Abstract

In the last two years since the inception of the Coronavirus pandemic, there have been a myriad of reports and studies related to Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). We present a unique case of COVID-19 associated with both acute myocardial infarction and new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFIB) in an elderly lady which is the first reported case to the best of our knowledge. The patient was symptomatic with acute COVID-19 and developed a type 2 myocardial infarction with new-onset AFIB. The patient also developed sepsis which may have contributed to the development of AFIB.

Keywords: acute hypoxic respiratory failure, nstemi, new onset afib, coronavirus 19, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation

Introduction

COVID-19 is known to primarily affect the pulmonary system, however cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 including acute myocardial infarction and arrhythmias are well described [1]. According to one article, the incidence of new onset AFIB in patients with COVID-19 is 3.6-6.7% [2]; according to another study that used the results from the American Heart Association’s COVID-19 Cardiovascular registry, the incidence was 5.4% [3]. A meta-analysis found the prevalence of acute myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19 infection to be 20% [4]. Here, we present a case of new-onset AFIB and acute myocardial infarction in a 72-year-old female patient who presented with altered mental status secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia; this is the only case report to our knowledge documenting this.

Case presentation

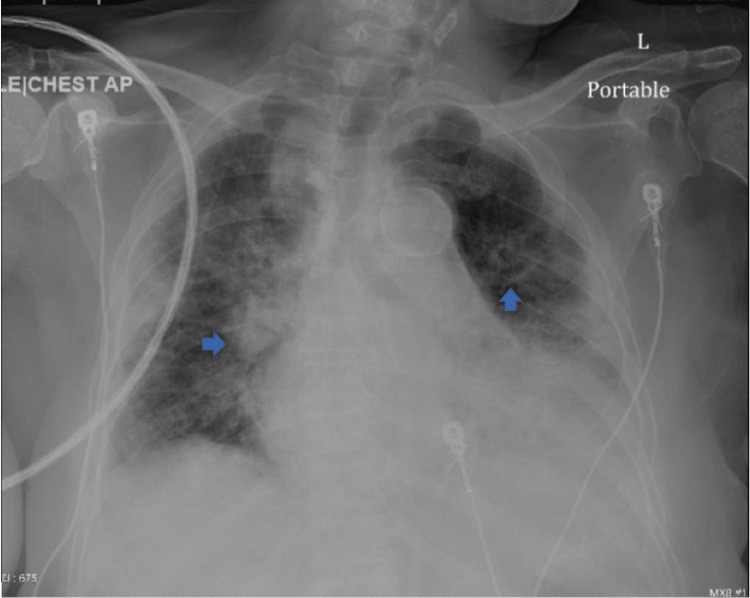

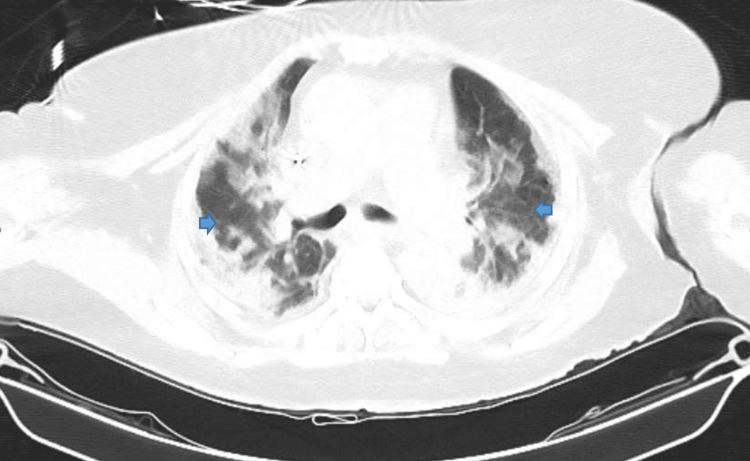

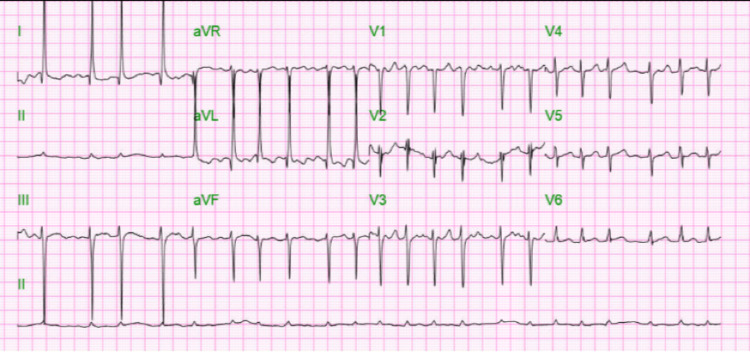

Our patient is a 72-year-old female with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease stage 3b, who was brought in by ambulance to the emergency department with altered mental status. According to the family, the patient was independent in activities of daily living prior to this admission. A physical exam on admission showed disorientation, dehydration, wheezing, and tachycardia. Remarkable labs on admission can be found in the table below (Table 1). The patient was found to be COVID-19 positive with bilateral pneumonia and ground glass opacities seen on chest X-ray (Figure 1) and chest CT (computerized tomography) scan (Figure 2). The patient was also in septic