Abstract

Objective:

Research on warning signs, defined as acute risk factors for suicide or suicide attempt, has been slow due to the difficulty of examining the hours and minutes preceding suicidal behavior. This study sought to identify new warning signs and to re-examine warning signs that have been proposed.

Method:

Narrative stories of adult patients with substance use problems hospitalized following a suicide attempt were transcribed. The narrative segments describing the 24-hour period prior to suicide attempt were examined with directed qualitative content analysis using codes based on prior literature and new codes developed inductively.

Results:

The sample (N = 35) was mean age = 40, 51% female, and 49% White non-Hispanic. Analysis of the transcripts of the 24-hour periods (M word count = 637) yielded a broad range of cognitive (e.g., cognitive disturbance such as rumination), behavioral (e.g., alcohol use), emotional (e.g., dramatic mood changes), and social (e.g., social withdrawal) warning signs, along with a small number of cognitions and behaviors that appeared to mark a dangerous shift to acute preparation and intent for attempt, for example ‘self-persuasion to attempt suicide.’

Conclusion:

We posit that a broad range of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social warning signs increase acute risk for suicidal behavior by creating the conditions for a shift to acute preparation and intent, a highly potent category of warning signs.

Keywords: warning sign, acute risk, risk factor, suicide, suicide attempt, qualitative

1. Introduction

Warning signs are acute risk factors present in the hours and minutes preceding suicidal behavior [1]. In contrast to the large literature on distal risk factors, there are little data on warning signs [2] yet, the understanding of warning signs is critical. Warning signs may be used to educate practitioners about signals of acute risk, to inform short-term risk assessment in acute care settings (e.g., emergency departments), and to inform treatment with high-risk populations [3].

In 2003, an expert panel convened to review evidence on warning signs, leading to a consensus report [1]. The panel proposed a list of 12 warning signs organized hierarchically into those requiring immediate intervention to prevent suicidal behavior (e.g., “someone looking for ways to kill themselves”) and warning signs warranting consultation with a mental health professional or crisis hotline (e.g., “hopelessness”). The panel cautioned that the list was based on scant evidence and called for empirical studies of warning signs. Nonetheless, the list remains influential and versions are widely disseminated.

There has been some progress in the empirical study of warning signs, for example an uncontrolled report describing warning signs in the 24 hours preceding suicide attempts in active duty soldiers [4]. More rarely have warning signs’ studies used controlled designs, and these studies have focused on a narrow list of variables [5]. An exception is a controlled study of a broad list of warning signs in an adult sample of patients hospitalized for suicide attempt from civilian and Veterans Administration hospitals [3]. The study used a case-crossover methodology, a within-subjects design in which individuals serve as their own control [6]. It produced the first estimates of acute risk for suicide attempts associated with a broad range of warning signs. Specifically, it identified nine variables that were more likely to be present within 6 hours of the attempt, conceptualized as during the warning signs period, compared to the comparable 6-hour period the day before, conceptualized as during a lower risk control period.

2. Purpose

The lists of warning signs proposed by the expert panel [1] and validated in the aforementioned controlled study [3] are almost certainly incomplete. The primary purpose of the current study is to identify and describe additional variables that may serve as warning signs. In this effort, we drew on two sets of proposed criteria for acute risk for suicidal behavior–Suicide Crisis Syndrome (SCS) and Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance (ASAD). SCS and ASAD criteria are listed in a review of these constructs [7] and elaborated on in a series of empirical studies and discussions of the SCS [8–11], the ASAD [12, 13], and of both constructs [14, 15]. The SCS posits that perceived entrapment and urgency to escape (previously called frantic hopelessness) is the core feature of acute risk for suicidal behavior. Additional indicators of acute risk for suicidal behavior include affective disturbance (e.g., emotional pain), loss of cognitive control (e.g., rumination about one’s own distress/life situation), arousal (e.g., agitation), and social withdrawal (e.g., reduction in breadth of social activity). The ASAD posits that a short-term and dramatic increase in suicidal intent is the core feature of acute risk for suicidal behavior. Additional indicators of acute risk include social alienation (e.g., withdrawal from others) and/or self-alienation (e.g., self-disgust), hopelessness about changing one’s suicidal state and accompanying social/self-alienation, and overarousal (e.g., irritability). Although SCS and ASAD research is promising, to our knowledge this research has not systematically examined narrow risk periods such as the 24 hours preceding a suicide attempt.

