Abstract

Optimization of manganese-substituted iron oxide nanoferrites having the composition MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) has been achieved by the chemical co-precipitation method. The crystallite size and phase purity were analyzed from X-ray diffraction. With increases in Mn2+ concentration, the crystallite size varies from 5.78 to 9.94 nm. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis depicted particle sizes ranging from 10 ± 0.2 to 13 ± 0.2 nm with increasing Mn2+ substitution. The magnetization (Ms) value varies significantly with increasing Mn2+ substitution. The variation in the magnetic properties may be attributed to the substitution of Fe2+ ions by Mn2+ ions inducing a change in the superexchange interaction between the A and B sublattices. The self-heating characteristics of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) nanoparticles (NPs) in an AC magnetic field are evaluated by specific absorption rate (SAR) and intrinsic loss power, both of which are presented with varying NP composition, NP concentration, and field amplitudes. Mn0.75Fe0.25Fe2O4 exhibited superior induction heating properties in terms of a SAR of 153.76 W/g. This superior value of SAR with an optimized Mn2+ content is presented in correlation with the cation distribution of Mn2+ in the A or B position in the Fe3O4 structure and enhancement in magnetic saturation. These optimized Mn0.75Fe0.25Fe2O4 NPs can be used as a promising candidate for hyperthermia applications.

Introduction

Due to their unique physical features, known biocompatibility, ease of production, and highly adjustable nature at the nanoscale, maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles (NPs) are especially well suited for various biomedical applications.1,2 Magnetization in Fe3O4 can be tuned by replacing iron ions with transition metal cations, especially manganese ions, which have higher magnetic moments.3 It is explored for many applications which include catalysts, humidity sensors, biomedicine, MRI, microwave technologies, drug delivery, and magnetic fluid hyperthermia.2 The properties of manganese ferrites such as their high electrical resistance, high curie temperature (bulk MnFe2O4 is Tc 577 K), low coercivity value, and a low eddy current loss allow them to serve a wide range of applications.4,5 The integration of secondary cations Mn2+ in Fe3O4 and synthesis reproducibility have been studied.6 In the past decade, the general term MFe2O4 (M = Co, Mg, Ni, etc.) of spinel ferrites has been widely used for a variety of technological and biomedical applications.7,8 The magnetic and electrical properties of these compounds strongly depend on the synthesis process, chemical content, annealing temperature, and cation distribution. The cation distribution in spinel ferrite materials among two interstitial sites of the structure is one of the most challenging aspects of studying these materials due to its effect on the properties of ferrites.9 Shahane et al. reported the MnFe2O4 magnetic NPs (MNPs) showing the antiparallel spin moments among Fe3+, Mn2+, and Fe2+ ions at A-sites and inverse spinel structures.10 The polycrystalline spinel ferrite CoxNi1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) was obtained by the sol–gel autocombustion method with the Co substitution. In Co2+-substituted nickel ferrite, the density is higher than Ni2+ ions, owing to the higher magnetocrystalline anisotropy and the smaller particle size. The saturation magnetization (Ms) was increased to x = 0.8, at which point there was a small reduction in Ms for CoFe2O4.11 There have been several proposals for substituted magnetite NPs, MxFe3–xO4 (M = Ni, Zn, Mn, and Co, 0 < x ≤ 1) for various bio-applications since their magnetic properties can be easily controlled by replacing divalent or trivalent metal ions without modifying the crystal structure by either replacing them completely or partially.

MnxFe3–xO4 NPs among these ferrites show stronger magnetization (Ms), low coercivity (Hc), and low inherent toxicity than other doped ferrite materials and in some cases even higher Ms than the best studied and currently available iron oxide NPs, along with good chemical stability and biocompatibility. Additionally, manganese ferrites can be modified by tuning hyperthermic therapeutic temperature which is possibly suitable for self-controlled hyperthermia treatment.8,12 The formula of a metal ferrite material is most precisely described as (MxFe1–x)[MxFe2–x]O4, “A” tetrahedral site and “B” octahedral site are denoted, respectively, by parentheses and square brackets, and x is the inversion parameter quantifying the distribution of M2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ cations among these sites. The manganese substitution was performed in crystals by changing the molar concentration of Mn2+, and a variation of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 with a change in molar ratios of Mn2+ to Fe2+ were synthesized, where “x” varies from 0 to 0.75. Manganese ferrites (MnFe2O4) are presented as one of the most promising materials due to their magnetization capacity.13 Yousuf et al. synthesized yttrium-substituted manganese ferrites using a reverse-micelle micro-emulsion method and found that with the increase of the yttrium content, the lattice constant increased.14 A variety of metal ions in spinel ferrite lead to structural distortions, which affect the material’s physical and structural characteristics, as well as structural parameters.15 The distribution of ions between the tetrahedral and octahedral sites, as well as their interaction, ultimately decides the magnetic characteristics of NPs.16

There are different methods for the synthesis of ferrite NPs, such as chemical co-precipitation,3 a sol–gel autocombustion method,17 combustion synthesis,18 ultrasonically assisted co-precipitation method,19 and thermal decomposition method.20 Thermal decomposition and co-precipitation methods are generally used for the synthesis of NPs. In an organic medium, ferrite NPs of a controlled size can be easily obtained using the former method. Chemical co-precipitation is the simplest methods for the synthesis of MNPs in an aqueous solution. By optimizing the synthesis parameters such as concentration, pH, temperature, the size of the NPs can be varied.10 Though there is a tremendous advancement in the field of material chemistry, obtaining MNPs with improved magnetic properties and monodisperse nature still poses challenges to the scientific community in this field.

Magnetic fluid hyperthermia is an application of MNPs in cancer and presents a non-invasive treatment option in which NPs at the tumor site raise to a temperature of 42–46 °C. The heating efficacy of MNPs is measured in terms of specific absorption rate (SAR), which largely relies on parameters such as size, shape of NPs, magnetization, strength of the applied field and frequency, and so forth. Cation distribution in ferrites also tends to affect the magnetic properties substantially.21,22 The temperature response by MNPs under AC magnetic field is also determined by interparticle interaction, particle concentration in the carrier liquid, viscosity, heat capacity, and surface modification.23 In the present work, a systematic evaluation of the substitution of Mn2+ into MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0) has been carried out by correlating induction heating studies of MNPs with cation distribution.

Experimental Section

Materials

The materials were used to synthesize MNPs: FeCl3·6H2O, ≥99%; FeCl2·4H2O, ≥99%; MnCl2·4H2O, ≥99%; and NaOH, ≥99% purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the chemicals were used without further purification and are water soluble.

