Abstract

Objective:

Ineffective meetings have been well-documented as presenting considerable direct (e.g., salary) and indirect costs (e.g., employee burnout). We explore the idea that people need meeting recovery, or time to transition from meetings to their next task. Doing so may reduce employee burnout.

Methods:

We used a quantitative survey of working adults’ last meeting to determine the relationship between meeting outcomes (satisfaction and effectiveness) and meeting recovery.

Results:

We found that meeting outcomes are related to meeting recovery and that relationship is moderated by the degree to which the meeting was relevant to the individual. Implications for theory and practice are discussed in order to provide concrete recommendations for researchers, managers, and consultants.

Conclusions:

This study explores virtual meeting fatigue with a focus on meeting quality, and explores the need for recovery after workplace meetings.

Keywords: workplace meetings, virtual meeting fatigue, meeting recovery, team meetings, meeting transition time

Meetings have increasingly become a key organizational tool for employees to exchange information, monitor progress, and strengthen social relationships (1, 2). However, employees have characterized meetings as disruptive (2) and a waste of time (3). Such ineffective meetings have been associated with direct costs in the form of salary and benefits derived from employee time spent in meeting preparation and preparation (3, 4). Significant indirect costs are also associated with stress and fatigue (5) and opportunity costs (i.e., time lost for other work activities) (3). With the recent massive switch from face-to-face to virtual meetings, a new potential source of fatigue has emerged, virtual meeting fatigue (6). Virtual meeting fatigue appears to exist even when the meetings being attended are considered necessary (7).

However, good meetings are essential in providing organizations with means to facilitate important decision-making, essential collaboration, and team cohesion and productivity (8). The current study sought to explore the transition from both good and bad virtual meetings to work, with a particular interest in meeting recovery, or the time spent after a meeting in recovering and transitioning to another task or meeting. We know that meetings have the potential to either provide a boost to employee engagement (8) or create the onset of burnout (9). We believe that meeting recovery may enable even bad meetings to have a lesser impact on employee well-being. Further, we explore how the relevance of a given meeting can impact the relationship between meeting outcomes and meeting recovery, perhaps nullifying the fatigue and transition time needs.

Meeting Science and the Virtual Meeting

Early in the development of meeting science, Schwartzman (10) defined meetings as focused communicative gatherings of two or more individuals for the purpose of work or group-related interaction. Workplace meetings tend to have more structure than simple chats but less than a lecture, last an average of 30 to 60 minutes, and are conducted in various modalities (2). Meetings vary in regards to purpose, interactions, and design characteristics (1, 11).

Prior to March 2020, nearly 80% of all meetings were face-to-face, which was reflected in the focus on meeting science (12). Following the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, virtual meetings soared to over 60% of all meetings in March 2020 (12). Employees found themselves grappling with meeting-related fatigue perhaps more commonly known as “Zoom fatigue” and “Webex weariness” (13, 14). In contrast, virtual meetings were found to be nearly as satisfying and effective as face-to-face meetings, even though meeting-related fatigue increased during this time (12). This demonstrates that virtual meetings may have other redeeming qualities, such as time saving or even being more “green” in terms of carbon emissions that compensate for some of the inherent challenges (15).

In this research, we focus on the reactions to virtual meetings and how these reactions relate to the need for both transition time and recovery. Specifically, we investigate the possibility that when people attend virtual meetings, they turn off their camera feeling some level of drain and may struggle to efficiently return to productive activities.

Meeting Recovery

Although there is a growing body of research on meetings and their outcomes (see Mroz, Allen, Verhoeven and Shuffler (16) for a summary), little research has focused on how attendees overcome the disruptive nature of workplace meetings (2). We define meeting recovery as the time spent by an individual after group and team meetings recovering and transitioning to the next task/meeting (17, 18). Neuroscience and cognitive psychology research suggests humans need time for task switching, or the unconscious ability to switch attention from one task to another (19) as well as cognitive shifting, which is the active conscious effort to mentally switch attention between tasks (20). We explore the meeting recovery as the mechanism by which meeting attendees transition between tasks and overcome the disruptive nature of workplace meetings.

Meeting Outcomes, Meeting Recovery, and Transition Time

We expect that regardless of the outcomes of the virtual meeting, some level of meeting recovery and transition time will be needed. Meeting outcomes refer to meeting satisfaction and effectiveness (21). Meeting satisfaction refers to meeting participants feeling that the meeting went well (22). Meeting effectiveness refers to the degree to which meeting participants believe the meeting efficiently accomplished its stated goals (23). Meeting effectiveness has been linked to employee engagement and empowerment (22). Further, we know that both meeting satisfaction and effectiveness are positively related to employee engagement and negatively related to employee burnout (9). That is, the better the meeting, the more engaged employees are likely to become. The worse the meeting, the more likely the meeting will contribute to overall feelings of burnout, which is tied to a variety of health and well-being outcomes both immediately and long-term (24). Given these previous research findings, we anticipate the effect of both meeting satisfaction and effectiveness will behave similarly in relation to meeting recovery and transition time, and that meeting outcomes will negatively relate to meeting recovery and transition time. The following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

Meeting satisfaction is negatively related to both (a) meeting-to-work transition time and (b) meeting recovery.

