Abstract

Objectives:

Attrition is very common in longitudinal research, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing psychological interventions. Establishing rates and predictors of attrition in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) can assist clinical trialists and intervention developers. Differential attrition in RCTs that compared MBIs with structure and intensity matched active control conditions also provides an objective metric of relative treatment acceptability.

Methods:

We aimed to evaluate rates and predictors of overall and differential attrition in RCTs of MBIs compared with matched active control conditions. Attrition was operationalized as loss to follow-up at post-test. Six online databases were searched.

Results:

Across 114 studies (n = 11,288), weighted mean attrition rate was 19.1% (95% CI [.16, .22]) in MBIs and 18.6% ([.16, .21]) in control conditions. In the primary model, no significant difference was found in attrition between MBIs and controls (i.e., differential attrition; odds ratio [OR] = 1.05, [0.92, 1.19]). However, in sensitivity analyses with trim-and-fill adjustment, without outliers, and when using different estimation methods (Peto and Mantel-Haenszel), MBIs yielded slightly higher attrition (ORs = 1.10 to 1.25, ps < .050). Despite testing numerous moderators of overall and differential attrition, very few significant predictors emerged.

Conclusions:

Results support efforts to increase the acceptability of MBIs, active controls, and/or RCTs, and highlight the possibility that for some individuals, MBIs may be less acceptable than alternative interventions. Further research including individual patient data meta-analysis is warranted to identify predictors of attrition and to characterize instances where MBIs may or may not be recommended. Meta-Analysis Review Registration: Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/c3u7a/)

Keywords: attrition, differential attrition, mindfulness-based interventions, treatment acceptability, meta-analysis

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have become increasingly visible within the scientific literature and popular culture in the past two decades (Van Dam et al., 2018). MBIs are a sub-category of third wave behavior therapies which share, among various features, an emphasis on acceptance (Hayes, 2004; Hayes & Hofmann, 2017). MBIs specifically aim to train regulation of attention towards present moment experiences without judgment through formal mindfulness meditation practice (Crane et al., 2017; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Standardized MBIs that have been repeatedly tested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) include mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 2013), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2013), and closely related programs such as mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP; Bowen et al., 2009), mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE; Garland et al., 2019), and mindfulness-based cancer recovery (MBCR; Carlson, 2013). These MBIs are designed to benefit various clinical targets such as depression relapse, chronic stress, recovery from cancer treatment, pain, and substance use.

Meta-analyses of RCTs examining the efficacy of MBIs have noted promising effects on a range of clinical outcomes, although results vary somewhat (e.g., by target population, comparison condition; Galante et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2018, 2021c; Goyal et al., 2014). On the whole, MBIs appear superior to non-specific control conditions (e.g., waitlist, minimal treatment) and slightly superior to or on par with specific active control conditions (i.e., intended to be therapeutic; Goldberg et al., 2021c; Wampold et al., 1997). Evidence for efficacy is most robust for psychological symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety) in both clinical and non-clinical populations with modest indications of potential benefits on aspects of physical health as well (e.g., chronic pain, sleep; Khoo et al., 2019; Rusch et al., 2019).

Like other evidence-based treatments, the empirical support for MBIs rests primarily on RCTs (American Psychological Association, 2006). And, like all longitudinal designs, RCTs are vulnerable to missing data due to attrition, resulting from participants dropping out of the treatment and/or the study. The issues of treatment dropout, study attrition, and the associated missing data have been examined within the broader psychotherapy literature (e.g., Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Swift et al., 2017). For example, Swift and Greenberg (2012) reported a weighted dropout rate of 19.7% in review of 669 psychotherapy studies (although not all were RCTs). Estimates based on the RCT literature (e.g., individual psychotherapy for major depressive disorder) have been similar (17.5%; Cooper & Conklin, 2015).

There are several reasons to attend to attrition and its consequences. For one, missing data can have important statistical consequences, such as reducing power and biasing parameter estimations (Crutzen et al., 2015; Graham, 2009; Hansen et al., 1985). In recognition of the need to handle missingness appropriately, a variety of methods have been proposed for use within the context of RCTs (e.g., multiple imputation, maximum likelihood estimation, sensitivity analyses for missing not at random; Graham, 2009; Power & Freeman, 2012). Alongside statistical consequences, attrition can also reflect treatment unacceptability and signal potential barriers to delivery that may reduce effectiveness in the real world (Hansen et al., 1985; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Although some clients do drop out of treatment due to improved symptoms (Simon et al., 2012), it is generally linked with poorer outcomes (e.g., Bjoörk et al., 2009). Attrition may also indicate issues of safety, with participants dropping out due to adverse experiences (Baer et al., 2019; Dobkin et al., 2012).

The issue of attrition in MBI RCTs has been raised previously (e.g., Khoury et al., 2013, Nam & Toneatto, 2016), although it remains largely unexplored empirically. Reviews of this literature have reported a range of overall attrition rates, with some estimates similar to the general psychotherapy literature (e.g., 16.25%; Khoury et al., 2013) and others somewhat higher (29%; Nam & Toneatto, 2016). However, to our knowledge no study has provided meta-analytically derived attrition estimates (i.e., inverse variance weighted and based on a systematic search) nor have prior studies investigated characteristics that may be associated with attrition rate (i.e., meta-analytic moderators). A thorough understanding of characteristics (e.g., participant-, program-, clinician-, or study-related) that predict higher attrition rates would be highly useful for clinical trialists seeking to plan adequately powered studies. Moreover, understanding who may be more likely to drop out of MBIs can inform treatment design and adaptation.

RCTs can provide estimates of overall attrition (e.g., Khoury et al., 2013; Nam & Toneatto, 2016). And, while study attrition is likely correlated with treatment dropout, in theory participants may drop out of RCTs due to factors related to RCT procedures (e.g., burden of completing assessments) and may drop out of the RCT but remain in the treatment (e.g., refuse to complete post-treatment assessments). Importantly, due to randomization, RCTs are uniquely well-suited for evaluating differential attrition. Differential attrition refers to the difference of attrition rate between treatment conditions (Bell et al., 2013). Within RCTs, assuming randomization is successful (i.e., groups are adequately matched at baseline), one can conclude that differences in attrition rates between groups result from the condition to which individuals are randomly assigned (Goldberg et al., 2021a). When conditions are not matched in intensity (e.g., active intervention vs. waitlist control), it can be difficult to interpret the cause of differences in attrition between groups (beyond the active vs. passive characteristic). However, when conditions are matched in structure and intensity (e.g., similar treatment format, similar number of sessions), one can infer that higher attrition for individuals assigned to one condition (i.e., differential attrition) indicates lower acceptability for this condition relative to the comparator (Bell et al., 2013; Goldberg et al., 2021a).

Within the context of MBI RCTs, robust estimates of differential attrition would be a valuable objective metric for acceptability of MBIs relative to other treatment approaches. Given MBIs tend to perform on par with other therapies, predicted acceptability for a particular individual (e.g., based on clinical characteristics) could guide if or when MBIs are to be recommended.

