Abstract

A subfield of neuroproteomics, retina proteomics has experienced a transformative growth since its inception due to methodological advances in enabling chemical, biochemical and molecular biology techniques. This review focuses on mass spectrometry’s contributions to advance mammalian and avian retina proteomics to catalog and quantify retinal protein expressions, determine their posttranslational modifications, as well as its applications to study the proteome of the retina in the context of biology, health and diseases, and therapy developments.

Keywords: retina, proteomics, protein expression, posttranslational modifications, photobiology, retinal diseases, estrogenic retina, biomarkers, therapeutic targets

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Retina is considered the window to the brain and is composed of layers of specialized neurons that are interconnected through synapses (London et al., 2013). Therefore, proteomics studies focusing on the retina is a subfield of neuroproteomics, which has not been hitherto widely recognized. Neuroproteomics is defined broadly as the study of proteins that make up the nervous system (Alzate, 2010; Ramadan et al., 2017).

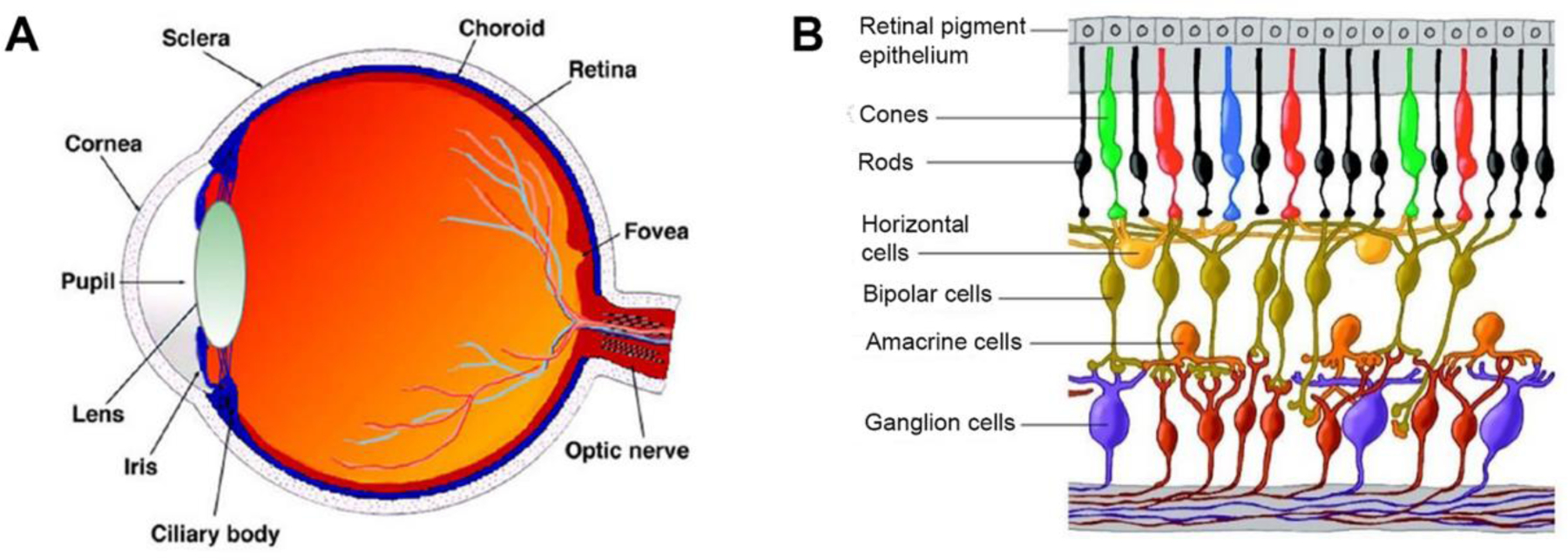

The vertebrate retina contains five different types of neurons arranged in three nuclear and two synaptic layers. In a seminal work, Cajal in the late nineteenth century used Golgi staining in cross-sections of the retina (Cajal, 1893) to discover the existence of retinal layers where the information traversed vertical pathways from photoreceptors of the rods and cones to the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) through bipolar cells and with lateral, horizontal interactions provided by the horizontal and amacrine cells (Bertalmío, 2020). The optic nerve is connected to the brain and contains the RGC axons. The retina occupies the back of the eye (Figure 1A) and the middle is the fovea, the region of highest visual acuity. The radial section of the retina (shown schematically in Figure 1B) reveals that RGCs lie innermost in the retina and closest to the front of the eye, and the photoreceptors (rods and cones) lie in the outermost layer in the retina against the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid. Therefore, light must traverse through the thickness of the retina before reaching and activating the photoreceptors that are responsible for sensory transduction in the visual system. While RPE is the pigmented cell layer outside the neurosensory retina, it is connected the choroid and hence the bloodstream through an extracellular matrix structure called Bruch’s membrane (Strauss, 2016). The RPE has several functions including light absorption, epithelial transport, spatial ion buffering, visual cycle, phagocytosis, secretion, and immune modulation. In addition, three main types of glial cells are found in the mammalian retina that serve to maintain retinal homeostasis: astrocytes, retinal Müller glia (RMG) cells and resident microglia (Vecino et al., 2016). RMG cells span across the retina, and they are considered the major glial component of the tissue involved in its health and diseases (Goldman, 2014).

Figure 1.

Anatomy of the eye and the cellular composition of the retina (Kolb et al., 2005). (A) Vertical sagittal section of the adult human eye; (B) Schematic cross section of the retina.

Proteomics and associated bioinformatics promise to reveal the biological underpinning of various phenomena in living systems. By using these methods in cell cultures, vertebrate animal models and clinical specimens, mass spectrometry-based proteomics has contributed to our understanding of retinal biology, pathology, and pharmacology in systems context. These investigations targeted the identifications of proteins expressed in the retina, revealing posttranslational protein modifications (PTMs), quantitative changes in the retinal proteome due to aging, system development and function, as well as genetic and environmental factors affecting health and diseases. The Human Eye Proteome Project (EyeOME, funded in 2012) focusing on the identification and quantitation of proteins and their variants, their PTMs, as well as protein interactions involved in normal vision and diseases affecting the visual system has also contributed significantly to the evolution of translational retina proteomics (Zhang et al., 2015; Ahmad et al., 2018). Mass spectrometry-based retina proteomics relied on various techniques from combination with two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-GE) to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) that utilize stable isotope-based or label-free quantifications. Affinity-based enrichments, subcellular fractionations, and targeted proteomics were also used in a few focused investigations. Discussion of these techniques was outside the scope of this review; interested readers should consult reviews and protocols broadly available in the scientific literature (e.g., Carette et al., 2005; Hamdan and Righetti, 2003; Wilson et al., 2015; Harsha et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Galarza et al., 2012; Tyanova et al., 2017; Dupree et al., 2020; Kulyyassov et al., 2021) regarding their principles and implementations. The focus of this review is on mass spectrometry’s specific contributions to advance mammalian and avian retina proteomics by cataloging and quantifying retinal protein expression, determining their posttranslational modifications, as well as their applications to study the retinal proteome in the context of biology, health, diseases, and therapy developments.

2 |. MASS SPECTROMETRY-BASED PROTEOMICS TO CATALOG AND MEASURE PROTEIN EXPRESSION IN THE RETINA

Retinal proteomics was ushered in through the application of 2D-GE as the enabling separation method (Matsumoto and Komori, 2000). The limitations of this classical method to resolve only highly abundant and soluble proteins (Rabilloud and Lelong, 2011) also brought about the development of microanalytical techniques permitting, e.g., the isolation of the photoreceptor cell monolayer from bovine retina (Nishizawa et al., 1999). A supplemental feasibility study relying on the excision of protein spots, in-gel tryptic digestion and analyses of peptide mixtures of the proteins by LC–MS/MS or by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF) MS was expected to inspire vision researchers to apply the method in their discovery and identification of proteins expressed specifically or abundantly by photoreceptor cells (Nishizawa et al., 1999). A retinal proteome database using postnatal tissues from chickens, a commonly used animal model in eye research, also has been created by 2D-GE separation followed by the identification of 155 high-abundance proteins through the MALDI-TOF MS-based peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) approach (Lam et al., 2006).