Hypothesis 2:

Meeting effectiveness is negatively related to both (a) meeting-to-work transition time and (b) meeting recovery.

Meeting Relevance as a Moderator

Although we expect a direct relationship between meeting outcomes and meeting recovery, that relationship may be impacted by meeting relevance. Meeting relevance refers to the degree to which the meeting is perceived as pertinent to meeting participants (8). We expect that meeting relevance may moderate the meeting outcomes to meeting recovery and transition time relationships. Meeting relevance may strengthen the magnitude of the negative relationship between meeting satisfaction/effectiveness and meeting recovery/transition time. When meeting relevance is high, we expect the relationships to be stronger. The following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a:

The negative relationship between meeting satisfaction and meeting recovery is moderated by meeting relevance, such that the negative relationship is stronger when the meeting is more relevant.

Hypothesis 3b:

The negative relationship between meeting effectiveness and meeting recovery is moderated by meeting relevance, such that the negative relationship is stronger when the meeting is more relevant.

Hypothesis 4a:

The negative relationship between meeting satisfaction and meeting-to-work transition time is moderated by meeting relevance, such that the negative relationship is stronger when the meeting is more relevant.

Hypothesis 4b:

The negative relationship between meeting effectiveness and meeting-to-work transition time is moderated by meeting relevance, such that the negative relationship is stronger when the meeting is more relevant.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Following receipt of IRB approval, participants were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an electronic survey platform, from April 15, 2020 to April 30, 2020. Survey items were counter-balanced to ensure there were no order effects based on item placement on the survey (25). Participants were required to be 18 years of age, full-time employees within the United States, and attend more than one work meeting each week. A total of 495 participants responded to the survey and were compensated ($0.75 each). Participants whose last meeting was not virtual, who did not attend work-related meetings, or were not full-time employees were excluded (n = 300). The final sample was 195 participants, 37.44% of whom were female. The mean age of participants was 37.44 years old (SD = 10.26). The average tenure in their current job was 6.55 years (SD = 6.50) and the average tenure in their current organization was 7.48 years (SD = 6.72). The average number of meetings per week was 3.64 (SD = 3.57) and the average number of hours in meetings per week was 4.42 hours (SD = 5.92).

Measures

All the items used in the current study are presented in Appendix B for reference.

Meeting Effectiveness.

A six-item scale that has been used in previous research was used to evaluate meeting effectiveness (26). Participants were asked to indicate how effective their last workplace meeting was relative to each presented statement.

Meeting Satisfaction.

A six-item scale was used to evaluate meeting satisfaction (1). Participants were asked to think about their last workplace meeting and indicate which of the following words described that meeting: stimulating, boring, unpleasant, satisfying, enjoyable and annoying.

Meeting Recovery.

We created a new measure of meeting recovery since this is the first empirical study focusing on this phenomenon. The question read “Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements concerning your last meeting…” A total of 16 items followed. Upon data collection, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the final usable sample, as this approach is accepted as best practice (27) and EFA is necessary to create a calculation method that represents an important underlying latent dimension(s) or construct(s) expressed in observed variables (28). Our decision logic was to determine if the finished scale was unidimensional or multidimensional, and, if multidimensional, how many variables (dimensions) were used in the instrument. Factors were extracted and rotated using varimax rotation and the initial analysis resulted in a two-factor solution (see Table 1). The following items falling into the second factor were removed: those that were negatively worded (29), the valence was unclear, or did not apply equally across individuals. Measures 6 and 10 were also eliminated due to the timing of the data collection occurring during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and their relevancy being limited. The final measure included 11 items (see Appendix A).

Table 1:

Exploratory Factor Analysis of Meeting Recovery Measure

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I needed time to recover after my last meeting before moving on to other work-related tasks. | 0.74345 | 0.32276 |

| 2. My last meeting created problems I had to resolve before I could get back to my work tasks. | 0.69591 | 0.41077 |

| 3. After my last meeting I had an increased desire to share/brainstorm/connect with others. * | 0.09935 | 0.79857 |

| 4. I spent time mulling over my last meeting experience. | 0.43672 | 0.66211 |

| 5. My last meeting set the tone for the rest of that day. * | 0.31583 | 0.66142 |

| 6. My last meeting affected me even after I went home that day. * | 0.58882 | 0.47158 |

| 7. After my last meeting it was hard to be fully engaged in other work tasks. | 0.83030 | 0.22995 |

| 8. My work performance was inhibited after my last meeting. | 0.82380 | 0.24405 |

| 9. I was motivated to do action items from the meeting right away. * | −0.12209 | 0.80792 |

| 10. I wanted to go home early after my last work meeting. * | 0.82414 | 0.15025 |

| 11. After my last meeting I had a decreased desire to attend meetings in the future. | 0.78484 | 0.01367 |

| 12. I was frustrated after my last meeting. | 0.84251 | 0.05791 |

| 13. It took me a long time to recover after my last meeting. | 0.86430 | 0.17382 |

| 14. I distracted myself from work for some time after my last meeting. | 0.83488 | 0.13930 |

| 15. It was tough to transition back to meaningful work tasks after my last meeting. | 0.89174 | 0.16649 |

| 16. It took some effort to get back to work after my last meeting. | 0.88113 | 0.17510 |

Note:

indicates removed from final item list (see Appendix A)

Time to Work.

