Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the mortality and utilization outcomes of short-stay intensive care unit (ICU) patients who require <24 h of critical care. We aimed to define characteristics and outcomes of short-stay ICU patients whose need for ICU level-of-care is ≤24 h compared to nonshort-stay patients.

Methods:

Single-center retrospective cohort study of patients admitted to the medical ICU at an academic tertiary care center in 2019. Fisher's exact test or Chi-square for descriptive categorical variables, t-test for continuous variables, and Mann–Whitney two-sample test for length of stay (LOS) outcomes.

Results:

Of 819 patients, 206 (25.2%) were short-stay compared to 613 (74.8%) nonshort-stay. The severity of illness as measured by the Mortality Probability Model-III was significantly lower among short-stay compared to nonshort-stay patients (P = 0.0001). Most short-stay patients were admitted for hemodynamic monitoring not requiring vasoactive medications (77, 37.4%). Thirty-six (17.5%) of the short-stay cohort met Society of Critical Care Medicine's guidelines for ICU admission. Nonfull-ICU LOS, or time spent waiting for transfer out to a non-ICU bed, was similar between the two groups. Hospital mortality was lower among short-stay patients compared to nonshort-stay patients (P = 0.01).

Conclusions:

Despite their lower illness severity and fewer ICU-level care needs, short-stay patients spend an equally substantial amount of time occupying an ICU bed while waiting for a floor bed as nonshort-stay patients. Further investigation into the factors influencing ICU triage of these subacute patients and contributors to system inefficiencies prohibiting their timely transfer may improve ICU resource allocation, hospital throughput, and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Intensive care units, length of stay, resource allocation

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate allocation of hospital resources has been an area of concern for decades.[1] This is particularly true of the intensive care unit (ICU) where critical care is an expensive and limited resource.[2] Unnecessary ICU admissions may lead to longer wait times for those in need of critical care.[1] There was a reported 32% increase in emergency department (ED) length of stay (LOS) for critically ill patients between 2001 and 2009, indicating that these beds are in short supply.[3] In many hospitals, including large academic centers, the request for ICU beds surpasses availability, raising questions about the appropriateness of critical care admission for specific patient groups.[3]

One patient group of interest is “short-stay” ICU admissions, which can be variably defined as an ICU stay ranging anywhere from <24 h[4,5] to up to 2 days.[1] In their single-site investigation, Mathews et al., found that 37% of ICU admissions from the ED were put in for transfer within 24 h. One-third of these patients did not meet the Society of Critical Care Medicine's (SCCM) guidelines for ICU admission or receive ICU-level interventions.[6] Thus, short-stay admissions, whose severity of illness and care needs are less critical, may be consuming resources that would be better dedicated to higher acuity patients requiring more intensive care.

In light of limited data on this short-stay population, we aimed to define the characteristics of medical ICU patients whose need for ICU level-of-care was ≤24 h and examine their outcomes compared to nonshort-stay patients whose need for ICU level-of-care was in excess of 24 h. We hypothesized that short-stay admissions, despite their lower acuity care needs, would contribute significantly to ICU bed utilization.

METHODS

Study design and setting

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study of patients admitted to two medical ICUs at our academic tertiary care, urban medical center over a 12-month period from January to December 2019. At our institution, there are 25 beds available to patients with medical critical illness, which are divided into a smaller 8-bed unit and a larger 17-bed unit. Patient care in both units is directed by board-certified intensivists under a high-intensity (closed unit) staffing model with equivalent physician-to-patient staffing ratios.[7] The nursing staff is shared between the two units, also with similar nurse-to-patient staffing ratios. Care capacity such as the ability to manage central or arterial lines, hourly vital signs, and frequent neurologic examinations are standardized between the two ICUs, as are care protocols for sepsis resuscitation, progressive mobility, and weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Patients and variables

We chart abstracted patient-level clinical variables outlined in the mortality probability model (MPM0-III) for risk adjustment.[8] Variables as defined in the MPM include three physiologic variables within 1 h of admission, five acute and three chronic diagnoses, age, cardiopulmonary resuscitation within 24 h of admission, mechanical ventilation within 1 h of admission, medical or unscheduled surgical admission, and variables adjusting for “zero factor” (i.e., no risk factors other than age) and full code status.[8,9] We also collected information on care sites immediately prior to ICU admission and hospital discharge disposition.

