Abstract

The repair of dermal wounds, particularly in the diabetic population, poses a significant healthcare burden. The impaired wound healing of diabetic wounds is attributed to low levels of endogenous growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), that normally stimulate multiple phases of wound healing. In this study, chitosan scaffolds were prepared via freeze drying and loaded with plasmid DNA encoding perlecan domain I and VEGF189 and analyzed in vivo for their ability to promote dermal wound healing. The plasmid DNA encoding perlecan domain I and VEGF189 loaded scaffolds promoted dermal wound healing in normal and diabetic rats. This treatment resulted in an increase in the number of blood vessels and sub-epithelial connective tissue matrix components within the wound beds compared to wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA or wounded controls. These results suggest that chitosan scaffolds containing plasmid DNA encoding VEGF189 and perlecan domain I have the potential to induce angiogenesis and wound healing.

Keywords: Perlecan, Proteoglycan, Vascular endothelial growth factor, Chitosan, Wound healing, Skin tissue engineering

1. Introduction

In the USA, it has been estimated that 1 to 2% of the population will experience a chronic wound during their lifetime [1] affecting approximately 6.5 million people [2]. That number is growing rapidly due to an aging population and an increase in the incidence of diabetes and obesity. The standard of care for these types of wounds is gauze bandages that have no inherent wound healing properties.

Re-epithelialization and angiogenesis of the wound site are critical events in the proliferative stage of dermal wound healing while the remodeling of dermal wounds includes changes in the expression of extracellular collagens and proteoglycans. In diabetes, dermal wound healing is characterized by prolonged inflammation, impaired neovascularization [3] and delayed re-epithelialization [4,5].

Growth factors play an important role in wound healing through promoting both angiogenesis and re-epithelialization. Growth factors including members of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) families promote wound healing. Members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family, including VEGF 121, 165, 189 and 205, contribute to multiple stages of wound healing by promoting angiogenesis, epithelialization and collagen deposition [6,7]. Due to the multi-faceted contribution of VEGF to wound healing, it was of interest to explore its potential for regenerative medicine applications. VEGF165 has been investigated for dermal wound healing as the levels of this growth factor are reduced in wounds. Their single dose application to wounds alone has had limited success due to the short half-life of growth factors [3]. Repeated topical delivery of VEGF165 promoted wound healing in diabetic mice including rapid re-epithelialization and enhanced angiogenesis compared to untreated controls [3], demonstrating the utility of growth factors for dermal repair in vivo. While VEGF is known to stimulate angiogenesis, it is also involved in modulating oxidative damage that is associated with diabetic wounds [8]. Plasmid DNA encoding VEGF165 loaded into collagen/chitosan scaffolds promoted blood vessel formation and faster resorption of the scaffolds [9, 10].

Plasmid DNA and growth factor delivery strategies to date have focused on the use of VEGF165, however the longer isoform of VEGF, VEGF189, binds more avidly to extracellular matrix (ECM) heparan sulfate proteoglycans, such as perlecan, than the VEGF165 isoform [11]. Both VEGF165 and VEGF189 stimulate vascularization; however VEGF189 must be released from the ECM to exert its mitogenic activity thus giving the advantage of a local distribution of VEGF in the wound site where the plasmid DNA was delivered. In contrast, VEGF165 is present both bound to the ECM and in a soluble form, giving rise to the possibility of this form acting on more distant tissues with unwanted side effects [12,13].

The ECM also provides many of the signals required for wound healing. Perlecan is an extracellular heparan sulfate proteoglycan expressed in the basement membrane of the dermoepidermal junction of normal skin fibroblasts [14], inflammatory cells and endothelial cells [15,16] and interacts with other basement membrane proteins, including fibronectin, laminin and type IV collagen, facilitating assembly and integrity of the basement membrane [17-19]. Additionally, perlecan heparan sulfate is required for dermal-epidermal homeostasis [20]. Mice lacking heparan sulfate chains attached to the N-terminal domain I of perlecan (Pln.DI) have delayed wound healing and impaired angiogenesis demonstrating the utility of this ECM molecule in wound healing [21]. Chronic venous ulcers have reduced expression of perlecan compared to normal skin [14]. Perlecan contributes to wound healing by acting as a reservoir for growth factors in the ECM and by binding and protecting them from proteolytic degradation via its heparan sulfate chains [22-26]. Perlecan heparan sulfate can regulate cell function by serving as a co-factor, or co-receptor, in growth factor interactions with their receptors and is necessary to induce signaling and growth factor activity [27-30]. Importantly, it has been shown that binding of heparin or heparan sulfate by VEGF165 is required for full activation of the VEGF receptor-2 [31]. However, the exogenous addition or over-expression of perlecan has not been explored in the context of cutaneous wound healing. As domain I of perlecan contains three glycosaminoglycan attachment sites that are most frequently decorated with heparan sulfate [32], this region of perlecan was explored in this study.

Many materials have been explored to promote cutaneous wound healing including synthetic hydrogels of poly(methacrylates) and polyvinylpyrrolidine that maintain a hydrated wound environment [33]. Natural polymers, including alginate and collagen, have also been explored alone, or in combination with, other polymers [33,34]. Collagen, a major component of the dermal ECM, has been processed into scaffolds and sponges with reported improvements in wound closure [35,36]. Chitosan is being widely explored to accelerate skin wound healing due to its hemostatic, anti-microbial and cyto-compatible properties [37,38]. This material also promoted granulation tissue formation, collagen expression and ECM organisation as well as inflammatory cell infiltration [39], which are all important hallmarks of wound healing. Chitosan scaffolds loaded with FGF2 promoted wound closure and granulation tissue formation to a greater extent than chitosan alone in a diabetic mouse model of wound healing [40].

The delivery of plasmid DNA encoding growth factors involved in wound healing is an alternative approach for the sustained expression of growth factors in the wound site. Transient delivery of DNA plasmid has low immunogenicity [41] with no evidence to date of associated neoplastic disease. Delivery of plasmid DNA alone in vivo is limited by its rapid degradation and clearance [42]. Due to the cationic nature of chitosan it has the ability to bind plasmid DNA enabling sustained delivery in vivo [9,43,44]. The delivery of genes encoding growth factors and their natural binding partners that provide protection against proteolytic degradation as well as potentiating their activity is the novel approach taken in this study. Plasmid DNA encoding VEGF189 was explored for the first time in this study as it binds more avidly to ECM heparan sulfates, such as those that decorate perlecan domain I enabling localized expression and delivery of this multi-faceted growth factor for epithelial wound healing. The aims of this study were to fabricate a chitosan scaffold loaded with plasmid DNA encoding perlecan domain I and VEGF189 and to investigate its ability to promote dermal wound healing in an in vivo full thickness wound healing model in normal and diabetic rats.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of chitosan scaffold

Chitosan (Primex, 580 Siglufjordur, Iceland) with a deacetylation degree of 79–90% and viscosity of 400 MPa·s was solubilized in 1% (v/v) acetic acid to a final concentration of 4% (w/v). The chitosan solution was poured into 15.2 × 15.2 mm silicone molds at 0.5 g cm−2, using 116 g of stock, and vibrated using a Whipmix professional vibrator until smooth. The chitosan was frozen at −80 °C for 1 h, removed from the mold and placed into 2 M NaOH. The scaffold was incubated for 16 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The chitosan scaffolds were rinsed in MilliQ water with several changes until the pH of the solution was neutral (typically 16 h). The chitosan scaffolds were frozen at −80 °C for 1 h and then freeze dried (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) at −40 °C and 110 psi for 48 to 72 h. The scaffolds were dissected in two for further experimentation.

2.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Chitosan scaffolds were coated with gold-palladium and examined by SEM (FEI Quant FEG 650) with secondary electron imaging and 10 kV accelerating voltage.

2.3. Compression strength

The mechanical properties of the scaffold are a consideration given the skin environment that is subjected to a range of biomechanical forces. In this study the compression strength of the scaffolds was performed as tensile testing was not possible due to the delicate nature of the scaffolds once hydrated, particularly the commercial materials that became sponges. The compression strength of the chitosan scaffold (15.2 × 7.6 mm) was compared with commercially available collagen (Resorbable Collagen Plug, Tissue Specialists, Little Rock, AK, USA) and chitosan (HemCon Dental Dressing, HemCon Medical Technologies Inc., Portland, OR, USA) sponges. Compression strength was determined using a strain rate of 0.5 mm min−1 and a 500 N load cell on an Instron Universal Tester 5565 with Bluehill 2 software. Measurements were taken in duplicate in both dry and wet conditions and presented as the load at 30% compression. For dry conditions, materials were placed in a desiccator for 24 h prior to analysis and analyzed immediately after removal from the desiccator. For wet conditions, the sponges were removed from the desiccator that had been prepared in the same way as the dry samples and then soaked in MilliQ water for 5 min before analysis.

2.4. Scaffold degradation rate

Degradation of chitosan scaffolds was measured in vitro by incubation of the scaffolds (8 mm diameter discs with a height of 3 mm) in 200 μL of either 15 mg/L lysozyme or 100 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for up to 72 h. Prior to exposure to the protein solutions, the dry mass of the scaffolds was determined. Scaffolds were imaged each day using a phase contrast microscope after exposure to the protein solutions. Scaffolds were then dried and the remaining mass recorded and compared to the initial dry mass of the scaffolds.

