Abstract

Sucrose transporters of the SUT4 clade show dual targeting to both the plasma membrane as well as to the vacuole. Previous investigations revealed a role for the potato sucrose transporter StSUT4 in flowering, tuberization, shade avoidance response, and ethylene production. Down-regulation of StSUT4 expression leads to early flowering, tuberization under long days, far-red light insensitivity, and reduced diurnal ethylene production. Sucrose export from leaves was increased and a phase-shift of soluble sugar accumulation in source leaves was observed, arguing for StSUT4 to be involved in the entrainment of the circadian clock. Here, we show that StSUT4, whose transcripts are highly unstable and tightly controlled at the post-transcriptional level, connects components of the ethylene and calcium signalling pathway. Elucidation of the StSUT4 interactome using the split ubiquitin system helped to prove direct physical interaction between the sucrose transporter and the ethylene receptor ETR2, as well as with the calcium binding potato calmodulin-1 (PCM1) protein, and a calcium-load activated calcium channel. The impact of calcium ions on transport activity and dual targeting of the transporter was investigated in detail. For this purpose, a reliable esculin-based transport assay was established for SUT4-like transporters. Site-directed mutagenesis helped to identify a diacidic motif within the seventh transmembrane spanning domain that is essential for sucrose transport activity and targeting, but not required for calcium-dependent inhibition. A link between sucrose, calcium and ethylene signalling has been previously postulated with respect to pollen tube growth, shade avoidance response, or entrainment of the circadian clock. Here, we provide experimental evidence for the direct interconnection of these signalling pathways at the molecular level by direct physical interaction of the main players.

Keywords: Calcium binding, calcium channel, calcium inhibition, dual targeting, ethylene perception, protein-protein interaction, sub-cellular dynamics, sucrose transport

An esculin-based transport assay and a systematic screen for protein-protein interactions of StSUT4 revealed that sucrose, ethylene, and calcium signalling are closely linked.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

The sucrose transporter StSUT4 from potato is a well-characterized transporter protein whose main function is the inhibition of flower and tuber induction in a sucrose-dependent manner (Chincinska et al., 2008). It has also been shown that StSUT4 is also involved in far-red light perception and the shade avoidance response (Chincinska et al., 2008). It is regulated by the circadian clock, and StSUT4-RNAi plants show increased levels of the phloem-mobile miRNA172 (Garg et al., 2021), and display exactly the same phenotype regarding internode elongation and tuber induction, as described for transgenic potato plants overexpressing miR172 under control of the constitutive CaMV35S promoter (Martin et al., 2009). StSUT4 transcript abundance is generally very low (Weise et al., 2000), and transcript stability is regulated at the post-transcriptional level (He et al., 2008; Liesche et al., 2011).

Interestingly, StSUT4-silenced potato plants also show reduced ethylene production, which in wild-type potato plants takes place at a very low level, and follows a diurnal rhythm (Chincinska et al., 2013).

In StSUT4-silenced potato plants, not only is the diurnal oscillation of ethylene production disturbed, but also the accumulation of soluble sugars in source leaves is somehow delayed, with maximum levels shifted to the dark period of the day (Chincinska et al., 2008). Also, the maximal sucrose export from the leaves into the phloem is delayed and shifted towards the end of the day under long days, with higher amplitude (Chincinska et al., 2008).

Here, we investigate the regulation of StSUT4 at the post-transcriptional level by mRNA quantification, and at the post-translational level by screening for protein-protein interaction partners, analysis of mutated constructs generated by site directed mutagenesis, and by sub-cellular localization.

Interestingly, we identified a functional member of the family of ethylene receptor proteins, StETR2, which, according to co-expression databases, is tightly co-regulated with StSUT4 (Supplementary Fig. S1), to physically interact with StSUT4 in the split ubiquitin system. Furthermore, the potato calmodulin-1 protein StPCM1 (Poovaiah et al., 1996) was shown to be one of the StSUT4-interacting proteins. Both interactions could be confirmed by alternative methods such as bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC). A third interacting protein has homologies to calcium-load activated calcium channels. The impact of calcium ions on activity of the sucrose transporter StSUT4 was therefore investigated in detail. For these purposes, it was indispensable to establish a reliable transport activity assay for this low affinity transporter that transports sucrose only at very low rate.

An esculin-based transport assay was successfully established for the type III sucrose transporter of the SUT4 clade, that helped to determine transport kinetics in detail. Our investigations suggest a completely different regulatory mechanism and pH dependence for the StSUT4 transporter, compared with other well described type I sucrose transporters such as StSUT1, which was (also) shown to be efficiently inhibited by divalent cations such as calcium or magnesium (Krügel et al., 2013). Interestingly, rising calcium concentrations not only affect StSUT4 activity, but also its sub-cellular localization.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Potato (Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum var. Desiree) and tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) plants were grown in the greenhouse with a cycle of 16 h light (22 °C) and 8 h darkness (15 °C). Additional illumination was provided by high-pressure sodium lamps SON-T Green Power and metal halide lamps MASTER LPI-T Plus (Philips Belgium, Brussels). Both lamps were distributed equally in the greenhouse. The mean photosynthetic photon flux density was about 150 µmol m-2 s-1. Transgenic plants of StSU4 (RNAi and overexpressors) used in this study were previously generated in our laboratory (Chincinska et al., 2008).

Bacterial and yeast strains

Saccharomyces cerevisiae L40ccU A [Mat a, His3Δ200, trp1-901, leu2-3,112, lys2: (lexAop)4–HIS3, ura3::(lexAop)8–lacZ, ADE::(lexAop)8–URA, GAL4, gal80, can1, cyh2; Goehler et al., 2004] was used for the split ubiquitin system. Bacterial strains Escherichia coli DB3.1 (F-, gyrA462, endA1, Δ(sr1–recA) mcrB, mrr, hsdS20(rB–mB-), supE44, ara14, galK2, lacY1, proA2, rpsL20 (Smr), xyl5, Δleu, mtl1) and Escherichia coli NovaXG Zappers (F–, mcrA, Δ(mcrC–mrr), endA1, recA1, φ80lacZΔM15, ΔlacX74, araD139, Δ(ara–leu)7697, galU, galK, rpsL, nupG, λ– tonA (Novagen, Darmstadt)) were used for GATEWAY cloning.

Transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves was performed by infiltration with Agrobacterium tumefaciens pGV2260 or Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 (Hellens et al., 2000).

Cloning of the bait construct

The StSUT4 bait construct was amplified via a two-step PCR reaction and cloned into pENTRY and the Cub vectors using the GATEWAY technology (Invitrogen, USA). Primers used for the generation of the bait construct are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Construction of a cDNA library from Solanum tuberosum

A potato cDNA library was generated from all above and below-ground plant tissues and cloned into the pENTRY1A vector as described (Krügel et al., 2012). The complexity of the cDNA library was 6.3 × 105 and the average insert size was 1.3 kb. All sequenced clones were in the sense orientation. The cDNA library was shuttled into pNXgate32 3HA with inserted ccdB gene. Transformation of highly competent E. coli (NovaXG Zappers, Novagen, Germany) occurred by electroporation. Cells were plated on 20 Petri dishes (20 cm diameter) and plasmid isolation was performed with Plasmid Mega Kit (Qiagen, Germany).

