Abstract

Background

Metastases account for 6–25% of parotid tumors, often presenting dilemmas in their diagnosis.

Methods

Parotid metastases diagnosed on histology/cytology were retrieved. MUC2, MUC5AC, androgen receptor immunohistochemistry was performed in select cases.

Results

Fifty-one samples were identified from 42 patients, including 14 aspirates, 7 biopsies and 30 parotidectomies. Previous history was available in 17 cases, 13 parotidectomies accompanied excision of the primary, and relevant clinical data was unavailable for 12 patients. Majority (81%) had head and neck primaries; eye and ocular adnexa were the commonest subsite (52.4%), and sebaceous carcinoma the commonest histology (33%). When history was unavailable, most metastases were initially diagnosed as poorly differentiated carcinoma/malignant tumor, or mucoepidermoid carcinoma on cytology.

Conclusions

Intraparotid metastases encompass a wide spectrum, often mimicking primary salivary gland neoplasms, particularly on limited samples. Metastases should be considered when histological/cytological features are unusual; detailed clinical information and ancillary techniques aid in arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

Keywords: Parotid, Salivary gland, Metastasis, Secondary tumor, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

The parotid is the only salivary gland with intraparenchymal and periglandular lymph nodes, owing to its late encapsulation during embryogenesis [1]. These lymph nodes, up to 15 to 20 in number, serve as the first echelon nodes draining various locations in the head and neck region, including the skin over the root of the nose, eyelids, frontotemporal scalp, the anterior part of ear, external auditory canal, tympanic membrane and cavity, posterior part and floor of the nasal cavity, parts of palate and nasopharynx, and the conjunctiva and lacrimal gland [2]. Due to this, apart from primary salivary gland neoplasms, the parotid is also a site for metastases from various tumors in the head and neck region, with metastases being 20 times more frequent than in the other major salivary glands. Rarely, distant tumors can also metastasize to the parotid gland. Metastases have been found to account for approximately 6–25% of all parotid malignancies in most populations [3, 4]. However, in sun-exposed regions of Australia with high risk of skin cancers, this proportion can be as high as 60% [3, 4]. Consequent to their rarity as compared to primary tumors, there is a lack of awareness about the occurrence of metastatic tumors in the parotid, particularly among general pathologists with scarce exposure to salivary gland pathology. Due to its superficial location, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the cornerstone pre-operative investigation for the diagnosis of parotid masses, and in the absence of relevant clinical history, the possibility of a metastatic tumor is often overlooked on aspirates. Also, the morphology of several metastatic tumors closely resembles that of primary parotid tumors [4, 5]. Thus, metastases to the parotid pose a considerable diagnostic challenge, especially when clinical history is unavailable and the primary site is unknown.

There are only occasional studies in literature on the incidence and patterns of metastasis to the parotid gland [3, 4, 6–11]. We recently encountered two unusual cases of metastases to the parotid, the first a case of metastatic ocular medulloepithelioma which had presented a diagnostic conundrum on FNAC as the relevant clinical history was not provided up front [12], and the second being a case of delayed metastasis from eyelid endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) in which the primary tumor had not been diagnosed as EMPSGC [13]. The challenges presented in the diagnosis of these two cases prompted us to conduct this study to identify metastases to the parotid, review their clinicopathological features, highlight the complexities involved in their diagnosis, and to emphasize the utility of ancillary tests in their recognition.

Materials and Methods

All cases diagnosed as metastases to the parotid gland on cytology and/ or histology between 2010 and 2020 were retrieved from our departmental archives using the search terms “parotid”, “salivary gland” and “metastasis”, including FNACs, core biopsies and parotidectomies, and their slides were reviewed. Relevant clinical data, past medical history, radiological findings, and additional histological details indicative of a primary site were collected from archival records. The synchronous or metachronous nature of the metastases was ascertained. Cytology and histology slides from the same patient were analyzed in tandem for assessment of potential pitfalls in cytological evaluation. Cases of infiltration of the parotid by local extension from a primary tumor of the head and neck region were excluded from the study. Immunohistochemistry was performed on whole tissue sections to support the diagnosis in select cases, using primary antibodies against androgen receptor (AR) (clone SP107, Invitrogen, dilution 1:200), MUC2 (clone M53, Thermo Fisher Scientific, prediluted), and MUC5AC (clone 45M1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, prediluted), as described previously [14].

