Abstract

Background

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (PCBCL) presents only in the skin at the time of diagnosis with no evidence of extracutaneous disease, and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL) is the most common subtype. There is currently a lack of prospective randomized control trials and large retrospective studies investigating the efficacy of different treatment options for PCFCL. This retrospective study was conducted to describe our local clinical experience and outcomes of patients treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Objectives

To describe our local clinical experience and treatment outcomes of patients treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Methods

A retrospective study consisting of 25 PCFCL patients treated with different modalities. Patient records were reviewed and analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier estimation and SAS 9.4 software.

Results

After the initial treatment, all patients had CR except for 1 patient in the observation group. Further, 60% of patients in surgery, 20% in chemoimmunotherapy, 67% in rituximab monotherapy, 33% in steroid injection/systemic prednisone, and 33% in observation experienced a relapse. Although no significant difference was found between treatment groups due to the small sample size, time to relapse trends provides insight into treatment responses. Chemoimmunotherapy had the lowest relapse rate in the first 5 years post-treatment, whereas surgery had a higher tendency to relapse.

Conclusions

Despite the potential for rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy to yield adverse effects, it is effective in achieving a prolonged clinical remission in patients with PCFCL. It remains a reasonable treatment option for diffuse, extensive, or treatment-resistant disease.

Keywords: dermatology, lymphoma, cutaneous, rituximab, chemoimmunotherapy

Introduction

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (PCBCL) is a B-cell lymphoma that presents only in the skin at the time of diagnosis with no evidence of extracutaneous disease. 1 There are 3 main subtypes of PCBCL: primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (PCMZL); primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCL, leg type); and primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). 2 PCFCL accounts for approximately 60% of PCBCL, and is the most common subtype. 3 -5 Increased incidence is observed with male gender and older age. 3,4,6 PCFCL typically presents as a solitary lesion or grouped papules, plaques, or nodules with a predilection for the head, neck, and trunk (Figure 1). 3,5,7 The diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, along with histological and cytological examinations, complemented by phenotypic and genotypic studies. 8 It is important to distinguish PCFCL from systemic follicular lymphoma as well as other subtypes of PCBCL. In the majority of cases, PCFCL has a immunophenotype of CD19+, CD20+, BCL6 +without t(14;18) chromosomal translocation. 8

Figure 1.

A case of extensive PCFCL involving the forehead and scalp. Abbreviation: PCFCL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma.

There is currently a lack of prospective randomized control trials investigating standard treatments of PCFCL, or large retrospective studies evaluating and comparing different treatment options. Treatments used include radiotherapy (RT), surgical excision, topical therapies (eg, topical corticosteroid, topical nitrogen mustard, and bexarotene), intralesional (IL) corticosteroids, cryotherapy, immune-based modalities, such as rituximab, interferon, and imiquimod, multiagent chemotherapy, and chemoimmunotherapy.

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody targeting CD20 antigens on the surface of B cells. 9 Data from large randomized clinical trials have shown that the addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy regimens improves both the response rate and overall treatment outcomes in patients with B-cell lymphomas, such as follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. 10 -14 Rituximab has thus been utilized in the management of primary cutaneous lymphomas, including PCFCL. Although sample sizes are small, these studies support rituximab as a reasonable treatment option for PCFCL, particularly where local treatment is not effective or desirable. 7,15 -21 Intravenous rituximab appears safe with relatively few side effects. 22 Intralesional rituximab has also shown favorable results and is potentially more cost-effective. The recent availability of subcutaneous rituximab may potentially reduce the burden on health care resources and further improve quality of life for patients. 23 This retrospective study aims to describe our local clinical experience in patients with PCFCL, assess the number of patients requiring therapy, and represent the outcomes of patients treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Patients and Methods

Patients

In this retrospective case series, we enrolled all patients seen between January 1, 2008, and May 31, 2019, at CancerCare Manitoba with the diagnosis of PCFCL. Twenty-six patients were identified through the Manitoba Cancer Registry using the ICD10 code C82.6 and morphology code 9597. Pathology reports, read by dermatopathology, and clinical notes were carefully reviewed to ensure a diagnosis consistent with PCFCL. Seven patients were excluded from data analysis due to diagnoses being incorrectly coded, pathology results being non-diagnostic, or they were treated outside of the institution and were never referred. Additionally, 6 patients with PCFCL were found in the lymphoma clinic record and were added to the study population. Therefore, a total of 25 patients were included for data analysis and their charts were reviewed.

