Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes has been used as an experimental live vector for the induction of CD8-mediated immune responses in various viral and tumoral experimental models. Susceptibility of BALB/c mice to Leishmania major infection has been correlated to the preferential development of Th2 CD4 T cells through an early production of interleukin 4 (IL-4) by a restricted population of CD4 T cells which react to a single parasite antigen, LACK (stands for Leishmania homologue of receptors for activated C kinase). Experimental vaccination with LACK can redirect the differentiation of CD4+ T cells towards the Th1 pathway if LACK is coadministrated with IL-12. As IL-12 is known to be induced by L. monocytogenes, we have tested the ability of a recombinant attenuated actA mutant L. monocytogenes strain expressing LACK to induce the development of LACK-specific Th1 cells in both B10.D2 and BALB/c mice, which are resistant and susceptible to L. major, respectively. After a single injection of LACK-expressing L. monocytogenes, IL-12/p40 transcripts showed a rapid burst, and peaks of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-secreting LACK-specific Th1 cells were detected around day 5 in the spleens and livers of mice of both strains. These primed IFN-γ-secreting LACK-reactive T cells were not detected ex vivo after day 7 of immunization but could be recruited and detected 15 days later in the draining lymph node after an L. major footpad challenge. Although immunization of BALB/c mice with LACK-expressing L. monocytogenes did not change the course of the infection with L. major, immunized B10.D2 mice exhibited significantly smaller lesions than nonimmunized controls. Thus, our results demonstrate that, in addition of its recognized use for the induction of effector CD8 T cells, L. monocytogenes can also be used as a live recombinant vector to favor the development of potentially protective IFN-γ-secreting Th1 CD4 T lymphocytes.

Listeria monocytogenes infection induces both major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted CD8- and MHC class II-restricted CD4 T-cell responses (30, 33). Upon phagocytosis, the majority of internalized L. monocytogenes cells are digested in the phagolysosomal compartment of the macrophages while the remaining bacteria reach the cytosol via the action of the product of the hemolysin (hly) gene. L. monocytogenes-derived antigens are thus able to enter both endogenous MHC class I and exogenous MHC class II antigen processing and presentation pathways. L. monocytogenes has been used as an experimental live vector in various viral (e.g., lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV], influenza virus, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) and tumoral experimental models (16, 22, 44). The common factor of these models relies on the importance of the CD8-mediated immune response. Deliverance in vivo of a heterologous antigen for further processing along the MHC class II pathway and eventual induction of specific CD4 T lymphocytes has not yet been tested in detail in the L. monocytogenes model of vector immunization. These abilities of L. monocytogenes were evaluated only recently in an HIV peptide presentation model in vitro (19) and in vivo (28). In addition, it is only in the last few years that some targets of the Listeria-specific CD4 T cells have been defined, namely, p60 (10), listeriolysin O (38), the 3A1.1 protein (39), and the 12A4.G7 protein (4). However, a precise characterization of the dynamics of the CD4 immune response directed against a specific antigen during Listeria infection has not yet been conducted.

Numerous reports have shown that L. monocytogenes efficiently induces interleukin-12 (IL-12) secretion by macrophages, either in the noninfectious form of heat-killed bacteria (21) or as live infectious organisms (27, 40, 46). Viable L. monocytogenes induces expression of IL-12/p40 mRNA (40) and protein (27, 46) in mouse spleen macrophages in vitro as well as in vivo; the CD4 T cells induced during experimental infection secrete type 1 cytokines (20), in particular, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and they mediate delayed-type hypersensitivity in all mouse strains studied (30, 33, 43). On the other hand, early neutralization of IL-12 decreases resistance to Listeria infection (42).

Experimental infection with the protozoan parasite Leishmania major results, depending on the inbred mouse strain, either in localized self-healing lesions in L. major-resistant mice or in nonhealing lesions in L. major-susceptible mice. Resistance and susceptibility have been shown to rely on the preferential expansion of Leishmania-reactive Th1 and Th2 CD4 T lymphocytes, respectively (37). Following various experimental manipulations of the immune system prior to or at the time of L. major inoculation, susceptible BALB/c mice are able to mount a Th1 immune response that results in healing. In particular, efficient immunization of susceptible BALB/c mice with soluble leishmanial antigens or purified leishmanial proteins has been obtained through coadministration of IL-12 as an adjuvant (1, 32). Among the few leishmanial molecules studied as vaccine candidates, LACK (stands for Leishmania homologue of receptors for activated C kinase) is a 36-kDa protein highly conserved among various Leishmania species and expressed at both the promastigote and amastigote stages (32) and whose functions are now under study (11). The early CD4 T-cell response in susceptible BALB/c mice is oligoclonal and reflects the expansion of a population of Vβ4/Vα8 CD4 T cells specific for an I-Ad-bound LACK epitope (amino acids 158 to 173). Activation of these cells results in rapid production of IL-4, which drives the subsequent anti-L. major Th2 response, resulting in the characteristic nonhealing disease (23, 26). In vivo depletion of the Vβ4 CD4 T cells (26) or tolerance to LACK in LACK-transgenic mice (23) leads to a healing phenotype in BALB/c mice. Experimental vaccination of mice with LACK has been found to be efficient only when the protein is coadministered with IL-12 (23), when it is administered as LACK DNA (18), or when it is coadministered with IL-12 DNA (17) for time-sustained immunity. Stimulation of the endogenous production of IL-12 at the time of immunization thus seems to be a promising way of optimizing the efficiency of a protective anti-Leishmania vaccine.

In this paper, we analyzed the anti-LACK CD4 immune response generated by a recombinant attenuated Listeria strain expressing the L. major LACK protein. This approach had two aims: (i) to use this foreign antigen as a comarker of the naturally processed listerial proteins and thus to monitor the specific CD4 immune response and (ii) to test the ability of L. monocytogenes, which may be considered to act both as an immunizing vector and as an adjuvant, to express in vivo this heterologous antigen and to induce a Th1-oriented immune response in vivo. We first studied in the main target organs of Listeria, i.e., the spleen and the liver, the dynamics of the CD4 LACK-specific immune response induced by L. monocytogenes after intravenous (i.v.) inoculation and characterized its ability, as a recombinant live vector, to induce a Th1-oriented CD4 immune response in both L. major-resistant B10.D2 and -susceptible BALB/c H-2d mice. The functionality of these L. monocytogenes-induced CD4 T cells was then characterized by their ability to be recruited in the regional lymph node during the first days of a subcutaneous L. major infection and by their effect on the development of the Leishmania lesions in resistant and susceptible mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and bacterial and parasitic strains.

