Abstract

We cloned two novel Trypanosoma cruzi proteins by using degenerate oligonucleotide primers prepared against conserved domains in mammalian serine/threonine protein phosphatases 1, 2A, and 2B. The isolated genes encoded proteins of 323 and 330 amino acids, respectively, that were more homologous to the catalytic subunit of human protein phosphatase 1 than to those of human protein phosphatase 2A or 2B. The proteins encoded by these genes have been tentatively designated TcPP1α and TcPP1β. Northern blot analysis revealed the presence of a major 2.3-kb mRNA transcript hybridizing to each gene in both the epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote developmental stages. Southern blot analysis suggests that each protein phosphatase 1 gene is present as a single copy in the T. cruzi genome. The complete coding region for TcPP1β was expressed in Escherichia coli by using a vector, pTACTAC, with the trp-lac hybrid promoter. The recombinant protein from the TcPP1β construct displayed phosphatase activity toward phosphorylase a, and this activity was preferentially inhibited by calyculin A (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], ∼2 nM) over okadaic acid (IC50, ∼100 nM). Calyculin A, but not okadaic acid, had profound effects on the in vitro replication and morphology of T. cruzi epimastigotes. Low concentrations of calyculin A (1 to 10 nM) caused growth arrest. Electron microscopic studies of the calyculin A-treated epimastigotes revealed that the organisms underwent duplication of organelles, including the flagellum, kinetoplast, and nucleus, but were incapable of completing cell division. At concentrations higher than 10 nM, or upon prolonged incubation at lower concentrations, the epimastigotes lost their characteristic elongated spindle shape and had a more rounded morphology. Okadaic acid at concentrations up to 1 μM did not result in growth arrest or morphological alterations to T. cruzi epimastigotes. Calyculin A, but not okadaic acid, was also a potent inhibitor of the dephosphorylation of 32P-labeled phosphorylase a by T. cruzi epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigote extracts. These inhibitor studies suggest that in T. cruzi, type 1 protein phosphatases are important for the completion of cell division and for the maintenance of cell shape.

Trypanosoma cruzi, a hemoflagellate and the causative agent of Chagas' disease, has a complex life cycle involving four major morphogenetic stages (24). The epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote are insect-specific stages, whereas the trypomastigote and amastigote are mammalian host-specific extracellular and intracellular stages, respectively. Each developmental stage can be distinguished morphologically, and there are also stage-specific differences in surface and intracellular components (2, 7). The molecular mechanisms involved in the various stage-specific transformations, however, remain ill defined. In higher eukaryotes, the reversible phosphorylation of proteins on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues plays a key role in the integration of the signals involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation (5, 7). It is possible that similar regulatory pathways also exist in T. cruzi and are involved in the various developmental transformations. However, information concerning such pathways is limited. Cyclic AMP, an important second messenger in higher eukaryotes, has been reported to be involved both in epimastogote-to-metacyclic trypomastigote transformation within the insect vector (13) and in the control of proliferation and differentiation of amastigotes (9). Several serine/threonine protein kinases, including protein kinase A (20, 26), protein kinase C (12), and a calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (21), have been detected in T. cruzi epimastigotes. However, information on serine/threonine protein phosphatases in this organism is limited.

Four major classes of protein phosphatases have been identified in eukaryotic cells: protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), PP2A, PP2B, and PP2C (3, 6). This classification is based on the use of specific activators and inhibitors, substrate specificity, and divalent cation requirements of these enzymes. Subsequent amino acid and cDNA sequencing studies have revealed that PP1, PP2A, and PP2B are members of the same gene superfamily, termed the PPP family. PP2C is structurally and mechanistically unrelated to the PPP family and has been classified as a member of the PPM family of Mg2+-dependent protein phosphatases.

In this paper, we provide evidence for a critical role for PP1-like phosphatases in the T. cruzi life cycle. Two protein phosphatase genes from T. cruzi have been isolated by homology cloning. The encoded proteins, designated TcPP1α and TcPP1β, were found to be more homologous to human PP1 than to human PP2A or PP2B. The availability of highly specific inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A has provided the opportunity to investigate the role of these enzymes in cellular processes (11, 15, 16, 28). Okadaic acid is a potent inhibitor of PP2A (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] = 2 nM), whereas higher concentrations are necessary for inhibition of PP1 (IC50 = 60 to 200 nM) and PP2B (IC50 = 10 mM). PP2C is unaffected by okadaic acid. In contrast, calyculin A inhibits both PP1 and PP2A, but not PP2B or PP2C, with high potency (IC50 = 0.5 to 1 nM). Calyculin A, but not okadaic acid, had marked effects on T. cruzi epimastigote growth and morphology. In the presence of low concentrations of calyculin A (1 to 10 nM), epimastigotes underwent growth arrest. Microscopic studies indicated that the calyculin A-treated epimastigotes had undergone flagellar duplication and both kinetoplast and nuclear divisions but were incapable of successfully completing cytokinesis. Calyculin-treated cells also lost their characteristic elongate, spindle-shaped trypanosome morphology and adopted a more rounded morphology. Our studies suggest that in T. cruzi, PP1-like phosphatases are important for the completion of cell division and the maintenance of cell shape.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote culture conditions.

T. cruzi epimastigotes were grown at 26°C in liver infusion tryptose broth supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (GIBCO BRL) (2, 3). T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes (HO 3/15), kindly provided by James Dvorak (National Institutes of Health), were produced by allowing epimastigote cultures to reach stationary phase as described elsewhere (19). Metacyclic trypomastigotes were separated from residual epimastigotes by anion-exchange chromatography (20). Briefly, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2 (PBS), at 4°C and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 140 mM NaCl at a density of 107/ml. In typical separations, 109 cells were mixed with 100 ml of DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B, the mixture was poured into a column, and the metacyclic trypomastigotes were eluted with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 140 mM NaCl. Purity was checked by Giemsa staining and by complement-induced lysis of epimastigotes. Purified metacyclic trypomastigotes were stored at −70°C until used.