Results

A total of 55 samples from 46 patients were identified from our records as metastases to the parotid gland. On review of histological and cytological features, four cases were excluded (Table 1): three owing to revision of the diagnosis to a primary salivary gland tumor, and one tumor with local infiltration into the parotid rather than metastasis. The remaining 51 samples from 42 patients were studied further. Thirty-four patients (80.9%) had one specimen, 7 (16.7%) had two, and 1 (2.4%) had three samples. The 51 samples were comprised of 14 FNACs, 7 core biopsies, and 30 parotidectomies. Of the latter, 13 were part of a composite specimen i.e. excision of the primary tumor accompanied by parotidectomy and lymph node dissection. Relevant previous history of the primary malignancy was available for 17 patients, and the primary was evident in 13 composite specimens. The previous history or precise diagnosis was initially not available for 12 patients (8 FNACs, 2 core biopsies, 2 parotidectomies), and was subsequently obtained for 7 of these patients.

Table 1.

Cases with revision of diagnosis and exclusion from cohort of parotid metastases

| Sl. No | Original diagnosis | Revised diagnosis after review | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FNAC: metastatic SCC from known lung primary | FNAC: pleomorphic adenoma with squamous metaplasia | Bias due to a known extra-parotid primary malignancy; metaplastic changes in primary parotid tumor can mimic malignancy |

| 2 | Biopsy: metastatic SCC | Parotidectomy: salivary duct carcinoma; androgen receptor positive on review | Primary parotid malignancy morphologically mimicking a metastatic carcinoma |

| 3 |

a) Parotid FNAC: Metastatic PDCA b) Wide excision of gingivobuccal sulcus with parotidectomy: SCC with parotid metastases |

Wide excision of gingivobuccal sulcus tumor: SCC Parotidectomy: synchronous salivary duct carcinoma, confirmed by positive androgen receptor and negative p40 on review |

Bias due to a known extra-parotid primary malignancy. Meticulous histological examination aided by immunohistochemistry helped in accurate diagnosis |

| 4 | Parotidectomy (referral case): metastatic ameloblastic fibrosarcoma | Parotidectomy reviewed after obtaining detailed history: local infiltration by ameloblastic fibrosarcoma of mandible | Local infiltration by adjacent primary tumor misinterpreted as metastasis |

FNAC fine needle aspiration cytology, PDCA poorly differentiated carcinoma, SCC squamous cell carcinoma

The 42 patients included 29 men (69%) and 13 women (31%), with a mean age of 54.5 years (range: 3 to 82 years; median: 58 years). The sites of primary malignancy were most frequently located in the head and neck region (n = 34; 80.9%) with 7 (16.7%) in head and neck mucosal locations, 22 (52.4%) in the eye and ocular adnexa, and 5 (11.9%) in head and neck cutaneous sites (Table 2). Sebaceous carcinoma (n = 14; 33.3%), melanoma (n = 7; 16.7%) and squamous cell carcinoma (n = 7; 16.7%) were the most common histomorphological types of head and neck primaries (Table 2, Fig. 1). Uncommon metastases from the head and neck region included olfactory neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, ocular medulloepithelioma (Fig. 2 A,B), EMPSGC, adenocarcinoma NOS of eyelid, and SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma, each with a single case (2.4%). There were four cases of metastases from distant sites, two (4.8%) lung adenocarcinomas (Fig. 2C-F), one renal cell carcinoma (2.4%), and one from the central nervous system (2.4%) i.e. glioblastoma (Fig. 2G-H). Lastly, there were four cases of squamous cell carcinoma in which the primary site remained unknown (Fig. 2I-L), and were treated as carcinoma of unknown primary site (9.5%). In 18 cases (42.9%), the metastases were synchronous with the primary tumor, while they were metachronous in 20 cases (47.6%). Interestingly, in one case, the patient presented with a parotid swelling eight months before a primary was detected in the lung.