Early studies relying on 2D-GE as a protein separation method used cross-gel 2D-image analysis to pick spots indicating significant changes in stain intensities as the approach to quantitative retina proteomics focusing on the identified proteins (e.g., Sakaguchi et al., 2003; Ethen et al., 2006; Quin et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2012; Bohm et al., 2013). An improvement in the success rate of protein identifications from the retina with this approach was suggested by introducing acid-labile surfactant replacing sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) in the second dimension of the electrophoresis to increase peptide recovery for mass spectrometry after in-gel digestion (König et al., 2003). 2D-GE also was an essential separation method to analyze esterase and transferase activities in the cytosol of the bovine retina by using protein precipitation with ammonium sulfate and a microscale non-denaturing technique that retained enzyme activities (Shimazaki et al., 2004). MALDI-TOF MS-based PMF was complemented by post-source decay (PSD) analysis (Corthals et al., 2000) that enabled protein identifications by sequence tags in this study. In addition, MALDI-MS/MS (TOF/TOF) was also applied recently to identify retina proteins from excised and digested gel spots (Uslubas et al., 2021).

The poor reproducibility of the classical method regarding protein quantifications (Rabilloud et al., 2009; Rabilloud and Lelong, 2011) was addressed through the application of two-dimensional differential in-gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), a technique based on fluorescent labeling (Unlu et al., 1997) to retinal tissues (Zamora et al., 2007; Lam et al., 2007; Miyara et al., 2008; Jostrup et l., 2009; Saraswathy and Rao, 2009; VanGuilder et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2018). 2D-DIGE labels two pools of protein extracts covalently with 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-propylindocarbocyanine halide (Cy3) N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester and 1-(5-carboxypentyl)-1′-methylindodi-carbocyanine halide (Cy5) N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester, respectively. Then, the fluorescence-labeled samples are mixed and separated in the same 2D gel followed by gel imaging using the fluorescence excitation of either the Cy3 or the Cy5 dyes to perform differential protein quantification of the two pools. Nevertheless, the limitations of 2D-GE methods to resolve only highly abundant and soluble proteins at low throughput (Rabilloud and Lelong, 2011) prompted the introduction of additional separation techniques for retina proteomics.

One-dimensional (1D) gel electrophoresis followed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry of the prefractionated and in-gel digested sample (geLC–MS/MS) has been applied to tissue proteomics studies (Vasilj et al., 2012). The technique was used successfully to profile the proteome of melanolipofuscin granules isolated from human RPE (Warburton et al., 2007), to identify a novel neurotrophic factor in cultured primary RMG cell proteins (von Toerne et al., 2014), and even in human retina samples in a clinical study (Sundstrom et al., 2018). Fractionation by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) also was part of the experimental strategy to identify over 2000 proteins in the porcine retina by LC-ESI-MS/MS-based de novo sequencing, albeit three sequential steps of extraction involving different detergents (the non-ionic dodecyl-β-maltoside, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate known as CHAPS and commonly used in 2D-GE protocols, as well as amidosulfobetaine-14 to extract membrane proteins, respectively) were necessary to reach this high protein coverage (Funke et al., 2017).

It also is noteworthy in the context of the retina’s detailed proteomic profiling that the characteristic layered cellular anatomy of the retina also may have to be recognized (Wässle and Boycott, 1991). In addition, the retina is comprised of at least 55 different cell types, which represents a methodological challenge to its meaningful proteomics characterization for some biological studies (McKay et al., 2004). However, the layered cellular anatomy of the organ makes it amenable to planar cross-sectioning (McKay et al., 2004). In a feasibility study, a combination of cryosectioning with LC–MS/MS was applied to a quantitative investigation of the rat outer retina proteome and correlated the distribution profiles of identified proteins with the profiles of marker proteins representing individual compartments of photoreceptors and adjacent cells (Reidel et al., 2011).

Due to the general availability of nanoflow LC systems coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometers, gel-free shotgun methods also have gained acceptance in retina proteomics. After rigorous optimization of sample preparation and instrumental parameters, a single-dimension shotgun strategy with prolonged gradient elution from long nanobore (50 cm × 75 µm i.d., packed with 2-µm particles) reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) columns covered 5,354 protein groups and 56,390 peptides in triplicate analysis, which represented approximately 50% coverage of the expressed proteome with the A375 human melanoma cell line used upon benchmarking the method (Pirmoradian et al., 2013). However, several researchers optimized their shotgun methods applied to increased-throughput retina proteomics by relying on simple sample work-up (Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2013 and 2021; Prokai et al., 2020; Otake et al., 2020), shorter or microbore columns packed with 3-µm particles (Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2013 and 2021; Anders et al., 2017; Funke et al., 2019; Prokai et al., 2020; Otake et al., 2020), and faster gradients (Anders et al., 2017; Suo et al., 2022). On the other hand, the application of filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) has been an example for the importance of enhanced work-up methods to enable in-depth retina proteomics (Ly et al., 2016). FASP combines protein extraction from detergent-solubilized cells and protein mixtures with centrifugal ultrafiltration allowing detergent removal, subsequent protein digestion and isolation of the peptides in a final centrifugation step (Wiśniewski et al, 2018).

Without using stable-isotope labeling methods discussed below, only one report has been published involving the application of two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) for shotgun retina proteomics to catalog retina proteins (Sze et al., 2021). This may be surprising because the power of coupling the orthogonal chromatographic techniques of strong cation exchange (SCX) and reversed-phase (RP) separations recently applied by Sze et al. (2021) has been clearly demonstrated using both offline fractionation as the first dimension (Stevens et al., 2003; Prokai, 2008) and as an online multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) (Washburn et al., 2001) in neuroproteomics upon, e.g., cataloging mammalian brain subproteomes (Cagney et al., 2005; Stevens et al., 2008). High-pH RP fractionation using spin columns developed to increase proteome coverage compared to running unfractionated samples also has been applied recently to C57BL/6 mouse retina in a proteomics study (Sze et al., 2021). This technique employed high-pH buffers to elute peptides bound to the column and convenient collection of fractions by microcentifugation. Then, peptides in the high-pH fractions were further separated by online LC-MS analysis using gradient elution with an acidic (low-pH) mobile phase. The combination of the orthogonal high- and low-pH separations (Yeung et al., 2020) enabled reducing sample complexity and allowed the identification of low abundance retina proteins (Sze et al., 2021). On the other hand, a comparison of 2D-LC–MS/MS results with those obtained from shotgun LC–MS/MS analyses demonstrated that most molecular functions and biological processes were represented via gene ontology (GO) analysis using either methodology (Stevens et al., 2008).

In quantitative retina proteomics relying on shotgun strategies, both stable-isotope labeling and label-free approaches have been applied. Isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT, Gigy et al., 1999) were used first to label peptides differentially for quantitative retina proteomic analyses by LC–ESI-MS/MS (Allison et al., 2006). However, the subsequently introduced derivatization of primary amino groups in intact proteins using isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ, Ross et al., 2004) became the popular approach for quantitative proteomics among the stable-isotope labeling methods in retina proteomics (Yuan et al., 2010; Len et al., 2012; Hollander et al., 2012; Barathi et al., 2014; Danda et al., 2016 and 2018; Santos et al., 2018; Iqbal et al., 2019; Carmy-Bennun, 2021; Feng et al., 2021). The related tandem mass tag (TMT, Thompson et al., 2003) labeling method has also been applied for this purpose (VanGuilder et al., 2011; Mirzaei et al., 2017 and 2020; Deng et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021), while one recent study to identify myopia-regulated proteins in the retinas of myopic chicks (Yu et al., 2020) relied on differential protein tagging of free amino groups with 1-[12C6]nicotinoyloxy-succinimide and 1-[13C6]nicotinoyloxy-succinimide reagents, respectively, as isotope-coded protein label (ICPL) (Schmidt et al., 2005). Stable-isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) followed by geLC–MS/MS was used on primary mouse and porcine RMG cells to identify proteins relevant for pro-survival effects transmitted from these cells to retinal neurons (Hauck et al., 2014; von Toerne et al., 2014), and differential 16O/18O-labeling (Yao et al., 2001) was the choice of relative quantification of retinal protein expression using 2D-LC–MS/MS analyses to determine the molecular risk factors in the ocular hypertensive human retina (Yang et al., 2015). SILAC is relatively straightforward and produces higher reproducibility over other, chemical labeling methods in studies relying on cell cultures (Chen et al, 2015). On the other hand, several experimental protocols involving reagent-based stable-isotope labeling of peptides for relative quantification by shotgun proteomics require fractionation of the labeled sample to remove interfering substances such as excess reagents, by-products of the tagging reactions and buffers, and/or to reduce sample complexity before RPLC–MS/MS analyses (Gygi et al., 1999; Ross et al., 2004; Dayon et al, 2008; Zecha et al., 2019). Altogether, poor cost-efficiency and lack of experimental flexibility have been practical shortcomings of these strategies, especially for tissue proteomics (Vasilj et al., 2012). Therefore, many shotgun retina proteomics studies relied on label-free quantification.

