Abstract

The ospE gene family of the Lyme disease spirochetes encodes a polymorphic group of immunogenic lipoproteins. The ospE genes are one of several gene families that are flanked by a highly conserved upstream sequence called the upstream homology box, or UHB, element. Earlier analyses in our lab demonstrated that ospE-related genes are characterized by defined hypervariable domains (domains 1 and 2) that are predicted to be hydrophilic, surface exposed, and antigenic. The flanking of hypervariable domain 1 by DNA repeats may indicate that recombination contributes to ospE diversity and thus ultimately to antigenic variation. Using an isogeneic clone of Borrelia burgdorferi B31G (designated B31Gc1), we demonstrate that the ospE-related genes undergo mutation and rearrangement during infection in mice. The mutations that develop during infection resulted in the generation of OspE proteins with altered antigenic characteristics. The data support the hypothesized role of OspE-related proteins in immune system evasion.

Lyme disease is a tick-transmitted disease caused by spirochetes of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex. It is a multisystem disorder with musculoskeletal, cardiac, and neurological manifestations. If untreated, infection with pathogenic species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex can be chronic, with the infection persisting for several years (3, 17). This suggests that the Lyme disease spirochetes are able to avoid destruction by the immune response. The closely related relapsing fever Borrelia spp. possess a well-characterized antigenic variation system that allows for immune response evasion (4). These bacteria differentially express dominant antigens belonging to the Vmp protein family. The differential expression of these genes, which results from gene conversion events (19, 20), allows for the persistence of the bacterial population with the subsequent occurrence of several spirochetemias before the infection is ultimately cleared. In contrast to relapsing fever, cyclic fever episodes and spirochetemias are not observed during infection with the Lyme disease spirochetes. Hence, while antigenic variation may play a role in the maintenance of chronic infection, it does not manifest itself in a pronounced manner analogous to that seen in relapsing fever.

Norris and colleagues have recently demonstrated that antigenic variants of the B. burgdorferi Vls protein family arise during infection in mice (29). The generation of new antigenic variants is thought to occur through the exchange of DNA cassettes. However, since the Vls proteins do not appear to be dominant antigens and since the antigenic changes are subtle, immune response evasion by the Lyme disease spirochetes is likely to be multifactorial and not likely attributable to a single gene family. The Lyme disease spirochetes carry in excess of 120 different lipoprotein or outer surface protein genes, most of which belong to one of the 175 plasmid-carried gene families harbored by these bacteria. Hence, the potential for sequence exchange via homologous recombination is enormous. Molecular changes in genes encoding surface-exposed antigens could collectively provide sufficient antigenic diversity to allow for the persistence of chronic infection.

Several families of plasmid-encoded lipoprotein genes are 5′ flanked by a highly conserved sequence that we previously designated the upstream homology box, or UHB, element (2, 16, 26). The UHB-flanked genes encode highly polymorphic lipoproteins (1, 2, 6, 7, 13, 16, 22, 24, 25, 27). The polymorphic nature of the proteins encoded by the UHB-flanked genes has prompted suggestions that they may contribute to immune response evasion (16, 23, 26). Sequence analyses of ospE gene family members from a variety of strains revealed that defined hypervariable regions exist which are predicted by computer analyses to be hydrophilic, antigenic, and surface exposed (26). The extensive variation characterized in this domain in isolates recovered from ticks and mammals indicates that this domain is not evolutionarily stable and that its organization and sequence have been influenced by recent molecular events. It has been hypothesized that rearrangements or mutations in this domain could lead to the generation of new OspE antigenic variants (16, 26). Recent studies by us and others indicate that gene rearrangement events and gene fusions have occurred among UHB-flanked genes (2, 16, 23) as well as in members of the mlp gene family (6, 28). However, the environment(s) in which these rearrangements occur has not been defined. The goals of this study were to determine if rearrangements or mutations in the ospE gene family arose during infection and, if so, whether these changes influence the antigenic properties of the OspE proteins. In summary, the analyses presented here provide direct evidence that mutations and gene rearrangements occur in the ospE-related genes during infection and that these changes lead to the development of OspE variants with altered antigenicity. Collectively, the data indicate that immune response evasion is a multifactorial process and that the ospE gene family is a contributor to this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates, cultivation, and experimental infection of mice.

B. burgdorferi B31G was used for these analyses since the entire genome sequence has been determined for this isolate (10). The same clone used in the genome sequence analysis was kindly provided for us by MedImmune Inc. (Gaithersburg, Md.). Prior to initiation of these studies, the infectivity of B. burgdorferi B31G was confirmed as follows. B. burgdorferi B31G (∼500 spirochetes) was cultivated in complete BSK-H medium (Sigma) and then needle injected (intradermally) between the shoulder blades of C3H/HeJ mice. At 2 weeks postinoculation, 1-mm2 ear punch biopsy specimens were obtained and placed into liquid BSK-H medium containing antibiotics (phosphomycin, 20 μg ml−1; amphotericin B, 2.5 μg ml−1; rifampin, 50 μg ml−1; Sigma). When spirochetes became visible in the medium as assessed by dark-field microscopy, the cultures were subsurface plated in semisolid complete BSK-H medium to obtain infectious isogeneic clones. Subsurface plating was performed as follows. Complete BSK-H medium (45°C) was mixed with a 2% GTG-agarose solution (55°C) (FMC) (final agarose concentration, 0.7%), poured into petri dishes, and allowed to solidify to form a bottom layer. Mid-log-phase B. burgdorferi B31G, grown in complete BSK-H medium, was serially diluted (10−2, 10−4, or 10−6), mixed with a warmed complete BSK-H–0.7% GTG-agarose solution (45°C), and poured into petri dishes to form the top layer. The plates were incubated at 33°C under 3.2% CO2 in a humidified CO2 incubator. Approximately 2 to 3 weeks later, individual colonies were cored from the plates using a sterile Pasteur pipette. The colony-containing plugs of agarose were inoculated into 2 ml of complete BSK-H medium and cultivated at 33°C. The B. burgdorferi B31G clone, B31Gc1, was selected for further analysis. To obtain postinfection isogeneic clones, B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 was used to infect C3H/HeJ mice for a period of 3 months as described above. Spirochetes were cultivated from ear punch biopsies and subsurface plated, and well-isolated colonies were picked by coring of the colonies from the medium and transferred into complete BSK-H medium. Aliquots of these cultures were prepared for immunoblot analyses or for use as PCR template as described below.

