Abstract

Background

Basal cell adenoma (BCA) and adenocarcinoma (BCAd) are two of the least frequent salivary gland tumors. We describe the largest series of these neoplasms, spanning over a period of 50 years (1970–2020), diagnosed and treated in a single Institution.

Methods

Sixty-eight cases were identified. Clinical and pathological data were collected and correlated with outcome.

Results

Forty-one BCA and 27 BCAd were identified. BCA cases had almost pristine prognosis, with only a relapse in a tumor inadequately excised. Ten patients with BCAd developed metastases, and 14 died from the disease. The 2-year and 5-year survival was of 76% and 42%.

Conclusions

The importance of adequate excision is reinforced in BCA, with no recurrences occurring when margins were negative. Contrary to previous reports, BCAd was not associated with a good prognosis. A better understanding of the genetics of these neoplasms may identify therapeutic options when dealing with inoperable or metastatic disease.

Keywords: Salivary gland, Basal cell adenoma, Basal cell adenocarcinoma, Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, Head and neck neoplasms, Otorhinolaryngologic neoplasms

Introduction

Salivary gland tumors encompass, according to the WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors, a variety of at least 36 different tumor subtypes [1]. Basal cell adenoma (BCA) and basal cell adenocarcinomas (BCAd), presenting a characteristic basaloid morphology, are two of the least frequent. They usually occur in elderly patients and the most common location is the parotid gland. Although the local recurrence rate could be as high as 24% for BCA and 50% for BCAd, the occurrence of regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on BCAd is rare, and disease-related deaths are seldom reported [2–4]. Furthermore, malignant transformation of BCA is also very uncommon [5, 6]. On the contrary, when BCAd occurs in the setting of the malignant component of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma, although very infrequently, it is associated with an ominous prognosis [7].

The genetic landscape of these tumors has been described in previous studies and includes alterations in the genes like CYLD, PIK3CA or CTNNB1 [8, 9]. Of particular importance is the CYLD gene, as it is implicated in the pathogenesis of the Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an inherited autosomal dominant disease characterized by the development of multiple adnexal cutaneous neoplasms along with these salivary gland neoplasms [10].

In this study we describe the clinico-pathological features of a series of these neoplasms, spanning over a period of 50 years, with long follow-up, diagnosed and treated in a single Institution, aiming at clarifying the prognosis and leading to appropriate clinical management of these patients. This is one of the largest series of cases reported so far. We also reviewed the literature, with focus in some the most recent genetic findings.

Materials and Methods

The archives of our Institution were searched, and 68 cases diagnosed between 1970 and 2020 as BCA, BCAd or BCAd in the context of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma were selected for this study by 2 pathologists. The diagnostic criteria for inclusion are the ones stated in the previously mentioned WHO book [1] and availability of archived histopathological slides and/or paraffin blocks. Morphological evaluation was sufficient for most of the cases. In selected ones immunohistochemical (mainly to highlight the characteristic dual cell population) and/or molecular studies (restricted to rule out adenoid cystic carcinoma by FISH analysis [see Discussion]) were performed to reach a diagnosis. No other immunohistochemical or molecular studies were deemed necessary, namely in the context of nasal cavity lesions that could be confused with undifferentiated or high-grade neoplasms.

The cases belonged to 65 patients—one patient had metachronous tumors, 3 other cases were recurrences from the same patient. Some cases from minor salivary glands were already discussed in a previous report [11].

For BCA, the pattern of growth and surgical margins status was recorded. For the malignant cases, assessment of surgical margins status and presence of perineural and lymphovascular invasion was evaluated. The pathological T and N stage were based on the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [12]. Clinical data (demographic, treatment, and follow-up information) were obtained from the patients’ charts. No follow-up data was available for 6 BCA and 2 malignant cases.

