Abstract

Hummingbirds have evolved to hover and manoeuvre with exceptional flight control. This is enabled by their musculoskeletal system that successfully exploits the agile motion of flapping wings. Here, we synthesize existing empirical and modelling data to generate novel hypotheses for principles of hummingbird wing actuation. These may help guide future experimental work and provide insights into the evolution and robotic emulation of hummingbird flight. We develop a functional model of the hummingbird musculoskeletal system, which predicts instantaneous, three-dimensional torque produced by primary (pectoralis and supracoracoideus) and combined secondary muscles. The model also predicts primary muscle contractile behaviour, including stress, strain, elasticity and work. Results suggest that the primary muscles (i.e. the flight ‘engine’) function as diverse effectors, as they do not simply power the stroke, but also actively deviate and pitch the wing with comparable actuation torque. The results also suggest that the secondary muscles produce controlled-tightening effects by acting against primary muscles in deviation and pitching. The diverse effects of the pectoralis are associated with the evolution of a comparatively enormous bicipital crest on the humerus.

Keywords: hummingbird, musculoskeletal system, muscle contractile behaviour, flapping flight, bioinspired robotics

1. Introduction

Hummingbirds use their flapping wings to control aerodynamic forces and moments to an extent unmatched by many other biological [1–3] and robotic fliers [4]. Such high authority of flight control is enabled by their wing musculoskeletal system [5]. The hummingbird wing skeleton has anatomical components and degrees of freedom similar to those of other flying birds [6,7]. However, they have evolved a proportionally shortened humerus [8] and use its long-axis rotation to enhance wing stroke [5]. They also have a pattern of wing movement and a transmission ratio from primary power muscles to wing movements similar to insects [5,9]. Despite these understandings on the anatomical and physiological features, the small size of hummingbirds prevents most existing methods for in vivo measurement of muscle contractile behaviour. Thus, although the charismatic flight capacity of hummingbirds has attracted much research, there still lacks a comprehensive understanding of the functioning and the key actuation principles of the hummingbird wing musculoskeletal system.

For engineers, while it is enticing to emulate hummingbirds for the design of novel micro aerial vehicles with high manoeuvrability and stability, the lack of understanding in hummingbird wing actuation renders such bio-mimicry elusive and unfruitful. Existing hummingbird-inspired or hummingbird-sized flapping-wing robot designs [4,10–16] replicate only a few hypothetical hummingbird flight features, such as stroking using single-axis wing actuation, high elastic energy storage to reduce energy expenditure on wing stroke acceleration and deceleration, and passive wing pitching. In addition, existing designs do not consider performance other than hovering, yet other flight modes undoubtedly have also shaped the evolution of hummingbird wings. Therefore, it is unlikely that these engineering designs have captured the key morphological traits that are needed to emulate the complete capacity of hummingbird flight including agile manoeuvres that do not conform to helicopter models [3].

Here, we aim at advancing the understanding of hummingbird musculoskeletal wing-actuation system using a novel functional modelling approach by integrating existing empirical and modelling data. The derived functional model predicts key design traits of the musculoskeletal system of the hummingbird wing: (i) detailed contractile behaviour and properties of the two primary muscles (pectoralis and supracoracoideus), including active versus passive, agonist versus antagonist force generations, stress, strain, muscle–tendon elastic energy storage, work loops and power, and (ii) spatio-temporal torque characteristics of the primary and secondary muscles in generating 3-DoF wing motion. Together, these results generate the following hypotheses regarding the principles of wing actuation in hummingbirds: (i) The primary muscles do not simply flap the wing about a single stroke axis, but also actively deviate and pitch the wings (figure 1b for definitions of stroke, deviation and pitching angles), while producing comparable actuation torque magnitude about stroke, deviation and pitching. The capacity of the pectoralis to effect these functions depends in part on a proportionally enormous bicipital crest on humerus (electronic supplementary material, figure S2b), an evolutionarily derived trait of hummingbirds, (ii) the secondary muscles are co-activated with, and act against the primary muscles with an active tightening effect in wing deviation and pitching and (iii) the percentage elastic energy storage in hummingbird muscles is intermediate to that of other birds such as pigeons [18], budgerigars [19], cockatiels [20] and zebra finches [21], and flying insects such as beetles [22], hawkmoths [23], locusts [24] and bumblebees [25]. These novel hypotheses of hummingbird wing actuation may help engineers rethink and reshape the design template for agile robotic flight. They also may guide future empirical work testing the comparative biomechanics of the hummingbird wing.

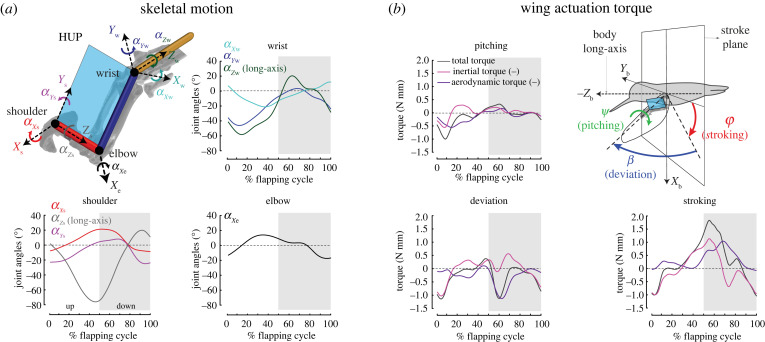

Figure 1.

Hummingbird wing skeletal motion and wing actuation torque. (a) Wing skeletal kinematics. Hummingbird wing skeleton can be functionally described as three links, which are humerus (red), radius and ulna (blue), and carpus, metacarpus and digits (yellow). Humerus–ulna plane (HUP) is defined as the plane spanned by humerus and ulna (or radius). The shoulder and wrist act as 3-DoF ball-and-socket joints and the elbow acts as a 1-DoF hinge joint. The graphs show the instantaneous joint angles (α) according to the coordinate frames defined at 3-DoF shoulder (Xs, Ys, Zs), 3-DoF wrist (Xw, Yw, Zw) and 1-DoF elbow (Xe) (see electronic supplementary material, section S1.1). Grey shaded and unshaded areas represent downstroke and upstroke, respectively. (b) Body-fixed coordinate system (Xb, Yb, Zb), wing stroke, deviation and pitching angles and wing actuation torque. Stroking (φ) is defined as dorsoventral movement of HUP, deviation (β) as head–tail movement of HUP and pitching (ψ) as rotation of HUP about the long-axis connecting shoulder and wrist joints, where the movement of HUP is defined relative to the bird's body. The graphs show the corresponding wing actuation torque (TCFD,actuation) at the shoulder for generating wing stroke, deviation and pitching. The aerodynamic and inertial torques shown are negative (denoted by (–) notation) of the aerodynamic torque and inertia experienced by the wing. TCFD,actuation was estimated based on the CFD data [17] (see electronic supplementary material, section S3). (Online version in colour.)

2. Functional modelling of hummingbird wing musculoskeletal system

The functional model of hummingbird wing musculoskeletal system (referred to below as musculoskeletal wing-actuation model) predicts the total actuation torque Tθ,actuation(t) transferred from a bird's body to the wing via the shoulder joint at a given instant of time t. This model represents a nonlinear mapping from the instantaneous wing skeletal kinematics u(t) to Tθ,actuation(t), defined according to a collection of parameters θ modelling the anatomical and physiological properties of the musculoskeletal system.