Southern hybridization analyses.

DNA was isolated from B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 as previously described (14) and digested with HaeIII as instructed by the supplier (New England Biolabs). The digested DNA was fractionated in 0.8% GTG-agarose gels using standard Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. The DNA was transferred onto Hybond-N membranes by vacuum blotting using the VacuGene system as described by the manufacturer (Pharmacia). Oligonucleotide probes were end labeled at their 5′-OH groups using polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol; NEN-Du Pont). Hybridizations were conducted using conditions and buffers previously described (15) in a Hybaid hybridization oven.

PCR analysis of the UHB-flanked genes in isogeneic B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clones.

To PCR amplify the ospE alleles of B. burgdorferi B31Gc1, isolated genomic DNA (∼50 ng) was used as template with either the uhb(+)-E470(−) or uhb2(+)-E470(−) primer set. Primers and oligonucleotides used in this study are described in Table 1. PCR was performed with Taq polymerase (Promega) for 30 cycles in an MJ Research PTC-100 thermal cycler. Reaction volumes were 30 μl, and final primer set concentrations were 1 pmol of primer pair per μl. Cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C. The resulting amplicons were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide probes and PCR primers

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Target site |

|---|---|---|

| uhb(+) | GTTGGTTAAAATTACATTTGCG | UHB element of plasmids L, P, and S (one mismatch in plasmids L and P) |

| uhb2(+) | CTTTGAAATATTGCAATTAT | UHB element of plasmids R, N, and S; no significant complementarity with plasmids L and P |

| E13(+) | AAATGTTTATTATTTGTGCTGTT | 5′ end of ospE alleles on plasmids L and P; 5′ end of BBO39 (erpL-plasmid O) |

| E470(−) | CTAGTGATATTGCATATTCAG | 3′ region of the ospE alleles, BBL39, BBP38, and BBN38 (1 mismatch) |

| E310(−) | AAACTAGTTTTAAATGATCC | Central region of the ospE alleles BBL39, BBP38, and BBN38 |

| LIC-E46(+) | GACGACGACAAGATGCTTATAGGTGCTTGCAAG | 5′ end of the ospE alleles, BBN38, BBL39, and BBP38; underlined sequence complements the LIC vector |

| LIC-E470(−) | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTTATAGTGATATTGCATATTCAGC | 3′ region of the ospE alleles, BBL39, BBP38, and BBN38 (1 mismatch); has an introduced stop codon; underlined sequence complements the LIC vector |

When screening for ospE alleles in postinfection isogeneic populations, template DNA was obtained by collection of well-isolated B. burgdorferi colonies (derived from spirochete cultures recovered from ear punch biopsy specimens), transfer into 2 ml of complete BSK-H medium, and cultivation until mid-log phase. Then, 100-μl aliquots were removed, and cells were pelleted, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 100 μl of H2O. The cell suspension was boiled for 10 min and centrifuged to pellet debris, and 1 μl of the supernatant was used as template in PCR as described above. To analyze the resulting amplicons, 10 μl of each PCR mixture was electrophoresed in a 1.5% GTG-agarose gel using standard Tris-acetate-EDTA running buffer. In some cases, amplicons were further purified using the Wizard system (Promega).

Rapid screening for ospE mutations using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis.

ospE-related genes were amplified from isogeneic postinfection clones, using a variety of primer sets as described above. The purified amplicons obtained from these isogeneic clones then served as the template for SNP analyses. The SNP approach is essentially a sequencing approach, except that only one of the four dideoxynucleotide incorporation reactions is performed. This serves as a rapid means of screening for mutations prior to selection of templates for cloning and complete sequence analysis. To perform the SNP analyses, the Excel-Sequencing kit (Epicentre Technologies) and 5′-32P-end-labeled primers were used. The reaction mixtures were analyzed in 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels (17 by 40 cm; 0.4-mm thickness) followed by autoradiography. Amplicons with polymorphisms were selected for further analysis.

Cloning and sequence analysis of PCR amplicons.

Due to the presence of multiple ospE-related alleles in B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clones, some of the PCR templates analyzed in the SNP analyses represent a mixture of ospE amplicons. To analyze the polymorphic amplicons derived from individual ospE alleles, the amplicons were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector as described by the manufacturer (Promega). To identify Escherichia coli clones harboring ospE-carrying recombinant plasmids, the cells were plated onto Luria-Bertani plates (ampicillin, 50 μg ml−1), and individual colonies were picked with sterile toothpicks and resuspended in 100 μl of dH2O. The resuspended cells were boiled for 10 min, and 1 μl of the cell lysate was used as template in PCR with ospE-targeting PCR primer sets. Recombinant plasmids carrying ospE-related sequences were used as template in SNP analyses, and plasmids with polymorphic inserts were selected for complete sequence analysis of the inserts. Sequencing was accomplished using end-labeled primers and the Excel-Sequencing kit as described by the manufacturer (Epicentre Technologies). Sequencing reaction mixtures were run on 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels, and autoradiography was performed. The determined sequences were translated using the TRANSLATE program, and both the nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned using the PILEUP program and manually adjusted. PEPSTRUCTURE and PLOTSTRUCTURE were used to analyze the properties and structure of the deduced amino acid sequences. These programs are contained within the Wisconsin-GCG sequence analysis package.