GATEWAY compatible SUS vectors

pNXgate and pXNgate are multiple-copy plasmids containing TRP1 for selection in yeast, suitable for NubG-X and X-NubG fusions, respectively, of prey polypeptides X. pMetYCgate is a low-copy plasmid with the selection marker LEU2, comprising the Met-repressible MET25 promoter, B1-KanMX-B2 cassette, and CubPLV. pMetYCgate is suited for Y-CubPLV fusions of bait peptides Y. The MET25 promoter can be used to modulate bait levels.

Bait constructs were cloned into the low-copy vector CubPLV Met25YCgate (Obrdlik et al., 2004). In order to facilitate efficient cloning via in vivo recombination, the ccdB gene was amplified from pDONR221 (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and ligated via PstI and a blunted HindIII site within the GATEWAY cassette of CubPLV met25 pXCgate. Insertion of the 665 bp ccdB gene allows selection in E. coli DH5α after successful recombination with the StSUT4 bait in pDONR221. Insertion of the ccdB gene was confirmed by sequencing.

The cDNA library was cloned in the multi-copy prey plasmid pNXgate32 3HA (Obrdlik et al., 2004). Before shuttling of the cDNA library, the ccdB gene was inserted into the prey vector to increase recombination efficiency, as described previously (Krügel et al., 2012). The kanamycin resistance gene was still functional after insertion of the 737 bp toxin gene. Insertion was tested by restriction analysis and sequencing.

Split ubiquitin screen

Large-scale yeast transformation was performed as described (Gietz and Woods, 2002). Yeast cells were transformed first with the bait construct.

The compound 3-Aminotriazol (3-AT) is a competitive inhibitor of the histidine biosynthesis HIS3 gene product and, for each of the baits, the specific 3-AT concentration in the selection medium had to be determined to exclude autoactivation of the HIS3 gene (Joung et al., 2000). Titration of the 3-AT concentration was performed by co-expression of the bait construct with the empty pNubGgate. The 3-AT concentration required to prevent autoactivation was determined to be 40 mM for StSUT4.

Large-scale yeast transformation was performed according to the above-mentioned protocol; cells were resuspended in 10 ml distilled water and 500 μl cell suspension was plated on selection medium, without trp, leu, his, and 40 mM 3-AT. In order to determine the transformation rate, 4 μl of cells were plated on selection medium without trp and leu (SD-LT), and the number of primary transformants was counted after 3–4 d.

A saturated screen of the cDNA library (with 38 000 genes expected for Solanum tuberosum) was performed with a number of primary transformants of 106 (number of independent yeast colonies carrying both plasmids and growing on medium -trp-leu) as described before (Krügel et al., 2012). Sixty yeast colonies growing on selective medium (–leu –trp –ura –his) were selected for further analysis, and after restriction analysis, 23 restriction groups were identified. Fifteen different inserts were sequenced and 10 candidates showed the correct reading frame.

Cloning of BiFC constructs

All other constructs were cloned using GATEWAY technology into VYNE and VYCE (Gehl et al., 2009) allowing C-terminal fusion to the two halves of the YFP molecule (see primer list in Supplementary Table S1).

Sub-cellular localization of StSUT4 was performed by cloning the coding region into pK7YWG2.0 (Karimi, 2005) by GATEWAY technology using the primers for GATEWAY cloning mentioned above.

Cloning of interaction partners in yeast expression vectors

Full length cDNAs from ETR2 and PCM1 were amplified from SUS vectors generated above using specific primers (Supplementary Table S1), and ligated into the yeast expression vector 112A1NE (Reinders et al., 2002) after digestion with EcoRI and BamHI. Constructs were checked by restriction analysis and sequencing. Co-expression in yeast was performed using different amino acid auxotrophies (112A1NE: trp-selection, pDR196: ura selection).

Infiltration of tobacco leaves

Transient transformation of leaves from N. benthamiana with Agrobacterium suspension transformed with BiFC vectors was carried out as described previously (Krügel et al., 2012). The Agrobacterium cultures with an OD600 ~0.1 were harvested and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM magnesium chloride, 10 mM MES pH 5.7, 100 μΜ acetosyringone).

After 2 h incubation, the suspension was injected into the lower side of the leaves. The leaves were analysed the 3rd and 4th d after infiltration using a Zeiss LSM800 with Airyscan (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The detection settings were chosen according to the fluorophores. Excitation of YFP was at 488 nm, and for chlorophyll, was at 640 nm.

RNA quantification by qPCR

RNA extraction from source leaf tissue was performed with Trisure (Bioline, Luckenwalde, Germany) or peqGold Trifast (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed with the Qiagen Omniscript RT Kit according to the manual. Optimized conditions included using oligo(dT) primers for the initial reverse transcription reaction on approximately 1 µg of total RNA after digestion with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Aliquots of 0.2 µl of the 10 µl RT-reaction were used for the subsequent PCR reaction in the presence of SYBR Green with HotGoldStar DNA-Polymerase (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) in a BioRad CFX Cycler using the CFX System Software (BioRad, Germany) using the following programme: denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s at 61 °C, and elongation for 30 s at 72 °C, in a program of 45 cycles, in a 10 µl reaction volume. Primers were designed to obtain a 50–150 bp amplicon using Primer3 software (https://primer3.ut.ee/)). Ubiquitin was used as a reference gene and relative transcript abundance of the target gene was calculated with respect to reference gene using the delta Ct method (2(-ΔΔCt)). All primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Esculin uptake measurements

A sucrose transporter assay using esculin was performed exactly as described previously (Gora et al., 2012). Yeast cells expressing StSUT1, StSUT4 or mutated versions were harvested by centrifugation at 1300 ×g and esculin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 1, 2, and 8 mM was added to 200 μl of phosphate buffer (25 mM Na2HPO4, pH 3, 5, or higher, as indicated in each figure) to each well. Uptake experiments under acidic pH conditions were performed in the presence of 25 mM citric acid buffer (4.275 g l-1 of sodium citrate dihydrate and 2.011 g l-1 of citric acid, pH 5.0). The incubation time was between 10 and 60 min. Competition experiments were conducted in the presence of 20 mM of sucrose, glucose, or sorbitol. The plates were vortexed for 30 s and incubated at 30 °C for 1 h while shaking. The plates were centrifuged at 1300 × g for 5 min and the supernatant discarded. Cells were washed by adding 200 μl of phosphate buffer to each well. Cells were resuspended by vortexing. The washing step was repeated, and the content of microtiter plates then transferred to a black microtiter plate for fluorescence reading in a spectrofluorometer, with excitation at 367 nm and emission at 454 nm. Relative fluorescence was determined in relation to cell density measurement at OD600 as described previously (Gora et al., 2012).

Results

Members of the SUT4 sub-family show dual targeting to the vacuole and the plasma membrane

As known for many other sucrose transporters of the SUT4 family, the StSUT4 transporter, although functional at the plasma membrane, does not always co-localize with the plasma membrane marker, but rather with vacuolar markers (Fig. 1; Chincinska et al., 2013; Ho et al., 2021). In bimolecular complementation assays (BiFC) showing the capacity of StSUT4 to homodimerize, the sub-cellular localization of the StSUT4 dimer changes evidently compared with its monomeric form (Garg et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Sub-cellular localization of StSUT4. (A) Co-expression of a fluorescent StSUT4-YFP fusion protein (green) with a plasma membrane marker protein, CBL-OFP (orange) reveals no co-localization at the plasma membrane as previously observed under standard conditions (Garg et al. 2020). (B) StSUT4-RFP (red) is partially co-localized with a vacuolar marker protein, PTR2-YFP (green). Photographs were taken 3 d after infiltration with the Airyscan detector. Scale bar represents 10 µm.

