Abstract

Background:

Recent evidence suggests that vitamin D might lower breast cancer mortality. There is also growing interest in vitamin D’s potential association with health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL). Associations between circulating 25OHD concentrations and HRQoL were examined prospectively among breast cancer survivors at the time of diagnosis and 1-year later.

Methods:

504 women with incident early-stage breast cancer at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center were included, and 372 patients provided assessments one year later. At each timepoint, participants provided blood samples and completed the SF-36 Health Survey, and surveys on perceived stress, depression, and fatigue. Season-adjusted serum 25OHD concentrations were analyzed in relation to HRQoL measures using multivariable logistic regression models.

Results:

Approximately 32% of participants had deficient vitamin D levels at diagnosis, which decreased to 25% at 1-year. Concurrently, although SF-36 physical health summary scores were lower at 1-year, mental health summary scores improved, and levels of depression and perceived stress were lower. In comparison to women with sufficient 25OHD levels (>30 ng/ml) at diagnosis, those who were deficient (<20 ng/ml) had significantly worse HRQoL at diagnosis and 1 year later. Vitamin D deficiency 1-year post-diagnosis was also associated with worse HRQoL, particularly among breast cancer survivors who took vitamin D supplements.

Conclusions:

Breast cancer survivors with vitamin D deficiency were more likely to report lower HRQoL than those with sufficient levels at the time of diagnosis and 1-year post-diagnosis.

Impact:

Our results indicate a potential benefit of vitamin D supplementation for improving breast cancer survivorship.

Keywords: vitamin D, health related quality-of-life, breast cancer survivorship, depression, perceived stress

BACKGROUND

Beyond its canonical functions in maintaining calcium and bone homeostasis, extensive research on vitamin D in the last few decades has revealed versatile extra-skeletal effects of this secosteroid hormone (1), which has led to the conduct of many randomized clinical trials to evaluate vitamin D supplementation in preventing cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and other conditions. The public and research enthusiasm towards vitamin D may have been driven in part by findings of a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in contemporary populations (2), where an increasingly sedentary lifestyle limits direct sun exposure and subcutaneous vitamin D synthesis. The deficiency might have been exacerbated by the obesity pandemic, as adipose tissue sequestrates the fat-soluble vitamin D from circulation.

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in breast cancer patients, with as many as 74% of women deemed deficient at the time of diagnosis (3). Observational data from our studies and others have shown an inverse association of vitamin D levels and breast cancer mortality (4,5), which are corroborated with data from two recently completed vitamin D trials and meta-analysis (6–8). In comparison to the large body of literature on vitamin D and breast cancer risk and mortality, relatively little research attention has been paid to health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL). Cancer diagnosis and treatment may have lingering adverse effects on a patient’s physical well-being. Moreover, breast cancer patients also experience higher levels of stress, fatigue, and depression than the general population, possibly due to cancer-related symptoms (9) and the fear of recurrence (10), all of which can compromise patients’ HRQoL.

A few recent observational and interventional studies shed some light on the potential benefits of vitamin D on improving HRQoL in cancer patients. In one study among colorectal cancer patients, higher concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) were associated with less fatigue and better global QoL (11). Similar findings were also reported in breast cancer patients (12) and in patients with advanced cancer in the palliative care setting (13). These associations might be attributed to vitamin D’s psychological effects such as regulating brain serotonin levels (14) and physical effects such as improving musculoskeletal strength (15). Considering the rapidly growing population of breast cancer survivors in the US, it will be clinically significant if it is shown that vitamin D supplementation can improve both survival and HRQoL.

In the current study based on a longitudinal cohort of 504 women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, we measured serum 25OHD concentrations at the time of diagnosis and 1-year later and examined associations with a series of HRQoL measures assessed at the same timepoints.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The study population consisted of primarily non-Hispanic White women with incident, histologically confirmed, early-stage breast cancer (Stage 0 to IIIa) being treated at Roswell Park Cancer Comprehensive Cancer Center who were enrolled in Roswell Park’s Databank and Biorepository (DBBR) and the Women’s Health after Breast Cancer (ABC) Study. Methods for the DBBR and ABC Study have been published elsewhere (16,17). Written consent was obtained from each patient participating in the DBBR and ABC study, which were conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines (e.g., Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS, Belmont Report, U.S. Common Rule) and approved by the institutional review board at Roswell Park. Participation rate in the DBBR was 42% (1648/3928) of all newly diagnosed breast cancer cases at Roswell Park. Women who were enrolled in the DBBR were subsequently asked to participate in the ABC Study. A total of 717 participants were enrolled into the ABC study between March 2006 and December 2012, for a participation rate of 44% of all newly diagnosed breast cancer patients recruited into DBBR (717/1648). Individuals recruited into the DBBR and ABC study had similar stage distributions to the underlying population of women diagnosed and treated for breast cancer at Roswell Park. Upon consent, participants provided a fasting blood sample at the time of diagnosis, prior to receipt of adjuvant therapy, as well as 12 months post-diagnosis, filled out comprehensive questionnaires at both time points, and underwent a series of anthropometric measurements by trained staff, including measures of height to the nearest 0.5 cm and weight measured by a Tanita® BC-418 segmental body composition scale. Body mass index was calculated in kg divided by height in meters squared.

Blood specimens were drawn in the hospital’s phlebotomy clinic, transported to the DBBR laboratories through a pneumatic tube system, processed, and frozen within one hour of draw and maintained at −80°C until analysis using a standardized protocol (16). A total of 213 women were excluded from the analysis because they either did not provide survey data at baseline (N=88), did not provide a blood sample at diagnosis (N=6), withdrew or were lost to followup (N=107), or were found to be ineligible after enrollment (N=12). Participants who provided a reason for withdrawing from the study most often reported being too busy or overwhelmed. For this analysis, research included 504 women who provided a blood sample at diagnosis and completed both DBBR and ABC study questionnaires. Of these, 372 of 428 (87%) participants who were eligible for their 1-year post diagnosis followup (i.e. enrolled by December 2011) provided a blood sample and completed a survey 1 year following their initial diagnosis.

Study Questionnaires

Participants completed self-administered surveys at the time of diagnosis and 1 year later, which collected information on demographic, lifestyle, and epidemiologic risk factors for breast cancer. At diagnosis, participants were asked in the DBBR questionnaire whether they took vitamin supplements (excluding multivitamins) at least once a week for one year sometime in the past 10 years. In a supplementary questionnaire in the ABC study, participants were asked 1-year post-diagnosis if they took any vitamins or minerals, other than a multivitamin, after their breast cancer diagnosis. Those indicating they took vitamin D supplements at least once per week were considered as supplement users while those who reported not using or taking vitamin D supplements less than once per week were considered non-users. Because many multivitamins contain lower levels of vitamin D compared to singular vitamin D supplements and the specific multivitamins taken were unknown, the focus of this study was on use of vitamin D supplements. The number of participants with data on use of vitamin D supplements was 458 (out of 504; 91%) at the time of diagnosis and 354 (out of 372, 95%) one year post-diagnosis.