Participants were asked to indicate how many minutes it took them to transition back to work-related tasks after their last meeting.

Meeting Relevance.

A seven-item scale adapted from a goal and process clarity scale was used to evaluate meeting relevance (30).

Demographic Variables.

Demographic questions included gender identity, age, tenure at the organization and in the occupation, hours worked per week, number of meetings per week, and number of hours spent in meetings.

Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation for continuous variables or number and percentage for categorical variables. Assessment for normality was performed. Correlations and alpha reliability were calculated adjusted for gender and tenure in the current organization, as each of these variables has a correlation with the predictor and outcome variables. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Table 2 contains the means, standard deviations, correlations, and alpha reliability estimates for all the focal variables. Correlation analyses indicate no relationship between most meeting outcomes and meeting-to-work transition time. However, there is a statistically significant relationship between meeting recovery and transition time (r = 0.37, p < 0.05). Other relationships are in the direction anticipated.

Table 2:

Means, Standard Deviations, Intercorrelations, and Alpha Reliability Estimates for Study Variables.

| Measure | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Meeting Satisfaction | 4.80 | 1.33 | (.85) | ||||||||||

| 2. Meeting Effectiveness | 3.63 | 0.79 | .72** | (.88) | |||||||||

| 3. Meeting Relevance | 4.92 | 1.46 | .66** | 0.73** | (.93) | ||||||||

| 4. Meeting Recovery | 2.82 | 1.51 | −.36** | −.20** | −.23** | (.95) | |||||||

| 5. Transition Time | 20.22 | 23.30 | −.08 | −.05 | −.07 | .37** | — | ||||||

| 6. Tenure (pos.) | 6.55 | 6.50 | .10 | .10 | −.06 | .19** | .10 | — | |||||

| 7. Tenure (org.) | 7.48 | 6.72 | .07 | .04 | .07 | −.11 | −.08 | .51** | — | ||||

| 8. Age | 37.44 | 10.26 | .00 | −.01 | −.04 | −.05 | −.06 | .41** | .55** | — | |||

| 9. Gender | — | — | −.01 | .05 | .05 | −.11 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .20** | — | ||

| 10. Meetings per week | 3.64 | 3.57 | −.05 | −.14 | −.06 | .05 | −.03 | −.01 | .10 | −.01 | −.09 | — | |

| 11. Hours in meetings per week | 4.42 | 5.92 | −.05 | −.04 | −.03 | −.01 | .02 | .02 | .09 | .03 | −.02 | .40** | — |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In looking at the specific correlations between meeting satisfaction, effectiveness, and recovery, we note that they are relatively high (r = 0.66 to 0.72). A confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test whether a one-factor solution (CFI = 0.65, TLI = 0.58, χ2 = 863.89, df = 152, RMSEA = 0.14) versus a three-factor solution (CFI = 0.80, TLI = 0.75, χ2 = 508.34, df = 149, RMSEA = 0.09) would be a better fit for the measurement model. Using the chi-square difference test, results indicate the three-factor model fits better than the one-factor model (Δχ2 = 355.55, Δdf = 3, p < 0.05), and the general fit of the three-factor model suggests discriminant validity evidence for the three interrelating constructs. We then felt comfortable to tentatively proceed with hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis 1 stated that meeting satisfaction would negatively relate to both meeting-to-work transition time and meeting recovery. Correlations (Table 1) indicate a statistically significant and meaningful negative correlation between meeting satisfaction and meeting recovery (r = −0.36, p < 0.05), but not between meeting satisfaction and transition time (r = −0.08, p > 0.05), landing partial support to the first hypothesis. To further test the hypothesis, we performed regression analysis to explore the relationship between meeting satisfaction and recovery further. The results indicated that meeting satisfaction significantly predicted meeting recovery when controlling for gender and organizational tenure (β = −0.40, p < 0.05).

Hypothesis 2 stated that meeting effectiveness would negatively relate to both meeting-to-work transition time and meeting recovery. Correlations (Table 1) indicate a statistically significant and meaningful negative correlation between meeting effectiveness and meeting recovery (r = −0.20, p < 0.05), but not between meeting effectiveness and transition time (r = −0.05, p > 0.05), lending partial support to the first hypothesis. To further test the hypothesis, we performed regression analysis to explore the relationship between meeting effectiveness and recovery further. The results indicated that meeting effectiveness significantly predicted meeting recovery when controlling for gender and organizational tenure (β = −0.37, p < 0.05).