The sub-cellular localization of plant sucrose transporters is highly dynamic and affected by various external factors such as pH, temperature, oligomerization, ions, the substrate sucrose, inhibitors such as Brefeldin A (BFA) or cycloheximide (CHX), and biotic interactions such as colonization by mycorrhizal fungi, etc. (Krügel et al., 2008, 2012; Liesche et al., 2008, 2010; Bitterlich et al., 2014; Garg et al., 2020; Hansch et al., 2020). Sub-cellular localization of sucrose transporter might not only be affected by homo-oligomerization, but also by other interaction partners. With the aim to learn more about these post-translational effectors, it was obvious to screen for further interacting proteins.

Identification of StSUT4-interacting candidates using the split ubiquitin system

In a saturated split ubiquitin screen of a potato cDNA library (Krügel et al., 2012) with 106 primary transformants using the full length StSUT4 cDNA as a bait construct, 60 yeast colonies were found to be growing under highly stringent conditions (in the presence of 40 mM 3-AT). Restriction analysis helped to group them into distinct restriction groups, and sequencing identified 11 different cDNA inserts (Table 1). The full length cDNAs were cloned and interaction with StSUT4 was confirmed (Fig. 2A). The majority of the candidates represented integral membrane proteins, whereas four interacting candidates were predicted to encode soluble proteins (Table 1). Some of the candidates have been isolated several times independently. One ER-localized protein disulfide isomerase was identified previously to also interact with other plant sucrose transporters: StSUT1 (Krügel et al., 2012) and SlSUT2 (Bitterlich et al., 2014).

Table 1.

StSUT4-interacting proteins identified by the split ubiquitin system using full length StSUT4 cDNA as a bait.

| Name | Accession number | EST (S. tuberosum) |

Predicted cellular compartment |

Assumed function | TMDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene receptor 2 (ETR2) | AY600436 | 423729 | ER | Ethylene receptor | 3 |

| Carboxylesterase 12 (CXE12) | XM006346397.2 | EST600820 cDNA clone STMCZ57 |

Nucleus Cytosol |

Alpha/beta hydrolase, thioesterase, lipase, interacts with DELLA |

0-1 |

|

calcium-load activated calcium channel

(CLAC channel) |

NP_001275630 | CV496516.1 | ER | Calcium-selective channel required to prevent calcium stores from overfilling; ER calcium homeostasis | 2-3 |

|

Pectate lyase

(PLL8) |

X1599 | EST339302 (S. lycopersicum) |

Cell wall | Pectate lyase | 1 |

| Pectate lyase | BG140571 | EST481013 (S. pennellii) |

Cell wall | Pectate lyase | 1 |

| Photosystem II protein Y (PsbY) | P80470 | PPCAM72 PPCCQ17 |

Chloroplast, nuclear encoded | MYB TF, ethylene response |

4 |

| Limb Development Membrane Protein 1 (LMBR1)-like ATPase | XM550585 XP480815 |

AJ785414 | PM? | Ubiquitin catabolism, thioesterase, cys endopeptidase, zinc ion binding | 2 |

| Potato calmodulin 1 (StPCM1) | J04559 | 47242.1 | cytosol | Calcium binding | none |

| Protein disulfide isomerase StPDI1 | DQ222488 | Clone 098B03 | ER | Chaperone, protein folding, quality control, escort | none |

| Cathepsin D inhibitor | DQ168325 | cDNA clone 134F08 | Cell wall | Kunitz-type proteinase inhibitor, Lysosomal Asp-protease Inhibitor |

none (0-1) |

| Unknown protein | CP055238.1 | cDNA clone cPR018C17 EST560871 |

unknown | Nodulin-like stress-induced protein, zinc finger protein | none |

TMDs: number of predicted transmembrane domains.

EST: expressed sequence tag

Fig. 2.

StSUT4 protein interactions. (A) Confirmation of interaction of full length cDNAs of StETR2 and StPCM1 with the sucrose transporter StSUT4 by the split ubiquitin system; and (B-E) BiFC analysis. (A) Homodimer formation between StSUT4 in Nub and StSUT4 in Cub was taken as positive control. Full length cDNAs of ETR2 and PCP1 enable yeast strain L40ccU to grow on selective medium. Quantification of interaction strength was performed using ß-glucuronidase assay (blue colour). (B) Confirmation of StSUT4-ETR2 interaction in BiFC experiments. Green colour indicates YFP reconstitution and successful interaction. Autofluorescence of chlorophyll is shown in red. A single scan is shown. (C) Same cell as shown in (B) in a maximum projection of a z-stack, showing interaction in intracellular compartments. (D, E) Confirmation of StSUT4 interacting with StPCM1 was performed by BiFC in both orientations. Interaction takes place close to the plasma membrane. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

ESTs are available from Solanum tuberosum according to the NCBI database, for most of the 11 interaction partners. For further investigation the most interesting was the interaction between the sucrose transporter StSUT4 and the ethylene receptor ETR2 belonging to the ETR family of membrane receptors, which is predicted to be localized in the ER membrane (Ju and Chang, 2012). SUT4 and ETR2 from tomato are tightly co-expressed according to various co-expression databases (TomExpress (http://tomexpress.toulouse.inra.fr/) ATTED II (https://atted.jp/); Supplementary Fig. S1). Another relevant interaction partner is the calcium binding protein StPCM1 (Takezawa et al., 1995).

StSUT4 interacts with ETR2 in intracellular compartments

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) was used to confirm the interaction between StSUT4 and the ethylene receptor protein StETR2 identified in the split ubiquitin screen, using the full-length cDNA of StSUT4 as a bait (Fig. 2A). StETR2 is a 753 amino acid transmembrane protein with three transmembrane domains predicted to be integrated in the ER membrane, with the C-terminus orientated towards the cytoplasm and the N-terminus within the ER lumen (http://aramemnon.uni-koeln.de/). The structure of ETR2 is reminiscent to bacterial two-component systems with a N-terminal sensor domain able to bind copper ions and the C-terminal (cytoplasmic) histidine kinase domain (ethylene binding domain, GAF domain, kinase domain, receiver domain). Copper ions are needed for homodimer formation of ethylene receptor proteins to turn the complex into its active form (Ju and Chang, 2012). Further downstream signalling components involve CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE1 (CTR1) Raf-like protein kinase and the transcription factor ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3; Ju and Chang, 2012).

Although ETR2 is predicted to be in the ER (Ju and Chang, 2012) and StSUT4 at the plasma membrane and the tonoplast, a clear interaction between StSUT4 and the StETR2 protein was confirmed by BiFC experiments; fluorescent YFP reconstitution was mainly observed in intracellular vesicles (Fig. 2B, C) and additionally in the cell periphery. All interaction studies were repeated in yeast using full length cDNAs cloned into the Nub and Cub vectors, and co-expressed with the StSUT4 cDNA in the Nub and Cub vector in various combinations (Supplementary Fig. S2).

StSUT4 interacts with PCM1 in the cell periphery

Another interesting StSUT4-interacting protein, StPCM1, identified by the split ubiquitin screen, was also confirmed in BiFC experiments (Fig. 2D, E; Supplementary Fig. S3). Here, a completely different localization of the heteromeric complex was observed: StPCM1 and StSUT4 interacted with each other mainly in the cytosol close to the plasma membrane. Since PCM1 is a calcium-binding protein with four calcium binding motifs, the question arose whether calcium ions were able to somehow affect StSUT4 activity, localization, dimerization, or protein-protein interactions. In order to test these hypotheses, we first needed to establish a functional assay, since StSUT4 transports sucrose with low affinity and at a very low rate. This is the reason why functional characterization of StSUT4 transport kinetics was performed only in yeast but not in Xenopus oocytes (Weise et al., 2000).