Label-free methods simplify quantitative tissue proteomics by relieving experimental protocols from metabolic or chemical labeling of proteins with stable isotopes (Neilson et al., 2011; Vasilj et al., 2012). Both mass spectral peak intensities (Chelius and Bondarenko, 2002; Wang et al., 2003) and spectral counts (Liu et al., 2004) have been used successfully for quantifying protein abundance changes in shotgun proteomic analyses that rely on data-dependent acquisition (DDA) of MS/MS spectra followed by protein database searches to identify proteins (Eng et al., 1994; Perkins et al., 1999; Batemen et al., 2014). In comparative studies of cultured human cells and microbes, protein ratios determined by spectral counting agreed well with independent measurements based on gel staining intensities (Old et al., 2005) and results from metabolic stable-isotope labeling (Hendrickson et al, 2006), respectively. On high mass accuracy instruments, spectral counting was found to be a robust measure of protein abundance even for samples containing many highly abundant proteins (Hoehenwarter and Wienkoop, 2010). This simple method also compared well to iTRAQ and other, more evolved label-free quantification techniques regarding overall diagnostic classification accuracy for protein expression analyses (Dowle et al., 2016), and several improvements in study design and statistical analyses were recommended to assure its adequate performance for this purpose (Choi et al., 2008; Lundgren et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Gregori et al., 2012; Branson and Freitas, 2016; Lee et al., 2019). Spectral counting was the method of choice to quantify protein abundances in several retina proteomics studies (e.g., Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2013 and 2021; Prokai et al., 2020; Wert et al., 2020).

When applied for quantifying protein abundance changes in shotgun proteomic analyses, mass spectral peak intensities measured in the first (“MS1”) dimension useful for protein quantification showed no saturation effect. Peak area intensity measurements also agreed well with independent measurements based on gel staining intensities (Old et al., 2005). Although spectral counting was a more sensitive method for detecting proteins that undergo changes in abundance, peak area intensity measurements yielded more accurate estimates of protein ratios in a benchmark study (Old et al., 2005). Therefore, the combination of spectral counting and peptide intensity-based quantifications has been proposed to increase the power of label-free shotgun proteomics (Dickler et al., 2010; Goeminne et al., 2020). Programs that utilize peak alignment algorithms, ascertain measurements for a given peptide in runs where the peptide is not identified at the MS/MS level by leveraging information from other runs, and the development of novel intensity determination and normalization procedures (May et al., 2008; Cox et al., 2014) collectively raised the confidence of researchers in label-free quantifications based on MS peak area measurements. The availability of the method in commercial (e.g., Progenesis LC-MS and QI, Proteome Discoverer and Mascot), and in open-source (MaxQant, https://www.maxquant.org) software packages also has contributed to the widespread application of the technique to retina proteomics (Hauck et al., 2010; Ly et al., 2014; Cehofski et al., 2015; Tu et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2017; Eastlake et al., 2018; Ruzafa et al., 2018; Perumal et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Grotegut et al., 2020; Gharbi et al., 2021; Suo et al., 2022—just to mention a few of these studies).

While DDA-based shotgun proteomics has been the method of choice for discovering the maximal number of proteins from one or a few samples, its limited quantification capabilities have been recognized for large sample sets because of stochastic and irreproducible precursor ion selections (Liu et al., 2004) and under-sampling (Michalski et al., 2011). In targeted proteomics, a sample is queried for the presence and quantity of a limited set of peptides that must be specified prior to data acquisition (Lange et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010; Kiyonami et al., 2011; Kulyyassov et al., 2021), which results in improvement of quantitative accuracy and poses no limitations about sample numbers included in a study. Therefore, these assessments have become the preferred approach to validate results of discovery-driven quantitative proteomics for a selected set of proteins through assaying their proteotypic peptides by the bottom-up strategy (Aebersold et al., 2013). The classical LC–MS/MS method that relies on selected reaction monitoring (SRM) using triple quadrupole or hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap tandem mass spectrometers (Lange et al., 2008) has been applied to the retina in this context (Kwong et al., 2021). Development of a bottom-up LC–SRM-based assay also was reported to quantify an isoform of cytochrome P450 (CYP11A1) and adrenodoxin reductase in retinae using their 15N-labeled recombinant isotopologues as internal standards (Liao et al., 2010). On the other hand, few targeted retina proteomics studies (Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2021; Suo et al., 2022) have employed the more and more popular parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) on hybrid orbital trap tandem mass spectrometers (Gallien et al., 2014; Rauniyar, 2015; Kulyyassov et al., 2021). The technique leverages the benefits of targeted MS/MS acquisitions at high resolution and high accuracy for both stable isotope label-based and label-free quantifications by the bottom-up approach, albeit unit resolution linear ion trap-based PRM have shown similar technical precision and superior sensitivity for over 62% of peptides in the assay in a recent benchmark study (Heil et al., 2021). Targeted solid-phase extraction (SPE) combined with MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS has also been applied to verify label-free quantification for a selected subset of proteins in the porcine retina and optic nerve head in conjunction with a shotgun proteomics study (Funke et al., 2019).

DIA was developed to address the shortcomings of the DDA and limitations of the targeted proteomics approach to detect and quantify large fractions of proteomes across multiple samples rapidly, consistently, reproducibly, accurately, and sensitively (Silva et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Gillet et al., 2012; Bond et al., 2013; Ludwig et al., 2018). In the MSE method, the (usually TOF) mass spectrometer cycles in quick successions between two settings: first transmitting all ions from the ion source through a collision cell held at low collision energy so that no fragmentations occur, then the collision cell is ramped to high collision energy to generate fragment ions ([White Paper], 2011). An algorithm designed to analyze these MSE acquisitions deciphers retention time, ion intensities, charge state, and accurate masses of both precursor and product ions from LC-MS data (Li et al., 2009). Hybrid instruments capable of incorporating ion mobility separation into MS analyses also allow acquisition of so-called high definition MSE data (HDMSE), which enables deeper proteome coverage and more confident peptide identifications when compared to MSE (Bond et al., 2013). However, the latter offers a higher dynamic range for quantitation. MSE has been used for measuring changes in retinal protein expression following unilateral optic nerve transection and early experimental glaucoma in non-human primate eyes through comparisons to peptides of a pre-digested protein added to the samples as an internal standard (Stowell et al., 2011). Both DDA and MSE were used to generate peptide identifications focused on revealing glycolytic specializations of photoreceptor cells by LC–MS/MS, which was enabled through cryosectioning the rat outer retina (Reidel et al., 2011).

An alternative DIA approach applied to retina proteomics has been the sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra (SWATH), which includes sequential selection of relatively large precursor ion mass windows, fragmentation of all precursor ions in each window, and recording of the combined fragment ion spectra (Gillet et al., 2012; Ludwig et al., 2018). When applied with online LC separation, SWATH-MS creates a time-resolved fragment ion map of all ionized precursor ions present, and peptides are identified by extraction of signal groups corresponding to their fragment ion signals by computing the likelihood that a particular signal group represents the targeted peptides (Shao et al., 2015). In addition, peptides can be quantified through automated data analyses with consistency and accuracy comparable with that of SRM (Gillet et al., 2013; Röst et al., 2017). Therefore, SWATH-MS has become an emerging methodology introduced into several recent retina proteomics studies focused on oxygen-induced retinopathy in mouse (Vähätupa et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2022), identification of differentially expressed proteins in the retinal emmetropization process in guinea pig (Shan et al., 2018), creation of spectral library of proteins for the normal C57BL/6 mouse retina (Sze et al., 2021), revealing the significance of lipid metabolism in myopic guinea pig retina (Bian et al., 2021), detecting and quantifying regional changes of retinal protein expressions after optic nerve injury in rats (Kwong et al., 2021), as well as proteomic analysis of retinal tissue in an S100B autoimmune glaucoma model (Reinehr et al., 2021).