We used descriptive statistics for clinical and demographic characterization of the series, namely absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and, for quantitative variables, the mean and standard deviation or median, lower and upper quartiles in case of skewed distribution. We compared malignant with nonmalignant cases in what regards the time of evolution of disease prior to referral to our Institution using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test, and the size of the primary tumor using the Whelch two sample t-test. In the subgroup of malignant tumors, we evaluated the progression-free survival (PFS)–defined as the time between initial surgery and recurrence, metastasis or death from any cause–and overall survival (OS)–defined as the time from initial surgery to death from any cause. PFS and OS were calculated using Kaplan–Meier method. We evaluated the association between age, sex, pT, pN, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, primary tumor location and the clinical outcomes OS and PFS using the log-rank test. All tests were two-sided and we considered a significance level of 5%. When applicable we performed p-value adjustment for multiple comparisons using Hochberg method. All analyses were conducted in R (https://www.r-project.org/).

Five patients presenting with recurrent disease at the time of referral to our Institution (one patient with BCA and four with BCAd or BCAd in the context of pleomorphic adenoma) were excluded from the outcome evaluation and subgroup analyses. Two malignant cases were further excluded from the clinical outcomes analysis due to lack of follow up information, as previously mentioned.

Results

The clinical data from the cases identified is summarized in Table 1. Thirty-eight were BCA. We identified further 3 cases from the same patient, that presented in our Institution already as a recurrence due to an incomplete excision and had 2 recurrences during follow-up (these cases were not included in the table and, as previously stated, excluded from subgroup analysis). The remaining 27 were BCAd, either “de novo” or arising in a pleomorphic adenoma. From these, 4 cases were already recurrences at presentation at our Institution (and were also excluded from the outcome evaluation and subgroup analyses). Figure 1 illustrates the histological features of three of these cases.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical data

| Basal cell adenoma | Basal cell adenocarcinoma (BCAd) | BCAd arising from pleomorphic adenoma | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 38 | n = 22 | n = 5 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 62.4 years (15.0) | 62.7 years (10.0) | 62.5 years (22.9) |

| Gender | 21 female | 8 female | 1 female |

| 17 male | 14 male | 4 male | |

| Location | Parotid 37 | Parotid 10 | Parotid 3 |

| Minor 1 | Minor 7 | Minor 1 | |

| Other major 5 | Other major 1 | ||

| Mean size (SD) | 2.1 cm (0.6) | 3.7 cm (1.6) | 5.8 cm (1.9) † |

| Median time of evolution (Q1-Q3) | 12 months (7–84) | 12 months (6–24)‡ | |

| Median follow up (Q1-Q3) | 45.5 months (18.3–76.5) | 35 months (18–60.5) | |

| Follow up* | No relapses | 13 incomplete excision | 2 incomplete excision |

| 17 RT after surgery | 2 RT after surgery | ||

| 3 with local relapse‡ | No local relapse‡ | ||

| 8 with metastatic disease | 2 with metastatic disease | ||

| 12 death from disease | 2 death from disease | ||

SD Standard Deviation, Q1 First quartile 1, Q3 Third quartile

*No follow up data was available for 6 BCA and 2 malignant cases

†Largest dimension of the entire tumor

‡2 of the BCAd and 2 of the BCAd arising from PA were already recurrences at presentation at our Institution and are not included in the stats when indicated by this symbol (as previously mentioned, they were excluded from outcome evaluation and subgroup analyses, which the results are later detailed)

Fig. 1.

Hematoxylin and eosin images of three of the cases identified: A and B a basal cell adenoma, with the typical basaloid cytology and well-defined borders; C and D a basal cell adenocarcinoma, with an obvious infiltrative growth pattern, with nodules on desmoplastic stroma; and E and F a highly aggressive basal cell adenocarcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma with an invasive front that reached the dermis (E) and a residual hyalinized nodule of a pleomorphic adenoma within the tumor (F)