Establishment of a functional assay using esculin as sucrose analogue

Esculin is a fluorescent coumarin-derivative that is well established to serve as an equivalent sucrose analogue in uptake experiments with type I plant sucrose transporters, and also for dicotyledonous, but not monocotyledonous type II transporters (Gora et al., 2012). Thus, we had to first test whether or not the fluorescent esculin assay was suitable for SUT4-clade (or type III-like) sucrose transporters as well.

The Michaelis Menten constant (KM) for StSUT1 is close to 1 mM sucrose, and 1 mM of esculin was suitable for StSUT1-mediated sucrose uptake measurements (Fig. 3A). StSUT4, however, did not show sucrose uptake using 1 mM of esculin (Fig. 3A). The affinity of SUT4-clade sucrose transporters towards the substrate sucrose was much lower than for SUT1 (Weise et al., 2000; Weschke et al., 2000). Therefore, we tested increasing substrate concentrations (2 mM, up to 8 mM) and were successful in establishing a functional uptake assay using increased esculin concentrations (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Esculin uptake assay. Establishment of a functional assay for StSUT4 in yeast cells using esculin as fluorescent sucrose analogue and determination of the optimal substrate concentration. (A) StSUT1, but not StSUT4 shows significantly higher esculin uptake at 1 mM substrate concentration than the empty vector control (pDR196). (B) StSUT4 and StSUT1 show significantly higher esculin uptake than the empty vector control (pDR196) at 8 mM substrate concentration after 1 h of incubation. Data are means ±SD; n=3. Student’s t-test was performed (*** P<0.001, **P<0.01 and *P<0.05).

Increasing the esculin concentration to 8 mM revealed a clear StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake that was significantly higher than the empty vector control (P<0.001). Thereby, the low affinity of StSUT4 towards the substrate sucrose or esculin was confirmed. Not only did the substrate affinity differ between SUT1 and SUT4 transporters, but pH dependence was different as well. Esculin uptake was higher at pH 5 than at pH 3 (Fig. 4B) which was also observed in previous investigations using 14C-sucrose uptake experiments (Weise et al. 2000). This is in contrast to StSUT1 with a pH optimum in the highly acidic range (Fig. 4A; Krügel et al., 2008). The extremely strong increase in sucrose uptake at very low pH as previously observed for StSUT1 and ZmSUT1 (Krügel et al. 2008) was not observed for StSUT4, neither in case of 14C-sucrose (Weise et al. 2000), nor for esculin uptake (Fig. 4B). pH-dependent esculin uptake was also confirmed by confocal microscopy using UV excitation (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Following this, all sucrose uptake experiments using StSUT4 were performed at optimal conditions with 8 mM esculin and at pH 5.0.

Fig. 4.

pH dependence of esculin uptake by StSUT1 and StSUT4 in yeast cells. (A) StSUT1 shows a pH optimum in the highly acidic range (pH 3). (B) StSUT4 not only shows a reduced affinity towards its substrate but also a different pH dependence than StSUT1 with a pH optimum at pH 5. Data are means ±SD; n=4 independent measurements. (C) StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake in yeast cells in the presence of unlabelled sugars or no sugar. Competition studies revealed specificity of esculin uptake mediated by StSUT4 that is efficiently down-regulated in the presence of 20 mM sucrose. Data are shown as means ±SD, n=9 with three biological and three technical replicates, Student‘s t-test was performed (***P<0.001).

The specificity of StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake was then tested under pH 5.0 in the presence of 8 mM of esculin and an excess of unlabelled sugars (Fig. 4C). Whereas addition of 20 mM sucrose decreased the StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake by almost 50%, the addition of an excess of 20 mM glucose or sorbitol decreased it by only 10 % (Fig. 4C).

Under these optimal conditions, the presence of StSUT4-interacting proteins was tested when expressed in the same yeast cells (Fig. 5A). Both interacting proteins, the ethylene receptor ETR2, as well as the calcium-binding PCM1 protein, inhibited StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake significantly (P< 0.001; Fig. 5A), whereas co-expression of the empty vector did not.

Fig. 5.

(A) StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake in yeast cells in the presence or absence of interaction partners. Co-expression of StSUT4-interaction partners StETR2 and StPCM1 reduces StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake. StSUT4 in pDR196 was co-expressed with the empty vector 112A1NE (red), StETR2 in 112A1NE (green) or StPCM1 in 112A1NE (blue). Data are means ±SD. Uptake was measured at pH 5. (B) Both sucrose transporters, StSUT1 as well as StSUT4 are efficiently inhibited by addition of 50 mM CaCl2 after 1 h of incubation at pH 3. Student‘s t-test was performed (***P<0.001).

Calcium ions affect functionality, expression, dimerization and targeting of StSUT4

Calcium ions inhibit StSUT1- and StSUT4-mediated uptake of esculin

As previously observed in 14C-sucrose uptake experiments using StSUT1 (Krügel et al., 2013), the activity of StSUT4 was drastically reduced in the presence of divalent cations such as calcium ions (Fig. 5B). The inhibitory effect of calcium ions on StSUT1, as well as StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake was confirmed by confocal microscopy using UV excitation (Supplementary Fig. S4B). This decrease in activity was postulated to be due to the removal of the transporter from the plasma membrane via endocytosis. Another possibility is that the expression strength or protein stability is negatively affected by increasing calcium concentrations.

Calcium (and magnesium) ions induce expression of StSUT4

In order to investigate whether reduced expression or protein abundance could be the reason for reduced StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake, the transcript accumulation and protein abundance was measured. Increasing StSUT4 transcript accumulation in the presence of calcium or magnesium ions compared with the water-treated control (Fig. 6A) helped to exclude that decreased expression might be the reason for reduced esculin uptake in the presence of increasing calcium (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 6.

Quantification of StSUT4 transcripts and protein accumulation in response to various inhibitors or effectors. (A) Quantification of StSUT4 transcript amount via qPCR analysis using ubiquitin as a reference gene after treatment of source leaf material with either 50 mM CaCl2, 50 mM MgCl2 or water. Plant material was harvested at different time points (0–5 h).(B) qPCR analysis of StSUT4 transcript amount in source leaf material treated with the translational inhibitor cycloheximide (10 µM) for the indicated period of time (0–5 h) show a transient increase in transcript accumulation. Student’s t-test was performed to obtain significance values (n=4; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, and *P<0.05). Ab: antibody. (C) Western blot analysis using the microsomal fraction of potato leaves incubated for several hours in water (water control), 10 µM of cycloheximide, or 50 mM CaCl2. Incubation for several hours in 50 mM CaCl2 show increased protein amount of StSUT4, but unchanged levels of StSUT1 protein. Cycloheximide effects on StSUT1 were published earlier (Kühn et al., 1997).

To test protein stability, western blots using the microsomal fraction of water, cycloheximide (CHX), or calcium chloride-treated potato leaves were performed (Fig. 6C). StSUT1 half-life in the presence of CHX was investigated earlier (Kühn et al., 1997). Usage of a specific affinity-purified StSUT4 peptide antibody (Weise et al., 2000) revealed a short protein half-life of StSUT4 in the presence of the translational inhibitor CHX (Fig. 6C), and a rather stabilizing effect in the presence of calcium chloride (Fig. 6C). No increase in the protein amount was detectable for StSUT1 (Fig. 6C). Therefore, a reduced protein stability can also be excluded as the reason for reduced uptake. A calcium-dependent regulation of StSUT4 at the post-translational level was more likely.

