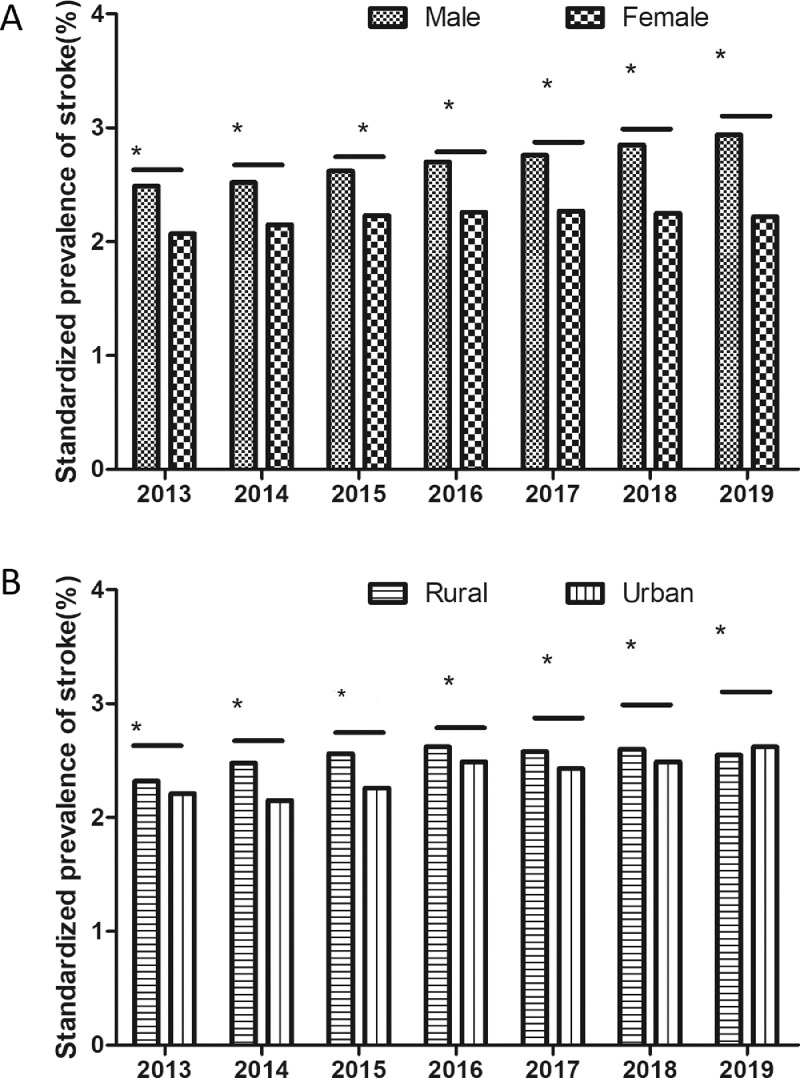

In 2019, the weighted prevalence of stroke was higher in male participants than in female participants (male vs. female: 2.94% vs. 2.22% [absolute difference: 0.70% {95% CI: 0.70–0.71%}; odds ratio {OR}: 1.21 {95% CI: 1.18–1.24}]). The same pattern appeared consistent from 2013 to 2018 (Figure 2A). From 2013 to 2018, the prevalence of stroke was higher in rural areas than in urban areas (rural vs. urban in 2018: 2.60% vs. 2.49% [absolute difference: 0.09% {95% CI: 0.08–0.10%}; OR: 1.05 {95% CI: 1.04–1.06}]), but the trend was reversed in 2019 (rural vs. urban: 2.55% vs. 2.62% [absolute difference: −0.06% {95% CI: −0.07% to −0.06%}; OR: 0.92 {95% CI: 0.90–0.94}]) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Weighted prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years stratified by sex and residence from 2013 to 2019. (A) Weighted prevalence of stroke among males and females from 2013 to 2019; (B) Weighted prevalence of stroke in urban and rural areas of China in from 2013 to 2019. * Represent. P<0.001.

The weighted prevalence of stroke was highest in persons aged 70–79 years in 2019, and a nearly 18-fold difference in estimated prevalence of stroke was observed between persons aged 70–79 years and 40–49 years (70–79 vs. 40–49: 7.00% vs. 0.53% [absolute difference: 6.12% {95% CI: 6.07–6.16%}; OR: 18.12 {95% CI: 18.01–18.26}]). The same pattern appeared consistent from 2013 to 2018. Meanwhile, from 2013 to 2019, the prevalence of stroke in persons aged 40–49 years declined by 14.5%, while that in persons aged ≥80 years increased by 55.2% (Table 2). The weighted prevalence of stroke varied substantially by ethnicity. From 2013 to 2019, the three ethnic groups with the highest prevalence were Manchu, Mongolian, and Hui. In 2019, the respective prevalence rates were 3.25% (95% CI: 3.23–3.27%), 3.19% (3.17–3.21%), and 3.02% (3.00–3.04%) (Table 2).