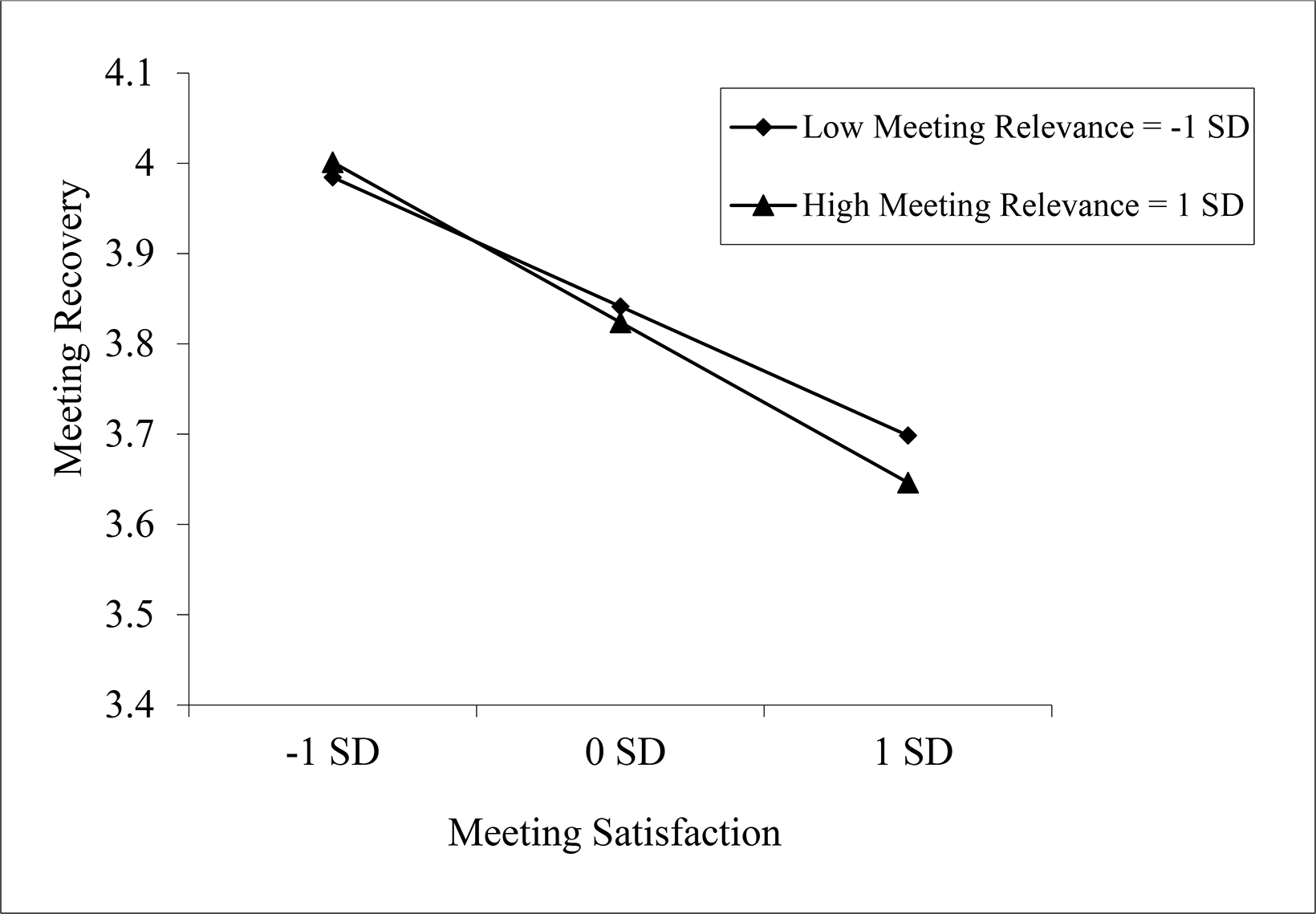

Hypothesis 3a stated that meeting relevance would moderate the negative relationship between meeting satisfaction and meeting recovery in that the negative relationship would be stronger when the meeting was deemed more relevant. We performed regression analysis to confirm the direct negative relationship (β = −0.40, p < 0.05) and then entered the interaction between meeting satisfaction and meeting relevance in the next step (see Table 3). Results indicated a statistically significant interaction effect (β = −0.18, p < 0.05), with the interaction explaining an additional 7% of the variance in meeting recovery. The interaction was graphed (see Figure 1) and these findings lend support to Hypothesis 3a.

Table 3:

Regression Analysis of Meeting Satisfaction and Effectiveness Regressed onto Meeting Recovery with Meeting Relevance as a Moderator

| Variables | Controls | Meeting Satisfaction | Meeting Effectiveness | Satisfaction Moderation Model | Effectiveness Moderation Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | ||||

| Controls | |||||||

| Gender | −0.35 | −0.36 | −0.32 | −0.39 | −0.48* | −0.36 | −0.42* |

| Tenure (org.) | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Meeting Process | |||||||

| Meeting Satisfaction | −0.40** | −0.39** | 0.38 | ||||

| Meeting Effectiveness | −0.37** | −0.14 | 0.82* | ||||

| Meeting Relevance | −0.02 | 0.83** | −0.17 | 0.61* | |||

| Interaction | −0.18** | −0.22** | |||||

|

| |||||||

| F | 2.41 | 10.88 | 4.27 | 8.14 | 10.49 | 4.24 | 5.15 |

| p | 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.006 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.0002 |

| R 2 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| ΔR2 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01

n=195

Figure 1:

Meeting Relevance Moderating the Meeting Satisfaction to Meeting Recovery Relationship