Table 2.

Primary site and histological diagnosis of malignancies metastatic to parotid gland

| Primary site and histological diagnosis | Number of cases | Initially unknown primaries | Type of specimen without relevant clinical data | Initial diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck region | 34 | 5 | ||

| Eye and ocular adnexa | 22 | 2 | ||

| Sebaceous carcinoma | 14 | 0 | ||

| Melanoma (3 ocular, 1 eyelid) | 4 | 0 | ||

| Retinoblastoma | 1 | 0 | ||

| Ocular medulloepithelioma | 1 | 1 | FNAC | PDMT |

| EMPSGC eyelid | 1 | 1 | FNAC | Primary SGC |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS eyelid | 1 | 0 | ||

| Head and neck mucosal sites | 7 | 3 | ||

| Mucosal squamous cell carcinoma (2 larynx, 2 oropharynx, 1 nasopharynx) | 5 | 3 | FNAC |

2 MEC vs SCC 1 SCC |

| Olfactory neuroblastoma | 1 | 0 | ||

| SMARCB1 deficient sinonasal carcinoma | 1 | 0 | ||

| Head and neck cutaneous sites | 5 | 0 | ||

| Cutaneous melanoma (2 scalp, 1 neck) | 3 | 0 | ||

| Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (scalp) | 2 | 0 | ||

| Metastases from distant locations | 4 | 3 | ||

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 2 | 2 |

1 FNAC 1 core biopsy |

PDCA AdCa NOS |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 | 1 | Core biopsy | PDCA |

| Glioblastoma, NOS | 1 | 0 | ||

| Metastases with unknown primary site | 4 | 4 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 | 4 |

AdCa NOS adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified; EMPSGC endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma; FNAC fine needle aspiration cytology; MEC mucoepidermoid carcinoma; PDCA poorly differentiated carcinoma; PDMT poorly differentiated malignant tumor; SCC squamous cell carcinoma; SGC salivary gland carcinoma

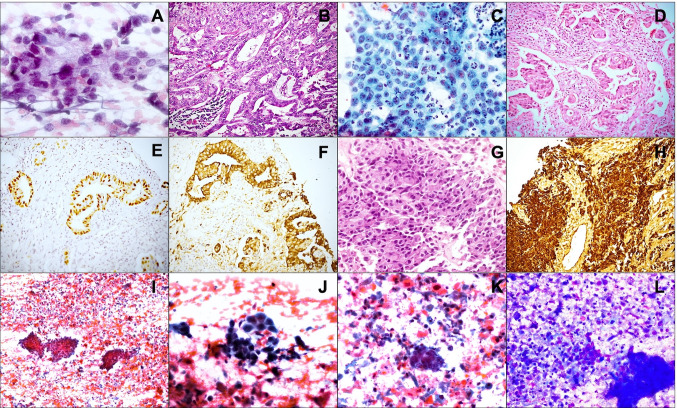

Fig. 1.

Metastases to parotid: Aspirate showing a poorly differentiated carcinoma (A PAP; B MGG) which on review showed cytoplasmic vacuoles indenting the nucleus (C MGG); parotidectomy showed a sebaceous carcinoma with comedonecrosis (D HE) cells with similar cytoplasmic vacuoles (E HE) and androgen receptor positivity (F IHC). Aspirate (G PAP; H MGG) and parotidectomy (I HE) showing a metastatic melanoma from a scalp primary. Aspirate reported as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma vs. mucoepidermoid carcinoma (J PAP; K MGG); prior biopsy from larynx showing squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 2.

