Abstract

Catalytic carbonylations of aryl electrophiles via C(sp2)–N cleavage remains a significant challenge. Herein, we demonstrate an aminocarbonylation of aniline-derived trialkylammonium salts promoted by visible light with a simple cobalt catalyst. The reaction proceeds under mild conditions suitable for late-stage functionalization and is amenable to telescoped carbonylations directly from anilines. A range of alkylamines are successful partners, and alkoxycarbonylation is also demonstrated. Mechanistic studies and DFT calculations support a novel mechanism for catalytic carbonylations of aryl electrophiles involving a key visible light-induced carbonyl photodissociation.

Keywords: amines, carbonylation, cobalt, synthetic methods, visible light

Graphical Abstract

We demonstrate a cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of aniline-derived trialkylammonium salts promoted by visible light via a challenging C(sp2)–N cleavage. The reaction is suitable for late-stage functionalization and is amenable to telescoped carbonylations directly from anilines. Mechanistic studies and DFT calculations support a novel mechanism involving a key visible light-induced carbonyl photodissociation and SNAr-type oxidative addition.

Introduction

Anilines are attractive building blocks in chemical synthesis, prevalent in diverse biologically active molecules and organic materials.[1] Furthermore, this chemotype enables fundamental transformations of (hetero)arenes such as electrophilic aromatic substitutions and other derivatizations. Aniline-derived electrophilic salts (e.g., diazonium or Katritzky-type salts) facilitate diverse reactions via C(sp2)–N activation, with aryl trialkylammonium salts a particularly attractive member of this class owing to their stability and ease of synthesis.[2] Catalytic cross-couplings of aryl trialkylammonium salts have been known for decades, with a wide range of synthetically attractive variants developed,[3] including the formation of carbon–carbon[3b–f] and carbon–heteroatom[3g–i] bonds, reductive reactions,[3j–k] and C–H functionalizations.[3l–m] Aryl trialkylammonium salts have also recently been used to access benzamides via nickel catalyzed electrochemical cross-coupling.[4] In contrast, despite the high value of C(sp2)–X carbonylation of (hetero)aryl electrophiles in synthesis, carbonylations of aryl trialkylammonium salts via C(sp2)–N activation remain unknown (Figure 1). While carbonylations of diazonium salts have been reported,[5] these highly reactive electrophiles are not generally suitable in aminocarbonylation catalysis, owing to their high reactivity with common nucleophiles such as amines.[6] A likely challenge in the carbonylations of aryl trialkylammonium salts with palladium catalysts is the electron-withdrawing effects of carbonyl ligands on the metal center.[7]

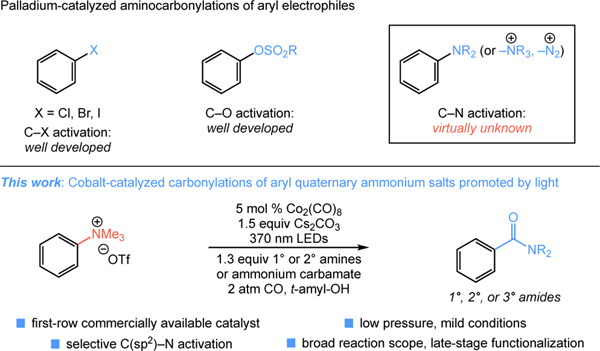

Figure 1.

Aminocarbonylations of aryl electrophiles.

Light is known to promote the metal-catalyzed carbonylations of diverse electrophiles,[8] as in the classic studies of Caubere on the carbonylations of benzyl and allyl trialkylammonium halides using sunlamp irradiation.[9] These studies used Co2(CO)8 as catalyst under phase transfer conditions for the carbonylations of quaternary ammonium salts involving C(sp3)–N cleavage. Recently, anionic cobalt and iron carbonyl complexes were shown to catalyze the carbonylations of anilines and aryl trialkylammonium salts to tertiary amides. However, sole site-selective dealkylation via cleavage of the alkyl C(sp3)–N bond occurred.[10]

We have previously demonstrated the utility of simple anionic cobalt carbonyls in the catalytic carbonylation of both alkyl and aryl (pseudo)halide electrophiles using low pressure CO gas and LED lights.[11] We hypothesized that this light-promoted catalytic system could enable a carbonylation of aryl trialkylammonium salts that reverses the site-selectivity of previous studies to favor C(sp2)–N activation. Herein, we report the successful development of such a process, enabling the aminocarbonylation and alkoxycarbonylation of diverse aniline-derived trialkylammonium salts (Figure 1). This visible light-promoted reaction proceeds under exceedingly mild conditions and low pressure using a commercially available cobalt catalyst, significantly increasing the synthetic utility of this attractive class of aryl electrophiles in metal-catalyzed transformations.