3. Method

3.1. Setting and subjects

Data were gathered from adult patients during their hospitalization following a suicide attempt at the [removed for review] who were enrolled in a treatment development study that has been previously described [removed for review]. In the study, the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program, a 3-session evidenced-based treatment to prevent suicide reattempt [16–18], was adapted for use with suicide attempt patients with substance use problems, delivered in preliminary phases that led to further modification, and subsequently evaluated in a pilot randomized controlled trial. The current analysis is based on the subjects who completed one or more sessions of the therapy (N = 35) during the study’s preliminary phases (n = 20) or in the pilot randomized controlled trial (n = 15). Select demographic characteristics (N = 35) include: Mage = 39.6 years (SD = 16.4), 51% female, 78.2% heterosexual/straight, 63.3% White, 49.1% single/never married. See prior reports for more information [removed for review].

3.2. Data source

During the treatment, the story of the suicide attempt was elicited and video recorded. The therapist elicited the narrative by asking the patient to “tell me the story of your suicide attempt in your own words.” When necessary, open-ended questions were used to ask patients to elaborate (e.g., “Can you slow down and walk me through your story?”) [16]. The video recorded narratives were transcribed by a research assistant using a written manual and checked for accuracy and completeness by the second author. Next, the first two authors developed and implemented a procedure to code the narratives based on a temporal framework developed for the project that included four time periods: 1) 24-hour period prior to the suicide attempt, conceptualized as the warning signs period; 2) prior history (i.e., any history that came before the warning signs period); 3) the suicide attempt itself; and 4) the aftermath of the attempt.

3.3. Transcript coding

We analyzed transcript excerpts of the warning signs period only; we excluded excerpts describing prior history, the suicide attempt itself, or its aftermath, with 34 of 35 subjects contributing warning signs data (one subject did not refer to the warning signs period during their narrative). The warning signs narratives were 73 to 1,623 words in length (M = 637 words, SD = 417 words). We used directed qualitative content analysis to code and analyze the warning signs narratives, using prior research combined with an inductive approach [19, 20]. This approach was chosen because it facilitates comprehensive categorization of all relevant text and, although it is structured by predefined constructs (i.e., codes) of interest, it allows for newly identified ideas to arise from the data. To begin, the first author drafted an initial codebook of warning signs codes that were based on prior research that drew on four sources: 1) the warning signs list proposed by the panel of experts [1]; 2) the warning signs that were validated in a controlled study examining a broad list of warning signs [3]; and the proposed criteria for 3) the ASAD and 4) the SCS as listed in a summary of these criteria [7] and elaborated on in empirical reports and reviews of the ASAD and SCS [8–10, 12, 15].

An online randomization program was used to generate the order in which warning signs narratives were coded. An iterative process with two coders was used to further develop the codebook and apply final codes to the narratives. The first two authors independently coded the initial three narratives before reviewing them in a meeting and producing consensus codes. This process identified points of discrepancy and lack of clarity, leading to modification of the codebook. Next, the authors coded an additional four narratives independently, with fewer discrepancies that were resolved, and consensus codes were generated. Thereafter, the first author coded the remaining narratives, and the codes were reviewed by the second author who identified questionable or confusing codes which were revised or clarified in a series of video conferences. Along with applying codes based on prior research, new codes were developed inductively based on the narratives. As a last step, the first author went back through the transcripts and applied the final version of the codebook to all transcripts, and the second author reviewed the final codes, and discrepancies were resolved via discussion. This approach to coding resulted in all text passages being reviewed by two coders, which helped ensure content was not missed and is ideal when concepts being coded require nuanced understanding. The third author, an expert in qualitative analysis, provided input into the codebook development, revision, and coding process in a series of video conferences.

Based on coding successive transcripts, the codebook underwent seven revisions. Modifications to the codebook included consolidating codes, clarifying wording, providing examples from the narratives, and generating new codes using an inductive approach. The SCS criteria ‘loss of cognitive control’ provides an example of consolidation. We began by coding each type of loss of cognitive control described in the SCS, including rumination, cognitive rigidity, unsuccessful attempts at thought suppression, ruminative flooding, and impaired ability to process information. However, distinguishing between specific types of loss of cognitive control proved to be challenging based on the narratives and, ultimately, we consolidated the separate codes into one general ‘loss of cognitive control’ code. An example of a new code developed inductively is ‘self-persuasion to attempt suicide,’ an experience where subjects described building themselves up to attempt suicide, for example by reassuring themselves that suicide will not be devastating to others, will not be painful, will be similar to their everyday experience (e.g., like taking a nap), and/or that things will be taken care of despite their suicide (e.g., care for pets). Multiple codes of the same text were allowed. Text that was not deemed informative (e.g., generic description of one’s work) was not coded.