All patients were managed in the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at CancerCare Manitoba by a hematologist oncologist and a dermatologist. Staging was carried out before treatment. All patients had a careful physical examination with routine bloodwork carried out. CT scans with IV contrast were routinely carried out on the majority of patients unless patients had renal dysfunction. The majority of patients underwent CT scans involving the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow aspirates and biopsies were not conducted on a routine basis for patient staging purposes. Different treatment modalities that patients received included surgical excision, radiotherapy, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (ILTA) injection, systemic prednisone, rituximab monotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy (bendamustine with rituximab [BR], and rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, prednisone combination therapy [R-CVP]; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient Treatment Flowchart. Abbreviation: IL, Intralesional.

Response Criteria and Statistical Methods

Patient charts were reviewed to document treatment and outcomes. Assessment of outcome was based upon treatment response, relapse rate, time to relapse, and adverse events. 18 Treatment response was categorized into complete response (CR), the complete disappearance of all PCFCL lesions; partial response (PR), a decrease in 50% or more PCFCL lesions; stable disease (SD), a response that is between partial response and progressive disease; and progressive disease (PD), an increase of over 25% of existing tumor volume or appearance of any new PCFCL lesion. 18 Assessment of PCFCL response is based on clinical evaluation and does not require imaging studies. Date when CR was identified and relapse dates were recorded. The cutoff for patient follow-up was July 20, 2019 or date of death. Time to progression curves were calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimation. Results were analyzed using SAS 9.4 statistical software.

Results

Patients

Clinical data including age, gender, location and lesion characteristics, treatments, treatment response, relapse status, time to relapse, relapse treatments, adverse events, current status, and follow-up time are summarized in Table 1. One patient was lost to follow-up.There were 25 patients included in data analysis with a mean age of 62 years (range 30-92 years) at presentation and a male to female ratio of 1.5. Of these, 20 patients had localized lesions, and 5 patients had diffuse lesions. All patients would be classified as Stage 1E. 24 Most of the lesions are located on the face or scalp. None of the patients developed extra-cutaneous involvement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Treatment Response in 25 Patients With PCFCL.

| Patient no/Gender/Age | Site of lesion | Clinical description and # of lesions | Treatments | Treatment response | # of relapses | Time to relapse (months) | Relapse treatment | Current status (June 2019) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 /M/63 | Scalp | Localized, 4-cm nodule with a number of smaller nodules, each about 0.5 to 1 cm | BR*6 | CR | 0 | CR | 64 | ||

| 2 /M/60 | Scalp | Single, localized 6-7 cm lesion on the right anterior scalp | BR*6 | CR | 0 | CR | 68 | ||

| 3 /M/43 | Scalp | Localized, 1-1.5 cm on the left scalp on initial presentation. Extensive frontal scalp involvement was noted on a later exam | R-CVP*6 | CR | 0 | CR | 54 | ||

| 4 /M/72 | Face | Multiple, diffuse plaques of unspecified size to both temples extending down to the left cheek, and neck | R-CVP*6 | CR | 0 | CR | 28 | ||

| 5 /M/59 | Face, Scalp | Diffuse, raised, reddened areas with nodules on the left forehead extending into the hair line with difficult demarcation; 3-4 cm skin involvement on the right forehead extending into the hairline | R-CVP*8 | CR | 1 | 94 | None | CR (spontaneous remission) | 139 |

| 6 /F/57 | Face | A 1-cm pink lesion with several other flattened pink areas on the right forehead | Rituximab q7d *4 | CR | 1 | 6 | BR*2; R-CVP*4; maintenance rituximab a |