Among medical intensive care unit (MICU) admissions, we divided patients into two cohorts defined as short-stay (≤24 h) and nonshort-stay (>24 h) based on the duration of time spent in the ICU during which time ICU level-of-care was warranted (i.e., excluding time spent waiting for a bed). We excluded patients admitted from non-ED or nonfloor sources. We further excluded nonindex ICU admissions and nonsurvivors of their ICU stay. Medical ICU discharges to other ICUs or other hospitals and departures against medical advice were also excluded from analyses. ICU admission diagnoses were categorized by body system.[10] For short-stay patients, we collected elements of the Simplified Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System (TISS-28,) which has the highest possible score of 88 points, as a measure of nursing workload.[11]

The primary outcome of interest was nonfull ICU LOS, defined as time spent in the ICU at nonfull ICU level of care (i.e., time spent waiting for transfer out of the ICU). Other utilization outcomes included pre-ICU LOS, defined as the duration of hospitalization prior to ICU admission, and ICU LOS, defined as the entire duration of time physically spent in the ICU. Secondary endpoints included hospital LOS and hospital discharge disposition, including death. All data were collected and managed using a secure web-based software platform, research electronic data capture, hosted at Thomas Jefferson University and accessible only to key study personnel.[12,13] This project was approved by Thomas Jefferson University's office of human research institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent (#20E.293).

Statistical analysis

To compare patient characteristics between the short-stay and nonshort-stay groups, we performed standard descriptive statistics using Fisher's exact test or Chi-square for categorical variables, and t-test for continuous variables, as appropriate. We compared nonnormally distributed LOS outcomes using the Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney two-sample) test. All analyses were performed using Stata 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, United States).[14] An α < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This project was approved by Thomas Jefferson University's Office of Human Research Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent (#20E.293).

RESULTS

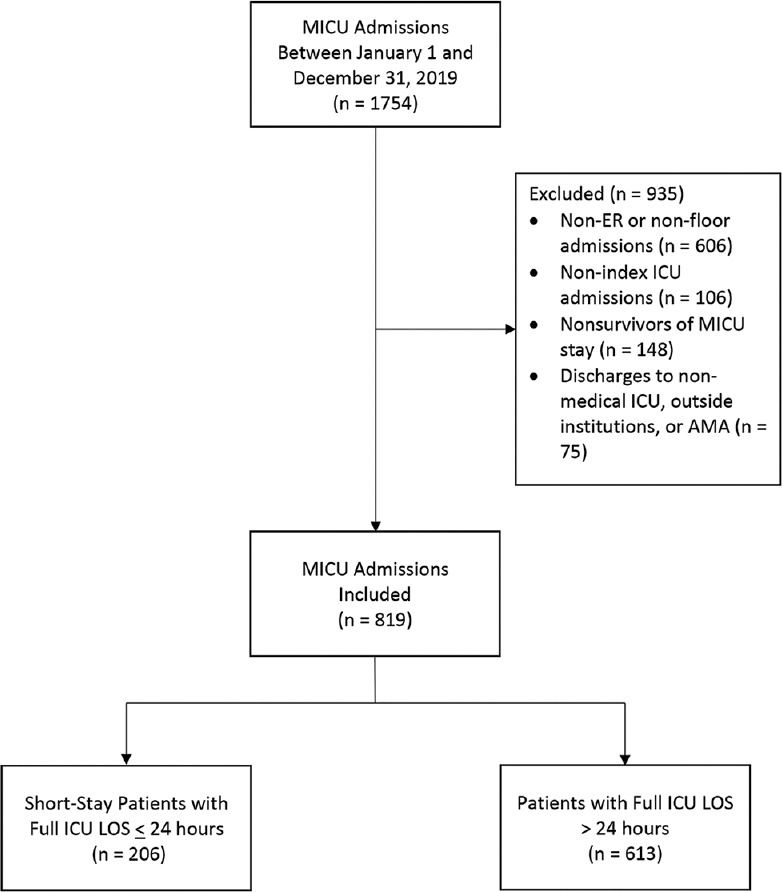

We identified 1754 MICU admissions over the 12-month time period of interest. After exclusions, there were 819 patients in our cohort: 206 short-stay patients (25.2%) and 613 nonshort-stay patients [74.8%; Figure 1]. Demographic and ICU admission characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1. Short-stay patients were younger and were more likely to originate from the ED. Short-stay patients also had a lower incidence of acute kidney injury. Accordingly, the severity of illness as measured by the MPM0-III was significantly lower among short-stay patients compared to nonshort-stay patients (13.7% ± 15.6% vs. 19.0% ± 17.3%; P = 0.0001, respectively).

