Abstract

Pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines elicit antipolysaccharide antibodies, but multiple doses are required to achieve protective antibody levels in children. In addition, the immunogenicity of experimental multivalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines varies with different polysaccharide serotypes. One strategy to improve these vaccines is to incorporate an adjuvant to enhance their immunogenicity. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs (CpG ODN) are adjuvants that promote T-cell and T-dependent antibody responses to protein antigens, but it has been unclear whether CpG ODN can enhance polysaccharide-specific antibody responses. The present studies demonstrate significant adjuvant activity of CpG ODN for antibody responses against Streptococcus pneumoniae polysaccharide types 19F and 6B induced by conjugates of 19F and 6B with the protein carrier CRM197. BALB/c ByJ mice were injected with 19F-CRM197 or 6B-CRM197 with or without CpG ODN, and sera were tested for anti-19F or anti-6B antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The polysaccharide-specific antibody response to 19F-CRM197 alone was predominantly of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgM isotypes, but addition of CpG ODN markedly increased geometric mean titers of total anti-19F antibody (23-fold), anti-19F IgG2a (26-fold), and anti-19F IgG3 (>246-fold). The polysaccharide-specific antibody response to 6B-CRM197 alone consisted only of IgM, but addition of CpG ODN induced high titers of anti-6B IgG1 (>78-fold increase), anti-6B IgG2a (>54-fold increase), and anti-6B IgG3 (>3,162-fold increase). CpG ODN also increased anti-CRM197 IgG2a and IgG3. Adjuvant effects were not observed with control non-CpG ODN. Thus, CpG ODN significantly enhance antipolysaccharide IgG responses (especially IgG2a and IgG3) induced by these glycoconjugate vaccines.

The polysaccharide capsules of encapsulated bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b) inhibit phagocytosis of these organisms and are major virulence factors. Host protection against infection caused by these encapsulated bacteria is mediated primarily by anticapsular antibodies, which facilitate complement deposition and allow for opsonization and phagocytosis (15). Capsular polysaccharides, however, are T-independent type 2 antigens and thus induce B-cell responses that are characterized by low-affinity antibodies with a limited subclass distribution (primarily immunoglobulin M [IgM] and IgG3 in mice; primarily IgM and IgG2 in humans) and a lack of immunologic memory (reviewed in reference 18). In addition, the abilities of some groups of patients (such as young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients) to respond to bacterial polysaccharides is impaired, making them more susceptible to disease caused by these pathogens.

Vaccines consisting of bacterial polysaccharides conjugated to a protein carrier have provided a successful approach for generating enhanced humoral immunity against the encapsulated bacterial pathogen, H. influenzae type b, via T-cell-dependent mechanisms (21). This approach is particularly important in high-risk populations, such as young children, and has led to a dramatic reduction in infections with H. influenzae type b in the United States (1). The carrier protein presumably allows for stimulation and expansion of carrier protein-specific T cells, which can then provide help for polysaccharide-specific B cells, thus allowing for affinity maturation, Ig class switching, and the development of B-cell memory.

While glycoconjugate vaccines are currently licensed in the United States for use against H. influenzae type b, the development of vaccines against other encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae and Neisseria meningiditis is still ongoing. Clinical trials have assessed a heptavalent vaccine for S. pneumoniae, consisting of seven different serotype-specific pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to a carrier protein, CRM197, a nontoxic mutant of diphtheria toxin (2, 12, 17, 19, 30). This heptavalent pneumococcal polysaccharide-CRM197 glycoconjugate vaccine effectively generates antipolysaccharide antibody responses in humans (19). With conventional glycoconjugate vaccines, however, multiple doses are required to achieve protective immunity in children. In addition, variable levels of antipolysaccharide antibodies are produced against different pneumococcal serotype-specific polysaccharides (19, 23, 32). Thus, current and future glycoconjugate vaccines could be significantly improved if adjuvants enhanced their immunogenicities so as to consistently provide high antibody titers to all serotypes with a minimum number of injections.

Short oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) that contain unmethylated CpG motifs have been demonstrated to be potent adjuvants for protein antigens, increasing specific antibodies, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) secretion by Th cells, and cytolytic T-cell responses (5, 7, 13, 16, 20). The CpG motif is derived from sequences found in bacterial DNA and consists of a central unmethylated CpG dinucleotide preferentially flanked by two 5′ purines and two 3′ pyrimidines (14). B cells, NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells are all directly activated by CpG DNA, resulting in production of cytokines such as IFN-γ, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha, as well as increased NK cell killer activity (14, 25, 26, 33). The activation of these immune cells by CpG DNA allows for modulation of antigen-specific immune responses.