Isolation of genomic DNA and mRNA.

Epimastigotes (3 × 109 cells) were lysed in 50 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 100 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), RNase (20 μg/ml), and proteinase K (100 μg/ml) for 3 h at 50°C. After phenol extraction, the DNA was precipitated with 0.2 volumes of 10 M ammonium acetate and 2 volumes of ethanol. Total RNA was isolated by using a FASTTRACK kit (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Amplification of sequences encoding PP1 and PP2A homology domains.

Three oligonucleotide primers corresponding to conserved domains in protein phosphatases were synthesized: primer 1, CGDIHGQ (forward), 5′-AGCTGCAGA ATTCTG(C/T)GG(C/T/G)GA(C/T)AT(T/C)CACGG(C/T/G)CA; primer 2, LRGNHE (reverse), 5′-AGGTCGACAAGCTT(C/T)TCGTG(G/A)TT(G/A/C)CC(A/G)CG(C/G/A)AG; and primer 3, NYCGEFD (reverse), 5′-AGGTCGACAAGCTTGTCGAACTCGTCGCAGTAGTT. Primers 1 and 2 correspond to conserved domains in PP1, PP2A, and PP2B. Primer 3 is specific for PP1. To facilitate cloning of the PCR products, the primers were designed with restriction sites at their 5′ ends (forward primer, EcoRI and PstI; reverse primers, SalI and HindIII). The PCR mixture (100 μl) contained 1 μg of sheared T. cruzi genomic DNA, 200 ng of each primer, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. PCR conditions were 1 min each at 94 and 50°C followed by 1.5 min at 72°C for 35 cycles. The last cycle was 10 min at 72°C. Bands of the appropriate size, i.e., 220 bp for primers 1 and 2 and 648 bp for primers 1 and 3, were isolated, subcloned into pBluescript IISK(+) (Stratagene), and sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide termination procedure of Sanger et al. (24), using a combination of pBluescript and synthetic oligonucleotide primers.

Genomic library construction and screening.

T. cruzi genomic DNA was partially digested with SauI and electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel. The region of the gel between 2 and 9 kb was excised and electroeluted, and the resultant DNA was ligated and packaged into the ZAP Express vector (Stratagene) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The library was screened with a 32P-labeled probe prepared by PCR using primers 1 and 3. Positive clones were plaque purified and sequenced as described above.

Northern and Southern blot analyses.

Total RNA (20 μg), isolated from T. cruzi epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigotes, was electrophoresed on 1% agarose–formaldehyde gels and capillary blotted to nylon membranes by standard procedures. The membranes were probed with the 648-bp insert labeled with 32P by PCR amplification with primers 1 and 3. Hybridization was performed at 42°C overnight; then the membranes were washed once with 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.5% SDS for 20 min at room temperature and then three times with 0.2× SSC–0.5% SDS for 20 min each time at 65°C.

For Southern analysis, DNA (40 μg) was digested with various restriction enzymes (50 U each) at 37°C overnight. The restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 0.7% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes. Probe labeling, hybridization, and washing conditions were as for Northern blot analysis.

Protein phosphatase assay.

PP1 and PP2A activities in T. cruzi epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote extracts were determined by using a 32P-labeled phosphorylase assay system (GIBCO BRL) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. One unit of phosphatase activity releases 1 nmol of [32P]phosphate from 32P-labeled phosphorylase a per minute. The concentrations of calyculin A and okadaic acid in the assay mixture ranged from 0 to 1 μM. Cell extracts were prepared as previously described (22). In the case of recombinant Escherichia coli lysates, samples were serially diluted twofold in 50 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, containing 2 mM MnCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 1% Triton X-100 prior to assay.

Bacterial expression of T. cruzi protein phosphatases.

PCR primers incorporating the initiator ATG into the NdeI recognition sequence or placing a BamHI site immediately downstream of the stop codon of both phosphatase genes were synthesized; the primer sequences for TcPP1α were 5′-CGCGCATATGACATCAAACGTAGTGCATAACCTC and 3′-CCGGATCCTTAATACTTTTTATCTACAAGGCCTGTG, while those for TcPP1β were 5′-CGCGCATATGTCCCCCGTGGTTACCC and 3′-CCGGATCCTTAGTACTGCGGCTTGAAGAC. PCRs were performed with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The respective PCR products were cloned into pET5a (Promega) as NdeI-BamHI fragments. In the case of TcPP1β, uncut PCR product was also subcloned into EcoRV-cut, phosphatase-treated pBluescript II KS(+) and screened by PCR. The PCR-positive clone was redigested with NdeI and HindIII (there is a site for the latter in the polylinker), and the fragment was ligated into NdeI- and HindIII-digested pTACTAC (a kind gift of E. Y. C. Lee). Sequencing revealed a 5-nucleotide nt deletion which obliterated the BamHI site but no changes within the coding sequence. In the case of TcPP1α, the pET5a NdeI-BamHI insert was isolated and recloned into an NdeI-containing derivative of pBluescript II KS(+) that was constructed for this purpose and designated pBSNNXKS+ and, from there, as an NdeI-HindIII insert into pTACTAC. A second PCR product of TcPP1α, based on the revised 3′ sequence (GCAGGATCCTAACTGTTTGCCGGAACAATGAGG) and lacking the T. cruzi 3′ untranslated region, was cloned directly into NdeI- and BamHI-cut pBSNNXKS+ before transfer to pTACTAC.