Results and Discussion

We began our studies with the aminocarbonylation of N,N,N,4-tetramethylanilinium triflate (1) using piperidine as the nucleophile. A reaction system comprised of 5 mol % Co2(CO)8 as catalyst with 1.5 equiv of Cs2CO3 in tert-amyl alcohol under 2 atm of CO gas and 370 nm LED irradiation delivered the desired amide in 78% isolated yield (Table 1, entry 1). The remaining mass balance of the reaction was most often recovered starting material. The only minor byproducts involved dealkylation via C(sp3)–N cleavage, as observed in prior carbonylations of alkyl ammonium salts. Reactions with aryl trialkylammonium salts containing several different counterions were also examined with no improvement over the triflate salt and given the facile quaternization of anilines with methyl triflate, these salts were used throughout our work (Table S3). Use of an equivalent amount of a cobaltate salt catalyst was similarly efficient (entry 2), while other metal carbonyl complexes (entry 3) and simple cobalt salts (entry 4) were ineffective. Irradiation with blue LEDs (427 nm, entry 5), or reaction in the absence of LEDs (entries 6–7) all led to diminished yields and substantial amounts of undesired dealkylation byproducts. The use of 1.1 atm instead of 2 atm CO in a sealed tube gave a slight decrease in the reaction yield (entry 8). The aminocarbonylation was inefficient at shorter reaction times (entry 9) and in the absence of base (entry 10). No product was observed in the absence of catalyst (entry 11). As a means of comparison, several reactions using 1 and previously reported palladium-based aminocarbonylation catalysts were performed, with no desired product observed.[12]

Table 1.

Cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of N,N,N,4-tetramethylanilinium triflate with piperidine.[a]

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from standard conditions above | yield (%)[b] |

| 1 | none | 78[c] |

| 2 | 10 mol % K[Co(CO)4] instead of Co2(CO)8 | 76 |

| 3 | 10 mol % Mn2(CO)10 instead of Co2(CO)8 | 8 |

| 4 | 10 mol % CoCI2 instead of Co2(CO)8 | <2 |

| 5 | 427 nm LEDs instead of 370 nm LEDs | 12 |

| 6 | ambient light, 50 °C instead of 370 nm LEDs | <2 |

| 7 | no light instead of 370 nm LEDs | <2 |

| 8 | 1.1 atm CO (sealed tube) instead of 2 atm CO | 68 |

| 9 | 20 h Instead of 44 h | 25 |

| 10 | no Cs2CO3 | 14 |

| 11 | no Co2(CO)8 | <2 |

Reactions were performed with [1]0 = 0.20 M.

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude reaction mixture using an internal standard.

Isolated yield.

We next applied our catalytic system to a diverse set of aryl trialkylammonium salts (Figure 2). Aminocarbonylations of electronically varied substrates proceeded in good to excellent yields (1–11). This reaction can also be performed on gram scale, as demonstrated with trialkylammonium salt 1 (70% isolated yield). Salts with para-electron withdrawing groups were also viable, but we did observe that reactions with these substrates were somewhat less efficient (12–13). The reaction of a naphthyl trimethylammonium salt (14) also proceeded in good yield. The aminocarbonylation is also not limited to the use of trimethylammonium salts, as trialkylammonium salts with both longer and cyclic chains were similarly efficient (15–17). Substrates containing densely functionalized arenes with multiple electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents performed well (18–19). The successful reactions of the trimethylammonium salts derived from drug compounds aminoglutethimide (20) and cholinesterase inhibitor neostigmine (21) highlight the applicability of the aminocarbonylation to late-stage functionalization. Finally, we note that a telescoped, one-pot aminocarbonylation is also easily achieved starting from primary or tertiary anilines with a minimal decrease in overall yield (eq 1–2). The ability to use aryl amines as starting materials for the aminocarbonylation–via in situ formation of alkylammonium salts–enhances the utility of the method for arene functionalization.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Figure 2.

Cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of aryl trialkylammonium salts with piperidine as the nucleophile. [a] Telescoped reaction from primary aniline. [b] 3 equiv CsF used as base. [c] 10 mol % Co2(CO)8 used as catalyst. [d] Telescoped reaction from secondary aniline. [e] Telescoped reaction from tertiary aniline.

Our studies continued with a survey of the amine nucleophiles suitable for the aminocarbonylation (Figure 3). Secondary cyclic and acyclic amines all reacted efficiently to produce the desired amides in high yield (22–26). Several primary amines also reacted efficiently (27–32) and demonstrated functional group compatibility with free alcohols (30), alkyl chlorides (31), and unprotected heterocycles (32). Amino acid esters were also viable coupling partners (33–34). In addition, primary amides are also easily obtained using ammonium carbamate as an ammonia surrogate—a major challenge for many aminocarbonylation methods (35).[13]

Figure 3.

Cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of 4 using diverse amine nucleophiles. [a] 10 mol % Co2(CO)8 as catalyst with 8.0 equiv of CsF as base and 5.0 equiv of amine nucleophile. [b] Ammonium carbamate used as an ammonia surrogate.

We were also interested in pursuing an alkoxycarbonylation of aryl trialkylammonium salts using this carbonylation platform to further enhance the capabilities of our approach. Alkoxycarbonylations of aryl electrophiles are fundamental transformations of carbonylation catalysis, yet versions involving C(sp2)–N activation are limited to hazardous diazonium salts.[5] Using slightly modified conditions with excess alcohol and cesium fluoride as base, we obtained good yields of a variety of benzoic esters (Figure 4). Interestingly, electron poor alcohols (i.e., trifluoroethanol) are not required in excess likely owing to a decreased pKa (36). Several common primary and secondary aliphatic alcohols reacted efficiently (37–40). Phenol was also an excellent coupling partner, delivering 41 in high yield (83% isolated yield). Aryl trialkylammonium salts with varying electronics and substitution were also viable in the alkoxycarbonylation, providing benzoic esters in moderate to high yields (42–44).

Figure 4.

Cobalt-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of 4 using alcohol nucleophiles. [a] 1.3 equiv of trifluoroethanol used as nucleophile. [b] Yield determined by GC with internal standard.

Anilines are fundamental building blocks, often used as electron-rich substrates in a range of valuable electrophilic aromatic substitution processes. The capability of directly transforming anilines to benzamides offers attractive opportunities in the elaboration of the synthetically enabling, electron-donating amino group while also converting the aromatic ring from electron-rich to electron-deficient in a single step. For example, an organocatalyzed enantioselective conjugate addition of aniline 8a delivered alkylation product 45 in high yield.[14] Following reduction and esterification, the telescoped quaternization-catalytic aminocarbonylation of substrate 46 provided 47 in good yield with no erosion of the alkylation enantioselectivity (Scheme 1, 94% ee).

Scheme 1.

Telescoped catalytic aminocarbonylation of an aniline used for organocatalyzed enantioselective alkylation.

We next sought to shed light on the detailed mechanism of the aminocarbonylation, and specifically whether the reaction pathway aligns with previous mechanistic proposals.[9,11a,15] There are two primary pathways which have been formulated for photochemical C(sp2)–X carbonylations using cobaltate catalysis: 1) activation via a photochemical charge transfer of a donor-acceptor complex or 2) radical chain SRN1 pathways involving [Co(CO)4]− as the nucleophile. A depiction of a possible charge transfer mechanism is shown in Scheme 2.[16] An alternative pathway we have recently considered was whether photoinduced CO ligand dissociation from the cobalt catalyst was involved under our aminocarbonylation conditions. Photoinduced CO dissociation is well precedented in carbonylation catalysis yet is not involved in either of these possible pathways.[17]

Scheme 2.

Aminocarbonylation mechanism involving photochemical charge transfer of a donor-acceptor complex.