The studies presented here tested the ability of CpG ODN to enhance production of antipolysaccharide antibodies after immunization of mice with polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines consisting of pneumococcal polysaccharide type 19F or type 6B conjugated to CRM197. These polysaccharides derive from common pneumococcal serotypes that are virulent in humans, and they are components of the experimental heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine described above. CpG ODN significantly enhanced polysaccharide-specific IgG2a and IgG3, and polysaccharide-specific IgG1 and IgM were increased to a lesser degree. Similar to other studies using protein antigens (5, 7, 16, 27), CpG ODN also enhanced antibody responses to the protein carrier, CRM197, particularly CRM197-specific IgG2a and IgG3.

This is the first study to examine the ability of CpG ODN to act as adjuvants for antipolysaccharide antibody responses after immunization with a polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine. Other studies regarding the effect of CpG ODN on antipolysaccharide antibody responses following immunization with unconjugated polysaccharide antigens have produced mixed results, depending on the composition of the vaccine, the length and sequence of the CpG ODN, and the dose of CpG ODN administered (28, 29). Unconjugated polysaccharide vaccines, however, do not elicit T-cell help, and modulation of T-cell help for antibody responses may be an important mechanism for adjuvant activity of CpG ODN. These results indicate that CpG ODN act as adjuvants that effectively enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses after immunization with a pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthetic ODN.

Synthetic ODN were from Operon Technologies (Alameda, Calif.) or Oligos Etc. (Wilsonville, Oreg.). ODN were phosphorothioate modified to increase their resistance to nuclease degradation. ODN with the following sequences were used (CpG motifs or reversed non-CpG motifs are underlined): CpG ODN 1826, TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT; non-CpG ODN 1982, TCCAGGACTTCTCTCAGGTT; CpG ODN 1760, ATAATCGACGTTCAAGCAAG; and non-CpG ODN 1908, ATAATAGAGCTTCAAGCAAG. These ODN have been well characterized for adjuvant activity in protein antigen systems (5). ODN were dissolved in 10 mM Tris–1 mM EDTA. Lipopolysaccharide content of ODN was <1 ng/mg of DNA, as measured by Limulus amebocyte assay (QCL-1000; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.).

Mice and immunizations.

BALB/c ByJ female mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions and used at 7 to 9 weeks of age. Mice were bled by tail vein on day 0, prior to immunization. Immunizations were performed and assessed using conditions (e.g., antigen dose and time points for bleeding) that were characterized in our prior published studies with these glycoconjugates (17) and in other preliminary studies (data not shown). The studies presented here used an amount of glycoconjugate to achieve doses of 5 μg of total polysaccharide and 7.5 μg of CRM197 per mouse (see below). Without the addition of CpG ODN, this was a suboptimal dose that produced antipolysaccharide antibodies (see below) but not the higher titers that were obtained with doses of 10 to 20 μg of total polysaccharide per mouse. The dose of ODN was optimized in preliminary studies and was similar to that used in previously published studies of immunization with protein antigens (5). Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) to be consistent with optimization in prior studies and to allow for the required vaccine volume in this small-animal model. Mice were injected i.p. on days 0 and 14 with vaccines containing S. pneumoniae polysaccharide type 19F or 6B conjugated to CRM197 (19F-CRM197 or 6B-CRM197, respectively; generously provided by Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines, West Henrietta, N.Y.). The approximate concentrations of polysaccharide and protein in the stock vaccine preparations were as follows: 19F-CRM197, 0.504 mg of carbohydrate/ml and 0.759 mg of protein/ml; 6B-CRM197, 0.497 mg of carbohydrate/ml and 0.718 mg of protein/ml (personal communication from Ronald Eby, Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines). The stock preparations of 19F-CRM197 or 6B-CRM197 were mixed with ODN in pyrogen-free 0.9% NaCl solution (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) and diluted to achieve 5 μg of total polysaccharide, 7.5 μg of CRM197, and 100 μg of ODN per mouse with an injection volume of 0.2 ml. Mice were bled weekly by tail vein at the indicated times.

ELISA for detection of specific antibody.

Ninety-six well plates (Immunosorp or Maxisorp; Nalge Nunc, Naperville, Ill.) were coated with purified pneumococcal type 19F or 6B polysaccharide (1 to 10 μg/ml; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with purified CRM197 (1 μg/ml; courtesy of Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines) in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS with 0.5% Tween, and blocked with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. For the 19F and 6B enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), purified S. pneumoniae cell wall polysaccharide (purchased from Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines) was added at 50 μg/ml to neat mouse sera to block any antibodies specific for contaminating cell wall polysaccharide. Mouse sera were then serially diluted in PBS with 1% BSA and incubated in the polysaccharide-coated plates overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed, and one of the following detecting antibodies was added in PBS with 0.5% Tween and 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The detecting antibody for total polysaccharide-specific Ig was goat anti-mouse kappa chain-alkaline phosphatase conjugate, and individual isotypes were detected by alkaline phosphatase conjugates of antibodies specific for mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG3, or IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.). Plates were developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (50 mg/ml in 2.5 M sodium bicarbonate–2.5 M magnesium chloride). Absorbance at 405 nm was determined using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) model 550 microplate reader. Each serum titration was assayed in duplicate, and an internal positive reference serum was used to ensure comparable plate values for each set of assays. Titers were determined at an optical density (OD) of 0.5, using two-point curve fit analysis (Microplate Manager III program; Bio-Rad). Two-point curve fit analysis was used to plot the line between the dilution points of each curve that encompassed an OD of 0.5. A dilution x value (titer) was then interpolated for the y value of 0.5, using the line equation generated by two-point curve fit analysis. Statistical differences between geometric mean titer values were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. When the maximum OD was less than 0.5, indicating a titer of <1, a titer value of zero was assigned for statistical purposes.