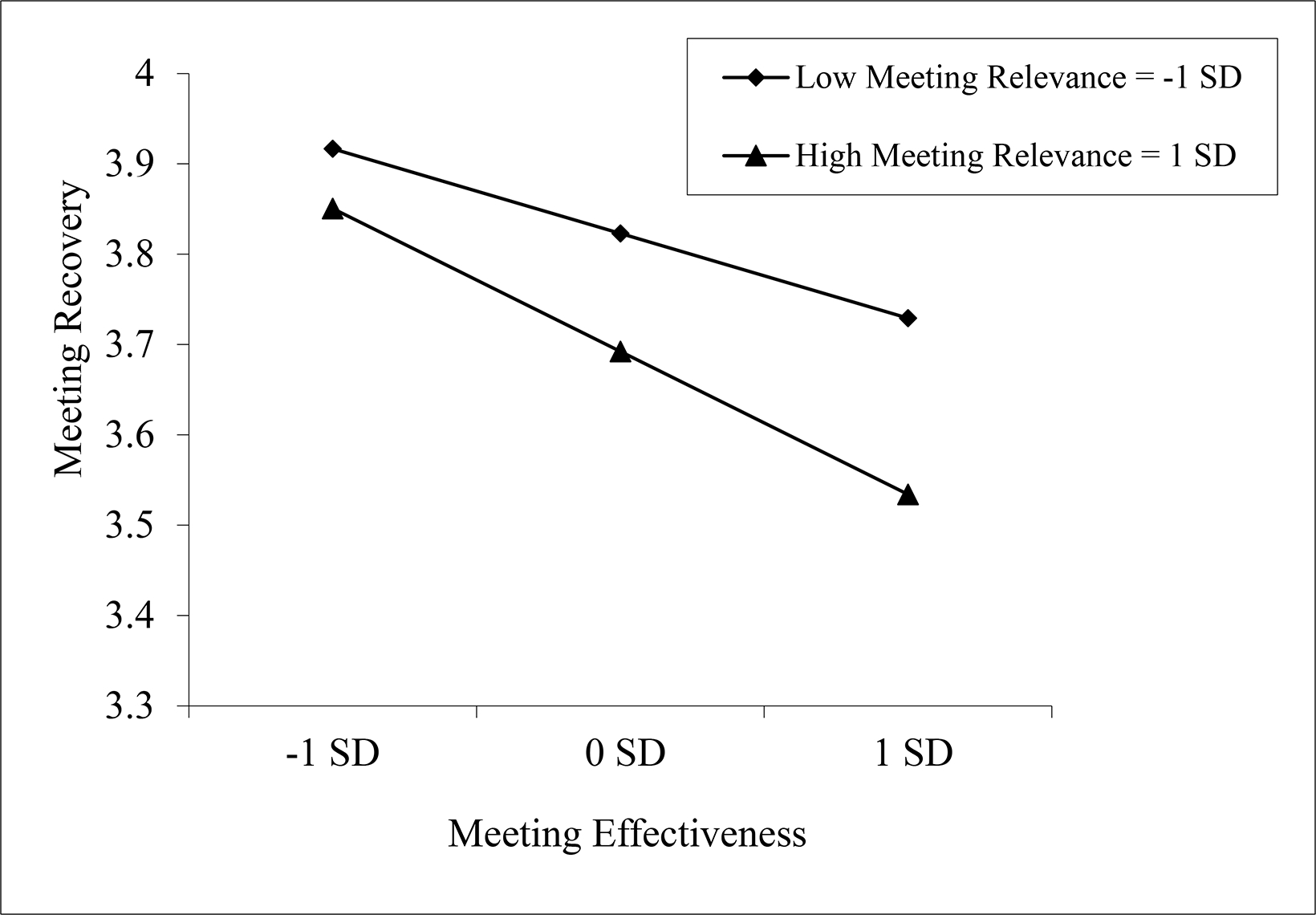

Hypothesis 3b stated that meeting relevance would moderate the negative relationship between meeting effectiveness and meeting recovery in that the negative relationship would be stronger when the meeting was deemed more relevant. We performed regression analysis to confirm the direct negative relationship (β = −0.37, p < 0.05) and then entered the interaction between meeting satisfaction and meeting relevance in the next step (see Table 3). Results indicated a statistically significant interaction effect (β = −0.22, p < 0.05), with the interaction explaining an additional 4% of the variance in meeting recovery. The interaction was graphed (see Figure 2) and the pattern of the relationship was different than expected. At lower levels of meeting relevance, the relationship between meeting effectiveness and meeting recovery, the slope of the line becomes positive. This suggests that at low levels of meeting relevance, increasing meeting effectiveness accompanies increasing meeting recovery. At high levels of meeting relevance, the positive and negative relationships essentially go away (i.e., the slope of the line approaches flat). These findings lend some support to Hypothesis 3b, though with noted differences.

Figure 2:

Meeting Relevance Moderating the Meeting Effectiveness to Meeting Recovery Relationship

Hypotheses 4a and 4b were not further probed due to the lack of statistically significant and meaningful relationships between meeting outcomes and transition time.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the negative relationship between virtual meeting outcomes (i.e. meeting satisfaction and effectiveness) and both meeting recovery and meeting-to-work transition time. The results indicate support for the inverse relationship between both predictors of meeting satisfaction and effectiveness with the outcome of meeting recovery. Individuals express less of a need to recover following meetings perceived as having higher levels of satisfaction and/or effectiveness. Individuals who have a poor perception of either satisfaction or effectiveness require more recovery time. Given the propensity of numerous meetings (31) that are scheduled back-to-back (12), it appears to be more important to ensure that our meetings are of higher overall quality or to schedule longer recovery between meetings if quality cannot be improved.