Female BALB/c and B10.D2/ NOIaHsd mice, aged 8 to 12 weeks, were obtained from our specific-pathogen-free unit at the Institut Pasteur or from Harlan (Bicester, United Kingdom). Bacteria used were the L. monocytogenes-derived Tn917-lac actA mutant LUT12 (25), a recombinant LUT12 strain expressing the nucleoprotein of the LCMV (NP) (15), and Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, Md.). The L. major strain used was the National Institutes of Health strain 173 (MHOM/IR/−/173).

Construction of the recombinant LACK-L. monocytogenes.

All cloning and analytical procedures were carried out according to standard protocols (2). Plasmids used were CO364, which carries the lack gene of the L. major strain MHOM/IR/−/173 (33), and pPG5, which carries the fragment coding for the signal sequence and the promoter and regulatory sequences of the hemolysin gene (hly) of L. monocytogenes (15). The entire lack gene without any exogenous additional sequence was excised from the CO364 plasmid with EcoRI and HindIII, and both ends were filled in with Klenow's polymerase. It was then inserted in frame with the fragment coding for the signal sequence of the hly gene at the SmaI site from the pPG5 plasmid linker, yielding the pNS3 plasmid. The sequence of the genetic construct was verified at both junctions, 3′ and 5′. The pNS3 plasmid was introduced by electroporation in mutanolysin-treated (45) LUT12, yielding EMA2. Briefly, late-log-phase LUT12 cells were washed in 20 mM Tris—1 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.5), resuspended in 1/40 (vol/vol) of the same buffer supplemented with 0.5 M sucrose (TMS) and containing 50 U of mutanolysin (Sigma), and incubated for 2 min at 37°C. After one wash in TMS, the bacteria with their walls partially digested were subjected to electroporation at 200 Ω, 25 μF, and 2.5 kV; immediately transferred to prewarmed (37°C) 0.5 M sucrose–brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.); and incubated for 2 to 3 h at 37°C before isolation of the recombinant clones in the presence of 20 μg of chloramphenicol per ml.

Detection of LACK protein expression in the recombinant L. monocytogenes.

The presence of the LACK protein was detected through activation of the LACK-specific hybridoma T cells 0D12 (5 × 104 cells per well) (36) using as antigen-presenting cells (APC) syngeneic bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) prepared as previously described (35). The APC were either incubated with proteins of the Listeria supernatants or infected with the live recombinant Listeria. Culture was performed in a final volume of 200 μl of RPMI 1640–N-acetyl-l-alanyl-l-glutamine (Seromed, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml.

Preparation of the bacterial supernatant proteins was carried out on 10 ml of an overnight culture of either LACK-L. monocytogenes or the control NP-L. monocytogenes. The proteins were precipitated in 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at 4°C and spun at 18,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 90% acetone kept previously at −20°C and incubated overnight at −20°C in order to dissolve the coprecipitated pigments and eliminate the remaining TCA. After centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the pellets were resuspended in cell culture medium and added to the test wells.

For infection of BMDM, the recombinant listeriae were added at multiplicities of infection ranging from 5 to 320 to the test wells in culture medium without antibiotics. After 30 min, when listeriae were already inside the cells, the wells were washed and antibiotics (gentamicin at 50 μg/ml plus ampicillin at 100 μg/ml) were added to prevent lysis of the infected BMDM during the remainder of the experiment. Since the recombinant L. monocytogenes used was the LUT12 actA mutant, no cell-to-cell spread could occur and the listeriae remained inside the cells first encountered. After 24 h, the cell culture supernatant was harvested and analyzed for the presence of IL-2 with a functional assay using CTLL-2 cells as responders. The CTLL-2 cells were incubated with the cell culture supernatants for 16 h and then pulsed with [methyl-3H]thymidine, 0.5 μCi/well, for a further 8 h. DNA-incorporated radioactivity was measured on a TriLUX counter (EG & G Wallac, Evry, France).

Immunization with LACK-L. monocytogenes.

Bacterial stocks were kept at −80°C in bacterial culture medium containing 15% glycerol. Aliquots were thawed before the experiments, washed in 0.15 M NaCl, and diluted to the desired concentration in sterile apyrogen–0.15 M NaCl. i.v. injections (5 × 107 bacteria) were done in a volume of 0.2 ml using a 25-gauge needle at a time interval of more than 2 weeks. The size of the inoculum was retrospectively checked by enumeration on Bacto Tryptose agar.

Preparation of mouse cell suspensions and ex vivo reactivation.

Single-cell suspensions from at least three mice were prepared from spleen, liver, and popliteal lymph nodes. The isolation of the liver lymphoid cells was performed as previously described (13). Lymphoid cell reactivation was performed by incubating in triplicate wells 2 × 105 to 4 × 105 lymphoid cells per well in a final volume of 200 μl with either medium alone, the LACK peptide containing amino acids 158 to 173 (LACK158–173) (from 7.5 to 30 μM) (23), the entire recombinant LACK protein (2.5 to 10 μg/ml), heat-killed L. monocytogenes (HKLM; equivalent to 108 bacteria per ml), or, as a negative control, an unrelated antigen, hen egg ovalbumin (OVA; 5 μg/ml). For liver-derived lymphoid cells, irradiated (1,000 rads) syngeneic spleen cells were used as an additional source of APC (5 × 104 cells per well). Cell culture supernatants were harvested at 24 h for IL-2 detection and at 48 h for IFN-γ and IL-4 detection and kept at −20°C before cytokine quantitation.

Immunoassays for IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) using a pair of monoclonal antibodies specific for IL-2 (JES6-1A12 and JES6-5H4; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), IL-4 (11B11 and BVD6-24G2; Pharmingen), and IFN-γ (ATCC HB170 and AN-18.17.24 [34]) were used to quantify the amounts of IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ present in cell culture supernatants according to classic protocols (5). A standard curve for each assay was generated with known concentrations of each cytokine. IL-4 and IL-2 standards were supernatants from transformed cell lines derived from X63Ag8-653 (24), kindly provided by F. Melchers (Basel Institute, Basel, Switzerland); murine recombinant IFN-γ was kindly provided by G. R. Adolf (Ernst Boehringer-Institut für Arzneimittelforshung, Vienna, Austria). Standardization and quantification were done with KC4 software (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vt.).

Depletion or enrichment of T-lymphocyte subpopulations.