2.5. Construction of perlecan-VEGF transgene

The mammalian expression plasmid, pBI-CMV1-Kan (Clonetech Laboratories Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), is a bidirectional expression vector enabling the simultaneous, yet separate expression of two proteins. This vector was used to express both the N-terminal region of human perlecan (amino acids 1–248) and VEGF189 (including the signal peptide). Base modifications were made to the cDNA inserted into the vector to enable efficient translation, to eliminate the possibility of specific recombination events in vivo, and to allow specific in situ recognition. The Hspg2 sequence for the N-terminal region of perlecan included bases 81–855 in NM_005529.6 with modifications [45]. The VEGF189 sequence included bases 1039–1676 in NM_001171624.1 with modifications and the inclusion of EcoRI/Bg1II cloning sites.

2.6. Preparation of plasmid loaded chitosan scaffolds

Chitosan scaffolds were cut with a biopsy punch to 8 mm in diameter discs that were 3 mm in height with a total volume of 150 mm3. Plasmid DNA (0.25 μg/μL diluted in water) and lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, USA) were mixed in equal volumes and allowed to incubate for 20 min prior to the addition of 2% (w/v) sucrose. The sponges were soaked in 100 uL of plasmid mixture for 30 min at room temperature at which time the scaffold had absorbed the plasmid mixture. Plasmid-loaded scaffolds were stored at 4 °C until used for experimentation.

2.7. Plasmid loading efficiency in chitosan scaffolds, elution and activity

To determine the plasmid loading efficiency, chitosan scaffolds were exposed to 140 μL of 100 μg/mL plasmid in Lipofectamine 2000 and sucrose (as described above) and allowed to maximally absorb the loading solution for 1 h at room temperature. Aliquots (3, 6 and 12 μL) of the loading solution not absorbed by the scaffolds were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide to visualize. Known amounts of plasmid (0.24, 0.48 and 0.96 μg DNA) were electrophoresed on the same gel. Densitometric analysis of the DNA bands was used to determine the amount of DNA remaining in the loading solution and calculate the amount absorbed into the scaffolds.

To measure elution of the plasmid from the chitosan scaffold, chitosan scaffolds were exposed to 220 μL of 100 μg/mL plasmid in Lipofectamine 2000 and sucrose (as described above) and allowed to maximally absorb the loading solution for 30 min at room temperature. Scaffolds were then incubated for 7 days at 37 °C in PBS-NaN3. Aliquots of the supernatant were obtained at days 1, 2 and 7 post-incubation and lyophilized to concentrate the DNA. Scaffolds were frozen at −80 °C for 1 h and then freeze dried at −40 °C and 110 psi for 48 h. Lyophilized samples and scaffolds were reconstituted in agarose sample buffer (glycerol, bromophenol blue, 0.5% SDS) and electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

2.8. In vitro transfection of cells using plasmid loaded chitosan scaffolds

A Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA also encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) was loaded into the chitosan scaffolds (as described above) and scaffolds were exposed to confluent layers of HEK-293 cells for a period of 48 h in DMEM culture medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Cells were imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) to determine transgene expression via GFP expression.

2.9. In vivo full thickness wound healing model

All animal studies were performed in compliance with and under the oversight of the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Alabama. Retired breeder male Lewis rats (Charles River Laboratories) and Zucker Diabetic Fatty diabetic rats, >250 g, were maintained in standard housing, two per cage, with bedding changed three times weekly. Food and water were provided ad libitum and replaced as needed. Rats were chosen randomly, and studies were performed in a double-blind manner so that the operator did not know which location was receiving experimental or control materials. Animals were monitored daily for signs of distress and closely examined if distress was apparent. Animals with infections or other issues were excused from the study.

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (4–5% induction, 2% maintenance) for all procedures. Rats were shaved on the dorsum and remaining fur removed by Veet depilatory cream. The skin was then cleaned with three applications of 70% (w/v) alcohol. Full thickness wounds up to, but not including, the fascia were made with an 8 mm diameter round biopsy punch in each animal. Wounds were prepared approximately 2 cm apart in an anterior posterior square in the midline of the back. The wounds were cleaned with 100 μg/mL ampicillin after bleeding had curbed and were then immediately given the allocated treatments.

2.9.1. Comparison of chitosan scaffolds and commercial collagen sponges

Each normal rat received all three treatment conditions: (1) a lyophilized chitosan scaffold (2) a commercial collagen sponge, or (3) no scaffold. All wounds were protected with Tegaderm® film for 2 weeks to prevent trauma. Dressings were not changed throughout the first 2 weeks of the experimental period so as not to disturb the healing epithelium. After 2 weeks, the Vetwrap™ was removed and the Tegaderm® trimmed to the edges of the wound beds. The wounds were biopsied and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen at 14 days post-surgery.

2.9.2. Comparison of plasmid loaded or unloaded chitosan scaffolds

Each rat received all three treatment conditions: (1) a lyophilized chitosan scaffold pre-loaded with 10 μg Pln.D1-VEFG189 plasmid DNA, (2) a chitosan scaffold pre-loaded with 10 μg plasmid carrying no expression transgene, or (3) no scaffold. All wounds were protected with Tegaderm® film for 2 weeks to prevent trauma. Dressings were not changed throughout the first 2 weeks of the experimental period so as not to disturb the healing epithelium. After 2 weeks, the Vetwrap™ was removed and the Tegaderm® trimmed to the edges of the wound beds. The wounds were biopsied and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen at 14 days (normal rats) or 14, 21 and 28 days (diabetic rats) post-surgery.

2.9.3. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

After biopsy, total RNA was extracted from 50 μm frozen sections of the dermis using the RNAqueous-micro kit and treated with DNase I (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). cDNA was mixed with the forward (5′-AAC tCC gCC CCA ttg ACg CA-3′) and reverse (5′-gCA tCt ggCt ggC ggt CAC t-3′) primers for Pln.DI (modified) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq system (CloneTech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA). Cyclophilin was used as an endogenous control. Samples were analyzed in a MyiQ™ qPCR machine (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.10. Immunohistochemistry

Frozen tissue biopsies were cryosectioned and stored in Surgipath Cytology Fixative (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) prior to staining. Serial sections were taken from the center of the wound at 7 μm thickness. Histological characterization was undertaken through the use of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome and immunolocalization of perlecan, VEGF, laminin and collagen type IV. Following rehydration, slides were stained with Harris hematoxylin (Fronine, Australia) for 10 min, followed by eosin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Taren Point, NSW, Australia) for 5 min, before dehydrating and mounting. Masson's trichrome staining was performed using a kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For antibody staining, the slides were washed with TBST and then blocked with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The slides were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 1% w/v BSA in TBST at 4 °C for 16 h. Primary antibodies used included rabbit polyclonal anti-perlecan (CCN-1, 1:1000, raised in-house against immunopurified human endothelial cell-derived perlecan [56]), mouse monoclonal anti-VEGF (clone VG-1, Abcam, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 10 μg/mL), rabbit polyclonal anti-laminin (product code 600-401-116-0.5, Rockland, Limerick, PA, USA; 1:100 dilution) or rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen type IV (product code ab6586, Abcam, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; 1:100 dilution). Slides were then washed twice with TBST before incubating with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1:500) for 1 h at RT. The slides were washed twice with TBST then incubated for 30 min with streptavidin-HRP (1:250), rinsed four times with TBST before colour development with NovaRED® chromogen stain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin (Gill's #3, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 3 s and rinsed with deionized water.

Outcomes were determined by histological analysis of biopsy blocks sectioned midway through the wounds. Outcomes included a dichotomous score of complete epithelial wound closure, number of rete pegs >3 cells in length across the wound bed per mm, and a score for the maturity of the sub-epithelial dermal matrix of the healing wound, (0–5; adopted from [46]), scored blindly by two trained clinicians (Table 1). Masson's trichrome stained sections were analyzed for the number of newly-formed blood vessels in the wound sites of each treatment condition by counting the number of regions where erythrocytes were identified. Wound margins were identified based on changes in the collagen expression.

Table 1.