BCAs were almost entirely from the parotid gland (only one was from a minor salivary gland). The mean size of these tumors was 2.1 cm (SD 0.6 cm). The median time of evolution of disease, prior to referral, was 12 months (minimum 2 months, maximum 432 months). The majority of tumors (71%) had a mixture of growth patterns, with only the trabecular pattern having a considerable number as a single pattern (n = 8). No membranous type BCA were identified (i.e., with a predominance of the membranous pattern). During follow-up (mean 66.9 months; median 45.5 months), the only case with relapse belonged to a patient that already presented at our Institution with recurrent disease, following an inadequate excision at an outside Institution. Another patient, a 78-year-old man, presented with metachronous tumors, with BCA excised from both parotid glands within 1 and ½ year. This patient, as well as the remaining in this series, had no other tumors that suggested the presence of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

In the group of malignant tumors (n = 27), 5 cases arose in the context of pleomorphic adenoma (all of them extensively invasive), and none from transformation of BCA. Compared with BCA the distribution of the location was more even, with about half of the cases located in the parotid gland (n = 13), and the other half divided between minor salivary glands (n = 8) and other major non-parotid glands (n = 6). The median time of evolution of disease prior to referral to our center was similar to BCA, being 12 months in both cases (p = 0.473). Comparing the mean size of the tumors, the malignant ones were significantly bigger than BCA (mean 3.8 vs 2.1 cm, 95% CI for difference in means was − 2.8 to − 0.6 cm, p = 0.004).

Most malignant tumors (69%) were pT3 or pT4, and a substantial number of cases had lymph node metastases at presentation (6 out 10 with lymph node neck dissection). Lymphovascular and/or perineural invasion was identified in 12 cases. Treatment data showed that the number of incompletely excised tumors was considerable (n = 15). Radiation therapy (RT) was employed following surgery in the majority of the cases (19 out of 25), with only 7 having local recurrence. During follow up the number of cases with metastasis was 10, with 14 patients dying from the disease. The median PFS was 32 months and OS 43 months, with a 5-year PFS and OS of 40% and 42%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Progression-free survival and overall survival

| Progression-free survival | Overall survival | |

|---|---|---|

| 2-year (95% CI) | 56% (39–83%) | 76% (60–97%) |

| 5-year (95% CI) | 40% (23–70%) | 42% (24–73%) |

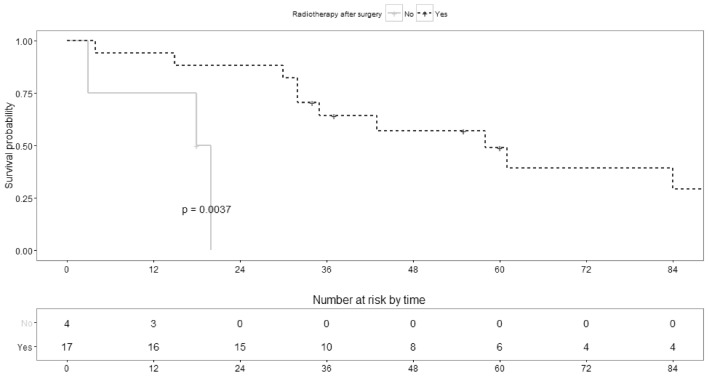

The variables that were significantly associated both with OS and PFS (Table 3) were the primary location of the tumor (Graph1), with the tumors located at nasal cavity having worse prognosis particularly comparing with the ones located at a major salivary gland, and the use of radiation therapy after surgery (Graph2). The quality of the excision (complete vs. incomplete) was also significantly associated with OS (Graph3). All data is shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Association between clinicopathological variables and progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

| PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2-yr PFS (95% CI) | p-value | 2-yr OS (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | |||||

| < 60 years | 7 | 57% (26–100%) | 0.895 | 86% (63–100%) | 0.516 |

| ≥ 60 years | 14 | 57% (36–90%) | 71% (51–100%) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 8 | 63% (37–100%) | 0.366 | 75% (50–100%) | 0.218 |

| Male | 13 | 52% (30–89%) | 76% (56–100%) | ||

| Location | |||||

| Major gland | 14 | 70% (49–100%) | < 0.0004* | 93% (80–100%) | 0.0144* |

| Other minor gland | 3 | 67% (30–100%) | 67% (30–100%) | ||

| Nasal cavity | 4 | 0%† | 25% (46–100%) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||||