3 |. DETECTION AND IDENTIFICATION OF POSTTRANSLATIONAL PROTEIN MODIFICATIONS OF RETINAL PROTEINS BY MASS SPECTROMETRY

Initially, survey of PTMs of retina proteins by mass spectrometry focused on a few target proteins. For example, recoverin (a calcium-binding protein of vertebrate rod photoreceptors) and the catalytic subunit of CAMP-dependent protein kinase were found to be modified at its amino-terminus through heterogeneous acylation by myristate (C14:0) and related acyl groups (C14:1, C14:2 and C12:0) using LC–ESI-MS/MS analyses after purification of the proteins from human and bovine retinas (Johnson et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 1997), while frog transducin was homogenously modified with the doubly unsaturated C14:2 fatty acyl group (Johnson et al., 1994).

Multiple sites of rhodopsin phosphorylations were identified from the protein’s carboxy-terminal proteolytic fragment from bovine (Papac et al., 1993; Ohguro et al., 1993 and 1994), mouse (Hurley et al., 1998) and light-damaged rat retinae (Ablonczy et al., 2000) by ESI-MS/MS. In addition, the utility of positive and negative modes of ESI to produce precursor ions for MS/MS via low-energy CID also were explored using mono- and diphosphorylated synthetic peptide analogs of proteolytic fragments from the carboxy-terminal region of rhodopsin (Busman et al., 1996). Overall, positive-ion ESI-MS/MS spectra from different charge state precursor ions were sufficient to assign phosphorylation sites in most cases, albeit obtaining complementary information by fragmenting negative ions was recommended. Glycosylation and palmitylation also were confirmed by MALDI-TOF analyses of the protein’s cyanogen bromide (CNBr) fragments (Ablonczy et al., 2000).

Relying on MALDI-TOF and online LC–ESI-MS/MS after purification of the analyte from 2D-GE spots, the small heat shock protein αA-crystallin (CRYAA) was found to undergo age-associated oxidation, phosphorylation, deamidation, acetylation, and truncation in the rat sensory retina (Kapphahn et al., 2003). In another study, CRYAA also resolved into multiple 2D-GE spots reflecting changes in intrinsic charge due to PTMs in the rat retina upon intraocular injections of sex steroids (D’Anna et al., 2011).

ABCA4, a photoreceptor-specific adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette transporter, revealed seven N-glycosylation sites in the exoplasmic domain upon investigating the native protein purified from bovine outer rod segments by LC–ESI-MS/MS analyses of proteolytic peptides treated with PNGase F (Tsybovky et al., 2011). The modifying oligosaccharides were found to be relatively short and homogeneous, predominantly representing a high-mannose type of N-glycosylation. In addition, five phosphorylated residues in the cytoplasmic domain of the protein were detected after phosphopeptide enrichment by TiO2 chromatography.

Cytochrome P450 27A1 (CYP27A1) is a multifunction enzyme in the metabolism of cholesterol and other sterols. This protein was found to be modified at its Lys358 residue with the arachidonate oxidation products isolevuglandins (isoLGs) in human retina afflicted with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) based on targeted quantitative LC–ESI-MS/MS analyses relying on multiple reaction monitoring of the isoLG-modified tryptic peptide (Charvet et al., 2011). A follow-up in vitro study using an E. coli model system also confirmed modifications of wild-type and mutant CYP27A1 by the product of retinal lipid oxidation (Charvet et al., 2013).

Sirtuin 6 (Sirt6, a site-specific histone deacetylase) was shown to undergo posttranslational tyrosine (Tyr) nitration, as well as methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp) oxidation in cell culture and in a mouse model of endotoxin-induced retinal inflammation (Hu et al., 2015). The tryptic peptides showing the nitration of Tyr257 and multiple sites of Met and Trp oxidation in the protein was identified by LC–ESI-MS/MS-based shotgun proteomics.

Most of the above finding from mass spectrometry-based studies on PTMs of selected retinal proteins were implicated in regulating their functions. For example, phosphorylation/dephosphorylation plays a key role in rhodopsin signaling of the photoreceptor cells (Gurevich et al., 2011). Acylation was found to affect recoverin’s binding affinity of Ca2+ (Johnson et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 1997) and proposed to regulate the visual transduction cascade (Zand and Neuhauss, 2019), while CRYAA phosphorylation could affect its chaperone function that prevent retinal protein aggregation due to oxidative stress (Kapphahn et al., 2003; Nath et al., 2021). ABCA4 is a key protein in the clearance of all-trans-retinal produced in the retina during light perception (Tsybovki et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2021b). CYP27A1 is involved in the metabolism of excess cholesterol (Petrov et al., 2019) and loss of its activity potentially contributes to the pathological neovascularization of the retina (Saadane et al., 2016). Sirt6 regulates chromatin structure in RMG cells as an epigenetic modulator and has been linked to metabolic changes during retinal diseases (Salas et al., 2021).

Despite encouraging results from mass spectrometry-based investigations focusing on these few target proteins, proteome-wide exploration PTMs in the retina has received limited attention. Nevertheless, several proteomics studies not directed to identification of PTMs by experimental design have noted modifications. The separation of the protein along the acidic-to-basic axis suggested post-translational modifications confirming the presence of several isoelectric point (pI) isoforms of phosducin in the mouse retina (Hauck et al., 2006). As mentioned above, CRYAA resolved into multiple 2D-GE spots reflecting changes in intrinsic charge due to PTMs in a study profiling the impact of sex steroids on the retina proteome (D’Anna et al., 2011). Most proteins found to be differentially expressed in experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) in the mouse retinal mitochondria were identified tentatively to undergo oxidation and carbamidomethylation based on MALDI-TOF analyses (Saraswathy and Rao, 2011). On the other hand, these modifications were probably introduced during sample analyses relying on the reported 2D-DIGE procedure. Identification of posttranslational phosphorylation was claimed for the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein from a 2D-GE spot by shotgun nanoflow LC–ESI-MS/MS analysis (Tsuji et al., 2007). However, this reported hit would not pass rigorous PTM validation by an expert analyst or criteria set by automated phosphopeptide–spectrum match algorithms (e.g., by ProPhosSI, Martin et al., 2010).

The redox proteome is a subset of proteins that are posttranslationally modified by reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive carbonyl species in a regulated way and through different mechanisms (Go and Jones, 2013). A common method to pursue redox proteomics (Dalle-Donne et al., 2005; Bachi et al., 2013), the “2D-oxyblot” approach involving 2D-GE combined with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) derivatization and DNPH-directed immunochemical detection has been applied to investigate oxidation of retinal proteins (Tezel et al., 2005). This technique detects protein carbonylation (Talent et al., 1998), a broad biomarker of protein oxidation and modifications by reactive carbonyl species generated by the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), carbohydrates and amino acids (Esterbauer, 1993; Berlett and Stadtman, 1997; Stadtman and Levine, 2003; Akagawa 2021). Immunoblotting of 2D-gels relying on antibodies against proteins covalently modified at histidine residues by 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde formed from n-6 PUFAs such as linoleic acid and arachidonic acid via several nonenzymatic steps) also was used to focus on PTM associated with this important reactive carbonyl species (Tanito et al., 2006). However, only a few proteins subject to oxidation and modified by 4-HNE were found through MALDI-TOF peptide mass fingerprinting and/or LC–ESI-MS/MS analyses of the excised 2D-GE spots showing differential DNPH-immunoreactivity in a comparative experimental design. In addition, these redox proteomics methods were unable to identify details of the detected protein carbonylation regarding chemistry and localization to amino acid residues in the protein sequence. These shortcomings were addressed by the introduction of newer, gel-free methodologies (Rauniyar et al., 2009; Madian and Regnier, 2010; Rauniyar and Prokai, 2011; Colzani et al., 2013; Fedorova et al., 2014; Vasil’ev et al., 2014); nevertheless, no reports have been published about their application to redox proteomics of the retina. After demonstrating a possible role of nitroxidative protein nitration in normal retinal physiology through an immunoblotting-based 2D-GE study (Miyagi et al., 2002), anti-nitrotyrosine immunoprecipitation from diabetic rat retina and RMG cells were used to enable their analyses by shotgun LC–ESI-MS/MS with focus on identifying nitroproteins (Zhan et al., 2008). However, all reported nitropeptides were misidentified, highlighting the importance of using efficient enrichment methods with rigorous validations for the purpose (Stevens et al., 2008; Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2011; Prokai et al., 2014).

Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining of 2D-gels was used to analyze phosphoprotein profiles of chick retina upon probing early recovery from lens-induced myopia (Zhou et al., 2018). Excised spots showing differential protein phosphorylations were identified by in-gel digestion followed by shotgun LC–ESI-MS/MS, which resulted in the putative identification of three phosphoproteins with no information about the site of PTM. In another study, phosphoprotein staining and in-gel/cross-gel 2D-image analysis were applied to pick spots indicating significant changes in phosphorylation in retinae of optic nerve crush-injured mouse eyes compared to the control. Tryptic peptides of 29 putative phosphoprotein spots of interest were analyzed after in-gel digestion both by MALDI-TOF and TOF/TOF MS/MS (Liu et al., 2020). However, larger-scale retina phosphoproteomics have relied on gel-free methodology including enrichment of phosphopeptides using TiO2 beads or microsphere-based immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) (Mazanek et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2013). For example, shotgun analyses of retinas from AIPL1−/− mice at the onset of rod cell death resulted in the detection of 2550 phosphoproteins after enrichment by TiO2 column (Du et al., 2018). TMT labeling of human retinal proteins followed by fractionation using basic-pH RPLC and TiO2-based phosphopeptide enrichment yielded the identification of 2568 unique phosphopeptides containing 3476 phosphosites (Selvan et al., 2018). TMT labeling of mouse retinae was also done after phosphopeptide enrichment using TiO2 beads, which was followed by two-dimensional nanoflow LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses relying on data-dependent acquisition to identify 1137 distinct phosphopeptides in wild type or protein kinase C α – knock-out mouse retina lysates (Wakeham et al., 2019). SILAC combined with Ti4+-IMAC-based enrichment revealed 1762 proteins and 2546 class I phosphorylation sites in cultured immortalized RPE-derived cell line (ARPE-19) using an LC–ESI-MS/MS-based shotgun approach (Chiang et al., 2017). Overall, the implementation of these gel-free methodologies has made phosphoproteomics an emerging area of research with great promise to reveal unique insights to retinal biology and pathology.

4 |. PROTEOMICS STUDIES FOCUSED ON BIOLOGY, PATHOLOGY AND THERAPY OF THE RETINA

The following sections highlight mass spectrometry-based proteomics applied to some broad areas of retina research. Brief discussions of the chosen studies focus on the photobiology, retinal neurodegenerations including ocular neurotherapy therapy developments, and review selected miscellaneous applications of the technique to retina physiology and pathology.

4.1 |. Photobiology

Broadly defined, photobiology of the retina entails scientific studies on biological phenomena involving non-ionizing radiation (more specifically visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light) in the organ. The retinal architecture displayed schematically in Figure 1B is highly conserved in vertebrates, and its major neuronal cells are RGCs, photoreceptors (rod and cones), bipolar cells, amacrine cells, horizontal cells with RMG cells and the RPE providing metabolic and homeostatic support (Sung and Chuang, 2010). As discussed in the Introduction, photoreceptors transmit synaptic information to bipolar cells, which is relayed to retinal ganglion cells and eventually the visual signal reaches the brain via their axons or optic nerve. Horizontal cells, amacrine cells, and RMG cells mediate and support the synapses between the retinal neurons. Unique to the RMG cellsis that their processes span the inner retina and most of the outer retina assisting the maintenance of multiple synapses throughout the tissue. Conversion of light energy to neural activity is initiated by the interaction of light with light-sensitive pigments (chromophores) located in the outer segments of rod and cone photoreceptors. Regeneration of chromophores occurs via another separate cycle known as the ‘visual cycle’ (Salesse, 2017). Moreover, the RPE enveloping photoreceptors are involved in the uptake of nutrients, key metabolites, and oxygen from the choroidal vessels (Janis et al., 2019). Intense visible light can induce rapid photoreceptor cell death in the retina. Although there have been promising applications of proteomics to photobiology, most relied on 2D-GE separations and leave room for future studies involving more powerful gel-free methods.

Association of various isoforms of crystallins with retinal degeneration in response to light injury and affected by circadian rhythm in rats was revealed by a 2D-GE-based proteomics study concluding that different apoptotic pathways were triggered in response to differential regulations of these crystallins during light damage (Organisciak et al., 2011). Focusing on the deleterious impact of different doses of ultraviolet A radiation, a similar experimental approach revealed 29 differentially regulated proteins in RPE cells included proteins associated with antiproliferation, induction of apoptosis, and protection against oxidative stress (Chen et al., 2019). Regulation of different caspases, as well as mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related proteins were also observed.

Using a 2D-GE-based nitroproteomics strategy, several nitrotyrosine-immunoreactive proteins were identified and many of them were quantified in the rat retina after exposure to intense green light compared with those maintained in the dark suggesting overall that protein nitration may be involved not only in light-induced photoreceptor cell death but also in normal retinal physiology (Miyagi et al., 2002). Exclusive protein targets for nitration after intense light exposure included heat shock protein 70, dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2, serum albumin, protein disulfide isomerase, glutamate dehydrogenase, and βA3/A1 crystallin. Identification of crystallins’ susceptibility to light-induced nitration also prompted a follow up proteomics study implicating these proteins in the protection of the retina’s rod outer segments against damage (Sakaguchi et al., 2003). After their localization in 2D-gels followed by PMF-based identification using MALDI-TOF MS, changes in nine crystallin isoforms in the rat retinae were investigated upon light exposure based on gel spot stain intensities to find that all were at least 2–3-fold greater abundance after light exposure compared to control retinae. Coomassie blue staining of αA-crystallin was particularly much more intense in light exposed than in control retinae indicating its significant modulation by the radiation.

A consistent dimerization of visual arrestin 1, which is a protein involved in phototransduction, in photoinjured retinal cells was observed through gel-based redox proteomics and linked to loss of photoreceptors in the process (Lieven et al., 2012). Another redox proteomics study using the same method revealed dimerization of recoverins (Ca+2-dependent inhibitors of rhodopsin kinases) using retinal extracts from bovine and rabbit samples and concluded that photochemical damage of photoreceptors occurred via oxidative stress leading to desensitization of rhodopsin by disulfide dimerization of recoverin and arrestins (Zernii et al., 2015).

4.2 |. Retinal Neurodegenerations and Their Therapies

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), retinitis pigmentosa (RP), AMD, and glaucoma are multifactorial neurodegenerative diseases and, though many insights have been gained about the origins, pathologies, and progressions of these maladies, full comprehension of their mechanistic details at molecular levels has remained elusive (Athanasiou et al., 2013). Mass spectrometry-based proteomics offers powerful support to address knowledge gaps regarding retinal neuropathies (Ahmed et al., 2018). Recent advances of the methods relying on retina tissue collected postmortem from humans and from animal models hold great promise to gain novel insights ocular neuropathology, advance disease biomarker discovery and support therapy developments to fight blindness caused by various forms of retinal neurodegenerations (Cehofski et al, 2017). This section briefly reviews progress of retina proteomics focusing on the common retinal neurodegenerative diseases. Key findings of selected publications are also summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings of LC-MS-based retina proteomics analyses of samples obtained from animal models of common ocular neurodegenerative diseases, as well as samples of human origin. References were arranged in reversed chronological order, and indicate a trend of gel-free techniques becoming the methods of choice in recent applications. Except those distinguished as DIA methods, the iTRAQ, TMT and label-free methods refer to the shotgun approach with DDA. Abbreviations: DR – diabetic retinopathy; RP – retinitis pigmentosa; AMD – age-related macular degeneration; E2 – 17β-estradiol.