Two recent meta-analyses evaluated the differential attrition of MBIs relative to active control conditions and found contrasting results. Goldberg et al. (2020) explored the efficacy and acceptability of MBIs for military veterans in comparison to active control groups and found that MBIs were associated with higher attrition relative to controls for military veterans (odds ratio [OR] = 1.98, p < .050, k = 9), raising questions regarding the acceptability of MBIs in this population. Sun et al. (2021) explored the efficacy and acceptability of MBIs among people of color (POC) in comparison to active control groups. However, results showed that MBIs were not associated with higher attrition relative to controls in predominantly racial/ethnic minority participants (OR = 0.98, p = .91, k = 8). Given the discrepant findings of these prior reviews which focused on small subsets of the literature, it is worthwhile examining whether differential attrition appears across the MBIs literature generally and which study characteristics (e.g., MBI type, participant demographics) are associated with rates of differential attrition.

In sum, rates of both overall and differential attrition in MBI RCTs are unclear based on the available evidence and no study has examined characteristics that may account for variation in attrition rates. Lacking reliable estimates of attrition and a thorough understanding of factors that influence attrition makes it difficult for clinical trialists to adequately plan for attrition and for treatment developers and clinicians to address intervention-related factors that might augment acceptability. It also remains unclear when, if ever, MBIs may be perceived a more or less acceptable than alternative intervention approaches.

To address these gaps, we conducted a meta-analysis of overall and differential attrition rates in RCTs of MBIs. In order to allow estimation of both overall and differential attrition, we restricted our sample to RCTs comparing MBIs to structure and intensity matched active control conditions. Given the heterogeneity in MBIs that have been tested, we restricted our review to MBIs similar in structure to the first and paradigmatic MBI: MBSR. We focused our literature search on MBSR and adaptations of MBSR which have themselves been widely tested in RCTs (i.e., MBCT, MBRP, MORE, MBCR). As treatment dropout is not always clearly defined or clearly reported within RCTs, we used loss to follow-up at post-treatment assessment as our metric of attrition (Crutzen et al., 2015). In exploratory analyses, we examined a wide variety of potential moderators of attrition, including participant (e.g., demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics), program (e.g., MBI and comparison types, group vs. individual format, recruitment settings), clinician (e.g., instructor training), and study characteristics (e.g., year of publication).

Methods

Protocol and Registration

This study was preregistered through the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/c3u7a/). It was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). We made the following six deviations from our preregistered plan. First, we operationalized attrition as study attrition (i.e., absence from post-treatment data collection). This was done to allow a uniform definition of attrition, as authors did not consistently define intervention completion. Second, standardized mean differences for completers versus dropouts were not analyzed as these data were not reported. Third, we conducted trim-and-fill analyses, created contour-enhanced funnel plots, and conducted the Harbord test (Harbord et al., 2006) to evaluate the impact of publication bias. Fourth, MBIs were required to be ≥ 6 sessions and/or weeks in duration. This duration was selected to allow some deviation from the length of MBSR (i.e., weekly meetings for 8 weeks) while retaining a similar intensity of intervention. Fifth, we examined the bibliography of two recent large-scale meta-analyses (Galante et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2018) for potentially eligible studies. Sixth, we examined differential attrition using Peto’s and Mantel-Haenszel’s methods which are recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for conducting meta-analysis with rare events data (Higgins & Thomas, 2019).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected based on the following criteria: (a) delivery of an MBI, (b) randomized-controlled trial design, (c) at least one matched active control group, (d) reported the number of study dropouts. As we intended our results to be generalizable to the most commonly available MBIs, MBIs in the included studies were required to be based on approximately the same length (i.e., 6 to 8 weeks and/or sessions excluding the retreat day) and content of the following widely studied and standardized MBIs: MBSR, MBCT, MBRP, MORE, MBCR. Active control groups were included if they had roughly the same structure and duration of the MBIs (i.e., structure and intensity matched). Specifically, the total treatment duration of these active control groups was required to be at least 50% of the MBI groups (and the number of MBI and control treatment sessions was tested as a moderator). Active controls were eligible whether or not they were explicitly intended to be therapeutic (i.e., bona fide active controls; Wampold et al., 1997). However, this control group feature was coded and tested as a moderator of differential attrition based on the possibility that participants may find non-bona fide control groups less acceptable. Control groups that incorporated other forms of contemplative practice included in MBIs (e.g., yoga, other types of meditation training) were excluded. In order to isolate the effects of MBIs (i.e., interventions that included mindfulness meditation training; Crane et al., 2017) on attrition, interventions that primarily train the attitudinal aspects of mindfulness (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy) were excluded. No restrictions were placed on publication status, intervention format (virtual vs. in-person, individual vs. group), language, or population (i.e., clinical and non-clinical samples, adults and children).

Information Sources

We searched six databases including PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane clinical trials registry from the first available date until July 16, 2020. In addition, we also handsearched the bibliography of two recent large-scale MBI meta-analyses (Galante et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2018).

Search

As we were interested in examining attrition in specific widely studied and standardized MBIs, consistent with prior reviews (e.g., Kuyken et al., 2016) we included intervention-specific search terms: (“mindfulness-based stress reduction” OR MBSR OR “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy” OR “MBCT” OR “mindfulness-based relapse prevention” OR “MBRP” OR “mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement” OR “mindfulness-based cancer recovery” OR “MBCR”) AND (random*) (Supplemental Materials Table 1).

Study Selection

Studies were independently reviewed by two authors and evaluated based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Title and/or abstracts were screened first. For studies that passed initial screening, full texts were reviewed. Coding disagreements were discussed with the corresponding author until reaching consensus. Inter-rater reliabilities for inclusion at title and/or abstract and full text levels were good to excellent (i.e., ICC ≥ .60; Cicchetti, 1994).

Data Collection Process

Standardized spreadsheets were created for coding study data. Data were independently extracted by the first and second authors. For clinical trials registration, studies were excluded if they were still recruiting. If study recruitment was completed or unknown, authors were contacted regarding the availability of data. Data from nine out of 61 RCTs were received from authors (Andersen et al., 2020; Daubenmier et al., 2016; Garland et al., 2016; Jasbi et al., 2018; King et al., 2016; Marchant et al., 2021; Marciniak et al., 2020; Metin et al., 2019; van der Donk et al., 2019). Five studies (Brewer et al., 2009; Brewer et al., 2011; Fiocco et al., 2019; Garland et al., 2010; Morone et al., 2009) were included based on handsearching searching the two recent meta-analyses (Galente et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2018).

Data Items

Data necessary for computing attrition rates were extracted. Specifically, we extracted the intention-to-treat (ITT) and completer sample sizes in both MBIs and control conditions.