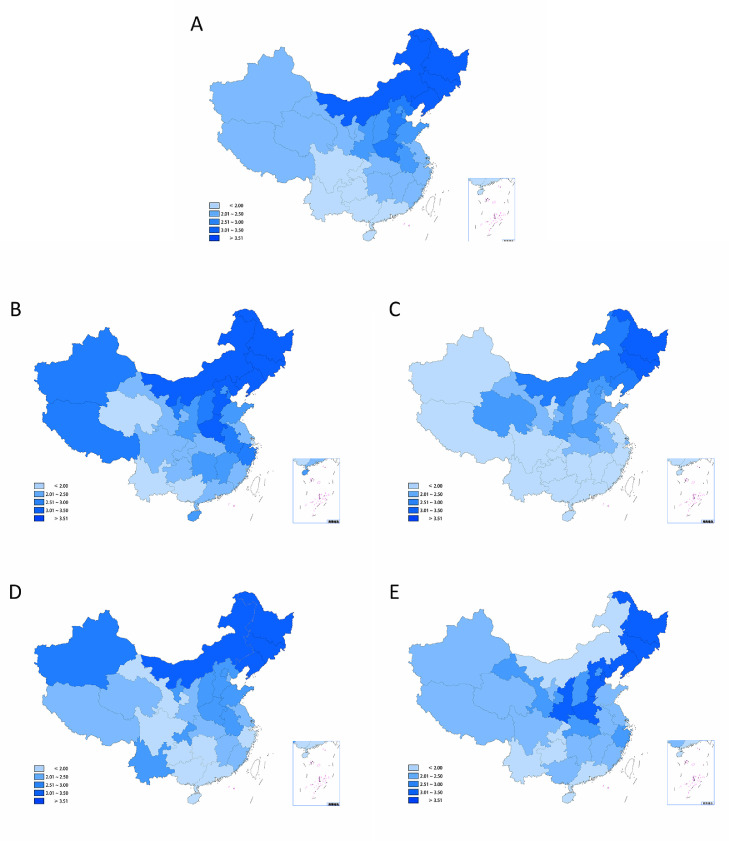

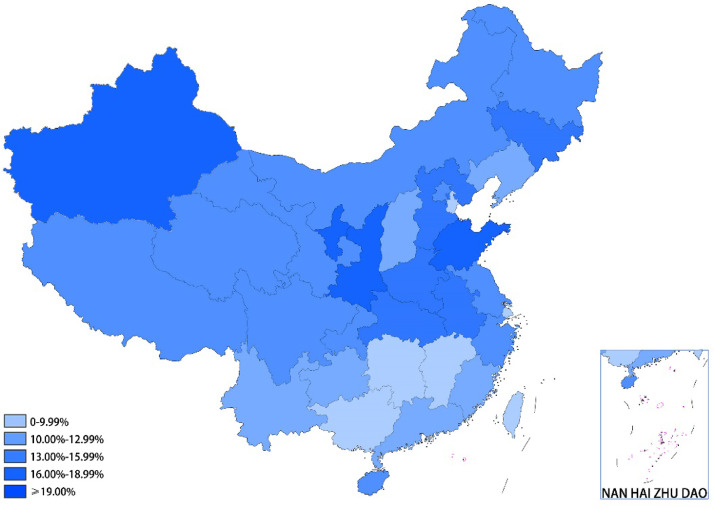

In 2013, the weighted prevalence of stroke ranged from 1.47% (Guangdong) to 3.53% (Heilongjiang). In 2019, the weighted prevalence of stroke ranged from 1.66% (Guangdong and Guangxi) to 4.07% (Heilongjiang) (Table 2). In 2019, the provinces in China with high prevalence of stroke exceeding 3.50% were generally in the northeast, while the provinces with low prevalence of stroke below 2.00% were generally in the south (Figure 3A and Table 3). For male and female participants, the prevalence of stroke ranged from 1.74% (Shanghai and Yunnan) to 4.56% (Liaoning) and from 1.05% (Tibet) to 3.80% (Jilin), respectively (Figure 3B–C and Table 3). Regarding rural and urban areas, the prevalence in rural areas ranged from 1.32% (Guangxi) to 4.91% (Inner Mongolia), and the prevalence in urban areas ranged from 0.74% (Hainan) to 5.70% (Shaanxi) (Figure 3D–E and Table 3). During the entire study period from 2013 to 2019, the prevalence of stroke in all provinces increased to varying degrees (Figure 4). The three provinces with the highest increases were Shaanxi (2.20% to 2.64%; 20.00%), Shandong (2.21% to 2.66%; 20.36%), and Xinjiang (1.95% to 2.35%; 20.51%), while the three provinces with the lowest increases were Hunan (1.97% to 2.13%; 8.12%), Shanghai (1.91% to 2.08%; 8.90%), and Guangxi (1.52% to 1.66%; 9.21%) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Weighted prevalence of stroke (%) among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years Stratified by sex and residence in the 31 provinces in China in 2019. (A) Weighted prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years (China map ID: 1012072252); (B) Weighted prevalence of stroke among males aged ≥ 40 years (China map ID: 1012051844); (C) Weighted prevalence of stroke among females aged ≥ 40 years (China map ID: 1012037076); (D) Weighted prevalence of stroke among rural residents aged ≥ 40 years (China map ID: 1012046738); (E) Weighted prevalence of stroke among urban residents aged ≥ 40 years (China map ID: 1012091064).

Table 3.

Weighted prevalence of stroke among different provinces in 2019a by classification, sex and residence(%[95%CI]).

| Provinces | All | Classification |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | ICH | SAH | ||

| Beijing | 2.83 (2.81,2.85) | 2.75 (2.73,2.77) | 0.15 (0.14,0.15) | 0.14 (0.14,0.15) |

| Tianjin | 2.76 (2.74,2.77) | 2.46 (2.45,2.47) | 0.30 (0.30,0.31) | 0.04 (0.03,0.04) |

| Hebei | 3.35 (3.35,3.36) | 2.82 (2.82,2.83) | 0.55 (0.54,0.55) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Shanxi | 2.87 (2.86,2.88) | 2.99 (2.98,3.00) | 0.26 (0.26,0.26) | 0.12 (0.12,0.12) |

| IM | 3.82 (3.81,3.83) | 3.62 (3.61,3.63) | 0.25 (0.25,0.25) | - |

| Liaoning | 3.82 (3.82,3.83) | 3.44 (3.44,3.45) | 0.46 (0.45,0.46) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Jilin | 4.02 (4.01,4.03) | 3.80 (3.79,3.81) | 0.30 (0.30,0.30) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Heilongjiang | 4.07 (4.06,4.08) | 3.73 (3.72,3.74) | 0.36 (0.35,0.36) | 0.04 (0.04,0.04) |