Synthesis of Manganese Iron Oxide NPs

In the typical synthesis of Mn0.25Fe0.75Fe2O4 (0.25 mmol), manganese(II) chloride, (2 mmol) iron(III) chloride hexahydrate, and (0.75 mmol) iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate were separately dissolved in distilled water with constant stirring. Then, until the occurrence of co-precipitation at pH 12, (8 mmol) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added directly to the above solution as a precipitating agent and kept at 70–80 °C for 2 h. The precipitate was collected by magnetic decantation and washed with double-distilled water. The washed precipitate was dried at room temperature overnight. MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0) was prepared using the same procedure.

Characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of powder samples with various concentrations were recorded using Cu Kα radiation at the wavelength (λ) = 1.546 Å. The crystallite size of the samples was calculated using the Scherrer equation

| 1 |

where “Dxrd” is the crystalline size, “K” is the Scherrer constant, β is the FWHM (full width at half-maximum), and θ is the diffraction angle. The formula has been used to derive the lattice constant “a” using the calculated corresponding d values

| 2 |

X-ray density (dx) of the material

| 3 |

where “M” is the atomic weight and “N” is Avogadro’s number (6.022 × 1023 mol–1).

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy study of samples with different concentrations was obtained using an Alpha (II) Bruker unit in the range of 400–4000 cm–1. Transmission electron microscopy (2100F JEOL TEM) was employed to observe the size and shape of NPs. Magnetization–field (M–H) measurements were conducted at room temperature at fields up to 15 kOe using a vibrating sample magnetometer.

An EasyHeat 8310 (Ambrell, UK) was used to study induction heating of the as-prepared MNPs in a physiological medium at an applied fixed frequency of 277 kHz. The field amplitude was adjusted from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m.

Results and Discussion

Structure, Phase, and Morphology Analysis

The crystallographic structure and crystallite size were determined using the XRD patterns of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 NPs with (x = 0–1) in the 2θ range 20–80° and are shown in Figure 1a. The XRD patterns reveal broad peaks and crystallite sizes, and samples are crystalline in nature; their profiles are matched with JCPDS card nos. 00-019-0629 for Fe3O4 and 00-010-0319 for MnFe2O4. The XRD results confirm the formation of cubic ferrite with the space group Fd3m. An enlarged view of the high-intensity characteristic peak (311) shows a shift to lower angles with increasing Mn2+ substitution (Figure 1b). It is due to the expansion of the unit cell as Mn2+ ions are substituted in the magnetite structure.3 The increase in lattice constant (a) with an increase in Mn2+ is explained using ionic radii, where the radius of Mn2+ (0.80 Å) is larger than that of Fe2+ (0.77 Å) and Fe3+ (0.64 Å), causing lattice expansion; as a result, the lattice parameter increases from 0.8350 to 0.8409 nm due to unit cell dimension expansion.24

Figure 1.

(a) XRD patterns for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs and (b) shift view of the region around the (311) peak at different Mn2+ ions.

The inverse spinel manganese iron oxide will eventually expand when small-sized Fe3+ and Fe2+ ions are replaced with large-sized Mn2+ ions. The strain on an inverse spinel-type structure will be linear in the lattice because of the elastic deformation caused by substituting Mn2+ ions. This effect is because the spacing in the lattice plane changes and the peaks shift to lower 2θ positions (Figure 1b).25 The calculated lattice parameter “a” with different compositions is shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

The calculated crystallite size (Dxrd) of synthesized manganese iron oxide nanocrystals varies from 5.7 to 12.92 nm with varying Mn2+ concentrations. The calculated unit cell volume increases from 0.583 to 0.613 nm3, and the equivalent values of X-ray density (dx) decrease from 5.27 to 4.99 g/cm3 with the increase in Mn2+, respectively (Figure 2).26,27

Figure 2.

Variation of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs with Mn2+ content x in terms of their lattice parameter a (nm), crystallite size Dxrd (nm), and X-ray density dx (g/cm3).

Figure 3a,e,i shows the TEM images of manganese iron oxide NPs, and the corresponding histograms illustrate particle size distribution for three different compositions. The TEM analysis for samples MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.25, and 0.75) shows the particle size and distribution, which is in good agreement with those determined by XRD. The product contains agglomerated NPs with spherical and cubic forms, as can be seen in Figure 3. Also, (c,g,k) depict the equivalent selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of NPs. The picture shows spotty ring patterns, which are consistent with the XRD results, indicating that NPs have a good crystal structure. Figure 3b,f,j depicts the lattice fringes confirming the single nature of the core, with a lattice spacing of roughly 0.20–0.27 nm, which corresponds to the (311) lattice plane.28Figure 3d,h,l, provides the histogram, and formation of NPs with sizes around 7 ± 0.17 to 13 ± 0.2 nm is confirmed.

Figure 3.

Images of (a–d), (e–h), and (i–l) represent the TEM images, SAED patterns, and histograms of samples MnxFe1–xFe2O4 at x = 0, 0.25, and 0.75, respectively.

The chemical composition of the obtained MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs was studied using energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis (shown in Figure S1, Supporting Information). The analyzed results, as shown in the respective Figure S1, confirm the percentage of Mn, Fe, and O elements which are presented in Table1. The phase purity of samples confirms that samples conform to the expected composition ratio and confirms that stoichiometry is properly maintained during preparation, implying that the expected ratio is maintained during preparation.

Table 1. Stoichiometry % Concentration of the Constituent Elements of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs by EDX.

| sample MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x) | Mn | Fe | O |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 27.30 | 73.70 |

| 0.25 | 2.91 | 25.50 | 71.60 |

| 0.50 | 6.21 | 35.75 | 58.04 |

| 0.75 | 9.02 | 25.07 | 65.90 |

| 1.00 | 10.75 | 21.79 | 67.46 |

Cation Distribution

Nanomaterials present novel properties as compared to their bulk counterparts; strains on the surface or interface are most of the important basic quantities to a wide variety of domains.9,29 During compression or tension, nanoscale materials can modify their lattice parameters, thereby changing their intrinsic bond distances and electron energy levels. Calculations of the grain size and micro-strain created throughout the process were made using the line width FWHM (in radians) of the powder XRD lines. As a result of equation β, the width of the integral line is given by

| 4 |

where β′ and β″ are the contributions of grain size and strain, respectively, θ is the Bragg angle, ε is the strain, and “Dxrd” is the crystallite size. When the strain term β″ = 4ε tan θ is negligible, ε can be evaluated in terms of β. For various XRD lines corresponding to different planes, the integral line width is measured, and eq 4 can be simplified as

| 5 |

The values of β cos θ and 4 sin θ have a linear relationship. The strain (ε) evaluated from the intercept = λ/Dxrd on the y-axis when plotting β cos θ (y-axis) versus 4 sin θ (x-axis).

The strain measurements for each sample are shown in Figure 4. For all the sample, the linear difference of 4 sin θ with β cos θ can be seen. Strain measurement from the slope is more sensitive to increased Mn2+ content x, indicating that a larger amount of Mn2+ can be accommodated in the matrix of MnxFe1–xFe2O4. Differences in ionic size between the two cations account for the difference in cation distribution on tetrahedral and octahedral sites.30

Figure 4.