Scoring system for sub-epithelial matrix maturation.

| Score | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | None to minimal matrix accumulation. No granulation tissue. |

| 1–2 | Granulation tissue dominated by inflammatory cells but with minimal fibroblasts, capillaries, or collagen deposition. |

| 2–3 | Moderately thick granulation tissue, moderate inflammation, moderate fibroblasts and collagen deposition, but with extensive neovascularization. |

| 3–4 | Thick, vascularized granulation tissue dominated by fibroblasts and extensive collagen deposition. |

| 4–5 | Thick vascularized granulation tissue dominated by fibroblasts and extensive collagen deposition, demonstrating parallel collagen fiber organisation. |

2.11. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post-hoc test to compare multiple conditions. Dichotomous outcomes for the re-epithelization data were examined by a chi-square test. Results of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Additionally, selected data were analyzed with a Pearson's chi-squared test.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of chitosan scaffolds

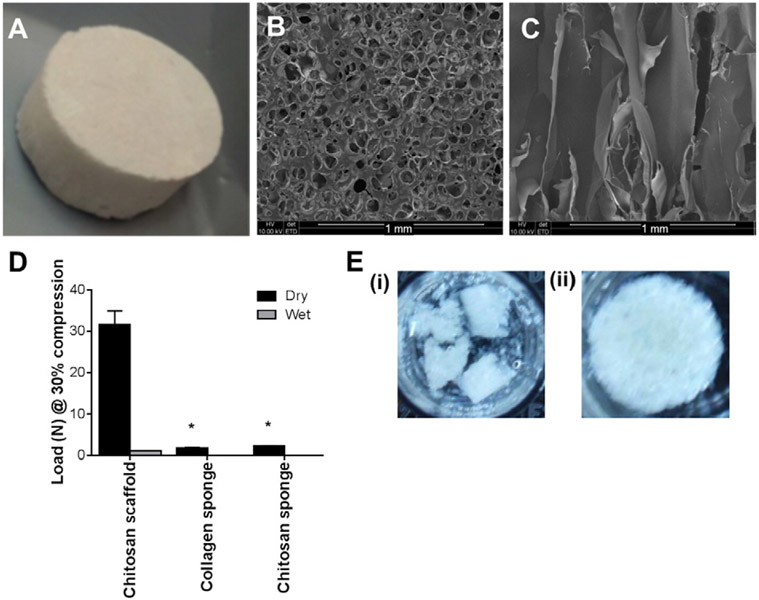

Chitosan scaffolds were analyzed by SEM for surface and internal morphology. A macroscopic view of the scaffolds and SEM analysis of the surface of the scaffolds indicated their porous structure with surface pores in the size range of 0.1 to 0.15 mm in diameter (Fig. 1A and B). A cross-section of the scaffolds indicated that the pores extended throughout the scaffolds (Fig. 1C). The mechanical properties of the chitosan scaffolds were assessed by measuring the load at 30% compression which was approximately 32 N for the dry scaffold and 1 N for the scaffolds after hydration. The compression strength was compared to commercially available collagen and chitosan sponges and the chitosan scaffolds exhibited higher compression strength under both wet and dry conditions compared to these sponges (Fig. 1D). Both of the commercially available sponges became gels upon hydration yielding no compression strength.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of chitosan scaffolds including a (A) macroscopic view and (B) SEM image of the surface of the chitosan scaffold. Scale bar represented 1 mm. (C) SEM of a cross-section of the chitosan scaffold. Scale bar represented 1 mm. (D) Load at 30% compression of the chitosan scaffolds compared to commercially available collagen and chitosan sponges under both dry and wet conditions (n = 2). (E) Images of chitosan scaffolds after 72 h of incubation at 37 °C in either (i) lysozyme or (ii) BSA. *Indicated significant differences compared to chitosan scaffold analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.05.

The scaffolds incubated in lysozyme had begun to break down within the 72 h analysis period with only fragments of the scaffold remaining (Fig. 1E (i)), while scaffolds incubated under the same conditions in BSA showed minimal degradation during this time (Fig. 1E (ii)). Analysis of the dry weight of the scaffolds before and after 48 h of exposure to the protein solutions indicated that the lysozyme treatment resulted in 29 ± 17% mass loss that was significantly greater than with BSA treatment that resulted in 0 ± 9% mass loss (p < 0.05). These data indicated that the chitosan scaffolds could degrade within a relevant time frame to enable efficient delivery of the plasmid DNA and cell transfection in vivo.

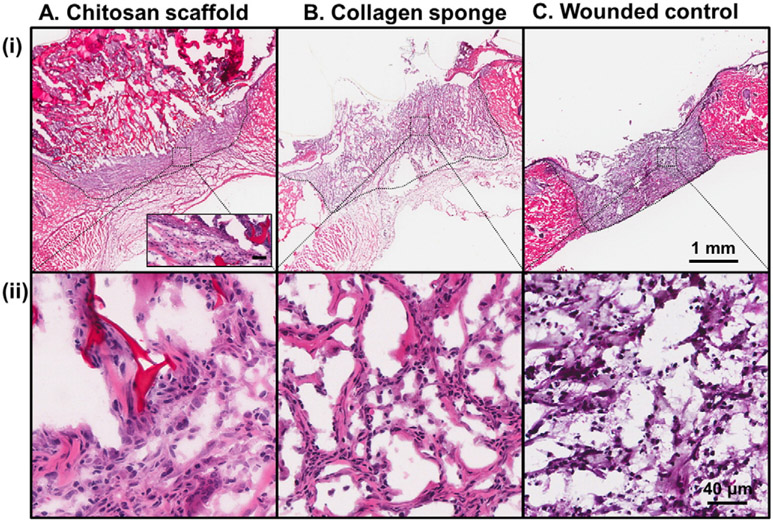

To determine the preferred material for plasmid DNA delivery to the wound site, a histological comparison of the tissue responses was performed at 14 days after wound creation and treatment with chitosan scaffolds, collagen sponges or no material treatment in normal rats. Sections of the tissue surrounding the implanted material were assessed by H&E staining (Fig. 2). The chitosan scaffold was visible in the tissue 14 days post injury (Fig. 2A (i) and inset) and resulted in cell infiltration into the central region of the wounded area (Fig. 2A (ii)) as well as re-epithelialization (Fig. 2A (i) and inset). The collagen sponge was quite diffuse at 14 days post injury with some cell infiltration into the central region of the wound (Fig. 2B (ii)), however this material supported limited re-epithelialization (Fig. 2B (i)). The site of wounding was visible at 14 days post injury in the wounded control with wound contraction as well as limited re-epithelialization (Fig. 2C (i)) and cell infiltration (Fig. 2C (ii)). Based on these analyses the chitosan scaffold was chosen to take forward in this study to analyze the effect of delivering Pln.D1-VEFG189 DNA for dermal wound healing in normal and diabetic rats.

Fig. 2.

H&E of dermal wounds created in normal rat after 14 days treatment with (A) chitosan scaffold, (B) collagen sponge or (C) wounded control. Wound margins are denoted by the dashed black lines. Higher magnification of cell infiltration into the central wounded area is shown in panel (ii) for each treatment. The inset in panel A (i) denotes the epithelial layer. Scale bar in panels (i) and (ii) represented 1 mm and 40 μm, respectively. Scale bar in panel A (i) inset represented 40 μm.

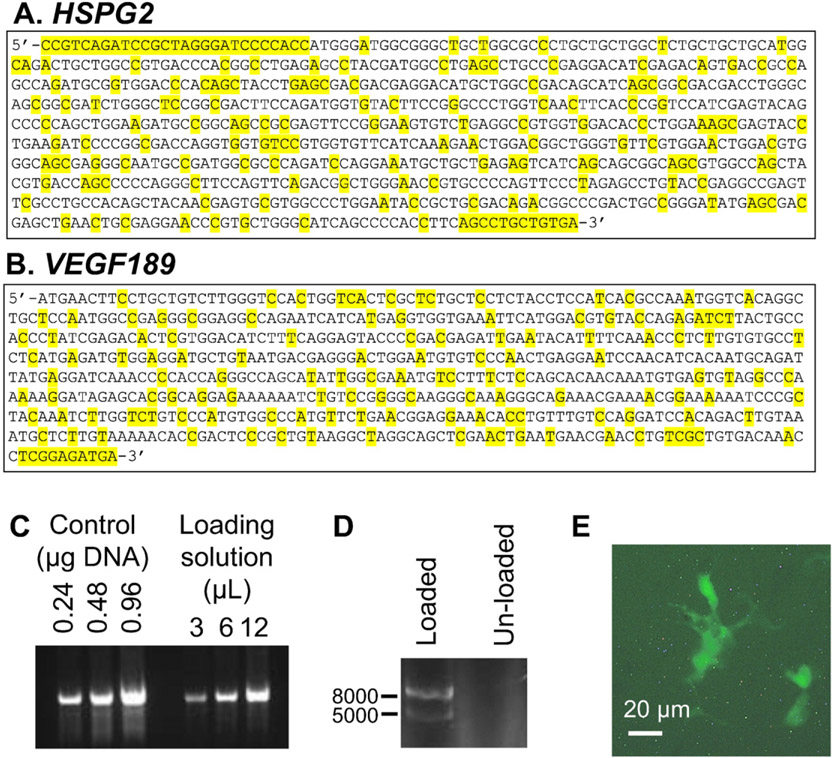

3.2. Plasmid loading and release from chitosan scaffolds and cell transfection in vitro

The mammalian expression plasmid, pBI-CMV1-Kan was used to express both the N-terminal region of human perlecan (Fig. 3A) and VEGF189 (Fig. 3B) with base modifications to enable efficient translation and to eliminate the possibility of specific recombination events in vivo. The loading efficiency of plasmid DNA into the chitosan scaffolds was assessed by measuring the amount of DNA remaining in solution after the scaffolds had absorbed a maximal amount of loading solution. Densitometry analysis of DNA present in the loading solution after exposure to the chitosan scaffolds was compared with known concentrations of DNA and indicated that approximately 8% of the initially loaded DNA remained in the loading solution (Fig. 3C). This equated to a loading capacity of 90 ng DNA/mm3 for the chitosan scaffolds.

Fig. 3.

The pBI-CMV1-Kan vector used to express both N-terminal perlecan (amino acids 1–248) and VEGF 189. (A) HSPG2 sequence (bases 81–855 in NM_005529.6) inserted into the vector. Base modifications compared with the human HSPG2 sequence are highlighted in yellow. (B) VEGF189 Sequence (bases 1039–1676 in NM_001171624.1) inserted in the vector. Base modifications compared with the human VEGF189 sequence are highlighted in yellow. (C) DNA gel of known amounts of DNA (control DNA loaded at 024, 0.48 and 0.96 μg/lane) and DNA present in remaining loading solution after exposure to the chitosan scaffold (3, 6 and 12 μL). (D) DNA gel of plasmid DNA loaded into chitosan scaffold compared to a chitosan scaffold that had not been loaded with plasmid DNA. (E) Fluorescence microscope image of HEK-293 cells expressing GFP indicating that they had internalized the plasmid DNA. Scale bar represented 20 μm.