The following provides the details of the modelling process. To formulate the mapping and its model parameters, we first synthesized empirical data from multiple sources on hummingbird skeletal and muscular anatomy and kinematics. For dimensions and orientation of the wing skeleton, we used the X-ray marker data and the μCT scan of a hovering ruby-throated hummingbird [5]. For muscle anatomy and function, we synthesized anatomical data from two previous studies on hummingbirds [6,7], as well as data from other birds where data for hummingbirds were not available (see electronic supplementary material, section S1.2). We also conducted dissection on a calliope hummingbird (Stellula calliope) to find the attachment region and orientation for the pectoralis (PECT), supracoracoideus (SUPRA) and scapulohumeralis caudalis (SHCA) (see electronic supplementary material, section S1.3).

The wing skeleton has effectively three rigid links connected in series (figure 1a), which are actuated by at least 40 muscles [6], giving rise to a 7-DoF skeletal system. However, we found that the torque transfer from the bird's body to the wing is enabled by only approximately 14 muscles that connect the body skeleton and the first two links of the system (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), i.e. humerus and radius/ulna (which define the humerus–ulna plane (HUP, figure 1a)). Our hypothesized wing-actuation model modelled the effects of these approximately 14 muscles using three antagonistic muscle groups (figure 2a) and provided actuation to HUP about the shoulder joint. These included a primary muscle group (PMG) consisting of the two primary muscles (figure 2a(i)) pectoralis and supracoracoideus (referred to as PECT and SUPRA in the wing-actuation model) that insert on the humerus, and two combined secondary muscle groups, including deviation muscle group (DMG) and pitching muscle group (PiMG) (figure 2a(ii)–(iv)), which modelled the effects of secondary muscles that insert on both the humerus and radius/ulna. The DMG and PiMG each consisted of two muscle models (figure 2a(ii)–(iv)), where each model represents the combined effects of all secondary muscles along a hypothesized actuation axis in one of the half-strokes. Secondly, the two muscle models in each of DMG and PiMG could have acted antagonistically or agonistically, which was found via optimization, as it was not known beforehand whether they produce torque in identical (agonistic) or opposite (antagonistic) directions. The generation of muscle force or torque of an individual muscle was modelled using a generic three-component muscle model (figure 2a(v)), which included an active force or torque component (modelled mathematically using a central pattern generator model), a linear or nonlinear parallel elastic component, and a linear series elastic component that represents the muscle tendon (see electronic supplementary material, section S2.1). The muscle length and force (or torque) directions were estimated at each instant of the flapping cycle based on the synthesized skeletal kinematics and anatomical data (see electronic supplementary material, sections S2.2 and S2.3).

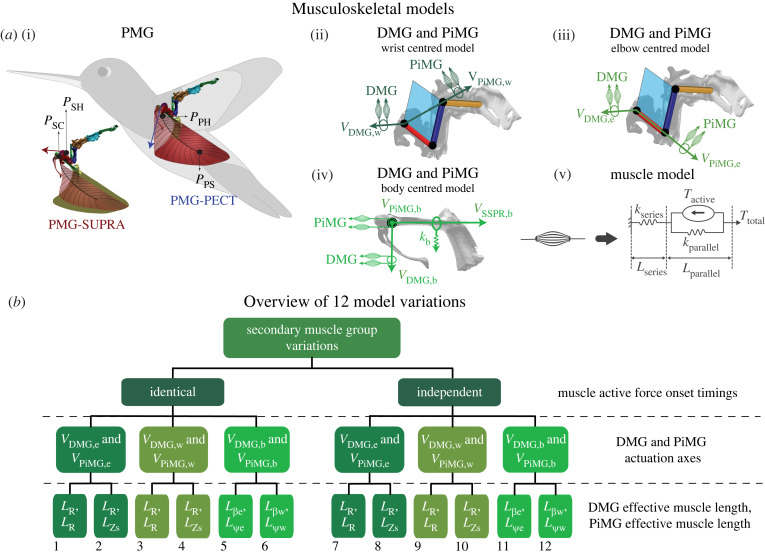

Figure 2.

Hypothesized hummingbird wing-actuation model and its variations. (a) Primary and secondary muscle groups defined in the hypothesized wing-actuation model. Each muscle group is modelled as a set of two muscle models that generate wing-actuation force (or torque) in each half-stroke. (a(i)) primary muscle group (PMG), including pectoralis: PMG-PECT and supracoracoideus: PMG-SUPRA. The muscles were assumed to lie effectively along their respective aponeurosis arcs originating on humerus (at PPH and PSH for PECT and SUPRA, respectively) and inserting on sternum for PECT (PPS) and effectively on coracoid for SUPRA (PSC). The forces were assumed to act tangent (shown using straight coloured arrows) to aponeurosis arcs at the humerus insertion points. (a(ii)–(iv)) Hypothesized actuation axes for deviation muscle group (DMG) and pitching muscle group (PiMG) for (a(ii)) wrist-centred model variations (VDMG,w: perpendicular to HUP, and VPiMG,w: along the straight-line connecting shoulder and wrist), (a(iii)) elbow-centred model variations (VDMG,e: perpendicular to HUP, and VPiMG,e: along humerus long-axis) and (a(iv)) body-centred model variations (VDMG,b: which lies along Xb, and VPiMG,b: which lies along Yb). kb represents elasticity (along VSSPR,b, which lies along Zb, see electronic supplementary material, section S2.3.1). (a(v)) Each muscle in the PMG, DMG and PiMG was modelled using a generic three-component muscle model (see electronic supplementary material, section S2). (b) Summary of the 12 model variations with three layers of assumptions shown on the right, which represent: (I) Muscle active force onset timings: the onset timing is identical when the active forces due to PMG, DMG and PiMG muscles are constrained to begin concurrently, otherwise independent, (II) DMG and PiMG actuation axes: shown in (a(ii)–(iv)) and (III) DMG and PiMG effective muscle lengths: six different length estimates (definitions in electronic supplementary material, table S2) were used to approximate DMG and PiMG muscle lengths for different model variations. Model numbers are shown at the bottom. (Online version in colour.)

We further hypothesized a total of 12 variations of the wing-actuation model with identical insertion points of primary muscles, but different assumptions on muscle length, torque directions and active force onset timings of secondary muscle groups (figure 2b), to cover all conceivable possibilities of the wing musculoskeletal system functioning.

In summary, the wing actuation torque Tθ,actuation(t) can be represented as

| 2.1 |

where Tθ,i(t) and ui(t) are the estimated actuation torque and input skeletal kinematics of individual muscle groups at time t, and i represents one of the muscle groups (among PMG, DMG or PiMG, figure 2), respectively. Skeletal kinematics uPMG(t) included PECT and SUPRA insertion points PPH, PPS, PSH and PSC (figure 2a(i)), and uDMG(t) and uPiMG(t) included their respective assumed muscle length estimates (figure 2b) and the unit vectors VDMG,j and VPiMG,j that represent torque actuation directions, at time instant t, where j represents w (wrist), e (elbow) or b (body) (figure 2b). θ represents the unknown model parameters, which included spring stiffnesses, active force and torque amplitudes, rotation slopes and intercepts, muscle active force onset times and muscle active periods (see electronic supplementary material, section S4).

The unknown model parameters θ of each model variation were optimized using genetic algorithm (GA) such that the sum of active and passive torque components due to all the muscle models in all muscle groups (i.e. Tθ,actuation) matches wing actuation torque (TCFD,actuation, figure 1b) derived from the computation fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation [17]. TCFD,actuation was estimated based on sum of the wing aerodynamic torques and inertial torques following an inverse dynamics approach. The optimized wing-actuation model, therefore, predicts the active and passive force (or torque) components of muscle models in all the muscle groups. An overview of the model definition and optimization process is shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S3.