Thy1 T cells were specifically depleted with the anti-Thy1.2 immunoglobulin M monoclonal antibody J1j (ATCC TIB 184) and complement as previously described (14). Depletion or enrichment of CD4 or CD8 T cells was performed by magnetic separation with anti-CD4- or -CD8-labeled magnetic microbeads on VS+ columns with a VarioMacs apparatus (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Depletion or enrichment efficiency was checked by cytofluorimetric analysis using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD4 and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD8 antibodies (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France) on a FACScan analyzer (Becton Dickinson).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription.

At designated time points after infection, whole spleens were excised and total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as previously described (6). Briefly, spleen cell suspensions (3 × 107 cells) were homogenized with 1 ml of lysis buffer by several forced passages through a syringe of 1 ml mounted with a 25-gauge needle, and then total RNA was extracted using the columns of the kit according to the manufacturer's protocol and quantified at 260 nm. RNA was reverse transcribed using 5 μg of total RNA in a final volume of 20 μl with 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reverse transcription mixture consisted of 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia Biotech, St. Quentin Yvelines, France), 10 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 ng of hexamer (Pharmacia Biotech), and 50 U of RNAguard (Pharmacia Biotech), and the reaction was carried out over 60 min at 42°C and terminated by a final denaturing step of 5 min at 95°C.

Quantitation of IL-12/p40 transcripts.

Reverse transcripts (cDNA) were quantified using a PCR method involving coamplification of an internal standard (6). Briefly, standards are generated by the addition of 2 to 4 bp to wild-type DNA molecules; this addition of nucleotides allows the exchange of a unique restriction endonuclease site present within the wild-type molecule for a new one. This nucleotide addition allows discrimination between the two amplicons after restriction endonuclease digestion. The equivalence between coamplified cDNA and standard DNA was determined following electrophoretic analysis of the digested amplicon products on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel.

PCRs were performed in a final 100-μl reaction volume and consisted of 1 to 10 μl of the diluted cDNA in a reaction mixture containing 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer [200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.55), 160 mM (NH4)2SO4, 25 mM MgCl2, 1.5 μg of bovine serum albumin per μl], 100 pmol of each primer, 1 μl of a 3.47 mM concentration of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia Biotech), a defined copy number of the standard plasmid, and 0.5 to 2.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Biotaq; Bioprobe) according to the enzyme batch. A hot start was applied for 4 min at 95°C and followed by a hold at 80°C, before addition of the Taq DNA polymerase in a 20 μl volume in complete 1× reaction buffer. The amplification started with a denaturation step at 94°C for 1 min, an annealing step at 61°C for 1 min, and an extension step at 72°C (40 times) and ended with an extension for 10 min at 72°C. The primers used were β-ACTIN (5′-GGACTCCTATGTGGGTGACGAGG, 3′-GGGAGAGCATAGCCCTCGTAGAT) and IL-12/p40 (5′-CTGCCACAAAGGAGGCGAGACCTC, 3′-ATATTTATTCTGCTGCCGTGCTTC).

To eliminate the variations due to the RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis steps, quantification of IL-12/p40 transcripts within a given sample was expressed with respect to a fixed number of β-actin copies (106). Variations between replicate quantitations of a given transcript in the same sample were ≤25%.

Inoculation of mice with parasites.

L. major promastigotes were obtained from amastigotes recovered from ear lesions and grown in HOSMEM II medium as previously described (3). Stationary-phase promastigotes (5 × 105) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the right hind footpad. Preliminary dose-effect lesion curves were established for both resistant B10.D2 and susceptible BALB/c mice (data not shown). The course of infection was monitored by measuring the footpad swelling using a dial gauge caliper. Results are expressed as increases in footpad thickness.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Characterization of in vitro LACK secretion by recombinant L. monocytogenes.

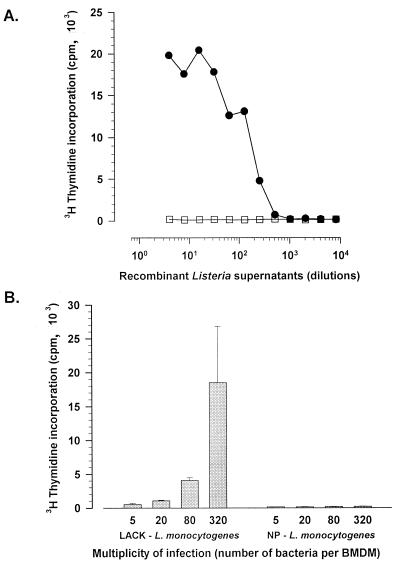

The entire gene encoding the LACK protein of L. major was inserted in frame with the L. monocytogenes listeriolysin (hly) signal sequence under the control of the hly promoter in order to drive secretion of the fusion protein by L. monocytogenes. LACK secretion efficiency by L. monocytogenes was ascertained by activation of the LACK-specific CD4 T-cell hybridoma 0D12 cell line (36) in two different ways. First, in vitro secretion in the bacterial culture medium was determined. When added to MHC class II-expressing BMDM, proteins from the bacterial supernatants were able to stimulate 0D12 cells to release IL-2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A) while control proteins from the supernatants of a recombinant L. monocytogenes expressing an unrelated protein, the NP of the LCMV (15), were inefficient. The level of LACK secretion was estimated to be 0.15 ng per 106 bacteria after an overnight culture in brain heart infusion agar at 37°C. Second, BALB/c BMDM infected with LACK-L. monocytogenes were able to activate 0D12 cells (Fig. 1B), thus showing that LACK was secreted and processed efficiently during in vitro cell infection by delivering the I-Ad epitope to the MHC class II molecules on the cell surface.

FIG. 1.

Efficient expression of LACK by a recombinant L. monocytogenes was measured by activation of a LACK-specific T-cell hybridoma, either with serial twofold dilutions of TCA-precipitated (see Materials and Methods) bacterial culture supernatants from LACK-L. monocytogenes (filled circles) or from NP-L. monocytogenes as a negative control (open squares) in the presence of BALB/c BMDM as APC (A) or with LACK-L. monocytogenes- or NP-L. monocytogenes-infected BALB/c BMDM (B). IL-2 secretion was quantified by [methyl-3H]thymidine incorporation into CTLL-2 cells as described in Materials and Methods.

Immunization with LACK-L. monocytogenes induces LACK-reactive CD4 Th1 T lymphocytes.