The ABC study questionnaires also included several validated instruments to assess health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and symptoms commonly experienced by breast cancer patients. These included the SF36-version 2 Health Survey (SF-36) (18), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (19), the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (20), and the Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) scale (21,22). The SF-36 is designed to assess functional status, well-being, and general perceptions of health, and includes eight subscales that provide two summary scores: physical health summary score and mental health summary score, ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better HRQoL (18). The 10-item PSS was used to measure subjective stress, with items designed to reflect how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. The scale contains a number of direct queries about current levels of experienced stress (19). The summative score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. The widely used 20-item CES-D instrument was used to assess symptoms associated with depression, including feelings of depression, sadness, and loneliness. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. A standard cut-off score of 16 or greater was used to identify individuals at risk for clinical depression (23). The MAF survey contains 16 items that measures 4 dimensions of fatigue, i.e. severity, distress, timing, and degree of interference in activities of daily living, and is a revision of the Piper Fatigue Scale (21,24–26).

Vitamin D assays

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) concentrations at diagnosis and 1-year post diagnosis were measured by immunochemiluminometric assay on the DiaSorin Liasion automated instrument at Heartland Assays (Ames, IA, USA). The coefficient of variation (CV) based on technical quality control samples from Diasorin, with defined target values and acceptance criteria was 4.3%. 25OHD concentrations at the time of diagnosis were not influenced by the storage time of serum samples prior to their assay in October 2013 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Statistical Analysis

Assayed 25OHD concentrations were adjusted for seasonal effects using non-parametric locally weighted polynomial regression models (Proc Loess, SAS Institute, version 9.3), as previously described (27,28). Residuals from the local regression of 25OHD on week of blood draw were added to the overall population mean to create season-standardized 25OH concentrations. 25OHD levels were also adjusted for time held in storage at −80°C prior to assay. Season-adjusted 25OHD concentrations were defined as deficient (<20.0 ng/mL), insufficient (20.0–29.9 ng/ml), and sufficient (≥30 ng/ml).

Descriptive characteristics of study participants were summarized for the overall sample, and by use of vitamin D supplements at the time of diagnosis, 1-year post-diagnosis, and by change in vitamin D supplement use from diagnosis to 1-year post-diagnosis (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). Categories of change in vitamin D supplement use included participants who were non-users prior to diagnosis and 1-year post (no/no), those who became users after diagnosis (no/yes), and those who were users before and after diagnosis (yes/yes). The frequency of participants who stopped supplement use after diagnosis (yes/no) was low (N=24), excluding them from further analyses. The median and interquartile range were provided for continuous variables and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test for two- and three-tiered comparison groups, respectively. Frequencies and relative frequencies were provided for categorical variables and analyzed using Fisher’s exact or chi-squared tests for two- and three-tiered comparison groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of the Women’s Health After Breast Cancer Study at the time of diagnosis

| Characteristic | All women (N=504) | Vitamin D Supplement Use Prior to Diagnosis |

Vitamin D Supplement Use 1-Year Post-Diagnosis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, never, or occasionally (N=324, 70.7%) | Yes, at least once per week (N=134, 29.3%) | P-value | No, never, or occasionally (N=186, 52.5%) | Yes, at least once per week (N=168, 47.5%) | P-value | ||

|

| |||||||

| Age at diagnosis, years, median (IQR) | 56 (49–56) | 53.5 (47–62) | 62 (54–67) | <0.001 | 54.5 (47 – 64) | 57 (50 – 65) | 0.03 |

| Age at diagnosis group, n (%) | |||||||

| < 50 years | 138 (27.4%) | 111 (34.4%) | 14 (10.4%) | <0.001 | 62 (33.3%) | 35 (20.8%) | 0.009 |

| ≥ 50 years | 365 (72.6%) | 212 (65.6%) | 120 (89.6%) | <0.001 | 124 (66.7%) | 133 (79.2%) | |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||||||

| Premenopausal | 177 (35.1%) | 136 (42.0%) | 25 (18.7%) | <0.001 | 71 (38.2%) | 50 (29.8%) | 0.12 |

| Postmenopausal | 327 (64.9%) | 188 (58.0%) | 109 (81.3%) | 115 (61.8%) | 118 (70.2%) | ||

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 466 (92.5%) | 296 (91.4%) | 132 (98.5%) | 0.02 | 173 (93.0%) | 163 (97.0%) | 0.09 |

| Black | 30 (6.0%) | 21 (6.5%) | 2 (1.5%) | 10 (5.4%) | 2 (1.2%) | ||

| Other | 8 (1.6%) | 7 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.6%) | 3 (1.8%) | ||

| Education, n (%) | |||||||

| High school or less | 116 (23.0%) | 86 (26.5%) | 27 (20.1%) | 0.28 | 52 (28.0%) | 37 (22.0%) | 0.21 |

| Some college | 160 (31.7%) | 115 (35.5%) | 43 (32.1%) | 65 (34.9%) | 53 (31.5%) | ||

| College graduate (4 year) | 97 (19.2%) | 63 (19.4%) | 32 (23.9%) | 31 (16.7%) | 34 (20.2%) | ||

| Advanced degree | 87 (17.3%) | 55 (17.0%) | 31 (23.1%) | 31 (16.7%) | 41 (24.4%) | ||

| Missing | 44 (8.7%) | 5 (1.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 7 (3.8%) | 3 (1.8%) | ||

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||||

| Never | 244 (48.4%) | 167 (51.5%) | 74 (55.2%) | 0.41 | 92 (49.5%) | 94 (56.0%) | 0.57 |

| Former | 173 (34.3%) | 124 (38.3%) | 47 (35.1%) | 69 (37.1%) | 58 (34.5%) | ||

| Current | 42 (8.3%) | 27 (8.3%) | 13 (9.7%) | 17 (9.1%) | 11 (6.5%) | ||

| Missing | 45 (8.9%) | 6 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (4.3%) | 5 (3.0%) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28.6 (24–34) | 28.8 (24–34) | 28.3 (24–34) | 0.38 | 30.2 (26–35) | 26.8 (24–32) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index group, kg/m2, n (%) | |||||||

| <25 | 146 (29.0%) | 92 (28.5%) | 42 (31.3%) | 0.68 | 42 (22.6%) | 60 (35.7%) | 0.001 |

| 25–30 | 145 (28.8%) | 92 (28.5%) | 40 (29.9%) | 48 (25.8%) | 53 (31.5%) | ||

| ≥30 | 212 (42.1%) | 139 (43.0%) | 52 (38.8%) | 96 (51.6%) | 55 (32.7%) | ||

| Stage, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 70 (13.9%) | 41 (12.7%) | 23 (17.2%) | 0.003 | 30 (16.1%) | 26 (15.5%) | 0.32 |

| I | 256 (50.8%) | 152 (46.9%) | 81 (60.4%) | 85 (45.7%) | 88 (52.4%) | ||

| IIA | 103 (20.4%) | 74 (22.8%) | 18 (13.4%) | 44 (23.7%) | 27 (16.1%) | ||

| ≥IIB | 75 (14.9%) | 57 (17.6%) | 12 (9.0%) | 27 (14.5%) | 27 (16.1%) | ||

| ER status, n (%) | |||||||

| Positive | 386 (76.6%) | 247 (76.2%) | 108 (80.6%) | 0.52 | 141 (75.8%) | 135 (80.4%) | 0.01 |

| Negative | 104 (20.6%) | 67 (20.7%) | 24 (17.9%) | 36 (19.4%) | 33 (19.6%) | ||