Chitosan scaffolds loaded with the plasmid DNA were incubated with PBS-NaN3 for up to 7 days at 37 °C. The DNA released into the supernatant was analyzed after 1, 2 and 7 days of exposure of the scaffolds and electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and imaged. No DNA was detected in the supernatant at any of these time points (data not shown). At 7 days post exposure to the buffer, DNA was extracted from the chitosan scaffolds that were either loaded with plasmid DNA or left unloaded and examined by electrophoresis. Scaffolds loaded with DNA contained DNA at the expected band sizes of 5000 and 8000 bp while scaffolds not initially loaded with DNA did not contain DNA (Fig. 3D). To test that the plasmid DNA was active once loaded into the scaffolds, HEK-293 cells were exposed to chitosan scaffolds loaded with plasmid carrying the Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA for 48 h and analyzed for the expression of GFP encoded by the plasmid. Cells that had adhered to the sponge expressed GFP indicating that the chitosan scaffold was effective in delivering the plasmid to cells, enabling transfection and also expression of the GFP protein (Fig. 3E). Together these data qualitatively indicated that the chitosan scaffolds could be loaded with plasmid DNA that was able to induce gene expression in cells that contacted the scaffolds in vitro. Transfection efficiency was not determined as the goal of this study was to examine the effect of delivering the plasmid DNA in vivo, an environment with different mass transfer kinetics for transfection.

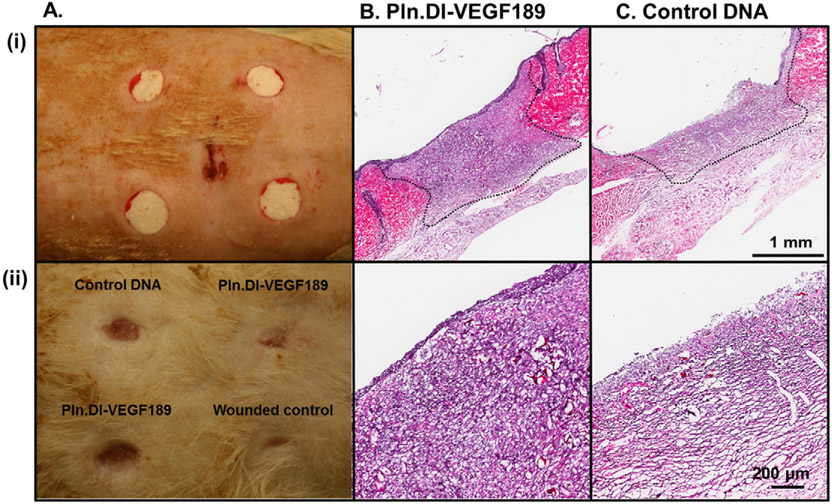

3.3. Analysis of wound healing in full thickness dermal wound healing model in normal rats

The ability of chitosan scaffolds loaded with Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA to promote dermal wound healing was assessed in normal rats. Dermal wounds were prepared using punch biopsy and treated with chitosan scaffolds containing either the Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA or control DNA (Fig. 4A (i)) and compared to a wounded control (Fig. 2C). After 14 days wounds were photographed (Fig. 4A (ii)) and assessed by H&E (Fig. 4B and C and Fig. 2C). The photographs indicated that the wounded control exhibited a greater level of wound contraction compared to the wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds, while there was variability in the level of wound contraction for the wounds treated with the scaffolds (Fig. 4A). Cell infiltration into the chitosan scaffolds was observed in both conditions (Fig. 4B and C). Re-epithelialization of the wounds treated with chitosan containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA was observed (Fig. 4B (i)) with the formation of multiple layers of keratinocytes (Fig. 4B (ii)). Wounds treated with chitosan containing control DNA exhibited incomplete closure of the epidermis that did not progress past the wound margins (Fig. 4C (i)) leaving much of the wound devoid of epithelium (Fig. 4C (ii)). The wounded control exhibited wound contraction as well as limited re-epithelialization and cell infiltration (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 4.

Photographs of wounds in normal rats immediately after surgery (A, i) and 14 days after surgery (A, ii) indicating placement of each treatment and the extent of healing. H&E of wounds in normal rats after 14 days of treatment with Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffold (B) or control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds (C). Wound margins are denoted by the dashed black lines. Higher magnification of cell infiltration into the central wounded area is shown in panel (ii) for each treatment. Scale bar in panels (i) and (ii) represented 1 mm and 200 μm, respectively.

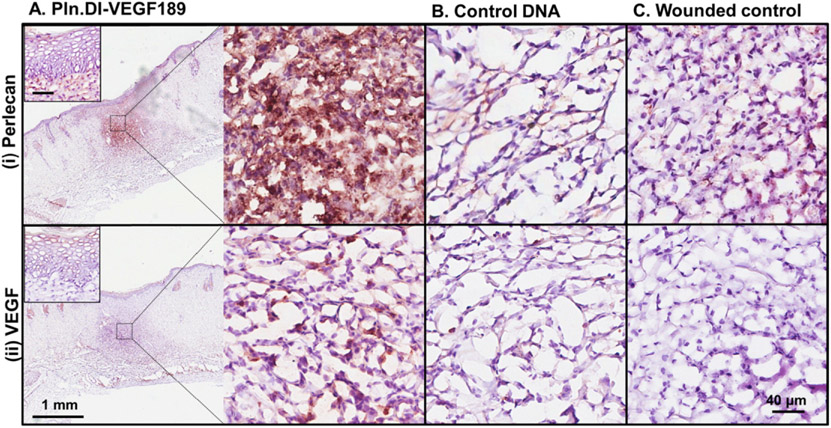

The wounds were analyzed for the expression of perlecan and VEGF to determine whether delivery of the Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA induced expression. Perlecan was present in the epidermis and healing region of dermal wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA for 14 days (Fig. 5A (i) and inset). Perlecan expression in similar healing regions of skin wounds treated with either chitosan containing control DNA or the wounded control was much reduced compared to wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 5A-C (i)). VEGF was detected in the epidermis and the healing region of skin wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA for 14 days (Fig. 5A (ii) and inset). Reduced expression of VEGF was detected in similar healing regions of skin wounds treated with chitosan containing control DNA (Fig. 5B (ii)). VEGF expression was absent in the wounded control (Fig. 5C (ii)). qPCR analyses indicated that the wound site expressed the Pln.DI (modified) gene at 2 days post treatment with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA with cycle times lower than the endogenous control, cyclophilin (Table 2). After 14 days of treatment the Pln.DI (modified) gene could be detected, however the cycle times were much higher than the endogenous control (Table 2). These data indicated that the Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA induced expression of both perlecan and VEGF189 in cells in the healing region of the skin wounds.

Fig. 5.

Expression of perlecan (i) and VEGF (ii) in normal rats after 14 days of treatment with (A) Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA, (B) control DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or (C) control wounds. The low magnification images in panel A reveal the wound site while the higher magnification images in panels A–C represent the healing region of the wounds. The insets in panel A represent the epidermis. Scale bar represented 1 mm (panel A) and 40 μm (panels A (and inset), B and C).

Table 2.

Cycle times (CT) for qPCR analysis of Pln.DI (modified) and cyclophilin gene expression in tissue surrounding implanted chitosan scaffolds containing plasmid DNA encoding Pln.DI-VEGF189. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation if n > 2 or range if n = 2.

| CT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal rats |

Diabetic rats |

|||

| 2 days | 14 days | 21 days | 28 days | |

| Pln.DI (modified) | 15.1 ± 2.2 (n = 6) | 39.7–44.5 (n = 2) | 33.9–36.4 (n = 2) | 34.5–40.2 (n = 2) |

| Cyclophilin | 29.1 ± 1.0 (n = 4) | 32.2 ± 0.7 (n = 4) | 30.8 ± 0.5 (n = 4) | 31.4 ± 0.5 (n = 4) |