StSUT4 is regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level

Far-red light increases StSUT4 transcript abundance and StSUT4-RNAi plants do not show shade avoidance response and seem to be far-red light insensitive (Chincinska et al., 2008). Accumulation of StSUT4 mRNA is increased under far-red light enrichment, as is the case under canopy shade (Chincinska et al., 2008). This increase in StSUT4 transcript accumulation is under control of phytochrome B, given that in phyB antisense plants no such far-red light dependence is observed (Liesche et al., 2011). This increased accumulation is most likely due to increased transcript half-life, because in the presence of transcriptional inhibitors such as actinomycin D, by inhibiting de novo synthesis of StSUT4 transcripts, the degradation of this specific mRNA is delayed, as shown by quantitative qPCR (Liesche et al., 2011). Both observations suggest a tight control of StSUT4 transcript stability at the post-transcriptional level. Potentially, this permanent transcript degradation occurs under involvement of a far-red light sensitive photoreceptor such as phyB.

It was known from previous investigations that the half-life of StSUT2 and StSUT4 transcripts is also prolonged in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of translation (He et al., 2008; Fig. 6B. This suggests that very short-lived ribonucleases are engaged in continuous transcript degradation. This transient increase in StSUT4 transcript accumulation (Fig. 6B) has consequences on the protein amount, as seen in western blots in the presence of CHX (Fig. 6C).

Calcium ions increase internalization of StSUT4 (but not of StSUT1)

As shown previously using confocal microscopy, calcium ions were able to specifically induce internalization of StSUT4 protein (Fig. 7A), whereas no such effect was observed for StSUT1 (Fig. 7B), a high affinity sucrose transporter that is also able to interact with StPCM1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). These effects are time- and temperature-dependent. The effects were more pronounced at prolonged incubation (overnight) with the different effectors (CaCl2 or EDTA), and less pronounced at low temperature (4 °C; Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Changes in sub-cellular localization of StSUT1 and StSUT4 in response to CaCl2 treatment. (A) Overnight treatment with 50 mM CaCl2 at 21 °C induces increased vesicle formation of StSTUT4-YFP (shown in green) in the intracellular lumen of Nicotiana benthamiana epidermis cells, whereas water or EDTA do not. These effects are visible to a smaller extent if leaves were incubated in the cold (4 °C, upper row). YFP constructs (shown in green) were co-infiltrated with a PM marker (shown in orange) as before (Garg et al. 2020). (B) No internalization of StSUT1-YFP (green) from the plasma membrane was observed in response to overnight incubation of infiltrated leaves in 50 mM CaCl2 at 21 °C. StSUT1 remains co-localized with the PM marker protein (orange) even in the presence of high amounts of calcium. Images were taken 3-4 d after infiltration using the Airyscan detector after the indicated time of incubation. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Thus, not only homodimer formation, but also calcium ions affect sub-cellular targeting of StSUT4. The next question was whether or not calcium also affects the dimerization behaviour of StSUT4, and thereby indirectly, its sub-cellular localization.

Calcium inhibits StSUT4 homodimerization and activity

To investigate the role of calcium in regulating StSUT4 dimerization, split ubiquitin experiments were performed in yeast in the presence of increasing calcium concentrations (Supplementary Fig. S5). Whereas EDTA, as well as magnesium at high concentration impaired normal yeast growth, calcium ions were not harmful for normal yeast growth (Rees and Stewart, 1997). However, a clear inhibitory effect on homodimer formation was observed in the split ubiquitin system, and quantified with increasing amount of calcium (Supplementary Fig. S5). The question remains, whether the detrimental effect of calcium on StSUT4 activity is due to its increased internalization, its reduced dimerization, or both.

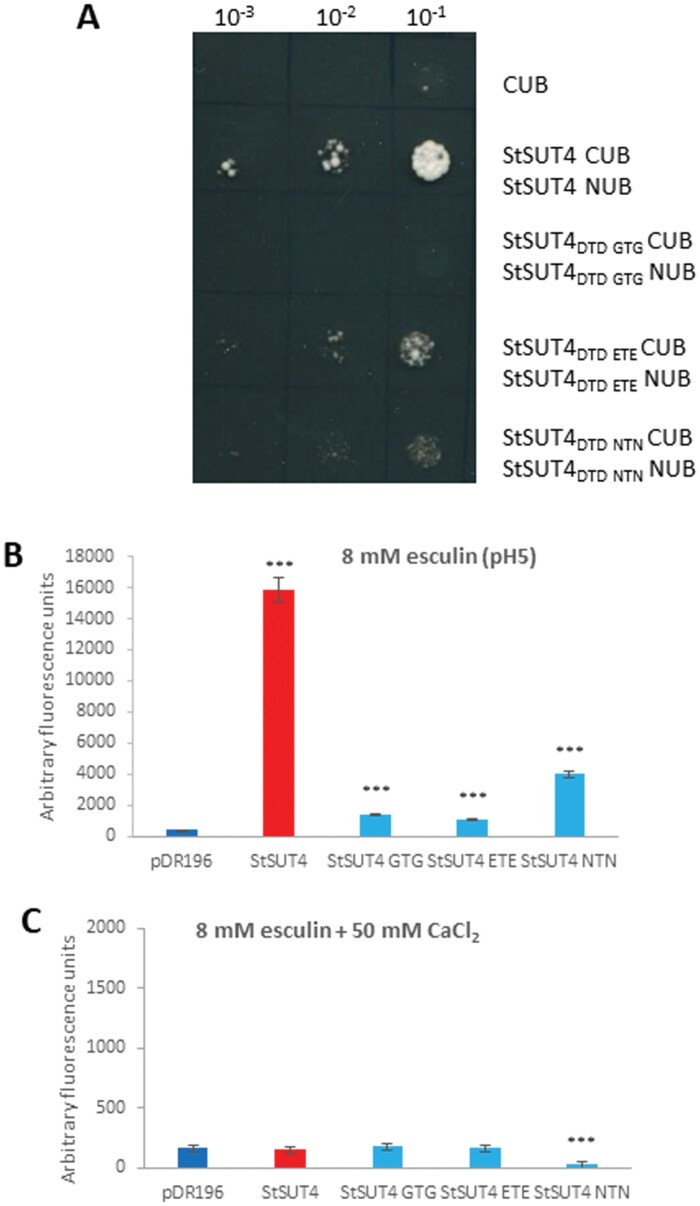

Site-directed mutagenesis of a diacidic motif inhibits transport activity

A highly conserved diacidic motif is present in all known sucrose transporters, and is localized in the seventh transmembrane spanning domain of all transporters. This motif represents a putative binding site of positively charged ions and seems to be crucial for sucrose transporter activities (Sun et al., 2012; Krügel et al., 2013).

We used site-directed mutagenesis of this highly conserved diacidic motif (D304T305D306) in order to dissect out the ability of plant sucrose transporters to dimerize, to be internalized, and their functionality.