3. Model results

All 12 wing-actuation model variations yielded good prediction of the wing actuation torque (prediction error: stroke 7.3–10.4%, deviation 7.5–14.0% and pitching 6.6–21.0%, see electronic supplementary material, section S4.2), and all model variations resulted in similar contractile behaviours of PECT and SUPRA in terms of kinematics, force, cumulative work and power (figure 3), work loops (figure 4) and torque (figure 5; see electronic supplementary material, section S4.4 for assessment of uniqueness of optimization results within and between different model variations). Model-dependent variations in the predicted muscle torque and power profiles mainly occurred in the two combined secondary muscle groups (DMG and PiMG). Note that the 12 model variations were developed based on the known muscle anatomy and were used to cover the plausible musculoskeletal actuation configurations; therefore, it is expected that the regions spanned by results of the 12 model variations provide a good indication of the plausible profiles. Nonetheless, all the major results and conclusions below are independent of the model variations, while those subject to model dependency are specifically noted. Also note that every muscle group of the defined wing-actuation model is essential since the optimization of any model variation with any muscle group removed would increase the prediction error significantly. The complete estimated model parameters are provided in electronic supplementary material, figure S5; the complete results for predicted muscle functioning variables for all 12 model variations are reported in electronic supplementary material, table S3, for which median and range values calculated over the results for 12 model variations are reported below. Note that PECT and SUPRA refers to the muscles defined in the wing-actuation model, whereas pectoralis and supracoracoideus refers to the actual bird muscles.

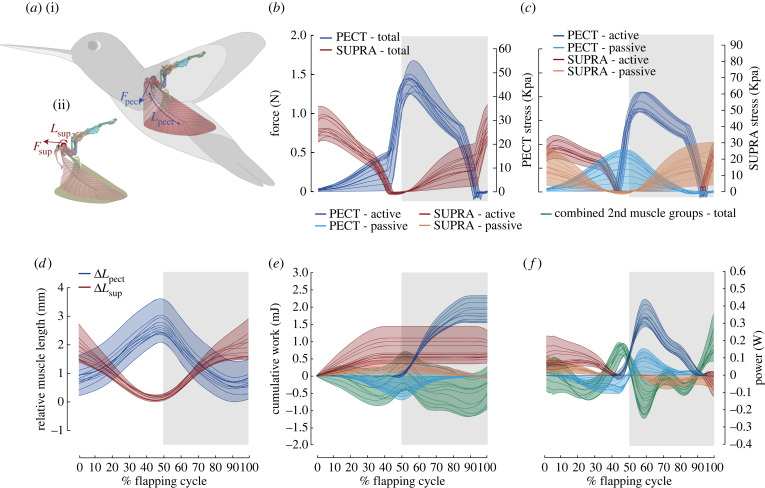

Figure 3.

Muscle contractile behaviours, including length change, force, stress, cumulative work and power for PECT and SUPRA, and cumulative work and power for secondary muscles. (a) Illustrations of (i) PECT length Lpect and force Fpect and (ii) SUPRA length Lsup and force Fsup. Note that the force due to each muscle acts tangent to their point of insertion on humerus. (b) Total force and muscle stress calculated using the estimated muscle cross-sectional area. (c) Active and passive (elastic) force contributions from PECT and SUPRA. The force and stress scale bars are applicable to both (b) and (c). (d) Relative change of PECT and SUPRA length (ΔLpect and ΔLsup), where zero represents the mean equilibrium length. (e) Cumulative work and (f) instantaneous power by active and passive (both series and parallel springs) components of PECT and SUPRA, and combined secondary muscle groups over the flapping cycle. Cumulative work is set to zero at the start of the upstroke. For (b)–(f), coloured shaded areas represent the regions spanned by the results for all model variations and grey shaded and unshaded areas represent downstroke and upstroke, respectively. (Online version in colour.)

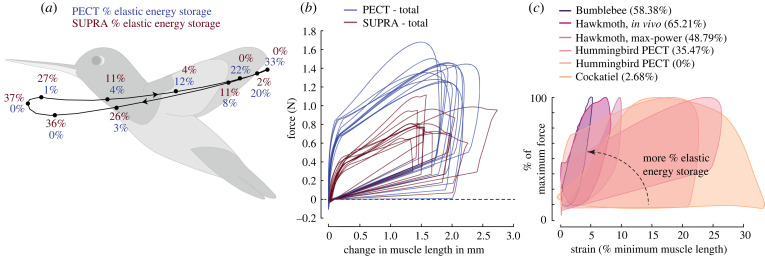

Figure 4.

Muscle–tendon elastic energy storage and work loops for a wing flapping cycle. (a) Percent elastic energy storage in PECT (blue) and SUPRA (red) for wrist-centred model variations (median obtained for the four wrist-centred model variations, estimated at each time instant) at different instants of flapping cycle (dots on the black trace). (b) Work loops of PECT and SUPRA, predicted by all 12 model variations. The minimum muscle length during the flapping cycle is set to zero (i.e. only change of muscle length is shown). (c) Work loops of PECT from two model variations with the most and the least amount of percentage elastic energy storage plotted together with those of cockatiel [20], bumblebee [25] and hawkmoth (max-power and in vivo) [23]. The percentage value for species other than hummingbirds represents percent negative work (with respect to the total muscle work), a majority of which is hypothesized to represent elastic energy storage. The work loops are scaled on the vertical axis according to the percentage of maximum force and on the horizontal axis according to the strain with respect to minimum muscle length. The slope of work loops during muscle lengthening represents muscle stiffness. Note that the reproduced work loops from other species were produced using different methods. The cockatiel work loop was produced using force and strain measurements from implanted sensors while the bird was flying freely [20], the hawkmoth work loops were produced by reproducing in vivo conditions on tethered thorax and muscles, and under conditions that maximized power output [23], and the bumblebee work loop was produced for an isolated muscle fibre when it produced highest work [25]. (Online version in colour.)

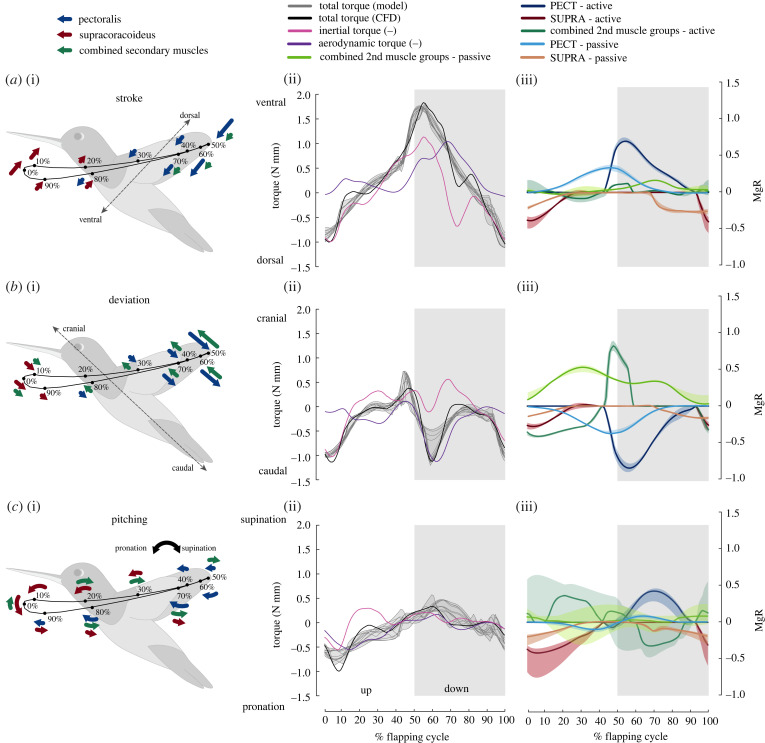

Figure 5.

