Abstract

Bearing on artificial hip joint experiences friction, wear, and surface damage that impact on overall performance and leading to failure at a particular time due to continuous contact that endangers the user. Assessing bearing hip joint using clinical study, experimental testing, and mathematical formula approach is challenging because there are some obstacles from each approach. Computational simulation is an effective alternative approach that is affordable, relatively fast, and more accessible than other approaches in examining various complex conditions requiring extensive resources and several different parameters. In particular, different gait cycles affect the sliding distance and distribution of gait loading acting on the joints. Appropriate selection and addition of gait cycles in computation modelling are crucial for accurate and reliable prediction and analysis of bearing performance such as wear a failure of implants. However, a wide spread of gait cycles and loading data are being considered and studied by researchers as reported in literature. The current article describes a comprehensive literature review adopted walking condition that has been carried out to study bearing using computational simulation approach over the past 30 years. Many knowledge gaps related to adoption procedures, simplification, and future research have been identified to obtain bearing analysis results with more realistic computational simulation approach according to physiological human hip joints.

Keywords: Computational simulation, Human hip joint, Hip joint prosthesis, Hip resurfacing, Total hip arthroplasty, Walking condition

Computational simulation; Human hip joint; Hip joint prosthesis; Hip resurfacing; Total hip arthroplasty; Walking condition.

1. Introduction

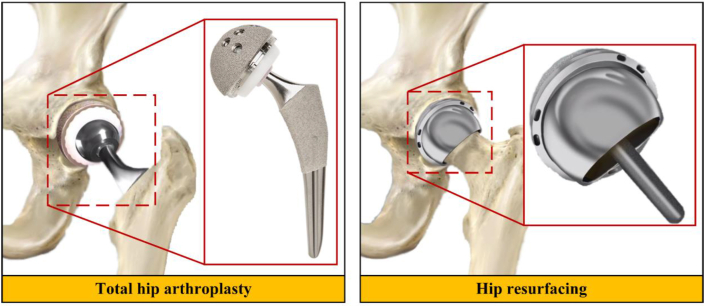

Hip joint replacement is a medical procedure conducting physical replacement of damaged human hip joint with hip joint prosthesis. This surgery has been considered the best option to relieve damage human hip joint to reduce pain, enhance joint functional, and improve life quality of patients [1, 2, 3]. This operation has been performed more than one million times worldwide since 2005 and is expected will be increased until 2030, because many people are getting older who experience various health problems, especially in their hip joints and require medical treatment to carry out normal daily activities as before [4]. There are two procedures in hip joint replacement surgery described in Figure 1, namely total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing [5, 6, 7]. The first procedure involves replacing femur head, femoral stem, and acetabulum cup, while the second procedure does not involve replacing femoral stem with implant component.

Figure 1.

Total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing.

Although hip joint replacement surgery is considered one of the biggest developments in orthopaedics in the last few decades, this operation has not been entirely successfully studied from a mechanical perspective, so it requires further studies. The service life of hip joint prosthesis is generally limited to range of 15 years that does not provide satisfaction for young patients under 60 years of age with longer life expectancy, more than 40% expect implant life to exceed 20 or 25 years [8]. The success of replacement operation depends largely on hip joint implant quality. Therefore, various studies related to artificial hip joints have attempted to improve capabilities, both medical [9] and mechanical [10].

In implant's components, the bearing couple that consist of femoral head and acetabular cup play an essential role as load-bearing and provide movement articulation that continuously in contact for every user's activity [11]. Bearing couples can experience friction, wear, and surface damage affecting overall performance and lead to failure at certain time [12]. For avoid failure of medical implants that could be harmful for patient, various studies in bearing couple have attempted to ensure that implant bearings can last a long time to minimize implant failure or no revision surgery is required in the future [13, 14, 15].

In performing various bearing couple studies on medical implant, four approaches can be used, namely clinical study [16], experimental testing [17], mathematical formula [18], and computational simulation [19]. In the first approach, the method used are radiographic [20], computed tomography [21], and hip analysis suite [22]. Bearing couple studies involving implant users are the most realistic approach of providing valuable results according to actual daily human activities because they are carried out directly under physiological conditions. Unfortunately, without active participation from patients during conducted study, research with this approach could not provide meaningful results. The second approach is achieved by experimental tools, such as hip joint simulator [23], pin-on-disc [24], pin-on-plane [25], ball-on-disc [26], and ball-on-plane [27]. Experimental testing requires sophisticated and high-cost equipment becomes major obstacle for many researchers. The third approach uses analytical mathematical formula based on contact mechanics [28], fluid mechanics [29], and biotribology [30]. Mathematical formulation is the basic concept for many researchers conducting various studies on bearing of hip joint prostheses, but solving realistic problems is very difficult using this approach and is prone to miscalculations because it is done manually or solved numerically.

Computational simulation approach enables to overcome the most common problems found in the first three approaches. This approach carried out by various researchers currently uses finite element method to investigate bearing couple on hip joint arthroplasty with various parameters for further exploration [31, 32, 33]. It is very possible to do, where this approach provides efficiency in time, difficulty, and cost compared to previous three approaches. Analyse using finite element method can also be investigated as preliminary research in assessing various problems. After obtaining results from computational simulation, study can be continued to experimental testing or clinical study approaches [34, 35, 36, 37]. With the current development of software technology, mathematical formula approach has been further developed in finite element-based computational simulation, thus making the current mathematical formula less desirable.

Over the past 30 years, various efforts to develop bearing couples of artificial hip joints by many researchers using computational simulation presented in this review paper have been studied various aspects, such as geometry [38], materials [39], lubrication [40], textured surface [41], and coatings [42]. In computational study of hip joint implant's bearing, two domains can be studied, the first is solid domain representing femoral head and acetabular cup component and the second is fluid domain representing synovial body fluid. The research was conducted by looking for results on solid domain, there are contact pressure [43], wear [44], von Mises stress [45], sliding track [46], heat [47], cross-shear [46], displacement [48], plastic strain [49], Tresca stress [50], creep [51], principal stress [52], and equivalent strain [53]. Furthermore, on fluid domain, there are fluid pressure [41], hydrodynamic pressure [54], film thickness [55], and eccentricities [56]. The results have been obtained through computational simulation approach and then further analysed with various theories, followed by comparisons with rational explanation.

The objective of present review article is to comprehensively summarizes the adoption of walking conditions in previous studies using computational simulations to assess couple bearing in total hip prosthesis and hip resurfacing. The previous literature over the past 30 years (1992–2022) from Scopus database has been collected and further examined to understand adopted walking conditions that have been done using the computational simulation approach. In-depth information about adoption procedures, simplification, and future research has been presented in this review for filling knowledge gaps in the literature.

2. Adopted walking condition for computational simulation approach

Computational simulation based on finite element on bearing of hip joint prosthesis have been attempted to represent how bearing working in actual condition, when used by patient, so this approach can not give significant difference on results from clinical study or experimental testing. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a variety of input data and boundary conditions that are as realistic as possible to achieve results that are closer to actual condition. The use of realistic loading originating from physiological of human hip joint has been carried out in various previous studies by adopting physiological this joint in performing various activities. With rationalization walking is the most common human activity, most realistic loading considered by many researchers to study bearing of hip joint implant is adoption of walking condition [47, 53, 57, 58, 59].