Metastases to parotid: Aspirate showing small round cells in a fibrillary matrix, diagnosed as a poorly differentiated malignant tumor (A PAP); parotidectomy showing metastatic medulloepithelioma (B HE). Aspirate diagnosed as poorly differentiated carcinoma (C PAP) and corresponding biopsy showing adenocarcinoma (D HE) later found to be positive for TTF-1 (E, HE) and napsin (F, HE). Biopsy from a metastatic glioblastoma with large polygonal cells resembling salivary duct carcinoma (G HE), but immunopositive for GFAP (H IHC). Aspirate from a squamous cell carcinoma with unknown primary showing cohesive fragments of tumor cells in a necrotic background (I PAP); cells have hyperchromatic nuclei (J PAP) and keratinized cytoplasm (K PAP; L MGG)

The cases that underwent FNAC and core biopsy are summarized in Table 3. On review of the FNAs, six of the 14 aspirates (42.9%) were accompanied by details of the primary tumor up front, and were diagnosed accurately. In the eight aspirates where such details were unavailable, the initial diagnoses were high grade MEC vs poorly differentiated SCC in three cases, poorly differentiated carcinoma (PDCA) in two cases, and poorly differentiated malignant tumor (PDMT), myoepithelial carcinoma vs secretory carcinoma, and SCC in one case each. All three FNAs in which differential diagnoses of poorly differentiated SCC and high grade MEC was given were later proven to be metastatic SCC. Similarly, of the seven core biopsies, five biopsies where previous history was available were accurately diagnosed, and one parotid biopsy was accompanied by a biopsy from larynx which showed an SCC establishing a primary. One case of metastatic renal cell carcinoma was accompanied by biopsies from cervical lymph node and bone marrow, which also showed metastases. One biopsy was reported as adenocarcinoma NOS, was later detected to have a lung mass, and napsin immunohistochemistry performed on the parotid biopsy supported a diagnosis of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma.

Table 3.

Diagnosis on FNAC and core biopsy compared with final diagnosis

| Sl. no | Clinical data provided | Diagnosis on FNAC/core biopsy | Final histopathology diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parotid FNAC | |||

| 1 | Known case of ONB | Small round cell tumor positive for synaptophysin, compatible with ONB | Parotidectomy: metastatic ONB |

| 2 | Known case of eyelid sebaceous carcinoma | PDCA suspicious for metastatic sebaceous carcinoma | Parotidectomy: metastatic sebaceous carcinoma |

| 3 | Known case of scalp melanoma | Metastatic melanoma | NA |

| 4 | Known case of oropharyngeal SCC | Metastatic SCC | NA |

| 5 | Known case of retinoblastoma | Metastatic retinoblastoma | NA |

| 6 | Known case of conjunctival melanoma | Metastatic melanoma | NA |

| 7 | No | Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma | Nasopharynx biopsy: non-keratinizing undifferentiated SCC, p40 positive |

| 8 | No |

FNAC: PDCA Biopsy: AdCa with ductal differentiation |

History of lung mass provided later; review of parotid biopsy*: TTF-1 and napsin positive lung AdCa |

| 9 | No | PDSCC vs mucoepidermoid carcinoma, high grade | Parotidectomy accompanied by history of supraglottic SCC: metastatic SCC; negative for MUC2, MUC5AC on review |

| 10 | No | Poorly differentiated malignant tumor | History of primary ocular tumor obtained from clinical team when biopsy was done; Parotid biopsy*, parotidectomy: metastatic ocular ME |

| 11 | No | PDSCC vs mucoepidermoid carcinoma, high grade | History of primary in base of tongue obtained from clinical team when biopsy was done; Parotid biopsy: metastatic NKSCC |

| 12 | No | PDSCC vs mucoepidermoid carcinoma, high grade | Parotidectomy: metastatic SCC-CUPS; MUC2, MUC5AC performed on review were negative |

| 13 | No | FNAC: Primary SGC, either myoepithelial carcinoma or secretory carcinoma | History of eyelid carcinoma 11 years prior provided at the time of parotidectomy; Review of eyelid primary: EMPSGC; Parotidectomy: Metastatic EMPSGC |

| 14 | No | PDCA | Parotidectomy: SCC—CUPS, positive for p40, negative for AR, MUC2 and MUC5AC |

| Parotid core biopsy* | |||

| 1 | Case of carcinoma larynx | Parotid biopsy: metastatic SCC | Larynx biopsy accompanying parotid biopsy showed SCC |

| 2 | Known case of NKSCC base of tongue | Parotid biopsy: metastatic SCC | NA |

| 3 | Known case of glioblastoma | Parotid biopsy: metastatic glioblastoma | NA |

| 4 | No | Parotid biopsy: AdCa NOS favored over AdCC; CEA, CK7 positive; AR, CK20, CD117, TTF-1 negative | Lung mass biopsy performed 8 months later showed AdCa. Parotid biopsy review: Napsin positive metastatic lung AdCa |

| 5 | No | Parotid biopsy: PDCA, positive for CK, PAX8, EMA (focal), negative for CK7, CK20, GATA3, TTF-1, possibly metastatic RCC | Biopsy review showed cells with clear to vacuolated cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, compatible with metastatic RCC |