Immunoblot procedures, ligase-independent cloning (LIC), and expression of OspE paralogs: analysis of the humoral immune response to OspE in experimentally infected mice.

The humoral immune response to OspE and OspE variants was assessed by immunoblotting. The test antigens for these analyses were generated by PCR, amplifying the desired gene from the appropriate B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone using ospE primers constructed with tail sequences that complement the single-stranded overhangs of the pT7Blue-2 LIC vector (Novagen). The sequences of the LIC-E46(+) and LIC-E470(−) primers are provided in Table 1. After PCR was performed, the single-stranded overhangs on the amplicon were generated by treatment with T4 DNA polymerase in the presence of dATP (other deoxynucleoside triphosphates are omitted) as described by the manufacturer (Novagen). To summarize, the 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity of the T4 DNA polymerase will digest the amplicon until it reaches the first A residue under the reaction conditions described above. The first A residue in the primers above corresponds to the first base of the start codon and the last base of the stop codon. When these bases are encountered by the DNA polymerase, the 5′-3′ polymerase activity counteracts its exonuclease activity, resulting in an amplicon with single-stranded overhangs that complement the vector. The treated amplicon and pT7Blue-2 LIC vector were then annealed and transformed into E. coli NovaBlue single competent cells (Novagen), using a standard transformation protocol, where covalent bond formation occurs and the plasmid is propagated. To identify colonies harboring the correct recombinant plasmid, colonies were selected, placed in 100 μl of H2O (after generating a master plate with all analyzed colonies), and boiled for 10 min, and then 1 μl was used as template in PCR with the E46(+)-E470(−) primer set. Select recombinants carrying the appropriate plasmid were inoculated into 3 ml of Luria-Bertani medium (ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1) and grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, and then protein expression was induced with 0.4 mm IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 3 h. The expressed protein represents an OspE fusion protein with 62 amino acids fused to its N terminus. The induced cells were pelleted, and cell lysates were analyzed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% polyacrylamide gel.

To conduct immunoblot analyses, the proteins were transferred from the gels onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by electroblotting using the Trans-Blot system (Bio-Rad). To assess the temporal pattern of the anti-OspE immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM response, strips of a blot containing cell lysates of E. coli expressing recombinant BBL39 were used as the antigenic substrate. To assess the IgG response to different OspE variants that arose during infection, blots of E. coli lysates expressing the different variants were used as the antigenic substrate. All immunoblots were blocked overnight in blocking buffer (1× PBS, 0.2% Tween, 0.002% NaCl, and 5% nonfat dry milk) and then incubated with either a 1:500 or 1:1,000 dilution (in blocking buffer) of anti-OspE antiserum or anti-B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 antiserum (mouse 1), respectively. Prior to use, antisera were preabsorbed with E. coli DH5α as follows. E. coli DH5α cells were boiled in PBS for 15 min, and then an aliquot of the cell lysate was incubated with the diluted antiserum (in blocking buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were added to the preabsorbed sera, incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and washed three times with wash buffer (1× PBS, 0.2% Tween, 0.002% NaCl). For analysis of IgG and IgM responses, ImmunoPure goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy plus light chains) peroxidase-conjugated or ImmunoPure goat anti-mouse IgM (μ-chain-specific) peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used, respectively. The secondary antibodies were incubated with the blots for 1 h at room temperature and then washed three times with wash buffer. For chemiluminescent detection, the Supersignal West Pico stable peroxide solution and the Supersignal West Pico Luminol-enhancer solution were used. Both reagents were from Pierce. The immunoblots were exposed to film.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database and have been assigned accession numbers AF223550 through AF223559.

RESULTS

Nomenclature of OspE paralogs and characterization of the parental B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 isogeneic clone prior to long-term infection in mice.

To simplify the following discussion pertaining to the OspE paralogs and to be able to differentiate between ospE alleles, the gene nomenclature assigned by The Institute of Genomic Research will be employed when referring to the individual ospE alleles that were identified by sequencing of the B. burgdorferi B31G genome (10). The three ospE-related alleles have been designated BBL39, BBN38, and BBP38. Note that the letter designation following BB indicates which plasmid carries the allele (i.e., plasmid L, N, or P) and that the number indicates its open reading frame assignment (relative to other open reading frames) on the plasmid. The ospE allele and plasmid designations used in this report are described in detail at www.tigr.org. The new ospE variants identified in this report are designated as follows. The ospE gene designation is utilized and is followed by a subscript indicating the postinfection B. burgdorferi clone of origin. The variants identified from individual isogeneic populations are indicated by sequential numbering. For example, the first ospE variant gene identified in B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53 is designated ospEc53-1. This nomenclature scheme is in accordance with that recommended by Demerec (9) and Reeves et al. (18) and is thus in accordance with American Society for Microbiology guidelines.