To our surprise, meeting outcomes did not relate to meeting-to-work transition time. It was hypothesized and generally supported by theory that as meetings got better, the need for time to transition to other activities would be reduced. However, the inverse relationship was not statistically significant, nor was there a sufficiently strong correlation to indicate issues with ability to detect the effect. One reason for the lack of findings here may be a function of the measurement approach. While participants were asked how long it took them to transition after their last meeting to their work, their schedule may not be within their control. How much time they had and how much time they needed are two different, and in this case, conflated measures.

We found support for meeting relevance moderating the negative relationships between meeting satisfaction and effectiveness with meeting recovery from the moderation analyses. The nature of the moderation was consistent with the hypotheses for meeting satisfaction and recovery. More relevant meetings showed a stronger inverse relationship with recovery time than less relevant meetings. Employees appear to benefit more greatly in terms of recovery when the outcomes are more satisfying and effective.

Our findings on the moderation effect of meeting relevance on the meeting effectiveness to meeting recovery relationship were different than was hypothesized. When meetings are particularly relevant, the relationship between meeting effectiveness and recovery is positive. As the effectiveness of the relevant meeting increases, so does the time needed for recovery. It may be that relevant meetings have a greater impact on the work of those in the meeting (8). Attendees of relevant meetings may wish to ruminate, consider the results, and process the meaning of the meeting outcomes, which will increase recovery time.

Implications for research

These data suggest that there are intricate and complex relationships between meeting effectiveness, perceived relevancy, and the recovery time needed for each individual. The inverse relationships demonstrated in these data suggest that there is a meaningful relationship between these three factors. Additional research will yield possibilities for high-impact interventional studies to improve meeting effectiveness and relevancy and reduce recovery time. There may be differences in recovery thoughts, emotions, and activities that differ between different levels of meeting effectiveness or relevancy. Specific meeting recovery activities can be explored to gain additional insight into the coping practices of individuals and how these may relate to longer or shorter recovery times.

A key implication of the findings is that people need recovery after both good and bad meetings. However, people generally experience back-to-back meetings with one stopping and another starting right after the other (12). The problem, when do people recover? Future research needs to investigate the implications of back-to-back meetings for recovery and important health outcomes, such as burnout. We assumed that recovery has the potential to mitigate the effect of bad meetings on employee burnout. This was a premise of the forgoing study. In a back-to-back meetings situation, with recovery not coming perhaps for hours, if it happens at all, will likely exacerbate burnout. This could lead to a variety of negative outcomes, including general attentional resource drain leading to safety issues at work.

Another research implication is that these relationships were assessed assuming a constant linear relationship between perceived effectiveness and relevance and the outcome of meeting recovery. There may be a curvilinear relationship between these meeting metrics where extremely engaging or hyper-efficient meetings may require much more recovery time than a moderately engaging meeting. Similarly, if meetings have no relevancy, meeting recovery is possibly very low. There may be a “sweet spot” of relevance and effectiveness for productive meetings and the subsequent need of meeting recovery.

A final research implication is the many potential theoretical explanations for the current findings. For example, conservation of resources theory (32, 33) asserts that people have a finite amount of physical, emotional, and cognitive resources that they use throughout the day to respond to stimuli in their environment. As they respond, they use those resources and are motivated to conserve them, as well as rejuvenate them where possible. Previous meetings research have used this theoretical framework for understanding how meetings have the capability to energize or drain employees, including both engagement and burnout as outcomes (9). In the case of the current study, meetings serve as a drain upon people’s resources, at least in some cases. This may cause stress related symptoms, requiring people to cope, and the method of coping we believe people engage in is meeting recovery. The resource drain and recovery idea is consistent with conservation of resources theory, as well as action theory (5), theory of activity regulation (34), and attention restoration theory (35). Thus, there are a number of theoretical implications and theories that support the forgoing findings as currently presented.

Implications for practice

Scheduling recovery time between meetings can help improve productivity and reduce burnout. Individuals can use these results to appropriately schedule recovery time between meetings, with approximate lengths based on the level of relevance. Similarly, organizers and managers who are mindful of these relationships can appropriately set expectations or schedule meetings to allow for appropriate recovery time. They can also tailor their meetings to try to achieve a desirable amount of relevance and efficacy and achieve a balance between the efficiency and productivity of their teams.

One way to accomplish this would be to adjust all meetings to end five to ten minutes earlier than originally scheduled. The default calendar systems suggest 30 minute and 60 minute meetings. Our findings would suggest considering making those meetings 25 and 50 minutes instead. Doing so would enable recovery, likely reduce burnout, and may have implications for improving overall safety within a variety of occupations (e.g. construction, first responders, and so on).

Limitations and Strengths

This is a cross-sectional study and therefore unable to demonstrate temporality and suggest a possible causal relationship between meeting effectiveness, relevancy, and recovery time. This study relied upon a convenience sample from a large, diverse sample and these results may be stronger in specific populations. Participants were asked about their most recent workplace meeting, resulting in a heterogeneous type of meeting type, purpose, and duration. While these results may be more generalizable, there may be specific types of meetings in which these relationships are either stronger or weaker. The only meeting modality included in this study was virtual. Participants were asked about their meeting modality and the face-to-face, hybrid and teleconference group sizes were relatively small, due in part to the timing of the data collection (i.e. during the COVID-19 pandemic). The limited sample size in these groups did not produce enough statistical power to include in the analyses. Additionally, based on the sample description and results shared, the sample was likely lower level managers or entry level employees, which may impact the kinds of meetings they have, and also affect the likelihood of them participating in back-to-back meetings. These factors narrow the generalizability of the sample a bit further. Regardless, most of these limitations can be addressed through further research as COVID-19 wanes and additional sampling strategies are considered and deployed.