To examine predictors of attrition, we also extracted study-level characteristics (i.e., participant, program, clinician, and study design characteristics). Given the absence of prior work, we sought to examine a wide variety of potential predictors in exploratory analyses. We examined ten participant characteristics including five demographic variables (i.e., age, racial/ethnic minority status, gender, marital status, education), four population types (i.e., psychiatric, medical, veterans, non-clinical), and country (Table 2). We examined five program factors including treatment duration (i.e., number of sessions), MBI type (MBSR, MBCT, MORE, MBRP, MBCR), control type (specific active control vs. non-specific active control), treatment adaptation (whether MBI or control were adapted for specific population), and treatment format (group vs. individual). Whether the instructor had completed formal training was the only clinician factor assessed. In the current study, formal training refers to whether the MBI instructor had completed meditation-related training or certification (e.g., completed MBSR teacher training) or whether the MBI instructor of control condition instructor had completed various forms of formal clinical training (e.g., clinical degrees in counseling or social work). We also examined two study design factors including recruitment setting (whether recruitment occurred in a clinical setting [e.g., hospital], non-clinical setting [e.g., community], or both), and year of publication.

Table 2.

Results of moderator tests (k = 114)

| Predictor | MBIb | MBIp | Controlb | Controlp | Differentialb | Differentialp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant factors | ||||||

| Age | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | .102 | −0.00 [−0.00, −0.00] | .005** | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | .728 |

| Percentage REM | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | .684 | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | .240 | −0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | .561 |

| Percentage female | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | .922 | 0.00 [−0.00, 0.00] | .866 | 0.00 [−0.00, 0.01] | .446 |

| Percentage married | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | .054 | −0.00 [−0.00, 0.00] | .014* | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | .489 |

| Some college | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.09] | .437 | 0.04 [−0.01, 0.09] | .130 | −0.24 [−0.50, 0.01] | .063 |

| Population | ||||||

| Psychiatric | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.09] | .437 | 0.04 [−0.01, 0.09] | .130 | −0.24 [−0.50, 0.01] | .063 |

| Medical | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.05] | .867 | −0.03 [−0.08, 0.02] | .291 | 0.19 [−0.07, 0.45] | .153 |

| Veterans | 0.04 [−0.08, 0.16] | .516 | 0.02 [−0.08, 0.12] | .709 | −0.04 [−0.58, 0.51] | .893 |

| Non-clinical | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.04] | .523 | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.04] | .657 | 0.05 [−0.26, 0.36] | .746 |

| Country | ||||||

| Asia | −0.01 [−0.11, 0.10] | .908 | −0.01 [−0.10, 0.08] | .763 | 0.14 [−0.27, 0.56] | .491 |

| Europe | −0.01 [−0.09, 0.07] | .773 | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.05] | .577 | 0.04 [−0.32, 0.41] | .820 |

| North America | 0.04 [−0.02, 0.10] | .150 | 0.05 [−0.00, 0.10] | .056 | −0.10 [−0.38, 0.17] | .462 |

| South America | 0.08 [−0.15, 0.30] | .499 | −0.03 [−0.22, 0.17] | .781 | 0.64 [−0.34, 1.61] | .201 |

| Iran | −0.09 [−0.23, 0.05] | .208 | −0.10 [−0.22, 0.02] | .099 | 0.34 [−0.58, 1.27] | .466 |

| Others | −0.15 [−0.30, 0.00] | .051 | −0.08 [−0.22, 0.05] | .211 | −0.91 [−1.91, 0.09] | .075 |

| Program factors | ||||||

| Treatment duration | ||||||

| # MBIs sessions | 0.00 [−0.010, 0.02] | .601 | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | .993 | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.08] | .570 |

| # Control sessions | 0.00 [−0.010, 0.02] | .601 | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | .993 | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.08] | .570 |

| MBI type | ||||||

| MBSR | −0.04 [−0.10, 0.02] | .214 | −0.03 [−0.09, 0.02] | .200 | −0.02 [−0.28, 0.24] | .875 |

| MBCT | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.06] | .829 | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.05] | .726 | 0.04 [−0.25, 0.33] | .777 |

| MORE | 0.09 [−0.05, 0.23] | .208 | 0.06 [−0.06, 0.19] | .349 | 0.26 [−0.31, 0.82] | .376 |

| MBCR | 0.16 [−0.14, 0.45] | .305 | 0.11 [−0.14, 0.37] | .388 | 0.17 [−0.73, 1.08] | .707 |

| MBRP | 0.11 [−0.02, 0.23] | .109 | 0.13 [0.02, 0.25] | .019* | −0.26 [−0.72, 0.20] | .261 |

| Specific active control | 0.06 [−0.05, 0.16] | .290 | 0.03 [−0.07, 0.12] | .591 | −0.01 [−0.52, 0.50] | .969 |

| Treatment adaptation | ||||||

| For MBIs | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.06] | .844 | −0.02 [−0.08, 0.03] | .404 | 0.04 [−0.24, 0.32] | .789 |

| For controls | 0.06 [−0.00, 0.13] | .059 | 0.03 [−0.09, 0.09] | .302 | 0.23 [−0.10, 0.57] | .175 |

| Individual treatment format | 0.00 [−0.11, 0.17] | .949 | 0.00 [−0.10, 0.10] | .960 | 0.22 [−0.32, 0.76] | .416 |

| Clinician factors | ||||||

| Clinician training | ||||||

| MBI training | −0.03 [−0.11, 0.05] | .474 | −0.00 [−0.07, 0.07] | .904 | −0.23 [−0.56, 0.10] | .175 |

| Control training | −0.05 [−0.12, 0.02] | .155 | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.06] | .838 | −0.34 [−0.63, −0.04] | .026* |

| Study design factors | ||||||

| Recruitment settings | ||||||

| Clinical | 0.07 [0.01, 0.13] | .022* | 0.04 [−0.01, 0.09] | .127 | 0.08 [−0.18, 0.35] | .547 |

| Non-clinical | −0.10 [−0.17, −0.04] | .002** | −0.07 [−0.13, −0.01] | .018* | −0.15 [−0.51, 0.22] | .428 |

| Both | 0.00 [−0.06, 0.07] | .920 | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.05] | .765 | 0.06 [−0.22, 0.34] | .692 |

| Publication year | −0.01 [−0.01, 0.00] | .264 | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.00] | .057 | 0.03 [−0.02, 0.07] | .234 |

Note. MBIb = meta-regression coefficient for overall attrition in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs); MBIp = p-value of moderator test for MBIs; Controlb = meta-regression coefficient for overall attrition in active controls; Controlp = p-value of moderator test for controls; Differentialh = meta-regression coefficient for differential attrition; Differentialp = p-value of moderator test for differential attrition; Percentage REM = percentage of sample identified as racial/ethnic minorities; Some college = percentage with some college or more education; Country = geographic location where recruitment occurred; # = number; MBSR = mindfulness-based stress reduction; MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MORE = mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement; MBCR = mindfulness-based cancer recovery; MBRP = mindfulness-based relapse prevention; Specific active control type = whether active control was intended to be therapeutic; Treatment adaptation = whether the treatment was adapted for specific population (i.e., included content targeted to that population); Recruitment settings = whether recruitment occurred in clinical (e.g., hospital), non-clinical (e.g., community), or both.

p < .050

p < .010

p < .001

Given the importance of proper handling of missing data for producing unbiased and efficient estimates of treatment effects (Graham, 2009), we also coded how missing data were handled by study authors (e.g., completer analyses, multiple imputation, etc.). This was coded for descriptive purposes only (i.e., not tested as a moderator of treatment effects). We also coded treatment completion rates and definitions of treatment completion for descriptive purposes.