To differentiate between possible pathways, we obtained a quantum yield of the reaction (eq 3), which was 4.5 and not consistent with the donor-acceptor charge transfer mechanism in Scheme 2.[17c–e] Interestingly, there was an inverse relationship between reaction CO pressure and quantum yield, which decreased to 2.2 at 10 atm CO. This dependence supports a key photodissociation of a CO ligand from the cobalt center in the catalytic cycle and is not consistent with either of the two mechanisms previously proposed.[11a,15] Reaction of radical probe substrate 48 containing pendant alkene functionality yielded only the uncyclized carbonylation product (eq 4). No radical trapped adducts were observed when aminocarbonylations were performed in the presence of free radical inhibitors TEMPO or galvinoxyl; however, these reactions likely involved catalyst decomposition. We also note that no aminocarbonylation regioisomers were observed in any reactions, consistent with a non-radical pathway.[18]

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

With new evidence supporting photodissociation of CO as a key step in the reaction mechanism, we attempted to model this alternative reaction pathway through computational methods. Using density functional theory (DFT) with the M06–2X functional and 6–311+G(d) basis set, we located the intermediates and transition states outlined in Figure 5. The pathway commences with photodissociation of CO to generate an open coordination site on the cobalt tricarbonyl anion [Co(CO)3]−, followed by facile η2 arene ligation (IM1). Oxidative addition of the cobaltate to the aryl trimethylammonium salt proceeds through a concerted SNAr pathway to generate an aryl cobalt intermediate IM2 in a kinetically accessible (ΔG‡ = 6.0 kcal mol−1) and highly exergonic step (ΔG = −37.3 kcal mol−1). While such an addition has not been previously proposed for anionic cobalt carbonyls, concerted SNAr-type oxidative additions are common to many transition metal-catalyzed processes.[19] Furthermore, we calculated the oxidative addition step with an aryl halide electrophile (bromobenzene) which displayed similar energetics (TS1’, ΔG‡ = 5.8 kcal mol−1 and IM2’, ΔG = −47.9 kcal mol−1), supporting a similar revised mechanism for previously reported catalytic photochemical carbonylations of aryl halides with anionic cobalt carbonyls.[11a,15]

Figure 5.

DFT-computed free energy profile of the aminocarbonylation with M06–2X/6–311+G(d)/CPCM(2-methyl-2-butanol) level of theory using ammonium salt 8 as the substrate. Energies are relative to the η2 cobalt-arene coordination complex IM1. Analogous activation pathway involving bromobenzene instead of 8 is shown in blue. Optimized structures of selected intermediates and transition states are also shown. See Supplementary Information for a complete free energy profile and alternative pathways. HNR2 = piperidine

Following C(sp2)–N activation, migratory insertion of a CO ligand occurs with a low barrier (ΔG‡ = 3.6 kcal mol−1) to generate acyl cobalt intermediate IM3. Ligand association of CO then forms 18-electron complex IM4 in another facile step (ΔG = 2.5 kcal mol−1). Amine ligand exchange with the nucleophile then generates IM5 (ΔG‡ = 5.2 kcal mol−1) through a concerted interchange mechanism,[20] which is primed for reductive elimination to yield the aminocarbonylation product and regenerate the anionic cobalt tricarbonyl catalyst (IM6, ΔG = −5.8 kcal mol−1). Overall, the catalytic transformation is exergonic by 48.3 kcal mol−1, with the turnover-limiting step being reductive elimination to regenerate the catalyst (ΔG‡ = 11.8 kcal mol−1). This energetic barrier would be easily accessible under the experimental conditions. Several alternative mechanistic pathways were evaluated but are not depicted in Figure 5 for the sake of clarity (see Supporting Information for details). These include steps such as CO insertion from an aryl tetracarbonyl cobalt instead of IM2, and possible outer-sphere nucleophilic acyl substitution instead of reductive elimination to generate product;[21] calculations indicate these involve significant energetic barriers and are unlikely to proceed under our present conditions. The inner-sphere pathway contrasts with the outer-sphere nucleophilic acyl substitution commonly proposed for aminocarbonylation, but inner-sphere reductive elimination is also viable.[13] In addition, computational modelling did not support [Co(CO)4]− as the active catalyst as proposed in previous studies.