| Shanghai | 2.08 (2.06,2.09) | 1.94 (1.92,1.95) | 0.11 (0.10,0.11) | 0.04 (0.04,0.04) |

| Jiangsu | 2.02 (2.02,2.03) | 1.82 (1.81,1.82) | 0.21 (0.21,0.22) | 0.04 (0.04,0.04) |

| Zhejiang | 2.30 (2.29,2.31) | 1.78 (1.77,1.79) | 0.50 (0.50,0.51) | 0.06 (0.06,0.06) |

| Anhui | 2.71 (2.71,2.72) | 2.40 (2.39,2.41) | 0.31 (0.31,0.31) | 0.09 (0.08,0.09) |

| Fujian | 2.04 (2.03,2.05) | 1.76 (1.75,1.77) | 0.29 (0.28,0.29) | 0.02 (0.02,0.02) |

| Jiangxi | 2.16 (2.16,2.17) | 1.81 (1.80,1.82) | 0.35 (0.35,0.35) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Shandong | 2.66 (2.66,2.67) | 2.32 (2.32,2.32) | 0.36 (0.36,0.36) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Henan | 3.27 (3.27,3.28) | 2.86 (2.86,2.87) | 0.43 (0.43,0.43) | 0.03 (0.03,0.03) |

| Hubei | 2.30 (2.29,2.31) | 1.96 (1.95,1.97) | 0.36 (0.35,0.36) | 0.09 (0.08,0.09) |

| Hunan | 2.13 (2.12,2.13) | 1.69 (1.69,1.70) | 0.45 (0.45,0.45) | 0.05 (0.05,0.05) |

| Guangdong | 1.66 (1.66,1.67) | 1.31 (1.31,1.31) | 0.32 (0.32,0.32) | 0.07 (0.07,0.07) |

| Guangxi | 1.66 (1.65,1.66) | 1.48 (1.47,1.48) | 0.16 (0.16,0.16) | 0.04 (0.04,0.05) |

| Hainan | 1.80 (1.79,1.81) | 1.57 (1.56,1.58) | 0.28 (0.27,0.28) | 0.00 (0.00,0.00) |

| Chongqing | 1.87 (1.86,1.88) | 1.57 (1.56,1.57) | 0.30 (0.29,0.30) | 0.05 (0.05,0.05) |

| Sichuan | 1.87 (1.87,1.88) | 1.52 (1.51,1.52) | 0.32 (0.31,0.32) | 0.07 (0.07,0.07) |

| Guizhou | 1.86 (1.86,1.87) | 1.69 (1.68,1.69) | 0.22 (0.22,0.22) | 0.04 (0.04,0.04) |

| Yunnan | 1.75 (1.74,1.76) | 1.51 (1.50,1.52) | 0.31 (0.31,0.31) | 0.01 (0.01,0.01) |

| Tibet | 2.31 (2.30,2.32) | 1.24 (1.23,1.25) | 0.94 (0.93,0.94) | 0.18 (0.17,0.18) |

| Shaanxi | 2.64 (2.64,2.65) | 2.36 (2.35,2.37) | 0.32 (0.31,0.32) | 0.02 (0.02,0.02) |

| Gansu | 2.25 (2.24,2.26) | 1.75 (1.74,1.76) | 0.42 (0.42,0.43) | 0.10 (0.10,0.11) |

| Qinghai | 2.24 (2.22,2.26) | 2.07 (2.05,2.09) | 0.27 (0.26,0.28) | - |

| Ningxia | 2.32 (2.31,2.33) | 2.14 (2.13,2.15) | 0.35 (0.34,0.35) | - |

| Xinjiang | 2.35 (2.34,2.36) | 2.02 (2.01,2.03) | 0.38 (0.38,0.38) | - |

| Provinces | Sex |

Residence |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Rural | Urban | |

| Beijing | 2.64 (2.61,2.67) | 2.99 (2.96,3.01) | 2.83 (2.81,2.84) | 2.83 (2.81,2.85) |

| Tianjin | 3.27 (3.24,3.29) | 2.23 (2.21,2.25) | 2.43 (2.41,2.44) | 3.64 (3.61,3.67) |

| Hebei | 3.74 (3.73,3.75) | 2.91 (2.91,2.92) | 2.92 (2.91,2.93) | 4.21 (4.20,4.22) |

| Shanxi | 3.32 (3.31,3.33) | 2.42 (2.41,2.44) | 2.83 (2.82,2.84) | 2.95 (2.93,2.96) |

| Inner Mongolia | 4.25 (4.24,4.26) | 3.43 (3.42,3.44) | 4.91 (4.89,4.92) | 1.72 (1.71,1.73) |

| Liaoning | 4.56 (4.55,4.57) | 3.09 (3.08,3.10) | 3.83 (3.82,3.84) | 3.81 (3.80,3.82) |

| Jilin | 4.23 (4.21,4.24) | 3.80 (3.79,3.82) | 3.76 (3.74,3.77) | 4.22 (4.21,4.24) |

| Heilongjiang | 4.47 (4.45,4.48) | 3.66 (3.65,3.68) | 4.22 (4.21,4.24) | 3.77 (3.75,3.79) |

| Shanghai | 1.74 (1.72,1.76) | 2.40 (2.38,2.42) | 2.35 (2.33,2.37) | 1.81 (1.79,1.83) |

| Jiangsu | 2.21 (2.20,2.21) | 1.84 (1.83,1.85) | 2.05 (2.04,2.06) | 2.01 (2.00,2.01) |

| Zhejiang | 3.08 (3.07,3.09) | 1.55 (1.54,1.55) | 1.82 (1.81,1.83) | 2.84 (2.83,2.85) |

| Anhui | 3.29 (3.28,3.30) | 2.14 (2.13,2.15) | 2.95 (2.94,2.96) | 2.37 (2.36,2.38) |