Immunization with LACK-L. monocytogenes was carried out in the H-2d BALB/c and B10.D2 mice, susceptible and resistant, respectively, to L. major infection. Expansion of LACK-reactive T lymphocytes was studied in spleen at various time points after a single i.v. injection of LACK-L. monocytogenes. The LACK-dependent T-lymphocyte stimulation was very brief, since in vivo expression of LACK was short-lived due to rapid elimination of the recombinant plasmid: only 1% of the injected bacteria still harbored the plasmid after 24 h (data not shown). This allowed us to mimic the physiological short-lived presentation of the LACK antigen to the immune system during L. major infection as previously reported (7, 36).

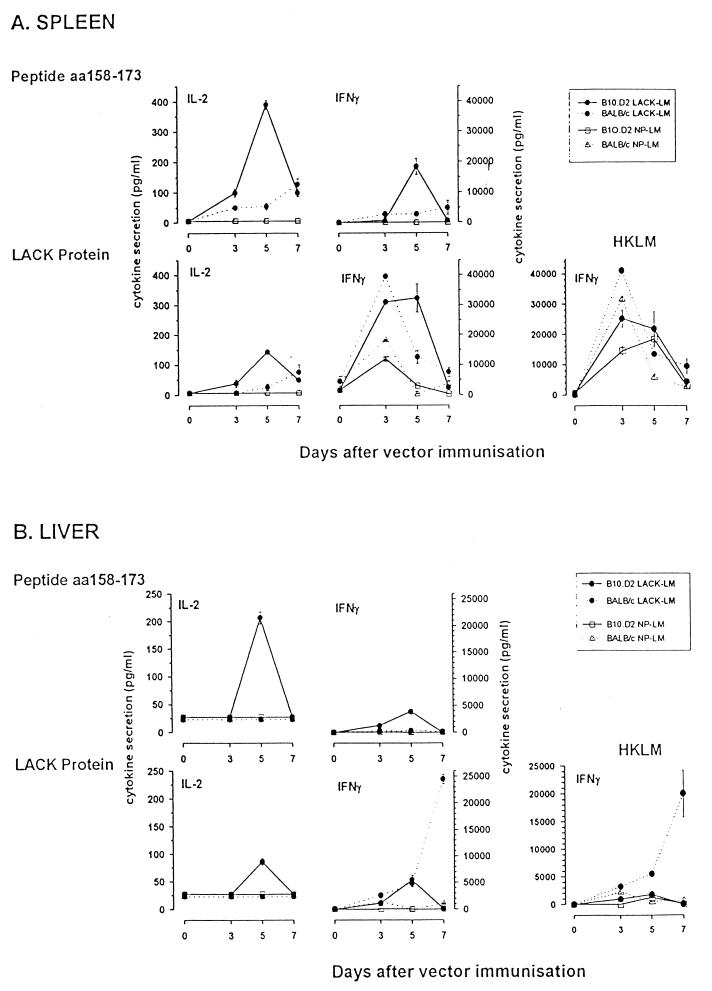

In spleens of B10.D2 mice, the peak of the immune response after LACK-L. monocytogenes immunization occurred at day 5 (Fig. 2A); the cytokine profile was consistent with expansion of Th1 CD4 T cells secreting IFN-γ and IL-2 after reactivation with either the LACK protein or the LACK158–173 peptide. No IL-4 secretion could be detected at any time point (data not shown). Depletion and enrichment experiments showed that the IFN-γ-secreting cells were Thy1+ CD4 T lymphocytes (Table 1). In spleens of BALB/c mice, the T-cell immune response directed towards the LACK158–173 peptide was weak and slowly peaked at day 7 (Fig. 2A); no cytokine secretion could be detected at days 10 and 14, as measured by ELISA for IFN-γ and by CTLL-2 cell proliferation for IL-2 and IL-4 (data not shown). However, when restimulation was carried out with the LACK protein, a high level of IFN-γ secretion was transiently observed at day 3; one-third of the response was LACK independent, since it was observed with splenic cells from control mice immunized with NP-L. monocytogenes. No IL-4 secretion could be detected at any time point (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of the LACK-specific immune response in B10.D2 mice (straight lines) and BALB/c mice (broken lines) after a single i.v. inoculation of LACK-L. monocytogenes (filled symbols) or NP-L. monocytogenes as a negative control (open symbols). Ex vivo reactivation of spleen (A) or liver (B) lymphoid cells (4 × 105 cells per well) was carried out in the presence of the LACK158–173 peptide (7.5 μM), the LACK protein (2.5 μg/ml), or HKLM (108 organisms/ml). IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion levels in the supernatants were quantified by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as means of results of triplicate experiments ± SEM. aa, amino acids.

TABLE 1.

Effects of Thy1 or CD4 depletion and CD4 or CD8 enrichment on IFN-γ secretion by B10.D2 splenocytes on day 5 after LACK-L. monocytogenes inoculationa

| Expt | Treatment | Mean IFN-γ secretion (pg/ml) ± SEM after stimulation with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LACK158–173 | LACK | HKLM | OVA | ||

| 1 | None | 9,119 ± 215 | 19,130 ± 999 | 13,980 ± 234 | <49 |

| Complement | 5,992 ± 481 | 19,239 ± 946 | 19,546 ± 617 | <49 | |

| Anti-Thy1 + complement (90%) | <49 | 104 ± 94 | 369 ± 105 | <49 | |

| CD4 depletion (98%) | <49 | 111 ± 108 | 2,787 ± 188 | <49 | |

| 2 | None | 31,165 | 39,960 ± 1,170 | 35,147 ± 5,633 | ND |

| Complement | 35,120 ± 3,518 | 36,709 ± 5,765 | 37,608 | ND | |

| Anti-Thy1 + complement (98%) | 367 ± 148 | 452 | 452 | ND | |

| 3 | None | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ND |

| CD4 depletion (100%) | 131 ± 142 | 486 ± 116 | 229 ± 110 | ND | |

| 4 | None | 19,133 ± 1,877 | 22,100 ± 351 | 23,933 ± 2,775 | 78 ± 50 |

| CD4 enrichment (88%) | 11,767 ± 1,401 | 19,433 ± 351 | 12,833 ± 802 | ND | |

| CD8 enrichment (86%) | 36 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 | 42 ± 3 | ND | |

Ex vivo restimulation was carried out on 4 × 105 cells per well as described in Materials and Methods, with either the LACK158–173 peptide (7.5 μM), the LACK protein (2.5 μg/ml), HKLM LUT12 (108/ml), or an unrelated antigen (OVA, 5 μg/ml). Thy1 depletion was complement dependent. Quantifications of CD4 depletion and CD4 or CD8 enrichment were done by magnetic separation (two runs in experiment 1 and one run in experiments 3 and 4). Depletion and enrichment efficiencies are shown in parentheses. IFN-γ was quantified as described for Fig. 2. ND, not done.

