Abstract

Super-resolved cryogenic correlative light and electron tomography is an emerging method that provides both the single-molecule sensitivity and specificity of fluorescence imaging, and the molecular scale resolution and detailed cellular context of tomography, all in vitrified cells preserved in their native hydrated state. Technical hurdles that limit these correlative experiments need to be overcome for the full potential of this approach to be realized. Chief among these is sample heating due to optical excitation which leads to devitrification, a phase transition from amorphous to crystalline ice. Here we show that much of this heating is due to the material properties of the support film of the electron microscopy grid, specifically the absorptivity and thermal conductivity. We demonstrate through experiment and simulation that the properties of the standard holey carbon electron microscopy grid lead to substantial heating under optical excitation. In order to avoid devitrification, optical excitation intensities must be kept orders of magnitude lower than the intensities commonly employed in room temperature super-resolution experiments. We further show that the use of metallic films, either holey gold grids, or custom made holey silver grids, alleviate much of this heating. For example, the holey silver grids permit 20× the optical intensities used on the standard holey carbon grids. Super-resolution correlative experiments conducted on holey silver grids under these increased optical excitation intensities have a corresponding increase in the rate of single-molecule fluorescence localizations. This results in an increased density of localizations and improved correlative imaging without deleterious effects from sample heating.

Keywords: CLEM, Super-Resolution, Single-Molecule, Fluorescence Microscopy, Cryogenic Electron Tomography

Introduction

Cryogenic electron tomography (cryoET) is a powerful method for observing subcellular organization. This label-free approach provides resolution on the nanometer scale of biological samples frozen in their native-hydrated state. While this resolution is impressive, the approach lacks the contrast necessary to identify the majority of biomolecules of interest. While there is no defined limit as to what structures can be identified, it becomes difficult to identify structures with certainty smaller than ~ 1000 kDa unless they are part of larger assemblies. State-of-the-art methods are able to identify stand-alone structures of ~500 kDa.[1, 2] Despite these efforts, the majority of biomolecules in cells of interest cannot be directly identified from cryoET alone. While specific labelling strategies compatible with cryoET is an active area of research,[3-6] Cryogenic Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CryoCLEM) of fluorescently labelled biomolecules has long been used to provide information on the location of specific biomolecules in the context of cryoET.[7-10] However, the resolution obtainable using diffraction-limited fluorescence microscopy is more than two orders of magnitude lower than the resolution obtainable using cryoET, limiting the utility of the fluorescence information. This limitation has motivated the development of super-resolved cryoCLEM (srCryoCLEM). Various super-resolution approaches have been attempted under cryogenic temperatures and this work has been summarized in several recent reviews.[11-13] The most popular approach has been cryogenic photoactivated localization microscopy, in which the optical experiment is performed on the frozen sample first, followed by cryoET and registration.[14-17]

In this approach, proteins of interest are covalently labelled with special photoactivatable fluorescent molecules or fluorescent proteins that are initially in a dark state, meaning they do not absorb light from an excitation laser and emit fluorescence. These dark labels can be photoactivated using light of another wavelength, typically blue or ultra-violet, that produces some photophysical or photochemical change. This change leads to the emitter now absorbing light from an excitation laser and emitting fluorescence. Fluorescent photons from the emitter can be imaged in widefield using a sensitive camera and the observed point-spread-function can be fit to estimate the emitter’s precise location. This localization process is made significantly more challenging if there are other labels in an emissive state within a diffraction-limited volume. Thus a key step in photoactivated localization microscopy is fluorophore bleaching, where an emissive molecule eventually transitions to a permanent dark state due to some other photophysical or photochemical change. Bleaching is essential as it allows the next set of labels to be photoactivated and subsequently localized. The super-resolved reconstruction is only generated following many rounds of photoactivation, localization, and bleach.

Ironically, one challenge facing the development of srCryoCLEM is the lack of photobleaching and the persistence of fluorescent molecules in an emissive state under these imaging conditions.[17, 18] Two effects compound to prevent bleaching. First, cryogenic temperatures reduce the quantum yield of photobleaching i.e. the probability of an absorption event leading to bleaching. For most observed biological samples near 77 K in an aqueous host, this reduction has been roughly two orders of magnitude,[19-21] but much larger reductions can be observed depending on the fluorescent label, its host environment and temperature.[22, 23] Second, limited optical excitation intensities can be used in correlative experiments on electron microscopy grids before sample heating leads to devitrification of the vitreous ice.[14-18, 24] The usable intensity is roughly two orders of magnitude lower than the intensities used for room-temperature imaging. These two effects compound, leading to emitters remaining in an emissive state approximately 10,000 times longer than under room temperature super-resolution imaging conditions. When individual emitters are in the emissive state for many minutes, the rate at which emitters can be localized is limited. This rate is crucial when longer imaging times lead to increased ice contamination. This limited rate and finite experiment time has made it difficult to recover a dense set of localizations that resolve an extended structure. [18] The first effect, reduced quantum yield of photobleaching, is beneficial as the increase in detected photons allows improved localization precision relative to room temperature. We have exploited this in an approach we have termed Correlative Imaging by Annotation with Single Molecules (CIASM), which is characterized by a small number of very precise localizations (less than 10 nm of lateral uncertainty).[17] The second effect, sample heating, leads to devitrification of the amorphous sample and is purely deleterious in this application. It is therefore a technical challenge of prime importance to overcome.

