Abstract

The human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor subtype 1 (hTAAR1) is a G protein-coupled receptor that has therapeutic potential for multiple diseases, including schizophrenia, drug addiction, and Parkinson’s Disease. Although several potent agonists have been identified and have shown positive results in various clinical trials for schizophrenia, the discovery of potent hTAAR1 antagonists remains elusive. Herein, we report the results of structure-activity relationship studies that have led to the discovery of a potent hTAAR1 antagonist (RTI-7470–44, 34). RTI-7470–44 exhibited an IC50 of 8.4 nM in an in vitro cAMP functional assay, a Ki of 0.3 nM in a radioligand binding assay, and showed species selectivity for hTAAR1 over the rat and mouse orthologues. RTI-7470–44 displayed good blood-brain barrier permeability, moderate metabolic stability, and a favorable preliminary off-target profile. Finally, RTI-7470–44 increased the spontaneous firing rate of mouse VTA dopaminergic neurons and blocked the effects of the known TAAR1 agonist RO5166017. Collectively, this work provides a promising hTAAR1 antagonist probe that can be used to study TAAR1 pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in hypodopaminergic diseases such as Parkinson’s Disease.

Keywords: Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 antagonist, cAMP functional assay, structure-activity relationship, Parkinson’s Disease, dopaminergic neurons, spontaneous firing rate

Introduction

The human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor subtype 1 (hTAAR1) is a Gαs coupled intracellular G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is activated by trace amines, such as β-phenethylamine (PEA) and tyramine.1–3 The endogenous trace amines that activate hTAAR1 share structural and metabolic similarities to the biogenic monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT), and norepinephrine (NE).2–4 hTAAR1-mediated signal transduction via Gαs results in the stimulation of intracellular cAMP, but studies have shown the receptor also signals independently of G protein activation through the β-arrestin-2 signaling cascade2,4–5 and through Gα13 proteins to mediate RhoA activation.6 In the Central Nervous System (CNS), hTAAR1 is highly expressed in multiple brain regions (ventral tegmental area – VTA, raphe nuclei, locus ceruleus, and substantia nigra pars compacta – SNpc) and moderately expressed in others (basal ganglia, dorsal striatum, nucleus accumbens, dorsal striatum, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex).2,7–8 Because hTAAR1 is expressed in monoaminergic nuclei in predominantly dopaminergic and serotonergic brain regions, it has the potential to make a large impact in drug discovery for diseases related to monoaminergic signaling, including substance abuse disorders, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s Disease (PD).9

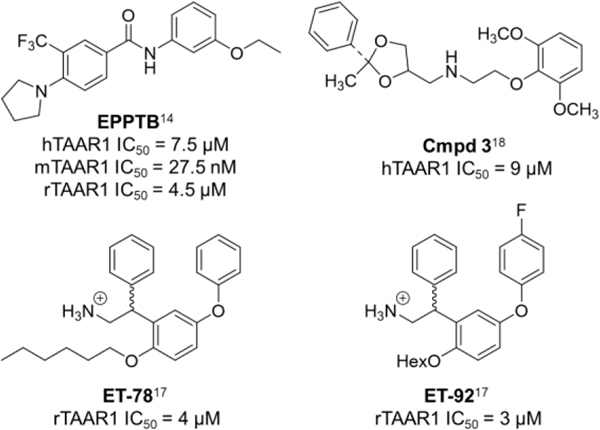

While synthetic and endogenous hTAAR1 agonists have been developed (for a detailed review9), some with therapeutic potential for schizophrenia and substance abuse disorders,1,10–13 the discovery of TAAR1 antagonists remains surprisingly difficult. In the literature, the Hoffman-La Roche antagonist, N-(3-ethoxyphenyl)-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide (EPPTB), is the only fully characterized TAAR1 antagonist (Figure 1). EPPTB is a potent mTAAR1 antagonist (IC50 = 27.5 nM) but is 272-fold and 165-fold less potent at hTAAR1 (IC50 = 7.5 μM) and rTAAR1 (IC50 = 4.5 μM), respectively.14 Additional studies have shown that EPPTB may be an inverse agonist, as the compound was able to reduce mTAAR1-stimulated cAMP production (−12.3 ± 4.7%).14 Because of its favorable brain/plasma ratio of 0.5, EPPTB has been used in animal studies examining DA neurotransmission,14 but its high clearance limits the extent of studies that can be performed.1,15–16 Therefore, additional antagonists with better ADME properties and potency profiles are needed to help further explore TAAR1 pharmacology.1,16 In the literature, a few additional antagonists have been identified (Cmpd 3, ET-54, ET-78),17–18 but all have weak potencies and none have been fully characterized at human, rat, and mouse TAAR1, making potency comparisons difficult (Figure 1; Cmpd 3: hTAAR1 IC50 = 9 μM, ET-54: rTAAR1 IC50 = 3 μM, ET-78: rTAAR1 IC50 = 4 μM).

Figure 1.

TAAR1 antagonists in the literature.

While hTAAR1 agonists have shown promise as therapeutics for disorders characterized by hyperactive DA-ergic signaling, research has revealed a potential role for hTAAR1 antagonists in hypoactive DA-ergic disease states, such as PD. TAAR1−/− mice display increased DA-ergic neuronal firing, increased sensitivity to DA-ergic stimuli, and over-active D2 receptor activity, all of which are characteristics of a generalized hyperactive DA state.8,19–21 Blocking TAAR1 activity via a pharmacological antagonist (EPPTB) also results in an increase in DA-ergic neuronal firing.14 Taken together, these results highlight the need for identification of hTAAR1 antagonists to further probe the receptor’s unique role in hypoactive DA-ergic states. The lack of suitable hTAAR1 antagonists remains a major roadblock to understanding the role of hTAAR1 in the CNS.1,16

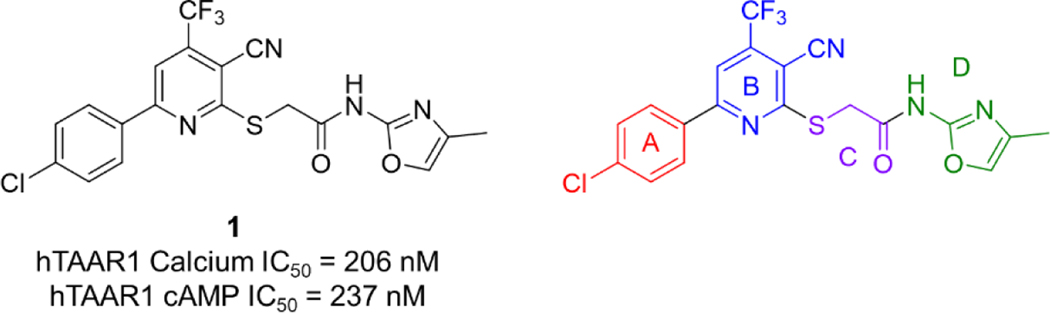

Recently we reported the identification of two potent hTAAR1 antagonists from a high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign using a calcium mobilization-based hTAAR1 assay.22 Herein, we report structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of antagonist #1 from the previous study (1, IC50 = 206 nM) in an effort to understand the structural requirements to maintain high potency at hTAAR1. For our medicinal chemistry approach, we divided the base scaffold into 4 structural features (A-D, Figure 2). Area A is the 4-chlorophenyl group appended to the pyridine ring and area B is the core 2-cyano-3-trifluoromethylpyridine structure. Area C is comprised of an acetamide linked to the pyridine core while area D is the 2-oxazole attached to the acetamide. The present study focused on areas A and D. A total of 37 compounds with varying structural elements in these key areas were evaluated for hTAAR1 antagonist potency. Herein we describe the SAR studies, as well as species selectivity, radioligand binding, preliminary ADME properties, and neuronal firing effects for potent TAAR1 antagonists.

Figure 2.

Compound 1 structure and key areas for medicinal chemistry SAR.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry.

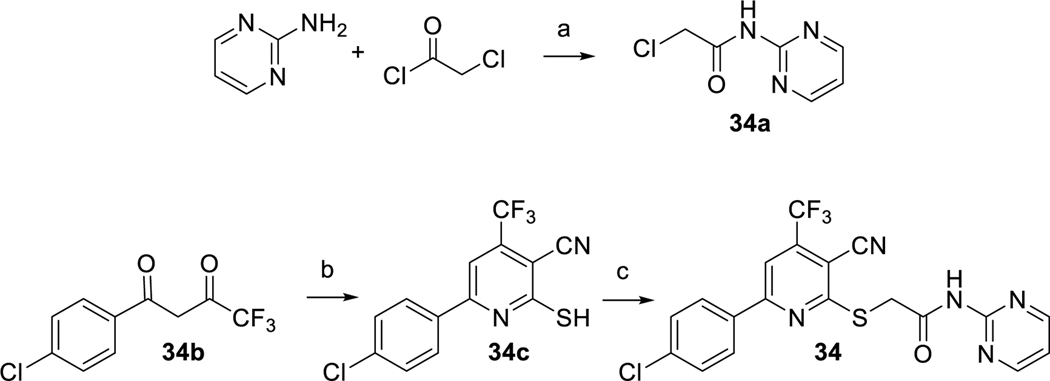

The 37 compounds evaluated in this study were purchased from ChemBridge Corporation (San Diego, CA) and ChemDIV (San Diego, CA) in small quantities. Compound 34 was additionally synthesized in our laboratory to provide scaled up quantities of material for in depth biological evaluations (Scheme 1). Compound 34 was prepared by alkylation of 34c with α-chloroacetic acid amide 34a in DMF at room temperature using 1 equivalent of aqueous KOH following a method previously described.23 Amide 34a was obtained by acylating 2-aminopyrimidine with chloroacetyl chloride in DCM in the presence of potassium carbonate. Sulfide 34c was obtained by condensing 2-cyanothioacetamide with 4-chlorobenzoyltrifluoroacetone 34b using a method also described previously.24

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of lead compound 34. Reagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3 (2 equiv), DCM, rt, 4 h; (b) cyanothioacetamide (1.5 equiv), DABCO (1 equiv), EtOH, reflux, 3 h; (c) KOH (1 equiv), DMF, rt, 12 h.