In sum, the final warning signs (Table 1) contains 37 specific codes organized into 5 categories (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional, social, and arousal/somatic), with 29 codes guided by prior research, along with 8 new inductively developed codes. A more detailed codebook is available by contacting the first author. Analysis focused on tabulating frequencies of codes identified in the narratives, organized 1) by category and 2) by the proposed criteria for the ASAD and SCS.

Table 1.

Warning signs examined and their source.

| Warning Signs Category | Warning Signs Description and Source |

|---|---|

| 1. Cognitive | 1a. Perceiving no reason for living/no sense of purpose in life1,4 |

| 1b. Hopelessness/frantic hopelessness1,2,3 | |

| 1c. Resolving to attempt suicide in the near future (aspect of intent)2 | |

| 1d. Settling on a specific plan/refining a plan/sorting through method options to attempt suicide in the near future (aspect of intent)2 | |

| 1e. Cognitive disturbance (ruminations, rigidity, thought suppression, ruminative flooding, impaired ability to process information)3 | |

| 1f. Self-persuasion to attempt suicide5 | |

| 1g. Actively weighing the decision whether or not to attempt suicide5 | |

| 2. Behavioral | 2c. Suicidal communication1,4 |

| 2a. Making preparations to attempt suicide (aspect of intent)1,2 | |

| 2b. Preparations of personal affairs4 | |

| 2d. Communicating distress to a specific person or attempting to do so5 | |

| 2e. Drug use1 | |

| 2f. Alcohol use1,4 | |

| 2g. Sleep-related difficulties or changes (insomnia, hypersomnia, remaining in bed, nightmares)1,2,3 | |

| 2h. Evasive communication3 | |

| 2i. Acting reckless or engaging in risky activities1 | |

| 2j. Coming upon a method of suicide during a moment of vulnerability5 | |

| 2k. Discounting/rejecting support or reassurance5 | |

| 3. Emotional | 3a. Dramatic changes in mood1,2,3 |

| 3b. Entrapment/feeling trapped1,3 | |

| 3c. Rage, anger, hostility, seeking revenge1,4 | |

| 3d. Anxiety/frantic anxiety/fear1,3,4 | |

| 3e. Emotional pain (sadness, emptiness, hurt)2,3,4 | |

| 3f. Self-alienation (self-disgust, self-hate, self-blame/shame)2 | |

| 3g. Dissociation3 | |

| 3h. Sensory disturbances3 (including voices) | |

| 3i. Acute anhedonia3 | |

| 3j. Emotional depletion/exhaustion5 | |

| 3k. Emotional numbness5 | |

| 4. Social | 4a. Social withdrawal/isolating oneself1,2,3 |

| 4b. Loneliness/perceived absence of reciprocal relationships/perception that nobody cares or understands2 | |

| 4c. Perceived burdensomeness4 | |

| 4d. Disgust with others (include perceiving betrayal)2 | |

| 4e. Negative interpersonal life event/exchange4 | |

| 5.Arousal/Somatic | 5a. Agitation/irritability1,2,3 |

| 5b. Hypervigilance,3 | |

| 5c. Physical pain5 |

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive results

The most frequently identified warning signs are shown in Table 2. Participants frequently described a range of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social warning signs. Within these categories, some experiences were especially likely such as resolving to attempt suicide in the near future (48.5%), making preparations to attempt suicide (43%), emotional pain (46%), and negative interpersonal life event or exchange (51%). Examples of these warning signs include: E.g. 1, “So, I [was] just waiting for the right time to do it. The right time to do it, yes. When nobody was around. Where I couldn’t get caught doing it” (resolving to attempt suicide in the near future); E.g. 2, “I had already packed a few things, including the (method) I was going to take” (making preparations to attempt suicide); E.g. 3, “There’s no other pains out there and I was going through all of them and I just simply couldn’t handle it anymore” (emotional pain); E.g. 4, “[He] was all pissed off at me again. Threatening to do bodily harm and when I got home, my parents were thoroughly convinced I had been drinking and were yelling at me” (negative interpersonal life event/exchange). Unlike other categories, arousal/somatic warning signs were not commonly identified. Some warning signs were identified inductively rather than based on the source literature, most commonly self-persuasion to attempt suicide (46%): E.g. 5, “Either you’re going to do it or you’re not going to do it. You’re not going to sit here and dwell on it. That’s not going to make you do it. I was on my last day.” This warning sign refers to the active process of talking oneself into suicidal behavior which is distinct from merely weighing the decision, an experience that we labeled separately.