| Reference | Species | Method | Key findings | Disease / Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carmy-Bennun et al. (2021) | Mus musculus | iTRAQ | Identified 42 regulated retinal proteins including crystallins and heat shock proteins in rd10 mice treated with an inhibitor of MYD88. | RP |

| Cehofski et al. (2021) | Mus musculus | iTRAQ | In a BRVO-based porcine model, 6-fold upregulation of the DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 17, and heat shock protein 70 cofactor in response to treatment with aflibercept. | AMD / Anti-VEGF intervention with aflibercept |

| Reinehr et al. (2021) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free, DIA (SWATH) | This study showed a complex, time-dependent regulations of protein expression in an S100B autoimmune model with TCA cycle and glutamate processing representing the main functional interactions related to the disease. | Glaucoma |

| Wert et al. (2020) | Mus musculus | Label-free | In a Pde6αD670 model of the disease, identified regulated proteins were mostly involved in oxidative metabolic pathways. | RP / TCA cycle metabolites |

| Grotegut et al. (2020) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free | Microglia in a S100B autoimmune model of glaucoma was shown to inhibit proteins involved in inflammatory response. | Glaucoma / minocycline |

| Mirzaei et al. (2020) | Rattus norvegicus | TMT | Decreased glutathione metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, cytoskeleton and actin filament organization, as well as increased expression of proteins involved in coagulation cascade, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and RNA processing were recognized in ocular hypertension. | Glaucoma |

| Chen et al. (2019) | Homo sapiens | 2D-GE | Revealed 29 differentially regulated proteins in RPE cells in response to UVA radiation. | UVA radiation-induced damage |

| Saddala et al. (2018) | Mus musculus | Label-free | Placental growth factor (P1GF) ablation in the mouse retina showed down-regulation of proteins essential for insulin resistance, together with the up-regulation of antioxidant and neuroprotective proteins. | DR / anti-P1GF therapies |

| Sundstrom et al. (2018) | Homo sapiens | 2D-GE | Post-mortem diabetic retinas revealed regulation of ATP synthases, NADH oxidoreductases, cytochrome oxidases, crystallins, apolipoproteins, and bioinformatics revealed mitochondrial dysfunction, protein ubiquitination pathway, Huntington’s disease signaling as top pathways in the disease. | DR |

| Mirzaei et al. (2017) | Homo sapiens | TMT | Proteins associated with mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and activation of the classical complement pathway-associated proteins were suggested to trigger an innate inflammatory response. | Glaucoma |

| Anders et al. (2017) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free | Protein network assembled from the findings assisted this early-phase therapy development by revealing distinct regulatory changes of retinal proteins in response to the proposed remedial intervention against the disease. | Glaucoma / α-crystallin B |

| Funke at al. (2016) | Homo sapiens | Label-free | Study revealed over 600 proteins involved in molecular transport, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis in glaucoma progression. | Glaucoma |

| Ly et al. (2016) | Mus musculus | Label-free | Over fifty proteins were differentially expressed in the retina during peak-degeneration rd10 versus wild-type mice. | RP |

| Cehofski et al. (2016) | Sus scrofa | iTRAQ | In retinas treated with VEGF inhibitor, integrin β-1, peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, OCIA domain-containing protein 1, calnexin and 40S ribosomal protein S5 showed significant downregulation. | AMD / ranibizumab |

| Yang et al. (2015) | Homo sapiens | 2D-LC–MS/MS using DDA and differential 16O/18O-labeling | Various heat shock proteins, ubiquitin proteasome pathway components, antioxidants, and DNA repair enzymes were found to be upregulated, while many proteins involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation were downregulated in the glaucomatous retina. | Glaucoma |

| Zernii et al. (2015) | Bos taurus, Oryctolagus cuniculus | Gel-based redox proteomics | Dimerization of recoverin proteins lead to damage of photoreceptor cells. | Light-induced damage |

| Ly et al. (2014) | Mus musculus | Label-free | Identified 98 diabetes-regulated retina protein and the impact of metformin treatment. Treatment regulated 63 retinal proteins but only 43 proteins were found to be diabetes-regulated. | DR / metformin |

| Prokai-Tatrai et al. (2013) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free | The study revealed regulation of various proteins including neuroprotective crystallins and histones in response to topical drug treatment. | Glaucoma / E2 |

| Zhang et al. (2013) | Mus musculus | iTRAQ | Along with the identification of 348 diabetes-regulated proteins, retinopathy-related changes in the expression of 60 proteins were found to be reversed by phlorizin therapy. | DR / phlorizin |

| Schallenberg et al. (2012) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE | Identified 4 major retinal protein biomarkers: high-mobility-group-protein B1, heat shock protein 70, calmodulin and carbonic anhydrase II. | Glaucoma / dorzolomide and travopost |

| Hollander et al. (2012) | Rattus norvegicus | iTRAQ | The study revealed the neuroprotective role of hepatoma-derived growth factor on injured RGCs upon optic nerve transection in the rat eye. | Glaucoma |

| Lieven et al. (2012) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE-based redox proteomics | Consistent dimerization of visual arrestin 1, a protein involved in phototransduction, in photo-injured retinal cells was observed and linked to loss of photoreceptors. | Light-induced damage |

| Stowell et al. (2011) | Macaca mulatta | Label-free, DIA (MSE) | Identified over hundred proteins per sample in retina permitting comparisons of protein expression changes after chronic IOP elevations and surgical transection of the orbital optic nerve. | Glaucoma |

| VanGuilder et al (2011) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free | Alterations in pro-inflammatory, signaling and crystallin family proteins were recognized in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model. The study also identified preclinical biomarkers that were not replenished by insulin treatment. | DR / Insulin |

| Organisciak et al. (2011) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE | Identification of various isoforms of crystallins triggering apoptosis involved with retinal degeneration in response to light injury and circadian rhythm. | Light-induced damage |

| Yuan et al. (2010) | Homo sapiens | iTRAQ | Identified a total of 901 proteins, with 56 elevated and 43 reduced in the macular Bruch membrane/choroid complex of human macular tissues from early/mid-stage dry/wet AMD eyes. | AMD |

| Finnegan et al. (2010) | Gallus gallus | 2D-GE | The study revealed 7 proteins involved in RP that are involved in nucleoside biosynthesis, regulation of transcription, and protein synthesis-related signaling cascades. | RP |

| Fort et al. (2009) | Rattus norvegicus | Label-free | In a streptozotocin-induced diabetic model, various isoforms of crystallins were upregulated resulting in inflammatory insults. | DR |

| Kanamoto et al. (2009) | Mus musculus | 2D-GE | Eighteen differentially expressed proteins were identified in a mouse model of glaucoma. These proteins included cell membrane receptors and proteins associated with intracellular signaling pathways. | Glaucoma |

| Alcazar et al. (2009); Ng et al. (2008); Warburton et al (2005) | Homo sapiens | Label-free | Identified of lipofuscin and melanolipofuscin in diseased human RPE. | AMD |

| Miyara et al. (2008) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-DIGE | Downregulation of CRYAA, superoxide dismutase 1, and triosephosphate isomerase 1 was observed after IOP increase. | Glaucoma |

| Norgaard et al. (2008) | Homo sapiens | Mitochondrial enrichment before 2D-GE | Emphasizing the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in AMD, mitochondrial heat shock proteins, ATP synthases, mitochondrial translation factors, etc., were found to be regulated by the disease. | AMD |

| Norgaard et al. (2006) | Home sapiens | 2D-GE | Identified and compared proteins altered in the RPE at the early and late stages of AMD showing decreased expressions of several heat shock proteins and components of apoptotic signaling pathways in early AMD. Late-stage AMD revealed regulation of retinoic acid and rhodopsins. | AMD |

| Ethen et al. (2006) | Homo sapiens | MALDI-TOF | The key identified proteins were involved functional pathways of microtubule regulation in addition to protection from stress-induced protein unfolding. | AMD |

| Tezel et al. (2005) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE | Proteins showing increased carbonylation due to elevated IOP included glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, heat shock protein 72, and glutamine synthetase. | Glaucoma |

| Umeda et al. (2005) | Macaca fascicularis | Label-free | Sixty proteins were cataloged in the maculae of cynomolgus monkeys with late-onset macular degeneration including annexins, crystallins, immunoglobulins, and complement components. | AMD |

| Sakaguchi et al. (2003) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE-based nitroproteomics, MALDI-TOF MS | Based on gel spot stain intensities, nitration of 9 crystallins were found to induced by light exposure. | Light-induced damage |

| Miyagi et al. (2002) | Rattus norvegicus | 2D-GE and LC-MS/MS based nitroproteomics | Nitrotyrosine-immunoreactive proteins were identified in rat retina after exposure to intense green light. | Light-induced damage |

| Crabb et al. (2002) | Homo sapiens | Label-free | The study identified over hundred human drusen proteins including tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 3, clusterin, vitronectin and crystallins. | AMD |

4.2.1 |. Diabetic Retinopathy

DR is one of the most common complications associated with diabetes (Antonetti et al., 2021). Predominant forms of the disease are categorized as mild, moderate, and severe non-proliferative and proliferative diabetic retinopathies (Wong et al., 2016).

Several retina proteomics investigations have been reported using experimental animal models of diabetic retinopathy. One of the most extensively used animal models relies on streptozotocin-induced diabetes, and a striking feature of independent proteomics studies using this model has been a common upregulation pattern of various isoforms of crystallins in the retina under diabetic conditions (VanGuilder et al, 2011; Fort et al, 2009). These studies postulated among others the neuroprotective role of crystallins in the retina against inflammatory insults. Additionally, a few proteins not fully normalized by chronic insulin treatment have been proposed as potentially useful preclinical biomarkers to test novel therapeutics intended to be used in conjunction with insulin therapy to treat diabetic retinal dysregulations that are not normalized by insulin replenishment (VanGuilder et al., 2011). Another study delineated the altered retinal proteome profile in control versus streptozocin-induced diabetic mice showing differential regulation of 65 proteins (Gao et al., 2009).