Biological Results and SAR Studies.

The HTS campaign described previously measured hTAAR1 activity via calcium mobilization with stable CHO-Gαq16-hTAAR1 cells, which allow the Gαs-coupled receptor to signal through mobilization of internal calcium through coupling to the promiscuous Gαq16 protein.22,25 While this assay platform worked well and was highly amenable to our HTS efforts, we opted to develop a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) cAMP immunoassay (LanceUltra kit, PerkinElmer) to measure native hTAAR1-mediated signal transduction through Gαs using stable hTAAR1-CHO cells. This assay technology has been successfully utilized in our research group for multiple GPCR targets.26–27 In our hTAAR1 cAMP assay, the control agonist PEA has an EC50 value of 193 ± 15 nM (Figure S1A), which compares well with the literature (138–260 nM).18,28 In this assay, our original lead antagonist 1 has an IC50 value of 237 ± 29 nM. For this study, all test compounds were evaluated for both antagonist and agonist activity using the hTAAR1 cAMP assay. Test compound IC50 values were determined with 8-point concentration response curves run against the PEA EC60 and agonist activity was determined by a 10 μM single concentration screen.

The first iteration of compounds in our SAR by catalog approach contained structural changes in areas A and D in an effort to explore how crucial the 4-chlorophenyl (area A) and the 2-aminooxazole (area D) were to maintain hTAAR1 activity (Table 1). Our initial thought was to alter both features simultaneously, believing that small structural changes in either location would not induce large changes in activity. This was found not to be the case, as all of the changes resulted in dramatic reductions in activity. Keeping the 2-aminooxazole (area D) and replacing the 4-chlorophenyl with methylenedioxyphenyl (2) and 4-pyridine (3) resulted in loss of activity. Removing the aromatic component in area A and introducing a phenyl ring in area D also resulted in loss of antagonist activity (4, IC50 > 10 μM). The next series of compounds (5 to 12) examined the effects of para-substituted aromatic rings (4-methylphenyl, 4-ethoxyphenyl, 4-fluorophenyl, and 4-methoxyphenyl) in area A combined with substituted phenyl rings (4-methoxyphenyl, fluorophenyl, methylphenyl, 4-ethoxycarbonylphenyl) in area D. All of these modifications resulted in compounds with loss of activity (IC50 > 10 μM). Four compounds with an unsubstituted phenyl ring in area A and various heterocyclic substitutions in area D (13 to 16) abolished hTAAR1 activity as well (IC50 > 10 μM). The remaining set of compounds in this group replaced the 4-chlorophenyl in area A with a 2-thiophene group (17 to 25) and examined a variety of heterocycles and phenyl substitutions in area D; all resulted in loss of activity (IC50 > 10 μM). In the agonist screen, none of the compounds displayed activity at 10 μM with the exception of 2, which greatly reduced hTAAR1-mediated cAMP production at 10 μM (−71%) and moderately reduced cAMP production at 3.16 μM (−20%). Compound 2 did not produce a typical concentration response, possibly indicating that the inverse agonist activity may be very weak or be due to nonspecific signaling at these concentrations (Figure S2A).

Table 1.

hTAAR1 antagonist activity of compound 1 analogs with modifications at sites A and D.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | hTAAR1 IC50, nMa |

| 1 | 4-chlorophenyl |

|

237 ± 29 (n=3) (95 ± 4% inhibition) |

| 2 |

|

|

>10,000 |

| 3 |

|

|

>10,000 |

| 4 | methyl | phenyl | >10,000 |

| 5 | 4-methylphenyl | 4-methoxyphenyl | >10,000 |

| 6 | 4-methylphenyl | 2-fluorophenyl | >10,000 |

| 7 | 4-methylphenyl | 4-fluorophenyl | >10,000 |

| 8 | 4-ethoxyphenyl | 2-fluorophenyl | >10,000 |

| 9 | 4-fluorophenyl | 4-methoxyphenyl | >10,000 |

| 10 | 4-fluorophenyl | 3-methylphenyl | >10,000 |

| 11 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 4-methylphenyl | >10,000 |

| 12 | 4-methoxyphenyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 13 | phenyl | 2-cyanophenyl | >10,000 |

| 14 | phenyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 15 | phenyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 16 | phenyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 17 | 2-thienyl | 3-bromophenyl | >10,000 |

| 18 | 2-thienyl | benzyl | >10,000 |

| 19 | 2-thienyl | 4-nitrophenyl | >10,000 |

| 20 | 2-thienyl | 3-trifluoromethylphenyl | >10,000 |

| 21 | 2-thienyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 22 | 2-thienyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 23 | 2-thienyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 24 | 2-thienyl |

|

>10,000 |

| 25 | 2-thienyl |

|

>10,000 |

IC50 values are the means ± S.E.M. of two independent experiments performed in duplicate unless otherwise indicated, as described in the Methods. Percent inhibition is calculated with the equation % Inhibition = [1 – (compound signal / PEA EC60 signal)] × 100.

Because the various modifications in areas A and D all resulted in loss of hTAAR1 antagonist activity, in our second iteration, we opted to examine a set of compounds with changes only in area D, thinking that perhaps the 4-chlorophenyl is required to maintain activity (Table 2). A set of 12 amides was assessed, most of which contained a ring to mimic the oxazole found in 1. Analog 26 with a 5-membered pyrrolidine retained the antagonist activity of 1, resulting in a compound with IC50 = 357 nM (1.5-fold less potent than 1). Increasing the ring size to 6 (27) and 7 (28) abolished activity suggesting a steric constraint on that side of the scaffold. Moving the nitrogen outside the piperidine (29) also abolished activity. Adding an additional heteroatom to piperidine 27, as in 4-methylpiperazine 30 and morpholine 31, showed improved activity compared to 27 (IC50 = 2500 nM and 1120 nM respectively), but reduced hTAAR1 antagonist activity by 11-fold and 4.7-fold, respectively, compared to 1. Next, a series of compounds was tested that kept the secondary amide and replaced the oxazole from 1 with a variety of heterocycles. Phenyl analog 32 resulted in loss of activity while 2-pyridine analog 33 (IC50 = 421 nM) was 1.8-fold less potent compared to 1. Adding a second nitrogen to the pyridine to form 2-pyrimidine 34, increased potency by 28-fold (IC50 = 8.4 nM) compared to 1. Changing the aromatic ring to a 4-methoxyphenyl (35) and 2-fluorophenyl (36) resulted in loss of activity. The final analog (37) examined a simple methylamine in area D, which was 4-fold less potent (IC50 = 985 nM) compared to 1. In the agonist screen, none of the compounds displayed activity at 10 μM with the exception of 34, which reduced hTAAR1-mediated cAMP production at 10 μM (−12.6%), but did not show any reduction at lower concentrations (Figure S2B) and importantly did not show reduction at the concentrations tested for antagonist activity. Interestingly, this activity is very similar to the inverse agonist activity reported for EPPTB at mTAAR1 (−12.3%).

Table 2.

hTAAR1 antagonist activity of compound 1 analogs with modifications at site D.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R1 | hTAAR1 IC50 (nM)a |

| 1 |

|

237 ± 29 (n=3) (95 ± 4% inhibition) |

| 26 |

|

357 ± 31 (n=3) (97 ± 4% inhibition) |

| 27 |

|

>10,000 |

| 28 |

|

>10,000 |

| 29 |

|

>10,000 |

| 30 |

|

2500 ± 1040 (n=3) (85 ± 2% inhibition) |

| 31 |

|

1120 ± 150 (n=3) (104 ± 1% inhibition) |

| 32 |

|

>10,000 |

| 33 |

|

421 ± 120 (n=3) (104 ± 0% inhibition) |

| 34 |

|

8.4 ± 0.4 (n=3) (101 ± 2% inhibition) |

| 35 |

|

>10,000 |

| 36 |

|

>10,000 |

| 37 | -NHMe | 985 ± 71 (n=3) (106 ± 0% inhibition) |

IC50 values are the means ± S.E.M. of two independent experiments performed in duplicate unless otherwise indicated, as described in the Methods. Percent inhibition is calculated with the equation % Inhibition = [1 – (compound signal / PEA EC60 signal)] × 100.