| Not determined | 14 (2.8%) | 10 (3.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 9 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Breast Cancer Treatments | |||||||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||

| No | 269 (53.4%) | 158 (48.8%) | 86 (64.2%) | 0.003 | 104 (55.9%) | 102 (60.7%) | 0.45 |

| Yes | 201 (39.9%) | 144 (44.4%) | 37 (27.6%) | 78 (41.9%) | 64 (38.1%) | ||

| Missing | 34 (6.7%) | 22 (6.8%) | 11 (8.2%) | 4 (2.2%) | 2 (1.2%) | ||

| Radiation treatment | |||||||

| No | 129 (25.6%) | 86 (26.5%) | 33 (24.6%) | 0.22 | 50 (26.9%) | 42 (25.0%) | 0.72 |

| Yes | 353 (70.0%) | 228 (70.4%) | 92 (68.7%) | 136 (73.1%) | 126 (75.0%) | ||

| Missing | 22 (4.4%) | 10 (3.1%) | 9 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Hormonal treatment | |||||||

| No | 113 (22.4%) | 68 (21.0%) | 33 (24.6%) | 0.28 | 44 (23.7%) | 35 (20.8%) | 0.53 |

| Yes | 360 (71.4%) | 239 (73.8%) | 90 (67.2%) | 139 (74.7%) | 131 (78.0%) | ||

| Missing | 31 (6.2%) | 17 (5.2%) | 11 (8.2%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (1.2%) | ||

| Circulating 25OHD concentrations at diagnosis, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 23.8 (18–30) | 22.8 (17–28) | 27.6 (23–34) | <0.001 | 23.6 (17 – 28) | 25.9 (21 – 32) | <0.001 |

| Circulating 25OHD group at diagnosis, n (%) | |||||||

| Sufficient (>30 ng/ml) | 129 (25.6%) | 66 (20.4%) | 55 (41.0%) | <0.001 | 38 (20.4%) | 60 (35.7%) | <0.001 |

| Insufficient (20 to ≤30 ng/ml) | 215 (42.7%) | 139 (42.9%) | 61 (45.5%) | 79 (42.5%) | 77 (45.8%) | ||

| Deficient (<20 ng/ml) | 160 (31.7%) | 119 (36.7%) | 18 (13.4%) | 69 (37.1%) | 31 (18.5%) | ||

| Vitamin D supplementation prior to diagnosis | |||||||

| No, never, or occasionally | 324 (70.7%) | 324 (100%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 | 154 (86.5%) | 83 (50.9%) | <0.001 |

| Yes, at least once per week | 134 (29.3%) | 0 (0%) | 134 (100%) | 24 (13.5%) | 80 (49.1%) | ||

| SF-36 physical health summary score, median (IQR) | 95 (70–100) | 95 (75–100) | 90 (65–100) | 0.01 | 100 (70 – 100) | 95 (75 – 100) | 0.51 |

| SF-36 mental health summary score, median (IQR) | 70 (55–80) | 70 (55–80) | 75 (60–85) | 0.08 | 70 (55–80) | 75 (60–85) | 0.46 |

| Fatigue score, median (IQR) | 13.6 (7–24) | 13.1 (1.5–24) | 14.0 (7.5–23) | 0.39 | 12.8 (1 – 25) | 13.2 (7 – 23) | 0.72 |

| Perceived stress score, median (IQR) | 14 (8–19) | 14 (9–19) | 13 (7–19) | 0.37 | 13.0 (7 – 19) | 12.0 (7 – 18) | 0.79 |

| Depression Score, median (IQR) | 10.0 (5–17) | 11.0 (5–17) | 8.5 (3–17) | 0.14 | 9.5 (5 – 16) | 8.5 (4 – 16) | 0.35 |

| Depression Group, n (%) | |||||||

| No (<16) | 352 (69.8%) | 226 (69.8%) | 95 (70.9%) | 0.82 | 133 (71.5%) | 122 (72.6%) | 0.91 |

| Yes (≥16) | 152 (30.2%) | 98 (30.2%) | 39 (29.1%) | 53 (28.5%) | 46 (27.4%) | ||

Abbreviations: 25OHD, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; IQR: interquartile range

Table 2 summarizes vitamin D and HRQoL measures at diagnosis and 1 year post diagnosis in the overall sample and by vitamin D supplementation. This table only included participants who had circulating vitamin D data at both time points (N=372). For depression (yes, no), within vitamin D supplementation group differences were compared using McNemar’s test. Categorized vitamin D (deficient, insufficient, sufficient) were compared using Friedman’s test for the overall sample, and the symmetry test for within group differences. Continuous variables were compared using the sign test. All corresponding p-values were provided, as well as spearman correlations comparing baseline and 1-year measures of vitamin D and quality-of-life outcomes.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics of 372 participants in the Women’s Health After Breast Cancer Study with data at breast cancer diagnosis and 1-year post diagnosis

| Characteristic | All Participants | Vitamin D Supplement Use 1 year post-diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No, never, or occasionally | Yes, at least once per week | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| At diagnosis (N=372) | 1 year post-dx (N=372) | P-valuea | At diagnosis (N=249) | 1 year post-dx (N=186) | P-valuea | At diagnosis (N=106) | 1 year post-dx (N=168) | P-valuea | |

|

| |||||||||

| 25OHD, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 24.5 (19–30) | 26.7 (20–34) | <0.0001 | 23.6 (18–28) | 23.7 (18–30) | 0.12 | 28.4 (24–34) | 29.8 (24–38) | <0.0001 |

| r=0.71, p<0.0001 | r=0.68, p<0.0001 | r=0.73, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| Circulating 25OHD group | |||||||||

| Sufficient (>30 ng/ml) | 104 (28.0%) | 135 (36.3%) | <0.0001 | 55 (22.1%) | 46 (24.7%) | <0.0001 | 45 (42.5%) | 81 (48.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Insufficient (20 to ≤30 ng/ml) | 163 (43.8%) | 146 (39.2%) | 112 (45.0%) | 76 (40.9%) | 49 (46.2%) | 65 (38.7%) | |||

| Deficient (<20 ng/ml) | 105 (28.2%) | 91 (24.5%) | 82 (32.9%) | 64 (34.4%) | 12 (11.3%) | 22 (13.1%) | |||

| r=0.63, p<0.0001 | r=0.59, p<0.0001 | r=0.65, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| SF-36 physical health summary score | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 95 (70–100) | 90 (70–100) | 0.0003 | 95 (75–100) | 90 (70–100) | 0.04 | 90 (65–100) | 90 (70–100) | 0.001 |

| r=0.50, p<0.0001 | r=0.52, p<0.0001 | r=0.48, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| SF-36 mental health summary score | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 75 (55–85) | 80 (65–90) | <0.0001 | 70 (55–80) | 85 (65–90) | <0.0001 | 75 (60–85) | 80 (65–90) | <0.0001 |

| r=0.47, p<0.0001 | r=0.49, p<0.0001 | r=0.45, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| Fatigue score | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 13.1 (2–24) | 12.0 (1–22) | 0.21 | 12.8 (1–24) | 11.3 (1 – 21) | 0.06 | 13.8 (8–23) | 13.8 (5–25) | 0.73 |

