Abstract

An 81-year-old man was admitted to the hospital because of decreased level of consciousness. He had bradycardia (27 beats/min). Electrocardiography showed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF and ST-segment depression in leads aVL, V1. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) visualized reduced motion of the left ventricular (LV) inferior wall and right ventricular (RV) free wall. Coronary angiography revealed occlusion of the right coronary artery. A primary percutaneous coronary intervention was successfully performed with temporary pacemaker backup. On the third day, the sinus rhythm recovered, and the temporary pacemaker was removed. On the fifth day, a sudden cardiac arrest occurred. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed. TTE showed a high-echoic effusion around the right ventricle, indicating a hematoma. The drainage was ineffective. He died on the eighth day. An autopsy showed the infarcted lesion and an intramural hematoma in the RV. However, no definite perforation of the myocardium was detected. The hematoma extended to the epicardium surface, indicative of oozing-type RV rupture induced by RV infarction. The oozing-type rupture induced by RV infarction might develop asymptomatically without influence on the vital signs of the patient. Frequent echocardiographic evaluation is essential in cases of RV infarction taking care of silent oozing-type rupture.

Learning objective

Inferior left ventricular infarction sometimes complicates right ventricular (RV) infarction. The typical manifestations of RV infarction include low blood pressure, low cardiac output, and elevated right atrium pressure. Although the frequency is low, fatal complications of oozing-type RV rupture might progress asymptomatically. Frequent echocardiographic screening is necessary to detect them.

Keywords: Right ventricular infarction, Primary percutaneous coronary intervention, Cardiac arrest, Intramural hematoma, Oozing-type right ventricular rupture, Transthoracic echocardiography

Introduction

Although the prognosis of cardiovascular disease has been significantly improving, the mortality of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is still high: out-of-hospital mortality is about half, and in-hospital mortality within 28 days is 10 % of patients with AMI [1]. Although rare (<1 % of AMI cases), the ventricular free wall rupture is the most fatal complication of these, which occurs mostly within 24 h after AMI [2]. Older age and a longer period between symptom onset and angiography have been reported as risk factors. Among them, left ventricular (LV) free wall rupture is associated with high mortality due to cardiac tamponade. The true proportion of LV free wall rupture might be higher because it might include patients dying suddenly before reaching the hospital.

Right ventricular (RV) free wall rupture is rare, with few reported cases reporting the clinical course and the type of rupture. RV infarction occurs in 30–40 % of patients with inferior LV infarction, and 13 % of patients with anterior LV infarction [3], [4]. However, there are also few cases reporting the association between RV-free wall ruptures with RV infarction. We experienced an RV-free wall oozing-type rupture recognized as sudden cardiac arrest caused by an intramural hematoma following acute inferior LV infarction complicating RV infarction.