Here we will examine this sample heating effect. We demonstrate that much of this heating is driven by the holey carbon support film used in standard electron microscopy grids. This is consistent with other correlative cryogenic super-resolution fluorescence studies that were not performed on electron microscopy grids. For example, Hoffman et al. utilized a special sapphire substrate and did not observe devitrification despite high excitation intensities, but this substrate did not allow for cryogenic electron tomography.[25] We will show experimentally that custom electron microscopy grid support films can reduce sample heating by more than an order of magnitude, a result that can be reproduced with simple thermal models. Lastly, we will show that use of higher excitation intensities clearly improves the density of fluorescence localizations recorded within a finite experiment time for labeled proteins in bacteria, leading to considerably improved srCryoCLEM.

Results

Three different support films

Sample heating during fluorescence microscopy depends on how much energy is deposited into a support film and how rapidly that energy can diffuse away. The amount of energy absorbed by the film is dependent on the optical excitation intensity and the absorptivity of the support film. The diffusion of that energy into a heat sink, like the underlying metallic meshwork of the grid, depends on the thermal conductivity of the support film and the layer of vitreous ice. In the case that the grid is not in vacuum, as will be the case here, the thermal energy is also removed via convection to the surrounding cryogenic gas. Lastly, heat can be removed by blackbody radiation, but this radiative heat loss is negligible compared to the heat losses from conduction and convection. An ideal substrate for srCryoCLEM would have high reflectivity and/or low absorptivity, high thermal conductivity, and high electrical conductivity to avoid charge buildup during electron tomography which results in beam-induced motion. Holey carbon grids have been a staple of the cryoET workflow for several decades.[26] While this support material has worked well for electron tomography alone, it is a poor choice for correlative imaging due to its optical absorptivity and poor thermal conductivity. These properties lead to substantial localized heating during optical imaging.

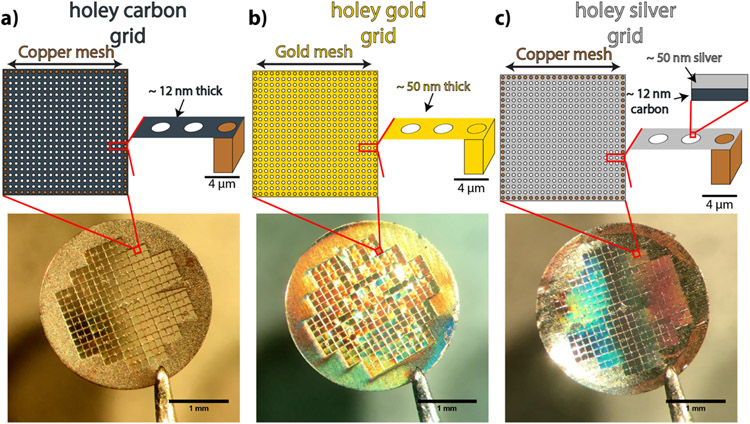

Metals are much better thermal conductors than amorphous carbon and can be highly reflective. In order to demonstrate the superiority of metallic support films for srCryoCLEM experiments, we tested the three different grid types shown in Figure 1. Each grid used a 200 mesh finder grid geometry and each had an R 2/2 holey support film, but the support films differed in composition. One was composed of amorphous carbon, one of gold, and one of silver deposited on carbon. The silver and carbon support films had an underlying metallic mesh composed of copper while the holey gold support film had a gold mesh. These three grids will be referred to throughout the text as the carbon grid, gold grid, and silver grid based on the main constituent of their support films. Various gold films have already been explored for their applications in single-particle cryoEM where they have had great success in reducing beam-induced motion and the crinkling that occurs due to differential thermal expansion coefficients between the support film and metallic mesh.[27, 28] This has led to their commercialization, for example, by Quantifoil as so-called “gold UltrAuFoils.” The new silver grids reported here are produced in a similar way to the gold grids by depositing a thin layer of silver on top of the standard holey carbon grid, see Methods section for further details on the deposition. However, unlike the gold grids, the carbon was not etched away because it was observed that etching tarnished the silver surface, see Figure S1.

Figure 1:

Low magnification optical image and cartoon top and side views of the three electron microscopy grid types used in this study. (a) R 2/2 holey carbon support film on a 200 mesh copper G200F1 finder grid geometry (Quantifoil N1-C16nCuG1-01). (b) Custom ordered grid with gold ultrAuFoil support film on a 200 mesh gold H2 finder grid geometry (Quantifoil N1-A16nAuH2-01). (c) The same support film and grid as in a with a 50 nm layer of silver deposited on the top surface.

Table 1 summarizes the pertinent material properties of the three different grid types using values determined from the literature; see supporting information for more details. These material properties will dictate their thermal response to optical excitation. While both metallic grids do absorb more optical energy than the standard carbon grid, they are substantially better thermal conductors (Table 1), which results in much better dissipation of the absorbed energy away from the irradiated region.