| r=0.52, p<0.0001 | 0.53, p<0.0001 | r=0.47, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| Perceived stress score | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (7–19) | 10 (5–16) | <0.0001 | 14 (8–19) | 9 (6–15) | <0.0001 | 12 (7–18) | 11 (5–16) | 0.003 |

| r=0.60, p<0.0001 | r=0.55, p<0.0001 | r=0.65, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| Depression Score | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 9 (4–16) | 5 (2–13) | <0.0001 | 9 (4–16) | 5 (2–12) | <0.0001 | 7.5 (3–16) | 5.5 (2–15) | 0.002 |

| r=0.56, p<0.0001 | r=0.55, p<0.0001 | r=0.60, p<0.0001 | |||||||

| Depression Group, n (%) | |||||||||

| No | 266 (71.5%) | 286 (79.7%) | 0.0005 | 176 (70.7%) | 149 (82.3%) | 0.003 | 78 (73.6%) | 123 (75.9%) | 0.27 |

| Yes | 106 (28.5%) | 73 (20.3%) | 73 (29.3%) | 32 (17.7%) | 28 (26.4%) | 39 (24.1%) | |||

| r=0.42, p<0.0001 | r=0.34, p<0.0001 | r=0.52, p<0.0001 | |||||||

Abbreviations: 25OHD, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; IQR: interquartile range; sd: standard deviation.

P-values from sign test for continuous variables, McNeMar’s test for categorized depression (yes, no), and Friedman’s test for categorized vitamin D (sufficient, insufficient, deficient) for overall sample, and symmetry test for within group differences.

In the overall sample and within vitamin D supplementation groups, logistic regression modeling was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations of 25OHD levels with dichotomized HRQoL outcomes, including low SF-36 summary mental health and physical health scores (below versus above the median), high perceived stress (above vs. below median), depression (CES-D score ≥16, depressed vs. score <16, not depressed), and fatigue (above vs. below median), at the time of diagnosis and 1-year post diagnosis. 25OHD levels at diagnosis were also examined with respect to HRQOL experienced 1-year post-diagnosis. For models with poor fit (due to small sample sizes), absolute ridging and Newton-Raphson techniques were used to achieve model convergence. A standardized odds ratio was also provided for dichotomized 1-year HRQoL outcome measures as a function of baseline vitamin D level (continuous). Findings are shown in Figures 1–3, and Supplementary Tables 2 to 6. Since women taking vitamin D supplements had higher circulating vitamin D levels than non-users, findings are also presented stratified by use of vitamin D supplements. The same associations were examined by change in use of vitamin D supplements from prior to breast cancer diagnosis to 1-year post diagnosis. To test for linear trend, categorical vitamin D levels were assessed in models as a continuous ordinal variable.

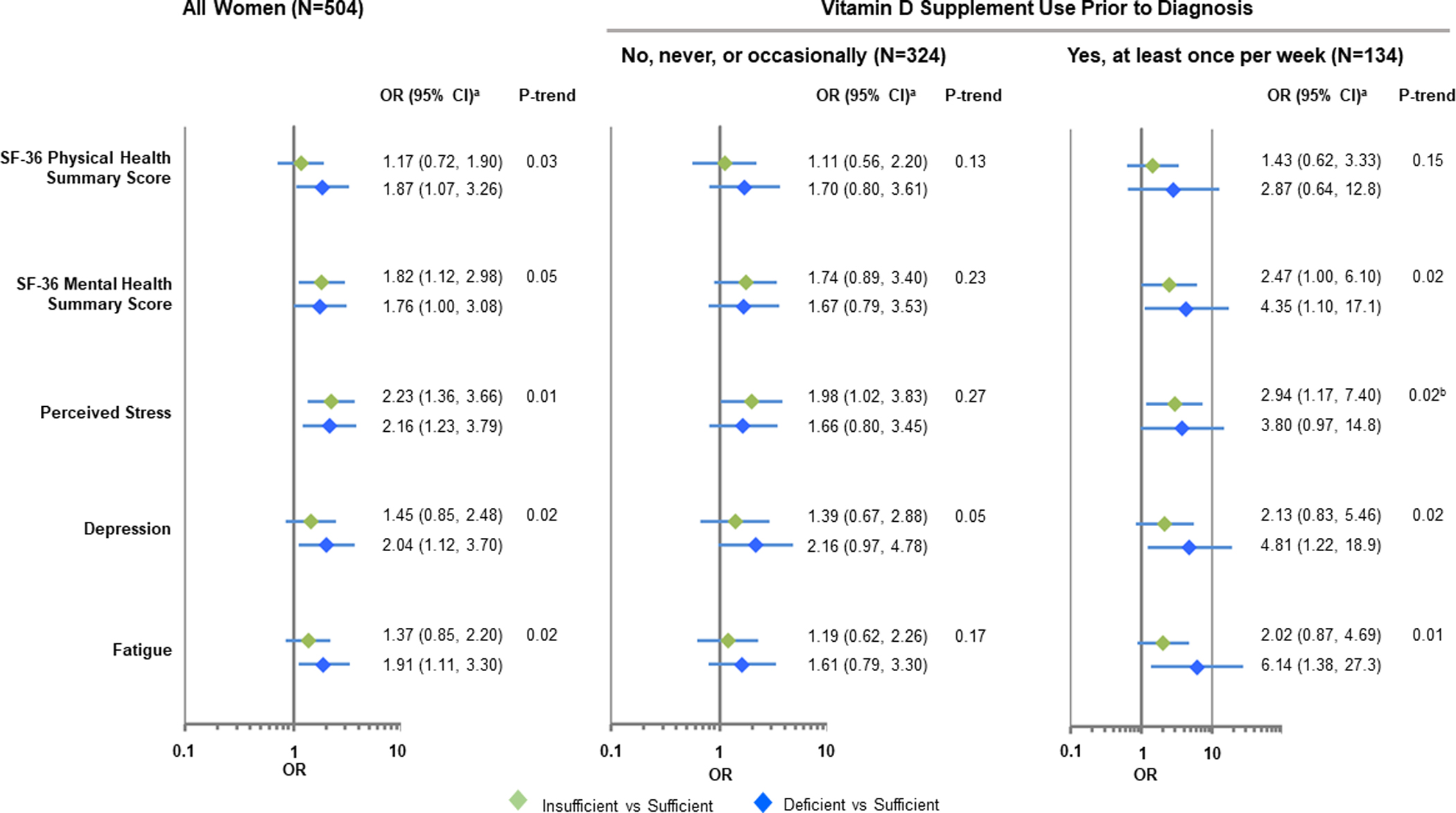

Figure 1. Associations between circulating 25OHD levels and quality-of-life at the time of breast cancer diagnosis.

Models reflect the dichotomized baseline quality-of-life outcome as a function of baseline vitamin D level in all study participants (N=504) and by vitamin D supplement use prior to diagnosis. aModels are adjusted for age (continuous), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), race (white, Black), level of education attained (high school or less, some college, college graduate, advanced degree, missing), BMI at diagnosis (continuous, log-transformed), smoking status (current, former, never, missing), breast cancer stage (0, I, IA, ≥IIB) and estrogen receptor status (positive, negative, not determined). bFor models with poor fit (due to small sample sizes), absolute ridging and Newton-Raphson techniques were used to achieve model convergence.