Following their expansion in the lymphoid organs, and primarily the spleen, these LACK-reactive T cells can be recruited extravascularly in the periphery, where they are expected to perform their functions. The liver is the main target organ of the immunizing live-vector L. monocytogenes delivered i.v., and the immune response was therefore studied in this organ at various time points after the immunization. After purification of the lymphoid cells present in the extravascular space of the liver (13), their reactivity towards LACK was analyzed (Fig. 2B). In livers of B10.D2 mice, LACK-reactive T cells were detected only on day 5; the cytokine profile (IL-2 and IFN-γ) was consistent with recruitment of Th1 T cells. In contrast, liver lymphoid cells from BALB/c mice secreted no IL-2 after ex vivo peptide or protein restimulation. No IFN-γ secretion was observed after restimulation with the LACK158–173 peptide. However, at days 5 and 7 significant IFN-γ secretion occurred after restimulation with the LACK protein. This difference in results of restimulation with the LACK158–173 peptide and the LACK protein was found in three separate experiments and suggested the existence of another epitope. No IL-4 secretion could be detected at any time point studied in mice of both strains.

The global T-cell response directed against L. monocytogenes was also analyzed by using as the restimulating antigen HKLM. A high level of IFN-γ secretion was observed in the spleens of LACK-L. monocytogenes- and NP-L. monocytogenes-immunized BALB/c and B10.D2 mice between days 3 and 5 (Fig. 2A). Depletion and enrichment experiments showed that the IFN-γ-secreting cells were Thy1+ CD4 T lymphocytes (Table 1). In one experiment, some residual IFN-γ secretion could be observed after CD4 depletion and could be related to the remaining presence of γδ T cells or NK cells that are recruited during the primary phase of Listeria infection (30, 43). Almost no response could be detected in liver (Fig. 2B), except in BALB/c mice, where IFN-γ-secreting T cells were detected from day 3.

Early cytokine profile of LACK-reactive T cells from LACK-L. monocytogenes-immunized mice recovered from draining lymph nodes during L. major infection.

The ability of primed LACK-reactive T cells generated by the Listeria immunization to be recruited within the draining lymph node was tested during the early phase of a leishmanial infection. Two weeks after immunization with LACK-L. monocytogenes, BALB/c and B10.D2 mice were infected s.c. with L. major and on day 3 the presence of LACK-reactive CD4 T lymphocytes in the lymph node draining the infected site, through cytokine secretion after specific in vitro reactivation, was characterized. When cells from the contralateral lymph node were used as negative controls, no IL-2, IL-4, or IFN-γ secretion could be detected in either resistant or susceptible mice (data not shown).

Reactivation of lymph node cells from LACK-L. monocytogenes-immunized B10.D2 mice with LACK (peptide or protein) led to significant IFN-γ secretion, no significant IL-2 secretion, and no IL-4 secretion on day 3 (Table 2), compared to secretion levels in nonreactivated cells. Reactivation of lymph node cells from LACK-L. monocytogenes-immunized BALB/c mice with LACK (peptide or protein) led to significant IFN-γ secretion on day 3 (Table 2), compared to the secretion level in control BALB/c mice. Only a weak level of IL-4 secretion could be detected on day 3. The IFN-γ secretion observed on day 3 was abolished after Thy1 or CD4 depletion (Table 3). Lymph node cells from L. monocytogenes-NP-immunized BALB/c mice were found to be less reactive whatever the readout assay used.

TABLE 2.

Cytokine profile of LACK-reactive T cells recruited in the draining lymph node on day 3 after L. major infection in LACK-L. monocytogenes-immunized B10.D2 or BALB/c micea

| Cytokine secreted | Inoculum | Cytokine secretion (pg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B10.D2 mice

|

BALB/c mice

|

||||||

| No antigen | Peptide | Protein | No antigen | Peptide | Protein | ||

| IFN-γ | LACK-L. monocytogenes | 121 ± 4 | 1,743 ± 309* | 1,895 ± 773* | 109 ± 50 | 1,374 ± 113* | 1,856 ± 290* |

| None (control) | 61 ± 10 | 303 ± 207 | 638 ± 84 | 88 ± 39 | 162 ± 27 | 433 ± 107 | |

| NP-L. monocytogenes | 61 ± 8 | 138 ± 59 | 189 ± 87 | <49 | <49 | 74 ± 16 | |

| IL-4 | LACK-L. monocytogenes | <49 | <49 | <49 | 72 ± 11 | 121 ± 35 | 197 ± 39* |

| None (control) | <49 | <49 | <49 | 197 ± 51 | <49 | 68 ± 19 | |

| NP-L. monocytogenes | <49 | <49 | <49 | 221 ± 28 | <49 | <49 | |

| IL-2 | LACK-L. monocytogenes | 121 ± 4* | 103 ± 49 | 84 ± 35 | 447 ± 62* | 478 ± 168 | 572 ± 151 |

| None (control) | <49 | <49 | <49 | 255 ± 24 | 328 ± 35 | 313 ± 54 | |

| NP-L. monocytogenes | 60 ± 8 | <49 | <49 | 70 ± 13 | <49 | 52 ± 2 | |

Stationary-phase promastigotes (5 × 105) were inoculated s.c. in the right hind footpad 15 days after a single LACK-L. monocytogenes inoculation. Nonimmunized (controls) or NP-L. monocytogenes-immunized mice were used as negative controls. Popliteal lymph node cells were reactivated ex vivo (2 × 105 to 4 × 105 cells per well) in the presence of the LACK158–173 peptide (7.5 μM) or the LACK protein (2.5 μg/ml). IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 secretion levels in the supernatants were quantified by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as means of results of triplicate experiments ± SEM. The asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05) versus results with nonimmunized controls.

TABLE 3.