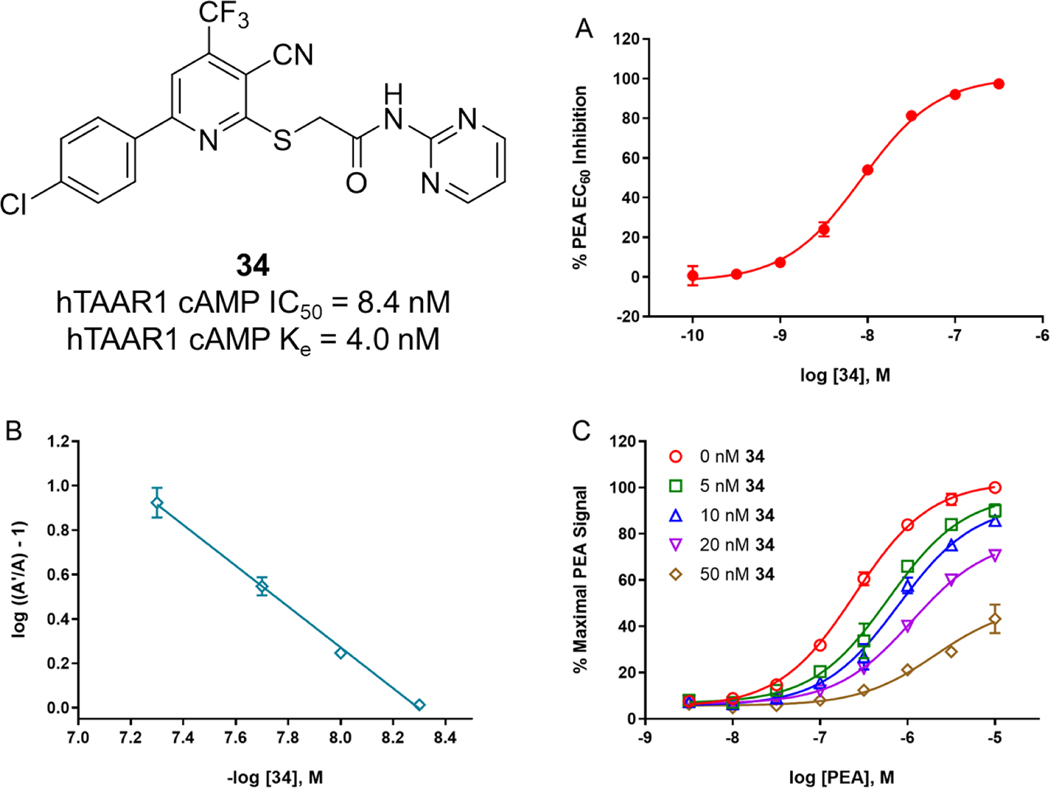

Our initial SAR by catalog demonstrated that area D is critical to activity, and that small changes to area D cause dramatic decreases in antagonist activity. Area D does not tolerate phenyl rings and seems to prefer sterically smaller groups. The antagonist activity of large groups can be improved by the addition of a heteroatom (nitrogen, oxygen). The 2-pyrimidine 34 drove a large increase in potency (~1.5 orders) compared to the pyridine 33. A 5-membered saturated nitrogen-containing ring (pyrrolidine 26) is also tolerated but the pyrimidine is still superior. It is unclear if the 4-chlorophenyl moiety is required to maintain activity. Analogs with a 2-thienyl, other phenyl substitutions (fluoro, methoxy, methyl, pyridine), or methyl resulted in loss of activity, but none of those compounds possessed a pyrimidine ring. The most important finding of this study is the identification of a potent hTAAR1 antagonist, 2-[[6-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-cyano-4-(trifluoromethyl)-2-pyridinyl]thio]-N-2-pyrimidinylacetamide 34 (Figure 3A). With an IC50 value of 8.4 nM, 34 is 893-fold and 1071-fold, respectively, more potent compared to the known compounds EPPTB (IC50 = 7.5 μM) and Cmpd 3 (IC50 = 9 μM).

Figure 3.

Activity profile of 34. (A) Antagonist activity of 34 in hTAAR1 cAMP IC50 assay. (B-C) Schild analysis to determine mode of antagonism. Each data point is the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments conducted in duplicate.

To further evaluate the mode of antagonism for 34, a Schild analysis29 was performed. Multiple, single concentrations of 34 were tested in the presence of a PEA concentration response curve to measure 34’s ability to induce a rightward shift of the PEA response. The Schild analysis showed that 34 has a linear plot with a slope of −0.92, indicating that 34 is likely a competitive antagonist (Figure 3B–C). An apparent Ke value was also calculated using the equation described previously: Ke = [L] / ((A’/A) – 1), where [L] is the test compound concentration, A’ is the EC50 value of PEA with 34, and A is the EC50 value of PEA alone.22,27,30–35 In our assay, 34 has an apparent Ke value of 4.0 ± 0.6 nM, which is consistent with the estimated pA2 value determined from the Schild plot (5 nM, x-intercept).

Species Selectivity.

Compared to other GPCRs, the human, rat, and mouse TAAR1 orthologues have relatively low sequence homology (87% mouse/rat, 76% human/mouse, and 79% human/rat).2 Given this information, the differences in potency at the TAAR1 orthologues observed for EPPTB are not surprising, but they do show the challenges associated with the development of TAAR1 ligands from a therapeutic perspective. For example, potent hTAAR1 compounds tend to be much less potent at rodent TAAR1, and therefore cannot be easily studied in rodent disease models. On the other hand, potent rodent TAAR1 compounds tend to be much less potent at hTAAR1, and therefore cannot be developed into human therapeutics. TAAR1-mediated species differences with antagonists, or inverse agonists can be very large (several orders of magnitude); however, the species differences associated with TAAR1 agonists tend to be smaller and not as extreme, which likely benefited their development as therapeutic candidates (i.e. Hoffman-LaRoche TAAR1 agonists).10–12

To determine species differences for our most potent hTAAR1 compounds (IC50 < 500 nM; 1, 26, 33, 34), rTAAR1 and mTAAR1 antagonist activity was evaluated using stable rTAAR1-HEK293 and mTAAR1-HEK293 cells with the LanceUltra (PerkinElmer) platform. In our assays, PEA has an EC50 (± S.E.M.) of 231 ± 15 nM and 150 ± 9 nM at rTAAR1 and mTAAR1, respectively, which compares well with the literature values of 110 nM and 200 nM, respectively (Figure S1B–C).28 It is important to note that PEA has a similar potency in our hTAAR1 assay (EC50 = 193 nM). This is significant because using a control that has similar EC50 values across all three assays allows for a better comparison of compound activity; this effect has also been observed by others.28 34, the most active compound at hTAAR1 (IC50 = 8.4 nM), was 89-fold and 142-fold less potent at rTAAR1 (IC50 = 748 nM) and mTAAR1 (IC50 = 1190 nM), respectively, with a rank order potency of hTAAR1 > rTAAR1 > mTAAR1 (Table 3). Interestingly, this activity profile is opposite to that of EPPTB, which is potent at mTAAR1 (IC50 = 27.5 nM) but is 272-fold and 165-fold less potent at hTAAR1 (IC50 = 7.5 μM) and rTAAR1 (IC50 = 4.5 μM), respectively, with a rank order potency of mTAAR1 > rTAAR1 > hTAAR1.14 Similar to hTAAR1, 34 reduced rTAAR1- and mTAAR1-mediated cAMP production at 10 μM (−15.4% and −12.0%, respectively), but did not show any reduction at lower concentrations. Again, the mTAAR1 activity parallels EPPTB’s activity (−12.3% at mTAAR1). The only other compound that had activity at mTAAR1 and rTAAR1 was pyridine 33 (hTAAR1 IC50 = 421 nM), which was 5-fold and 7-fold less potent at rTAAR1 (IC50 = 2250 nM) and mTAAR1 (IC50 = 3070 nM), respectively, with the same rank order potency of hTAAR1 > rTAAR1 > mTAAR1 compared to 34. However, the fold differences in activity were much less compared to 34, indicating the significance of the pyrimidine group for potency, and there was no reduction in cAMP production noted in either cell line. 1 and 26 did not have antagonist activity at mTAAR1 and rTAAR1 despite being potent hTAAR1 antagonists, indicating that oxazole and pyrrolidine groups in region D are not well tolerated for rodent TAAR1 activity. Taken together, these data show that 34 has species differences in activity, but that the compound nevertheless has nanomolar potency at rTAAR1.

Table 3.

Comparison of IC50 values at human, mouse, and rat TAAR1 for 33, 34, and EPPTB.

Radioligand Binding.

Compound 34 was assessed in radioligand binding experiments to determine the affinity of binding to TAAR1 (Figure S4). The known radioligand [3H]RO516601736 was synthesized in our laboratory and utilized in radioligand binding assays with membranes from our hTAAR1, rTAAR1, and mTAAR1 cell lines. Methods previously developed and validated specifically for TAARs by Revel and colleagues36 were used in our laboratory. In our hTAAR1, rTAAR1, and mTAAR1 membranes, [3H]RO5166017 had Kd values of 17 nM, 8.4 nM, and 1.5 nM, respectively, as determined from saturation binding curves. We found that compound 34 competitively binds to hTAAR1 and mTAAR1 with Ki values of 0.3 nM and 139 nM, respectively (Table 4). In the functional and binding assays, 34 is 142-fold and 463-fold, respectively, more potent at hTAAR1 compared to mTAAR1. For comparison, EPPTB has Ki values of > 5 μM and 0.9 nM at hTAAR1 and mTAAR1, respectively.15 Thus, in the functional and binding assays, EPPTB is 272-fold and >5500-fold, respectively, more potent at mTAAR1 compared to hTAAR1. In the course of these binding studies, we unexpectedly found that 34 potentiates [3H]RO5166017 binding at rTAAR1 indicating that the compound may act as a potential noncompetitive antagonist at rTAAR1. Due to this surprising result, we ran a Schild analysis (Figure S5) on 34 in the rTAAR1 cAMP assay and found that the Schild plot slope was −0.3, corresponding to potential noncompetitive activity and aligning with the radioligand binding results. This interesting species difference owes further investigations, including modeling studies, to determine where 34 binds to rTAAR1, how that binding differs from hTAAR1 and mTAAR1, and how that translates to signal transduction and physiological effects.