| No | 7 | 57% (30–100%) | 0.402 | 71% (45–100%) | 0.503 |

| Yes | 7 | 57% (30–100%) | 86% (63–100%) | ||

| Perineural invasion | |||||

| No | 9 | 44% (21–92%) | 0.255 | 78% (55–100%) | 0.263 |

| Yes | 4 | 75% (43–100%) | 75% (43–100%) | ||

| Excision | |||||

| Complete | 4 | 75% (43–100%) | 0.065 | 100% (100–100%) | 0.0314 |

| Incomplete | 12 | 36% (17–80%) | 55% (32–94%) | ||

| pT | |||||

| T1-2 | 5 | 60% (29–100%) | 0.269 | 100% (100–100%) | 0.113 |

| T3-4 | 7 | 43% (18–100%) | 57% (30–100%) | ||

| pN | |||||

| N0 | 2 | 50% (13–100%) | 0.981 | 100% (100–100%) | 0.867 |

| N + | 5 | 80% (52–100%) | 100% (100–100%) | ||

| RT | |||||

| Yes | 17 | 65% (46–92%) | 0.035 | 88% (74–100%) | 0.0037 |

| No | 4 | 0%† | 0%† | ||

RT Radiation therapy after surgery

*Pairwise comparisons with Hochberg p-value adjustment—PFS: Nasal fossa vs Major, p = 0.0004; Nasal fossa vs Minor, p = 0.138; Major vs Minor, p = 0.796. OS: Nasal fossa vs Major, p = 0.024; Nasal fossa vs Minor, p = 0.138; Major vs Minor, p = 0.840

†All four patients had disease progression/recurrence or died within 24 months

Bold = statistically significant

Graph 1.

Survival probability along time (months) per primary location of the tumor (global p-value mentioned)

Graph 2.

Survival probability along time (months) per surgery plus radiation vs surgery alone (global p-value mentioned)

Graph 3.

Survival probability along time (months) per complete vs incomplete excision (global p-value mentioned)

Table 4.

Clinical-pathological data from Basal cell adenocarcinoma (BCAd) and BCAd arising from pleomorphic adenoma (BCAd ex-PA)

| Age | Gender | Location | Size (cm) | Excision | Diagnosis | Lymphovascular invasion | Perineural invasion |

pT | pN | RT | FU time (months) | Local relapse | Time to relapse | Metastasis | Time to metastasis | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | f | nasal cavity | 6,0 | NA | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | y | 43 | y | 7 | n | 43 | dod |

| 66 | m | other major | 5,0 | inc | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | 1 | y | 32 | n | 32 | n | 32 | ned |

| 57 | m | parotid | 2,5 | NA | BCAd | y | NA | NA | NA | y | 84 | n | 84 | y | 77 | dod |

| 63 | m | other minor | NA | inc | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | n | 20 | y | 9 | n | 20 | dod |

| 62 | f | nasal cavity | 4,0 | inc | BCAd | NA | NA | 4 | 0 | n | 3 | as presentation | 3 | n | 3 | dod |

| 71 | f | other minor | NA | NA | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | y | 58 | n | 58 | y | 47 | dod |

| 65 | f | other minor | 3,0 | NA | BCAd | NA | NA | 2 | 1 | y | 125 | n | 125 | n | 125 | ned |

| 52 | m | nasal cavity | 2,0 | inc | BCAd | n | n | 4 | NA | y | 4 | n | 4 | y | 4 | dod |

| 67 | m | parotid | 3,0 | inc | BCAd | n | y | 3 | 0 | y | 259 | as presentation | 259 | n | 259 | ned |

| 67 | f | nasal cavity | NA | inc | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | n | 18 | y | 14 | n | 18 | dod |

| 71 | m | other major | 2,0 | inc | BCAd | y | n | 1 | 1 | y | 35 | n | 35 | y | 18 | dod |