To be able to determine if polymorphisms develop in the ospE subfamily during infection, we first needed to confirm the presence and sequence of the ospE alleles carried by the parental B31Gc1 clone. To analyze BBN38, PCR analyses of the parental clone (B31Gc1) were performed using the uhb2(+)-E470(−) primer set. The uhb2(+) primer is specific for a sequence upstream of BBN38. Sequence analysis of the amplicon confirmed that it was identical to the published sequence for BBN38 (10). Since BBL39 and BBP38 are identical in sequence, they could not be individually amplified. However, sequence analysis of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicon, which could be derived from either BBL39 or BBP38 or both, revealed it to be identical to BBL39 and BBP38, indicating that at least one of these alleles was present. To determine if both BBL39 and BBP38 were present and to verify that large-scale recombination events did not occur around the ospE alleles in the parental strain prior to infection in mice, DNA from B31Gc1 was digested with HaeIII and hybridization analyses were conducted using the uhb(+) oligonucleotide probe and various probes that target the ospE alleles (data not shown). Five restriction fragments hybridized with the uhb(+) probe. Using the published genome sequence, restriction maps were generated for each of the cp32's that carries an ospE-related gene. With these maps, it could be determined if the sizes of the uhb(+)-hybridizing fragments in B31Gc1 were the same as those predicted by the restriction maps of the B31G population used in the genome sequence analysis. Conservation of restriction fragment size would indicate that plasmid rearrangements in and around the ospE alleles have not occurred. A fragment of 3,519 kb hybridized with the uhb2(+), uhb(+), E470(−), and BBN38(+) oligonucleotides. The size of this fragment is consistent with that predicted for the BBN38-carrying HaeIII fragment. The restriction maps for plasmids P and L predict comigrating, UHB-carrying, HaeIII restriction fragments of 2,048 bp. Consistent with the occurrence of comigrating restriction fragments, an intense hybridization signal was associated with the 2,048-bp restriction fragment with both the E470(−) and uhb(+) probes. From these analyses, it can be concluded that the clone selected for the analysis of ospE stability during infection carried BBN38, BBL39, and BBP38 and that the sequence of these genes in B31Gc1 is identical to that of the B31G clone used in the genome sequence analyses (10).

SNP analysis of ospE-related genes in isogeneic clones recovered from infected mice.

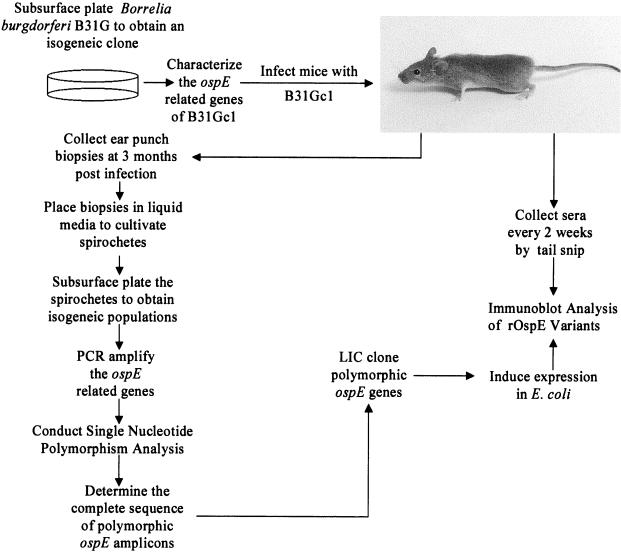

To determine if polymorphisms develop over the course of infection, C3H/HeJ mice were infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1. Figure 1 presents a flow chart for these analyses. Infection was confirmed by the successful cultivation of spirochetes from ear punch biopsy specimens at 4 weeks postinoculation. After 3 months of infection, spirochetes were again cultivated from an ear punch biopsy specimen and subsurface plated to yield isogeneic clones. To screen for sequence polymorphisms in the ospE alleles in the postinfection clones, an approach that we refer to as SNP analysis was employed. First, the ospE alleles were amplified from the postinfection clones using either the uhb2(+)-E470(−) or the uhb(+)-E470(−) primer set. These amplicons were then utilized as templates in the SNP analyses. As described above, SNP is essentially a limited sequence analysis using the dideoxy method in which only one of the four termination reactions is performed. Comparative analyses of the ladders generated allows one to scan large numbers of templates for polymorphisms. ddATP was chosen as the dideoxynucleoside triphosphate for these analyses because of the high A-T content of the B. burgdorferi genome, and while it is possible that some polymorphisms could be missed by this approach, the approach serves as a convenient starting point. The first round of SNP analyses revealed that 63% (35 of 56) of the isogeneic clones exhibited polymorphic patterns (i.e., polymorphisms in the ddATP sequencing ladder relative to the parental clone). It is important to note that more than one clone was found to exhibit each of the polymorphic patterns and that the SNP patterns were not unique to a single amplicon. This is important because it demonstrates that the polymorphisms did not arise as PCR artifacts. The generation of PCR artifacts would be random, and thus, the probability of detecting the same patterns in multiple clones would be extremely low. In addition, analyses of the UHB-flanked ospG gene from 30 different clones (described in detail below) did not reveal polymorphisms, indicating that the conditions employed in these analyses do not affect amplification or sequencing fidelity.

FIG. 1.

Flow chart depicting the approach used to assess the development of ospE polymorphisms and OspE antigenic variants during infection in mice.