Strain graph of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

The spinel ferrites having structural and magnetic properties are affected by cation distribution in crystal lattices. An inverse phase cubic spinel structure has been observed for manganese iron oxide nanocrystals, with Fe2+ ions occupying B-sites and Mn2+, Fe3+ ions equally distributed in the A- and B-sites. Studies of cation dispersion in spinel ferrite give useful information for improving materials with desirable characteristics.31 In MnxFe(1–x)Fe2O4, XRD analysis was used to determine the distribution of cations Mn2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ among octahedral and tetrahedral sites. The cation distribution in spinel ferrite was determined by comparing experimentally measured diffraction intensities with those calculated for a wide number of hypothetical crystal forms. Various distribution parameters are used to calculate the intensity using the Burger formula for the planes32

| 6 |

F is the structural component, P is the multiplicity, and Lp is the Lorentz polarization factor in this equation.

| 7 |

The best information on cation distribution is obtained by comparing experimental and estimated intensity ratios for reflections whose intensities (i) are relatively independent of the oxygen parameter, (ii) change with the cation distribution in different ways, and (iii) do not differ significantly. Fe3+ ions have no preference for the lattice site and can occupy any of the two; Mn2+ ions can likewise occupy both sites. Mn2+ and Fe3+ ions have a strong A-site preference in MnxFe1–xFe2O4, while Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions occupy the B-sites.32 The following cation distribution can be proposed since MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) form inverse spinel

| 8 |

where y and z are the Mn2+ and Fe2+ ion concentrations at their respective sites and 0 ≤ x ≤ 1. The following equation and an acceptable cation distribution are used to determine the mean ionic radii of tetrahedral (A) and octahedral (B) sites (rA and rB)

| 9 |

| 10 |

Using the value of a, the radius of oxygen ion Ro = 1.32 Å, and, rA, the oxygen positional parameter (u) can be obtained as follows

| 11 |

With the increasing Mn2+ content x, it is apparent that rB decreases and rA increases. The relative value of Mn2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ occupancy with their different ionic radii in the tetrahedral site helps to explain the difference in calculated tetrahedral or octahedral radius. The oxygen positional parameter “u” rises to 0.401 from 0.382. If “u” = 3/8 = 0.375 in an ideal fcc structure, the “u” values of most ferrites are greater than this ideal value, indicating that the oxygen ions are transferred in such a way in the A–B interaction that the distance between A and O ions increases, while the distance between B and O ions decreases. As a result, the A–A interaction decreases, while the B–B interaction increases.9,18

Using the estimated values of rA and rB, the theoretical lattice parameter (ath) is determined as

| 12 |

Theoretical lattice constant values are shown in Table 2 for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) nanocrystals.

Table 2. Distribution of Cations among A- and B-Sites, ionic Radii of tetrahedral (rA) and octahedra sites (rB), oxygen parameter (u), theoretical lattice parameter (ath) and strain (ε).

| comp | A-site |

B-site |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | Mn2+ | Fe2+ | Fe3+ | Mn2+ | Fe2+ | Fe3+ | rA (Å) | rB (Å) | “u” (Å) | ath | strain |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.0 | 0.95 | 1.05 | 0.59 | 1.58 | 0.382 | 0.8352 | 0.7229 |

| 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.88 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 1.12 | 0.66 | 1.51 | 0.385 | 0.8405 | 0.7249 |

| 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.0 | 0.81 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 1.19 | 0.74 | 1.45 | 0.391 | 0.8423 | 0.7258 |

| 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.0 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 1.25 | 0.82 | 1.39 | 0.396 | 0.8435 | 0.7309 |

| 1.00 | 0.29 | 0.0 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.0 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 1.34 | 0.401 | 0.8497 | 0.7333 |

As the concentration of Mn2+ increases, the X-ray density rises linearly because the iron atom is lighter than the manganese atom. The distance between magnetic ions is calculated in the tetrahedral site LA and octahedral site LB.

| 13 |

| 14 |

Table 3 shows the calculated values for LA and LB. It is observed that with the increase in the Mn2+ content, the hopping length also increases.

Table 3. Hopping Length (LA) and (LB), Tetrahedral Bond Length (dAx), Octahedral Bond Length (dBx), Tetrahedral Edge (dAxE), and Shared (dBxE) and Unshared (dBxEu) Octahedral Edges as a Function of x for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

| sample MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x) | LA (nm) | LB (nm) | dAx (nm) | dBx (nm) | dAxE (nm) | dBxE (nm) | dBxEu (nm) | α | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.3617 | 0.2953 | 0.1894 | 0.2037 | 0.3095 | 0.2811 | 0.2954 | 0.4108 | 0.3871 |

| 0.25 | 0.3641 | 0.2973 | 0.1906 | 0.2051 | 0.3115 | 0.2830 | 0.2973 | 0.4155 | 0.2931 |

| 0.50 | 0.3647 | 0.2978 | 0.1910 | 0.2054 | 0.3121 | 0.2834 | 0.2979 | 0.4051 | 0.3908 |

| 0.75 | 0.3652 | 0.2982 | 0.1913 | 0.2057 | 0.3125 | 0.2838 | 0.2983 | 0.4117 | 0.1846 |

| 1.00 | 0.3679 | 0.3004 | 0.1925 | 0.2072 | 0.3148 | 0.2859 | 0.3005 | 0.4074 | 0.3426 |

According to eqs 15 and 16, one can calculate the shortest distance between A-site cations and oxygen ions and that between B-site cations and oxygen ions, respectively.

| 15 |

| 16 |

Equations 17–19 were used to determine the A-site edge “dAxE”, the shared B-site edge “dBxE”, and the unshared B-site edge “dBxEu”.

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

As shown in Table 3, substitution with Mn2+ indicates an increase in the octahedral bond distance dBx and the tetrahedral bond distance dAx. In manganese iron oxide nanocrystals, due to the extension of octahedral B-sites, differences between dAxE and dBxE increase because of the larger radius of Mn2+ ions compared to Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. As a result, the oxygen anions are displaced relative to each other, causing the tetrahedral A-sites to decrease. Because there is more covalent bonding at the A-sites than at the B-sites as a result of shrinkage, the force constant between the cations and anions increases. There is an increase in the value of tetrahedral edge “dAxE”, shared octahedral edge “dBxE”, and unshared octahedral edge “dBxEu” due to Mn2+ substitution, which is shown in Table 3. These modifications are due to Mn2+ greater ionic radius, which cause the octahedral site to expand while the tetrahedral site shrinks.33−35

In terms of rA, rB,ath, aexp, and r(O2–), the following relationships can be used to describe the degree of ionic packing (α) and the vacancy parameter (β).