CR | 84 |

| 7 /F/73 | Legs, Arms, Trunk | 12-14 ill-defined, erythematous papules measuring <1 cm over legs, arms, and trunk, which became more extensive plaques over time | Rituximab q7d *4 | CR | 2 | 33,43 | Rituximab q1w*4; adjusted R-CVP*5; maintenance rituximab b |

CR | 105 |

| 8 /M/52 | Scalp | Single, localized lesion of unspecified size involving the mid vertex of the scalp | Rituximab q7d *4 | CR | 0 | CR | 85 | ||

| 9 /M/92 | Trunk | Multiple lesions: One 2-cm erythematous lesion on the left anterior chest with satellite nodules adjacent to it | Surgical excision | CR | 0 | CR | 5 | ||

| 10 /F/63 | Face | Two lesions localized to the nose: one measuring 0.7 cm; one measuring 0.3-0.4cm in diameter | Surgical excision | CR | Unknown | Lost to follow-up | 25 | ||

| 11 /M/74 | Face | Single, localized cystic lesion on the right upper lip, measuring 1.1 × .9 cm | Surgical excision | CR | 0 | CR | 6 | ||

| 12 /M/54 | Face | Single, localized lesion of unspecified size lateral to the right eye | Surgical excision | CR | 0 | CR | 67 | ||

| 13 /M/69 | Scalp | Two lesions on the left upper forehead: one was biopsied before referral; the other was a 0.5-cm indurated lesion lateral to the biopsy scar | Surgical excision | CR | 1 | 2 | ILTA injection c | CR | 19 |

| 14 /F/59 | Face | Multiple lesions of unspecified size on the nose, left temple, and right forehead | Surgical excision | CR | 2 | 17;6 | Radiotherapy; surgical excision | CR | 55 |

| 15 /M/30 | Face | Single, localized 3 × 2.5-cm nodule under the left eye, adjacent to the left nose bridge | Surgical excision | CR | 2 | approx. 13; 7 | Surgical excision; BR*6; maintenance rituximab IV q12w*4, switched to subcutaneous rituximab q12w |

CR | 31 |

| 16 /F/48 | Trunk | Single, localized lesion of unspecified size over the posterior right shoulder | Surgical excision | CR | 4 | 4,17,63,4,12 | Radiation; varying doses of ILTA injection | CR | 135 |

| 17 /F/60 | Face | Single, localized 3 × 1-cm lesion on the right forehead | Surgical excision | CR | 2 | 64,37 | Surgical excision*2 | CR | 159 |

| 18 /M/81 | Scalp | Single, localized 5.8 × 4.8-cm lesion on the left parietal scalp | Surgical excision with graft | CR | 1 | 6 | R-CVP*6 | CR | 50 |

| 19 /F/74 | Face | Single, localized yellow swelling on the left nasal tip | Radiation | CR | 0 | CR | 71 | ||

| 20 /F/55 | Arms, trunk, leg | Numerous, diffuse lesions of varying sizes on bilateral arms, back, and the right thigh | Varying doses ILTA injection | CR | 11 | 1,4,7,5,6,12, 10,5,5,6 | Varying doses of ILTA injection | CR | 116 |

| 21 /M/92 | Face, under the left ear, trunk | Multiple, diffuse lesions: One 8 × 10-cm lesion on right cheek; one nodule near left ear; several lesions of unspecified size on upper back; one large lesion of unspecified size on the right buttock | Varying doses of systemic Prednisone | CR | 0 | CR | 34 | ||

| 22 /M/60 | Scalp | Single, localized 3.5 × 4-cm nodule on posterior scalp, with a 1-cm induration after incisional biopsy | None (observation) | CR | 0 | CR (spontaneous remission) | 59 | ||