Table 4.

Comparison of Ki and IC50 values at human, rat, and mouse TAAR1 for 34 and EPPTB.

| 34, Kia | 34, IC50b | EPPTB, Kic | EPPTB, IC50d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| hTAAR1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | > 5,000 | 7487 ± 2109 |

| rTAAR1 | N.D. | 748 ± 56 | 942 | 4539 ± 2051 |

| mTAAR1 | 139 ± 66 | 1190 ± 80 | 0.9 | 27.5 ± 9.4 |

N.D. = Not Determined.

Values (in nM) are the means ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate, as described in the Methods.

Values (in nM) are the means ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate, as described in the Methods.

Values (in nM) are from reference 15.

Values (in nM) are from reference 14.

ADME.

Physiochemical property calculations and preliminary ADME studies were performed with our lead compound 34 to assess solubility, CNS permeability, and stability (Table 5). LogP and topological polar surface area (TPSA) values can be useful predictors of a compound’s solubility and CNS permeability, respectively. 34 has a logP value of 4.71 and a TPSA value of 116.86 Å2, which are outside of the desired logP (1–4)37–38 and TPSA ranges (< 76 Å2).39 Compound 34 displayed a poor kinetic solubility (1.7 μM), which seems to correlate with the higher logP value. We also determined the CNS permeability of 34 using MDCK-mdr1 cells, which are widely used as a predictive model of estimating blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate activity.40–43 The apparent permeability (Papp) of 34 through MDCK-mdr1 monolayers was determined bidirectionally. Generally, a compound is considered CNS permeable if the Papp value is greater than 3.4 × 10−6 cm/s and the efflux ratio is less than 2.44–45 In the assay, 34 exhibited good permeability (Papp = 13.8 × 10−6 cm/s) and a favorable efflux ratio of 1, indicating it is CNS permeable and is not a P-gp substrate.

Table 5.

Physiochemical and preliminary ADME properties of 34.

| Desired Value | 34 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| MW | < 500 | 449.84 |

|

| ||

| logPa | 1 – 4 | 4.71 |

|

| ||

| TPSAa | < 76 Å2 | 116.86 |

|

| ||

| Solubility (μM) | > 60 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

|

| ||

| MDCK-mdr1: | ||

| Papp [A-to-B] (× 10−6 cm/sec) | > 3.4 | 13.8 |

| Papp [B-to-A] (× 10−6 cm/sec) | 13.9 | |

| Efflux Ratio | < 2 | 1 |

Values were calculated using Chemaxon JChem (version 19.6) embedded in our ChemCart database.

The metabolic stability of 34 was evaluated in human, rat, and mouse liver microsomes (Table 6). At 10 μM, 34 had decent stability in human liver microsomes (T1/2 = 83.9 min, CLINT = 14.9 μL/min/mg clearance), approaching the optimal values of T1/2 >120 min and CLINT <10 μL/min/mg. 34 was less stable in mouse liver microsomes (CLINT = 63.5 mL/min/mg) and had very poor stability in rat liver microsomes, as indicated by the high clearance value (CLINT = 274 mL/min/mg).

Table 6.

Stability of 34 in Human, Rat, and Mouse Liver Microsomes

| Species | Half-life (min) | Clearance, CLINT (mL/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Human | 83.9 | 14.9 |

| Rat | 9.11 | 274 |

| Mouse | 65.8 | 63.5 |

Off-target profiling.

The preliminary off-target profile of 34 was assessed in radioligand binding assays against a panel of 42 targets through the NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program.46 This panel includes human GPCRs from multiple families (serotonin, adrenergic, dopamine, opioid, histamine, muscarinic, and sigma receptors), human biogenic amine transporters (DAT, SERT, NET), and the benzylpiperazine (BZP) rat brain site. At 10 μM, 34 showed little to no off-target activity with the exception of BZP rat brain site and human sigma 2 with inhibition of 75% and 90%, respectively. The follow-up concentration response assays determined that 34 had a moderate affinity for BZP rat brain site (Ki = 1 μM) and a very weak affinity for human sigma 2 (Ki = 8.4 μM). Taken together, these results indicate that 34 is selective against a variety of targets, although more work is needed to determine its off-target profile against a wider selection of targets.

Effect of 34 on DA-ergic Neuronal Firing.

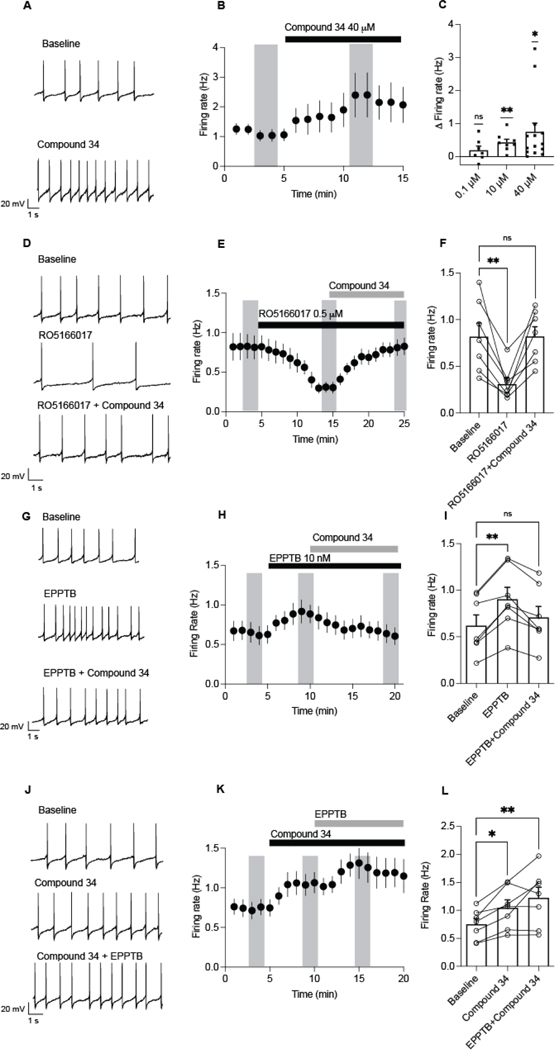

Previous work has identified that VTA dopamine neurons increase firing in response to EPPTB.14,47 To determine if 34 elicits a similar effect, electrophysiology experiments were carried out using VTA slices from mice (Figure 4). Compound 34 (40 μM) significantly increased the firing rate of VTA dopamine neurons (baseline: 1.0 ± 0.2 Hz vs. compound 34: 2.3 ± 0.6 Hz; Figure 4A–C). We next observed a concentration dependence, with compound 34 at 0.1 μM having no change in firing (change from baseline: 0.19 ± 0.1 Hz), and 10 μM (0.4 ± 0.1 Hz) and 40 μM (0.7 ± 0.2 Hz) increasing firing from baseline (Figure 4C). To determine if these effects were mediated by mTAAR1, we tested if compound 34 could reverse the effects of a selective TAAR1 agonist, RO5166017 (500 nM). Consistent with previous reports,36 RO5166017 significantly decreased firing of dopamine neurons (Figure 4D–F). Furthermore, compound 34 reversed the inhibitory effect of RO5166017, when co-applied together, suggesting that compound 34 can block the inhibitory actions of R051660017 at mTAAR1 receptors on dopamine neurons. These results correspond with the radioligand binding and functional cAMP results where we showed that 34 competitively binds to and functionally antagonizes mTAAR1.

Figure 4.

EPPTB or compound 34 increases firing of VTA dopamine neurons in mice. (A) Sample recordings of spontaneous firing before and after a 5 min application of compound 34 (40 μM) in dopamine neurons. (B) Time course of application of 40 μM compound 34 (N/n=7/3). (C) Compound 34 increased firing of dopamine neurons from baseline at 10–40 μM (one sampled t-tests 0.1 μM: t(6) = 1.7, P = 0.2, N/n=7/3; 10 μM: t(7) = 4.5, P = 0.003**, N/n=8/4; 40 μM: t(13) = 2.8, P = 0.01*, N/n=14/6). (D) Sample recordings of spontaneous firing before and after a 10 min application of RO5166017 (0.5 μM) and then RO5166017 with compound 34 (40 μM). (E) Time course of application of RO5166017 (0.5 μM) and then RO5166017 with compound 34 (40 μM). (F) RO5166017 (0.5 μM) suppressed firing rate of dopamine neurons and application of compound 34 reversed the inhibitory effects of RO5166017 (RM one way ANOVA, F(1.8, 10.9) = 12.65, P =0.0017; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: Baseline vs RO5166017, P = 0.0096**, baseline vs compound 34 + RO5166017, P = 0.99, N/n=7/3). (G) Sample recordings of spontaneous firing before and after a 5 min application of 10 nM EPPTB and EPPTB with compound 34 (40 μM) in dopamine neurons. (H) Time course of application of 10 nM EPPTB and then EPPTB with compound 34 (40 μM). (I) EPPTB increased firing of dopamine neurons from baseline, but co-application of EPPTB and compound 34 decreased firing (RM One way ANOVA, F(1.3, 7.7) = 16.20, P = 0.003; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: Baseline vs EPPTB, P = 0.0012**, baseline vs. EPPTB + compound 34, N/n=7/3, P = 0.38). (J) Sample recordings of spontaneous firing before and after a 5 min application of compound 34 (40 μM) and then compound 34 with 10 nM EPPTB in dopamine neurons. (K) Time course of application of compound 34 (40 μM) and then compound 34 with 10 nM EPPTB. (L) Co-application of compound 34 and EPPTB increased firing from baseline (RM one way ANOVA, F(1.4, 8.6) = 10.3, P = 0.0077; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: Baseline vs compound 34, P = 0.0069**, baseline vs compound 34 + EPPTB, P = 0.016*). Vertical shaded bars represent averaged periods analyzed for the bar graph. Bars are mean ± S.E.M and symbols represent responses from individual neurons.

