Abstract

Objectives:

Increased drug overdose mortality among non-Hispanic Black people in the United States in the past 5 years highlights the need for better tailored programs and services. We evaluated (1) changes in drug overdose mortality for various racial and ethnic groups and (2) drug involvement to inform drug overdose prevention efforts in Kentucky.

Methods:

We used Kentucky death certificates and postmortem toxicology reports from 2016-2020 (provisional data) to estimate changes in age-adjusted drug overdose death rates per 100 000 standard population.

Results:

The age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population among non-Hispanic Black residents doubled from 2016 (21.2) to 2020 (46.0), reaching the rate among non-Hispanic White residents in 2020 (48.7; P = .48). From 2016 to 2020, about 80% of these drug overdose deaths involved opioids; heroin involvement declined about 20 percentage points; fentanyl involvement increased about 30 percentage points. The number of psychostimulant-involved drug overdose deaths increased 513% among non-Hispanic Black residents and 191% among non-Hispanic White residents. Cocaine-involved drug overdose deaths increased among non-Hispanic Black residents but declined among non-Hispanic White residents. Drug overdose death rates were significantly lower among Hispanic residents than among non-Hispanic White residents.

Conclusions:

Increased opioid-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black residents in Kentucky in combination with rapidly expanding concomitant psychostimulant involvement require increased understanding of the social, cultural, and illicit market circumstances driving these rapid trend changes. Our findings underscore the urgent need to expand treatment and harm reduction services to non-Hispanic Black residents with substance use disorder.

Keywords: overdose deaths, race and ethnicity, opioids, psychostimulants, HEALing Communities Study

After almost 20 years of increased drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the first decline from 2017 to 2018 (4.1% in the number of drug overdose deaths; 2% in opioid-involved drug overdose deaths). 2 These declines were observed among non-Hispanic White people; however, drug overdose death rates increased among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people, underscoring concerns about growing risks for racial and ethnic minority groups. Furr-Holden and colleagues 3 reported that rates of opioid-involved drug overdose death among African American people began accelerating in 2012 and rose steeply until 2018. Hoopsick et al 4 studied opioid overdose mortality among US adults aged 45-64 years and found that in 2018, non-Hispanic White adults had a higher drug overdose death rate from natural and semisynthetic opioids than non-Hispanic Black adults, but non-Hispanic Black adults had significantly higher rates of heroin and synthetic opioid overdose deaths.

While many studies have focused on opioid-involved overdose deaths, which account for most drug overdose deaths, other studies have focused on stimulant-involved overdose deaths, which have increased sharply since 2013. Some studies attributed the rise in stimulant-involved overdose deaths, in part, to the intentional or unintentional co-involvement of opioids. Kariisa and colleagues reported that most stimulant-involved overdose deaths also involved opioids, with opioid involvement in nearly 72.7% of cocaine-involved overdose deaths and 50.4% of other psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths. 5 A 2021 study that examined stimulant- and opioid-involved overdose deaths in the United States by race and ethnicity for 2017-2018 found that in 2018, the non-Hispanic Black population had the highest age-adjusted rate per 100 000 population of cocaine-involved overdose deaths (9.0), while the non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native population had the highest rate of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths (10.8). 6 Furthermore, for cocaine-involved overdose deaths, 81.6% involved opioids among non-Hispanic White people, while 59.0% involved opioids among non-Hispanic Black people. Co-involvement of opioids in psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths was also greater among non-Hispanic White people (54.2%) than among non-Hispanic Black people (39.6%).

The number of drug overdose deaths climbed again in 2019: of 70 630 drug overdose deaths in the United States, 49 860 (70.6%) involved opioids. 7 The 2019 age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 population among non-Hispanic White people (25.9; 95% CI, 25.7-26.2) was significantly higher than among non-Hispanic Black people (24.5; 95% CI, 24.0-25.0). 1 In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic elevated concerns about the risk of overdose due to isolation, mental health issues, disruptions to substance use treatment, job loss, and other family stressors, along with potential disruptions in the illicit drug market.8-10 CDC reported in December 2020 that the US provisional drug overdose death data indicated the greatest number of drug overdose deaths (>81 000) ever recorded in a 12-month period. 11