Instantaneous wing actuation torque. (i) Illustrations of actuation torques due to PECT (blue), SUPRA (red) and combined secondary muscles (green) for stroke (a), deviation (b) and pitching (c) axes as defined based on HUP (figure 1a). (ii) Total wing actuation torque about the shoulder, predicted by our 12 model variations (solid grey) and from CFD study [17] (solid black). Also shown are the (negative) wing inertial torque and (negative) aerodynamic torque. (iii) Active and passive torque components from PECT, SUPRA and combined secondary muscle groups, based on the wrist-centred model variations. Two torque scales are used: N-mm and the product of the body weight (Mg) and wing length (R). The solid curves in (iii) show the median torque components (median torque at each time instant estimated using the torque results for the four wrist-centred model variations) and the associated coloured shaded areas represent the region spanned by torques for the four wrist-centred model variations. The grey shaded and unshaded areas represent downstroke and upstroke, respectively. The results for elbow-centered and body-centred model variations can be found in electronic supplementary material, figure S7. (Online version in colour.)

(a) . Predicted contractile behaviour of the primary muscles (PECT and SUPRA)

(i) . Muscle forces

The PECT of a single wing produced cycle-averaged and peak forces of 0.54 N (median, range 0.45–0.68 N) and 1.44 N (median, range 1.25–1.68 N) (or 14–20 and 37–50 times the body weight, figure 3b), respectively. The SUPRA produced cycle-averaged and peak forces of 0.34 N (median, range 0.26–0.50 N) and 0.81 N (median, range 0.65–1.11 N) (or 8–15 and 20–33 times the body weight, figure 3b), respectively. The ratio of PECT and SUPRA cycle-averaged and peak force was 1.57 (median, range 1.07–1.91) and 1.76 (median, range 1.29–2.07), respectively. These ratios are close to the ratio of the actual muscle cross-sectional areas [26] (0.30 cm2 for pectoralis and 0.21 cm2 for supracoracoideus, see electronic supplementary material, section S5). Both PECT and SUPRA began to produce active forces when they were still lengthening, i.e. at 8% (median, range 5.4–9.3%) of the flapping cycle period prior to the start of downstroke and upstroke (figure 3b), in agreement with the previous findings showing that PECT and SUPRA EMG onset occurs prior to the beginning of their respective half-strokes [27] and that force and activation are nearly concurrent [28]. The contribution of elastic forces had relatively higher model dependency compared with active forces (figure 3c). The ratio of the peak passive to peak active muscle force was 37% (median, range 0–51%) for PECT and 60% (median, range 12–113%) for SUPRA. This suggests that supracoracoideus likely uses higher amount of elastic energy storage than the pectoralis.

(ii) . Muscle stress

The estimated peak muscle stress (see electronic supplementary material, section S5) for PECT is 47 KPa (median, range 41–55 KPa) and for SUPRA is 39 KPa (median, range 31–53 KPa). The peak PECT stress obtained here is close to the pigeon peak pectoralis stress (50–58 KPa, estimated during different flight conditions) and the peak SUPRA stress is lower than the pigeon peak supracoracoideus stress (85–125 KPa, estimated during different flight conditions) [18].

(iii) . Change of muscle effective length and strain

The effective muscle lengths (including both parallel and series springs) of PECT and SUPRA were calculated as the lengths of the curved arcs (figure 3a) (see electronic supplementary material, section S2.2.2). We assumed that the muscles were relaxed at the end of their respective half-strokes (i.e. zero passive force) and were maximally stretched at the start of their respective half-strokes. The series spring length changes were small (less than 17%) compared to the overall muscle length changes. The estimated PECT length change (figure 3d) resulted in muscle strain ranging from 18% to 24% with respect to the estimated mean PECT length. These strain values are higher than those measured for pectoralis in rufous hummingbird (11%) [27], comparable to those obtained in vivo in zebra finch (17–24%) [29], but significantly lower than those reported in other birds (29–44% during take-off, ascending, descending and level flight for cockatiel [20], mallard [30] and pigeons [31,32]). Note that the estimated PECT strain values are with respect to the assumed insertion point on sternum (PPS, figure 2a(i)), however, the actual muscle fascicle strains may vary based on their origins and fascicle lengths, similar to other birds such as the pigeon [31]. The estimated SUPRA length changes appear comparable or slightly lower than those of PECT (figure 3d); however, we could not estimate the SUPRA strain as its effective origin on the sternum could not be estimated.

(iv) . Mechanical work and work loops

The estimated cumulative work done over a complete flapping cycle was 1.78 mJ (median, range 1.55–2.33 mJ) by PECT and 0.58 mJ (median, range 0.35–1.27 mJ) by SUPRA (figure 3e). Active, non-elastic force components produced positive power consistently over the flapping cycle (with only minor instantaneous power absorption) (figure 3f), resulting in positive net work output. On the other hand, passive, elastic forces stored and released energy and produced zero net work. Specifically, the PECT elastic component stored energy (negative power) at the later part of upstroke and released it at the beginning of downstroke (figures 3f and 4a), as speculated previously for ruby-throated [33], rufous [34] and broad-tailed [34] hummingbirds. Similarly, the SUPRA elastic component stored energy in the later part of the downstroke and released it at the beginning of the upstroke. Notably, elastic energy storage plays a crucial role in improving muscle–tendon efficiency, as previously reported in hummingbirds [33,34] and insects [35,36]. The maximal muscle–tendon elastic energy stored, as percentage of total cumulative work, was 26.43% (median, range 0–35.47%) for PECT and 43.66% (median, range 7.46–75.96%) for SUPRA. We also estimated the percentage negative work (relative to total cumulative work) for other birds and insects based on their work loops (figure 4c). A majority of this represents elastic energy storage, since the active forces are absent during the majority of lengthening except during near the end of the lengthening period [20,23]. The estimated median values of percentage elastic energy storage for hummingbirds are considerably higher than those in pigeons (pectoralis: 18%, supracoracoideus: 14%) [18] but comparable or lower than many insects (e.g. locusts [37]: 50%, bumblebees [38]: 30%). A similar trend can be observed when these median values are compared with the percentage negative work in cockatiel pectoralis (2.68%) and hawkmoth (49–65%).

Moreover, our results underscore the non-negligible work contribution from supracoracoideus in contrast to other birds [39], due to the more active upstroke in hummingbirds. Secondly, the work loops for different species (figure 4c) show that while the peak force is produced near the middle of the muscle shortening phase in other birds [18–21] and near the end of the muscle lengthening phase in insects [22–25], the hummingbird wing-actuation model PECT, instead, started to produce force towards the end of the muscle lengthening phase with a short active lenthening, followed by the force peak in the beginning of muscle shortening phase. Together, these results further support the hypothesis that hummingbirds have been evolutionarily converging towards insects, as their primary muscles use proportionally more elastic energy storage than those of other birds [40].

The estimated work done by combined secondary muscle groups showed more significant model-dependent variations, from absorbing large negative work (−0.97 mJ) to producing small positive work (0.27 mJ), although all model variations agreed that the secondary muscles together produce substantially less net positive work than each of PECT and SUPRA (figure 3e). This is consistent with the small size of the actual secondary muscles, rendering them incapable of providing large positive work, despite producing large torque (see below).