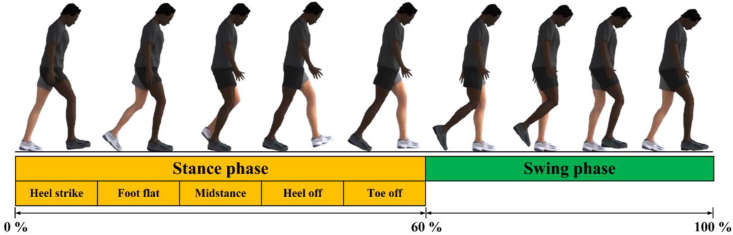

With regards to physiological human hip joint during walking, there are loading and motions that work in three dimensions, shown in Figure 2. Loading acts on x-, y-, and z- axes, which form a resultant force. Also, there are motions from femur relative to pelvis at three degrees of freedom, namely flexion-extension (FE), abduction-adduction (AA), and internal-external rotation (IER). It can be seen that FE moves on x-axis (sagittal plane), IER moves on y-axis (transverse plane), and AA moves on z-axis (coronal plane) [60]. When performing walking condition, movement along three axes is based on time period from heel strike to next heel strike of the same leg, known as cycle [61]. Walking cycle, presented in Figure 3 is divided into two major groups: stance phase (phase where feet come into contact with the ground during walking) and swinging phase (phase where feet swing freely during walking). The stance phase is classified into five sub-phases: heel strike, foot flat, midstance, heel-off, and toe-off [62]. Resultant force that can work received by hip joint depends on body weight and muscle strength estimated to be around three times body weight during walking condition [63]. In this condition, the maximum resultant force is on foot flat and minimal during swing phase [64].

Figure 2.

Loading and motions in human hip joint.

Figure 3.

Phase description in walking cycle. Maximum loading acted on foot flat (stance phase) and minimum loading acted on throughout swing phase.

In adopting walking condition, three components must be considered for computational simulation approach, there are loading, motions, and cycle described in Table 1. Adoption type of loading consists of 3D load, 2D load, 1D load, and static load. Also, motions component consists of FE-AA-IER, FE-AA, FE-IER, and FE. Then, cycle component consists of full cycle, mid-to-terminal stance, stance phase, peak loading, specific conditions, and divided.

Table 1.

Adopted walking condition for computational simulation approach on bearing of hip joint prosthesis.

| Components | Adoption type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Loading | 3D load | Adopted physiological human hip joint loading from x-, y-, and z-axes |

| 2D load | Only adopted human hip joint loading from x- and y-axes | |

| 1D load | Only adopted human hip joint loading from y-axis | |

| Static load | 3D/2D/1D load, but only adopted peak loading/specific condition on cycle | |

| No-load | Not adopted human hip joint loading | |

| Motions | FE-AA-IER | Adopted physiological human hip joint motion on FE, AA, and IER |

| FE-AA | Only adopted human hip joint motion on FE and AA | |

| FE-IER | Only adopted human hip joint motion on FE and IER | |

| FE | Only adopted human hip joint motion on FE | |

| No motion | Not adopted human hip joint motion | |

| Cycle | Full cycle | Adopted full walking cycle |

| Mid-to-terminal stance | Only adopted mid-to-terminal stance under walking cycle | |

| Stance phase | Only adopted stance phase under walking cycle | |

| Peak loading | Only adopted peak loading under walking cycle, also without motion | |

| Specific condition | Only adopted specific phase under walking cycle, also without motion | |

| Divided | Adopted walking cycle (full or partial) divided into many phases |

In general, research flow of computational simulation approach using finite element method on artificial hip joint's bearing under walking conditions is described in Figure 4. First, bearing model of the hip joint implant is made, then finite element discretization is analysed. When input parameters and boundary conditions, adoption of walking conditions is operated according to computational simulation purposes, either according to physiological human hip joint or considering simplification on walking cycle components. Second, computational simulation run to obtain purposes at solid, fluid, or both domains. Lastly, obtained data were studied for further analysis.

Figure 4.

Overview of computational simulation study on bearing of hip joint prosthesis that adopted walking condition.

3. Computational simulation study on bearing of hip joint prosthesis under walking condition

In computational simulation approach to assess bearing on hip joint prosthesis, two aspects affect the results under walking conditions, there are adopted walking condition and walking condition reference. In first aspect, it is divided into simplified and physiological walking conditions. For the second aspect, it is divided into ISO, published literature, and independent measurement. Therefore, it will not be able to get the same simulation results from one researcher to another, even examining same type of hip joint bearing under walking conditions in computational simulation studies. For more detailed, it is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Aspects that affect computational simulation results on bearing of hip joint implant under walking condition.

| Aspect | Adoption type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Adopted walking condition | Simplified walking condition | Using walking condition with simplification from any components in loading, motions, and cycle that not corresponds to physiological human hip joint |

| Physiological walking condition | Adopted walking condition without any simplification from any components in loading, motions, and cycle that corresponds to physiological human hip joint | |

| Walking condition reference | ISO | Using walking condition presented by International Organization for Standardization |

| Published literature | Using walking condition presented by others researchers from published literature | |

| Independent measurement | Using walking condition obtained independently along with conducted computational simulation study |

Over the past 30 years, many researchers have conducted several efforts to develop bearing of hip joint arthroplasty using the finite element method under walking condition. Several computational simulation software selected to conduct finite element analysis, like ANSYS [57], ABAQUS [65], COMSOL Multiphysics [38, 54], MATLAB [44], Adams [66], and AnyBody Modelling System [67]. Both bearings of total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing have been studied, but mostly doing investigations on total hip arthroplasty [68, 69, 70]. Computational studies have been investigated to obtain results, whether on solid, fluid, or both domains. The adopted walking condition has also been observed further along with its components, including loading, motions, and cycle. The detail of computational simulation previous studies on a bearing of hip joint arthroplasty under walking condition adopted from Scopus database over the past 30 years (1992–2022) has been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of detail computational simulation studies on bearing of hip joint prosthesis that adopted walking conditions over the past 30 years.

| Authors | Computational simulation software | Type of hip joint prosthesis | Computational simulation purposes | Adopted walking condition | Walking condition components |

Variation of adopted walking/others condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading |

Motion |

Cycle | ||||||||

| Type | Reference | Type | Reference | |||||||

| Affatato et al. [57] | ANSYS v. 18.1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Damsgaard et al. [71] | FE-AA-IER | Damsgaard et al. [71] | Full cycle | − |

| Ammarullah et al. [59] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Ammarullah et al. [50, 72] | ABAQUS v. 6.14–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Tresca stress | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | |

| Barreto et al. [73] | ABAQUS v. 6.7 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle divided into 28 phases | − |

| Basri et al. [38, 54] | COMSOL Multiphysics v. 4.3b | Total hip arthroplasty | contact pressure, hydrodynamic pressure, and film thickness | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2012 [74] | No motion | − | Full cycle | − |

| Brown et al. [75] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Brand et al. [76] | FE | Brand et al. [76] | Full cycle | − |

| Cilingir [77] | ABAQUS v. 6.9 | Hip resurfacing | Von Mises stress and contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Cilingir et al. [78] | ABAQUS v. 6.5 | Hip resurfacing | Contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [79] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Fialho et al. [47] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, wear, and heat generation | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 28 phases | − |

| Gao et al. [41] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Fluid pressure and film thickness | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Gao et al. [43] | ABAQUS v. 6.12 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Paul [64] | FE-AA-IER | Johnston and Smidt [80] | Full cycle divided into 41 phases | − |

| Gao et al. [56] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Fluid pressure, film thickness, and eccentricities | Simplified and Physiological walking condition | 1D load and 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE and FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle | Walking, stairs up/down, and stand up/sit down |