Kentucky was one of the first states impacted by the prescription opioid epidemic in the 1990s. In 2019, Kentucky had an age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 population of 32.5, compared with the national average of 21.6, ranking Kentucky seventh highest in the United States.7,12 Kentucky policy makers and public health practitioners have been working tirelessly on drug overdose prevention legislation and program implementation. The largest intervention in Kentucky started in 2019, when 4 states (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio) received funding from the National Institutes of Health for the HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study (HCS), a 5-year, multisite, parallel-group, cluster randomized wait-list controlled trial including 67 communities, with a primary goal to reduce opioid-involved overdose deaths in the intervention communities.13,14 Accurate and timely data, including by race and ethnicity, are used by HCS communities to select and implement evidence-based practices for opioid-involved overdose death prevention.15,16 A recent Kentucky study reported a significant increase in drug overdose death rates from 2019 to 2020 among non-Hispanic Black (57%) and non-Hispanic White (45%) residents. 17

We examined data from 2016-2020 to evaluate drug overdose death trends among racial and ethnic groups and by frequently involved drugs to inform Kentucky’s HCS intervention and other overdose prevention efforts and to provide reference data for other states.

Methods

Data and Measures

This study used data from the Kentucky Drug Overdose Fatality Surveillance System, 18 including electronic death certificate records from the Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics, 2016-2020 (extracted on April 13, 2021; 2020 data are provisional and subject to change), and postmortem toxicology results from the Kentucky Medical Examiners’ Office. We used the race and ethnicity information entered on the death certificate 19 and defined the following racial and ethnic groups: White race with not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (hereinafter, non-Hispanic White), Black or African American race with not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (hereinafter, non-Hispanic Black), other races (eg, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Pacific Islander) with not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (hereinafter, non-Hispanic Other), and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity of any race (hereinafter, Hispanic). We excluded from analyses decedents with unknown information on race or ethnicity (n = 5). Within these groups, we described decedents by age, sex, and residency. We classified counties of residence by (1) Kentucky region: Appalachian versus non-Appalachian, 20 (2) metropolitan (2013 National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS] codes 1-4) versus nonmetropolitan (2013 NCHS codes 5 and 6), 21 or (3) HCS versus non-HCS county; 16 counties were selected for participation in the HCS intervention because of their high age-adjusted rate of opioid-involved overdose deaths (more than 25 per 100 000 standard population, based on 2016 data). 13

We identified drug overdose deaths as death certificates with an underlying cause of death code in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) range of X40-X44, X60-X64, X85, or Y10-Y14.7,22 We used ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes to identify involvement of the following substances: opioids (T40.0-T40.4, T40.6), heroin (T40.1), cocaine (T40.5), psychostimulants (other than cocaine; T43.6), and their concurrent involvement. No explicit ICD-10 code exists for fentanyl-involved poisoning; as such, we analyzed textual information on the death certificate to identify fentanyl or fentanyl analog involvement in drug overdose deaths. 23 In 2016, more than 20% of Kentucky drug overdose death certificates did not list any drugs or drug classes contributing to the overdose death, but by 2020, this percentage declined to <6%.24,25 To avoid bias and underestimation of drug involvement over time, drug overdose death certificates that did not list any drug involvement were supplemented with postmortem toxicology test results. An overdose death involving multiple drugs (eg, heroin and cocaine) was counted under each drug/drug class; thus, reported counts by drug or drug class are not mutually exclusive.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated age-adjusted death rates per 100 000 standard population using STDRATE procedure in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), with direct standardization, and we reported 95% CIs based on gamma distribution.26,27 We also reported the estimated rate ratios (RRs), 95% CIs, and P values for the log RR statistics to compare mortality rates. The denominators of the annual rates for racial and ethnic groups were based on bridged-race annual population estimates of resident Kentucky population. 28 At the time the analysis was performed, the 2020 bridged-race population estimates were not available, and we used the corresponding 2019 estimates to calculate the 2020 drug overdose death rates by race and ethnicity. Because of small counts, we did not report annual rates for the Hispanic and non-Hispanic Other groups. We used 1-way analysis of variance for group mean comparisons, and the Pearson χ2 test for association between 2 categorical variables. Statistical tests were considered significant at P < .05. The HCS protocol was approved by Advarra Inc, the HCS Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 7384 drug overdose deaths among Kentucky residents from 2016 to 2020, classified by race and ethnicity (91.3% non-Hispanic White, 7.1% non-Hispanic Black, 1.3% Hispanic, and 0.4% non-Hispanic Other; Table 1). We found significant variation in the average decedent age by race and ethnicity, ranging from 33.5 years (SD, 7.6) among non-Hispanic Other decedents to 42.5 years (SD, 12.4) among non-Hispanic White decedents. The percentage of males ranged from 61.5% among non-Hispanic Other decedents to 80.0% among Hispanic decedents (P = .002).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Kentucky resident drug overdose deaths (N = 7384), by race and ethnicity, 2016-2020 a