We propose the following reaction mechanism for the aminocarbonylation, consistent with our mechanistic and computational studies (Scheme 3). Dicobalt octacarbonyl disproportionates via attack by the amine nucleophile[11,21,22] followed by photodissociation of CO to generate the cobalt tricarbonyl anion. The active cobaltate catalyst then coordinates to the ammonium salt and oxidatively adds to the substrate via concerted SNAr. Migratory insertion of CO subsequently generates an acyl cobalt intermediate which undergoes ligand exchange with the amine nucleophile, followed by C–N bond-forming reductive elimination to deliver the amide product and regenerate the cobalt catalyst.[11,21,22]

Scheme 3.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the cobaltate-catalyzed photochemical aminocarbonylation involving CO photodissociation and concerted SNAr C(sp2)–N activation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a cobalt-catalyzed photochemical deaminative aminocarbonylation of easily accessed aryl trialkylammonium salts via selective C(sp2)–N activation. The transformation uses a commercially available, first-row transition-metal catalyst to efficiently deliver a broad range of benzamides (and esters) under mild conditions and low pressures of CO. Mechanistic and computational studies are consistent with a novel pathway for cobaltate-catalyzed carbonylation involving photodissociation of a carbonyl ligand followed by concerted SNAr-type oxidative addition. Future studies will continue the development of synthetic methods enabled by the unique reaction pathways accessible using anionic cobalt catalysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Award No. R35 GM131708 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. AMV thanks the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellowship for support. We thank the UNC Department of Chemistry NMR Core Laboratory for the use of their NMR spectrometers, supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. CHE-1828183. We thank the UNC Department of Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory for assistance with MS analysis, supported by the National Science Foundation under award number CHE 1726291. We would also like to thank UNC and the Research Computing Center for providing computational resources and support that have contributed to these research results.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].a) Ricci A, Amino Group Chemistry: From Synthesis to the Life Sciences, Wiley, 2008; [Google Scholar]; b) Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML, Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 893–930; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Czarnik AW, Acc. Chem. Res 1996, 29, 112–113; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2007, 6, 834–848; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Singer RA, Sadighi JP, Buchwald SL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Ouyang K, Hao W, Zhang W-X, Xi Z, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 12045–12090; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Garcıá -Cárceles J, Bahou KA, Bower JF, ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12738–12759; [Google Scholar]; c) Wang Q, Su Y, Li L, Huang H, Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45, 1257–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Wang Z-X, Yang B, Org. Biomol. Chem 2020, 18, 1057–1072; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wenkert E, Han A-L, Jenny C-J, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1988, 975–976; [Google Scholar]; c) Blakey SB, MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 6046–6047; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chen Q, Gao F, Tang H, Yao M, Zhao Q, Shi Y, Dang Y, Cao C, ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3730–3736; [Google Scholar]; e) Yang Z-K, Wang D-Y, Minami H, Ogawa H, Ozaki T, Saito T, Miyamoto K, Wang C, Uchiyama M, Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 15693–15699; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Xie L-G, Wang Z-X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 4901–4904; Angew. Chem., 2011, 123, 5003–5006; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zhang H, Hagihara S, Itami K, Chem. Eur. J 2015, 21, 16796–16800; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Zhang X-Q, Wang Z-X, Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 1448–1453; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Chen H, Yang H, Li N, Xue X, He Z, Zeng Q, Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1679–1685; [Google Scholar]; j) Yi Y-Q-Q, Yang W-C, Zhai D-D, Zhang X-Y, Li S-Q, Guan B-T, Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 10894–10897; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Rand AW, Montgomery J, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 5338–5344; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Zhu F, Tao J-L, Wang Z-X, Org. Lett 2015, 17, 4926–4929; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Li J, Wang Z-X, Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14, 7579–7584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kong X, Chen Y, Chen X, Lu Z-X, Wang W, Ni S-F, Cao Z-Y, Org. Lett 2022, 24, 2137–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Roglans A, Pla-Quintana A, Moreno-Mañas M, Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 4622–4643; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gosset C, Pellegrini S, Jooris R, Bousquet T, Pelinski L, Adv. Synth. Catal 2018, 360, 3401–3405; [Google Scholar]; c) Majek M, Jacobi von Wangelin A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 2270–2274; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 2298 –2302; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Xu J-X, Franke R, Wu X-F, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 6180–6182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Xia Z, Zhu Q, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 4110–4113; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wu X-F, Schranck J, Neumann H, Beller M, Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 3702–3704. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brennführer A, Neumann H, Beller M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 4114–4133; Angew. Chem., 2009, 121, 4176–4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Torres GM, Liu Y, Arndtsen BA, Science 2020, 368, 318–323; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu Y, Zhou C, Jiang M, Arndtsen BA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 9413–9420; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sumino S, Fusano A, Fukuyama T, Ryu I, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1563–1574; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sumino S, Ui T, Ryu I, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 3142–3145; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Singh J, Sharma S, Sharma A, J. Org. Chem 2021, 86, 24–48; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kudo K, Shibata T, Kashimura T, Mori S, Sugita N, Chemistry Letters 1987, 16, 577–580. For further information on photochemical carbonylations, see the following reviews and the references therein: [Google Scholar]; g) Peng J-B, Geng H-Q, Wu X-F, Chem 2019, 5, 526–552; [Google Scholar]; h) Zhao S, Mankad NP, Catal. Sci. Technol 2019, 9, 3603–3613; [Google Scholar]; i) Botla V, Voronov A, Motti E, Carfagna C, Mancuso R, Gabriele B, Della Ca’ N, Catalysts 2021, 11, 918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Brunet JJ, Sidot C, Caubere P, J. Org. Chem 1983, 48, 1919–1921. For a non-photochemical, cobalt-mediated carbonylation of quaternary trialkylammonium salts under phase transfer conditions, see: [Google Scholar]; b) Gambarotta S, Alper H, J. Organomet. Chem 1980, 194, C19–C21. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Lei Y, Zhang R, Han W, Mei H, Gu Y, Xiao B, Li G, Catal. Commun 2013, 38, 45–49; [Google Scholar]; b) Lei Y, Zhang R, Wu Q, Mei H, Xiao B, Li G, J. Mol. Catal. A Chem 2014, 381, 120–125; [Google Scholar]; c) Nasr Allah T, Savourey S, Berthet J, Nicolas E, Cantat T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 10884–10887; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 11000 –11003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Veatch AM, Alexanian EJ, Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 7210–7213; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sargent BT, Alexanian EJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 9533 – 9536; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 9633–9636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].See Supporting Information for additional details regarding palladium-catalyzed experiments.