(b) . Predicted instantaneous force vectoring

In all hypothesized wing-actuation model variations, both PECT and SUPRA force directions were allowed to rotate linearly (with respect to the instantaneous straight-line connecting muscle insertion points on the humerus and body skeleton, see electronic supplementary material, figure S6d,e) with the progression in the flapping cycle, in accordance with the anatomical features. Results show that at the beginning of downstroke, PECT force direction was oriented ventrally by 46° (median, range 38–48°) from PPH–PPS (electronic supplementary material, figure S6d,e and movies S1–S3). During downstroke, PECT force rotated dorsally and became almost aligned with PPH–PPS towards the end. Similarly, at the beginning of upstroke, SUPRA force was oriented dorsally by 57° (median, range 39°–88°) from PSH–PSC (electronic supplementary material, figure S6d,e) and became more aligned with PSH–PSC (median 9°, range 0–44°) at the end of upstroke. Overall, the vectoring of PECT and SUPRA forces show highly elaborated spatio-temporal patterns (electronic supplementary material, figure S6), which are more prominent than those observed in other birds such as pigeons [31]. As a result, they lead to highly three-dimensional wing actuation torque described below.

(c) . Predicted wing actuation torque characteristics: primary versus secondary muscle groups and active versus passive muscle torques

The wing actuation torque is characterized here about stroke, deviation and pitching axes defined with respect to HUP (i.e. the humerus–ulna plane which can be considered as the rigid, proximal part of the wing, figure 1a), since all the muscles that transfer force from a hummingbird's body to its wing insert only on the bones that lie entirely on HUP. For clarity, only results from wrist-centred model variations are shown in figure 5, while those from elbow-centred and body-centred model variations are shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S7.

(i) . Stroke

The wing stroking torque was mainly generated by PECT and SUPRA (figure 5a), with negligible contribution from combined secondary muscle groups. Both PECT and SUPRA provided peak stroking torque near the start of their half-strokes (figure 5a(i)). The peak stroking torque of PECT was estimated 1.51 (median, range 1.03–1.90) times higher than those of SUPRA (figure 5a(iii)). The peak passive stroking torques produced by these two muscles were comparable (figure 5a(iii)).

(ii) . Deviation

The wing deviation torque mainly counterbalanced the elevation (deviation torque towards head) torque due to aerodynamic lift at the beginning of the downstroke and overcame wing inertia near the beginning of the upstroke (figure 5b(ii)). The wing deviation torque was primarily generated by PECT at the beginning of the downstroke and by SUPRA at the beginning of the upstroke, both in the caudal (depression) direction (figure 5b(iii)). The secondary muscle groups, however, produced elastic torque that acted against the depression torque from PECT and SUPRA over the entire flapping cycle. In addition, they also produced a large active elevation torque during the downstroke against the PECT depression torque (figure 5b(iii)). The active elevation torque from the secondary muscle groups showed some variation among body-centred, elbow-centred and wrist-centred model variations (electronic supplementary material, figure S7); however, in general, they tended to counteract against the active deviation torque from two primary muscles, especially during the downstroke. We defined such counteraction between two sources of active muscle torque as ‘controlled-tightening effect’.

(iii) . Pitching

The wing muscles functioned as ‘active stoppers’ to resist the passive wing pitching, generated by both aerodynamic and inertial effects in the first half of each half-stroke (figure 5c(ii)). Specifically, SUPRA generated pronation torque against the passive wing supination during ventral stroke reversal, and PECT and secondary muscles primarily generated supination torque against the passive wing pronation during the beginning of downstroke (figure 5c(ii)). The instantaneous pitching torque generation by PECT and SUPRA is visualized in electronic supplementary material, figure S6c. The pronating action of SUPRA and supinating action of PECT for hummingbirds are opposite to what has been observed in other birds such as pigeons [32], which can be attributed primarily to the differences in the role of humeral long-axis and non-long axis rotation. In hummingbirds humeral long-axis rotation primarily generates stroking [5] and we found that pitching is generated primarily via humeral non-long axis rotation (electronic supplementary material, figure S6), whereas in pigeons [32] pitching is generated primarily via humeral long-axis rotation.

Similar to deviation, there was consistent counteraction between torques due to primary and combined secondary muscle groups (figure 5c(i) and (iii)) near the middle of each half-stroke, despite more significant model-dependent variations (electronic supplementary material, figure S7c). Notably, for elbow-centred model variations, the active pitching torque due to secondary muscles was nearly zero throughout the flapping cycle while the active pitching torque due to primary muscles was lower.

Note that although the deviation and pitching torques generated by secondary muscles were comparable to the stroking torque in magnitude, their forces are expected to be significantly lower than those of primary muscles, because they use substantially larger moment arms (electronic supplementary material, figure S4c). In addition, they are also able to produce peak instantaneous power comparable to those of PECT (figure 3f) for a similar reason, despite their small size. In addition, for both PECT and SUPRA, we found that if the force vector was directed linearly from its insertion point on the humerus to that on the body skeleton (i.e. without redirection offered by the curved bicipital crest for PECT), the relative contribution towards stroking would decrease, while those towards deviation and pitching would increase significantly.

(d) . Predicted co-activation of primary and secondary muscle groups

The counteracting action described above suggests that the primary and secondary flight muscles are nearly co-activated. This is further validated by examining the active force onset timings optimized for model variations that assumed independent activation of different muscle groups (figure 2b). Among these model variations, we found relatively small differences in the onset timings of active force or torque between the corresponding muscles from the three muscle groups (i.e. PMG, DMG and PiMG). The maximum difference between the active force onset timings of PECT and one of the DMG muscles was approximately 5% (of flapping cycle period), and between active force onset timings of PECT and one of the PiMG muscles was approximately 8% (electronic supplementary material, figure S5i, except for two wrist-centred model variations for which the difference was 18%).

4. Discussion

Based on our model predictions, the following three hypotheses can be generated for the principles of hummingbird wing actuation. Note that due to the small size of hummingbirds, testing these hypotheses or verification of predicted muscle behaviour may require techniques of in vivo muscle measurements that are currently unavailable; nonetheless, these hypotheses can provide insights into the biomechanics, evolution and robotic emulation of hummingbird flight that can be hopefully used to guide future experimental work.