| Characteristic | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 522) | Hispanic (n = 95) | Non-Hispanic Other b (n = 26) | Non-Hispanic White (n = 6741) | P value c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41.2 (13.1) | 38.1 (13.2) | 33.5 (7.6) | 42.5 (12.4) | <.001 |

| Sex | .002 | ||||

| Female | 166 (31.8) | 19 (20.0) | 10 (38.5) | 2459 (36.5) | |

| Male | 356 (68.2) | 76 (80.0) | 16 (61.5) | 4282 (63.5) | |

| Region d | .001 | ||||

| Appalachian | 38 (7.3) | 8 (8.4) | ≤5 | 1915 (28.4) | |

| Non-Appalachian | 484 (92.7) | 87 (91.6) | Suppressed | 4826 (71.6) | |

| Metropolitan status e | .001 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 452 (86.6) | 81 (85.3) | Suppressed | 4302 (63.8) | |

| Nonmetropolitan | 70 (13.4) | 14 (14.7) | ≤5 | 2439 (36.2) | |

| HCS community | <.001 | ||||

| HCS community | 439 (84.1) | 68 (71.6) | 16 (61.5) | 3658 (54.3) | |

| Non-HCS community | 83 (15.9) | 27 (28.4) | 10 (38.5) | 3083 (45.7) | |

| Contributing drugs/drug classes f | |||||

| Opioids | 404 (77.4) | 76 (80.0) | 19 (73.1) | 5534 (82.1) | .03 |

| Cocaine | 186 (35.6) | 15 (15.8) | 6 (23.1) | 573 (8.5) | <.001 |

| Psychostimulants | 105 (20.1) | 13 (13.7) | 9 (34.6) | 2026 (30.1) | .001 |

| Manner of death | .05 | ||||

| Unintentional | 502 (96.2) | 84 (88.4) | Suppressed | 6341 (94.1) | |

| Intentional | 8 (1.5) | Suppressed | ≤5 | 236 (3.5) | |

| Undetermined | 12 (2.3) | ≤5 | 0 | 164 (2.4) | |

Abbreviation: HCS, HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study.

Drug overdose deaths were identified from the Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics death certificate records 18 with an underlying cause of death in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) 22 (range: X40-X44, X60-X64, X85, or Y10-Y14). Data as of April 13, 2021; data for 2020 are provisional and subject to change. Cells with counts between 1 and 5 were suppressed according to the state’s data-reporting policy. When the cell’s original size could be determined by subtraction from the total, the exact number of the next smallest cell was suppressed. All values are number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Includes races other than White or Black (eg, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Pacific Islander) with not Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.

P values for (1) 1-way analysis of variance for comparisons of the average age among racial and ethnic groups or (2) Pearson χ2 test for association between 2 categorical variables. Statistical tests were considered significant at P < .05.

Appalachian versus non-Appalachian status was determined based on the classification information provided by the Appalachian Regional Commission. 20

County of residence was classified based on the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS] Urban–Rural Classification Scheme as metropolitan (2013 NCHS classification codes 1-4) or nonmetropolitan (2013 NCHS classification codes 5 and 6). 21

ICD-10 multiple cause-of-death codes identified involvement of the following substances in drug overdose deaths: opioids (T40.0-T40.4, T40.6), heroin (T40.1), cocaine (T40.5), and psychostimulants (other than cocaine; T43.6). When the death certificate did not list any drugs contributing to the drug overdose death, postmortem toxicology data were used to identify the presence of these substances and counted as involvement of these substances in the drug overdose death. If a death involved 2 or more drugs from different classes, the death was counted under both drug classes (eg, an overdose death with involvement of both fentanyl and cocaine is counted as an opioid-involved and a cocaine-involved overdose death).

The proportion of non-Hispanic White decedents who lived in nonmetropolitan areas (36.2%) or in the Kentucky Appalachian region (28.4%) was significantly higher compared with all other racial and ethnic groups (Table 1). Four of 5 non-Hispanic Black, 71.6% of Hispanic, 61.5% of non-Hispanic Other, and 54.3% of non-Hispanic White decedents were residents of a Kentucky HCS county.

We found a significant difference in the percentage of opioid-involved overdose deaths by race and ethnicity, varying from 73.1% among non-Hispanic Other residents to 82.1% among non-Hispanic White residents (Table 1). Non-Hispanic Black decedents had the highest percentage of cocaine-involved overdose deaths (35.6%). More than 30% of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Other (34.6%) and non-Hispanic White (30.1%) decedents involved other psychostimulants.

We found no significant association between race and ethnicity and manner of death (Table 1). On average, 94.2% of drug overdose deaths were unintentional, 3.4% were intentional (predominantly suicide; ≤5 homicide deaths), and in 2.4% the intent could not be determined.