| Fujian | 2.40 (2.38,2.42) | 1.77 (1.75,1.78) | 2.04 (2.02,2.06) | 2.05 (2.04,2.06) |

| Jiangxi | 2.51 (2.50,2.52) | 1.81 (1.81,1.82) | 2.23 (2.22,2.23) | 2.06 (2.05,2.07) |

| Shandong | 2.87 (2.87,2.88) | 2.44 (2.44,2.45) | 2.77 (2.76,2.77) | 2.50 (2.49,2.50) |

| Henan | 3.71 (3.71,3.72) | 2.82 (2.82,2.83) | 2.84 (2.84,2.85) | 4.01 (4.00,4.02) |

| Hubei | 2.44 (2.43,2.46) | 2.11 (2.10,2.13) | 0.08 (0.08,0.09) | 2.53 (2.52,2.54) |

| Hunan | 2.51 (2.50,2.51) | 1.73 (1.73,1.74) | 2.00 (1.99,2.01) | 2.37 (2.36,2.38) |

| Guangdong | 2.09 (2.08,2.09) | 1.26 (1.26,1.27) | 1.76 (1.75,1.77) | 1.58 (1.57,1.58) |

| Guangxi | 1.91 (1.90,1.92) | 1.41 (1.40,1.42) | 1.32 (1.32,1.33) | 2.20 (2.19,2.20) |

| Hainan | 2.58 (2.56,2.60) | 1.13 (1.12,1.14) | 1.90 (1.89,1.91) | 0.74 (0.71,0.76) |

| Chongqing | 2.26 (2.25,2.28) | 1.51 (1.50,1.52) | 2.88 (2.86,2.91) | 1.61 (1.60,1.62) |

| Sichuan | 2.01 (2.00,2.01) | 1.73 (1.72,1.74) | 1.73 (1.72,1.74) | 2.09 (2.08,2.10) |

| Guizhou | 2.08 (2.08,2.09) | 1.65 (1.65,1.66) | 1.98 (1.97,1.99) | 1.78 (1.77,1.78) |

| Yunnan | 1.74 (1.73,1.75) | 1.76 (1.75,1.78) | 2.67 (2.65,2.69) | 1.47 (1.46,1.48) |

| Tibet | 3.23 (3.21,3.25) | 1.05 (1.04,1.06) | 2.01 (1.99,2.03) | 2.45 (2.44,2.47) |

| Shaanxi | 2.75 (2.74,2.76) | 2.53 (2.52,2.55) | 2.38 (2.37,2.38) | 5.70 (5.66,5.74) |

| Gansu | 2.37 (2.36,2.39) | 2.10 (2.08,2.12) | 1.95 (1.94,1.96) | 2.99 (2.96,3.01) |

| Qinghai | 1.98 (1.96,2.01) | 2.53 (2.50,2.56) | 2.25 (2.23,2.27) | 2.20 (2.14,2.26) |

| Ningxia | 3.42 (3.40,3.44) | 1.46 (1.45,1.48) | 2.52 (2.50,2.54) | 2.10 (2.08,2.11) |

| Xinjiang | 3.06 (3.04,3.08) | 1.49 (1.48,1.50) | 3.43 (3.40,3.46) | 2.07 (2.06,2.08) |

Standardized prevalence of stroke adjusted to the 2010 China standard population, gender, age, regions, urban and rural; weighted estimates.

IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; IM, Inner Mongolia.

Figure 4.

The relative change (%) in the weighted prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults aged ≥ 40 years from 2013 to 2019 by each province (China map ID: 1122825493).

As shown in the Table 3, the three provinces with the highest prevalence of IS in 2019 were Inner Mongolia (3.62%; 95%CI: 3.61–3.63%), Jilin (3.80%; 3.79–3.81%), and Heilongjiang (3.73%; 3.72%,3.74%); while the three provinces with the lowest prevalence were Tibet (1.24%; 1.23–1.25%), Guangdong (1.31%, 1.31%-1.31%), and Guangxi (1.48%; 1.47–1.48%). The prevalence of ICH and SAH in 2019 stratified by provinces are presented in Table 3.

As shown in the Table 4, the most prevalent risk factors among stroke were hypertension (81.54%), hyperlipidemia (60.99%), and physical inactivity (40.09%). The least prevalent were atrial fibrillation (3.27%) and TIA (7.08%). Stroke survivors were older and more frequently were male, widowhood, living in urban, low income, and education. The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, obesity, physical inactivity, TIA and family history of stroke was significantly greater in stroke than in other participants.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the all the study participants stratified by stroke.

| Characteristics | All | Stroke |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Participants, n | 42,29,616 | 1,32,695 | 40,96,921 | |

| Mean age (SD), years | 59±11.28 | 66±9.46 | 59±11.25 | <0.0001 |

| Age groups | <0.0001 | |||

| 40–49 | 10,29,515 (24.34%) | 6043 (4.55%) | 10,23,472 (24.98%) | |

| 50–59 | 12,39,506 (29.31%) | 24,512 (18.47%) | 12,14,994 (29.66%) | |

| 60–69 | 11,52,690 (27.25%) | 53,077 (40.00%) | 10,99,613 (26.84%) | |

| 70-79 | 6,10,183 (14.43%) | 38,253 (28.83%) | 5,71,930 (13.96%) | |

| ≥80 | 1,97,722 (4.67%) | 10,810 (8.15%) | 1,86,912 (4.56%) | |

| Men | 18,84,205 (44.55%) | 66,232 (49.91%) | 18,17,973 (44.37%) | <0.0001 |

| Residence (urban) | 21,72,538 (51.36%) | 69,020 (52.01%) | 21,03,518 (51.34%) | <0.0001 |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 24.2±3.53 | 25.0±3.73 | 24.2±3.52 | <0.0001 |