*Details of two biopsies are provided with corresponding FNACs

AdCa adenocarcinoma, AdCC adenoid cystic carcinoma, AR androgen receptor, CUPS carcinoma of unknown primary site, EMPSGC endocrine mucin producing sweat gland carcinoma, FNAC fine needle aspiration cytology, ME medulloepithelioma, NA not available, NKSCC non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, NOS not otherwise specified, PDCA poorly differentiated carcinoma; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma

On histopathological examination of the parotidectomy specimens, 18 of the 30 parotidectomies (60%) had tumor deposits in intraparotid lymph nodes only, eight (26.7%) had both intraparotid lymph node as well as parenchymal deposits, while four (13.3%) had parenchymal involvement only. Twenty of the 30 parotidectomies had an accompanying cervical lymph node dissection, and 14 of these (70%) showed metastases to cervical lymph nodes.

As the differential diagnosis in 10 cases was between MEC and SCC, we performed immunohistochemistry for MUC2 and MUC5AC in eight cases where tissue blocks were available. None of these revealed immunopositivity for either stain, supporting the diagnosis of metastatic SCC. AR immunostaining helped to identify and exclude two cases of primary salivary duct carcinoma which had been initially diagnosed as metastatic SCC, and to confirm the diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma in five cases in which it had not been performed at the time of reporting due to non-availability of the antibody.

Discussion

Parotid tumors account for 80% of all salivary gland neoplasms and 3% of head and neck tumors. Majority of these represent primary parotid neoplasms, with metastases being rather uncommon [3, 4, 15]. The available literature on metastases to parotid is restricted to case reports and small case series [3, 4, 6–13, 16, 17], with most previous articles on parotid metastases describing their presentation, management and clinical behavior. We report our experience from a high volume tertiary care centre, with a focus on histological and cytological diagnosis, and the potential challenges leading to misdiagnosis.

Metastases to the parotid may occur by lymphatic spread via the retropharyngeal nodes, or by hematogenous dissemination; supraclavicular primaries metastasize primarily through the lymphatics, whereas infraclavicular tumors are considered to metastasize through the hematogenous route [7]. Most metastatic tumors have primaries in the head and neck region [6, 7, 9–11, 16, 17], while those from distant sites account for approximately 10–20% of all parotid metastases [7]. Seifert et al. postulated that metastasis to intraparotid lymph nodes suggests lymphatic spread, while parenchymal metastasis indicates a hematogenous route of spread [9]. In oncological terms, however, no distinction is made between intraparotid lymph nodal or parotid parenchymal metastases, and management remains the same [9]. In our study, metastases involved only the intraparotid lymph nodes in most cases (60%), and a smaller proportion (26.7%) showed metastases extending from intraparotid nodes into the parenchyma, thus supporting the theory of lymphatic dissemination of supraclavicular primaries. Such an observation could not be made for infraclavicular tumors as only biopsies were available. Conversely, selective parenchymal involvement was seen only in four parotidectomy specimens (13.3%); however, the possibility of these being nodal metastasis overgrowing the lymph node and spilling into the parenchyma cannot be excluded.