shock with tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis, and elevated lactate. CT scan of the head was negative for any acute disease. Urine toxicology was also negative. Her electrocardiogram (EKG) on admission showed new-onset atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response (Figure 3); she had no known previous history of atrial fibrillation. On admission, high-sensitivity troponins were elevated to greater than 20,000 nanograms per liter but no ST deviations or T-wave abnormalities suggesting acute ischemia were seen on EKG.

Table 1. Patient’s Laboratory Findings on Admission.

| Laboratory Test | Normal Range | Results |

| White Blood Cells | 4,500 - 11,000 cells per microliter | 13,500 cells per microliter |

| Hemoglobin | 11.0 - 15.0 grams per deciliter | 17.4 grams per deciliter |

| Hematocrit | 35 - 46 percent | 52.4 percent |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume | 80 - 100 femtoliters | 85.8 femtoliters |

| Platelets | 130,000 - 400,000 platelets per microliter | 111,000 platelets per microliter |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen | 9.8 - 20.1 milligrams per deciliter | 104.1 milligrams per deciliter |

| Creatinine | 0.57 - 1.11 milligrams per deciliter | 3.19 milligrams per deciliter |

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate | >=90.0 millimeters per minute per 1.73 square meters | 14.2 millimeters per minute per 1.73 square meters |

| Potassium | 3.5 - 5.1 millimoles per liter | 4.2 millimoles per liter |

| Phosphorus | 2.3 - 4.7 milligrams per deciliter | 4.0 milligrams per deciliter |

| Magnesium | 1.6 - 2.6 milligrams per deciliter | 3.3 milligrams per deciliter |

| D-dimer | <=500 nanograms per milliliter d-dimer units | > 7,650 nanograms per milliliter d-dimer units |

| Prothrombin time | 9.8 - 13.4 seconds | 15.5 seconds |

| International Normalized Ratio | 0.85 - 1.15 ratio | 1.27 ratio |

| Partial Thromboplastin Time | 24.9 - 35.9 seconds | 29.9 seconds |

| Thyroid Stimulating Hormone | 0.465 - 4.680 micro-international units per milliliter | 0.926 micro-international units per milliliter |

| Thyroxine | 0.78 - 2.19 nanograms per deciliter | 1.19 nanograms per deciliter |

| Brain Natriuretic Peptide | 10.0 - 100.0 picograms per milliliter | 365.2 picograms per milliliter |

Figure 1. Chest X-ray on Admission.

Chest X-ray reveals diffuse bilateral airspace opacities consistent with bilateral pneumonia.