Table 1:

Optical and thermal properties of the three films and amorphous ice. Note that the thermal conductivity values for the gold and silver films takes into account effects due to crystalline domain size and temperature. See SI for further details.

| Percentage of incident 561 nm light absorbed by thin film |

References | |

|---|---|---|

| Amorphous carbon | 3% for 12 nm thick film | [29, 30] |

| Gold | 14% for 50 nm thick film | [31, 32] |

| Silver | 4.5% for 50 nm thick film | [33, 34] |

| Amorphous ice | negligible | |

| Thermal conductivity of thin film | ||

| Amorphous carbon | 0.3 W/mK | [35-37] |

| Gold | 72 W/mK | [38-40] |

| Silver | 64 W/mK | [38-40] |

| Amorphous ice | 1 W/mK | [41, 42] |

Devitrification Thresholds

Samples for cryoET are generally prepared via rapid freezing of an aqueous biological sample in liquid ethane. The freezing process must be fast enough to form amorphous ice (also known as vitreous ice or hyperquenched glassy water).[43] Following sample preparation, the samples must be maintained under cryogenic conditions until the completion of the cryoET experiments, typically at 77 K. A critical temperature threshold exists at ~135 K where there is an irreversible phase transition from amorphous ice to multicrystalline ice that obscures transmission electron micrographs.[44] Therefore the optical intensity that heats the sample and leads to a steady-state temperature above ~135 K is of key importance.

In order to determine this devitrification threshold for the three different support films, cultures of the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus were plunge frozen on the three different grid types, see Methods section for further details. C. crescentus samples were used as a representative cellular sample that produced fairly consistent ice as compared to mammalian cells. These samples were then loaded on a cryogenic light microscope.[17] Bright field illumination was used to center a grid square with an abundance of cells in the field of view. The grid square was then illuminated with a 561 nm continuous wave laser which produced a Gaussian excitation profile in the sample plane with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ~35 μm. Grid squares were illuminated for five minutes at a time with a constant intensity. The excitation intensity was then varied and adjacent grid squares were imaged. Following optical excitation of several grid squares at various intensities, samples were unloaded from the light microscope and the same regions were imaged in cryogenic electron microscopy to assess ice crystallinity. Figure 2a and supplementary Figures S2 and S3 show the results of these experiments. A further experiment was conducted where micrographs were taken prior to optical excitation to verify cells were well vitrified and post excitation to prove that the sample was indeed devitrified due to optical excitation and not simply poorly vitrified, see figure S4.

Figure 2:

Thresholds for optical excitation that lead to sample devitrification. a) Top row shows samples excited with intensities just below the threshold. Bottom row shows samples excited with intensities just above the threshold. Listed intensities are the peak intensity of the 561 nm Gaussian beam profile. b) Analysis of vitrification state of all grid squares analyzed post-illumination to determine devitrification threshold ranges found in this study. Devitrification was assessed at the center of each grid square adjacent to the peak optical intensities. Each mark indicates a grid square illuminated for five minutes with the peak intensity listed on the x-axis. Dashed lines indicate the intensity regime in which grids of each support film type are near the devitrification threshold.

All three different support films exhibited clear transitions from an amorphous ice to crystalline ice, but the excitation threshold for this transition varied substantially for the different materials. For the carbon grids this threshold was in the range 50-75 W/cm2; for the gold grids this threshold was 250-300 W/cm2; and crystalline ice formation was not seen on the silver grids until 1000-1250 W/cm2. Figure 2b shows analysis of all grids and grid squares used to determine the observed threshold bounds. In all cases optical excitation below the threshold ranges listed above maintained amorphous ice, and excitation above these threshold ranges led to crystalline ice except for the standard carbon grid where the sample was observed to melt completely around ~300 W/cm2 at which point the relative motion of cells on the grid was visible by light microscopy. The observed heating was localized in all cases to the grid square that was being optically excited. When the sample was excited with intensities just above the devitrification threshold, the damage was restricted to the region corresponding to the center of the Gaussian excitation beam and cells in the periphery of the grid square remained in an amorphous ice matrix, see Figure S5. In all cases, adjacent squares retained vitreous ice.

Thermal Model

A simple thermal model was constructed using the parameters listed in Table 1 to test our understanding of the mechanism leading to sample heating, see Figure 3. The geometry was constructed to represent an individual grid square for a 200 mesh electron microscopy grid and values of absorptivity and conductivity are scaled to reflect the holey support film geometry, but the holes were not explicitly included. The simulation was 90 μm on a side and included the support film as well as a 50 nm thick layer of amorphous ice. This thin layer of ice is not reflective of the specimen thickness, but rather the thickness of the ice that more uniformly covers the grid and provides thermal contact to the underlying metallic mesh. The layer of ice provides a small amount of thermal conduction that increases with thickness but does not add any appreciable absorption. The choice of thickness impacts the results for the carbon grid, but does not significantly change the results for the gold or silver grid within a reasonable range of ice thicknesses, see Figure S6. The effect of ice thickness could explain some of the discrepancies in devitrification thresholds reported in the literature.[14, 15, 17] The model solved the steady-state two-dimensional heat equation,

| (1) |

where k is the sum of the thermal conductivity of the support film and amorphous ice, T(x, y) is the temperature as a function of spatial coordinates x and y, Q(x, y) is the heating due to optical absorption of the Gaussian excitation beam, h is the convective heat transfer coefficient from liquid nitrogen boil off taken to be 20 W/m2K[45], and Text is the temperature of the nitrogen external to the grid taken to be 77 K. The boundary conditions for Equation 1 were taken to be fixed at 77 K representing the relatively large and well thermally connected metallic mesh underlying the substrate.