| 83 | m | parotid | 1,0 | inc | BCAd | n | n | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 68 | m | other major | 4,0 | inc | BCAd | n | n | 3 | 0 | y | 30 | n | 30 | y | 23 | dod |

| 60 | f | parotid | 6,0 | inc | BCAd | n | y | 3 | NA | y | 194 | n | 194 | n | 194 | ned |

| 66 | m | nasal cavity | 6,5 | inc | BCAd | n | y | 4 | NA | y | 15 | n | 15 | y | 6 | dod |

| 54 | f | parotid | 0,9 | com | BCAd | n | n | 1 | 2 | y | 121 | n | 121 | n | 121 | ned |

| 42 | m | parotid | 2,5 | com | BCAd | y | n | 2 | NA | y | 61 | n | 61 | y | 23 | dod |

| 72 | m | other major | 4,0 | inc | BCAd | y | n | 3 | 2 | y | 32 | n | 32 | y | 32 | dod |

| 35 | m | parotid | 3,0 | inc | BCAd ex-PA | n | n | 3 | 2 | n | 18 | as presentation | 18 | y | 4 | dod |

| 67 | m | parotid | 1,2 | com | BCAd | n | y | 1 | NA | y | 55 | n | 55 | n | 55 | ned |

| 63 | m | parotid | 7,0 | NA | BCAd ex-PA | y | n | 3 | 0 | y | 60 | n | 60 | n | 60 | ned |

| 47 | m | other minor | 6,0 | com | BCAd ex-PA | n | n | 4 | NA | y | 60 | as presentation | 60 | n | 60 | ned |

| 75 | m | other major | NA | NA | BCAd ex-PA | y | y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 49 | f | parotid | 4,0 | com | BCAd | y | y | NA | NA | y | 37 | n | 37 | n | 37 | ned |

| 75 | m | parotid | NA | inc | BCAd | n | n | NA | NA | y | 34 | n | 34 | n | 34 | ned |

| 59 | m | parotid | NA | NA | BCAd | NA | NA | NA | NA | n | 18 | n | 18 | n | 18 | ned |

| 93 | f | parotid | 7,0 | inc | BCAd ex-PA | y | n | 4 | NA | n | 3 | n | 3 | y | 0 | dod |

f female, m male, NA non available, inc incomplete, com complete, y yes, n no, RT Radiation Therapy after surgery, FU Follow-up, dod died of the disease, ned no evidence of disease

Discussion

This series reflects a 50-year experience of BCA and BCAd from a single Institution, a tertiary referral hospital for cancer treatment. The number of benign tumors outnumbers the malignant ones (~ 1.5:1). In this series, the epidemiology and location of BCA was similar to previous reports [1], with a mean age of 62 years, slight female predominance and with the majority of the tumors occurring in the parotid gland. In one patient metachronous bilateral parotid BCA occurred, without coexisting other tumors or features suggesting Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This is a very rare event (the description of multiple salivary gland tumors is almost restricted to Warthin’s tumor), although previously reported [13, 14]. Most tumors (71%) had a mixture of the typical reported growth patterns (solid, trabecular, tubular), with only the trabecular pattern having a considerable number as a single pattern (n = 8). Complete excision (negative surgical margins) was achieved in all the tumors primarily treated at our Institution, with no recurrences recorded. Recurrence only occurred in a patient that had already presented at our institution as a relapse. In the recurrence surgery multiple small nodules were found scattered at the previous surgery site, a somewhat similar pattern to what it is found when pleomorphic adenomas are inadequately excised and recurs [15], and negative margins could not be achieved even after repeated surgery. This fact emphasizes the importance of an adequate primary excision to clinically control benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. Furthermore, in the perspective of better managing resources at a highly differentiated tertiary center, these results may suggest that the post-treatment follow-up of patients with complete resections may be transferred to the local caregiver after a lower period of time due to low risk of recurrence (the median follow up of these patients at our institution was 3.8 years, with 25% of the patients having more than 6.4 years of follow up).