| 23 /F/87 | Face | Single, localized 4 × 6-cm erythematous macule over the left temple | None (observation) | CR | 1 | 6 | ILTA injection | CR | 53 |

| 24 /M/36 | Trunk, scalp, arms | Multiple, diffuse lesions: original lesion of biopsy with unspecified size on the right anterior axillary line; One 0.5-cm lesion superior to the biopsy scar; another lesion of unspecified size inferior to the scar; scattered lesions of unspecified sizes on the scalp and bilateral arms; numerous 0.5-1-cm papules on the back | None (observation) | PR | NA | Lesions | 30 | ||

| 25 /F/42 | Face | Two localized nodules of unspecified sizes on the right temple | None (observation for the posterior lesion); ILTA injection for the anterior lesion d | CR | 0 | CR | 40 |

Abbreviations: BR, bendamustine with rituximab; CR, complete response; ILTA, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide; PCFCL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma; R-CVP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, prednisone combination therapy.

aMaintenance rituximab: 810 mg solution IV q12w for 8 doses

bMaintenance rituximab: 1400 mg solution subcutaneous q2w for 8 doses

cILTA injection: 20 mg/ml, total of 0.2 ml

dILTA injection : 20 mg/ml, total of 0.3 ml

Response

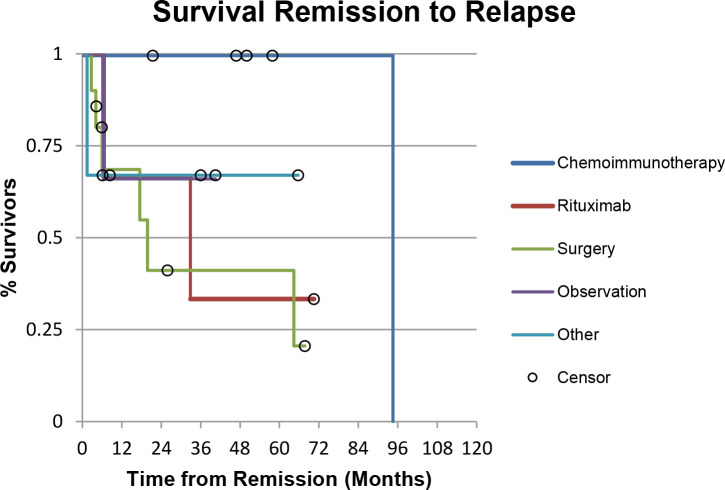

Initial treatments included surgical excision in 10 patients, chemoimmunotherapy in 5 patients, rituximab monotherapy in 3 patients, varying doses of prednisone in 1 patient, ILTA injection in 2 patients, and radiation in 1 patient. In addition, 4 patients had lesions that were monitored without active treatment. After the initial treatment, all patients had a CR except for one in the observation group, who had a PR. The mean time to CR in the observation group was 10.67 months (range 4-19 months). The median follow-up time was 55 months (range 5-159 months). Six patients (60%) in the surgery group, 1 patient (20%) in the chemoimmunotherapy group, 2 patients (67%) in the rituximab monotherapy group, 1 patient (33%) in the other treatment group, and 1 patient (33%) in the observation group experienced a relapse (Table 2). Relapsed patients were then treated on a case-by-case basis (Figure 2). Time to progression was shown using Kaplan-Meier survival curves with an overall P value of .16 (Figure 3). The chemoimmunotherapy group had the highest percentage of patients (100%) achieving and maintaining CR for 5 years post treatment, with 1 patient relapsing at the 94-month mark. The surgery group had the highest percentage (60%) of patients relapsing within the first 5 years post treatment. No statistical significance was found comparing different treatment groups due to the small sample size.

Table 2.