Figure 3:

Simulation of optically driven sample heating. a) Simulation geometry intended to represent a single grid square. The boundaries of the grid square were fixed to be 77 K and sample heating was due to the absorption of a 561 nm laser with a Gaussian beam profile. The amount of energy absorbed and how it was dissipated depended on the various support film material properties. b) Representative isotherms from solving equation 1 for the standard carbon grid illuminated by a Gaussian beam with a peak intensity of 50 W/cm2. The red star marks the peak temperature, in this case ~120 K c) Plot of the peak temperature as a function of excitation intensity for the three different support films. The red star is the same as that shown in b.

The temperature profile of the grid square at steady-state, T(x, y), was simulated for various excitation fluences provided by optical irradiation at various intensities for five minutes. The results of the model, which has no free parameters, showed devitrification occurring at approximately 65 W/cm2, 600 W/cm2, and 1700 W/cm2 for carbon, gold, and silver holey films respectively. This is in good agreement with the experimental results, which produced devitrification between 50 and 75 W/cm2 for carbon, 250 and 300 W/cm2 for gold, and 1000 and 1250 W/cm2 for silver support films. The slight overestimate of thresholds for both metallic grids could be due to numerous assumptions in the model, most notably the fixed boundary conditions and the ambient temperature surrounding the grid.

Improved Correlative Imaging

The ultimate goal of this work is to produce superior srCryoCLEM results by alleviating the harsh constraints on optical excitation intensity imposed by standard holey carbon grids. It is essential for this application that the grid support films generate little fluorescent background. Figure 4 shows the autofluorescence generated by the three different support films at room temperature. The holes in the substrate are visible for all grid types, but most pronounced in the gold grids with a clear ring of emission surrounding each hole. The source of this structured autofluorescence is unknown and was not removed by additional glow discharging. Because the details of this grid manufacturing protocol are proprietary, it is difficult to know the root cause of this highly structured background, but a similar effect was observed in the silver grids when they were insufficiently glow discharged prior to silver coating, see SI Figure S7, suggesting that prior to coating the autofluorescence may be removed. The carbon grids also generate a substantial amount of background, but are more uniformly autofluorescent than the gold grids. The silver grids, when properly glow discharged prior to coating, are substantially less autofluorescent than either the gold or carbon grids. This improvement coupled with the increased allowed excitation intensities makes them a logical choice for srCryoCLEM experiments.

Figure 4:

Grid autofluorescence due to 561 nm optical excitation at room temperature for a) carbon grid, b) gold grid, and c) silver grid displayed with the same intensity scaling. d) Mean background measured for each of the three different grid types. Error bars show the standard deviation of background measured from six different grid squares for each grid type.

To test the effective use of silver grids in an srCryoCLEM experiment, C. crescentus cells expressing an inducible fusion of the protein PopZ to the red photoactivatable fluorescent protein PAmKate were investigated.[18, 46] PopZ is a protein that localizes to the polar region of C. crescentus where it forms a phase separated microdomain that excludes certain biomolecules while sequestering others.[47-49] Ribosomes are excluded from this PopZ microdomain, and because ribosomes are easily identifiable in cryoET reconstructions their absence makes the PopZ microdomain identifiable. Cells were plunge frozen on silver grids and fluorescently imaged at 77 K, see Figure 5. Fluorescent imaging was performed as previously described in [17], except the beam profile and excitation intensity was modified to be a Gaussian of FWHM 35 μm with a peak intensity of 1000 W/cm2, or about 20 times more intense than was used previously. This increase in excitation intensity had a corresponding decrease in the on-times of emitters as can be seen in Figure 5a and b. This is expected for optically induced transitions to a bleached state. Following the protocol described in [17], individual PAmKate emitters were merged across frames and localized. While there is a reduction in on-times of the emitters there is a corresponding increase in the brightness of the emitter due to increased rates of optical excitation. This keeps the lateral localization precision consistent with previous results obtained on the carbon grids at just under 10 nm. [17, 18] The order of magnitude reduction in on-times allows for a corresponding increase in the number of localizations that can be obtained in a finite experiment time. Figure 5e shows 53 localizations in a single cell pole acquired in just 40 minutes compared to our best efforts on carbon grids, published previously, which obtained just 16 localizations in 180 minutes.[17] The ultrastructural context for these locations can be observed following registration of the single-molecule localization data with a cryoET reconstruction; see Methods section for further details regarding the registration process. From the registered data, it is clear that the ultrastructure was maintained despite the sustained 1000 W/cm2 excitation intensity. Supplemental video 1 shows further segmentation and visualization of the fluorescent localizations in the three-dimensional context provided by cryoET.