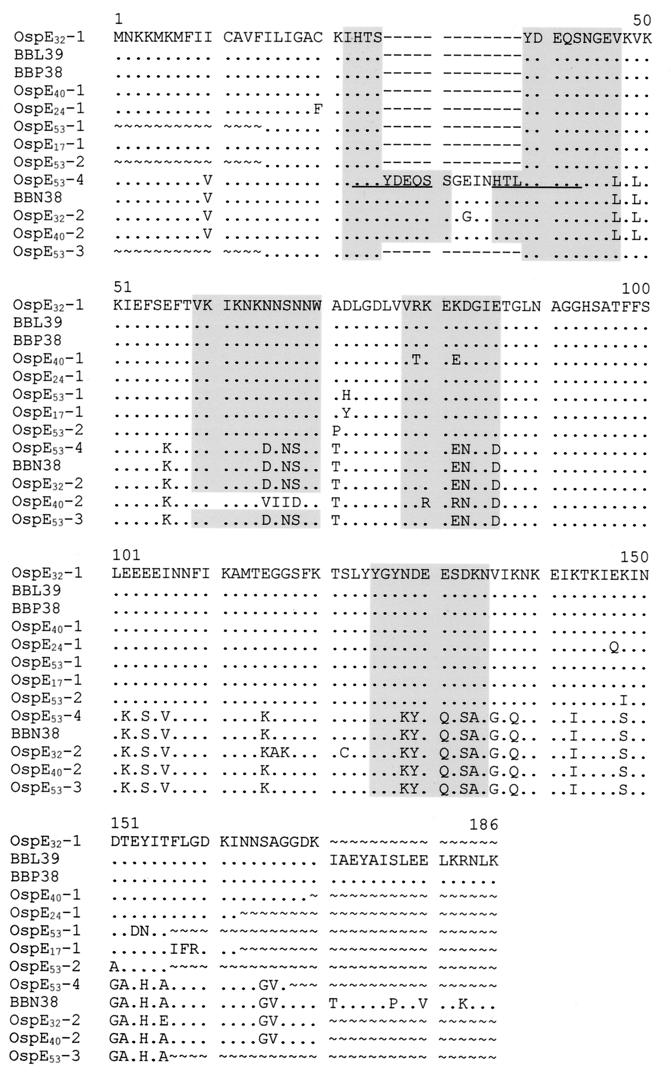

To specifically identify the nature of the changes that occurred during infection, the polymorphic amplicons obtained from three arbitrarily selected B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clones (clones 32, 40, and 53) were ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector for subsequent sequence analysis. E. coli colonies carrying recombinant plasmids (white colonies) were picked and cultivated, and plasmid was isolated. The inserts of the plasmids were sequenced using a variety of primers. The determined sequences were translated and aligned with the B. burgdorferi B31G BBL39, BBN38, and BBP38 sequences (Fig. 2). All of the determined sequences possessed intact reading frames. Two variant ospE genes were recovered from B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 32 and sequenced in their entirety. One of these, ospEc32-1, was identical in sequence to the BBL39 and BBP38 genes. The second variant, ospEc32-2, was found to be distinct from, but most closely related to, BBN38. Point mutations have resulted in amino acid sequence changes in this allele (relative to all three parental ospE alleles). One of the amino acid changes in OspEc32-2 resides within hypervariable domain 1, a region predicted to be hydrophilic, surface exposed on the protein, and antigenic (16, 26). Four additional amino acid changes are present in other regions of the protein. From B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 40, two variant genes were recovered, ospEc40-1 and ospEc40-2. ospEc40-1 is most closely related to BBP38 and BBL39. Relative to these sequences, two amino acid changes were detected, with both occurring in a predicted antigenic domain. The second variant, ospEc40-2, is most closely related to BBN38 but harbors six amino acid changes. Four of these changes are consecutive and, based on computer predictions, would alter the antigenic properties of the protein relative to its inferred parental gene (BBN38). The replacement of the amino acid sequence, DNNS in the parental sequence, with VIID changes the properties of this domain from antigenic to nonantigenic. From B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53, three distinct variants were characterized. OspEc53-1 has three amino acid changes relative to BBL39 and BBP38 and OspEc53-2 has two. None of these changes occur in computer-predicted antigenic domains. The variant exhibiting the greatest net change is OspEc53-3. While the N-terminal domain of this variant is identical to BBL39-BBP38 (up to amino acid position 55), the remainder of the protein is identical to BBN38. This variant appears to be a hybrid gene that has arisen though exchange of sequence between BBN38 and either BBL39 or BBP38. It is important to note that an exact copy of BBN38 was recovered from clone 53. This raises the possibility that the postulated exchange event was unidirectional. Variant ospE genes were also recovered from B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clones 17 and 24. OspEc17-1, and OspEc24-1 have four and two aa changes, respectively (relative to BBL39-BBP38). These sequence changes had no effect on the predicted antigenic or physical properties of the inferred parental gene, which was either BBL39 or BBP38.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of ospE variants carried by postinfection isogeneic clones derived from B. burgdorferi B31Gc1. The determined sequences were translated, and the deduced amino acid sequences were aligned. Gaps introduced by alignment are indicated by hyphens, conserved positions are indicated by periods, and positions for which sequence has not been determined are indicated by tildes. Regions that are predicted by computer analyses to be hydrophilic and surface exposed and to possess a positive Jameson and Wolf antigenic index are boxed and shaded. Direct repeat motifs are indicated by underlining. Note that all presented sequences were determined as part of this report except for those of BBN38, BBL39, and BBP38, which were previously determined (10).

Analysis of the stability of ospE alleles during cultivation in the laboratory.

To determine if sequence changes occur in the ospE genes during in vitro cultivation, ospE sequences were determined for several different populations after extensive in vitro cultivation. An extensively passaged population of B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 was not available for these analyses; however, populations of B. burgdorferi Sh-2-82 clone 1A7 (passage 10 and 137) and uncloned Borrelia garinii Pbi (passage 7 and 311) were. Using the uhb(+)-E470(−) primer set, ospE genes were amplified from these populations and sequenced. No changes were observed, indicating that these genes are stable during in vitro cultivation. It is important to note that although PCR procedures can lead to misincorporation of nucleotides at a low frequency, it can be concluded with certainty that this was not the case in the analyses of the infection-derived ospE variants described above, since the polymorphisms identified were detected in multiple independently analyzed B. burgdorferi infection-derived clones, and using the same PCR conditions, polymorphisms were not detected in the in vitro-cultivated bacteria.

Analysis of the humoral immune response to the OspE variant proteins that arose during infection in mice.