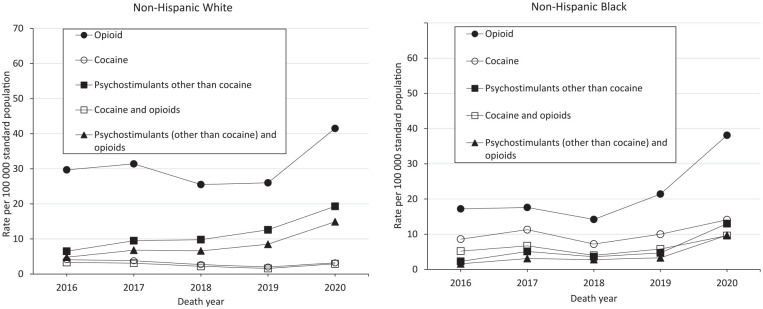

In 2016, the age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population was significantly lower among non-Hispanic Black decedents (21.2) than among non-Hispanic White decedents (35.3; RR = 0.60; P < .001; Table 2). In 2019, the difference in drug overdose death rates among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White decedents was no longer significant (RR = 0.85; P = .13). The annual mortality rate among Hispanic decedents was consistently and significantly lower than the corresponding rate for non-Hispanic White decedents (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population among Kentucky residents (N = 7384), by race and ethnicity and year, 2016-2020 a

| Year | Kentucky, no., rate (95% CI) b | Non-Hispanic Black, no., rate (95% CI) b | Non-Hispanic White no., rate (95% CI) b | Rate ratio c (95% CI) [P value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 1386, 32.7 (40.0-34.5) | 78, 21.2 (16.7-26.8) | 1286, 35.3 (33.4-37.4) | 0.60 d (0.47-0.76) [<.001] |

| 2017 | 1474, 35.0 (33.2-36.9) | 91, 25.7 (20.6-31.9) | 1365, 37.9 (35.9-40.0) | 0.68 (0.54-0.84) [<.001] |

| 2018 | 1249, 29.2 (27.6-30.9) | 76, 19.8 (15.5-25.1) | 1144, 31.6 (29.8-33.5) | 0.63 (0.49-0.79) [<.001] |

| 2019 | 1316, 30.9 (29.3-32.7) | 105, 28.1 (22.8-34.3) | 1187, 32.8 (30.9-34.8) | 0.85 (0.70-1.05) [.13] |

| 2020 | 1959, 46.1 (44.0-48.2) | 172, 46.0 (39.2-53.7) | 1759, 48.7 (46.4-51.1) | 0.94 (0.80-1.11) [.48] |

Data source: Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics death certificate records as part of the Kentucky Drug Overdose Fatality Surveillance System. 18 The number of overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Other and Hispanic residents are included in the total for Kentucky but not reported as separate categories because of small annual counts and unstable rates. The reported counts are provisional (as of April 13, 2021) and subject to change. The 2020 rates are based on 2019 bridged-race population estimates because at the time this analysis was performed, the 2020 bridged-race population estimates produced by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) were not available. Data source for population estimates: NCHS. Bridged-race resident population estimates, 1990-2019. 29

The number of drug overdose deaths, age-adjusted rate per 100 000 standard population, and 95% CI for the age-adjusted rate.

The rate ratio, 95% CI for the rate ratio, and a P value for the log rate ratio statistics that was considered significant if P < .05.

The rate ratio of 0.60 in 2016 means that in 2016, non-Hispanic Black residents had an age-adjusted drug overdose death rate (21.2) that was 40% lower than the rate among non-Hispanic White residents in the same year (35.3).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population among Kentucky residents, by race and ethnicity, 2016-2020. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Data source: Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics death certificate records as part of the Kentucky Drug Overdose Fatality Surveillance System. 18 The reported numbers are provisional (as of April 13, 2021) and subject to change. The 2020 rates are based on 2019 bridged-race population estimates because at the time this analysis was performed, the 2020 bridged-race population estimates produced by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) were not available. Data source for population estimates: NCHS. Bridged-race resident population estimates, 1990-2019. 29

The drug overdose death rates per 100 000 standard population among decedents who were non-Hispanic Black (46.0) and non-Hispanic White (48.7) were comparable in 2020 (RR = 0.94; P = .48). However, the annual percentage increase in age-adjusted drug overdose death rates from 2019 to 2020 was the largest ever recorded in Kentucky: a 48% increase among non-Hispanic White residents (from 32.8 in 2019 to 48.7 in 2020; RR = 1.48; P < .001) and a 64% increase among non-Hispanic Black residents (from 28.1 to 46.0; RR = 1.64; P < .001).