BCAd are very rare tumors, but the number in our series is quite considerable, probably related to the fact that our Institution is a referral center for southern Portugal for treatment of these neoplasms. The mean age of the patients (62.6 years) was similar to other series, although we had a strong male predominance (2:1) contrary of previous reports that mention gender balance [1, 16]. Most of the tumors occurred in the parotid gland, but the number in minor salivary gland and other major salivary glands was substantial. We did not identify BCAd arising from BCA, a phenomenon reported by others [2]. Comparing with BCA, these malignant tumors were statistically significantly larger (p = 0.004), with a similar median time of evolution of disease prior to referral (12 months for both), reflecting a faster growth of these neoplasm. The majority were pT3-4, which may justify the number of inadequately excised tumors (71%). RT was used as adjuvant therapy in most cases, and that probably explains the lower number of local recurrences (17%) despite the quality of excision—the finding that the use of RT after surgery can reduce the incidence of local recurrence, even with positive surgical margins, has been previously reported [17]. Nevertheless, despite this local control, the number of metastases and deaths related to the disease were considerable. Contrary to previous reports and series that describe a generally good prognosis and a low number of deaths [1, 2, 16, 18], in our series the deaths related to the disease were substantial, with a median PFS of 32 months and a median OS of 43 months, and a 5-year OS of 42%. This percentage is lower than the reported in the largest series of these neoplasm reported till this date (a population-level study based on the data of the National Cancer Database), that mentions an overall survival at 5 and 10 years of 79% and 62% respectively [3]. Five patients with BCAd arising in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma had the usual ominous prognosis [7]; in this group, 2 patients died of the disease (50%; one patient with no available information). Even when BCAd appeared “de novo” the percentage of deaths related to the disease was considerable (58%). Our series alert that the perception of BCAd being a low-grade malignancy cannot be always true and an aggressive behavior may not be that rare. Further series should clarify this finding.

The variables that were significantly associated both with OS and PFS were the primary location of the tumor (nasal cavity tumors had worse prognosis compared with major salivary glands and other minor salivary gland locations) and the use of radiation therapy after surgery. The quality of the excision (complete vs. incomplete) was also significantly associated with OS. No other variables had significant effect of OS and PFS, including some of the ones routinely mentioned in pathology report of the surgical specimen. This questions if other findings could be employed to better understand the behavior of the tumor. Nevertheless, the number of non-available data for certain variables is possibly non-negligible (e.g. pT staging n = 11, lymphovascular n = 8 or perineural invasion n = 9, as shown in Table 4), perhaps limiting this specific analysis. The previously mentioned series [3] reported, similarly to our findings, that worse survival was significantly associated with positive margins and a significant survival benefit was found when radiation was used after surgery (vs. surgery alone). According to their data, older age (≥ 65 years old) and high T-stage (T3-T4) was also significantly associated with worse survival, a conclusion we could not back.

From a pathological diagnostic perspective, the differential diagnosis between BCA and BCAd essentially rests in the finding of an invasive growth pattern, usually determined on the evaluation of the gross specimen plus the microscopic hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) analysis. Concerning other neoplasms, the main differentials are the bidifferentiated salivary tumors with basaloid cytology: adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma and cellular pleomorphic adenoma (PA). In certain circumstances, basaloid squamous cell carcinoma or cutaneous basal cell carcinoma with deep invasion can also enter in the differential diagnosis. Usually, morphologic clues on H&E are sufficient to separate these neoplasms. Some immunohistochemical studies, such as beta-catenin or LEF-1, may be helpful when confronting with other salivary tumors: nuclear β-catenin is expressed in BCA/BCAd and could be helpful in the differential with the other salivary gland neoplasms but may be unable to distinguish BCA from BCAd—although nuclear expression is usually found in higher percentage on BCA (range 82%–100%), several studies also report frequent expression in BCAd (range 33%–100%); co-expression of LEF-1 in BCA/BCAd was also noted in a previous report although used in isolation was also identified in PA. In what concerns molecular analysis, on routine practice FISH can be used for the differential with ACC, as this neoplasm is frequently associated with the t(6;9) or t(8;9) translocations, resulting in MYB-NFIB and MYBL1-NFIB fusions [1, 16, 19–25].