Outcomes After Initial Treatment.

| Initial treatment | N | CR (%) | Relapse (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical excision | 10 | 10 (100%) | 6 (60%) a |

| Chemoimmunotherapy | 5 | 5 (100%) | 1 (20%) |

| Rituximab monotherapy | 3 | 3 (100%) | 2 (67%) |

| Other b | 3 | 3 (100%) | 1 (33%) |

| Observation | 4 | 3 (75%) | 1 (33%) |

Abbreviations: BR, bendamustine with rituximab; CR, complete response; R-CVP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, prednisone combination therapy.

Chemoimmunotherapy: BR, or R-CVP.

aOne patient treated with surgical excision was lost to follow-up.

bOther treatments included varying doses of systemic prednisone, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (ILTA) injection, and radiation.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for time to progression survival, showing the estimated time patients in each treatment group remained disease free after CR was first identified. Overall P = .16. Abbreviation: CR, complete response.

Tolerance

Among the 5 patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy, 3 patients had mild side effects. Patient 1 experienced epigastric discomfort, nausea, chills, low back discomfort, and phlebitis with 6 cycles of BR treatment. Patient 2 experienced some fatigue and nausea. Interestingly, patients 1 and 3, both having scalp lesions, experienced tingling of the scalp, which may be suggestive of the anti-tumor effect. One patient treated with rituximab monotherapy developed urticaria. All adverse events in this group were of limited duration, and resolved either with interruption in infusion or a reduction in infusion rate and medications for symptomatic control (diphenhydramine, antacid). Patient 19, who had radiation, experienced significant post-radiation cutaneous inflammation.

For relapses, 4 patients were treated at least once with chemoimmunotherapy. Patient 6 experienced fatigue, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, and 10-pound weight loss over the 2 cycles of BR treatment. Patient 18 also experienced constipation. Patient 15 experienced rash with rituximab and complained about feeling “fuzzy” due to prednisone in the chemoimmunotherapy regimen. Interestingly, he had a marked exacerbation of pre-existing sciatica toward the end of maintenance rituximab therapy. It was unclear whether it was solely a side effect of treatment and was still being investigated. Patient 7 again experienced urticaria and developed signs of neuropathy in her hands and feet. Fortunately, most of the adverse events were resolved by adjusting the drug regimen or administering medications for symptomatic control.

Discussion

PCFCL is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma with a favorable prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of over 90%. 8 Due to its heterogenous presentation, treatments may vary significantly, and many factors need to be considered while selecting treatments. These include number, size, location and extent of the lesions, and whether it is localized to one region, or diffuse with multiple lesions in different locations. For small and localized lesions, the optimal treatments may be surgical excision or radiotherapy. 15,22 In the literature, there are several large studies examining RT in PCFCL showing near CR rate and a relapse rate ranging from 30% to 76%. 15 Similarly, a study with 93 patients undergoing surgical excision in PCFCL showed a 98% CR rate and 40% relapse rate. 15 Although RT and surgical excisions have been shown to be effective, they are not without limitations. First, the optimal radiation dose and margin for RT have not been established, which may be the cause of the highly variable relapse rate mentioned above. 4,15,25 -27 RT and surgery are most effective in treating localized and solitary lesions, but impractical in treating more diffuse lesions. 22 Adverse effects, including alopecia from RT and scarring from surgery, can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life, and depending on the location of the lesions, make them less appropriate treatment options. 22 Studies examining other treatment options are even more limited by small sample sizes. In our patient population, 10 people were initially treated with surgical excision, sometimes to obtain the diagnostic biopsy specimen, and many were left with visible scars. Suitability for surgery is often dependent upon size and location of the PCFCL. For example, patient 15 went through an extensive facial surgery prior to referral to CancerCare Manitoba, followed by a subsequent surgery to repair the ectropion of the left lower eyelid. Patient 12 also had a visible scar lateral to the eye. In addition, surgery alone had a relapse rate of 60% in our patient cohort, which was the highest among the different treatment groups. Among the 6 patients that relapsed in the surgery group, 2 were treated with surgical excision as the second treatment, and both had relapsed again. Therefore, although surgical excision has an 100% CR rate, it has a higher tendency to relapse compared with other treatments, and patients require long-term follow-up. 28