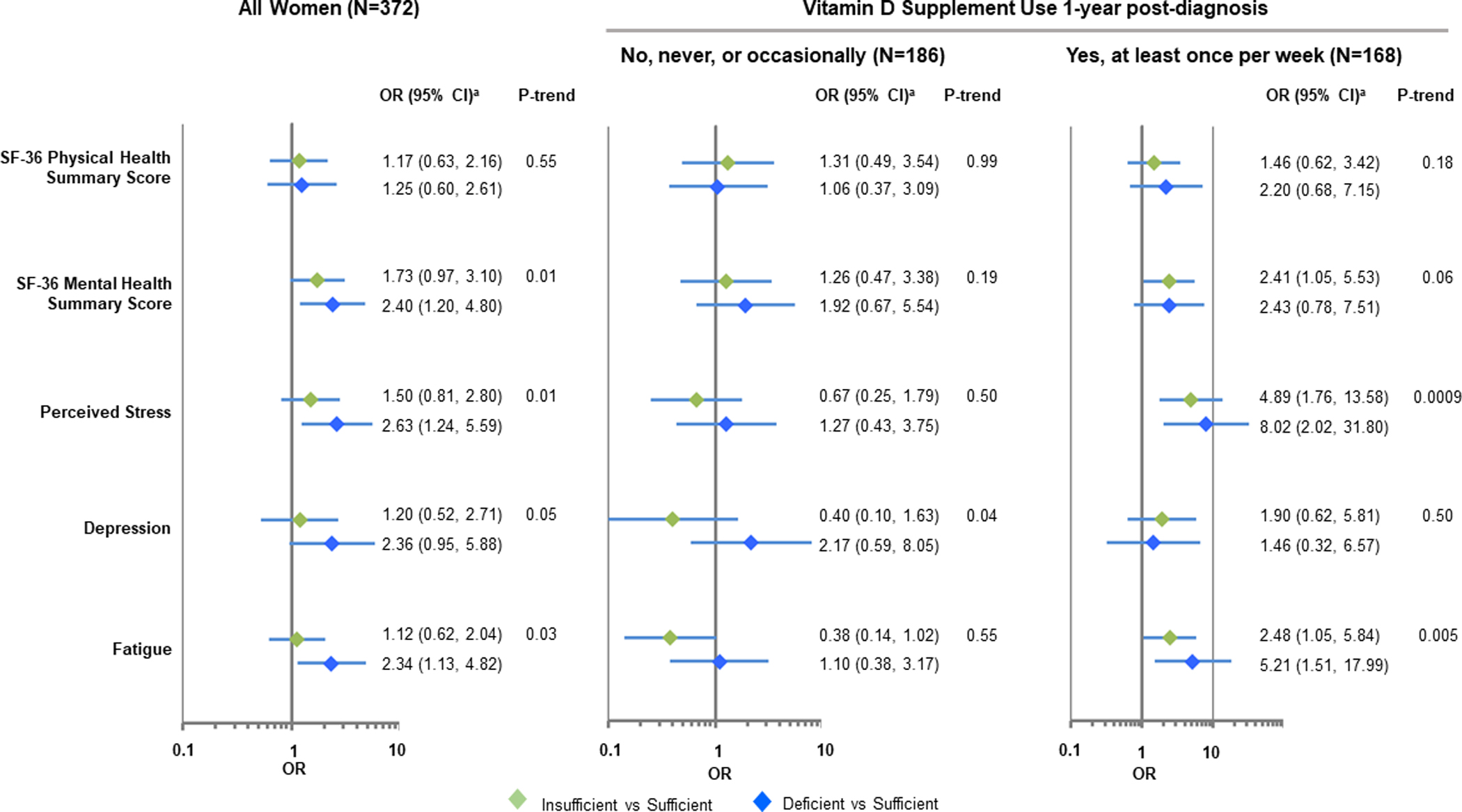

Figure 3. Associations between circulating 25OHD levels and quality-of-life 1-year post-diagnosis.

Models reflect the dichotomized 1-year quality-of-life outcome measures as a function of vitamin D levels at 1-year post diagnosis in participants with a change in vitamin D levels. aModels adjusted for age (continuous), menopausal status (pre- / post-), race (Caucasian, African American), education (High school and less, some college, college graduate (4 year), advanced degree, missing), BMI at 1 year post-diagnosis (continuous, log-transformed), smoking status (current, former, never, missing), stage (stage 0, stage I, stage IIA, > Stage IIB), ER status (positive, negative, not determined), and baseline quality-of-life measure (continuous).

All analyses were adjusted for age (continuous), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), race (White, Black), body mass index (BMI) (continuous, log-transformed), smoking status (current, former, never, missing), highest levels of education attained (grade school/some high school, high school, some college, college, advanced degree, missing), breast cancer stage (0, I, IIA, ≥IIB) and estrogen receptor (ER) status (positive, negative, not determined). BMI at diagnosis and 1-year post-diagnosis were included as a model covariates in analyses focused on 25OHD levels at diagnosis and 1 year post, respectively. Analyses examining associations between 25OHD concentrations and HRQoL 1-year post diagnosis made additional adjustments for HRQoL scores at the time of breast cancer diagnosis (continuous), and only included participants who had circulating vitamin D data at both diagnosis and one year later. The frequency of quality-of-life responses by vitamin D groups are reported, and p-values representing within and between group trends are provided. Supplementary Table 7 summarizes associations between the change in circulating 25OHD concentrations (sufficient to sufficient, sufficient to insufficient/deficient, insufficient to insufficient, deficient to deficient, insufficient/deficient to sufficient) and HRQoL 1 year post diagnosis. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) with a two-sided p-value ≤0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

Data generated in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author and are subject to data use agreements.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study population at diagnosis

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population at breast cancer diagnosis by vitamin D supplementation. The median age at diagnosis was 56 years, with 27% of women below age 50. A majority of participants were White (93%), had some college education (77%) and were diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Only 8% of women were current smokers and 42% were obese. Approximately 30% reported being depressed. At the time of breast cancer diagnosis, approximately 32% had deficient and 43% had insufficient 25OHD concentrations. Participants who reported take vitamin D supplements at least once per week for 1 year sometime in the past 10 years prior to breast cancer diagnosis were generally older at diagnosis (with a higher relative frequency of postmenopausal women), had a higher frequency of stage 0 and 1 cancers, had a lower SF-36 physical health summary score, and higher concentrations of circulating 25OHD than women who did not take vitamin D supplements. These differences were statistically significant. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, participants who took up use of vitamin D supplements after breast cancer diagnosis (no/yes group) had lower rates of obesity and were more likely to receive chemotherapy than participants who did not take vitamin D supplements before or after diagnosis (no/no) or participants who took supplements before and after diagnosis (yes/yes). HRQoL scores were not different between these 3 groups.