| Harun et al. [68] | ABAQUS v. 6.53 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | Paul [64] | FE-AA-IER | Johnston and Smidt [80] | Full cycle divided into 20 phases | − |

| Heijink et al. [45] | ABAQUS | Hip resurfacing | Von Mises stress | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Hua et al. [81] | ABAQUS v. 6.9 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and von Mises stress | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Udofia et al. [82] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Jamari et al. [83] | ABAQUS v. 6.14–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Jamari et al. [65, 84] | ABAQUS v. 6.14–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Jourdan and Samida [44] | MATLAB | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Paul [64] | FE-AA-IER | Johnston and Smidt [80] | Full cycle | - |

| Kang et al. [46] | MATLAB v. 7.0 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, sliding track. Cross-shear, and wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Paul [64] | FE-AA-IER | Johnston and Smidt [80] | Full cycle | |

| Krepelka and Toth-Taşcău [70] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Peak loading | Walking and stairs up/down |

| Liu et al. [85] | ABAQUS v. 6.8–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear, contact pressure, and cross-shear | Physiological and simplified walking condition | 1D and 3D load | Johnston and Smidt [80] (3D load), ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] (1D load), and ProSim hip joint simulator [86] (1D load) | FE-AA-IER, FE-AA-IER, and FE-IER | Johnston and Smidt [80], ISO 14242–1:2002 [74], and ProSim hip joint simulator [86] | Full cycle | Three different walking condition from Johnston and Smidt [80], ISO 14242–1:2002 [74], and ProSim hip joint simulator [86] |

| Liu et al. [87] | ABAQUS | Hip resurfacing | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | Leslie et al. [88] | FE-IER | Leslie et al. [88] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Liu et al. [89] | Not mentioned | Hip resurfacing | Film thickness and film pressure | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Liu et al. [90] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Film thickness and hydrodynamic pressure | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | Rieker et al. [91] | FE | Rieker et al. [91] | Full cycle | − |

| Liu et al. [49] | ABAQUS v. 6.11–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and plastic strain | Simplified walking condition | Static load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | No motion | − | Specific condition | Static load under walking condition with magnitude of 0.5 kN and 3 kN |

| Liu et al. [66] | Adams 2013 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE-AA | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Liu et al. [92] | ABAQUS v. 6.8–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, creep and wear | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ProSim hip joint simulator [86] | FE-IER | ProSim hip joint simulator [86] | Full cycle | − |

| Matsoukas and Kim [51] | MATLAB | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, creep, and wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle | Walking and stairs up |

| Maxian et al. [69] | ABAQUS v. 5.3 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Brand et al. [76] | FE | Brand et al. [76] | Stance phase divided into 16 phases | − |

| Maxian et al. [93] | ABAQUS v. 5.3 | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Mejia and Brierly [94] | FE-AA | Mejia and Brierly [94] | Full cycle | − |

| Mellon et al. [95] | MATLAB | Hip resurfacing | Contact pressure | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | independent measurement | Full cycle | Four different adopted motions |

| Meng et al. [48] | ABAQUS v. 6.7–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, displacement, fluid pressure, and film thickness | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | − | FE | Bergmann et al. [63] | Peak loading | − |

| Meng et al. [96] | ABAQUS v. 6.9–1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, film pressure, and film thickness | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Nithyaprakash et al. [97] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, principal stress and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | Normal walking with peak load 2.41 kN, normal walking with peak load 3.327 kN, sitting down/getting up, carrying load 25 kg, carrying load 40 kg, stairs up/down, and ladder up/down (70°) |

| Onisoru et al. [98] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle | Normal walking and stairs up/down |

| Pakhaliuk and Poliakov [99] | ANSYS and MATLAB | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 2D load | ISO 14242–1:2012 [74] | FE-AA-IER | ISO 14242–1:2012 [74] | Full cycle divided into 25 phases | Walking, stairs up/down, standing up/sitting down, and deep squatting |

| Pakhaliuk [100] | ANSYS and MATLAB | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 2D load | ISO 14242–1:2012 [74] | FE-AA-IER | ISO 14242–1:2012 [74] | Full cycle divided into 25 phases | − |

| Patil et al. [101] | Marc | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Brand et al. [76] | No motion | − | Full cycle | − |

| Peng et al. [58] | ABAQUS v. 6.12 | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | independent measurement | FE-AA-IER | independent measurement | Full cycle | − |

| Raimondi [102] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Sutherland et al. [103] | Full cycle | − |

| Ruggiero et al. [67] | AnyBody Modelling System | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | Damsgaard et al. [71] | FE-AA-IER | Damsgaard et al. [71] | Full cycle | − |

| Saputra et al. [104] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and von Mises stress | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Paul [64] | No motion | − | Peak loading | - |

| Shankar et al. [105] | ANSYS v. 14.0 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Shankar et al., [106] | ANSYS v. 14.0 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, von Mises stress, and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Shankar et al. [107] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Shankar et al. [108] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | Walking, lifting 40 kg, carrying 25 kg, stairs down 25 kg, ladder up 70o/90o, and ladder down 70o/90o |

| Suri et al. [109] | COMSOL Multyphysics | Total hip arthroplasty | Fluid pressure, film thickness, and displacement | Simplified walking condition | Static load | − | FE | Gao et al. [41] | Specific condition | − |

| Teoh et al. [110] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Von Mises stress, wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Brand et al. [76] | FE | Brand et al. [76] | Stance phase divided into 16 phases | − |

| Udofia and Jin [40] | ABAQUS v. 5.8–9 | Hip resurfacing | Contact pressure, displacement, film thickness, and film pressure | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Chan et al. [111] | FE | Chan et al. [111] | Full cycle | − |

| Uddin [112] | ANSYS v. 12 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure and von Mises stress | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bennett and Goswami [113] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Uddin and Chan [114] | ANSYS v. 17.1 | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, von Mises stress, and equivalent strain | Simplified walking condition | Static load | − | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Uddin and Zhang [52] | ANSYS | Total hip arthroplasty | Contact pressure, principal stress, and wear | Simplified walking condition | 3D load | Bergmann et al. [63] | FE-AA-IER | Bergmann et al. [63] | Full cycle divided into 32 phases | − |

| Vogel et al. [53] | ABAQUS | Total hip arthroplasty | Displacement and equivalent strain | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Bergmann et al. [115] | No motion | − | Specific condition | − |

| Wang and Jin [55] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Film thickness | Simplified walking condition | 1D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Wang et al. [116] | ABAQUS v. 6.8–1 | Hip resurfacing | Contact mechanics | Simplified walking condition | Static load | Heller et al. [117] | No motion | − | Peak loading | − |

| Wang et al. [118] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Film pressure and fluid pressure | Physiological walking condition | 3D load | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | FE-AA-IER | ISO 14242–1:2002 [74] | Full cycle | − |

| Wu et al. [119] | Not mentioned | Total hip arthroplasty | Wear | Simplified walking condition | 2D load | Saikko et al. [120] | FE | Saikko et al. [120] | Stance phase divided into 16 phases | − |

The adoption of walking conditions in previous studies has been carried out by considering the loading components, both 3D load [75], 2D load [99], 1D load [41], and static load [81]. Simplification is made from the 3D load which considers loading from x-, y-, and z-axes, to only loading from x- and y-axes, or loading from y-axis. While the simplification is carried out by considering loading from the y-axis, the computational simulation results do not change significantly and can be considered a valid simplification. This is because loading from the y-axis dominates the resultant force that works when humans walk.