The pTACTAC constructs were transformed into E. coli DH5α, and after induction with 1-thio-β-galactopyranoside (0.2 mM) at 37°C for 8 h, the bacterial pellet was resuspended (1 ml/g [wet weight]) in 50 mM triethanolamine-HCl, pH 7.8, containing 200 mM sucrose, lysozyme (1 mg/ml), and Minicomplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (1 tablet/10 ml; Boehringer Mannheim). After a 20-min incubation of the suspension at 4°C, an equal volume of H2O was added, followed by Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 1%. The bacterial lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant stored at −70°C until use.

Light microscopy.

For light microscopic examination, organisms were removed from the medium by centrifugation at 800 × g, washed twice in PBS, resuspended in PBS, and placed on slides. After air drying, the slides were fixed in absolute methanol for 5 min and stained first with May-Gruenwald stain (Harelco) for 5 min and then with Giemsa stain for 13 min. Slides were rinsed first in acetone, then in acetone-xylene (1:1), and finally in xylene. They were mounted in Permount and photographed, using a Nikon Axiomat photomicroscope.

Fluorescence microscopy.

For 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, organisms were washed once and then resuspended in PBS and a drop of suspension was placed on a glass slide and allowed to settle. After fixation in 70% ethanol, the slides were stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 15 min and mounted in PBS–50% glycerol. The slides were examined with a Nikon Axiophot UV microscope employing a generic blue filter (XF13; emission wavelength, 450 nm; Omega Optical Inc., Brattleboro, Vt.)

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Trypanosome suspensions were fixed in 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.2, for 30 min at room temperature (20°C). The fixed trypanosomes were centrifuged (1,000 × g) for 30 s, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was resuspended in warm (45°C) 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.2, containing 2% (wt/vol) agar and allowed to cool to room temperature. All subsequent procedures utilized cold (4°C) solutions through 95% ethanol; 100% ethanol and propylene oxide were used at room temperature. The solidified agar, containing the suspended trypanosomes, was cut into small (1- by 2-mm) cubes and fixed for 24 h in PBS–2.5% glutaraldehyde. The agar cubes were rinsed several times in PBS and then postfixed in PBS–1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide for 4 h. The cubes were subsequently rinsed in PBS, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, treated with propylene oxide (transitional fluid), and embedded in Araldite 502. Thin sections (silver) were placed on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a Philips CM-IO transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV.

SEM.

Trypanosome suspensions were spread on acid-washed 18-mm-diameter circular cover glasses and allowed to partially air dry. The cover glasses were placed in 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2) for 12 h at 4°C, rinsed several times in PBS, postfixed in PBS–1% (vol/vol) osmium tetroxide for 2 h, rinsed several times in PBS, and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series. The cover glasses were then placed in acetone and critical-point dried in a Tousimis Samdri-790 critical-point drier (Tousimis Research Corp., Rockville, Md.), using liquid carbon dioxide for the transition. Cover glasses were mounted on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) aluminum stubs with silver paint and sputter coated in a Denton Du-502 vacuum evaporator (Denton Vacuum, Inc., Cherry Hill, N.J.) equipped with a gold target. The critical-point-dried and sputter-coated trypanosomes were then examined with a Super IIIA or an SS-40 scanning electron microscope (ISI International Scientific Instruments, Santa Clara, Calif.) operated at 15 kV.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequences reported in this paper are available in the GenBank database under the accession no. AF190456 and AF190457

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of genes encoding serine/threonine protein phosphatases in T. cruzi.

We have used PCR to isolate T. cruzi genomic fragments corresponding to conserved domains in the catalytic subunits of PP1, PP2A, and PP2B. The lack of introns in the T. cruzi genome made PCR an ideal tool for this type of analysis. Initially, two degenerate primers were designed against conserved sequences common to all three isotypes (4). The sequences chosen were CGDIHGQ (sense primer) and LRGNHE (antisense primer). Amplification of T. cruzi genomic DNA with these primers gave rise to a 220-bp fragment, the expected size based on the sequences of the mammalian enzymes. After subcloning of the PCR fragment into pBluescript, examination of over 30 individual clones revealed the presence of two distinct nucleotide sequences. Both sequences contained an open reading frame which, in addition to the conserved primers, possessed residues diagnostic for PP1, PP2A, and PP2B. For example, the sequence GDXVDRG is found in all three isotypes throughout different phyla. Overall comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences indicated that both amplified sequences were more homologous to mammalian PP1 than to PP2A or PP2B. To confirm that both sequences encoded a PP1-type enzyme, an additional degenerate primer corresponding to a C-terminal domain (NYCGEFD) which is highly conserved in all characterized PP1 enzymes was designed (4). This sequence is not conserved in either PP2A or PP2B. Amplification with primers 1 and 3 gave rise to a 648-bp fragment. When this fragment was amplified with primers 1 and 2, a 220-bp fragment was obtained (data not shown). After subcloning of the 648-bp fragment into pBluescript, analysis of the purified clones again revealed the presence of two unique nucleotide sequences. Each sequence contained an open reading frame, and each open reading frame contained one of the previously characterized N-terminal sequences obtained with the previous primer pair.