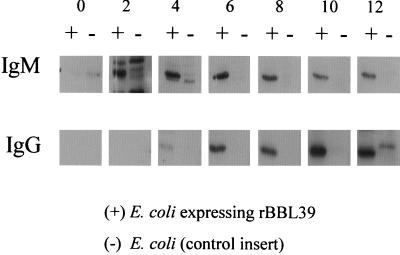

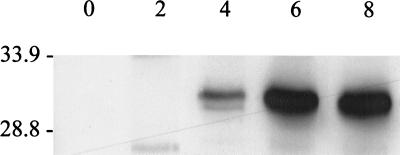

The development of sequence changes in ospE alleles during infection but not during in vitro cultivation suggests that the mammalian environment either leads to or selects for the development of genetic changes. One mammalian environmental parameter that could be involved is the humoral immune response. Hence, we first sought to confirm that an anti-OspE antibody response is mounted during experimental infection in C3H/HeJ mice when infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1. Note that, while we infected several mice in these studies, all antisera utilized in these analyses (unless otherwise indicated) came from the same mouse from which the isogenic B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clones harboring polymorphic ospE-related genes were recovered. To allow for the assessment of the anti-OspE antibody response, BBL39 was cloned using LIC and expressed in E. coli by IPTG induction. The cell lysates of the induced cultures were then used as test antigen in immunoblot analyses. To confirm that the E. coli strain was expressing the recombinant OspE protein, immunoblotted cell lysates were first screened with polyclonal anti-OspE antiserum (kindly provided by Erol Fikrig, Yale University). Expressed recombinant OspE was readily detected by this approach. To determine if the recombinant protein was recognized by anti-B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 antiserum and to assess the temporal pattern of that response, we analyzed both the anti-OspE IgG and anti-OspE IgM response over the 3-month infection time frame. Cell lysates of E. coli expressing BBL39 were immunoblotted and screened with sera collected at different time points from the infected mice. Lysates from uninduced E. coli served as the negative control. Prior to the immunoblot analyses, the infection-derived antisera were preabsorbed with uninduced E. coli. An IgM response to the recombinant protein was evident by 2 weeks and persisted up through week 12 but began to wane at week 8 (Fig. 3). An IgG response was evident at week 4 and persisted through week 12. These analyses confirm that a humoral immune response to OspE is mounted during infection and raise the possibility that immune pressure could be a factor in either generating or selecting for OspE mutations.

FIG. 3.

Demonstration and temporal assessment of the IgG and IgM response to OspE in experimentally infected mice. Preparative SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels of cell lysates of E. coli either induced (+) or not induced (−) to express recombinant BBL39 were electrophoresed, immunoblotted, and cut into strips for screening with the infection-derived antisera obtained at different time points postinfection (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 weeks) from a mouse infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1. Both the IgM and IgG responses were assessed as described in the text.

Analysis of the temporal development of the humoral immune response to OspE variants that arose during infection.

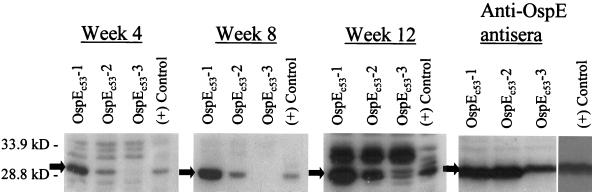

If the ospE variant genes that arose during infection are expressed and are antigenically distinct, then a humoral immune response to them would be expected to develop later in the 3-month course of infection than the antibody response to the parental OspE proteins, which is evident by week 2 of infection. To assess the humoral immune response to OspE variants that arose during infection, the ospE variants recovered from B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53 (ospEc53-1, ospEc53-2, and ospEc53-3) were amplified using primers designed for LIC, annealed to the pT7Blue-2 LIC vector, and transformed and expressed in E. coli. Recombinant E. coli strains carrying these ospE LIC plasmids were induced with IPTG, and cell lysates were used as the test antigen in immunoblot analyses. First, the expression of each individual OspE variant in E. coli was confirmed by immunoblot analysis using the polyclonal anti-OspE antisera described above. All OspE variants were found to be expressed (Fig. 4) and to be immunoreactive with the polyclonal anti-OspE antisera. The immunoblot signal associated with OspEc53-3 was slightly less than that seen with OspEc53-1 and OspEc53-2. This could indicate a slightly lower expression level for this protein or could indicate that OspEc53-3 has altered antigenic characteristics and is not recognized as efficiently as other OspE variants. Additional immunoblots were then screened with preabsorbed infection-derived antisera from mice infected for either 0, 4, 8, or 12 weeks (Fig. 4). The recombinant proteins were not reactive with the prebleed serum (data not shown). OspEc53-1 and OspEc53-2 were both immunoreactive with the sera from the 4-, 8-, and 12-week points, although quantitative differences in associated signal were observed. The presence of antibodies recognizing these OspE variants during early infection indicates that these variants arose and were expressed very early during infection. Alternatively, and perhaps most likely, these proteins are recognized by antibodies that were generated against the parental OspE. Since there are only a few amino acid differences among OspEc53-1, OspEc53-2, and BBL39 (a parental allele), cross-immunoreactivity is a strong possibility. However, antibodies recognizing OspEc53-3 were not detected until the 12-week point, and the observed immunoreactivity even at that point was relatively weak. Since OspEc53-3 is not recognized by anti-OspE antibodies that are present during early infection, it appears that OspEc53-3 is antigenically distinct from other OspE variants that are expressed early during infection. In addition, the late development of the anti-OspEc53-3 response, which was not observed until week 12 postinfection, suggests that the gene encoding OspEc53-3 did not arise until a few weeks postinfection. Alternatively, the gene may have arisen early during infection, but its expression was selectively repressed. The analyses described below support the former possibility.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the humoral immune response to OspE variants that arose during experimental infection in mice. Cell lysates of E. coli that were induced with IPTG to express LIC fusion proteins of either OspEc53-1, OspEc53-2, OspEc53-3, or BBL39 (positive control) (indicated above each lane) were fractionated in SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted. Identical blots were screened with the infection-derived sera (described in the legend to Fig. 3) from either the 0 (data not shown)-, 4-, 8-, or 12-week infection time frames (as indicated). One immunoblot was screened with a polyclonal anti-OspE antiserum to confirm that the recombinant proteins were being expressed by E. coli.