Interestingly, the mutagenesis of this motif in StSUT4 also affects dimerization of the transporter, and only replacement of the two aspartic acid residues by glutamic acid residues seemed to allow residual dimer formation, arguing for a charge-dependence of the homodimer formation (Fig. 8A). Replacement of the two aspartic acid residues by uncharged amino acids such as glycine or asparagine completely disturbed homodimer formation (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

(A) Split ubiquitin system with mutagenized StSUT4 constructs where the highly conserved DTD motif within the seventh transmembrane spanning domain is replaced by either GTG, NTN, or ETE, show the importance of this motif for efficient homodimerization. (B) StSUT4-mediated esculin uptake after mutagenesis of the conserved DTD motif at optimal pH (pH 5) and substrate concentration (8 mM). Mutagenesis of the DTD motif strongly affects StSUT4 transport activity. (C) Neither StSUT4, nor the DTD mutant constructs of StSUT4 are functional in the presence of 50 mM CaCl2. Incubation time was 60 min. Note the difference in scale. Student’s t-test was performed to obtain significance values (n=4; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, and *P<0.05).

Regarding sucrose transport activity, this DTD motif is crucial, since its mutagenesis reduced esculin uptake by almost 90% (Fig. 8B). The inhibitory effect of calcium ions on the uptake behaviour of StSUT4 at an optimal of pH 5 was also detectable for the mutant constructs, indicating that homodimer formation alone was not responsible for internalization, and that the DTD motif does not represent a calcium binding domain (Fig. 8C). It can be assumed that homodimerization is not a pre-requisite for internalization.

Calcium-mediated inhibition of sucrose uptake does not require the highly conserved D304T305D306 motif that is essential for sucrose transport activity of StSUT1 as well as of StSUT4. Further investigations will be required to understand how the inhibitory effect by divalent cations is achieved.

Sub-cellular localization of the mutant constructs of the highly conserved diacidic DTD motif suggests another function. Diacidic motifs within the C-terminal region of aquaporins have been described to be responsible for efficient ER export of homo- or heteromeric complexes (Zelazny et al., 2009). Therefore, the sub-cellular localization of the SDM constructs were analysed in detail (Fig. 9). None of the mutants co-localized with the peptide transporter PTR2, that can be used as a vacuolar marker protein. Replacement of the DTD motif by either GTG, NTN or ETE enhanced plasma membrane targeting (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Sub-cellular localization of StSU4 mutants. Co-localization experiments with StSUT4 mutant constructs co-infiltrated with either vacuolar (PTR2-YFP) or plasma membrane (CBL1-OFP) marker proteins. (A, B, D) None of the DTD mutant constructs could be co-localized with the vacuolar marker protein PTR2-YFP (arrow). (C, E) The StSUT4 DTD ETE-YFP and the StSUT4 DTD NTN-YFP construct show perfect overlap with the plasma membrane marker CBL1-OFP. Images were taken 3 d after infiltration using the Airyscan detector. Scale bars represent 10 µm (A, B, D, E) or 20 µm (C).

In conclusion, the highly conserved DTD motif is required for functionality and dimerization of sucrose transporters, but not for calcium-mediated inhibition of sucrose transport capacity, since mutant constructs of StSUT4 with replacement of the two aspartic acid residues can still be inhibited by the supply of calcium chloride (Fig. 8B, C). Although the capacity to form homodimers seems to be reduced in the mutants, the efficiency of plasma membrane targeting is rather enhanced (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Characterization of StSUT4-mediated uptake

We have shown for the first time, that the fluorescent esculin uptake assay is not only useful for activity measurement of type I sucrose transporters (Gora et al., 2012; Reinders et al., 2012), but could also be established for a low affinity type III sucrose transporter of the SUT4 clade (Kühn and Grof, 2010) if the substrate concentration is adapted. Using this activity assay, it was possible to investigate further effectors on SUT4 transport activity, as well as confirm the pH dependence previously measured by 14C-sucrose transport assays (Weise et al., 2000). Thereby, the strong difference not only in substrate affinity, but also pH dependence between SUT1 (type I) and SUT4 (type III) transporters could be elucidated (Fig. 4).

Furthermore, we showed that both transporters are efficiently inhibited by divalent cations such as calcium or magnesium (Fig. 5B; Krügel et al., 2013). At least in the case of StSUT4, it can be excluded that this decrease in activity is due to a decreased expression or reduced protein abundance.

Interestingly, internalization to luminal vesicles can be induced by calcium treatment in the case of StSUT4, but not for StSUT1 (Fig. 7). Both homodimerization as well as calcium treatment seem to favour internalization of StSUT4. Since calcium in parallel impairs homodimer formation of StSUT4, it is concluded that homodimerization is not a pre-requisite for internalization.

Site directed mutagenesis of a highly conserved di-acidic motif within the seventh transmembrane spanning domain revealed an essential function for StSUT4 activity (Fig. 7B), as is was previously shown for other sucrose transporters such as OsSUT1 (Sun et al., 2012) and StSUT1 (Krügel et al., 2013). This motif seems to be also required for StSUT4 homodimer formation (Fig. 8A). But it is unlikely that it represents a putative calcium binding domain, since calcium-dependent inhibition of transport activity is still observed after replacement of this motif (Fig. 8C).

StSUT4 is co-expressed and interacts with StETR2

Ethylene, as well as gibberellic acid and auxin are involved in the shade avoidance response of higher plants (Pierik et al., 2004a). Phytochrome B (PhyB) is responsible for the perception of the red: far-red light ratio and triggers the shade avoidance response involving elongated internode growth, early flowering, and hyponastic leaf movement (Ballaré, 2017). It was shown in tobacco plants that an increase in far-red light is accompanied by an increase in ethylene production (Pierik et al., 2004a), and that ethylene-insensitive tobacco plants show only a reduced shade avoidance response (Pierik et al., 2004b). Transgenic potato plants with reduced StSUT4 expression are also defective in the shade avoidance response (Chincinska et al., 2008), and produce lower amounts of ethylene (Chincinska et al., 2013). At the same, time the transcript amount of the key enzyme of ethylene biosynthesis, ACC oxidase, shows reduced levels in StSUT4-silenced potato plants (Chincinska et al., 2008), suggesting that StSUT4 and ethylene biosynthesis are tightly linked to each other. Reduced ethylene biosynthesis in these plants could be the reason for the missing shade avoidance syndrome of StSUT4-RNAi plants (Chincinska et al., 2008).

StSUT4 was shown to be important for the phyB-dependent shade avoidance syndrome of potato plants (Chincinska et al., 2008, 2013). StSUT4 transcripts accumulate in response to increased far-red light enrichment under canopy shade in a phyB-dependent manner (Chincinska et al., 2008). This increase in transcript abundance under shade conditions is not due to increased transcriptional activity, but rather due to increased transcript stability (Liesche et al., 2011) and the photoreceptor PhyB seems to be involved in this increased transcript stability as seen in phyB antisense potato plants (Liesche et al., 2011). Here again, it was confirmed that StSUT4 transcript stability is tightly controlled post-transcriptionally not only in a light quality-dependent manner (Liesche et al., 2011), but also by short lived proteins such as ribonucleases (Fig. 6A; He et al., 2008)).

Interactome of StSUT4

Elucidation of the StSUT4 interactome reveals the presence of several cell wall-localized interaction partners, among them, two different pectate lyases (Table 1). A recent study describes a strong link between ethylene signalling, calcium signalling, sugar transport and cell wall remodelling as an important target of ethylene perception, with respect to pollen tube growth in tomato plants (Althiab-Almasaud et al., 2021). The authors identified the link via transcriptome analysis of ETR loss-of-function as well as gain-of-function mutants in tomato without describing the connection at the molecular level. The StSUT4-ETR2 interaction might represent a link as to how sucrose, calcium and ethylene signalling are interconnected by direct physical contact.