For the adoption of walking conditions on motion components, previous studies have considered several types, ranging from FE-AA-IER [68], FE [75], and no motion [81]. Simplification of motion components affects the contours location of computational simulation. If the adoption of motion components with FE-AA-IER or FE, then the contours of simulation results can be found to change along with the progress of walking cycle. Meanwhile, if the adoption of motion components with no motion type, the contours of the simulation results are only found in one location along with the progress of walking cycle. It was found that the adoption of motion with FE-AA-IER was all carried out simultaneously with the adoption of loading component with a 3D load so that it could represent walking conditions were close to actual conditions, as performed by Affatato et al. [57], Fialho et al. [47], and Nithyaprakash et al. [97].

Simplification of the cycle for an adopted walking condition has been carried out previously by dividing the walking cycle into 16 [69], 20 [68], 25 [99], 28 [47], 32 [59], and 41 [43] phases. Some do not adopt the full cycle component only by considering a part of the walking cycle in the stance phase as done by Maxian et al. [69], Teoh et al. [110], and Wu et al. [119]. Some studies also only adopted walking condition at specific cycle times during peak loading such as the work of Krepelka and Toth-Taşcău [70], Uddin [112], and Wang et al. [116]. However, some studies adopt the complete cycle component without simplification, an example can be found in Basri et al. [38, 54], Gao et al. [56], and Kang et al. [46].

The simplification of adopted walking condition is also influenced by the finite element model used to study couple bearings. The use of a three-dimensional finite element model allows researchers to adopt physiological walking conditions without any simplification of the loading, motions, and cycle components, as done by Affatato et al. [57], Kang et al. [46], and Mellon et al. [95]. Unfortunately, the use of the axisymmetric finite element model makes the adoption of walking condition to be simplified by not considering the motion component because of the impossibility of adoption, as was done by Ammarullah et al. [50], Jamari et al. [65], and Saputra et al [104]. However, by using a three-dimensional finite element model without axisymmetric simplification, many researchers still simplify the adoption of walking conditions by not considering the motion component that can be found in the literature by Barreto et al. [73], Cilingir [77], and Heiink et al. [45].

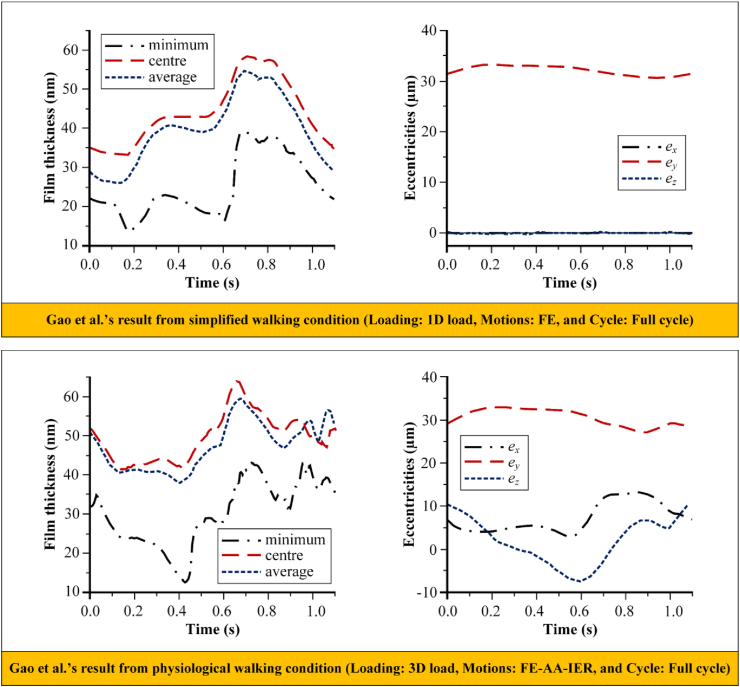

Simplification of adopted walking condition can certainly affect the results of computational simulation. Using walking condition data from Bergmann et al. [63] shown in Figure 5, Gao et al. [56] conducted a study comparing simplified walking condition (Loading: 1D load, Motions: FE, and Cycle: Full cycle) and physiological walking condition (Loading: 3D load, Motions: FE-AA-IER, and Cycle: Full cycle) to analyse hydrodynamic lubrication on metal-on-metal bearing of total hip arthroplasty. Figure 6 shows Gao et al.’s result for film thickness and eccentricities in two different walking gait cycles. It can be seen that there is a significant difference between results from simplified and physiological walking condition. This simplification can be fatal because it can affect data analysis and conclusions drawn by researcher. Computational simulation studies to examine bearing of hip joint implant under walking condition are strongly recommended following physiological human hip joint. If the simplification is necessary, it should be considered as minimal as possible to avoid misinterpretation of the results.

Figure 5.

Walking condition used by Gao et al. [56].

Figure 6.

Gao et al's results from simplified and physiological walking gait cycle [56].