Figure 2. Chest CT on Admission .

Multifocal consolidation with ground glass opacities are seen.

Figure 3. EKG on Admission .

EKG reveals atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with a heart rate of 133 beats per minute.

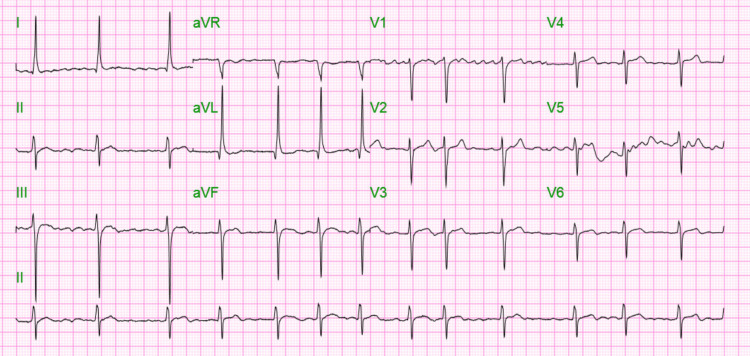

The patient was treated with cardizem drip which was eventually switched to oral amiodarone and metoprolol; serial EKGs showed sustained atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular rate (Figure 4). The patient was medically managed for type 2 myocardial infarction. Cardiac catheterization and echocardiogram could not be done due to the patient’s unstable condition, but in view of the patient’s quick drop in troponin (Table 2) type 2 myocardial infarction is extremely likely. On day three, the patient began to desaturate to 80-85% and was using accessory muscles for respiration and so was intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. The patient’s sputum culture also began growing Klebsiella pneumoniae extended-spectrum beta-lactamase which was treated with gentamicin. Dexamethasone was started for COVID-19 on admission. The patient’s neurological exam and brainstem reflexes were normal, and improvement was noted in the patient's respiratory parameters on a spontaneous breathing trial. A weaning trial off the ventilator was thus attempted but failed, and a tracheostomy was ultimately performed on day 21 of hospitalization. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tube placement was planned, but the patient coded and died on day 23 of hospitalization.

Table 2. Troponin Trend.

| On admission | Hour 8 | Hour 16 | Day 2 | Day 7 | |

| High Sensitivity Troponin (Normal Range: 0.0 - 17.0 nanograms per liter) | 20,334.6 nanograms per liter | 21,049.0 nanograms per liter | 21,250.0 nanograms per liter | 2,817.3 nanograms per liter | 799.1 nanograms per liter |

Figure 4. EKG Post-Cardizem Drip.

EKG shows atrial fibrillation with a controlled heart rate of 79 beats per minute.

Discussion

Infection with the COVID-19 virus has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes including arrhythmias, myocarditis, and myocardial infarction. It has been linked with the development of new-onset atrial fibrillation and with a poor prognosis [3]. These effects may be attributed to the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptors on the myocardium [5]. Atrial fibrillation has been more prominently observed in patients with predisposing chronic cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension [2]. Other associated risk factors include diabetes, older age, heart failure, and renal impairment [2, 6].

There are several factors that have been presumed to play a role in the progression of new-onset atrial fibrillation. These factors include the involvement of ACE-2 receptors, inflammatory cytokine storm, electrolyte abnormalities, direct endothelial damage, and acid-base disorders [5, 7]. Additionally, a correlation has been observed between disease severity and the development of new-onset atrial fibrillation [3]. There is an increased incidence of AFIB in patients who experience renal deterioration, thrombotic complications, hypoxia, the need for critical care, and a longer length of hospital stay. The risk of new-onset AFIB has also been associated with an increased level of epicardial adipose tissue [8].