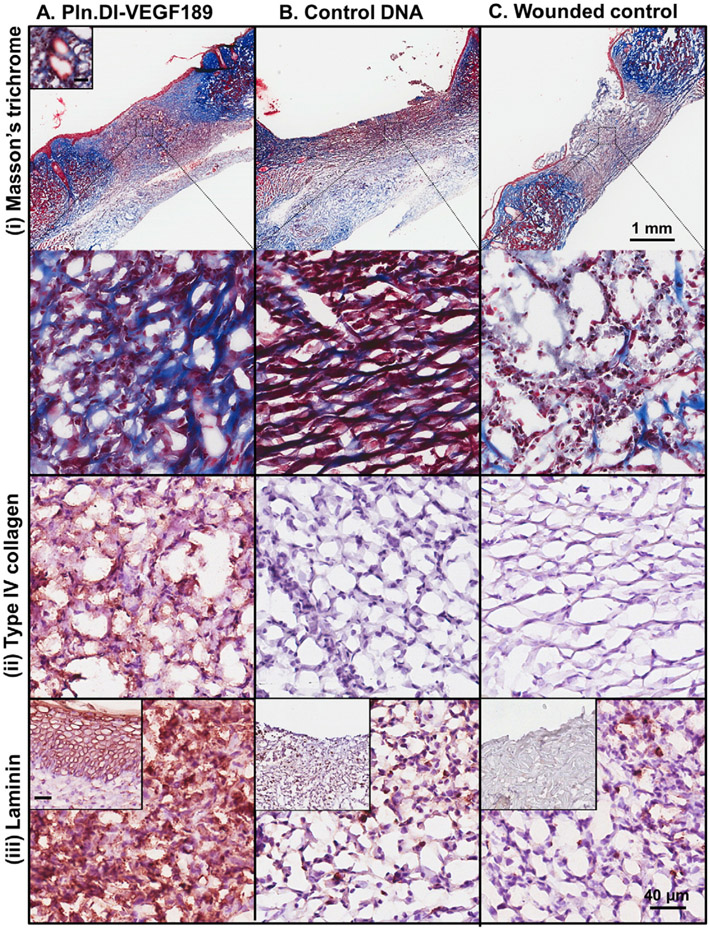

The wounds were also analyzed for the expression of extracellular markers of healing including collagen, keratin and laminin. Fibrillar collagen was deposited in the healing region of skin wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA for 14 days as detected in blue from the Masson's trichrome staining (Fig. 6A (i)) while reduced expression of collagen was detected in similar healing regions of dermal wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA or the wounded control (Fig. 6B and C (i)). Wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing the Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA were found to contain keratin detected in red from the Masson's trichrome staining in the epidermal layer (Fig. 6A (i)) while other treatment conditions did not result in the formation of the epidermis and keratin was not observed (Fig. 6B and C (i)). Collagen type IV was immunolocalized to the healing region of skin wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 6A (ii)), but not in wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA or the wounded control (Fig. 6B and C (ii)). Laminin was immunolocalized to the healing region of skin wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 6A (iii)), and reduced expression was observed in wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA or the wounded control (Fig. 6B and C (iii)). Laminin was also localized to the epidermis in wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 6A (iii) inset), but not the other conditions (Fig. 6 B and C (iii) inset).

Fig. 6.

Expression of collagen and keratin (i), collagen type IV (ii) and laminin (iii) in normal rats after 14 days treatmentwith (A) Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA, (B) control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or (C) control wounds. Collagen and keratin were detected in panel (i) using Masson's trichrome that stains collagen blue, keratin red and nuclei red/brown. The inset in panel A (i) is a representative blood vessel. The low magnification images in panel A reveal the wound site while the higher magnification images in panels A–C represent the healing region of the wounds. The inset in panels A–C (iii) represent the epidermis. Scale bar represented 1 mm (panel A) and higher magnification images contained a scale bar that represented 40 μm and inset (panel A i and iii).

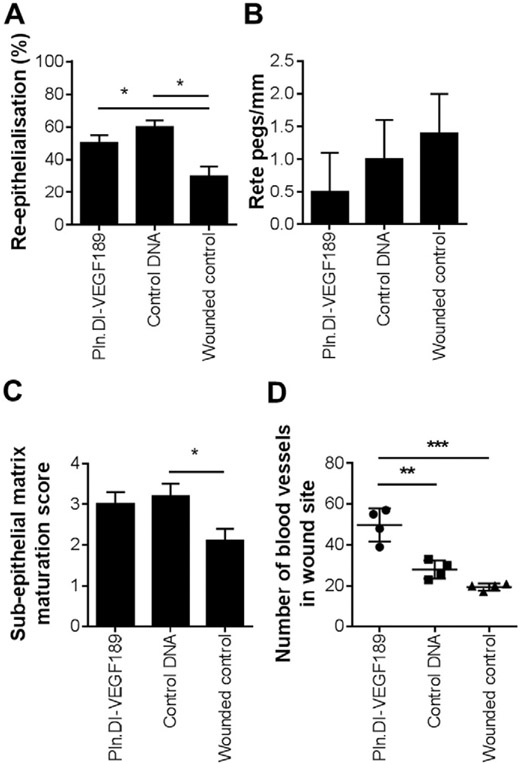

Analysis of 10 wounds from each condition indicated that wounds treated with chitosan containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA did not exhibit a significant (chi-square = 1.9) improvement in re-epithelialization compared to the other treatment conditions (Fig. 7A). The number of rete pegs/mm was analyzed as a measure of mature re-epithelialization resembling normal tissue. There was, however, no significant difference in the number of rete pegs between each of the treatment conditions (Fig. 7B). The extent of sub-epithelial matrix maturation was assessed using the criteria outlined in Table 1. Wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 were not significantly more mature than the wounded control, however the chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA were found to have a significantly (p < 0.05) higher sub-epithelial matrix maturation score than the wounded controls (Fig. 7C). Sections stained with Masson's trichrome indicated the formation of blood vessels in the wound site such as shown in Fig. 6 A (i) inset and were analyzed for the number of blood vessels in wound sites with each treatment (Fig. 7D). Treatment with chitosan loaded with Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA exhibited a significantly greater number of blood vessels in the wound site compared to wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds loaded with control DNA (p < 0.01) or wounded controls (p < 0.001). Together these data indicated that the chitosan scaffold enhanced sub-epithelial connective tissue healing within the wound beds and the additional delivery of Pln.DI-VEGF189 to the wound site resulted in more blood vessels, increased collagen, laminin, VEGF, and perlecan in normal, non-diabetic wounds after 14 days healing.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of the (A) extent of re-epithelialization (n = 10), (B) number of rete pegs/mm (n = 10), (C) sub-epithelial matrix maturation score (n = 10) and (D) number of blood vessels in wound sites (n = 4) for dermal wounds in normal rats after 14 days of treatment with Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds, control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or wounded controls. *Indicated significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.05. **Indicated significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.01. ***Indicated significant difference analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.001.

3.4. Analysis of wound healing in full thickness wound healing model in diabetic rats

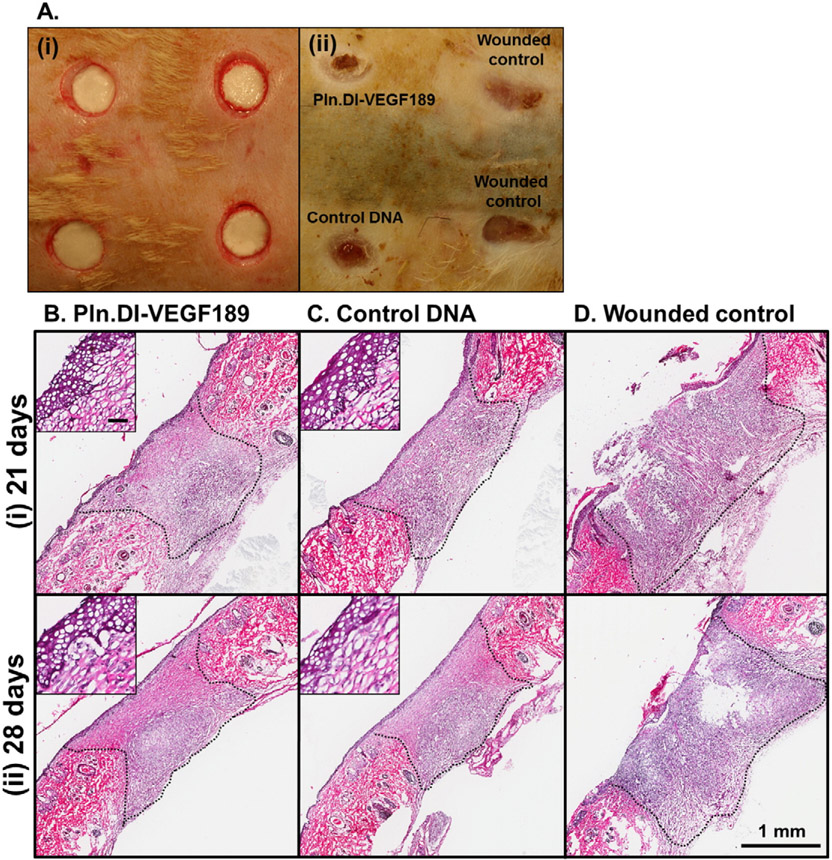

The ability of chitosan scaffolds loaded with Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA to promote dermal wound healing was also assessed in diabetic rats as wound healing in this model is characterized by delayed re-epithelialization and vascularization [47]. Minimal healing of dermal wounds in diabetic rats was observed after 14 days, so time points of 21 and 28 days were analyzed in more detail (Fig. 8). After 28 days wounds were photographed (Fig. 8A (ii)) and indicated that the wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds exhibited a greater degree of wound contraction than the wounded controls (Fig. 8A (ii)). After 21 and 28 days wounds were assessed by H&E and cell infiltration was observed into the chitosan scaffolds loaded with either Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA or control DNA (Fig. 8A and B (i) and (ii)). Re-epithelialization of the wounds treated with chitosan containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA or control DNA was observed at both time points (Fig. 8A and B (i) and (ii)) with the formation of multiple layers of keratinocytes (Fig. 8A and B (i) and (ii) inset). Wounded controls exhibited a healing matrix of less cellular and tissue density, and incomplete closure of the epidermis that did not progress past the wound margins (Fig. 8C (i) and (ii)) leaving much of the wound devoid of epithelium.

Fig. 8.