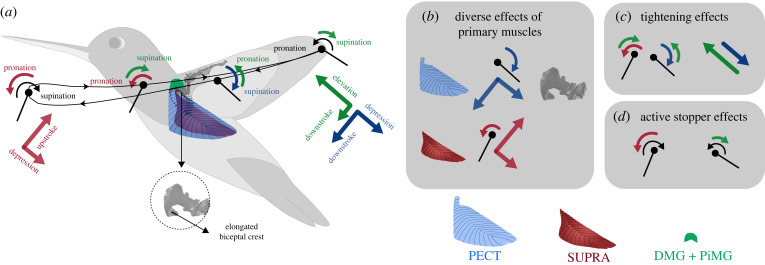

(a) . Primary flight muscles probably function as diverse effectors that rotate the 3DoF shoulder, which is probably actively tightened by secondary muscles in deviation and pitching

The predicted characteristics of wing actuation torque (figure 5) suggest that the primary muscles, i.e. hummingbirds' ‘flight engine’, do not simply ‘flap’ the wing along a single DoF, as the wing motion per se might appear to be; instead, they generate torque of comparable magnitude in all three wing axes of stroke, deviation and pitching. In addition, the wing deviation and pitching are predicted to be actively constrained by sizable counteracting torque from secondary muscles, resulting in a controlled-tightening effect and relatively small wing excursion (figure 6). Only in the stroke direction, however, is the wing allowed to rotate largely unconstrained so that there is a large excursion and muscle power output (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hypothesized principles of musculoskeletal wing actuation in hummingbirds. (a) Illustration of the torque produced by the pectoralis (PECT, blue), supracoracoideus (SUPRA, red) and combined secondary muscles (DMG and PiMG, green). (b) Pectoralis and supracoracoideus are predicted to function as diverse effectors, generating actuation torque in all stroke, deviation and pitching directions with comparable magnitude. Pectoralis is predicted to generate downstroke, supination and depression torques, and supracoracoideus is predicted to generate upstroke, pronation and depression torques (see electronic supplementary material, figure S6 for visualization). The diverse effects of pectoralis is associated with the evolution of a comparatively enormous bicipital crest on the humerus (shown in the inset). (c) The combined secondary muscles are predicted to create controlled-tightening effects in pitching and deviation by counteracting the primary muscles. (d) The muscles are predicted to function as ‘active stoppers’ for pitching, acting against the pronation or supination (black arrows) due to the aerodynamic and inertial effects. All the skeletal elements are shown in greyscale. See electronic supplementary material, movie S1 for illustration of these principles alongside wing skeleton movement. (Online version in colour.)

One potential benefit of such tightening, in the axes approximately orthogonal to the primary stroke axis, could be acquiring high wing agility and stability along deviation and pitching, which translate to higher control authority of flight dynamics. This is similar to the effects of the non-propulsive, counteracting lateral forces (orthogonal to the direction of locomotion) in legged locomotion [41]. Comparing wing deviation and pitching, the deviation is likely a more agile axis for wing motion modulation and therefore is likely recruited more extensively in flight control. This is because wing pitching dynamics often involve more complex, highly nonlinear wing camber and twisting (in both feathers and wrist joints). Changes in wing deviation, however, are less dependent on wing structural dynamics; they create not only fore/aft and lateral tilting (rotation about Yb and Xb directions, figure 1b, respectively) of the wing stroke plane for force vectoring (i.e. for generating body pitch and roll torque), but also modulate the wing angle of attack. Observations of hummingbird escape manoeuvre [3,42] seem to confirm these speculations, in that wing deviation exhibited the largest changes, and is indeed the strongest contributor for generating body pitch and roll torque. We predict that by changing the activation of secondary muscles, and with a relatively small force and power output, hummingbirds can modulate wing deviation to produce subtle, less intensive manoeuvres [43]. On the other hand, we predict that hummingbirds can also produce large-magnitude, more intensive manoeuvres, by changing the activation of primary muscles that lead to concurrent increase in stroke velocity and spatiotemporal modulation in deviation motion [3,42] (see next section). It is also worth noting that insects with advanced flight capacity and smaller body size than hummingbirds, such as flies and bees, do not seem to have the capability of modulating wing deviation and pitching directly using their power muscles [44]. Instead they rely mainly on smaller steering muscles for generating higher-order perturbations to the primary wing stroking motion [45,46]. The elevated capacity in wing deviation and pitching modulation might explain hummingbirds' ability for high degree of aerodynamic force vectoring that render them not conforming to the helicopter model [3,42].

(b) . Derived aspects of humerus morphology could enable pectoralis force vectoring that promotes both hovering and flight manoeuvrability

The humerus of hummingbirds has a morphology and function that is substantially different from those of other birds [8,47]. It was previously found that a high degree of long-axis rotation enables primary muscles with low strain to actuate large-amplitude wing motion [5]. Our results suggest that a significantly larger protrusion in the humerus (i.e. bicipital crest, figure 6) magnifies this effect while also facilitating optimal orientation of pectoralis force. First, the pectoralis force application point on the humerus is shifted away from the long axis due to its insertion on the proportionally enormous bicipital crest. This increases the moment arm for both wing stroking and pitching torque. Second, the shape of the bicipital crest appears to have evolved for properly orienting the pectoralis force direction. The hummingbird pectoralis can pull the humerus more caudally (tailward) compared with, for example, pigeons [18], thereby effecting wing depression (deviation) torque (electronic supplementary material, movie S3). This appears to be enabled by a more caudal orientation of the pectoralis muscle fascicles originating from the sternum and ribs. Such anatomy is necessary to balance the larger lift-induced wing elevation torque, as hummingbirds hover with an upright body posture. On the other hand, the bicipital crest on the humerus, where the pectoralis aponeurosis wraps around, prevents an excessive caudal redirection of the force (electronic supplementary material, figure S6e), ensuring proper distribution of the force into creating both stroking and deviation torque.

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that within a single contraction, the pectoralis can potentially generate concurrent downstroke, depression and supination torques that lead to coordinated changes in 3DoF wing motion, a way to promote manoeuvrability. This hypothesis is consistent with the wing kinematics modulation observed in the initiation phase of the hummingbird escape manoeuvre [3]; the bird simultaneously increases its stroke amplitude and frequency (increases total aerodynamic force), tilts its stroke plane backwards by depressing its wing caudally (directs the aerodynamic force backward) and uses larger supination during downstroke (increases the angle of attack and therefore backward force or maintains a proper angle of attack when wing loading increases due to higher stroke velocity). Therefore, while using kinematically ‘rigid’ wings without the flexion exhibited during upstroke in other species [9], hummingbirds seem to have more sophisticated torque control around the shoulder than other birds, which can primarily be attributed to the evolution of bicipital crest on humerus. We hypothesize that the evolutionary enlargement of the bicipital crest was a key process leading to the unique capacity of pectoralis in hummingbirds.

(c) . Hummingbirds probably use moderate elastic energy storage

The percentage elastic energy storage obtained in the past for power muscles of pigeons, locusts and bumblebees (see results), the cumulative work profiles obtained for hummingbird PECT and SUPRA (figure 3e), and the percentage negative work calculated for different species based on their work loops (assuming a majority of which represents elastic storage, figure 4c) suggest that percentage elastic energy storage is higher in hummingbirds than other birds, but less than many insects with comparable or smaller body size. In those insects, elastic energy storage is comparable to the energy dissipated to overcome aerodynamic drag (area enclosed by the workloop, figure 4c); while for larger birds, the majority of the muscular energy is spent to overcome aerodynamic drag with negligible elastic energy storage. The predicted work loops of PECT resemble more to those of larger birds but are shifted towards those of insects. This trend is also evident when comparing the timings of peak PECT (or power muscle) force (figure 4c), which for hummingbirds is intermediate to that of other birds and insects (especially those that use asynchronous flight muscles and likely use the greatest amount of elastic energy storage and mechanical resonance [48]).

Moderate elastic energy storage, as predicted here for hummingbirds, may reflect a trade-off between muscle efficiency and direct motor control capacity of primary muscles, and has implications to the actuation of bioinspired flapping flight. High elastic energy storage in some flying insects improves muscle efficiency for hovering at high wingbeat frequency [35] and may alleviate the demand for fast central motor control [49]. However, these benefits are at the cost of lower capacity for active, direct muscular control of wing stroking motion, which can only be modulated indirectly, e.g. by variable stiffness [50], or to a limited amount by steering muscles in insects [51]. Therefore, this trade-off could possibly influence the convergent evolution of hummingbirds towards insects. While hummingbirds have evolved towards hovering capacity with high wingbeat frequency and more symmetric flapping, they need to use proportionally more muscle–tendon elastic storage to overcome larger amount of wing inertial power, but proportionally less muscle–tendon elastic storage to retain direct muscular control of wing motion, and the solution seems to be in the middle ground. Together, the unique actuation capacity and the work loops of hummingbird primary muscles might also explain the distinct scaling rules in their wing morphology and frequency, when compared with other birds and flying insects, as previously observed by Greenwalt [52].