Opioid involvement was reported in >80% of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White residents during the study period (Table 3). The absolute change in the percentage of heroin-involved overdose deaths was a decline of about 20 percentage points from 2016 to 2020. From 2016 to 2020, the percentage of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths increased from 46.2% to 75.6% among non-Hispanic Black residents and from 33.4% to 70.2% among non-Hispanic White residents.

Table 3.

Age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population, number, and percentage of drug overdose deaths among Kentucky residents, by drug involved and race and ethnicity, 2016 and 2020 a

| Involved drug | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 (n = 78) | 2020 (n = 172) | 2016 (n = 1286) | 2020 (n = 1759) | |||||

| Rate | No. (%) | Rate | No. (%) | Rate | No. (%) | Rate | No. (%) | |

| Opioids | 17.2 | 64 (82.1) | 38.1 | 143 (83.1) | 29.7 | 1074 (83.5) | 41.5 | 1484 (84.4) |

| Heroin | 6.7 | 24 (30.8) | 3.6 | 14 (8.1) | 9.1 | 320 (24.9) | 2.7 | 97 (5.5) |

| Fentanyl and fentanyl analogs | 9.5 | 36 (46.2) | 34.5 | 130 (75.6) | 12.4 | 430 (33.4) | 35.1 | 1234 (70.2) |

| Cocaine | 8.6 | 31 (39.7) | 14.1 | 51 (29.7) | 4.1 | 146 (11.4) | 3.2 | 116 (6.6) |

| Psychostimulants (other than cocaine) | — | 8 (10.3) | 13.0 | 49 (28.5) | 6.5 | 232 (18.0) | 19.3 | 676 (38.4) |

| Opioids and cocaine | 5.2 | 19 (24.4) | 9.6 | 34 (19.8) | 3.3 | 117 (9.1) | 2.9 | 106 (6.0) |

| Opioids and psychostimulants (other than cocaine) | — | 6 (7.7) | 9.7 | 37 (21.5) | 4.8 | 168 (13.1) | 14.9 | 510 (29.0) |

Abbreviation: —, rates based on ≤10 events were not calculated.

Data source: Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics death certificate records and postmortem toxicology results from the Kentucky Medical Examiners’ Office, as part of the Kentucky Drug Overdose Fatality Surveillance System. 18 Because of small counts, we did not report annual rates for the Hispanic and non-Hispanic Other groups.

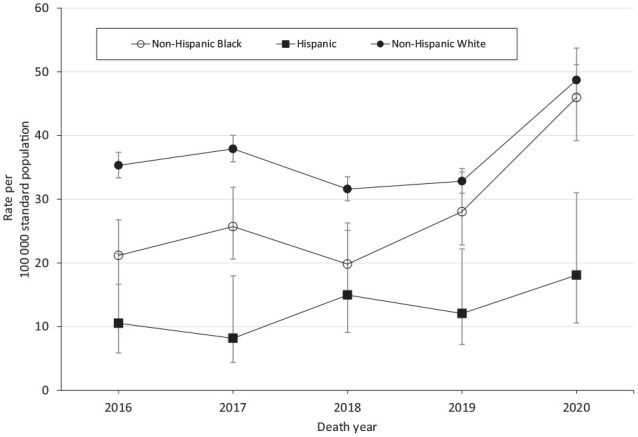

The age-adjusted rate for opioid-involved overdose deaths per 100 000 standard population among non-Hispanic Black residents increased nearly 3-fold from 2018 (14.2) to 2020 (38.1) (Figure 2), mirroring the more than 3-fold increase in the fentanyl-involved overdose death rate (from 9.7 in 2018 to 34.5 in 2020).

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted drug overdose death rate per 100 000 standard population among non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black Kentucky residents, by drug involvement, 2016-2020. Data source: Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics death certificate records as part of the Kentucky Drug Overdose Fatality Surveillance System. 18 The reported data are provisional (as of April 13, 2021) and subject to change. The 2020 rates are based on 2019 bridged-race population estimates because at the time this analysis was performed, the 2020 bridged-race population estimates produced by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) were not available. Data source for population estimates: NCHS. Bridged-race resident population estimates, 1990-2019. 29

The percentage of cocaine-involved overdose deaths declined overall from 2016 to 2020 (Table 3). In 2020, cocaine was involved in 29.7% of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black residents and 6.6% among non-Hispanic White residents. The 2020 rate per 100 000 standard population of cocaine-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black residents (14.1) was more than 4 times higher than among non-Hispanic White residents (3.2; RR = 4.4; P < .001).