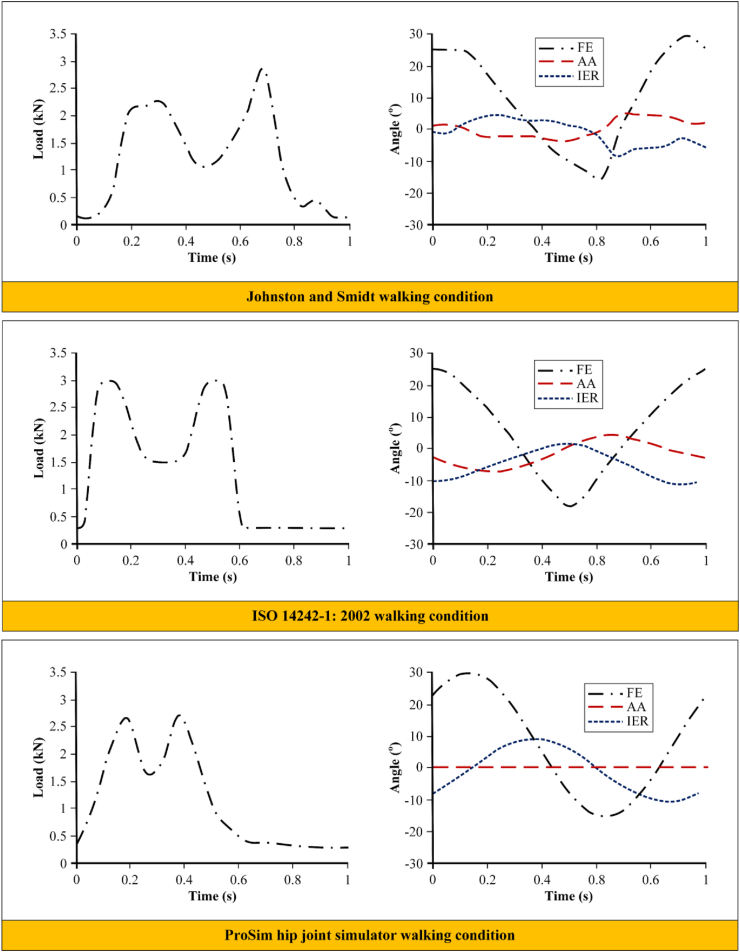

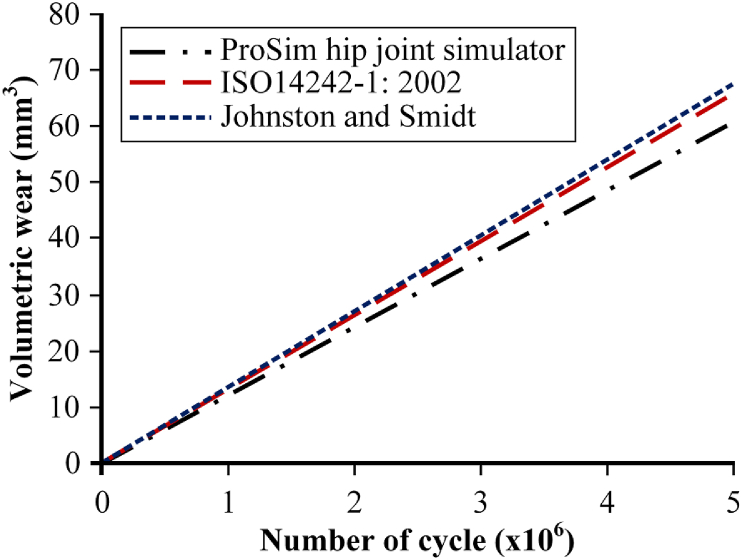

Differences in walking condition reference can also affect the results obtained from computational simulation studies, even though they are both simplified or physiological walking conditions. Liu et al. [85] studied effect of walking condition reference to wear prediction on metal-on-polyethylene bearing of total hip arthroplasty. This research was conducted by adopting walking condition from three different references, respectively from Johnston and Smidt [80], ISO 14242-1: 2002 [74], and ProSim hip joint simulator [86] described in Figure 7. The results indicate that differences in walking condition reference can affect volumetric wear prediction, although not significant, with the highest using walking conditions from Johnston and Smidt, second from ISO 14242-1: 2002 and the lowest from ProSim hip joint simulator. Full description of Liu et al.’s results is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Three different walking condition used by Liu et al. [85].

Figure 8.

Liu et al.’s results from three different walking condition references [85].

4. Research gap and future research

Considering at research on artificial hip joint's bearing over the past 30 years with computational simulation approach, many researchers have used simplified walking condition as described in Table 3, on loading, motions, and cycle components. To provide more realistic computational simulation results according to human hip joint physiological during walking, further studies without simplification need to perform in the future. With the development of hardware technology, hardware for computational simulation will be even better that can be used to analyse various complex situations more realistically, even on low specs, thus simplification of walking condition is not needed.

Walking condition has been adopted by many researchers mostly still using “normal” condition with unspecific subjects [38, 54, 67, 102]. Subject specification is very influential from various aspects, such as abnormal [121], age [122], body mass index [123], gender [124], race/ethnic [125], religion [126], diseases experienced [127], and profession [128]. Adopting walking condition from a specific subject is crucial to the development of artificial hip joint for specific subjects. Research and production of hip joint implants, especially in bearing component, majority carried out in “normal” condition, and less considering specific subjects.

Apart from that, in daily human life, most common activities are walking. However, there are still many other activities, such as sit down/get up [63], load transfer [129], stairs up/down [117], ladder up/down [129], lift [129], carry [129], stumble [130], knee bend [129], stand on 2-1-2 legs [63], sports activities [131], religious activities [126], and other activities. It is also important to investigate the future walking condition to develop bearing on hip joint implant through a simulation approach closer to actual human daily life.

5. Conclusions

Many researchers have conducted several studies in developing bearing of artificial hip joints, both total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing through computational simulation approach using finite element method to avoid various obstacles from clinical study, experimental testing, and mathematical formula. Over the past 30 years, researchers have adopted walking condition to investigate bearing for obtaining results in solid, fluid, or both domains. Unfortunately, to alleviate heavy computational process, various studies have simplified walking conditions, whether on loading, motions, or cycles that can affect the results and lead researchers to misinterpret the results. Adoption of walking conditions of specific subjects needs to be done to develop medical implants for better results so as to minimize implant failures that require revision surgery. Considering other human activities should also be contemplated in conjunction with normal walking to obtain more realistic results.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

The research was supported by World Class Research UNDIP number 118-23/UN7.6.1/PP/2021.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Diponegoro University, Pasundan University, and University of Twente as the author's institutions for their strong support in our present article.

References

- 1.Ammarullah M.I., Afif I.Y., Maula M.I., Winarni T.I., Tauviqirrahman M., Jamari J. Tresca stress evaluation of Metal-on-UHMWPE total hip arthroplasty during peak loading from normal walking activity. Mater. Today Proc. 2022;63:S143–S146. doi: 10.3390/ma14247554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chethan K.N., Zuber M., Bhat N.S., Shenoy S., Kini R.C. Static structural analysis of different stem designs used in total hip arthroplasty using finite element method. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.London Health Sciences Centre . 2013th ed. London Health Sciences Centre; London, England: 2013. My Guide to Total Hip Joint Replacement. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtz S., Ong K., Lau E., Mowat F., Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carreiras A.R., Fonseca E.M.M., Martins D., Couto R. The axisymmetric computational study of a femoral component to analysis the effect of titanium alloy and diameter variation. J. Comput. Appl. Mech. 2020;51:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keele University . 2014th ed. Keele University; Staffordshire, England: 2014. A Guide for People Who Have Osteoarthritis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthritis Research UK . 2011th ed. Arthritis Research UK; Chesterfield, England: 2011. Hip Replacement Surgery- Patient Information. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattei L., Di Puccio F., Piccigallo B., Ciulli E. Lubrication and wear modelling of artificial hip joints: a review. Tribol. Int. 2011;44:532–549. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wainwright T.W., Burgess L.C., Middleton R.G. A feasibility randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a novel neuromuscular electro-stimulation device in preventing the formation of oedema following total hip replacement surgery. Heliyon. 2018;4 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamayo J.A., Riascos M., Vargas C.A., Baena L.M. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy via electron beam melting for the development of implants for the biomedical industry. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamari J., Ammarullah M.I., Santoso G., Sugiharto S., Supriyono T., van der Heide E. In silico contact pressure of metal-on-metal total hip implant with different materials subjected to gait loading. Metals (Basel) 2022;12:1241. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry . 2020th ed. Australian Orthopaedic Association; Adelaide, Australia: 2020. Annual Report 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milone D., Risitano G., Pistone A., Crisafulli D., Alberti F. A new approach for the tribological and mechanical characterization of a hip prosthesis trough a numerical model based on artificial intelligence algorithms and humanoid multibody model. Lubricants. 2022;10:160. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jedrzejczak A., Szymanski W., Kolodziejczyk L., Sobczyk-Guzenda A., Kaczorowski W., Grabarczyk J., et al. Tribological characteristics of a-C:H:Si and a-C:H:SiOx coatings tested in simulated body fluid and protein environment. Materials (Basel) 2022;15:2082. doi: 10.3390/ma15062082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuao Moreu C.A., Cortés D.M., Lara Banda M.D.R., García Sánchez E.O., Robledo P.Z., Rodríguez M.A.L.H. Surface, chemical, and tribological characterization of an astm F-1537 cobalt alloy modified through an ns-pulse laser. Metals (Basel) 2021;11 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hananouchi T., Uchida S., Hashimoto Y., Noboru F., Aoki S.K. Comparison of labrum resistance force while pull-probing in vivo and cadaveric hips. Biomimetics. 2021;6:35. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics6020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su J., Wang J.J., Yan S.T., Zhang M., Wang H.Z., Zhang N.Z., et al. In vitro analysis of wearing of hip joint prostheses composed of different contact materials. Materials (Basel) 2021;14 doi: 10.3390/ma14143805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kebbach M., Schulze C., Meyenburg C., Kluess D., Sungu M., Hartmann A., et al. An mri-based patient-specific computational framework for the calculation of range of motion of total hip replacements. Appl. Sci. 2021;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee H.K., Kim S.M., Lim H.S. Computational wear prediction of TKR with flatback deformity during gait. Appl. Sci. 2022;12:3698. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S.-J., Kim J.-S., Kim W., Kim S.-Y., Lee W.-P. Radiographic and histomorphometric evaluation of sinus floor augmentation using biomimetic octacalcium phosphate alloplasts: a prospective pilot study. Materials (Basel) 2022;15:4061. doi: 10.3390/ma15124061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohamed Thajudeen MZ bin, Mahmood Merican A., Hashim M.S., Nordin A. The utility of lesser trochanter version to estimate femoral anteversion in total hip arthroplasty: a three-dimensional computed tomography study. Surg. Tech. Dev. 2022;11:54–61. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000031398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J., Taylor D., Forst R., Seehaus F. Does pelvic orientation influence wear measurement of the acetabular cup in total hip arthroplasty—an experimental study. Appl. Sci. 2021;11 [Google Scholar]