- [13].Wang JY, Strom AE, Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 7979–7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Paras NA, MacMillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 7894–7895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Brunet J-J, Sidot C, Caubere P, Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 1013–1016; [Google Scholar]; b) Brunet JJ, Sidot C, Caubere P, J. Org. Chem 1983, 48, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar]

- [16].See Supporting Information for an alternative SRN1 radical chain pathway and for further comparison to the charge transfer mechanism depicted in Scheme 2.

- [17].a) Dragojlovic V, Gao DB, Chow YL, J. Mol. Catal. A Chem 2001, 171, 43–51; [Google Scholar]; b) Wegman RW, Brown TL, Organometallics 1982, 1, 47–52; [Google Scholar]; c) Turner JJ, George MW, Poliakoff M, Perutz RN, Chem. Soc. Rev 2022, 51, 5300–5329; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Abrahamson HB, in Inorganic Reactions and Methods, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1986, pp. 254–255; [Google Scholar]; e) Mitchener JC, Wrighton MS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 975–977. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Further attempts to elucidate an SRN1 mechanism all provided inconclusive evidence towards a radical chain mechanism. These experiments include competition experiments with multiple leaving groups on the arene substrates. See Supporting Information for details regarding these experiments.

- [19].a) Wang D-Y, Kawahata M, Yang Z-K, Miyamoto K, Komagawa S, Yamaguchi K, Wang C, Uchiyama M, Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 12937; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Maes BU, Verbeeck S, Verhelst T, Ekomié A, Wolff N, Lefèvre G, Mitchell EA, Jutand A, Chem. Eur. J 2015, 21, 7858–7865; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bajo S, Laidlaw G, Kennedy AR, Sproules S, Nelson DJ, Organometallics 2017, 36, 1662–1672; [Google Scholar]; d) Chen Q, Gao F, Tang H, Yao M, Zhao Q, Shi Y, Dang Y, Cao C, ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3730–3736. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hartwig J, Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, 2009; Chapter 5, pp 217–260. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guo J, Pham HD, Wu Y-B, Zhang D, Wang X, ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 1520–1527. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pauson PL, Stambuli JP, Chou T-C, Hong B-C, in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2014, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.