Table 2.

Most frequent codes in each warning signs category.

| Code | Participants with Code (n/N) | Overall Frequency of Code (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Warning Signs | ||

| (1c) resolving to attempt suicide in the near future | 48.5% (17/35) | 32 |

| (1f) self-persuasion to attempt suicide | 46% (16/35) | 25 |

| (1d) developing or finalizing an acute plan to attempt suicide | 43% (15/35) | 29 |

| (1e) cognitive disturbance | 37% (13/35) | 23 |

| (1b) hopelessness/frantic hopelessness | 23% (8/35) | 11 |

| Behavioral Warning Signs | ||

| (2a) preparations to attempt suicide | 43% (15/35) | 27 |

| (2d) communication of distress | 31% (11/35) | 14 |

| (2f) alcohol use | 26% (9/35) | 21 |

| (2c) suicidal communication | 23% (8/35) | 13 |

| (2b) preparation of personal affairs | 20% (7/35) | 13 |

| Emotional Warning Signs | ||

| (3e) emotional pain | 46% (16/35) | 41 |

| (3b) entrapment | 40% (14/35) | 30 |

| (3a) dramatic changes in mood | 28.5% (10/35) | 15 |

| (3f) self-alienation | 28.5% (10/35) | 13 |

| (3j) emotional depletion/exhaustion | 23% (8/35) | 11 |

| Social Warning Signs | ||

| (4e) negative interpersonal event/exchange | 51% (18/35) | 42 |

| (4b) loneliness | 40% (14/35) | 31 |

| (4a) social withdrawal | 14% (5/35) | 6 |

| (4d) disgust with others | 14% (5/35) | 17 |

| (4c) burdensomeness | 9% (3/10) | 4 |

| Arousal/Somatic Warning Signs | ||

| (5c) physical pain | 8.5% (3/35) | 9 |

| (5a) agitation/irritability | 3% (1/35) | 1 |

| (5b) hypervigilance | 3% (1/35) | 1 |

Note. Results are shown for the top 5 most frequent warning signs in descending order within each category.

Arousal/somatic warning signs includes 3 warning signs, each are shown.

4.2. Results pertaining to the ASAD and SCS

We combined individual codes, as appropriate, to assess criteria of the SCS and ASAD. For example, the SCS criterion affective disturbance was met by any of the following: 3a (dramatic mood changes), 3d (anxiety/frantic anxiety), 3e (emotional pain), or 3i (acute anhedonia). Results are presented in Table 3 and show that the core SCS criterion entrapment/frantic hopelessness and additional SCS criteria affective disturbance and cognitive disturbance were commonly reported by subjects, with these criteria identified in 37% to 63% of the narratives. Examples include: E.g. 6, “Why keep going on in life with all these thoughts” (entrapment/frantic hopelessness); E.g. 7, “I want to stop caring, I want to stop worrying” (loss of cognitive control); E.g. 8, “I just broke down. I was sitting at the bus stop crying, on the bus crying” (affective disturbance). The core feature of the ASAD, increased suicide intent, was also frequently identified (77% of narratives): E.g. 9, “Once I was pretty decided on suicide, I didn’t want ways to cope. I wanted to just end it.” The ASAD criterion social alienation or self-alienation was also common (68.5% of narratives): E.g. 10, “Nobody wants to be with somebody that’s ugly on the inside” (self-alienation); E.g. 11, “Nobody’s going to care if I’m here or not” (social alienation). The ASAD and SCS criterion hyperarousal or overarousal was less frequently reported (11% of narratives).

Table 3.

Frequency of Suicide Crisis Syndrome (SCS) and Acute Affective Suicidal Disturbance (ASAD) codes.