- 23.St John K.R. Evaluation of two total hip bearing materials for resistance to wear using a hip simulator. Lubricants. 2015;3:459–474. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heuberger R., Bortel E.L., Sague J., Escuder P., Nohava J. Shear resistance and composition of polyethylene protuberances from hip-simulating pin-on-disc wear tests. Biotribology. 2020;23 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamaşag I., Amarandei D., Beşliu I. Design of a device for testing and analyzing the friction coefficient during metal cutting. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019;568 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grabowy M., Wojteczko K., Wojteczko A., Wiązania G., Łuszcz M., Ziąbka M., et al. Alumina-toughened-zirconia with low wear rate in ball-on-flat tribological tests at temperatures to 500 °C. Materials (Basel) 2021;14:7646. doi: 10.3390/ma14247646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichelt M., Cappella B. Comparative analysis of error sources in the determination of wear volumes of oscillating ball-on-plane tests. Front. Mech. Eng. 2020;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q., Zhang Z., Ying Y., Pang Z. Analysis of the dynamic stiffness, hysteresis resonances and complex responses for nonlinear spring systems in power-form order. Appl. Sci. 2021;11:7722. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tso C.P., Hor C.H., Chen G.M., Kok C.K. Fluid flow characteristics within an oscillating lower spherical surface and a stationary concentric upper surface for application to the artificial hip joint. Heliyon. 2018;4 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggiero A., Sicilia A. Mathematical development of a novel discrete hip deformation algorithm for the in silico elasto-hydrodynamic lubrication modelling of total hip replacements. Lubricants. 2021;9:41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chethan K.N., Mohammad Z., Shyamasunder Bhat N., Satish Shenoy B. Optimized trapezoidal-shaped hip implant for total hip arthroplasty using finite element analysis. Cogent Eng. 2020;7:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chethan K.N., Shyamasunder Bhat N., Satish Shenoy B. Biomechanics of hip joint: a systematic review. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018;7:1672–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ammarullah M.I., Santoso G., Sugiharto S., Supriyono T., Kurdi O., Tauviqirrahman M., et al. Tresca stress study of CoCrMo-on-CoCrMo bearings based on body mass index using 2D computational model. Jurnal Tribologi. 2022;33:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attarilar S., Yang J., Ebrahimi M., Wang Q., Liu J., Tang Y., et al. The toxicity phenomenon and the related occurrence in metal and metal oxide nanoparticles: a brief review from the biomedical perspective. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J., Liu J., Attarilar S., Wang C., Tamaddon M., Yang C., et al. Nano-modified titanium implant materials: a way toward improved antibacterial properties. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.576969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramlee M.H., Zainudin N.A., Abdul Kadir M.R. Finite element analysis of different pin diameter of external fixator in treating tibia fracture. Int J Integr Eng. 2021;13:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramlee M.H., Kadir M.R.A., Harun H. Three-dimensional modelling and finite element analysis of an ankle external fixator. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013;845:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basri H., Syahrom A., Prakoso A.T., Wicaksono D., Amarullah M.I., Ramadhoni T.S., et al. The analysis of dimple geometry on artificial hip joint to the performance of lubrication. J Phys Conf Ser. 2019;1198 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J., Zhou P., Attarilar S., Shi H. Innovative surface modification procedures to achieve micro/nano-graded Ti-based biomedical alloys and implants. Coatings. 2021;11:647. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Udofia I.J., Jin Z.M. Elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of metal-on-metal hip-resurfacing prostheses. J. Biomech. 2003;36:537–544. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao L., Yang P., Dymond I., Fisher J., Jin Z. Effect of surface texturing on the elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of metal-on-metal hip implants. Tribol. Int. 2010;43:1851–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q., Zhou P., Liu S., Attarilar S., Ma R.L.-W., Zhong Y., et al. Multi-scale surface treatments of titanium implants for rapid osseointegration: a review. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1244. doi: 10.3390/nano10061244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Y., Jin Z., Wang L., Wang M. Finite element analysis of sliding distance and contact mechanics of hip implant under dynamic walking conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2015;229:469–474. doi: 10.1177/0954411915585380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jourdan F., Samida A. An implicit numerical method for wear modeling applied to a hip joint prosthesis problem. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2009;198:2209–2217. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heijink A., Zobitz M.E., Nuyts R., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Prosthesis design and stress profile after hip resurfacing: a finite element analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. 2008;16:326–332. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang L., Galvin A.L., Brown T.D., Fisher J., Jin Z.M. Wear simulation of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene hip implants by incorporating the effects of cross-shear and contact pressure. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2008;222:1049–1064. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fialho J.C., Fernandes P.R., Eça L., Folgado J. Computational hip joint simulator for wear and heat generation. J. Biomech. 2007;40:2358–2366. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng Q., Gao L., Liu F., Yang P., Fisher J., Jin Z. Contact mechanics and elastohydrodynamic lubrication in a novel metal-on-metal hip implant with an aspherical bearing surface. J. Biomech. 2010;43:849–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu F., Williams S., Fisher J. Effect of microseparation on contact mechanics in metal-on-metal hip replacements - a finite element analysis. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl Biomater. 2015;103:1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ammarullah M.I., Afif I.Y., Maula M.I., Winarni T.I., Tauviqirrahman M., Akbar I., et al. Tresca stress simulation of metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty during normal walking activity. Materials (Basel) 2021;14:7554. doi: 10.3390/ma14247554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsoukas G., Kim I.Y. Design optimization of a total hip prosthesis for wear reduction. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009;131:1–12. doi: 10.1115/1.3049862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uddin M.S., Zhang L.C. Predicting the wear of hard-on-hard hip joint prostheses. Wear. 2013;301:192–200. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogel D., Klimek M., Saemann M., Bader R. Influence of the acetabular cup material on the shell deformation and strain distribution in the adjacent bone-A finite element analysis. Materials (Basel) 2020;13 doi: 10.3390/ma13061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basri H., Syahrom A., Ramadhoni T.S., Prakoso A.T., Ammarullah M.I., Vincent The analysis of the dimple arrangement of the artificial hip joint to the performance of lubrication. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019;620 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang F.C., Jin Z.M. Effect of non-spherical bearing geometry on transient elastohydrodynamic lubrication in metal-on-metal hip joint implants. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J Eng Tribol. 2007;221:379–389. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao L., Wang F., Yang P., Jin Z. Effect of 3D physiological loading and motion on elastohydrodynamic lubrication of metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Med. Eng. Phys. 2009;31:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Affatato S., Merola M., Ruggiero A. Development of a novel in silico model to investigate the influence of radial clearance on the acetabular cup contact pressure in hip implants. Materials (Basel) 2018;11:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ma11081282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng Y., Arauz P., An S., Kwon Y.M. Computational modeling of polyethylene wear in total hip arthroplasty using patient-specific kinematics-coupled finite element analysis. Tribol. Int. 2019;129:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ammarullah M.I., Afif I.Y., Maula M.I., Winarni T.I., Tauviqirrahman M., Bayuseno A.P., et al. Wear analysis of acetabular cup on metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty with dimple addition using finite element method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022;2391 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whittle M.W. fourth ed. Elsevier; 2007. An Introduction to Gait Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ileșan R.R., Cordoș C.-G., Mihăilă L.-I., Fleșar R., Popescu A.-S., Perju-Dumbravă L., et al. Proof of concept in artificial-intelligence-based wearable gait monitoring for Parkinson’s disease management optimization. Biosensors. 2022;12:189. doi: 10.3390/bios12040189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Derlatka M., Bogdan M. Recognition of a person wearing sport shoes or high heels through gait using two types of sensors. Sensors. 2018;18:1639. doi: 10.3390/s18051639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bergmann G., Deuretzabacher G., Heller M., Graichen F., Rohlmann A., Strauss J., et al. Hip contact forces and gait patterns from routine activities. J. Biomech. 2001;34:859–871. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paul J.P. Paper 8: forces transmitted by joints in the human body. Proc Inst Mech Eng Conf Proc. 1966;181:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jamari J., Ammarullah M.I., Santoso G., Sugiharto S., Supriyono T., Prakoso A.T., et al. Computational contact pressure prediction of CoCrMo, SS 316L and Ti6Al4V femoral head against UHMWPE acetabular cup under gait cycle. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022;13:64. doi: 10.3390/jfb13020064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu F., Feng L., Wang J. A computational parametric study on edge loading in ceramic-on-ceramic total hip joint replacements. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018;83:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruggiero A., Merola M., Affatato S. Finite element simulations of hard-on-soft hip joint prosthesis accounting for dynamic loads calculated from a musculoskeletal model during walking. Materials (Basel) 2018;11:574. doi: 10.3390/ma11040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harun M.N., Wang F.C., Jin Z.M., Fisher J. Long-term contact-coupled wear prediction for metal-on-metal total hip joint replacement. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J Eng Tribol. 2009;223:993–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maxian T.A., Brown T.D., Pedersen D.R., Callaghan J.J. A sliding-distance-coupled finite element formulation for polyethylene wear in total hip arthroplasty. J. Biomech. 1996;29:687–692. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krepelka M., Toth-Taşcǎu M. Influence of acetabular liner design on periprosthetic pressures during daily activities. Key Eng. Mater. 2014;601:159–162. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Damsgaard M., Rasmussen J., Christensen S.T., Surma E., Zee M de. Analysis of musculoskeletal systems in the AnyBody modeling System. Simulat. Model. Pract. Theor. 2006;14:1100–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ammarullah M.I., Santoso G., Sugiharto S., Supriyono T., Wibowo D.B., Kurdi O., et al. Minimizing risk of failure from ceramic-on-ceramic total hip prosthesis by selecting ceramic materials based on Tresca stress. Sustainability. 2022;14 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barreto S., Folgado J., Fernandes P.R., Monteiro J. The influence of the pelvic bone on the computational results of the acetabular component of a total hip prosthesis. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010;132:1–4. doi: 10.1115/1.4001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.ISO 14242-1:2002, ISO 14242-1:2012. Implants for Surgery - Wear of Total Hip-Joint Prostheses. Part 1: Loading and Displacement Parameters for Wear-Testing Machines and Corresponding Environmental Conditions for Test N.d.