The percentage involvement of other psychostimulants (including methamphetamine) increased about 20 percentage points during the study period (non-Hispanic Black, 18.2% increase; non-Hispanic White, 20.4% increase). From 2016 to 2020, the number of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths tripled among non-Hispanic White residents (from 232 to 676, a 191% increase) and increased 512% among non-Hispanic Black residents (from 8 to 49). The rate per 100 000 standard population of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black residents in 2020 (13.0) almost reached the rate of cocaine-involved overdose deaths (14.1).

In 2020, among non-Hispanic Black residents, the percentage of cocaine-involved overdose deaths was 29.7%, the percentage of other psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths was 28.5% (Table 3), but only 4.6% (8 of 172) of drug overdose deaths involved both cocaine and other psychostimulants. Therefore, the co-involvement of other psychostimulants among cocaine-involved overdose deaths was <15.7% (8 of 51). We found a higher co-involvement of cocaine and other psychostimulants among non-Hispanic White decedents in 2020; 37 of 116 (31.9%) cocaine-involved overdose deaths also involved psychostimulants.

The rates of overdose deaths involving opioids and cocaine among non-Hispanic White residents were close to the rates of cocaine-involved overdose deaths. In 2020, 106 of 116 (91.4%) cocaine-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic White residents also involved opioids, compared with 66.7% among non-Hispanic Black decedents. In 2020, the rate per 100 000 standard population of overdose deaths involving opioids and cocaine among non-Hispanic Black residents (9.6) was 3 times higher than among non-Hispanic White residents (2.9; RR = 3.28; P < .001).

In 2020, non-Hispanic Black residents had a significantly lower rate per 100 000 standard population of overdose deaths with concurrent opioid and psychostimulant involvement (9.7) than did non-Hispanic White residents (14.9; RR = 0.65; P = .01). However, the number of overdose deaths with concomitant opioid and psychostimulant involvement among non-Hispanic Black residents increased 208% for just 1 year, from 12 in 2019 to 37 in 2020.

Discussion

We found a significant increase in age-adjusted drug overdose death rates during the study period among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White Kentucky residents. Of great concern is the more than 3-fold increase in the fentanyl-involved overdose death rate among non-Hispanic Black residents during 2018-2020. This increase is larger than the 61%-65% increase in fentanyl-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black people nationwide from 2013 to 2017 reported by Althoff and colleagues. 28

These findings support concerns that the impact of the opioid epidemic in Black communities has not been properly addressed.30,31 Since the late 1990s, age-adjusted opioid-involved overdose death rates have been significantly higher among non-Hispanic White people than among non-Hispanic Black people in the United States.3,32 However, since 2012, opioid-involved overdose death rates have been increasing more steeply among non-Hispanic Black people than among non-Hispanic White people. 3

Our study identified a recent acceleration in non-Hispanic Black drug overdose deaths in Kentucky, leading to comparable rates of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White residents and all-time-high drug overdose death rates among both groups in 2020. Contributors to the steep increase in Kentucky and nationwide likely include the inadequate attention to the crisis in racial and ethnic minority communities 31 and structural inequities in general access to care,33,34 receipt of medications for opioid use disorder,35-37 overdose education and naloxone,38-40 and other harm reduction services.40,41

The rate of psychostimulant-involved overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black Kentucky residents increased 200% from 2019 to 2020 and almost reached the rate of cocaine-involved overdose deaths. A small percentage of overdose deaths involved both cocaine and other psychostimulants. Expanded polysubstance use among non-Hispanic Black residents was reported previously.29,42 Additional analysis of medical history data for decedents with concurrent psychostimulant and opioid involvement may provide information on whether stimulants are reaching a larger proportion of people with opioid use disorder or whether a larger proportion of people with chronic methamphetamine use have been exposed (willingly or unwillingly) to opioids. Nationally, it was reported that non-Hispanic Black people had the highest average annual percentage change in methamphetamine-involved overdose death rates among men during 2011-2018. 43

Fentanyl and its synthetic analogues were the main contributors to drug overdose deaths in Kentucky in 2020, where it was identified as a contributing drug in more than 70% of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black groups.