Figure 1.

Patient selection

Table 1.

Demographic and intensive care unit admission characteristics*

| Short-stay (≤24 h) | Non-short-stay (>24 h) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 206 | 613 | NA |

| Female | 93 (45.1) | 290 (47.3) | 0.59 |

| Age (year) | 58.2±17.9 | 61.2±16.9 | 0.03 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7±8.2 | 28.1±8.9 | 0.52 |

| Race | |||

| White | 91 (44.2) | 282 (46.0) | 0.72 |

| Black | 79 (38.4) | 243 (39.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific-Islander | 14 (6.8) | 42 (6.9) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17 (8.3) | 36 (5.9) | |

| Unknown | 5 (2.4) | 10 (1.6) | |

| Triage location | |||

| Emergency department | 160 (77.7) | 392 (67.4) | <0.001 |

| Floor | 46 (22.3) | 221 (36.1) | |

| Surgery prior to ICU admission | 3 (1.5) | 22 (3.6) | 0.16 |

| Chronic diagnoses** | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 36 (17.5) | 89 (14.5) | 0.31 |

| Cirrhosis | 8 (3.9) | 42 (6.9) | 0.12 |

| Metastatic neoplasm | 30 (14.6) | 107 (17.5) | 0.34 |

| Acute diagnoses** | |||

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 17 (8.3) | 65 (10.6) | 0.33 |

| Acute kidney injury | 13 (6.3) | 69 (11.3) | 0.04 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 19 (9.2) | 76 (12.4) | 0.22 |

| Full code status | 188 (91.3) | 561 (91.5) | 0.91 |

| MPM0III, % | 13.7±15.6 | 19.0±17.3 | 0.0001 |

*Values given as mean±SD or n (%), unless otherwise indicated, **Acute and chronic diagnoses as defined in the MPM. SD: Standard deviation, ICU: Intensive care unit, MPM: Mortality probability model

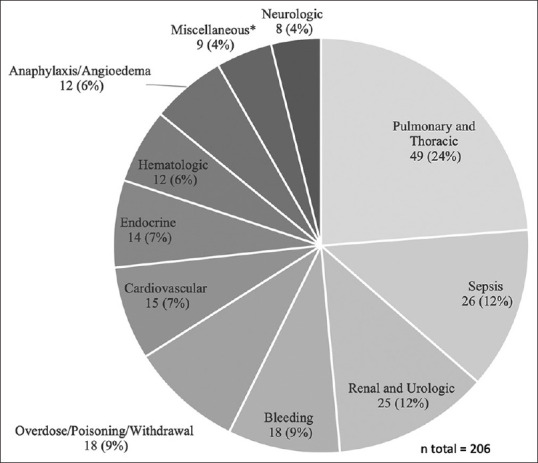

ICU admission diagnoses for short-stay patients categorized by organ system are depicted in Figure 2. Admission diagnoses were most commonly categorized as pulmonary and thoracic (24%) followed by sepsis (12%) and renal and urologic (12%). The mean TISS-28 as a measure of nursing workload for the 206 short-stay patients was 15.63 (±4.23). The majority of short-stay patients (77, 37.4%) were admitted to the ICU with hemodynamic concerns that ultimately did not require initiation of vasoactive medications. ICU interventions by category of admission diagnosis are further presented in Table 2. A minority of short-stay patients required high-intensity ICU interventions such as invasive mechanical ventilation (12, 5.8%) or vasopressor support (15, 7.3%.) Only 17.5% of the short-stay cohort met SCCM guidelines for ICU admission.[15]

Figure 2.

Diagnostic categories of intensive care unit admission for short-stay patients, n (%) *Miscellaneous: Antibiotic desensitization (3), hypothermia (2), perforated viscus (2), hyperthermia, ileus

Table 2.