Photographs of wounds in diabetic rats immediately after surgery (A, i) and 28 days after surgery (A, ii) indicating placement of each treatment and the extent of healing. H&E of wounds in diabetic rats after (i) 21 and (ii) 28 days of treatment with (B) Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA loaded chitosan scaffold, (C) control DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or (D) wounded controls. Wound margins are denoted by the dashed black lines. Scale bar represented 1 mm and inset 50 μm.

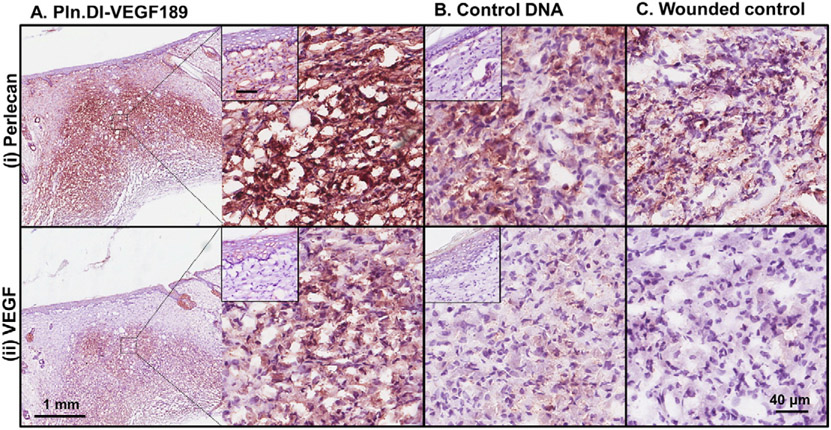

Perlecan was present in the basement membrane and the healing region of dermal wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA for 28 days (Fig. 9A (i) and inset). Perlecan expression in similar healing regions of dermal wounds treated with either chitosan containing control DNA or the wounded control was much reduced compared to wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 9A-C (i)). VEGF was detected in the epidermis and the healing region of dermal wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA for 28 days (Fig. 9A (ii) and inset). Reduced expression of VEGF was detected in similar healing regions of dermal wounds treated with chitosan containing control DNA (Fig. 9B (ii) and inset). VEGF expression was absent in the wounded control (Fig. 9C (ii)). qPCR analyses indicated that the wound site expressed the Pln.DI (modified) gene from chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA up to 28 days post-implantation, however the cycle times at both 21 and 28 days after treatment were higher than the endogenous control, cyclophilin indicating low levels of gene expression (Table 1). These data indicated that the Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA induced expression of both perlecan and VEGF189 in the healing region of the dermal wounds of diabetic mice.

Fig. 9.

Expression of perlecan (i) and VEGF (ii) in diabetic rats after 28 days of treatment with (A) Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA, (B) control DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or (C) control wounds. The low magnification images in panel A reveal the wound site while the higher magnification images in panels A–C represent the healing region of the wounds. The insets in panels A and B represent the epidermis. Scale bar represented 1 mm (panel A) and 40 μm (panels A (and inset), B (and inset) and C).

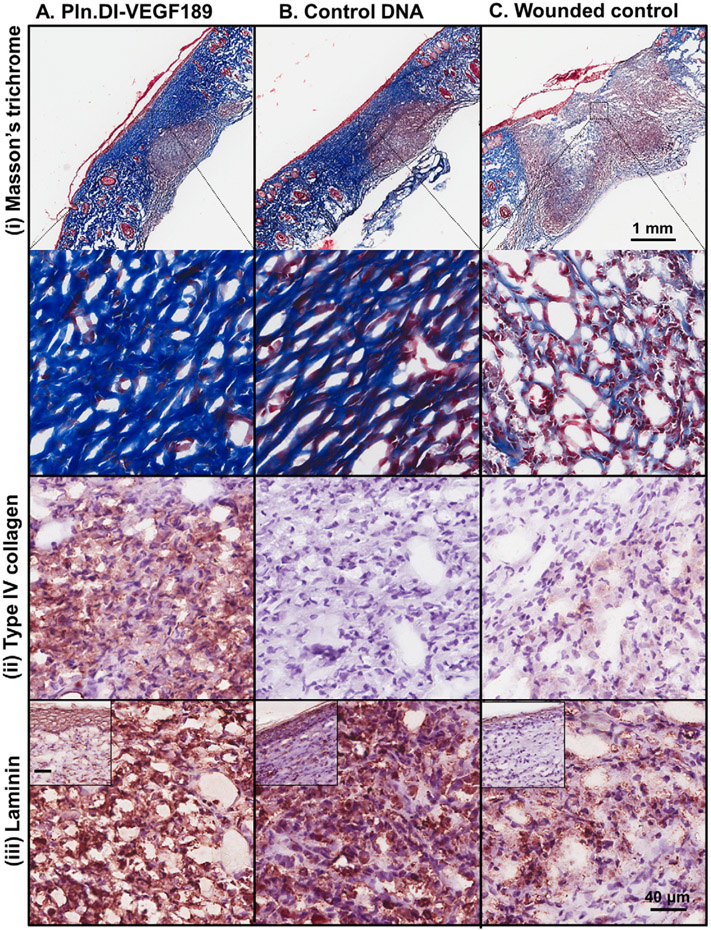

Fibrillar collagen was deposited in the healing region of dermal wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing either Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA or control DNA for 28 days as detected in blue from the Masson's trichrome staining (Fig. 10A and B (i)). Reduced levels of collagen were detected in similar healing regions of the wounded controls (Fig. 10C (i)). All wounds contained keratin that was detected in red from the Masson's trichrome staining in the epidermal layer (Fig. 10A-C (i)). Collagen type IV was immunolocalized to the healing region of dermal wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 DNA (Fig. 10A (ii)), with reduced expression in wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds containing control DNA or the wounded control (Fig. 10B and C (ii)). Laminin was immunolocalized to the healing region and epidermis of dermal wounds in all treatment conditions (Fig. 10A-C (iii) and inset).

Fig. 10.

Expression of collagen and keratin (i), collagen type IV (ii) and laminin (iii) in diabetic rats after 28 days of treatment with (A) Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA, (B) control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or (C) control wounds. Collagen and keratin were detected in panel (i) using Masson's trichrome that stains collagen blue, keratin red, nuclei and erythrocytes red/brown. The low magnification images in panel A reveal the wound site while the higher magnification images in panels A–C represent the healing region of the wounds. The inset in panels A–C (iii) represent the epidermis. Scale bar represented 1 mm (panel A) and higher magnification images contained a scale bar that represented 40 μm and inset (panels A–C (iii)).

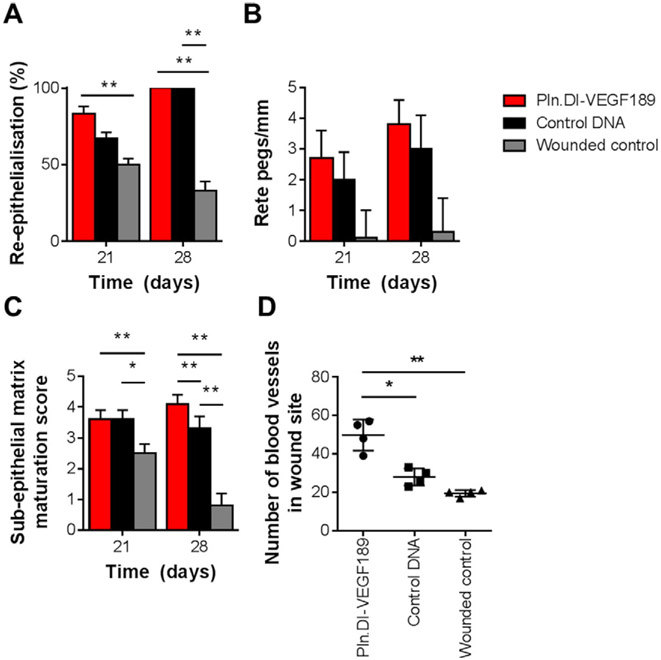

Analysis of multiple wounds from each condition indicated that, at the 21 day time point, the chitosan scaffold containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA was associated with the highest proportion of fully re-epithelialized wounds that were significantly more re-epithelialized than the wounded controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 11A). By the 28 day time point, all wounds treated with chitosan scaffold containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA exhibited complete re-epithelialization as did the wounds treated with the control DNA loaded chitosan scaffold (Fig. 11A).

Fig. 11.

Analysis of the (A) extent of re-epithelialization (21 days, n = 18; 28 days, n = 12), (B) number of rete pegs/mm (21 days n = 6; 28 days Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds n = 6, control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or wounded controls n = 3) and (C) sub-epithelial matrix maturation score (21 days n = 6; 28 days Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds n = 6, control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or wounded controls n = 3) in diabetic rats after 21 and 28 days of treatment with Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds, control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or wounded controls. (D) number of blood vessels in wound sites (n = 4) for dermal wounds in diabetic rats after 28 days of treatment with Pln.D1-VEGF189 plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds, control plasmid DNA loaded chitosan scaffolds or wounded controls. *Indicated significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.01. **Indicated significant differences analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test, p < 0.001.