Considering the unprecedented percentage increase in the number of drug overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black (64%) and non-Hispanic White (64%) residents from 2019 to 2020 in Kentucky, future studies are needed to elucidate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug overdose mortality. Initial evidence suggests that social distancing had a differential impact on drug use, conditional on the drug of choice. 9

Kentucky is 1 of 4 states involved in HCS, the largest community-based intervention study aimed at reducing opioid-involved overdose mortality. 13 The HCS consortium recently released a Statement for Commitment to Racial Equity. 44 The 2020 provisional Kentucky overdose death trends indicated an urgent need to expand programs and find new ways to reach and engage non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations at risk for opioid-involved overdose. One action taken by the Kentucky HCS team in HCS intervention communities was expanding HCS-funded overdose education and distribution of naloxone to people with opioid use disorder who were suddenly being released from jails due to COVID-19. Release from jail is a known risk factor for overdose, 45 and Black people are historically overrepresented in criminal justice populations, largely because of historical disparities in drug-related arrests and inequities in drug sentencing. 31 The HCS team also developed mailing programs for naloxone during the period of social distancing and limited in-person harm reduction activities, expanded efforts for linkage to treatment, and developed a communication campaign in Spanish to address opioid use disorder stigma and provide information on local treatment options.

Conclusions

The profound increases in opioid-involved overdose deaths observed among non-Hispanic Black Kentucky residents in our study, in combination with a rapidly expanding concomitant psychostimulant involvement, require increased understanding of the social, cultural, and illicit market circumstances driving these rapid trend changes. It is recognized in recent years that race as a social construct and racism, rather than biological race, are drivers of health inequity. A better understanding of the aspects of racism (eg, access to mental health services, substance use disorder treatment, peer support and recovery services, stigma, access to training and employment, harm reduction services, safe neighborhoods) as a structural determinant is needed to reduce drug overdose deaths among various racial and ethnic groups. The introduction of competencies in health equity for future public health professionals may be an important step in promoting racial justice and mitigating inequity. 46

The Kentucky HCS will continue its efforts to reach and engage populations at risk for drug overdose in treatment and harm reduction services through culturally tailored interventions and partnership with organizations engaged with Black and Hispanic communities. These efforts will prioritize resources and deploy rapid evidence-based responses in this challenging environment of the opioid and COVID-19 syndemics intertwined with health disparities and stigma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics, Kentucky Department for Public Health, and Kentucky Medical Examiners’ Office for their support for this study, for providing data, and for their comments on data interpretation. The authors also thank Victoria Vessels for technical support.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the NIH HEAL Initiative under award no. UM1DA049406 (Kentucky); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant no. 5NU17CE924971-03, awarded to the Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center in its role of bona fide agent for the Kentucky Department for Public Health; and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under broad agency announcement no. 17-00123, award no. HHSF223201810183C. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or its NIH HEAL Initiative, CDC, or FDA.

ORCID iDs: Svetla Slavova, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4541-6574

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4541-6574

Peter Rock, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9893-4084

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9893-4084

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About multiple cause of death, 1999-2019. 2020. Accessed June 27, 2021. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.htm

- 2. Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith HIV, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furr-Holden D, Milam AJ, Wang L, Sadler R. African Americans now outpace Whites in opioid-involved overdose deaths: a comparison of temporal trends from 1999 to 2018. Addiction. 2021;116(3):677-683. doi: 10.1111/add.15233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoopsick RA, Homish GG, Leonard KE. Differences in opioid overdose mortality rates among middle-aged adults by race/ethnicity and sex, 1999-2018. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(2):192-200. doi: 10.1177/0033354920968806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, Hoots B. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential—United States, 2003-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(17):388-395. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cano M. Racial/ethnic differences in US drug overdose mortality, 2017-2018. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106625. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(394):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Becker WC, Fiellin DA. When epidemics collide: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the opioid crisis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):59-60. doi: 10.7326/m20-1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christie NC, Vojvodic V, Monterosso JR. The early impact of social distancing measures on drug use. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(7):997-1004. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1901934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Uscher-Pines L, Barnett ML, Riedel L, Mehrotra A. Treatment of opioid use disorder among commercially insured patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2440-2442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19: expanded prevention efforts needed [press release]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; December 17, 2020. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose mortality by state. Updated February 12, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm

- 13. Walsh SL, El-Bassel N, Jackson RD, et al. The HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study: protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108335. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walters ST, Chandler RK, Clarke T, et al. Modifications to the HEALing Communities Study in response to COVID-19 related disruptions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;222:108669. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Winhusen T, Walley A, Fanucchi LC, et al. The Opioid-overdose Reduction Continuum of Care Approach (ORCCA): evidence-based practices in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108325. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu E, Villani J, Davis A, et al. Community dashboards to support data-informed decision-making in the HEALing Communities Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108331. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slavova S, Quesinberry D, Hargrove S, et al. Trends in drug overdose mortality rates in Kentucky, 2019-2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116391. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hargrove SL, Bunn TL, Slavova S, et al. Establishment of a comprehensive drug overdose fatality surveillance system in Kentucky to inform drug overdose prevention policies, interventions and best practices. Inj Prev. 2018; 24(1):60-67. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Center for Health Statistics. U.S. standard certificate of death. 2003 revision. Accessed December 3, 2021. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/death11-03final-acc.pdf