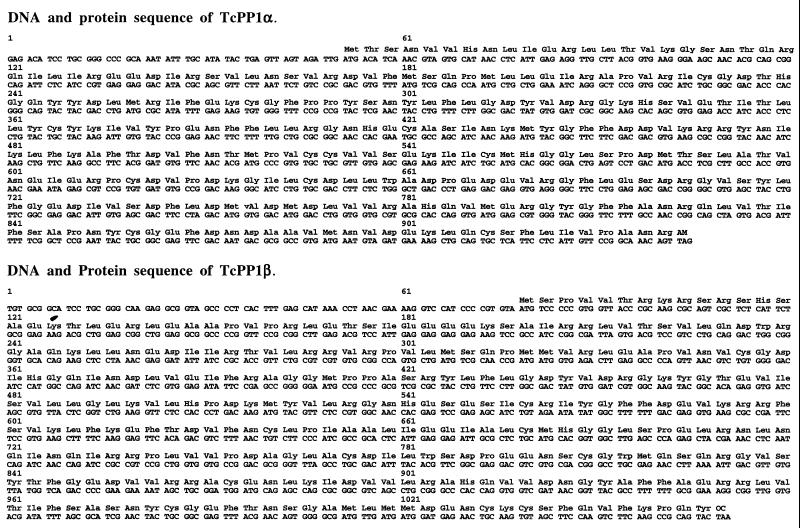

The remaining 5′ and 3′ sequences of both phosphatase genes were obtained by screening a T. cruzi genomic library in λZap Express with the 32P-labeled 648-bp PCR-generated fragment of each gene. The complete nucleotide sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence of the two genes are shown in Fig. 1. Computer searches of the databases revealed significant homology to the mammalian PP1 isotype. The two T. cruzi genes encode proteins of 323 and 330 amino acids that have been tentatively designated TcPP1α and TcPP1β, respectively. TcPP1α exhibits 61% identity to the conserved catalytic core of mammalian PP1. If conservative amino acid substitutions are included, this number increases to 77%. In contrast, TcPP1β is 54% identical and 72% similar to the mammalian PP1. The levels of identity of both TcPP1α and TcPP1β to the corresponding regions of either mammalian PP2A or PP2B are considerably lower. TcPP1α is 43 and 34% identical to mammalian PP2A and PP2B, respectively. The corresponding levels of identity for TcPP1β are 42 and 38%.

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of TcPP1α and TcPP1β.

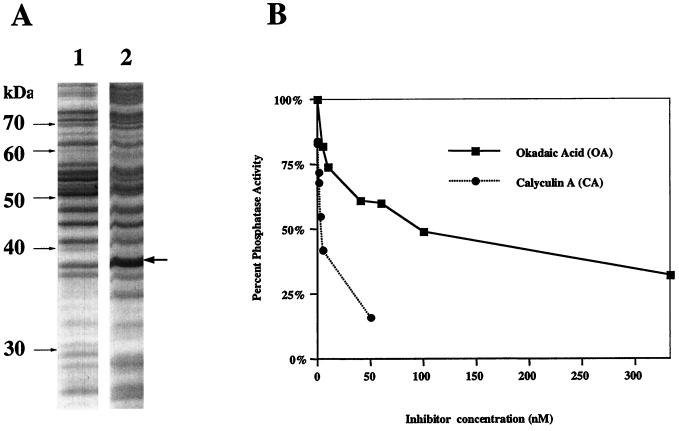

Expression of TcPP1α and TcPP1β in E. coli.

Since the glutathione S-transferase and β-galactosidase fusion proteins of the putative PP1 and PP2A from Trypanosoma brucei failed to show phosphatase activity (10), we decided to include only the native coding sequences of the T. cruzi phosphatases in these bacterial expression studies. Taking advantage of the fact that the initiator methionine codon ATG forms the 3′ half of the NdeI recognition site, we have inserted the coding sequence of both genes in frame into the NdeI site of pTACTAC, a lac-inducible expression vector. This vector was used successfully to express the rabbit muscle PP1 catalytic subunit as a soluble and active protein in E. coli (29). After induction and cell fractionation, we observed that TcPP1β expressed in E. coli DH5α possessed phosphatase activity against 32P-labeled phosphorylase a. In contrast, E. coli transformed with the vector alone possessed no such phosphatase activity (data not shown). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis PAGE analysis revealed the presence of an ∼37-kDa polypeptide in lysates from E. coli transformed with TcPP1β-pTACTAC that was absent in bacteria transformed with the empty vector (Fig. 2A). The predicted molecular weight of TcPP1β is 37,557. Lysates were assayed for protein phosphatase activity, using 32P-labeled phosphorylase as a substrate. Protein phosphatase activity was detected in E. coli expressing TcPP1β (0.5 to 1 U/ml of supernatant) but not in E. coli transformed with vector alone. The recombinant TcPP1β phosphatase activity was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by calyculin A, with an estimated IC50 of ∼2 nM (Fig. 2B). The IC50 for inhibition of phosphatase activity by okadaic acid was ∼100 nM. Attempts to achieve high-level expression of phosphatase activity directed against 32P-labeled glycogen phosphorylase by using TcPP1α in pTACTAC were unsuccessful.

FIG. 2.

Bacterial expression of TcPP1β and inhibition by calyculin A and okadaic acid. (A) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of extracts from E. coli transformed with pTACTAC alone (lane 1) or with TcPP1β-pTACTAC (lane 2). (B) Recombinant TcPP1β assayed using 32P-labeled phosphorylase as substrate in the absence or presence of various concentrations of either calyculin A or okadaic acid. The extract was diluted 1:128 prior to use. No phosphatase activity was detected in lysates of E. coli transformed with empty vector alone.

Northern and Southern blot analyses of TcPP1α and TcPP1β.

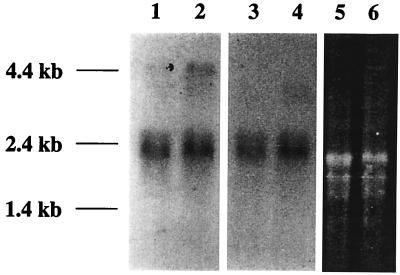

Northern blot analysis using RNA isolated from both epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigotes of T. cruzi was performed to determine whether the mRNAs encoding TcPP1α and TcPP1β were differentially expressed in the two vector-specific developmental stages. In these experiments, hybridization was performed with each 32P-labeled 648-bp PCR-generated fragment under high-stringency conditions. Both probes hybridized with a major 2.3-kb mRNA transcript present in approximately equal levels in both developmental stages (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Northern analysis of TcPP1α and TcPP1β mRNA expression in T. cruzi epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigotes. RNA from epimastigotes or metacyclic trypomastigotes was separated on a 1% agarose–formaldehyde gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with the appropriate probe as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 and 3, epimastigote RNA probed with TcPP1α; lanes 2 and 4, metacyclic trypomastigote RNA probed with TcPP1β; lanes 5 and 6, ethidium bromide-stained gels of epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote RNA, respectively, showing the characteristic triplet pattern of T. cruzi rRNA and demonstrating equal loading and integrity of the samples.