By the same 28 day time period, only one third of the wounded controls had achieved complete re-epithelialization. Statistical analysis using the Pearson's chi-squared test indicated that wounds that received the chitosan scaffold containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA demonstrated re-epithelization to a significantly greater degree than the other two conditions combined (chi-square = 3.8) for combined data for 21 and 28 days healing. There was an increase in the number of rete pegs observed in the diabetic wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA compared to the other two treatment conditions at both 21 and 28 days, however this increase was not considered significant (Fig. 11B). Wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing either Pln.DI-VEGF189 or control DNA received a significantly higher maturation score than the wounded control treatments after both 21 (p < 0.05) and 28 days (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 11C). There was a significantly higher level of maturation between wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 and control DNA at 28 days (p < 0.01) while there was no significant difference between wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing Pln.DI-VEGF189 at 21 and 28 days (Fig. 11C). Sections stained with Masson's trichrome were analyzed for the number of blood vessels in wound sites treated with each condition after 28 days of treatment (Fig. 11D). Treatment of the wounds with chitosan loaded with Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA exhibited a significantly greater number of blood vessels in the wound site compared to wounds treated with either chitosan scaffolds loaded with control DNA (p < 0.01) or wounded controls (p < 0.01). Together these data indicated that the chitosan scaffold enhanced sub-epithelial connective tissue healing within the wound beds and the additional delivery of Pln.DI-VEGF189 to the wound site resulted in more blood vessels, increased collagen, laminin, VEGF, and perlecan in diabetic wounds after 28 days healing.

4. Discussion

Dermal wound healing involves a series of cell proliferation, migration and ECM formation steps to re-establish the natural barrier between the body and the external environment. During diabetes this process is delayed and displays changes in the formation of granulation tissue as well as defects in wound bed maturation, vascularization, inflammatory response and collagen deposition [48]. A major challenge for wound repair, particularly during diabetes, is supporting sufficient vascularization and avoiding necrosis in the wound site. Changes in the expression of growth factors involved in wound healing have led to the delivery of growth factors, particularly VEGF, or plasmid DNA encoding VEGF, to encourage vascularization. The former approach has had limited success due to the short half-life and stability of proteins in vivo [47]. The later approach has been explored through the delivery of plasmid DNA encoding VEGF165 either directly or within a scaffold and demonstrated enhanced vascularization in animal models [9,49,50]. These findings were corroborated in the present study along with the finding of enhanced re-epithelialization in wounds treated with chitosan scaffolds containing DNA encoding both VEGF189 and perlecan domain I.

Biomaterial-based interventions to improve wound healing have involved the use of scaffolds that enhance selected stages of wound healing while minimizing bacterial colonization of the wound. For these reasons chitosan has been extensively explored [37,38]. Coupled with the anti-bacterial properties of chitosan, it can promote mononuclear influx for wound bed maturation [51] and electrostatically interact with nucleic acids to support the delivery of DNA [32]. For these reasons, along with its desirable mechanical properties and performance in vivo, chitosan was the scaffold material selected for this study. While a scaffold should effectively bind with nucleic acids it must also facilitate the release of the plasmid DNA to enable cell transfection. Lysozyme, an abundant protease in wound environments, degrades chitosan [52, 53] and was confirmed to degrade the chitosan scaffolds prepared in this study in vitro. In vivo analyses in both normal and diabetic mice models in this study also demonstrated degradation of the chitosan scaffolds. This study confirmed that the chitosan scaffolds effectively delivered plasmid DNA and induced gene and protein level expression to cells both in vitro and in vivo through the expression of both perlecan and VEGF in the wound site in both normal and diabetic rat models of full thickness wounds. The sustained delivery of plasmid DNA over a period of 28 days in vivo, which was the longest time point tested, was also demonstrated. The expression of both VEGF and perlecan in the wounds analyzed in this study was due to the delivery of the plasmid DNA encoding both of these molecules, as delivery of control DNA in the chitosan scaffolds did not enhance the expression of VEGF or perlecan over the wounded controls. Similar findings have been reported previously for the delivery of DNA encoding VEGF165 [9,54].

This study showed that the delivery of DNA encoding both perlecan domain I and VEGF189 enhanced vascularization in the wounds. This result is supported by reports that the delivery of plasmid DNA encoding VEGF165 enhanced vascularization in various models including a porcine burn wound healing model [9] and a rat full thickness excision wound model involving the delivery of mesenchymal stem cells [55].

The co-expression of perlecan and VEGF189 in this study was utilized as the reduced expression of this abundant heparan sulfate proteoglycan in the ECM has been reported previously in wounds [14]. The over-expression of perlecan with its pendant heparan sulfate chains sought to generate an ECM in the wound site that was able to support the sequestration of the VEGF189 for local mitogenic activity. Indeed this strategy was demonstrated to be effective in vivo in both normal and diabetic rat models of full thickness wound healing with expression of both perlecan and VEGF189 localized in the wound beds where the chitosan containing Pln.D1-VEGF189 DNA was delivered. This finding is particularly significant for diabetic wounds which have an inefficient environment for wound healing. In addition to previous studies, this study also explored the effect on sub-epithelial matrix maturation as determined by collagen and laminin expression as well as rete peg formation and found that the expression of perlecan and VEGF189 promoted ECM component expression, including collagen, laminin and keratin, to a greater extent than either the delivery of chitosan with control DNA or wounded controls. The enhanced matrix deposition observed in this study is most likely due to the co-expression of perlecan as it is known to promote ECM assembly through interactions with collagens and laminins [18,19].

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that chitosan scaffolds prepared by freeze drying were able to be loaded with DNA encoding perlecan domain I and VEGF 189 and that this DNA loaded scaffold could transfect cells in vivo and in vitro. Chitosan scaffolds supported enhanced sub-epithelial matrix healing while scaffolds also containing DNA encoding both perlecan domain I and VEGF 189 promoted an increased number of blood vessels and enhanced sub-epithelial connective tissue remodeling of dermal wounds. The results revealed for the first time that transgenes can be used as therapeutic pro-drugs that can induce gene expression for up to one month in vivo. Thus, this is a promising approach for dermal wound healing that enables the delivery of biologics by providing a single plasmid that circumvents the need for repeated dosage as is required for the delivery of growth factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comparative Pathology Lab of the Animal Resources Program, and the University of New South Wales Histology and Microscopy Unit for technical assistance.