- 20. Appalachian Regional Commission. Data reports: socioeconomic data profile by county. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://data.arc.gov/data

- 21. Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2(166):1-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th revision, version 2016. Accessed December 3, 2021. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en

- 23. Davis J, Sabel J, Wright D, Slavova S. Epi tool to analyze overdose death data. Accessed December 3, 2021. http://www.cste.org/blogpost/1084057/211072/Epi-Tool-to-Analyze-Overdose-Death-Data

- 24. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics rapid release: table on improvement of data quality, by state and year. 2020. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/vsrr_drug_datatable.csv

- 25. Warner M, Hedegaard H. Identifying opioid overdose deaths using vital statistics data. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(12):1587-1589. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Fingerhut LA, Warner M, Heinen MA. Deaths: injuries, 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004;52(21):1-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fay MP, Feuer EJ. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stat Med. 1997;16(7):791-801. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Althoff KN, Leifheit KM, Park JN, Chandran A, Sherman SG. Opioid-related overdose mortality in the era of fentanyl: monitoring a shifting epidemic by person, place, and time. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108321. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Center for Health Statistics. Bridged-race population estimates, United States, state and county, for the years 1990-2019. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-population.html

- 30. Stevens-Watkins D. Opioid-related overdose deaths among African Americans: implications for research, practice and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(7):857-861. doi: 10.1111/dar.13058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. James K, Jordan A. The opioid crisis in Black communities. J Law, Med Ethics. 2018;46(2):404-421. doi: 10.1177/1073110518782949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexander MJ, Kiang MV, Barbieri M. Trends in Black and White opioid mortality in the United States, 1979-2015. Epidemiology. 2018;29(5):707-715. doi: 10.1097/ede.0000000000000858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guadamuz JS, Wilder JR, Mouslim MC, Zenk SN, Alexander GC, Qato DM. Fewer pharmacies in Black and Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods compared with White or diverse neighborhoods, 2007-15. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(5):802-811. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wielen LM, Gilchrist EC, Nowels MA, Petterson SM, Rust G, Miller BF. Not near enough: racial and ethnic disparities in access to nearby behavioral health care and primary care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):1032-1047. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979-981. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robbins M, Haroz R, Mazzarelli A, Clements D, 4th, Jones CW, Salzman M. Buprenorphine use and disparities in access among emergency department patients with opioid use disorder: a cross-sectional study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;130:108405. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stein BD, Dick AW, Sorbero M, et al. A population-based examination of trends and disparities in medication treatment for opioid use disorders among Medicaid enrollees. Subst Abuse. 2018;39(4):419-425. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abbas B, Marotta PL, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Socio-ecological and pharmacy-level factors associated with naloxone stocking at standing-order naloxone pharmacies in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;218:108388. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Egan KL, Foster SE, Knudsen AN, Lee JGL. Naloxone availability in retail pharmacies and neighborhood inequities in access. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):699-702. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jones AA, Park JN, Allen ST, et al. Racial differences in overdose training, naloxone possession, and naloxone administration among clients and nonclients of a syringe services program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;129:108412. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cooper HLF, Bossak BH, Tempalski B, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC. Temporal trends in spatial access to pharmacies that sell over-the-counter syringes in New York City health districts: relationship to local racial/ethnic composition and need. J Urban Health. 2009;86(6):929-945. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9399-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nolan ML, Shamasunder S, Colon-Berezin C, Kunins HV, Paone D. Increased presence of fentanyl in cocaine-involved fatal overdoses: implications for prevention. J Urban Health. 2019;96(1):49-54. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-00343-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Han B, Cotto J, Etz K, Einstein EB, Compton WM, Volkow ND. Methamphetamine overdose deaths in the US by sex and race and ethnicity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):564-567. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. National Institutes of Health HEAL Initiative. HEALing Communities Study statement of commitment to racial equity. April 20, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2021.https://healingcommunitiesstudy.org/assets/docs/HCS-Statement-of-Commitment-to-Racial-Equity.pdf

- 45. Mital S, Wolff J, Carroll JJ. The relationship between incarceration history and overdose in North America: a scoping review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108088. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chandler CE, Williams CR, Turner MW, Shanahan ME. Training public health students in racial justice and health equity: a systematic review. Public Health Rep. Published online May 19, 2021. doi: 10.1177/00333549211015665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]