Figure 5:

Improved single-molecule imaging and srCryoCLEM using silver grids demonstrated by imaging of PAmKate-PopZ fusion in C. crescentus. a) Background subtracted fluorescence brightness trace taken from an integrated cell pole imaged on a carbon grid with 50 W/cm2. Green highlights the contributions from a single emitter and gray denotes the estimated background. b) The same as panel a except imaged on silver support film with 1000 W/cm2. Note the difference in time the emitters spend in an emissive state. c) Histogram of lateral localization precision for emitters imaged on silver grids. Precision is determined experimentally from the standard error of the mean from localizations of the same emitter across multiple frames. Localization data comes from 10 cells and 303 emitters. d). Central slice of a representative tomographic reconstruction of a C. crescentus cell. e) Overlay of single-molecule fluorescent localizations (green circles) and central slice of cryoET reconstruction. Each circle is centered on the estimated location of an individual emitter with the radius of the circle being that emitter’s localization precision. There is an additional registration error, i.e. an error in the alignment of fluorescence localizations and CryoET data, of ~30 nm that is not shown, see Materials and Methods section. This registration error would be the same for all localizations and would serve to shift the cloud of localizations slightly. The zoom shows the polar region with the ribosome excluded region manually annotated in red.

Conclusion

Often researchers are faced with a difficult decision of imaging their biological sample with super-resolution fluorescence microscopy, which provides single-molecule sensitivity and specificity, but little context, or imaging using cryogenic electron tomography, which provides molecular scale resolution and detailed cellular context; however it is likely that the biomolecule of interest is not directly identifiable. srCryoCLEM offers the promise of the best of both imaging modalities, but frequently the infrastructure necessary to conduct srCryoCLEM experiments is lacking. Heating due to optical pumping has been a significant limitation to conducting srCryoCLEM experiments. The results presented here demonstrate the inadequacies of the standard carbon grid and show how a simple silver or gold deposition atop the carbon grid can substantially improve their performance. Under 561 nm illumination, gold grids, which may be more biocompatible for cultured cells compared to silver grids, showed a ~5x improvement in excitation intensity prior to devitrification as compared to standard carbon grids and silver grids could maintain vitreous samples under illumination intensities that are ~20× greater than threshold for carbon grids. This increased excitation intensity has a corresponding increase in the density of localizations that can be acquired in the same experiment time with a corresponding increase in the quality of srCryoCLEM imaging.

Materials and Methods

Silver grid production:

R 2/2 holey carbon on copper G200F1 finder mesh grids were glow discharged in air at 50 mTorr for 8 minutes at an RF power setting of 6.8 W in a Harrick PDC-32G plasma cleaner normally used for cleaning glass coverslips. These grids were loaded with the carbon side facing the metallic sources in a homebuilt electron beam deposition system. The chamber was evacuated to ~5×10−7 Torr. A 50 Å layer of chromium was deposited at ~ 1 Å/s to wet the surface of the carbon. This was followed by a 500 Å layer of silver deposited at 1-3 Å/s. The final thickness was chosen to limit transmitted light that would be absorbed by the underlying amorphous carbon and was chosen to match the thickness of the gold grid. Figure S8 shows representative micrographs of the silver grids immediately following their production.

Sample preparation and plunge freezing:

C. crescentus cells encoding PAmKate-PopZ under a xylose promoter were cultured into the late log stage of growth in PYE media as in reference [50]. If fluorescence imaging was to be performed they were induced with 0.3% xylose for 3 hours. Cells were concentrated 5× by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 3 minutes. Approximately 3μl of this concentrated suspension of cells in M2G media was deposited onto electron microscopy grids, blotted from both sides for 1.5-3 seconds, and plunge-frozen (Gatan CP3). Prior to plunge freezing the carbon and gold grids were glow discharged with a Harrick PDC-32G at a setting of 6.8 W, however when glow discharging was attempted with the silver grids a noticeable tarnish developed. Instead, silver grids were pretreated by soaking in detergent (0.1% (w/v) DDM) for an hour, rinsed, and then allowed to dry for ~ 30 minutes prior to plunge freezing. The pretreatment made the grids acceptably hydrophilic while preserving the mirrored silver surface.