| Code Type | Relevant Codes | Participants with Code (n/N) |

|---|---|---|

| SCS | ||

| Entrapment or frantic hopelessness | 1b or 3b | 48.5% (17/35) |

| Affective disturbance | 3a or 3d or 3e or 3i | 63% (22/35) |

| Cognitive disturbance | 1e | 37% (13/35) |

| Hyperarousal | 2g or 5a | 11 (4/35) |

| Social withdrawal | 2h or 4a | 17% (6/35) |

| ASAD | ||

| Increased suicide intent | 1c or 1d or 2a | 77% (27/35) |

| Social alienation or self-alienation | 3f or 4a or 4b or 4c or 4d | 68.5% (24/35) |

| Hopelessness (about changing suicide intent, social alienation, and self-alienation) | 1b | 23% (8/35) |

| Overarousal | 2g or 5a | 11 % (4/35) |

4.3. Warning signs indicating acute preparation or intent for suicidal behavior

Guided by the expert panel’s hierarchical organization of warning signs [1], the central role of acute suicidal intent in the ASAD [15], our research and clinical experience, and the process of coding and analyzing the transcripts, we perceived a small number of warning signs to stand out from the rest for their immediacy, explicit focus on suicide, and because they appeared to mark a dangerous shift to the individual assuming an active role in harming themselves. We labeled these variables warning signs of acute preparation or intent. Specifically, we considered three cognitive warning signs (i.e., resolving to attempt suicide in the near future, finalizing a plan to attempt suicide, self-persuasion to attempt suicide) and two behavioral warning signs (i.e., making preparations to attempt suicide, preparing one’s personal affairs) to be warning signs of acute preparation or intent. Along with examples 1, 2, and 5 (above), additional examples of warning signs of acute preparation or intent include: E.g.12, “I had it all planned out. Already knew how to do it then;” E.g.13, “I mean, but I didn’t want to do it around him because I knew he would try and stop me so I waited until he left to take the (method);” E.g.14, “I gave my watches away;” E.g.15, “I quickly made sure my bills were paid and that there was enough money in my checking account for everything to get paid. I put my healthcare proxy out;” E.g.16, “I’m just going to take a nap in my car. Like, I’m not even going to be awake when I die.”

Overall, 85.7% of our sample experienced at least one warning sign of acute preparation or intent. We posit that the final 24 hours preceding a suicide attempt is typified by one or more of these warning signs. Moreover, when examined using controlled study designs, we hypothesize that each of the warning signs associated with acute preparation or intent will be associated with greater acute risk for suicide attempt compared to other warning signs.

4.4. Impulsive or unplanned attempts

In some instances, warning signs of acute preparation or intent occurred or intensified very late during the 24-hour period. In these cases, the suicide attempts were likely impulsive or unplanned [21], a scenario that has been reported as being common in other research of adults with alcohol or substance use problems [22, 23]. Examples include: E.g.17, “I was intoxicated, fairly intoxicated because I don’t just drink a little bit. I made a spontaneous decision while standing there to do that. Drank again, and then (method);” E.g.18, “But when I hung up, I immediately thought: ‘I need to kill myself right now because I have nothing to live for.’ I have these (method) that I (method) and wrote a (4-word suicide note). I left that on my bed.” E.g.19, “I was drinking, and he goes: ‘Oh, well just go kill yourself.’ I go: ‘Oh well fuck you. I guess I will!’ And I ran and grabbed the (method).”