Case report

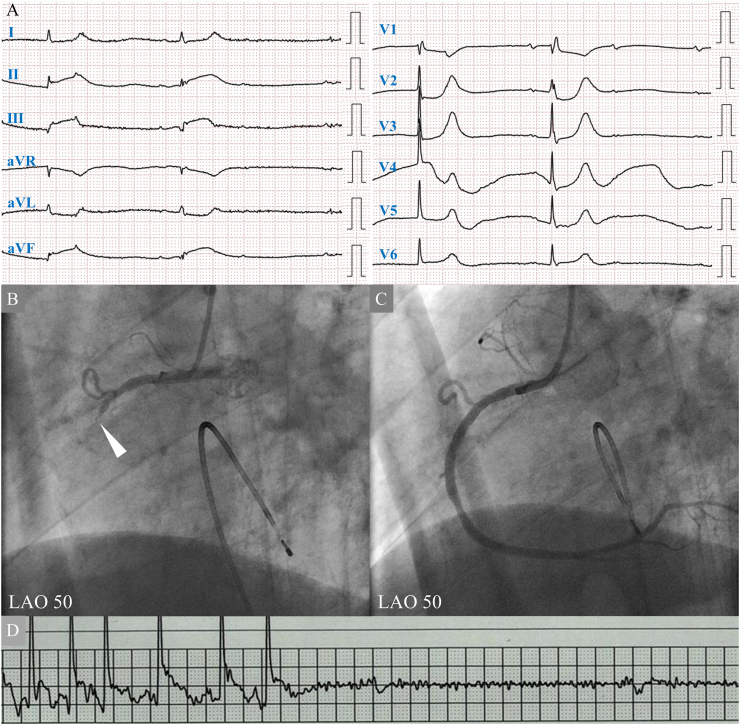

An 81-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of a decreased level of consciousness. He complained of appetite loss two days before admission and chest discomfort one day before admission. He was a current smoker (Brinkman index: 650), and had a medical history of hypertension. His blood pressure was 144/98 mm Hg. Twelve-lead electrocardiography revealed bradycardia (27 beats/min) caused by a complete atrioventricular block with a junctional escape rhythm, and an ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, with ST-segment depression in leads aVL, V1 (Fig. 1A). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated preserved LV ejection fraction (62 %). However, the wall motion of the LV basal inferior decreased and the RV-free wall contraction was reduced. Blood tests showed normal levels of creatine kinase (CK) (179 U/L), elevated creatine kinase MB (14.2 U/L), troponin I (22.5 ng/mL), aspirate transaminase (940 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase (1001 U/L). The patient was diagnosed with AMI.

Fig. 1.

(A) 12-lead electrocardiography on admission shows an atrioventricular block with a junctional escape rhythm. ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF, and ST-segment depression in lead aVL, V1 is seen. His heart rate was 29 beats/min. (B) Coronary angiography (CAG) shows complete occlusion of right coronary artery (RCA) without collateral flow (white arrowhead). (C) A drug-eluting stent is implanted in the RCA segment two. Final CAG shows reperfusion of RCA. (D) On the fifth hospital day, sudden cardiac arrest is detected by monitor electrocardiography.

LAO, left anterior oblique view.

Emergent coronary angiography was performed with backup pacing by inserting a temporary pacemaker (Fig. 1B). The right coronary artery was completely occluded, without collateral flow. The onset of the disease was estimated within 48 h, and the patient's chest discomfort had continued. Emergency primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed. The wire easily crossed the lesion. After pre-dilatation, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) classification grade 2 was obtained. The intravascular ultrasound showed a rich plaque with attenuation in the culprit site. A drug-eluting stent was implanted with distal protection. No reflow occurred immediately after stent implantation. Coronary injections of nicorandil and nitroprusside were performed. A TIMI classification grade of 3 was achieved (Fig. 1C). A myocardial blush grade was class 1. Although the RV branch was jailed by the stent and remained occluded, final coronary angiography confirmed no vascular injury or extravascular leakage.

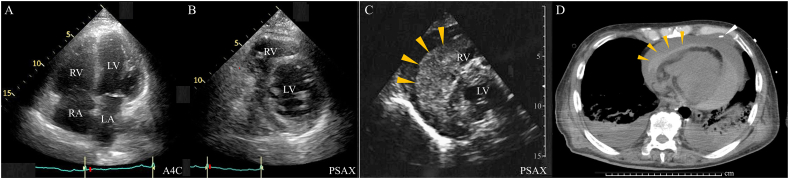

The creatine level was high (4.22 mg/dL), indicating acute renal dysfunction due to cardiogenic shock. Sufficient hydration and 24 h of continuous intravenous injection of nicorandil were performed. A sufficient urine volume was obtained. On the second hospital day, the CK level peaked at 345 U/L. The systolic blood pressure was maintained 100–120 mm Hg. On the third hospital day, the creatine level improved (1.0 mg/dL), the patient recovered to sinus rhythm, and the temporary pacemaker was removed. TTE showed slightly reduced RV-free wall contraction (tricuspid annular plane excursion: 16 mm, fractional area change: 23 %), slight enlargement of RV (RV basal diameter: 46 mm, RV mid diameter: 36 mm, RV longitudinal diameter: 76 mm), and slight enlargement of the right atrium (RA) (RA minor axis dimension: 3.1 cm/m2, RA major axis dimension: 3.4 cm/m2, RA area: 20.7 cm2, 2-dimensional echocardiographic RA volume: 45.4 mL/m2), suggestive of RV infarction (Fig. 2A). However, no pericardial effusion was observed (Fig. 2B). On the fifth hospital day, the cardiopulmonary arrest occurred (Fig. 1D). TTE revealed a high echoic effusion, suggestive of a hematoma (Fig. 2C). A pericardial puncture was unsuccessful. Intra-aortic balloon pumping and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation were performed. Chest computed tomography also revealed a hematoma (Fig. 2D). Spontaneous circulation did not resume. Thoracotomy hematoma removal might be the ultimate method to rescue the patients. However, the Glasgow coma scale score was 3, and the pupillary light reflex disappeared without sedation. We did not consider further invasive procedures. He died on the eighth hospital day.

Fig. 2.