Rituximab has changed the standard of care for Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma since its first approval for clinical use in 1997. With its proven efficacy in systemic lymphoma and low toxicity profile, it has been utilized increasingly in PCBCLs, including PCFCL. Although limited by the rarity of PCFCL and small study populations, many recent studies have shown promising results. 15 -22 In the study by Quereux et al 16 (n = 11), 10 of the 11 patients experienced a PR (PR rate, 91%) and 1 had SD after 4 infusions. Relapse was found in 5 patients in follow-up (relapse rate, 45%). In a similar study by Morales et al 18 (n = 15), all 10 patients with PCFCL had a response after 4 weekly doses of standard rituximab treatment, with 80% achieving CR. However, there was no relapse information. Similar results are shown according to Valencak et al 21 (n = 16), in which 11 patients with PCFCL experienced CR after varying doses of rituximab (CR rate, 100%) with 3 people relapsing in follow-up (relapse rate, 27%). In our study, 3 patients were treated with 4 weekly doses of systemic rituximab (375 mg/m2) as initial treatment, and all 3 experienced CR. However, 2 people had a relapse after 6 and 33 months, respectively, of clinical remission (relapse rate, 67%). One of them was treated with another cycle of rituximab as the second treatment, but unfortunately relapsed again. Thus, as shown by our results as well as other studies, rituximab has a good overall response, but a variable relapse rate.

Recently, the incorporation of rituximab into chemotherapy regimens (known as chemoimmunotherapy) has become widely accepted and used as a standard therapy in treating B-cell lymphomas, because of the synergy between chemotherapy and rituximab, without significant added toxicity. 10,12,13 Chemoimmunotherapy has thus been increasingly used in treating PCBCLs that are more aggressive, or with lesions that are diffuse, extensive, or resistant, as seen in DLBCL, leg type, and PCFCL. 14 Studies show that the combination of rituximab and chemotherapeutic agents synergistically affects apoptosis of neoplastic lymphocytes. 29 Our study results showed an 100% CR rate and a relapse rate of 20% in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy (BR or R-CVP). Only 1 out of 5 patients relapsed, after being in clinical remission for close to 8 years, who later went into spontaneous remission without treatment. For relapsed patients with other previous treatments, 3 were treated with chemoimmunotherapy and all had CR with no further relapse on follow-up. The relapse rate specifically for chemoimmunotherapy is better when compared to the relapse rate for rituximab monotherapy. It is very challenging to find studies with similar patient conditions and treatment regimens. Fierro et al 14 studied the effect of cyclophosphamide and rituximab combined therapy in treating relapsed PCBCLs (n = 7). Five patients were diagnosed with PCFCL; 4 of these 5 patients had extracutaneous involvement and were previously treated with chemotherapy. With the combined chemoimmunotherapy treatment, 4 patients experienced CR (CR rate, 80%) and 2 patients relapsed (relapse rate, 50%). Although there are studies examining rituximab monotherapy or chemotherapy alone in the treatment of PCFCL, very few focus on the effect of combined chemoimmunotherapy, especially with our specific drug regimens, making our study unique in describing the outcomes of using R-CVP or BR in treating diffuse, extensive, or resistant PCFCL.