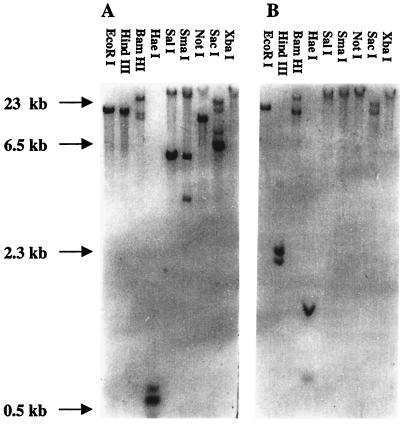

Southern blot analysis was performed with T. cruzi genomic DNA digested with a variety of restriction endonucleases. Hybridization was performed with the 32P-labeled 648-bp TcPP1α and TcPP1β probes under high-stringency conditions to prevent cross-hybridization. Although some cross-hybridization was apparent with some high-mass fragments, both probes clearly hybridized with unique restriction fragments, and the predicted HindIII doublet due to an internal HindIII cleavage was seen in TcPP1β. The hybridization patterns shown in Fig. 4 are consistent with the presence of a single genomic copy for each phosphatase.

FIG. 4.

Genomic Southern analysis of TcPP1α and TcPP1β. Genomic DNA was digested with different restriction enzymes, electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with the appropriate probe as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers on the left indicate the sizes of HindIII-digested products of λ DNA. (A) TcPP1α; (B) TcPP1β.

Effect of calyculin A and okadaic acid on the growth and morphology of T. cruzi epimastigotes.

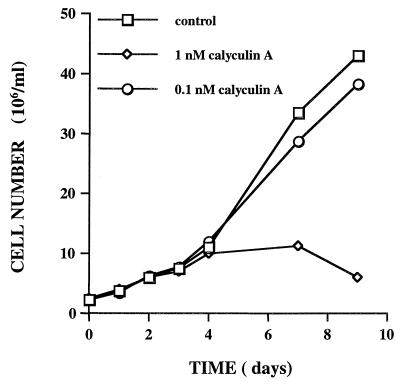

T. cruzi (strain HO 3/15) epimastigotes were grown in the presence of various concentrations of the serine/threonine protein phosphatase inhibitors calyculin A and okadaic acid, and the cell numbers were determined at time intervals over the next several days. Low concentrations of calyculin A were found to have a profound effect on the growth of epimastigotes. At 5 and 10 nM calyculin A there was an immediate and complete arrest of cell growth (data not shown). The organisms, however, remained motile. At 1 nM calyculin A, epimastigotes divided once, and possibly twice, before undergoing growth arrest (Fig. 5). In contrast, okadaic acid at concentrations up to 1 μM had no effect on the growth of epimastigotes (data not shown). This pattern of inhibitor sensitivity suggests that PP1-type enzymes are important for epimastigote growth.

FIG. 5.

Effect of calyculin A on growth of T. cruzi epimastigotes. Epimastigotes were cultured at a density of 2.5 × 106/ml (total volume, 10 ml) in the presence or absence of calyculin A or okadaic acid as described in Materials and Methods. Cell number was determined at various times after the additions.