Sucrose and ethylene are involved in the entrainment of the circadian clock

The ethylene receptor ETR2 is known to interact with itself and with ETR1, another ethylene receptor protein that is expressed in the phloem, and ERS1 (Grefen et al., 2008). In tomato plants, SlSUT4 and ETR2 are co-expressed, according to the TomExpress database (Supplementary Fig. S1), and also in Arabidopsis, a link between the ethylene perception and sucrose metabolism is suggested by the co-expression of AtETR2 with the sucrose synthase AtSUS4 (according to ATTED II database).

A link between ethylene signalling and the sucrose status is also evident in the regulation of circadian genes: sucrose and ethylene are both involved in the entrainment of the circadian clock (Haydon et al., 2017). It is suggested that the sugar-dependent entrainment of the circadian clock occurs via the transcription factor bZIP63 (Frank et al., 2018). Sugars are required to adjust the phase of the circadian clock by repressing PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR (PRR7), an inhibitor of CIRCADIAN CLOCK-ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1; Haydon et al., 2013). It was shown by inhibition of photosynthesis, that endogenous oscillation of sugars represents a kind of metabolic feedback signal, that entrains and maintains circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. This endogenous sugar oscillation entrains the circadian oscillator by repressing the morning-expressed gene PRR7. It is assumed that sugars repress the pseudo-response regulator PRR7 during the morning to adjust the phase of the circadian clock (Haydon et al., 2013).

Furthermore, it is known that GIGANTEA (GI) is needed to sustain sucrose-dependent circadian rhythms in the dark. Herein, sucrose is supposed to stabilize the GI protein in darkness, thereby involving CTR1, a negative regulator of ethylene signalling that acts upstream of GI.

Ethylene shortens the circadian period, and sucrose can mask these negative effects of ethylene on the circadian system by stabilizing circadian oscillator proteins (Haydon et al., 2017). A further ethylene signalling component, EIN3, is destabilized by sugar (Yanagisawa et al., 2003).

From StSUT4-silenced potato plants we learned that the oscillation of sugars and its export from leaves is delayed in StSUT4-RNAi plants, suggesting that the entrainment of the circadian clock is disturbed (Chincinska et al., 2008). Not only is the accumulation of soluble sugars and starch delayed in StSUT4-RNAi plants, but also the expression of the main phloem loader StSUT1 that oscillates with lower amplitude when StSUT4 is silenced (Supplementary Fig. S6A). In parallel, diurnal ethylene production is completely abolished in StSUT4-RNAi potato plants (Chincinska et al., 2013). The transcript abundance of GI is also affected in StSUT4-silenced potato plants (Chincinska et al., 2013). In this context it would be interesting to quantify GI protein stability. The quantification of relevant components of the ethylene signal transduction pathway via real time qPCR revealed up-regulation of EIN3 in in StSUT4 overexpressing plants (Supplementary Fig. S6B). It remains to be answered whether overexpression of StSUT4 causes a similar shift in sucrose oscillation in potato leaves leading to out of phase-oscillation of sucrose-responsive genes, as shown for Arabidopsis (Supplementary Fig. S7, S8).

In a number of species, the level of mature miR172 also changes during the day (Wang et al., 2016). A previous investigation showed sucrose-inducibility of miR172 transcript accumulation, changes of miR172 transcript level during the day, and induction of miR172 transcript levels in StSUT4-RNAi plants (Garg et al., 2021). It is therefore assumed that StSUT4 is involved in the maintenance and adjustment of the phase of the circadian clock via changes in sucrose oscillation. Out of phase oscillation of sucrose levels in the leaves of StSUT4-silenced plants might be responsible for increased levels of mature miR172, early flowering and tuberization under non-inductive photoperiodic conditions (summarized in Supplementary Fig. S7). It cannot be excluded that other circadian clock-dependent processes are also affected in these plants (Supplementary Fig. S8).

A very recent study identifies StSUT4, together with the sugar transporter SUGARS WILL EVENTUALLY BE EXPORTED TRANSPORTER (SWEET11) as core circadian clock genes in below-ground storage organs, showing a robust circadian transcriptional rhythm in detached tubers independent from leaves, with important implication for the regulation of tuberization in potato crop plants (Hoopes et al., 2022). These transcriptomic data further strengthen the hypothesis of StSUT4 as a key component of the circadian clock in potato tubers.

Supplementary data

The following supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Co-expression of ETR2 and SUT4.

Fig. S2. Confirmation of interaction in yeast.

Fig. S3. StPCM1 interactions.

Fig. S4. Microscopic analysis of yeast cells after esculin incorporation.

Fig. S5. Homodimerization of StSUT4 in the presence of calcium.

Fig. S6. Expression analysis of StSUT4-RNAi plants.

Fig. S7. Hypothetical model illustrating the link between sucrose and ethylene signalling via StSUT4 and StETR2 interaction affecting the entrainment of the circadian clock.

Fig. S8. Hypothetical model illustrating the impact of sucrose in the entrainment of the circadian clock.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge excellent care of green house plants by Angelika Pötter and we thank Undine Krügel for help with yeast experiments. We thank Doris Rentsch (University of Bern) for the vacuolar marker protein and Jörg Kudla (University of Münster) for the plasma membrane marker.

Contributor Information

Varsha Garg, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biology, Department of Plant Physiology, Philippstr. 13 Building 12, 10115 Berlin, Germany.

Jana Reins, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biology, Department of Plant Physiology, Philippstr. 13 Building 12, 10115 Berlin, Germany.

Aleksandra Hackel, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biology, Department of Plant Physiology, Philippstr. 13 Building 12, 10115 Berlin, Germany.

Christina Kühn, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institute of Biology, Department of Plant Physiology, Philippstr. 13 Building 12, 10115 Berlin, Germany.

James Murray, Cardiff University, UK.

Author contributions

VG performed and designed experiments; JR performed the split ubiquitin screen; AH performed experiments and supervised student work; CK wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

Financial support came from DFG SPP1530 to CK.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within this paper and within the supplementary material published online.