Several controls were performed to test for specificity of the ELISAs. First, anti-6B and anti-19F titers were <1 for all preimmune sera tested. Second, animals that were sham immunized (without the polysaccharide antigen) did not have detectable antipolysaccharide antibodies at any time point. Third, animals immunized with one polysaccharide (in conjugate form) never had a detectable titer for the other polysaccharide. Fourth, free polysaccharide was found to competitively inhibit binding of antibody to plate-bound polysaccharide in a control experiment performed with Immunosorp plates.

RESULTS

CpG ODN enhance total antipolysaccharide antibodies after immunization with a pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine, 19F-CRM197, and particularly enhance anti-polysaccharide IgG2a and IgG3.

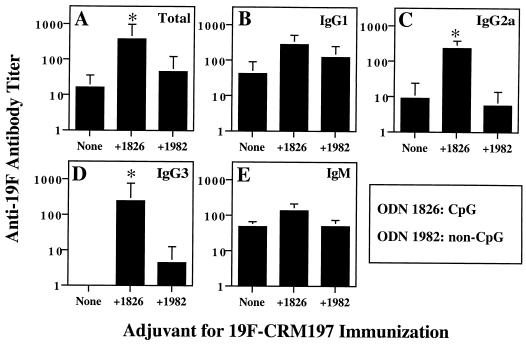

To determine whether CpG ODN act as adjuvants for antipolysaccharide responses after immunization with a pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate, BALB/c ByJ mice were injected i.p. with 19F-CRM197 with or without 100 μg CpG ODN 1826 or 100 μg of control non-CpG ODN 1982 in pyrogen-free saline on days 0 and 14. Sera were collected 2 weeks after the second immunization (day 28) and tested for the presence of anti-19F antibodies by ELISA. In the representative experiment shown in Fig. 1, the geometric mean titer (± standard error of the mean [SEM]) of total anti-19F antibody was increased significantly (23-fold) by addition of CpG ODN 1826 (Fig. 1A and data not shown). CpG-specific enhancement was particularly marked for certain antibody isotypes. As shown in Fig. 1C and D, the addition of CpG ODN 1826 significantly increased the geometric mean titers of anti-19F IgG2a (26-fold) and anti-19F IgG3 (>246-fold, from <1 to 246). Enhancements of IgG1 and IgM were seen, but the differences in mean titer were not statistically significant. Non-CpG ODN failed to produce significant enhancements of antibody titers, indicating the presence of a CpG-specific effect. The antibodies detected in this assay were specific for the 19F polysaccharide, since sera from mice immunized with 19F-CRM197 failed to bind the 6B polysaccharide in a 6B-specific ELISA (data not shown). The inclusion of soluble 19F to 19F-coated plates during their incubation with sera competitively inhibited the binding of antibody to the plates, confirming the specificity of the assay. Unimmunized or sham-immunized animals had little or no 19F-specific antibody, and mean titers were zero for all groups of unimmunized mice for all antibody isotypes, consistent with our previously published data (17). These results demonstrate that CpG ODN enhanced anti-19F antibody responses, primarily as a result of significant enhancement of IgG2a and IgG3 responses.

FIG. 1.

CpG ODN enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses after immunization with 19F-CRM197 conjugate vaccine. Groups of six mice were immunized on days 0 and 14 with 19F-CRM197 (approximately 5 μg of polysaccharide equivalent) with or without 100 μg of CpG ODN 1826 or 100 μg of non-CpG ODN 1982 in saline. Serial dilutions of mouse sera obtained on day 28 were assayed by ELISA for anti-19F antibodies, the OD values for the dilutions were used to construct a curve for each mouse, and the anti-19F antibody titer was calculated for each mouse at an OD of 0.5, using two-point curve fit analysis (see Materials and Methods). The geometric mean titer is shown for each group of six mice (error bars indicate SEM); ∗ indicates P < 0.05 compared to immunization with 19F-CRM197 alone. (A) Total anti-19F; (B) anti-19F IgG1; (C) anti-19F IgG2a; (D) anti-19F IgG3; (E) anti-19F IgM. In sera from unimmunized mice, the titers of total anti-19F and all isotypes of anti-19F were <1 (maximum OD < 0.5). These data are representative of three independent experiments of similar design plus three modified related experiments, all of which showed enhancement of anti-19F antibodies by CpG ODN.