- 75.Brown T.D., Stewart K.J., Nieman J.C., Pedersen D.R., Callaghan J.J. Local head roughening as a factor contributing to variability of total hip wear : a finite element analysis. J Od Biomech Eng. 2002;124:691–698. doi: 10.1115/1.1517275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brand R.A., Pedersen D.R., Davy D.T., Kotzar G.M., Heiple K.G., Goldberg V.M. Comparison of hip force calculations and measurements in the same patient. J. Arthroplasty. 1994;9:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cilingir A.C. Finite element analysis of the contact mechanics of ceramic-on-ceramic hip resurfacing prostheses. J Bionic Eng. 2010;7:244–253. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cilingir A.C., Ucar V., Kazan R. Three-dimensional anatomic finite element modelling of hemi-arthroplasty of human hip joint. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs. 2007;21:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bergmann G., Graichen F., Rohlmann A. Hip joint loading during walking and running, measured in two patients. J. Biomech. 1993;26:969–990. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90058-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnston R.C., Smidt G.L. Measurement of hip joint motion during walking - evaluation of an electrogoniometric method. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 1969;51:1082–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hua X., Wroblewski B.M., Jin Z., Wang L. The effect of cup inclination and wear on the contact mechanics and cement fixation for ultra high molecular weight polyethylene total hip replacements. Med. Eng. Phys. 2012;34:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Udofia I., Liu F., Jin Z., Roberts P., Grigoris P. Contact mechanics analysis and initial stability of press-fit metal-on-metal hip resurfacing prostheses. Proc World Tribol Congr III - 2005. 2005:627–628. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jamari J., Ammarullah M.I., Saad A.P.M., Syahrom A., Uddin M., van der Heide E., et al. The effect of bottom profile dimples on the femoral head on wear in metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021;12:38. doi: 10.3390/jfb12020038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jamari J., Ammarullah M.I., Santoso G., Sugiharto S., Supriyono T., Heide E van der. In silico contact pressure of metal-on-metal total hip implant with different materials subjected to gait loading. Metals (Basel) 2022;12:1241. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu F., Fisher J., Jin Z. Effect of motion inputs on the wear prediction of artificial hip joints. Tribol. Int. 2013;63:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.triboint.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Galvin A.L., Tipper J.L., Jennings L.M., Stone M.H., Jin Z.M., Ingham E., et al. Wear and biological activity of highly crosslinked polyethylene in the hip under low serum protein concentrations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2007;221:1–10. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu F., Leslie I., Williams S., Fisher J., Jin Z. Development of computational wear simulation of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing replacements. J. Biomech. 2008;41:686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leslie I., Williams S., Brown C., Isaac G., Jin Z., Ingham E., et al. Effect of bearing size on the long-term wear, wear debris, and ion levels of large diameter metal-on-metal hip replacements - an in vitro study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl Biomater. 2008;87:163–172. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu F., Jin Z., Roberts P., Grigoris P. Importance of head diameter, clearance, and cup wall thickness in elastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing prostheses. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2006;220:695–704. doi: 10.1243/09544119JEIM172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu F., Jin Z., Roberts P., Grigoris P. Effect of bearing geometry and structure support on transient elastohydrodynamic lubrication of metal-on-metal hip implants. J. Biomech. 2007;40:1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rieker C.B., Schön R., Konrad R., Liebentritt G., Gnepf P., Shen M., et al. Influence of the clearance on in-vitro tribology of large diameter metal-on-metal articulations pertaining to resurfacing hip implants. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2005;36:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu F., Fisher J., Jin Z. Computational modelling of polyethylene wear and creep in total hip joint replacements: effect of the bearing clearance and diameter. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J Eng Tribol. 2012;226:552–563. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maxian T.A., Brown T.D., Pedersen D.R., McKellop H.A., Lu B., Callaghan J.J. Finite element analysis of acetabular wear: validation, and backing and fixation effects. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1997;111–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mejia L.C., Brierley T.J. A hip wear simulator for the evaluation of biomaterials in hip arthroplasty components. Bio Med. Mater. Eng. 1994;4:259–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mellon S.J., Kwon Y.M., Glyn-Jones S., Murray D.W., Gill H.S. The effect of motion patterns on edge-loading of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Med. Eng. Phys. 2011;33:1212–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meng Q., Liu F., Fisher J., Jin Z. Contact mechanics and lubrication analyses of ceramic-on-metal total hip replacements. Tribol. Int. 2013;63:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nithyaprakash R., Shankar S., Uddin M.S. Computational wear assessment of hard on hard hip implants subject to physically demanding tasks. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2018;56:899–910. doi: 10.1007/s11517-017-1739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Onișoru J., Capitanu L., Iarovici A. Prediction of wear of acetabulum inserts due to multiple human routine activities. Ann Univ “Dunarea Jos” Galati Fascicle VIII 2006. 2006:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pakhaliuk V., Poliakov A. Simulation of wear in a spherical joint with a polymeric component of the total hip replacement considering activities of daily living. Facta Univ. – Ser. Mech. Eng. 2018;16:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pakhaliuk V., Polyakov A., Kalinin M., Kramar V. Improving the finite element simulation of wear of total hip prosthesis’ spherical joint with the polymeric component. Procedia Eng. 2015;100:539–548. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Patil S., Bergula A., Chen P.C., Colwell C.W., D’Lima D.D. Polyethylene wear and acetabular component orientation. J Bone Jt Surg - Ser A. 2003;85:56–63. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300004-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Raimondi M.T., Santambrogio C., Pietrabissa R., Raffelini F., Molfetta L. Improved mathematical model of the wear of the cup articular surface in hip joint prostheses and comparison with retrieved components. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2001;215:377–390. doi: 10.1243/0954411011535966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sutherland D.H., Olshen R., Cooper L., Woo S.L.Y. The development of mature gait. Gait Posture. 