Changes from the time of diagnosis to 1 year post diagnosis

Table 2 summarizes the vitamin D and quality-of-life measures at diagnosis and 1-year post diagnosis in the overall sample and by vitamin D supplementation 1 year post-diagnosis. Among all women combined, the average 25OHD concentrations 1 year post-diagnosis was significantly higher than at diagnosis (season-adjusted, 26.7 ng/ml vs. 24.5 ng/ml) for participants with data at both timepoints. As a result, more participants were vitamin D sufficient (36% vs. 28%) at 1-year post diagnosis than at diagnosis. There was a moderate to strong correlation of 25OHD levels in the same participants between the two timepoints (Spearman r=0.71), and HRQoL measures were also moderately correlated (r = 0.47 to r=0.60). In the overall sample, the median SF-36 physical health summary score declined (95 to 90, p=0.0003), whereas the mental health summary score increased (75 to 80, p<0.0001), and the level of perceived stress declined (13 to 10, p<0.0001). The relative frequency of depression also declined (28.5% vs. 20.3%). These relationships were similar among both non-vitamin D supplement users as well as non-users.

Circulating 25OHD levels and HRQoL at breast cancer diagnosis

Associations of 25OHD levels and dichotomized HRQoL measures at the time of breast cancer diagnosis are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2. The ORs and 95% confidence intervals represent the odds of lower QoL scores among women with vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency compared to those with sufficient vitamin D levels. In comparison to women with sufficient vitamin D levels, those with deficient vitamin D were more likely to have lower SF-36 physical health summary scores (adjusted OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.07–3.26) and lower SF-36 mental health (adjusted OR=1.76, 95% CI: 1.00–3.08), higher levels of perceived stress (adjusted OR=2.16, 95% CI: 1.23–3.79), depression (adjusted OR=2.04, 95% CI: 1.12–3.70), and higher levels of fatigue (adjusted OR=1.91, 95% CI: 1.11–3.30). Associations were slightly stronger among those reporting use of vitamin D supplements prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Protective associations between circulating 25OHD levels and HRQoL were also observed when 25OHD concentrations were analyzed as a continuous variable(Supplementary Table 2).

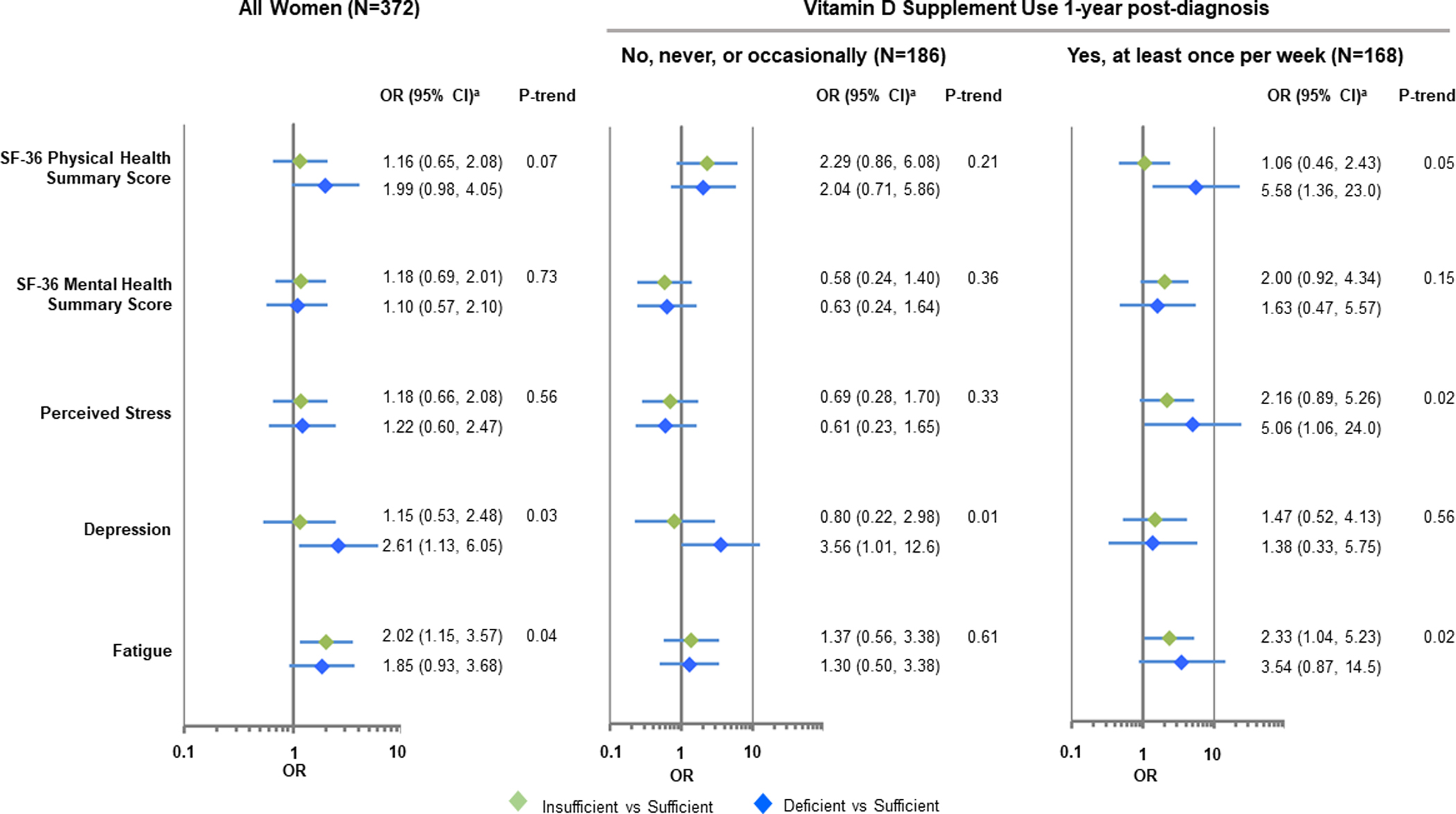

Circulating 25OHD levels at diagnosis and HRQoL 1-year post-diagnosis

As shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3, 25OHD levels at diagnosis were also associated with 3 of the HRQoL measures 1-year post diagnosis. After controlling for covariates, including HRQoL scores at the time of diagnosis, women with deficient vitamin D levels compared to those with sufficient levels were at greater risk of having lower SF-36 mental health summary scores (adjusted OR=2.40, 95% CI: 1.20–4.80), higher levels of perceived stress (adjusted OR=2.63, 95% CI: 1.24–5.59), and fatigue (adjusted OR=2.34, 95% CI: 1.13–4.82). A borderline significant association with depression was also observed (adjusted OR=2.36, 95% CI: 0.95–5.88). None of the associations remained significant when analysis was restricted to women who did not use vitamin D supplements 1 year post-diagnosis, but associations with increased perceived stress and fatigue remained significant among those who reported taking vitamin D supplements. These findings, however, were based on a limited sample size. Similarly, based on small numbers, women with insufficient and deficient vitamin D levels were more likely to report increased levels of perceived stress if they started taking vitamin D supplements after breast cancer diagnosis or took supplements before and after diagnosis (Supplementary Table 4). Findings were similar when 25OHD concentrations were analyzed as a continuous variable. (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 2. Associations between circulating 25OHD levels at diagnosis and quality-of-life 1-year post-diagnosis.