Summary Measures

We calculated the overall meta-analytically weighted average attrition (i.e., meta-analysis of proportions) for MBI and control groups. To examine differential attrition, ORs were computed to estimate the likelihood of dropout from the MBI conditions relative to the control (Cooper et al., 2009).

Synthesis of Results

Standard meta-analytic methods were adopted (Cooper et al., 2009) to compute overall (i.e., meta-analysis of proportions) and differential attrition. Overall attrition was computed as the ratio between dropout and ITT sample sizes and was calculated for MBIs and control conditions separately:

| (Equation 1) |

The variance of overall attrition rate was computed using standard methods (Cohen et al., 2003):

| (Equation 2) |

Differential attrition was calculated as an odds ratio (i.e., odds of dropout in MBI relative to control) using the following formula (Borenstein et al., 2009):

| (Equation 3) |

| (Equation 4) |

An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates that attrition rates were higher in MBIs than controls. The odds ratios were converted into log odds for use in analyses (Borenstein et al., 2009). To allow inclusion of studies with no attrition, a continuity correction of 0.5 was added to all cells when no attrition was observed for MBIs and/or controls (Sweeting et al., 2004).

Random effects models with inverse variance weighting were implemented using the ‘metafor’ package (Viechtbauer, 2010) in R (R Core Team, 2021). For differential attrition, Peto’s method and Mantel-Haenszel’s method were used as sensitivity analyses and conducted without the continuity correction applied (Higgins & Thomas, 2019). Heterogeneity was characterized using I2 which represents the proportion of variance in effect sizes due to between-study differences (Higgins et al., 2003). Exploratory moderator analyses were conducted to examine potential sources of heterogeneity.

Risk of bias across studies

We conducted trim-and-fill analyses to assess the potential impact of publication bias (e.g., unpublished trials, trials published in non-English language journals). The “file drawer problem” occurs when meta-analytic results fail to include unpublished primary studies due to insignificant findings (Sutton, 2009). Trim-and-fill analyses aim to correct funnel plot asymmetry arising from publication bias (e.g., underpowered studies; Duval et al., 2000). This is done by imputing studies that would create symmetry around the observed omnibus effect. We also examined contour-enhanced funnel plots which allow evaluation of funnel plot asymmetry in combination with statistical significance of the observed effects (Peters et al., 2008). This is designed to aid in interpreting whether missing studies were due to publication bias. For differential attrition, we also conducted the Harbord test (Harbord et al., 2006), which is a funnel plot asymmetry test designed for binary outcome data with rare events. This was conducted using the ‘regtest’ function with Peto’s method in the ‘metafor’ package (Viechtbauer, 2010).

Additional analyses

As identified in our preregistration, four categories of study characteristics were included in our exploratory moderator analyses. They were selected based on prior theoretical and empirical literature (Baer et al., 2019; Goldberg et al., 2020; Khoury et al., 2013) as well as what was reported most consistently across the included studies. As noted above, these included ten demographic and population-related variables, five program factors, one clinician factor, and two study design factors (Table 2). For categorical variables with multiple levels (e.g., country), we created dummy codes for the contrasts of interest (e.g., North America vs. other regions, Asia vs. other regions). However, given the likely underpowered nature of these analysis and the risk of Type I error given the number of tests conducted, these examinations were very intentionally exploratory in nature, should be interpreted cautiously, and replicated in future studies.

Standard meta-analytic methods were adopted (Cooper, et al., 2009) to test for outliers (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010; Harrer et al., 2019). Specifically, we used the ‘find.outliers’ function (Cuijpers et al., 2020) in R as a sensitivity analysis to assess the degree to which patterns were driven by outliers. Outliers were defined as studies whose confidence interval does not overlap the omnibus effect confidence interval (Harrer et al., 2019).

Results

Study Selection

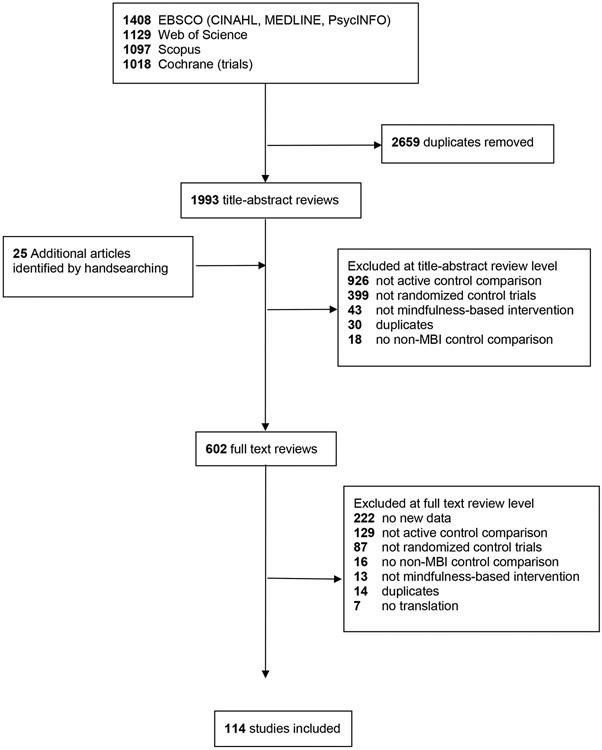

The search yielded 4,652 citations. We removed 2,659 duplicates and evaluated the remaining 1,993 studies titles and/or abstracts based on the inclusion criteria. The screening resulted in 602 studies for full-text eligibility review (Figure 1). After applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria, 114 studies were retained, representing 11,288 participants.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 114 included studies are available as supplemental data (https://osf.io/c3u7a/). Studies were published between 2007 and 2021. Most studies occurred in North America (65.79%), although studies also occurred in Europe (16.67%), Asia (7.89%), the Middle East (4.39%), South America (1.75%) or across multiple regions (3.51%). Participants were on average 45.49 years old (SD = 14.87), 64.74% female, and 34.45% racial/ethnic minorities. Racial/ethnic minority status was defined relative to the majority population in the country where the primary study was conducted. Samples primarily included individuals with medical (38.60%) or psychiatric conditions (34.21%), with 27.19% drawn from non-clinical populations. A small percentage (7.02%) were military veterans. Recruitment most commonly occurred in clinical settings (37.71%) or a combination of clinical and non-clinical settings (27.90%).