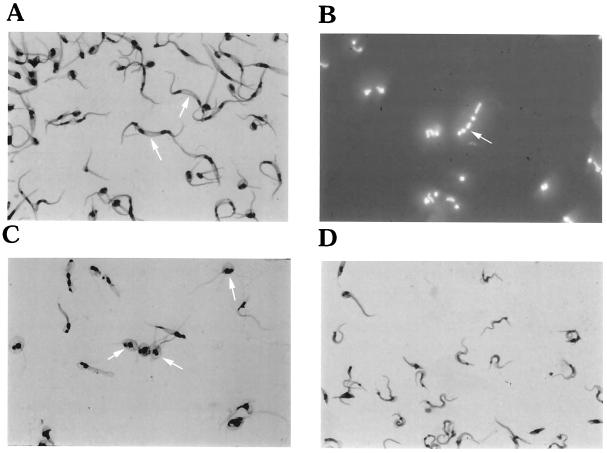

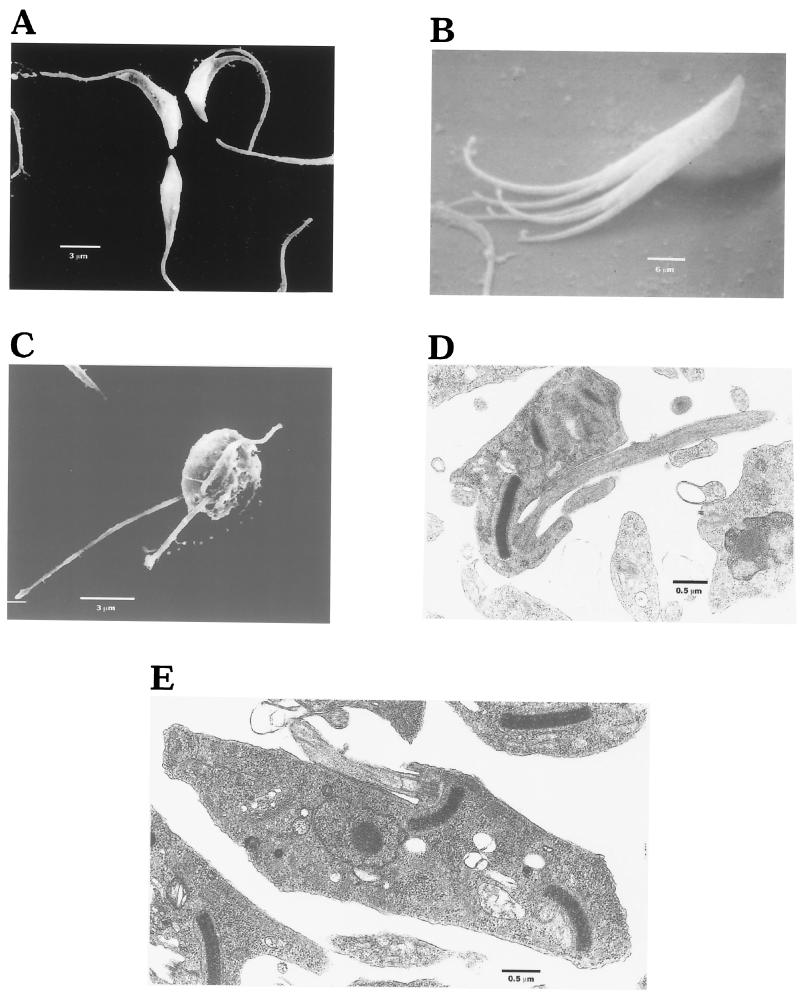

The inhibition of T. cruzi replication by calyculin A was accompanied by the formation of abnormal morphologic forms consistent with arrested cytokinesis. Light microscopy, utilizing both Geimsa and DAPI staining, revealed the failure of organisms treated with 5 nM calyculin to initiate or successfully complete cytokinesis (Fig. 6A). Multiple nuclei, flagella, and kinetoplasts were observed in treated cells (Fig. 6A and B). At this concentration, loss of cell shape, i.e., spheromastigote-like or rounded forms, became evident early (1 day), but by 7 days this also was evident at concentrations as low as 1 nM (Fig. 6C). The parasites were also examined by SEM after 3 days of exposure to calyculin A (10 nM). Figure 7A is a scanning electron micrograph of untreated normal dividing epimastigotes, each with a single flagellum. Figure 7B is an SEM view of an extreme example of a calyculin A-treated epimastigote that has initiated but failed to complete cytokinesis two or three times. Figure 7C is an SEM view of a spheromastigote-like form of a calyculin A-treated epimastigote that possesses two, or possibly three, flagella. When examined by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 7D and E) after 3 days of exposure to calyculin (5 nM), T. cruzi was again seen to contain multiple copies of normal-appearing organelles, compared with untreated T. cruzi.

FIG. 6.

Light microscopy of calyculin A-treated T. cruzi epimastigotes. (A) Giemsa-stained epimastigotes treated with calyculin A (5 nM) for 3 days. Organisms with multiple nuclei and kinetoplasts are evident (arrows). Rounded or spheromastigote-like organisms with multiple flagella are also evident. The organisms are enlarged because cytokinesis has been arrested. (B) DAPI-stained organisms, as in panel A, showing multiple organelles (arrow). (C) Giemsa-stained epimastigotes treated for 7 days with 1 nM calyculin A. Predominantly spheromastigote-like or rounded forms with multiple flagella, nuclei, and kinetoplasts are evident (arrows). (D) Untreated (control) epimastigotes. In all panels, the final magnification is 720×.

FIG. 7.

Electron microscopy of Calyculin A-treated T. cruzi epimastigotes. (A) SEM of a normal untreated epimastigote. (B) SEM view of an extreme example of arrested cytokinesis in a calyculin-treated epimastigote that has initiated but failed to complete cytokinesis two or three times. (C) SEM view of a treated spheromastigote-like organism with three flagella. (D) TEM photograph of a treated epimastigote, showing three kinetoplasts; the large kinetoplast appears to be preparing to undergo replication. (E) TEM photograph of a treated epimastigote; two kinetoplasts and a single nucleus are evident.

Effect of calyculin A and okadaic acid on protein phosphatase activity in T. cruzi epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigotes.

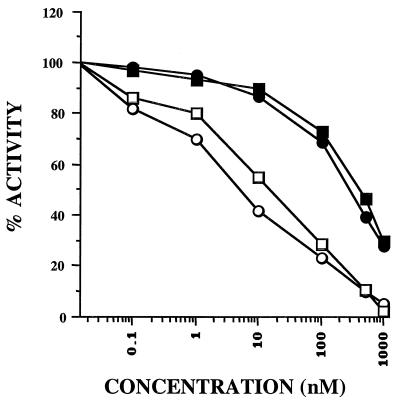

To assess directly the effect of each inhibitor on phosphatase activity, the abilities of extracts isolated from both vector developmental stages to dephosphorylate 32P-labeled phosphorylase a in the presence of each inhibitor were measured. In higher eukaryotes, both PP1 and PP2A, but not PP2B or PP2C, can catalyze this reaction. Calyculin A, but not okadaic acid, was a potent inhibitor of the phosphorylase phosphatase activity present in both developmental stages (Fig. 8). The IC50 for calyculin was estimated to be 10 nM. In contrast, the IC50 for okadaic acid was greater than 500 nM. These data strongly suggested that PP1-type enzymes are the major phosphatases catalyzing the dephosphorylation of phosphorylase a in T. cruzi epimastigote and metacyclic trypomastigote extracts.

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of phosphatase activity present in T. cruzi epimastigotes and metacyclic trypomastigotes by calyculin A and okadaic acid. Cellular extracts of both developmental forms were assayed, using 32P-labeled phosphorylase as a substrate, in the absence or presence of either calyculin A or okadaic acid at various concentrations. Epimastigotes, circles; metacyclic trypomastigotes, squares; calyculin A, open symbols; okadaic acid, closed symbols.