The higher than expected bad prognosis of the malignant cases reinforces the need of developing more therapeutic options. The standard of care in salivary malignancies is adequate excision, followed by RT in selected cases. When the disease is inoperable or metastatic the options are very limited. The level of evidence to recommend the use of systemic chemotherapy is low [26], reflecting the inexistence of appropriate drugs or large studies to support its use (usually only anecdotal reports can be found). The use of targeted therapy has been slowly introduced in the last years, with some benefiting of it: selected cases of Androgen Receptor-positive or Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-positive salivary gland cancer (mainly salivary duct carcinoma, either “de novo” or arising in the setting of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma); cancers harboring NTRK gene fusion (basically restricted to the secretory carcinoma); and although with a low quality of evidence, in patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma who are candidates for initiation systemic therapy, a multitargeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, such as lenvatinib or sorafenib, may be offered, the same happening with checkpoint inhibitors in patients with high Tumor Mutation Burden or Microsatellite Instability-High [26, 27]. Specifically for BCAd no targeted therapy has been approved or recommended, limiting the options in advanced disease. Nevertheless, the genetic knowledge of this tumor has improved, with the hope that it can evolve to them. Two 2016 studies found activating mutations in the PIK3CA gene in some BCAd [9, 22]. This gene is mutated in high frequency in many cancers, with therapeutic targets along the PIK3CA pathway under research [28] and with a drug already approved by the FDA for the treatment of PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer [29]. In 2018 a study identified mutations in the CYLD gene both in BCA and BCAd [8]. The evidence of an association between CYLD somatic mutations and dysregulated tropomyosin kinase (TRK) signalling, along with the reduced colony formation and proliferation when cell cultures established from CYLD mutant tumors were treated with the TRK inhibitor lestaurtinib, suggest that TRK inhibition could be used as a strategy to treat tumors with loss of functional CYLD [30]. In what concerns CTNNB1 gene activating mutations, this occurrence is frequently found in BCA (along with beta-catenin nuclear immunoexpression), but in BCAd is rarely found, limiting its importance from a therapeutic point of view although it can be diagnostically useful [9, 21–24].

The main limitation of this study is the small number of cases in each group, but this is related to the topic itself, as it is a group of very rare neoplasms. Additionally, some cases do not have data available for all the variables analyzed (we have two cases lost to follow-up and five patients presented with recurrent disease at the time of referral and were excluded from the clinical outcomes and subgroup analysis). Further series should be added to this one in order to clarify the findings described.

To conclude, the description of this series further increases clinical data related to these rare cancer types. It reinforces the importance of an adequate primary excision, showing that no recurrences occurred when negative margins were achieved. Contrarily to previous reports, BCAd was not associated with a relatively good prognosis, as the number of reported deaths was substantial. Increase in the genetic knowledge of this tumor may open the possibility of target therapy when dealing with inoperable or metastatic disease.

Author Contributions

MR and IF: Contributed to the study conception and design, reviewed the pathological slides and agreed on the diagnosis. MR: performed the data collection, data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Susana Esteves did the statistical analysis. Isabel Fonseca and Susana Esteves reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional board of Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa Francisco Gentil (Lisboa, Portugal), project number UIC/993.

Research Involving Human and Animals Rights

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours [Internet; beta version ahead of print] [Internet]. (2022) 5th ed. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chapters/52. Accessed 10 July 2022