We next tested if compound 34 altered firing in neurons responsive to EPPTB (10 nM). EPPTB significantly increased firing of dopamine neurons from baseline (baseline: 0.6 ± 0.1 Hz vs. EPPTB: 0.9 ± 0.1 Hz; Figure 4G–I). Surprisingly, when compound 34 was applied after EPPTB, the firing rate decreased to 0.7 ± 0.1 Hz, which was not significantly different from baseline (Figure 4G–I). Conversely, when compound 34 was applied prior to EPPTB, there was no inhibition of compound 34 potentiated firing (Figure 4J–L). Taken together, these results indicate that, like EPPTB, 34 increases the firing rate of VTA dopamine neurons via TAAR1 receptors. However, it is possible that these drugs may target TAAR1 receptors coupled to different intracellular mechanisms.

Activation of TAAR1 receptors inhibits dopaminergic firing through TAAR1-mediated activation of Kir3,14 as well as internalization of dopamine transporters48 leading to increased ambient dopamine acting at D2 receptors to potentially suppress firing. Thus, TAAR1 antagonists or TAAR1−/− knockout mice have increased dopamine neuronal firing when this tonic inhibition is removed.14,36 In addition to its effects on firing, EPPTB can increase agonist potency at D2 receptors and reduce D2 desensitization making D2 receptors more sensitive to ambient DA.14 Given that somatodendritic D2 receptor activation suppresses dopamine neuronal firing,49 a possible effect of both antagonists at increasing D2 receptor sensitivity could potentially counteract increases in firing through disinhibition of TAAR1 activation of Kir3. Future studies should be aimed at further identifying the nature of the TAAR1 interaction with D2 receptors. A second alternative explanation is that EPPTB and compound 34 target TAAR1 receptors coupled to different intracellular pathways. For example, intracellular TAAR1 receptors coupled to Gα13 lead to activation of Rho signaling, whereas TAAR1 receptors coupled to Gαs propagate PKA signaling.6 Thus, if EPPTB and compound 34 had different affinities for these receptor complexes, activation of these intracellular processes could have differential effects on neuronal firing. The differences in activity between EPPTB and 34 in the co-application studies could also be due to species differences in how the compounds interact with endogenous mouse proteins or the mTAAR1 complex. This could also include mouse variants of mTAAR which could lead to wider changes in relative potency in tissue.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have identified a potent hTAAR1 antagonist, 34 (RTI-7470–44, hTAAR1 IC50 = 8.4 nM), through SAR studies of an antagonist hit identified from a previous HTS effort. Despite showing species differences in TAAR1 activity, RTI-7470–44 has nanomolar potency at rTAAR1 (IC50 = 748 nM) and micromolar potency at mTAAR1 (IC50 = 1190 nM). Radioligand binding experiments with the known radioligand [3H]RO5166017 revealed that RTI-7470–44 competitively binds to hTAAR1 and mTAAR1 but appears to noncompetitively bind to rTAAR1. Preliminary ADME studies revealed that RTI-7470–44 has poor solubility and moderate stability, but is CNS permeable, indicating that structural changes are required to improve certain properties. Preliminary off-target profiling showed that RTI-7470–44 is selective against a small panel of targets (42), but that more work is needed to determine its off-target liabilities against a larger panel of targets. Electrophysiology experiments in mice revealed that RTI-7470–44 increases the firing rate of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and reversed the inhibitory effects of the known TAAR1 agonist RO5166017. Further, in co-application studies with RTI-7470–44 and EPPTB, we found that RTI-7470–44 appears to block EPPTB’s ability to increase firing rate, but that EPPTB is not able to block RTI-7470–44’s ability to increase firing rate. We plan to further explore this interesting interaction in an effort to understand the mechanism of this effect and to determine if different intracellular pathways or interactions with D2 receptors play a role. We also plan to use RTI-7470–44 as a TAAR1 antagonist probe in the further characterization and exploration of TAAR1 pharmacology through signaling assays, including those that elucidate β-arrestin-mediated G protein-independent signaling and Gα13 signaling. Modeling studies are also planned to help elucidate why RTI-7470–44 is a competitive antagonist at hTAAR1 and mTAAR1 and a noncompetitive antagonist at rTAAR1. Finally, we plan to continue to examine key areas A-D to identify compounds that maintain high TAAR1 potency and CNS permeability while improving solubility. Such compounds will then be evaluated in animal models in an effort to help elucidate the complex pharmacology of TAAR1 and its therapeutic potential for hypodopaminergic diseases such as PD.

METHODS

Chemistry

All compounds evaluated in this study were purchased from ChemBridge (San Diego, CA) or ChemDIV (San Diego, CA). Additional quantities of compound RTI-7470–44 were synthesized in our laboratory to provide material for in depth biological evaluations (ADME, slice work).

General Methods.

All reagents were purchased from Oakwood Chemicals and used as supplied. 1H NMR spectra and 13C NMR spectra were collected on the Varian Unity INOVA (500 MHz) in DMSO-d6. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to the reference signal and coupling constant (J) values are reported in hertz (Hz). LC/MS was recorded using an Agilent InfinityLab MSD single quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an API-ES and an Agilent Infinity II 1260 HPLC equipped with an Agilent Infinity 1260 variable wavelength detector and a Phenomenex Synergi 2.5 mm Hydro-RP 100A C18 30×2 mm column. HPLC Method used: starting with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min for 0.4 minutes at 20% solvent B followed by a 1.6-minute gradient of 20–95% solvent B at 0.6 mL/min followed by 2 minutes at 95% solvent B with a gradual ramp up of the flow rate to 1.2 mL/min at the end (solvent A, water with 0.1% formic acid; solvent B, acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and 5% water; absorbance monitored at 220 and 280 nm). MS Method used: using atmospheric pressure ionization-electrospray, positive and negative ions were monitored in the range of 70–700. Melting points were determined on a MEL-TEMP®.

2-chloro-N-2-pyrimidinyl acetamide (34a).

To a solution of 2-aminopyrimidine (2.0 g, 21 mmol) in DCM (270 mL) at RT was added K2CO3 (5.8 g, 42 mmol) followed by chloroacetyl chloride (2.61 g, 23.1 mmol) dropwise. Following addition, the suspension was allowed to stir for 4 h and then filtered. The filtrate was washed with water, dried (MgSO4), and concentrated to a greenish solid that was triturated with hexanes and filtered to afford 34a (3.1 g, 85% yield) which was used without further purification.

6-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,2-dihydro-2-thioxo-4-(trifluoromethyl)-3-pyridinecarbonitrile (34c).

Compound 34b (2.0 g, 8.0 mmol), cyanothioacetamide (1.2 g, 12.0 mmol), and DABCO (896 mg, 8.0 mmol) were combined and refluxed in EtOH (20 mL) for 3 h. The suspension was cooled to RT and concentrated to a red-orange residue that was treated with 3N HCl (10 mL), water (20 mL), and enough of a sodium bicarbonate solution (5%) to bring the pH to pH=7. The resulting bright orange suspension was filtered and washed with MeOH (2 × 30 mL). The solid was dried to afford 34c (1.88 g, 75% yield) as a stable intermediate which was used in the next reaction: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ 8.15 (d, 2H, J = 8), 7.53 (d, 2H, J = 9), 7.30 (s, 1H); MS (m/z) 315.0 (m+1).

2-[[6-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-cyano-4-(trifluoromethyl)-2-pyridinyl]thio]-N-2-pyrimidinylacetamide (34, RTI-7470–44).

To a solution of 34c (500 mg, 1.59 mmol) in DMF (15 mL) was added KOH (89 mg, 1.59 mmol) in water (2 mL). The resulting solution was stirred at RT for 12 h and diluted with water (25 mL). The solid was filtered, washed with water (2 × 25 mL) and MeOH (2 × 10 mL), and dried to afford RTI-7470–44 as a light yellow solid (354 mg, 50% yield): mp 234–236 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ 11.18 (s, 1H), 8.7 (d, 2H, J = 5), 8.3 (d, 2H, J = 9), 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, 2H), J = 9), 7.23 (t, 1H, J = 5), 4.61 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ 157.3, 154.5, 149.3, 149.0, 141.1, 128.7, 126.4, 125.3, 125.0, 120.7, 120.4, 108.9, 108.7, 104.9, 102.7, 52.1; MS (m/z) 450.8 (m+1).

cAMP Methods

Materials.

PEA and IBMX were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Cell culture reagents, cell culture consumables, and assay-specific consumables were purchased from Fisher SSI. Lipofectamine LTX was purchased from Invitrogen. FuGENE HD was purchased from Promega Corporation. The LanceUltra cAMP kit (TRF0262) was purchased from PerkinElmer.

Creation of stable cell lines.

The stable hTAAR1-CHO cells were created by transfecting CHO cells with a previously described hTAAR1 mammalian expression vector.50 Cells were maintained under antibiotic selection (1 mg/mL G418) for 2 weeks, after which clones were selected from low-density cultures and screened for PEA activity using the LanceUltra cAMP kit. The clone with the most potent PEA EC50 and largest signal window was chosen as the working clone. Stable hTAAR1-CHO cells were maintained in Ham’s F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1x penicillin/streptomycin (P/S), and 200 μg/mL G418.