(A, B) On the third hospital day, transthoracic echocardiographic apical four-chamber view (A4C) just after sinus conversion shows an enlargement of the right ventricle (RV) and right atrium (RA), suggestive of RV infarction. The parasternal short-axis view (PSAX) shows no pericardial effusion. LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium. (C) On the fifth hospital day, transthoracic echocardiographic PSAX reveals high echoic effusion in the pericardial side, indicating a hematoma (orange arrowheads). (D) Computed tomography revealed a high-density lesion around the pericardium on the fifth hospital day, indicating a pericardial hematoma (orange arrowheads). The white arrowhead shows a pericardial drainage catheter, which is ineffective because of pericardial hematoma.

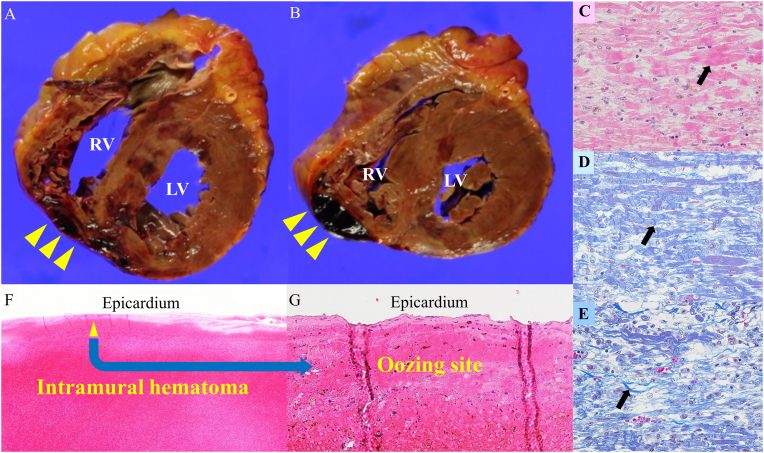

An autopsy was performed. RV rupture due to myocardial infarction or perforation of a temporary pacemaker was the differential diagnosis. Macroscopic findings of the autopsy showed a hematoma in the pericardial cavity. The total volume of pericardial fluid, including hematoma, was 200 mL. The short-axis cross-section of the heart showed an infarct lesion from the RV-free wall via infero-septum to the LV inferior wall, suggestive of RV infarction complicating LV inferior infarction. Moreover, intramural hematoma extending to the epicardium around the posterior side of the RV-free wall was demonstrated (Fig. 3A, B). However, no obvious perforation was detected on the epicardial surface. Microscopic findings showed no evidence of subacute stent thrombosis. Reperfusion of a small RV branch was detected, which might have less impact on RV infarction. A histological examination revealed a hemorrhagic infarction and intramural hematoma. The mixed lesions of coagulative necrosis, contraction band necrosis, and collagen fiber were detected around the intramural hematoma, indicative of hemorrhagic infarction more than a few days after myocardial infarction (Fig. 3C, D, F). The hematoma extended to the epicardium surface, which might be a site indicative of oozing-type rupture as a clinical diagnosis (Fig. 3F, G).

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Macroscopical findings of the autopsy show intramural hematoma extension to the epicardium around the posterior side of the RV free wall (yellow arrowheads). However, no obvious perforation was detected on the epicardial surface. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin staining demonstrates coagulative necrosis (black arrow), indicative of the early stage myocardial infarction within 12 h. (D) Masson staining demonstrates contraction band necrosis (black arrow), indicative of the early stage myocardial infarction within 24 h. (E) Masson staining demonstrates infiltration of inflammatory cells, fibroblast, and collagen fibers (black arrow), indicative of more than a few days after myocardial infarction. The mixed lesions of Fig. C, D, and E are detected around the intramural hematoma, indicative of hemorrhagic infarction more than a few days after myocardial infarction. (F, G) Hematoxylin-eosin staining demonstrates intramural hematoma, which extends to the epicardium surface, where might be an oozing site (yellow arrowheads), indicative of an oozing-type rupture as a clinical diagnosis.