Cryogenic single-molecule fluorescence microscopy:

Cryogenic single-molecule fluorescence microscopy was performed in a manner similar to what was described previously.[17, 18] The key distinction here is the obvious increase in illumination intensity. Briefly, the tip of a long working distance objective (Nikon CFI Tu Plan Apo 100×/N.A. 0.9) was immersed in the cold nitrogen vapor in the sample chamber of a cryogenic fluorescence stage (CMS196 Linkam Scientific) just above the plunge frozen grid. The cryogenic stage holds the sample grid at cryogenic temperatures through strong thermal contact between the grid and a copper bridge that is partially submerged in a liquid nitrogen reservoir. Fluorescence was excited using a 561-nm laser (Coherent Sapphire). Photoactivation was achieved using short pulses (50 to 500 ms) of ~5 to 100 W/cm2 of 405-nm laser (Coherent Obis). Both the intensity and duration of the 405-nm pulses were adjusted to achieve sufficient activation while avoiding excess emitter overlap as much as possible. Fluorescence emission from 561-nm excitation was filtered from scattered excitation light using a dichroic mirror (Chroma ZT405/488/561rpc) as well as a bandpass and a 561 notch filter (Edmund Optics 624/40 and Chroma ZET561NF). A 1-m focal length cylindrical lens was mounted just prior to the camera (Andor iXon) to generate an astigmatic PSF that was used for live drift correction using custom Labview acquisition software. Drift correction was performed by fitting the PSF of 40-nm fluorescent polystyrene beads in the field of view. While the astigmatic PSF could be used for 3D localization, all localizations were simply projected into the x-y plane. Fluorescence frames were collected at 2 Hz and frames were drift corrected using cross-correlation. These drift-corrected frames were then used for subsequent data analysis as described in reference [17].

Excitation intensities at the sample plane were determined by measuring the 561 nm laser power after the objective (Newport 1919-R) and distributing that power according to a Gaussian fit to a beam profile. Beam profiles were measured by exciting a dense layer of dye molecules (Rhodamine 590) in a thin polymer layer that was spun coat onto a glass coverslip. The same filter set listed above was used for beam profile measurements and when assessing background levels of grids at room temperature, as shown in Figure 4.

Registration of single-molecule localizations and CryoET reconstructions:

Registration of the single-molecule fluorescence localizations with cryoET reconstructions followed the protocol outlined in Dahlberg et al.[17] Briefly, fluorescence data was first registered to a grid square montage from CryoEM. The manually identified center positions of the holes in the holey support film, which are clearly visible in both modalities, adjacent to the cell of interest were used to compute a “projective” transformation from the fluorescence space to the montage space. The montage was then registered to the higher resolution tomography data using manually identified positions of 25 nm diameter gold beads that were added to the sample prior to freezing. The gold bead positions were identified in the montage as well as the axial projection of the tomographic reconstruction. The bead positions were used to compute a “similar” transformation from the montage space to the tomographic space. This serial process of “projective” and “similar” transformations was estimated earlier to have an uncertainty of ~30 nm based on experimental errors observed in performing the registration process on fluorescent beads.[17]

Simulated heating:

Models of grid temperature profiles were implemented in Matlab using the built in PDE Model for the two-dimensional steady-state heat equation. The true three-dimensional geometry was simplified to two dimensions based on the assumption that temperature would not vary from the top of the thin film to the bottom and instead only varied laterally. Convective cooling was applied to both the top and bottom surface of the grid resulting in an effective doubling of the convective cooling coefficient compared to cooling on one surface alone.

Electron microscopy and tomography:

Three different electron microscopes were used throughout this manuscript. Micrographs used for the assessment of silver and gold grain size displayed in Figure S9 were acquired at room-temperature using a 100-keV electron microscope (Morgagni FEI) with a CCD detector (Gatan Orius). Devitrification thresholds displayed in Figure 2 were assessed by single transmission micrographs taken using a 200-keV cryogenic electron microscope (Glacios Thermo Fisher) equipped with a direct detector (Gatan K2). Lastly, the correlative tomography shown in Figure 5 was acquired using a 300-keV cryogenic electron microscope (Titan Krios Thermo Fisher) equipped with a direct detector (Gatan K3) and energy filter. Tilt series were acquired in a dose-symmetric manner in 1° steps from −45° to 45°. Total dose was 106 e−/Å2 with an effective pixel size of 3.45 Å/pixel and a target defocus of −10 μm. Reconstructions were performed in IMOD.[51]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Tom Carver at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF) for the production of the silver grids and helpful conversations. The SNSF is supported by the National Science Foundation under award ECCS-2026822. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants R35GM118067 (to W.E.M.), and U24GM1139166 (to W.C.), W.C. is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Intercampus Research Award Investigator, and W.E.M. is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Intercampus Research Award Collaborator. P.D.D. was supported in part by the Panofsky Fellowship at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and by grant 2021-234593 from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation. D.D.P. was supported by a Stanford Graduate Fellowship.