The stable rTAAR1-HEK293 cells were created by transfecting HEK293 cells with a linearized HA-rTAAR1-pcDNA3.1+ mammalian expression vector, which was prepared by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) by cloning rTAAR1 cDNA (NM_134328.1) into the pcDNA3.1(+)-N-HA vector at the KpnI and BamHI restriction sites. The DNA was linearized by ScaI digestion prior to transfection. Cells were maintained under antibiotic selection (800 ug/mL G418) for 2 weeks, after which clones were selected from low-density cultures and screened for PEA activity using the LanceUltra cAMP kit. The clone with the most potent PEA EC50 and largest signal window was chosen as the working clone. Stable rTAAR1-HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium-High Glucose (DMEM-HG) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x P/S, and 400 μg/mL G418.

The stable mTAAR1-HEK293 cells were created by transfecting HEK293 cells with an mTAAR1-pcDNA3.1+ mammalian expression vector. The vector was prepared by first generating the full-length mTAAR1 coding sequence by PCR of the mTAAR1-pCR4-TOPO DNA (Open Biosystems, cat # MMM1013–211691709). The primer pairs used, 5’- CAGGATCCACCATGCATCTTTGCCACGCTATC-3’ and 5’-CTCTCGAGCATGAATTGCGTTACAAAAATAGC-3’, incorporate BamHI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites. These sites were used to subclone the mTAAR1 coding sequence into the pcDNA3.1+ mammalian expression vector (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA from the resulting construct was prepared using Qiagen’s HiSpeed plasmid midi-prep kit and the sequence was verified. Cells were maintained under antibiotic selection (1.5 mg/mL G418) for 2 weeks, after which clones were selected from low-density cultures and screened for PEA activity using the LanceUltra cAMP kit. The clone with the most potent PEA EC50 and largest signal window was chosen as the working clone. Stable mTAAR1-HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM-HG supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x P/S, and 400 μg/mL G418.

Lance™ Ultra cAMP IC50 assays.

All cAMP assays were performed using procedures similar to our previously published methods for other targets.26–27,51 Stimulation buffer containing 1X Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), 5 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA stabilizer, and 0.5 mM final IBMX was prepared and titrated to pH 7.4 at room temperature. Eight-point serial dilutions of the test compounds and PEA, along with a single concentration of PEA (EC60 specific to each cell line: human 300 nM, rat 600 nM, and mouse 316 nM), were prepared at 4x the desired final concentration in 2% DMSO/stimulation buffer. A cAMP standard curve was prepared at 4x the desired final concentration in stimulation buffer. The following compound additions were made to a 96-well white ½ area microplate (PerkinElmer). To wells containing the cAMP standard curve, 10 μL each of the cAMP standard curve and 2% DMSO/stimulation buffer was added. To wells containing the PEA control, 5 μL each of the PEA serial dilutions and 2% DMSO/stimulation buffer were added. To wells containing test compounds, 5 μL each of the test compound serial dilutions and PEA EC60 were added. Control wells containing vehicle (1% final DMSO/stimulation buffer) and PEA EC60 were also included. Cells were lifted with versene, counted, and spun at 270g for 10 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in stimulation buffer and cells (10 μL) were added to each well except wells containing the cAMP standard curve (human 2500 cells/well, rat 2000 cells/well, and mouse 2000 cells/well). After incubating for 30 min at room temperature, Eu-cAMP tracer and uLIGHT-anti-cAMP working solutions were added per the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation at room temperature for 1 hour, the TR-FRET signal (ex 337 nm) was read on a CLARIOstar multimode plate reader (BMG Biotech, Cary, NC). Agonist assays were run in the same manner except that instead of the challenge PEA concentration, 2% DMSO stimulation buffer was added.

Lance™ Ultra cAMP curve-shift assay.

Curve-shift assays were carried out using the same procedure described for the IC50 assays except that test compound wells contained 5 μL each of a single concentration of test compound and 8-point PEA serial dilutions.

Data Analysis.

TR-FRET data were collected by the CLARIOstar multimode plate reader (BMG Biotech, Cary, NC). The TR-FRET signal (665 nm) was converted to fmol cAMP by interpolating from the standard cAMP curve. All nonlinear regression analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

IC50 assays:

The fmol cAMP values were plotted against the log of compound concentration and data were fit to a three-parameter logistic curve to generate IC50 values (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) using the equation Y=Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1+10^(X-LogIC50)).

Curve-shift assays:

The fmol cAMP values were plotted against the log of compound concentration and data were fit to a three-parameter logistic curve to generate EC50 values (concentration of compound that produces half-maximal response) using the equation Y=Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1+10^(LogEC50-X)). Apparent Ke values were calculated using the equation Ke = [L] / ((A’/A) – 1) where [L] is the concentration of antagonist, A’ is the EC50 value of PEA in the presence of antagonist, and A is the EC50 value of PEA in the absence of antagonist. Ke values were considered valid when the ER was at least 2.

Schild plot:

The curve shift assay data were used to determine log ((A’/A) – 1) values, which were plotted with the negative log of each corresponding antagonist concentration using a linear regression analysis.

Radioligand Binding Methods

Membranes were prepared from our hTAAR1-CHO, rTAAR1-HEK293, and mTAAR1-HEK293 stable cell lines using published methods as a reference.36 Cells were grown in culture dishes, harvested via mechanical scraping in ice-cold PBS (without Ca2+ and Mg2+), and pelleted at 800 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in cold homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, 0.7x Halt protease inhibitor) and homogenized with a Wheaton Teflon homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 48,000g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer and homogenized as before. The homogenate was centrifuged as before and the resulting pellet was resuspended in ice-cold storage buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, 0.32 M sucrose, 0.7x Halt protease inhibitor). Aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay. The dissociation constant (Kd) was determined by a saturation curve.

Competition binding assays were conducted using published methods as a reference.36 In matrix tubes, the following components were loaded: 150 μL of assay buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2), 50 μL of serial dilutions of 34 (prepared at 10x in 1% DMSO/assay buffer), 50 μL of [3H]RO5166017 Kd (prepared at 10x in assay buffer, hTAAR1 – 17 nM, rTAAR1 – 8.4 nM, mTAAR1 – 1.5 nM), and 250 μL of membranes (hTAAR1 – 10 μg/well, rTAAR1 – 10 μg/well, mTAAR1 – 30 μg/well). Non-specific binding (NSB) was determined in the presence of 10 μM RO5166017 and total binding (TB) was determined in the presence of 1% DMSO/assay buffer. The tubes were incubated at 4°C for 60 min (human) or 90 min (mouse, rat). The assay was terminated by rapid filtration through Unifilter-96 GF/C plates (PerkinElmer) presoaked for 1 h in PEI (0.3%) and washed three times with 1 mL of cold wash buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2). The plates were dried and 50 μL of Microscint 20 was added. Plates were counted using a Wallac MicroBeta TriLux (PerkinElmer).

Data Analysis.

Fmol radioactivity/mg protein was calculated from the counts. Specific binding was plotted against the log of compound concentration and nonlinear regression analysis was used to generate Ki values using the equations logEC50 = log(10^logKi*(1+RadioligandNM/HotKdNM)) and Y=Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1+10^(X-LogEC50)) in GraphPad Prism.

ADME Methods

Kinetic Solubility.

Test compound kinetic solubility was measured in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, consisting of 45 mM potassium phosphate monobasic, 45 mM potassium acetate, and 45 mM ethanolamine. An 8 μL sample of test compound stock solution (10 mM DMSO) was combined with 792 μL of phosphate buffer and shaken for 90 min at room temperature. The final concentration of DMSO was 1%. After the incubation, samples were filtered through a 0.4 μm filter plate (Millipore). On each experimental occasion, tamoxifen and caffeine were assessed as reference compounds for low and high solubility, respectively. Filtrates were assessed in triplicate and analyzed by LC-MS/MS using electrospray ionization against standards prepared in the same matrix.

CNS Permeability.

Assays were conducted by Paraza Pharma, Inc. MDCK-MDR1 cells at passage 14 were seeded onto permeable polycarbonate supports in 12-well Costar Transwell plates and allowed to grow and differentiate for 3 days. On day 3, culture medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS) was removed from both sides of the Transwell inserts and cells were rinsed with warm HBSS. After the rinse step, the chambers were filled with warm transport buffer (HBSS containing 10 mM HEPES, 0.25% BSA, pH 7.4) and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min prior to TEER (Trans Epithelial Electric Resistance) measurements.

The buffer in the donor chamber (apical side for A-to-B assay, basolateral side for B-to-A assay) was removed and replaced with the working solution (10 μM test article in transport buffer). The plates were then placed at 37°C under light agitation. At designated time points (30, 60 and 90 min), an aliquot of transport buffer from the receiver chamber was removed and replenished with fresh transport buffer. Samples were quenched with ice-cold acetonitrile (ACN) containing internal standard and then centrifuged to pellet protein. Resulting supernatants were further diluted with 50/50 ACN/H2O (H2O only for atenolol) and analyzed with LC-MS/MS techniques. Reported apparent permeability (Papp) values were calculated from a single determination. Atenolol and propranolol were tested as low and moderate permeability references, respectively. Bidirectional transport of digoxin was assessed to demonstrate P-gp activity/expression. The apparent permeability (Papp, measured in cm/s) was determined according to the following formula: Papp = [(dQ) / (dt)] / [A * Ci * 60] where dQ/dt is the net rate of appearance in the receiver compartment, A is the area of the Transwell measured in cm2 (1.12 cm2), Ci is the initial concentration of compound added to the donor chamber, and 60 is the conversion factor for minutes to seconds.