When different doses of CpG ODN were compared, 10 μg of CpG ODN 1826/mouse was found to increase anti-19F IgG2a and IgG3 to a modest degree, but titers were increased further (e.g., an additional sixfold increase for anti-19F IgG3) and more significantly by increasing the dose of CpG ODN 1826 to 100 μg/mouse (data not shown). When the dose was increased from 100 to 300 μg of CpG ODN 1826/mouse, anti-19F IgG3 titer did not increase, and there was a less than twofold further increase in anti-19F IgG2a titer. Thus, the dose of adjuvant used for most studies reported in this paper, 100 μg of CpG ODN 1826, provided near-optimal enhancement of anti-19F antibody. Similar enhancement of anti-19F IgG2a and IgG3 was seen with another CpG ODN (ODN 1760 [data not shown]). In contrast, two different control non-CpG ODN (ODN 1982 and ODN 1908) both failed to significantly alter the levels or types of anti-19F antibodies produced (Fig. 1 and data not shown; see Materials and Methods for sequences). These observations indicate that the effects of CpG ODN were specific to the CpG motif.

CpG ODN also enhance antibody responses to a second pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine, 6B-CRM197.

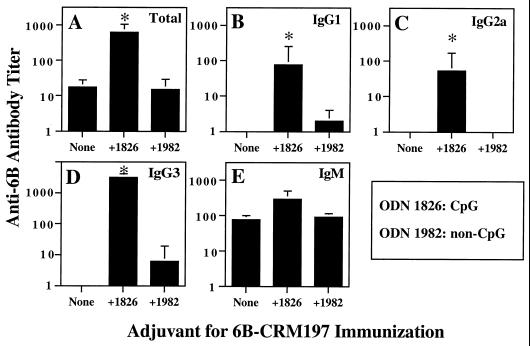

A similar adjuvant effect for antipolysaccharide responses was seen in mice that were immunized twice (days 0 and 14) with a different glycoconjugate vaccine preparation, 6B-CRM197, with or without 100 μg of CpG ODN or non-CpG ODN in saline. As shown in Fig. 2, CpG ODN 1826 significantly enhanced the geometric mean titer of total anti-6B antibody (36-fold increase) in sera collected from mice on day 28. These studies showed particularly marked and significant increases in geometric mean titers of anti-6B IgG2a (54-fold increase) and anti-6B IgG3 (>3,162-fold increase, from <1 to 3,162). Interestingly, significant increases in anti-6B IgG1 were also seen, as BALB/c ByJ mice immunized with 6B-CRM197 alone did not produce detectable levels of anti-6B IgG1 (anti-6B IgG1 titer increased >78-fold, from <1 to 78). Anti-19F IgM titer was increased 3.9-fold by the addition of CpG ODN 1826, but this change was not statistically significant. In contrast to the results with CpG ODN 1826, non-CpG ODN 1982 did not significantly affect the levels or isotype profile of anti-6B antibodies. Unimmunized animals had little or no 6B-specific antibody, consistent with our previously published data (17). Thus, CpG ODN essentially converted BALB/c ByJ mice from anti-6B IgG nonresponders to anti-6B IgG responders for all IgG isotypes that were assessed in these studies. This is consistent with the ability of CpG ODN to enhance isotype switching to different IgG subclasses, including IgG1 and IgG2a, as previously described for protein antigens (7).

FIG. 2.

CpG ODN enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses after immunization with 6B-CRM197 conjugate vaccine. Groups of five mice were immunized on days 0 and 14 with 6B-CRM197 (approximately 5 μg of polysaccharide equivalent) with or without 100 μg of CpG ODN 1826 or 100 μg of non-CpG ODN 1982 in saline. Serial dilutions of mouse sera obtained on day 28 were tested by ELISA for anti-6B antibodies, and titers of anti-6B antibodies were determined as in Fig. 1. (A) Total anti-6B antibody; (B) anti-6B IgG1; (C) anti-6B IgG2a; (D) anti-6B IgG3; (E) anti-6B IgM. The geometric mean titer is shown for each group of five mice (error bars indicate SEM); ∗ indicates P < 0.05 compared to immunization with 6B-CRM197 alone. In sera from unimmunized mice, the titer of total anti-6B and the titers of all isotypes of anti-6B were <1 (maximum OD < 0.5 for ELISA). These data are representative of two independent experiments of similar design using 6B-CRM197.

CpG ODN do not alter the kinetics of the anti-19F antibody response after immunization with 19F-CRM197.