Models reflect the dichotomized 1-year quality-of-life outcome measures as a function of baseline vitamin D level in participants with data on change in vitamin D levels. aModels adjusted for age (continuous), menopausal status (pre- / post-), race (Caucasian, African American), education (High school and less, some college, college graduate (4 year), advanced degree, missing), BMI at 12 months post-diagnosis (continuous, log-transformed), smoking status (current, former, never, missing), breast cancer stage (stage 0, stage I, stage IIA, ≥ Stage IIB), ER status (positive, negative, not determined), and baseline quality-of-life measure (continuous).

Circulating 25OHD levels and HRQoL 1-year post-diagnosis

As shown in Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5, women with deficient vitamin D levels one year after diagnosis were at increased risk of reporting depression (adjusted OR=2.61, 95% CI: 1.13–6.05). Associations with depression remained significant when analysis was restricted to women who did not report vitamin D supplement use and were significant for associations with lower SF-36 physical health summary scores and higher perceived stress among vitamin D supplement users. Relationships with higher perceived stress was more pronounced among those who started taking vitamin D supplements after breast cancer diagnosis or took supplements before and after diagnosis, but these findings were based on small sample sizes and were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 6). Women who had sufficient levels of circulating 25OHD at diagnosis and 1 year post diagnosis were the least likely to report higher levels of perceived stress and fatigue 1 year post-diagnosis (Supplementary Table 7).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of women with early-stage breast cancer, we found evidence for associations of deficient 25OHD levels and poorer HRQoL measures, including the SF-36 physical and mental health summary scores, perceived stress, depression, and fatigue. The associations were consistent when 25OHD and HRQoL were both assessed at the time of diagnosis and 1-year later. 25OHD levels at the time of diagnosis were also associated with HRQoL 1-year post diagnosis, except for the SF-36 physical health summary score. When analyses were stratified by vitamin D supplement use, associations with increased perceived stress, depression, and fatigue were stronger among women who used vitamin D supplements. Our study joins the few others in the literature in supporting the potential benefits of maintaining sufficient vitamin D levels for higher HRQoL in cancer survivors(11,15,29–31).

Previous studies have suggested multiple biological mechanisms responsible for vitamin D’s benefits on physical and mental functions. Vitamin D is well-established for its roles in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis through facilitating intestinal calcium absorption and bone mineralization, and vitamin D deficiency is causally linked to rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults (32). In an earlier phase II trial of breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors (AIs), weekly high doses of 50,000 IU vitamin D2 significantly improved AI-induced musculoskeletal symptoms, including fibromyalgia and pain (33). Vitamin D also has extensive involvement in the immune system by modulating the innate and adaptive immune responses. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with chronic inflammation, increased autoimmunity, and increased susceptibility to infection (34,35). The psychological functions of vitamin D are not well understood. Both the vitamin D activating enzyme and vitamin D receptor are present in the brain. Vitamin D modulates brain function and can contribute to neuroprotection and neurotransmission (36,37). Therefore, it is biologically plausible that vitamin D may improve the physical and mental health aspects of HRQoL.

Like any other observational studies of circulating vitamin D levels, however, cautions of reverse causality must be taken when interpreting our findings. Because vitamin D in human bodies mainly comes from vitamin D synthesis in the epidermal layer of skin when exposed to ultraviolet radiation, women diagnosed and undergoing treatment for breast cancer may avoid going outdoors if they feel physically or mentally unwell. Shorter exposure to sunlight might lead to deficient vitamin D levels without the use of supplements, which could explain the observed associations of vitamin D deficiency and poorer HRQoL measures in breast cancer patients in our study. To refute this alternative explanation, it would be necessary to examine data from interventional studies of vitamin D supplementation.

Although to date no large clinical trials have been conducted to test vitamin D supplement use and psychological wellbeing, many small interventional studies have been published. As summarized in several recent meta-analyses, vitamin D supplementation was shown to be efficacious for lowering depression symptom scores and negative emotions in the general population (38–40); however, another systematic review of randomized clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation concluded with no strong evidence for a positive effect on mental health in healthy adults (41). A few interventional studies of vitamin D supplementation have also been reported in cancer patients. In a small study of 60 women, 50,000 IU/week vitamin D3 was administered to breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy with aromatase inhibitors (AIs)(15). Those who reached 25OHD levels >66 ng/ml (median level) reported less joint pain and fatigue than those with levels <66 ng/ml. In another study of 227 breast cancer survivors who participated in a 12-month lifestyle modification program with Mediterranean diet, exercise, and vitamin D supplementation, an increase in serum 25OHD levels were associated with fewer breast cancer-related symptoms (31). Lastly, in a double-blinded, placebo-controlled randomized multicenter trial of 244 advanced cancer patients in palliative care, the group receiving 4,000 IU/day vitamin D3 for 12 weeks had a significantly smaller increase in opioid use and lower fatigue scores than the placebo group (42). Although these studies provide some evidence for potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation to improve HRQoL in cancer survivors, larger and more definitive randomized trials are still warranted.

Our study is among the largest prospective investigation of circulating 25OHD levels with HRQoL in breast cancer patients. However, a few limitations should be noted. First, we did not collect data on the length of sun exposure patients had at the time of diagnosis and during follow up, or their habits of clothing and sunscreen use, which would be helpful to examine the relationships between sun exposure and physical and mental well-being. Second, we repeated the measurements of vitamin D and HRQoL one year after diagnosis, and it will be interesting to extend the follow-up to later years to assess long-term effects. Third, >90% of the women were White and only 6% were Black. As individuals with darker skin are more likely to have lower vitamin D levels (43,44), it would be important to study the impact of a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency on HRQoL in Black breast cancer patients. Fourth, we were not able to distinguish between vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplements, which may be important given that D3 supplements may be more effective at raising vitamin D levels than D2 (45).

In conclusion, our longitudinal analysis revealed a consistent relationship of vitamin D deficiency and poor HRQoL in breast cancer patients at the time of diagnosis and 1-year post. The findings support future studies on the potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation to improve HRQoL for a rapidly growing population of breast cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support and Acknowledgements