References

- [1].Gottrup F, A specialized wound-healing center concept: importance of a multidisciplinary department structure and surgical treatment facilities in the treatment of chronic wounds, Am. J. Surg 187 (2004) S38–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT, Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy, Wound Repair Regen. 17 (2009) 763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Galiano RD, Tepper OM, Pelo CR, Bhatt KA, Callaghan M, Bastidas N, Bunting S, Steinmetz HG, Gurtner GC, Topical vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates diabetic wound healing through increased angiogenesis and by mobilizing and recruiting bone marrow-derived cells, Am. J. Pathol 164 (2004) 1935–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brandner JM, Zacheja S, Houdek O, Moll I, Lobmann R, Expression of matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines, and connexins in diabetic and nondiabetic human keratinocytes before and after transplantation into an ex vivo wound-healing model, Diabetes Care 31 (2008) 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Usui ML, Mansbridge JN, Carter WG, Fujita M, Olerud JE, Keratinocyte migration, proliferation, and differentiation in chronic ulcers from patients with diabetes and normal wounds, J. Histochem. Cytochem 56 (2008) 687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA, Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis, Pharmacol. Rev 56 (2004) 549–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bao P, Kodra A, Tomic-Canic M, Golinko MS, Ehrlich HP, Brem H, The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing, J. Surg. Res 153 (2009) 347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Altavilla D, Saitta A, Cucinotta D, Galeano M, Deodato B, Colonna M, Torre V, Russo G, Sardella A, Urna G, Campo GM, Cavallari V, Squadrito G, Squadrito F, Inhibition of lipid peroxidation restores impaired vascular endothelial growth factor expression and stimulates wound healing and angiogenesis in the genetically diabetic mouse, Diabetes 50 (2001) 667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guo R, Xu S, Ma L, Huang A, Gao C, The healing of full-thickness burns treated by using plasmid DNA encoding VEGF-165 activated collagen-chitosan dermal equivalents, Biomaterials 32 (2011) 1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guo R, Xu S, Ma L, Huang A, Gao C, Enhanced angiogenesis of gene-activated dermal equivalent for treatment of full thickness incisional wounds in a porcine model, Biomaterials 31 (2010) 7308–7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robinson CJ, Stringer SE, The splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their receptors, J. Cell Sci 114 (2001) 853–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Park JE, Keller GA, Ferrara N, The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) isoforms: differential deposition into the subepithelial extracellular matrix and bioactivity of extracellular matrix-bound VEGF, Mol. Biol. Cell 4 (1993) 1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ferrara N, Binding to the extracellular matrix and proteolytic processing: two key mechanisms regulating vascular endothelial growth factor action, Mol. Biol. Cell 21 (2010) 687–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lundqvist K, Schmidtchen A, Immunohistochemical studies on proteoglycan expression in normal skin and chronic ulcers, Br. J. Dermatol 144 (2001) 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jung M, Lord MS, Cheng B, Lyons JG, Alkhouri H, Hughes JM, McCarthy SJ, Iozzo RV, Whitelock JM, Mast cells produce novel shorter forms of perlecan that contain functional endorepellin a role in angiogenesis and wound healing, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 3289–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Whitelock JM, Graham LD, Melrose J, Murdoch AD, Iozzo RV, Anne Underwood P, Human perlecan immunopurified from different endothelial cell sources has different adhesive properties for vascular cells, Matrix Biol. 18 (1999) 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Grant DS, Leblond CP, Kleinman HK, Inoue S, Hassell JR, The incubation of laminin, collagen IV, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan at 35 degrees C yields basement membrane-like structures, J. Cell Biol 108 (1989) 1567–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yurchenco PD, Cheng YS, Schittny JC, Heparin modulation of laminin polymerization, J. Biol. Chem 265 (1990) 3981–3991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kvist AJ, Johnson AE, Morgelin M, Gustafsson E, Bengtsson E, Lindblom K, Aszodi A, Fassler R, Sasaki T, Timpl R, Aspberg A, Chondroitin sulfate perlecan enhances collagen fibril formation. Implications for perlecan chondrodysplasias, J. Biol. Chem 281 (2006) 33127–33139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Iriyama S, Hiruma T, Tsunenaga M, Amano S, Influence of heparan sulfate chains in proteoglycan at the dermal-epidermal junction on epidermal homeostasis, Exp. Dermatol 20 (2011) 810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhou Z, Wang J, Cao R, Morita H, Soininen R, Chan KM, Liu B, Cao Y, Tryggvason K, Impaired angiogenesis, delayed wound healing and retarded tumor growth in perlecan heparan sulfate-deficient mice, Cancer Res. 64 (2004) 4699–4702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Soker S, Svahn CM, Neufeld G, Vascular endothelial growth factor is inactivated by binding to alpha 2-macroglobulin and the binding is inhibited by heparin, J. Biol. Chem 268 (1993) 7685–7691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gengrinovitch S, Greenberg SM, Cohen T, Gitay-Goren H, Rockwell P, Maione TE, Levi BZ, Neufeld G, Platelet factor-4 inhibits the mitogenic activity of VEGF121 and VEGF165 using several concurrent mechanisms, J. Biol. Chem 270 (1995) 15059–15065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ellis AL, Pan W, Yang G, Jones K, Chuang C, Whitelock JM, DeCarlo AA, Similarity of recombinant human perlecan domain I by alternative expression systems bioactive heterogeneous recombinant human perlecan D1, BMC Biotechnol. 10 (2010) 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Whitelock JM, Murdoch AD, Iozzo RV, Underwood PA, The degradation of human endothelial cell-derived perlecan and release of bound basic fibroblast growth factor by stromelysin, collagenase, plasmin, and heparanases, J. Biol. Chem 271 (1996) 10079–10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Muthusamy A, Cooper CR, Gomes RR Jr., Soluble perlecan domain I enhances vascular endothelial growth factor-165 activity and receptor phosphorylation in human bone marrow endothelial cells, BMC Biochem. 11 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ornitz DM, FGFs, heparan sulfate and FGFRs: complex interactions essential for development, BioEssays 22 (2000) 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schlessinger J, Plotnikov AN, Ibrahimi OA, Eliseenkova AV, Yeh BK, Yayon A, Linhardt RJ, Mohammadi M, Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization, Mol. Cell 6 (2000) 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Allen BL, Rapraeger AC, Spatial and temporal expression of heparan sulfate in mouse development regulates FGF and FGF receptor assembly, J. Cell Biol 163 (2003) 637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wu ZL, Zhang L, Yabe T, Kuberan B, Beeler DL, Love A, Rosenberg RD, The involvement of heparan sulfate (HS) in FGF1/HS/FGFR1 signaling complex, J. Biol. Chem. 278 (2003) 17121–17129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cebe Suarez S, Pieren M, Cariolato L, Arn S, Hoffmann U, Bogucki A, Manlius C, Wood J, Ballmer-Hofer K, A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 63 (2006) 2067–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gustafsson E, Almonte-Becerril M, Bloch W, Costell M, Perlecan maintains microvessel integrity in vivo and modulates their formation in vitro, PLoS One 8 (2013), e53715.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HNE, Eccleston GM, Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: a review, J. Pharm. Sci 97 (2008) 2892–2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Malafaya PB, Silver GA, Reis RL, Natural origin polymers as carriers and scaffolds for biomolecules and all delivery in tissue engineering applications, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 59 (2007) 207–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhong SP, Zhang YZ, Lim CT, Tissue scaffolds for skin wound healing and dermal reconstruction, WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2 (2010) 510–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gould LJ, Topical collagen-based biomaterials for chronic wounds: rationale and clinical application, Adv. Wound Care 5 (2016) 19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kong M, Chen XG, Xing K, Park HJ, Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and mode of action: a state of the art review, Int. J. Food Microbiol 144 (2010) 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dai T, Tanaka M, Huang YY, Hamblin MR, Chitosan preparations for wounds and burns: anti-microbial and wound-healing effects, Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther 9 (2011) 857–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ueno H, Yamada H, Tanaka I, Kaba N, Matsuura M, Okumura M, Kadosawa T, Fujinaga T, Accelerating effects of chitosan for healing at early phase of experimental open wound in dogs, Biomaterials 20 (1999) 1407–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mizuno K, Yamamura K, Yano K, Osada T, Saeki S, Takimoto N, Sakurai T, Nimura Y, Effect of chitosan film containing basic fibroblast growth factor on wound healing in genetically diabetic mice, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 64 (2003) 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yazawa H, Murakami T, Li HM, Back T, Kurosaka K, Suzuki Y, Shorts L, Akiyama Y, Maruyama K, Parsoneault E, Wiltrout RH, Watanabe M, Hydrodynamics-based gene delivery of naked DNA encoding fetal liver kinase-1 gene effectively suppresses the growth of pre-existing tumors, Cancer Gene Ther. 13 (2006) 993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Niidome T, Huang L, Gene therapy progress and prospects: nonviral vectors, Gene Ther. 9 (2002) 1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Leong KW, Mao HQ, Truong-Le VL, Roy K, Walsh SM, August JT, DNA-polycation nanospheres as non-viral gene delivery vehicles, J. Control. Release 53 (1998) 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chandler LA, Gu DL, Ma C, Gonzalez AM, Doukas J, Nguyen T, Pierce GF, Phillips ML, Matrix-enabled gene transfer for cutaneous wound repair, Wound Repair Regen. 8 (2000) 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].DeCarlo AA, Belousova M, Ellis AL, Petersen D, Grenett H, Hardigan P, O'Grady R, Lord M, Whitelock JM, Perlecan domain 1 recombinant proteoglycan augments BMP-2 activity and osteogenesis, BMC Biotechnol. 12 (2012) 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Greenhalgh DG, Sprugel KH, Murray MJ, Ross R, PDGF and FGF stimulate wound healing in the genetically diabetic mouse, Am. J. Pathol 136 (1990) 1235–1246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bolukbasi N, Balcioglu HA, Ozkan BT, Tekkesin MS, Ustek D, Topical single-dose vascular endothelial growth factor has no effect on soft tissue healing, North Am. J. Med. Sci 6 (2014) 505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Martinez-Santamaria L, Conti CJ, Llames S, Garcia E, Retamosa L, Holguin A, Illera N, Duarte B, Camblor L, Llaneza JM, Jorcano JL, Larcher F, Meana A, Escamez MJ, Del Rio M, The regenerative potential of fibroblasts in a new diabetes-induced delayed humanised wound healing model, Exp. Dermatol 22 (2013) 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tsurumi Y, Takeshita S, Chen D, Kearney M, Rossow ST, Passeri J, Horowitz JR, Symes JF, Isner JM, Direct intramuscular gene transfer of naked DNA encoding vascular endothelial growth factor augments collateral development and tissue perfusion, Circulation 94 (1996) 3281–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Huang YC, Kaigler D, Rice KG, Krebsbach PH, Mooney DJ, Combined angiogenic and osteogenic factor delivery enhances bone marrow stromal cell-driven bone regeneration, J. Bone Miner. Res 20 (2005) 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Maruyama K, Asai J, Ii M, Thorne T, Losordo DW, D'Amore PA, Decreased macrophage number and activation lead to reduced lymphatic vessel formation and contribute to impaired diabetic wound healing, Am. J. Pathol 170 (2007) 1178–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Fieguth A, Kleemann WJ, Troger HD, Immunohistochemical examination of skin wounds with antibodies against alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, alpha-2-macroglobulin and lysozyme, Int. J. Legal Med 107 (1994) 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lim SM, Song DK, Oh SH, Lee-Yoon DS, Bae EH, Lee JH, In vitro and in vivo degradation behavior of acetylated chitosan porous beads, J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed 19 (2008) 453–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Curtin CM, Tierney EG, McSorley K, Cryan SA, Duffy GP, O'Brien FJ, Combinatorial gene therapy accelerates bone regeneration: non-viral dual delivery of VEGF and BMP2 in a collagen-nanohydroxyapatite scaffold, Adv. Healthc. Mater 4 (2015) 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Peng L-H, Wei W, Qi X-T, Shan Y-H, Zhang F-J, Chen X, Zhu Q-Y, Yu L, Liang W-Q, Gao J-Q, Epidermal stem cells manipulated by pDNA-VEGF165/CYD-PEI nanoparticles loaded gelatin/μ-TCP matrix as a therapeutic agent and gene delivery vehicle for wound healing, Mol. Pharm 10 (2013) 3090–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lord MS, Chuang CY, Melrose J, Davies MJ, Iozzo RV, Whitelock JM, The role of vascular derived perlecans in modulating cell adhesion, proliferation and growth factor signaling, Matrix Biol 35 (2014) 112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]