MBIs were most commonly based on MBSR (59.65%), with 29.82% based on MBCT, 5.26% on MBRP, 4.39% on MORE, 0.88% on MBCR. Among the control interventions, most (92.11%) were specific active controls (i.e., intended to be therapeutic; Wampold et al., 1997), while 7.89% studies were non-specific active controls. The most common control comparisons were various psychotherapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, relapse prevention; 42.20%), psychoeducation (34.86%), support groups (9.17%), progressive muscle relaxation (5.50%), and physical exercise (3.67%). Most MBIs and controls were adapted to the study population (70.18% and 76.32%, respectively) and took place in a group format (92.98%). The average duration of MBIs was 8.47 weeks (SD = 2.21, range = 4 to 22) and 8.86 sessions (SD = 2.30, range = 1 to 20). The average duration of control conditions was 8.61 weeks (SD = 2.29, range = 4 to 22) and 8.86 sessions (SD = 2.30, range = 1 to 20). Those delivering either the MBI or control condition typically had specialized training to do so (83.49% and 77.98%, respectively).

Most studies (57.89%) employed intention-to-treat analyses (i.e., analyzing data from all randomized participants) although 42.11% analyzed completers only. Within the 66 studies that included intention-to-treat analyses, most handled missing data using maximum likelihood (66.67%), with 18.18% using multiple imputation, 13.63% carrying the last observation forward, and 1.52% using single imputation.

Only a minority of studies (31.58%) clearly defined and reported MBI and control treatment completion. Among those that reported a definition of completion, the most common definition was completing 50% or more of the treatment sessions (k = 19 studies used this definition). Other definitions included completing 55% or more of sessions (k = 3), 75% or more of sessions (k = 8) or completion of all sessions (k = 1). Approximately half (58.71%) of studies reported the number of treatment refusers (i.e., dropouts prior to attending the first treatment session). On average, 10.46% (SD = 12.44) MBI participants and 10.61% (SD = 12.94) control participants did not attend the first session of their respective conditions.

Results of individual studies

Study-level overall and differential attrition rates are reported in Supplemental Materials Table 2 and Supplemental Materials Figure 2.

Synthesis of results

Attrition rate.

The weighted average attrition for MBIs was 19.1%, 95% CI [.16, .22] in MBIs and 18.6% [.16, .21] in controls (Table 1). Both models showed very high heterogeneity (I2 = 94.69% and 91.76%, respectively). Differential attrition did not differ from zero (log OR = 0.05, [−0.08, 0.18], OR = 1.05, [0.92, 1.19]) indicating that attrition rates were similar across MBIs and controls. Heterogeneity was low to moderate in this model (I2= 28.01%). However, differential attrition did differ from zero when using Peto’s method (log OR = 0.099, [0.0006, 0.20], OR = 1.10, [1.0006, 1.22], p = .049) and Mantel-Haenszel’s method (log OR = 0.097, [0.0002, 0.19], OR = 1.10, [1.0002, 1.21], p = .050).

Table 1.

Meta-analytic estimates of overall and differential attrition

| Model | k | ES 95% CI | I2 95% CI | kimp | ESadj 95% CI | ESoutlier 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBIs | 114 | 0.19 [0.16, 0.22] | 94.69 [93.00, 96.08] | 0 | 0.19 [0.16, 0.22] | 0.18 [0.17, 0.20] |

| Control | 114 | 0.19 [0.16, 0.21] | 91.76 [89.07, 94.05] | 0 | 0.19 [0.16, 0.21] | 0.18 [0.16, 0.20] |

| Differential | 114 | 0.05 [−0.08, 0.18] | 28.01 [8.12, 51.16] | 22 | 0.23 [0.08, 0.37] | 0.11 [0.00, 0.22] |

Note: k = number of studies; MBI = overall attrition in mindfulness-based interventions; Control = overall attrition in active controls; Differential = differential attrition in MBIs relative to controls; ES = effect size in percentage units for MBI and Control models and log odds ratio for Differential model; CI = confidence interval; I2 = heterogeneity; kimp = number of imputed studies necessary for funnel plot symmetry; ESadj = trim-and-fill adjusted effect size; koutlier = number of outliers; ESoutlier = effect size after removing outliers

Risk of bias across studies

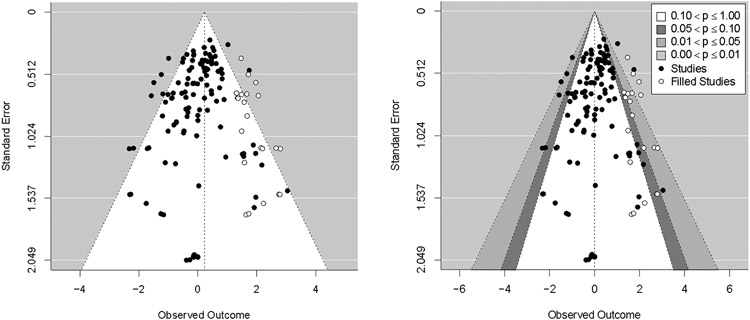

Trim-and-fill analyses did not detect funnel plot asymmetry for the overall attrition models. A trim-and-fill analysis did detect funnel plot asymmetry for the differential attrition model (Figure 1) as did the Harbord test (z = −3.72, p < .001). After imputing 22 studies to the right of the observed overall effect (i.e., missing studies showing higher attrition in MBIs vs. controls), a significant log OR was detected (log OR = 0.23, [0.08, 0.37]). This effect is equivalent to an odds ratio of 1.25, indicating that participants randomized to the MBI conditions were 25% more likely to drop out than controls.

Despite evidence for funnel plot asymmetry in these regression-based tests (Viechtbauer, 2010), a contour-enhanced funnel plot (Peters et al., 2008) for differential attrition did not indicate an absence of missing studies in areas of statistical non-significance (Figure 2). This decreases confidence in the notion that asymmetry is due to publication bias. Contour-enhanced funnel plots for overall attrition similarly did not show an absence of missing studies in areas of statistical non-significance (Supplemental Materials Figure 2).

Figure 2. Funnel plot depicting results of trim-and-fill adjustment for the differential attrition model.

Note. Left panel shows trim-and-fill adjusted funnel plot with points imputed on the right side of the plot to account for asymmetry. Right panel shows contour-enhanced trim-and-fill adjusted funnel plot. Note that the location of imputed studies does not appear to be associated with regions of statistical non-significance, suggesting that asymmetry is not due to publication bias.

Additional Analyses

Results of the exploratory moderator tests are presented in Table 2. Although 18 characteristics across four categories of study features (program factors, clinician factors, participant factors, and study design) were tested as moderators of both overall and differential attrition, very few significant moderator effects were detected.