| 20 |

| 21 |

The vacancy parameter reveals the presence of vacancies at both tetrahedral and octahedral sites and offers the normalized volume of the missing ions, which is a total measure of vacancy concentration in the spinel structure.36 The magnetic properties of spinel ferrite nanocrystals are attributed to octahedral and tetrahedral sites, as well as their relative strengths, which are affected by magnetic ion accumulation on the surfaces of these crystals’ inter-lattice and inter-sublattice interactions. Variations in the number of magnetic ions in both sites alter the magnetic properties. Ferrite nanocrystals substituted with Mn2+ expand the tetrahedral site resulting in an increase in the bond distance at the A-site. The structural features of ferrites are mostly influenced by the variation in bond distance between a cation and cation, as well as a cation and an anion, at various magnetic parameters.37

As the unit cell volume increases, all values of inter-ionic distances increase. This is because the smaller ionic radii Fe2+ is replaced by a more radially large Mn2+, which has a smaller interionic distance between ions (b, c, d, e, f) for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) nanocrystals. From Tables 4 and 5, it is observed that an increase in cation–anion length and cation–cation length with Mn2+ substituted resulted in a decreased superexchange strength compared to iron oxides.38 The inter-ionic lengths and angles between the cation–anion and cation–cation play a major and effective influence in magnetic interactions. Different configurations of the ion pairs with favorable angles for the individual magnetic interactions and inter-ionic distances give the cation–anion distances p, q, r, and s, as well as the cation–cation distances (b, c, d, e, and f) and the respective bond angles θ1, θ2, θ3, θ4, and θ5. The inter-ionic distances are determined by the crystalline structure and magnetic characteristics.36

Table 4. Calculation of Distances between Cations and Anions and between Cations and Cations for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) Nanocrystals.

| sample MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x) | p (nm) | q (nm) | r (nm) | s (nm) | b (nm) | c (nm) | d (nm) | e (nm) | f (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.20 | 0.1808 | 0.3462 | 0.5512 | 0.2953 | 0.3462 | 0.3617 | 0.5426 | 0.5115 |

| 0.25 | 0.2102 | 0.1820 | 0.3486 | 0.5549 | 0.2973 | 0.3486 | 0.3641 | 0.5462 | 0.5149 |

| 0.50 | 0.2106 | 0.1823 | 0.3492 | 0.5559 | 0.2978 | 0.3492 | 0.3647 | 0.5471 | 0.5158 |

| 0.75 | 0.2109 | 0.1826 | 0.3496 | 0.5566 | 0.2982 | 0.3496 | 0.3652 | 0.5479 | 0.5165 |

| 1.00 | 0.2124 | 0.1839 | 0.3522 | 0.5607 | 0.3004 | 0.3522 | 0.3679 | 0.5519 | 0.5203 |

Table 5. Calculated Values of Hopping Lengths and Inter-ionic Bond Angles for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) Nanocrystals.

| sample MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x) | LA (nm) | LB (nm) | θ1 | θ2 | θ3 | θ4 | θ5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.3617 | 0.2953 | 125.24 | 154.93 | 90.00 | 68.11 | 79.99 |

| 0.25 | 0.3641 | 0.2973 | 125.30 | 154.82 | 90.01 | 68.10 | 79.98 |

| 0.50 | 0.3647 | 0.2978 | 125.28 | 154.74 | 89.98 | 68.10 | 79.97 |

| 0.75 | 0.3652 | 0.2982 | 123.20 | 154.86 | 89.97 | 68.11 | 79.99 |

| 1.00 | 0.3679 | 0.3004 | 123.27 | 154.85 | 90.00 | 68.11 | 79.99 |

The following equations are used to calculate these values, as shown in Table 4 taking into account the experimental value of the lattice constant and oxygen parameters.

|

22 |

As a result of considering the following equations with the inter-ionic lengths measured, we can obtain the bond angles for manganese iron oxide, and these values are given in Table 5.

|

23 |

Because these angles are related to A–B and A–A interactions, a rise in these angles verifies the strength of these bonds as bond length and bond angle both increase with the substitution of Mn2+.

FTIR Analysis

Figure 5 shows the FTIR absorption spectra of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs in the range of 4000–400 cm–1. The formation of the spinel ferrite phase has been confirmed by an FTIR analysis. There are distinct intensity bands in the FTIR spectra corresponding to the covalent linkages between NPs, such as the MT–O–MO stretching band at ∼600–500 cm–1, where MT and MO represent the tetrahedral and octahedral sites. The band positions of the synthesized Mn2+-substituted nanoferrites are given in Table 6.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

Table 6. Tetrahedral Band (υ1), Octahedral Band (υ2), and Force Constants (fT and fO) of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

| MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x) | υ1 (cm–1) | υ2 (cm–1) | fT × 105(dyne/cm2) | fO × 105(dyne/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 557.32 | 439.52 | 2.2614 | 1.4075 |

| 0.25 | 556.36 | 433.90 | 2.2536 | 1.3707 |

| 0.50 | 554.43 | 427.15 | 2.2380 | 1.3284 |

| 0.75 | 555.39 | 426.19 | 2.2458 | 1.3224 |

| 1.00 | 553.47 | 425.27 | 2.2303 | 1.3167 |

As can be seen, the characteristic band of M2+–O has decreased from a value of 557.37–553.47 cm–1 at tetrahedral sites and 439.52–425.27 cm–1 at octahedral sites with increasing Mn2+ concentration. The bands around 1617 and 3412 cm–1 are attributed to the bending vibrational modes of the adsorbed water molecules.39

The Fe3+–O2– stretching vibrations change when Fe2+ ions at both sites in the ferrite lattice are substituted by Mn2+ ions with a large ionic radius and atomic weight. The FTIR provides information regarding the variation in the molecular structure of ferrite resulting from the addition of Mn2+ ions to Fe3+–O2–.18 The band shift of υ1 and υ2 to a lower frequency reveals variation in fT and fO for the A and B-sites because the vibration frequency (υ) is proportional to the force constant “f” as

| 24 |

where “m” is the reduced mass for the Fe3+ ions and the O2– ions (2.065 × 10–23 g/mol) and C is the speed of light.

By using far-infrared absorption, the cation distribution can be studied since cations in the system at both A- and B-sites are sensitive to changes in the system. In crystalline solids, it is also possible to determine local symmetry surface defects, oxidation, and phenomenon associated with the spinel structure, as well as the presence or absence of Fe2+ ions.23

Magnetic Properties

A magnetic field of 15 kOe was applied to the as-prepared samples, giving rise to magnetic hysteresis loops at room temperature (Figure 6). In Table 7, the magnetic properties of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs are presented. The net magnetization (Ms) values were found to be 37.63, 53.42, 49.45, 41.06, and 44.65 emu/g for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0), respectively. Compared to the smaller iron oxide particles that resulted in a higher saturation magnetization, the observed results of the magnetization experiments for MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) are slightly distorted. It could be assigned to the smaller NPs formed during the synthesis and its anisotropic structural composition.22 The variation in magnetic properties can also be understood as the distribution of cations among a tetrahedral and octahedral site of spinel ferrite.