References

- Althiab-Almasaud R, Chen Y, Maza E, Djari A, Frasse P, Mollet JC, Mazars C, Jamet E, Chervin C.. 2021. Ethylene signaling modulates tomato pollen tube growth through modifications of cell wall remodeling and calcium gradient. Plant Journal 107, 893–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré, CL, and Pierik, R.. 2017. The shade-avoidance syndrome: multiple signals and ecological consequences. Plant Cell and Environment 40,2530–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterlich M, Krügel U, Boldt-Burisch K, Franken P, Kühn C.. 2014. The sucrose transporter SlSUT2 from tomato interacts with brassinosteroid functioning and affects arbuscular mycorrhiza formation. The Plant Journal 78, 877–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chincinska I, Gier K, Krügel U, Liesche J, He H, Grimm B, Harren FJ, Cristescu SM, Kühn C.. 2013. Photoperiodic regulation of the sucrose transporter StSUT4 affects the expression of circadian-regulated genes and ethylene production. Frontiers in Plant Science 4, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chincinska IA, Liesche J, Krügel U, Michalska J, Geigenberger P, Grimm B, Kühn C.. 2008. Sucrose transporter StSUT4 from potato affects flowering, tuberization, and shade avoidance response. Plant Physiology 146, 515–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A, Matiolli CC, Viana AJC, et al. 2018. Circadian entrainment in Arabidopsis by the sugar-responsive transcription factor bZIP63. Current Biology 28, 2597–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V, Hackel A, Kühn AC.. 2020. Subcellular targeting of plant sucrose transporters Is affected by their oligomeric state. Plants (Basel) 9, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V, Hackel A, Kühn C.. 2021. Expression level of mature miR172 in wild type and StSUT4-silenced plants of Solanum tuberosum is sucrose-dependent. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, 1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehl C, Waadt R, Kudla J, Mendel RR, Hansch R.. 2009. New GATEWAY vectors for high throughput analyses of protein-protein interactions by bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Molecular Plant 2, 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA.. 2002. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods in Enzymology 350,87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler H, Lalowski M, Stelzl U, et al. 2004. A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of huntingtin aggregation, to Huntington’s disease. Molecular Cell 15, 853–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gora PJ, Reinders A, Ward JM.. 2012. A novel fluorescent assay for sucrose transporters. Plant Methods 8, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefen C, Stadele K, Ruzicka K, Obrdlik P, Harter K, Horak J.. 2008. Subcellular localization and in vivo interactions of the Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene receptor family members. Molecular Plant 1, 308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch F, Jaspar H, von Sivers L, Bitterlich M, Franken P, Kuhn C.. 2020. Brassinosteroids and sucrose transport in mycorrhizal tomato plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior 15, 1714292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon MJ, Mielczarek O, Frank A, Roman A, Webb AAR.. 2017. Sucrose and ethylene signaling interact to modulate the circadian clock. Plant Physiology 175, 947–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon MJ, Mielczarek O, Robertson FC, Hubbard KE, Webb AA.. 2013. Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature 502, 689–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Chincinska I, Hackel A, Grimm B, Kühn C.. 2008. Phloem mobility and stability of sucrose transporter transcripts. The Open Plant Science Journal 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hellens R, Mullineaux P, Klee H.. 2000. Technical focus: a guide to Agrobacterium binary Ti vectors. Trends in Plant Sciences 5, 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho LH, Lee YI, Hsieh SY, et al. 2021. GeSUT4 mediates sucrose import at the symbiotic interface for carbon allocation of heterotrophic Gastrodia elata (Orchidaceae). Plant Cell & Environment 44, 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes GM, Zarka D, Feke A, Acheson K, Hamilton JP, Douches D, Buell CR, Farre EM.. 2022. Keeping time in the dark: Potato diel and circadian rhythmic gene expression reveals tissue-specific circadian clocks. Plant Direct 6, e425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung JK, Ramm EI, Pabo CO.. 2000. A bacterial two-hybrid selection system for studying protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 97, 7382–7387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Chang C.. 2012. Advances in ethylene signalling: protein complexes at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Annals of Botany Plants 2012, pls031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, De Meyer B, Hilson P.. 2005. Modular cloning and expression of tagged fluorescent proteins in plant cells. Trends in Plant Science 10, 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krügel U, He HX, Gier K, Reins J, Chincinska I, Grimm B, Schulze WX, Kühn C.. 2012. The potato sucrose transporter StSUT1 interacts with a DRM-associated protein disulfide isomerase. Molecular Plant 5, 43–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krügel U, Veenhoff LM, Langbein J, Wiederhold E, Liesche J, Friedrich T, Grimm B, Martinoia E, Poolman B, Kühn C.. 2008. Transport and sorting of the solanum tuberosum sucrose transporter SUT1 is affected by posttranslational modification. The Plant Cell 20, 2497–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krügel U, Wiederhold E, Pustogowa J, Hackel A, Grimm B, Kühn C.. 2013. Site directed mutagenesis of StSUT1 reveals target amino acids of regulation and stability. Biochimie 95, 2132–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn C, Franceschi VR, Schulz A, Lemoine R, Frommer WB.. 1997. Macromolecular trafficking indicated by localization and turnover of sucrose transporters in enucleate sieve elements. Science 275, 1298–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn C, Grof CP.. 2010. Sucrose transporters of higher plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 13, 288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesche J, He HX, Grimm B, Schulz A, Kühn C.. 2010. Recycling of Solanum sucrose transporters expressed in yeast, tobacco, and in mature phloem sieve elements. Molecular Plant 3, 1064–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesche J, Krügel U, He H, Chincinska I, Hackel A, Kühn C.. 2011. Sucrose transporter regulation at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational level. Journal of Plant Physiology 168, 1426–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesche J, Schulz A, Krügel U, Grimm B, Kühn C.. 2008. Dimerization and endocytosis of the sucrose transporter StSUT1 in mature sieve elements. Plant Signaling & Behavior 3, 1136–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Adam H, Diaz-Mendoza M, Zurczak M, Gonzalez-Schain ND, Suarez-Lopez P.. 2009. Graft-transmissible induction of potato tuberization by the microRNA miR172. Development 136, 2873–2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik P, El-Bakkoury M, Hamacher T, et al. 2004. K+ channel interactions detected by a genetic system optimized for systematic studies of membrane protein interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101, 12242–12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierik R, Cuppens ML, Voesenek LA, Visser EJ.. 2004a. Interactions between ethylene and gibberellins in phytochrome-mediated shade avoidance responses in tobacco. Plant Physiology 136, 2928–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierik R, Whitelam GC, Voesenek LA, de Kroon H, Visser EJ.. 2004b. Canopy studies on ethylene-insensitive tobacco identify ethylene as a novel element in blue light and plant-plant signalling. The Plant Journal 38, 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poovaiah BW, Takezawa D, An G, Han TJ.. 1996. Regulated expression of a calmodulin isoform alters growth and development in potato. Journal of Plant Physiology 149, 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees EMR, Stewart GG.. 1997. The effects of increased magnesium and calcium concentrations on yeast fermentation performance in high gravity worts. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 103, 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Reinders A, Schulze W, Kühn C, Barker L, Schulz A, Ward JM, Frommer WB.. 2002. Protein-protein interactions between sucrose transporters of different affinities colocalized in the same enucleate sieve element. The Plant Cell 14, 1567–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders A, Sivitz AB, Ward JM.. 2012. Evolution of plant sucrose uptake transporters. Frontiers in Plant Science 3, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Lin Z, Reinders A, Ward JM.. 2012. Functionally important amino acids in rice sucrose transporter OsSUT1. Biochemistry 51, 3284–3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa D, Liu ZH, An G, Poovaiah BW.. 1995. Calmodulin gene family in potato: developmental and touch-induced expression of the mRNA encoding a novel isoform. Plant Molecular Biology 27, 693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Sun MY, Wang XS, Li WB, Li YG.. 2016. Over-expression of GmGIa-regulated soybean miR172a confers early flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, 645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise A, Barker L, Kühn C, Lalonde S, Buschmann H, Frommer WB, Ward JM.. 2000. A new subfamily of sucrose transporters, SUT4, with low affinity/high capacity localized in enucleate sieve elements of plants. The Plant Cell 12, 1345–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weschke W, Panitz R, Sauer N, Wang Q, Neubohn B, Weber H, Wobus U.. 2000. Sucrose transport into barley seeds: molecular characterization of two transporters and implications for seed development and starch accumulation. The Plant Journal 21, 455–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa S, Yoo SD, Sheen J.. 2003. Differential regulation of EIN3 stability by glucose and ethylene signalling in plants. Nature 425, 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazny E, Miecielica U, Borst JW, Hemminga MA, Chaumont F.. 2009. An N-terminal diacidic motif is required for the trafficking of maize aquaporins ZmPIP2;4 and ZmPIP2;5 to the plasma membrane. The Plant Journal 57, 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within this paper and within the supplementary material published online.