There are many strengths of this study, including a relatively large sample size from a diverse array of work types, suggesting that these data may be generalizable to a wide population of workers. This study also utilized many different metrics to quantify job satisfaction, meeting effectiveness, and meeting relevance. This is the first study to investigate and quantify meeting recovery in a scientific approach. The use of factor analysis to refine the metric for assessing meeting recovery was also novel.

Conclusion

The findings from this study confirm the popular belief that virtual meetings may create fatigue that requires recovery. Our hope is that the results will be of interest to meeting organizers and attendees so that they can justify humanizing the meeting experience by introducing recovery. We also postulate that in occupations where safety and risk exist, adding meeting recovery provides yet another way to mitigate resource drain, including burnout that is known to cause accidents and risk taking. Building in a bit of recovery time may be an important new practical process to deploy, something that will hopefully be confirmed by future research.

Acknowledgements:

University of Utah IRB_00130875

Funding sources:

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Appendix A. Items on Final Meeting Recovery Measure

| 1. I needed time to recover after my last meeting before moving on to other work-related tasks. |

| 2. My last meeting created problems I had to resolve before I could get back to my work tasks. |

| 3. I spent time mulling over my last meeting experience. |

| 4. After my last meeting it was hard to be fully engaged in other work tasks. |

| 5. My work performance was inhibited after my last meeting. |

| 6. After my last meeting I had a decreased desire to attend meetings in the future. |

| 7. I was frustrated after my last meeting. |

| 8. It took me a long time to recover after my last meeting. |

| 9. I distracted myself from work for some time after my last meeting. |

| 10. It was tough to transition back to meaningful work tasks after my last meeting. |

| 11. It took some effort to get back to work after my last meeting. |

Appendix B. Survey Questions

Age

What is your age (in years)?

Gender

What is your gender?

Male (1)

Female (2)

Other (3)

Race Ethnicity

What is your race/ethnicity?

Caucasian/White (1)

African American (2)

Hispanic (3)

Asian (4)

-

Other (5)

If other, please specify

Current Job

How long have you been at your current job (in years)?

Current Organization

How long have you been at your current organization in any job (in years)?

Work hours per week

How many hours do you work on average per week at your current job?

Meetings per week

How many work meetings do you attend per week?

Hours in meetings per week

How many hours do you spend in work meetings each week, on average?

Meeting Format

Please indicate what format your last meeting took.

Face to Face (1)

Teleconferencing (2)

Video Conferencing (e.g. Skype, Google Hangouts) (3)

Hybrid (4)

-

Other (5)

Please specify

Time since last meeting

How long ago was your last meeting (in days)?

Meeting Satisfaction

Please indicate your level of agreement with the follow words or phrases concerning your last meeting.

| Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat Disagree (3) | Neutral (4) | Somewhat Agree (5) | Agree (6) | Strongly Agree (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation (1) | |||||||

| Boring (2) | |||||||

| Unpleasant (3) | |||||||

| Satisfying (4) | |||||||

| Enjoyable (5) | |||||||

| Annoying (6) |

Meeting Effectiveness

Please rate how your last meeting was in:

| Extremely Ineffective (1) | Ineffective (2) | Neutral (3) | Effective (4) | Extremely Effective (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| achieving your own work goals. (1) | |||||

| achieving colleagues’ work goals. (2) | |||||

| achieving your department-section-unit’s goals. (3) | |||||

| providing you with an opportunity to acquire useful information. (4) | |||||

| providing you with an opportunity to meet, socialize, or network with people. (5) | |||||

| promoting commitment to what was said and done in the meeting. (6) |

Meeting Relevance

Please respond to each question indicating how you felt about yourself and your life in your LAST WORK MEETING, even if it is different from how you usually feel.

| Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat Disagree (3) | Neutral (4) | Somewhat Agree (5) | Agree (6) | Strongly Agree (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The meeting was relevant to my job. (1) | |||||||

| The meeting clarified my duties and responsibilities. (2) | |||||||

| The meeting clarified the goals and objectives for my job. (3) | |||||||

| The meeting helped me determine the appropriate procedures for my work tasks. (4) | |||||||

| The meeting helped ensure the procedures I use to do my job were correct and proper. (5) | |||||||

| The meeting helped me accomplish my duties and responsibilities. (6) | |||||||

| The meeting helped me complete the goals and objectives of my job. (7) |

Transition to work

How many minutes did it take you to transition to work-related tasks after your last meeting?