4.5. Warning sign ‘drivers’

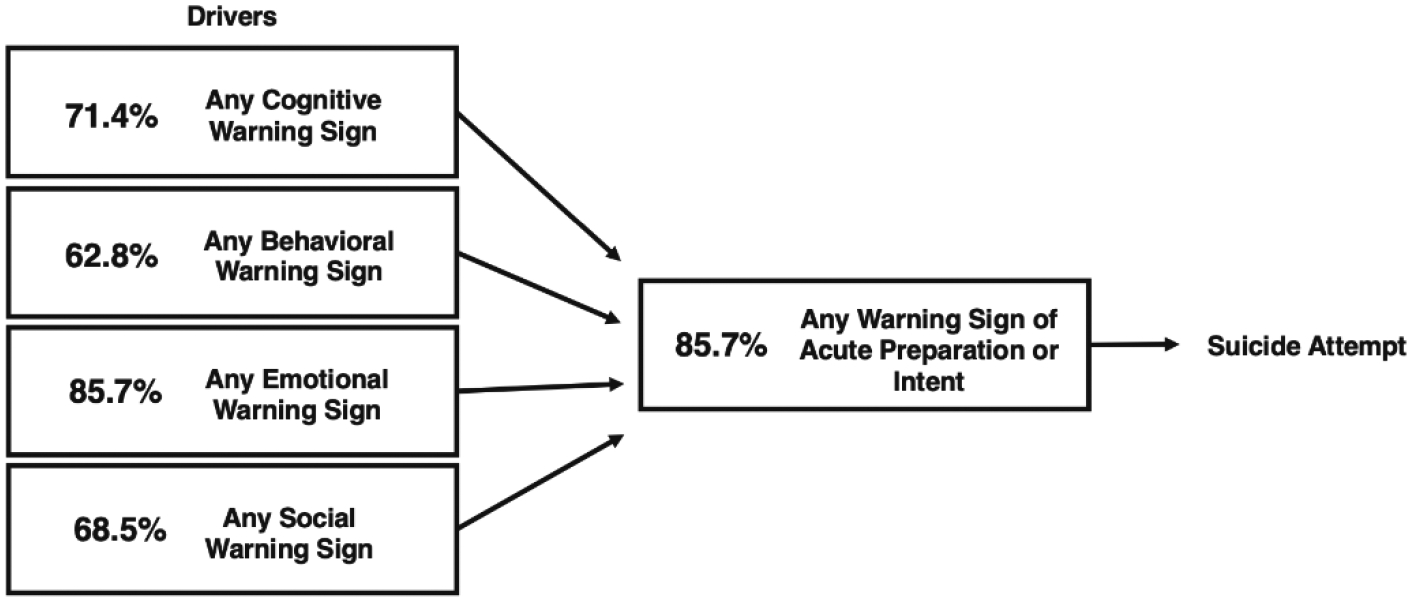

A broad range of other cognitive (e.g., hopelessness), behavioral (e.g., alcohol use), emotional (e.g., dramatic changes in mood), and social (e.g., social withdrawal) warning signs were also evident in the 24-hour preceding a suicide attempt. After removing the warning signs of acute preparation or intent from the behavioral and cognitive categories, the experience of these warning signs were common in the sample, with high percentages of subjects experiencing one or more cognitive- (71.4%), behavioral- (62.8%), emotional- (85.7%), and social- warning sign (68.5%). However, because such experiences may occur in the absence of suicide risk, we hypothesize that studies using controlled research designs will show that acute risk estimates associated with these variables are smaller compared to warning signs of acute preparation or intent. We posit that the role of these variables in acute suicidal risk is that they act as “drivers” that propel individuals into acute risk states. In other words, drivers create the necessary conditions for acute suicidal risk to emerge or intensify by leading to the manifestation of warning signs of acute preparation or intent.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

We used directed qualitative content analysis to examine adult patients’ narratives of the 24-hour period preceding their suicide attempt, conceptualized as the warning signs period. The study achieved its primary goal of identifying new variables that may be warning signs and warrant further study including a strong case for further research of self-persuasion to attempt suicide, a commonly reported experience identified inductively during review of the narratives. In reviewing the data, we were drawn to the wide breadth of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social factors that likely serve as warning signs. We were also drawn to a narrower list of more urgent suicide-focused cognitions and behaviors, for example refining or finalizing a plan that may signal an active and rapidly unfolding suicidal process. The results suggest two general types of warning signs with different levels of urgency, an idea that is reminiscent of the hierarchical organization of warning signs proposed by the expert panel [1]. We considered how these two groups of warning signs interrelate in the final hours and minutes before a suicide attempt, leading to a conceptual model.

5.2. Conceptual model

A conceptual model illustrating the hypothesized relationships between drivers and warning signs of acute preparation or intent is provided (Figure 1). The model is informed by Rudd and colleagues’ hierarchical list [1], and expands on it by proposing new warning signs and by positing a directional relationship between warning signs at different levels of the hierarchy. At the top of the hierarchy is a narrow range of highly potent warning signs of acute preparation or intent that mark a dangerous shift to an individual assuming an active role in self-harm. At the bottom of the hierarchy, there is a much broader set of cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social variables that serve as drivers. The model posits a temporal association between drivers and warning signs of acute preparation or intent, with the onset of drivers generally coming first. Moreover, drivers exert a causal influence on the emergence or intensification of acute risk states, manifested in warning signs of acute preparation or intent. In turn, these variables serve as the key mechanism through which drivers confer acute risk for suicide attempts, consistent with mediation. The model provides a general framework for examining warning signs, with testable hypotheses that require formal study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of warning signs for suicide attempt illustrating proposed associations of drivers and warning signs of acute preparation or intent.

Note. Shown are the percentages of participants with one or more of each type of driver and one or more of each warning sign of acute preparation or intent.