While previous reports (Table 4) describe cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma as the most common tumors to metastasize to the parotid [17], we found that sebaceous carcinoma was the most common histological tumor type in our study, followed by melanoma and mucosal SCC. This variance can be attributed to an overall low incidence of cutaneous SCC in our country, due to the high skin pigmentation prevalent here [18]. Kashiwagi et al. reported similar findings in the Japanese population, with maximum metastases being from sebaceous carcinoma and mucosal SCC [16]. In the context of distant metastases, the lung appears to be the most common primary site, with others including kidney and breast [3, 6, 7, 9, 11]. The frequency of metastases from distant sites was, however, lower in our study as compared to others [3, 6, 7, 9–11], with the caveat that many of these possibly remain undiagnosed, being labeled as primary parotid adenocarcinoma NOS, particularly on FNAC. Rare tumors with metastasis to parotid in this study included olfactory neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, ocular medulloepithelioma, EMPSGC, adenocarcinoma NOS of eye, glioblastoma, lung adenocarcinoma, and SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma, all which have been described previously in rare reports, except for SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient sinonasal carcinoma, of which this appears to be the first reported case [12, 13, 19–26]. The accurate diagnosis of these rare histological types in parotid aspirates and biopsies was only possible when adequate clinical information on the primary malignancy was available.

Table 4.

Primary site and histological types of metastases to parotid described in literature

| Author, year | No. of cases | Head and neck (HN) primaries | Common histological types of HN primaries | Primary sites other than HN | Common histological types of primaries other than HN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seifert et al.; 1986 | 75 | 49 | 23 SCC, 15 melanomas | 11 | 5 bronchial, 4 RCC |

| Malata et al.; 1998 | 20 | 17 | 9 SCC, 7 melanomas | 3 | 2 RCC, 1 lung SCC |

| Bron et al.; 2003 | 178 | 101 SCC, 69 melanomas: primary site not specified | |||

| Nuyens et al.; 2006 | 34 | 31 | 23 cutaneous SCC, 7 melanomas | 3 | 2 breast carcinomas, 1 extremity RMS |

| Franzen et al.; 2015 | 39 | 34 | 26 cutaneous SCC | 5 | 2 SmCC, 1 SCC of lung |

| Kashiwagi et al.; 2016 | 14 | 14 | 4 AEDT SCC, 4 eyelid sebaceous carcinoma | - | - |

| Pastore et al.; 2017 | 66 | 56 | 32 cutaneous SCC, 13 cutaneous melanomas | 7 | 1 NEC, 2 SCC, 2 SmCC of lung |

| Emanuelli et al.; 2018 | 11 | - | - | 11 | 2 SmCC, 2 AdCa, 2 NEC, 2 SCC of lung |

| Mayer et al.; 2021 | 117 | - | *58 cutaneous SCC, 10 melanomas, 6 CUPS, 5 mucosal SCC | 4 | 2 breast, 2 RCC |

| Present study | 42 | 34 | 14 sebaceous carcinoma, 7 SCC, 7 melanomas | 4 | 2 lung AdCa, 1 RCC, 1 GBM |

AdCa adenocarcinoma, AEDT aerodigestive tract, GBM glioblastoma, HN head and neck, NEC neuroendocrine carcinoma, RCC renal cell carcinoma, RMS rhabdomyosarcoma, SCC squamous cell carcinoma; SmCC: small cell carcinoma

aExcept for cutaneous SCC, site not specified as head and neck, but are likely to be head and neck primaries

The significance of this study that analyzes metastases to the parotid lies in correctly diagnosing metastases in the absence of a known primary, or when clinical details are inadequate. It is noteworthy that, in a proportion of cases, a parotid mass due to metastasis could be the initial presentation of a malignancy elsewhere (1 case), and that the primary site may remain unidentified (n = 4). Recent studies suggest that mutation signature analysis may be useful in determining the origin of metastases in the parotid gland [27]. Pre-operative distinction of metastases to parotid from primary tumors also has significant impact on management. Firstly, clinical stage N0 head and neck mucosal SCC with parotid metastasis is an indication for parotidectomy with ipsilateral cervical lymph node dissection, followed by appropriate adjuvant therapy [28]. Next, in cases where the primary site is unknown, identification of metastases mandates appropriate work up for its detection. Further, parotid involvement has independent prognostic significance. Meticulous review of our cases, with correlation of cytology and histology, provided an insight into common pitfalls in interpretation of parotid gland aspirates and biopsies, especially in the absence of relevant clinical data. One case reported as poorly differentiated carcinoma on cytology and as adenocarcinoma NOS on biopsy was reviewed with the additional past history of lung adenocarcinoma. On morphology, the tumor resembled a salivary duct carcinoma, with high grade MEC entering the differential diagnosis, but was negative for AR and p40. Immunohistochemistry performed for napsin and TTF-1 was positive, and the diagnosis was revised to metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. A case of eyelid sebaceous cell carcinoma with metastatic deposits in the parotid showed foci of pagetoid spread along the salivary ducts. Such a pagetoid spread if sampled in a core biopsy would pose great difficulty in differentiation from a primary intraductal carcinoma. Thus, morphology alone in the absence of relevant history can often be misleading, particularly on FNAs and biopsies, and clinicians should ensure that they convey details of proven or suspected primary lesions elsewhere in every case.