Meeting Recovery

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements concerning your last meeting.

| Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat Disagree (3) | Neutral (4) | Somewhat Agree (5) | Agree (6) | Strongly Agree (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I needed time to recover after my last meeting before moving on to other work-related tasks. (1) | |||||||

| My last meeting created problems I had to resolve before I could get back to my work tasks. (2) | |||||||

| After my last meeting I had an increased desire to share/brainstorm/connect with others. (3) | |||||||

| I spent time mulling over my last meeting experience. (4) | |||||||

| My last meeting set the tone for the rest of that day. (5) | |||||||

| My last meeting affected me even after I went home that day. (6) | |||||||

| After my last meeting it was hard to be fully engaged in other work tasks. (7) | |||||||

| My work performance was inhibited after my last meeting. (8) | |||||||

| I was motivated to do action items from the meeting right away. (9) | |||||||

| I wanted to go home early after my last work meeting. (10) | |||||||

| After my last meeting I had a decreased desire to attend meetings in the future. (11) | |||||||

| I was frustrated after my last meeting. (12) | |||||||

| It took me a long time to recover after my last meeting. (13) | |||||||

| I distracted myself from work for some time after my last meeting. (14) | |||||||

| It was tough to transition back to meaningful work tasks after my last meeting. (15) | |||||||

| It took some effort to get back to work after my last meeting. (16) |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: For Dr. Matt Thiese, a partnership between CDC and Abt Associates; a partnership between ACOEM and Reed Group; and working with FMCSA, Safelane Health, Utah State Bar for data access.

References

- 1.Cohen MA, Rogelberg SG, Allen JA, Luong A. Meeting design characteristics and attendee perceptions of staff/team meeting quality. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2011;15:90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogelberg SG, Leach DJ, Warr PB, Burnfield JL. “ Not another meeting!” Are meeting time demands related to employee well-being? Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogelberg SG, Shanock LR, Scott CW. Wasted Time and Money in Meetings:Increasing Return on Investment. Small Group Research. 2012;43:236–245. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Vree W Meetings, manners, and civilization: the development of modern meeting behaviour: Leicester University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luong A, Rogelberg SG. Meetings and more meetings: The relationship between meeting load and the daily well-being of employees. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2005;9:58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang M The reason Zoom calls drain your energy. BBC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shockley KM, Gabriel AS, Robertson D, et al. The fatiguing effects of camera use in virtual meetings: A within-person field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106:1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen JA, Rogelberg SG. Manager-led group meetings: A context for promoting employee engagement. Group & Organization Management. 2013;38:543–569. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Allen JA, Belyeu D. Our love/hate relationship with meetings: Relating good and bad meeting behaviors to meeting outcomes, engagement, and exhaustion. Management Research Review. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartzman HB. The meeting. The Meeting: Springer; 1989:309–314. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen JA, Beck T, Scott CW, Rogelberg SG. Understanding workplace meetings. Management Research Review. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed KM, Allen JA. Suddenly Virtual: Making Remote Meetings Work. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liz Fosslien MWD. How to Combat Zoom Fatigue. Harvard Business Review; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J A Neuropsychological Exploration of Zoom Fatigue. Psychiatric Times; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Standaert W, Muylle S, Basu A. Business meetings in a postpandemic world: When and how to meet virtually. Business Horizons. 2022;65:267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mroz JE, Allen JA, Verhoeven DC, Shuffler ML. Do we really need another meeting? The science of workplace meetings. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2018;27:484–491. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Geurts SA, Taris TW. Daily recovery from work-related effort during non-work time. Current perspectives on job-stress recovery: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Totterdell P, Spelten E, Smith L, Barton J, Folkard S. Recovery from work shifts: how long does it take? Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravizza SM, Carter CS. Shifting set about task switching: Behavioral and neural evidence for distinct forms of cognitive flexibility. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2924–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan X, Yu H. Different effects of cognitive shifting and intelligence on creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior. 2018;52:212–225. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen JA, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Rogelberg SG. Let’s get this meeting started: Meeting lateness and actual meeting outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2018;39:1008–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen JA, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Sands SJ. Meetings as a positive boost? How and when meeting satisfaction impacts employee empowerment. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69:4340–4347. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leach DJ, Rogelberg SG, Warr PB, Burnfield JL. Perceived meeting effectiveness: The role of design characteristics. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2009;24:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC public health. 2017;17:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Counterbalancing Corriero E. In: Allen M, ed. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017:278–281. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogelberg SG, Allen JA, Shanock L, Scott C, Shuffler M. Employee satisfaction with meetings: A contemporary facet of job satisfaction. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management. 2010;49:149–172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using multivariate statistics: Pearson Boston, MA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT. Exploratory factor analysis: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiStefano C, Motl RW. Further investigating method effects associated with negatively worded items on self-report surveys. Structural Equation Modeling. 2006;13:440–464. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer JE. Goal and process clarity: Specification of multiple constructs of role ambiguity and a structural equation model of their antecedents and consequences. Journal of applied psychology. 1992;77:130. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keith E 55 Million: A Fresh Look at the Number, Effectiveness, and Cost of Meetings in the U.S; 2015.

- 32.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American psychologist. 1989;44:513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied psychology. 2001;50:337–421. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zijlstra FR, Roe RA, Leonora AB, Krediet I. Temporal factors in mental work: Effects of interrupted activities. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1999;72:163–185. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett AA, Campion ED, Keeler KR, Keener SK. Videoconference fatigue? Exploring changes in fatigue after videoconference meetings during COVID-19. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106:330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]