The model is probabilistic, positing that warning signs of acute preparation or intent are a category of highly potent warning signs, but these variables do not inevitably lead to suicide attempts. Indeed, warning signs of acute preparation or intent may result in a range of outcomes including suicide attempt (fatal or nonfatal), the individual reconsidering their intention to attempt suicide, reaching out for help, or another individual or circumstance intervening either inadvertently (e.g., friend stopping by at a crucial moment) or deliberately (e.g., mobile crisis team checking on a patient). It is also true that some warning signs associated with acute preparation or intent (e.g., resolving to attempt suicide) must be present, if even for a matter of seconds, for a suicide attempt to occur. Accordingly, resolving to make an attempt may be considered a necessary but not sufficient condition for suicide attempt. This scenario is common to many risk behaviors, for example the availability of alcohol is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the consumption of alcohol.

The model also posits that a suicide attempt is the product of a dynamic process marked by dramatic escalation in acute risk, particularly in the final hours and minutes. There are other plausible scenarios, for example one could form intent and prepare for a suicide attempt well in advance, with the execution of the attempt being a matter of timing. Indeed, many human behaviors proceed in this manner (e.g., quitting smoking). Alternatively, a suicide attempt could represent a mere continuation of chronic difficulties and symptoms, rather than an acute escalation in risk. However, in our view, the patient narratives were not consistent with these scenarios. Our concept of acute escalation in risk, manifest in warning signs of acute preparation or intent, is also informed by the ASAD core criterion of dramatic increase in suicidal intent [7] and case-crossover research of warning signs that assumes markedly increased risk on the day of a suicide attempt compared to the previous day [3].

If supported by further research, the model may inform risk assessment and decision-making in acute settings such as emergency departments and crisis lines. The simplicity of the model may be an advantage for this purpose. A second implication is the model may inform a straightforward two-step hierarchical response to risk, for example patients may be guided to use one set of strategies in response to drivers and another set-in response to warning signs of acute preparation or intent. A third is that it may help to accelerate research to understand and mitigate a finite number of highly potent warning signs of acute preparation or intent. For example, if self-persuasion to attempt suicide is indeed common in the final hours prior to a suicide attempt, it could inform research of language that patients use in self-persuasion and to develop strategies for patients to recognize and counteract it.

5.3. Limitations

There are limitations. First, it was a qualitative analysis of a small sample of adult patients who screened positive for alcohol and other drug use problems and were hospitalized following a suicide attempt, with unclear generalizability to other populations or settings. Second, we used the frequency with which subjects experienced warning signs as an indicator of importance, but we acknowledge frequency is an imperfect indicator, and variables with low prevalence may still serve as potent risk factors [3]. Third, it cannot be assumed that warning signs that were not identified in the patient narratives did not occur. For example, limited interoceptive awareness, that is that is the ability to sense and respond to internal bodily sensations [24], may have contributed to the low prevalence of arousal/overarousal states. Also, as discussed, we can assume individuals formed intention to attempt suicide at some point, whether it be within 24 hours of the attempt or earlier. Individuals with unplanned or impulsive attempts may also be less likely to recall forming intent. Fourth, we focused on acute warning signs and did not integrate data on more distal risk factors as some research on acute risk has sought to do [25]. Fifth, this was an uncontrolled case series. Accordingly, when we referred to ‘risk’, we base this on prior literature, our research and clinical experience, and theoretical considerations, but we did not produce formal risk estimates (e.g., hazard ratios) for theorized warning signs [3,5]. Sixth, some of the categorizations of warning signs (e.g., ‘cognitive’, ‘behavioral’) were difficult. For example, ‘loneliness’ is a complex construct that is associated with social isolation, the perception of being isolated, and accompanying emotional distress [26], making it unclear if it should be categorized as cognitive, social, or emotional. Seventh, there is overlap among some warning signs, for example frantic hopelessness and entrapment, and the authors of the SCS have used both of these labels to describe the core feature of the SCS. Finally, we based the a priori warning signs on several key sources, but the list was not exhaustive of all potential warning signs mentioned in the extant literature.

6. Conclusion

Using qualitative analysis of patient narratives of their suicide attempts, the study achieved its goal of identifying new variables that may be acute risk factors or warning signs and warrant further study. There is a strong case for further research of the novel warning sign self-persuasion to attempt suicide, a commonly reported experience identified inductively during review of the narratives. Furthermore, results suggest a broad range of warning signs are present in the hours preceding suicide attempts, along with a much narrower range of highly potent suicide-focused cognitions and behaviors, signaling acute suicidal preparation and intent. Based on these observations and prior literature, we posit a conceptual model of acute risk for suicidal behavior featuring two general categories of warning signs, with testable hypotheses.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R34AA02601601; Conner, PI). Clinical Trial Registration – Registry: ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT03300596, Title: Suicidal Adults with Alcohol or Drug Use Problems: A New Hospital-based Treatment, URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03300596