(d) . Principles of hummingbird wing actuation do not seem to be followed by existing designs of hovering-capable, hummingbird-inspired robots

In the past two decades, flapping flight in hovering-capable animals, such as hummingbirds and insects, has been perceived as a novel form of flight that can be emulated in micro aerial vehicles for improved flight stability and manoeuvrability. However, despite the success in developing flapping-wing robots with sustained hovering and basic manoeuvring capacity [4,10–16], these robots do not outperform rotary-wing micro aerial vehicles in terms of manoeuvrability and hovering efficiency.

So what is missing? If we examine the existing designs of hovering-capable, flapping-wing robots with wingspan similar to that of hummingbirds, we can find the following common design traits—first, the power actuators (e.g. electric motors [4,10–15] or electromagnetic actuators [16]) only drive a single-axis wing motion [4,10–16], i.e. flapping or stroking, while wing pitching is either passive [4,14–16] or independently modulated via twisting or slacking of the wing surface [10–13]; second, wing deviation is not used in the flight control and it is entirely hard constrained and third, some designs tend to maximize elastic energy storage [15] or promote a resonant actuation system [14–16] to improve efficiency. Apparently, these design traits do not follow the hypothesized principles of hummingbird wing actuation based on our model predictions; in other words, hummingbirds do not simply flap their wings as most of their robot mimics do.

These hypothesized principles and their implications on robotics need to be interpreted with the caution of size dependency, as they may not directly apply to smaller fliers, such as flies, bees or robots of similar size. Smaller body size poses more stringent constraints on wing actuation designs [53]; however, it offers inherently higher rotational manoeuvrability [42,54], which for smaller fliers, is mainly limited by sensorimotor control, rather than wing actuation [2]. For smaller flying insects, it is plausible that a high-frequency, primarily single-axis wing flapping generated by a strongly coupled thorax-wing oscillation, is size-appropriate. While insects use specialized steering muscles for higher order and smaller changes in wing kinematics [46,53], hummingbirds, on the other hand, use their musculoskeletal system to generate larger amounts of wing kinematic changes and force vectoring, thereby attaining comparable rotational manoeuvrability to their smaller insect counterparts [2], and also higher linear manoeuvrability at larger body size [42]. In sum, body size could be a critical factor when developing templates for flapping-wing robots inspired by hummingbirds or flying insects.

So how could the insights we provide help advance agile robotic flight? These principles do not directly translate into specific design guidelines or templates, and robot design and fabrication are subject to a myriad of technical challenges in actuators, materials, onboard electronics, power, sensors and constraints in size and weight. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that these principles could help roboticists, at least start to rethink and reshape the current design templates, hopefully leading to renewed attempts for designing flapping-wing robots that truly leverage the high control authority provided by flapping flight [55].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Jialei Song for providing guidance on CFD data interpretation.

Ethics

All of the animals were handled according to approved institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocols (062-17BTDBS-110317) of the University of Montana.

Data accessibility

All code for preprocessing, model optimization, plotting and analysis are available on GitHub repository: https://github.com/ska5623/Hummer_musculoskeletal_modelling.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [56].

Authors' contributions

S.A.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; B.W.T.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing; Z.A.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review and editing; H.L.: data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, software, writing—review and editing; T.L.H.: data curation, methodology, visualization, writing—review and editing; B.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) (Program Officer: Dr Marc Steinberg, award number: N00014-19-1-2540 to B.C., B.W.T. and H.L.).