Intensive care unit-level interventions by category of admitting diagnosis

| Admission diagnostic category | ICU intervention | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary and thoracic (n=49) | Noninvasive respiratory support* | 34 (69) |

| Hemodynamic monitoring | 10 (20) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (6) | |

| Emergent dialysis | 1 (2) | |

| Infusion of vasoactive medication | 1 (2) | |

| Sepsis (n=26) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 17 (65) |

| Infusion of vasoactive medication | 6 (23) | |

| Active rewarming | 1 (4) | |

| Noninvasive respiratory support | 1 (4) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (4) | |

| Renal and urologic (n=25) | Monitored metabolic correction** | 9 (36) |

| Emergent dialysis | 9 (36) | |

| Hemodynamic monitoring | 4 (16) | |

| Infusion of vasoactive medication | 2 (8) | |

| Noninvasive respiratory support | 1 (4) | |

| Bleeding (n=18) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 17 (94) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (6) | |

| Overdose/poisoning/withdrawal (n=18) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 10 (56) |

| Naloxone infusion | 4 (22) | |

| Infusion of vasoactive medication | 2 (11) | |

| Emergent dialysis | 1 (6) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (6) | |

| Cardiovascular (n=15) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 6 (40) |

| Infusion of vasoactive medication | 6 (40) | |

| Airway monitoring | 1 (7) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (7) | |

| Transcutaneous pacing | 1 (7) | |

| Endocrine (n=14) | Monitored metabolic correction | 13 (93) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (7) | |

| Anaphylaxis/angioedema (n=12) | Airway monitoring | 12 (100) |

| Hematologic (n=12) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 7 (58) |

| Plasma exchange/plasmapheresis | 3 (25) | |

| Emergent dialysis | 1 (8) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (8) | |

| Miscellaneous (n=9) | Desensitization | 3 (33) |

| Hemodynamic monitoring | 3 (33) | |

| Active rewarming | 2 (22) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (11) | |

| Neurologic (n=8) | Hemodynamic monitoring | 3 (38) |

| Active rewarming | 2 (25) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2 (25) | |

| Noninvasive respiratory support | 1 (13) |

*Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, high-flow nasal cannula, nonrebreather mask, and mid-flow nasal cannula (7-15 l per minute of oxygen), **Hyponatremia, severe hyperkalemia not requiring dialysis, hypoglycemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis. ICU: Intensive care unit

Utilization outcomes are presented in Table 3. Pre-ICU LOS, total ICU LOS, and hospital LOS were significantly longer among nonshort-stay patients. However, nonfull-ICU LOS was similar between the two groups [Table 3]. Overall, 16 (7.8%) of the short-stay patients also had a hospital LOS of < 24 h (i.e., the short ICU stay comprised most or all of the entire hospital stay). The maximum nonfull-ICU LOS was 184 h among short-stay patients and 292 h among nonshort-stay patients.

Table 3.

Utilization outcomes

| Short-stay (n=206) |

Non-short-stay (n=613) |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Mean±SD | Median (IQR) | Mean±SD | ||

| Pre-ICU LOS, h | 6.55 (3.93-12.20) | 27.87 (92.08) | 8.53 (4.67-33.0) | 42.78 (91.83) | 0.0006 |

| ICU LOS, h | 30.00 (20.27-45.65) | 36.40 (23.69) | 83.77 (55.65-137.62) | 120.83 (111.04) | <0.0001 |

| Nonfull ICU LOS, h | 11.40 (4.88-31.08) | 21.51 (24.29) | 13.28 (5.52-33.25) | 25.67 (31.97) | 0.23 |

| Hospital LOS, h | 108.24 (55.75-192.73) | 157.77 (163.79) | 221.90 (123.12-412.32) | 329.62 (702.37) | <0.0001 |

IQR: Interquartile range, SD: Standard deviation, LOS: Length of stay, ICU: Intensive care unit

Discharge disposition and mortality outcomes are presented in Table 4. Among survivors to hospital discharge, short-stay patients were more commonly discharged to home, whereas nonshort-stay patients were more likely to be discharged to facilities such as long-term acute care, skilled nursing, or acute rehabilitation. Hospital mortality was lower among short-stay patients compared to nonshort-stay patients (0.97% vs. 4.9%; P = 0.01, respectively).

Table 4.