Effect of Thy1 or CD4 depletion on IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion by BALB/c lymph node cells isolated on day 3 after L. major footpad inoculation (5 × 105 promastigotes)a

| Treatment | Cytokine secretion (pg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ

|

IL-4

|

|||||

| Without antigen | LACK158–173 | LACK protein | Without antigen | LACK158–173 | LACK protein | |

| None | <49 | 1,650 ± 378 | 4,424 ± 1,286 | <49 | <49 | <49 |

| CD4 depletion (100%) | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 |

| Thy1 depletion (90%) | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 | <49 |

Ex vivo restimulation of 2 × 105 to 4 × 105 cells per well was carried out as described in Materials and Methods, with either the LACK158–173 peptide (7.5 μM) or the LACK protein (2.5 μg/ml). Thy1 depletion was complement dependent. CD4 depletion was done by magnetic separation (two runs). Depletion efficiencies are shown in parentheses. IFN-γ and IL-4 were quantified as described in the footnote to Table 2.

Protective function of the LACK-reactive T cells generated by LACK-L. monocytogenes immunization.

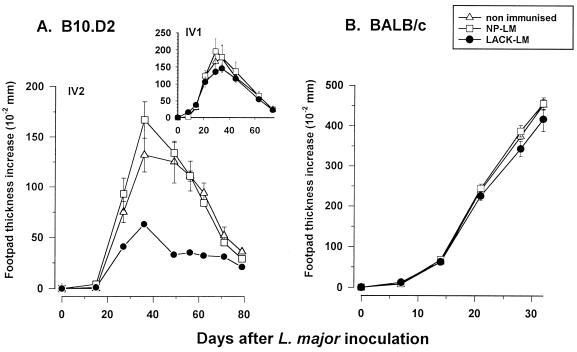

The potential efficiency of LACK-L. monocytogenes immunization on the control of an L. major infection was tested in both resistant and susceptible mice. In resistant B10.D2 mice (Fig. 3A), control of lesion progression could be observed only after two injections of LACK-L. monocytogenes; lesion development was slower than in the control groups and reached a lower plateau, and this plateau was maintained throughout the whole course of the clinical process. In contrast, the characteristic progressive disease in susceptible BALB/c mice could not be restrained (Fig. 3B). Even infection with a lower dose of parasites (3 × 104) close to the last inoculation of LACK-L. monocytogenes (day 8) or reinjections of LACK-L. monocytogenes when footpad thickness increases reached 2 to 3 mm in order to boost the anti-LACK immune response did not modify the progression of the lesions (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Protective status of B10.D2 mice and BALB/c mice after LACK-L. monocytogenes inoculation. (A) B10.D2 mice received one (see insert) or two (on days 0 and 22) i.v. injections of LACK-L. monocytogenes or NP-L. monocytogenes. Two weeks later, 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 stationary-phase promastigotes were inoculated s.c. into the right hind footpad and the resulting footpad swelling was monitored. (B) BALB/c mice received three injections of LACK-L. monocytogenes or NP-L. monocytogenes at days 0, 16, and 46. Five weeks later, 4.5 × 105 stationary-phase NIH 173 promastigotes were inoculated s.c. into the right hind footpad and the resulting footpad swelling was monitored. Results are expressed as means ± SEM (five or six mice per group). LM, L. monocytogenes.

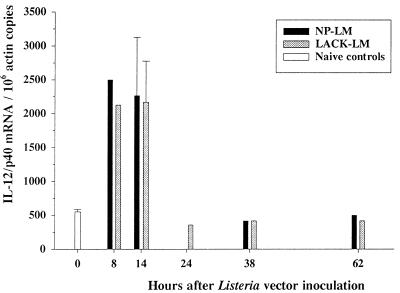

The ability of our L. monocytogenes recombinant vectors expressing LACK and LACK-NP to stimulate in vivo IL-12 expression at the mRNA level was checked by quantitative PCR (Fig. 4). A four- to fivefold increase in the quantity of IL-12/p40 transcripts was observed in spleen at 8 and 14 h of Listeria infection with either vector.

FIG. 4.

Quantitative analysis of IL-12/p40 mRNA levels in spleens of LACK-L. monocytogenes- and NP-L. monocytogenes-inoculated BALB/c mice. Splenic total RNAs were extracted at various time points after the inoculation of 5 × 107 LACK-L. monocytogenes or NP-L. monocytogenes cells, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as numbers of IL-12/p40 transcripts per 106 copies of actin mRNA and are the sums of results of three separate experiments. Variation in the actin mRNA quantifications in the various samples was less than 3% (0.99 ± 0.03 × 106 copies/ng of total RNA; means ± SEM; n = 14). LM, L. monocytogenes.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we analyzed the CD4 immune response generated by a recombinant attenuated Listeria strain expressing a parasite antigen, the LACK protein of L. major. Our system enabled us to use this foreign antigen and its well-defined I-Ad epitope as a comarker of the naturally processed listerial proteins and to trace in vivo the CD4 immune response generated in the course of a short-lived listerial infection. Our study showed that the attenuated L. monocytogenes actA mutant (25) was efficient in delivering in vivo the LACK protein for further processing along the MHC class II pathway. Evaluation of the ability of L. monocytogenes as a live recombinant vector to induce CD4 T cells reactive to the expressed foreign antigen has been studied only recently in an HIV peptide presentation model in vitro (19) and in vivo (28). Other live bacterial vectors expressing LACK, namely, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Mycobacterium bovis BCG, have also been studied in vivo with the LACK model. In these model systems, LACK-reactive T cells could not be detected after immunization (N. Glaichenhaus, unpublished results).

Reports have shown that LACK is presented in vitro by MHC class II-expressing mononuclear phagocytes only during the first hours following infection with stationary-phase L. major promastigotes (7, 36). Furthermore, macrophages infected with metacyclic promastigotes or amastigotes only weakly restimulated or could not restimulate the LACK-specific-T-cell hybridoma cell line 0D12, respectively (7, 36). Those reports suggest that the I-Ad LACK peptide may be accessible to the immune system only at a critical early period of Leishmania infection. The use of a plasmid construct enabled us to mimic the short-lived physiological presentation of the LACK I-Ad peptide to the immune system during L. major infection and to test its ability to induce CD4 T cells of the Th1 phenotype, which could exert a protective function against parasite infection.

The peak of IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion detected on day 5 in spleen may reflect the in situ expansion of LACK-reactive T cells or their recruitment in infected foci, since the spleen is at the same time a lymphoid organ and a target of Listeria infection. The former phenomenon may be considered predominant, if one assumes that the dynamics observed in the liver, which is a nonlymphoid organ, reflect the importance of the recruitment observed in the infectious sites, whatever the organ considered. The anti-LACK immune response faltered on day 7 in spleen. This decrease in the measured T-cell response is most probably related to the release of the LACK-reactive T cells in the vascular compartment, where they could be later recruited in the periphery either as activated or memory T cells, or to apoptosis after interaction and activation with the infected APC. The presence of LACK-reactive T cells was transient in liver and can probably be related to the transient release of the LACK protein; clearance of L. monocytogenes actually occurred in 5 days in this organ.