Figure 6.

Magnetization (M) vs field (H) curves of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

Table 7. Magnetization (Ms), Remanence (Mr) and Remanence Ratio (Mr/Ms), and Magnetic Moment (nB) of the MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs.

| sample X | Ms(emu/g) | Mr(emu/g) | Hc (Oe) | Mr/Ms | nB experimental. | nB calculated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 37.63 | 0.09 | 4.32 | 0.0023 | 1.5599 | 4.1 |

| 0.25 | 53.42 | 0.44 | 8.92 | 0.0082 | 2.2121 | 4.25 |

| 0.50 | 49.45 | 0.15 | 3.12 | 0.003 | 2.0450 | 4.50 |

| 0.75 | 41.06 | 0.39 | 8.37 | 0.0094 | 1.6968 | 4.75 |

| 1.0 | 44.65 | 0.65 | 12.11 | 0.0145 | 1.8465 | 5.0 |

For the series MnxFe1–xFe2O4, the difference of magnetic moment (nB) with different x is calculated. The magnetic moment (nB) per unit was derived using the following formula and shown in Table 7.

| 25 |

Here, M represents the molecular weight. The magnetic moment values reveal that all of the samples are ferrimagnetic. The magnetic moment of individual ions is calculated using the cation distribution. The cation distribution among A-sites and B-sites affects magnetization. Due to the anti-ferromagnetic coupling between the two sides, a net magnetic moment at zero Kelvin is simply the change in the sublattice magnetizations. The calculation is based on Neel’s two-sublattice model of ferrimagnetism, and the magnetic moment is expressed as the magnetic moment per formula unit in B

| 26 |

MB and MA are the magnetic moments of the B- and A-sites, respectively. MnxFe1–xFe2O4 has a cation distribution where the A-site has a -lower Mn2+ ion concentration than the B-site, a mixed spinel structure. Magnetization can be enhanced by the combination of magnetic Mn2+ into the B sublattices instead of magnetic Fe2+ in the spinel. In the B-site, the magnetic moment is greater than that of the A-site when Mn2+ is incorporated. Furthermore, the occupied A-site by the Mn2+ ion allows Fe3+ ions to transfer from the A-site to the B-site, which in turn increases the total magnetic moment. The findings show that as the Mn2+ concentration x increases, both the observed and computed values of magneton number increase. When the content of Mn2+ is increased to oppose the growth of Ms, coercivity “Hc” increases. This is consistent with the relations Hc ∝ K(μ0Ms)−1, where μ0 is the permeability of free space and K is the anisotropy constant.40 However, iron oxide NPs are frequently reported to have low magnetization than the bulk phase due to the canting of the spins at the surface and or in the core, which is brought on by decreased coordination and broken super-exchange bonds.41 The Mn2+-substituted iron oxide crystals have a small variation in the saturation magnetization of nanocrystals. However, it was shown that the saturation magnetization had significantly improved with further Mn2+ substitution. We also observe that the variation in Mn2+ concentration affects the hysteresis curve’s form. When compared to the somewhat bigger iron oxide particles leading to less saturation magnetization, the observed results of the magnetization studies for the varied x values were slightly altered. It is possible that this is caused by the particles’ reduced size and structural anisotropy.42 High manganese doping levels may cause lattice distortion in manganese ferrite NPs, which may result in poor saturation magnetization, according to analysis of XRD patterns and lattice distances.43

Induction Heating Study

The effect of Mn2+-substituted MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) for hyperthermia application is explored by correlating their magnetostructural properties to induction heating. Induction heating studies of manganese-substituted iron oxide NPs had not been reported in correlation with the distribution of cations, which significantly affect its magnetic properties. The heating power of the MNPs is measured in SAR, which is an important parameter in magnetic fluid hyperthermia since it quantifies the degree to which the fluid is capable of converting magnetic energy into heat.44,45 The growth in temperature versus time for samples at different field amplitudes is shown in Figure S2 (Supporting Information). MNPs dissipate heat in AC magnetic fields in the form of SAR (W/g) and ILP (intrinsic loss power), which are calculated by

| 27 |

| 28 |

where Mm is the magnetic material in suspension, Ms is the mass of suspension, dT/dt is the initial slope of the temperature versus time graph, C is the specific heat capacity of suspension = 4.186 J/(g·°C), H is the applied field, and f is the frequency. To reduce the amount of magnetic material needed to treat hyperthermia, the SAR value should be as high as possible because it inversely relates to Mm. In total power loss by MNPs in an AC magnetic field, three components are involved: hysteresis loss, eddy current loss, and residual loss.43

In an AC magnetic field, the hysteresis loss can be represented as

| 29 |

Thus, the SAR is calculated as

| 30 |

As a result, one must consider how frequency and amplitude affect SAR. It has also been shown that a human-tolerated range of frequency and amplitude is believed to occur with their product f × H = C not exceeding ∼5 × 109 A/m·s.46 The calculated values of C are 3.5 × 109, 5.34 × 109, and 7.12 × 109 A/m·s for 13.3, 20, and 26.7 kA/m, respectively. Therefore, in this instance, the essential condition of magnetic field amplitude and frequency is satisfied. Because magnetic field strength and frequency are tightly correlated, SAR values cannot be compared to those of other systems. Thus, discussing heat dissipation in terms of ILP is more appropriate.47 Giri et al. synthesized Fe1–xMnxFe2O4 NPs by the co-precipitation method with a mean size of 10–12 nm, and calorimetric measurements were used to determine the heating efficiency in a field with f = 300 kHz and H = 10–45 kA/m. The Ms and SAR of the material had the maximum values for x = 0.4 as 85 emu/g and 30 W/g, respectively.48 Otero-Lorenzo et al. synthesized manganese-doped iron oxide NPs with Ms values of 66 emu/g and SAR values of 73 W/g of Fe + Mn at f = 183 kHz and H = 17 kA/m.49