Interestingly, the reverse also holds true, with the knowledge of a primary malignancy elsewhere leading to bias in reporting. Three cases reported as metastases had to be excluded from our study as they were found to be primary salivary gland tumors on review (Table 1). Thus, overlapping histological features and metaplastic changes may result in a second primary tumor in the parotid being diagnosed as metastasis from a known primary. We deduced from review of these cases that salivary duct carcinoma can often be mistaken for a metastatic SCC and in the absence of definite keratinization, it would be wise to perform AR immunostaining to exclude the former. Absence of atypia, and demonstration of a dual cell population and extracellular matrix aid in distinguishing pleomorphic adenoma with squamous metaplasia from metastatic SCC. In three cases of metastatic SCC, the diagnosis of high grade MEC was also considered on FNAC. However, subtle features help to distinguish the latter from SCC. High grade MEC typically contains foci of low or intermediate grade MEC, with some mucous and intermediate cells, and mucin in the background; overt keratinization and keratin pearls are absent; and staining with epithelial mucins MUC1, MUC2, MUC4 and MUC5AC is often useful [29, 30]. Lastly, demonstration of MAML2 gene rearrangements unique to MEC definitively excludes SCC.

Conclusion

Diagnosing a metastatic tumor in the parotid is often a challenge, necessitating a detailed evaluation of clinical data in concert with morphological findings. Without the relevant clinical history, the possibility of metastasis is rarely considered, and metastases are diagnosed as poorly differentiated malignancies, particularly on limited samples like FNACs and core biopsies. Malignancies of the eye and ocular adnexa are the most common primaries that metastasize to parotid, in populations where the incidence of cutaneous SCC is low. Thus, the possibility of metastasis should be always considered when features characteristic of a primary salivary gland tumor are absent, even if a primary elsewhere is not known. While metastatic tumors can mimic primary parotid neoplasms, the reverse is also true, furthering the diagnostic conundrum. While the importance of obtaining proper history cannot be stressed enough, a known primary elsewhere should not bias the pathologist in making a hurried diagnosis of metastasis. In difficult cases, immunohistochemistry and molecular testing can aid in reaching an accurate diagnosis.