| BMI group | <0.0001 | |||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 92,818 (2.19%) | 2965 (2.23%) | 89,853 (2.19%) | |

| 18.5–23.9 kg/m2 | 20,90,309 (49.42%) | 50,950 (38.40%) | 20,39,359 (49.78%) | |

| 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 | 15,87,089 (37.52%) | 55,179 (41.58%) | 1,53,1910 (37.39%) | |

| >=28.0 kg/m2 | 4,59,400 (10.86%) | 23,601 (17.79%) | 4,35,799 (10.64%) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.0001 | |||

| Han | 40,63,136 (96.07%) | 1,27,957 (96.43%) | 39,35,179 (96.06%) | |

| Zhuang | 24,112 (0.57%) | 337 (0.25%) | 23,775 (0.58%) | |

| Hui | 29,306 (0.69%) | 772 (0.58%) | 28,534 (0.70%) | |

| Manchu | 7142 (0.17%) | 125 (0.09%) | 7017 (0.17%) | |

| Uygur | 10,845 (0.26%) | 186 (0.14%) | 10,659 (0.26%) | |

| Education | <0.0001 | |||

| Compulsory education | 28,76,513 (77.37%) | 97,047 (81.35%) | 27,79,466 (77.24%) | |

| High School | 5,81,810 (15.65%) | 16,261 (13.63%) | 5,65,549 (15.72%) | |

| College and above | 2,59,386 (6.98%) | 5983 (5.02%) | 2,53,403 (7.04%) | |

| Annual income, CNY | <0.0001 | |||

| <5000 | 7,78,273 (27.42%) | 33,887 (35.96%) | 7,44,386 (27.12%) | |

| 5000–10,000 | 4,58,262 (16.14%) | 13,823 (14.67%) | 4,44,439 (16.20%) | |

| 10,000–20,000 | 4,62,330 (16.29%) | 13,217 (14.02%) | 4,49,113 (16.37%) | |

| >20,000 | 1,139,669 (40.15%) | 33,317 (35.35%) | 11,06,352 (40.31%) | |

| MI: own expense | 28,820 (0.73%) | 721 (0.58%) | 28,099 (0.74%) | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 35,03,445 (93.90%) | 1,07,242 (89.84%) | 33,96,203 (94.04%) | |

| Single | 27,767 (0.74%) | 764 (0.64%) | 27,003 (0.75%) | |

| Widowed | 1,69,583 (4.55%) | 10,275 (8.61%) | 1,59,308 (4.41%) | |

| Missing | 21,353 (0.57%) | 740 (0.62%) | 20,613 (0.57%) | |

| Vascular risk factors | ||||

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | |||

| Nonsmokers | 35,91,302 (84.91%) | 1,02,630 (77.34%) | 34,88,672 (85.15%) | |

| Past smokers | 38,851 (0.92%) | 5589 (4.21%) | 33,262 (0.81%) | |

| Current smokers | 5,99,463 (14.17%) | 24,476 (18.45%) | 5,74,987 (14.03%) | |

| Consumption of alcohol | 4,59,800 (14.33%) | 21,679 (16.36%) | 4,38,121 (14.25%) | <0.0001 |

| Family history of stroke | 3,85,000 (9.10%) | 41,619 (31.36%) | 3,43,381 (8.38%) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertensiona | 17,76,543 (42.00%) | 1,08,199 (81.54%) | 16,68,344 (40.72%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetesa | 7,71,547 (18.24%) | 44,231 (33.33%) | 7,27,316 (17.75%) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemiaa | 15,69,473 (37.11%) | 80,932 (60.99%) | 1,48,8541 (36.33%) | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45,191 (1.07%) | 4343 (3.27%) | 40,848 (1.00%) | <0.0001 |

| Obesityb | 4,57,125 (10.81%) | 23,481 (17.70%) | 4,33,644 (10.58%) | <0.0001 |

| Lack of exercise | 11,49,999 (27.19%) | 53,195 (40.09%) | 10,96,804 (26.77%) | <0.0001 |

| TIA | 75,654 (1.79%) | 9397 (7.08%) | 66,257 (1.62%) | <0.0001 |

†The results were presented as n (percentages) for categorical variables and as mean (Standard deviation, SD) for continuous variables.

Diagnostic criteria were a self-reported diagnosis from 2013 to 2016.

Obesity was defined as BMI≥28.0kg/m2.

BMI, Body Mass Index; CNY, Chinese Yuan Renminbi; TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack; MI, Medical insurance; SD, Standard Deviation.

Discussion

This study performed the first comprehensive assessment of the trends in prevalence of stroke in China from 2013 to 2019 stratified by sociodemographic characteristics. The findings showed large disparities in the prevalence of stroke by sex, age, residence, ethnicity, and province. During the 7-year study period, the weighted prevalence of stroke increased significantly from 2.28% to 2.58%. The three provinces of Shaanxi, Shandong, and Xinjiang had the most obvious increasing trends (all >20%). Furthermore, a nearly 2.5-fold difference in estimated prevalence of stroke was observed between northeast areas and southeast coastal areas.

The current prevalence of stroke in Chinese adults aged ≥40 years is 2.58% (≈17.5 million). Interestingly, one study showed that the adjusted prevalence of stroke in adults aged ≥40 years in Argentina was 1.97%.11 Previous data for the Chinese population indicated that the prevalence of stroke among adults aged ≥40 years was approximately twice that of adults aged ≥18 years.5 Thus, we speculate that the prevalence of stroke among Chinese adults is about 1.29%, suggesting that the prevalence of stroke in China has exceeded that in developing countries such as India (0.56%)12 and Sri Lanka (1.04%)13, but remains lower than those in developed countries such as the Benin (3.22%),14 United States (2.6%),15 and United Kingdom (1.7%).16 Meanwhile, another study showed that the prevalence of stroke in older adults aged ≥60 years in Singapore was 7.6%.17 In this study, we found that the prevalence of stroke in older Chinses adults aged ≥60 years ranged from 4.68% (2013) to 5.56% (2019), which was still lower than in Singapore. These data show that the prevalence of stroke in China has not significantly exceeded the prevalence in developed countries.