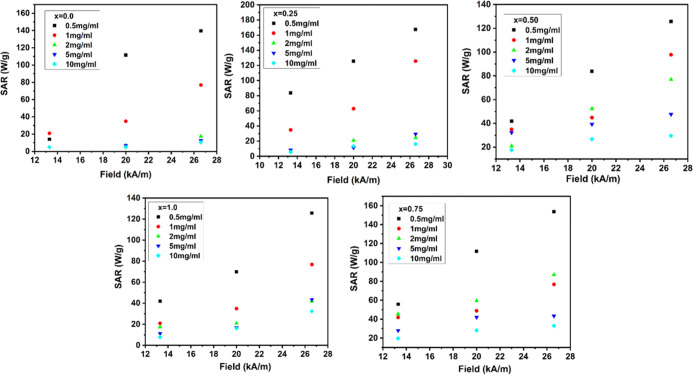

Manganese iron oxide exhibits low conductivity (∼10–3 S/cm), which ensures the absence of significant losses from eddy currents and hysteresis when subjected to an external magnetic field.50 Therefore, a maximum heat loss in the case of manganese iron oxide may be due to Neel rotation and Brownian losses. The size distribution of magnetic NPs has a significant impact on heat dissipation in an AC magnetic field. The temperature rises with increasing field amplitude and NP concentration (shown in Supporting Information Figure S2). Usually, for hyperthermia therapy, the 42–44 °C temperature is considered as effective.51 At concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/mL in water, these NPs self-heated at temperatures rising to 50.25 and 73.32 °C at different magnetic field amplitudes. The actual increase in temperature within 10 min for all samples is measured at a fixed frequency (277 kHz) and different NP concentration (0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL) at changing magnetic field, 13.3, 20.0, and 26.7 kA/m (Figure S2, Supporting Information) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

SAR value of the (x = 0–1) NPs at different concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL) and applied fields, with constant frequency (277 kHz).

Dipole–dipole interactions are affected by broad particle size distributions, affecting the induction heating properties of the material. Consequently, there is an increased hysteresis loss and greater AC magnetically induced heating characteristic. Lasheras et al. studied size dependence magnetic hyperthermia of manganese-doped ferrite NPs; it is observed that the SAR is 50–90 W/g and the ILP values are within 1–2 nHm2/kg.26 Otero-Lorenzo et al. synthesized Mn0.3Fe2.7O4 NPS with a solvothermal technique and found the SAR of 37 W/g, while the calculated ILP for the 5 nm particles is 4 nHm2/kg.49 SAR and ILP values of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs are calculated from eq 27 and eq 28; shown in Table S4 (Supporting Information) with an increase in -field amplitude from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m for 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/mL, respectively. The SAR value for Fe3O4 rises from 4.9 to 17.47 W/g (ILP = 0.09–0.15 nHm2/kg) with an increase in field amplitude from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m for 2 mg/mL, respectively. For sample x = 0.25, the value of SAR increases from 5.63 to 29.44 W/g (ILP = 0.41–0.59 nHm2/kg) with an increase in the field from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m. The sample x = 0.50 the value of SAR increases from 17.61 to 76.89 W/g (ILP = 0.26–1.68 nHm2/kg) with an increase in the field from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m. The SAR value increases from 19.73 to 87.12 W/g (ILP = 0.67–3.65 nHm2/kg) for sample x = 0.75 with a field increase from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m. The SAR increases from 7.75 to 41.94 W/g (ILP = 0.29–1.40 nHm2/kg) for sample MnFe2O4, with a field increase from 13.3 to 26.7 kA/m. The MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs exhibited the highest SAR of about 153.76 W/g for the sample x = 0.75 at a physiological safe range of frequency and amplitude. The magnetic field frequency and magnitude determine the ILP parameter, its ILP is from 2 to 4 nHm2/kg, the most suitable model, since it can be easily compared across experiments.52 When manganese was introduced into the network, local heating increased significantly, from 0.15 nHm2/kg (Fe3O4) to 1.40 nHm2/kg (MnFe2O4). The addition of Mn2+, on the other hand, increases the material’s heat which in turn resulted due to improved magnetic properties due to the distribution of cations among A- and B-sites. In the context of a biological application, hyperthermia could damage cancerous cells and protect healthy cells at the same time, while keeping the temperature rise under control as the AMF exposure period increases. In the end, the results clearly show that high values of SAR are not a result of increasing particle concentration. Comparing these values to those reported in the literature, to reach hyperthermia, we used a low concentration and low field.28

Conclusions

A simple chemical co-precipitation approach is used to make a series of single-phased MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs with high crystallinity with diameters ranging from 5.78 to 9.94 nm. With Mn2+ substitution, the structural analysis revealed cubic spinel NPs, a higher lattice constant, and increased particle sizes. The influence of Mn2+ substitution on the structural and magnetic characteristics of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs is investigated, and it is found that Mn2+, Fe3+ prefers at the tetrahedral sites and Fe2+ the Fe3+ octahedral sites. In addition to saturation magnetization and remnant magnetization, the coercivity of iron oxides and manganese oxides is altered significantly by manganese incorporation due to the interaction of A- and B-site ions, which directly affect the magnetic properties. The altered magnetic properties of MnxFe1–xFe2O4 (x = 0–1) NPs due to the distribution of cations at tetrahedral and octahedral site ultimately affects the self-heating temperature rise characteristics of MNPs. At a physiologically safe range of frequency and amplitude, the sample Mn0.75Fe0.25Fe2O4 had a maximum SAR of 153.76 W/g and ILP 1.38 nHm2/kg making them a suitable candidate for hyperthermia treatment.

Acknowledgments

Author V.M.K. thankful to the D. Y. Patil Education Society (Institution Deemed to be University), Kolhapur, for financial support through the research project (sanction no. DYPES/DU/R&D/2021/276). Author N.D.T. acknowledges funding under SFI-IRC pathway programme (21/PATH-S/9634). Authors S.S.P. and K.V.K. gratefully thank for to Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj Research Training and Human Development Institute (SARTHI), Government of Maharashtra, India, for awarding the Junior Research Fellowship (JRF).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c05651.