The Women’s Health after Breast Cancer (ABC) Study was supported by Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (BCTR104906 to C-C Hong), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to C.B. Ambrosone and C-C Hong), the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (DoD W81XWH0610401 to C-C Hong), the Health Research Science Board New York State Department of Health (C020918 to C-C Hong), and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center Alliance Foundation (to C.B. Ambrosone and C-C Hong). This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA016056 (to C.S. Johnson) involving the use of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center’s DataBank and Biorepository Shared Resource.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouillon R, Marcocci C, Carmeliet G, Bikle D, White JH, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr Rev 2019;40(4):1109–51 doi 10.1210/er.2018-00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders 2017;18(2):153–65 doi 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crew KD, Shane E, Cremers S, McMahon DJ, Irani D, Hershman DL. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency despite supplementation in premenopausal women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(13):2151–6 doi 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao S, Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, Roh JM, Cheng TD, Hong CC, et al. Association of Serum Level of Vitamin D at Diagnosis With Breast Cancer Survival: A Case-Cohort Analysis in the Pathways Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3(3):351–7 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu K, Callen DF, Li J, Zheng H. Circulating Vitamin D and Overall Survival in Breast Cancer Patients: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Integrative cancer therapies 2018;17(2):217–25 doi 10.1177/1534735417712007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Fang F, Tang J, Jia L, Feng Y, Xu P, et al. Association between vitamin D supplementation and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2019;366:l4673 doi 10.1136/bmj.l4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, Christen W, Bassuk SS, Mora S, et al. Vitamin D Supplements and Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med 2019;380(1):33–44 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urashima M, Ohdaira H, Akutsu T, Okada S, Yoshida M, Kitajima M, et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Relapse-Free Survival Among Patients With Digestive Tract Cancers: The AMATERASU Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321(14):1361–9 doi 10.1001/jama.2019.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamer J, McDonald R, Zhang L, Verma S, Leahey A, Ecclestone C, et al. Quality of life (QOL) and symptom burden (SB) in patients with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2017;25(2):409–19 doi 10.1007/s00520-016-3417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Götze H, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A. Fear of cancer recurrence across the survivorship trajectory: Results from a survey of adult long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2019;28(10):2033–41 doi 10.1002/pon.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koole JL, Bours MJL, van Roekel EH, Breedveld-Peters JJL, van Duijnhoven FJB, van den Ouweland J, et al. Higher Serum Vitamin D Concentrations Are Longitudinally Associated with Better Global Quality of Life and Less Fatigue in Colorectal Cancer Survivors up to 2 Years after Treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2020;29(6):1135–44 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen MR, Sweet E, Hager S, Gaul M, Dowd F, Standish LJ. Effects of Vitamin D Use on Health-Related Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients in Early Survivorship. Integrative cancer therapies 2019;18:1534735418822056 doi 10.1177/1534735418822056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Alonso M, Dusso A, Ariza G, Nabal M. Vitamin D deficiency and its association with fatigue and quality of life in advanced cancer patients under palliative care: A cross-sectional study. Palliative medicine 2016;30(1):89–96 doi 10.1177/0269216315601954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick RP, Ames BN. Vitamin D hormone regulates serotonin synthesis. Part 1: relevance for autism. FASEB J 2014;28(6):2398–413 doi 10.1096/fj.13-246546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan QJ, Reddy PS, Kimler BF, Sharma P, Baxa SE, O’Dea AP, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels, joint pain, and fatigue in women starting adjuvant letrozole treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;119(1):111–8 doi 10.1007/s10549-009-0495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrosone CB, Nesline MK, Davis W. Establishing a cancer center data bank and biorepository for multidisciplinary research. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2006;15(9):1575–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng TD, Shelver WL, Hong CC, McCann SE, Davis W, Zhang Y, et al. Urinary Excretion of the β-Adrenergic Feed Additives Ractopamine and Zilpaterol in Breast and Lung Cancer Patients. J Agric Food Chem 2016;64(40):7632–9 doi 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b02723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior 1983;24(0022–1465; 4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff RS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Volume 11977. p 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, Chartash E, Sengupta N, Grober J. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology 2005;32(0315–162; 5):811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehead L. The measurement of fatigue in chronic illness: a systematic review of unidimensional and multidimensional fatigue measures. Journal of pain and symptom management 2009;37(1):107–28 doi 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology and aging 1997;12(2):277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belza BL, Henke CJ, Yelin EH, Epstein WV, Gilliss CL. Correlates of fatigue in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Nurs Res 1993;42(2):93–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, Weiss MC, Slaughter RE, Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncology nursing forum 1998;25(4):677–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meek PM, Nail LM, Barsevick A, Schwartz AL, Stephen S, Whitmer K, et al. Psychometric testing of fatigue instruments for use with cancer patients. Nursing research 2000;49(4):181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao S, Sucheston LE, Millen AE, Johnson CS, Trump DL, Nesline MK, et al. Pretreatment serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and breast cancer prognostic characteristics: a case-control and a case-series study. PloS one 2011;6(2):e17251 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0017251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn J, Peters U, Albanes D, Purdue MP, Abnet CC, Chatterjee N, et al. Serum vitamin D concentration and prostate cancer risk: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(11):796–804 doi 10.1093/jnci/djn152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Custódio IDD, Nunes FSM, Lima MTM, de Carvalho KP, Alves DS, Chiaretto JF, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cancer-related fatigue: associations and effects on depression, anxiety, functional capacity and health-related quality of Life in breast cancer survivors during adjuvant endocrine therapy. BMC Cancer 2022;22(1):860 doi 10.1186/s12885-022-09962-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maureen Sheean P, Robinson P, Bartolotta MB, Joyce C, Adams W, Penckofer S. Associations Between Cholecalciferol Supplementation and Self-Reported Symptoms Among Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Pilot Study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2021;48(3):352–60 doi 10.1188/21.Onf.352-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montagnese C, Porciello G, Vitale S, Palumbo E, Crispo A, Grimaldi M, et al. Quality of Life in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer after a 12-Month Treatment of Lifestyle Modifications. Nutrients 2020;13(1) doi 10.3390/nu13010136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laird E, Ward M, McSorley E, Strain JJ, Wallace J. Vitamin D and bone health: potential mechanisms. Nutrients 2010;2(7):693–724 doi 10.3390/nu2070693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rastelli AL, Taylor ME, Gao F, Armamento-Villareal R, Jamalabadi-Majidi S, Napoli N, et al. Vitamin D and aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms (AIMSS): a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;129(1):107–16 doi 10.1007/s10549-011-1644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med 2011;59(6):881–6 doi 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin K, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D and inflammatory diseases. J Inflamm Res 2014;7:69–87 doi 10.2147/JIR.S63898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang S, Miller DD, Li W. Non-Musculoskeletal Benefits of Vitamin D beyond the Musculoskeletal System. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22(4) doi 10.3390/ijms22042128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui X, Gooch H, Petty A, McGrath JJ, Eyles D. Vitamin D and the brain: Genomic and non-genomic actions. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017;453:131–43 doi 10.1016/j.mce.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng YC, Huang YC, Huang WL. The effect of vitamin D supplement on negative emotions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 2020;37(6):549–64 doi 10.1002/da.23025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spedding S. Vitamin D and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients 2014;6(4):1501–18 doi 10.3390/nu6041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vellekkatt F, Menon V. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Postgrad Med 2019;65(2):74–80 doi 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_571_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guzek D, Kolota A, Lachowicz K, Skolmowska D, Stachon M, Glabska D. Association between Vitamin D Supplementation and Mental Health in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical medicine 2021;10(21) doi 10.3390/jcm10215156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helde Frankling M, Klasson C, Sandberg C, Nordstrom M, Warnqvist A, Bergqvist J, et al. ‘Palliative-D’-Vitamin D Supplementation to Palliative Cancer Patients: A Double Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Trial. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(15) doi 10.3390/cancers13153707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao S, Ambrosone CB. Associations between vitamin D deficiency and risk of aggressive breast cancer in African-American women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013;136:337–41 doi 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao S, Hong CC, Bandera EV, Zhu Q, Liu S, Cheng TD, et al. Demographic, lifestyle, and genetic determinants of circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and vitamin D-binding protein in African American and European American women. Am J Clin Nutr 2017. doi 10.3945/ajcn.116.143248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shieh A, Chun RF, Ma C, Witzel S, Meyer B, Rafison B, et al. Effects of High-Dose Vitamin D2 Versus D3 on Total and Free 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Markers of Calcium Balance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101(8):3070–8 doi 10.1210/jc.2016-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author and are subject to data use agreements.