Discharge outcomes

| Discharge disposition* | Short-stay (n=206) | Nonshort-stay (n=613) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 152 (74.5) | 321 (55.1) | <0.0001 |

| Hospice (home or facility) | 12 (5.9) | 56 (9.6) | |

| Long-term acute care | 2 (0.98) | 15 (2.6) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 20 (9.8) | 117 (20.1) | |

| Acute rehabilitation | 5 (2.5) | 44 (7.6) | |

| AMA or elopement | 8 (3.9) | 14 (2.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 5 (2.5) | 16 (2.7) | |

| Hospital mortality** | 2 (0.97) | 30 (4.9) | 0.01 |

*Denominator for % includes only survivors to hospital discharge, **Excludes non-survivors of ICU stay. AMA: Against medical advice

DISCUSSION

In our single-center retrospective study, we found that short-stay patients whose need for ICU level-of-care was ≤24 h were younger and had lower MPM0-III predicted risk of hospital death. Their burden on nursing workload measured by a mean TISS-28 score of 15.63 (±4.23), was similar to that seen in the literature for similar short-stay ICU patients.[16] This value was also lower than the mean of 29.82 (±10.64) reported in the original ICU validation study for the TISS-28 scoring system, suggesting that the generated nursing workload for these patients may not have warranted critical care.[17] The minority of short-stay admissions met SCCM guidelines for ICU admission. Despite having an expected shorter overall ICU and hospital LOS compared to their nonshort-stay counterparts, short-stay patients also had similar nonfull-ICU LOS, indicating that they occupied ICU beds for a similar amount of time as nonshort-stay patients while awaiting a floor bed. Even after being deemed ready for non-ICU-level care, short-stay patients contributed significantly to ICU bed utilization despite not necessarily having ICU-level care needs. In addition, short-stay patients were more likely to survive their hospital stay and also more likely to be discharged to home rather than to facilities.

Existing literature on the short-stay ICU patient is limited and outcomes assessment is further complicated by the lack of consensus definition on what constitutes a short ICU stay. Using the most frequently used definition of 1 day, previous studies have shown that short-stay ICU patients are common, and can comprise anywhere from 27.8% to 38% of all ICU admissions.[4,5,6] Concordant with our findings, Chidi et al. found that short-stay critical care admissions from the ED in Maryland were less likely to die in the hospital and less likely to be discharged to postacute care facilities, further confirming the low severity of illness exhibited by this population at the time of admission.[4]

However, our study uniquely showed that short-stay patients occupied ICU beds for a similar number of days as nonshort-stay patients while waiting for floor transfer, thereby equally contributing to unnecessary critical care bed utilization. In their single-center analysis of short-stay ICU patients, Mathews et al. reported that of a total median ICU LOS of 20.4 h, 31.6% of that time was spent waiting for a bed outside the ICU once the transfer decision had been made.[16] We found that of a total median ICU LOS of 30 h among short-stay patients, 38% was spent waiting for a floor bed. These observations have important implications for patient care, as when the ICU is full, clinicians' triage decisions would increasingly need to take into account bed availability in lieu of clinical data and acute presentation. Low ICU bed availability may result in the denial of patients who would have otherwise been accepted to the ICU.[18,19] Multiple studies have shown that the decision to deny admission to the ICU is associated with increased hospital mortality, highlighting the importance of maximizing the efficiency of ICU utilization and hospital throughput.[19,20,21]

There are several limitations to our study. First, the single-center data limit generalizability. Local factors, including the absence of a formal medical step-down (or intermediate care) unit, may not only impact ICU case-mix at admission but also influence the timing of decisions surrounding floor-readiness at our institution. In single-center studies, step-down units may decrease the number of low-risk monitor patients occupying ICU beds.[22,23,24,25] However, data regarding the impact of the availability of step-down unit care on patient outcomes is limited, and outcomes for medical patients admitted to step-down care as an alternative to full intensive care have not been well researched.[26] Second, in this study, we were unable to capture day-to-day variation in ICU and floor occupancy that would also affect patient throughput. Finally, we were also unable to characterize the fluctuating demand that affects the daily requirement for critical care beds.[27]