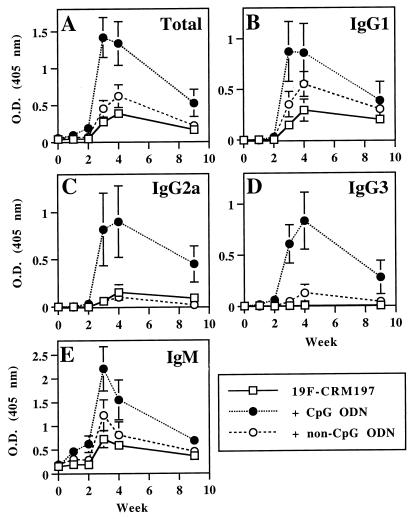

To determine the kinetics of the anti-19F antibody response after treatment with CpG ODN 1826, anti-19F antibodies were measured for up to 9 weeks after immunization on days 0 and 14. As shown in Fig. 3, CpG ODN 1826 did not accelerate the rate of production of anti-19F antibodies, and strong antibody responses of all isotypes were not detected until 1 week after the second immunization. Anti-19F antibody titers declined over time, but CpG ODN-mediated enhancement of total anti-19F antibodies and anti-19F IgG2a and IgG3 was still detectable on day 63, although the statistical significance of the enhancement at this time point varied with isotype. For the differences on day 63 between mice immunized with 19F-CRM197 versus 19F-CRM197 plus CpG ODN 1826, P values were 0.132 for total anti-19F, 0.064 for anti-19F IgG2a, and 0.008 for anti-19F IgG3.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of the anti-19F antibody response after immunization with 19F-CRM197 with or without ODN. Mice were bled on day 0 and then immunized as in Fig. 1. Sera were collected weekly, stored, and then assayed simultaneously at a single dilution. (A) Total anti-19F antibodies (sera assayed at 1:200); (B) anti-19F IgG1 (sera assayed at 1:300); (C) anti-19F IgG2a (sera assayed at 1:200); (D) anti-19F IgG3 (sera assayed at 1:300); (E) anti-19F IgM (sera assayed at 1:50). Each point represents the mean of six mice. Error bars indicate SEM. These data are representative of three independent experiments of similar design.

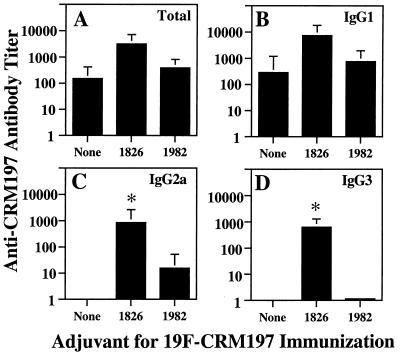

CpG ODN enhance antibodies against the CRM197 carrier protein after immunization with 19F-CRM197.

Anti-CRM197 antibody responses were examined after immunization of mice (on days 0 and 14) with 19F-CRM197. The addition of CpG ODN 1826 significantly enhanced anti-CRM197 IgG2a and IgG3 titers measured on day 28 (Fig. 4). Increases in total anti-CRM197 antibodies and in anti-CRM197 IgG1 were also detected but did not reach statistical significance. As expected, non-CpG ODN 1982 did not increase anti-CRM197 antibodies. Unimmunized animals had little or no CRM197-specific antibody. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating an adjuvant effect of CpG ODN for antibody responses against protein antigens, particularly for enhancement of IgG2a and IgG3 (5, 7, 16, 27).

FIG. 4.

Effect of CpG ODN on anti-CRM197 antibodies after immunization with 19F-CRM197. Groups of five mice were immunized as in Fig. 1. Sera collected on day 28 were assayed for anti-CRM197 antibodies, and antibody titers were calculated as in Fig. 1. The geometric mean titer is shown for each group of five mice (error bars indicate SEM); ∗ indicates P < 0.05 compared to immunization with 19F-CRM197 alone. (A) Total anti-CRM197 antibody; (B) anti-CRM197 IgG1; (C) anti-CRM197 IgG2a; (D) anti-CRM197 IgG3. In sera from unimmunized mice, the titer of total anti-CRM197 and the titers of all isotypes of anti-CRM197 were all <1 (maximum OD < 0.5). These data are representative of three independent experiments of similar design.

DISCUSSION

Current glycoconjugate vaccines for H. influenzae type b require multiple doses to elicit protective antibody titers. In addition, clinical trials with new pneumococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugates have shown variable responses with different polysaccharide serotypes. While glycoconjugate vaccines generate greater antipolysaccharide antibody responses of greater isotype range (mainly IgM and IgG1 in mice) than pure polysaccharide vaccines, further increases in response rate and magnitude and expansion of isotypes are desirable. Thus, it is interesting to explore the possibility that some remaining limitations of glycoconjugate vaccines could be addressed by the inclusion of an adjuvant to enhance their immunogenicity.