1997;6:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Saputra E., Anwar I.B., Jamari J., Heide E Van Der. Reducing contact stress of the surface by modifying different hardness of femoral head and cup in hip prosthesis. Front. Mech. Eng. 2021;7:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shankar S., Siddarth R., Nithyaprakash R., Uddin M.S. Wear prediction of hard carbon coated hard-on-hard hip implants using finite element method. Int. J. Comput. Aided Eng. Technol. 2018;10:440–456. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shankar S., Gowthaman K., Uddin M.S. Combined effect of cup abduction and anteversion angles on long-term wear evolution of PCD-on-PCD hip bearing couple. Int. J. Biomed. Eng. Technol. 2017;24:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shankar S., Nithyaprakash R., Santhosh B.R., Uddin M.S., Pramanik A. Finite element submodeling technique to analyze the contact pressure and wear of hard bearing couples in hip prosthesis. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2020;23:422–431. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2020.1734794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shankar S., Nithyaprakash R., Sugunesh P., Uddin M., Pramanik A. Contact stress and wear analysis of zirconia against alumina for normal and physically demanding loads in hip prosthesis. J Bionic Eng. 2020;17:1045–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Suri M.S.M., Hashim N.L.S., Syahrom A., Latif M.J.A., Harun M.N. Influence of dimple depth on lubricant thickness in elastohydrodynamic lubrication for metallic hip implants using fluid structure interaction (FSI) approach. Malaysian J Med Heal Sci. 2020;16:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Teoh S.H., Chan W.H., Thampuran R. An elasto-plastic finite element model for polyethylene wear in total hip arthroplasty. J. Biomech. 2002;35:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chan F., Medley J., Bobyn J., Krygier J. In: Altern. Bear. Surfaces Total Jt. Replace. Jacobs J., Craig T., editors. ASTM; Philadelphia: 1998. Numerical analysis of time-varying fluid film thickness in metal- metal hip implants in simulator tests. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Uddin M.S. Contact of dual mobility implants: effects of cup wear and inclination. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2015;18:1611–1621. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2014.936856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bennett D., Goswami T. Finite element analysis of hip stem designs. Mater. Des. 2008;29:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Uddin M.S., Chan G.W.C. Reducing stress concentration on the cup rim of hip implants under edge loading. Int j Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2019;35:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cnm.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bergmann G., Bender A., Dymke J., Duda G., Damm P. Standardized loads acting in hip implants. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang L., Williams S., Udofia I., Isaac G., Fisher J., Jin Z. The effect of cup orientation and coverage on contact mechanics and range of motion of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 2012;226:877–886. doi: 10.1177/0954411912456926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Heller M.O., Bergmann G., Deuretzbacher G., Dürselen L., Pohl M., Claes L., et al. Musculo-skeletal loading conditions at the hip during walking and stair climbing. J. Biomech. 2001;34:883–893. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang W.Z., Wang F.C., Jin Z.M., Dowson D., Hu Y.Z. Numerical lubrication simulation of metal-on-metal artificial hip joint replacements: ball-in-socket model and ball-on-plane model. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J Eng Tribol. 2009;223:1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu J.S.S., Hung J.P., Shu C.S., Chen J.H. The computer simulation of wear behavior appearing in total hip prosthesis. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 2003;70:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(01)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Saikko V.O. A three-axis hip joint simulator for wear and friction studies on total hip prostheses. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J Eng Med. 1996;210:175–185. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_410_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Alhossary A., Ang W.T., Chua K.S.G., Tay M.R.J., Ong P.L., Murakami T., et al. Identification of secondary biomechanical abnormalities in the lower limb joints after chronic transtibial amputation: a proof-of-concept study using SPM1D analysis. Bioengineering. 2022;9:293. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering9070293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Espinoza-Araneda J., Bravo-Carrasco V., Álvarez C., Marzuca-Nassr G.N., Muñoz-Mendoza C.L., Muñoz J., et al. Postural balance and gait parameters of independent older adults: a sex difference analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19:4064. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Choi W. Effects of robot-assisted gait training with body weight support on gait and balance in stroke patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19:5814. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Middleton K., Vickery-Howe D., Dascombe B., Clarke A., Wheat J., McClelland J., et al. Mechanical differences between men and women during overground load carriage at self-selected walking speeds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19:3927. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dociak-Salazar E., Barrueto-Deza J.L., Urrunaga-Pastor D., Runzer-Colmenares F.M., Parodi J.F. Gait speed as a predictor of mortality in older men with cancer: a longitudinal study in Peru. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hashim A.Y.B., Osman A., Azuan N., Abas W., Bakar W.A., Abdul Latif L. Analysis of shalat gait. Int. J. Open Probl. Comput. Sci. Math. 2010;3:552–562. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lynch P., Monaghan K. Effects of sensory substituted functional training on balance, gait, and functional performance in neurological patient populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pavei G., Cazzola D., Torre A La, Minetti A.E. Race walking ground reaction forces at increasing speeds: a comparison with walking and running. Symmetry (Basel) 2019;11:873. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Varady P.A., Glitsch U., Augat P. Loads in the hip joint during physically demanding occupational tasks: a motion analysis study. J. Biomech. 2015;48:3227–3233. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Galey L., Gonzalez R.V. Design and initial evaluation of a low-cost microprocessor-controlled above-knee prosthesis: a case report of 2 patients. Prosthesis. 2022;4:60–72. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Palermi S., Annarumma G., Spinelli A., Massa B., Serio A., Vecchiato M., et al. Acceptability and practicality of a quick musculoskeletal examination into sports medicine pre-participation evaluation. Pediatr. Rep. 2022;14:207–216. doi: 10.3390/pediatric14020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.