In this case, the patient developed acute myocardial infarction with new-onset atrial fibrillation during acute COVID-19 infection. Our patient also had sepsis which could have triggered or contributed to the development of atrial fibrillation. In a study based on the American Heart Association’s COVID-19 cardiovascular registry, the incidence of new-onset AFIB was 5.4% [3]. Among those with new-onset AFIB, the incidence of myocardial infarction was 9.8% while the incidence of myocardial infarction was 2.7% in COVID-19 patients without AFIB. An association was found between new-onset atrial fibrillation and major adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction.

New-onset atrial fibrillation has been associated with worsening clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients [9]. It is a life-threatening complication that is associated with a two-fold increase in mortality and a three-fold increase in secondary outcomes. Secondary outcomes due to new-onset AFIB include major adverse cardiovascular events such as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, new-onset heart failure, stroke, and cardiogenic shock. Other adverse outcomes include the need for critical care, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, renal replacement therapy, and thromboembolic complications. New-onset AFIB has been associated with a higher incidence of embolic events [10].

Management of new-onset atrial fibrillation in COVID-19 patients is focused on rate control [11]. The use of beta-blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers is the mainstay for long-term management after stabilization. In patients with acute decompensation, intravenous digoxin or amiodarone is used for rate control and stabilization [12]. The use of anticoagulation with warfarin, novel oral anticoagulants, or low molecular weight heparin based on risk factors is indicated to reduce thromboembolic risk [13].

Conclusions

Here we present a case of new-onset atrial fibrillation and type 2 myocardial infarction in a patient that presented with COVID-19 pneumonia. To our knowledge, this is the first case that documented both new-onset atrial fibrillation and acute myocardial infarction in a single patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. It is important to be on the lookout for cardiovascular complications, like atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction in patients presenting with COVID-19.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Covid-19 and the cardiovascular system: a comprehensive review. Azevedo RB, Botelho BG, Hollanda JV, et al. J Hum Hypertens. 2021;35:4–11. doi: 10.1038/s41371-020-0387-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID-19 associated atrial fibrillation: Incidence, putative mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Gawałko M, Kapłon-Cieślicka A, Hohl M, Dobrev D, Linz D. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;30:100631. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.New-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: results from the American Heart Association COVID-19 cardiovascular registry. Rosenblatt AG, Ayers CR, Rao A, et al. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:0. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Special article - acute myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection: a review. Bavishi C, Bonow RO, Trivedi V, Abbott JD, Messerli FH, Bhatt DL. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Body localization of ACE-2: on the trail of the keyhole of SARS-CoV-2. Salamanna F, Maglio M, Landini MP, Fini M. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:594495. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.594495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.COVID-19, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases: should we change the therapy? Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Mancia G, Dell'Oro R, Grassi G. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158:104906. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. Kochi AN, Tagliari AP, Forleo GB, Fassini GM, Tondo C. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:1003–1008. doi: 10.1111/jce.14479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation in COVID-19 is associated with increased epicardial adipose tissue. Slipczuk L, Castagna F, Schonberger A, et al. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2022;64:383–391. doi: 10.1007/s10840-021-01029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prognostic significance of new-onset atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction following acute myocardial infarction: data from the NOAFCAMI-SH registry. Hao C, Luo J, Liu B, et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:479–493. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S358349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New-onset atrial fibrillation during COVID-19 infection predicts poor prognosis. Pardo Sanz A, Salido Tahoces L, Ortega Pérez R, González Ferrer E, Sánchez Recalde Á, Zamorano Gómez JL. Cardiol J. 2021;28:34–40. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New-onset atrial fibrillation in COVID-19 infection: a case report and review of literature. Shah D, Umar Z, Ilyas U, Nso N, Zirkiyeva M, Rizzo V. Cureus. 2022;14:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atrial arrhythmias in a patient presenting with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) infection. Seecheran R, Narayansingh R, Giddings S, et al. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:2324709620925571. doi: 10.1177/2324709620925571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation in COVID-19 patients. Tomaszuk-Kazberuk A, Koziński M, Domienik-Karłowicz J, et al. Cardiol J. 2021;28:758–766. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2021.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]