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of serine/threonine residues constitute major regulatory pathways in higher eukaryotes, controlling a wide range of intracellular processes (5, 17). It has become increasingly apparent that protein phosphatases, in addition to kinases, play a dynamic role in regulating these cellular events (3, 6). Mammalian serine/threonine protein phosphatases are classified into four major types, 1, 2A, 2B, and 2C, depending on substrate and inhibitor specificities and on metal ion dependencies (3, 6). It has been established that PP1, PP2A, and PP2B are members of the PPP gene family which share a conserved catalytic core of approximately 280 amino acids (4). PP2C bears no sequence homology to the other three phosphatase types and has been classified as a PPM phosphatase. We have performed PCR with degenerate oligonucleotide primers against conserved domains in PP1-, PP2A-, and PP2B-type enzymes to catalog and characterize the genes encoding related phosphatases in T. cruzi. The initial sequences used for primer design were C62GDIHGQ (sense) and L121RGNHE (antisense). The numbering is based on mammalian PP1α. This primer pair was designed to amplify all members of the PP1/PP2A/PP2B family of protein phosphatases. An additional set of primers, designed to amplify specifically the PP1-type enzyme, used the sense primer mentioned above plus an additional antisense primer based on the sequence N271YCGEFD. This sequence is highly conserved in all characterized PP1s from mammals to higher plants (4). Analysis of the amplified products with either primer set revealed the presence of two unique nucleotide sequences. The sequences obtained using the PP1/PP2A/PP2B “universal” primer pair were also contained in one of the two sequences obtained by using the PP1-specific primer pair. The complete nucleotide sequences for both phosphatase genes were obtained by screening a T. cruzi genomic library. One gene, containing an open reading frame that has a higher level of homology to that of human PP1 than to that of human PP2A or PP2B, encodes a protein designated TcPP1α. The other gene product also was more related to human PP1 than to human PP2A or PP2B. In a comparison of 21 PP1-like enzymes from separate phyla, it was found that the level of sequence identity ranged from 54 to 100%. The product of this T. cruzi phosphatase gene falls within the lower range of sequence identity for PP1-like enzymes and was designated TcPP1β. Barton et al. (4) identified 42 invariant residues in 44 eukaryotic PP1-PP2-PP2B by multiple sequence alignment. In TcPP1α, one of these invariant residues is not conserved (E139 to a D), whereas in TcPP1β there are three changes: S100 to G, F235 to A, and P270 to S. However, that fact that all of these residues are either not conserved or absent in the λ bacteriophage phosphatase ORF221 suggests that they are not essential for phosphatase activity. Importantly, the residues in mammalian PP1 (N271YCGEFD) responsible for the interaction with a variety of toxins, including calyculin A, are totally conserved in both T. cruzi sequences (30).

Both putative phosphatase genes were expressed as recombinant proteins in E. coli by using pTACTAC, a vector with a trp-lac hybrid promoter that was used successfully to express the human PP1 isoforms (29). Recombinant TcPP1β was shown to catalyze the dephosphorylation of 32P-labeled phosphorylase a and exhibited inhibitor sensitivities similar to those of its mammalian counterpart; i.e., it was preferentially inhibited by calyculin A over okadaic acid. Efforts to obtain high-level phosphatase activity against 32P-labeled phosphorylase a by using the TcPP1α-pTACTAC construct were unsuccessful. It is unclear whether the lack of phosphatase activity is due to poor protein expression or inappropriate folding or whether TcPP1α has a restricted substrate specificity. In contrast to TcPP1β, upon SDS-PAGE, there was no distinct band of the appropriate size in E. coli containing this expression vector.

No other phosphoserine/threonine phosphatase genes were amplified from T. cruzi genomic DNA with the universal PP1/PP2A/PP2B primer pair under the conditions employed. Since trypanosomids diverged early in the eukaryotic lineage, it is possible that the sequences chosen for the amplification primers, although extremely highly conserved across different phyla, have been modified to such an extent in other T. cruzi PPP-type phosphatases that amplification will not occur. An alternative explanation is that PP2A/PP2B-type phosphatases do not exist in this lower-eukaryotic protozoan. However, PP2A-type phosphatases have been identified in the African trypanosome T. brucei (10) and in Plasmodium falciparum (18).

We used calyculin A and okadaic acid to explore the role of the PP1- and PP2A-type phosphatases in T. cruzi. The differences in inhibitor specificity have allowed investigation of the role of PP1 and PP2A in intact cells (11, 15, 16, 28). Calyculin A, but not okadaic acid, had profound effects on the growth and morphology of T. cruzi epimastigotes. In the presence of 1 to 10 nM calyculin A, there was cessation of cell replication accompanied by the formation of morphologically abnormal organisms. Microscopic studies revealed that duplication of major organelles, including the flagellum, kinetoplast, and nucleus, occurred in the presence of calyculin A; cytokinesis, however, was arrested. The loss of the typical trypanosomal morphology suggested that major alterations to the subpellicular microtubular network had occurred. In mammalian fibroblast and epithelial cell lines, both calyculin A and okadaic acid caused the selective breakdown of stable, but not dynamic, microtubules, suggesting that PP1 and PP2A are involved in the regulation of microtubule stability (15). It was recently reported that calyculin A promoted the extracellular transformation of T. cruzi trypomastigotes to amastigote-like forms (14). Calyculin A caused trypomastigotes to lose their characteristic spindle shape and adopt a spherical shape typical of amastigotes. In addition to these morphological alterations, calyculin A also induced the expression of amastigote-specific epitopes and caused a repositioning of the kinetoplast.

In the African trypanosome T. brucei, okadaic acid was used to uncouple nuclear and organelle (i.e., kinetoplast) segregation (8). In these organisms, nuclear DNA duplicated and segregated while kinetoplast DNA duplicated but did not segregate to form new organelles. Moreover, flagellar duplication was incomplete and the organisms retained their elongated morphology. In contrast, in calyculin A-treated T. cruzi, both kinetoplast and nuclear DNA duplicated and segregated, forming new organelles, and there was also complete flagellar duplication. Although the African and American trypanosomes are classified in the same genus, vast genetic distances (12% divergence) separate T. brucei and T. cruzi and may account for the differences observed (27).