References

- 1.Albert S, Wietrzynski W, Lee CW, Schaffer M, Beck F, Schuller JM, Salome PA, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W, and Engel BD, Direct visualization of degradation microcompartments at the ER membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020. 117(2): p. 1069–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai W, Chen MY, Myers C, Ludtke SJ, Pettitt BM, King JA, Schmid MF, and Chiu W, Visualizing Individual RuBisCO and Its Assembly into Carboxysomes in Marine Cyanobacteria by Cryo-Electron Tomography. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2018. 430(21): p. 4156–4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Mercogliano CP, and Löwe J, A Ferritin-Based Label for Cellular Electron Cryotomography. Structure, 2011. 19(2): p. 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercogliano CP and DeRosier DJ, Gold nanocluster formation using metallothionein: mass spectrometry and electron microscopy. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2006. 355(2): p. 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martell JD, Deerinck TJ, Lam SS, Ellisman MH, and Ting AY, Electron microscopy using the genetically encoded APEX2 tag in cultured mammalian cells. Nature protocols, 2017. 12(9): p. 1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oda T and Kikkawa M, Novel structural labeling method using cryo-electron tomography and biotin–streptavidin system. Journal of structural biology, 2013. 183(3): p. 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz CL, Sarbash VI, Ataullakhanov FI, McIntosh JR, and Nicastro D, Cryo-fluorescence microscopy facilitates correlations between light and cryo-electron microscopy and reduces the rate of photobleaching. Journal of microscopy, 2007. 227(2): p. 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jun S, Ro HJ, Bharda A, Kim SI, Jeoung D, and Jung HS, Advances in Cryo-Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy: Applications for Studying Molecular and Cellular Events. Protein Journal, 2019. 38(6): p. 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metskas LA and Briggs JAG, Fluorescence-Based Detection of Membrane Fusion State on a Cryo-EM Grid using Correlated Cryo-Fluorescence and Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Microscopy and microanalysis : the official journal of Microscopy Society of America, Microbeam Analysis Society, Microscopical Society of Canada, 2019. 25(4): p. 942–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampton CM, Strauss JD, Ke Z, Dillard RS, Hammonds JE, Alonas E, Desai TM, Marin M, Storms RE, Leon F, Melikyan GB, Santangelo PJ, Spearman PW, and Wright ER, Correlated fluorescence microscopy and cryo-electron tomography of virus-infected or transfected mammalian cells. Nature Protocols, 2017. 12(1): p. 150–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlberg PD and Moerner WE, Cryogenic Super-Resolution Fluorescence and Electron Microscopy Correlated at the Nanoscale. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 2021. 72(1): p. 253–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeRosier DJ, Where in the cell is my protein? Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics, 2021. 54: p. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian B, Xu X, Xue Y, Ji W, and Xu T, Cryogenic superresolution correlative light and electron microscopy on the frontier of subcellular imaging. Biophys Rev, 2021. 13(6): p. 1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang YW, Chen S, Tocheva EI, Treuner-Lange A, Lobach S, Sogaard-Andersen L, and Jensen GJ, Correlated cryogenic photoactivated localization microscopy and cryo-electron tomography. Nature methods, 2014. 11(7): p. 737–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuijtel MW, Koster AJ, Jakobs S, Faas FGA, and Sharp TH, Correlative cryo super-resolution light and electron microscopy on mammalian cells using fluorescent proteins. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu B, Xue Y, Zhao W, Chen Y, Fan C, Gu L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Sun L, Huang X, Ding W, Sun F, Ji W, and Xu T, Three-dimensional super-resolution protein localization correlated with vitrified cellular context. Scientific Reports, 2015. 5: p. 13017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlberg PD, Saurabh S, Sartor AM, Wang JR, Mitchell PG, Chiu W, Shapiro L, and Moerner WE, Cryogenic single-molecule fluorescence annotations for electron tomography reveal in situ organization of key in Caulobacter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020. 117(25): p. 13937–13944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlberg PD, Sartor AM, Wang JR, Saurabh S, Shapiro L, and Moerner WE, Identification of PAmKate as a Red Photoactivatable Fluorescent Protein for Cryogenic Super-Resolution Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018. 140(39): p. 12310–12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulleman CN, Li W, Gregor I, Rieger B, and Enderlein J, Photon Yield Enhancement of Red Fluorophores at Cryogenic Temperatures. ChemPhysChem, 2018. 19(14): p. 1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisenburger S, Jing B, Hänni D, Reymond L, Schuler B, Renn A, and Sandoghdar V, Cryogenic Colocalization Microscopy for Nanometer-Distance Measurements. ChemPhysChem, 2014. 15(4): p. 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Gros MA, McDermott G, Uchida M, Knoechel CG, and Larabell CA, High-aperture cryogenic light microscopy. Journal of microscopy, 2009. 235(1): p. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banasiewicz M, WiÄ…cek D, and Kozankiewicz B, Structural dynamics of 2, 3-dimethylnaphthalene crystals revealed by fluorescence of single terrylene molecules. Chemical physics letters, 2006. 425(1-3): p. 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werley CA and Moerner WE, Single-molecule nanoprobes explore defects in spin-grown crystals. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2006. 110: p. 18939–18944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlberg P, Perez D, Su Z, Chiu W, and Moerner WE, Cryogenic Correlative Single-Particle Photoluminescence Spectroscopy and Electron Tomography for Investigation of Nanomaterials. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2020. 