Analysis of the possible temporal expression of OspEc53-3 during infection in mice.

One possible interpretation of the delayed immune response to OspEc53-3 is that this variant gene arose very early during infection but was not expressed until later stages of infection. To assess this possibility, we infected mice with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53 and then analyzed the temporal development of the IgG immune response to OspEc53-3. Sera were collected over a 10-week period at 2-week intervals. Immunoblots of E. coli expressing OspEc53-3 were then screened with the infection-derived antisera. Antibodies that recognized OspEc53-3 were readily detectable in sera from mice infected for 4 weeks and beyond (Fig. 5). These data suggest that OspEc53-3 is not specifically down regulated early during infection and that the delayed immune response to OspEc53-3 described above was a consequence of the emergence of this variant gene during infection.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the temporal pattern of the humoral immune response to OspEc53-3 in mice infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53. C3H/HeJ mice were infected as described in the text with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53, which was originally recovered from an ear punch biopsy specimen from mice infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1, and serum samples were collected at 2-week intervals. Cell lysates of E. coli expressing the recombinant OspEc53-3 LIC fusion protein were electrophoresed, immunoblotted, and screened with the sera collected at different time points postinfection. Molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons.

DISCUSSION

The data presented in this study provide the first evidence of the genetic instability of members of the ospE gene family during infection and provide support for the hypothesized role of these proteins in immune response evasion. We have demonstrated that variant forms of the ospE genes arise specifically during infection and are expressed and that some exhibit altered antigenicity. The molecular nature of the polymorphisms in the ospE-related gene sequences suggests that multiple molecular mechanisms are involved in their generation. For example, the polymorphisms present in OspEc53-1 and OspEc53-2 (as well as in several other variants described above) represent simple nucleotide substitutions that resulted in alterations in the amino acid sequence of the proteins. These types of mutations can result from a variety of molecular mechanisms. The OspEc53-3 variant exhibits a distinctly different type of polymorphism. This variant appears to have arisen as a result of a recombination event between BBN38 and BBL39-BBP38. The 5′ end of ospEc53-3 and its upstream sequence are identical to that of BBL39-BBP38 while the rest of the gene sequence is identical to that of BBN38. This event appears to be unidirectional. Early work by our laboratory as well as by others provided evidence of past recombination and gene rearrangement events in the UHB-flanked genes; however, these studies did not specifically demonstrate the occurrence of these events during infection (2, 16, 23, 26).

To address the possibility that the development of some of the ospE polymorphisms could have resulted from decreased DNA replication fidelity during infection, perhaps induced by the stresses applied by the mammalian system, we also analyzed the genetic stability of the single-copy, UHB-flanked ospG gene. This gene was originally identified by Wallich et al. in B. burgdorferi ZS7 (27). Sequencing of B. burgdorferi B31G revealed that a homolog, designated BBS41, is carried by this isolate. We reconfirmed the presence of ospG in the B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 genome through PCR and confirmed that it was single copy by Southern hybridization using an ospG-targeting oligonucleotide (data not shown). Using a primer set designed to amplify most of the ospG gene, amplicons were obtained from all isogeneic postinfection populations. The size of the amplicons was conserved, indicating that gross polymorphisms in the form of insertions and/or deletions did not develop in ospG during infection. SNP analyses of the ospG amplicons from 30 different postinfection B. burgdorferi B31Gc1-derived clones were performed, and polymorphisms were not detected. In addition, three of these amplicons were sequenced in their entirety and found to be 100% identical to the ospG gene carried by the preinfection, parental clone. These analyses indicate that ospG is stable during infection and suggest that the polymorphisms that developed in the ospE alleles were not reflective of a general breakdown in replication fidelity during infection. It is also important to note that on a technical level these analyses indicate that the conditions employed in the PCR and SNP analyses of the ospE and ospG genes do not lead to misincorporation of nucleotides or other PCR artifacts. From these analyses, it can also be concluded that not all UHB-flanked genes undergo rearrangement or sequence changes during infection (at least at a frequency equivalent to that of the ospE genes). However, due to the multiallelic nature of other UHB-flanked gene families, these additional families may be potential candidates for mutation and rearrangement during infection in a manner similar to that of the ospE gene family. In fact, evolutionary analyses suggest that these processes have in fact occurred in other UHB-flanked genes (2, 23).

To assess the humoral immune response to some of the variant OspE proteins that arose during infection, the variant genes were cloned, expressed, and used as test antigen in immunoblot analyses with antisera collected at different time points postinfection. Two of the variants (OspEc53-1 and OspEc53-2) were recognized by IgG antibodies present in the infection-derived sera collected at the 4-week point. Since these variants possess only a few amino acid changes relative to their parental genes (BBL39-BBP38), it is likely that they are immunologically cross-reactive with antibodies generated against the OspE-related proteins expressed by the parental clone. In view of this, inferences about the time point at which these variant genes arose during infection (i.e., early versus late infection) cannot be made. However, the humoral immune response to OspEc53-3 exhibited a distinctly different pattern. Even though a vigorous anti-OspE antibody response was mounted early during infection, antibodies that recognize OspEc53-3 were not detected in mice infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 until 12 weeks postinfection, indicating that this variant is antigenically distinct. Secondly, the delayed antibody response to OspEc53-3 supports the conclusion that this variant gene arose during infection. The follow-up experiments in which an early anti-OspEc53-3 IgG response was detected in mice infected with B. burgdorferi B31Gc1 clone 53, which carries OspEc53-3, confirmed that the delayed response to OspEc53-3 noted in the first round of infection was not due to a specific down regulation of expression during the early stages of infection.