Discussion

AMI requires early reperfusion within 12 h of onset. Primary PCI is the principal strategy for salvaging the infarcted myocardium. If >12 h have passed since the onset of the symptoms, primary PCI is considered for patients with persistent symptoms complicating cardiogenic shock, including elderly patients [5]. The indication for primary PCI was extended for patients without symptoms within 48 h from the onset, which was reported to reduce the infarct size [6]. In this case, the onset of symptoms was within 48 h, and the patient's vital signs were unstable due to bradycardia induced by an atrioventricular block. The emergent PCI was performed. The mechanical complications of AMI were relatively high. Frequent echocardiographic evaluation is recommended to promptly detect them. The primary PCI was successful with the achievement of the TIMI classification grade of 3. However, TTE demonstrated the possibility of RV infarction. The recovery of sinus rhythm paradoxically might trigger the onset of an intramural hematoma of the RV-free wall and subsequent rupture of the RV-free wall. Clinically, there are two distinct types of rupture: blowout-type rupture and oozing-type rupture. Most free wall blowout-type ruptures occur in the LV because high pressure is applied to the damaged lesion with myocardial necrosis [7]. On the other hand, the mechanisms of oozing-type rupture are unclear, and there have been a few reports on the treatment of oozing-type ruptures [8]. The RV is a low-pressure system, and volume overload due to intravenous infusion for the treatment of AMI might stress the free wall of the RV, inducing oozing-type rupture of the RV [9]. Based on the clinical course of this case, there were symptoms of RV infarction. The histological finding demonstrated the RV infarction. Acute LV inferior infarction frequently complicates RV infarction [3], [4]. And RV dysfunction is found in a higher proportion (40 %) of patients with inferior LV infarction [10]. The clinical problem of RV infarction is the predominant RV dysfunction characterized by decreased RV pressure, the symptoms of low output, and elevated right atrium pressure. Most cases of RV infarction or RV dysfunction have no symptoms, and the clinical course is good due to maintaining cardiac output by enough volume loading and catecholamine support. However, the balance between LV and RV contractility, the infarcted size and location, and atrium function might induce fatal complications like this case. Swan Ganz-catheter is indispensable to monitor RV infarction, especially in the acute phase. However, the patient developed intensive care unit delirium. Insertion of Swan Ganz-catheter was not performed. The recovery of RV synchronous contraction due to sinus conversion might elevate the intra-RV pressure and stress the infarcted lesion of RV, inducing intramural hemorrhage. Histological findings suggested that the RV-free wall intramural hematoma was triggered by hemorrhagic infarction, extended to the epicardial surface, and might ooze through the epicardium to the pericardium cavity without symptoms, resulting in sudden cardiac arrest. Frequent TTE monitoring is essential in case of LV inferior infarction taking care of oozing-type rupture induced by RV infarction.

Declaration of competing interest

Yukie Sano, Toshimitsu Kato, Noriaki Takama, Etsuko Hisanaga, Naohiro Matsumoto, Shiro Amanai, Youhei Ishibashi, Kazuhumi Aihara, Takashi Nagasaka, Norimichi Koitabashi, Yoshiaki Kaneko, Hideaki Yokoo, and Hideki Ishii declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Steg P.G., Goldberg R.J., Gore J.M., Fox K.A., Eagle K.A., Flather M.D., Sadiq I., Kasper R., Rushton-Mellor S.K., Anderson F.A., Investigators G.R.A.C.E. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker R.C., Gore J.M., Lambrew C., Weaver W.D., Rubison R.M., French W.J., Tiefenbrunn A.J., Bowlby L.J., Rogers W.J. A composite view of cardiac rupture in the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setaro J.F., Cabin H.S. Right ventricular infarction. Cardiol Clin. 1992;10:69–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabin H.S., Clubb K.S., Wackers F.J., Zaret B.L. Right ventricular myocardial infarction with anterior wall left ventricular infarction: an autopsy study. Am Heart J. 1987;113:16–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzavik V., Sleeper L.A., Cocke T.P., Moscucci M., Saucedo J., Hosat S., Jiang X., Slater J., Lejemtel T., Hochman J.S., SHOCK Investigators Early revascularization is associated with improved survival in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:828–837. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00844-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schömig A., Mehilli J., Antoniucci D., Ndrepepa G., Markwardt C., Di Pede F., Nekolla S.G., Schlotterbeck K., Schühlen H., Pache J., Seyfarth M., Matrinoff S., Benzer W., Schmitt C., Dirschinger J., et al. Mechanical reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting more than 12 hours from symptom onset: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2865–2872. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skurnick J., Lavenhar M., Natarajan G.A. Cardiac rupture in acute myocardial infarction: a reassessment. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23:78–82. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200203000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akcay M., Senkaya E.B., Bilge M., Yeter E., Misra M.C., Kurt M., Davutoglu V. Rare mechanical complication of myocardial infarction: isolated right ventricle free wall rupture. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:e7–e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagi D., Shirai K., Arimura T., Saito N., Mitsutake C., Mitsutake R., Hida S., Iwata A., Nishikawa H., Kawamura A., Miura S., Saku K. Left ventricular oozing rupture following acute myocardial infarction. Intern Med. 2008;47:1803–1805. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah P.K., Maddahi J., Berman D.S., Pichler M., Swan H.J. Scintigraphically detected predominant right ventricular dysfunction in acute myocardial infarction: clinical and hemodynamic correlates and implications for therapy and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]