Abbreviations:

- ASAD

Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance

- SCS

Suicide Crisis Syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE, Nock MK, Silverman MM, Mandrusiak M, et al. Warning signs for suicide: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2006;36:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin 2017;143:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bagge CL, Littlefield AK, Wiegand TJ, Hawkins E, Trim RS, Schumacher JA, et al. A controlled examination of acute warning signs for suicide attempts among hospitalized patients. Psychological medicine 2022:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bryan CJ and Rudd MD. Life stressors, emotional distress, and trauma-related thoughts occurring in the 24 h preceding active duty US Soldiers’ suicide attempts. Journal of psychiatric research 2012;46:843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Borges G, Bagge CL, Cherpitel CJ, Conner KR, Orozco R and Rossow I. A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt. Psychological medicine 2017;47:949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maclure M The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. American journal of epidemiology 1991;133:144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Joiner TE, Simpson S, Rogers ML, Stanley IH and Galynker II. Whether called acute suicidal affective disturbance or suicide crisis syndrome, a suicide-specific diagnosis would enhance clinical care, increase patient safety, and mitigate clinician liability. Journal of Psychiatric Practice® 2018;24:274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Galynker I, Yaseen ZS, Cohen A, Benhamou O, Hawes M and Briggs J. Prediction of suicidal behavior in high risk psychiatric patients using an assessment of acute suicidal state: The suicide crisis inventory. Depression and anxiety 2017;34:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schuck A, Calati R, Barzilay S, Bloch-Elkouby S and Galynker I. Suicide Crisis Syndrome: A review of supporting evidence for a new suicide-specific diagnosis. Behavioral sciences & the law 2019;37:223–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yaseen ZS, Hawes M, Barzilay S and Galynker I. Predictive validity of proposed diagnostic criteria for the suicide crisis syndrome: an acute presuicidal state. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2019;49:1124–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Barzilay S, Assounga K, Veras J, Beaubian C, Bloch-Elkouby S and Galynker I. Assessment of near-term risk for suicide attempts using the suicide crisis inventory. Journal of affective disorders 2020;276:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rogers ML, Chiurliza B, Hagan CR, Tzoneva M, Hames JL, Michaels MS, et al. Acute suicidal affective disturbance: Factorial structure and initial validation across psychiatric outpatient and inpatient samples. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017;211:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tucker RP, Michaels MS, Rogers ML, Wingate LR and Joiner TE Jr. Construct validity of a proposed new diagnostic entity: Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance (ASAD). Journal of affective disorders 2016;189:365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Voros V, Tenyi T, Nagy A, Fekete S and Osvath P. Crisis Concept Re-loaded?—The Recently Described Suicide-Specific Syndromes May Help to Better Understand Suicidal Behavior and Assess Imminent Suicide Risk More Effectively. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021;12:598923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rogers ML, Galynker I, Yaseen Z, DeFazio K and Joiner TE. An overview and comparison of two proposed suicide-specific diagnoses: Acute suicidal affective disturbance and suicide crisis syndrome. Psychiatric Annals 2017;47:416–420. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Michel K and Gysin-Maillart A. ASSIP–Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program: A Manual for Clinicians. Hogrefe Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gysin-Maillart AC, Jansen R, Walther S, Jobes DA, Brodbeck J and Marmet S. Longitudinal development of reasons for living and dying with suicide attempters: a 2-year follow-up study. Frontiers in psychiatry 2022;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gysin-Maillart A, Schwab S, Soravia L, Megert M and Michel K. A novel brief therapy for patients who attempt suicide: A 24-months follow-up randomized controlled study of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP). PLoS medicine 2016;13:e1001968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Graneheim UH and Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today 2004;24:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hsieh H-F and Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research 2005;15:1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Conner KR. A call for research on planned vs. unplanned suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2004;34:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Hirsch JK, Knox KL, Meldrum S, et al. Precontemplated and impulsive suicide attempts among individuals with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 2006;67:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bagge CL, Conner KR, Reed L, Dawkins M and Murray K. Alcohol use to facilitate a suicide attempt: an event-based examination. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs 2015;76:474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Current opinion in neurobiology 2003;13:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cohen LJ, Mokhtar R, Richards J, Hernandez M, Bloch-Elkouby S and Galynker I. The Narrative-Crisis Model of suicide and its prediction of near-term suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2022;52:231–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yanguas J, Pinazo-Henandis S and Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ. The complexity of loneliness. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 2018;89:302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]