Author Contributions

AK conceptualized and designed the study; histology and cytology material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JS, AK, DR and DM; clinical data was provided by AT, SVSD, AS, SB; first draft of the manuscript was written by JS, all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained to conduct this retrospective analysis of archival material.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kessler AT, Bhatt AA. Review of the major and minor salivary glands, Part 2: Neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2018;8:48. doi: 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_46_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bou-Assaly W. The forgotten lymph nodes: review of the superficial head and neck lymphatic system. J Radiol Imaging. 2016;1:9–13. doi: 10.14312/2399-8172.2016-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastore A, Ciorba A, Soliani M, et al. Secondary malignant tumors of the parotid gland: not a secondary problem! J BUON. 2017;22:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franzen A, Buchali A, Lieder A. The rising incidence of parotid metastases: our experience from four decades of parotid gland surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2017;37:264–269. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taxy JB. Squamous carcinoma in a major salivary gland: a review of the diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:740–745. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0740-SCIAMS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanuelli E, Ciorba A, Borsetto D, et al. Metastasis to parotid gland from non head and neck tumors. J BUON. 2018;23:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzen AM, Günzel T, Lieder A. Parotid gland metastases of distant primary tumours: a diagnostic challenge. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bron LP, Traynor SJ, McNeil EB, O'Brien CJ. Primary and metastatic cancer of the parotid: comparison of clinical behavior in 232 cases. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1070–1075. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200306000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifert G, Hennings K, Caselitz J. Metastatic tumors to the parotid and submandibular glands: analysis and differential diagnosis of 108 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1986;181:684–692. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(86)80044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuyens M, Schüpbach J, Stauffer E, Zbären P. Metastatic disease to the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:844–848. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malata CM, Camilleri IG, McLean NR, Piggoat TA, Soames JV. Metastatic tumours of the parotid gland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:190–195. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(98)90496-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarangi J, Kakkar A, Roy D, Thakur R, Singh CA, Sharma MC. Ocular non-teratoid medulloepithelioma with teratoid metastases in ipsilateral intraparotid lymph nodes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31:126–130. doi: 10.1177/1120672119870079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarangi J, Konkimalla A, Kaur K, Sikka K, Sen S, Kakkar A. Endocrine mucin producing sweat gland carcinoma with metastasis to parotid gland: not as indolent as perceived? Head Neck Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakkar A, Biswas A, Goyal N, et al. The expression of cyclin D1, VEGF, EZH2 and H3K27me3 in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of CNS: possible role in targeted therapy. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:729–737. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shashinder S, Tang IP, Velayutham P, et al. A review of parotid tumours and their management: a ten-year-experience. Med J Malaysia. 2009;64:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashiwagi N, Murakami T, Toguchi M, et al. Metastases to the parotid nodes: CT and MR imaging findings. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2016;45:20160201. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer M, Thoelken R, Jering M, Märkl B, Zenk J. Metastases of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma seem to be the most frequent malignancies in the parotid gland: a hospital-based study from a salivary gland center. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:843–851. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khullar G, Saikia UN, De D, Radotra BD. Nonmelanoma skin cancers: an Indian perspective. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:55–62. doi: 10.4103/2349-6029.147282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussaini AS, Dombrowski JJ, Bolesta ES, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Esthesioneuroblastoma with bilateral metastases to the parotid glands. Head Neck. 2016;38:E2457–2460. doi: 10.1002/hed.24425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purkayastha A, Sharma N, Pathak A, Kapur BN, Dutta V. An extremely rare case of metastatic retinoblastoma of parotids presenting as a massive swelling in a child. Transl Pediatr. 2016;5:90–94. doi: 10.21037/tp.2016.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, Li YJ, Zhang SB, Cheng QL, Zhang Q, He LS. Metastatic retinoblastoma of the parotid and submandibular glands: a rare case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17:229. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0627-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzini C, Pieretti G, Vicini G, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in the conjunctiva with periparotid lymph node metastases. Cornea. 2020;39:519–522. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhoulaiby S, Abdulrahman A, Alouni G, Mahfoud M, Shihabi Z. Extra-CNS metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme to cervical lymph nodes and parotid gland: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:1672–1677. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swinnen J, Gelin G, Fransis S, Vandevenne J, Van Cauter S. Glioblastoma with extracranial parotid, lymph node, and pulmonary metastases: a case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14:1334–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Rojas AE, Diaz-Perez JA, Amaro D, Lozano-Castillo A, Chinchilla-Olaya SI. Glioblastoma metastasis to parotid gland and neck lymph nodes: fine-needle aspiration cytology with histopathologic correlation. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:409–415. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0448-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolokythas A, Weiskopf S, Singh M, Cabay RJ. Renal cell carcinoma: delayed metachronous metastases to parotid and cerebellum. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:1296–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller SA, Gauthier ME, Ashford B, et al. Mutational patterns in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:1449–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S, Fang QG, Liu FY, Sun CF. Parotid gland metastasis of lung cancer: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:119. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson L, van Heerden MB, Ker-Fox JG, Hunter KD, van Heerden WFP. Expression of mucins in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:491–502. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01226-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handra-Luca A, Lamas G, Bertrand JC, Fouret P. MUC1, MUC2, MUC4, and MUC5AC expression in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:881–889. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000159103.95360.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.