Additional details of XRD, EDX, and details of the induction heating, that is, slope values calculated from the temperature vs time plot, and SAR values of the different concentrations of NPs at AMF of field strength (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Doaga A.; Cojocariu A. M.; Amin W.; Heib F.; Bender P.; Hempelmann R.; Caltun O. F. Synthesis and Characterizations of Manganese Ferrites for Hyperthermia Applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 143, 305–310. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2013.08.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat N. D.; Townely H.; Brennan G.; Parchur A. K.; Silien C.; Bauer J.; Tofail S. A. M. Progress in Remotely Triggered Hybrid Nanostructures for Next-Generation Brain Cancer Theranostics. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 2669–2687. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b01173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabai Yazdi S.; Iranmanesh P.; Saeednia S.; Mehran M. Structural, Optical and Magnetic Properties of MnxFe3–xO4 Nanoferrites Synthesized by a Simple Capping Agent-Free Coprecipitation Route. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2019, 245, 55–62. 10.1016/j.mseb.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagiri P.; Sahu B. N.; Venkataramani N.; Prasad S.; Krishnan R. Effect of Substrate Temperature on Magnetic Properties of MnFe2O4 Thin Films. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 056112. 10.1063/1.5007792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khot V. M.; Salunkhe A. B.; Phadatare M. R.; Pawar S. H. Formation, Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of Nanocrystalline MgFe2O4. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 782–787. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Soriano D.; Amaro R.; Lafuente-Gómez N.; Milán-Rois P.; Somoza Á.; Navío C.; Herranz F.; Gutiérrez L.; Salas G. The Influence of Cation Incorporation and Leaching in the Properties of Mn-Doped Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 578, 510–521. 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf K. A. M.; Al-Rawas A. D.; Widatallah H. M.; Al-Rashdi K. S.; Sellai A.; Gismelseed A. M.; Hashim M.; Jameel S. K.; Al-Ruqeishi M. S.; Al-Riyami K. O.; Shongwe M.; Al-Rajhi A. H. Influence of Zn2+ Ions on the Structural and Electrical Properties of Mg1-xZnxFeCrO4 Spinels. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 657, 733–747. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.10.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carta D.; Casula M. F.; Falqui A.; Loche D.; Mountjoy G.; Sangregorio C.; Corrias A. A Structural and Magnetic Investigation of the Inversion Degree in Ferrite Nanocrystals MFe2O4 (M = Mn, Co, Ni). J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 8606–8615. 10.1021/jp901077c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikam D. S.; Jadhav S. V.; Khot V. M.; Bohara R. A.; Hong C. K.; Mali S. S.; Pawar S. H. Cation Distribution, Structural, Morphological and Magnetic Properties of Co1xZnxFe2O4 (x = 0-1) Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 2338–2345. 10.1039/c4ra08342c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahane G. S.; Zipare K. V.; Bandgar S. S.; Mathe V. L. Cation Distribution and Magnetic Properties of Zn2+ Substituted MnFe2O4 Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 4146–4153. 10.1007/s10854-016-6034-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torkian S.; Ghasemi A.; Shoja Razavi R. Cation Distribution and Magnetic Analysis of Wideband Microwave Absorptive CoxNi1–xFe2O4 Ferrites. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 6987–6995. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.02.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakidis K.; Katsikini M.; Vourlias G.; Angelakeris M.; Paloura E. C.; Dendrinou-Samara C. Composition and Hydrophilicity Control of Mn-Doped Ferrite (MnxFe3-xO4) Nanoparticles Induced by Polyol Differentiation. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 5396–5406. 10.1039/c5dt00212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ereath Beeran A.; Nazeer S. S.; Fernandez F. B.; Muvvala K. S.; Wunderlich W.; Anil S.; Vellappally S.; Ramachandra Rao M. S.; John A.; Jayasree R. S.; Harikrishna Varma P. R. An Aqueous Method for the Controlled Manganese (Mn2+) Substitution in Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Contrast Enhancement in MRI. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4609–4619. 10.1039/c4cp05122j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf M. A.; Baig M. M.; Al-Khalli N. F.; Khan M. A.; Aly Aboud M. F.; Shakir I.; Warsi M. F. The Impact of Yttrium Cations (Y3+) on Structural, Spectral and Dielectric Properties of Spinel Manganese Ferrite Nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 10936–10942. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.02.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jesudoss S. K.; Vijaya J. J.; Kennedy L. J.; Rajan P. I.; Al-Lohedan H. A.; Ramalingam R. J.; Kaviyarasu K.; Bououdina M. Studies on the Efficient Dual Performance of Mn1–xNixFe2O4 Spinel Nanoparticles in Photodegradation and Antibacterial Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2016, 165, 121–132. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satalkar M.; Kane S. N.; Ghosh A.; Ghodke N.; Barrera G.; Celegato F.; Coisson M.; Tiberto P.; Vinai F. Synthesis and Soft Magnetic Properties of Zn0.8-xNixMg0.1Cu0.1Fe2O4 (x = 0.0-0.8) Ferrites Prepared by Sol-Gel Auto-Combustion Method. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 615, S313–S316. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.01.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torkian S.; Ghasemi A.; Shoja Razavi R. Cation Distribution and Magnetic Analysis of Wideband Microwave Absorptive CoxNi1–xFe2O4 Ferrites. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 6987–6995. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.02.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khot V. M.; Salunkhe A. B.; Phadatare M. R.; Thorat N. D.; Pawar S. H. Low-Temperature Synthesis of MnxMg1-xFe2O4(x = 0-1) Nanoparticles: Cation Distribution, Structural and Magnetic Properties. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 055303. 10.1088/0022-3727/46/5/055303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malaescu I.; Lungu A.; Marin C. N.; Vlazan P.; Sfirloaga P.; Turi G. M. Experimental Investigations of the Structural Transformations Induced by the Heat Treatment in Manganese Ferrite Synthesized by Ultrasonic Assisted Co-Precipitation Method. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 16744–16748. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.07.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenart V. M.; de Fátima Turchiello R.; Calatayud M. P.; Goya G. F.; Gómez S. L. Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles of Different Size and Shape by Interplay of Two Different Surfactants. Braz. J. Phys. 2019, 49, 829–835. 10.1007/s13538-019-00714-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salokhe A.; Koli A.; Jadhav V.; Mane-Gavade S.; Supale A.; Dhabbe R.; Yu X. Y.; Sabale S. Magneto-structural and induction heating properties of MFe2O4 (M= Co, Mn, Zn) MNPs for magnetic particle hyperthermia application. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 2017. 10.1007/s42452-020-03865-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beeran A. E.; Nazeer S. S.; Fernandez F. B.; Muvvala K. S.; Wunderlich W.; Anil S.; Vellappally S.; Ramachandra Rao M. R.; John A.; Jayasree R. S.; Varma P. H. An aqueous method for the controlled manganese (Mn2+ ) substitution in superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for contrastenhancement in MRI. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 4609–4619. 10.1039/c4cp05122j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugumaran P. J.; Liu X. L.; Herng T. S.; Peng E.; Ding J. GO-Functionalized Large Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with Enhanced Colloidal Stability and Hyperthermia Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 22703–22713. 10.1021/acsami.9b04261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour S. F.; Elkestawy M. A. A Comparative Study of Electric Properties of Nano-Structured and Bulk Mn-Mg Spinel Ferrite. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 1175–1180. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2010.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodake U. R.; Kambale R. C.; Suryavanshi S. S. Effect of Mn2+ Substitution on Structural, Electrical Transport and Dielectric Properties of Mg-Zn Ferrites. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 1129–1134. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasheras X.; Insausti M.; de la Fuente J. M.; Gil de Muro I.; Castellanos-Rubio I.; Marcano L.; Fernández-Gubieda M. L.; Serrano A.; Martín-Rodríguez R.; Garaio E.; García J. A.; Lezama L. Mn-Doping Level Dependence on the Magnetic Response of MnxFe3-xO4 Ferrite Nanoparticles. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 11480–11491. 10.1039/c9dt01620a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia E. F.; Zaki A. H.; El-Dek S. I.; Farghali A. A. Synthesis, Physicochemical Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Nanosized Mg Doped Mn Ferrite. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 231, 589–596. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.01.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikam D. S.; Jadhav S. V.; Khot V. M.; Phadatare M. R.; Pawar S. H. Study of AC Magnetic Heating Characteristics of Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia Therapy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 349, 208–213. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2013.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat N. D.; Bohara R. A.; Yadav H. M.; Tofail S. A. M. Multi-Modal MR Imaging and Magnetic Hyperthermia Study of Gd Doped Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Integrative Cancer Therapy. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 94967–94975. 10.1039/c6ra20135k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salunkhe A. B.; Khot V. M.; Phadatare M. R.; Thorat N. D.; Joshi R. S.; Yadav H. M.; Pawar S. H. Low Temperature Combustion Synthesis and Magnetostructural Properties of Co-Mn Nanoferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 352, 91–98. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2013.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heiba Z. K.; Mohamed M. B.; Hamdeh H. H.; Ahmed M. A. Structural Analysis and Cations Distribution of Nanocrystalline Ni1-xZnxFe1.7Ga0.3O4. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 618, 755–760. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.08.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi F.; da Silva S. W.; Garg V. K.; Oliveira A. C.; Morais P. C.; Franco A. Influence of the Mg-Content on the Cation Distribution in Cubic MgxFe3-xO4 Nanoparticles. J. Solid State Chem. 2009, 182, 2423–2429. 10.1016/j.jssc.2009.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesha Angadi V.; Rudraswamy B.; Sadhana K.; Murthy S. R.; Praveena K. Effect of Sm3+-Gd3+ on Structural, Electrical and Magnetic Properties of Mn-Zn Ferrites Synthesized via Combustion Route. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 656, 5–12. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.09.222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awati V. V.; Rathod S. M.; Mane M. L.; Mohite K. C. Influence of Zn2+ Doping on the Structural and Surface Morphological Properties of Nanocrystalline Ni-Cu Spinel Ferrite. Int. Nano Lett. 2013, 3, 29. 10.1186/2228-5326-3-29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath S.; Das A.; Das R. Effect of Cobalt Doping on Structural Parameters, Cation Distribution and Magnetic Properties of Nickel Ferrite Nanocrystals. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 16467–16482. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.02.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vara Prasad B. B. V. S.; Ramesh K. V.; Srinivas A. Structural and Magnetic Studies on Co-Zn Nanoferrite Synthesized via Sol-Gel and Combustion Methods. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2019, 37, 39–54. 10.2478/msp-2019-0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarchuk T.; Bououdina M.; Macyk W.; Shyichuk O.; Paliychuk N.; Yaremiy I.; Al-Najar B.; Pacia M. Structural, Optical, and Magnetic Properties of Zn-Doped CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 141. 10.1186/s11671-017-1899-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G.; Shah J.; Kotnala R. K.; Singh V. P.; Sarveena; Garg G.; Shirsath S. E.; Batoo K. M.; Singh M. Superparamagnetic Behaviour and Evidence of Weakening in Super-Exchange Interactions with the Substitution of Gd3+ Ions in the Mg-Mn Nanoferrite Matrix. Mater. Res. Bull. 2015, 63, 216–225. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M.; Asghar M.; Junaid M.; Warsi M. F.; Naveed Rasheed M.; Hashim M.; Al-Maghrabi M. A.; Khan M. A. Structural and Magnetic Properties Variation of Manganese Ferrites via Co-Ni Substitution. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 474, 98–103. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.10.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dojcinovic M. P.; Vasiljevic Z. Z.; Pavlovic V. P.; Barisic D.; Pajic D.; Tadic N. B.; Nikolic M. V. Mixed Mg–Co Spinel Ferrites: Structure, Morphology, Magnetic and Photocatalytic Properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 855, 157429. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bianco L.; Spizzo F.; Barucca G.; Ruggiero M. R.; Geninatti Crich S.; Forzan M.; Sieni E.; Sgarbossa P. Mechanism of Magnetic Heating in Mn-Doped Magnetite Nanoparticles and the Role of Intertwined Structural and Magnetic Properties. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 10896–10910. 10.1039/c9nr03131f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. H.; Lee N.; Kim H.; An K.; Park Y. I.; Choi Y.; Shin K.; Lee Y.; Kwon S. G.; Na H. B.; Park J. G. Large-scale synthesis of uniform and extremely small-sized iron oxide nanoparticles for high-resolution T 1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12624–12631. 10.1021/ja203340u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Ma L.; Xin J.; Li A.; Sun C.; Wei R.; Ren B. W.; Chen Z.; Lin H.; Gao J. Composition Tunable Manganese Ferrite Nanoparticles for Optimized T2 Contrast Ability. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 3038–3047. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat N. D.; Bohara R. A.; Tofail S. A. M.; Alothman Z. A.; Shiddiky M. J. A.; A Hossain M. S.; Yamauchi Y.; Wu K. C. W. Superparamagnetic Gadolinium Ferrite Nanoparticles with Controllable Curie Temperature—Cancer Theranostics for MR-Imaging-Guided Magneto-Chemotherapy. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4586–4597. 10.1002/ejic.201600706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat N. D.; Otari S. V.; Patil R. M.; Khot V. M.; Prasad A. I.; Ningthoujam R. S.; Pawar S. H. Enhanced Colloidal Stability of Polymer Coated La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 Nanoparticles in Physiological Media for Hyperthermia Application. Colloids Surf., B 2013, 111, 264–269. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergt R.; Dutz S. Magnetic Particle Hyperthermia-Biophysical Limitations of a Visionary Tumour Therapy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 311, 187–192. 10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.10.1156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verde E. L.; Landi G. T.; Gomes J. A.; Sousa M. H.; Bakuzis A. F. Magnetic Hyperthermia Investigation of Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles: Comparison between Experiment, Linear Response Theory, and Dynamic Hysteresis Simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 123902. 10.1063/1.4729271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giri J.; Pradhan P.; Sriharsha T.; Bahadur D. Preparation and Investigation of Potentiality of Different Soft Ferrites for Hyperthermia Applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 10Q916. 10.1063/1.1855131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Lorenzo R.; Fantechi E.; Sangregorio C.; Salgueiriño V. Solvothermally Driven Mn Doping and Clustering of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Heat Delivery Applications. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 6666–6675. 10.1002/chem.201505049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotjanasuworapong K.; Lerdwijitjarud W.; Sirivat A. Synthesis and Characterization of Fe0.8Mn0.2Fe2O4 Ferrite Nanoparticle with High Saturation Magnetization via the Surfactant Assisted Co-Precipitation. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 876. 10.3390/nano11040876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khot V. M.; Salunkhe A. B.; Thorat N. D.; Ningthoujam R. S.; Pawar S. H. Induction Heating Studies of Dextran Coated MgFe2O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 1249–1258. 10.1039/c2dt31114c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaleiro D.; Pastoriza-Gallego M. J.; Gracia-Fernández C.; Piñeiro M. M.; Lugo L. Rheological and Volumetric Properties of TiO2- Ethylene Glycol Nanofluids. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 286. 10.1186/1556-276X-8-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.