Using an iTRAQ-based shotgun proteomics approach, 348 diabetes-regulated proteins were discovered in the mice retina, and retinopathy-related changes in the expression of 60 proteins were found to be reversed by phlorizin therapy (Zhang et al., 2013). The study revealed several molecular events such as apoptosis, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism to be modulated by phlorizin treatment under diabetic conditions in the retina. A label-free shotgun retina proteomics study also addressed the effect of metformin on the retinal proteomes in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes (Ly et al., 2014). While pathway enrichment analysis indicated decreases in levels of proteins related to synaptic transmission and cell signaling based on 98 differentially expressed proteins comparing db/db and wild-type animals, metformin regulated 63 retinal proteins but only 43 proteins were found be also diabetes-regulated. The latter observation suggested that metformin only partially ameliorated retinopathy. More recently, a label-free shotgun retina proteomics study relying on placental growth factor (P1GF) ablation in the retinae of C57BL6, Akita, PlGF−/− and Akita.PlGF−/− mice uncovered that down-regulation of proteins essential for insulin resistance, together with the up-regulation of antioxidant and neuroprotective proteins, could be potential mechanisms important for future anti-PlGF therapies in the treatment of diabetic retinopathy (Saddala et al., 2018).

A pioneering retina proteomics study focusing on the retina investigated postmortem retinae from nondiabetic and diabetic patients manifesting early diabetic retinopathy by the geLC–MS/MS method (Sundstrom et al. 2018). Disease-regulated proteins included ATP synthases, NADH oxidoreductases, cytochrome oxidases, crystallins, apolipoproteins, and bioinformatics revealed mitochondrial dysfunction, protein ubiquitination pathway, Huntington’s disease signaling as top pathways associated with the diseased retina.

4.2.2 |. Retinitis pigmentosa

RP is one of the most common retinopathies caused by genetic mutations (Hartong et al., 2006). In an early study relying on 2D-GE-based proteomics and a chick model involving retinal dysplasia and degeneration, seven proteins were highly regulated in diseased retinae, which included valosin-containing proteins, synucleins, and stathmin (Finnegan et al., 2010). The findings provided comparative data on both retinogenesis and onset of degeneration. Bioinformatics analysis revealed the involvement of these proteins in nucleoside biosynthesis, regulation of transcription, and protein synthesis-related signaling cascades in retinitis pigmentosa.

Based on a label-free shotgun proteomics study facilitated by FASP (Wiśniewski et al., 2009), over fifty proteins were found to be differentially expressed in the retina during peak-degeneration compared to those in wild-type mice using the rd10 mouse model of the disease (Ly et al., 2016). Network analysis separated these proteins into one cluster of down-regulated photoreceptor proteins and one of up-regulated signaling proteins centered around glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and two signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STAT3, and STAT1). A recent iTRAQ labeling-based shotgun proteomics study found 42 retinal proteins of rd10 mice to respond treatment with an inhibitor of MYD88, adapter protein that links toll-like receptors and interleukin-1 receptors with downstream signaling molecules (Carmy-Bennun et al., 2021). Notable affected proteins included various isoforms of neuroprotective crystallins and heat shock proteins involved in various multicellular organismal process (e.g., eye development) demonstrating the therapeutic potential of retina-protective pathways against photoreceptor-degenerating diseases through the inhibiting MyD88.

Comparative label-free shotgun proteomics of retina and vitreous samples from autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa patients with PDE6A mutations and Pde6αD670 mice carrying these mutations identified molecular pathways affected at the onset of photoreceptor death were carried our recently (Werth et al., 2020). The highest represented GO categories in the retinae of the mutant mice were cellular process, catalytic activity, and intracellular functions. In addition, oxidative metabolic pathways were found to be downregulated in the Pde6αD670 mouse retina at the onset of neuronal cell death. This led to the development of an experimental medication strategy involving treatment with metabolites specifically involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle offering neuroprotection against photoreceptor cell death in retinitis pigmentosa models.

4.2.3 |. AMD and related retinopathies

The macula is part of the retina and responsible for central vision, most of the color and fine-detail vision because it has a very high concentration of photoreceptor cells (Bedinghaus, 2020). AMD is associated mainly with degeneration of the macula or retina of patients over 65 years of age. It is one of the leading causes of blindness in developed countries, and manifests in wet and dry forms (Lim et al., 2012). An extracellular lipoprotein deposit under the retinal epithelium commonly termed as drusen is one of the major pathological changes, which eventually leads to damage of the RPE cells and photoreceptors. Proteomics of RPE cells have been reviewed recently (Beranova-Giorgianni and Giorgianni, 2018), and interested readers should refer to this publication for detailed summaries and discussions on the subject. Therefore, the section below is devoted to cover only selected milestones of retina proteomics studies about AMD and related retinopathies.

Several proteomics studies have been directed to the retina obtained from human donor eyes with AMD and from animal models mimicking its ocular pathology. 2D-GE analyses followed by protein identification through PMF using MALDI-TOF MS and sequence tags obtained by LC–MS/MS were used to identify proteins exhibiting significant changes in expression with disease onset and progression in a series of studies relying on retinal tissues of human donors. First, proteins altered in the RPE at the early and late stages of AMD were shown and compared (Norgaard et al., 2006). This study provided direct evidence for decreased expressions of several heat shock proteins and components of apoptotic signaling pathways in early AMD, indicating the role of stress-induced protein unfolding and aggregation, mitochondrial trafficking and refolding, as well as regulating apoptosis as a potential causal mechanism of the disease. Late-stage changes indicating likely secondary consequences of AMD involved proteins that regulate retinoic acid and regeneration of the rhodopsin chromophore. Protein expression changes at disease onset or with progression and at end-stage disease in the maculae and neurosensory retinae of human donors were compared in a subsequent study (Ethen et al., 2006). The identified proteins are involved in key functional pathways including microtubule regulation in addition to protection from stress-induced protein unfolding identified in the earlier study (Norgaard et al., 2006). These results also implied that both the macula and periphery of the retina were affected by AMD. Focusing on the likely role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of the disease, a third study relied on mitochondrial enrichment before 2D-GE-based proteomic analyses of RPEs (Norgaard et al., 2008). Decreased expressions of the mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and three ATP synthase subunits, as well as increased content of a mitochondrial translation factor were found to be associated with AMD, supported the hypothesis that mitochondrial DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction contributed to the pathogenesis of the disease. Notwithstanding the noted limitations of a 2D-GE-based proteomics study including limited proteome coverage due to underrepresented membrane proteins, acidic and basic proteins outside the range of the isoelectric focusing dimension and inability to detect changes in the expression of low-abundance proteins (Norgaard et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the results of these retina proteomics studies revealed important traits about the molecular basis of AMD.

A LC–MS/MS-based shotgun proteomics have cataloged over one hundred human drusen proteins initially (Crabb et al., 2002). Tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP3), clusterin, vitronectin and serum albumin were the most common in the samples. Although rigorous MS-based protein quantitation was not done, crystallins were detected more frequently in the AMD donors’ drusens. Sixty proteins were cataloged in the maculae of cynomolgus monkeys with late-onset macular degeneration (Umeda et al., 2005), and many of them such as annexins, crystallins, immunoglobulins, and complement components also were common constituents of the drusen in human AMD (Crabb et al., 2002). Cataloging of lipofuscin, melanolipofuscin and blebs, which may also contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease, isolated from human RPEs have also been done by shotgun proteomics (Warburton et al., 2005; Ng et al., 2008; Alcazar et al., 2009). Of the total 901 quantified proteins, 56 were found to be elevated and 43 were found to be reduced in the human macular Bruch’s membrane/choroid complex from early/mid-stage dry AMD, six advanced dry AMD, and eight wet AMD donor eyes when compared to controls by an iTRAQ-based proteomics study (Yuan et al., 2010). By category of disease progression, up to 16 proteins elevated or decreased in each category. The elevated proteins were linked to immune response and host defense and included many complement proteins and damage-associated proteins such as α-defensins 1–3, S100s proteins, crystallins, histones, and galectin-3. A few retinoid processing proteins were elevated only in early/mid-stage AMD, which supported retinoids’ role in the initiation of the pathology. Proteins uniquely decreased in early/mid-stage of AMD implicated hematologic malfunctions and weakened extracellular matrix integrity and cellular interactions. Overall, these findings highlighted inflammatory process in the progression of this disease in the retina. Recent interest in the field has moved to proteomics-based biomarker discovery relying on eye and body fluids (e.g., Koss et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Nobl et al., 2016; Qu et al., 2019; Sivagurunathan et al., 2021), which was outside the scope of this review focusing primarily on retina proteomics.