Among participant factors, higher age was associated with greater likelihood of overall attrition in controls (B = −0.002, p = .005). The remaining participant characteristics (racial/ethnic minority status, gender, marital status, education, medical population, psychiatric population, non-clinical population, veteran status, country of origin) were not associated with overall or differential attrition. None of the program factors (number of sessions, MBI type, control type, treatment format, treatment adaptation) were associated with overall or differential attrition, with the exception of MBRP which was associated with higher overall attrition for control participants (B = 0.13, p = .019). Among clinician factors, having trained facilitators for the control condition was associated with lower differential attrition (B = −0.34, p = .026). Among study design factors, recruitment through a clinical setting was associated with higher overall attrition in MBIs (B = 0.07, p = .022) and recruitment through a non-clinical setting was associated with lower overall attrition in MBIs and controls (Bs = −0.10 and −0.070, ps = .002 and .018, respectively). Publication year was not significant predictor in any model.

Lastly, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with outliers removed. Although a large number of outliers were detected for both overall attrition models (ks = 49 and 33, for MBIs and control, respectively), the estimates of overall attrition were largely unchanged with their omission (18% and 18%, for MBIs and control, respectively). However, when seven outliers were removed from the differential attrition model, the previously non-significant effect size became significant (log OR = 0.11, [0.00, 0.22], p = .047). This effect size is equivalent to an odds ratio of 1.11, indicating that after removing outliers, participants randomized to MBIs were 11% more likely to drop out than control participants.

Discussion

Despite growing interest and promising results in the application of MBIs in clinical and non-clinical populations, no comprehensive meta-analysis has quantified overall or differential attrition in RCTs of MBIs relative to structure and intensity matched control conditions. Robust estimates of attrition rates and a thorough understanding of factors likely to influence attrition for these interventions can guide clinical trialists’ study planning and treatment developers’ and clinicians’ efforts to increase the acceptability of MBIs. We meta-analyzed a sample of 114 RCTs (n = 11,288) comparing MBIs with matched control conditions. In comparison with the two recent meta-analysis that evaluated the differential attrition of MBIs in small subsets of the literature (i.e., veterans and people of color; Goldberg et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021) and provided mixed results regarding the possibility of higher attrition in MBIs versus controls, the current study was designed to provide a comprehensive depiction of attrition and its correlates. Studies were conducted around the world and included a wide range of clinical and non-clinical populations.

Very similar to estimates of attrition derived from psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy generally (i.e., 19.7% to 21.9%; Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Swift et al., 2017), approximately one in five participants randomized to an MBI or control condition did not complete post-treatment assessments (19.1% and 18.6%, respectively). We found no evidence of differential attrition in our primary analysis (log OR = 0.05). However, evidence for differential attrition was detected in several sensitivity analyses, including a trim-and-fill adjusted analysis, models using estimation methods designed for rare events data (Peto’s and Mantel-Haenszel’s methods), and when outliers were removed. In all cases, we found evidence of higher attrition in MBIs relative to controls. Odds ratios for these sensitivity analyses ranged from 1.10 to 1.25. Although these effect sizes are small (i.e., OR < 1.68; Chen et al., 2010), consistent with Goldberg et al.’s (2020) meta-analysis with veterans, they nonetheless raise the important possibility that MBIs may be less acceptable than control conditions.

As the sensitivity analyses led to different conclusions regarding the acceptability of MBIs vis-à-vis controls, it is important to consider these analyses further, especially the sources of bias they are designed to address. In theory, the trim-and-fill analysis adjusts for publication bias, in this specific case an under-representation of studies showing higher attrition in MBIs. It is certainly possible that studies showing higher attrition in MBIs vs. control conditions are less likely to be published, perhaps if these same studies also show weaker effects for MBIs vs. controls on primary outcomes. In addition, authors of studies where attrition was higher in MBIs vs. controls may be less likely to report attrition data (i.e., the study may have been published but without a clear reporting of study attrition). At once, these possibilities may be less plausible than the typical scenario in which null or negative findings related to a primary outcome (e.g., change in symptoms for MBIs vs. control) result in a study being unpublished and the results of the control-enhanced funnel plot also did not suggest a publication bias mechanism.

Interestingly, the same pattern—MBIs showing higher attrition than controls—emerges when using estimation methods designed to handle rare events (Peto’s and Mantel-Haenszel’s methods) and when excluding studies whose confidence intervals did not overlap the omnibus effect size confidence interval. Unlike the trim-and-fill analysis, these sensitivity analyses were intended to rule out undue influence of rare events and outlying studies. The fact that these analyses mirrored conclusions from the trim-and-fill analysis supports the possibility that MBIs may be modestly less acceptable than matched control conditions. Taken together, it may be prudent for MBI developers and clinicians delivering MBIs to more thoroughly investigate and address the possibility that MBIs are less acceptable than controls. In particular, it would be worth exploring factors that influence the acceptability of MBIs and, when possible, modifying aspects of the treatment that may increase attrition.

Unfortunately, although we tested many exploratory moderators of both overall and differential attrition, we found very few clues for what study characteristics may account for higher attrition. The only moderator that emerged across multiple models was recruitment setting. Specifically, studies recruiting through non-clinical settings were associated with lower overall attrition in both MBIs and control conditions. One possible explanation for this could be that non-clinical populations face fewer barriers to engaging in an MBI or control condition than a clinical population (e.g., whose lives may be complicated due to their clinical condition). Participants recruited from clinical settings (e.g., hospitals, doctor referral, clinics) may also have lower intrinsic motivation (e.g., enrolled due to external pressure from referrals; Alfonssonet al., 2016; Ryan et al., 2006) for participation than non-clinical settings. The only variable associated with differential attrition was training for the control condition facilitators. Specifically, differential attrition was lower when control condition facilitators were trained (e.g., had clinical training or credentials). Younger age and percentage married were also associated with lower overall attrition in control conditions, which are two of the few factors previously shown to predict attrition in psychotherapy generally (Swift & Greenberg, 2012) that was replicated in our meta-analysis. We also did not replicate the findings that veterans have higher rates of attrition in MBIs than control interventions (Goldberg et al., 2020). This may be due to the low number of veterans in the current sample. The other reason could be the over-representation of present-centered therapy for PTSD in the previous meta-analysis which is known to have lower dropout rates than other evidence-based treatments for PTSD (Frost et al., 2014).

Of course, given the number of moderator tests that were conducted, the few statistically significant results that were detected should be treated extremely cautiously. A large number of tests were conducted as it seemed important to explore many candidate characteristics, but the risk for Type I error is certainly inflated with these underpowered multiple subgroup analyses. Nonetheless, we believed that the current exploratory moderator analyses were worthwhile to report as an attempt to thoroughly investigate potentially relevant moderators identified by prior theoretical and empirical literature (Baer et al., 2019; Goldberg et al., 2020; Khoury et al., 2013). After exploring this wide variety of study level characteristics (program factors, clinician factors, participant factors, and study design), it is notable that so few moderators were significantly related to attrition. Additionally, it is worth noting that none of the significant effects survive a Bonferroni p-value correction which would result in a revised p-value threshold of .002 (i.e., .050 divided by the 32 coefficients reported for each outcome type; Dunn, 1961). This further highlights the highly tentative nature of the few significant moderators and further supports the notion that we currently no very little about what factors are associated with elevated attrition from MBIs.