The data presented here provide direct evidence for the development of molecular and antigenic changes in the ospE gene family during experimental infection in C3H/HeJ mice. This finding is in contrast to that reported by others, who concluded that these genes are genetically stable during infection (11). One critically important aspect of the analyses presented here is that we utilized a thoroughly characterized isogeneic population of B. burgdorferi for which the entire genome sequence and plasmid composition are known. In contrast, Hage et al. utilized B. burgdorferi N40, which has not been fully characterized with respect to its plasmid or ospE gene family composition (11). Although Hage et al. alluded to the importance of using isogeneic populations for these types of analyses, they did not do so in their analyses (11). If uncloned populations were used, then polymorphisms that develop in a subset of the population could easily have been missed, a possibility alluded to by the authors (11).

Based on the characteristics of infection with the Lyme disease spirochetes, it is evident that these bacteria exploit antigenic variation, whether it be mediated by the Vls or by the OspE proteins, in a more subtle way than the Vmp antigenic variation system of the relapsing fever spirochetes (4, 5). The Vmp proteins are dominant antigens that are expressed at high levels during infection, and it has been clearly established that antigenic variation in these proteins is the basis for the molecular pathogenesis of relapsing fever. In the Lyme disease spirochetes, there appear to be several different gene families that collectively enhance the antigenic diversity of these bacteria during infection either in their natural mammalian reservoirs or in their accidental human hosts. The Lyme disease spirochetes carry an extraordinary number of plasmid-carried genes encoding surface-exposed proteins, with most organized into extensive gene families (10). The genetic redundancy of the plasmid component of the Borrelia genome renders it a likely candidate and template for recombination and rearrangement. Continual but gradual change in this vast repertoire of genes, coupled with the differential expression of members of some gene families (1, 8, 21, 25) and the diversity introduced by the lateral transfer of plasmids (6, 12, 15), may provide the Lyme disease spirochetes with sufficient genetic and antigenic diversity to maintain chronic infection in untreated mammals. In addition, these processes could serve to maintain Lyme disease spirochete populations in their natural mammalian reservoirs in nature and thus play an important role in maintenance of the enzootic cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Chia-Ling Hsieh for assistance and support throughout this study. We thank Justin Radolf, Melissa Caimano, and our colleagues in the Molecular Pathogenesis Group at Virginia Commonwealth University for thoughtful discussions and support.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Jeffress Trust and the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D, Porcella S F, Popova T G, Shevchenko D, Baker S I, Li M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins D R, Caimano M J, Yang X, Cerna F, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1526–1532. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1526-1532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asbrink E, Hovmark A. Successful cultivation of spirochetes from skin lesions of patients with erythema chronicum migrans Afzelius and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Sect B. 1985;93:161–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1985.tb02870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour A G. Antigenic variation of a relapsing fever Borrelia species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1990;44:155–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.44.100190.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour A G. Immunobiology of relapsing fever. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1987;8:125–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caimano M J, Yang X, Popova T G, Clawson M L, Akins D R, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Molecular and evolutionary characterization of the cp32/18 family of supercoiled plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi 297. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1379–1399. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1574-1586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa P A, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Champion C I, Blanco D R, Skare J T, Haake D A, Giladi M, Foley D, Miller J N, Lovett M A. A 9.0-kilobase-pair circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi encodes an exported protein: evidence for expression only during infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2653–2661. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2653-2661.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demerec M. A proposal for a uniform nomenclature in bacterial genetics. Genetics. 1966;54:61–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/54.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser C, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischman R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fujii C, Cotton M D, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith H O, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hage N E, Lieto L D, Stevenson B. Stability of erp loci during Borrelia burgdorferi infection: recombination is not required for chronic infection of immunocompetent mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3146-3150.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jauris-Heipke S, Liegl G, Preac-Mursic V, Robler D, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Molecular analysis of genes encoding outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: relationship to ospA genotype and evidence of lateral gene exchange of ospC. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1860–1866. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1860-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam T T, Nguyen T-P K, Montgomery R R, Kantor F S, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Outer surface protein E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1994;62:290–298. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.290-298.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Garon C F. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:926–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.926-932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Landry R K, Garon C F. Analysis of the distribution and molecular heterogeneity of the ospD gene among the Lyme disease spirochetes: evidence for lateral gene exchange. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4572–4582. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4572-4582.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marconi R T, Sung S Y, Hughes C N, Carlyon J A. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and share a common upstream homology box. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5615–5626. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5615-5626.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nocton J J, Dressler F, Rutledge B J, Rys P N, Persing D H, Steere A C. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid in Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401273300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves P R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R H, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:498–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. Antigen diversity in the bacterium B. hermsii through “somatic” mutations in rearranged vmp genes. Cell. 1994;78:867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Restrepo B I, Carter C J, Barbour A G. Activation of a vmp pseudogene in Borrelia hermsii: an alternate mechanism of antigenic variation during relapsing fever. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skare J T, Foley D M, Hernandez S R, Moore D C, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Cloning and molecular characterization of plasmid-encoded antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4407–4417. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4407-4417.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevenson B, Bono J L, Schwan T G, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2648–2654. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson B, Casjens S, Rosa P. Evidence of past recombination events among the genes encoding Erp antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 1998;144:1869–1879. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P A. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung S-Y, LaVoie C, Carlyon J A, Marconi R T. Genetic divergence and evolutionary instability in ospE-related members of the upstream homology box gene family in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex isolates. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4656–4668. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4656-4668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallich R, Brenner C, Kramer M D, Simon M M. Molecular cloning and immunological characterization of a novel linear-plasmid-encoded gene, pG, of Borrelia burgdorferi expressed only in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3327–3335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3327-3335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Popova T G, Hagman K E, Wikel S K, Schoeler G B, Caimano M J, Radolf J D, Norgard M. Identification, characterization, and expression of three new members of the Borrelia burgdorferi Mlp (2.9) lipoprotein gene family. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6008–6018. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6008-6018.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J-R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris A G. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease Borreliae by promiscuous recombination of vmp-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]