CONCLUSION

In summary, our study shows that short-stay patients who are deemed transfer-ready in ≤24 h spend a substantial amount of time occupying an ICU bed while waiting for a floor bed. Moreover, this duration of unnecessary ICU bed occupation while awaiting transfer is similar to that of nonshort-stay patients. In light of their lower mortality, lower burden of nursing care, and less frequent need for ICU-specific interventions compared to nonshort-stay patients, it is possible that ICU admission may not always be clinically warranted for this low-risk and low-labor short-stay population. Their triage into non-ICU settings may not only improve ICU bed availability but also have implications for cost containment, given that US critical care services consume 13.4% of total hospital costs.[28] Further investigation into the factors influencing triage of these subacute patients, their effect on the care of acute patients warranting ICU-level care, and contributors to system inefficiencies prohibiting their timely transfer may improve ICU resource allocation, hospital throughput, and patient outcomes.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Thomas Jefferson University's Office of Human Research Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent (Approval # 20E.293; Approval date December 23, 2020). The authors followed the applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network. org/) guidelines, specifically the STROBE Guidelines, during the conduct of this research project.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sedaghat Siyahkal M, Khatami F. Short stay in general intensive care units: Is it always necessary? Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giannini A, Consonni D. Physicians' perceptions and attitudes regarding inappropriate admissions and resource allocation in the intensive care setting. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:57–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews KS, Long EF. A conceptual framework for improving critical care patient flow and bed use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:886–94. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-419OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chidi OO, Perman SM, Ginde AA. Characteristics of short-stay critical care admissions from emergency departments in Maryland. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1204–11. doi: 10.1111/acem.13188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arabi Y, Venkatesh S, Haddad S, Al Malik S, Al Shimemeri A. The characteristics of very short stay ICU admissions and implications for optimizing ICU resource utilization: The Saudi experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:149–55. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews K, Jenq G, Siner J, Long E, Pisani M. 156. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1–328. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: A systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288:2151–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins TL, Teres D, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Stark M, Kramer AA. Assessing contemporary intensive care unit outcome: An updated Mortality Probability Admission Model (MPM0-III) Crit Care Med. 2007;35:827–35. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000257337.63529.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemeshow S, Teres D, Klar J, Avrunin JS, Gehlbach SH, Rapoport J. Mortality Probability Models (MPM II) based on an international cohort of intensive care unit patients. JAMA. 1993;270:2478–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: Hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–310. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miranda DR, de Rijk A, Schaufeli W. Simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system: The TISS-28 items – Results from a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:64–73. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, Blosser S, Goldner J, Birriel B, et al. ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines: A framework to enhance clinical operations, development of institutional policies, and further research. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1553–602. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews KS, Jenq GY, Siner JM, Long EF, Pisani MA. “Short-Stay” patients in the intensive care unit: Characterizing patient acuity, throughput, and critical care resource utilization A39. Improving Quality in the Intensive Care Unit. American Thoracic Society International Conference in San Francisco, CA. 2012:A6731. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno R, Morais P. Validation of the simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system on an independent database. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:640–4. doi: 10.1007/s001340050387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stelfox HT, Hemmelgarn BR, Bagshaw SM, Gao S, Doig CJ, Nijssen-Jordan C, et al. Intensive care unit bed availability and outcomes for hospitalized patients with sudden clinical deterioration. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:467–74. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert R, Coudroy R, Ragot S, Lesieur O, Runge I, Souday V, et al. Influence of ICU-bed availability on ICU admission decisions. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:55. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinuff T, Kahnamoui K, Cook DJ, Luce JM, Levy MM. Values Ethics and Rationing in Critical Care Task Force Rationing critical care beds: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1588–97. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000130175.38521.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truog RD, Brock DW, Cook DJ, Danis M, Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Rationing in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:958–63. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206116.10417.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox AJ, Owen-Smith O, Spiers P. The immediate impact of opening an adult high dependency unit on intensive care unit occupancy. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:280–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pappachan JV, Millar BW, Barrett DJ, Smith GB. Analysis of intensive care populations to select possible candidates for high dependency care. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:13–7. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrick RJ, Power JD, Ycas JO, Brown KA. Impact of an intermediate care area on ICU utilization after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:869–72. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin CM, Rackow EC, Mamdani B, Nightingale S, Burke G, Weil MH. Decreases in mortality on a large urban medical service by facilitating access to critical care. An alternative to rationing. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1403–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prin M, Wunsch H. The role of stepdown beds in hospital care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1210–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1117PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyons RA, Wareham K, Hutchings HA, Major E, Ferguson B. Population requirement for adult critical-care beds: A prospective quantitative and qualitative study. Lancet. 2000;355:595–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)01265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang DW, Shapiro MF. Association between intensive care unit utilization during hospitalization and costs, use of invasive procedures, and mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1492–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]