The present studies demonstrate that CpG ODN act as adjuvants to increase total antipolysaccharide antibodies after glycoconjugate immunization and also expand isotypes of the antipolysaccharide response. CpG ODN enhanced polysaccharide-specific antibody responses after immunization with either 19F-CRM197 or 6B-CRM197, and CpG-specific enhancement of antibody responses persisted for up to 7 weeks after immunization. CpG ODN increased geometric mean titers of total antipolysaccharide antibodies 23- to 36-fold after immunization with 19F-CRM197 or 6B-CRM197 (Fig. 1 and 2), and particularly significant CpG-associated increases in polysaccharide-specific IgG2a (26- to 54-fold) and IgG3 (>246- to >3,162-fold) were consistently seen. Induction of IgG responses was especially notable in studies with 6B-CRM197. BALB/c ByJ mice did not make 6B-specific IgG when 6B-CRM197 was administered alone (even IgG1 responses were not detected), yet substantial IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG3 anti-6B responses were produced when 6B-CRM197 was administered with CpG ODN. These results indicate that CpG ODN are effective adjuvants for glycoconjugate vaccines that not only elevate antipolysaccharide antibody responses in responders but may also convert IgG nonresponders to IgG responders, a point of potential clinical significance.

CpG ODN provided effective adjuvant activity in mice after two injections with an experimental glycoconjugate vaccine in saline vehicle without additional adjuvant. Additional studies are necessary to optimize the use of CpG ODN, evaluate possible combinations of CpG ODN with other adjuvants, and establish the effectiveness of CpG ODN for use in humans with a multivalent glycoconjugate vaccine. Preliminary studies showed CpG-specific enhancements of antipolysaccharide antibody responses in mice when alum was included in the glycoconjugate vaccine preparation (data not shown). It is possible that the combination of CpG ODN with additional adjuvant components, e.g., alum, may provide longer-lasting CpG-specific increases in antipolysaccharide antibodies and/or long-lasting immunity with fewer injections. Alum is already used to enhance responses to many human vaccines, including the multivalent pneumococcal polysaccharide-CRM197 conjugate vaccine that is being examined in human trials (personal communication from S. Pillai and R. Eby, Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines). In summary, our results establish the principle that CpG ODN can significantly enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses after immunization of mice with a polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine. Future studies are needed to optimize the use of CpG ODN with glycoconjugate vaccines in humans and determine whether CpG ODN can increase titers of antibodies against all pneumococcal polysaccharides in a multivalent glycoconjugate vaccine.

The ability of CpG ODN to expand the antibody isotypes represented in antipolysaccharide responses may have significant functional impact in vivo. Several lines of evidence suggest that IgG2a and IgG3 may be protective during infection with encapsulated bacteria, including pneumococcal infection. In the mouse, IgG2a and IgG3 are highly effective at fixing complement and promoting opsonophagocytosis (6, 8–10, 22), and IgG2a binds to the high-affinity macrophage Fcγ receptor (31). In addition, passively administered IgG3 antibodies directed against pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide type 3 or phosphocholine in the cell wall provide better protection of mice from lethal pneumococcal infection than IgM or IgA (4). These considerations suggest that the changes in antipolysaccharide antibody isotypes and titers that were associated with CpG ODN in these studies may enhance host protection against pneumococcal infection, although the ability of antipolysaccharide antibodies enhanced by CpG ODN to protect against S. pneumoniae infection in an in vivo model or in humans remains to be determined.

As an adjuvant for antipolysaccharide antibody responses to a glycoconjugate vaccine, CpG ODN could influence polysaccharide-specific B cells either directly or indirectly (via enhancement of T-cell help). CpG ODN can mediate direct activation of B cells in vitro, inducing proliferation, antibody production, and isotype switching (7, 14). CpG ODN-mediated increases in antibody secretion in vitro are of greater magnitude when B cells are simultaneously stimulated via surface Ig receptors (14), suggesting a possible role for CpG ODN in augmenting antigen-specific responses. On the other hand, it is likely that the major in vivo effect of CpG ODN on B-cell responses to glycoconjugate vaccines is mediated by increasing carrier-specific Th responses and cytokine secretion to provide increased T-cell help for polysaccharide-specific B cells that present glycoconjugate-derived peptides to T cells. The direct activation of antigen-presenting cells may also increase such Th responses via increased costimulation and/or antigen presentation (3, 11, 25). The importance of enhanced T-cell responses to the adjuvant effect of CpG ODN is supported by preliminary experiments with CpG ODN and unconjugated pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Antibody responses induced by unconjugated pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides were enhanced by CpG ODN to only a minor degree (e.g., a 3-fold enhancement of total anti-19F antibody titer), and CpG-specific enhancement of antipolysaccharide antibody titers was generally about 10-fold less efficient than with glycoconjugate (data not shown). This suggests that CpG-enhanced T-cell help provides the major mechanism for the adjuvant effect of CpG ODN for enhancing antipolysaccharide antibody responses to these glycoconjugate vaccines.