In terms of adverse events, rituximab alone has a low toxicity profile. Reactions usually develop during the first infusion and can present as dyspnea, fever, chills, rigors, urticaria, and angioedema. These symptoms can be due to cytokine release and/or tumor loading, rather than an anaphylactic reaction. 30,31 However, rituximab results in patients mounting poor immune responses to vaccinations for many months following completion of therapy. This is a concern, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. 32 Given the indolent nature of PCFCL, risks and benefits need to be carefully balanced when treatment decisions are made. In our treatment experience, rituximab monotherapy has been well tolerated, with only 1 patient developing urticaria, which resolved shortly after interruption of the infusion and the administration of diphenhydramine. For chemoimmunotherapy, although the addition of rituximab to the treatment regimen did not add significant side effects, the overall incidence of adverse events is still non-negligible. Among our patients treated with BR chemoimmunotherapy, symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea, phlebitis, weight loss, and possible exacerbation of pre-existing sciatica were experienced. Patients treated with R-CVP experienced fewer adverse events, including constipation and peripheral neuropathy. As mentioned, 2 patients with scalp lesions treated with BR and R-CVP, respectively, experienced tingling over the scalp of limited duration during their first treatments, which may be suggestive of the anti-tumor effect. None of the patients experienced grade 4 toxicity, and most adverse events were resolved shortly after symptomatic control and regimen adjustment. However, it should still be noted that although chemoimmunotherapy is highly effective in treatment and preventing relapse, given the associated adverse effects, risk/benefit should be carefully weighed given the indolent nature of PCFCL. Perhaps chemoimmunotherapy should be considered for those PCFCL patients with lesions that are diffuse, extensive, treatment resistant, or in areas with a poor expected cosmetic outcome using other modalities.

Maintenance rituximab therapy was used in 3 patients in the treatment of their relapse following chemoimmunotherapy. Rituximab maintenance after induction chemoimmunotherapy was shown to provide a significant long-term progression-free survival benefit in follicular lymphoma according to the PRIMA study results released very recently in 2019. 33 The efficacy is supported by our result: among our 3 patients treated with maintenance rituximab, no one has relapsed after a follow up period of 84 months, 31 months, and 105 months.

Interestingly, 2 of the 3 patients were given the maintenance rituximab in the form of subcutaneous administration, which also yielded favorable outcomes. In fact, as Macdonald et al 23 suggested, use of subcutaneous rituximab has a number of key advantages over the IV formulation, such as fixed dosing, short prep time, no wastage, fast administration, shorter chair time, and shorter health care provider time. Therefore, future studies should be directed to evaluate the efficacy of subcutaneous rituximab in treating PCFCL as well as other subtypes of PCBCL in the hope to further improve patient’s quality of life and reduce health care burdens. In addition, it would be interesting to track the CD20+B lymphocyte levels before and after treatment via flow cytometry to measure correspondence to treatment, and possibly use the intensity of CD20 expression to determine the sensitivity or resistance of PCFCL to rituximab treatment.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapy is effective in achieving a prolonged clinical remission in patients with PCFCL. For patients with lesions that are diffuse, extensive, or resistant to treatment, chemoimmunotherapy may be a reasonable treatment option. However, further studies with larger samples are required to confirm our observation. A careful risk/benefit analysis needs to be undertaken prior to the selection of treatment, given the indolent nature of this lymphoma.

Acknowledgment

We thank Xun Wu, a PhD candidate from the Department of Immunology, University of Manitoba, for her expertise and assistance in editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Marni Wiseman https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9634-3750