The age-standardized prevalence of stroke in Chinese adults aged ≥20 years was 0.26% in 198618 and increased to 0.79% in 2008.19 Wang et al.2 indicated that the prevalence of stroke in Chinese adults aged ≥20 years was 1.11% in 2013. We speculate that the current prevalence of adult stroke in Chinese adults aged ≥20 years has risen to 1.29%, being 4.9, 1.6, and 1.2 times higher than the prevalence in 1986, 2008, and 2013, respectively. Findings from the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study showed that the age-standardized prevalence rates for stroke had increased from 1.48% in 1990 to 1. 89% in 2016.20 The 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study found that the age-standardized prevalence rates for stroke was 2.24% in 2019,21 which might be overvalued.22 It should be noted that the prevalence and incidence of stroke have risen faster in China than in other countries.23 The main possible reason for the increased prevalence of stroke is aging of the general population.24 China faces an aging tsunami. By the end of 2016, the number of adults aged ≥60 years reached 230 million (16.0%).25 Aging increases the incidence of stroke risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension,26, 27 which further increase the burden of stroke. Furthermore, the ongoing high prevalence of risk factors like hypertension and diabetes and the inadequate management act as catalysts for the occurrence of stroke.1 In the China Hypertension Survey (2012–2015), 23.2% (≈244.5 million) of Chinese adults aged ≥18 years had hypertension, and among individuals with hypertension, 46.9% were aware of their condition, 40.7% were taking prescribed antihypertensive medications, and 15.3% had controlled hypertension.28 Another study on approximately 1.7 million community-dwelling adults aged 35–75 years from all 31 provinces in mainland China suggested that the rate of hypertension control was less than one in ten (7.2%).29 Meanwhile, the prevalence of diabetes in China rose from 10.9% in 2013 to 12.8% in 2019, but its rate of control showed no significant change (49.2% vs. 49.4%).30, 31 Secondly, these upward trends may have arisen through changes toward prolonged survival and reduced mortality among stroke patients.32 This may indicate the higher prevalence isn't necessarily a bad thing if it is that folks are living longer post-stroke. The outcomes for patients with stroke have gradually improved from 2002 to 2013 due to the improvement in the quality of stroke treatment and care,33 and improvement in outcomes is reflected a slightly decreased mortality of stroke patients from 1985 to 2013[1]. Cheng et al.34 reported that from 2004 to 2019, the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) of stroke substantially decreased, with a reduction of 39.8%. Furthermore, In the past 7 years (2013–2019), some specific programs for patients with stroke are implemented in the health care system. Stroke 1-2-0 educational programme and stroke emergency map greatly reduces prehospital rescue time.35-36 The China Stroke Center Project, led by the CSPPC (since 2011) and the Chinese Stroke Association (since 2015),1 has played a major role in standardizing stroke treatment and improving stroke prognosis.37 Those programs reduce stroke mortality, which in turn leads to the increasing prevalence of stroke.

It has been reported that a belt for high incidence of stroke exists in nine provincial regions within north and west China.38 In the present study, we confirmed that the northern and eastern regions had the highest prevalence of stroke. An 18-year prospective cohort study from 1997 to 2015 provided an extension of the current evidence on the north-to-south gradient by demonstrating that the differences varied across urban and rural China.39 The existing evidence suggests that adherence to healthy diets (Mediterranean, DASH, or plant-based “prudent”) was associated with reduced risk of stroke.40 The geographical environments, food cultures, and dietary habits differ substantially between the southern and northern regions of China.41 Unhealthy diets in the northern regions may cause chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes that can lead to the occurrence of stroke. Furthermore, PM2.5 pollution in wintertime has been worsening, especially in northern China.42 Wellenius et al.43 demonstrated that exposure to PM2.5 levels considered generally safe by the United States Environmental Protection Agency increased the risk of ischemic stroke onset within hours of exposure. There also have been a number papers conducted in China that have looked at acute stroke risk with air pollution,44, 45, 46 suggesting that atmospheric PM2. 5 is an independent risk factor for stroke risk. We further found that the difference in prevalence of stroke between urban and rural areas has been declining, and that the prevalence in urban areas surpassed that in rural areas in 2019. China's rapid urbanization growth during the past few decades has narrowed the urban-rural gap.47 Moreover, increasing trends in stroke risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes were more obvious in urban populations than in rural populations.28,30 Lastly, there are there more barriers to care or access in the north than in the south in China. The China's seventh national population census shows that the urbanization rates in the northern and southern regions of China are 63% and 65%, respectively, suggesting that these are more rural areas where resources are sparse in the Northern China.48 In addition, the economic level and medical resources of Southern China is significantly better than that of Northern China.49, 50 These would be upstream factors that would lead to different food cultures or dietary habits as suggested.

We found that the prevalence of stroke was higher in male participants than in female in China. Truelsen et al.51 reviewed the published data from EU countries, Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland and showed that stroke prevalence increased exponentially with age and were in most countries higher for men than for women. Similarly, in 2012, CDC reported state-specific stroke prevalence based on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data for 2006-2010, showing that age-adjusted stroke prevalence was also higher for men than for women.15 Furthermore, the prevalence of stroke and its risk factors were also higher among men in Sri Lanka.13 Stroke incidence and mortality were higher in rural than in urban areas in North America.52 In this study, we also found that the prevalence of stroke was higher in rural areas than in urban areas. However, Kusuima et al.53 reported that stroke prevalence was 0.0017% in rural Indonesia, 0.022% in urban Indonesia, 0.5% among urban Jakarta adults, and 0.8% overall. Another study also showed that rural parts of South Asia have a lower stroke prevalence compared with urban areas.54 Those different might represent varying degrees of urbanization in those countries.