Microsomal Stability Studies.

Microsomal stability assays were performed as described previously.52 Briefly, test compounds were incubated at 10 μM final concentration with 0.5 mg/mL pooled human liver microsomes from 200 unidentified donors (Xenotech, LLC, Lenexa, KS) in a 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), 5 mM uridine diphosphate glucuronic acid (UDPGA), and 50 μg/mL alamethicin. Triplicate samples were incubated for up to 120 min. Samples were removed at regular intervals. Reactions were terminated by addition of 3 volumes of methanol and 50 μL of the quenched sample was diluted with 50 μL of 10mM ammonium formate with 0.1% formic acid prior to analysis by LC/MS/MS at 10 μL injection. Standard curves were prepared in blank matrix for each compound for quantitative assessment. The intrinsic clearance rate was calculated for each compound using the following formula: CLINT (mL/min/kg) = (0.693/T1/2) × microsomal protein concentration × (mg/g liver) × (g of liver/kg body weight). Data reported are average values from three measurements.

Electrophysiology Methods

All protocols were in accordance with the ethical guidelines established by the Canadian Council for Animal Care and were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care Committees. All mice were bred and housed in groups of 2–5 and were maintained on a 12-h light/dark schedule and were given food and water ad libitum. Experiments were performed during the animal’s light cycle.

All electrophysiological recordings were performed in slice preparations from adult male and female DAT-IRES-Cre;td-Tomato mice (2–3 months old). Male and female DATcreTd-Tomato mice were generated by crossing DAT-Cre (B6.SJL-Slc6a3tm1.1(cre)Bkmn/J mouse line) with Rosa-td Tomato mice (B6.Cg Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (Ai9)). All mice were bred locally in the Clara Christie Centre for Mouse Genomics. All mice were housed in groups of 3–4 on a 12h reverse light/dark cycle room (lights on at 8 AM MST, zeitgeber time (ZT0)) with regulated humidity and temperature (21±2ºC) and were given chow and water ad libitum. Mice were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane and intracardially perfused with N-methyl D-glucamine (NMDG) solution (in mM): 93 NMDG, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4.H2O, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 D-glucose, 5 sodium ascorbate, 3 sodium pyruvate, 2 thiourea, 10 MgSO4.7H2O, 0.5 CaCl2.2H2O and saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2. Mice were then decapitated and horizontal midbrain sections (250 μm) containing the VTA were cut in NMDG solution using a vibratome (VT1200, Leica Microsystems, Nussloch, Germany). Slices were recovered in warm NMDG solution (32 °C) saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2 for 10 min before being transferred to a holding chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (in mM): 126 NaCl, 1.6 KCl, 1.1 NaH2PO4, 1.4 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 11 glucose (32°C); equilibrated with 95% O2 / 5% CO2 for at least 45 min before recording. Slices were transferred to a recording chamber on an upright microscope (Olympus BX51WI) and continuously superfused with ACSF (2 mL.min−1, 34 °C). VTA dopamine neurons were identified by red fluorescence, morphological and electrophysiological characteristics (fusiform shape, capacitance > 50 pF, presence of H-current (Ih)). VTA dopamine neurons were visualized with a 40X water immersion objective using Dodt gradient contrast optics. Whole-cell current clamp recordings were made using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices). Recording electrodes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with potassium-D-gluconate internal solution (in mM): 136 potassium-D-gluconate, 4 MgCl2, 1.1 HEPES, 5, EGTA, 10 sodium creatine phosphate, 3.4 Mg-ATP and 0.1 Na2GTP. Spontaneous firing activity was recorded in current clamp mode. Firing data for all neurons was analyzed with the MiniAnalysis program (Synaptosoft) using the same criteria.

EPPTB (10 nM) and compound 34 (40 μM) were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to their final concentration in ACSF and bath applied to slices (DMSO concentration 0.01%) for 5 min. A 2 min period prior to application of drug was averaged as the baseline and compared to a 2 min period after application or co-application of drugs was averaged as the drug effect, as indicated by shaded vertical bars on graphs. Responses from neurons of male and female mice were analyzed together as these studies were not sufficiently powered to test for sex differences.

Data analysis.

All data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Data were analyzed with a paired t-test or a repeated measures (RM) one way ANOVA for paired multiple group comparisons. In all electrophysiology experiments, sample size is expressed as N/n where “N” refers to the number of cells recorded from “n” animals. Statistical analysis was reported from cell variability. Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used to perform statistical analysis. Figures were generated using Prism 9 and Illustrator CS software (Adobe Systems Incorporated). The levels of significance are indicated as follows: **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rodney Snyder, Yun Lan Yueh, Kelly Mathews, Vineetha Vasukuttan, and Dr. Angela Giddings for their valuable technical assistance.

Funding Sources

The chemistry, in vitro pharmacology, and ADME research was supported by the National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03NS116577 (awarded to A.M.D.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support for chemistry and ADME research was provided by RTI International research and development funds. The electrophysiology research was supported by a Canada Research Chair Tier 1 grant (950-232211) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (FDN-147473) award to S.L.B. Ki determinations and receptor binding profiles were generously provided by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Contract # HHSN-271-2018-00023-C (NIMH PDSP). The NIMH PDSP is directed by Bryan L. Roth MD, PhD (Director) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Jamie Driscoll (Project Officer) at NIMH, Bethesda MD, USA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 5-HT

serotonin

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- DA

dopamine

- EPPTB

N-(3-ethoxyphenyl)-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide

- DABCO

1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney 293

- HTS

high-throughput screen

- NE

norepinephrine

- PD

Parkinson’s Disease

- PEA

β-phenethylamine

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- TAAR1

Trace Amine-Associated Receptor subtype 1

- TPSA

topological polar surface area

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

• Additional biological data including: PEA response in hTAAR1, rTAAR1, and mTAAR1 assays; 2 and 34 responses in the hTAAR1 assay; PEA and 34 responses in parental cells; radioligand binding results with 34; and the rTAAR1 Schild analysis for 34.