59(36): p. 15642–15648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman DP, Shtengel G, Xu CS, Campbell KR, Freeman M, Wang L, Milkie DE, Pasolli HA, Iyer N, Bogovic JA, Stabley DR, Shirinifard A, Pang S, Peale D, Schaefer K, Pomp W, Chang C-L, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Kirchhausen T, Solecki DJ, Betzig E, and Hess HF, Correlative three-dimensional super-resolution and block-face electron microscopy of whole vitreously frozen cells. Science, 2020. 367(6475): p. eaaz5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ermantraut E, Wohlfart K, and Tichelaar W, Perforated support foils with pre-defined hole size, shape and arrangement. Ultramicroscopy, 1998. 74(1-2): p. 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo CJ and Passmore LA, Electron microscopy: Ultrastable gold substrates for electron cryomicroscopy. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2014. 346(6215): p. 1377–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naydenova K, Jia PP, and Russo CJ, Cryo-EM with sub-1 angstrom specimen movement. Science, 2020. 370(6513): p. 223-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou XL, Suzuki T, Nakajima H, Komatsu K, Kanda K, Ito H, and Saitoh H, Structural analysis of amorphous carbon films by spectroscopic ellipsometry, RBS/ERDA, and NEXAFS. Applied Physics Letters, 2017. 110(20). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laidani N, Bartali R, Gottardi G, Anderle M, and Cheyssac P, Optical absorption parameters of amorphous carbon films from Forouhi-Bloomer and Tauc-Lorentz models: a comparative study. Journal of Physics-Condensed Matter, 2008. 20(1). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yakubovsky DI, Arsenin AV, Stebunov YV, Fedyanin DY, and Volkov VS, Optical constants and structural properties of thin gold films. Optics Express, 2017. 25(21): p. 25574–25587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenblatt G, Simkhovich B, Bartal G, and Orenstein M, Nonmodal Plasmonics: Controlling the Forced Optical Response of Nanostructures. Physical Review X, 2020. 10(1). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakic AD, Djurisic AB, Elazar JM, and Majewski ML, Optical properties of metallic films for vertical-cavity optoelectronic devices. Applied Optics, 1998. 37(22): p. 5271–5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werner WSM, Glantschnig K, and Ambrosch-Draxl C, Optical Constants and Inelastic Electron-Scattering Data for 17 Elemental Metals. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 2009. 38(4): p. 1013–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng QY, Braun PV, and Cahill DG, Thermal Conductivity of Graphite Thin Films Grown by Low Temperature Chemical Vapor Deposition on Ni (111). Advanced Materials Interfaces, 2016. 3(16). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullen AJ, O'Hara KE, Cahill DG, Monteiro O, and von Keudell A, Thermal conductivity of amorphous carbon thin films. Journal of Applied Physics, 2000. 88(11): p. 6317–6320. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balandin AA, Shamsa M, Liu WL, Casiraghi C, and Ferrari AC, Thermal conductivity of ultrathin tetrahedral amorphous carbon films. Applied Physics Letters, 2008. 93(4). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S and Vradis GC, Thermal-Conductivity of Thin Metallic-Films. Journal of Heat Transfer-Transactions of the Asme, 1994. 116(1): p. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell R, Ho CY, and Liley PE, Thermal conductivity of selected materials. Vol. 8. 1966: US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kittel C, Introduction to solid state physics. 5th ed. 1976, New York: Wiley. xiv, 599 p. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson O, Thermal conductivity of normal and deuterated water, crystalline ice, and amorphous ices. Journal of Chemical Physics, 2018. 149(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersson O and Suga H, Thermal conductivity of amorphous ices. Physical Review B, 2002. 65(14). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubochet J, Adrian M, Chang J-J, Homo J-C, Lepault J, McDowall AW, and Schultz P, Cryo-electron microscopy of vitrified specimens. Quarterly reviews of biophysics, 1988. 21(2): p. 129–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dowell LG and Rinfret AP, Low-Temperature Forms of Ice as Studied by X-Ray Diffraction. Nature, 1960. 188(4757): p. 1144–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosky P, Balmer RT, Keat WD, and Wise G, Exploring engineering: an introduction to engineering and design. 2015: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunewardene MS, Subach FV, Gould TJ, Penoncello GP, Gudheti MV, Verkhusha VV, and Hess ST, Superresolution Imaging of Multiple Fluorescent Proteins with Highly Overlapping Emission Spectra in Living Cells. Biophys. J, 2011. 101(6): p. 1522–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lasker K, von Diezmann L, Zhou X, Ahrens DG, Mann TH, Moerner WE, and Shapiro L, Selective sequestration of signalling proteins in a membraneless organelle reinforces the spatial regulation of asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat Microbiol, 2020. 5(3): p. 418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gahlmann A, Ptacin JL, Grover G, Quinn S, von Diezmann ARS, Lee MK, Backlund MP, Shapiro L, Piestun R, and Moerner WE, Quantitative Multicolor Subdiffraction Imaging of Bacterial Protein Ultrastructures in Three Dimensions. Nano Letters, 2013. 13(3): p. 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman GR, Comolli LR, Gaietta GM, Fero M, Hong SH, Jones Y, Obayashi J, Downing KH, Ellisman MH, McAdams HH, and Shapiro L, Caulobacter PopZ forms a polar subdomain dictating sequential changes in pole composition and function. Mol. Microbiol, 2010. 76(1): p. 173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poindexter JS, Biological Properties and Classification of the Caulobacter Group. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 1964. 28(3): p. 231–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, and McIntosh JR, Computer Visualization of Three-Dimensional Image Data Using IMOD. Journal of structural biology, 1996. 116(1): p. 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.