The main strength of the present study is the assessment of trends in prevalence of stroke in China from 2013 to 2019. In addition, the prevalence was stratified by sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, age, residence, ethnicity, and province. These adjustments can be of great significance for the development of stroke prevention and control strategies across China and its provinces. Finally, enrolling at least 500,000 people each year made our research have extensive national coverage. The present study also has some limitations. First, we only included Chinese adults aged ≥40 years. Thus, our findings are not representative of all Chinese adults and it only show the status of the middle-aged and elderly people (≥40 years) in China. However, a previous study found that stroke patients aged <40 years accounted for <2% of all stroke patients.2 For the high-risk population screening and intervention project, it is considered effective to select people aged ≥40 years. In addition, the screening points with a stroke prevalence of 0 will be deleted. This exclusion will lead to biased estimates, specifically the overestimation of stroke rates due to selective sampling based on our outcome of interest. Second, the northern-south gradient in prevalence of stroke across China warrants further research. Such research could be used for the adoption of stroke prevention strategies according to local conditions. Third, the study did not use representative samples because this was not possible with such rapid large-scale recruitment. The enrollment rate varied within the study period and the provinces. These disparities may have affected the estimates for prevalence and incidence of stroke. However, we used a multi-factor weighting method to calculate the prevalence of stroke, which can effectively reduce these effects. In addition, there are huge variations in the sample size between provinces. The prevalence of stroke in some provinces with limited sample size might be overestimated. And the differences across provinces may be to some extent true, but may have been exaggerated by selection bias. Future work needs to remove these variations. Fourth, the subsequent round of the survey might include participants from the previous round and it was possible that those stroke patients may have larger motivation to participate in the study than those non-patients, which might cause potential selection bias. Fifth, minority groups in China tend to live in specific areas. The current study compared the minority groups with Han Chinese across the country, which is inappropriate. It might be more suitable to compare the minority groups with those people living in the same areas. However, at this stage, it is difficult for us to match the Han and ethnic minorities according to the place of residence. This will be a good direction for our future research. Finally, we did not obtain information on patient adherence to medications, which reduced our ability to investigate some potential reasons for suboptimal treatment. In addition, the prevalence rate can increase with increased incidence rates as well as with reduced fatality rates. However, the change in incidence rates of this study was not obtained.

Conclusion

The prevalence of stroke in China and most provinces has continued to increase in the past 7 years (2013–2019) and warrants a broad-based nationwide strategy for improved prevention as well as greater efforts in screening and more effective and affordable interventions. For provinces with high prevalence of stroke in particular, the present data will be useful for the Provincial Health Committee to develop targeted programs for stroke prevention and allocate medical resources.

Contributors

Dr WL had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the data analysis accuracy. Study concept and design: All authors; Acquisition of data: TW, YF, BH, WL; Analysis and interpretation of data: TW, YF, ML, CL; Drafting of the manuscript: TW, YF; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: BH, ML, CL, WL; Statistical analysis: YF, ML, CL; Administrative, technical, or material support: all authors; Obtained funding: WL, TW; Study supervision: WL.

Data sharing statement

Please contact the corresponding author (Pro. Wang) for the data request.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgment

We thank all the patients, hospitals, and staff involved in the project. We especially want to express our gratitude to those doctors and medical staff who participated in the clinical data collection and follow-up. We need special thanks, Mr. Niu XD and Mrs. Liu JJ (China Stroke Data Center, Beijing, China), who helped us collect data and perform statistical processing. We also thank Alison Sherwin, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Participating hospitals

The following hospitals took part in the China Stroke High-risk Population Screening and Intervention Program from Jan, 2013, to Dec, 2019:

The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Cangzhou Central Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Jingmen City, Second People's Hospital of Jiaozuo City, Anhui Provincial Hospital, Handan City First Hospital, Shuguang Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hebei Provincial People's Hospital, Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, The First People's Hospital of Huainan City, Anyang People's Hospital, Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Yibin City, Lianyungang First People's Hospital, Nanyang Nanshi Hospital, Nanjing Gulou Hospital, Luoyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Zhuzhou Central Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou Municipal Hospital, Shanxi Provincial People's Hospital, Hunan Provincial People's Hospital, Shanghai Pudong Hospital, Xiangtan Central Hospital, The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Yichun People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Huaihua City, Qingyuan People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Yunnan Province, Jiuquan People's Hospital, Hunan Provincial Brain Hospital, Mianyang Central Hospital, The Third People's Hospital of Datong City, Changde First People's Hospital, Yueyang First People's Hospital, 3201 Hospital, Shaoyang Central Hospital, Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Shengli Oilfield Central Hospital, Yongzhou Central Hospital, Xingtai People's Hospital, Chengde Central Hospital, Zhuhai People's Hospital, Changsha.