The CD4 component of the anti-LACK immune response detected in spleen and liver was clearly with a Th1 cytokine secretion profile in mice of both strains, with secretion of IFN-γ occurring without any IL-4 after ex vivo LACK reactivation. This result is in accordance with the fact that wild-type L. monocytogenes is a well-known inducer of IL-12 secretion by macrophages (21, 27, 40, 42, 46). When LACK is injected as an immunogen into BALB/c mice, either as protein alone (18) or in incomplete (23) or complete Freund's adjuvant (29), significant IL-4 and IL-5 secretion is observed in the draining lymph node cell populations 1 to 2 weeks afterward. The fact that we did not observe any detectable amount of IL-4 after LACK-L. monocytogenes immunization suggests that our Listeria vector had at least transiently prevented the Th2 differentiation of LACK-reactive T lymphocytes or, alternatively, induced the deletion of the type 2, already differentiated cells.

These LACK-reactive T cells induced through L. monocytogenes immunization could be recruited efficiently in the lymph node draining an L. major-infected site, where they could be detected on day 3 after parasite inoculation and still exhibited a Th1 secretion pattern, characterized by a strong level of IFN-γ secretion. This strong level of IFN-γ secretion observed in the L. major-infected lymph node on day 3 might then favor a bias towards Th1 differentiation of the L. major-driven T-cell immune response, especially in susceptible BALB/c mice, and result in eventual protection in mice of both resistant and susceptible strains. Effectively, a more efficient control of the leishmanial infection was observed in the resistant B10.D2 mice but needed two immunizing inoculations of LACK-L. monocytogenes. However, in the susceptible BALB/c mice, the progression of the disease went on unabated. LACK-L. monocytogenes-immunizing boosts during infection did not modify the evolution of the lesions. This point suggests that IL-12 secretion after the LACK-L. monocytogenes boosts may have occurred too late during L. major infection to curb disease progression, as previously observed (41).

Why could the short-term immune response driven by L. monocytogenes, which is a powerful known IL-12 secretion inducer, not block the Th2 differentiation of the L. major-specific immune response under these experimental conditions? Some reports have shown that persistence of IL-12 production after immunization is important for time-sustained immunity (17). In our work, the attenuated Listeria persisted only a few days, 3 days in spleen and 5 days in liver (data not shown). Nevertheless, the recombinant attenuated L. monocytogenes vectors were able to significantly increase IL-12/p40 mRNA transcription in vivo. The duration of in vivo IL-12 secretion achieved under these experimental conditions might, however, be too short to ensure optimal efficacy. One way to trigger a more sustained IL-12 production would be to test a wild-type virulent L. monocytogenes which persists longer in its host. On the other hand, in vivo expression of LACK and its further use as a source of immunogenic peptides are very short-lived and, even if the stimulation of the immune system is sufficient to induce protection in B10.D2 mice, stronger antigenic stimulation may be needed to produce the same protective effect in BALB/c mice. In preliminary experiments, we have indeed observed that immunization with a chromosomal construct of a LACK-expressing ΔactA attenuated L. monocytogenes strain which expressed LACK during the whole period of infection was able to delay L. major lesion onset in BALB/c mice. More precise characterization of the effect of immunization with LACK chromosomal constructs in attenuated or wild-type L. monocytogenes on L. major lesion control is under way.

Viewed together, our results show that L. monocytogenes, as a live recombinant vector, in addition to being able to generate effector CD8 T lymphocytes in infection and tumor models, is able to generate in vivo CD4 T cells with a Th1 phenotype that can exert their antiparasite function, at least in L. major-resistant mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the Laboratoire des Listeria (J. Rocourt, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for expert identification of the recombinant listeriae, Jean-Claude Antoine for critical reading of the manuscript, and M. Dehbi, E. Maranghi, and K. Sebastien for their expertise with mice.