References

- 1. Willemze R., Kerl H., Sterry W. et al. Eortc classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90(1):357-371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Willemze R., Cerroni L., Kempf W. et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-1714. 10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swerdlow S., Campo E., Harris NL. et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th Edn. IARC WHO Classification of Tumours; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zinzani PL., Quaglino P., Pimpinelli N. et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: the Italian Study Group for cutaneous lymphomas. JCO. 2006;24(9):1376-1382. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rubio-Gonzalez B., Zain J., Rosen ST., Querfeld C. Clinical manifestations and pathogenesis of cutaneous lymphomas: current status and future directions. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(1):16-36. 10.1111/bjh.14402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bradford PT., Devesa SS., Anderson WF., Toro JR. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood. 2009;113(21):5064-5073. 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suárez AL., Pulitzer M., Horwitz S., Moskowitz A., Querfeld C., Myskowski PL. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: Part I. Clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(3):329.e1-329.e13. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lima M. Cutaneous primary B-cell lymphomas: from diagnosis to treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):687-706. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molina A. A decade of rituximab: improving survival outcomes in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59(1):237-250. 10.1146/annurev.med.59.060906.220345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zelenetz AD., Gordon LI., Wierda WG. et al. Non-hodgkin’s lymphomas, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(6):916-946. 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Czuczman MS., Grillo-López AJ., White CA. et al. Treatment of patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma with the combination of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):268-276. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coiffier B., Lepage E., Brière J. et al. Chop chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235-242. 10.1056/NEJMoa011795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molina A. A decade of rituximab: improving survival outcomes in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59(1):237-250. 10.1146/annurev.med.59.060906.220345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fierro MT., Savoia P., Quaglino P., Novelli M., Barberis M., Bernengo MG. Systemic therapy with cyclophosphamide and anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) in relapsed primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a report of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2):281-287. 10.1067/S0190-9622(03)00855-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senff NJ., Noordijk EM., Kim YH. et al. European organization for research and treatment of cancer and international society for cutaneous lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112(5):1600-1609. 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quéreux G., Brocard A., Peuvrel L., Nguyen JM., Knol A-C., Dréno B. Systemic rituximab in multifocal primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(5):562-567. 10.2340/00015555-1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gellrich S., Muche JM., Wilks A. et al. Systemic eight-cycle anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) therapy in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas--an applicational observation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):167-173. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morales AV., Advani R., Horwitz SM. et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(6):953-957. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy GA., Blum R., McCormack C., Prince HM. Treatment of primary cutaneous follicular centre lymphoma with rituximab: a report of two cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(1):34-37. 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fink-Puches R., Wolf IH., Zalaudek I., Kerl H., Cerroni L. Treatment of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(5):847-853. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valencak J., Weihsengruber F., Rappersberger K. et al. Rituximab monotherapy for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: response and follow-up in 16 patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(2):326-330. 10.1093/annonc/mdn636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suárez AL., Querfeld C., Horwitz S., Pulitzer M., Moskowitz A., Myskowski PL. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: Part II. Therapy and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(3):343.e1-343.e11. 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacDonald D., Crosbie T., Christofides A., Assaily W., Wiernikowski J. A Canadian perspective on the subcutaneous administration of rituximab in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(1):33-39. 10.3747/co.24.3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Campo E., Harris NL., Jaffe ES. et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piccinno R., Caccialanza M., Berti E. Dermatologic radiotherapy of primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(1):49-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Senff NJ., Hoefnagel JJ., Neelis KJ. et al. Results of radiotherapy in 153 primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas classified according to the WHO-EORTC classification. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(12):1520-1526. 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gulia A., Saggini A., Wiesner T. et al. Clinicopathologic features of early lesions of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type: implications for early diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):991-1000. 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prince HM., Yap LM., Blum R., McCormack C. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28(1):8-12. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chow KU., Sommerlad WD., Boehrer S. et al. Anti-CD20 antibody (IDEC-C2B8, rituximab) enhances efficacy of cytotoxic drugs on neoplastic lymphocytes in vitro: role of cytokines, complement, and caspases. Haematologica. 2002;87(1):33-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Byrd JC., Waselenko JK., Maneatis TJ. et al. Rituximab therapy in hematologic malignancy patients with circulating blood tumor cells: association with increased infusion-related side effects and rapid blood tumor clearance. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(3):791-795. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winkler U., Jensen M., Manzke O., Schulz H., Diehl V., Engert A. Cytokine-release syndrome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and high lymphocyte counts after treatment with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab, IDEC-C2B8). Blood. 1999;94(7):2217-2224. 10.1182/blood.V94.7.2217.419k02_2217_2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nazi I., Kelton JG., Larché M. et al. The effect of rituximab on vaccine responses in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2013;122(11):1946-1953. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-494096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bachy E., Seymour JF., Feugier P. et al. Sustained progression-free survival benefit of rituximab maintenance in patients with follicular lymphoma: long-term results of the PRiMA study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2815-2824. 10.1200/JCO.19.01073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]