Central Hospital, Liaocheng People's Hospital, Deyang People's Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, Shenzhen Second People's Hospital, Hengshui City People's Hospital, First People's Hospital of Baiyin City, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Lishui Central Hospital, General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University, Shijiazhuang Third Hospital, Pingxiang City People's Hospital, Yingkou Central Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Nantong University Hospital, Wuhan First Hospital, Three Gorges Hospital of Chongqing University, Tongling People's Hospital, Yuncheng Central Hospital, Weihai Municipal Hospital, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Yuxi City People's Hospital, Ganzhou People's Hospital, Liuyang City Jili Hospital, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Qingdao University Hospital, Suining Central Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Zigong City, The First People's Hospital of Shangqiu City, Nanchong Central Hospital, Baise City People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanhua University, The First People's Hospital of Jining City, The First People's Hospital of Chenzhou City, Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Qianfoshan Hospital of Shandong Province, Subei People's Hospital, Fuyang People's Hospital, Ningde City Hospital Affiliated to Ningde Normal University, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Fenyang Hospital of Shanxi Province, Qinzhou Second People's Hospital, Yangmei Group General Hospital, Tianshui First People's Hospital, Linyi People's Hospital, Jiangsu Provincial People's Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Daqing Oilfield General Hospital, Yan'an University Affiliated Hospital, Leshan City People's Hospital, People's Hospital of Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, Sinopharm Tongmei General Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Science and Technology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Affiliated Hospital of Binzhou Medical University, Zhengzhou People's Hospital, Huaihe Hospital of Henan University, Beihai City People's Hospital, Henan Provincial People's Hospital, Tianjin First Central Hospital, Taihe Hospital of Shiyan City, People's Hospital of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Baoding First Hospital, The Second People's Hospital of Wuhu City, Heping Hospital Affiliated to Changzhi Medical College, Liuzhou Workers Hospital, Zhoukou Central Hospital, Shaoxing People's Hospital, Tonghua Central Hospital, Dezhou People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Yulin City, Maanshan City People's Hospital, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Zhanjiang Central People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Jiujiang City, Hangzhou First People's Hospital, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Liaocheng Second People's Hospital, Sanming First Hospital, Wenzhou Central Hospital, Yuebei People's Hospital, Gansu Provincial People's Hospital, Changzhou First People's Hospital, Xiangyang First People's Hospital, Sanya Central Hospital, Pingdingshan First People's Hospital, Chinese People's Liberation Army Army Characteristic Medical Center, Xuchang Central Hospital, Jiyuan City People's Hospital, Qiqihar First Hospital, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, Harbin Second Hospital, The First Hospital of Qinhuangdao City, Yibin Second People's Hospital, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Anqing Municipal Hospital, Benxi Central Hospital, Xiaogan Central Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical College, Guilin People's Hospital, The Third People's Hospital of Hubei Province, Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Mudanjiang Second People's Hospital, People's Hospital of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, The First People's Hospital of Jingdezhen City, The First People's Hospital of Jinzhong City, The First People's Hospital of Yancheng City, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jiamusi University, Dandong Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Weifang Medical College, Guizhou Provincial People's Hospital, Qingyang People's Hospital, Ordos Central Hospital, Tai'an Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Yanbian University, Taizhou Hospital, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Xiyuan Hospital of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Luohe Central Hospital, Wuzhou Red Cross Hospital, Inner Mongolia Forestry General Hospital, General Hospital of the Northern Theater of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, Huzhou Central Hospital, Peking University Third Hospital, Haikou People's Hospital, Hainan Provincial People's Hospital, Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital, Kunming Yan'an Hospital, Hebi City People's Hospital, The First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Nanyang Central Hospital, Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University, Baotou Central Hospital, Xinyang Central Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia University for Nationalities, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Zhongshan People's Hospital, Qinghai Provincial People's Hospital, Liaoning Provincial People's Hospital, The First People's Hospital of Qujing City, Jinzhou Central Hospital, Zhumadian Central Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Liaoyang Central Hospital, Dingzhou People's Hospital, Nanjing Brain Hospital, Shenyang First People's Hospital, Linfen Central Hospital, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Wuxi Second People's Hospital, Heilongjiang Provincial Hospital, Chifeng City Hospital, Sanmenxia Central Hospital, Longyan First Hospital, Xinyu City People's Hospital, Chongqing People's Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Dongfang Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; Chaoyang Central Hospital; Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University; Jilin Provincial People's Hospital; Jilin Central Hospital; Sanya People's Hospital; Wuwei City People's Hospital; Tangshan Workers Hospital; The Second Hospital of Tianjin Medical University; Hanzhong Central Hospital; Dalian Central Hospital; The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University; The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University; Puyang Oilfield General Hospital; Yulin Second Hospital; Fujian Provincial Hospital; Songyuan Central Hospital; Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital; People's Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region; Tianjin Huanhu Hospital; The First Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University; Yichang Central People's Hospital; Siping Central Hospital; Special Medical Center of the PLA Strategic Support Force; The First People's Hospital of Kashgar; Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University; Tianjin Medical University General Hospital; The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University; Shanghai Changhai Hospital; Beijing Tsinghua Chang Gung Memorial Hospital; Huazhong University of Science Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College; The First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University School of Medicine; People's Hospital of Tibet Autonomous Region; Second People's Hospital of Tibet Autonomous Region; General Hospital of Tibet Military Region; Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences; Beijing Luhe Hospital, Capital Medical University.

Funding statement

This study was supported by grants from the National Major Public Health Service Projects (No. Z135080000022). The funding organizations had no role in the study's design and concept; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the manuscript's preparation, review, or approval.

Ethics approval

The Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University Xuanwu Hospital approved the trial protocol according to the Declaration of Helsinki (No. 2012045). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before entering the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100550.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wu S., Wu B., Liu M., et al. Stroke in China: advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(4):394–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang W., Jiang B., Sun H., et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation. 2017;135(8):759–771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferri C.P., Schoenborn C., Kalra L., et al. Prevalence of stroke and related burden among older people living in Latin America, India and China. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1074–1082. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.234153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., An Z., Li B., et al. Increasing stroke incidence and prevalence of risk factors in a low-income Chinese population. Neurology. 2015;84(4):374–381. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan T, Ma J, Li M, et al. Rapid transitions in the epidemiology of stroke and its risk factors in China from 2002 to 2013. Neurology. 2017;89:53–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao B.H., Yan F., Hua Y., et al. Stroke prevention and control system in China: CSPPC-stroke program. Int J Stroke. 2021;16(3):265–272. doi: 10.1177/1747493020913557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qi W., Ma J., Guan T., et al. Risk factors for incident stroke and its subtypes in China: a prospective study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(21) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroke—1989 Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO task force on stroke and other cerebrovascular disorders. Stroke. 1989;20:1407–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]