This work was supported by grants from the European Union (ER BICD18CT970252), Délégation Générale de l'Armement (no. 95/150), Institut Pasteur, and the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MENRT). Neirouz Soussi was a recipient of a grant from the Fondation Marcel Mérieux.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso L C, Scharton T M, Vieira L Q, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263:235–237. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K E. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkaid Y, Jouin H, Milon G. A method to recover, enumerate and identify lymphomyeloid cells present in an inflammatory dermal site: a study in laboratory mice. J Immunol Methods. 1996;199:5–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell D J, Shastri N. Bacterial surface proteins recognized by CD4+ T cells during murine infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1998;161:2339–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colle J H, Falanga P B, Singer M, Hevin B, Milon G. Quantitation of messenger RNA by competitive RT-PCR: a simplified read out assay. J Immunol Methods. 1997;210:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courret N, Prina E, Mougneau E, Saraiva E M, Sacks D L, Glaichenhaus N, Antoine J-C. Presentation of the Leishmania antigen LACK by infected macrophages is dependent upon the virulence of the phagocytosed parasites. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:762–773. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<762::AID-IMMU762>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czuprynski C J, Canono B P, Henson P M, Campbell P A. Genetically determined resistance to listeriosis is associated with increased accumulation of inflammatory neutrophils and macrophages which have enhanced listericidal activity. Immunology. 1985;55:511–518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erb K J, Blank C, Moll H. Susceptibility to Leishmania major in IL-4 transgenic mice is not correlated with the lack of a Th1 immune response. Immunol Cell Biol. 1996;74:239–244. doi: 10.1038/icb.1996.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geginat G, Lalic M, Kretschmar M, Goebel W, Hof H, Palm D, Bubert A. Th1 cells specific for a secreted protein of Listeria monocytogenes are protective in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;160:6046–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Taladriz S, Marquet A, Larraga V. Molecular cloning, cell localization and binding affinity to DNA replication proteins of the p36/LACK protective antigen from Leishmania infantum. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:909–916. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goossens P L, Marchal G, Milon G. Early influx of Listeria-reactive T lymphocytes in liver of mice genetically resistant to listeriosis. J Immunol. 1988;141:2451–2455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goossens P L, Jouin H, Marchal G, Milon G. Isolation and flow cytometric analysis of the free lymphomyeloid cells present in murine liver. J Immunol Methods. 1990;132:137–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90407-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goossens P L, Marchal G, Milon G. Transfer of both protection and delayed-type hypersensitivity against live Listeria is mediated by the CD8+ T cell subset: a study with Listeria-specific T lymphocytes recovered from murine infected liver. Int Immunol. 1992;4:591–598. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goossens P L, Milon G, Cossart P, Saron M F. Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes as a live vector for induction of CD8 T cells in vivo: a study with the nucleoprotein of the lymphocyticchoriomeningitis virus. Int Immunol. 1995;7:797–805. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goossens P L, Montixi C, Saron M F, Rodriguez M, Zavala F, Milon G. Listeria monocytogenes: a live vector able to deliver heterologous protein within the cytosol and to drive a CD8 dependent T cell response. Biologicals. 1995;23:135–143. doi: 10.1006/biol.1995.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurunathan S, Prussin C, Sacks D L, Seder R A. Vaccine requirements for sustained cellular immunity to an intracellular parasitic infection. Nat Med. 1998;4:1409–1415. doi: 10.1038/4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurunathan S, Sacks D L, Brown D R, Reiner S L, Charest H, Glaichenhaus N, Seder R A. Vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen confers protective immunity to mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1137–1147. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzman C A, Saverino D, Medina E, Fenoglio D, Gerstel B, Merlo A, Li Pira G, Buffa F, Chakraborty T, Manca F. Attenuated Listeria monocytogenes carrier strains can deliver an HIV-1 gp120 T helper epitope to MHC class II-restricted human CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1807–1814. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<1807::AID-IMMU1807>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh B, Schrenzel M D, Mulvania T, Lepper H D, DiMolfetto-Landon L, Ferrick D A. In vivo cytokine production in murine listeriosis. Evidence for immunoregulation by gamma delta+ T cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh C S, Macatonia S E, Tripp C S, Wolf S F, O'Garra A, Murphy K M. Development of TH1 CD4 T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen E R, Shen H, Wettstein F O, Ahmed R, Miller J F. Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vehicle and a probe for studying cell-mediated immunity. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:147–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julia V, Rassoulzadegan M, Glaichenhaus N. Resistance to Leishmania major induced by tolerance to a single antigen. Science. 1996;274:421–423. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karasuyama H, Melchers F. Establishment of mouse cell lines which constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin 2, 3, 4 or 5, using modified cDNA expression vectors. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:97–104. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocks C, Gouin E, Tabouret M, Berche P, Ohayon H, Cossart P. L. monocytogenes-induced actin assembly requires the actA gene product, a surface protein. Cell. 1992;68:521–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90188-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Launois P, Maillard I, Pingel S, Swihart K G, Xenarios I, Acha-Orbea H, Diggelmann H, Locksley R M, MacDonald H R, Louis J A. IL-4 rapidly produced by V beta 4 V alpha 8 CD4+ T cells instructs Th2 development and susceptibility to Leishmania major in BALB/c mice. Immunity. 1997;6:541–549. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80342-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Kurlander R J. Analysis of the interrelationship between IL-12, TNF-alpha, and IFN-gamma production during murine listeriosis. Cell Immunol. 1995;163:260–267. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mata M, Paterson Y. Th1 T cell responses to HIV-1 gag protein delivered by a Listeria monocytogenes vaccine are similar to those induced by endogenous listerial antigens. J Immunol. 1999;163:1449–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McSorley S J, Rask C, Pichot R, Julia V, Czerkinsky C, Glaichenhaus N. Selective tolerization of Th1-like cells after nasal administration of a cholera toxoid-LACK conjugate. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:424–432. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<424::AID-IMMU424>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mielke M E, Peters C, Hahn H. Cytokines in the induction and expression of T-cell-mediated granuloma formation and protection in the murine model of listeriosis. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris L, Troutt A B, McLeod K S, Kelso A, Handman E, Aebischer T. Interleukin-4 but not gamma interferon production correlates with the severity of murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3459–3465. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3459-3465.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mougneau E, Altare F, Wakil A E, Zheng S, Coppola T, Wang Z E, Waldmann R, Locksley R M, Glaichenhaus N. Expression cloning of a protective Leishmania antigen. Science. 1995;268:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.7725103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.North R J, Dunn P L, Conlan J W. Murine listeriosis as a model of antimicrobial defense. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prat M, Gribaudo G, Comoglio P M, Cavallo G, Landolfo S. Monoclonal antibodies against murine γ interferon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4515–4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prina E, Jouanne C, de Souza Lao S, Szabo A, Guillet J G, Antoine J C. Antigen presentation capacity of murine macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes. J Immunol. 1993;151:2050–2061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prina E, Lang T, Glaichenhaus N, Antoine J C. Presentation of the protective parasite antigen LACK by Leishmania-infected macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;156:4318–4327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reiner S L, Locksley R M. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safley S A, Cluff C W, Marshall N E, Ziegler H K. Role of listeriolysin-O (LLO) in the T lymphocyte response to infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Identification of T cell epitopes of LLO. J Immunol. 1991;146:3604–3616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanderson S, Campbell D J, Shastri N. Identification of a CD4+ T cell-stimulating antigen of pathogenic bacteria by expression cloning. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1751–1757. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song F, Matsuzaki G, Mitsuyama M, Nomoto K. Differential effects of viable and killed bacteria on IL-12 expression of macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;156:2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sypek J P, Chung C L, Mayor S E, Subramanyam J M, Goldman S J, Sieburth D S, Wolf S F, Schaub R G. Resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis: interleukin 12 initiates a protective T helper type 1 immune response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1797–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tripp C S, Gately M K, Hakimi J, Ling P, Unanue E R. Neutralization of IL-12 decreases resistance to Listeria in SCID and C.B-17 mice. Reversal by IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 1994;152:1883–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unanue E R. Studies in listeriosis show the strong symbiosis between the innate cellular system and the T-cell response. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiskirch L M, Paterson Y. Listeria monocytogenes: a potent vaccine vector for neoplastic and infectious disease. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:159–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokogawa K, Kawata S, Nishimura S, Ikeda Y, Yoshimura Y. Mutanolysin, bacteriolytic agent for cariogenic streptococci: partial purification and properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974;6:156–165. doi: 10.1128/aac.6.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhan Y, Cheers C. Control of IL-12 and IFN-gamma production in response to live or dead bacteria by TNF and other factors. J Immunol. 1998;161:1447–1453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]