- 2.Muller S, Barnes L. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands: report of seven cases and review of the literature. Cancer Interdiscip Int J Am Cancer Soc. 1996;78:2471–2477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhan KY, Lentsch EJ. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the major salivary glands: a population-level study of 509 cases. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:1086–1090. doi: 10.1002/lary.25713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luna MA, Batsakis JG, El-Naggar AK. Basaloid monomorphic adenomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:687–690. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen KT. Carcinoma arising in monomorphic adenoma of the salivary gland. Am J Otolaryngol. 1985;6:39–41. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(85)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luna MA, Batsakis JG, Tortoledo ME, Del Junco GW. Carcinomas ex monomorphic adenoma of salivary glands. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:756–759. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100109995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rito M, Fonseca I. Carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands has a high risk of progression when the tumor invades more than 2.5 mm beyond the capsule of the residual pleomorphic adenoma. Virchows Arch. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rito M, Mitani Y, Bell D, Mariano FV, Almalki ST, Pytynia KB, et al. Frequent and differential mutations of the CYLD gene in basal cell salivary neoplasms: linkage to tumor development and progression. Mod Pathol. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson TC, Ma D, Tilak A, Tesdahl B, Robinson RA. Next-generation sequencing in salivary gland basal cell adenocarcinoma and basal cell adenoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:494–500. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0730-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonseca I, Soares J. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of minor salivary and seromucous glands of the head and neck region. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1996;13(2):128–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, et al. (Eds.). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th edition). Springer International Publishing: American Joint Commission on Cancer. 2017.

- 13.Junquera L, Gallego L, de Vicente JC, Fresno MF. Bilateral parotid basal cell adenoma: an unusual case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ethunandan M, Pratt CA, Morrison A, Anand R, Macpherson DW, Wilson AW. Multiple synchronous and metachronous neoplasms of the parotid gland: the Chichester experience. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myssiorek D, Ruah CB, Hybels RL. Recurrent pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 1990;12:332–336. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson RA. Basal cell adenoma and basal cell adenocarcinoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2021;14:25–42. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shingaki S, Ohtake K, Nomura T, Nakajima T. The role of radiotherapy in the management of salivary gland carcinomas. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 1992;20:220–224. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagao T, Sugano I, Ishida Y, Hasegawa M, Matsuzaki O, Konno A, et al. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands: comparison with basal cell adenoma through assessment of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and expression of p53 and bcl-2. Cancer Interdiscip Int J Am Cancer Soc. 1998;82:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitt AC, Griffith CC, Cohen C, Siddiqui MT. LEF-1: diagnostic utility in distinguishing basaloid neoplasms of the salivary gland. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:1078–1083. doi: 10.1002/dc.23820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilodeau EA, Acquafondata M, Barnes EL, Seethala RR. A comparative analysis of LEF-1 in odontogenic and salivary tumors. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawahara A, Harada H, Abe H, Yamaguchi T, Taira T, Nakashima K, et al. Nuclear β-catenin expression in basal cell adenomas of salivary gland. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jo VY, Sholl LM, Krane JF. Distinctive patterns of CTNNB1 (β-catenin) alterations in salivary gland basal cell adenoma and basal cell adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1143–1150. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y-H, Huang W-C, Hsieh M-S. CTNNB1 mutations in basal cell adenoma of the salivary gland. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato M, Yamamoto H, Hatanaka Y, Nishijima T, Jiromaru R, Yasumatsu R, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signal alteration and its diagnostic utility in basal cell adenoma and histologically similar tumors of the salivary gland. Pathol Pract. 2018;214:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung MJ, Roh J-L, Choi S-H, Nam SY, Kim SY, Lee S, et al. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland: a morphological and immunohistochemical comparison with basal cell adenoma with and without capsular invasion. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geiger JL, Ismaila N, Beadle B, Caudell JJ, Chau N, Deschler D, et al. Management of salivary gland malignancy: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2021) NCCN Guidelines Head and Neck [Internet]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2022

- 28.Gustin JP, Cosgrove DP, Park BH. The PIK3CA gene as a mutated target for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:733–740. doi: 10.2174/156800908786733504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA (2019) FDA approves alpelisib for metastatic breast cancer [Internet]. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-alpelisib-metastatic-breast-cancer. Accessed 10 July 2022

- 30.Rajan N, Elliott R, Clewes O, Mackay A, Reis-Filho JS, Burn J, et al. Dysregulated TRK signalling is a therapeutic target in CYLD defective tumours. Oncogene Nature Publishing Group. 2011;30:4243–4260. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.