The wide use of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors to treat neovascular AMD (and other related vision-threatening maladies including branch retinal vein occlusion with macular edema, central retinal vein occlusion with macular edema, diabetic macular edema, and also diabetic retinopathy) brought about an interest in gaining insights into the protein expression changes that occur following anti-VEGF intervention (reviewed by Cehofski et al., 2017). Shotgun proteomics methods were used to evaluate proteome changes following experimental branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and intervention with ranibizumab in a porcine model. In retinas treated with the VEGF inhibitor, five proteins (integrin β-1, peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, OCIA domain-containing protein 1, calnexin and 40S ribosomal protein S5) showed statistically significant decrease in content by both label-free and iTRAQ-based quantitation (Cehofski et al., 2016). In another retina proteomics study focusing on treatment with aflibercept to gain insights into its mechanisms of action and safety profile using the BRVO-based porcine model, label-free shotgun proteomics identified 6-fold upregulation of the DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 17, heat shock protein 70 cofactor with a hitherto unknown function (Cehofski et al., 2021).

4.2.4 |. Glaucoma

Glaucoma is an ocular neuropathy associated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) marked by the degeneration of the optic nerve that results in loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) leading to visual impairment (Weinreb et al., 2014). Elevated intraocular pressure and age are the two most critical factors in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. Nevertheless, some patients with normotensive eye have also exhibit glaucomatous symptoms, and recent studies pointed to the involvement of the immune system in the disease.

2D-GE-based proteomics was first applied to glaucoma to identify oxidatively-modified retinal proteins in a chronic pressure-induced rat model (Tezel et al., 2005). Increased carbonyl immunoreactivity in ocular hypertensive eyes were confirmed by immunolabeling. Proteins showing increased carbonylation due to elevated IOP and identified from gel spots included glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, heat shock protein 72, and glutamine synthetase. Based on 2D-DIGE analysis to study global protein expression in the retinas of normotensive and glucocorticoid-induced ocular hypertensive rats, downregulation of CRYAA, superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, and triosephosphate isomerase 1 was observed shortly after IOP increase (Miyara et al., 2008). These early proteomics studies have already highlighted the impact of ocular hypertension on glycolysis, stress response and excitotoxicity as biological processes driving the disease at proteome and redox proteome levels. In another retina proteomics study that utilized 2D-GE to examine protein expression changes in the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma, 18 differentially expressed proteins were identified (Kanamoto et al., 2009). These proteins included cell membrane receptors and proteins associated with intracellular signaling pathways, and the downregulation of integrin β7 was correlated in a follow-up experiment with RGCs death due to excitotoxicity in the glaucomatous process. Four major retinal proteins associated with ocular hypertension were identified by LC–MS/MS using an inherited glaucoma rat model in a 2D-GE-based study: high-mobility-group-protein B1 (HMGB1, a non-histone nuclear protein with dual function); heat shock protein 70 (HSP70, a molecular chaperone and stress protein); calmodulin (a Ca2+-binding protein); and carbonic anhydrase II (a zinc metalloenzyme that catalyzes the reversible hydration of CO2 to form carbonic acid) (Schallenberg et al., 2012). This study was highly translational in scope, because follow-up experiments also tested the impact of antiglaucoma eye drops on protein biomarkers of the disease in the model concluding that dorzolamide and travoprost had affected the retina proteome differently and regardless of their IOP-lowering effects. Therefore, the findings were expected to facilitate development of treatments that would exert neuroprotection against glaucomatous neurodegeneration through direct pharmacological activity.

The introduction of gel-free methods has been a game changer in retina proteomics studies focused on glaucoma. Label-free shotgun proteomics using MSE-based DIA covered over hundred proteins per sample in the non-human primate retina permitting comparisons of protein expression changes after chronic IOP elevations and surgical transection of the orbital optic nerve (Stowell et al., 2011). In addition, there was on average a 300-fold difference between the least and the most abundant protein among the quantified proteins in each retina indicating the dynamic range of the method. The results suggested condition-specific changes of the retina proteome with cytoarchitecture regulation as a component of the early retinal response to chronic experimental IOP elevation. An iTRAQ-based quantitative retina proteomics study also revealed the neuroprotective role of hepatoma-derived growth factor on injured RGCs upon optic nerve transection in the rat eye (Hollander et al., 2012).

When retina samples obtained from human donors with ocular hypertension (without glaucomatous injury) and age-and sex-matched normotensive controls were analyzed by shotgun 2D-LC-MS/MS using differential 16O/18O-labeling labeling for relative protein quantification, hundreds of proteins exhibited over 2-fold change in expression upon comparing ocular hypertensive samples to normotensive controls (Yang et al., 2015). Various pathways important for maintenance of cellular homeostasis in the ocular hypertensive retina were revealed by bioinformatics. Various heat shock proteins, ubiquitin proteasome pathway components, antioxidants, and DNA repair enzymes were found to be upregulated, while many proteins involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation were downregulated in the ocular hypertensive retina without detectable neuroinflammation or ongoing cell death process. Label-free quantitative shotgun proteomics study to identify glaucomatous alterations in the human retina covered over 600 proteins and revealed the involvement of molecular transport, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis in the disease (Funke at al., 2016). The results showed, e.g., retinal downregulation of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase, mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocases, E1-subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex were also found to be severely downregulated in glaucomatous models. These proteins are associated with mitochondrial energy supply confirming the development of a bioenergetics crisis during the progression of glaucoma in retina (Eells, 2019; Casson et al., 2021). The crystallin family of heat shock proteins have been emerging therapeutic targets at least in part due to retina proteomics studies (e.g., Prokai-Tatrai et al., 2013). A preclinical evaluation of intravitreal injection of α-crystallin B to protection the retina against glaucomatous neurodegeneration has been assisted recently by label-free retina proteomics using IOP elevation induced by episcleral vein cauterization that resulted in a considerable impairment of the RGCs and the retinal nerve fiber layer in rats as a glaucoma model (Anders et al., 2017). Protein network assembled from the findings assisted this early-phase therapy development by revealing distinct regulatory changes of retinal proteins in response to the proposed remedial intervention against the disease.

Through a TMT label-based shotgun proteomics study designed to evaluate the association between glaucoma and other neurodegenerative disorders by investigating glaucoma-associated protein changes in the retina and vitreous humor, defects in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation machinery and activation of the classical complement pathway-associated proteins suggesting an innate inflammatory response were revealed from glaucomatous human tissues (Mirzaei et al., 2017). Using a rat model in which IOP was increased by weekly microbead injections into the eye, decreased glutathione metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction affecting oxidative phosphorylation, cytoskeleton, and actin filament organization, as well as increased expression of proteins in the coagulation cascade, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and RNA processing were the top processes associated with the chronic IOP increase (Mirzaei et al., 2020). Modulation of nuclear receptor signaling, cellular survival, protein synthesis, transport, and cellular assembly were the associated major pathways driving these processes. Overall, alterations in crystallin family, glutathione metabolism, and mitochondrial dysfunction associated proteins shared similarities between human glaucoma and the rat model of the disease. However, the activation of the classical complement pathway and upregulation of cholesterol transport proteins were exclusive for the glaucomatous human retinae. In the most recent proteomics study focused on glaucoma using retinal tissue (Reinehr et al., 2021), DIA-based LC–MS/MS measurements showed a complex, time-dependent regulations of protein expression in an S100B autoimmune model in rats with the TCA cycle and glutamate processing representing the main functional interactions related to the disease one and two weeks after immunization, respectively. The role of microglia in this model of glaucoma-like degeneration of retina also was addressed earlier through a label-free shotgun proteomics study and using minocycline to inhibit inflammatory response (Grotegut et al., 2020). Canonical pathway analyses of the many differentially expressed proteins showed that minocycline treatment decreased the apoptotic, inflammatory, and metabolic processes induced by S100B injections into the eye.

4.3 |. Miscellaneous