The high heterogeneity in the overall attrition models (I2 > 91%) and the smaller but nonetheless statistically significant heterogeneity in the differential attrition models (I2 = 28.01%, Q[113] = 158.98, p = .003) suggests that meaningful variability exists, albeit variability we were unable to predict with the available moderators. There are likely important factors that do indeed predict overall and differential attrition but that could not be coded reliably. Theoretically relevant factors that we could not assess from the available literature include participant compensation, quality of the MBI and control conditions, socioeconomic status (beyond what was captured with education), and other implementation-related variables (e.g., adaptation of intervention for certain settings).

Beyond estimates of overall and differential attrition, one descriptive result worth highlighting is the treatment of missing data. Somewhat discouraging, we saw that over 40% of studies did not conduct ITT analyses but relied on analysis of complete cases only. This practice is problematic and can lead to biases in parameter estimates and reduced statistical power (Graham, 2009). More encouraging, the majority of studies that did conduct intention-to-treat analyses used modern methods for handling missingness that are robust to data that are missing at random (i.e., maximum likelihood, multiple imputation; Graham, 2009). We hope our documentation of substantial study attrition within RCTs of MBIs (i.e., well above the 5% benchmark for ignorability; Graham, 2009) sensitizes researchers to the importance of handling missing data using appropriate statistical techniques.

There are several notable limitations. As is always the case for meta-analysis, we were limited by the available literature. Authors of the included studies often did not report rates of treatment completion and those that did report treatment completion defined it in inconsistent ways (e.g., 50% to 100% of sessions attended). Our analyses instead focused on study attrition (as has been done previously; Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Khoury et al., 2013; Nam et al., 2016;) which, in the context of an RCT, can still provide estimates of relative treatment acceptability. Nonetheless, it would have been valuable to examine rates of treatment dropout using a standardized metric. In addition, authors did not consistently report comparisons between those who dropped out versus remained in the treatment or study, which precluded our ability to compare these groups meta-analytically (as was done by Swift et al., 2012). Similarly, the lack of standardized reporting of potential moderators of interest (e.g., socioeconomic status) limited our ability to test them as predictors of attrition.

Although we included a large number of studies and participants, the moderator tests in particular may have been underpowered to detect small or very small effects (Hedges & Pigott, 2004). To get a rough estimate of statistical power to test moderators, we assessed power post hoc using the observed sample sizes, number of studies, and heterogeneity (I2) and the ‘subgroup_power’ function in the ‘metapower’ package (Griffin, 2020). Assuming a two-group comparison (e.g., MBSR vs. other MBIs), we were adequately powered (power = .80) to detect moderate-to-large between-group differences for overall attrition in MBIs (d = 0.66, when group 1 d = 0.20 and group 2 d = 0.86), moderate between-group differences for overall attrition in active control conditions (d = 0.52, when group 1 d = 0.20 and group 2 d = 0.72), and small-to-very-small between-group differences for differential attrition (d = 0.12, when group 1 d = 0.20 and group 2 d = 0.32). Thus, it seems moderator tests were particularly low powered for overall attrition but may have been adequately powered for differential attrition.

A final limitation was that we focused exclusively on RCTs. This provides internal validity for our tests of differential attrition in particular. However, this comes at a cost to external validity. Results may or may not generalize to the implementation of MBIs in naturalistic settings. In the current study, we are unable to disentangle the potential impact of involvement in an RCT versus involvement with an MBI or control condition on attrition.

There are several specific future directions that follow from our results. As noted, it would be valuable for the field to agree on a standardized definition of treatment completion and to report treatment completion routinely. The most common metric used in the included studies (i.e., completion of 50% of treatment sessions) may be a reasonable candidate. At once, future work may be necessary to evaluate the implications of various definitions of treatment completion (Warnick et al., 2012). Given that approximately 20% of participants drop out of MBI RCTs, it would be valuable to identify and ultimately modify malleable factors to increase the acceptability of MBIs, control conditions, and/or the RCTs in which they are being tested. This might include cultural adaptation which has been shown to improve psychotherapy outcomes generally (Benish et al., 2011) but is lacking from the MBI literature (Sun et al., 2021). Other potentially modifiable factors worthy of further study that might make MBIs less acceptable than controls are adverse effects associated with meditation practice itself (Britton et al., 2021; Goldberg et al., 2021b), difficulty understanding and engaging with mindfulness practices (Martinez et al., 2015; Pigeon et al., 2015), and a lack of trauma sensitivity (Treleaven, 2018). Perhaps the most promising future direction for identifying predictors of attrition is individual patient data meta-analysis (e.g., Kuyken et al., 2016). By pooling data across studies, researchers can maintain high statistical power while examining patient-level (rather than study-level) variables.

In conclusion, our results indicate that, similar to other forms of psychotherapy, approximately one in five participants in MBI RCTs drop out. This figure, paired with some evidence that MBIs may be less acceptable than control conditions, highlights the importance of investigating factors to increase the acceptability of MBIs and to identify instances were MBIs may or may not be recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AT010879. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was preregistered through the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/c3u7a/).