• Radiochemistry methods used in the preparation of known radioligand [3H]RO5166017.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berry MD; Gainetdinov RR; Hoener MC; Shahid M, Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Pharmacol Ther 2017, 180, 161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowsky B; Adham N; Jones KA; Raddatz R; Artymyshyn R; Ogozalek KL; Durkin MM; Lakhlani PP; Bonini JA; Pathirana S; Boyle N; Pu X; Kouranova E; Lichtblau H; Ochoa FY; Branchek TA; Gerald C, Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98 (16), 8966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindemann L; Ebeling M; Kratochwil NA; Bunzow JR; Grandy DK; Hoener MC, Trace amine-associated receptors form structurally and functionally distinct subfamilies of novel G protein-coupled receptors. Genomics 2005, 85 (3), 372–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunzow JR; Sonders MS; Arttamangkul S; Harrison LM; Zhang G; Quigley DI; Darland T; Suchland KL; Pasumamula S; Kennedy JL; Olson SB; Magenis RE; Amara SG; Grandy DK, Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor. Molecular pharmacology 2001, 60 (6), 1181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harmeier A; Obermueller S; Meyer CA; Revel FG; Buchy D; Chaboz S; Dernick G; Wettstein JG; Iglesias A; Rolink A; Bettler B; Hoener MC, Trace amine-associated receptor 1 activation silences GSK3beta signaling of TAAR1 and D2R heteromers. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015, 25 (11), 2049–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Underhill SM; Hullihen PD; Chen J; Fenollar-Ferrer C; Rizzo MA; Ingram SL; Amara SG, Amphetamines signal through intracellular TAAR1 receptors coupled to Galpha13 and GalphaS in discrete subcellular domains. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26 (4), 1208–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Cara B; Maggio R; Aloisi G; Rivet JM; Lundius EG; Yoshitake T; Svenningsson P; Brocco M; Gobert A; De Groote L; Cistarelli L; Veiga S; De Montrion C; Rodriguez M; Galizzi JP; Lockhart BP; Coge F; Boutin JA; Vayer P; Verdouw PM; Groenink L; Millan MJ, Genetic deletion of trace amine 1 receptors reveals their role in auto-inhibiting the actions of ecstasy (MDMA). J Neurosci 2011, 31 (47), 16928–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindemann L; Meyer CA; Jeanneau K; Bradaia A; Ozmen L; Bluethmann H; Bettler B; Wettstein JG; Borroni E; Moreau JL; Hoener MC, Trace amine-associated receptor 1 modulates dopaminergic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008, 324 (3), 948–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gainetdinov RR; Hoener MC; Berry MD, Trace Amines and Their Receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2018, 70 (3), 549–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revel FG; Moreau JL; Pouzet B; Mory R; Bradaia A; Buchy D; Metzler V; Chaboz S; Groebke Zbinden K; Galley G; Norcross RD; Tuerck D; Bruns A; Morairty SR; Kilduff TS; Wallace TL; Risterucci C; Wettstein JG; Hoener MC, A new perspective for schizophrenia: TAAR1 agonists reveal antipsychotic- and antidepressant-like activity, improve cognition and control body weight. Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18 (5), 543–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinoza S; Leo D; Sotnikova TD; Shahid M; Kaariainen TM; Gainetdinov RR, Biochemical and Functional Characterization of the Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) Agonist RO5263397. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galley G; Stalder H; Goergler A; Hoener MC; Norcross RD, Optimisation of imidazole compounds as selective TAAR1 agonists: discovery of RO5073012. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2012, 22 (16), 5244–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz MD; Canales JJ; Zucchi R; Espinoza S; Sukhanov I; Gainetdinov RR, Trace amine-associated receptor 1: a multimodal therapeutic target for neuropsychiatric diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2018, 22 (6), 513–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradaia A; Trube G; Stalder H; Norcross RD; Ozmen L; Wettstein JG; Pinard A; Buchy D; Gassmann M; Hoener MC; Bettler B, The selective antagonist EPPTB reveals TAAR1-mediated regulatory mechanisms in dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106 (47), 20081–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stalder H; Hoener MC; Norcross RD, Selective antagonists of mouse trace amine-associated receptor 1 (mTAAR1): discovery of EPPTB (RO5212773). Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011, 21 (4), 1227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandy DK; Miller GM; Li JX, “TAARgeting Addiction”--The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016, 159, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan ES; Groban ES; Jacobson MP; Scanlan TS, Toward deciphering the code to aminergic G protein-coupled receptor drug design. Chem Biol 2008, 15 (4), 343–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cichero E; Espinoza S; Franchini S; Guariento S; Brasili L; Gainetdinov RR; Fossa P, Further insights into the pharmacology of the human trace amine-associated receptors: discovery of novel ligands for TAAR1 by a virtual screening approach. Chem Biol Drug Des 2014, 84 (6), 712–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leo D; Mus L; Espinoza S; Hoener MC; Sotnikova TD; Gainetdinov RR, Taar1-mediated modulation of presynaptic dopaminergic neurotransmission: role of D2 dopamine autoreceptors. Neuropharmacology 2014, 81, 283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolinsky TD; Swanson CJ; Smith KE; Zhong H; Borowsky B; Seeman P; Branchek T; Gerald CP, The Trace Amine 1 receptor knockout mouse: an animal model with relevance to schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav 2007, 6 (7), 628–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinoza S; Ghisi V; Emanuele M; Leo D; Sukhanov I; Sotnikova TD; Chieregatti E; Gainetdinov RR, Postsynaptic D2 dopamine receptor supersensitivity in the striatum of mice lacking TAAR1. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decker AM; Mathews KM; Blough BE; Gilmour BP, Validation of a High-Throughput Calcium Mobilization Assay for the Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1. SLAS Discov 2021, 26 (1), 140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodinovskaya LA; Shestopalov AM; Gromova AV; Shestopalov AA, One-pot synthesis of diverse 4-di(tri)fluoromethyl-3-cyanopyridine-2(1H)-thiones and their utilities in the cascade synthesis of annulated heterocycles. J Comb Chem 2008, 10 (2), 313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang NY; Zuo WQ; Xu Y; Gao C; Zeng XX; Zhang LD; You XY; Peng CT; Shen Y; Yang SY; Wei YQ; Yu LT, Discovery and structure-activity relationships study of novel thieno[2,3-b]pyridine analogues as hepatitis C virus inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2014, 24 (6), 1581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milligan G; Marshall F; Rees S, G16 as a universal G protein adapter: implications for agonist screening strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1996, 17 (7), 235–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MT; Decker AM; Langston TL; Mathews KM; Laudermilk L; Maitra R; Ma W; Darcq E; Kieffer BL; Jin C, Design, Synthesis, and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of (4-Alkoxyphenyl)glycinamides and Bioisosteric 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles as GPR88 Agonists. J Med Chem 2020, 63 (23), 14989–15012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen T; Decker AM; Langston TL; Mathews KM; Siemian JN; Li JX; Harris DL; Runyon SP; Zhang Y, Discovery of Novel Proline-Based Neuropeptide FF Receptor Antagonists. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8 (10), 2290–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmler LD; Buchy D; Chaboz S; Hoener MC; Liechti ME, In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016, 357 (1), 134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arunlakshana O; Schild HO, Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 1959, 14 (1), 48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrey DA; Decker AM; Li JX; Gilmour BP; Thomas BF; Harris DL; Runyon SP; Zhang Y, The importance of the 6- and 7-positions of tetrahydroisoquinolines as selective antagonists for the orexin 1 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem 2015, 23 (17), 5709–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrey DA; Decker AM; Zhang Y, Synthesis and Evaluation of Orexin-1 Receptor Antagonists with Improved Solubility and CNS Permeability. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9 (3), 587–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrey DA; German NA; Decker AM; Thorn D; Li JX; Gilmour BP; Thomas BF; Harris DL; Runyon SP; Zhang Y, Effect of 1-substitution on tetrahydroisoquinolines as selective antagonists for the orexin-1 receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015, 6 (4), 599–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ondachi PW; Kormos CM; Runyon SP; Thomas JB; Mascarella SW; Decker AM; Navarro HA; Fennell TR; Snyder RW; Carroll FI, Potent and Selective Tetrahydroisoquinoline Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonists of Lead Compound (3 R)-7-Hydroxy- N-[(1 S)-2-methyl-1-(piperidin-1-ylmethyl)propyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carb oxamide (PDTic). J Med Chem 2018, 61 (17), 7525–7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.German NA; Decker AM; Gilmour BP; Thomas BF; Zhang Y, Truncated Orexin Peptides: Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013, 4 (12), 1224–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carroll FI; Gichinga MG; Kormos CM; Maitra R; Runyon SP; Thomas JB; Mascarella SW; Decker AM; Navarro HA, Design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluation of JDTic analogs to examine the significance of the 3- and 4-methyl substituents. Bioorg Med Chem 2015, 23 (19), 6379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revel FG; Moreau JL; Gainetdinov RR; Bradaia A; Sotnikova TD; Mory R; Durkin S; Zbinden KG; Norcross R; Meyer CA; Metzler V; Chaboz S; Ozmen L; Trube G; Pouzet B; Bettler B; Caron MG; Wettstein JG; Hoener MC, TAAR1 activation modulates monoaminergic neurotransmission, preventing hyperdopaminergic and hypoglutamatergic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108 (20), 8485–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnott JA; Planey SL, The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2012, 7 (10), 863–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oashi T; Ringer AL; Raman EP; Mackerell AD, Automated selection of compounds with physicochemical properties to maximize bioavailability and druglikeness. J Chem Inf Model 2011, 51 (1), 148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghose AK; Herbertz T; Hudkins RL; Dorsey BD; Mallamo JP , Knowledge-Based, Central Nervous System (CNS) Lead Selection and Lead Optimization for CNS Drug Discovery. ACS Chem Neurosci 2012, 3 (1), 50–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madgula VL; Avula B; Reddy VLN; Khan IA; Khan SI, Transport of decursin and decursinol angelate across Caco-2 and MDR-MDCK cell monolayers: in vitro models for intestinal and blood-brain barrier permeability. Planta Med 2007, 73 (4), 330–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garberg P; Ball M; Borg N; Cecchelli R; Fenart L; Hurst RD; Lindmark T; Mabondzo A; Nilsson JE; Raub TJ; Stanimirovic D; Terasaki T; Oberg JO; Osterberg T, In vitro models for the blood-brain barrier. Toxicol In Vitro 2005, 19 (3), 299–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachmeier CJ; Trickler WJ; Miller DW, Comparison of drug efflux transport kinetics in various blood-brain barrier models. Drug Metab Dispos 2006, 34 (6), 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q; Rager JD; Weinstein K; Kardos PS; Dobson GL; Li J; Hidalgo IJ, Evaluation of the MDR-MDCK cell line as a permeability screen for the blood-brain barrier. Int J Pharm 2005, 288 (2), 349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di L; Kerns EH; Carter GT, Drug-like property concepts in pharmaceutical design. Curr Pharm Des 2009, 15 (19), 2184–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volpe DA, Drug-permeability and transporter assays in Caco-2 and MDCK cell lines. Future Med Chem 2011, 3 (16), 2063–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Besnard J; Ruda GF; Setola V; Abecassis K; Rodriguiz RM; Huang XP; Norval S; Sassano MF; Shin AI; Webster LA; Simeons FR; Stojanovski L; Prat A; Seidah NG; Constam DB; Bickerton GR; Read KD; Wetsel WC; Gilbert IH; Roth BL; Hopkins AL, Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature 2012, 492 (7428), 215–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lam VM; Mielnik CA; Baimel C; Beerepoot P; Espinoza S; Sukhanov I; Horsfall W; Gainetdinov RR; Borgland SL; Ramsey AJ; Salahpour A, Behavioral Effects of a Potential Novel TAAR1 Antagonist. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie Z; Miller GM, Trace amine-associated receptor 1 is a modulator of the dopamine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007, 321 (1), 128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centonze D; Usiello A; Gubellini P; Pisani A; Borrelli E; Bernardi G; Calabresi P, Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of dopaminergic neurons in mice lacking D2L receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27 (5), 723–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navarro HA; Gilmour BP; Lewin AH, A rapid functional assay for the human trace amine-associated receptor 1 based on the mobilization of internal calcium. J Biomol Screen 2006, 11 (6), 688–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin C; Decker AM; Makhijani VH; Besheer J; Darcq E; Kieffer BL; Maitra R, Discovery of a Potent, Selective, and Brain-Penetrant Small Molecule that Activates the Orphan Receptor GPR88 and Reduces Alcohol Intake. J Med Chem 2018, 61 (15), 6748–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fulp A; Bortoff K; Seltzman H; Zhang Y; Mathews J; Snyder R; Fennell T; Maitra R, Design and synthesis of cannabinoid receptor 1 antagonists for peripheral selectivity. J Med Chem 2012, 55 (6), 2820–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.