References

- 1.Cheng B, Deng X, Hedrick TL. 2011. The mechanics and control of pitching manoeuvres in a freely flying hawkmoth (Manduca sexta). J. Exp. Biol. 214, 4092-4106. ( 10.1242/jeb.062760) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu P, Cheng B. 2017. Limitations of rotational manoeuvrability in insects and hummingbirds: evaluating the effects of neuro-biomechanical delays and muscle mechanical power. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170068. ( 10.1098/rsif.2017.0068) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng B, Tobalske BW, Powers DR, Hedrick TL, Wethington SM, Chiu GTC, Deng X. 2016. Flight mechanics and control of escape manoeuvres in hummingbirds. I. Flight kinematics. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3518-3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tu Z, Fei F, Deng X. 2021. Bio-inspired rapid escape and tight body flip on an at-scale flapping wing hummingbird robot via reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Robot. 37, 1742-1751. ( 10.1109/TRO.2021.3064882) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedrick TL, Tobalske BW, Ros IG, Warrick DR, Biewener AA. 2012. Morphological and kinematic basis of the hummingbird flight stroke: scaling of flight muscle transmission ratio. Proc. R. Soc. B. 279, 1986-1992. ( 10.1098/rspb.2011.2238) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zusi RL, Bentz GD. 1984. Myology of the purple-throated Carib (Eulampis jugularis) and other hummingbirds (Aves: Trochilidae). Smithson. Contrib. Zool. 385, 1-70. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welch KC, Altshuler DL. 2009. Fiber type homogeneity of the flight musculature in small birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 152, 324-331. ( 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.12.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dial KP. 1992. Avian forelimb muscles and nonsteady flight: can birds fly without using the muscles in their wings? Auk 109, 874-885. ( 10.2307/4088162) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobalske BW, Warrick DR, Clark CJ, Powers DR, Hedrick TL, Hyder GA, Biewener AA. 2007. Three-dimensional kinematics of hummingbird flight. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 2368-2382. ( 10.1242/jeb.005686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keennon M, Klingebiel K, Won H, Andriukov A. 2012. Development of the nano hummingbird: a tailless flapping wing micro air vehicle. In 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting Including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, 9–12 January 2012, Nashville, Tennessee. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. See https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2012-588. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karásek M, Nan Y, Romanescu I, Preumont A. 2013. Pitch moment generation and measurement in a robotic hummingbird. Int. J. Micro Air Veh. 5, 299-309. ( 10.1260/1756-8293.5.4.299) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phan HV, Kang T, Park HC. 2017. Design and stable flight of a 21g insect-like tailless flapping wing micro air vehicle with angular rates feedback control. Bioinspiration Biomim. 12, 036006. ( 10.1088/1748-3190/aa65db) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman D, Benedict M, Hrishikeshavan V, Chopra I. 2015. Design, development and flight-testing of a robotic hummingbird. In American Helicopter Society 71st Annual Forum, 5–7 May 2015, Virginia Beach, Virginia. Fairfax, VA: Vertical Flight Society. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh B, Chopra I. 2008. Insect-based hover-capable flapping wings for micro air vehicles: experiments and analysis. AIAA J. 46, 2115-2135. ( 10.2514/1.28192) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hines L, Campolo D, Sitti M. 2014. Liftoff of a motor-driven, flapping-wing microaerial vehicle capable of resonance. Robot. IEEE Trans. 30, 220-232. ( 10.1109/TRO.2013.2280057) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roll JA, Cheng B, Deng X. 2015. An electromagnetic actuator for high-frequency flapping-wing microair vehicles. IEEE Trans. Robot. 31, 400-414. ( 10.1109/TRO.2015.2409451) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song J, Luo H, Hedrick TL. 2014. Three-dimensional flow and lift characteristics of a hovering ruby-throated hummingbird. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140541. ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0541) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biewener AA. 2011. Muscle function in avian flight: achieving power and control. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 366, 1496-1506. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0353) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellerby DJ, Askew GN. 2007. Modulation of flight muscle power output in budgerigars Melopsittacus undulatus and zebra finches Taeniopygia guttata: in vitro muscle performance. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 3780-3788. ( 10.1242/jeb.006288) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedrick TL, Tobalske BW, Biewener AA. 2003. How cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) modulate pectoralis power output across flight speeds. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 1363-1378. ( 10.1242/jeb.00272) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahlman JW, Baliga VB, Altshuler DL. 2020. Flight muscle power increases with strain amplitude and decreases with cycle frequency in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb225839. ( 10.1242/jeb.225839) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Josephson RK, Malamud JG, Stokes DR. 2000. Asynchronous muscle: a primer. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 2713-2722. ( 10.1242/jeb.203.18.2713) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu MS, Daniel TL. 2004. Submaximal power output from the dorsolongitudinal flight muscles of the hawkmoth Manduca sexta. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 4651-4662. ( 10.1242/jeb.01321) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josephson RK, Stevenson RD. 1991. The efficiency of a flight muscle from the locust Schistocerca americana. J. Physiol. 442, 413-429. ( 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018800) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmour KM, Ellington CP. 1993. Power output of glycerinated bumblebee flight muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 183, 77-100. ( 10.1242/jeb.183.1.77) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biewener A, Patek S. 2018. Animal locomotion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tobalske BW, Biewener AA, Warrick DR, Hedrick TL, Powers DR. 2010. Effects of flight speed upon muscle activity in hummingbirds. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 2515-2523. ( 10.1242/jeb.043844) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagiwara S, Chichibu S, Simpson N. 1968. Neuromuscular mechanisms of wing beat in hummingbirds. Z. Vgl. Physiol. 60, 209-218. ( 10.1007/BF00878451) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobalske BW, Puccinelli LA, Sheridan DC. 2005. Contractile activity of the pectoralis in the zebra finch according to mode and velocity of flap-bounding flight. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 2895-2901. ( 10.1242/jeb.01734) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson MR, Dial KP, Biewener AA. 2001. Pectoralis muscle performance during ascending and slow level flight in mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). J. Exp. Biol. 204, 495-507. ( 10.1242/jeb.204.3.495) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soman A, Hedrick TL, Biewener AA. 2005. Regional patterns of pectoralis fascicle strain in the pigeon Columba livia during level flight. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 771-786. ( 10.1242/jeb.01432) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobalske BW, Biewener AA. 2008. Contractile properties of the pigeon supracoracoideus during different modes of flight. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 170-179. ( 10.1242/jeb.007476) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chai P, Chang AC, Dudley R. 1998. Flight thermogenesis and energy conservation in hovering hummingbirds. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 963-968. ( 10.1242/jeb.201.7.963) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells DJ. 1993. Muscle performance in hovering hummingbirds. J. Exp. Biol. 178, 39-57. ( 10.1242/jeb.178.1.39) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickinson MH, Lighton JRB. 1995. Muscle efficiency and elastic storage in the flight motor of Drosophila. Science 268, 87-90. ( 10.1126/science.7701346) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellington CP. 1984. The aerodynamics of hovering insect flight. VI. Lift and power requirements. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 305, 145-181. ( 10.1098/rstb.1984.0054) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexander RM, Bennet-Clark HC. 1977. Storage of elastic strain energy in muscle and other tissues. Nature 265, 114-117. ( 10.1038/265114a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J, Sun M. 2005. Unsteady aerodynamic forces and power requirements of a bumblebee in forward flight. Acta Mech. Sin. 21, 207-217. ( 10.1007/s10409-005-0039-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warrick DR, Tobalske BW, Powers DR. 2005. Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird. Nature 435, 1094-1097. ( 10.1038/nature03647) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pringle JWS. 1978. The Croonian Lecture, 1977-stretch activation of muscle: function and mechanism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 201, 107-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickinson MH, Farley CT, Full RJ, Koehl MARR, Kram R, Lehman S. 2000. How animals move: an integrative view. Science 288, 100-106. ( 10.1126/science.288.5463.100) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng B, Tobalske BW, Powers DR, Hedrick TL, Wang Y, Wethington SM, Chiu GT-C, Deng X. 2016. Flight mechanics and control of escape manoeuvres in hummingbirds. II. Aerodynamic force production, flight control and performance limitations. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3532-3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Altshuler DL, Quicazan-Rubio EM, Segre PS, Middleton KM. 2012. Wingbeat kinematics and motor control of yaw turns in Anna's hummingbirds (Calypte anna). J. Exp. Biol. 215, 4070-4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyan JA, Ewing AW. 1985. How diptera move their wings: a re-examination of the wing base articulation and muscle systems concerned with flight. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 311, 271-302. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balint CN, Dickinson MH. 2001. The correlation between wing kinematics and steering muscle activity in the blowfly Calliphora vicina. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 4213-4226. ( 10.1242/jeb.204.24.4213) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindsay T, Sustar A, Dickinson M. 2017. The function and organizaton of the motor system controlling flight maneuvers in flies. Curr. Biol. 27, 345-358. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karkhu AA. 1999. A new genus and species of the family Jungornithidae (Apodiformes) from the late eocene of the northern Caucasus, with comments on the ancestry of hummingbirds. Smithson. Contrib. Paleobiol. 89, 207-216. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenewalt CH. 1960. The wings of insects and birds as mechanical oscillators. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 104, 605-611. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gau J, Wold ES, Lynch J, Gravish N, Sponberg S. 2022. The hawkmoth wingbeat is not at resonance. Biol. Lett. 18, 20220063. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0063) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergou AJ, Ristroph L, Guckenheimer J, Cohen I, Wang ZJ. 2010. Fruit flies modulate passive wing pitching to generate in-flight turns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 1-4. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.148101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartussek J, Kadir Mutlu A, Zapotocky M, Fry SN. 2013. Limit-cycle-based control of the myogenic wingbeat rhythm in the fruit fly drosophila. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20121013. ( 10.1098/rsif.2012.1013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenewalt CH. 1960. Dimensional relationships for flying animals. Smithsonian miscellaneous collections, vol. 144. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deora T, Gundiah N, Sane SP. 2017. Mechanics of the thorax in flies. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 1382-1395. ( 10.1242/jeb.128363) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar V, Michael N. 2012. Opportunities and challenges with autonomous micro aerial vehicles. Int. J. Rob. Res. 31, 1279-1291. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bayiz YE, Cheng B. 2021. State-space aerodynamic model reveals high force control authority and predictability in flapping flight. J. R. Soc. Interface 18, 20210222. ( 10.1098/rsif.2021.0222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agrawal S, Tobalske BW, Anwar Z, Luo H, Hedrick TL, Cheng B. 2022. Data from: Musculoskeletal wing-actuation model of hummingbirds predicts diverse effects of primary flight muscles in hovering flight. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6318426) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Agrawal S, Tobalske BW, Anwar Z, Luo H, Hedrick TL, Cheng B. 2022. Data from: Musculoskeletal wing-actuation model of hummingbirds predicts diverse effects of primary flight muscles in hovering flight. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6318426) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All code for preprocessing, model optimization, plotting and analysis are available on GitHub repository: https://github.com/ska5623/Hummer_musculoskeletal_modelling.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [56].