CpG ODN were found to enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses of multiple isotypes, especially after immunization with 6B-CRM197. The enhancement of antipolysaccharide IgG2a and IgG3 antibodies by CpG ODN may be partly explained by indirect effects that are mediated by CpG ODN-induced cytokines. For example, CpG ODN induce IFN-γ, which causes class switching to IgG2a and IgG3 (24). IFN-γ induced by CpG ODN could be secreted by NK cells (stimulated by IL-12 from macrophages activated by CpG ODN) or antigen-specific Th1 cells (specific for carrier protein, e.g., CRM197, in the case of a glycoconjugate vaccine). The development of antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells is enhanced by immunization with CpG ODN and protein antigens (5, 20, 27). In addition, however, CpG ODN have been reported to enhance in vitro isotype switching to IgG1 (with simultaneous exposure of B cells to IL-4) as well as IgG2a (with simultaneous exposure of B cells to IFN-γ) (7). Thus, the effects of CpG ODN do not all follow the simple predictions associated with responses labeled “Th1”, and this may explain the enhancement of anti-6B IgG1 by CpG ODN. Our previous study of the adjuvant function of CpG ODN for immune responses to protein antigen (5) did not reveal enhancement of IgG1 responses by CpG ODN when added to a control vaccine containing incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) because IgG1 responses were already effectively induced by antigen in IFA. IFA was not a component of the vaccines used in this study and is not an adjuvant that is used in humans. In summary, following immunization of mice with a clinically relevant polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine, CpG ODN enhanced responses of multiple IgG isotypes (including IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG3).

The development of effective glycoconjugate vaccines is crucial for the prevention of diseases caused by encapsulated bacteria, and the development of effective adjuvants may have an important impact on this effort. Effective adjuvants could potentially reduce the number of doses needed to establish protective immunity (thereby providing protective immunity within a shorter period and at reduced cost) and provide more uniform effectiveness for the induction of responses to various polysaccharide serotypes. This study demonstrates that CpG ODN significantly enhance antipolysaccharide antibody responses and induce antibody isotypes that may give increased protection against infection. Moreover, under some circumstances, CpG ODN may convert IgG nonresponders to responders for a particular polysaccharide serotype (e.g., 6B in this study), potentially extending the proportion of the population that is effectively protected by a polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine. These findings indicate the importance of future studies in humans to determine the efficacy of CpG ODN as adjuvants for glycoconjugate vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.R.S. and C.V.H. share senior authorship.