The fact that cessation of epimastigote replication and the occurrence of morphological changes were observed with calyculin A but not with okadaic acid suggests that inhibition of a PP1-type enzyme(s) was responsible for both phenotypes. We have also shown that the major phosphatase activity in T. cruzi extracts capable of dephosphorylating 32P-labeled phosphorylase a is inhibited by low concentrations of calyculin A but not by okadaic acid. These in vivo and in vitro inhibitor studies suggest that calyculin A-sensitive PP1-type enzymes are the major cellular phosphatases in T. cruzi. It is likely that the two phosphatase genes characterized in this study are responsible for the calyculin A phenotypes observed in this study and by others (14). Moreover, the recombinant protein encoded by the TcPP1β gene exhibited calyculin A-sensitive phosphatase activity. Since both PP1-like phosphatases appear to be encoded by single-copy genes, we are in a position to create strains of T. cruzi lacking either or both phosphatases by homologous recombination. In addition, transfection studies will allow us to overexpress each phosphatase specifically. Such experiments will allow us to explore the physiological role of each phosphatase in the growth and development of the parasite.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI 12770, AI 41752, HD 27569, and P30-CA13330. C.W. was supported by National Institutes of Health Molecular Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases training grant AI07506.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarenga N J, Brener Z. Isolation of pure metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi from triatome bugs by use of a DEAE-cellulose column. J Parasitol. 1979;65:814–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews N W, Hong K S, Robbins E S, Nussenweig V. Stage-specific surface antigens expressed during the morphogenesis of the vertebrate forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp Parasitol. 1998;64:474–484. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(87)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barford D. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:407–412. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton G F, Cohen P T W, Barford D. Conservation analysis and structure prediction of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:225–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen P. Signal integration at the level of protein kinases, protein phosphatases and their substrates. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen P, Cohen P T W. Protein phosphatases come of age. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21435–21438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contreras V T, Morel C M, Goldenberg S. Stage specific expression precedes morphological changes during Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1985;14:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(85)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das A, Gale M, Carter V, Parsons M. The protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid induces defects in cytokinesis and organellar segregation in Trypanosoma brucei. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:3477–3483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Castro S L, de N. L. Meirelles M, Oliveira M M. Trypanosoma cruzi: adrenergic modulation of cyclic AMP in proliferation and differentiation of amastigotes in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 1987;64:368–375. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(87)90049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erondu N E, Donelson J E. Characterization of trypanosome protein phosphatase 1 and 2A catalytic subunits. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90074-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Favre B, Turowski P, Hemmings B A. Differential inhibition and posttranslational modification of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A in MCF7 cells treated with calyculin A, okadaic acid, and tautomycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13856–13863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez M L, Erijman L, Torres H N, Tellez-Inon M T. Protein kinase C in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote forms: partial purification and characterization. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;36:101–108. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzales-Perdomo M, Romero P, Goldenberg S. Cyclic AMP and adenylate cyclase activators stimulate Trypanosoma cruzi differentiation. Exp Parasitol. 1988;66:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grellier P, Blum J, Santana J, Bylèn E, Mournay E, Sinou V, Teixeira A R L, Schrével J. Involvement of calyculin A-sensitive phosphatase in the differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes to amastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;98:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurland G, Gundersen G G. Protein phosphatase inhibitors induce the selective breakdown of stable microtubules in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8827–8831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardie D G, Haystead T A J, Sim A T. Use of okadaic acid to inhibit protein phosphatases in intact cells. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:469–476. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J-I, Baker D A. Protein phosphatase β, a putative type-2A protein phosphatase from the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozaki T, Dvorak J A. Trypanosoma cruzi: flow cytometric analysis of developmental stage differences in DNA. J Protozool. 1991;38:234–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1991.tb04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochatt C M, Ulloa R M, Torres H N, Tellez-Inon M T. Characterization of the catalytic subunit of Trypanosoma cruzi cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;57:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90245-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogueta S, Intosh G M, Tellez-Inon M T. Regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;78:171–183. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orr G A, Tanowitz H B, Wittner M. Trypanosoma cruzi: stage expression of calmodulin-binding proteins. Exp Parasitol. 1992;74:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90039-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oz H, Wittner M, Tanowitz H B, Bilezikian J P, Saxon M, Morris S A. Trypanosoma cruzi: mechanisms of intracellular calcium homeostasis. Exp Parasitol. 1992;74:390–399. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90201-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanowitz H B, Kirchhoff L V, Simon D, Morris S A, Weiss L M, Wittner M. Chagas' disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:409–419. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulloa R M, Mesri E, Esteva M, Torres H N, Tellez-Inon M T. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase activity in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem J. 1988;255:319–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vickerman K. The evolutionary expansion of the trypanosomatid flagellates. Int J Parasitol. 1994;24:1317–1331. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yano Y, Sakon M, Kambayashi J, Kawasaki T, Senda T, Tanaka K, Yamada F, Shibata N. Cytoskeletal reorganization of human platelets induced by the protein phosphatase 1/2 A inhibitors okadaic acid and calyculin. Biochem J. 1995;307:439–449. doi: 10.1042/bj3070439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang A J, Bai G, Deans-Zirattu S, Browner M F, Lee E Y. Expression of the catalytic subunit of phosphorylase phosphatase (protein phosphatase-1) in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1484–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Zhang Z, Long F, Lee E Y C. Tyrosine-272 is involved in the inhibition of protein phosphatase-1 by multiple toxins. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1606–1614. doi: 10.1021/bi9521396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]