References

- Alfonsson S, Olsson E, & Hursti T (2016). Motivation and treatment credibility predicts dropout, treatment adherence, and clinical outcomes in an internet-based cognitive behavioral relaxation program: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(3), e52. 10.2196/jmir.5352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R, Crane C, Miller E, & Kuyken W (2019). Doing no harm in mindfulness-based programs: Conceptual issues and empirical findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 71, 101–114. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Kenward MG, Fairclough DL, & Horton NJ (2013). Differential dropout and bias in randomised controlled trials: When it matters and when it may not. BMJ, 346(Jan 21), e8668. 10.1136/bmj.e8668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, & Wampold BE (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 279–289. 10.1037/a0023626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk T, Björck C, Clinton D, Sohlberg S, & Norring C (2009). What happened to the ones who dropped out? Outcome in eating disorder patients who complete or prematurely terminate treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(2), 109–119. 10.1002/erv.911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Mallik S, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Johnson HE, Deleone CM, Minnix-Cotton CA, Byrne SA, Kober H, Weinstein AJ, Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2011). Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 119(1–2), 72–80. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, Michalsen RN, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Grier A, Bergquist KL, Reis DL, Potenza MN, Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2009). Mindfulness training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: Results from a randomized, controlled stage I pilot study. Substance Abuse, 30(4), 306–317. 10.1080/08897070903250241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Lindahl JR, Cooper DJ, Canby NK, & Palitsky R (2021). Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 216770262199634. 10.1177/2167702621996340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE (2013). Mindfulness-based cancer recovery: The development of an evidence-based psychosocial oncology intervention. Oncology Exchange, 12(2), 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J, Faris P, Tamagawa R, Drysdale E, & Speca M (2013). Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery Versus Supportive Expressive Group Therapy for Distressed Survivors of Breast Cancer (MINDSET). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(25), 3119–3126. 10.1200/jco.2012.47.5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, & Chen S (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864. 10.1080/03610911003650383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AA, & Conklin LR (2015). Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 57–65. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (Eds.). (2019). The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Corning AF, & Malofeeva EV (2004). The application of survival analysis to the study of psychotherapy termination. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(3), 354–367. 10.1037/0022-0167.51.3.354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen R, Viechtbauer W, Spigt M, & Kotz D (2014). Differential attrition in health behaviour change trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology & Health, 30(1), 122–134. 10.1080/08870446.2014.953526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn OJ (1961). Multiple comparisons among means. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 56(293), 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, & Tweedie R (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocco AJ, Mallya S, Farzaneh M, & Koszycki D (2018). Exploring the benefits of mindfulness training in healthy community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled study using a mixed methods approach. Mindfulness, 10(4), 737–748. 10.1007/s12671-018-1041-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost ND, Laska KM, & Wampold BE (2014). The evidence for present-centered therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(1), 1–8. 10.1002/jts.21881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, Griffith L, Oremus M, Raina P, Ismaila A, Santaguida P, Lau J, & Trikalinos TA (2011). Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(11), 1187–1197. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galante J, Friedrich C, Dawson AF, Modrego-Alarcón M, Gebbing P, Delgado-Suárez I, Gupta R, Dean L, Dalgleish T, White IR, & Jones PB (2021). Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLOS Medicine, 18(1), e1003481. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Boettiger CA, & Howard MO (2010). Mindfulness training modifies cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms implicated in alcohol dependence: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 42(2), 177–192. 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Bolt DM, & Davidson RJ (2021). Data missing not at random in mobile health research: Assessment of the problem and a case for sensitivity analyses. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e26749. 10.2196/26749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Lam SU, Britton WB, & Davidson RJ (2021). Prevalence of meditation-related adverse effects in a population-based sample in the United States. Psychotherapy Research, 1–15. 10.1080/10503307.2021.1933646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Riordan KM, Sun S, & Davidson RJ (2021). The empirical status of mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review of 44 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 174569162096877. 10.1177/1745691620968771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Riordan KM, Sun S, Kearney DJ, & Simpson TL (2020). Efficacy and acceptability of mindfulness-based interventions for military veterans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 138, 110232. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Davidson RJ, Wampold BE, Kearney DJ, & Simpson TL (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 549–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JW (2020). metapoweR: An R package for computing meta-analytic statistical power. R package version 0.2.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=metapower [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Collins LM, Malotte CK, Johnson CA, & Fielding JE (1985). Attrition in prevention research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(3), 261–275. 10.1007/bf00870313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbord RM, Egger M, & Sterne JAC (2006). A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in Medicine, 25(20), 3443–3457. 10.1002/sim.2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, & Ebert DD (2021). Doing meta-analysis with r: A hands-on guide (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. 10.1201/9781003107347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. 10.1016/s0005-7894(04)80013-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, & Hofmann SG (2017). The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 245–246. 10.1002/wps.20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, & Pigott TD (2004). The power of statistical tests for moderators in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 426–445. 10.1037/1082-989x.9.4.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry NW, Cohen J, & Cohen P (1977). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Contemporary Sociology, 6(3), 320. 10.2307/2064799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Thomas J (2019). Cochrane handbooks for systematic reviews of interventions (Second ed.). Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, & Sterne JAC (2008). On behalf of the Cochrane statistical methods group and the Cochrane bias methods group (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version, 5(0). www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- J. Sweeting M, J. Sutton A, & C. Lambert P (2004). What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Statistics in Medicine, 23(9), 1351–1375. 10.1002/sim.1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo EL, Small R, Cheng W, Hatchard T, Glynn B, Rice DB, Skidmore B, Kenny S, Hutton B, & Poulin PA (2019). Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evidence Based Mental Health, 22(1), 26–35. 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, Chapleau MA, Paquin K, & Hofmann SG (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, Whalley B, Crane C, Bondolfi G, Hayes R, Huijbers M, Ma H, Schweizer S, Segal Z, Speckens A, Teasdale JD, van Heeringen K, Williams M, Byford S, Byng R, & Dalgleish T (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D, van den Berg NH, & Mendrek A (2021). Adverse effects of meditation: A review of observational, experimental and case studies. Current Psychology. 10.1007/s12144-021-01503-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Kearney DJ, Simpson T, Felleman BI, Bernardi N, & Sayre G (2015). Challenges to enrollment and participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction among veterans: a qualitative study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(7), 409–421. 10.1089/acm.2014.0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morone NE, Rollman BL, Moore CG, Li Q, & Weiner DK (2009). A mind–body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: Results of a pilot study. Pain Medicine, 10(8), 1395–1407. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00746.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam S, & Toneatto T (2016). The influence of attrition in evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(6), 969–981. 10.1007/s11469-016-9667-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newell DJ (1992). Intention-to-treat analysis: Implications for quantitative and qualitative research. International Journal of Epidemiology, 21(5), 837–841. 10.1093/ije/21.5.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A (2013). Interpretation of odds and risk ratios. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 27(3), 600–603. 10.1111/jvim.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, & Rushton L (2008). Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(10), 991–996. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigeon W, Allen C, Possemato K, Bergen-Cico D, & Treatman S (2014). Feasibility and acceptability of a brief mindfulness program for veterans in primary care with posttraumatic stress disorder. Mindfulness, 6(5), 986–995. 10.1007/s12671-014-0340-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power MJ, & Freeman C (2012). A randomized controlled trial of IPT versus CBT in primary care: With some cautionary notes about handling missing values in clinical trials. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(2), 159–169. 10.1002/cpp.1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch HL, Rosario M, Levison LM, Olivera A, Livingston WS, Wu T, & Gill JM (2018). The effect of mindfulness meditation on sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1445(1), 5–16. 10.1111/nyas.13996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Patrick H, & Williams GC (2008). Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on self-determination theory. The European Health Psychologist, 10(1), 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Imel ZE, Ludman EJ, & Steinfeld BJ (2012). Is dropout after a first psychotherapy visit always a bad outcome? Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 705–707. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, & Tierney JF (2015). Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA, 313(16), 1657. 10.1001/jama.2015.3656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Goldberg SB, Loucks EB, & Brewer JA (2021). Mindfulness-based interventions among people of color: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 1–14. 10.1080/10503307.2021.1937369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, & Greenberg RP (2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 547–559. 10.1037/a0028226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, Greenberg RP, Tompkins KA, & Parkin SR (2017). Treatment refusal and premature termination in psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination: A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Psychotherapy, 54(1), 47–57. 10.1037/pst0000104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, McKay D, Forman EM, Klonsky ED, & Thombs BD (2015). Empirically supported treatment: Recommendations for a new model. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22(4), 317–338. 10.1037/h0101729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treleaven DA (2018). Trauma-sensitive mindfulness: practices for safe and transformative healing (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W, & Cheung MWL (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112–125. 10.1002/jrsm.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick EM, Gonzalez A, Robin Weersing V, Scahill L, & Woolston J (2011). Defining dropout from youth psychotherapy: How definitions shape the prevalence and predictors of attrition. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(2), 76–85. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.