We thank Mark Schluchter for statistical analyses, Cindy Brenneman for technical assistance, and Subramanian Pillai and Ronald Eby (Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines, West Henrietta, N.Y.) for generously providing CRM197, 6B-CRM197, and 19F-CRM197. ODN and much valuable advice were provided by Arthur Krieg, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI35726 and AI34343 to C.V.H., AI27862 and AI32596 to J.R.S., and AI41657 to N.S.G. Additional support was provided by a grant from Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines. R.S.C. was supported in part by NIH grant 5T32 GM07250-21.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams W G, Deaver K A, Cochi S L, Plikaytis B D, Zell E R, Broome C V, Wenger J D. Decline of childhood Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease in the Hib vaccine era. JAMA. 1993;269:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson P. Antibody responses to Haemophilus influenzae type b and diphtheria toxin induced by conjugates of oligosaccharides of the type b capsule with the nontoxic protein CRM197. Infect Immun. 1983;39:233–238. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.233-238.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askew D, Chu R, Krieg A, Harding C V. CpG DNA and LPS cause dendritic cell (DC) maturation with distinct effects on nascent and recycling MHC-II antigen processing. FASEB J. 1999;13:A279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briles D E, Claflin J L, Schroer K, Forman C. Mouse IgG3 antibodies are highly protective against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature. 1981;294:88–90. doi: 10.1038/294088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu R, Targoni O S, Krieg A M, Lehmann P V, Harding C V. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper 1 (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1623–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper L J, Schimenti J C, Glass D D, Greenspan N S. H chain C domains influence the strength of binding of IgG for streptococcal group A carbohydrate. J Immunol. 1991;146:2659–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis H L, Weeranta R, Waldschmidt T J, Tygrett L, Schorr J, Krieg A M. CpG DNA is a potent enhancer of specific immunity in mice immunized with recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen. J Immunol. 1998;160:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ey P L, Russell-Jones G J, Jenkin C R. Isotypes of mouse IgG-I. Evidence for “non-complement-fixing” IgG1 antibodies and characterization of their capacity to interfere with IgG2 sensitization of target red blood cells for lysis by complement. Mol Immunol. 1980;17:699–710. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(80)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenspan N S, Cooper L J N. Intermolecular cooperativity: a clue to why mice have IgG3? Immunol Today. 1992;13:164–168. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90120-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenspan N S, Monafo W J, Davie J M. Interaction of IgG3 anti-streptococcal group A carbohydrate (GAC) antibody with streptococcal group A vaccine: enhancing and inhibiting effects of anti-GAC, anti-isotypic, and anti-idiotypic antibodies. J Immunol. 1987;138:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakob T, Walker P S, Krieg A M, Udey M C, Vogel J C. Activation of cutaneous dendritic cells by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides: a role for dendritic cells in the augmentation of Th1 responses by immunostimulatory DNA. J Immunol. 1998;161:3042–3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Käyhty H, Eskola J. New vaccines for the prevention of pneumococcal infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:289–298. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovarik J, Bozzotti P, Love-Homan L, Pihlgren M, Davis H L, Lambert P H, Krieg A M, Siegrist C A. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides can circumvent the Th2 polarization of neonatal responses to vaccines but may fail to fully redirect Th2 responses established by neonatal priming. J Immunol. 1999;162:1611–1617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieg A M, Yi A-K, Matson S, Waldschmidt T J, Bishop G A, Teasdale R, Koretzky G A, Klinman D M. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C-J. Bacterial capsular polysaccharides—biochemistry, immunity and vaccine. Mol Immunol. 1987;24:1005–1019. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(87)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipford G B, Bauer M, Blank C, Reiter R, Wagner H, Heeg K. CpG-containing synthetic oligonucleotides promote B and cytotoxic T cell responses to protein antigen: a new class of vaccine adjuvants. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2340–2344. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCool T L, Harding C V, Greenspan N S, Schreiber J R. B- and T-cell immune responses to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: divergence between carrier- and polysaccharide-specific immunogenicity. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4862–4869. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4862-4869.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mond J J, Lees A, Snapper C M. T cell-independent antigens type 2. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:655–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rennels M B, Edwards K M, Keyserling H L, Reisinger K S, Hogerman D A, Madore D V, Chang I, Paradiso P R, Malinoski F J, Kimura A. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine conjugated to CRM197 in United States infants. Pediatrics. 1998;101:604–611. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roman M, Martin-Orozco E, Goodman J S, Nguyen M D, Sato Y, Ronaghy A, Kornbluth R S, Richman D D, Carson D A, Raz E. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1-promoting adjuvants. Nat Med. 1997;3:849–854. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneerson R, Barrera O, Sutton A, Robbins J B. Preparation, characterization, and immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Exp Med. 1980;152:361–376. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreiber J R, Cooper L J N, Diehn S, Dahlhauser P A, Tosi M F, Glass D D, Patawaran M, Greenspan N S. Variable region-identical monoclonal antibodies of different IgG subclass directed to Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide O-specific side chain function differently. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:221–226. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shinefield H R, Black S, Ray P, Chang I, Lewis N, Fireman B, Hackell J, Paradiso P R, Siber G, Kohberger R, Madore D V, Malnowski F J, Kimura A, Le C, Landaw I, Aguilar J, Hansen J. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal CRM197 conjugate vaccine in infants and toddlers. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1999;18:757–763. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snapper C M, Mond J J. Towards a comprehensive view of immunoglobulin class switching. Immunol Today. 1993;14:15–17. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90318-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparwasser T, Koch E S, Vabulas R M, Heeg K, Lipford G B, Ellwart J W, Wagner H. Bacterial DNA and immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides trigger maturation and activation of murine dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2045–2054. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<2045::AID-IMMU2045>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stacey K J, Sweet M J, Hume D A. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:2116–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun S, Kishimoto H, Sprent J. DNA as an adjuvant: capacity of insect DNA and synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides to augment T cell responses to specific antigen. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1145–1150. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Threadgill D S, McCormick L L, McCool T L, Greenspan N S, Schreiber J R. Mitogenic synthetic polynucleotides suppress the antibody response to a bacterial polysaccharide. Vaccine. 1998;16:76–82. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tygrett L, Wiechert S, Li X, Takahashi K, Krieg A, Waldschmidt T. Capacity of CpG ODN to enhance TNP-Ficoll responses in mice. FASEB J. 1999;13:A990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida T, Pappenheimer A M, Jr, Harper A A. Reconstitution of diphtheria toxin from two nontoxic cross-reacting mutant proteins. Science. 1972;175:901–903. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4024.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unkeless J C, Scigliano E, Freedman V H. Structure and function of human and murine receptors for IgG. Annu Rev Immunol. 1988;6:251–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.06.040188.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vernacchio L, Neufeld E J, MacDonald K, Kurth S, Murakami S, Hohne C, King M, Molrine D. Combined schedule of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1998;133:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Shimada S, Kuramoto E, Yano O, Kataoka T, Tokunaga T. DNA from bacteria, but not from vertebrates, induces interferons, activates natural killer cells and inhibits tumor growth. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:983–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]